Abstract

Introduction

Patients with breast cancer, especially triple-negative breast cancer, have a poor prognosis. There is still no effective treatment for this disease. Due to resistance to traditional treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, there is a need to discover novel treatment strategies to treat this disease. Ribociclib is a selective CDK4/6 inhibitor. Approximately 20% of patients with HR+ breast cancer developed primary resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors, and more than 30% experienced secondary resistance. Since most patients experience resistance during CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment, managing this disease is becoming more challenging. Many malignant tumors abnormally express microRNA (miR)-141, which participates in several cellular processes, including drug resistance, proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion.

Materials and methods

In the present study, we cultured MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells in DMEM-F12 medium. By performing MTT assay we determined the cytotoxic effects of ribociclib on breast cancer cells, as well as determining the IC50 of it. Then, we treated the cells with ribociclib at two time points: 24 h and 72 h. After that, RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA. Finally, we performed qRT‒PCR to evaluate how ribociclib affects the expression level of desired genes.

Results and conclusion

We found that ribociclib can inhibit cell growth in a dose- and time-dependent manner. We examined the mRNA expression of 4 genes. After ribociclib treatment, the mRNA expression of CDK6 and MYH10 decreased (p < 0.01, p < 0.05). The mRNA expression of CDON increased (p<0.05), but no significant changes were observed in ZEB1 mRNA expression. Furthermore, the qRT‒PCR results for miR-141 showed that the expression of miR-141 increased (p<0.01) after 72 h of treatment with ribociclib.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1]. According to the levels of mRNA gene expression, breast cancer can be classified into molecular subtypes that provide insight into new treatment strategies and patient stratifications [2]. Unlike MDA-MB-231 cells, which are more aggressive and hormone independent, MCF-7 cells are noninvasive and have functional estrogen and EGF receptors [3].

In recent years, there have been increasing reports suggesting that miRNA molecular networks may provide new therapeutic targets or biomarkers. For example, using bioinformatics tools, Maryam Eini et al. suggested that miR-802 is a prognostic biomarker for breast cancer [4]. The miR-200 family is one of the most prominent groups of miRNAs whose expression is altered in cancer. There are three mechanisms associated with the regulation of the expression of the miR-200 family: 1) suppressing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and tumor metastasis via the miR-200/ZEB1-2 axis [5], 2) reversing chemoresistance [6], and 3) inhibiting cancer stem cell self-renewal and differentiation [7]. Some studies suggest that these compounds have oncosuppressive functions, while others suggest that they have oncogenic roles [8]. In many human malignant tumors, miR-141, a crucial member of the miR-200 family, is aberrantly expressed and involved in a variety of cellular processes, such as proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT, and resistance to drugs. miR-141 can function both as a tumor suppressor and as a tumor promoter in tumorigenicity [9].

Chemoresistance and radioresistance are the primary causes of failure in treating triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Hong Luo et al. and previous researchers have linked this resistance to zinc-finger E-box binding home box 1 (ZEB1) [10]. It has been shown that ZEB1, which is a transcription factor involved in EMT, has an imperative role in facilitating cell migration and invasion during tumor metastasis [11, 12]. However, how ZEB1 is stabilized in cells is unclear since it is subject to ubiquitination and degradation. As a result of screening a human deubiquitinase library, Zhicheng Zhou et al. identified USP51 as a deubiquitinase capable of binding ZEB1, deubiquitinating it, and stabilizing it. USP51 depletion inhibited the invasion of mesenchymal-like breast cancer cells by downregulating ZEB1 protein and mesenchymal marker expression and promoting E-cadherin upregulation. On the other hand, overexpression of USP51 led to the upregulation of ZEB1 and mesenchymal markers in epithelial cells [13].

Cyclin-dependent kinases are serine/threonine protein kinases that bind proline and are known as CDKs [14]. Cell cycle arrest in cancer cells can be achieved by pharmacologically inhibiting CDK4 and CDK6. Recent studies suggest that CDK4/6 inhibitors influence apoptotic responses, differentiation, and cancer cell immunogenicity. Using cell-based and mouse models of breast cancer along with clinical specimens, Watt et al. demonstrated that CDK4/6 inhibitors regulate cancer cell chromatin through widespread enhancer activation [15]. Therefore, targeting CDK4/6 is a paradigm shift in developing anticancer therapies [16].

