Abstract

Introduction:

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness are two self-focused, positive coping approaches that may reduce risk of problem drinking and/or aid in treatment/recovery from alcohol use disorder. The present systematic review aimed to evaluate support for the unique and complementary roles of self-compassion and self-forgiveness in alcohol outcomes.

Methods:

A systematic literature search yielded 18 studies examining self-compassion, 18 studies examining self-forgiveness, and 1 study examining both constructs in alcohol outcomes.

Results:

Findings suggest greater self-compassion and self-forgiveness relate to lower likelihood of problem drinking. Self-forgiveness was considerably more researched in treatment/recovery outcomes than self-compassion; self-forgiveness-based interventions appear able to improve drinking-adjacent outcomes, and self-forgiveness may increase across various alcohol treatments. Finally, research suggests that associations of self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes could be driven by numerous factors, including coping-motivated drinking, depression, psychache, social support perceptions, mental health status, and/or psychiatric distress.

Conclusions:

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness both appear protective against harmful alcohol outcomes. Nevertheless, many questions remain about the role of self-forgiveness and, particularly, self-compassion in alcohol treatment and recovery outcomes. Future research should examine whether targeted interventions and/or adjunctive therapeutic supports designed to increase self-compassion or self-forgiveness can reduce alcohol use disorder symptoms to facilitate alcohol treatment and recovery success.

Keywords: self-compassion, self-forgiveness, alcohol use, drinking, alcohol use disorder

Introduction

Excessive or problematic alcohol use can lead to considerable economic consequences, health problems, alcohol use disorder (AUD), and mortality (World Health Organization, n.d., Rehm & Imtiaz, 2016; Roerecke & Rehm, 2013). Research is needed to characterize factors that contribute to as well as protect against the development of such alcohol use so as to inform both prevention and intervention efforts (Sher, Grekin, & Williams, 2005; Bujarski & Ray, 2016; Palmer et al., 2019; Sliedrecht et al., 2019).

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness are protective, self-directed processes that may be leveraged in prevention and/or intervention of problematic alcohol use. Both self-compassion and self-forgiveness represent forms of self-acceptance that can involve recognition and acknowledgement of one’s perceived inadequacies, faults, and/or wrongdoings (see Hall and Fincham, 2005; Neff, 2003a, 2003b; Webb et al., 2011). Such processes also both involve subsequent commitments to self-respecting action, either the broad motivation to relieve one’s own suffering (i.e., self-compassion; Neff, 2003a, 2003b) or the decision to release self-directed negativity related to prior transgressions (i.e., self-forgiveness; Hall & Fincham, 2005; Webb et al., 2011). Thus, both self-compassion and self-forgiveness represent forms of emotion regulation, which have been shown to protect against a variety of physical and mental health outcomes (Davis et al., 2015; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Self-compassion and self-forgiveness may similarly protect against problem drinking specifically, perhaps by facilitating more adaptive coping with negative emotions that otherwise would promote coping-motivated drinking (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Dvorak et al., 2014; Greely & Oei, 1999; Khantzian, 1997). Self-compassion and self-forgiveness also may promote overall well-being (Neff, 2003a, Zessin, Dickhäuser, & Garbade, 2015; McConnell, 2015) as well as decrease negative affect states (e.g., anxiety, depression; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Davis et al., 2015; Barnard & Curry, 2011) and shame (McGaffin, Lyons, & Deane 2013; Lin et al, 2004; Chen, 2019), all of which have been implicated in problem drinking risk (Sleidrecht et al., 2019; Wiechelt, 2007; Yang et al., 2018; Luoma, Chwyl, & Kaplan, 2019; Dvorak et al., 2014; Corbin, Farmer, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2013).

Both self-compassion and self-forgiveness have garnered increased attention in psychological research in recent years (Strauss et al., 2016; Chen, 2019; Davis et al., 2015; Webb, Toussaint, & Hirsch, 2011), yet much still is unknown about how these constructs together relate to alcohol outcomes. For example, self-compassion may be a prerequisite for self-forgiveness, whereby individuals must first adopt a self-compassionate mindset to reflect upon their prior actions without overly harsh self-criticism before committing to self-reconciliation. The relationship between self-compassion and self-forgiveness has been characterized in many ways in the extant literature, reflecting their conceptual overlap. For example, self-compassion has been proposed by some to be a transitional stage toward self-forgiveness (Enright, 1996). Others have asserted that self-forgiveness is a subcomponent of self-compassion (Terry and Leary, 2011). Yet, though there is overlap, self-compassion and self-forgiveness also are inherently distinct. For example, some individuals may acknowledge painful self-judgements without overly identifying with them (i.e., self-compassion) yet ultimately not decide to reconcile these self-criticisms by releasing negativity toward themselves (i.e., self-forgiveness). Further, self-compassion could hinder reconciliation with others to impede genuine self-forgiveness (Woodyatt, Wenzel, & Ferber, 2017), yet genuine self-forgiveness also may require a process of restoration that involves the development of self-compassion (Woodyatt, Worthington, Wenzel, & Griffin, 2017). Finally, there may be a dynamic interplay of self-compassion with self-forgiveness (Maynard, van Kessel, & Feather, 2023), and the temporal ordering of the application of these skills may be important for desired outcomes, such as reconciliation (Woodyatt, Wenzel, et al, 2017). Such conceptual ambiguity between self-compassion and self-forgiveness results in challenges understanding their respective roles in alcohol risk and treatment/recovery. It remains largely unknown how both together relate conceptually to alcohol use patterns, whether one (or both) drive problem drinking risk, and whether one (or both) might be an important target in psychosocial interventions for AUD.

The present review aimed to synthesize the empirical literature on both self-compassion and self-forgiveness in risk for and treatment/recovery from problem alcohol involvement to explore these questions and identify important future directions for research in this field. We begin with an introduction to both self-compassion and self-forgiveness, along with a summary of their theorized relation to alcohol outcomes.

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion fosters a kind, understanding attitude towards oneself through the non-judgmental recognition of one’s perceived inadequacies as viewed through the common human experience (Neff, 2003a, 2003b). Self-compassion derives from the broader construct of compassion, which is born mainly from Buddhist perspectives (Strauss et al., 2016) and comprises both the empathic emotional reaction to suffering and a motivation to reduce suffering (Graser & Stangier, 2018; Strauss et al., 2016; Gilbert, 2010). Self-directed compassion, or self-compassion, turns these empathic motivations inward by being open and connected to one’s own suffering with a desire to alleviate this suffering through nonjudgmental understanding (Neff, 2003a; Strauss et al., 2016). Neff (2003a) conceptualizes self-compassion as composed of three interrelated states, each contrasted with less adaptive states: self-kindness (versus self-judgement), common humanity (versus isolation), and mindfulness (versus over-identification). Self-kindness is described as a gentle, understanding attitude towards the self, as opposed to self-criticism and harsh judgement of one’s experiences. Common humanity represents the awareness that one shares common experiences with humanity, as opposed to being isolated and cut off from others. Mindfulness reflects a balanced awareness of one’s internal thoughts and feelings, both positive and negative, without casting judgment on or being overly identified with them.

Self-compassion may reduce problem drinking by facilitating effective management of negative affect. Self-medication (Khantzian, 1996) and tension reduction (Greeley & Oei, 1999) models strongly implicate emotion dysregulation in the origins of problem drinking. That is, individuals experiencing difficulty regulating emotions and stress responses may tend toward avoidant or maladaptive coping strategies, such as alcohol consumption (Dvorak, 2014; Corbin, 2013; Britton, 2004; see Ewert, Vater, and Schröder-Abé, 2021 for a meta-analysis). Self-compassion represents an adaptive, emotional-approach coping strategy (Neff 2003a, 2003b) characterized by effortful awareness of and willingness to explore one’s emotional states (Stanton et al., 1994). Thus, self-compassion could reduce or mitigate strong negative emotions that may otherwise lead to drinking (Scoglio et al., 2018; Wisener & Khoury, 2021). Further, self-compassion may buffer against shame related to problem drinking (Neff, 2011; Zessin et al., 2015) to improve alcohol self-control (Song, Jo, & Won, 2018; Sliedrecht et al., 2019).

