Abstract

Background

Police work can be sedentary and stressful, negatively impacting health and wellbeing. In a novel co-creation approach, we used the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) and Double Diamond (DD) design framework to guide the collaborative design and development of a sedentary behavior intervention in the control rooms of two British police forces.

Methods

Multiple stakeholders participated in four phases of research. In Phase 1, a literature review, focus groups (n = 20) and interviews (n = 10) were conducted to ‘discover’ the relationship between physical activity and wellbeing in the police. In Phase 2, a steering group consolidated Phase 1 findings to ‘define’ a specific behavior for intervention. Phases 3 and 4 ‘developed’ the intervention across six workshops with control room workers and six steering group workshops.

Results

The co-creation process identified contextual sedentary behavior as the target behavior, driven by behavioral regulation, social influence and social norms. The sedentary behavior intervention targeted these drivers and aimed to engage control room workers in short bursts of physical activity throughout their shifts. Key intervention features targeted involvement of staff in decision-making and embedding physical activity into work practices.

Conclusions

The BCW and DD can be combined to co-create evidence-based and participant-informed interventions and translate science into action.

Keywords: Behavior Change Wheel, co-creation, intervention development, police, sedentary behavior, wellbeing

Introduction

Policing is a high stress occupation that can negatively impact the health and wellbeing of the workforce.1 The Police Covenant2 outlined a UK Government legislative pledge to improve the working experience of people in policing. To fulfil the Police Covenant, evidence-based approaches to supporting wellbeing are needed.3 Using a co-creation approach, this research explored stress and wellbeing in two British police forces and aimed to develop a sedentary behavior intervention with police control room workers, to support their wellbeing.

Co-creation is a collaborative approach to research in which participants (e.g. stakeholders, participants with lived experience, end-users) are equal partners in the research process.4 In line with nominated definitions of co-creation,5 the term is used in this study to encompass the involvement of police stakeholders in decision-making throughout the research process, including co-design methods within the broader co-creation process. A quantitative exploration of stress and wellbeing in the police workforce6 identified that police workers who engaged in the World Health Organization7 recommendations for physical activity had significantly improved relationships between perception of work demands, organizational stress and wellbeing. Consequently, it was police stakeholders’ priority to focus on a sedentary area of their workforce, where wellbeing could potentially be supported through increased physical activity behavior. Police control rooms were identified as a sedentary area of policing, where employees (e.g. emergency call handlers, dispatch officers) work in a unique environment and are susceptible to experiencing high work-related stress, physical ill-health and mental ill-health.1,8 In other areas of policing, physical activity interventions have benefitted police officer mental health.9 Physical activity interventions often target interdependent behaviors under the umbrella term of ‘physical activity’ (e.g. interruptions in sedentary behavior are replaced with light physical activity).10 Intervention descriptions and development processes are, however, not fully reported; resulting in minimal understanding of the mechanisms through which physical activity interventions can successfully be translated into action in a police context.

Intervention development

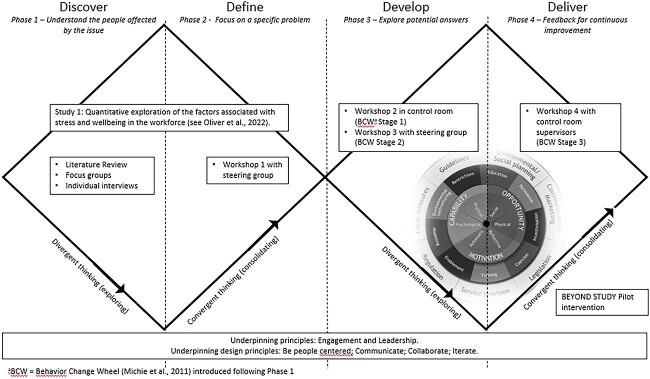

Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for complex intervention research11 emphasizes the need to describe clearly the development process12 and the steps taken to understand the context into which interventions are to be implemented.13 Despite this, interventions often fail to adequately report the process of intervention development.14 Using a co-creation approach, our research provides new knowledge on the processes of developing a context-specific intervention. Guided by the Double Diamond framework (DD),15 our research was underpinned by divergent (exploration) and convergent (consolidation) thinking processes and a set of design principles that emphasized the importance of relationships (e.g. be people centered, communicate). The DD framework (see Fig. 1) is widely used to guide how researchers move from understanding a problem to working with end-users to answer it.16

Fig. 1.