Cancer therapy is becoming increasingly promising with the development of effective CDK4/6 inhibitors, such as ribociclib, palbociclib, and abemaciclib, which are already approved [16]. The third-generation CDK4/6 inhibitor ribociclib (LEE011) inhibits the expression of CDK4/6 with high selectivity [17]. Despite the crucial clinical benefits of CDK4/6 inhibitors in HR+ breast cancer [18], studies have shown that approximately 20% of patients with HR+ breast cancer develop primary resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors [19], and more than 30% experience secondary resistance [20]. The development of resistance in almost all patients during treatment poses new challenges for managing this disease [21].

In this study, we performed experiments on MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines to evaluate the effects of ribociclib on cell growth and to analyze the changes in the expression of crucial genes involved in the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

The human triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line MDA-MB-231 and the nontriple-negative breast cancer (NTNBC) cell line MCF-7 were purchased from the Iranian Biological Resource Center (IBRC). It was verified that these cell lines were not contaminated with mycoplasma. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, BioIdea, Iran) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, BioIdea, Iran) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic (BioIdea, Iran) and incubated in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

Ribociclib (LEE011) was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE) USA. A 1.0 mM stock solution was produced by dissolving 5 mg of LEE011 powder (M.W.: 434.54 g/mol, HY-15777, MCE) in 11.5064 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, DNA Biotech, Iran). The stock solution was sterilized by a 0.22 μm filter and stored at -80°C. Ribociclib was dissolved in DMSO to create a 1mM stock solution. This stock was then diluted in cell culture medium to achieve the desired test concentration of 0.1 μM. The final concentration of DMSO in the cell culture medium did not exceed 0.1% v/v for any of the ribociclib treatment conditions.

MTT cell viability assay

The MTT assay was used to determine the cytotoxic effects of ribociclib on breast cancer cells, as well as determining the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ribociclib. To evaluate cell viability, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells in the logarithmic phase of growth were plated into 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of ribociclib ranging from 9.5–15.5 μM and 10–30 μM for MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively, for 24, 48, and 72 h. After adding 20 μl of MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) reagent (5 mg/ml; Atocel, Budapest) to each well, the 96-well plates were cultured for another 4 h at 37°C. To dissolve the precipitated violet formazan, 150 μl of DMSO was added to each well after the supernatant was removed. Finally, a microplate reader (DANA-3200, Iran) was used to measure the absorbance at a wavelength of 570 nm.

RNA isolation

To evaluate how ribociclib affects the expression level of desired genes, we seeded MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells in 6-well plates (SPL, Korea) at a density of 300,000 cells per well. The 6-well plates were divided into two groups: the control group (without ribociclib treatment) and the treatment group. After 1 day of incubation, the cells in each well of the treatment group were treated with the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ribociclib according to the results of MTT assay. It was 11 μM for MDA-MB-231 cells and 20 μM for MCF-7 cells. The cells were treated at two time points: 24 h and 72 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (YTzol pure RNA, YektaTazhiz Azma, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DEPC-treated water was used to dissolve RNA, and the concentration and purity of each sample were spectrophotometrically measured by using A260/A280 measurements (NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific, USA). Additionally, agarose gel electrophoresis was used to determine RNA integrity.

cDNA synthesis and qRT‒PCR analysis

For the detection of ZEB1, CDK6, MYH10, and CDON mRNA expression, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) and random hexamers (NoteScript, Notarkib Fast cDNA Synthesis Kit, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR) was performed using SYBR Green master mix (RealTiQ, Notarkib, Iran), with GAPDH serving as an endogenous control. A QIAGEN real-time PCR cycler (Rotor-Gene Q; QIAGEN, Germany) was used, and the following three-step temperature program was applied: 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds for the denaturation step, 60°C for 30 seconds for the annealing step, and 68°C for 10 seconds for the extension step. Additionally, for the detection of miR-141 expression, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using stem‒loop primers. A miRNA cDNA synthesis kit (Notarkib, Iran) was used to synthesize cDNA. Subsequently, qRT‒PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (RealTiQ, Notarkib, Iran), with U6 serving as an internal control in a Rotor-Gene Q real-time PCR cycler. The following two-step temperature program was used: 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds for the denaturation step and 60°C for 60 seconds for the combined annealing/extension step. For all the samples, the qRT-PCR was examined in duplicate.

