Abstract

Although the reactivity of five-coordinate end-on superoxocopper(II) complexes, CuII(η1-O2•–), is dominated by hydrogen atom transfer, the majority of four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes published thus far display nucleophilic reactivity. To investigate the origin of this difference, we have developed a four-coordinate end-on superoxocopper(II) complex supported by a sterically encumbered bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine ligand, dpb2-MeBPA (1), and compared its substrate reactivity with that of a five-coordinate end-on superoxocopper(II) complex ligated by a similarly substituted tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine, dpb3-TMPA (2). Kinetic isotope effect (KIE) measurements and correlation of second-order rate constants (k2’s) versus oxidation potentials (Eox) for a range of phenols indicates that the complex [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ reacts with phenols via a similar hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) mechanism to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+. However, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ performs HAT much more quickly, with its k2 for reaction with 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methoxyphenol (MeO-ArOH) being >100 times greater. Furthermore, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ can oxidize C–H bond substrates possessing stronger bonds than [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ is able to, and it reacts with N-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (MeAcrH2) approximately 200 times faster. The much greater facility for substrate oxidation displayed by [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ is attributed to it possessing higher inherent electrophilicity than [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+, which is a direct consequence of its lower coordination number. These observations are of relevance to enzymes in which four-coordinate end-on superoxocopper(II) intermediates, rather than their five-coordinate congeners, are routinely invoked as the active oxidants responsible for substrate oxidation.

Introduction

Mononuclear end-on superoxocopper(II) species, CuII(η1-O2•–), have been invoked as hydrogen atom abstracting agents in a plethora of O2 activating copper enzymes.1,2 This includes the noncoupled binuclear copper enzymes PHM, DβM, and TβM, which catalyze hydroxylation of activated C–H bonds of their native substrates,3 and formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE), which is responsible for the conversion of cysteine to formylglycine.4 Although the O2 activating sites in these two sets of enzymes are distinct, they are both widely believed to form four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) active oxidants.

In the case of FGE, the supporting ligands are three cysteinate donors, one of which is the substrate and the other two are active site residues.5−8 In contrast, the noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases possess active sites containing two separate Cu binding sites that are separated by about 11 Å.9 Both contain a single Cu ion coordinated by three amino acid residues and, according to the canonical mechanism, one (CuM) is thought to be responsible for O2 activation and substrate oxidation, while the other (CuH) acts solely as an electron transfer site.10,11 More recent studies have suggested that, instead, the CuII(η1-O2•–) intermediate (at CuM) reacts with the cosubstrate ascorbate to yield a hydroperoxocopper(II) species, which converts to a closed conformation containing the true C–H bond hydroxylating oxidant, believed to be a CuII(μ–OH)(μ-O•)CuII species.12−15 Strong support for the intermediacy of a four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) species in this family of enzymes was provided by measurement of an (albeit photoreduced) X-ray crystal structure of an end-on O2 adduct in the CuM site of PHM.16 Incidentally, a recent neutron crystal structure of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase (LPMO), which catalyzes oxidative breakdown of recalcitrant polysaccharides, revealed a five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–).17 However, contemporary studies concluded that LPMOs are, in fact, peroxygenases, rather than oxygenases, and the CuII(η1-O2•–) intermediates observed in these enzymes are most likely formed during off-pathway reduction of O2 to H2O2 (i.e., they do not react directly with substrate).18−24

The vast majority of synthetic CuII(η1-O2•–) model complexes published, thus far, are supported by tetradentate ligands and possess five-coordinate geometries.25−27 This leaves the copper centers coordinatively saturated and restricts the O2-derived ligand to end-on binding. Ligands of lower denticity usually yield μ-η2:η2-peroxodicopper(II), CuII(μ-η2:η2-O22–)CuII (P), and/or bis(μ-oxo)dicopper(III), CuIII(μ-O2–)2CuIII (O), complexes (Chart 1a). These two species are in equilibrium with one another, and small changes in the supporting ligand can lead to a shift in the predominance of one over the other. This is exemplified by the tridentate N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (BPA) ligand framework, where the substitution patterns of the pyridine and/or the central tertiary amine donors (Chart 1b) can shift the equilibrium entirely from one species to the other.28 More specifically, introduction of steric bulk onto the BPA ligand framework can shift the equilibrium from exclusive formation of O (i.e., RBPA, with R′ = H)29−31 to mixtures O and P (BnBQA)32 and, in the bulkiest systems, to formation of only P (RMe2BPA and PheBQA).32,33 These observations have been attributed to steric inhibition of the close approach of the Cu ions, which is required for formation of the O core. Thus far, no mononuclear O2 adducts have been observed in these BPA complexes. However, kinetic data suggests that O and P are formed by preequilibrium binding of O2 to a copper(I) BPA complex, to give either a CuII(η1-O2•–) or CuII(η2-O2•–) complex, followed by rate-determining reaction with a second copper(I) center.29,32,34

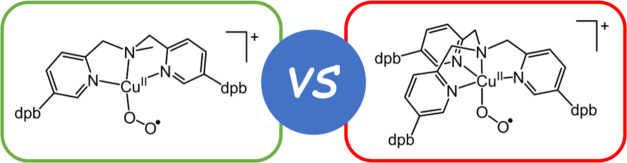

Chart 1. Selected Copper(I) + O2 Reactivity, Ligands, and Cu-O2 Adducts Relevant to this Worka.

a (a) General scheme for reaction of low-coordination number copper(I) complexes with O2 and (b) published BPA-derived ligands that support this chemistry. Previously reported examples of low-coordinate (c) side-on (η2) and (d) end-on (η1) 1:1 adducts of copper complex and O2. (e) The CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes studied in this work.

