Key Clinical Message

Polypoid endometriosis is a rare manifestation of endometriosis, which may mimic pelvic cancer. This subtype commonly encountered in post‐menopausal women may be wrongly mistaken for a neoplasm on clinical, radiological, perioperative or pathologic assessments leading to inadequate treatment.

Keywords: endometriosis, pelvic cancer, polypoid endometriosis, post‐menopausal

1. INTRODUCTION

Polypoid endometriosis is a rare manifestation of endometriosis, which may mimic pelvic cancer. This subtype, commonly encountered in post‐menopausal women, may be wrongly mistaken for a neoplasm on clinical, radiological, perioperative or pathologic assessments leading to inadequate treatment. We report the case of a 68‐year‐old woman who presented with a massive polypoid endometriosis of the vaginal stump mimicking an invasive pelvic cancer. She had a previous hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy for endometriosis 20 years ago. Based on clinical and radiological aspects, the patient underwent a carcinologic‐type surgery with posterior pelvectomy and peritoneal resections. The pathological examination ruled out malignancy by revealing deep florid endometriosis with polypoid features.

To date, this rare form of benign disease is insufficiently known and misdiagnosed by gynecologists, leading to excessive surgical procedure exposing the patient to unnecessary morbidity. This didactic short report aims to sensitize clinicians to this condition and provide them with some clinical and radiological key elements to facilitate the diagnosis. Clinicians should consider it as a differential diagnosis of pelvic cancer especially with patients having a medical history of endometriosis in the pre‐menopausal period.

2. CASE HISTORY

A 68‐year‐old patient with a history of insulin‐dependent type 2 diabetes, high‐blood pressure, hypothyroidism, and hypercholesterolemia consulted for post‐menopausal bleeding which had started 2 years ago and was associated with discomfort when sitting. She was G2P2 with two vaginal deliveries and underwent total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy and appendectomy by laparotomy at 48 years old for deep pelvic endometriosis discovered on a latero‐uterine mass corresponding to multiple endometriomas. Anatomopathological analysis of the surgical specimens confirmed adenomyosis with extensive ovarian endometriosis and ruled out malignant tumor.

3. METHODS (DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, INVESTIGATIONS, AND TREATMENT)

She had been on menopausal hormone replacement therapy for 10 years. Clinically, there was a vaginal stump retraction with no visible lesion. Vaginal examination revealed an infiltrating mass located 4 cm from the anus that infiltrated left uterosacral ligament and vaginal stump. Rectal examination was normal. Ultrasound revealed a well‐limited heterogeneous tissue mass measuring 45 × 38 × 29 mm located on the vaginal stump and close to the sigmoid muscularis. There was also a 28 × 11 × 15 mm node in the lower rectum involving the muscularis and submucosa. MRI revealed a both solid and cystic lesion of the vaginal stump with heterogeneous T2WI high signal intensity (Figure 1). Small hemorrhagic components have been observed with T1WI high signal intensity and homogeneous enhancement was present after the injection of a contrast agent. The lesion was close to posterior vaginal stump and rectovaginal septum endometriotic node with anterior transmural involvement of the midrectum. A thoraco‐abdomino‐pelvic CT scan revealed no distant abnormalities. Biologically, CEA, CA19‐9, alpha feto protein, Bhcg, and CA15‐3 were normal. CA125 was slightly increased up to 48 UI/mL. During laparoscopic exploration no sign of peritoneal carcinosis was found except for a 2‐ to 3‐cm node in the anterior pelvic peritoneum. The node was removed completely with no evidence of peritoneal carcinosis on the extemporaneous exam. A mass in the vaginal stump with grayish tan colored soft tissue resembling polypoid and cauliflower‐like structure was found. The mass induced the rectosigmoid to retract. Laparoscopic excision was deemed unsafe to perform without incising the tumor hence a median laparotomy was performed. The pelvic exploration overturned peritoneal carcinosis lesion. A posterior monobloc pelvectomy including sigmoidectomy and resection of its corresponding meso was performed. The rectum was mobilized to both sides and bilateral ureterolysis was practiced. The peritoneum was opened anteriorly and laterally to separate the bladder until a healthy zone in the vaginal area was reached. The lateral rectal dissection was continued until healthy recto‐vaginal space was reached. The entire tumor mass was progressively dissected. Colorectal continuity was re‐established for end‐to‐end anastomosis using the Knit technique. A post‐operative cerebral CT scan was performed in search of a hormone‐secreting lesion and returned normal. Hormonal assays for FSH, LH, and estradiol showed a menopause profile.