Self-compassion may also protect against problem drinking by increasing positive emotional states (Held, et al., 2018). Self-compassion invokes a loving, kind attitude towards oneself coupled with a recognition of humanity’s shared experiences, burdens, and interpersonal connection. Such adaptive perspectives may promote positive affect states that minimize likelihood of coping-motivated problem drinking. Compassion-focused interventions aim to leverage and increase compassion and/or self-compassion as a form of positive psychology intervention (Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Neff & Germer, 2013). Although applied most widely to treat depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (Kirby, Tellegen, & Steindl, 2017), we are aware of at least one study showing compassion-focused therapy may increase positive affective states (e.g., meaning in life, self-compassion) among individuals with substance use disorder (Held et al., 2018). Thus, compassion-based interventions may hold promise in reducing AUD symptoms in part by increasing positive affect states to decrease subsequent problem drinking.

In summary, self-compassion may represent a positive coping strategy reducing negative affect states and/or increasing positive affect states to thereby protect against problematic drinking or facilitate reduction in symptoms among individuals with AUD. Nevertheless, research on compassion-focused interventions for alcohol or substance use disorder has been considerably more limited than for additional mental health conditions. Further, there have been no attempts, to our knowledge, to review the recently emerging and quickly growing literature on self-compassion’s role in the development and treatment of deleterious alcohol outcomes. Efforts are needed to systematically summarize current research, highlight gaps in the literature, and suggest future directions for both prevention and intervention.

Self-Forgiveness

Self-forgiveness is considered a distinct dimension of forgiveness (Webb et al., 2017). Forgiveness emphasizes interpersonal forgiveness (i.e., forgiving someone else) while self-forgiveness emphasizes intrapersonal forgiveness (i.e., forgiving oneself). Self-forgiveness can be conceptualized as an acceptance of responsibility for prior perceived wrongdoing(s) with the intentional decision to reconcile such experiences by releasing self-criticism and fostering a balanced acceptance of oneself (Hall & Fincham, 2005; Webb et al., 2011). Self-forgiveness thus encompasses the release of negative feelings toward the self (Enright, 1996, Enright, Freedman, & Rique, 1998, Hall, & Fincham, 2008). Self-forgiveness’ importance in psychological research grew following construction of a theoretical model (Hall & Fincham, 2005) that posits self-forgiveness as driven by cognitive (i.e., attributions of behavior), affective (e.g., guilt or shame), and behavioral (i.e., conciliatory behavior) processes, which may represent modifiable targets for interventions aimed at enhancing self-forgiveness.

Self-forgiveness may protect against problem drinking by minimizing the emergence of/coping with negative emotions that could lead to coping-motivated drinking. Specifically, self-forgiveness may reduce the impact of negative self-focused emotions, such as self-blame for past negative events (e.g., trauma; Worthington & Langberg, 2012) or damaging interpersonal consequences of one’s prior drinking (Hall & Fincham, 2005; Webb, Toussaint, and Hirsch, 2017). Shame and guilt have received particular attention in the context of self-forgiveness and alcohol use relations (Webb, Toussaint, & Hirsch, 2011; Worthington et al., 2007). Shame represents a self-destructive, self-focused emotion associated with a failure to forgive oneself (Hall & Fincham, 2005), while guilt represents an other-focused negative emotional state conducive to empathic concern and conciliatory behavior towards others (Hall & Fincham, 2005). Problem drinking can increase negative affect, guilt, shame, anger, and resentment (McGaffin, Lyons, & Deane, 2013; Lin et al., 2004; Toussaint, Worthington, and Williams, 2015) that can in turn serve to maintain harmful drinking patterns (Wiechelt, 2007; McGaffin, Lyons, & Deane, 2013). Self-forgiveness can ameliorate these emotions (Hall & Fincham, 2005), thereby buffering against later problematic drinking (Toussaint, Webb, and Hirsch, 2017).

Self-forgiveness-based interventions have been developed to help individuals process negative, self-focused emotions in an effort to reduce negative alcohol outcomes (McConnell, 2015; Scherer et al., 2011). Self-forgiveness also has been viewed as an integral aspect of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (Lyons et al., 2011; Webb & Toussaint, 2017). In this context, self-forgiveness might help individuals adaptively reconcile self-focused condemnation linked to prior alcohol consequences (e.g., failure in obligations to significant others, dangerous or reckless behavior), thus reducing cyclical patterns of shame-based drinking that may maintain problem drinking.

Several models of self-forgiveness, generally adapted from more broad models of forgiveness, have been applied to substance using populations (e.g., McGaffin, Lyons, & Deane, 2013; Scherer et al., 2011; Verona & Branthoover, 2022; Touissant et al., 2015; Webb, 2021). Recent reviews of theory and modeling literature (see Touissant et al., 2015; Webb, 2021; Woodyatt, Worthington et al., 2017) have found evidence of the importance of self-forgiveness in problematic substance use, through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Other work has focused on how forgiveness is consistent with or reflected in empirically-validated treatments for substance use (e.g., Webb & Trautman, 2010). However, empirical tests of models with self-forgiveness specifically (separate from forgiveness in general or grouped with other kinds of forgiveness, such as other forgiveness) and alcohol outcomes have been more limited (but see Webb, 2021 and Woodyatt, Worthington et al, 2017 for thorough and recent reviews of forgiveness, including self-forgiveness, and research on addiction and health including problematic alcohol outcomes). Research on self-forgiveness in alcohol outcomes has increased considerably over the past two decades, with the notable emergence of self-forgiveness-based interventions for problem drinking (e.g., Scherer et al., 2011). Efforts to review self-forgiveness’ role in alcohol risk and recovery, as well as potential mechanisms of and/or individual differences in such relations, together with self-compassion could inform future clinical efforts.

Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness are conceptually and empirically related constructs. The ways in which the two may contribute uniquely or together to alcohol and other harmful outcomes may have important clinical implications. For those in recovery, a balance between self-forgiveness and self-compassion has been proposed to be a crucial part of the recovery process (see Webb & Jeter, 2015 in Toussaint et al., 2015). Some theoretical frameworks propose a unified model that includes both self-compassion and self-forgiveness (McConnell, 2015; Terry & Leary, 2011), whereby self-forgiveness may be conceptualized as a component of self-compassion (Terry & Leary, 2011) or a transitional stage toward self-forgiveness (Enright, 1996). If so, clinical efforts may only need to target self-compassion (or self-forgiveness) to maximize treatment outcomes. Other work suggests that both constructs might be necessary, but that the timing and delivery of skill development may be important for specific outcomes (Maynard et al., 2021; Woodyatt, Wenzel, et al., 2017). Despite these obvious intervention implications, to date, there have been no attempts to synthesize the literature on how self-compassion and self-forgiveness may operate in concert to influence alcohol outcomes.

Importance of this Review

The research base on self-compassion and self-forgiveness in alcohol outcomes is growing, providing a unique opportunity to assess the role of these constructs in alcohol risk and treatment/recovery across the literature. Both self-compassion and self-forgiveness may play important roles in risk, treatment, and recovery from problem alcohol involvement. However, to our knowledge, there has not been a systematic review of self-compassion and self-forgiveness both uniquely and in the context of one another, in relation to alcohol outcomes. This was the objective of the present review. We sought to address several questions. First, we aimed to characterize the strength of the existing literature in support of self-compassion/self-forgiveness reducing risk for problem drinking and improving AUD treatment/recovery outcomes. Second, we aimed to summarize knowledge on the mechanisms through which self-compassion/self-forgiveness might affect alcohol outcomes and any individual differences in such associations. Finally, we also highlighted continued questions remaining in the literature with recommendations for next steps for future research.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify research on self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness in alcohol risk and treatment/recovery. Eligible studies were peer-reviewed publications written in English that examined associations of self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness with alcohol use/problems or within a sample in treatment for AUD. For inclusion, self-compassion and self-forgiveness were operationalized based on how they were described in the relevant literature such that any study reporting to measure “self-compassion” or “self-forgiveness” was retained. The full texts of the articles were reviewed to ensure that included papers met study criteria. Though use of published measures of self-compassion and self-forgiveness was not an inclusion criterion, it was the case that all papers used measures that had been previously published. Studies that measured alcohol use/problems only as part of a broader substance use measure, or studies only measuring self-forgiveness subsumed as part of a broader forgiveness construct were excluded. Database searches were conducted by the first author in PsycINFO, PubMed, and Medline through May 22, 2023 using the following keywords: (“self compassion” OR “self forgiveness” OR forgiveness) AND (alcohol* OR drink*); the present study was not preregistered. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2; Sterne et al., 2019) for experimental studies and the risk of bias assessment tool for nonrandomized studies (RoBANS; Kim et al., 2013).

