Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Hospital adaptation and resiliency, required during public health emergencies to optimize outcomes, are understudied especially in resource-limited settings.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

What are the prepandemic and pandemic critical illness outcomes in a resource-limited setting and in the context of capacity strain?

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS:

We performed a retrospective cohort study among patients admitted to ICUs at two public hospitals in the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health in South Africa preceding and during the COVID-19 pandemic (2017–2022). We used multivariate logistic regression to analyze the association between three patient cohorts (prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, and pandemic COVID-19) and ICU capacity strain and the primary outcome of ICU mortality.

RESULTS:

Three thousand two hundred twenty-one patients were admitted to the ICU during the prepandemic period and 2,539 patients were admitted to the ICU during the pandemic period (n = 375 [14.8%] with COVID-19 and n = 2,164 [85.2%] without COVID-19). The prepandemic and pandemic non-COVID-19 cohorts were similar. Compared with the non-COVID-19 cohorts, the pandemic COVID-19 cohort showed older age, higher rates of chronic cardiovascular disease and diabetes, less extrapulmonary organ dysfunction, and longer ICU length of stay. Compared with the prepandemic non-COVID-19 cohort, the pandemic non-COVID-19 cohort showed similar odds of ICU mortality (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.25; P = .50) whereas the pandemic COVID-19 cohort showed significantly increased odds of ICU mortality (OR, 3.91; 95% CI, 3.03–5.05 P < .0005). ICU occupancy was not associated with ICU mortality in either the COVID-19 cohort (OR, 1.05 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.96–1.14; P = .27) or the pooled non-COVID-19 cohort (OR, 1.01 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.98–1.03; P = .52).

INTERPRETATION:

Patients admitted to the ICU before and during the pandemic without COVID-19 were broadly similar in clinical characteristics and outcomes, suggesting critical care resiliency, whereas patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 showed important clinical differences and significantly higher mortality.

Keywords: capacity strain, COVID-19, hospital adaptation, hospital resiliency, preparedness

In the face of public health emergencies and acute surge events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals are tested on their adaptation, the ability to improve care and outcomes for primarily affected (ie, infected) patients by implementing new care processes based on accumulated experience, and their resiliency, that is, the ability to continue to deliver high-quality care to patients not primarily affected (ie, bystander patients, those uninfected but who still require acute care during this time), despite the presence of a surge event.1–5

Although much attention during a respiratory viral acute surge event initially and naturally is focused on adaptation for primarily infected patients, the resiliency required for optimal care delivery and outcomes for uninfected bystander patients often is overlooked. However, it has the potential for large impacts on population health. Prepandemic research has demonstrated a relationship between acute capacity strain and poorer bystander patient outcomes within individual hospital wards.6 During the pandemic, COVID-19-related capacity strain has been associated with poorer outcomes for patients without COVID-19 or all-comer patients in ICUs, hospitals, and the general population.7–10

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused devastating illness globally. Despite a heavy burden of disease, resource-limited settings in general and on the African continent in particular remain underrepresented in pandemic research,11 and vaccination rates of < 30% portend a prolonged regional pandemic.12,13 In those studies that have focused on African patients during the pandemic, the absence of high-fidelity prepandemic local cohorts has restricted analyses to within-pandemic comparisons.14,15 It remains unclear whether the same adaptation and resiliency relationships persist in resource-limited settings, where important differences in ICU referral and admission practices and ICU resources exist, and in the face of differences in hospital and ICU capacity strain. In particular, our prior research has shown that ICU occupancy, as a metric of ICU capacity strain, is highly associated with ICU admission decisions in well-resourced settings.16,17 However, this relationship may not persist in resource-limited settings where more rigorous ICU gatekeeping practices exist in the context of more chronic scarcity and to preserve ICU beds for those patients most likely to benefit.18 Chronically resource-limited hospitals may be overwhelmed more easily by pandemic-related capacity strain or alternatively may be more resilient owing to experience with scarce resource allocation and critical care delivery under adverse circumstances. As part of the South Africa ICU Capacity Strain Study Group, we performed a retrospective cohort study to analyze critical care outcomes across three study cohorts (prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, and pandemic COVID-19) and across degrees of capacity strain.

Study Design and Methods

Study Setting and Data Source

The study data source was the Integrated Critical Care Electronic Database,19 which has been the source for multiple prior publications from the South Africa ICU Capacity Strain Study Group.18,20–22 The ICU database includes all referrals and admissions for ICU care at two public hospitals within the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa): Greys Hospital, a tertiary hospital with approximately 530 inpatient beds, and Harry Gwala Regional Hospital (formerly Edendale Hospital), a secondary or regional hospital with approximately 900 inpatient beds.

These hospitals serve the large local urban and suburban population, as well as patients referred from surrounding district and community hospitals. Each hospital has one multidisciplinary (ie, mixed medical and surgical) ICU that admits adult and pediatric (either primary or as overflow) patients and has closed, high-intensity staffing models typically led by an anesthesia or surgical critical care consultant (equivalent to an attending physician or surgeon in the United States). The critical care consultant oversees daytime rounds with a team of medical officers (generalist doctors) and registrars (trainees equivalent to resident physicians in the United States) who staff the ICU overnight in remote contact with the consultant.

