Abstract

BACKGROUND:

There are few published studies to guide the treatment of carcinoma metastatic to the neck from an unknown primary (CUP). In this regard, the goal of this study was to share our experience treating patients with CUP with Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), which principally targeted the bilateral necks and naso- and oro- pharynx.

METHODS:

This is a retrospective study in which an institutional database search was conducted to identify patients with CUP treated with IMRT. Data analysis included frequency tabulation, survival analysis and multivariable analysis.

RESULTS:

Two-hundred sixty patients met inclusion criteria. The most common nodal category was N2b (54%). IMRT volumes included the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa in 78 patients, the naso-and oro-pharynx in 167, and treatment limited to the involved neck in 11. Neck dissections were performed in 84 patients. The 5-year overall survival, regional control and distant metastases free survival rates were 84%, 91% and 94%, respectively. Over 40% of patients had gastrostomy tubes during therapy, and 7% patients were diagnosed with chronic radiation-associated dysphagia. Higher nodal burden was associated with worse disease-related outcomes, and in subgroup analysis, patients with human papillomavirus-associated disease had better outcomes. No therapeutic modality was statistically associated with either disease related outcomes or toxicity.

CONCLUSIONS:

Comprehensive IMRT with treatment to bilateral necks and the oro- and naso-pharyngeal mucosa results in high rates of disease control and survival. We were unable to demonstrate that treatment intensification with chemotherapy or surgery added benefit or excessive toxicity.

Keywords: Unknown Primary Neoplasms, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy, Head and Neck Neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP) accounts for approximately 3% of head and neck (HN) cancer diagnoses1, with the majority being squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). Owing to this relatively low incidence of HNCUP, there is a dearth of strong evidence-based guidance for management. Thus, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are relatively broad 2, recommending surgery (with adjuvant therapy as indicated by the surgical findings), radiation, or systemic therapy and radiation. Guidelines regarding the specifics of radiation are also vague, particularly with regards to treatment volumes. NCCN guidelines recommend treating “sites of suspected subclinical spread”, based on primary nodal drainage patterns and subsequent risk of recurrence, and advocate irradiating “putative mucosal sites” although others favor treating the involved neck only3, 4.

Based on work by Jesse and Fletcher 5 at The University of Texas MD Anderson analyzing patterns of mucosal and regional recurrence, when radiation was to be used, coverage of both sides of the neck, and the entire pharyngeal axis and larynx was recommended with few exceptions. Subsequent analyses validated the approach 6, 7 with regards to a low incidence of mucosal and regional relapse, though a modest incidence of late swallowing toxicity as well as high rates of xerostomia were noted. In one of the largest series on CUP, Grau et al. validated that treatment to both sides of the neck and the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa resulted in lower rates of disease recurrence and a suggestion that patients treated with this comprehensive approach had better survival expectations that those treated with radiation to the involved neck only 8. While the authors recommended a prospective trial to address the appropriate volumes to irradiate in patients with CUP, and an international multiinstitutional cooperative trial was planned 9, the trial was never conducted.

Frank et al 10 reported our initial experience using intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). We began using this technology in the early 2000’s for patients with HNCUP to ideally capitalize on xerostomia reduction that IMRT can achieve, while still delivering comprehensive radiation to both sides of the neck and pharyngeal mucosa. At that time we were not fully aware of the implications of disease associated with human papilloma virus (HPV), but we subsequently began to modify our treatment by omitting coverage of the larynx and hypopharynx in non-smokers, In the 52 patients treated through 2005, disease control rates were very high, and the toxicity profile was very encouraging.10

Subsequent to this initial experience our radiation approach for patients with HNCUP has remained fairly comprehensive. However, as we increasingly encountered patients with limited smoking and/or HPV-associated disease, as well as performing more comprehensive evaluations (including PET, examinations under anesthesia, and adequate examination of the thin mucosa in the larynx and hypopharynx assuring that there was no primary tumor), we more frequently omitted the larynx and hypopharynx from our treatment fields. Additionally, as many patients presented with a significant nodal burden with increased risk of extracapsular extension, there was an increased interest in the integration of systemic therapies into our approach.

To this end, we undertook the current retrospective study to update our experience of IMRT for patients with HNCUP. In particular, we wanted to:

-

1-

Identify patient and treatment parameters associated with oncologic outcomes of interest;

-

2-

Investigate the outcomes of radiation monotherapy vs. combination approaches involving surgery and/or chemotherapy for HNCUP;

-

3-

Evaluate outcomes based on the degree of mucosal coverage; and

-

4-

Identify toxicity profiles for HNCUP in the modern treatment era.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics

This is a retrospective analysis of patients with cervical nodal SCC metastases from CUP, who underwent IMRT in the Department of Radiation Oncology at UT MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2000 through 2015. The study was conducted under an institutional review board–approved protocol.

All patients had a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of metastatic cervical nodal SCC without an identified mucosal primary tumor. Individuals with a known diagnosis of SCC of the skin either prior to or concurrent with the nodal presentation, for which the nodes were consistent with metastatic spread from skin cancer, were excluded. The medical records of patients were reviewed to assess patients’ demographic, clinical, radiologic and pathologic data. All patients were restaged retrospectively using criteria of the 7th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system.

Radiotherapy Treatment

IMRT was delivered using a linear accelerator producing 6-MV photons. The initial IMRT planning system, Corvus system (North American Scientific, Inc., Cranberry Township, PA) was used from 2000 – 2003; in 2003 we transitioned to the Pinnacle planning system (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA).

Treatment was delivered with a static gantry approach. The IMRT fields generally consisted of nine static gantry beams with the following angles: 0, 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240, 280, and 320 for patients treated to both sides of the neck and 7 beams equidistant through a 190° arc for patients treated to only 1 side of the neck. General treatment strategies included defining three clinical target volumes (CTVs). CTV1, included gross nodal disease with a margin, or in postoperative situations the preoperative tumor bed with margin. A virtual gross target volume (GTV) was created for patients treated with chemotherapy prior to radiation, and margins similar to patients with true GTVs were added to create CTV1 in this setting. CTV2, was a neck volume at high risk of harboring microscopic disease but without clinical, radiographic or pathologic evidence of nodal disease; and CTV3, was the nodal volume and mucosa deemed at low risk of harboring subclinical disease. Nodal levels 1–5 were treated in the node positive neck, and nodal levels 2–4 were treated when the node negative neck was treated. The retropharyngeal nodes were treated. All CTVs were treated simultaneously, with fractional doses ranging from 1.7 −2.2 Gy dependent on the number of fractions and total dose prescribed to each respective CTV.