Inclusion of bulky substituents onto bidentate and tridentate ligands can be used to inhibit the formation of dicopper-O2 adducts.35−40 However, in this scenario, side-on coordination to yield either η2-superoxocopper(II) or, in the case of more strongly reducing ligands, η2-peroxocopper(III) complexes is commonly observed (Chart 1c).41 This binding mode retards reactivity, which has allowed several of these complexes to be crystallographically characterized.35,38−40,42 All exceptions to this side-on O2 binding preference reported, thus far, were obtained using linear tridentate ligands (Chart 1d).43−47 Interestingly, the majority of these four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes display nucleophilic reactivity. This is personified by Tolman’s complex [CuII(η1-O2•–)(iPr2PCA)]−, which reacts with phenols primarily via proton transfer and subsequent electron transfer (i.e., PT/ET),48 and performs deformylation of a selection of electron-rich aldehydes.49,50 In contrast, Itoh’s and Anderson’s respective four-coordinate complexes [CuII(η1-O2•–)(XPPEDC)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(tBu,TolDHP–)] display predominant electrophilic character.51 Whereas [CuII(η1-O2•–)(tBu,TolDHP–)] is a weak oxidant that shows no reactivity with C–H bonds,47 [CuII(η1-O2•–)(XPPEDC)]+ can directly oxidize ferrocenes and intramolecularly hydroxylate an N-ethylphenyl substituent of the ligand.44,52,53 The latter is the only published example of C–H bond oxidation by a four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complex and remains the only example of C–H bond hydroxylation by any synthetic CuII(η1-O2•–) species.

The predominance of nucleophilic substrate reactivity in four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes is in stark contrast to five-coordinate and enzymatic CuII(η1-O2•–) species, whose substrate reactivity is characterized by electrophilic hydrogen atom abstractions.25,54,55 The origin of this difference has not been investigated but likely derives, in part, from the divergence in the nature/basicity of the donors in the supporting ligands. In the hope of gaining insight into the aforementioned disparity in reactivity, we sought a pair of four- and five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes supported by tridentate and tetradentate ligands, respectively, that differ only in the presence/absence of a single donor. Given our success in stabilizing five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes of tetradentate tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (TMPA) ligands by incorporating large aryl substituents onto the 5-position of their pyridine donors,56 we developed a similarly substituted tridentate bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (BPA). The resulting ligand dpb2-MeBPA (1) was found to support a CuII(η1-O2•–) complex, and its reactivity was compared to that of dpb3-TMPA (2), which deviates from the former by replacement of one 2-pyridylmethyl arm by a methyl substituent (Chart 1e).

Results and Discussion

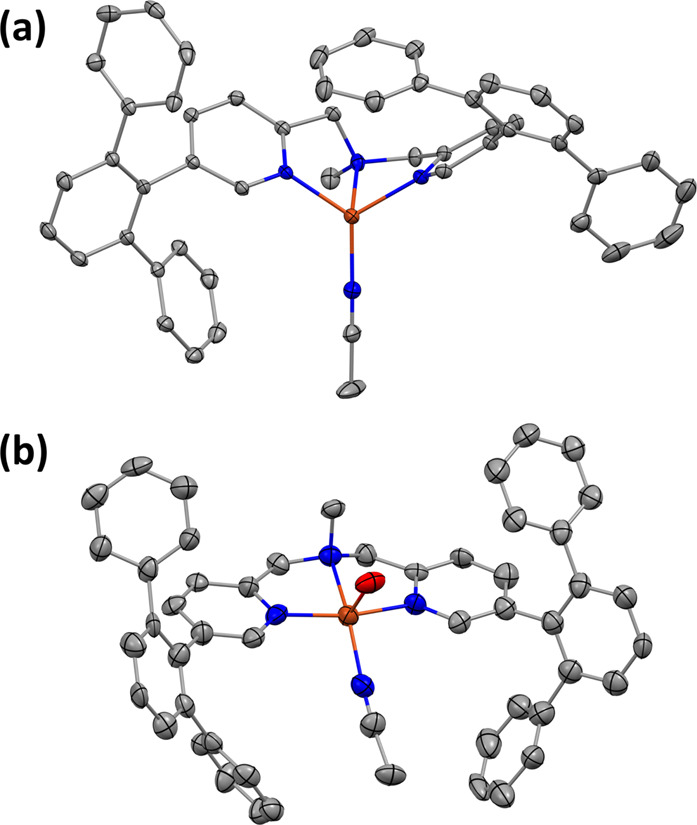

Copper(I) complexes of formulation [CuI(1)(NCMe)](X), where X = B(C6F5)4– and SbF6–, were prepared by a combination of 1 with the corresponding [CuI(NCMe)4](X) salts. Oxygenation studies were performed exclusively using [CuI(1)(NCMe)][B(C6F5)4], but crystals suitable for X-ray crystallographic characterization could only be grown for [CuI(1)(NCMe)](SbF6) (Figures 1a and S10, Table S2). The latter possesses a distorted trigonal pyramidal geometry (as indicated by the geometry index τ4 = 0.81),57 with the tertiary amine donor in a pseudoaxial position and Cu–Namine, average Cu–Npyridine, and Cu–NMeCN bond distances of 2.206(2), 2.035(2), and 1.891(2) Å, respectively. This is typical for four-coordinate copper(I) complexes of BPA-type ligands that include acetonitrile (MeCN) coligands.30,32,33,58−60

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structures of (a) [CuI(1)(NCMe)](SbF6) and (b) [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)](ClO4)2, depicted using 50% thermal ellipsoids. For clarity, hydrogen atoms, counterions, and solvent molecules have been omitted. Gray, orange, blue, and red spheroids correspond to carbon, copper, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms, respectively.