The South African public health system, provided to citizens without out-of-pocket costs, treats approximately 84% of the population, but accounts for 43% of the country’s ICU beds. ICU case mix is notable for: comprising predominantly Black race, skewing male sex, including approximately 20% with HIV infection, and having ICU needs most commonly resulting from surgical issues (trauma and other postoperative monitoring) and infection. ICU beds at the study hospitals are allocated based on the Society of Critical Care Medicine ICU triage priority system and is typically limited to patients needing ICU-specific therapy (priority I) or intensive monitoring (priority II), with rare admissions of patients less likely (priority III), too well (priority IVA), or too sick (priority IVB) to benefit from ICU admission.18,23

The ICU database is integrated into the clinical ICU team real-time workflow and captures a discrete set of variables at the time of ICU referral and ICU admission and end-ICU disposition.18 Patient-level COVID-19 status was noted in the ICU database by the clinical teams in real time and was audited by the study team. National South Africa data on SARS-CoV-2 case and vaccination trends were extracted separately from the publicly available Our World in Data COVID-19 dataset,24 with raw data from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 data repository.25

Study Population

The study included adult (aged ≥ 18 years) patients admitted to the ICU at the study hospitals from January 1, 2017, through June 30, 2022, and included three patient cohorts: the prepandemic non-COVID-19 patient cohort admitted from January 1, 2017, through March 4, 2020, and the pandemic non-COVID-19 and pandemic COVID-19 patient cohorts admitted from March 5, 2020 (when South Africa recorded its first SARS-CoV-2 case24,25) through June 30, 2022. The prepandemic non-COVID-19 cohort included a subgroup of patients previously described and studied.20–22 The pandemic cohorts included pandemic periods and surges dominated by five viral variants in South Africa: Ancestral Wuhan strain (peak July 2020), Beta variant (peak January 2021), Delta variant (peak July 2021), Omicron BA.1/BA.2 subvariants (peak December 2021), and Omicron BA.4/BA.5 subvariants (peak May 2022).26

Study Design, Outcomes, and Patient-Level Covariates

We performed two coprimary retrospective cohort analyses to measure the association of (1) the three study cohorts (prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, and pandemic COVID-19) and (2) degrees of capacity strain, with the primary outcome of ICU mortality. ICU mortality was defined as a death in the ICU or a palliative discharge from the ICU.

Patient-level adjustment variables (recorded at ICU admission) for all models included: age, sex, HIV status, chronic cardiovascular disease, diabetes, medical vs surgical status, and study hospital.14 We additionally adjusted for the national cumulative count of fully vaccinated individuals, defined as completion of any primary vaccine series as of the calendar day of ICU admission (patient-level vaccination status was not available).24,25 We did not adjust for SARS-CoV-2 viral variant because we believed it would be colinear with COVID-19-based cohorts (an exposure variable), but we accounted for viral variants in secondary analyses described herein. Although we adjusted for chronic comorbidities, we elected not to adjust for acute physiologic features because this exists in the causal pathway between ICU admission indication (ie, COVID-19 vs non-COVID-19) and ICU outcomes.

Association of Peripandemic Cohort and ICU Mortality

In the first cohort analysis, we performed multivariate logistic regression assessing the association between patient cohort (ie, prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, or pandemic COVID-19) and ICU mortality, adjusted for patient-level covariates and national cumulative count of fully vaccinated individuals (first coprimary analysis). To account for a relationship between capacity strain and COVID-19 outcomes6,8,27,28 and based on prior work in this and other data sets,16,18,29 we performed a sensitivity analysis further adjusted for five capacity strain metrics: ICU occupancy, ICU referral burden, ICU turnover, ICU acuity (see e-Appendix 1 for metric definitions), and national 7-day rolling mean of incident SARS-CoV-2 cases per 1 million residents.24,25 To account for the high trauma proportion in the non-COVID-19 cohorts (35.5% prepandemic non-COVID-19 and 37.0% pandemic non-COVID-19 cohorts vs 5.5% in the pandemic COVID-19 cohort) and the important differences between trauma and nontrauma ICU admissions and outcomes, in another sensitivity analysis, we restricted the outcome to patients without trauma as the primary indication for ICU admission.

Association of Capacity Strain and ICU Mortality

In the second cohort analysis, we performed multivariate logistic regression assessing the association between ICU occupancy, as a continuous variable, and ICU mortality, now stratified by COVID-19 status and with the same strategy of patient-level adjustment (second coprimary analysis). We also report predicted probabilities of ICU mortality for ICU occupancy deciles.

Association Between Pandemic Surge Period and ICU Mortality

In a secondary analysis to account for different risk between SARS-CoV-2 viral variants, we performed multivariate logistic regression assessing the association between pandemic surge periods and ICU mortality, again with the same patient-level adjustment strategy. Pandemic surge periods (e-Table 1) were defined based on the dominant national variant26 and a national 7-day rolling mean of incident SARS-CoV-2 cases of ≥ 50 cases/1 million residents as of the calendar day of ICU admission.24,25 Periods between March 5, 2020, and June 30, 2022, with < 50 incident SARS-CoV-2 cases/1 million residents were considered between-surge periods.