Results

Literature Search

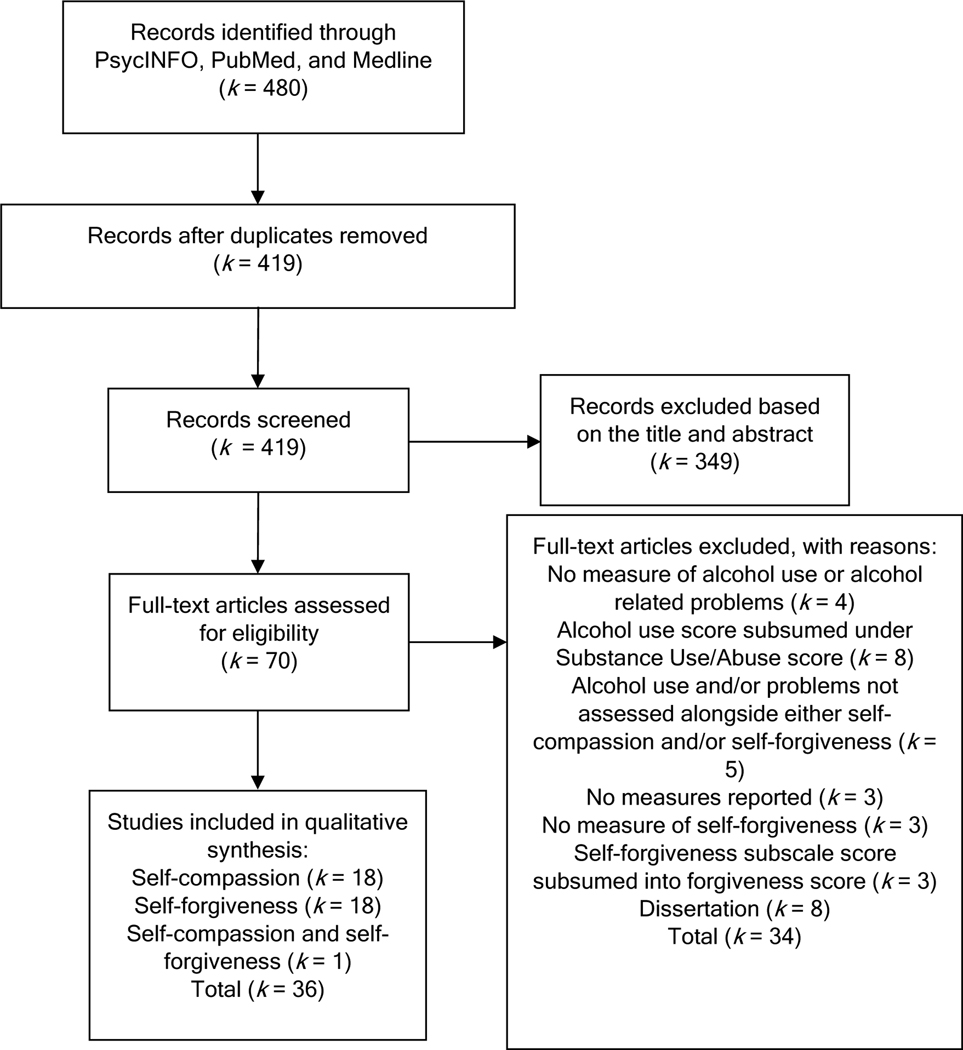

There were 419 returns for review after excluding duplicate records (Figure 1). Title/abstract reviews by the first author excluded 349 returns that were not relevant to the search criteria and/or not written in English. Full text reviews were conducted by the first and third author on the remaining returns, and an additional 34 articles were excluded for the following reasons: no measure of alcohol use and/or problems (n = 4); no measure of self-forgiveness (n = 3); alcohol outcome subsumed into substance outcome measure (n = 8); self-forgiveness subsumed into an overall forgiveness scale (n = 3); did not look at alcohol use and/or problems and either self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness together (n = 5); no measures reported (n = 3). The remaining returns comprised 18 examinations of self-compassion and 18 of self-forgiveness, and one study on both self-compassion and self-forgiveness (Ellingwood et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic search process.

Study Quality

Study quality assessments for nonrandomized studies revealed common potential biases arising from challenges inherent in measuring self-compassion, self-forgiveness, and/or alcohol outcomes. That is, these constructs overwhelmingly were assessed through self-report such that social desirability biases may artificially inflate true associations. Possible biases arising from incomplete outcome data also were often unclear (i.e., missingness not reported; k = 21) or potentially high risk (k = 7). Patterns of missing data may bias findings against the importance of self-forgiveness (or self-compassion) in post-treatment alcohol outcomes. Participant selection, in contrast, presented fewer sources of potential bias given that recruitment generally did not depend on self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness, and studies also tended to control for demographic (e.g., sex/gender, age, education, employment) and other (e.g., religiousness) constructs to account for relevant participant characteristics (k = 18). Finally, research characteristically was not preregistered, resulting in unclear selective outcome reporting.

Study quality assessment for the single randomized study suggested several sources of potential bias similar to those in nonrandomized studies. Specifically, missingness attributed to treatment engagement and retention may have depended upon self-forgiveness and/or alcohol consumption thereby strengthening (or weakening) self-forgiveness-based alcohol outcomes.

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Studies

Self-Compassion

Research that was identified on self-compassion focused primarily on alcohol risk (k = 15) compared to treatment/recovery (k = 2; Table 1). Research was derived from various community samples (with some samples repeated in more than one paper), including undergraduates (k = 5), First Nation or child protective services involved adolescents (k = 4), military veterans (k = 3), law enforcement officers (k = 1), and women sexual assault survivors (k = 1), as well as individuals in outpatient substance use disorder treatment (k = 2) or a partial hospitalization program for PTSD (k = 1). Samples spanned adolescence to later adulthood (Mage = 14 – 44 years). Self-compassion was assessed exclusively through the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003b) or the Self-Compassion Scale Short Form (Raes et al., 2011), and alcohol outcomes encompassed a variety of indices including alcohol quantity, frequency, and problems/consequences. Included research was primarily cross-sectional (k = 13), with four longitudinal investigations spanning between two months to a year (Brooks et al., 2012; Garner et al., 2020; Kaplan et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Self-Compassion and Alcohol Outcomes

| Risk for Alcohol Use and Problems | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Reference | Sample | Measures | Study Design | Study Aims | Key Findings | ||

| n/description | Demographics | Alcohol | SC | ||||

| Braun et al., (2023) | 288 women sexual assault survivors | 100% female 82% white |

AUDIT | SCS-SF | cross-sectional | Examine the link between internalized alcohol stigma and depression, test whether self-compassion buffered this in a sample with a history of sexual assault and unhealthy drinking | • Self-compassion buffered the relationship between internalized alcohol stigma and depression and accounted for additional variance in the model above other covariates |

| Ellingwood et al., (2019) | 84 undergraduates | 64% female 47% white |

QFI | SCS | cross-sectional | Characterize relations between self-compassion, forgiveness, and alcohol use | • Higher self-compassion found among drinkers, compared to non-drinkers |

| Forkus et al., (2019) | 203 military veterans | 77% male 70% white |

AUDIT | SCS | cross-sectional | Examine moderating role of self-compassion between morally injurious experiences and mental and behavioral health outcomes (including alcohol) | • Lower self-compassion and higher morally injurious experiences were associated with increased alcohol misuse |

| Forkus et al., (2020) | 203 military veterans | 78% male 72% white |

AUDIT | SCS | cross-sectional | Investigate whether self-compassion and fear of self-compassion, separately, impact relations of PTSD symptoms with alcohol misuse | • Both self-compassion and fear of self-compassion had indirect effects on associations of PTSD symptoms with alcohol misuse • Fear of self-compassion explained PTSD and alcohol relations, even when controlling for self-compassion |

| Kaplan et al., (2020) | 28 law enforcement officers | 90% male 84–88% white |

PROMIS® AU-SF | SCS-SF | longitudinal | Investigate the relative impact of improvements in mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological flexibility in predicting increased burnout and alcohol use | • Only changes in mindfulness significantly predicted changes in problematic alcohol use relative to changes in self-compassion and psychological flexibility when modeled together • Only changes in self-compassion significantly predicted changes in burnout relative to changes in mindfulness and psychological flexibility when modeled together |

