Abstract

Heat stress poses a significant environmental challenge that profoundly impacts wheat productivity. It disrupts vital physiological processes such as photosynthesis, by impeding the functionality of the photosynthetic apparatus and compromising plasma membrane stability, thereby detrimentally affecting grain development in wheat. The scarcity of identified marker trait associations pertinent to thermotolerance presents a formidable obstacle in the development of marker-assisted selection strategies against heat stress. To address this, wheat accessions were systematically exposed to both normal and heat stress conditions and phenotypic data were collected on physiological traits including proline content, canopy temperature depression, cell membrane injury, photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate (at vegetative and reproductive stage and ‘stay-green’. Principal component analysis elucidated the most significant contributors being proline content, transpiration rate, and canopy temperature depression, which exhibited a synergistic relationship with grain yield. Remarkably, cluster analysis delineated the wheat accessions into four discrete groups based on physiological attributes. Moreover, to explore the relationship between physiological traits and DNA markers, 158 wheat accessions were genotyped with 186 SSRs. Allelic frequency and polymorphic information content value were found to be highest on genome A (4.94 and 0.688), chromosome 1A (5.00 and 0.712), and marker Xgwm44 (13.0 and 0.916). Population structure, principal coordinate analysis and cluster analysis also partitioned the wheat accessions into four subpopulations based on genotypic data, highlighting their genetic homogeneity. Population diversity and presence of linkage disequilibrium established the suitability of population for association mapping. Additionally, linkage disequilibrium decay was most pronounced within a 15–20 cM region on chromosome 1A. Association mapping revealed highly significant marker trait associations at Bonferroni correction P < 0.00027. Markers Xwmc418 (located on chromosome 3D) and Xgwm233 (chromosome 7A) demonstrated associations with transpiration rate, while marker Xgwm494 (chromosome 3A) exhibited an association with photosynthetic rates at both vegetative and reproductive stages under heat stress conditions. Additionally, markers Xwmc201 (chromosome 6A) and Xcfa2129 (chromosome 1A) displayed robust associations with canopy temperature depression, while markers Xbarc163 (chromosome 4B) and Xbarc49 (chromosome 5A) were strongly associated with cell membrane injury at both stages. Notably, marker Xbarc49 (chromosome 5A) exhibited a significant association with the 'stay-green' trait under heat stress conditions. These results offers the potential utility in marker-assisted selection, gene pyramiding and genomic selection models to predict performance of wheat accession under heat stress conditions.

Keywords: Association mapping, Linkage disequilibrium, Wheat, PCoA and cluster analysis

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Rising global warming instigate the changes in pattern of rainfall, disease incidence and vulnerable atmospheric temperature for crops1,2. Despite the advances in improved technology for agricultural crops, climatic changes jeopardize the genetic potential of crop productivity3–5. Increasing threats of high temperature restrict sustainable crop production6. Projections from global climate models portend an anticipated surge of 5.8 °C in average temperatures by the end of twenty-first century7. Wheat stands as a pivotal staple crop globally, contributing to 70% of caloric intake and 12–15% of protein consumption for humans8. However, heat stress instigates irreversible impairment to wheat crop development. Each degree Celcius increase in temperature above 32 °C during anthesis and grain filling reduces 1.0–4.2% grain yield in wheat1,9. In Pakistan, wheat planted between 20th October to 20th November and each day delay in sowing reduces 1.2% grain yield10. Nevertheless, approximately 20% of wheat cultivation adheres to the normal planting, with deviations attributed to delay harvesting of rice and cotton crops11,12. Late planting curtails the wheat crop life cycle by completing growing degree days earlier, thereby exacerbating heat stress conditions13–15. High temperatures intricately regulate photoperiodic and vernalization-sensitive genes, precipitating a reduction in grain filling duration and impeding the plant's capacity to harness available resources effectively16–18. Selection of desirable physiological traits associated with thermotolerance provides opportunities for crop improvement and genetic yield gain.

Heat stress exerts its influence on photosynthesis by impeding the functionality of photosystem-II and the electron transport chain mediated photosystem-I19,20. It also reduces the chlorophyll content and chloroplast integrity due to leaf senescence, thereby impeding the overall process of photosynthesis21–23. Cell membrane is composed of lipids and proteins, regulates enzymatic activity and ion transport. High temperature disrupts the hydrogen bonding between proteins and adjacent fatty acids, consequently perturbing membrane fluidity24,25. Additionally, leaf senescence hampers the synthesis of photosynthetic products, impeding their translocation into developing grains26–28.

Leaf senescence during the reproductive phase reduces green leaf area due to decreased chlorophyll and carotenoid content, which are essential for photosynthesis. High temperatures disrupt chloroplast integrity and accelerate leaf senescence, impairing photosynthesis in wheat. Therefore, stay-green during anthesis to physiological maturity assures the retention of chlorophyll content and maintains photosynthesis under adverse environmental conditions29–31.

Proline accumulation in wheat is regulated by proline dehydrogenase activity and Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase/reductase (P5CS)32. High temperatures increase P5CS activity and decrease proline dehydrogenase, leading to proline synthesis from glutamate under heat stress. At temperatures of 35–40 °C, proline content can increase by up to 200%, enhancing the defense mechanisms, photosynthetic efficiency, and yield of wheat seedlings33. Proline content accumulation also stabilizes the photosynthesis and antioxidant enzyme activity, and acts as osmo-protectant against heat stress conditions34.

Cooler canopy determines the stomatal conductance that maintains evapo-transpiration and photosynthesis in wheat35–37. These intricate cellular and physiological processes coupled with membrane fluidity dynamics determine wheat growth and development under heat stress conditions.

Selection for thermo-tolerance can be accomplished utilizing physio-morphic traits and molecular markers but lack of knowledge regarding genetic basis of thermo-tolerance. Earlier, genetic diversity among accessions was identified using physio-morphic traits but integration of molecular markers into the selection process holds the promise of enhanced efficiency, reliability, expedience, and robustness, while concurrently mitigating susceptibility to environmental variability. Among array of molecular markers, simple sequence repeats (SSR) markers stand out for their high polymorphism, co-dominance, and replicability throughout the entire genome38,39. Furthermore, SSR markers are widely favored in genetic mapping endeavors, as they yield more informative data compared to biallelic SNPs markers40,41. Utilization of SSR markers serves to augment marker density in specific genomic regions, thereby facilitating the construction of comprehensive genetic maps42–44.

Genome wide associations and linkage mapping/bi-parental mapping are methods to decipher genetic architecture underlying quantitative traits45,46. Association mapping is an alternative to quantitative trait loci (QTL mapping), serves to identify novel genes or loci leveraging diverse cultivars, landraces or elite lines. It aids in understanding the genetic basis of quantitative traits related to thermo-tolerance in wheat. Its advantages over bi-parental based mapping include broader genetic divergence among population and high resolution47–50. Association mapping investigatethe relationship among phenotypic variation and genetic polymorphism based on linkage disequilibrium. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) denotes the non-random alleles associations at different loci and its frequency subject to deviate by factors such as mating system, recombination rate, genetic drift and population dynamics. Elucidating LD pattern improves the accuracy and precision of association mapping endeavors51–54. However, a notable challenge in association mapping is false positive associations that ensue from family relatedness. Mixed Linear Model (MLM) has been devised to effectively eliminate the false positives in association mapping42,55,56.

Previous studies predominantly emphasized agronomic attributes viz., plant height, tillers per plant, leaf area, grains per spike, thousand grain weight under invariable environmental conditions11,45,57 but identification of marker trait associations (MTAs) under heat stress environment for physiological attributes is limited. Scarcity of knowledge regarding genomic regions linked to thermo-tolerant traits served as the impetus for this research endeavor. Therefore, current study was meticulously designed to unveil the genomic regions controlling physio-morphic traits via association mapping leveraging a panel of 186 SSR markers. Such insights not only facilitate breeders in delineating marker-assisted selection strategies under heat stress conditions but also lay the groundwork for a deeper comprehension of the genetic architecture governing thermo-tolerance in wheat.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A diverse panel of 158 wheat accessions from Pakistan and CIMMYT (Mexico), encompassing entries from 23rd and 24th SAWYT (Semi-arid wheat yield trial) as explained in Supplementary Material Table 1.

Soil composition

Prior to sowing, basic soil analysis were performed for electrical conductivity, pH58, soil moisture59, soil texture classification60, potassium level61, extractable phosphorus content62 and total nitrogen content63. Soil texture was determined to be sandy clay, EC 0.19 dS m−1, pH 7.65, moisture content 9.14% and organic carbon in soil 0.52% showing deficiency i.e. < 1% organic matter. Nitrogen content was measured 0.41 mg g−1 in soil whereas extractable potassium, Olsen phosphorus and ammonium nitrates in soil were 82.8, 1.8 and 0.64 mg kg−1, respectively. Therefore, fertilizers were applied comprising N@118 kg/ha and P@ 58 kg/ha. Agronomic practices such as weeding, hoeing and irrigation were diligently executed in accordance with the specific requirements of wheat cultivation.

Growing conditions and experimental layout

Wheat accessions were systematically planted using triplicated Augmented Complete Block Design along with check (control) cultivars namely Pakistan-13 and Gold-16 with thirteen blocks (12 accessions with 2 checks in each block) at the shelter house of PMAS-AAUR (33.117283°N, 73.010958°E) Pakistan. Each accession was planted in a single 3-m row and checks were replicated in each block. Planting was carried out during the 1st week of November coinciding with the wheat growing season (Rabi season) spanning 2018–2019, 2019–2020 and 2020–2021. Temperature in the shelter house was maintained 21 ± 0.8 °C day/15 ± 0.7 °C night (controlled set) and 26 ± 1.2 °C day/18 ± 0.9 °C night day/night (heat treated set) with relative humidity maintained 70–75% for 7 days at tillers stage Zadoks scale 3964. Subsequent data collection on physiological attributes occurred after a recovery period of 4–5 days. At the anthesis stage, as per Zadoks scale 69, temperature conditions were adjusted to 26 °C during the day and 18 °C at night for the controlled set, while the heat-treated set experienced elevated temperatures of 32 °C during the day and 20 °C at night, with a relative humidity range of 70–75% over another 7-day interval. Data recording on physiological attributes ensued following a similar recovery period of 4–5 days.