Reference genes (GAPDH and U6) were used to normalize the results. The relative expression levels of ZEB1, CDK6, MYH10, CDON, and miR-141 were evaluated based on the 2-ΔΔCT method. To design the primers, we used primer design software such as Blast Primer, Oligo7 and Primer3. The sequences of primers used for qRT‒PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequences of Primers used for qRT‒PCR.

| Name | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Tm (°C) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC | 60 | GAAGATGGGATGGGATTTC | 58 |

| ZEB1 | CCAGCCAAATGGAAATCAGGATG | 60 | TTGGGCGGTGTAGAATCAGAG | 59 |

| CDK6 | AAGACTGGCCTAGAGATGTTGC | 62 | TCCAGGTTTTCTTTGCACCT | 56 |

| MYH10 | CAAACGTCAGGGAGCATCTT | 58 | GCGCTGGTATTCCTCTTGTT | 58 |

| CDON | TAAAGGACGGGCAGGACATT | 58 | CGTCGCAGGTAAAGTGTACTG | 61 |

| U6 | GGATGACGCAAATTCGTGAAGC | 60 | CGTGGTTAGGGTCCGAGGTA | 60 |

| MiR-141 | GCGCGTAACACTGTCTGGTA | 60 | CGTGGTTAGGGTCCGAGGTA | 60 |

Bioinformatics

In this study, the targets of miR-141 were predicted using online bioinformatics tools. The targets with the highest match score to miR-141 according to the TargetScan, miRDB, and miRWalk databases were chosen.

GeneMANIA is a fast gene network construction and function prediction tool. The results were subsequently used to predict the interactions between USP51 and gene targets of miR-141.

Statistical analysis

In this study, GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses. Student’s t tests or analysis of variance (ANOVAs) (two-way ANOVA or mixed model) followed by Tukey’s post-test were used to determine the statistical significance of the differences between the data. The responses of cells treated with ribociclib and those in the control group were compared. A difference was considered significant at *, **, ***, and **** when the P value was less than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Results

Predicted target genes of miR-141

Based on searches of online databases such as TargetScan, miRWalk, miRDB, and GeneMANIA, we selected ZEB1, CDK6, MYH10, and CDON as genes involved in the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway and targets of miR-141 (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Target prediction and gene interaction.

Target genes of miR-141 that are involved in CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway.

Ribociclib inhibits the growth of breast cancer cell lines in a time- and dose-dependent manner

To investigate whether ribociclib inhibits the growth of MDA-MB-231 (TNBC) and MCF-7 (NTNBC) cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner, we performed an MTT assay. For this purpose, we treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with different doses of ribociclib ranging from 9.5–15.5 μM and 10–30 μM for 24, 48, and 72 h. As shown in Fig 2, cell growth decreased in both cell lines with increasing drug dose and treatment duration.

Fig 2. MTT assay.

Cell viability was determined by MTT assay after exposure to increasing doses of Ribociclib for 24, 48, and 72 h in MDA-MB-231 (a) and MCF-7 (b) cell lines. ns: not significant, * p< 0.05, *** p< 0.001, **** p< 0.0001.

Moreover, we used the results of the MTT assay to calculate the cell viability and the IC50 value of ribociclib. These values were 11 μM and 20 μM for the MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively.

Ribociclib can affect the expression of genes involved in the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway

qRT‒PCR was performed to determine whether ribociclib affects the mRNA expression of ZEB1, CDK6, MYH10, and CDON. In both cell lines, CDK6 expression was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group, as shown in Fig 3. For details, see Supporting information (S1-fig 3 and fig 4 in S1 File). In addition, the expression of MYH10 and CDON significantly decreased and increased, respectively, after 72 h of treatment with ribociclib. According to our results, there was no significant change in ZEB1 mRNA expression in any of the cell lines after 72 h of treatment with ribociclib.

Fig 3. Results of qRT-PCR for target genes of miR-141.

ZEB1, CDK6, MYH10, and CDON expression in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 11μM Ribociclib (a), and in MCF-7 cells treated with 20μM Ribociclib (b) for 24 and 72 h, compared with the control group. ns: not significant, * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001.