During this 15 year time frame, we used 2 separate IMRT techniques. The first, colloquially referred to as “split field”, treated the mucosa and upper neck with IMRT, while the lower neck was treated with an appositional photon field. When using the split field technique in patients for whom only the naso- and oropharyngeal mucosal was treated, the inferior extent of the IMRT portals was 1–2 cm inferior to the hyoid. The lower neck field had a “larynx block” which shielded the glottic and subglottic larynx as well as the adjacent hypopharynx. The epiglottis within the IMRT portals was not included in the CTV nor was delineated as an avoidance structure. For those patients treated with split field and who had the larynx and hypopharynx included, level 3 nodes were also included in the IMRT field. The junction was at the inferior aspect of the cricoid cartilage, and the low neck field had a small central block at the superior border to avoid excess dose to the spinal cord at the junction.

In whole field IMRT, if treatment was limited to the naso- and oropharyngeal mucosa, the larynx and adjacent hypopharynx were delineated as an avoidance structure. The superior border for this avoidance was at the superior aspect of the thyroid cartilage.

Statistical Analyses

Studied parameters included patient and tumor characteristics, management data, response to treatment and patient survival. The chi-square test was used to determine statistical significance of association between clinic-pathologic variables. Binary logistic regression was used to test the relationship between continuous variables and binary responses. Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the probabilities of local, regional, and distant disease control and disease-specific and overall survival (OS). Patients who had gross neck disease at the time of their radiation, and either did not have a post-treatment radiographic reevaluation or had a radiographic evaluation that revealed persistent disease were coded as neck recurrence for the purpose of statistical analysis. However, patients who had neck dissection within the first 6-months following radiation without evidence of new nodal disease and with no subsequent recurrence were not considered to have regional recurrence in this analysis, even if the neck dissection specimen had evidence of microscopic disease.

Comparisons between survival curves were made using the log-rank test. Multivariable analysis was performed with the Cox Proportional Hazards model. A forward selection technique was used, with variables having a p-value < 0.1 included in the model. For continuous variables with significant association with outcome endpoints, recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was done to identify optimal cutoff points. For comparison of model performance when adding nodal stage, or size of largest lymph node to the base model without nodal staging or size information, we used Bayesian information criterion (BIC). A lower BIC indicates improved model performance and parsimony, using the BIC evidence grades presented by Raftery11 with the posterior probability of superiority of a lower BIC model based on the difference of tested model and the base model. All analyses were performed using JMP Pro statistical software version 11.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Toxicity tabulation included feeding tube (gastrostomy) use, and chronic radiation-associated dysphagia (RAD). RAD was defined as having any of the following more than one year from radiation: videofluoroscopy/endoscopy detected aspiration or stricture, gastrostomy tube and /or aspiration pneumonia12. Grade 3 or greater osteoradionecrosis (ORN) events were also recorded.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Nodal Characteristics

Two hundred sixty- patients met the inclusion criteria; 221 were male and 39 were female (6:1). The median age was 58 years (range: 19–84 years). The majority of patients had N2b disease (141, 54%) with the nodal stage distribution listed in Table 1. One hundred thirty -six patients had node(s) confined to one cervical nodal level (52%), and 123 patients (47%) had nodes at multiple levels.

Table 1:

Patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 221 (85) |

| Female | 39 (15) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 58 |

| Range | 19–84 |

| Smoking Status | |

| Current | 88 (34) |

| Former | 91 (35) |

| Never | 77 (30) |

| Unknown | 5 (1) |

| Alcohol status | |

| Current | 160 (61) |

| Former | 30 (12) |

| Never | 60 (24) |

| Unknown | 11 (4) |

| Methods of diagnosis | |

| Fine needle aspiration | 119 (46) |

| Excisional biopsy | 119 (46) |

| Core biopsy | 22 (8) |

| Tonsillectomy | |

| Yes | 143 (55) |

| No | 113 (43) |

| Unknown | 5 (1.88) |

| Lymph Node Staging | |

| Nx | 1 (<1) |

| N1 | 25 (10) |

| N2a | 40 (15) |

| N2b | 141 (54) |

| N2c | 31 (12) |

| N3 | 22 (8) |

| Size of the largest Lymph Node, mean, range (cm) | 3.2 (0.8–12) |

| Number of involved neck levels | |

| 1 | 136 (52) |

| ≥2 | 123 (47) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) |

| Solitary Lymph Node | |

| Yes | 69 (27) |

| No | 190 (73) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) |

Diagnosis was made by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) in 119 patients (46%), excisional biopsy in 119 (46%), and core biopsy in 22 (8%). All patients had at least one examination under anesthesia, 184 (71%) had a PET as part of the radiologic workup, and 143 (55%) had tonsillectomy.

Forty-two patients (16%), 20 diagnosed by FNA, and 22 by biopsy had subsequent surgical neck dissections prior to radiation treatment (Table 1). Twenty one of these 42 patients (50%) presented to our center following their neck dissection. The documentation of the number of pathologically involved nodes found at neck dissection was available for 39 patients. Nineteen had a solitary node, 14 had 2–3 nodes and 5 had > 3 nodes (range: 4–14). One patient had a negative neck dissection following diagnosis and induction chemotherapy.

Forty-five of 144 patients who had either excisional biopsy or neck dissection, had nodal extracapsular extension (ECE).

Radiation Treatment

Seventy-nine patients (30%) who presented with either excisional biopsy or neck dissection had no gross disease at the time of radiation. The median prescribed dose of radiation to CTV1 in these patients was 60 Gy (range: 60– 66 Gy). The median prescribed dose of radiation to CTV1 of the remaining 181 patients with gross disease was 66 Gy (range: 63 – 72 Gy). All but 2 patients completed treatment as prescribed. Radiation treatment was delivered to putative mucosal primary sites in 245 patients (94%). The entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa was treated in 78 (30%) patients, while the nasopharynx and oropharynx, excluding the hypopharynx and larynx were treated in 167 (63%). The choice of the extent of mucosal treatment evolved over the years of the study. Fifty-four patients (44%) treated prior to 2009 had treatment to the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa, compared with 24 patients (17%) treated since 2009. Putative mucosal primary sites were treated to a median planned doses of 54 Gy (range: 50– 66 Gy). Only 6 patients received ≥60 Gy, and 75% were planned to 54 Gy.

Eleven (4%) patients, had treatment to the involved neck with no directed attempt at treating mucosal sites. The reasons for not treating the mucosa in these patients were: nodal location 7 patients, large volume N3 disease, 2 patients and poor performance status, 2 patients. Among the 7 patients for whom nodal location influenced the decision, 3 had substantial level 1 disease, and 4 had significant nodal burden in level 4 and the supraclavicular fossa. Specifics of radiation sites treated were missing in 4 patients.

