Abstract

The nucleus of almost all massive galaxies contains a supermassive black hole (BH)1. The feedback from the accretion of these BHs is often considered to have crucial roles in establishing the quiescence of massive galaxies2–14, although some recent studies show that even galaxies hosting the most active BHs do not exhibit a reduction in their molecular gas reservoirs or star formation rates15–17. Therefore, the influence of BHs on galaxy star formation remains highly debated and lacks direct evidence. Here, based on a large sample of nearby galaxies with measurements of masses of both BHs and atomic hydrogen (HI), the main component of the interstellar medium18, we show that the HI gas mass to stellar masses ratio (μHI = MHI/M⋆) is more strongly correlated with BH masses (MBH) than with any other galaxy parameters, including stellar mass, stellar mass surface density and bulge masses. Moreover, once the μHI–MBH correlation is considered, μHI loses dependence on other galactic parameters, demonstrating that MBH serves as the primary driver of μHI. These findings provide important evidence for how the accumulated energy from BH accretion regulates the cool gas content in galaxies, by ejecting interstellar medium gas and/or suppressing gas cooling from the circumgalactic medium.

Subject terms: Galaxies and clusters, Interstellar medium

Supermassive black holes regulate the amount of atomic hydrogen in galaxies and the atomic hydrogen gas mass to stellar masses ratio is more strongly correlated with black hole masses.

Main

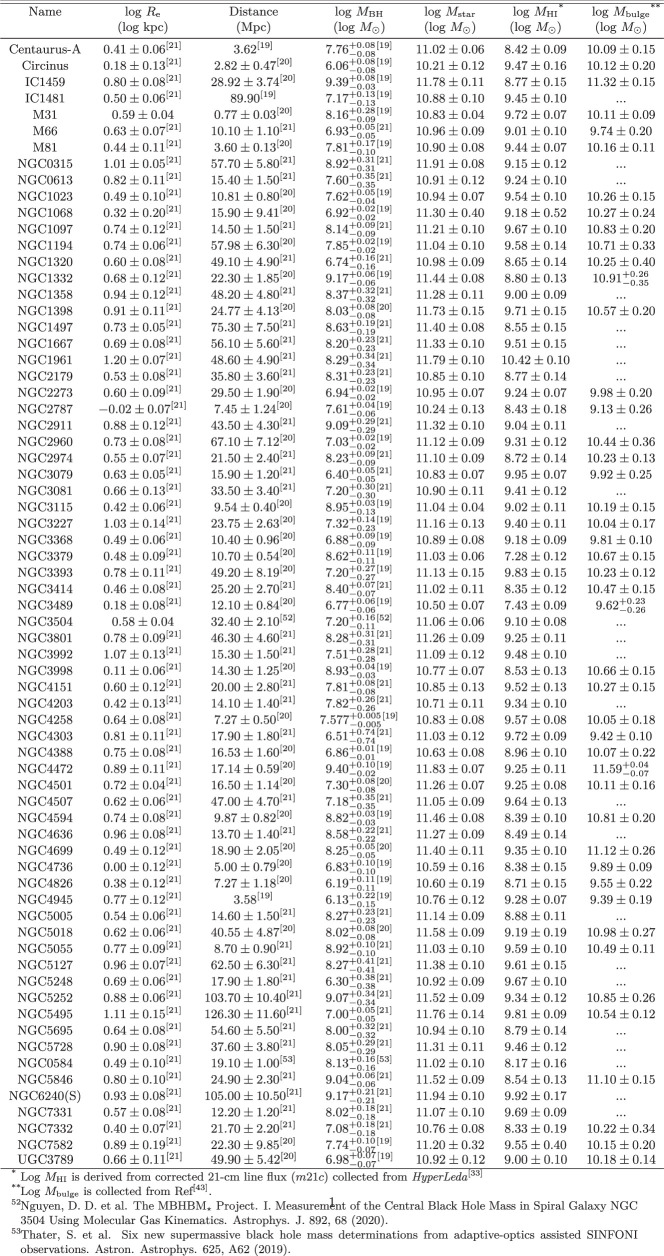

Our primary sample consists of 69 central galaxies in the nearby Universe with direct estimates of black hole (BH) masses derived from resolved kinematics of stars or gas11,19–21. We have included only central galaxies to avoid any environmental impact on the interstellar medium (ISM) properties of galaxies. The sample includes several types of galaxy, including spirals, lenticulars and ellipticals. We obtained the atomic hydrogen (HI) 21-cm emission fluxes, which trace the atomic gas mass MHI, by crossmatching with nearby galaxy databases (Methods and Extended Data Table 1).

Extended Data Table 1.

BH sample properties

We define the HI gas content as the ratio of the HI mass and the stellar mass represented as μHI = MHI/M⋆. We first examine the relationship between μHI and BH masses and compare it with the μHI–M⋆ correlation in Fig. 1. The correlation with MBH is found to be more significant than the correlation with M⋆, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of r = −0.49 (P = 10−4.7) and r = −0.39 (P = 10−3.0), respectively. More importantly, the partial correlation between μHI and M⋆ while controlling for MBH, that is, removing both their dependence on MBH, indicates that μHI shows no dependence on M⋆ (r = −0.13, P = 0.29; Fig. 1 (bottom left)), whereas strong residual correlation exists between μHI and MBH while controlling for M⋆ (r = −0.41, P = 10−3.3; Fig. 1 (bottom right)). Moreover, although the μHI–M⋆ correlation differs significantly for early- and late-type galaxies with the early-type galaxies exhibiting systematically lower μHI at fixed M⋆, galaxies with different morphologies follow the same μHI–MBH relation. This suggests that the low HI values in those early-type galaxies on the μHI–M⋆ relation are probably only a reflection that these galaxies have more massive BHs compared with late-type galaxies with similar M⋆.