Statistical Reporting

We calculated descriptive statistics of the prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, and pandemic COVID-19 cohorts and for the ICU capacity strain metrics and report ORs and predicted probabilities for logistic regression models. Sample size estimations were performed assuming a two-sided test with a type I error rate (α) of 5% and 80% power (type II error rate [β], 20%). For the association between peripandemic cohorts and ICU mortality, based on available sample size, we estimated a detectable OR of 1.21 for the pandemic non-COVID-19 cohort and a detectable OR of 1.37 for the pandemic COVID-19 cohort.30 For the association between ICU occupancy and ICU mortality, based on available sample size and allowing for a strong correlation between covariates (R2 0.6), we estimated a detectable mortality effect difference of 2.6% for the pooled non-COVID-19 cohort and a detectable mortality effect difference of 9.2% for the pandemic COVID-19 cohort.31 Missing values for model outcomes, exposures, and covariates were low (< 1%), allowing for a complete case analysis. P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant and 95% CIs are presented throughout. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp LP).

The study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Harry Gwala Regional Hospital (“Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Admitted With COVID-19 to a South African ICU,” March 16, 2022, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa) and Greys Hospital (“Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Admitted With COVID-19 to South African Regional and Tertiary ICUs,” protocol no. 00002156, November 25, 2020, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa), and by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania (“Association of ICU Capacity Strain and Mortality in a Resource-Limited Setting,” protocol no. 824688, July 29, 2020, Philadelphia, PA). National South Africa COVID-19 data are licensed for public use through a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.24,25

Results

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 and e-Table 2 report study patient characteristics by cohort. Three thousand two hundred twenty-one patients were admitted to the ICU during the prepandemic period and 2,539 patients were admitted to the ICU during the pandemic period (n = 375 [14.8%] with COVID-19 and n = 2,164 [85.2%] without COVID-19). The prepandemic and pandemic non-COVID-19 cohorts were similar. Compared with the non-COVID-19 cohorts, the pandemic COVID-19 cohort showed older age, a higher female proportion, higher rates of chronic cardiovascular disease and diabetes, higher FIO2 requirements but less invasive mechanical ventilation at ICU admission, lower ICU admission Quick Sequential/Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment scores, less extrapulmonary organ dysfunction, longer ICU length of stay, and higher observed ICU mortality.

TABLE 1 ].

Characteristics of Patients Without and With COVID-19 Admitted to the ICU

| Cohort |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Prepandemic Non-COVID-19 | Pandemic Non-COVID-19 | Pandemic COVID-19 |

|

| |||

| Cohort period | 1/1/2017–3/4/2020 | 3/4/2020–6/30/2022 | 3/4/2020–6/30/2022 |

| ICU patients, No. | 3,221 | 2,164 | 375 |

| Age, y | 40.7 ± 16.1 | 40.2 ± 15.6 | 49.2 ± 14.1 |

| Male sex | 1,838 (57.1) | 1,253 (57.9) | 170 (45.3) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 2,791 (88.8) | 1,985 (91.6) | 283 (82.6) |

| Asian/Indian | 173 (5.5) | 85 (4.1) | 44 (12.7) |

| White | 131 (4.2) | 72 (3.5) | 12 (3.5) |

| Mixed | 48 (1.5) | 17 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) |

| Primary diagnosis at ICU admission | |||

| Infection | 632 (21.8) | 304 (15.6) | 302 (82.5) |

| Trauma | 1,031 (35.5) | 723 (37.0) | 20 (5.5) |

| Other | 1,241 (42.7) | 928 (47.5) | 44 (12.0) |

| Admission mechanical ventilation | 2,150 (66.8) | 1,468 (67.8) | 109 (29.1) |

| Admission mechanical ventilation among nonpostoperative patients | 396 (61.8) | 269 (58.2) | 75 (24.9) |

| Admission noninvasive ventilation | 82 (2.6) | 31 (1.4) | 123 (32.8) |

| Admission Fio2, % | 56 ± 31 | 53 ± 29 | 80 ± 28 |

| Quick Sequential/Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment score | |||

| 0–1 | 2,205 (69.9) | 1,393 (72.3) | 251 (76.1) |

| 2 | 798 (26.3) | 446 (23.2) | 73 (22.1) |

| 3 | 152 (4.8) | 87 (4.5) | 6 (1.8) |

| Serum lactate, mM | 4.2 ± 4.2 | 3.9 ± 3.7 | 2.7 ± 3.2 |

| ICU mortality | 596 (18.5) | 413 (19.1) | 205 (54.7) |

| ICU length of stay, calendar days | 4 (2–7) | 4 (3–7) | 6 (4–11) |

Data are presented as No. (%), mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. Percentages are reported among complete cases.