In contrast, recrystallization of the product obtained from reaction of 1 with the copper(II) salt CuII(ClO4)2·6H2O afforded the square-based pyramidal complex (τ5 = 0.05)61 [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)](ClO4)2 (Figures 1b and S11, Table S3). Therein, N-donors occupy the equatorial positions, and a H2O ligand coordinates in the axial site. As expected for a Jahn–Teller distorted copper(II) complex, the Cu–O distance is comparatively long, at 2.273(13) Å. Consistent with its higher oxidation state, the Cu–Namine and average Cu–Npyridine bond lengths in this complex, 2.016(13) and 1.958(6) Å, respectively, are significantly contracted relative to those of [CuI(1)(NCMe)](SbF6). The shortening of the former distance (by approximately 0.19 Å) is particularly large and is likely, partly, due to the accompanying elongation of the Cu–NMeCN distance (by approximately 0.12 Å) to 2.015(13) Å. This increase in Cu–NMeCN bond length can be attributed to reduced π back-bonding in copper(II), relative to copper(I).

Cyclic voltammetry measurements for copper(II) complex [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)](ClO4)2 yielded a quasi-reversible CuII/CuI redox couple in acetonitrile solution (Figure S12), with an E1/2 value of −0.30 V (vs Fc+/Fc0). This is more than 100 mV positive of the E1/2 recorded for [CuII(2)(NCMe)]2+ (−0.41 V), but it is similar to values reported for [CuII(dtbpb3-TMPA)(NCMe)]2+ and [CuII(MeBPA)(NCMe)(OTf)]+ (−0.32 and −0.29 V, respectively).56,62 From this, we can expect [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ to have a similar affinity for O2 binding as [CuI(dtbpb3-TMPA)]+, which displays saturation of O2 binding in THF solution at ≤−70 °C.

Superoxocopper(II) Complex Formation and Characterization

Bubbling O2 through pale yellow tetrahydrofuran solutions of [CuI(1)(NCMe)][B(C6F5)4], at −90 °C (Figure 2a), led to formation of a green species displaying ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectral features (λmax = 404 and 722 nm; εmax = 2680 and 1060 M–1 cm–1, respectively) characteristic of a CuII(η1-O2•–) complex.26,27 For comparison, some published examples are listed in Table 1. In contrast to the time frame of <10 s (s) required for generation of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+, maximum formation of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ took >180 s (Figure S14). This difference can be attributed to a divergence in mechanism, with the former involving oxygenation of a copper(I) complex possessing a vacant coordination site (i.e., [CuI(2)]+, eq 2) and the latter requiring dissociation of a solvent ligand prior to reaction with O2 (eqs 1 and 2). Consistent with the need for dissociation of acetonitrile from [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ prior to oxygenation, the addition of small amounts of acetonitrile (1–5 equiv) results in significantly decreased yields of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ (Figure S15). Crucially, the observed CuII(η1-O2•–) complex, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+, is stable under the conditions of the experiment, with no evidence for conversion to higher nuclearity P or O species. Furthermore, warming solutions of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ led to self-decay, but without formation of chromophores characteristic of P or O.

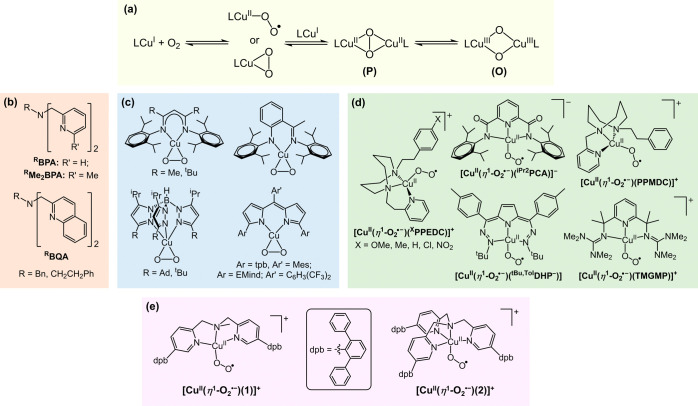

Figure 2.

(a) UV–vis spectra of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ (black and green lines, respectively), recorded in THF solution at −90 °C. (b) Resonance Raman spectra of [CuII(η1-16O2•–)(1)]+, prepared using natural abundance O2, and [CuII(η1-18O2•–)(1)]+ (black and red lines, respectively), recorded in frozen d8-THF solution using λex = 407 nm. K-edge HERFD XAS data recorded for (c) [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+, [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+, and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ (black, red, and green lines, respectively) and (d) [CuI(2)]+, [CuII(2)(NCMe)]2+, and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ (black, red, and green lines, respectively). DFT (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP) geometry-optimized structures of (e) [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and (f) [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Table 1. Summary of Spectroscopic Parameters for the End-On Superoxocopper(II) Complexes, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(L)]n, Described Herein and Selected Published Examples.