Data recording

Photosynthetic rate and transpiration rate

Photosynthetic rate and transpiration rate was measured spanning from 10:00 am to 12:00 pm utilizing an advanced infrared gas analyzer (IRGA), LCA-4, ADC, Joddeson, UK. Measurements conditions were constant at CO2 360 mmol mol−1 and PAR-1600 mmol m−2 s−1 65.

Proline content

Proline content were quantified involving extraction of 0.5 g leaf ground suspended in 3% sulphosalicyclic acid solution subsequently centrifuged for 10 min @ 10,000 rpm. Supernatant (4 mL) was reacted with glacial acetic acid (4 mL) and boiling at 100 °C in water bath for 1 h and 8 mL toluene was added after cool down on ice for 30 min and absorbance was estimated on spectrophotometer at 520 nm66. Proline content were determined using formula

Cell membrane injury

Cell membrane injury was recorded from flag leaf samples. Two distinct sets were washed with ddH2O and subsequently filled with 4 mLddH2O water. One set was exposed to heat stress at 40 °C for 1 h whereas the control was treated at room temperature (25 °C). After heat treatment, additional 16 mL ddH2O was added in heat treated set and incubated 24 h at 10 °C. Initial electrolyte leakage (T1 and C1) was estimated with electric conductivity meter. These sets were autoclaved for 10 min and second electrolyte leakage (T2 and C2) was measured67. Cell membrane injury was calculated using the CMI (%) formula given below:

Canopy temperature depresssion

Canopy temperature was recorded within the time frame of 10:00am to 12:00 pm with infrared thermometer68. Canopy temperature depression (CTD) involved subtracting the air temperature (Ta) from canopy temperature (Tc) as outlined by formula provided below.

Stay green

In order to collect data for the "stay-green", green leaf area and spikes were scored visually (0–9 scale) at intervals of 3–4 days from anthesis to maturity using the LAUG approach69 and calculated using the formula below

where t(i + 1)—ti = Time between two consecutive reading in days and Yi = Difference of green spike and flag leaf at time.

Grain yield

Grain yield was calculated from each plant and computed the average in grams.

Genotyping and marker analysis

DNA extraction was performed in 96 wells plate70. A set of 186 SSR primers was randomly selected for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) covering all 21 wheat chromosomes (Supplementary Material Table 2). M13 tail (CACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC) was synthesized at the 5′ end of the forward primer. Four fluorescent dyes (PET, NED, HEX and FAM) were used for PCR with different primers and PCR products were analyzed on DNA analyzer ABI-373071, a sophisticated instrument renowned for its precision and reliability in DNA fragment analysis, facilitating the elucidation of genetic information encoded within the amplified DNA sequences.

Statistical analysis

Physiological trait data were analyzed utilizing PROC MIXED, employing a fixed effect for entries and a random effect for blocks. Best linear unbiased predictions (BLUPs) were then computed to derive genotypic means while mitigating environmental variability, employing the SAS software package72. Descriptive statistics and relative performance metrics were computed for both physiological traits and grain yield73. Additionally, heritability, a crucial parameter indicative of the genetic control of traits and provides the valuable insights into the inheritance patterns of the observed traits was estimated using a standard formula.

where G represents the variance of genotype variance, e is residual variance and nE is number of environments.

Principal component analysis for physiological traits was performed, extracting Eigen values, variance proportions and loading factors using the R-4.0.3 software package, facilitated by Factoextra, FactoMiner and ggplot2 libraries (accessed on 15 February 2023). Additionally, correlation analysis was performed and diagram was constructed using corrplot package. Cluster analysis was performed and dendrogram was drawn employing ggplots package in R-4.0.3, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the interrelationships and clustering patterns among the physiological attributes.

For genotypic data, fragment analysis and allele calling was computed on GeneMapper software v3.774. Allelic frequency and polymorphism information content (PIC) were calculated for determination of genetic diversity75. Genotypic data were analyzed by admixtured model in STRUCTURE76. For genetic dissimilarity among individuals, 1–12 clusters were presumed with 5 independent runs. For each run, simulation length 100,000 replications and Burn-in length 50,000 cycles were adopted to estimate lnPr(X|K) peak in the range of 1–12 subpopulations. DeltaK value based on the Evano criterion was performed using the web-based program STRUCTURE HARVESTER v0.6.9377. PCoA was performed in Statistica78 whereas cluster analysis employing the UPGMA (Unweighted Pair-Group Method with Arithmetic mean) with 1000 permutations using Jacords method executed in software DARwin 6.079 and genetic dissimilarity matrix was employed to construct dendrogram by FigTree v1.3.180. Linkage disequilibrium was assessed at 95% confidence interval for rare allele frequency and significant (P-value < 0.001) correlations (r2 > 0.1) for each pair of loci were considered in software TASSEL V4.3.181. Extent of linkage disequilibrium (P < 0.01 with r2 > 0.1) for each genome and chromosome was estimated82. MTAs were identified using Mixed Linear Model and convergence criteria were set at highly significant P ≤ 0.001 value in default run with 1000 number of iterations in TASSEL V4.3.183. Bonferroni correction was subsequently applied by dividing P ≤ 0.05 by the number of SSR marker to establish the more stringent threshold. Bonferroni correction was subsequently applied by dividing P ≤ 0.05 by the number of SSR marker to establish the more stringent threshold.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

"This study complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation of Pakistan. The plant material was obtained from Pakistan and CIMMYT (Mexico). No special permissions were necessary to collect samples. Otherwise, the plant materials used and collected in the study comply with Pakistani guidelines and legislation".

Results

Phenotypic data analysis

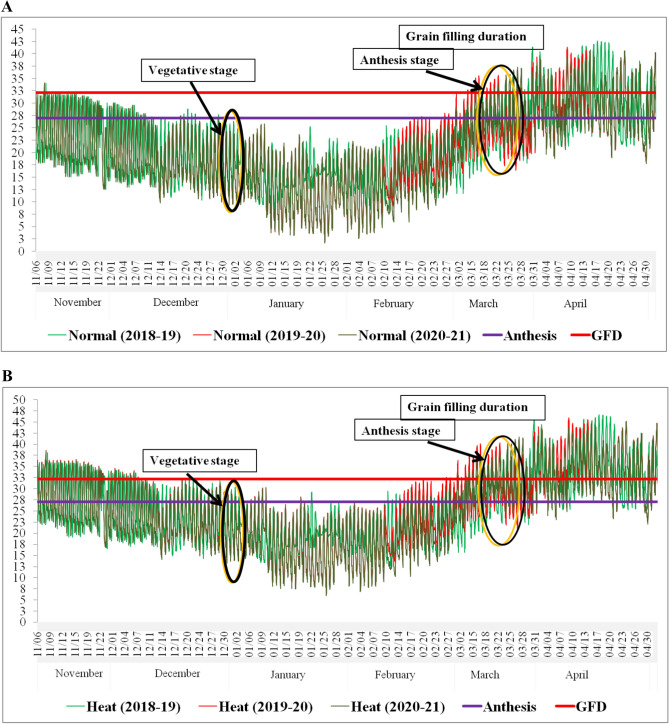

Normal wheat planting faced optimum temperature at tillering (20 ± 1.2 °C) and anthesis stage (25 ± 1.5 °C). However, wheat crop was exposed to heat stress at tillering (24 ± 0.8 °C) and anthesis (32 ± 1.5 °C) as displayed in Fig. 1A,B. In the present study significant phenotypic variation was observed among the 158 wheat accessions under both conditions (Table 1). Relative performance of photosynthetic rate at vegetative stage indicated 42.5% reduction under heat stress than normal conditions. Photosynthetic rate at reproductive stage was reduced by 47.9% under heat stress conditions. Transpiration rate was reduced by 37.8% and 58.6% at the vegetative and reproductive stage, respectively. Proline content exhibited an increase of 14.4% and 21.8% at the vegetative and reproductive stages under heat stress, respectively. Mean cell membrane injury was recorded at 29.1% (vegetative) and 19.7% (reproductive), canopy temperature depression at 11.1 °C (vegetative) and 9.0 °C (reproductive), leaf angle at 29.6°, and 'stay green' at 47.1 under heat stress conditions. Broad-sense heritability ranged from 0.86 to 0.99 under normal conditions and from 0.55 to 0.99 under heat stress, as indicated in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

(A) Temperature data during wheat life cycle 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 under normal conditions.

Source: Department of Environmental Science, PMAS-AAUR. (B) Temperature data during wheat life cycle 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 under heat stress conditions. Source: Department of Environmental Science, PMAS-AAUR.

Table 1.

Phenotypic performance under normal and heat stress conditions.

| Traits | Normal | H2 | Heat stress | H2 | RP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | S.E | Mean | Range | S.E | ||||

| EV | 0.37 | 0.22–0.53 | 0.0051 | 0.94 | 0.23 | 0.13–0.44 | 0.0041 | 0.92 | 37.84 |

| ER | 0.29 | 0.16–0.48 | 0.0056 | 0.87 | 0.12 | 0.07–0.29 | 0.0054 | 0.84 | 58.62 |

| PnV | 20.38 | 14.68–29.73 | 0.2404 | 0.99 | 11.72 | 8.68–19.07 | 0.1446 | 0.86 | 42.49 |

| PnR | 16.86 | 12.82–22.25 | 0.1834 | 0.86 | 8.78 | 5.76–16.37 | 0.1498 | 0.81 | 47.92 |

| ProV | 0.439 | 0.232–0.607 | 0.0071 | 0.95 | 0.513 | 0.36–0.723 | 0.0065 | 0.92 | 14.42 |

| ProR | 0.510 | 0.339–0.683 | 0.0059 | 0.94 | 0.652 | 0.475–0.87 | 0.0069 | 0.90 | 21.78 |

| GY | 7.94 | 5.89–10.2 | 0.361 | 0.85 | 5.11 | 3.42–8.76 | 0.341 | 0.89 | 35.64 |

| CMIV | 29.07 | 14.37–45.05 | 0.6076 | 0.79 | |||||

| CMIR | 19.74 | 11.02–30.79 | 0.3613 | 0.62 | |||||

| CTDV | 11.09 | 8.42–13.01 | 0.0660 | 0.90 | |||||

| CTDR | 9.00 | 6.93–11.08 | 0.0763 | 0.55 | |||||

| LA | 29.56 | 8.58–43.00 | 0.6061 | 0.99 | |||||

| SG | 47.10 | 16.61–67.54 | 1.0586 | 0.68 | |||||

EV Transpiration rate at vegetative stage, ER Transpiration rate at reproductive stage, PnV Photosynthetic rate at vegetative stage, PnR Photosynthetic rate at reproductive stage, ProV Proline content at vegetative stage, ProR Proline content at reproductive stage, GY Grain yield per plant, CMIV Cell membrane injury at vegetative stage, CMIR Cell membrane injury at reproductive stage, CTDV Canopy temperature depression at vegetative stage, CTDR Canopy temperature depression at reproductive stage, LA Leaf angle, SG Stay green, SE Standard error, H2: Broad sense heritability.