| Meyer et al., (2019) | 128 military veterans | 84% male 59% white |

RAPI | SCS | longitudinal | Assess the contribution of self-compassion, mindfulness, and psychological flexibility to changes in PTSD symptom severity, after accounting for combat exposure, alcohol use, and traumatic brain injury | • Self-compassion and alcohol use were not significantly correlated • Self-compassion emerged as a significant individual predictor in recovery from PTSD symptoms |

| Miron et al., (2013) | 667 undergraduates | 100% female 70% white |

YAAPST | SCS | cross-sectional | Examine associations among self-compassion, childhood abuse, adolescent sexual assault, and alcohol problems | • Childhood emotional abuse indirectly related to alcohol problems via lower levels of self-compassion |

| Schick et al., (2021) | 106 First Nation adolescents | 50% female | ADQ RAPI |

SCS-SF | cross-sectional | Examine self-compassion as a moderator of the links between racial discrimination and alcohol use and alcohol-related problems | • Associations between racial discrimination and both alcohol use and problems were moderated by self-compassion (significant for low self-compassion but not high self-compassion) |

| Schick et al., (2022) | 106 First Nation adolescents | 50% female | AHBQ | SCS-SF | cross-sectional | Examine the relations among life satisfaction, subjective happiness, self-compassion, alcohol use, and other drug use | • Self-compassion not significantly correlated with lower lifetime or current alcohol use • Other models did not separately examine self-compassion, but it was not associated with any current or lifetime alcohol use when modeled together |

| Spillane et al., (2022) | 106 First Nation adolescents | 50% female | ADQ RAPI |

SCS-SF | cross-sectional | Examine how self-compassion relates to alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and AUD risk | • Self-compassion inversely associated with alcohol-related problems and significantly interacted with frequency of alcohol use in predicting alcohol-related problems (significant for low self-compassion but not high self-compassion) |

| Tanaka et al., (2011) | 117 adolescents | 45% male 27% white |

AUDIT | SCS | longitudinal † | Test relations among childhood maltreatment, self-compassion, and psychological and behavioral health outcomes | • Childhood abuse related to lower self-compassion, which in turn was related to higher alcohol problems |

| Warner et al., (2022) | 200 individuals in a PTSD partial hospitalization program | 85% female 85% white |

MINI PAI Addiction-Related Personality Traits Index |

SCS-SF | longitudinal † | Examine the relationships between personality traits, self-compassion, PTSD symptom severity, and substance use | • Alcohol abuse and estimated alcohol problems were negatively correlated with self-compassion • Alcohol use severity and alcohol dependence were not significantly correlated with self-compassion • Addiction-Related Personality Trait Index negatively correlated with self-compassion |

| Wisener & Khoury (2019) | 170 undergraduates | 100% female Not reported |

YAACQ | SCS | cross-sectional | Examine associations among mindfulness, self-compassion, drinking motives, and alcohol problems | • Self-compassion related to higher drinking to cope with depression and anxiety |

| Wisener & Khoury (2020a) | 174 undergraduates | 85% female 70% white |

YAACQ | SCS | cross-sectional | Test if self-compassion is associated with alcohol problems via drinking to cope with anxiety and depression | • Self-compassion negatively associated with alcohol problems via drinking to cope with anxiety, but not depression |

| Wisener & Khoury (2020b) | 146 undergraduates | 56% female 72% white |

AUDIT | SCS | cross-sectional | Examine relations of mindfulness and self-compassion with coping-motivated drinking and test whether relations differ by sex | • Self-compassion negatively related to drinking to cope with depression, but not anxiety, across women and men |

| Treatment/Recovery from Alcohol Use and Problems | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Reference | Sample | Measures | Study Design | Study Aims | Key Findings | ||

| n/description | Demographics | Alcohol | SC | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Brooks et al., (2012) | 77 individuals in an outpatient drug and alcohol treatment service | 45% female Not reported |

OTI | SCS | longitudinal | Examine relations among self-compassion, depression, anxiety, stress, and alcohol use | • Significant improvements in self-compassion, positive judgement, and alcohol use from baseline to follow-up •Significant increases in overall self-compassion and the positive subscales from baseline to follow-up • Significant reduction in alcohol use correlated with increases in self-compassion |

| Garner et al., (2020) | 62 individuals in an intensive outpatient substance use treatment program | 65% male 94% white |

AUDIT | SCS | longitudinal | Test whether self-compassion is related to alcohol use over time | • Overall self-compassion not significantly related to alcohol use over time • Mindfulness subscale related to lower alcohol use for men, but not women • Self-kindness subscale related to decreased alcohol use for older participants and for women, but not for men |

Note.

= longitudinal study design, but relevant analyses were cross-sectional. ADQ = Adolescent Drinking Questionnaire (Jessor et al., 1989). AHBQ = Adolescent Health Behavior Questionnaire (Jessor et al., 1989). AUDIT = The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Saunders et al., 1993). MINI = Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998). OTI = Opiate Treatment Index (Darke et al., 1991). PAI = The Personality Assessment Inventory (Morey, 2007). PROMIS® AU-SF = PROMIS® Alcohol Use-Short Form (Pilkonis et al., 2013). PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. QFI = Quantity Frequency Index (Sobell & Sobell, 2003). RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (Martens et al., 2007). SCS = Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003a). SCS-SF = Self-Compassion Scale Short Form (Raes et al., 2011). SUD = Substance Use Disorder. YAACQ = Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Read et al., 2006). YAAPST = Young Adults Alcohol Problems Screening Test (Hurlbut & Scher, 1992).

Self-Forgiveness

Research identified exploring self-forgiveness in alcohol risk (k = 7) comprised exclusively cross-sectional investigations conducted within undergraduates (k = 6; Mage = 21 – 23 years) and veterans seeking trauma-focused treatment services (k = 1; Mage = 45 years; Table 2). Research into self-forgiveness in alcohol treatment/recovery outcomes (k = 11), in contrast, was conducted primarily through longitudinal designs (k = 9) among samples beginning or receiving treatment (k = 10) as well as individuals with alcohol use disorder receiving varying levels of treatment support (k = 2). Self-forgiveness was assessed through the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (k = 6; Fetzer Institute, 1999), Heartland Forgiveness Scale (k = 5; Thompson et al., 2005), The Forgiveness Scale (k = 5; Mauger et al., 1992), and its Polish adaption (k = 2; Toussaint et al., 2001; Charzyńka & Heszen, 2013), and the Self-Forgiveness Feeling and Action scale (k = 1; Wohl et al., 2008). Alcohol outcomes included alcohol consumption and problems/consequences.

Table 2.

Self-Forgiveness and Alcohol Outcomes

| Risk for Alcohol Use and Problems | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Reference | Sample | Measures | Study Design | Study Aims | Key Findings | ||

| n/description | Demographics | Alcohol | SF | ||||

| Dangel & Webb (2018) | 577 undergraduates | 60% female 90% white |

CAPS | HFS | cross-sectional | Test whether psychological distress impacts the relation of forgiveness with substance use outcomes | • Higher self-forgiveness associated with lower psychache and depressive symptoms, which were associated with fewer alcohol problems |

| Ellingwood et al., (2018) | 84 undergraduates | 64% female 47% white |

QFI | HFS | cross-sectional | Characterize relations between self-compassion, forgiveness, and alcohol use | • Higher self-forgiveness found among drinkers, compared to non-drinkers |

| Smigelsky et al., (2019) | 212 veterans | 86% male 58% black |

AUDIT | HFS | cross-sectional | Explore patterns of symptoms (including alcohol misuse and self-forgiveness) of morally injurious events | • Self-forgiveness was not related to hazardous alcohol use and did not meaningfully distinguish between the profiles |

| Ianni et al., (2010) | 567 undergraduates | Not reported Not reported |

AUDIT | HFS | cross-sectional | Assess whether shame moderates associations of self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes | • Shame significantly moderated self-forgiveness and alcohol relations, such that higher shame with higher self-forgiveness was related to better alcohol outcomes while higher shame with lower self-forgiveness was related to poorer outcomes |

| Webb & Brewer (2010) | 721 undergraduates | 72% female 92% white |

AUDIT | BMMRS | cross-sectional | Investigate associations between forgiveness and alcohol outcomes | • Self-forgiveness was the lowest dimension of forgiveness among students with problematic drinking • Self-forgiveness was the only dimension to be associated with the AA concept related to relapse (HALT), such that higher self-forgiveness led to reduced risk for relapse. |

| Webb et al., (2012) | 126 undergraduates | 60% female 85% white |

AUDIT | BMMRS | cross-sectional | Examine whether social support impacts relations of forgiveness to alcohol outcomes | • Higher self-forgiveness related to lower perception of socially undermining relationships, which was related to lower alcohol use and problems |

| Webb et al., (2013) | 126 undergraduates | 60% female 85% white |

AUDIT | BMMRS | cross-sectional | Examine whether mental health and social support impact relations of forgiveness to alcohol outcomes | • Higher self-forgiveness was indirectly related to lower alcohol outcomes through greater mental health and social support |

| Treatment/Recovery from Alcohol Use and Problems | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Reference | Sample | Measures | Study Design | Study Aims | Key Findings | ||

| n/description | Demographics | Alcohol | SF | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Charzyńska (2015) | 112 outpatient individuals | 50% male Not reported |