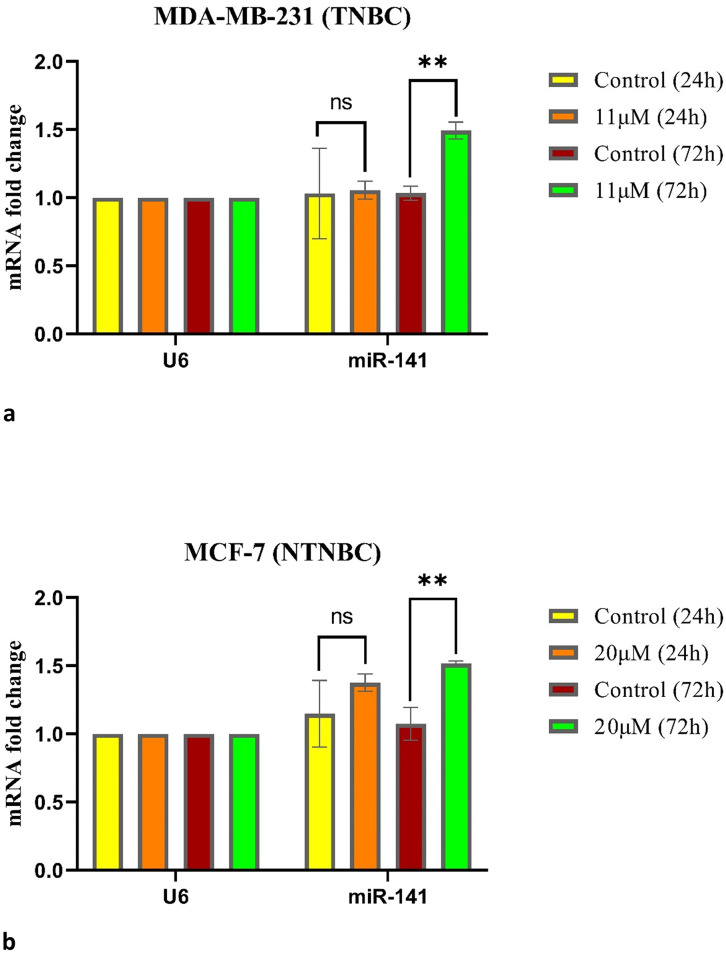

Ribociclib can affect the expression of miR-141 in breast cancer cell lines

We also evaluated the effect of ribociclib on miR-141 expression in the TNBC and NTNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7. The qRT‒PCR results demonstrated that compared with no treatment, ribociclib had no effect on these cells after 24 h but significantly increased the expression of miR-141 in cells treated with ribociclib for 72 h (Fig 4). For details, see Supporting information (S1-fig 3 and fig 4 in S1 File).

Fig 4. Results of qRT-PCR for miR-141.

miR-141 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 11μM Ribociclib (a), and in MCF-7 cells treated with 20μM Ribociclib (b) for 24 and 72 h, compared with the control group. ns: not significant, * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001.

Discussion

As TNBC is a refractory type of cancer, there is great resistance to existing treatments. Traditional therapies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combined endocrine therapy are no longer adequate for controlling cancer. Therefore, there are still many original targets to be explored in the future. The FDA has approved CDK4/6 inhibitors, and their effectiveness in various cancers has been validated both in preclinical and clinical studies. Ongoing clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of ribociclib in only a fraction of TNBC patients, while the majority of these trials have not been successful [22, 23]. With the use of drugs such as palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib, the development and design of effective CDK4/6 inhibitors are increasingly being proven to be promising cancer treatments. Ribociclib and palbociclib have similar structures and functions; however, compared with palbociclib, ribociclib binds to CDK4 and CDK6 more selectively and is less toxic to the bone marrow [24–26]. Notably, the undeniable success of ribociclib in treating breast cancer also suggests that this drug could have clinical benefits in the treatment of other cancers [27, 28]. A number of clinical trials involving this drug are underway, targeting tumor indications such as cancer of the ovary and endometrium, liposarcoma, glioblastoma, central nervous system carcinoma, melanoma, and prostate cancer [28, 29]. Therefore, we chose ribociclib for this study based on the reasons outlined above.

The MTT assay results indicated that ribociclib inhibits the growth of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. Specifically, at 15.5 μM for MDA-MB-231 cells and 30 μM for MCF-7 cells, the cells nearly died out. We treated these cells with increasing doses of ribociclib for 24, 48, or 72 h. We observed that as the drug dose and treatment duration increased, the percentage of cell viability decreased. Therefore, our results support the theory that ribociclib has an antiproliferative impact on breast cancer cells [30]. There is increasing evidence that ZEB1 plays a role in the initiation and progression of breast cancer [12, 31]. It is therefore hoped that by identifying the signaling pathways that regulate ZEB1 stabilization, anticancer therapies can be improved. A study by Zhen Zhang et al. revealed that inhibiting CDK4/6 activity reduced ZEB1 protein stability and inhibited breast cancer EMT. They found that CDK4/6 phosphorylate and activate the deubiquitinase USP51, which is necessary for ZEB1 deubiquitination and stabilization. In conclusion, the CDK4/6-USP51-ZEB1 axis is a key regulatory pathway in breast cancer metastasis that can be exploited for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the future [13].