Genetic variability using multivariate analysis

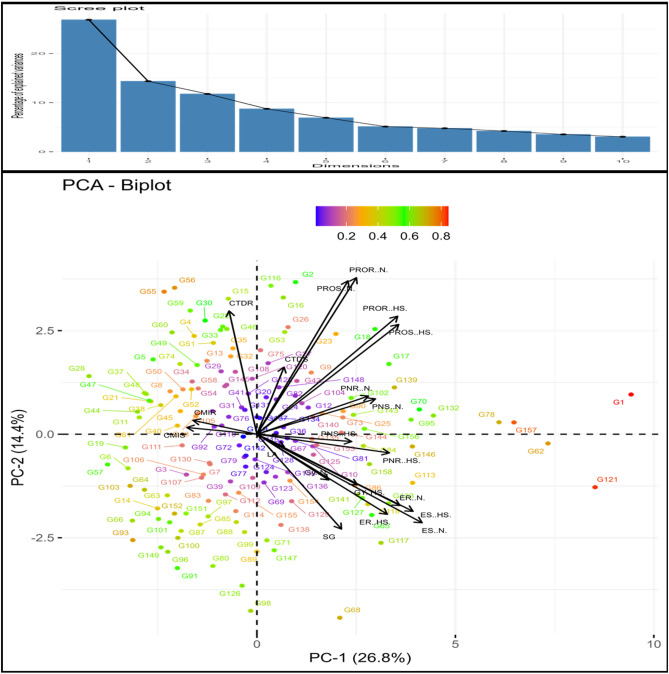

Multivariate analysis techniques including principal component analysis, correlation analysis and cluster analysis were employed to discern the genetic variability among wheat genotypes based on their physiological traits and grain yield. Principal component analysis unveiled that first six principal components exhibited more than 1 Eigen value, collectively contributing 73.7% of the total variability. However, graphical representation of all variables was constructed, emphasizing the highest contribution from the first two principal components, which accounted for 41.2% of the variability (Fig. 2). PC1 and PC2 contributed 26.9% and 14.4% of the variability, respectively. Highest contributing traits were proline content, transpiration rate at vegetative and reproductive stage, canopy temperature depression at reproductive stage and stay green under both conditions. Cluster analysis based on the dataset revealed seven distinct clusters of wheat genotypes under both normal and heat stress conditions. Remarkably, genotype G23 exhibited the highest proline content under normal conditions, whereas genotype G18 displayed this trait prominently under heat stress conditions, at both vegetative and reproductive stages. Additionally, genotype G-133 showcased the highest transpiration rate under normal conditions, while genotypes G-117 and G-65 demonstrated this trait prominently under heat stress conditions.

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of scree plot showing the percentage of variability of principal components and contribution of traits towards variability of physiological traits under normal and heat stress conditions.

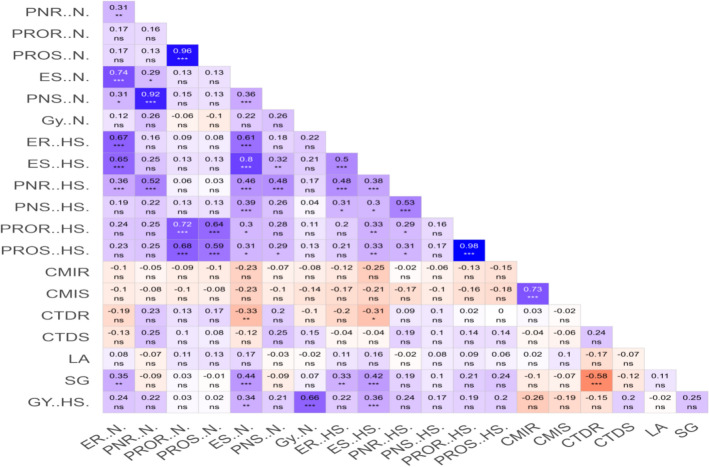

Correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationships between physiological traits and grain yield under both normal and heat stress conditions, as depicted in Fig. 3. Transpiration rate exhibited a synergistic association with photosynthetic rate at both stages, irrespective of the environmental conditions. Conversely, cell membrane injury demonstrated an antagonistic relationship with all studied traits; however, these associations were found to be non-significant at both the vegetative and reproductive stages. Notably, 'stay green' exhibited a significant positive correlation with transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate, and proline content under both normal and heat stress conditions. Furthermore, grain yield demonstrated a synergistic relationship with transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate, proline content, and grain yield under both normal and heat stress conditions.

Fig. 3.

Graphcial display showing the association of physiological traits under normal and heat stress conditions where n.s: non-significant, * at p = 0.05, ** at p = 0.01 and *** p = 0.001.

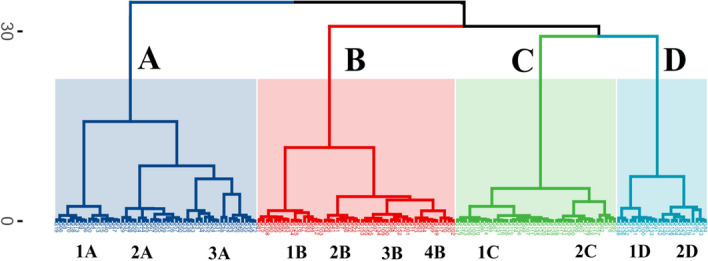

Cluster analysis was implemented utilizing Ward's method to stratify the wheat genotypes into distinct groupings, as depicted in Fig. 4. This method effectively segregated the wheat genotypes into four primary clusters denoted as Cluster-A, Cluster-B, Cluster-C, and Cluster-D. Cluster-A exhibited further subdivision into three subgroups: cluster-1A, comprising 16 genotypes; cluster-2A, comprising 15 genotypes; and cluster-3A, comprising 18 genotypes. Similarly, Cluster-B showcased division into subgroups namely cluster-1B consisting of 16 genotypes, cluster-2B consisting of 9 genotypes, cluster-3B consisting of 13 genotypes and cluster-4B consisting of 10 genotypes. Moreover, both Cluster-C and Cluster-D manifested subdivision into two subgroups. Cluster-1C and cluster-2C comprised of 24 and 15 genotypes respectively within Cluster-C and cluster-1D and cluster-2D consisted of 10 and 12 genotypes respectively within Cluster-D. Cluster-A predominantly comprised wheat varieties sourced from various institutes across Pakistan, while clusters-B, cluster-C and cluster-D primarily encompassed wheat genotypes obtained from CIMMYT advanced lines and Pakistani varieties recommended for rainfed areas.

Fig. 4.

Dendrogram representing the grouping of wheat genotypes based on their physiological traits under normal and heat stress conditions.

Allelic frequency and PIC

Allelic frequency and polymorphic content determines the genetic variability among chromosomes and genomes. However, 341 alleles (2–13 alleles) were calculated on genome-A whereas 246 alleles (2–10 alleles) on genome-B and 275 alleles (2–9 alleles) on genome-D. Notably, the highest allelic frequency was observed on genome-A (4.94), followed by genome-B (4.56), and genome-D (4.37). Among chromosomes, highest mean alleles (5.00) possessed by chromosome 1 (Table 2). Remarkably, highest allelic frequency (13 alleles) was calculated on marker xgwm44 (Supplementary Material Table 3). Moreover, the polymorphic information content (PIC) value was maximized on genome-A (0.688), succeeded by genome-B (0.663) and genome-D (0.658). Noteworthy, chromosome 1 boasted the highest PIC value (0.712), followed by chromosome 7 (0.690) and chromosome 3 (0.684).

Table 2.