†None | PFS | longitudinal | Characterize sex differences in spiritual coping, gratitude, and forgiveness across an alcohol treatment program | • Self-forgiveness was the lowest of three dimensions of forgiveness at baseline and did not significantly increase during treatment for men or women |

| Charzyńska et al., (2018) | 245 outpatient individuals | 71.4% male Not reported |

‡None | PFS | longitudinal | Explore individual differences in moral virtues (including self-forgiveness) across alcohol treatment | • Greatest increases in self-forgiveness found among individuals with low and high levels of baseline SF • Self-forgiveness was still lowest of forgiveness dimensions to change over time. |

| Charzyńska et al., (2019) | 166 outpatient individuals matched with 166 in detoxication wards | 89% male Not reported |

‡None | PFS | cross-sectional | Examine the role of forgiveness and gratitude in the quality of life among persons who just started alcohol addiction therapy and Alcohol dependent individuals who have never attended alcohol addiction therapy | • Alcohol-dependent individual who have never participated in alcohol addiction therapy had higher self-forgiveness and higher feeling of being forgiven by God but lower gratitude and physical quality of life • Self-forgiveness in the non-treatment group had a partial indirect effect on mental quality of life • Self-forgiveness in this study was proposed to potentially be “pseudo” self-forgiveness, such that results might not reflect true self-forgiveness |

| Charzyńska (2021) | 323 outpatient individuals | 71% male Not reported |

‡None | PFS | cross-sectional | Identify distinct profiles of persons beginning alcohol addiction therapy (using measures of spiritual coping, forgiveness, gratitude prior to treatment) and examine associations between profiles and completion of therapy | • Self-forgiveness not significantly correlated with therapy completion individually • Profile with the greatest probability of completing treatment included high levels of self-forgiveness (as well as high gratitude, positive spiritual coping, and low negative spiritual coping) • Profile with highest level of self-forgiveness and low positive religious coping (potentially indicative of “pseudo” self-forgiveness) was least likely to complete treatment |

| Krentzman et al., (2017) | 364 outpatient individuals with AUD diagnosis | 34% female 82% white |

TFI | TFS | longitudinal | Investigate associations of AA involvement and alcohol use with dimensions of spirituality, including self-forgiveness | • Greater self-forgiveness and purpose in life related to reductions in drinking across 6–30 months |

| Krentzman et al., (2018) | 365 outpatient individuals with AUD diagnosis | 34% female 82% white |

§None | TFS | longitudinal | Examine changes in self-forgiveness/FO over 30 months among individuals who reduced their drinking behaviors | • Significant increases in both self-forgiveness and FO found • Self-forgiveness began significantly lower than forgiveness of others, yet increased more rapidly over time |

| Robinson et al., (2011) | 364 individuals with alcohol dependence | 66% male 82% white |

TLFB SIP |

TFS | longitudinal | Examine whether spiritual and religiousness changes predict drinking outcomes in those with alcohol dependence after controlling for AA involvement | • Self-forgiveness increased over time • Self-forgiveness predicted decreases in percentage of days abstinent and days since last drink in nine months • Increases in self-forgiveness predicted percentage of heavy drinking days and drinks per drinking day |

| Scherer et al., (2011) | 79 outpatient individuals | 75% male 95% white |

¶None | SFFA | longitudinal | Test whether a brief self-forgiveness intervention promotes self-forgiveness and increases drinking refusal self-efficacy in those in treatment for alcohol abuse or dependence | • Greater increases in self-forgiveness and drinking refusal self-efficacy found in the self-forgiveness intervention condition compared to TAU, with differences persisting up to 3 weeks following end of intervention. |

| Webb et al., (2006) | 157 outpatient individuals | 66% male 81% white |

SIP TLFB |

BMMRS | longitudinal | Examine relations among forgiveness, religiousness, spirituality, and alcohol use | • Self-forgiveness the lowest dimension of forgiveness at baseline and follow-up, as well as slowest to change • Baseline higher levels of self-forgiveness related to lower alcohol use and problems over time |

| Webb et al., (2009) | 157 outpatient individuals | 66% male 81% white |

¶None | BMMRS | longitudinal | Investigation associations among forgiveness and mental health | • Self-forgiveness and FO most strongly related to mental health outcomes among dimensions of forgiveness • Self-forgiveness and forgiveness of others predicted 6-month mental health outcomes after controlling for demographics and baseline mental health, particularly for depression |

| Webb et al., (2011) | 149 outpatient individuals | 55% male 85% white |

¶None | BMMRS | longitudinal | Examine whether mental health and social support impact relations of forgiveness with alcohol use | • Baseline self-forgiveness related to lower alcohol problems and psychiatric distress, but not to social support • Relations of self-forgiveness with alcohol problems at follow-up had indirect effects through psychiatric distress (but not social support) • Relations of self-forgiveness with change in alcohol problems from baseline to follow-up not significant |

Note.

= Individuals diagnosed with AUD (AUD diagnostic tool not provided) in parent study.

= Sample of individuals receiving out-patient treatment for alcohol addiction.

= Sample of AA members in active recovery.

= Sample of individuals with AUD diagnosis (diagnosed with DSM-IV). AA = Alcoholics Anonymous.). AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder. AUDIT = The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Saunders et al., 1993). BMMRS = Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (Fetzer Institute, 1999). CAPS = College Alcohol Problems Scale (Maddock, Laforge, Rossi, & O’Hare, 2001). HFS = Heartland Forgiveness Scale (Thompson et al., 2005). FO = Forgiveness of Others. PFS = A Polish adaption of The Forgiveness Scale, indices of forgiveness proposed by Toussaint et al., (2001) and adapted by Charzyńka & Heszen (2013). QFI = Quantity Frequency Index (Sobell & Sobell, 2003). SIP = Short Index of Problems ( Forcehimes et al., 2007; Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995). SFFA = Self-Forgiveness Feeling and Action (Wohl, DeShea, & Wahkinney, 2008). TAU = Treatment as Usual. TLFB = The Timeline Followback Interview (Sobell & Sobell, 1992). TFS = The Forgiveness Scale (Mauger et al., 1992).

Associations of Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness with Risk for Alcohol Outcomes

Self-Compassion

Findings generally demonstrated that higher levels of dispositional self-compassion correlated negatively with alcohol use (r = –0.23 to –0.22; Schick et al., 2021; Spillane et al., 2022), alcohol problems (rs = –0.27 to –0.13; Miron et al., 2014; Schick et al., 2021; Spillane et al., 2022; Wisener & Khoury, 2020a), and problematic drinking patterns (rs = –0.28 to –0.21; Forkus et al., 2019, 2020; Spillane et al., 2022; Tanaka et al., 2011, but see (Kaplan et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2019; Schick et al., 2022; Wisener 2019). Such relationships were suggested to be driven by drinking to cope with anxiety (i.e., atemporal indirect effects; ab = –0.98; Wisener & Khoury, 2020a). Associations between alcohol use and self-compassion scores were negative (Warner et al., 2022). Research also demonstrated that any associations of self-compassion with alcohol outcomes might be relatively stronger among more frequent drinkers (t = –2.12; Spillane et al., 2022) or adolescents experiencing greater racial discrimination (βs = –0.27 to –0.18; Schick et al., 2021). Finally, self-compassion was suggested as a mechanism underlying trauma-related drinking such that childhood emotional abuse and PTSD symptoms (z = 2.18) related to lower self-compassion that, in turn, was related to greater problem drinking (i.e., atemporal indirect effects; Forkus et al., 2020; Miron et al., 2014).