Intervention development process guided by DD framework.15

Appropriate use of theory is another core element of complex interventions within the MRC guidance.11 In our research, to systematically develop a theory-based intervention, the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW)17 was followed. The BCW synthesizes across behavior change theories to provide a framework that has been used with collaboration approaches aiming to change physical activity and sedentary behavior.18,19 The Capability, Opportunity and Motivation model (COM-B)20 sits at the center of the BCW and assists consideration of context-specific behavioral influences in intervention development. Starting with a COM-B analysis, researchers then follow the BCW to target the contextually relevant theoretical constructs in their interventions. To make the theoretical constructs within the intervention clear, the mechanisms of action (MoAs) tool21 can be used alongside the BCW to develop program theory (understanding how and why the intervention might be effective). We, therefore, integrated the DD and BCW and, by doing so, provided a novel co-creation and theory-based framework for the development of a sedentary behavior intervention with police control-room workers, something required within the extant behavior change literature.13,22

Method

Research design

Four phases were undertaken that followed the Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver model of the DD (see Fig. 1). The Discover phase involved exploring wellbeing in the police and understanding participants using a focus group and semi-structured interview research design. The insight gathered was consolidated in the Define phase to focus on a specific behavior and context. In the Develop phase, a range of context-specific interventions were explored, to produce a framework of an intervention in the Deliver phase.

Participants

Two police forces were recruited to the study. Force A was a large, urban police force (circa 5000 employees). Force B was a smaller, rural police force (circa 2500 employees). Multiple levels of stakeholders from each police force participated in the multiphase research process. These included:

Steering group: Comprised two members of the research team and a member of senior management from each police force (n = 4). Other senior leaders co-opted in over the 7-year research period. The steering group met bi-monthly and were engaged in all four phases of the DD process, overseeing research progress and driving longitudinal engagement with the workforce.

Focus groups: Twenty participants took part in four focus groups (two per police force) during Phase 1 of the study (Discover). Purposeful random sampling was used to identify a diversity of roles and rank within each workforce. Police workers were excluded if their role and rank had already been represented by other focus group participants.

Interviews: Also, during Phase 1 (Discover), 10 interviews were conducted with police workers (Force A, n = 6; Force B, n = 4). Criterion-based and key informant sampling were used to recruit ‘inactive’ police employees who did not engage in physical activity. As a ‘hard-to-reach’ group, steering group members identified departments with low work-related physical activity for potential participants (e.g. sedentary custody and control room workers). Physically active police workers were excluded.

Intervention development: Steering group and control room workers (Force A, n = 67; Force B, n = 33) participated in intervention development phases.2–4 Police workers not working in the control room were excluded.

Procedure

The intervention development process was prefaced by a quantitative exploration of stress and wellbeing in the police.6 To support methodological rigor, member reflections, critical friends and reflexivity were applied throughout the intervention development process.23 Ethical clearance from the lead author’s institution was granted (references: 18-7-03R; 1873). The study was conducted over 7 years, from 2016 to 2023.

Phase 1 (Discover)

To understand physical activity behaviors, stress and wellbeing in the workforce, a literature review was conducted to discover potential theoretical determinants and whether any effective physical activity interventions already existed.12 Focus groups explored the relationship between physical activity and wellbeing across the workforce; key findings aligned to the COM-B model and informed the interviews. Interviews established the barriers and facilitators to the physical activity behavior of inactive police workers.

Phase 2 (Define)

In a workshop with the steering group, Phase 1 findings were consolidated to focus on sedentary behavior in the control room. Building on the COM-B concepts identified, the BCW guidance was followed to develop a context-specific intervention in Phases 3 and 4.

Phase 3 (Develop)

In Phase 3, researchers observed the control room context and collaborated (via workshops) with control room workers to learn about the feasibility and acceptability of intervention options. Workshops were repeated six times, across morning, day and night shifts in each police force to understand sedentary behavior and potential solutions in context (BCW Stage 1). Findings from the control room workshops were refined with the steering group to identify interventions options (BCW Stage 2). Using the Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness, Affordability, Side-effects and Equity criteria (APEASE)20 and further reviews of intervention evidence, an intervention option was selected.