| L | λmax, nm (εmax, M–1 cm–1) | ν(O–O) (cm–1) | ν(Cu–O) (cm–1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-coordinate | 1 | 404 (2680), 722 (1060) | 1137 | 464 |

| HPPEDC44 | 397 (4200), 570 (850), 705 (1150) | 1033 | 457 | |

| PPMDC45 | 386 (4430), 558 (820), 725 (1160) | 1064 | 464 | |

| TMGMP46 | 359 (1800), 595 (970) | 1136 | ||

| tBu,TolDHP–47 | 420 (13,600), 670 | 1067 | ||

| iPr2PCA2–49 | 628 (1400) | 1102 | ||

| 5-coordinate | 2(56) | 430 (3950), 584 (1150), 760 (1690) | 1126 | 467 |

| 1PVTMPA63 | 410 (3700), 585 (900), 741 (1150) | 1130 | 482 | |

| TMG3tren64−66 | 448 (3400), 676, 795 | 1120 | 435 | |

| TMGN3S67 | 442 (3700), 642 (1525), 742 (1675) | 1105 | 446 |

| 1 |

| 2 |

Confirmation of the formation of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ was obtained via resonance Raman spectroscopy (Figures 2b and S13). Using natural abundance O2 and an excitation wavelength (λex) of 407 nm, peaks at 1137 and 464 cm–1 were observed. Production of samples using 18O2 gas caused these peaks to shift by 63 and 17 cm–1, respectively, to 1074 and 447 cm–1. Based upon the energies of these peaks and the magnitudes of their isotope shifts, which are very similar to those of previously reported CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes (see Table 1 for examples),26,27 they can be assigned as O–O and Cu–O stretches, respectively. These ν(O–O) and ν(Cu–O) values are distinct from those of their side-on bound congeners (i.e., Cu(η2-O2) complexes), which tend to be in the regions of ∼1000 cm–1 and 490–560 cm–1, respectively.26

The electronic structure of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ was probed by Cu K-edge high energy resolution fluorescence detection X-ray absorption spectroscopy (HERFD XAS) measurements. To provide a frame of reference, data were also collected for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+, the copper(I) starting complexes [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ and [CuI(2)]+, and the copper(II) salts [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+ and [CuII(2)(NCMe)]2+. The spectral features of the series of compounds supported by compounds 1 and 2, respectively, are broadly similar (Figure 2c,d). Both CuI complexes display an intense feature in the rising edge at ∼8981 eV, which is characteristic of CuI and arises from 1s → 4p transitions. Although this appears to be a single and higher intensity feature in [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+, which indicates that all 1s → 4p transitions in this complex occur at similar energies, the corresponding feature in [CuI(2)]+ possesses a shoulder at ∼8979 eV. This difference can be attributed to the geometry of [CuI(2)]+ being closer to a true trigonal pyramid than that of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+. The geometry of the latter is significantly distorted toward tetrahedral, which will manifest as a reduced energetic separation of the 4p orbitals. Additionally, a trend in the energy of the rising edge can be seen within both the 1 and 2 ligated series of complexes, with CuII salts > CuII(η1-O2•–) > CuI complexes. This is concordant with expectations, as increasing the oxidation state leads to a contraction of core orbitals, thereby increasing the energy of the rising edge. The high metal–ligand covalency of the CuII(η1-O2•–) moiety ameliorates this effect, leading to an intermediate rising edge energy.

Pre-edge and rising edge features attributable to ligand-to-metal charge transfers (LMCTs) are seen in the XAS spectra of the CuII salts, [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+ and [CuII(2)(NCMe)]2+. Although similar, albeit weaker, features are seen for the CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes, they likely arise from residual CuI starting materials. More specifically, the XAS spectra of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+, depicted in Figure 2, are estimated to contain contributions from approximately 20% [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ and 5% [CuI(2)]+, respectively. These impurities prevent any definitive statements regarding the greater intensity observed for the pre-edge of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ relative to that of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+. However, we can confidently conclude that the pre-edge intensities and energies of the CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes and CuII salts are markedly similar to one another. Additionally, the positions of the pre-edges of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ are both shifted by +0.4 eV relative to those of the corresponding CuII salts.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations support the formulation of the title Cu–O2 adduct as [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+. Consistent with previous reports,43,52,63,64,67,68 geometry optimizations revealed that the triplet (S = 1) state was most stable for end-on binding of the superoxo moiety (Figure S33 and Table S13). The geometry-optimized structure of the lowest energy triplet state calculated for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ (Figure 2e) displays a seesaw geometry (τ4 = 0.42). This contrasts with the distorted trigonal pyramidal geometries of the experimentally observed and calculated structures (both τ4 = 0.81) of starting complex [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ (Figures 1a and S32), but is similar to the DFT geometry-optimized structures of other four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes (Table 2). The lowest energy triplet state of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ displays a Cu–O–O bond angle and an O–O bond length of 118.8° and 1.253 Å, respectively (Table S13). The latter is short for a superoxo anion. However, the functional B3LYP has a well-documented tendency to overestimate metal–ligand bond lengths, which will reduce the extent of charge transfer into π-acceptor ligands (e.g., O2). Thus, an underestimation of the O–O bond length is within expectations.