Genetic diversity in wheat genomes revealed by 186 SSR markers.

| Loci | Allele frequency | Mean alleles | Alleles range | PIC mean | PIC value range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A genome | 69 | 341 | 4.94 | 2–13 | 0.688 | 0.151–0.916 |

| B genome | 54 | 246 | 4.56 | 2–10 | 0.663 | 0.135–0.885 |

| D genome | 63 | 275 | 4.37 | 2–9 | 0.658 | 0.052–0.859 |

| Whole genome | 186 | 862 | 4.63 | 2–13 | 0.671 | 0.052–0.916 |

| Chromosome 1 | 44 | 220 | 5.00 | 2–10 | 0.712 | 0.450–0.879 |

| Chromosome 2 | 25 | 103 | 4.12 | 2–7 | 0.628 | 0.052–0.839 |

| Chromosome 3 | 23 | 105 | 4.57 | 3–9 | 0.684 | 0.516–0.872 |

| Chromosome 4 | 25 | 118 | 4.72 | 2–13 | 0.637 | 0.133–0.916 |

| Chromosome 5 | 29 | 131 | 4.52 | 2–9 | 0.672 | 0.221–0.829 |

| Chromosome 6 | 19 | 91 | 4.78 | 2–8 | 0.668 | 0.280–0.846 |

| Chromosome 7 | 21 | 94 | 4.48 | 2–8 | 0.690 | 0.372–0.859 |

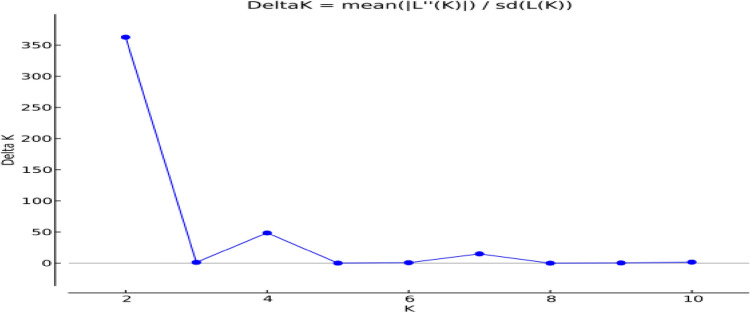

Population structure of wheat collection

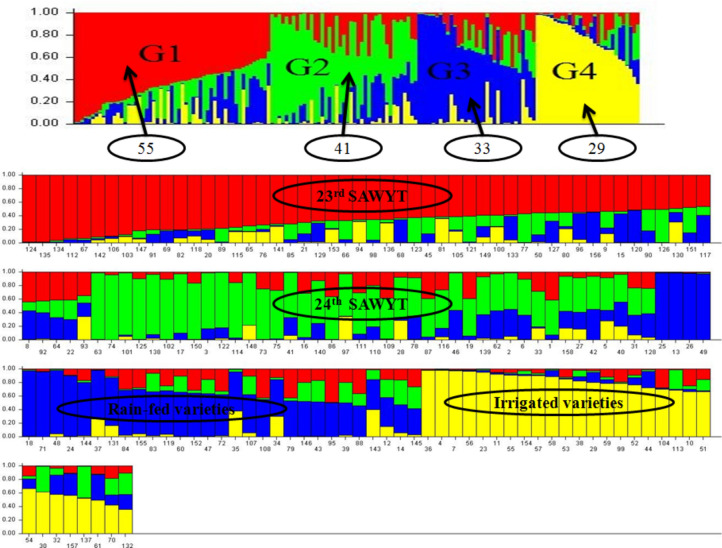

Population structure was derived to determine genetic similarity among the wheat accessions. Remarkably, DeltaK (K = 4) clearly partitioned the wheat accessions into four groups (Fig. 5). Subpopulation G1 exhibited the highest number of wheat accessions (55) comprising primarily accessions sourced from the 23rd Semi-Arid Wheat Yield Trial (SAWYT) originating from CIMMYT and certain varieties historically cultivated in Pakistan including Chakwal-97 and Chakwal-86 (Fig. 6). Subpopulation G2 encompassed 41 wheat accessions including lines collected from 24th SAWYT and certain varieties popular in Pakistan including Dirk, Rawal-87, Mexipak, Bahawalpur-97, Sariab-92 and TD-1. Meanwhile, subpopulation G3 comprised 33 wheat varieties primarily cultivated in the rain-fed regions of Pakistan, inclusive of popular varieties like Khirman, Sarsabz, Zardana, SKD-1, Sarhad-82, Pirsabak-91, and Pirsabak-05. Lastly, subpopulation G4 encapsulated 29 wheat varieties predominantly favored in irrigated areas, such as Faisalabad-08, Miraj-2001, Wafaq-2001, Lasani-08, Punjab-11, and Shahkar-13, suggesting a shared ancestral origin among these accessions.

Fig. 5.

Population structure estimation to identify the DeltaK from population ranging from 1 to 10. DeltaK is the function of K, the peak K = 4 represent the 4 subpopulations.

Fig. 6.

Bayesian approach based Population Structure of 158 wheat genotypes observing 4 clusters based on inferred ancestry analyzed by 186 SSR markers. Each color segment represents the membership fraction of each genotype. Horizontal coordinates represents the codes of wheat accession in Supplementary material Table 1.

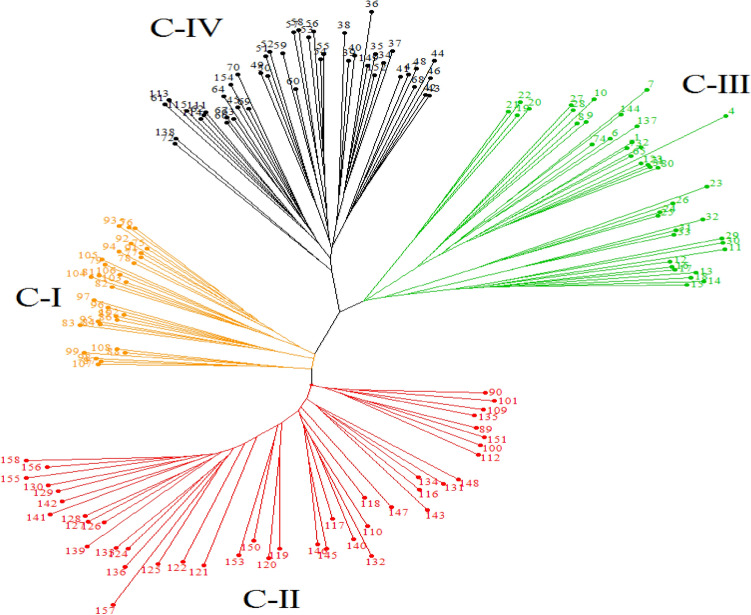

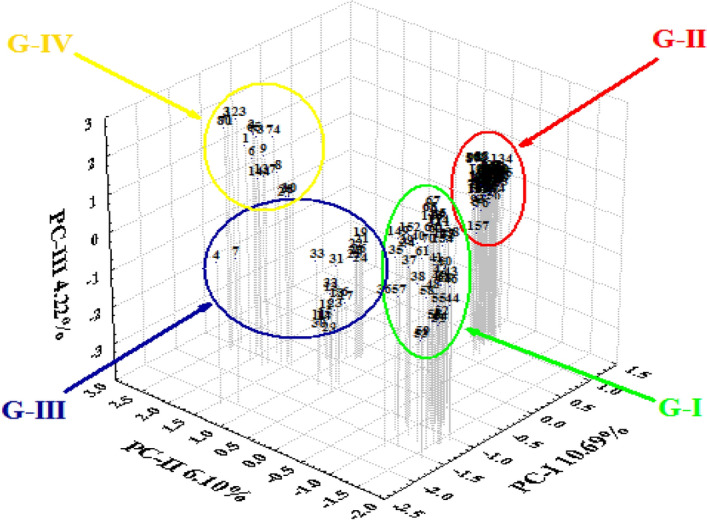

Cluster analysis also categorized the wheat accessions into distinct four groups based on their genetic dissimilarity (Fig. 7). Cluster 1 (C-I) comprised 30 accessions, with 29 originating from the 23rd Semi-Arid Wheat Yield Trial (SAWYT). Meanwhile, Cluster 2 (C-II) encompassed 43 accessions, among which 36 were derived from the 24th SAWYT. Cluster 3 (C-III) featured 40 lines, with 37 representing varieties prevalent in the rain-fed regions of Pakistan, alongside three belonging to the 24th SAWYT. Cluster 4 (C-IV) consisted of 45 accessions, with 38 representing well known varieties in irrigated areas of Pakistan, three sourced from the 23rd SAWYT and four from 24th SAWYT. Additionally, as an alternative to the Bayesian approach, principal coordinate analysis was employed to characterize wheat accessions. First three principal components (PCs) collectively accounted for 21.01% of the variation (PC1: 10.69%, PC2: 6.10%, and PC3: 4.22%), those distinctly segregated the 158 wheat accessions into four major groups (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Clustering of wheat genotypes into four clusters based on dissimilarity matrix using Jacords method with 1000 permutations. Different color lines represent each cluster viz., C-I, C-II, C-III and C-IV. Codes of accessions are provided in the supplementary material Table 1.

Fig. 8.

3D plotting of principal coordinate analysis based on SSR marker analysis of the wheat accession. Different circles represent the geographical ecotype and codes provided in supplementary material Table 1.

Linkage disequilibrium and linkage disequilibrium decay

SSR identified LD pattern evident at chromosome and genome level. In current investigation, a total of 20,107 linked locus pair were discerned across all three genomes of wheat. Notably, highly significant loci (P < 0.001) exhibiting linked locus pairs with r2 > 0.1, r2 > 0.2 and r2 > 0.5 were 1553 (7.7%), 665 (3.3%) and 125 (0.6%) respectively (Table 3). Genome-A had 10,753 linked locus pairs and highly significant locus pairs (P < 0.001) with r2 > 0.1, r2 > 0.2 and r2 > 0.5 were 1159 (10.8%), 267 (2.5%) and 24 (0.2%), respectively. Genome-B displayed 4429 linked locus pairs, among which those demonstrating significance (P < 0.001) with r2 > 0.1, r2 > 0.2 and r2 > 0.5 were 513 (11.6%), 275 (6.2%) and 66 (1.5%) linked locus pairs, respectively. Additionally, Genome-D exhibited 4925 linked locus pairs and P < 0.001 with r2 > 0.1, r2 > 0.2 and r2 > 0.5 were 214 (4.4%), 123 (2.5%) and 35 (0.7%) linked loci, respectively.