Fig. 1. Comparison between the relations of μHI to M⋆ and μHI to MBH for the BH sample.

a,b, μHI–M⋆ (a) and μHI–MBH (b) correlations. Galaxies are colour-coded by their morphological T types, with smaller values being more early-type and larger values more late-type morphologies. The orange lines represent the best-fitted linear relation, taking into account the uncertainties of both variables. c,d, Comparison of the partial correlation of μHI–M⋆ (while controlling for MBH) (c) and μHI–MBH (while controlling for M⋆) (d). The x- and y-axes show the residual in μHI and M⋆ after removing their dependence on MBH in the left panel, and MBH after removing their dependence on M⋆ in the right panel: Δlog μHI = log μHI − log μHI(MBH) and Δlog M⋆ = log M⋆ − log M⋆(MBH) in the left panel, and Δlog μHI = log μHI − log μHI(M⋆) and Δlog MBH = log MBH − log MBH(M⋆) in the right panel. The horizontal dashed line indicates zero correlation, that is, there is no intrinsic correlation between the two quantities. The Spearman correlation coefficients between the two corresponding variables are shown in each panel. The error bars refer to 1σ measurement errors.

Although the partial correlation between μHI, MBH and M⋆ offers direct evidence that BHs play a more crucial part than M⋆ in regulating μHI, the heterogeneous nature of this sample makes it challenging to determine how the resulting relation could be applicable to broad galaxy populations. To validate this relation, we used a large sample of nearby galaxies with deep HI observations (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1), which comprises 474 group central galaxies with 109.5M⊙ < M⋆ < 1011.5M⊙ and reliable central velocity dispersion (σ) measurements. Out of this, 281 of them are detected in HI with HI upper limits available for the remaining 193 sources. MBH for this galaxy sample is inferred from the MBH–σ relation (Methods). Hereafter we will call this enlarged galaxy sample ‘the galaxy sample’, and we call the sample with directly measured MBH ‘the BH sample’.

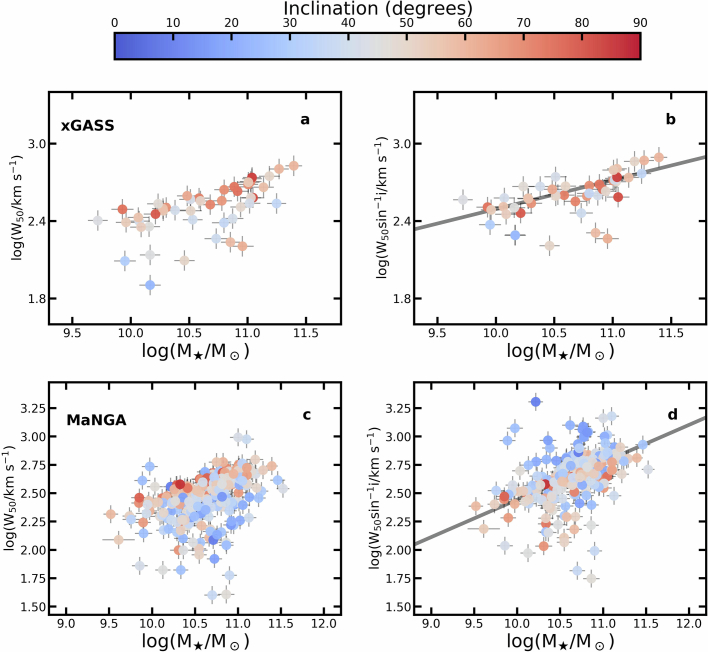

Extended Data Fig. 1. The impact of inclinations on the observed HI line width.

The relation between M⋆ and the observed HI line width are shown in panels (a, c), while the relation between M⋆ and the inclination-corrected HI line width are shown in panels(b, d), for MaNGA and xGASS galaxies respectively. The error bars refer to 1-σ errors for logM⋆. For W50, we denote 20% measurement uncertainties.

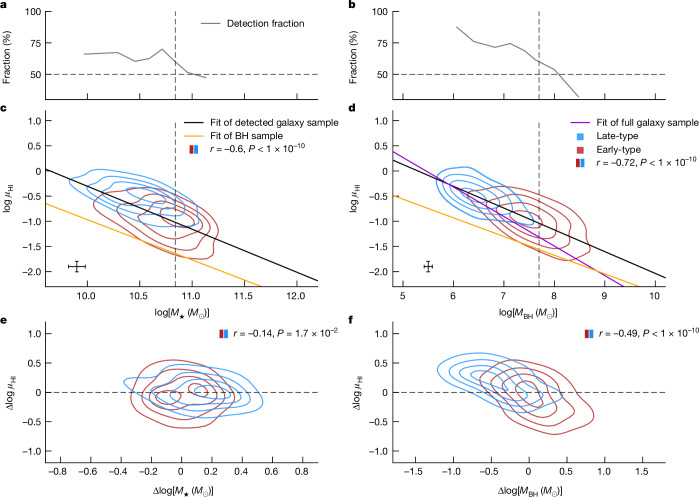

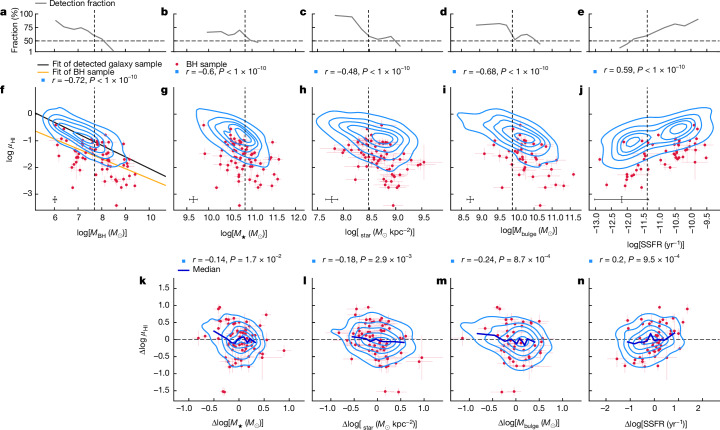

The μHI–M⋆ and μHI–MBH relations for the galaxy sample are shown in Fig. 2. Both MBH and M⋆ are found to be tightly correlated with μHI with respective r = −0.72 and r = −0.60. However, the partial correlation suggests that the μHI–M⋆ correlation almost disappears (when controlling for MBH) with r = −0.14, compared with r = −0.49 for the μHI–MBH relation (when controlling for M⋆). This further suggests that the μHI–M⋆ correlation is mostly driven by the μHI–MBH and M⋆–MBH correlations. Similar to the BH sample, early- and late-type galaxies follow the same μHI–MBH relation, but a different μHI–M⋆ relation.