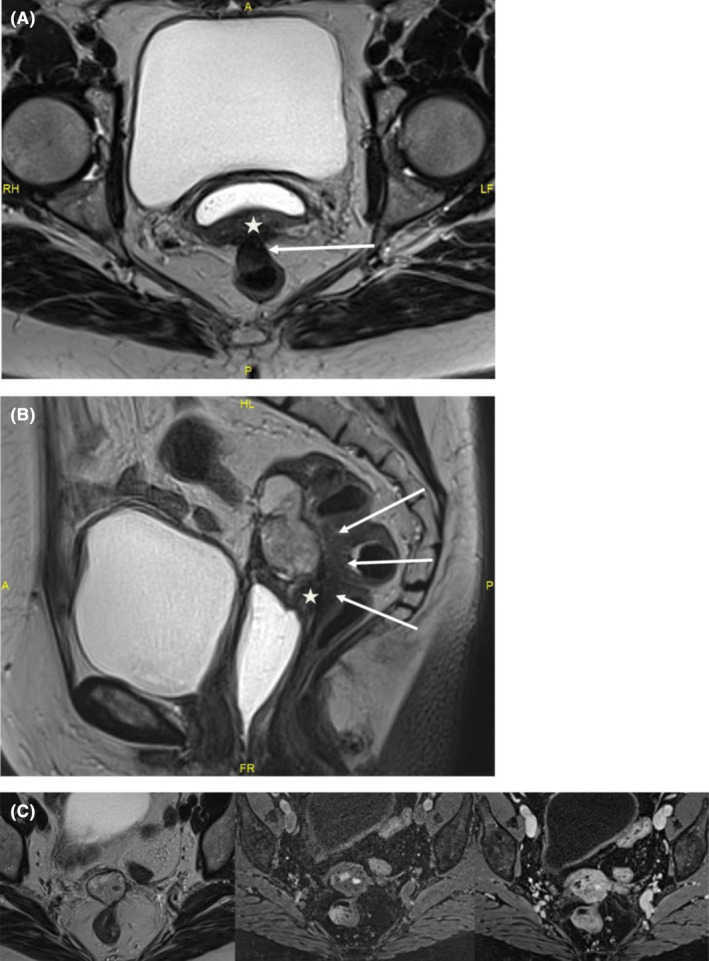

FIGURE 1.

MRI: (A) T2W axial image: endometriotic nodule of posterior vaginal wall (star) with contiguous transmural digestive involvement (arrows). (B) T2W sagittal image: the lesion is close to a fibrous endometriotic nodule of the posterior vaginal fornix and of the rectovaginal septum (star). Transmural involvement of the anterior wall of the middle rectum with typical “mushroom cap” in the sagittal plane (arrows). (C) T2W‐T1W‐T1W post contrast axial images: mainly solid lesion of the vaginal stump in heterogeneous T2 hypersignal, with hemorrhagic remodeling in T1 hypersignal, homogeneous enhancement after contrast injection.