Table 2. Summary of Key Bond Metric Data for DFT Geometry-Optimized Structures of the [CuII(η1-O2•–)(L)]n Complexes Described Herein and Selected Published Examples.

| L | Cu–O1 (Å) | O1–O2 (Å) | Cu–O1–O2 (deg) | τ457 | τ561 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-coordinate | 1a | 1.984 | 1.253 | 118.8 | 0.42 | |

| HPPEDCb | 1.907 | 1.259 | 121.0 | 0.37 | ||

| PPMDCc | 1.937 | 1.297 | 91.2 | 0.36 | ||

| TMGMPd | 1.936 | 1.300 | 113.8 | 0.16 | ||

| tBu,TolDHP–e | 2.097 | 1.272 | 112.5 | 0.56 | ||

| iPr2PCA2–f | 1.966 | 1.292 | 115.1 | 0.16 | ||

| 5-coordinate | 2a | 1.968 | 1.264 | 113.8 | 0.96 | |

| TMPAg | 1.976 | 1.285 | 116.5 | 0.92 | ||

| TMG3trenh | 1.988 | 1.292 | 120.1 | 0.92 | ||

| TMGN3Sh | 1.994 | 1.286 | 113.0 | 0.89 |

As might be expected, time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) calculated UV–vis spectra for the triplet and open-shell singlet states are, in terms of general appearance, very similar to one another (Figures S42–S44). Although the experimental spectral features are reasonably well reproduced for both spin states, the relative band intensities in the triplet state better fit experiment. Similarly, due to deviation from the experimental spectrum, a five-coordinate acetonitrile-coordinated formulation [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)(NCMe)]+ can also be safely discarded (see the Supporting Information). TDDFT calculated XAS spectra yield similar conclusions (Figure S49 and the accompanying discussion). Those of the triplet and singlet states of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ have rising edges that closely resemble one another. However, the calculated XAS spectrum of the triplet state more accurately reproduces the experimentally observed shift in pre-edge energy relative to [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+ (0.4 eV in both experiment and calculation) and the relative differences with respect to the rising edge energies of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ and [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+. The reliability of our computational models is validated by the TDDFT calculated XAS spectra of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ and [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+, which closely reproduce their experimentally observed features. See the Supporting Information for a discussion of these results.

To better describe the electronic structure of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and more accurately estimate its singlet–triplet energy splitting, multiconfigurational N-electron valence state perturbation theory calculations, based on a (12,12) complete active space reference wave function (CASSCF/NEVPT2), were performed. Active space natural orbitals and their occupation numbers are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S40 and S41). As expected, the CASSCF/NEVPT2 calculated triplet state is characterized by a single determinant, with singly occupied 3dz2 and π*v orbitals and full occupation of the remaining four Cu 3d orbitals (Table S16). In contrast, the singlet wave function is composed of two configurations with weights of 0.63 and 0.34 (Table S17), which indicates that this state possesses high biradical character. These singly occupied orbitals have occupation numbers of 1.294 and 0.704 (Figure S41), respectively, and show more mixing between the Cu 3dz2 and the O 2p orbitals than the triplet state. The other Cu 3d orbitals are doubly occupied. In essence, the CASSCF calculations yield a CuII(η1-O2•–) description displaying either a triplet or singlet diradical state. While DFT predicts that the triplet state is significantly more stable than the open-shell singlet state, CASSCF/NEVPT2 places the former 1.2 kcal mol–1 higher in energy than the latter (Tables S18 and S19). Thus, it can be concluded that the two spin states are nearly degenerate. This outcome is consistent with reports made for related systems.69,70

Reaction with O–H Bond Substrates

To allow comparison with [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+, reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with a series of 4-substituted (X) 2,6-di-tert-butylphenols (X-ArOH) was studied at −90 °C. In all cases, this proceeded with first-order decay of the UV–vis features associated with the CuII(η1-O2•–) unit and growth of two bands centered at around 530–590 and 730–790 nm (Figures 3a and S16), respectively. The precise spectral features (λmax and εmax values) of the products were found to depend upon the identity of substituent X. However, the intensities of the two bands suggest that they possess some ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) character. Additionally, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of the products of the reaction with X-ArOH (Figure S27) all display signals indicative of a copper(II) complex possessing a dx2–y2 ground state (i.e., gz > gx = gy). The para substituents (X) of the various X-ArOH substrates did not significantly impact the EPR spectral parameters (Table S5). This contrasts with observations made for the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with TEMPO-H, which is complete within a few seconds and yields a product with UV–vis features typical of a hydroperoxocopper(II) complex (Figure S18; λmax = 384 nm).67,71−76 Interestingly, this putative hydroperoxocopper(II) undergoes slow decay even at −90 °C, and efforts to generate it by treatment of copper(II) complex [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)](ClO4)2 with H2O2/triethylamine were not successful (i.e., it formed as a very short-lived species).

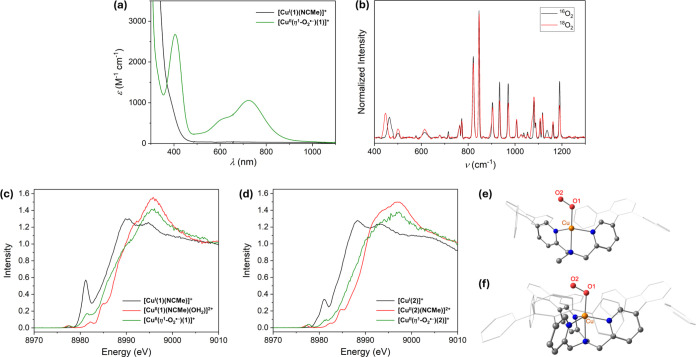

Figure 3.