While all patients were treated by IMRT to the upper neck (and mucosal sites in 245 patients), 176 (69%) were treated by split field and 80 (31%) patients had the entire volume treated with IMRT (whole field). Among those treated to bilateral necks and naso- and oropharyngeal mucosa, 148 (89%) were treated with split field while for those treated to the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa, 24 were treated with split field (31%).

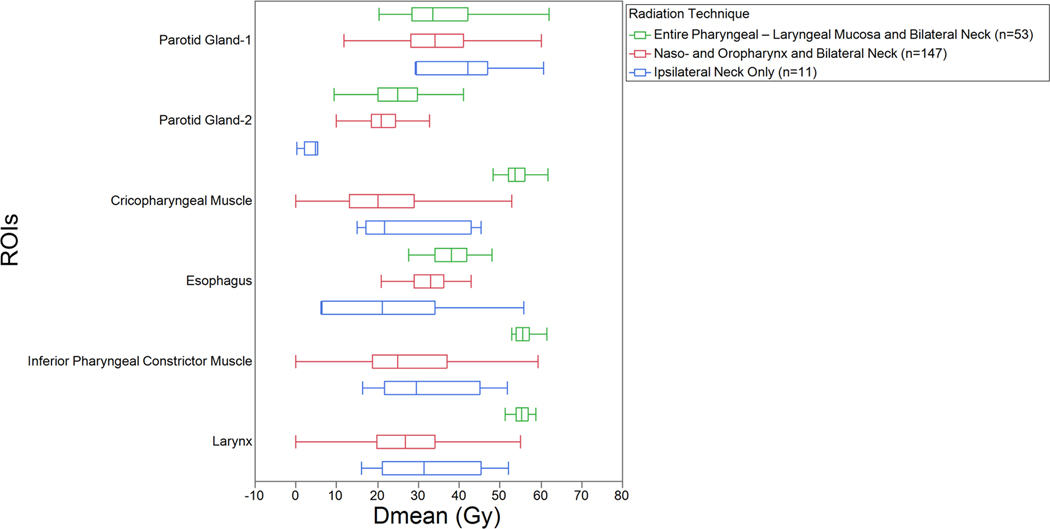

Mean doses for several normal tissues are demonstrated graphically in Figure 1. Dose-volume histograms (DVHs) were only available for 211 patients. The main avoidance structures throughout the time frame of the study were the parotid glands. The superior and middle constrictor muscles received the dose prescribed to the mucosa.

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plots of Dmean (mean dose) for ROIs (regions of interest), grouped by the 3 radiation techniques. For each patient, Parotid Gland-1 is the parotid gland that received the higher dose, and Parotid Gland-2 is the gland that received the lower dose.

Chemotherapy Treatment

Sixty-three patients (24%) received induction chemotherapy; 47 patients were treated with taxane-platinum based induction chemotherapy, and 15 were treated with platinum and cetuximab, The specifics of induction chemotherapy was missing in one patient (Table 2). Sixty-two of these 63 patients (98%) had N2b or higher disease at presentation.

Table 2:

Treatment characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Pre-RT Neck Dissection | |

| Yes | 44 (17) |

| No | 213 (82) |

| Type of pre-RT Neck Dissection * | |

| Selective | 18 (41) |

| Modified | 17 (39) |

| Radical | 6 (13) |

| Not Specified | 3 (87) |

| IMRT Technique | |

| Split | 180 (69) |

| WF-IMRT | 80 (31) |

| Mucosal site targeted | |

| Entire Pharyngolaryngeal Mucosa | 78 (30) |

| Naso-, Oro-pharynx | 167 (64) |

| Mucosa Not Targeted | 11 (4) |

| Not Specified | 4 (2) |

| Overall Radiation treatment time (IQR, days) | 41 (39–43) |

| Induction chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 63 (24) |

| No | 197 (76) |

| Type of Induction chemotherapy * | |

| Taxane+ Platinum Based | 47 (75) |

| Platinum+ Cetuximab Based | 15 (24) |

| Not specified | 1 (<1) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy * | |

| Yes | 65 (25) |

| No | 195 (75) |

| Type of Concurrent chemotherapy * | |

| Taxane+ Platinum Based | 2 (3) |

| Cisplatin | 29(45) |

| Carboplatin | 18(28) |

| Cetuximab | 12 (18) |

| Not Specified | 4 (6) |

Abbreviations

RT: Radiation Therapy; IMRT: Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy; WF-IMRT: Whole field- Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy; IQR: Interquartile Range.

percentages of those that received the specified treatment

Sixty-five patients received concurrent chemotherapy (25%); 63/65 (97%) were treated with a single concurrent drug and 2 received a taxane-platinum doublet (Table 2). Forty-seven patients had N2 disease and 14 had N3 disease. Sixteen of the 44 patients (36%) who had nodal ECE received concurrent chemotherapy. Forty-four of the 181 patients with gross nodal disease (24%) received concurrent chemotherapy including 8 of the 11 patients (67%) who had radiation only to the neck. Twenty patients who received concurrent therapy also received induction therapy. Among the 58 patients who received concurrent chemotherapy and mucosal irradiation, 12 had treatment that included the larynx and hypopharynx.

Post-Radiation Neck Dissections

Forty-two patients (23% of the 181 irradiated with gross adenopathy) underwent neck dissection after IMRT at 1–5 months post-radiation. Three patients underwent a planned neck dissection (having received 63–66 Gy to CTV1), and the remaining 39 patients had post treatment clinical and radiographic findings concerning for residual disease. Ten patients (10/42, 24%) had pathologic evidence of residual carcinoma.

Outcomes

Two hundred five (79%) patients were alive at last contact. The median follow-up for surviving patients was 61 months (range: 0 to 176 months). Thirty-one living patients (14%) had follow-up of less than two years.