4. RESULTS: PATHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

4.1. Macroscopic description

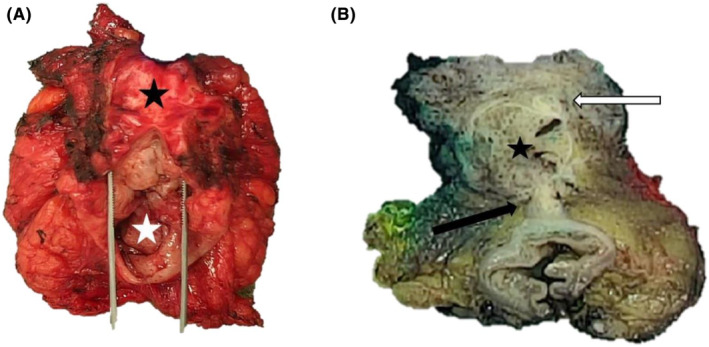

Gross findings of the posterior pelvectomy revealed a 38‐mm diameter, well‐demarcated, firm and tan round‐cystic mass with hemorrhagic and myxoid changes protruding through the posterior vaginal and the anterior rectal walls. Parts of macroscopic findings are illustrated in Figure 2. The associated peritoneal resection specimen showed a homogeneous, white, firm and microcystic‐polypoid mass measuring 20 mm diameter.

FIGURE 2.

Macroscopic photographs of the posterior pelvectomy with endometriosis lesions before and after formalin fixation. Gross findings of the resected specimen at first examination before fixation, with the vaginal wall (black star) attached to the rectum (white star) (A). Post‐fixation transversal section revealed a firm and gray‐tan, round cystic mass (star), located between and protruding through the vaginal chorion (white arrow) and the anterior rectal wall (black arrow) (B).