Fig. 2. Comparison between the relations of μHI to M⋆ and μHI to MBH for the galaxy sample.

a,b, μHI–M⋆ (a) and μHI–MBH (b) correlations. Galaxies are divided into early- and late-type galaxies based on their Sérsic indexes (separated at n = 2), which are shown in red and blue contours, respectively. The HI-detection rates of galaxies are shown as a function of stellar masses and BH masses. The vertical dashed lines indicate the position when the HI-detection fraction reaches 60%. c,d, μHI–M⋆ (c) and μHI–MBH (d) relations. The best-fitted relations for the HI-detected galaxy sample and the BH sample are shown by the black and orange lines, respectively. We also show the μHI–MBH relation for the full galaxy sample with the magenta line in d. e,f, The partial correlation between μHI and M⋆ while controlling for MBH (e), and the partial correlation between μHI and MBH while controlling for M⋆ (f). The corresponding Spearman coefficients are shown in each panel. The median 1σ error bars for the galaxy sample are shown in c and d.

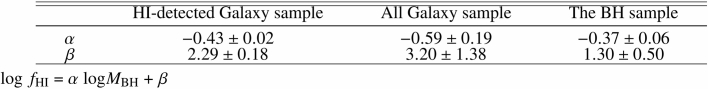

The best-fitted μHI–MBH relation for the HI-detected galaxy sample yields a slope of −0.43 ± 0.02 (Fig. 2, black line), which is steeper than that for the BH sample (−0.37 ± 0.06; Fig. 2, orange line). This is most likely driven by the selection biases in the BH sample, which are more complete and representative at large MBH but poorly sampled at low MBH. Moreover, we also derive an inherent μHI–MBH scaling relation (Fig. 2, magenta line) encompassing both HI detections and non-detections, resulting in a steeper slope (−0.59 ± 0.19) than that for fitting the HI detections exclusively (Extended Data Table 2).

Extended Data Table 2.

Best-fitted linear relations between μHI and MBH for different samples

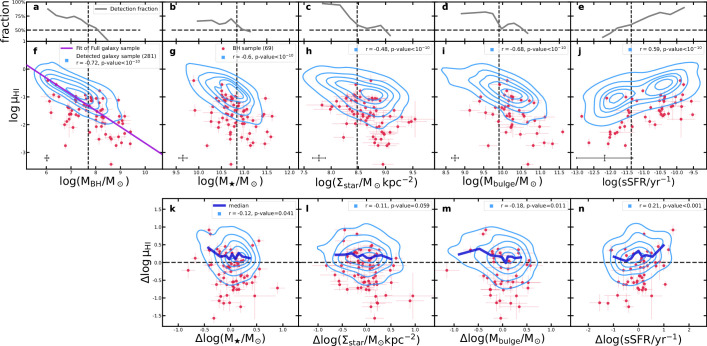

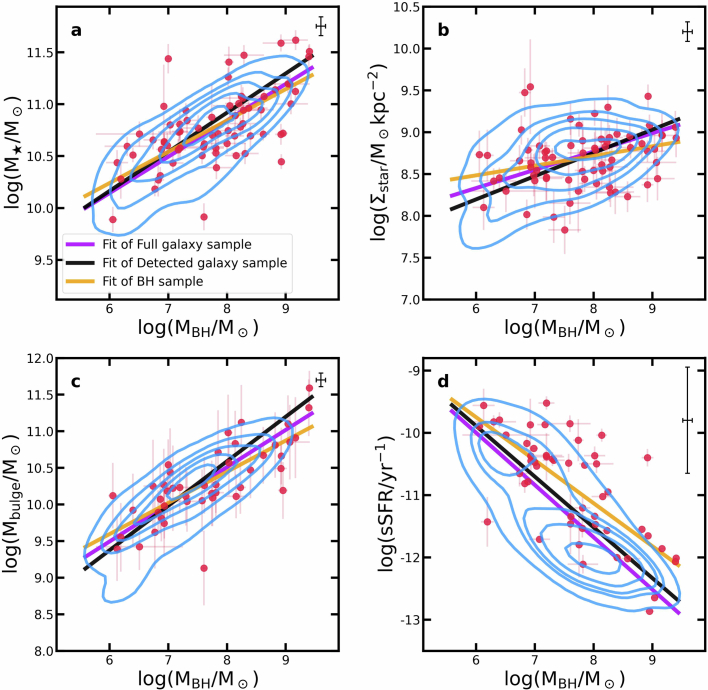

Next, we explore further the correlations between μHI and other main galactic parameters22, including stellar surface densities (Σstar), bulge masses (Mbulge) and specific star formation rates (SSFR), to determine whether MBH is the key parameter in determining μHI in galaxies. Figure 3 compares the correlation among μHI, M⋆, MBH, Σstar, Mbulge and SSFR for the HI-detected galaxy sample. Although significant correlations exist between fHI and all these parameters, after removing their dependence on MBH, all the correlations almost disappear, with negligible Spearman coefficients and zero running medians. We also verify this by using the inherent μHI–MBH relation derived for the full sample in Extended Data Fig. 3, yielding consistent results.

Fig. 3. The impact of MBH on the correlation between μHI and other main galactic parameters.

a–e, The HI-detection fraction along MBH (a) and some other main physical parameters of galaxies, including M⋆ (b), Σstar (c), Mbulge (d) and SSFR (e). The vertical dashed lines indicate the position at which the HI-detection rates hit 60%. f–j, The relation between the parameters MBH (f), M⋆ (g), Σstar (h), Mbulge (i) and SSFR (j) and μHI. The contours denote the distribution of the HI-detected galaxy sample, whereas the filled red circles denote the BH sample with 1σ error bars. The best-fitted μHI–MBH relations for the HI-detected galaxy sample and the BH sample are shown in f by the black and orange lines, respectively. The median 1σ error bars for the galaxy sample are shown. k–n, The relation between the residual in μHI and the residual in other galactic parameters after removing their dependence on MBH: Δlog μHI = log μHI − log μHI(MBH) and Δlog X = log X − log X(MBH) with X representing M⋆ (k), Σstar (l), Mbulge (m) and SSFR (n), and μHI(MBH) and X(MBH) derived from their best-fitted relation with MBH (Extended Data Fig. 2). The solid medium-blue lines in k–n show the running median of the residuals in μHI. The Spearman correlation coefficients for the HI-detected galaxy sample between the corresponding x and y variables are shown in f–n.