(a) Main: The UV–vis spectral changes observed upon reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•−)(1)]+ with 2,6,-di-tert-butyl-4-methoxyphenol (MeO-ArOH). Green, black, and gray lines correspond to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+, the product of reaction, and the spectra recorded in between, respectively. Inset: absorbance at 404 nm as a function of time and best-fit line (black dots and red line, respectively). (b) Plot of the observed rate constants (kobs, s–1) versus substrate concentration (M), including best-fit lines, recorded for reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeO-ArOH and MeO-ArOD (black and red circles/lines, respectively). (c) Marcus plot of (kBT/e) ln(k2) values obtained from reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with 4-substituted 2,6,-di-tert-butylphenols (X-ArOH) versus the oxidation potentials (Eox, V vs Fc+/Fc0) of the X-ArOH substrates. (d) Plot of the observed rate constants (kobs, s–1) versus substrate concentration (M) recorded for reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with N-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (MeAcrH2) and xanthene (black and red circles/lines, respectively). All reactions depicted were performed in THF solution at −90 °C.

Taken together, the aforementioned findings are consistent with the formulation of the products of the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with X-ArOH as [CuII(OAr-X)(1)]+. This notion is supported by the striking similarity of their UV–vis spectra to those reported for the phenoxocopper(II) complexes [CuII(OAr)(iPr2PCA)]− and [CuII(OAr)(XPPEDC)]+, which were obtained from reaction of the corresponding four-coordinate superoxocopper(II) complexes, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(iPr2PCA)]− and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(XPPEDC)]+, with 4-substituted phenols.48,53 In particular, [CuII(OAr)(iPr2PCA)]− and [CuII(OAr)(XPPEDC)]+ both display chromophores composed of the two moderately intense features at around 490–540 and 700–740 nm, respectively.

Unfortunately, the [CuII(OAr-X)(1)]+ complexes are not thermally stable, which prevented their characterization by X-ray crystallography and collection of informative electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) data. However, independent preparation, by the combination of [CuII(1)(NCMe)(OH2)]2+ with X-ArOK (at −90 °C), afforded complexes possessing very similar UV–vis and EPR spectra (Figures S26 and S28, respectively). Additionally, a DFT exploration of the potential energy surface of four-coordinate [CuII(OAr-Me)(1)]+ revealed three energetically close minima corresponding to different phenoxocopper(II) conformers (Figure S37). All three minima display distorted square planar or seesaw geometries (τ4 = 0.23–0.48; Table S15), near-axial EPR parameters (Table S21), and TDDFT calculated UV–vis spectra that bear a close resemblance to experiment (Figures S46–S48), wherein the transitions possess significant LMCT character. These results reaffirm our assignment.

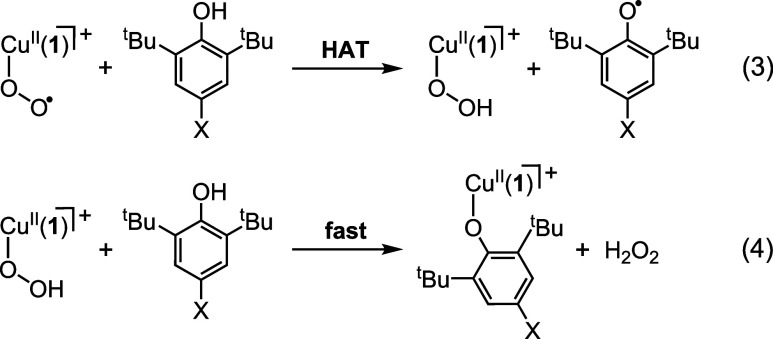

Reaction between [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and X-ArOH is expected to proceed either via protonation of the superoxo moiety or by a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reaction. Protonation would yield [CuII(OAr-X)(1)]+ and HO2•. The latter would likely either disproportionate to 1/2 equiv each of O2 and H2O2, as suggested by Itoh and co-workers,53 or react with phenol to yield 1 equiv each of phenoxyl radical, X-ArO•, and H2O2. In contrast, HAT would initially yield a hydroperoxocopper(II) complex, [CuII(OOH)(1)]+, and X-ArO• (eq 3). Subsequent, rapid protonolysis of [CuII(OOH)(1)]+ by comparatively acidic X-ArOH would provide free H2O2 and experimentally observed [CuII(OAr-X)(1)]+ (eq 4). In essence, protonolysis and reaction via HAT might yield 1 equiv of both X-ArO• and H2O2, which would make them indistinguishable on the basis of product stoichiometry.