4.2. Histologic description

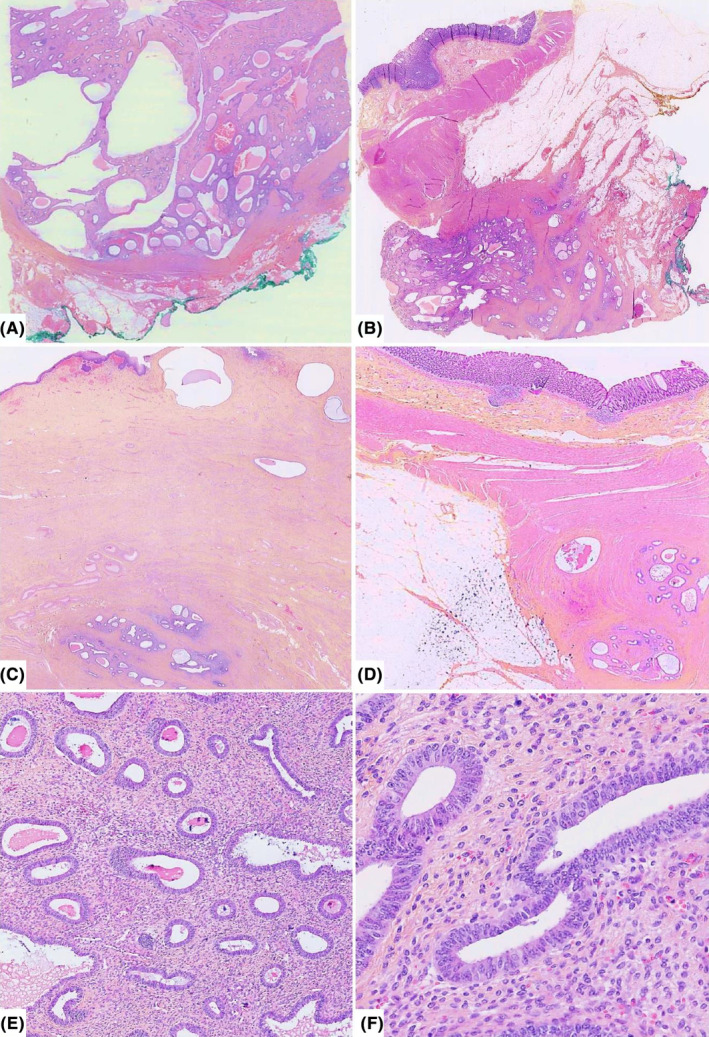

Pathological examination revealed exophytic, polypoid and diffuse areas of abundant cellular fibrous stroma with thick‐walled blood vessels containing numerous tubular glands. These narrow or dilated and sometimes cystic glands were lined by pseudostratified columnar basophilic epithelium devoid of cytonuclear atypia with low mitotic activity consistent with benign endometrial glands. Focal tubal metaplasia and foci of stromal hemorrhage characteristic of endometriosis were also identified. These lesions diffusely extended to the vaginal chorion, the external muscularis propria of the rectal wall, and the peritoneum. Furthermore, neither leaf‐like (phyllodes‐like) pattern nor periglandular cuffs nor stromal cell atypia were seen hence ruling out adenosarcoma as no evidence of malignancy was found. The diagnosis of polypoid or deep florid endometriosis with simple non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia was definitively retained. The main morphological findings are illustrated in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Representative H&E histologic sections of deep florid endometriosis involving the vagina and the rectum at different magnifications. Lesions forming polypoid and cystic masses reminding benign endometrial polyp (A and B), with mural infiltrative aspects of the vaginal chorion and the anterior rectal wall (C and D), respectively, at low magnification. Mild and high power views show endometrial‐type glands dispersed within an abundant fibrous stroma with focal hemorrhage (E) and lined by pseudostratified columnar cells without cytonuclear atypia and low mitotic activity (F).

5. DISCUSSION

Endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrial‐type tissue including glands and stroma outside of the normal uterine cavity. This condition occurs approximately in 10%–15% of patients in pre‐menopausal period and could be responsible for pelvic pain and infertility. 1

Polypoid endometriosis is a rare distinctive variant of endometriosis forming large and often multiple polypoid masses. It was first described in 1980 by Mostoufizadeh and Scully and the largest case series published by Parker et al. only included 24 cases. 2 Since this review, 11 cases of polypoid endometriosis in post‐menopausal patients have been reported in the literature (Table 1). This subtype of endometriosis is most frequently found in peri‐ or post‐menopausal patients with a mean age at diagnosis of 52.5 years old. 2 Localizations are mainly pelvic involving the vagina, the cervix or ovaries, but can also be peritoneal notably in the Douglas pouch. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Clinical presentation may mimic a neoplastic pathology particularly in post‐menopausal patients even though it is a benign diagnosis. 3 The progression can be fast and recur after surgical removal with true invasive cancer development in very rare cases. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

TABLE 1.

Polypoid endometriosis: literature cases in post‐menopausal women between 2004 and 2024.

| Article | Age (years) | Localization | Symptoms | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laird, et al. 17 | 80 | Pelvic | Venous thrombosis of the deep femoral vein, embolism vaginal bleeding | Radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy, and pelvic lymph node dissection |

| Santos, et al. 18 | 70 | Retroperitoneal, rectal serosa | Incidentally | Surgical excision |

| Hansen, et al. 19 | ||||

| Case 1 | 57 | Ovarian mass | Abdominal fullness | Surgical excision |

| Case 2 | 81 | Ovarian mass | Post‐menopausal bleeding and abdominal fullness | Focal endometrioid adeno‐carcinoma arising in polypoid endometriosis. Surgical excision, surgical staging |

| Choi, et al. 20 | 66 | Ovarian | Incidentally | Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy |

| Gunawardane and Allen 11 | 50 | Pouch of Douglas | Pelvic pain | Surgical excision |

| Jaegle, et al. 14 | 62 | Pelvic carcinomatosis | Hematuria | Radical tumor cytoreduction |

| Han, et al. 21 | 58 | Rectum/sigmoid | Chronic diarrhea and post‐menopausal uterine bleeding | Laparotomy with removal of the rectosigmoid mass, proctosigmoidectomy with ileostomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo‐oopherectomy |

| Zhuang, et al. 22 | 62 | Ureteric | Haematuria, hydroureteronephrosis | Ureterectomy along with partial cystectomy, hormonal therapy |

| Ghafoor, et al. 3 | 60 | Pelvic | Incidentally | Discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy |

| Stuparich, et al. 23 | 60 | Peritoneal carcinomatosis | Incidentally | Laparoscopic radical cytoreduction, discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy |

In our case, the patient's age and the clinical and radiological presentation pointed to a cancer etiology. We prescribed usual pelvic neoplasia tumor markers (ovarian, uterine, peritoneal, and digestive tumors) in order to establish an initial pre‐operative diagnosis. Oncological etiology remained an important probability given the slightly elevation of CA125. As recommended in the literature, the performed surgery took into account the suspicion of cancer and required laparotomy and pelvectomy to obtain R0 resection margins (Table 1). As we faced these unexpected findings during surgery we, therefore, decided to perform a brain CT scan to complete the extensive workup and to ensure that a secretory brain tumor was not overlooked.