Overall Survival

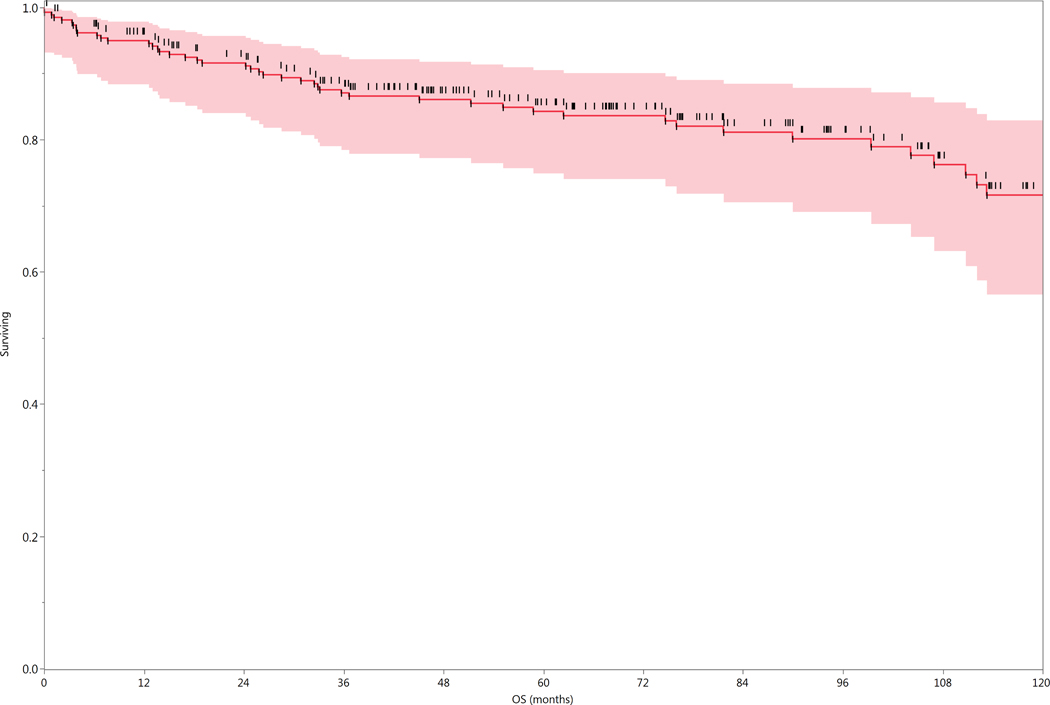

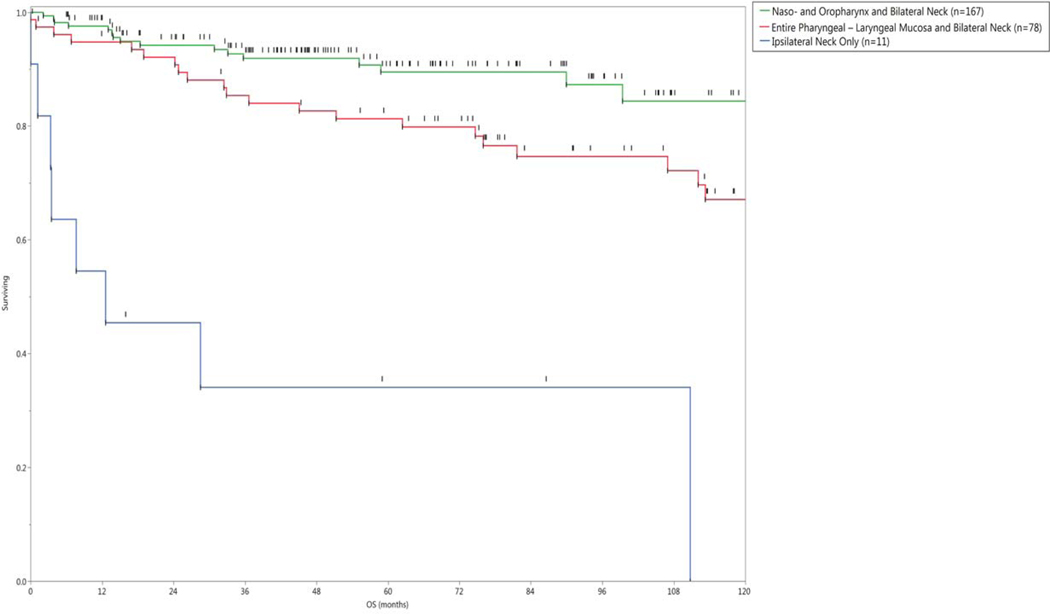

Fifty-five patients (21%) were dead at the time of analysis; 28 had evidence of disease at the time of death. Forty-five of the 55 patients who died presented with N2b disease or greater, including 10 of the 22 patients who presented with N3 disease. The 2-, 5-, and 10-year actuarial overall survival (OS) rates for the entire cohort of 260 patients were 92%, 84%, and 72%, respectively (Figure 2). Overall survival and recurrence free survival rates subgrouped by radiation technique are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Actuarial Overall Survival of entire cohort (n=260).

Figure 3.

a) Actuarial Overall Survival, and b) Recurrence-free survival grouped by radiation technique.

In multivariate analysis, the OS rate was negatively associated with older age (p <0.0001), and treatment to the neck only (p = 0.02). As there were only 11 patients treated to the neck only, the model was rerun without this variable. Only older age was significant in the new model.

There were no statistical differences in survival between patients who had neck dissections versus those that did not. Analyses included all patients who had neck dissections, as well as separate analyses limited to patients with pre-IMRT dissections and post-IMRT dissections. An analysis of patients who were irradiated without evidence of gross nodal disease (including patients with pre-IMRT neck dissections or excisional biopsies) compared to those that did have nodal disease, did reveal an improved survival rate for the former as comparative 5- year OS rates were 92% versus 82%, respectively (p= 0.02). However, this variable was not significant in the multivariate analysis (p= 0.45).

No OS differences were observed with the use of either concurrent or induction chemotherapy. As induction chemotherapy was used almost exclusively for patients with higher nodal burden, a subgroup analysis limited to patients with N2b disease or greater was performed, and did not reveal any differences.

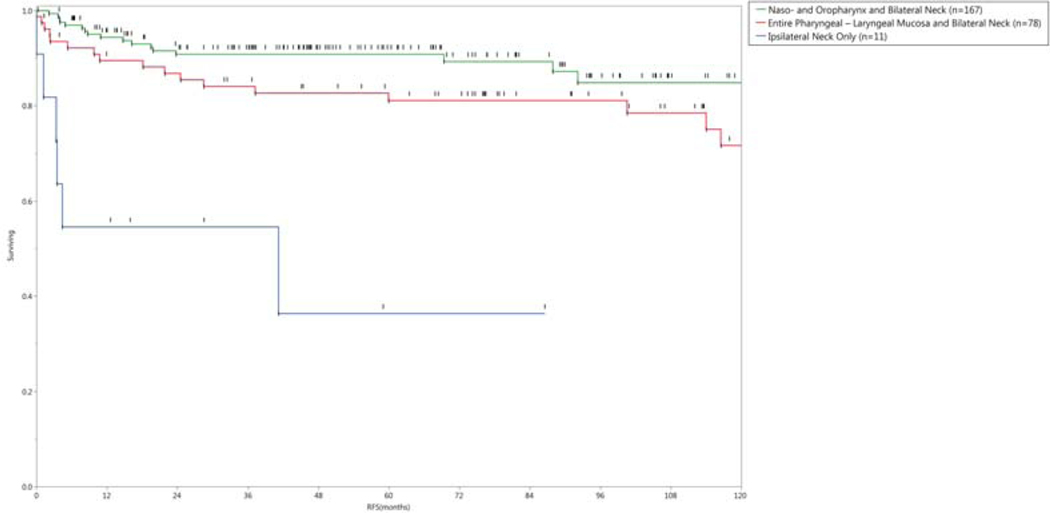

Neck Control

Twenty-four patients (9%) had recurrent or persistent disease in the neck. The actuarial 2- and 5- year neck control rates were 92%, and 91%, respectively. Twenty-one patients developed neck recurrence in CTV1, 2 in CTV2 and 1 in the unirradiated contralateral neck.