Self-Forgiveness

Self-forgiveness was consistently, negatively correlated with problematic patterns of alcohol use (r = –0.40 to –0.10; Dangel & Webb, 2018; Ianni et al., 2010; Webb, Robinson, Brewer, 2010; Webb, Hill, & Brewer, 2012; Webb et al., 2013), but see (Smigelsky et al., 2019), yet was more mixed when general (non-problem) alcohol consumption was examined (r = –0.06 to r = 0.15; Webb, Robinson, Brewer, 2010; Webb et al., 2013). Research identified suggested that relations of self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes might be driven by several psychosocial mechanisms (i.e., atemporal indirect effects), including depression (ab = –0.91; Dangel & Webb, 2018), psychache (i.e., intense psychological pain leading to risk for suicide, Schneidman, 1998; ab = –0.08; Dangel & Webb, 2018); social undermining (abs = –0.80 to –0.23; Webb, Hill, & Brewer, 2012), social support (abs = –0.30; Webb et al., 2013), and mental health status (abs = –0.60 to –0.21; Webb et al., 2013). Specifically, greater self-forgiveness related to lower depression, psychache, and social undermining as well as greater social support and mental health status that, in turn, related to less problematic drinking (Dangel & Webb, 2018; Webb, Hill, & Brewer, 2012; Webb et al., 2013). Research also suggested self-forgiveness might be most protective against problem drinking among those endorsing high shame (Ianni et al., 2010).

Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness

Both theory and empirical data suggest associations of self-compassion and self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes, which would imply that considering each in the context of the other is important. However, we found only one study examining self-compassion and self-forgiveness together in the prediction of alcohol outcomes (Ellingwood et al., 2018; Tables 1 and 2). Results from this study suggested that, contrary to hypotheses, nondrinkers reported lower levels of self-compassion and self-forgiveness than binge and social drinkers (F = 2.18). Notably, however, these associations varied across self-compassion subscales. Specifically, only two of the three positive self-compassion subscales (i.e., self-kindness and mindfulness) were significantly linked to higher drinking classifications.

Associations of Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness with Treatment of and Recovery from Problem Alcohol Involvement

Self-Compassion

Studies on the role of self-compassion in treatment/recovery for problematic alcohol involvement were few in number and mixed with regard to findings (Table 1). Specifically, improvements in the self-kindness (r = 0.36) and isolation (r = 0.48) aspects of self-compassion related to reductions in alcohol use from baseline to 15-weeks post-treatment among individuals in an outpatient alcohol or drug treatment service, despite the provided interventions not specifically targeting self-compassion (Brooks et al., 2012). However, overall self-compassion was not significantly related to alcohol use up to four months following the end of 60-day outpatient treatment within another outpatient substance use treatment sample (Garner et al., 2020). The mindfulness subscale significantly predicted a decrease in largest number of drinks on one occasion. Additionally, associations varied considerably across self-compassion subscales for men and women of different ages. Specifically, mindfulness was negatively related to alcohol use for men, but higher alcohol use for women. Greater self-kindness related to somewhat lower alcohol use for women, but higher alcohol use for men. Self-kindness predicted a decrease in the peak drinking for older participants, but an increase in younger participants. Common humanity related to lower alcohol use for women but not men.

Self-Forgiveness

Self-forgiveness tended to be inversely related to drinking days (r = 0.17), alcohol consumption (r = –0.26 to –0.24) and alcohol problems (r = –0.37) among individuals beginning alcohol use treatment (Webb et al., 2006). Self-forgiveness also tended to increase significantly over time among individuals in outpatient alcohol use treatment (Charzyńska, Gruszczyńska, & Heszen, 2018; Krentzman et al., 2017, 2018; Robinson et al., 2011; Scherer et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2006, 2009), but see (Charzyńska, 2015). Greater self-forgiveness also predicted favorable alcohol outcomes across treatment, including reductions in both drinking and heavy-drinking days as well as drinking quantity (Robinson et al., 2011). Research pointed to psychiatric distress as a mechanism of these associations, whereby greater self-forgiveness related to lower psychiatric distress that in turn related to lower alcohol outcomes (abs = –3.54 to 4.02; i.e., atemporal indirect effects; Webb 2011). Research identified also suggested self-forgiveness (or perhaps a form of pseudo self-forgiveness) might relate to lower treatment engagement, such that individuals with no interest starting addiction therapy tended to have higher levels of self-forgiveness that in turn related to higher perceived mental health-related quality of life (Charzyńska et al., 2019).

Research examining interventions designed to promote self-forgiveness in an effort to improve alcohol outcomes was less conclusive. Specifically, individuals receiving a three-week self-forgiveness-based intervention within an alcohol abuse treatment program reported significantly greater improvements in both self-forgiveness (t = 6.96) and drinking refusal self-efficacy (t = 2.56) than those randomized to treatment as usual, which were maintained by three weeks post-treatment (Scherer et al., 2011). However, it remained unexplored whether such growth in turn related to lower alcohol use or AUD symptoms (Scherer et al., 2011).

Discussion

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness are conceptually related, potentially malleable factors that may protect against deleterious alcohol outcomes as well as aid in successful treatment for and/or recovery from problem alcohol involvement. However, knowledge regarding the contributions of self-compassion, self-forgiveness, and both constructs together to drinking outcomes remains limited. The present review summarized the strength of existing literature on self-compassion and self-forgiveness in alcohol outcomes, including potential mechanisms through which self-compassion/self-forgiveness affect alcohol outcomes and/or individual differences in such relations. We now summarize the major findings from our review, their implications for the field, and several suggested future directions for both research and intervention, focusing on the role of self-compassion and self-forgiveness in (1) risk for problem alcohol involvement and (2) AUD recovery and treatment outcomes.

Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness in Risk for Problem Alcohol Involvement

Self-Compassion

Research summarized in our review suggests that higher levels of dispositional self-compassion relate to decreased alcohol use and problems, possibly through reductions in drinking to cope with anxiety. Drinking – especially problem drinking – often can be driven by a desire to ameliorate or cope with negative affect (Cooper, 1994). Self-compassion may offer a more adaptive coping response to negative or anxious affect, thereby resulting in reduced motivation toward coping-motivated drinking. Nevertheless, importantly, extant research on the mechanisms through which dispositional self-compassion may protect against harmful alcohol outcomes has been exclusively cross-sectional. Mechanistic processes are best tested in longitudinal designs that allow for the delineation of temporal ordering, and longitudinal examinations of the mechanisms that undergird self-compassion’s association with alcohol outcomes are needed. Further, future research should examine whether self-compassion may increase positive emotional states (see Held et al., 2018) in addition to facilitating the management of negative affect.

Self-compassion may play a particularly important, yet also complex, role in the etiology of problem drinking specifically in the aftermath of adverse life events. That is, self-compassion may reduce the likelihood of posttraumatic problem drinking by encouraging reconciliation with painful emotions, self-kindness, and appreciation for the shared human experience of pain and negative experience (Neff, 2003a, 2003b), thereby reducing the need to cope with traumatic distress through drinking. However, it has yet to be examined whether self-compassion modulates posttraumatic drinking risk (i.e., moderation) whereby it is particularly protective for trauma-exposed drinkers. Self-compassion also may serve as a mechanism through which stressful experiences influence later drinking risks (i.e., mediation), and limited research identified in this review supports lower levels of self-compassion among trauma-exposed individuals that correlate with greater problematic drinking (Forkus et al., 2020; Miron et al., 2014). Future mechanistic work aimed at disentangling the potential roles of self-compassion as a protective factor and/or mechanism of alcohol outcomes following adversity could lead to clinical efforts aimed at increasing self-compassion in trauma-exposed individuals to improve adaptive emotion regulation, thereby decreasing risk for negative alcohol outcomes.