Phase 4 (Deliver)

In Phase 4, feedback from senior management in the control rooms of both police forces was gathered in a workshop. The feedback informed the intervention content and implementation options (BCW Stage 3).

Materials for data collection

A focus group guide with personas was used to facilitate participants in considering the role of physical activity in wellbeing from the perspective of others, as well as their own (Supplement File 1). Each persona was of a police force worker with low physical activity behavior and prompted focus groups participants to discuss how physical activity might relate to the wellbeing of each persona. Personas were developed by co-creation with the steering group, and a pilot focus group was conducted with control room staff and other police workers to gain further feedback on how ‘real’ the personas were to their working context.

A semi-structured interview guide (Supplement File 2) was developed to understand a ‘typical’ working day for participants and prompt discussion on COM-B concepts in relation to physical activity at work.

Results

Phase 1 (Discover)

Full Phase 1 results are available in a literature review preprint24 and in Supplement File 3. A summary is provided here.

Literature review

Literature review findings24 coalesced around two themes: physical activity mechanisms and physical activity interventions. Reported mechanisms suggest that physical activity might: buffer the negative effects of work-related stress on health25; provide detachment and recovery from work26; offer a strategy for coping with stress27; and improve wellbeing through eudemonic processes (e.g. fulfilling psychological needs, feelings of mastery).28 Physical activity interventions in the police have been delivered primarily through exercise programs,29 team competitions,30,31 and/or sedentary behavior interventions through e-health software.32 Few interventions were theoretically informed, although motivational interviewing and the BCW have been used.30,33 Together, research suggests that social support,30,31 involvement in decision-making33 and embedding the activity into work practices29 might be important to the feasibility and efficacy of interventions.

Focus groups

Our reflexive thematic analysis34 identified two mechanisms to explain why physical activity was related to wellbeing in the police workforce: first, through the perception of stress (physical activity enabled reappraisal of stressful situations and/or was perceived as an effective way of coping), and second, through feelings of self-determination (physical activity fulfills relatedness, competency and autonomy). Focus group discussions reflected the COM-B concepts, as participants spoke about: the influence of others (e.g. supervisors) in permitting physical activity at work (social opportunity); the need to enjoy physical activity (motivation, psychological capability); and the work context (physical opportunity) as influential in physical activity behavior.

Interviews

Our reflexive thematic analysis found psychological capability, social opportunity, automatic motivation and reflective motivation were prominent barriers and enablers to physical activity behavior (see Table 1). Physical capability and physical opportunity were less prominent, possibly because the barriers for police employees using gyms at work were not solely related to facility availability (e.g. the perceived need for permission to be active in an autocratic and hierarchical work context). There were exceptions in that some work locations did lack facilities, highlighting a need for context-specific interventions.

Table 1.

Barriers and enablers to physical activity at work, aligned to COM-B concepts with initial codes from thematic analysis

| COM-B concept | Initial codes | Barrier | Enabler |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical capability | |||

| Ability | Lack skills or competence | Previous positive exercise experiences | |

| Psychological capability | |||

| Knowledge | Do not know how to include physical activity at work | Know benefits of physical activity | |

| Prioritizing | Need stronger mentality to prioritize wellbeing | ||

| Behavioral regulation | Not aware of sitting time | Self-monitoring sitting time Planning |

|

| Habit | Not in a physical activity habit or routine work patterns | ||

| Physical opportunity | |||

| Facilities | Facilities not consistent across force | Gyms and some sit–stand desks available | |

| Role demands | Role restrictions Short breaks and lack of time |

Could use lunch break for activities | |

| Social opportunity | |||

| Supervisor influences | Not common for supervisors to permit/allow time for physical activity Senior leaders not leading by example |

Supervisors who value physical activity | |

| Norms | Stigma if staff are away from their desk Being at your desk means you are working Sedentary norm |

||

| Support | Others can encourage physical activity | ||

| Automatic motivation | |||

| Interest (affect) | Exhausted after work stress | Enjoy physical activity | |

| Reflective motivation | |||

| Beliefs | Self-confidence to go to the gym | Organizational support of physical activity | |

| Identity | Responsibility of being in the police force cynicism | ||

Phase 2 (Define)