Table 3.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) pattern on individual genome at significant (P-value < 0.001) linkage disequilibrium utilizing 186 SSR markers.

| Genome | Observed | P < 0.001 (%) | r2 > 0.1(%) | r2 > 0.2(%) | r2 > 0.5(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linked locus pair | |||||

| Genome A | 10,753 | 1159 (10.8) | 826 (7.7) | 267 (2.5) | 24 (0.2) |

| Genome B | 4429 | 630 (14.2) | 513 (11.6) | 275 (6.2) | 66 (1.5) |

| Genome D | 4925 | 270 (5.5) | 214 (4.4) | 123 (2.5) | 35 (0.7) |

| Genome wide | 20,107 | 2059 (10.2) | 1553 (7.7) | 665 (3.3) | 125 (0.6) |

| Unlinked locus pair | |||||

| Genome A | 42,222 | 3690 (8.7) | 2567 (6.1) | 830 (1.9) | 70 (0.2) |

| Genome B | 23,301 | 2256 (9.7) | 1828 (7.8) | 1106 (4.8) | 364 (1.6) |

| Genome D | 29,266 | 2515 (8.6) | 2035 (6.9) | 1237 (4.2) | 440 (1.5) |

| Genome wide | 94,789 | 8461 (8.9) | 6430 (6.8) | 3173 (3.4) | 874 (0.9) |

In Genome-A, the chromosome 1A exhibited the highest number of paired loci (8001) with significant associations (P < 0.001) observed at varying levels of r2 thresholds including r2 > 0.1, r2 > 0.2 and r2 > 0.5 were 621, 202 and 13 paired loci, respectively (Table 4). Within the B genome, chromosome 5B was distinguished by a notable presence of highly significant (P < 0.001) paired loci, with counts at r2 > 0.1 (96), r2 > 0.2 (48), and r2 > 0.5 (16). Similarly, among the D genome chromosomes, chromosome 1D showcased significant paired loci at P < 0.001 with r2 > 0.1 (57), r2 > 0.2 (32) and r2 > 0.5 (6). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay was conducted across the entire genome as well as individual chromosomes of wheat. Particularly, the largest LD block of 15–20 cM was discerned on chromosome 1A. On average, the LD block within the chromosomes of genome-A exhibited a range of 5–10 cM at P < 0.01 and r2 > 0.1 (Supplementary material Table 6). Contrastingly, the LD decay was notably less than 5 cM, for both the genome-B and genome-D.

Table 4.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) pattern on individual chromosome at significant (P-value < 0.001) linkage disequilibrium utilizing 186 SSR markers.

| Genome A | 1A | 2A | 3A | 4A | 5A | 6A | 7A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | 8001 | 496 | 231 | 1378 | 528 | 780 | 820 |

| P < 0.001 | 860 | 56 | 19 | 62 | 71 | 91 | 97 |

| r2 > 0.1 | 621 | 41 | 13 | 44 | 52 | 50 | 72 |

| r2 > 0.2 | 202 | 19 | 10 | 18 | 24 | 11 | 25 |

| r2 > 0.5 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Genome B | 1B | 2B | 3B | 4B | 5B | 6B | 7B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | 465 | 820 | 990 | 465 | 1711 | 78 | 325 |

| P < 0.001 | 127 | 65 | 130 | 41 | 127 | 10 | 33 |

| r2 > 0.1 | 96 | 53 | 102 | 37 | 96 | 8 | 26 |

| r2 > 0.2 | 59 | 23 | 68 | 29 | 48 | 7 | 21 |

| r2 > 0.5 | 19 | 3 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 10 |

| Genome D | 1D | 2D | 3D | 4D | 5D | 6D | 7D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | 1431 | 496 | 861 | 595 | 861 | 703 | 496 |

| P < 0.001 | 66 | 39 | 69 | 93 | 63 | 86 | 118 |

| r2 > 0.1 | 57 | 30 | 60 | 75 | 56 | 65 | 96 |

| r2 > 0.2 | 32 | 19 | 40 | 37 | 41 | 48 | 60 |

| r2 > 0.5 | 6 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 16 | 20 | 18 |

Marker trait association

MTA analysis was conducted utilizing the set of 186 SSR markers to explore associations with traits observed under both normal and heat stress conditions (Table 5). A consistent set of marker trait associations, exhibiting resilience across both standard and heat stress circumstances, focusing on key physiological traits such as transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate and proline content with two distinct associations identified, denoted by the markers Xcfa2147 and Xwmc418. Similarly, a parallel stability was observed with two notable associations for grain yield, attributed to the markers Xcfd30 and Xbarc8, thus underlining the robustness of these markers across varied environmental conditions. Moreover, the relative performance of physiological attributes such as cell membrane injury, canopy temperature depression, leaf angle, and stay green was leveraged to discern marker trait associations under heat stress conditions. As a result, a total of 16 marker trait associations, underscoring the efficacy of this methodology in elucidating key genetic relationships amidst challenging environmental conditions.

Table 5.

Marker trait associations (MTAs) for physiological traits under normal and heat stress.

| Trait | Marker | Chr | cM | P | R2 | Trait | Marker | Chr | cM | P | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal conditions | |||||||||||

| EV | xcfa2147.4 | 1B | 108.8 | 0.000568 | 0.08073 | PROV | xbarc42.3 | 3D | 17.0 | 0.000687 | 0.09049 |

| EV | xwmc418.4 | 3B | 73.0 | 0.000518 | 0.08178 | PROR | xbarc42.1 | 3D | 17.5 | 0.000249 | 0.10614 |

| GY | xcfd27.3 | 1D | 108.9 | 0.00337 | 0.05012 | GY | xcfd160.2 | 2D | 94.5 | 0.00062 | 0.06415 |

| GY | xcfd30.4 | 6A | 129.5 | 0.00355 | 0.04124 | GY | xbarc35.4 | 2B | 36.9 | 0.00061 | 0.07154 |

| GY | xbarc8.3 | 1B | 53.6 | 0.00221 | 0.04127 | GY | xwmc28.3 | 5B | 144.7 | 0.00125 | 0.06257 |

| Heat stress | |||||||||||

| EV | xwmc11.1 | 3A | 13.0 | 0.000996 | 0.07322 | ER | xwmc469.5 | 1A | 63.5 | 0.000177 | 0.08583 |

| EV | xcfa2147.4 | 1B | 108.8 | 0.000145 | 0.09487 | ER | xwmc11.1 | 3A | 13.0 | 0.000239 | 0.10240 |

| EV | xwmc418.2 | 3B | 73.0 | 0.000120 | 0.09704 | ER | xgwm233.1 | 7A | 7.5 | 0.000130 | 0.11032 |

| EV | xgdm125.1 | 4D | 61.2 | 0.000539 | 0.06324 | ER | xgwm18.1 | 1B | 33.8 | 0.000730 | 0.06903 |

| CTDV | xwmc150.1 | 2A | 113.3 | 0.000730 | 0.07102 | ER | xcfd76.1 | 6D | 68.3 | 0.000730 | 0.06903 |

| CTDR | xcfa2129.3 | 1A | 79.5 | 0.000073 | 0.06896 | CMIV | xbarc163.3 | 4B | 35.1 | 0.000071 | 0.06924 |

| CTDR | xwmc11.1 | 3A | 13.5 | 0.000131 | 0.07873 | CMIV | xwmc47.4 | 4B | 9.1 | 0.000899 | 0.06094 |

| CTDR | xwmc201.6 | 6A | 43.0 | 0.000084 | 0.06771 | CMIV | xwmc331.4 | 4D | 33.0 | 0.000325 | 0.07027 |

| CTDR | xwmc553.6 | 6A | 46.8 | 0.000274 | 0.05756 | CMIR | xgdm153.2 | 5D | 68.5 | 0.000262 | 0.07225 |

| CTDR | xcfa2147.1 | 1B | 108.6 | 0.000076 | 0.08376 | CMIR | xcfd42.3 | 6D | 39.6 | 0.000636 | 0.06410 |

| CTDR | xwmc175.5 | 2B | 89.7 | 0.000165 | 0.07653 | CMIR | xbarc96.1 | 6D | 98.0 | 0.000202 | 0.07469 |

| CTDR | xwmc418.4 | 3B | 73.0 | 0.000131 | 0.07874 | CMIR | xwmc463.4 | 7D | 71.8 | 0.0000079 | 0.08880 |

| PNV | xgwm494.6 | 3A | 37.5 | 0.000083 | 0.11789 | PNR | xbarc113.1 | 3A | 43.5 | 0.000935 | 0.08381 |

| PNV | xwmc73.4 | 5B | 73.5 | 0.000162 | 0.10894 | PNR | xgwm494.6 | 3A | 37.5 | 0.000669 | 0.08803 |

| SG | xbarc49.3 | 7A | 83.0 | 0.000159 | 0.05872 | PNR | xbarc156.2 | 5B | 36.0 | 0.000542 | 0.09069 |

| GY | xbarc71.4 | 3D | 48.7 | 0.004112 | 0.08421 | GY | xbarc8.4 | 1B | 25.5 | 0.002914 | 0.06474 |

| GY | xbarc197.3 | 5A | 117.4 | 0.003231 | 0.08154 | GY | xcfd30.1 | 6A | 129.5 | 0.002345 | 0.07154 |

| GY | xcfa2147.1 | 1B | 108.8 | 0.000916 | 0.09154 | GY | xcfd132.1 | 6D | 41.8 | 0.003047 | 0.08154 |

| GY | xbarc83.1 | 1A | 53.7 | 0.000820 | 0.07687 | GY | xwmc671.5 | 7D | 111.7 | 0.000262 | 0.07415 |

| GY | xcfd59.2 | 1A | 61.1 | 0.000411 | 0.08454 | GY | xgdm72.3 | 3D | 34.0 | 0.000916 | 0.08975 |

| GY | xwmc75.4 | 5B | 118.5 | 0.000197 | 0.08786 | ||||||

Chr Chromosome, cM Position in centimorgan, P Probability, R2 Correlation coefficient, ProV Proline content at vegetative stage, ProR Proline content at reproductive stage, PnV Photosynthetic rate at vegetative stage, PnR Photosynthetic rate at reproductive stage, EV Transpiration rate at vegetative stage, ER Transpiration rate at reproductive stage, CMIV Cell membrane injury at vegetative stage, CMIR Cell membrane injury at reproductive stage, CTDV Canopy temperature depression at vegetative stage, CTDR Canopy temperature depression at reproductive stage, SG Stay green, GY Grain yield per plant.