Capacity Strain

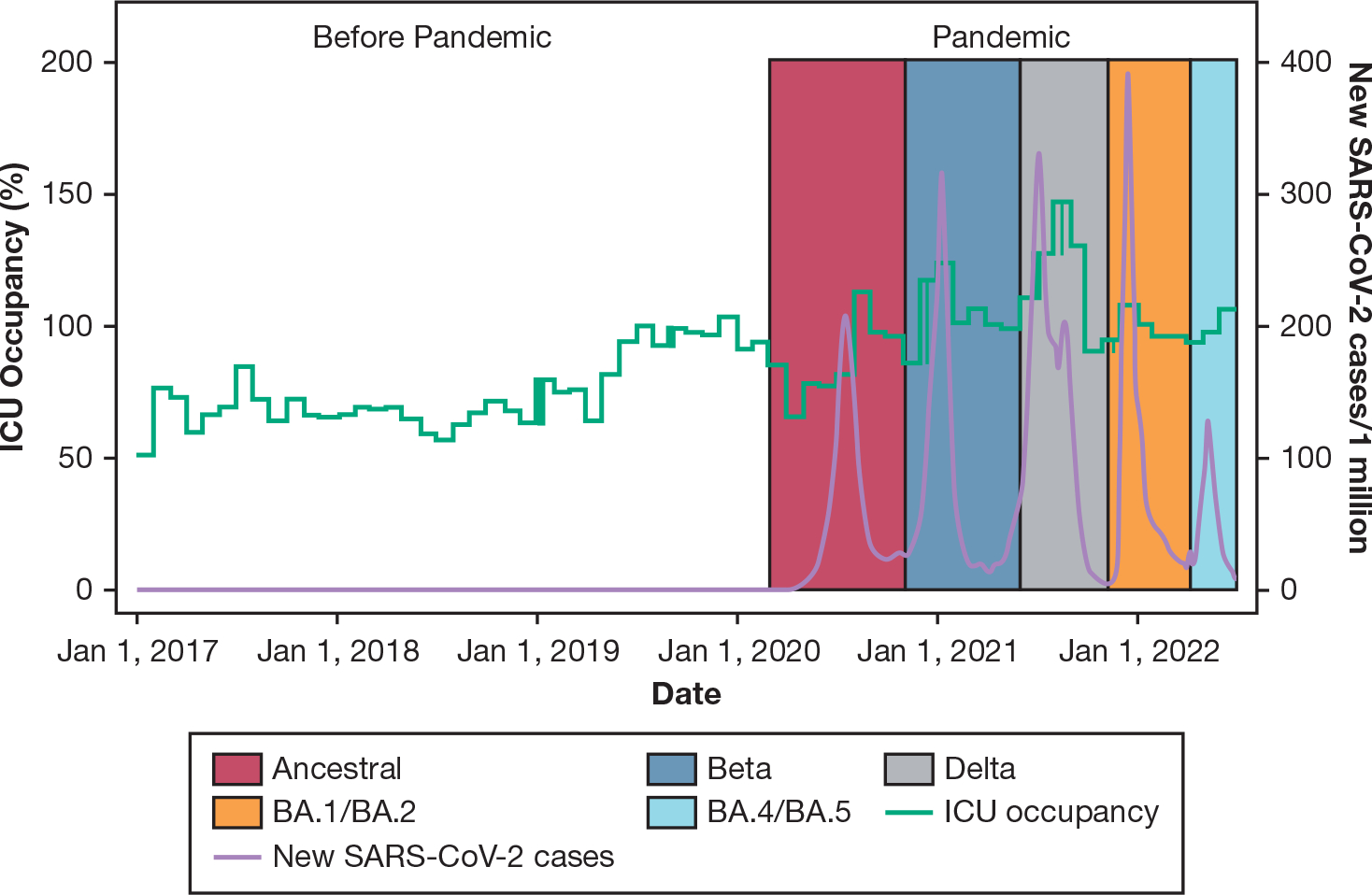

Figure 1 plots national SARS-CoV-2 incident cases and ICU occupancy spanning the prepandemic period and five South African pandemic surges. e-Table 3 reports ICU capacity strain metrics in the prepandemic and pandemic periods as recorded at the time of each study patient’s ICU admission, and e-Table 4 reports the same by pandemic period based on dominant SARS-CoV-2 viral variant. Compared with the prepandemic period, the study hospitals and patients admitted during the pandemic period experienced higher observed ICU occupancy (median, 100.0% [interquartile range, 80.0%–122.2%] of prepandemic ICU capacity). A median of 100% occupancy indicates that at the time of 50% of ICU admissions during the pandemic, ICU surge beds beyond prepandemic ICU capacity were in use. ICU occupancy was highest during the Beta variant (median, 115.9% [interquartile range (IQR), 90.9%–144.4%] of prepandemic ICU capacity) and Delta variant (median 131.8% [IQR, 106.7%–150.6%] of prepandemic ICU capacity) surges (e-Table 4).

Figure 1 –

Graph showing ICU occupancy and SARS-CoV-2 cases and variant surges. ICU occupancy (green line) at the time of study patient ICU admissions and standardized to prepandemic ICU capacity and national SARS-CoV-2 incident cases (purple line) are plotted spanning the prepandemic period and across five pandemic surges with dominant SARS-CoV-2 viral variants depicted by shaded areas. Compared with the prepandemic period, the study hospitals and patients admitted during the pandemic period experienced higher ICU occupancy (median, 100.0% [interquartile range (IQR), 80.0%–122.2%] of prepandemic ICU capacity). A median of 100% occupancy indicates that at the time of 50% of ICU admissions during the pandemic, ICU surge beds beyond prepandemic ICU capacity were in use. ICU occupancy was highest during the Beta variant (median, 115.9% [IQR, 90.9%–144.4%] of prepandemic ICU capacity) and Delta variant (median, 131.8% [IQR, 106.7%–150.6%] of prepandemic ICU capacity) surges.

ICU Mortality by Peripandemic Cohort

Table 2 reports the results of ICU mortality modeling among non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 ICU admissions by peripandemic cohort. Thirty-two patients (0.06%) were excluded because of missing covariate data. In the primary model (n = 5,732) adjusted for patient-level covariates, compared with the prepandemic non-COVID-19 cohort, the pandemic non-COVID-19 cohort showed similar odds of ICU mortality (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.25; P = .50), whereas the pandemic COVID-19 cohort showed significantly increased odds of ICU mortality (OR, 3.91; 95% CI, 3.03–5.05; P < .0005). The corresponding predicted probability of ICU mortality was 18.8% (95% CI, 17.4%–20.2%) for the prepandemic non-COVID-19 cohort and 19.7% (95% CI, 17.8%–21.5%) for the pandemic non-COVID-19 cohort, but was 46.1% (95% CI, 40.6%–51.6%) for the pandemic COVID-19 cohort. Based on power estimations, the null result for the pandemic non-COVID-19 cohort may miss small but statistically significant and potentially important differences compared with the prepandemic non-COVID-19 cohort.