Fig 5 shows a schematic model of the CDK4/6-USP51-ZEB1 axis. As mentioned above, due to the importance of the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway in the treatment of advanced breast cancer, we selected this signaling pathway for this study to investigate whether ribociclib affects the mRNA expression of genes involved in this pathway. As expected, qRT‒PCR analysis revealed that CDK6 mRNA expression was significantly decreased in both cell lines after 24 h, but no significant changes were observed in the mRNA expression of ZEB1. Since ZEB1 is a protein that plays a crucial role in the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway, we anticipated that its expression would decrease under treatment with ribociclib. As shown in Fig 5, ZEB1 is located downstream of CDK6; thus, we hypothesized that ribociclib may affect ZEB1 expression at the translational level. Due to the lack of western blotting analysis data, our results cannot confirm the effect of ribociclib on ZEB1 expression in breast cancer cell lines. According to a study conducted in 2020, Zhen Zhang et al. verified that ribociclib promotes the degradation of the ZEB1 protein in a ubiquitin‒proteasome-dependent manner in SUM-159 and MDA-MB-231 cells [13]. Their results strengthen our hypothesis.

Fig 5. Schematic model of the CDK4/6-USP51-ZEB1 axis.

ZEB1 protein stabilization (a). ZEB1 protein degradation (b).

In line with our results, the results of a recent study by Edris Choupani et al. showed that CDK6 expression in MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7 cells treated with enzalutamide or ribociclib was significantly lower than that in the control group [32].

Based on their target mRNAs, miRNAs can function either as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Several studies have linked the abnormal expression of miRNAs to cancer invasion, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance. In this way, miRNA expression profiles are considered biomarkers for breast cancer prognosis and prediction [33, 34]. It has been shown that hsa-miR-141 overexpression inhibits breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer invasion and migration [35–37]. There is also evidence that miR-141 regulates colorectal, lung, gastric, liver, prostate, and renal cancer cell growth and metastasis [35, 38–42]. In a study published by Ping Li et al., miR-141 was found to be downregulated in breast cancer tumor tissues compared to matched surrounding tissues. They also found that downregulation of miR-141 expression was associated with PCNA, Ki67, and HER2 expression; tumor involvement; and tumor stage. Additionally, miR-141 overexpression inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro [43].

In the present study, to investigate the effect of ribociclib on miR-141 expression, we treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with ribociclib and measured the expression of miR-141 before and after treatment with ribociclib by qRT‒PCR. Our results showed that ribociclib significantly increased the expression of miR-141 after 72 h of treatment.

In summary, we demonstrated that ribociclib potentially affects the mRNA expression of several effective genes in the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway, as well as the expression of miR-141 in the MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines. However, further studies are needed to determine how ribociclib affects other genes and other breast cancer cell lines, as well as normal breast cell lines such as MCF10-A.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study does not present a groundbreaking discovery, but it offers valuable contributions to the field of breast cancer research. Notably, we provided the first insights into ribociclib’s influence on specific genes (ZEB1, CDON, and MYH10) within the CDK4/6-USP51 signaling pathway, an area previously unexplored. It is important to emphasize that our findings suggest potential effects of ribociclib on certain gene expressions, which may be relevant to its mechanism of action. However, further studies are required to establish its efficacy as an antineoplastic drug.