Individually, ten highly significant (P < 0.001) MTAs were identified under normal conditions while forty one MTAs were observed under heat stress conditions for grain yield and physiological attributes but here we discussed the most significant associations using a Bonferroni correction for stringent threshold cut-off at P < 0.00027. Notably, proline content at the reproductive stage exhibited a significant correlation with marker Xbarc42 (3D at 17 cM) under normal conditions. Conversely, under heat stress, the transpiration rate at the vegetative stage demonstrated an association with marker Xwmc418 (3B at 37 cM), while the transpiration rate at the reproductive stage was linked to marker Xgwm233 (7A at 7 cM). Moreover, the photosynthetic rate at both vegetative and reproductive stages exhibited correlations with marker Xgwm494 (3A at 37 cM). Canopy temperature depression at the reproductive stage displayed highly significant associations with markers Xcfa2129 (1A at 79 cM) and Xwmc201 (6A at 43 cM) under heat stress conditions. Furthermore, cell membrane injury showed an association with marker Xbarc163 (4B at 35 cM) at the vegetative stage, while at the reproductive stage, it was linked to marker Xwmc463 (7D at 73 cM) specifically under heat stress conditions. The 'stay green' trait exhibited a significant association with marker Xbarc49 (5A at 83 cM) under heat stress conditions.

Discussion

Temperature influences wheat growth and development. Optimal temperature at reproductive stage viz., heading (15–22 °C), anthesis (23–26 °C) and grain filling (26–28 °C) is the prerequisite for crop growth that maintains the physiological processes and metabolic activities3,84–89. Heat stress exposed the wheat plants to 3–4 °C above the threshold level and prompting the completion of growing degree days (GDD) earlier14. In present study, the high temperature during tillering and anthesis stage restricts the efficiency of physiological and metabolic processes. High temperature induces the leaf senescence due to high canopy temperature that destabilizes the physiological processes viz., cell membrane stability, photosynthesis and transpiration. Therefore, wheat plants capable of maintaining traits such as 'stay-green' characteristics, cooler canopy temperatures, transpiration rates, photosynthetic rates, proline content, and cell membrane integrity exhibit enhanced potential for grain yield under heat stress conditions90–94. Furthermore, the moderate to high heritability values observed across these traits suggest a degree of uniformity in genotype performance across different growing seasons, consistent with previous findings28,95,96.

Multivariate analysis techniques for assessing genetic diversity prove instrumental in unraveling the spectrum of variability within wheat germplasm and identification of desirable traits in breeding programs. Principal component analysis and cluster analysis enabled the quantification of genetic variability based on the phenotypic traits97. It simplifies the high dimensional data into fewer one. Principal component analysis serves as a powerful tool for gauging the extent of variation across traits and delineating their respective contributions to overall variability98. In current study, proline content, transpiration rate, canopy temperature depression and stay green emerged as key determinants, streamlining the selection process for enhancing wheat yield in subsequent breeding endeavors under heat stress conditions. Notably, these traits have been previously underscored by researchers as pivotal targets for bolstering wheat productivity in the face of heat stress challenges, underscoring their significance in breeding programs aimed at mitigating adverse environmental conditions99,100.

Moreover, association of physiological traits with grain yield is also essential to unveil the complex quantitative traits. Assessing the strength of linear relationships, one can effectively discern and prioritize traits that exhibit significant correlations with grain yield, thereby facilitating the selection of desirable attributes crucial for enhancing wheat crop productivity11. Notably, under heat stress conditions, a noteworthy positive correlation was observed between grain yield and physiological parameters such as proline content, transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate, and 'stay-green' characteristics, while a negative correlation was noted with cell membrane injury.

High temperature induces a rise in canopy temperature, exerting a profound impact on the integrity of cell membranes within wheat leaves. It prompts the increase in kinetic energy within the molecular bonds connecting proteins and the lipid bi-layer of cell membranes, leading to bond rupture and subsequent electrolyte leakage3. This disruption in cell structure invariably interferes with pivotal physiological processes, including photosynthesis and transpiration rate90. High temperature also enhances the proline content in tolerant plant due to conversion of glutamate into proline content, serving as a protective mechanism against changing environmental conditions34.

Cluster analysis serves as a valuable tool in the identification and selection of promising wheat lines with diverse genetic backgrounds, thereby informing targeted breeding programs aimed at enhancing crop traits and productivity101. In the present study, wheat genotypes were stratified into four distinct clusters, each represents the specific genetic profiles and origins. Cluster 1 comprised genotypes sourced from various research institutes across Pakistan, while clusters 2 and 3 predominantly consisted of lines derived from the 23rd and 24th Semi-Arid Wheat Yield Trial (SAWYT) of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). Interestingly, cluster 4 possessed genotypes representing a mixture of Pakistani cultivars and CIMMYT lines, suggesting the potential shared parentage owing to the historical introduction of Pakistani cultivars from CIMMYT germplasm. Clustering approach has previously been employed to elucidate patterns of similarity and genetic diversity within wheat genotypes99,102 that assist breeder in understanding of wheat germplasm dynamics and aiding in the selection of superior breeding lines.

Polymorphism information content allelic frequency on genomes and chromosomes provides valuable insights into the distribution of genetic diversity and aids in targeting gene rich regions of genome and chromosome11,46,103. Higher number of alleles and PIC value represents the higher genetic rich regions. In the present investigation, the analysis revealed that the allelic frequency and PIC values followed the order of genome-D being the lowest subsequently genome-B and with genome-A exhibiting the highest values suggesting that genome-A harbors regions of greater genetic richness compared to genomes-B and genome-D among the Pakistani wheat cultivars and CIMMYT lines. These results delineate the potential targets for further exploration and exploitation in breeding programs aimed at enhancing wheat genetic diversity and productivity.

Bayesian approach based population structure utilizes relatedness frequencies among accessions in each group indicate geographic habitat104,105 resulting in the formation of four clusters as determined by the software STRUCTURE. These results from the population structure analysis of the two CIMMYT trials, 23rd SAWYT and 24th SAWYT, and the historic varieties from various Pakistani provinces agreed with that expected based on the pedigree records. Prior, two main groups were predicted viz., CIMMYT lines and Pakistani accessions based on their geopgraphical origin but there was greater genetic variability in wheat accessions that lead to four groups. The unexpected grouping accessions may be due to geographical origin, selection of germplasm and varietal age that infleuences the structure of wheat accessions.

Consistency and reliability of this grouping methodology are reaffirmed through cluster analysis and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) as reported earlier11,106,107. PCoA, serving as an alternative visualization tool for genotype data based on genetic distances, delineates the wheat accessions into four distinct groups, corroborating the findings of the population structure analysis. Moreover, the utilization of the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering further confirms the division of wheat accessions into four groups, thereby validating the results derived from the population structure analysis and phenotypic evaluation of wheat based on physiological attributes and grain yield. Genetic similarity within each sub-population suggested common parentage among the constituent accessions, particularly evident post-1960s, where a majority of Pakistani wheat varieties either directly originated from CIMMYT or were developed through cross-breeding with CIMMYT germplasm108. This historical context likely accounts for the notable genetic resemblance among lines with varieties such as SOKOLL, PASTOR, KAUZ, and WBLL from CIMMYT emerging as apparent progenitors for many Pakistani wheat accessions (Supplementary material 1).

Association mapping requires presence of LD and strong association among linked loci indicated LD decay109. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis employing 186 SSR markers was undertaken to elucidate the LD pattern across each genome and chromosome. Understanding the LD pattern intensifies the precision of identifying marker-trait associations (MTAs) both at the chromosome and genome levels, thereby facilitating a deeper understanding of the genetic architecture underlying quantitative traits53,54,110.

LD decay was determined using paired loci and their genetic distance measured in centimorgan111,112. LD decay within shorter genetic distance designates the higher resolution of association mapping and vice versa. Therefore, the detection of larger LD blocks within shorter genomic regions becomes imperative for enhancing the precision of association mapping113,114. In current study, LD decay was the highest (5–10 cM) on the A genome and chromosome 1A (15–20 cM) representing highest number of loci in relation to other chromosomes. Notably, chromosome 1A emerges as a prime candidate for the identification of genomic loci linked to target traits, especially among Pakistani and CIMMYT wheat accessions, highlighting its significance in future breeding endeavors.

Population structure greatly affects the association mapping efficiency and may identify false positives due to spurious correlations115,116. Traditional approaches often encounter difficulties in accurately identifying genes associated with quantitative traits within a single population due to the inherent variability in genetic differentiation and phenotypic expression across diverse geographical regions117. Statistical methods were developed to manage population structure to minimize the detection of false positives but that resulted in the detection of false negative associations56,118. Mixed Linear Model remove these associations using Q matrix extracted from population structure and relative kinship matrix among loci115,119.

Association mapping emerges as a pivotal tool for unraveling the intricate genetic architecture underlying quantitative traits associated with thermo-tolerance in wheat, offering insights into the molecular mechanisms governing heat stress responses. In the present study, several MTAs were identified for transpiration rate (3B and 7A), canopy temperature depression (1A and 6A), photosynthetic rate (3A), cell membrane injury(4B, 7D) and ‘stay green’(5A) under heat stress conditions whereas MTA were identified for proline content (3D) under normal conditions. Marker trait associations were previously reported for stay green on chromosome 5B, 5A, 4A, 4B, 4D, 3B, 7B120,121, photosynthetic rate on 4A, 5A, 7A122,123, canopy temperature depression on 2D, 4D, 6A124,125 and membrane stability on 7D126. However, intriguingly, leaf angle failed to exhibit significant associations with any marker under heat stress conditions, potentially attributed to limitations in the SSR markers employed for association mapping or inherent disparities in the genetic composition of the studied genotypes. Identification of these MTAs serves as a fundamental aspect for devising marker assisted selection strategies against thermo-tolerance in wheat.

Conclusion

Marker trait association analysis has revealed genomic regions associated with key physiological traits involved in heat stress tolerance in wheat. Proline content, transpiration rate, canopy temperature depression, and stay green have emerged as robust selection criteria for identifying thermo-tolerant germplasm, exhibiting positive correlations with grain yield in wheat. PIC value and allelic frequency was perceived from lowest to highest D < B < A suggesting higher genetic rich regions for targeting on genome A than B and D. Moreover, principal component analysis and cluster analysis, employing phenotypic data, successfully categorized wheat accessions into four distinct groups. These findings were consistent with results obtained from principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), cluster analysis, and population structure analysis using genotypic data, thereby indicating their geographical origins. LD decay on chromosome 1A suggested the potential for uncovering the genes associated with heat tolerant trait. Stable markers assiciated with physiological traits under normal and heat stress provides valuable insights for future MAS strategy for improving thermo-tolerance in wheat.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Higher Education Commision Pakistan fellowship for funding 6 months during International Research Support Initiative Programme [Grant No. I-8/HEC/HRD/2018/8515] and the Gill lab, Washington State University, USA for the help with the DNA marker part of the project.