TABLE 2 ].

ICU Mortality Among Patients Admitted to the ICU Without and With COVID-19 by Peripandemic Cohort

| ICU Mortality, OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Prepandemic Non-COVID-19 Cohort | Pandemic Non-COVID-19 Cohort | Pandemic COVID-19 Cohort |

|

| |||

| Unadjusted | Reference | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | 5.31 (4.25–6.63) |

| P value | .59 | < .0005 | |

| Adjusted for patient-level covariates (primary analysis)a | Reference | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 3.91 (3.03–5.05) |

| P value | .50 | < .0005 | |

| Adjusted for above plus ICU capacity strainb | Reference | 0.94 (0.77–1.14) | 3.30 (2.38–4.58) |

| P value | .51 | < .0005 | |

| Adjusted for above, restricted to nontraumac | Reference | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 3.36 (2.35–4.80) |

| P value | .34 | < .0005 | |

| Predicted Probability of ICU Mortality, % (95% CI) | |||

| Unadjusted | 18.5 (17.2–19.8) | 19.1 (17.4–20.7) | 54.7 (49.6–59.7) |

| Adjusted for patient-level covariates (primary analysis)a | 18.8 (17.4–20.2) | 19.7 (17.8–21.5) | 46.1 (40.6–51.6) |

| Adjusted for above plus ICU capacity strainb | 19.7 (18.0–21.4) | 18.7 (16.8–20.6) | 43.3 (36.9–50.0) |

| Adjusted for above, restricted to nontraumac | 21.4 (19.3–23.6) | 19.7 (17.4–21.9) | 46.3 (39.3–53.2) |

Patient-level covariates: age, sex, HIV status, chronic cardiovascular disease, diabetes, medical vs surgical status, study hospital, and country-level fully vaccinated individuals.

ICU capacity strain covariates: hospital-specific ICU referrals, ICU turnover, ICU occupancy, ICU acuity, and country 7-day rolling mean incident SARS-CoV-2 cases/1 million residents.

Same adjustment strategy, but without medical vs surgical status.

Among patient-level covariates, only age (OR, 1.03 per 1-year increase; 95% CI, 1.02–1.03; P < .0005) was associated with increased in-ICU mortality, whereas male sex (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.88–1.15; P = .94), HIV-positive status (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.92–1.29; P = .33), chronic cardiovascular disease (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.76–1.17; P = .61), and diabetes (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.71–1.10; P = .26) were not, although modeling was not designed for these outcomes.

These ICU mortality results persisted in sensitivity analyses when adjusting for capacity strain (n = 5,732) and when restricting to nontrauma patients (n = 3,960) (Table 2). e-Tables 5 and 6 and e-Figure 1 report ICU mortality among non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 ICU admissions by pandemic surge period. In these secondary, nonpowered analyses, patients with COVID-19 during the Beta and Delta variant surges seem to have higher point estimate ORs for ICU mortality compared with the ancestral surge.

ICU Mortality by ICU Occupancy

ICU occupancy was not associated with ICU mortality in either the COVID-19 cohort (OR, 1.05 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.96–1.14; P = .27; n = 372) or the non-COVID-19 cohort pooled across prepandemic and pandemic periods (OR, 1.01 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.98–1.03; P = .52; n = 5,360), adjusting for patient-level covariates (second coprimary analysis). Figure 2 and e-Table 7 report predicted ICU mortality by ICU occupancy decile with differences between the non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 cohorts (mean, 18.6% vs 52.5% ICU mortality across deciles, respectively), but no apparent differences within each cohort. Specifically, the non-COVID-19 cohort showed a range of ICU mortality from 15.6% to 20.3% across ICU occupancy deciles (4.7% range, greater than the estimated detectable mortality effect difference of 2.6%), and the COVID-19 cohort showed a range of ICU mortality from 40.1% to 64.8% across ICU occupancy deciles (24.7% range, greater than estimated detectable mortality effect difference of 9.2%), with no pattern across deciles. With a much smaller cohort population overall and especially per ICU occupancy decile, the pandemic COVID-19 cohort showed less precise estimates with wider CIs; the overlapping CIs by ICU occupancy decile are consistent with the null finding when treating ICU occupancy as a continuous variable.

Figure 2 –

Graph showing predicted ICU mortality among patients without and with COVID-19 by ICU occupancy. ICU occupancy was not associated with ICU mortality in either the COVID-19 cohort (OR, 1.05 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.96–1.14; P = .27) or the non-COVID-19 cohort pooled across prepandemic and pandemic periods (OR, 1.01 per 10% change in ICU occupancy; 95% CI, 0.98–1.03; P = .52), adjusting for patient-level covariates. The figure reports predicted ICU mortality by ICU occupancy decile (with decile 1 being lowest occupancy and decile 10 being highest occupancy) with differences between the non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 cohorts, but no apparent differences within each cohort.