Clinical examination is often poor in differentiating this subtype of endometriosis to a true malignancy though some radiologic signs can help to guide the gynecologist. Indeed a pelvic lesion with a black rim sign in the MRI should bring to mind this diagnosis. No diffusion restriction and late contrast‐enhancement pattern may reflect its benign nature. 8

Although some radiologic findings can help the gynecologist, only pathological examination can definitively rule out malignancy and confirm the diagnosis. Unlike some cases in the literature, we were unable to obtain a biopsy of the lesion prior to surgical management because of its location. 11 Despite the worrying macroscopic appearance, histological findings are most of time characteristic of endometriosis. Microscopic examination shows endometrial glands lined by a glandular pseudostratified columnar basophilic epithelium embedded in a variable amount of an endometrial‐type stroma. These structures are characteristically organized on an abundant fibrous background with thick‐walled blood vessels resembling an endometrial polyp. These lesions can show a wide range of glandular density and variety of architectural pattern with frequent metaplastic changes and sometimes some degree of hyperplasia and/or cytological atypia. Rare malignancy such as endometrioid adenocarcinoma have been reported to arise in polypoid endometriosis. 12

The main differential diagnosis to evoke and eliminate these aspects, associating endometrial‐type gland and stroma, is the Mullerian adenosarcoma. Indeed, the dark appearance of endometrial stroma around glandular structures can be misinterpreted as periglandular stromal condensation characteristic of adenosarcoma. However, in polypoid endometriosis, no leaf‐like (phyllodes‐like) pattern or stromal cell atypia are seen, contrary to typical adenosarcoma. The distinction between both diagnoses can be very challenging in some cases.

Endometriosis is one the most common benign gynecologic disease in pre‐menopausal women. Even if its hormonal dependence is now well recognized, its precise pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Peritoneal endometriosis could be due to diffusion of endometrial tissue in the peritoneal cavity by conventional retrograde menstruations. 13 However, this endometrial tissue implants and grows only in a small subset of women under the influence of hormone secretions. This hypothesis can explain the evolution of endometriosis in pre‐menopausal women in which hormonal secretion cycles can regulate the disease development. For older post‐menopausal patients, hormone based treatments uses, such as combined estrogen‐progestin therapy or tamoxifen among others and synchronous secretory ovarian tumors like thecomas could be partly responsible for stimulation and growth of endometriosis. 2 , 13 , 14 Moreover, in a recent study, Syrcle et al. show an increased local estrogen production in polypoid endometriosis due to an altered gene expression profile in pathologic tissue. 15 These results can also explain the persistence and development of polypoid endometriosis in post‐menopausal period. This hypothesis is further supported by others. 16

6. CONCLUSION

Polypoid endometriosis is a rare and distinctive variant of endometriosis, often with polymorphous and disturbing clinical presentation, that may mimic pelvic malignancies. This uncommon diagnosis, most frequently observed in post‐menopausal women, must be known by gynecologists and pathologists and taken into account in differential diagnoses of pelvic cancer. Our case highlights the importance for gynecologists and radiologists to raise this uncommon diagnostic hypothesis particularly in patients with a past history of endometriosis in pre‐menopausal period to adapt their surgical procedure in order to avoid excessive resection.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Katia Mahiou: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing – original draft. Fara Tanjona Harizay: Resources; validation. Morgane Lanouziere: Resources; validation; writing – original draft. Olivia Martz: Resources; writing – review and editing. Laurence Filipuzzi: Resources. Jean‐Marc Rousselet: Resources. Laurent Martin: Validation. Laurent Arnould: Validation. Mathilde Funes De La Vega: Resources. Anthony Bergeron: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; resources; supervision; validation; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patient who agreed to share data from her medical record and signed a consent for publication about her case.