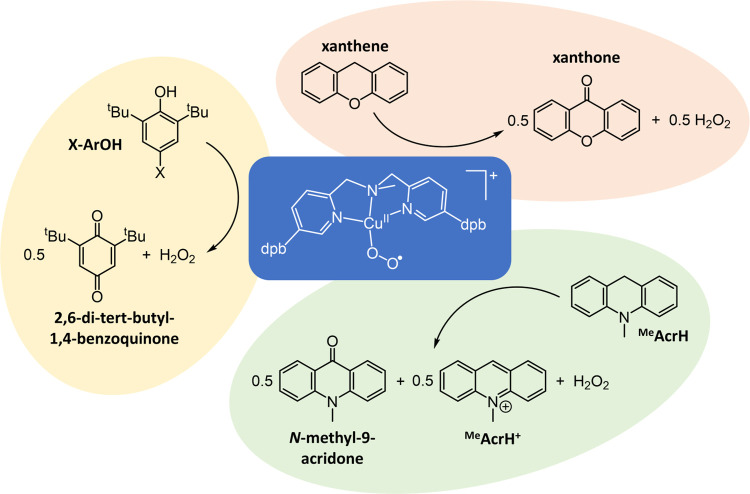

To confirm the feasibility of the aforementioned HAT and protonolysis mechanistic pathways, the other products of reactions of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and X-ArOH were identified and quantified. Consistent with expectations and previous studies of reaction of CuII(η1-O2•–) with phenols,72,73 iodometric titration confirmed the presence of 1 equiv of H2O2 for all X-ArOH substrates (Table S12). In contrast, the formation of X-ArO• was not observed by UV–vis spectroscopy, and it was detected by EPR spectroscopy in only one case (i.e., MeO-ArO•), in minor quantities (Figure S27a). Although this would seem to preclude the aforementioned mechanisms, the absence of X-ArO• can result from the rapid conversion to other products. Similar observations were made by Karlin and co-workers for the complex [CuII(η1-O2•–)(DMM-TMPA)]+, and were rationalized by invocation of a mechanism revolving around reaction of X-ArO• with a second molecule of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(DMM-TMPA)]+.77 Instead, 1/2 equiv 2,6-di-tert-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone was reportedly formed as the product of reaction. GC-MS analysis of the product mixtures from reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and X-ArOH yielded a similar outcome, with 1/2 equiv 2,6-di-tert-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone (i.e., approximately 50% yield; Scheme 1 and Table S8) being obtained for all X-ArOH substrates.

|

3 |

Scheme 1. Summary of the Substrates Used in the Reaction Kinetic Studies with [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and the Products Obtained.

In X-ArOH, X = OMe, MPPO, Me, Et, and tBu. MPPO = 2-methyl-1-phenylpropan-2-yloxy.

The observed pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) derived from the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with the various X-ArOH were found to be linearly dependent upon substrate concentration (Figures 3b and S17), thereby yielding second-order rate constants (k2). These values were found to be significantly larger than those measured for the tetradentate ligand coordinated analogues [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(tpb3-TMPA)]+ (Table S4 and Figure S22), which were previously confirmed to react with X-ArOH via HAT.56 For instance, the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ with MeO-ArOH (at −90 °C) proceeds with k2 values of 15 and 0.13 M–1 s–1, respectively. This corresponds to >100-fold faster reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ relative to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+.

To determine whether the difference in the oxidative facility of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ originates from a change in mechanism, k2 values for reaction with the deuterated substrate MeO-ArOD were measured (Figures 3b and S24a) and their primary kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) were calculated. The KIE of 5.9 obtained for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ at −90 °C is very similar to the value of 5.2 measured for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ at −40 °C and is suggestive of rate-determining hydrogen atom abstraction from the phenolic substrate. To verify this conclusion, a Marcus-type plot of log(k2) values obtained from the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with a series of X-ArOH substrates versus the oxidation potential (Eox) of the substrates was constructed (Figure 3c). For such a plot, a slope with a gradient of 0 would be expected for a pure HAT reaction, whereas an initial discrete e– transfer would yield a value between −0.5 and −1.0.78−80 Conversely, given that the acidity of phenols increases in parallel with their Eox values, a positive slope would be obtained for a reaction involving an initial discrete proton transfer step (i.e., protonolysis of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+). The Marcus-type plot for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ displays a linear correlation possessing a slope of −0.26, which is indicative of a HAT reaction that proceeds via a transition state involving significant charge transfer.77,81,82 This is very similar to the value of −0.24 obtained from an analogous plot for the complex [CuII(η1-O2•–)(tpb3-TMPA)]+, whose reactivity is essentially identical to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+.56

In essence, the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ with X-ArOH substrates shares the same general mechanistic properties, with it proceeding via an initial HAT (eq 3). The resulting hydroperoxocopper(II) complex, [CuII(OOH)(1)]+, then reacts with an additional molecule of X-ArOH (via protonolysis) to give [CuII(OAr-X)(1)]+ and 1 equiv of H2O2 as products (eq 4). This differentiates [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ from the four-coordinate complexes [CuII(η1-O2•–)(iPr2PCA)]− and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(XPPEDC)]+, which both react with phenols (primarily) via protonolysis of the superoxo ligand.48,53

As a means of examining the impact of steric bulk upon the rate of reaction with [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+, the substrate 4-methoxyphenol was employed. Although this substrate has a much smaller steric profile than the X-ArOH substrates, which might be expected to result in faster reaction, it has a significantly higher bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE) of 87.6 kcal mol–1,83 which would be expected to retard reaction. For comparison, MeO-ArOH and tBu-ArOH have BDEs of 82.0 and 85.2 kcal mol–1, respectively.83 As with the X-ArOH substrates, the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with 4-methoxyphenol was found to be first order in both the complex and substrate (Figure S19). Fitting of the data yielded a k2 of 0.0035 M–1 s–1 that is ∼10 times lower than the value measured for reaction with tBu-ArOH. This suggests that the rate of reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with phenolic substrates is largely controlled by thermodynamic factors, with sterics having little impact. It should be noted that under the same reaction conditions, at −90 °C, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ shows little or no reaction with tBu-ArOH and more oxidatively resistant phenols. From this, it can be inferred that the thermodynamic driving force for the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ is greater than [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+.

Reaction with C–H Bond Substrates

Reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with substrates containing weak C–H bonds was also examined, but it presented a more complicated picture. This is because these substrates often possess olefinic functionality that are able to bind to copper(I). Given that O2 binding is an equilibrium process, such substrates can cause deoxygenation of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and formation of a copper(I) olefin complex, [CuI(1)(olefin)]+. Behavior of this type was observed for the [CuII(η1-O2•–)(Ar3-TMPA)]+ complexes,56 but it is more pronounced in [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+. For instance, the addition of 10 equiv of 1,4-cyclohexadiene (1,4-CHD) to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ caused near-instantaneous loss of its chromophore and formation of a copper(I) complex (Figure S20b), which is presumed to be [CuI(1)(1,4-CHD)]+. This complex can be made independently by the addition of 1,4-CHD to a THF solution of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+, which caused a change in color from pale yellow to colorless. The UV–vis spectral change associated with this reaction and the 1H NMR spectrum of the product are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S5 and S20c).