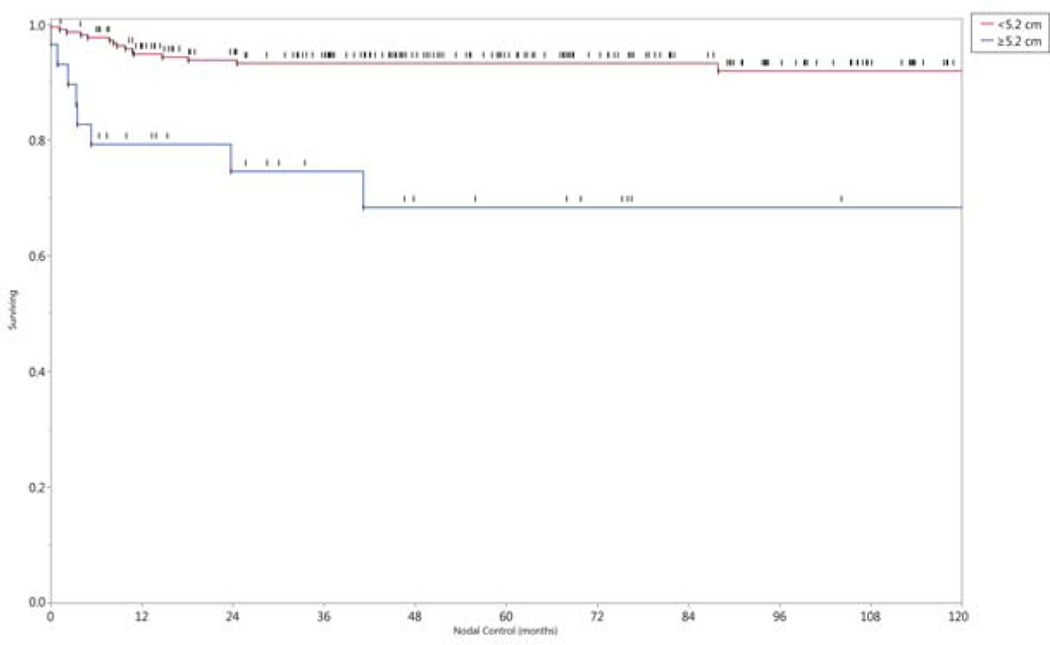

In univariate analysis, the neck control rate was negatively associated with older age (p <.01), females (p < 0.01), and larger nodal burden. The latter was analyzed by several features including: nodal category (Nx, 1–2a vs N2b-3, p= 0.015), size of the largest lymph node as a continuous variable (p= 0.0015), size of the largest lymph node as either ≥5.2cm or <5.2 cm, p=0.001), or nodal multiplicity (solitary vs multiple nodes, p = 0.05). The 5- and 10- year nodal control rate by lymph node stage and size of the largest lymph node affected are shown in Figure 4. Twenty-two of the 24 patients (92%) who developed neck recurrences originally presented with N2b disease or greater. All variables statistically significant in univariate analysis maintained statistical significance (p< 0.05) in multivariate regression. There was no statistical association between the number of involved nodal levels (one vs multiple), nor the location of the involved lowest level and regional failure.

Figure 4.

Nodal control rates grouped by a) nodal category, and b) size of the largest lymph node in centimeters.

Distant Metastases

The 2-, 5, and 10-year actuarial distant metastases free survival (DMFS) rates were 95 %, 94%, and 90%, respectively. Sixteen patients (6%) developed distant metastases. The most common site was the lung (9/16, 56% patients). Eleven patients (11/16, 69%) had isolated distant disease without evidence of disease above the clavicles. Original nodal staging in these 16 patients was: N2b, 13 patients, and N3, 3. Four patients had disease in Level IV /V nodes. Univariate analysis revealed that older age, female sex, and increased nodal burden were significantly associated with a higher rate of distal failure. In multivariate analysis, the higher distant failure rate was associated with being female (p < 0.01).

Primary Tumor Development

Fourteen patients (5%) manifested a primary tumor. Ten tumors developed in a head and neck mucosal site. Five cancers were in the oropharynx, 3 in larynx, 1 in the nasopharynx and 1 in the oral cavity. Eight of these 10 patients, including 6 who were treated to the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa developed mucosal primary tumors within targeted radiated mucosal sites. Of the three patients who developed laryngeal cancer, only one had his larynx included in the mucosal coverage. Only 3 of the 178 patients (1%) treated to bilateral necks and naso-oropharyngeal mucosa developed a primary tumor. There were 4 non-mucosal primary tumors; 1 arose in the skin of the chest wall, 1 was diagnosed as a primary squamous cell of the ipsilateral parotid and 2 were squamous cell lung carcinoma. It is feasible that the latter 3 were metastases rather than primary lesions. Seven of these 14 primary tumors occurred within the first 2 years of follow-up, while 5 developed after more than 5 years from treatment.