Self-Forgiveness

Across research identified in this review, self-forgiveness was linked to lower risk for problem alcohol involvement, suggesting a protective role. Findings regarding patterns of non-problem alcohol consumption were more mixed. Self-forgiveness might protect against problem drinking specifically by reducing emergence of negative affect states commonly associated with problem alcohol consumption (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Davis et al., 2015; Barnard & Curry, 2011). Research identified here offered some support for the former potential mechanism whereby self-forgiveness related to lower depression and psychache that in turn related to lower problem drinking (Dangel & Webb, 2018). Self-forgiveness also was related to greater social support and adaptive mental health status to in turn relate to lower problem drinking (Webb et al., 2013), perhaps suggesting a potential mechanism. Self-forgiveness may lead to fulfilling social connections, which could offer resilience to alcohol use in the face of psychological and physical health problems (Worthington, Berry, & Parrott., 2001). These findings are intriguing, yet, as with self-compassion, extant literature has relied exclusively on cross-sectional designs to examine potential mechanisms. Prospective research is needed to better delineate the pathways through which self-forgiveness may protect against problem drinking.

Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness

Efforts to better understand the complementary and/or unique roles of self-compassion and self-forgiveness in alcohol outcomes could help maximize their utility for alcohol prevention and intervention efforts. However, only one study examined both self-compassion and self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes in the same sample (Ellingwood et al., 2018). Somewhat surprisingly, this study suggested lower self-compassion and self-forgiveness among nondrinkers relative to drinkers (Ellingwood et al., 2018). Participants in this sample may have conflated self-kindness with self-indulgence in their reports, perhaps viewing their alcohol consumption as a form of kindness to oneself (also see Brooks et al., 2012). Future research should explore how participants interpret items assessing self-compassion, self-forgiveness, and self-kindness. Ultimately, however, these conflicting findings derive from a single, modest sample (n = 84), and self-compassion and self-forgiveness were not tested concurrently in the same model to characterize their unique influences on risk for alcohol outcomes. Further research ultimately is needed to understand their complementary and/or unique contributions to alcohol outcomes.

Self-Compassion and Self-Forgiveness in Treatment of and Recovery from Problem Alcohol Use

Self-Compassion

Limited findings from this review suggest mixed evidence for the role of self-compassion in alcohol treatment outcomes. Self-compassion’s role in treatment outcomes may vary as a function of client characteristics, type/intensity of treatment, severity of alcohol involvement, and/or culture, which appear yet to be explored in the literature. Efforts to identify individual differences in self-compassion’s role in alcohol treatment outcomes could inform eventual personalized self-compassion-based treatment approaches. Research also suggests possibly differing associations across the subdomains of self-compassion (Garner et al., 2020). Future research considering the multidimensional nature of self-compassion could provide insight into the subdomains that would be more clinically useful in mapping changes in self-compassion across treatment and/or more beneficial to target in self-compassion-based interventions. Finally, it also is possible that some forms of alcohol treatment may be somewhat more effective at linking increases in self-compassion to reductions in alcohol outcomes. Several compassion-based interventions designed to cultivate compassion, self-compassion, and/or mindfulness have been successful in decreasing psychological distress, anxiety, and depression (Kirby, Tellegen, & Steindl, 2017), and at least one such intervention has been implemented among individuals with substance use disorder (Held et al., 2018). Compassion-based interventions could be modified for AUD treatment by highlighting specific linkages of self-compassion with alcohol outcomes as explicated here.

Self-Forgiveness

Research does not appear to have tested yet whether interventions designed to increase self-forgiveness lead to reductions in harmful drinking outcomes, although offers limited support from one study that such interventions may improve drinking refusal self-efficacy and decrease shame/guilt (Scherer et al., 2011). Shame, in particular, can lead to negative self-evaluations, negative self-worth, and avoidance and isolation behaviors (Holl et al., 2017), all of which have been linked to more problematic drinking behaviors. Thus, self-forgiveness interventions that reduce shame may ultimately be successful avenues for AUD treatment, and this remains an important direction for future investigation. Surprisingly, the present review also suggests self-forgiveness may relate to reduced treatment engagement and retention (Charzyńska et al., 2019). Low treatment retention presents a considerable barrier to effective alcohol treatment (Hubbard et al., 1997). Future work should examine whether self-forgiveness plays a role in treatment engagement and/or retention to inform clinical work.

Clinical Implications

Findings from this review generally suggest that self-compassion relates to lower risk for alcohol use and problems. Self-forgiveness related to lower risk for problematic alcohol use in particular, more so than general alcohol use. Self-compassion may play an important role in reducing general alcohol consumption, perhaps by helping individuals more effectively manage general stress and negative affect to reduce coping-motivated drinking risk. Drinking prevention efforts thus may benefit from working to enhance self-compassion to reduce development of problem drinking. Self-compassion-based drinking prevention efforts also could prove useful in helping adolescents and young adults develop adaptive self-compassionate mindsets to reduce likelihood of coping-motivated drinking as they approach developmental periods of peak drinking risk. Self-forgiveness, in slight contrast, might play a relatively stronger role in drinking risks following onset of problematic alcohol use. Problem drinkers who have experienced significant or clinically impairing alcohol consequences may benefit from reconciling harsh self-criticism for perceived prior wrongdoing(s) related to heavy drinking. Self-forgiveness may help such individuals reduce shame, guilt, or self-blame related to prior alcohol consequences that otherwise might exacerbate or maintain problematic drinking. Early interventions among individuals with alcohol problems might be well-served to target self-forgiveness in an effort to dismantle cyclical patterns of shame-based problem drinking.

Self-forgiveness appeared relatively more researched and also more supported in relation to treatment and recovery outcomes for AUD. Specifically, self-forgiveness tended to increase considerably across alcohol treatment, and one self-forgiveness-based intervention appeared to improve drinking-adjacent outcomes (i.e., drinking refusal self-efficacy, shame, guilt). Self-compassion demonstrated more limited and also mixed support in relation to treatment and recovery outcomes. Self-forgiveness might offer drinkers in treatment the ability to more adaptively process condemnation-focused beliefs related to their perceptions of their prior drinking behaviors, which might arise when reflecting on alcohol consequences during treatment. However, the present review did not identify any studies that tested whether interventions designed to increase self-forgiveness (or self-compassion) can successfully reduce deleterious alcohol outcomes. More research is needed to definitively address this question. Such efforts also could explore whether self-compassion- and/or self-forgiveness-based interventions may best serve as adjuncts to more traditional, existing alcohol use treatments.

Across our review of the literature, we found only one study (Ellingwood et al., 2018) that examined self-compassion and self-forgiveness within a single sample. The unique and combined influence of these two constructs has not been well examined. This has obvious implications for interventions, as it currently is unclear whether it is sufficient to focus on one or the other of these constructs in intervention, or whether there is benefit to targeting both together.

Limitations

Several limitations of the review approach should be considered. First, eligible articles were required to be written in English; self-compassion derives from Buddhist principles such that relevant non-English articles from regions of the world where Buddhism is more prevalent may have been excluded. Second, the databases searched indexed research dating back to 1972 such that our review may have missed older, relevant literature. However, we believe this to be unlikely, given that much of the interest in self-compassion and self-forgiveness in psychological research has emerged only relatively recently (Strauss et al., 2016; Chen, 2019; Davis et al., 2015; Webb, Toussaint, & Hirsch, 2011). Finally, our eligibility criteria retained studies focused on self-compassion and self-forgiveness specifically, which excluded a sizeable portion of studies examining overall forgiveness.

Several limitations to the extant literature itself also may limit the strength of conclusions from the present review. First, studies identified tended to be based on relatively small, non-random convenience samples that were overly represented by non-Hispanic White participants. Therefore, caution is needed when generalizing findings from this body of research. Second, as noted previously, studies overwhelmingly were cross-sectional, thus precluding temporal interpretations. Finally, the research reviewed here relied primarily on self-report data. Although self-reports of self-compassion, self-forgiveness, and alcohol outcomes have been found to be reliable (Neff, 2003b; Thompson et al., 2005; Del Boca & Darkes, 2003; Gruenewald & Johnson, 2006), self-report or memory biases nonetheless are possible.

Conclusion

The present review was the first to synthesize evidence on self-compassion and self-forgiveness in relation to alcohol outcomes. Findings suggest that self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness may relate to decreased risk for problematic drinking and perhaps also to some improved treatment and recovery outcomes for those with AUD. Future research also will benefit from identifying and testing mechanisms underlying associations of self-compassion and self-forgiveness with alcohol outcomes through prospective research. More data also are needed to understand individual differences in such relations to best leverage knowledge on self-compassion and/or self-forgiveness in the prevention and treatment of AUD. Finally, these findings highlight the need for work that examines self-compassion and self-forgiveness in alcohol use or consequences simultaneously, in order to characterize their complementary and/or unique roles in alcohol involvement.