Discussion

Adaptation and resiliency are challenged during public health emergencies as hospitals try to optimize outcomes for both primarily affected and bystander patients. These operational phenomena are understudied and especially so in resource-limited settings. This two-hospital retrospective cohort study in the South African public health system, leveraging access to local prepandemic comparator patients, sought to assess ICU outcomes as a proxy for critical care resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic with primary findings that (1) patients without COVID-19 before and during the pandemic showed comparable outcomes; and (2) ICU occupancy, one measure of capacity strain, although increased during the pandemic, was not associated with ICU mortality for either patients with or without COVID-19. Together, these suggest a degree of critical care resiliency—the ability to continue to deliver high-quality care to all and specifically patients not primarily affected (ie, uninfected bystander patients), despite the presence of a surge event—which may exceed that being reported in better-resourced settings.7–9 Although in many important ways chronically resource-limited hospitals and the patients they serve may be impacted more by pandemic-related surges, in other ways, such as demonstrated herein, these hospitals may display greater resiliency perhaps owing to more longitudinal experience with scarce resource allocation and critical care delivery under adverse circumstances.

A number of reports have described changes to the population of patients without COVID-19 who were hospitalized or admitted to ICUs during the pandemic as compared with patients admitted before the pandemic.7,9,32 The results of this study show broadly similar patients without COVID-19 before and during the pandemic in terms of patient-level characteristics and no difference in ICU mortality in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, despite higher ICU capacity strain during the pandemic. This may reflect the rigorous approach to ICU gatekeeping that occurs in the study hospitals, similar to many resource-limited settings, which strive to adhere strictly to triage guidelines (in this case, the Society of Critical Care Medicine ICU Triage Priority23) that seek to limit ICU admission to patients who are most likely to benefit. For example, the study hospitals historically admit approximately 50% of patients referred for ICU care, a far lower proportion than in many higher-resourced settings.18 In the present study, patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU showed lower Quick Sequential/Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment scores than patients admitted to the ICU without COVID-19, reflecting both the dominant single-organ (respiratory) failure picture of early severe COVID-19, as well as potentially the intentional exclusion of patients with COVID-19 with higher acuity reflecting early multisystem organ failure for whom prognosis is poor. Those gatekeeping practices may have allowed the ICU teams to better regulate and maintain a consistent ICU population without COVID-19 and consistent non-COVID-19 ICU outcomes despite dynamic pandemic circumstances.

A few additional specific observations can be made about the composition of the cohort with COVID-19, which displayed significantly worse outcomes compared with the prepandemic and pandemic cohorts without COVID-19. Although in many pandemic reports male sex is a risk factor for severe COVID-19,2,33–35 in this sample, the COVID-19 cohort showed a notably lower proportion of male patients than the non-COVID-19 cohorts, which is likely an artifact of the particularly high male predominance of the study ICUs’ heavy trauma population (35%–37% of all patients without COVID-19 admitted to the ICU).18,20,22 Relatedly, among the COVID-19 cohort, 82.5% of patients showed a primary ICU admitting diagnosis of infection, with only 5.5% admitted for trauma, indicating relatively few incidental cases of COVID-19 or patients admitted “with rather than for” COVID-19. Prior studies have shown conflicting results regarding whether HIV is an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease and in-hospital mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19.14,36,37 Of note, in our adjusted models, HIV status was not associated significantly with in-ICU mortality, and HIV prevalence was balanced between the study cohorts. Although this was not a prespecified or designed analysis, these findings could suggest that although HIV status may influence COVID-19 disease severity, as soon as patients are sick enough to warrant ICU admission, HIV status may no longer be a risk factor for mortality.

Perhaps surprisingly, patients with COVID-19 showed lower rates of invasive mechanical ventilation at ICU admission than the patients without COVID-19 (29.1% vs 66.8% and 67.8%). This may reflect one of a few phenomena. First, patients with COVID-19 frequently have a prolonged clinical course with high, but noninvasive, methods of respiratory support (ie, noninvasive ventilation or high-flow nasal cannula) before either progressing to requiring invasive mechanical ventilation or improving; the patient characteristics reported herein are at ICU admission. Also the non-COVID-19 cohorts include a high proportion of still-intubated postoperative patients, reflecting the study ICUs’ predominant surgical population (and a low proportion of postoperative patients among the COVID-19 cohort), and as above, a low rate of incidental COVID-19 was found.18,20,22 Finally, noninvasive ventilation was used frequently for patients with COVID-19 and sparsely for patients without COVID-19 (32.8% vs 2.6% and 1.4%) at the study hospitals. Unsurprisingly, patients with COVID-19 showed far higher Fio2 requirements at ICU admission (mean, 80% vs 53%–56%). Patients with COVID-19 were, at least at the time of ICU admission, dominated by single-organ (respiratory) failure also reflected in the lower Quick Sequential/Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment scores and lower serum lactate levels. As is now widely reported, patients with COVID-19 experienced longer observed ICU lengths of stay than patients without COVID-19.38