Extended Data Fig. 3. The impact of MBH on the correlation between μHI and other major galactic parameters for the full galaxy sample.

Similar as Fig. 3, but with the third row replaced by the relation between the residual in μHI and other galactic parameters after removing their dependence on MBH based on the full sample instead of only the HI-detected ones. The solid medium-blue lines denote the running median of the residuals in μHI. Since the HI-detected samples are always biased compared to the full sample, the running medians exhibits a positive offset compared to zero values(black dashed lines). The median error of the galaxy sample is shown in the lower left in panel (f ~ j). The error bars refer to 1-σ errors. In the top-right corners of the middle and bottom panels, we show the Spearman correlation coefficients for the HI-detected galaxy sample between the corresponding x and y variables.

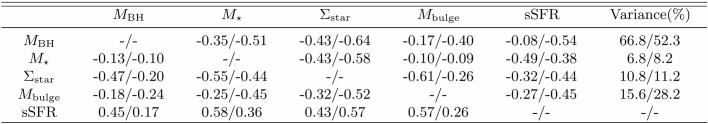

Given that MBH, M⋆, Σstar and Mbulge are all highly correlated, as a further test on the fundamental role of MBH in driving the correlation with μHI, we conduct a partial least squares regression between fHI and the parameter set of MBH, M⋆, Σstar and Mbulge for the HI-detected galaxy sample and the BH sample, which shows that MBH is the most significant predictor parameter of μHI (Methods).

As MBH is proportional to the integrated energy of BHs across their accretion history2,13, our findings offer observational evidence that the accumulated energy from BHs is vital in regulating the accretion and/or cooling of cool gas in galaxies. The immense energy released from the accretion of SMBHs in massive galaxies is known to be at least comparable to the binding energy of host galaxies2,7,23. This energy is thought to significantly affect the accretion of gas onto the galaxy and the cooling of the circumgalactic medium (CGM) and ISM. As M⋆ is closely linked with the inner halo binding energy (total binding energies within effective radii of galaxies)24, , the μHI–MBH relation means , where Eb represents the binding energy of the inner dark matter halo. At the stellar mass range probed by our BH sample, β ≈ 0.6, which is close to the value of α, yielding with α ≈ 0.6.

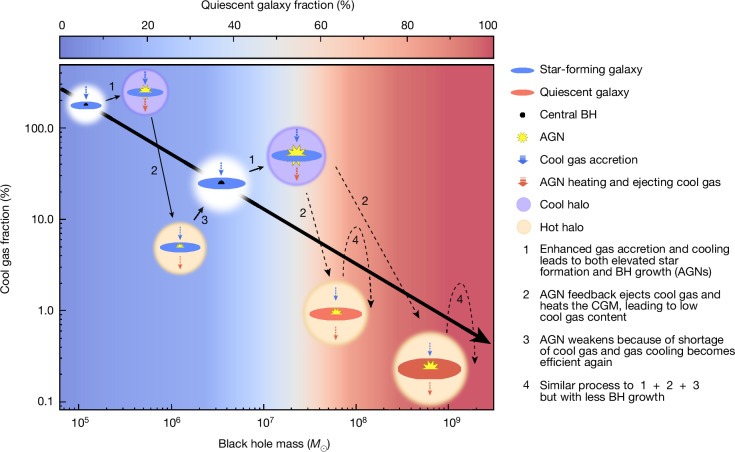

The analysis above indicates that the HI mass in galaxies is determined by the relative strength between the binding energy of the halo and the energy released from BHs (EBH ∝ MBH). The binding energy of the halo determines how much gas can be accreted onto the dark matter halo, whereas the energy from BHs ejects or heats up the gas, preventing it from further cooling. The contest between the two determines how much accreted gas can be eventually cooled and settled down onto the central galaxies. For such a mechanism to be effective, a negative feedback loop involving gas accretion or cooling and BH accretion or feedback would be required5,13. The fact that the accreted cool gas could feed both star formation and BH accretion makes this possible. When gas accretion or cooling is elevated, stronger BH accretion is also triggered, resulting in more energy ejected into the ISM and CGM, which inhibits further cooling or accretion of the cool gas. This eventually brings down the cool gas content (and also the BH accretion rates). Conversely, a lower cool gas content would generally lead to weaker BH accretion with less energy ejection into the ISM and CGM, which will facilitate further cool gas accretion or cooling and increase fHI until it reaches the average relation. The same physical process applies to both star-forming galaxies (SFGs) and quiescent galaxies. The difference is that although both MBH and M⋆ of SFGs can grow substantially through this process, most quiescent galaxies will probably maintain their MBH and M⋆ when they are quenched because of their overall low BH accretion rates and star formation rates. This scenario is shown in Fig. 4.

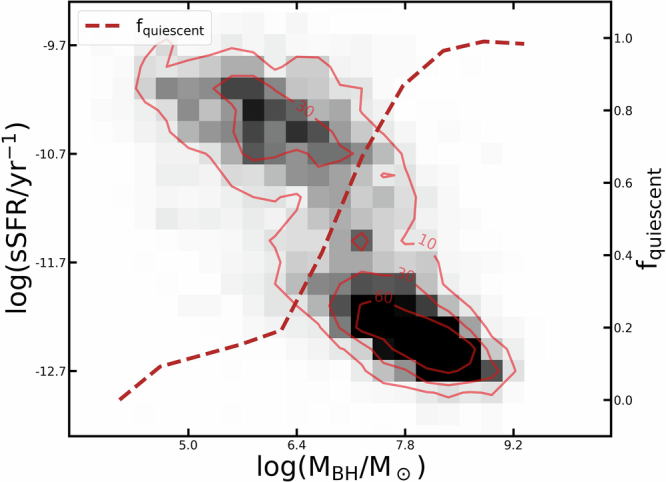

Fig. 4. Schematic of the proposed scenario on how BHs regulate cool gas content in galaxies.