Key Practitioner Message:

Self-compassion and self-forgiveness both represent complementary, self-focused positive emotion regulation approaches theorized to protect against adverse alcohol outcomes.

Self-compassion appears protective against alcohol use and problems, and self-forgiveness appears protective against problematic alcohol use in particular.

Self-forgiveness tends to increase significantly across alcohol treatment, and self-forgiveness-based interventions have shown some promise in improving drinking-related outcomes (i.e., drinking refusal self-efficacy, shame).

Future research should examine whether self-compassion- and/or self-forgiveness-focused prevention or intervention efforts can reduce emergence of problem drinking or improve alcohol use disorder symptomatology.

Acknowledgements:

Research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers T32 AA007583, K99 AA029728, and R00 AA029728. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability Statement:

N/A

References

- Barnard LK, & Curry JF (2011). Self-Compassion: conceptualizations, Correlates, & Interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Braun TD, Green Z, Meshesha LZ, Sillice MA, Read J, & Abrantes AM (2023). Self-compassion buffers the internalized alcohol stigma and depression link in women sexual assault survivors who drink to cope. Addictive Behaviors, 138, 107562. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton PC (2004). The relation of coping strategies to alcohol consumption and alcohol related consequences in a college sample. Addiction Research & Theory, 12, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks M, Kay-Lambkin F, Bowman J, & Childs S. (2012). Self-Compassion Amongst Clients with Problematic Alcohol Use. Mindfulness, 3, 308–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, & Ray LA (2016). Experimental psychopathology paradigms for alcohol use disorders: Applications for translational research. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E. (2015). Sex Differences in Spiritual Coping, Forgiveness, and Gratitude Before and After a Basic Alcohol Addiction Treatment Program. Journal of Religion and Health, 54, 1931–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E. (2021). The effect of baseline patterns of spiritual coping, forgiveness, and gratitude on the completion of an alcohol addiction treatment program. Journal of Religion and Health. 10.1007/s10943-021-01188-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E, & Heszen I. (2013). Zdolnos ´c ´ do wybaczania i jej pomiar przy pomocy polskiej adaptacji Skali Wybaczania L. L. Toussainta, D. R. Williamsa, M. A. Musicka i S. A. Everson [The capacity to forgive and its measurement with the Polish adaptation of The Forgiveness Scale L. L. Toussaint, D. R. Williams, M. A. Musick and S. A. Everson]. Przegla ˛d Psychologiczny, 56(4), 423–446. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E, Gruszczyńska E, & Heszen I. (2018). Forgiveness and gratitude trajectories among persons undergoing alcohol addiction therapy. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(4), 282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E, Gruszczyńska E, & Heszen-Celińska I. (2019). The role of forgiveness and gratitude in the quality of life of alcohol-dependent persons. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(2), 173–182. 10.1080/16066359.2019.1642332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. (2019). The Role of Self-Compassion in Recovery from Substance Use Disorders. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 4(2), doi: 10.21926/obm.icm.1902026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: development and validation of a four factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Farmer NM, & Nolen-Hoekesma. (2013). Relations among stress, coping strategies, coping motives, alcohol consumption and related problems: A mediated moderation model. Addictive Behaviors, 38, 1912–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangel T, & Webb JR (2018). Forgiveness and substance use problems among college students: Psychache, depressive symptoms, and hopelessness as mediators. Journal of Substance Use, 23(6), 618–624. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ward J, Hall W, Heather N. & Wodak A (1991). The opiate treatment index (OTI) manual, National Drug and Alcohol Reseach Centre, 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Davis DE, Griffin BJ, Hook JN, DeBlaere C, Yo MY, Bell C, Van Tongeren DR, & Worthington EL Jr. (2015). Forgiving the Self and Physical and Mental Health Correlates: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, & Darkes J. (2003). The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction, 98, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, & Williams TJ (2014). The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40(2), 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas KJ, & Williams TJ, (2014). Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: associations with emotion regulation difficulties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40 (2), 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingwood L, Espinoza M, Acevedo M, & Olson LE (2019). College Student Drinkers Have Higher Self Compassion Scores than Nondrinkers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD (1996). Counseling within the forgiveness triad: On forgiving, receiving forgiveness, and self-forgiveness. Counseling & Values, 40(2), 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD, Freedman S, & Rique J. (1998). The Psychology of Interpersonal Forgiveness. Enright RD, North J. ed. Exploring Forgiveness. University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert C, Vater A, & Schröder-Abé M. (2021). Self-Compassion and Coping: a Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness, 12(2). [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging working group, with additional psychometric data. Kalamazoo, MI: Corporate. [Google Scholar]

- Forcehimes AA, Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Kenna GA, & Baer JS (2007). Psychometrics of the drinker inventory of consequences (DrInC). Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1699–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkus SR, Breines JG, & Weiss NH (2019). Morally Injurious Experiences and Mental Health: The Moderating Role of Self-Compassion. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(6), 630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkus SR, Breines JG, & Weiss NH (2020). PTSD and Alcohol Misuse: Examining the Mediating Role of Fear of Self-Compassion Among Military Veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 364–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AR, Gilbert SE, Shorey RC, Gordon KC, Moore TM, & Stuart GL (2020). A Longitudinal Investigation on the Relation Between Self-Compassion and Alcohol Usein a Treatment Sample: A Brief Report. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 14, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. (2010). The compassionate mind. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, & Procter S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379. 10.1002/cpp.507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graser J, & Stangier U. (2018). Compassion and Loving-Kindness Meditation: An Overview and Prospects for the Application in Clinical Samples. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2005). Motives to Drink as Mediators Between Childhood Sexual Assault and Alcohol Problems in Adult Women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(2), 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, & Oei T. (1999). Alcohol and tension reduction. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. London, The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, & Johnson FW (2006). The stability and reliability of self-reported drinking measures. Journal of studies on alcohol, 67(5), 738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JH, & Fincham FD (2005). Self-Forgiveness: The Stepchild of Forgiveness Research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(5), 621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Hall JH, & Fincham FD (2008). The Temporal Course of Self-Forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(2), 174–202. [Google Scholar]

- Held P, Owens GP, Thomas EA, White BA, & Anderson SE (2018). A Pilot Study of Brief Self Compassion Training With Individuals in Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Traumatology, 24(3), 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Holl J, Wolff S, Schumacher M, Hocker A, Arens EA, Spindler G, Stopsack M, … & Cansas Study Group. (2017). Substance use to regulate intense posttraumatic shame in individuals with childhood abuse and neglect. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, & Etheridge RM (1997). Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11, 261–278 [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, & Sher KJ (1992). Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianni PA, Hart KE, Hibbard S, Carroll M. (2010). The Association Between Self-Forgiveness and Alcohol Misuse Depends on the Severity of Drinker’s Shame: Toward a Buffering Model. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 9(3). [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, & Costa FM (1989). Health Behavior Questionnaire. Boulder, CO: Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J, Bergman AL, Green K, Dapolonia E, & Christopher M. (2020). Relative impact of mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological flexibility on alcohol use and burnout among law enforcement officers. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 26(12), 1190–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The Self-Medication Hypothesis of Substance Use Disorders: A Reconsideration and Recent Applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(6), 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo HJ, Sheen SS, Hahn S, ... & Son, H. J. (2013). Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(4), 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Strobbe S, Harris JI, Jester JM, & Robinson EAR (2017). Decreased Drinking and Alcoholics Anonymous Are Associated With Different Dimensions of Spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(1), 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Webb JR, Jester JM, & Harris JI (2018). Longitudinal Relationship Between Forgiveness of Self and Forgiveness of Others Among Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorders. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(2), 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, & Steindl SR (2017). A Meta-Analysis of Compassion-Based Interventions: Current State of Knowledge and Future Directions. Behavior Therapy, 48, 778–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Mack D, Enright RD, Krahn D, & Baskin TW (2004). Effects of forgiveness therapy on anger, mood, and vulnerability to substance use among inpatient substance dependent clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 1114–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Chwyl C, Kaplan J. (2019). Substance use and shame: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons GCB, Deane FP, Caputi P, & Kelly PJ (2011). Spirituality and the treatment of substance use disorders: an exploration of forgiveness, resentment and purpose in life. Addict Research & Theory, 19, 459–469. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A, & Gumley A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 32, 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]