Notable strengths of our study include: the availability of high-fidelity, local, prepandemic comparator patients to allow for hospital resiliency assessments; data across five SARS-CoV-2 viral variant periods; and incorporation of local and national ICU capacity strain metrics as both exposure and adjustment variables. The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of important limitations. First, the ICU database is limited to data at the time of ICU referral and ICU admission and selected end-ICU outcomes. The database does not contain information on longitudinal physiological features and interventions during the ICU stay (including COVID-19-directed therapy) or post-ICU hospital course and outcomes including long-term outcomes. The results of this study comment on critical care resiliency, a component of, but not necessarily representative of, hospital-wide resiliency. Additionally, the ICU database is assembled as part of routine clinical care by the ICU teams. This has the benefit of surmounting challenging retrospective data collection from analog records or prospective data collection in a resource-limited setting, but it has the caveats of entry error rates and absence of information that occur in a busy clinical setting, including underdetection of COVID-19. Second, when studying periods dominated by different SARS-CoV-2 viral variants, we relied on publicly available national sequencing data26 because individual study patients were not sequenced. We also did not have data on patient-level vaccination status (instead using national cumulative population vaccination status) nor on preexisting immunity from prior infection,39 which confounds the by-period analysis of COVID-19 ICU outcomes. Third, this was a two-hospital, single-country study, and although the addition of studies in the resource-limited setting of the South African public health system is helpful, resource-limited settings are heterogeneous, including those even more resource limited without any critical care available.13,14 Therefore, these results should be viewed as additive to the broader global literature base, not automatically generalizable to other settings. Finally, for results that rely on a null finding, such as comparing ICU mortality between prepandemic and pandemic cohorts without COVID-19, the available sample size and power may miss small but statistically significant and potentially important differences.

Interpretation

Patients without COVID-19 admitted to the ICU before and during the pandemic broadly were similar in clinical characteristics and outcomes, suggesting critical care resiliency, whereas patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU showed important clinical differences and significantly higher mortality.

Supplementary Material

Take-home Points.

Study Question:

How did critical care outcomes compare across three peripandemic study cohorts (prepandemic non-COVID-19, pandemic non-COVID-19, and pandemic COVID-19) and across degrees of capacity strain in a resource-limited setting?

Results:

Patients without COVID-19 before and during the pandemic showed comparable outcomes, whereas patients with COVID-19 showed significantly increased odds of ICU mortality. ICU occupancy, although increased during the pandemic, was not associated with ICU mortality for patients either without or with COVID-19.

Interpretation:

These results suggest a degree of critical care resiliency in a resource-limited setting that may exceed that being reported in better-resourced settings, perhaps owing to more longitudinal experience with scarce resource allocation and critical care delivery under adverse circumstances.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

G. L. A. is supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant K23HL161353]) and the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine Thomas B. McCabe and Jeannette E. Laws McCabe Fund.

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

The authors have reported to CHEST Critical Care the following: G. L. A. reports payments for authoring chapters for UpToDate and for expert witness consulting, both relating to COVID-19. None declared (S. M. S., J. I., R. H., A. R., C. E., R. D. W., M. T. D. S.).

Role of sponsors:

The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

South Africa ICU Capacity Strain Study Group collaborators:

George L. Anesi, MD, MSCE, MBE, Nikki L. Allorto, MBChB, Leesa A. Bishop, MBChB, Carel Cairns, MBChB, Creaghan Eddey, MBBCh(Wits), DA(SA), DipPEC(SA), Robyn Hyman, MBChB(Pret), Jonathan Invernizzi, MBBCh, FCA, MMed, Sumayyah Khan, MBChB(UKZN), DA(SA), Rachel Kohn, MD, MSCE, Arisha Ramkillawan, MBChB, FCP(SA), Certificate Critical Care(SA)(phys), Stella M. Savarimuthu, MD, Michelle T.D. Smith, MBChB, MMed, FCS(SA), PhD, Gary E. Weissman, MD, MSHP, Doug P. K. Wilson, MBChB, FCP(SA), PhD, and Robert D. Wise, MBChB, FCA, Cert Crit Care, MMed.

Other contributions:

The authors thank the other members and collaborators of the South Africa ICU Capacity Strain Study Group, a collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine (Philadelphia, PA) and the University of KwaZulu-Natal School of Clinical Medicine (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa); and Our World in Data and the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 Data Repository for their efforts during the pandemic and their willingness to provide their data for public use.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- IQR

interquartile range

Footnotes

Abstracts of this work were presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, San Francisco, CA, May 17, 2022, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine Critical Care Congress, San Francisco, CA, January 21, 2023.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figure, and e-Tables are available online under “Supplementary Data.”

Contributor Information

George L. Anesi, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Stella M. Savarimuthu, Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Jonathan Invernizzi, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Harry Gwala Regional Hospital, Greys Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg.

Robyn Hyman, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Harry Gwala Regional Hospital, Greys Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg.

Arisha Ramkillawan, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Greys Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg.

Creaghan Eddey, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Greys Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg.

Robert D. Wise, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, School of Clinical Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa; Faculty Medicine and Pharmacy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium; Intensive Care Department, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University Trust Hospitals, Oxford, England..