The large arrow indicates the μHI–MBH correlation. The background colour scale indicates the quiescent galaxy fraction as a function of MBH, which shows a sharp increase at MBH ≳ 107.5M⊙ (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 5), corresponding to μHI < 10%. At fixed MBH, galaxies could maintain their μHI at a certain level determined by the relative strength of the inner halo binding energy and MBH. Once gas accretion is enhanced onto galaxies (and their BHs), which increases μHI, MBH will also grow and release additional heating energy that prevents further gas cooling or accretion. This will bring down μHI together with increasing M⋆ by star formation and reach a balance at higher MBH. Although the same process takes place in both SFGs and quiescent galaxies, the growth of MBH or M⋆ should be much less significant in quiescent galaxies than in SFGs, and the large range of MBH among quiescent galaxies (MBH ~ 107−10M⊙) is probably inherited from their different star-forming progenitors when they were quenched.

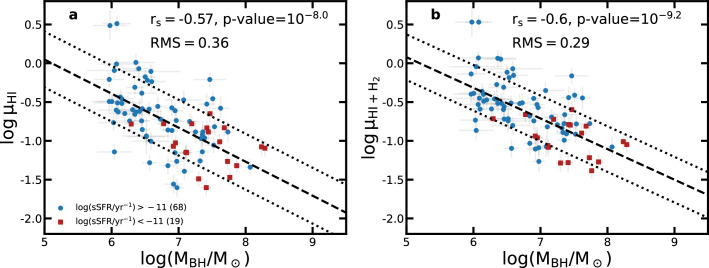

Under this scenario, the correlation between the total gas fraction () and MBH is expected to be even tighter than the μHI–MBH relation. This is because gas cooling from the CGM will probably first cool as HI gas and only later become molecular gas that hosts star formation. In other words, HI gas probes only one phase of the cold gas, whereas AGN feedback should affect the cooling of both atomic and molecular gas in galaxies. This is probably the case. Although the sample with both HI and CO measurements is small, a reduced scatter for the –MBH relation is found compared with the μHI–MBH relation (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 4). Apart from the small sample size, most of the galaxies with both HI and CO measurements are SFGs. Future studies with much larger and more representative galaxy samples with both HI and CO measurements will be needed to fully verify the –MBH relation.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Comparison between the relations of BH masses to the HI gas fraction and to the total gas fraction.

The relation between MBH and HI gas fraction is shown in panel a, and the relation between MBH and total gas fraction is shown in panel b for central galaxies. The blue circles and red squares denote respectively star-forming and quiescent galaxies, which are classified based on their SSFR. Spearman correlation coefficients and the RMS between data and the fitted relations (black dashed lines) are shown in the top-right corners. The error bars refer to 1-σ errors.

As cool gas is the material of star formation, these findings also shed critical light on the intimate connection between the presence of massive BHs and the quiescence of galaxies. It explains well why most quiescent galaxies are present only at MBH ≳ 107.5M⊙ (refs. 10–13) (Extended Data Fig. 5), corresponding to a low level of cool gas content (≲10%), hence minimal star formation rates. The proposed mechanism reconciles the discrepancy between the absence of strong instantaneous negative AGN feedback and the tight correlation between MBH with galaxy quiescence. It is also consistent with empirical models indicating that the contest between dark matter halos and BHs governs the quenching of star formation in galaxies based on various observed galactic scaling relations25.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Relation between SSFR and BH masses for SDSS group central galaxies.

Density map of SDSS group central galaxies is shown in the SSFR-MBH plot. The dashed line denotes the quiescent fraction as a function of MBH. The contours and corresponding numbers denote the galaxy number for each pixel.

Although current studies have been confined to galaxies in the local Universe, the strong correlation across all redshifts between the quiescence of a galaxy and a prominent bulge, a high central stellar density or high central gravitational potential26–30, all of which suggest a large BH, implies that the same scenario may be applied to galaxies at high redshifts as well. Next-generation facilities, such as the Square Kilometer Array and the Next Generation Very Large Array, would be required to confirm this.

Methods

Cosmology

We adopted a Chabrier initial mass function (IMF)31 to estimate star formation rate and assumed cosmological parameters of H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1, ΩM = 0.3, and ΩΛ = 0.7.

Sample selection

The BH sample

The sample for galaxies with directly measured BH masses is primarily from ref. 11, which includes 91 central galaxies collected from refs. 19–21. We excluded 18 sources with BH masses measured with reverberation mapping and kept only those measured with dynamical methods. We then added another 63 galaxies with measured BH masses from recent literature, which were matched with the group catalogue32 of nearby galaxies to select only central galaxies. We obtained the HI flux densities and masses of this sample by crossmatching with the nearby galaxy database, HyperLeda33. Our final sample includes 69 central galaxies with 41 from ref. 11 and the remaining from the compilation of recent literature. In Extended Data Table 3, we list the basic properties of our BH sample.

Extended Data Table 3.

Partial correlation coefficients and variance contributions regarding the correlation between fHI and major galactic parameters