Mahiou K, Harizay FT, Lanouziere M, et al. Polypoid endometriosis—An exceptional subtype of endometriosis mimicking an aggressive pelvic cancer. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e9343. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.9343

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parker RL, Dadmanesh F, Young RH, Clement PB. Polypoid endometriosis: a clinicopathologic analysis of 24 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(3):285‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ghafoor S, Lakhman Y, Park KJ, Petkovska I. Polypoid endometriosis: a mimic of malignancy. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45(6):1776‐1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marguerie M, Howell J, Belland L. Vaginal polypoid endometriosis. CMAJ. 2023;195(17):E620‐E621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaiman S, Gundabattula SR, Pochiraju M, Sangireddy JR. Polypoid endometriosis of the cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(4):915‐920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsai C, Huang SH, Huang CY. Polypoid endometriosis—a rare entity of endometriosis mimicking ovarian cancer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;58(3):328‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamada Y, Miyamoto T, Horiuchi A, Ohya A, Shiozawa T. Polypoid endometriosis of the ovary mimicking ovarian carcinoma dissemination: a case report and literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1426‐1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Bando Y, Harada M. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of polypoid endometriosis and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022;48(10):2583‐2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mostoufizadeh M, Scully RE. Malignant tumors arising in endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23(3):951‐963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giannella L, Marconi C, Di Giuseppe J, et al. Malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer. 2021;13(16):4026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gunawardane DN, Allen PW. Selected case from the Arkadi M. Rywlin International Pathology Slide Club: polypoid endometriosis in the Pouch of Douglas in a perimenopausal woman. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22(5):331‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferraro LR, Hetz H, Carter H. Malignant endometriosis; pelvic endometriosis complicated by polypoid endometrioma of the colon and endometriotic sarcoma; report of a case and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1956;7(1):32‐39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart CJR, Bharat C. Clinicopathological and immunohistological features of polypoid endometriosis. Histopathology. 2016;68(3):398‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaegle WT, Barnett JC, Stralka BR, Chappell NP. Polypoid endometriosis mimicking invasive cancer in an obese, postmenopausal tamoxifen user. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;22:105‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Syrcle SM, Pelch KE, Schroder AL, et al. Altered gene expression profile in vaginal polypoid endometriosis resembles peritoneal endometriosis and is consistent with increased local estrogen production. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2011;71(2):77‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bulun SE, Gurates B, Fang Z, et al. Mechanisms of excessive estrogen formation in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;55(1–2):21‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laird LA, Hoffman JS, Omrani A. Multifocal polypoid endometriosis presenting as huge pelvic masses causing deep vein thrombosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(5):561‐564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santos LD, Carter J, Killingsworth M. Polypoid endometrioma of the rectal serosa and retroperitoneal endometriosis in a 70‐year‐old woman. Pathology (Phila). 2004;36(1):91‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen K, Simon RA, Lawrence WD, Quddus MR. Unilateral pelvic mass presenting in postmenopausal patients: report of two unusual cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012;16(4):298‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi IH, Jin SY, Jeen YM, Lee JJ, Kim DW. Tamoxifen‐associated polypoid endometriosis mimicking an ovarian neoplasm. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(4):327‐330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Han K, Li X, Bhargava R, Taylor S, Lee K, Yadav D. Polypoid endometriosis presenting as a colonic mass. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhuang L, Eisinger D, Jaworski R. A case of ureteric polypoid endometriosis presenting in a post‐menopausal woman. Pathology (Phila). 2017;49(4):441‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stuparich MA, Behbehani S, Nahas S. Polypoid endometriosis mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis in a postmenopausal woman: a laparoscopic perspective. J Obstet Gynaecol Can JOGC J Obstet Gynecol Can JOGC. 2022;44(9):941‐942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.