Author contributions

A.K. conducted the phenotypic data under the supervision of M.A. in Pakistan, Genotypic data was conducted in USA under the supervision of M.A., A.K. collected the data, and wrote the manuscript, M.K.R.K. and M.Y.S. analyzed the data, M.R., and D.K.Y.T. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by Higher Education Commision Pakistan fellowship for funding 6 months during International Research Support Initiative Programme [Grant No. I-8/HEC/HRD/2018/8515].

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Adeel Khan, Email: adeelkhanbreeder@gmail.com.

Mehdi Rahimi, Email: mehdi83ra@yahoo.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70630-0.

References

- 1.Bai, H., Xiao, D., Wang, B., Li Liu, D. & Tang, J. Simulation of wheat response to future climate change based on coupled model inter-comparison project phase 6 Multi-Model ensemble projections in the North China Plain. Front. Plant Sci.13, 829580 (2022). 10.3389/fpls.2022.829580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obembe, O. S., Hendricks, N. P. & Tack, J. Decreased wheat production in the USA from climate change driven by yield losses rather than crop abandonment. PLoS ONE16, e0252067 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0252067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan, A., Ahmad, M., Ahmed, M. & Iftikhar Hussain, M. Rising atmospheric temperature impact on wheat and thermotolerance strategies. Plants10, 43 (2021). 10.3390/plants10010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grace, M. A. et al. An overview of the impact of climate change on pathogens, pest of crops on sustainable food biosecurity. Int. J. Ecotoxicol. Ecobiol.4, 114 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porfirio, L. L., Newth, D., Finnigan, J. J. & Cai, Y. Economic shifts in agricultural production and trade due to climate change. Palgrave Comm.4, 1–9 (2018). 10.1057/s41599-018-0164-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao, C. et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proceed. Nat. Acad. Sci.114, 9326–9331 (2017). 10.1073/pnas.1701762114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon, C. et al. Climate change research and action must look beyond 2100. Glob. Change Biol.28, 349–361 (2022). 10.1111/gcb.15871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shewry, P. R. & Hey, S. J. The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food Energy Secur.4, 178–202 (2015). 10.1002/fes3.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, B. et al. Separating the impacts of heat stress events from rising mean temperatures on winter wheat yield of China. Environ. Res. Lett.16, 124035 (2021). 10.1088/1748-9326/ac3870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain, J. et al. Effect of temperature on sowing dates of wheat under arid and semi-arid climatic regions and impact quantification of climate change through mechanistic modeling with evidence from field. Atmos.12, 927 (2021). 10.3390/atmos12070927 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan, A., Ahmad, M., Ahmed, M., Gill, K. S. & Akram, Z. Association analysis for agronomic traits in wheat under terminal heat stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.28, 7404–7415 (2021). 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatti, M. T., Balkhair, K. S., Masood, A. & Sarwar, S. Optimized shifts in sowing times of field crops to the projected climate changes in an agro-climatic zone of Pakistan. Exp. Agric.54, 201–213 (2018). 10.1017/S0014479716000156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubey, R. et al. Impact of terminal heat stress on wheat yield in India and options for adaptation. Agric. Sys.181, 102826 (2020). 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslam, M. A., Ahmed, M., Stöckle, C. O., Higgins, S. S. & Hayat, R. Can growing degree days and photoperiod predict spring wheat phenology. Front. Environ. Sci.5, 57–68 (2017). 10.3389/fenvs.2017.00057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upadhyaya, N. & Bhandari, K. Assessment of different genotypes of wheat under late sowing condition. Heliyon8, e08726 (2022). 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royo, C. et al. Allelic variation at the vernalization response (Vrn-1) and photoperiod sensitivity (Ppd-1) genes and their association with the development of durum wheat landraces and modern cultivars. Front. Plant Sci.11, 838 (2020). 10.3389/fpls.2020.00838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moshatati, A., Siadat, S., Alami-Saeid, K., Bakhshandeh, A. & Jalal-Kamali, M. The impact of terminal heat stress on yield and heat tolerance of bread wheat. Int. J. Plant Prod.11, 549–559 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittal, A., Kaviani, M., Graf, R., Humphreys, G. & Navabi, A. Allelic variation of vernalization and photoperiod response genes in a diverse set of North American high latitude winter wheat genotypes. PloS One13, e0203068–e0203068 (2018). 10.1371/journal.pone.0203068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chovancek, E. et al. Transient heat waves may affect the photosynthetic capacity of susceptible wheat genotypes due to insufficient photosystem I photoprotection. Plants8, 282–309 (2019). 10.3390/plants8080282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ullah, S., Trethowan, R. & Bramley, H. The physiological basis of improved heat tolerance in selected emmer-derived hexaploid wheat genotypes. Front. Plant Sci.2057, 739246 (2021). 10.3389/fpls.2021.739246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djanaguiraman, M., Boyle, D., Welti, R., Jagadish, S. & Prasad, P. Decreased photosynthetic rate under high temperature in wheat is due to lipid desaturation, oxidation, acylation, and damage of organelles. BMC Plant Biol.18, 55 (2018). 10.1186/s12870-018-1263-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balla, K. et al. Single versus repeated heat stress in wheat: What are the consequences in different developmental phases?. PloS One16, e0252070 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0252070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Q.-L., Chen, J.-H., He, N.-Y. & Guo, F.-Q. Metabolic reprogramming in chloroplasts under heat stress in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19, 849 (2018). 10.3390/ijms19030849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiva, S. et al. Leaf lipid alterations in response to heat stress of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants9, 845 (2020). 10.3390/plants9070845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramani, H. et al. Biochemical and physiological constituents and their correlation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes under high temperature at different development stages. Int. J. Plant Physiol. Biochem.9, 1–8 (2017). 10.5897/IJPPB2015.0240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schittenhelm, S., Langkamp-Wedde, T., Kraft, M., Kottmann, L. & Matschiner, K. Effect of two-week heat stress during grain filling on stem reserves, senescence, and grain yield of European winter wheat cultivars. J. Agron. Crop Sci.206, 722–733 (2020). 10.1111/jac.12410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamal, N. M., Gorafi, Y. S. A., Abdelrahman, M., Abdellatef, E. & Tsujimoto, H. Stay-green trait: A prospective approach for yield potential, and drought and heat stress adaptation in globally important cereals. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 5837 (2019). 10.3390/ijms20235837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradhan, S. et al. Genetic dissection of heat-responsive physiological traits to improve adaptation and increase yield potential in soft winter wheat. BMC Genom.21, 1–15 (2020). 10.1186/s12864-020-6717-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tariq, A. et al. Evaluation of physiological and morphological traits for improving spring wheat adaptation to terminal heat stress. Plants10, 455 (2021). 10.3390/plants10030455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christopher, J. T., Christopher, M. J., Borrell, A. K., Fletcher, S. & Chenu, K. Stay-green traits to improve wheat adaptation in well-watered and water-limited environments. J. Exp. Bot.67, 5159–5172 (2016). 10.1093/jxb/erw276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Latif, S. et al. Deciphering the role of stay-green trait to mitigate terminal heat stress in bread wheat. Agron.10, 1001 (2020). 10.3390/agronomy10071001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustafa, T. et al. Exogenous application of silicon improves the performance of wheat under terminal heat stress by triggering physio-biochemical mechanisms. Sci. Rep.11, 1–12 (2021). 10.1038/s41598-021-02594-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed, M., Qadir, G., Shaheen, F. A. & Aslam, M. A. Response of proline accumulation in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under rainfed conditions. J. Agric. Meteorol.73, 147–155 (2017). 10.2480/agrmet.D-14-00047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dukic, N. H., Marković, S. M., Mastilović, J. S. & Simović, P. Differences in proline accumulation between wheat varieties in response to heat stress. Botanica Serbica45, 61–69 (2021). 10.2298/BOTSERB2101061D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narendra, M., Roy, C., Kumar, S., Virk, P. & De, N. Effect of terminal heat stress on physiological traits, grain zinc and iron content in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed.57, 43–50 (2021). 10.17221/63/2020-CJGPB [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deery, D. M. et al. Evaluation of the phenotypic repeatability of canopy temperature in wheat using continuous-terrestrial and airborne measurements. Front. Plant Sci.10, 875 (2019). 10.3389/fpls.2019.00875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhary, S. et al. Identification and characterization of contrasting genotypes/cultivars for developing heat tolerance in agricultural crops: Current status and prospects. Front. Plant Sci.11, 1505 (2020). 10.3389/fpls.2020.587264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verma, H., Borah, J. & Sarma, R. Variability assessment for root and drought tolerance traits and genetic diversity analysis of rice germplasm using SSR markers. Sci. Rep.9, 1–19 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-52884-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, X., Xu, Y., Hu, Z. & Xu, C. Genomic selection methods for crop improvement: Current status and prospects. The Crop J.6, 330–340 (2018). 10.1016/j.cj.2018.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaiswal, S. et al. Putative microsatellite DNA marker-based wheat genomic resource for varietal improvement and management. Front. Plant Sci.8, 2009 (2017). 10.3389/fpls.2017.02009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, L.-X. et al. Assessment of wheat variety distinctness using SSR markers. J. Int. Agric.14, 1923–1935 (2015). 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61057-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta, P. K., Kulwal, P. L. & Jaiswal, V. Association mapping in plants in the post-GWAS genomics era. Adv. Genet.104, 75–154 (2019). 10.1016/bs.adgen.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra, R. K. & Tomar, R. S. Molecular markers and their application in genetic mapping. Eur. Acad. Res.2, 4012–4040 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han, B. et al. Genome-wide analysis of microsatellite markers based on sequenced database in Chinese spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PloS One10, e0141540 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0141540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi, W. et al. A combined association mapping and linkage analysis of kernel number per spike in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci.8, 1412 (2017). 10.3389/fpls.2017.01412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibrahim, A. K. et al. Principles and approaches of association mapping in plant breeding. Tropical Plant Biol.13, 212–224 (2020). 10.1007/s12042-020-09261-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daware, A., Parida, S. K. & Tyagi, A. K. Cereal Genomics 15–25 (Springer, 2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oraguzie, N. C. & Wilcox, P. L. An overview of association mapping. Asso. Map. Plants 1–9 (2007).