Future directions and need for additional studies

While our study provides initial insights into ribociclib’s effects on gene expression in breast cancer cells, further research is essential. Key areas for investigation include:

In vivo experiments to assess efficacy and toxicity

Combination studies with other therapeutic agents

Investigations into drug resistance mechanisms

Analyses of effects on different cancer cell lines and subtypes

Exploration of additional molecular pathways affected by ribociclib

Clinical correlations using patient tumor samples

Long-term effects on cell phenotype and gene expression

These studies would enhance our understanding of ribociclib’s mechanisms of action, its potential efficacy across different breast cancer subtypes, and its optimal use in clinical settings, addressing the critical need for effective therapies for resistant breast cancers.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Medical Biotechnology Laboratory and Cellular and Molecular Research Center for their support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran” (grant number 19040). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Planning for tomorrow: Global cancer incidence and the role of prevention 2020–2070. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2021;18(10):663–72. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00514-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A. Breast Cancer—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies—An Updated Review. Cancers. 2021;13(17):4287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nohara K, Wang F, Spiegel S. Glycosphingolipid composition of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines. Breast cancer research and treatment. 1998;48(2):149–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1005986606010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eini M, Parsi S, Barati M, Bahramali G, Alizadeh Zarei M, Kiani J, et al. Bioinformatic Investigation of Micro RNA-802 Target Genes, Protein Networks, and Its Potential Prognostic Value in Breast Cancer. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2022;14(2):154–64. doi: 10.18502/ajmb.v14i2.8882 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park S-M, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME. The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes & development. 2008;22(7):894–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu S-J, Hu J-Y, Kuang X-Y, Luo J-M, Hou Y-F, Di G-H, et al. MicroRNA-200a Promotes Anoikis Resistance and Metastasis by Targeting YAP1 in Human Breast CancerMicroRNA-200a Promotes Anoikis Resistance by Targeting YAP1. Clinical cancer research. 2013;19(6):1389–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu B, Du R, Zhou L, Xu J, Chen S, Chen J, et al. miR-200c/141 regulates breast cancer stem cell heterogeneity via targeting HIPK1/β-catenin axis. Theranostics. 2018;8(21):5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye F, Tang H, Liu Q, Xie X, Wu M, Liu X, et al. miR-200b as a prognostic factor in breast cancer targets multiple members of RAB family. Journal of translational medicine. 2014;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Feng B, Han S, Zhang K, Chen J, Li C, et al. The Roles of MicroRNA-141 in Human Cancers: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(2):427–48. Epub 20160201. doi: 10.1159/000438641 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo H, Zhou Z, Huang S, Ma M, Zhao M, Tang L, et al. CHFR regulates chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer through destabilizing ZEB1. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(9):820. Epub 20210830. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04114-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krebs AM, Mitschke J, Lasierra Losada M, Schmalhofer O, Boerries M, Busch H, et al. The EMT-activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(5):518–29. Epub 20170417. doi: 10.1038/ncb3513 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caramel J, Ligier M, Puisieux A. Pleiotropic Roles for ZEB1 in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(1):30–5. Epub 20171218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2476 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Li J, Ou Y, Yang G, Deng K, Wang Q, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition blocks cancer metastasis through a USP51-ZEB1-dependent deubiquitination mechanism. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):25. Epub 20200311. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0118-x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):122. doi: 10.1186/gb4184 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watt AC, Cejas P, DeCristo MJ, Metzger-Filho O, Lam EYN, Qiu X, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition reprograms the breast cancer enhancer landscape by stimulating AP-1 transcriptional activity. Nat Cancer. 2021;2(1):34–48. Epub 20201109. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-00135-y . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adon T, Shanmugarajan D, Kumar HY. CDK4/6 inhibitors: a brief overview and prospective research directions. RSC Adv. 2021;11(47):29227–46. Epub 20210901. doi: 10.1039/d1ra03820f . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poratti M, Marzaro G. Third-generation CDK inhibitors: A review on the synthesis and binding modes of Palbociclib, Ribociclib and Abemaciclib. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;172:143–53. Epub 20190404. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.03.064 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheidemann ER, Shajahan-Haq AN. Resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(22):12292. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong T, Xue Y, Cencic R, Zhu X, Monast A, Fu Z, et al. eIF4A Inhibitors Suppress Cell-Cycle Feedback Response and Acquired Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition in Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(11):2158–70. Epub 20190808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0162 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Leary B, Cutts RJ, Liu Y, Hrebien S, Huang X, Fenwick K, et al. The Genetic Landscape and Clonal Evolution of Breast Cancer Resistance to Palbociclib plus Fulvestrant in the PALOMA-3 Trial. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(11):1390–403. Epub 20180911. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0264 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheidemann ER, Shajahan-Haq AN. Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22). Epub 20211114. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212292 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asghar US, Barr AR, Cutts R, Beaney M, Babina I, Sampath D, et al. Single-Cell Dynamics Determines Response to CDK4/6 Inhibition in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(18):5561–72. Epub 20170612. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0369 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, Kalous O, Cohen DJ, Desai AJ, et al. PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(5):R77. doi: 10.1186/bcr2419 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syed YY. Ribociclib: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2017;77(7):799–807. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0742-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, Lee NV, Hu W, Xu M, Ferre RA, Lam H, et al. Spectrum and Degree of CDK Drug Interactions Predicts Clinical Performance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(10):2273–81. Epub 20160805. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0300 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumi NJ, Kuenzi BM, Knezevic CE, Remsing Rix LL, Rix U. Chemoproteomics Reveals Novel Protein and Lipid Kinase Targets of Clinical CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Lung Cancer. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(12):2680–6. Epub 20151005. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00368 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HJ, Lee WK, Kang CW, Ku CR, Cho YH, Lee EJ. A selective cyclin-dependent kinase 4, 6 dual inhibitor, Ribociclib (LEE011) inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in aggressive thyroid cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;417:131–40. Epub 20180104. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.037 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathy D, Bardia A, Sellers WR. Ribociclib (LEE011): Mechanism of Action and Clinical Impact of This Selective Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor in Various Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(13):3251–62. Epub 20170328. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3157 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tripathy D, Bardia A, Sellers WR. Mechanism of Action and Clinical Impact of Ribociclib-Response. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(18):5658. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1819 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li T, Xiong Y, Wang Q, Chen F, Zeng Y, Yu X, et al. Ribociclib (LEE011) suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 by inhibiting CDK4/6-cyclin D-Rb-E2F pathway. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):4001–11. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1670670 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P, Sun Y, Ma L. ZEB1: at the crossroads of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastasis and therapy resistance. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(4):481–7. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1006048 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choupani E, Madjd Z, Saraygord-Afshari N, Kiani J, Hosseini A. Combination of androgen receptor inhibitor enzalutamide with the CDK4/6 inhibitor ribociclib in triple negative breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0279522. Epub 20221222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279522 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graveel CR, Calderone HM, Westerhuis JJ, Winn ME, Sempere LF. Critical analysis of the potential for microRNA biomarkers in breast cancer management. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2015;7:59–79. Epub 20150223. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S43799 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iorio MV, Casalini P, Piovan C, Braccioli L, Tagliabue E. Breast cancer and microRNAs: therapeutic impact. Breast. 2011;20 Suppl 3:S63–70. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70297-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu M, Xia M, Chen X, Lin Z, Xu Y, Ma Y, Su L. MicroRNA-141 regulates Smad interacting protein 1 (SIP1) and inhibits migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(8):2365–72. Epub 20091015. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1008-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, et al. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(6):582–9. Epub 20080516. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.74 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neves R, Scheel C, Weinhold S, Honisch E, Iwaniuk KM, Trompeter HI, et al. Role of DNA methylation in miR-200c/141 cluster silencing in invasive breast cancer cells. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:219. Epub 20100803. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-219 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du Y, Wang L, Wu H, Zhang Y, Wang K, Wu D. MicroRNA-141 inhibits migration of gastric cancer by targeting zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(3):3416–22. Epub 20150515. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3789 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzales JC, Fink LM, Goodman OB Jr., Symanowski JT, Vogelzang NJ, Ward DC. Comparison of circulating MicroRNA 141 to circulating tumor cells, lactate dehydrogenase, and prostate-specific antigen for determining treatment response in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2011;9(1):39–45. Epub 20110701. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2011.05.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Tong J, He F, Yu X, Fan L, Hu J, et al. miR-141 regulates TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition through repression of HIPK2 expression in renal tubular epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35(2):311–8. Epub 20141124. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.2008 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin L, Liang H, Wang Y, Yin X, Hu Y, Huang J, et al. microRNA-141 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion and promotes apoptosis by targeting hepatocyte nuclear factor-3β in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:879. Epub 20141125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-879 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv M, Xu Y, Tang R, Ren J, Shen S, Chen Y, et al. miR141-CXCL1-CXCR2 signaling-induced Treg recruitment regulates metastases and survival of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(12):3152–62. Epub 20141027. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0448 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li P, Xu T, Zhou X, Liao L, Pang G, Luo W, et al. Downregulation of miRNA-141 in breast cancer cells is associated with cell migration and invasion: involvement of ANP32E targeting. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):662–72. Epub 20170221. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1024 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.