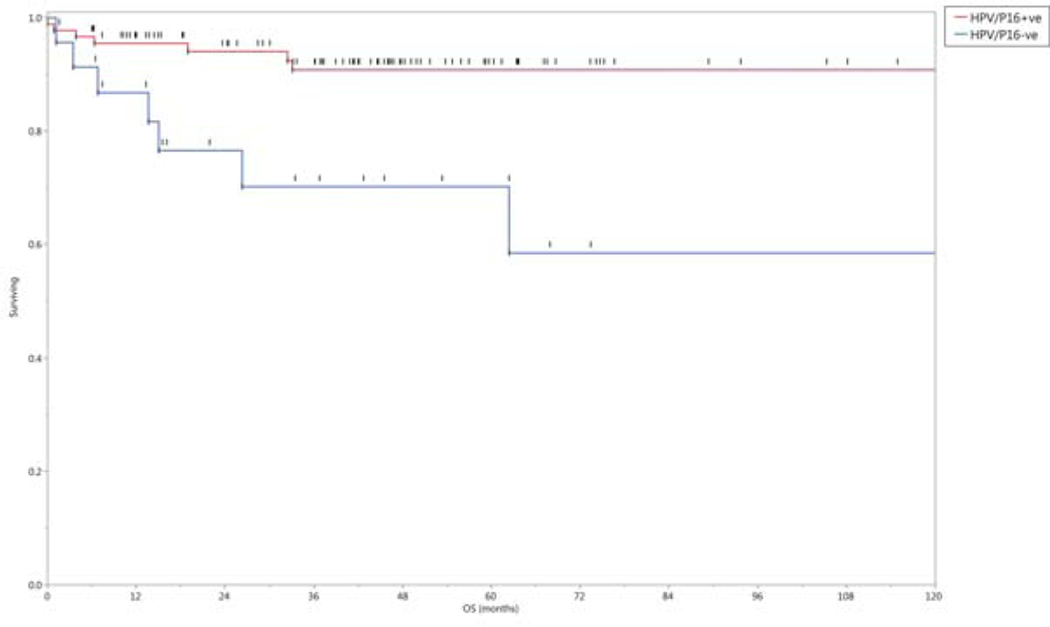

HPV/P16 subgroup analysis

HPV/P16 status was known for 113 patients. HPV- association was considered positive if either HPV or p16 testing was positive. Ninety patients had HPV-associated disease and 23 did not. Five HPV- negative patients had N3 disease. Only 12% and 17% of patients with HPV- positive and negative disease, respectively had the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa treated, and 87% of HPV- positive patients had treatment to the naso- and oropharynx. Patient and treatment characteristics for patients with known HPV/P16 status are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3:

Patient, disease and treatment characteristics in patients with known HPV/P16 status

| Characteristics | HPV/P16 +ve (90) No. (%) | HPV/P16 -ve (23) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 79 (88) | 15 (65) |

| Female | 11 (12) | 8 (35) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 57 | 60 |

| Range | 38– 83 | 26– 84 |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Current | 16 (18) | 8 (36) |

| Former | 41 (48) | 9 (41) |

| Never | 29 (34) | 5 (23) |

| HPV Status (ISH) | ||

| Positive | 82 (91) | 0 |

| Negative | 8 (9) | 22 (95) |

| P16 (IHC) | ||

| Positive | 84 (93) | 0 |

| Negative | 2 (2) | 23 (100) |

| Lymph Node Staging | ||

| N1 | 7 (8) | 1 (4) |

| N2a | 11 (12) | 1 (4) |

| N2b | 60 (66) | 11 (48) |

| N2c | 5 (6) | 5 (22) |

| N3 | 7 (8) | 5 (22) |

| Mucosal site targeted | ||

| Entire Pharyngolaryngeal Mucosa | 11 (12) | 4 (17) |

| Naso-, Oro-pharynx | 78 (87) | 17 (74) |

| Mucosa Not Targeted | 1 (1) | 2 (9) |

| Induction chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 28 (31) | 7(31) |

| No | 62 (69) | 16 (69) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 26 (29) | 10 (43) |

| No | 64 (71) | 13 (57) |

| Treatment outcomes | ||

| Distant failures | 4 (4) | 4 (17) |

| Neck failures | 5 (5) | 6 (26) |

| Primary developed in HN mucosa | 3 (3) | 1 (4) |

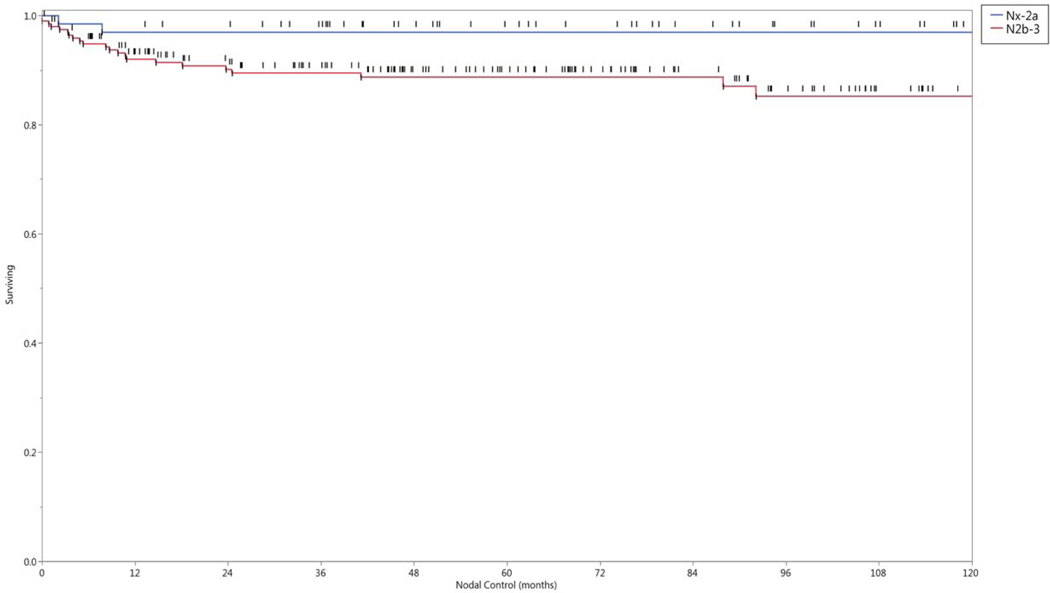

HPV- positive patients had improved rates of OS (p= 0.002), neck control (p= 0.035) and DMFS (p= 0.047). The 5-year actuarial rates of OS, neck control and DMFS were 91%, 94% and 95%, respectively for HPV-positive patients, and 70%, 73%, and 77%, respectively for HPV- negative patients, Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Overall survival rates grouped by tumor HPV/p16 status.

Toxicities

One hundred eight patients (42%) had a percutaneous gastrostomy tube placed either prior to or during radiation treatment. Ninety-five (88%) had their tubes removed by 6 months post completion of radiation. There were no significant differences in the incidence of gastrostomy placement in patients who received treatment to the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa compared with those who had only partial pharyngeal treatment (p= 0.8), nor were there differences in gastrostomy rates between patients who did or did not receive concurrent systemic therapy (p= 0.3).

Eighteen patients (7%) had chronic radiation associated dysphagia (RAD) 12 at last follow- up, including 10 patients who still had gastrostomy tubes. Of the 18 patients with chronic RAD, 8 (5%) were treated to the oro- and nasopharynx, while 10 (13%) were treated to the entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa (p= 0.2). There was no difference in the incidence of chronic RAD in patients who did or did not get concurrent chemotherapy.