In a steering group workshop, Phase 1 results (Supplement File 3) were reviewed. The control room emerged as the context for the intervention development, and sedentary behavior was the target intervention behavior. Phase 1 participants had stated that the control room was a restrictive environment where access and opportunity to increase physical activity was problematic. Steering group members explained the restrictions meant that control room workers often felt unable to access existing police wellbeing initiatives that mostly coalesced around physical activity–type interventions (i.e. a context-specific intervention was needed). Leaning on the COM-B concepts identified in Phase 1, initial steering group intervention ideas included education, exercise prompts (psychological capability), social support, modeling (social opportunity), rewards (automatic motivation) and personal plans (reflective motivation). For the control room specifically, steering group members perceived that the intervention should focus on psychological capability and social opportunity, as it was important to reach the whole department (i.e. unlike personal plans), but not favor the control room over other departments in the workforce (i.e. unlike rewards). It was also suggested that existing interventions might be lower cost and help buy-in, if there was previous evidence that the intervention was effective. The workshop concluded by defining the next phases of the intervention development (see Fig. 1).

Phase 3 (Develop)

Control room workshops

It was identified that sedentary behavior in the control rooms was driven by work demand and social norms. The high levels of emergency calls and incidents meant that staff had little awareness of their own wellbeing needs (e.g. the need to move). The only reason not to be sat at a workstation was if a staff member was ‘doing a tea round’ for their team or going to the toilet. Supervisor permission was needed to do this. Apart from one 36-minute break during an 8–12-hour shift, staff thought there were no opportunities for movement within their role, although they wanted to move more. Control room workers were accustomed to monitoring computer screens, and so, a program prompting their movement was deemed a feasible intervention.

Steering group workshops

The APEASE criteria were used with the steering group to refine intervention options from the understanding gained in the control room workshops. Guided by the BCW, it was agreed that enablement, modeling, training and education intervention functions could all be influenced through service provision and regulation policy categories.17 Specifically, e-health software could deliver a service to prompt a change in the sedentary habits of control room workers, implemented by shaping social norms.

The researchers sourced six existing e-health software programs and met with representatives of two of the programs to discuss their features, functionality and scope for adaptation. The programs were demonstrated to the steering group in a workshop. The Exertime software35 was preferred as a bespoke version could be created for the control room context. The original Exertime software prompts users to stand and engage in a short bout of physical activity in the vicinity of their work desk. The duration of each exercise is determined by the user (typically 1–2 minutes), and users are prompted to complete an activity every 45 minutes. The prompt can be ignored, but only for 15 minutes, at which point Exertime takes over the computer screen to ‘force’ users into exercise and make it more difficult to continue with the existing sedentary habit (a passive prompt).

Phase 4 (Deliver)

Control-room senior management gave feedback on the e-health software. In Force B, supervisors were positive about the intervention and recognized their role in supporting staff (e.g. encouraging staff participation, providing different types of support to staff). They volunteered to be filmed demonstrating the software exercises to model behaviors and show their support. Further, supervisors suggested introducing the exercises to staff in training days so that they could practice the exercises, building their self-belief and confidence to participate. In Force A, leaders were generally positive but had some concerns that staff would use the software to take excessive breaks, negatively impacting performance. The workshop feedback was integrated into the intervention materials. As a result of the co-creation process, adaptations to Exertime for use in the control room setting included removing the forced prompt, extending the prompt to every hour and including video demonstrations of the supervisors completing the exercises in the control room environment.

The COM-B concepts, intervention functions, MoAs, behavior change techniques (BCTs) and mode of delivery are in Table 2. The key MoAs targeted in the sedentary behavior intervention are behavioral regulation, social influences and social norms (see the logic model in Supplement File 5). Additional MoAs are present in the intervention following the workshop feedback (e.g. staff practicing the exercises in training is linked to beliefs about capabilities; see Table 2). Further insight into the operationalization of the BCTs in the intervention is in Table 3.

Table 2.