The galaxy sample

The sample for galaxies with HI measurements and indirect BH mass measurements are from the extended GALEX Arecibo SDSS Survey (xGASS; ref. 34) and HI-MaNGA programme35,36, which include HI observations towards a representative sample of about 1,200 and 6,000 galaxies with 109M⊙ < M⋆ < 1011.5M⊙, respectively. The depth of the survey also allows for stringent constraints on the upper limits for the HI non-detections, enabling a comprehensive assessment of fHI for the entire sample. We limited the redshift z < 0.035 to ensure high HI-detection rates even at the highest stellar masses and BH masses. We selected only group central galaxies, which include at least one satellite galaxy in their groups, based on the crossmatch with the group catalogue37–39. Isolated central galaxies lacking any satellites in their groups are discarded because they may have probably suffered from additional environmental effects40. We derived the BH masses for the xGASS and HI-MaNGA samples with their velocity dispersion21 from SDSS DR1737 (σSDSS, and we require σSDSS ≥ 70 km s−1):

| 1 |

Physical parameters of the BH and galaxy sample

Stellar masses

The stellar masses for the galaxy sample are taken from the MPA-JHU catalogue41,42, which are derived from SED fitting based on SDSS data. For the BH sample, because most of them lack the same photometric coverage as the galaxy sample, we derive their stellar masses from their K-band luminosity and velocity dispersion-dependent K-band mass-to-light ratio following ref. 21:

| 2 |

As an accurate determination of σe is not available for all galaxies, we derived σe for the full BH sample from the tight correlation in ref. 21:

| 3 |

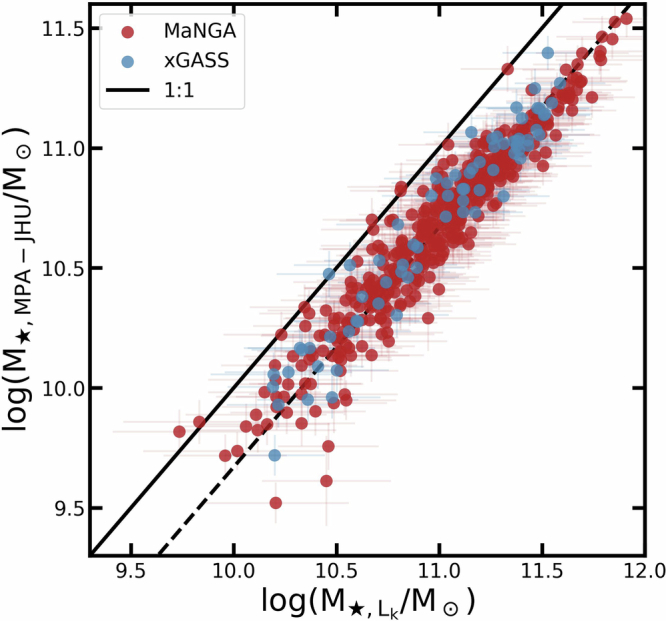

To explore whether there are systematic differences between the two methods, we compare the stellar masses of the galaxy sample taken from the MPA-JHU catalogue and those derived from equation (2). A median mass difference 0.32 dex is found between the two methods (Extended Data Fig. 6), which may be attributed to the tilt from the fundamental plane beyond the mass-to-light ratio, for example, the dark matter component in the effective radius. We corrected these systematic mass differences for the BH sample to match that of the galaxy sample.

Extended Data Fig. 6. The comparison between the stellar masses derived from SED-fitting and those derived based on K-band luminosities.

The SED-based estimation M⋆ is taken from the MPA-JHU catalog and the K-band luminosity based estimation of M⋆ is derived from the relation among M⋆, LK and Re given by Ref. 21. The dashed line denotes the ‘1:1’ line shifted by the mean mass difference of 0.32 dex. The error bars refer to 1-σ error.

HI fraction and upper limits

The HI-detection limit depends not only on the sensitivity but also on the width of the HI line. To obtain more realistic upper limits, we first derived the expected HI line width for each HI non-detection. The width of the HI line indicates the circular velocity of the host galaxy, which should be proportional to the stellar masses. We explored this using the HI detections from the xGASS sample. Extended Data Fig. 1 shows the relation between M⋆ and the observed line width, as well as M⋆ and inclination-corrected line width. It indicates that the inclination-corrected line width is tightly correlated with M⋆, which is further used to derive the expected line width for the HI non-detections. Combining the sensitivity of the HI observations and the expected line width, we derived the upper limits for all the HI non-detections in our BH and galaxy samples.

Morphology

For BH sample, the morphology indicator T is obtained from the HyperLEDA database33. It can be a non-integer because for most objects the final T is averaged over various estimates available in the literature. For the galaxy sample, we classified them in to the early types and late types based on the Sérsic index (from NASA-Sloan Atlas catalogue; NSA: Blanton M.; http://www.nsatlas.org) larger or smaller than 2.

Star formation rates

The specific star formation rates (SSFR) of the galaxy sample are from the MPA-JHU catalogue based on ref. 42. The SSFR for the BH sample is taken from the original reference.

Bulge masses

The bulge information is from refs. 43,44 for the BH sample and galaxy sample, respectively. More specifically, we calculate the bulge mass for the galaxy sample using r-band B/T.

Stellar mass surface density

We calculated the K-band effective radius for both the BH and the galaxy sample according to ref. 21: log Re = 1.16 log RK_R_EFF + 0.23 log qK_BA, where Re is the corrected apparent effective size, RK_R_EFF and qK_BA are K-band apparent effective radius and K-band axis ratio from 2MASS. After converting the apparent sizes to the physical sizes, the stellar mass surface density was derived as .

H2 masses

We collected H2 masses from xCOLD GASS survey18 and ref. 45 for xGASS and MaNGA galaxies, respectively. We acknowledge that at least in the nearby Universe, the molecular-to-atomic gas mass ratio increases only weakly with stellar masses and remains relatively low over a wide stellar mass range, with at 109M⊙ < M⋆ < 1011.5M⊙. We calculate the total gas fractions as . For central galaxies (isolated centrals plus group centrals), we compare the MBH–μHI and MBH– relation in Extended Data Fig. 4. The MBH– relation exhibits a stronger correlation with the smaller scatter than the MBH–μHI relation. We acknowledge that, based on molecular hydrogen gas content traced through dust extinction, previous studies show an MBH– correlation12. Future studies with more direct measurements of molecular hydrogen gas for large samples will be needed to examine in detail whether MBH also plays a fundamental part in regulating the molecular gas content in galaxies.

Quiescent fraction

To estimate the quiescent fraction at different MBH, we selected galaxies from the MPA-JHU catalogue of SDSS galaxies with the same criteria as the galaxy sample, except that we limited the velocity dispersion to greater than 30 km s−1 to cover broader MBH and we made no constraints on the HI detection. We classified the sample galaxies into star-forming and quiescent ones, separated at SSFR = −11. In each MBH bin, the quiescent fraction was calculated as the ratio between the number of quiescent galaxies and that of all galaxies. The result is shown in Extended Data Fig. 5, which is consistent with that of previous work29,46.