Michelle T. D. Smith, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Greys Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg; Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, School of Clinical Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

References

- 1.Anderson JE, Aase K, Bal R, et al. Multilevel influences on resilient healthcare in six countries: an international comparative study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e039158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anesi GL, Jablonski J, Harhay MO, et al. Characteristics, outcomes, and trends of patients with COVID-19-related critical illness at a learning health system in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174: 613–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anesi GL, Lynch Y, Evans L. A Conceptual and adaptable approach to hospital preparedness for acute surge events due to emerging infectious diseases. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer D, Bishai D, Ravi SJ, et al. A checklist to improve health system resilience to infectious disease outbreaks and natural hazards. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott HC, Levy MM. Survival from severe coronavirus disease 2019: is it changing? Crit Care Med. 2021;49: 351–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churpek MM, Gupta S, Spicer AB, et al. Hospital-level variation in death for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204:403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French G, Hulse M, Nguyen D, et al. Impact of hospital strain on excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, July 2020-July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1613–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilcox ME, Rowan KM, Harrison DA, Doidge JC. Does unprecedented ICU capacity strain, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, impact patient outcome? Crit Care Med. 2022;50: e548–e556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zampieri FG, Bastos LSL, Soares M, Salluh JI, Bozza FA. The association of the COVID-19 pandemic and short-term outcomes of non-COVID-19 critically ill patients: an observational cohort study in Brazilian ICUs. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1440–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duclos A, Cordier Q, Polazzi S, et al. Excess mortality among non-COVID-19 surgical patients attributable to the exposure of French intensive and intermediate care units to the pandemic. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49: 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naidoo AV, Hodkinson P, Lai King L, Wallis LA. African authorship on African papers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e004612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covid-19 vaccine tracker: the global race to vaccinate. Financial Times Updated December 23, 2022. Accessed February 9, 2023. https://ig.ft.com/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker/?areas=gbr&areas=usa&areas=eue&areas=xaf&cumulative=1&doses=full&populationAdjusted=1

- 13.Bakamutumaho B, Lutwama JJ, Owor N, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and mortality of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 in Uganda, 2020–2021. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19:2100–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.African COVID-19 Critical Care Outcomes Study (ACCCOS) Investigators. Patient care and clinical outcomes for patients with COVID-19 infection admitted to African high-care or intensive care units (ACCCOS): a multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:1885–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslo C, Friedland R, Toubkin M, Laubscher A, Akaloo T, Kama B. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in South Africa during the COVID-19 Omicron wave compared with previous waves. JAMA. 2022;327:583–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anesi GL, Chowdhury M, Small DS, et al. Association of a novel index of hospital capacity strain with admission to intensive care units. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17: 1440–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anesi GL, Liu VX, Gabler NB, et al. Associations of intensive care unit capacity strain with disposition and outcomes of patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:1328–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anesi GL, Gabler NB, Allorto NL, et al. Intensive care unit capacity strain and outcomes of critical illness in a resource-limited setting: a 2-hospital study in South Africa. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35: 1104–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allorto NL, Wise RD. Development and evaluation of an integrated electronic data management system in a South African metropolitan critical care service. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2015;21:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop LA, Wilson DPK, Wise RD, Savarimuthu SM, Anesi GL. Prognostic value of the Quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score among critically ill medical and surgical patients with suspected infection in a resource-limited setting. Afr J Thorac Crit Care Med. 2021;27:145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn S, Wise R, Savarimuthu SM, Anesi GL. Association between pre-ICU hospital length of stay and ICU outcomes in a resource-limited setting. SAJCC. 2021;37(3):98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savarimuthu SM, Cairns C, Allorto NL, et al. qSOFA as a predictor of ICU outcomes in a resource-limited setting in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. SAJCC. 2020;36(2):92–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.COVID-19 dataset. Our World in Data; 2023. Updated June 2, 2023. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

- 25.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20: 533–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodcroft EB. CoVariants.org. CoVariants.org website. Accessed February 9, 2023. https://covariants.org [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadri SS, Sun J, Lawandi A, et al. Association between caseload surge and COVID-19 survival in 558 U.S. hospitals, March to August 2020. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1240–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravata DM, Perkins AJ, Myers LJ, et al. Association of intensive care unit patient load and demand with mortality rates in US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4: e2034266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anesi GL, Liu VX, Chowdhury M, et al. Association of ICU admission and outcomes in sepsis and acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:520–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ender PB. Stata package: University of California, Los Angeles Advanced Research Computing Statistical Methods and Data Analytics website. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/stata/ado/analysis/powerlog-hlp-htm [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adhikari N, Beane A, Devaprasad D, et al. Indian Registry of IntenSive care (IRIS). Impact of COVID-19 on non-COVID intensive care unit service utilization, case mix and outcomes: a registry-based analysis from India. Wellcome Open Res. 2021;6:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butt AA, Dargham SR, Chemaitelly H, et al. Severity of illness in persons infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant vs Beta variant in Qatar. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor CA, Patel K, Pham H, et al. Severity of disease among adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 before and during the period of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (Delta) predominance—COVID-NET, 14 states, January-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1513–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quaresima V, Scarpazza C, Sottini A, et al. Sex differences in a cohort of COVID-19 Italian patients hospitalized during the first and second pandemic waves. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertagnolio S, Thwin SS, Silva R, et al. Clinical features of, and risk factors for, severe or fatal COVID-19 among people living with HIV admitted to hospital: analysis of data from the WHO Global Clinical Platform of COVID-19. Lancet HIV. 2022:e486–e495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dzinamarira T, Murewanhema G, Chitungo I, et al. Risk of mortality in HIV-infected COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15:654–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins TL, Stark MM, Henson KN, Freeseman-Freeman L. Coronavirus disease 2019 ICU patients have higher-than-expected acute physiology and chronic health evaluation-adjusted mortality and length of stay than viral pneumonia ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e701–e706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun K, Tempia S, Kleynhans J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission, persistence of immunity, and estimates of Omicron’s impact in South African population cohorts. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(659): eab07081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.