Mapping COM-B concepts against intervention functions, MoA, BCTs and mode of delivery

| COM-B concept | Intervention function | MoA | BCT | Mode of delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological capability |

Education, enablement, modeling, training |

Behavioral regulation Memory, attention and decision processes Knowledge |

1.8 Behavioral contract 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior 8.3 Habit formation 1.9 Commitment 7.1 Prompts/cues 4.1 Instruction on how to perform behavior 5.1 Information about health consequences |

Face to face, individual Face to face, individual Face to face, individual Face to face, group Distance, individual Distance, individual Face to face, group Distance, individual Face to face, group Face to face, group |

| Social Opportunity |

Enablement, Modeling |

Social influences Norms/Subjective Norms |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

Face to face, individual Face to face, individual |

| Reflective motivation | Education, Modeling |

Goals Beliefs about capabilities Self-image |

1.5 Review behavior goal(s) 6.1 Demonstration of behavior 8.1 Behavioral practice/rehearsal 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability 13.1 Identification of self as role model |

Face to face, individual Face to face, group Face to face, group Face to face, individual Face to face, group |

Table 3.

BCTs mapped against their definition, intervention group, how it is operationalized and when it is delivered in the intervention

| Label | Definition in BCT Taxonomy | Group | Example of operationalization | When delivered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals and planning | ||||

| 1.1 Goal setting (behavior) | Set or agree a goal defined in terms of the behavior to be achieved | 3 | Supervisors will ask their staff to identify a specific goal in terms of the intervention, e.g. record five physical activities per shift | Intervention—Start |

| 1.2 Problem solving | Analyze, or prompt the person to analyze, factors influencing the behavior and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators | 3 | Supervisors will prompt their staff who are not engaging well with the physical activity software to generate strategies that could increase their engagement | Intervention—Mid |

| 1.4 Action planning | Prompt detailed planning of performance of the behavior (must include at least one of context, frequency, duration and intensity) | 3 | Supervisors will ask their staff how they plan to continue to perform physical activity behaviors at the end of the intervention | Intervention—End |

| 1.5 Review behavior goal(s) | Review behavior goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) or behavior change strategy in light of achievement. This may lead to re-setting the same goal, a small change in that goal or setting a new goal instead of (or in addition to) the first or no change | 3 | Supervisors will discuss progress with staff in relation to physical activity behaviors | Intervention—Mid, End |

| 1.8 Behavioral contract | Create a written specification of the behavior to be performed and witnessed by another | 3 | A contract is drawn up between the supervisor and their shift staff, during a team meeting so all witness the whole team committing to participate in the intervention | Intervention—Start |

| 1.9 Commitment | Ask the person to affirm or reaffirm statements indicating commitment to change the behavior | 3 | Supervisors will revisit the behavioral contract with their staff (individually and in meetings using the words ‘high priority’) to continue with physical activity behaviors | Intervention—Weekly |

| Feedback and monitoring | ||||

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior | Establish a method for the person to monitor and record their behavior | 2,3* | Staff are encouraged to view their feedback graphs in the physical activity software | Training session |

| Social support | ||||

| 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | Advise on, arrange or provide social support or non-contingent praise or reward for the behavior | 3 | Supervisors were given a list of supportive messages that could be portrayed to staff | Intervention—Weekly |

| Shaping knowledge | ||||

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Advise or agree how to perform the behavior | 1,2,3 | The researcher advises staff which exercises can be used to record naturally occurring activities, e.g. going to the loo | Training session |

| Natural consequences | ||||

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behavior | 1,2,3 | The researcher delivers content regarding the impact of sedentary behavior on general health and wellbeing | Training session |

| Comparison of behavior | ||||

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior | Provide an observable sample of the performance of the behavior directly in person or indirectly (e.g. via film, pictures, for the person to aspire to or imitate), includes ‘Modeling’ | 1,2,3 | Video demonstrations accompany each exercise within the software | Intervention |

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval | Provide information about what other people think about the behavior. The information clarifies whether others will like, approve or disapprove of what the person is doing or will do | 1,2,3* | The researcher highlighted that supervisors are supportive of the intervention and have participated in the software video demonstrations | Training session |

| Associations | ||||

| 7.1 Prompts/cues | Introduce or define environmental or social stimulus with the purpose of prompting or cueing the behavior. The prompt or cue would normally occur at the time or place of performance. | 2,3 | The Exertime software prompts staff to stand and engage in a short-burst exercise every hour | Intervention |