Linear least squares approximation

We implemented linear regression for the BH sample and the galaxy sample using Python package LTS_LINEFIT introduced in ref. 47, which is insensitive to outliers and can give the intrinsic scatter around the linear relation with corresponding errors of the fitted parameters.

Linear fitting including upper limits

To incorporate both detections and upper limits in the galaxy sample, we applied the Kaplan–Meier non-parametric estimator to derive the cumulative distribution function at different MBH bins (with Python package Reliability48), and performed 10,000 random draws from the cumulative distribution function at each bin to fit the relation between fgas and MBH. The linear relation and its corresponding errors are taken as the best fitting and standard deviations of these fittings (Extended Data Table 2). The non-detection rate of HI is relatively low across most of the MBH range and becomes significant only for galaxies with the most massive BHs (reaching about 50% at MBH > 108M⊙).

Partial least square regression

To derive the most significant physical parameters in determining μHI statistically, we used the Python package Scikit-learn49 with partial least squares (PLS) Regression function, which uses a non-linear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS)50 algorithm. The PLS algorithm generalizes a few latent variables (or principal components) that summarize the variance of independent variables, which is used to find the fundamental relation between a set of independent and dependent variables. It has advantages in regression among highly correlated predictor variables. It calculates the linear combinations of the original predictor datasets (latent variables) and the response datasets with maximal covariance, then fits the regression between the projected datasets and returns the model:

| 4 |

where X and Y are predictor and response datasets, B is the matrix of regression coefficients and F is the intercept matrix.

We constructed the X and Y matrices as the set of MBH, M⋆, Σstar, Mbulge and the set of μHI. For the BH and galaxy samples, this returns the sample size of 45 and 189, respectively. The optimal number of latent variables (linear combinations of predictor variables) in PLS Regression is determined by the minimum of mean squared error from cross-validation (using function cross_val_predict in Scikit-learn) at each number of components. We find that the optimal number of latent variables for both the BH and the galaxy sample converges to one. Further increasing the number of latent variables yields only a few percentage changes in the mean squared errors, and MBH remains the most significant predictor parameter. Following appendix B in ref. 51, the variance contribution from different parameters to μHI is decomposed as

| 5 |

where Var is a measure of the spread of a distribution. The portion of each parameter variance is shown in the last column of the Extended Data Table 3, which shows that MBH dominates the variance. Further increasing the number of latent variables results only in a few percentage changes in the mean squared errors, and MBH remains the most significant predictor parameter.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41586-024-07821-2.

Acknowledgements

T.W. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, project no. 12173017 and key project no. 12141301), and the China Manned Space Project (CMS-CSST-2021-A07). L.C.H. was supported by the NSFC (11991052 and 12233001), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF0503401) and the China Manned Space Project (CMS-CSST-2021-A04 and CMS-CSST-2021-A06). Z.-Y.Z. acknowledges the support of the NSFC under grants 12173016 and 12041305, the Program for Innovative Talents, Entrepreneur in Jiangsu and the science research grants from the China Manned Space Project (CMS-CSST-2021-A08). F.Y. was supported in part by the NSFC (12133008, 12192220 and 12192223). Q.G. was supported by the NSFC (12192222, 12192220 and 12121003).

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 2. The relation between BH masses and other major galactic parameters for the BH and galaxy sample.

The relation between MBH and M⋆, Σstar, Mbulge, and SSFR for the BH sample (red filled dots) and the full galaxy sample (blue contours) are shown in Panels a, b, c, and d, respectively. The best-fitted relation for the galaxy sample, the full galaxy, and the HI-detected galaxy sample are respectively drawn in solid orange, darkviolet, and black lines in each panel. These relations are used to derive the residuals of the corresponding galactic parameters after controlling for MBH in the bottom row of Fig. 3, and Extended Data Fig. 3. The median error of the galaxy sample is shown in the upper right in each panel. The error bars refer to 1-σ errors.

Author contributions

T.W. initiated the study, led the first discoveries and authored most of the text. K.X. enlarged the sample and consolidated the results with a more in-depth analysis under the supervision of T.W.; Y. Wu helped construct the initial sample. Y.S., D.E., L.C.H., Z.-Y.Z., Q.G., Y. Wang, C.S., F.Y., X.X. and K.W. contributed to the overall interpretation of the results and various aspects of the analysis.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Bryan Terrazas and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All data used in this paper are publicly available, and the key physical parameters of the BH sample are summarized in Extended Data Table 1.

Code availability

All codes used in the paper are publicly available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41586-024-07821-2.