Five patients (2%) developed osteoradionecrosis of the mandible requiring surgical intervention.

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to update a preliminary analysis of 52 patients diagnosed with HNCUP and treated with comprehensive IMRT. The current study, consisting of 260 patients with over 5 years median follow-up confirmed excellent disease-related outcomes with 5- year nodal control, distant metastases-free survival and OS rates of 91%, 94%, and 84%, respectively, despite more than 57% of the cohort having advanced-stage nodal disease at presentation. Additionally, with an approach of using comprehensive radiation that included treatment of putative mucosal sites, only 4% subsequently developed a head and neck mucosal tumor. This low rate of primary tumor development was achieved even after omitting the larynx and hypopharynx in the majority of cases.

The excellent oncologic outcomes in our patients with HNCUP treated with IMRT are consistent with those reported in many other small series 1, 13–16. Patients in these series were also typically treated to mucosal sites. The large number of patients in our cohort along with the relatively long follow-up should add to the confidence that excellent disease control can be achieved with comprehensive radiation for HNCUP. Further, the survival rates reported in this study are similar to our patients with known disease sites. Over the past decade in particular, the majority of our patients with oropharyngeal cancer have HPV- associated disease. Similarly, in patients for whom we had material for testing p16 and/ or HPV, 80% were positive. The 5-year OS for this subgroup was 90%, similar to the 84% seen in our oropharyngeal cancer patients 17.

To better explain our outcomes, we performed multivariate analysis. Older age was associated with worse OS, and increased nodal burden was associated with an increased rate of disease recurrence. In subgroup testing, also consistent with known findings, patients with HPV associated disease fared better. One surprising finding was the poorer outcome of female patients. Other than the vagaries of statistical analysis, we cannot offer an explanation for this finding.

One aim of the study was to assess the impact of other therapies (surgery and chemotherapy) added to radiation. With regards to disease outcome, the use of pretreatment neck dissection did not correlate with disease recurrence. The role of neck dissection is controversial, and the existing literature does not give clear guidance that a neck dissection improves outcome1. Similar to our report, all series are retrospective and thus subject to selection bias. Further, particularly older series, do not account for the changing epidemiology and impact of an increase in patients with HNCUP having HPV-associated disease. Examples from the literature highlighting the controversy include reports by Wallace et al 18, and Aslani et al 19. The former demonstrated a significant improvement in neck control in those treated with pre-RT neck dissection compared with patients who had either a post-RT neck dissection or no neck surgery. The latter group did not detect a benefit to disease control in their patients who were operated. However, similar to our findings, regardless of treatment approach, nodal burden seemed to be the better predictor of outcome. Shoustari et al 14 reported a series of patients treated with pre-radiotherapy neck dissection. Disease control at 5-years for patients with non-bulky disease was 100% compared to 67% for those patients with large volume disease.

We also were not able to demonstrate a benefit to systemic therapy, neither neoadjuvant nor concurrent. Even restricting analysis of induction therapy to those whom we thought would be at higher risk of recurrence (N2b or higher), differences in outcomes were not observed. The lack of benefit of induction chemotherapy is consistent with recent reports in head and neck cancer with known primaries 20, 21 while the lack of benefit of concurrent therapy appears contrary to a benefit observed in prospective, randomized studies in HN cancer with known primaries 22. However, this body of evidence, while believed to reflect a benefit for all patients with Stage 3– 4b head and neck cancer, largely is based on patients with advanced T-disease. The vast majority of these studies principally accrued patients with T3–4 disease, often excluding patients with small primary tumors, and not recruiting patients with T0 (CUP). Thus the lack of a benefit in our trial may be due to the modest size and retrospective nature of the cohort, or a function of the statistics, wherein not disproving the null hypothesis does not mean it is true. However, it also may suggest that patients with small or non-detectable primary tumors, particularly with HPV-associated disease may not gain much benefit in disease control by the addition of chemotherapy to radiation. This concept has been recently tested by NRG (NRG HN-002), and results of this trial are eagerly awaited.

While there was no obvious benefit from the addition of systemic therapy, there was also no apparent excess toxicity, neither acute nor late. This is contrary to a report by Sher et al.23 Nearly all patients in that study were treated with mucosal radiation and concurrent chemotherapy. However, half the patients were treated with a platinum- taxane doublet. Anticipating toxicity, all patients receiving this treatment approach had prophylactic gastrostomy tubes, and 46% had late grade 3 esophageal toxicity. Whether this high rate of toxicity is related to the addition of chemotherapy or to the radiation techniques (including dose and volume) or both is speculative. However, we believe our lower rates of toxicity may be explained by almost only using a single agent of systemic therapy, only dosing the pharynx to 54 Gy, limiting the volume to include only the oropharynx and nasopharynx, minimizing the dose to the esophagus to ≤ 40 Gy, and proactive models of supportive care with avoidance of prophylactic gastrostomy.

Excluding the hypopharynx and larynx was a major change in our radiation approach. This change was based on the observation that more patients had limited smoking histories, and ultimately many of our patients had HPV-associated disease. The development of mucosal primary tumors remained uncommon with this change. The incidence of chronic RAD in patients treated to the oro- and nasopharyngeal mucosa was 5%. However we were unable to demonstrate that more aggressive therapy with larger fields led to increased toxicity.

Others have described limiting the irradiated mucosal volume. Wallace et al. described omitting the hypopharynx and larynx 18, and none of their 28 patients developed a mucosal primary. Mourad et al. reported an initial experience of 68 patients in whom they targeted only the oropharynx, bilateral retropharyngeal nodes and bilateral cervical nodes.24 Only one patient later developed a mucosal primary. As we also treat retropharyngeal nodes, and have seen evidence of HPV-associated nasopharyngeal cancer25, we still include the nasopharyngeal mucosa. We limit the elective radiation dose to 54 Gy (at 1.8 Gy per fraction), and believe this combination of only modest dose and more limited target volume results in limited late toxicity.

The major limitation of this work is its retrospective nature. However, for this uncommon presentation of head and neck cancer, stronger evidence based trials are non-existent. An international cooperative trial investigating the volume to irradiate9 was terminated due to extremely poor accrual. Our large series is consistent with disease-related outcomes reported in smaller trials with shorter follow-up. The retrospective nature though can lead to underreporting of events, particularly toxicity events, especially grade 1 xerostomia and dysphagia.