| Repetition and substitution | ||||

| 8.1 Behavioral practice/rehearsal | Prompt practice or rehearsal of the performance of the behavior one or more times in a context or at a time when the performance might not be necessary, in order to increase habit or skill | 1,2,3 | The researcher leads staff in completing four of the exercises in the software | Training session |

| 8.3 Habit formation | Prompt rehearsal and repetition of the behavior in the same context repeatedly so that the context elicits the behavior | 2,3 | The software prompts repetition of the same physical activities within the vicinity of work desks | Intervention |

| Identity | ||||

| 13.1 Identification of self as role model | Inform that one’s own behavior may be an example to others | 1,2,3* | The researcher informs supervisors that they are role models to their staff and their behaviors | Supervisor training session |

| Self-belief | ||||

| 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | Tell the person that they can successfully perform the behavior, arguing against self-doubts and asserting that they can and will succeed | 3 | Supervisors tell their staff that they can successfully decrease their sedentary time, despite the demands of their roles | Intervention—mid |

Groups: 1 = Control, 2 = Intervention, 3 = Social * = Can be reinforced in the social group

Discussion

Main finding of this study

This research aimed to develop a sedentary behavior intervention with police control room workers. We found that the DD and BCW can be combined to co-create theoretically informed and contextually relevant interventions across multiple stakeholders in longitudinal multiphase research. Phase 1 (Discover) found that psychological capability, social opportunity and motivation were potential enablers for increasing the physical activity behavior of inactive police workers. In Phase 2 (Define), the control room context was identified as a high-stress police force area in need of specific wellbeing support. Sedentary behavior was identified as the target intervention behavior. The COM-B concepts identified in Phase 1 and 2 informed the BCW approach used in Phase 3 (Develop) and 4 (Deliver) to systematically develop the intervention. Workshops conducted in the police control rooms found that sedentary behavior was driven by demand (i.e. psychological capability) and social norms (i.e. social opportunity). Over a series of workshops in an iterative, rigorous approach, the sedentary behavior intervention was developed to target behavioral regulation, social influence and social norm mechanisms and prompt physical activity in the control rooms.

What is already known on this topic

Complex health interventions need to describe the intervention process clearly, understand the context and have a theoretical basis.11 However, this is rarely achieved in research.14 Co-creation approaches can bring theory and context together in interventions, yet the underpinning processes are unclear.5 Within the control room context of this study, research had identified the sedentary, stressful environment as risk factors for worker health,1,8 but had yet to explore how interventions could be developed to support control room worker health and wellbeing.

What this study adds

Our findings provide a novel method by which researchers can include theory, workforce engagement and a strong appreciation of context in their interventions. Our method combined the DD and BCW frameworks in a co-creation approach driven by iterative divergent and convergent processes; something new within the extant literature. These processes enabled the BCW to be introduced into the research procedure as it was identified in Phase 1 findings. The BCW was needed within the DD framework because it provided a systematic process to develop a theory-informed and context-specific intervention. The BCW steps also encouraged consideration of how the intervention was implemented and translated into action (i.e. BCTs and mode of delivery). These steps were central to including activities in the intervention that targeted social influence mechanisms (see Supplement File 5). To make the theoretical mechanisms in the intervention clear (see Table 2 and Supplement File 5), we used an additional step in the BCW by adopting the MoAs. This novel step is needed to advance health behavior change theory.22 Without our identification of contextual implementation options and proposed mechanisms, an ‘off-the-shelf’ existing software option would have been adopted by steering group members, something less likely to change behavior and translate into action.36

Our research has high ecological validity, was conducted in a novel context and used robust methods over multiple phases in a longitudinally theoretically driven manner. Individually, these are clear strengths11 and collectively address gaps in knowledge regarding co-creation research.37,38 The findings make original contributions to knowledge about the drivers of behavior in an under-researched context, and the co-creation processes can be used by future researchers.

Limitations of this study

There are two main limitations to the research. The co-creation processes were not formally evaluated; doing so could further determine the impact and potential benefits of participatory research.4 Second, as the research was iterative, findings relate to physical activity, exercise, physical inactivity and sedentary behavior, and there is a need to understand how these different terms relate to wellbeing in the police.

Research should now pilot the intervention and test the mechanisms identified; this could be done through the protocol detailed in Supplement File 4. Future research should explore physical activity interventions with other departments in the police workforce (e.g. with firearms officers39) to develop an evidence base that could inform police wellbeing policy (e.g. the Police Covenant2). Theoretically informed and well-reported interventions are needed to achieve this,3 as demonstrated in the method in this research.