References

- 1.Ho, L. C. Nuclear activity in nearby galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.46, 475–539 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silk, J. & Rees, M. J. Quasars and galaxy formation. Astron. Astrophys.331, L1–L4 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balogh, M. L., Pearce, F. R., Bower, R. G. & Kay, S. T. Revisiting the cosmic cooling crisis. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.326, 1228–1234 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cattaneo, A. et al. The role of black holes in galaxy formation and evolution. Nature460, 213–219 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabian, A. C. Observational evidence of AGN feedback. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.50, 455–489 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Matteo, T., Springel, V. & Hernquist, L. Energy input from quasars regulates the growth and activity of black holes and their host galaxies. Nature433, 604–607 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiolino, R. et al. Evidence of strong quasar feedback in the early Universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.425, L66–L70 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicone, C. et al. Massive molecular outflows and evidence for AGN feedback from CO observations. Astron. Astrophys.562, A21 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bluck, A. F. L. et al. Bulge mass is king: the dominant role of the bulge in determining the fraction of passive galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.441, 599–629 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terrazas, B. A. et al. Quiescence correlates strongly with directly measured black hole mass in central galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett.830, L12 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terrazas, B. A., Bell, E. F., Woo, J. & Henriques, B. M. B. Supermassive black holes as the regulators of star formation in central galaxies. Astrophys. J.844, 170 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piotrowska, J. M., Bluck, A. F. L., Maiolino, R. & Peng, Y. On the quenching of star formation in observed and simulated central galaxies: evidence for the role of integrated AGN feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.512, 1052–1090 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bluck, A. F. L. et al. The quenching of galaxies, bulges, and disks since cosmic noon: a machine learning approach for identifying causality in astronomical data. Astron. Astrophys.659, A160 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownson, S., Bluck, A. F. L., Maiolino, R. & Jones, G. C. What drives galaxy quenching? A deep connection between galaxy kinematics and quenching in the local Universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.511, 1913–1941 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley, F. et al. The mean star formation rates of unobscured QSOs: searching for evidence of suppressed or enhanced star formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.472, 2221–2240 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulze, A. et al. No signs of star formation being regulated in the most luminous quasars at z ~ 2 with ALMA. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.488, 1180–1198 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shangguan, J., Ho, L. C., Bauer, F. E., Wang, R. & Treister, E. AGN feedback and star formation of quasar host galaxies: insights from the molecular gas. Astrophys. J.899, 112 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saintonge, A. et al. xCOLD GASS: the complete IRAM 30 m legacy survey of molecular gas for galaxy evolution studies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.233, 22 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kormendy, J. & Ho, L. C. Coevolution (or not) of supermassive black holes and host galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.51, 511–653 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saglia, R. P. et al. The SINFONI Black Hole Survey: the black hole fundamental plane revisited and the paths of (co)evolution of supermassive black holes and bulges. Astrophys. J.818, 47 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Bosch, R. C. E. Unification of the fundamental plane and super massive black hole masses. Astrophys. J.831, 134 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saintonge, A. & Catinella, B. The cold interstellar medium of galaxies in the local Universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.60, 319–361 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bluck, A. F. L. et al. On the co-evolution of supermassive black holes and their host galaxies since z = 3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.410, 1174–1196 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi, Y. et al. A universal relationship between stellar masses and binding energies of galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.507, 2423–2431 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, Z. et al. Quenching as a contest between galaxy halos and their central black holes. Astrophys. J.897, 102 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell, E. F. et al. What turns galaxies off? The different morphologies of star-forming and quiescent galaxies since z ~ 2 from CANDELS. Astrophys. J.753, 167 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, T. et al. CANDELS: correlations of spectral energy distributions and morphologies with star formation status for massive galaxies at z ~ 2. Astrophys. J.752, 134 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang, J. J., Faber, S. M., Koo, D. C. & Dekel, A. A link between star formation quenching and inner stellar mass density in Sloan Digital Sky Survey central galaxies. Astrophys. J.776, 63 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bluck, A. F. L., Piotrowska, J. M. & Maiolino, R. The fundamental signature of star formation quenching from AGN feedback: a critical dependence of quiescence on supermassive black hole mass, not accretion rate. Astrophys. J.944, 108 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bluck, A. F. L. et al. Galaxy quenching at the high redshift frontier: a fundamental test of cosmological models in the early Universe with JWST-CEERS. Astrophys. J.961, 163 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chabrier, G. Galactic stellar and substellar initial mass function. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac.115, 763–795 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, Y. et al. Galaxy groups in the 2MASS Redshift Survey. Astrophys. J.832, 39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makarov, D., Prugniel, P., Terekhova, N., Courtois, H. & Vauglin, I. HyperLEDA. III. The catalogue of extragalactic distances. Astron. Astrophys.570, A13 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catinella, B. et al. xGASS: total cold gas scaling relations and molecular-to-atomic gas ratios of galaxies in the local Universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.476, 875–895 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masters, K. L. et al. H i-MaNGA: H i follow-up for the MaNGA survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.488, 3396–3405 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stark, D. V. et al. H i-MaNGA: tracing the physics of the neutral and ionized ISM with the second data release. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.503, 1345–1366 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdurro’uf, et al. The seventeenth data release of the Sloan Digital Sky Surveys: complete release of MaNGA, MaStar, and APOGEE-2 data. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.259, 35 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang, X. et al. Galaxy groups in the SDSS DR4. I. The catalog and basic properties. Astrophys. J.671, 153–170 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janowiecki, S. et al. xGASS: gas-rich central galaxies in small groups and their connections to cosmic web gas feeding. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.466, 4795–4812 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, K., Peng, Y. & Chen, Y. Dissect two-halo galactic conformity effect for central galaxies: the dependence of star formation activities on the large-scale environment. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.523, 1268–1279 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kauffmann, G. et al. Stellar masses and star formation histories for 105 galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.341, 33–53 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brinchmann, J. et al. The physical properties of star-forming galaxies in the low-redshift Universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.351, 1151–1179 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohn, T., Canalizo, G., Satyapal, S. & Pfeifle, R. W. The discovery of a hidden broad-line AGN in a bulgeless galaxy: Keck NIR Spectroscopic Observations of SDSS J085153.64+392611.76. Astrophys. J.899, 82 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simard, L., Mendel, J. T., Patton, D. R., Ellison, S. L. & McConnachie, A. W. A catalog of bulge+disk decompositions and updated photometry for 1.12 million galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.196, 11 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wylezalek, D. et al. MASCOT: an ESO-ARO legacy survey of molecular gas in nearby SDSS-MaNGA galaxies – I. First data release, and global and resolved relations between H2 and stellar content. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.510, 3119–3131 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terrazas, B. A. et al. The relationship between black hole mass and galaxy properties: examining the black hole feedback model in IllustrisTNG. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.493, 1888–1906 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cappellari, M. et al. The ATLAS3D project – XV. Benchmark for early-type galaxies scaling relations from 260 dynamical models: mass-to-light ratio, dark matter, fundamental plane and mass plane. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.432, 1709–1741 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reid, M. MatthewReid854/reliability. v.0.5.7. Zenodo 10.5281/zenodo.5030847 (2021).

- 49.Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.12, 2825–2830 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindgren, F., Geladi, P. & Wold, S. The kernel algorithm for PLS. J. Chemom.7, 45–59 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oh, S. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: the difference between ionized gas and stellar velocity dispersions. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.512, 1765–1780 (2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this paper are publicly available, and the key physical parameters of the BH sample are summarized in Extended Data Table 1.

All codes used in the paper are publicly available.