Ultimately, the optimal management of patients with CUP is similar to presentations of SCC of the head and neck with known mucosal sites. With regards to managing head and neck cancers, two basic questions exist. The first question is how to best control the disease we know, which in patients with CUP is solely the gross nodal disease. Our data suggests that radiation is an effective therapy, and gains in controlling this disease by the routine use of neck dissection and/ or systemic therapy are likely small, but similarly toxicity profiles are not greatly altered by additional therapies. We still consider a preoperative neck dissection for patients with low nodal burden (ie a solitary node without radiographic ECE), as if pathology confirms the clinical impression, neck dissection alone should suffice. Similar to controversies in oropharyngeal cancer, the need for the addition of concurrent chemotherapy in all cases remains unclear. We are more selective in patients who have had surgery, adding concurrent therapy only to patients with extensive ECE. In patients who present with gross disease, the nodal burden is influential in decision making, as we will still likely add a systemic agent in patients with N3 disease, patients with multilevel bulky disease, or patients with radiographic evidence of extensive ECE.

The second question is how necessary is it to treat disease that is not clearly evident, and even may not exist. This question mainly relates to the volume to irradiate. Our approach has been relatively aggressive, treating mucosal sites and uninvolved regions of the neck. This approach was successful, with few patients developing disease outside of the radiation-targeted tissues. Late toxicity was not excessive, but even in the best case, there still was an approximate 5% rate of severe late effects, and over 40% of patients required gastrostomy tube use for up to 6 months. The alternative is to limit the treatment to the involved neck only. Studies have suggested that with regards to survival, neck only therapy is as effective as more comprehensive radiation.3, 4, 9 However, balancing an increased risk of disease recurrence versus a lower toxicity profile remains a complex question in this era when much of the research is in discovering less toxic and ideally non-inferior therapies.

In conclusion we report on 260 patients irradiated with IMRT for CUP, including 245 who received radiation to both sides of the neck and putative mucosal sites, limited to the oropharynx and nasopharynx in 167. Excellent rates of disease control were observed, and the 5-year survival rate was 84% for all patients, and 92% for patients with disease known to be HPV-associated.

Statement:

Utilization of comprehensive IMRT in the treatment of carcinoma metastatic to the neck from an unknown primary (CUP), result in excellent rates of disease control and favorable treatment-related toxicity profiles. HPV/P16 status could be incorporated into the clinical decisions for better treatment selection and personalized cancer care for patients with CUP.

Grant or financial support:

Drs. Hutcheson, Mohamed and Fuller received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248-01). Dr. Hutcheson and Fuller are supported via the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Small Grants Program for Cancer Research (R03 CA188162). Dr. Fuller is an MD Anderson Cancer Center Andrew Sabin Family Fellow, and received project support in this role from the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation. Dr. Fuller and Mohamed receive funding and/or salary support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including: a Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825-01); NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148-01); an NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program (P30CA016672) and an NIH/NCI Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50 CA097007-10). Dr. Fuller has received direct industry grant funding and speaker travel from Elekta AB for unrelated technical projects. Family of Paul W. Beach is providing direct salary support for Dr. Kamal. Dr. Ng received grant funding from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR) and Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). These entities played no role in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting its data; writing the manuscript; or making the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strojan P, Ferlito A, Langendijk JA, et al. Contemporary management of lymph node metastases from an unknown primary to the neck: II. a review of therapeutic options. Head Neck. 2013;35: 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Network NCC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines)- Head and Neck Cancers. Available from URL: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/head-and-neck.pdf [accessed May 08, 2017.

- 3.Reddy SP, Marks JE. Metastatic carcinoma in the cervical lymph nodes from an unknown primary site: results of bilateral neck plus mucosal irradiation vs. ipsilateral neck irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37: 797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins SM, Spencer CR, Chernock RD, et al. Radiotherapeutic management of cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary site. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138: 656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jesse RH, Perez CA, Fletcher GH. Cervical lymph node metastasis: unknown primary cancer. Cancer. 1973;31: 854–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson LS, Fletcher GH, Oswald MJ. Guidelines for radiotherapeutic techniques for cervical metastases from an unknown primary. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12: 2101–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colletier PJ, Garden AS, Morrison WH, Goepfert H, Geara F, Ang KK. Postoperative radiation for squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown primary site: outcomes and patterns of failure. Head Neck. 1998;20: 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grau C, Johansen LV, Jakobsen J, Geertsen P, Andersen E, Jensen BB. Cervical lymph node metastases from unknown primary tumours: Results from a national survey by the Danish Society for Head and Neck Oncology. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2000;55: 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nieder C, Ang KK. Cervical lymph node metastases from occult squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank SJ, Rosenthal DI, Petsuksiri J, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical node squamous cell carcinoma metastases from unknown head-and-neck primary site: M. D. Anderson Cancer Center outcomes and patterns of failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78: 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raftery AE. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25: 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head MDA, Neck Cancer Symptom Working G. Beyond mean pharyngeal constrictor dose for beam path toxicity in non-target swallowing muscles: dose-volume correlates of chronic radiation-associated dysphagia (RAD) after oropharyngeal intensity modulated radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2016;118: 304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klem ML, Mechalakos JG, Wolden SL, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer of unknown primary: toxicity and preliminary efficacy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70: 1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoushtari A, Saylor D, Kerr KL, et al. Outcomes of patients with head-and-neck cancer of unknown primary origin treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81: e83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards TM, Bhide SA, Miah AB, et al. Total Mucosal Irradiation with Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy in Patients with Head and Neck Carcinoma of Unknown Primary: A Pooled Analysis of Two Prospective Studies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28: e77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen AM, Li BQ, Farwell DG, Marsano J, Vijayakumar S, Purdy JA. Improved dosimetric and clinical outcomes with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer of unknown primary origin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garden AS, Dong L, Morrison WH, et al. Patterns of disease recurrence following treatment of oropharyngeal cancer with intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85: 941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace A, Richards GM, Harari PM, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma from an unknown primary site. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aslani M, Sultanem K, Voung T, Hier M, Niazi T, Shenouda G. Metastatic carcinoma to the cervical nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site: Is there a need for neck dissection? Head Neck. 2007;29: 585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddad R, O’Neill A, Rabinowits G, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (sequential chemoradiotherapy) versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer (PARADIGM): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen EE, Karrison TG, Kocherginsky M, et al. Phase III randomized trial of induction chemotherapy in patients with N2 or N3 locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 2735–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Maillard E, Bourhis J. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92: 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sher DJ, Balboni TA, Haddad RI, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of chemoradiotherapy using intensity-modulated radiotherapy for unknown primary of head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80: 1405–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mourad WF, Hu KS, Shasha D, et al. Initial experience with oropharynx-targeted radiation therapy for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary of the head and neck. Anticancer Res. 2014;34: 243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang W, Chamberlain PD, Garden AS, et al. Prognostic value of p16 expression in Epstein-Barr virus-positive nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1: E1459–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]