Conclusion

This research iteratively and robustly developed a sedentary behavior intervention to support wellbeing in police control rooms, a novel, under-researched area of policing. We demonstrated that sedentary behavior in such contexts is driven by work demand and social norms. Co-creation, guided by the DD and BCW, developed an intervention targeted toward behavioral regulation, social influence and social norms mechanisms. The intervention also targeted support for and involvement of staff in decision-making and embedding physical activity into work practices. The process of developing an intervention using the DD and BCW appears efficacious and can be applied to support various health and wellbeing behaviors to deliver context-relevant interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Scott Pedersen and Anjia Ye (both University of Tasmania, Active Work Laboratory) for their contributions during the third and fourth phases of the research.

Helen Oliver, Lecturer

Owen Thomas, Professor

Rich Neil, Professor

Robert J. Copeland, Professor

Tjerk Moll, Senior Lecturer

Kathryn Chadd, Head of Resourcing and Reward

Matthew J Jukes, Assistant Commissioner

Alisa Quartermaine, Head of Human Resources

Contributor Information

Helen Oliver, Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, CF23 6XD, Wales, UK.

Owen Thomas, Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, CF23 6XD, Wales, UK.

Rich Neil, Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, CF23 6XD, Wales, UK.

Robert J Copeland, Sheffield Hallam University, Advanced Wellbeing Research Centre, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, S9 3TY, UK.

Tjerk Moll, Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, CF23 6XD, Wales, UK.

Kathryn Chadd, South Wales Police, Bridgend, CF31 3SU, UK.

Matthew J Jukes, The Metropolitan Police Service, London, SW1A 2JL, UK.

Alisa Quartermaine, Gwent Police, Cwmbran, NP44 3FW, UK.

Funding

This research output was supported by Gwent and South Wales police forces and Cardiff Metropolitan University.

Authors’ contributions

HO, OT, KC, MJ and AQ conceived the study and acquired the data. HO, OT, RN, RJC and TM analyzed the data. KC, MJ and AQ contributed to the interpretation of data. HO drafted the article, OT, RJC, RN and TM contributed to revisions of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the article to be submitted.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for privacy reasons. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Smith EC, Holmes L, Burkle FM. Exploring the physical and mental health challenges associated with emergency service call-taking and dispatching: a review of the literature. Prehosp Disaster Med 2019;34(6):619–24. 10.1017/S1049023X19004990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Home Office. Police Covenant. 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/police-covenant.

- 3. Phythian R, Birdsall N, Kirby S. et al. Developments in UK police wellbeing: a review of blue light wellbeing frameworks. Police J 2022;95(1):24–49. 10.1177/0032258X211073003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J. et al. Co-creation, co-design and co-production for public health: a perspective on definitions and distinctions. Public Heal Res Pract 2022;32:1–7. 10.17061/phrp3222211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Messiha K, Chinapaw MJM, Ket HCFF. et al. Systematic review of contemporary theories used for co-creation, co-design and co-production in public health. J Public Heal (United Kingdom) 2023;45(3):723–37. 10.1093/pubmed/fdad046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oliver H, Thomas O, Neil R. et al. Stress and psychological wellbeing in British police force officers and staff. Curr Psychol 2022;42:29291–304. 10.1007/s12144-022-03903-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Routledge handbook of youth sport 2016;1–582 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galbraith N, Boyda D, McFeeters D. et al. Patterns of occupational stress in police contact and dispatch personnel: implications for physical and psychological health. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2021;94(2):231–41. 10.1007/s00420-020-01562-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Acquadro Maran D, Zedda M, Varetto A. Physical practice and wellness courses reduce distress and improve wellbeing in police officers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(4):578. 10.3390/ijerph15040578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. SJH Biddle. Do we need motivation to sit less? Thoughts on a psychology of sedentary lifestyles. In: Dicke T, Guay F, Marsh HW. et al. (eds). Self: a multidisciplinary concept. Charlotte, NC, United States: Independent Age Publishing, 2021, 103–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA. et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2021;25(57):1–132. 10.3310/hta25570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E. et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019;9(8):e029954–9. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Craig P, Di RE, Frohlich KL. et al. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers, users and funders of research. Southampton: NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, 2018. 10.3310/CIHR-NIHR-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duncan E, O’Cathain A, Rousseau N. et al. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open 2020;10(4):e033516–2. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Design Council . Framework for innovation, 2019 Available from:, https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/framework-for-innovation/.