- 49.Kushwaha, U. K. S. et al. Association mapping, principles and techniques. J. Biol. Environ. Eng.2, 1–9 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vinod, K. Association mapping in crop plants. Bioinform. Tools Genom. Res. 23 (2011).

- 51.Wurschum, T. et al. Population structure, genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium in elite winter wheat assessed with SNP and SSR markers. Theo. Appl. Genet.126, 1477–1486 (2013). 10.1007/s00122-013-2065-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishikawa, G. et al. An efficient approach for the development of genome-specific markers in allohexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and its application in the construction of high-density linkage maps of the D genome. DNA Res.25, 317–326 (2018). 10.1093/dnares/dsy004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mourad, A. M., Belamkar, V. & Baenziger, P. S. Molecular genetic analysis of spring wheat core collection using genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium. BMC Genom.21, 1–12 (2020). 10.1186/s12864-020-06835-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roncallo, P. F. et al. Linkage disequilibrium patterns, population structure and diversity analysis in a worldwide durum wheat collection including Argentinian genotypes. BMC Genom.22, 1–17 (2021). 10.1186/s12864-021-07519-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaler, A. S. & Purcell, L. C. Estimation of a significance threshold for genome-wide association studies. BMC Genom.20, 1–8 (2019). 10.1186/s12864-019-5992-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cortes, L. T., Zhang, Z. & Yu, J. Status and prospects of genome-wide association studies in plants. Plant Genom.14, e20077 (2021). 10.1002/tpg2.20077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mwadzingeni, L., Shimelis, H., Rees, D. J. G. & Tsilo, T. J. Genome-wide association analysis of agronomic traits in wheat under drought-stressed and non-stressed conditions. PloS One12, e0171692 (2017). 10.1371/journal.pone.0171692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas, G. & Sparks, D. Soil pH and soil acidity in methods of soil analysis. Chem. Methods5, 475–490 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hesse, P. R. & Hesse, P. A textbook of soil chemical analysis. (1971).

- 60.Gee, G. & Bauder, J. Particle-size analysis In: Klute, A.(ed) Methods of soil analysis, Part 1. American Society Agron.. (1986)

- 61.Helmke, P. A. & Sparks, D. Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium. Methods Soil Anal. Part Chem. Methods5, 551–574 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olsen, S. Anion resin extractable phosphorus. Methods Soil Anal.2, 423–424 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kjeldahl, C. A new method for the determination of nitrogen in organic matter. Z. Anal. Chem.22, 366 (1883). 10.1007/BF01338151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zadoks, J. C., Chang, T. T. & Konzak, C. F. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res.14, 415–421 (1974). 10.1111/j.1365-3180.1974.tb01084.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Long, S. & Bernacchi, C. Gas exchange measurements, what can they tell us about the underlying limitations to photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot.54, 2393–2401 (2003). 10.1093/jxb/erg262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil39, 205–207 (1973). 10.1007/BF00018060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deshmukh, P. S. & Shukla, D. S. Measurement of ion leakage as a screening technique for drought resistance in wheat genotypes. Indian J. Plant Physiol.34, 89–91 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amani, I., Fischer, R. & Reynolds, M. Canopy temperature depression association with yield of irrigated spring wheat cultivars in a hot climate. J. Agron. Crop Sci.176, 119–129 (1996). 10.1111/j.1439-037X.1996.tb00454.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joshi, A. K. et al. Staygreen trait: Variation, inheritance and its association with spot blotch resistance in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica153, 59–71 (2007). 10.1007/s10681-006-9235-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Randhawa, H. S. et al. Rapid and targeted introgression of genes into popular wheat cultivars using marker-assisted background selection. PloS one4, e5752 (2009). 10.1371/journal.pone.0005752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scientific, T. F. (Wilmington, Delaware, USA, 2014).

- 72.Scott, R. & Milliken, G. A SAS program for analyzing augmented randomized complete-block designs. Crop Sci.33, 865–867 (1993). 10.2135/cropsci1993.0011183X003300040046x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Asana, R. D. & Williams, R. F. The effect of temperature stress on grain development in wheat. Aust. J. Agric. Res.16, 1–13 (1965). 10.1071/AR9650001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Somers, D. J., Isaac, P. & Edwards, K. A high-density microsatellite consensus map for bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theo. App. Genet.109, 1105–1114 (2004). 10.1007/s00122-004-1740-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu, K. & Muse, S. V. PowerMarker: An integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformat.21, 2128–2129 (2005). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genet.155, 945–959 (2000). 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol.14, 2611–2620 (2005). 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rohlf, F. J. NTSYS-pc: Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System, Version 2.1 Exeter Software (Setauket, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perrier, X., Flori, A. & Bonnot, F. Data analysis methods. Genet. Div. Cul. Trop. Plants43, 76 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rambaut, A. FigTree. Tree figure drawing tool. (2009). http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- 81.Bradbury, P. J. et al. TASSEL software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinform.23, 2633–2635 (2007). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Breseghello, F. & Sorrells, M. E. Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genet.172, 1165–1177 (2006). 10.1534/genetics.105.044586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu, J. et al. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat. Genet.38, 203–208 (2005). 10.1038/ng1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Asseng, S. et al. Rising temperatures reduce global wheat production. Nat. Clim. Change5, 143–147 (2015). 10.1038/nclimate2470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nuttall, J. G., Barlow, K. M., Delahunty, A. J., Christy, B. P. & O’Leary, G. J. Acute high temperature response in wheat. Agron. J.110, 1296–1308 (2018). 10.2134/agronj2017.07.0392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kumar, P. V. et al. Sensitive growth stages and temperature thresholds in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for index-based crop insurance in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. J. Agric. Sci.154, 321–333 (2016). 10.1017/S0021859615000209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tack, J., Barkley, A. & Nalley, L. L. Effect of warming temperatures on US wheat yields. Proceed. Nat. Acad. Sci.112, 6931–6936 (2015). 10.1073/pnas.1415181112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Posch, B. C. et al. Exploring high temperature responses of photosynthesis and respiration to improve heat tolerance in wheat. J. Exp. Bot.70, 5051–5069 (2019). 10.1093/jxb/erz257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mondal, S. et al. Earliness in wheat: A key to adaptation under terminal and continual high temperature stress in South Asia. Field Crops Res.151, 19–26 (2013). 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.06.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ahmad, M. et al. Response of bread wheat genotypes to cell membrane injury, proline and canopy temperature. Pak. J. Bot.51, 1593–1597 (2019). 10.30848/PJB2019-5(22) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xin, G. et al. Correlation analysis of canopy temperature and yield characteristics of one Xinjiang spring wheat RIL under different irrigation conditions. Xinjiang Agric. Sci.58, 1961 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ullah, A., Al-Busaidi, W. M., Al-Sadi, A. M. & Farooq, M. Bread wheat genotypes accumulating free proline and phenolics can better tolerate drought stress through sustained rate of photosynthesis. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nut.22, 1–12 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li, C. et al. Comparison of photosynthetic activity and heat tolerance between near isogenic lines of wheat with different photosynthetic rates. PloS One16, e0255896 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0255896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morales, F. et al. Photosynthetic metabolism under stressful growth conditions as a bases for crop breeding and yield improvement. Plants9, 88 (2020). 10.3390/plants9010088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qaseem, M. F., Qureshi, R., Shaheen, H. & Shafqat, N. Genome-wide association analyses for yield and yield-related traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under pre-anthesis combined heat and drought stress in field conditions. PloS One14, e0213407 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0213407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kumar, A. et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of heat shock protein family reveals role in development and stress conditions in Triticum aestivum L. Sci. Rep.10, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qingyu, X. et al. Nutritional quality evaluation of different rice varieties based on principal component analysis and cluster analysis. China Rice28, 1 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 98.Satturu, V., Lakshmi, V. I. & Sreedhar, M. Genetic variability, association and multivariate analysis for yield parameters in cold tolerant rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Vegetos.36, 1–10 (2023). 10.1007/s42535-022-00501-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khan, A., Ahmad, M., Shah, M. K. N. & Ahmed, M. Performance of wheat genotypes for Morpho-Physiological traits using multivariate analysis under terminal heat stress. Pak. J. Bot.52, 1981–1988 (2020). 10.30848/PJB2020-6(30) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Belay, G. A., Zhang, Z. & Xu, P. Physio-morphological and biochemical trait-based evaluation of Ethiopian and Chinese wheat germplasm for drought tolerance at the seedling stage. Sustain.13, 4605 (2021). 10.3390/su13094605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paderewski, J., Gauch, H. G., Mądry, W., Drzazga, T. & Rodrigues, P. C. Yield response of winter wheat to agro-ecological conditions using additive main effects and multiplicative interaction and cluster analysis. Crop Sci.51, 969–980 (2011). 10.2135/cropsci2010.05.0278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arain, S. M., Sial, M. A., Jamali, K. D. & Laghari, K. A. Grain yield performance, correlation, and luster analysis in elite bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) lines. Acta Agrobot.71 (2018).

- 103.Vasumathy, S. K. & Alagu, M. SSR marker-based genetic diversity analysis and SNP haplotyping of genes associating abiotic and biotic stress tolerance, rice growth and development and yield across 93 rice landraces. Mol. Biol. Rep.48, 5943–5953 (2021). 10.1007/s11033-021-06595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Delfini, J. et al. Population structure, genetic diversity and genomic selection signatures among a Brazilian common bean germplasm. Sci. Rep.11, 1–12 (2021). 10.1038/s41598-021-82437-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang, Y. et al. Collection and evaluation of genetic diversity and population structure of potato landraces and varieties in China. Front. Plant Sci.10, 139 (2019). 10.3389/fpls.2019.00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]