- 16. Guldbrandsen M. Design innovation: embedding design process in a charity organization: evolving the Double Diamond at Macmillan cancer support. In: Tsekleves E, Cooper R (eds). Design for health. London: Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behavior change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing, 2014. www.behaviourchangewheel.com. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Creaser AV, Bingham DD, Bennett HAJ. et al. The development of a family-based wearable intervention using behaviour change and co-design approaches: move and connect. Public Health 2023;217:54–64. 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daly-Smith A, Quarmby T, Archbold VSJ. et al. Using a multi-stakeholder experience-based design process to co-develop the creating active schools framework. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020;17(1):1–13. 10.1186/s12966-020-0917-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carey RN, Connell LE, Johnston M. et al. Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Ann Behav Med 2018;53(8):693–707. 10.1093/abm/kay078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Byrne M. Gaps and priorities in advancing methods for health behaviour change research. Health Psychol Rev 2020;14(1):165–75. 10.1080/17437199.2019.1707106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith B, McGannon KR. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2018;11(1):101–21. 10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oliver H, Thomas O, Neil R. et al. Physical activity, stress and wellbeing in the police: a literature review, 2023. 10.31219/osf.io/usxga. [DOI]

- 25. Gerber M, Pühse U. Review article: do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand J Public Health 2009;37(8):801–19. 10.1177/1403494809350522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sonnentag S. The recovery paradox: portraying the complex interplay between job stressors, lack of recovery, and poor well-being. Res Organ Behav 2018;38:169–85. 10.1016/j.riob.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anshel M. A conceptual model and Implications for coping with stressful events. Crim Justice Behav 2000;27(3):375–400. 10.1177/0093854800027003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimiecik J. The eudaimonics of health: exploring the promise of positive well-being and healthier living. In: Vittersø J (ed). Handbook of eudaimonic well-being. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016, 356–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossomanno CI, Herrick JE, Kirk SM. et al. A 6-month supervised employer-based minimal exercise program for police officers improves fitness. J Strength Cond Res 2012;26(9):2338–44. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f2b64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brierley ML, Smith LR, Chater AM. et al. A-REST (activity to reduce excessive sitting time): a feasibility trial to reduce prolonged sitting in police staff. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(15):9186. 10.3390/ijerph19159186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oliver H, Thomas O, Copeland RJ. et al. Proof of concept and feasibility of the app-based ‘#SWPMoveMore challenge’: impacts on physical activity and well-being in a police population. Police J 2022;95(1):170–89. 10.1177/0032258X211024690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mainsbridge CP, Cooley D, Dawkins S. et al. Taking a stand for office-based workers’ mental health: the return of the microbreak. Front Public Heal 2020;8:547969. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anshel MH, Kang M. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on changes in fitness, blood lipids, and exercise adherence of police officers: an outcome-based action study. J Correct Heal Care 2008;14(1):48–62. 10.1177/1078345807308846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London, Sage 2022; [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pedersen SJ, Cooley PD, Mainsbridge C. An e-health intervention designed to increase workday energy expenditure by reducing prolonged occupational sitting habits. Work 2014;49(2):289–95. 10.3233/WOR-131644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Biron C, Karanika-Murray M. Process evaluation for organizational stress and well-being interventions: implications for theory, method, and practice. Int J Stress Manag 2014;21(1):85. 10.1037/a0033227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Heal Res Policy Syst 2020;18(1):1–13. 10.1186/s12961-020-0528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith B, Williams O, Bone L. et al. Co-production: a resource to guide co-producing research in the sport, exercise, and health sciences. Qual Res Sport Exerc Heal 2022;15(2):159–87. 10.1080/2159676x.2022.2052946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bradley E, Fayaz S, Farish C. et al. Evaluation of physical health, mental wellbeing, and injury in a UK police firearms unit. Police Pract Res 2023;24(2):232–44. 10.1080/15614263.2022.2080066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for privacy reasons. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.