A similarly fast reaction was observed (Figure S20a) upon the addition of 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide (BNAH), in place of 1,4-CHD, to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+. It was initially assumed that this solely reflected the dissociation of O2 and the binding of BNAH in its place. However, reaction workup provided a 41(5) % yield of 1-benzylnicotinamidium (BNA+; eq S3 and Table S9). This suggests that binding of O2 and BNAH to the copper(I) center are both in equilibrium and small concentrations of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ are present, which rapidly oxidizes BNAH. Given the resulting mechanistic complexity, no efforts were made to deconvolute the kinetic data and, instead, we sought substrates with lower tendencies to bind to copper(I).

A survey of potential substrates containing weak C–H bonds was performed, and N-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (MeAcrH2) and xanthene were observed to have a minimal instantaneous impact upon the chromophore of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ (Figure S21), which implies comparatively weak coordination to copper(I). This renders them suitable for the measurement of nonambiguous reaction kinetics. The subsequent slow changes in UV–vis spectroscopic features (that accompany reaction with MeAcrH2 and xanthene) display commonalities: the loss of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ and formation of a product containing ligand field transitions typical of copper(II) complexes. EPR spectra of the products obtained from reaction with MeAcrH2 and xanthene (Figure S29 and Table S7) both contain near-identical axial signals corresponding to a single copper(II) complex possessing a dx2–y2 ground state (i.e., gz > gx = gy). Given the absence of evidence for the formation of [CuII(OOH)(1)]+, this is suggested to be a hydroxocopper(II) complex, [CuII(OH)(1)]+, formed by hydrolysis with adventitious water.

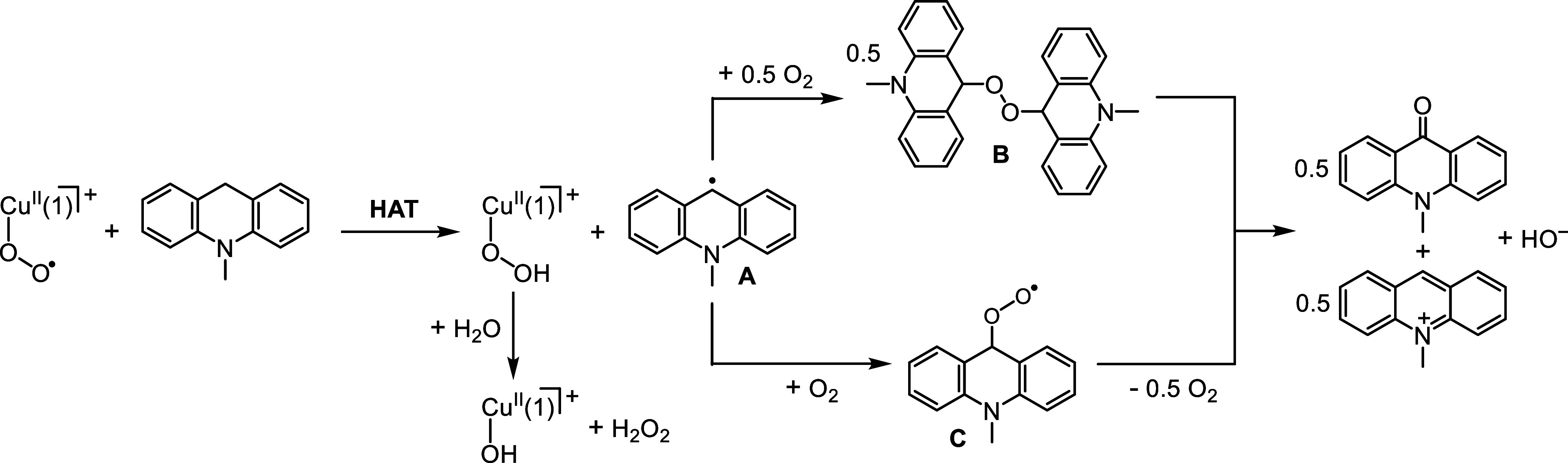

However, there are also readily discernible differences between reactions of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeAcrH2 and xanthene. The most obvious is the growth of sharp UV–vis features during reaction with MeAcrH2, between 350 and 420 nm, that are indicative of contemporaneous formation of MeAcrH+ and N-methyl-9-acridone (Figures S21a and S25). Consistent with this, analysis of the corresponding product mixtures confirmed the presence of 1 equiv of H2O2, 1/2 equiv of N-methyl-9-acridone (respective yields of 90(5) and 49(4) %), and, at least, 1/2 equiv of MeAcrH+. In contrast, reaction with xanthene produces 1/2 equiv of both xanthone and H2O2 (yields of 48(4) and 59(5) %, respectively).

Although HAT is almost certainly the rate-determining step in the oxidation of xanthene, the substrate MeAcrH2 can function as both a hydrogen atom donor and a hydride donor, with the observed behavior depending on the properties of the acceptor. Hydride donation by MeAcrH2 should initially yield only N-methyl-acridinium (MeAcrH+) and, conversely, HAT would be expected to form oxygenated products, including acridone. On this basis alone, we can conclude that the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeAcrH2 also proceeds via HAT. Reaction of CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes with more potent hydride donors than MeAcrH2 (i.e., BNAH and BzImH) has also been reported to proceed via HAT.56,63 Consistent with expectations for HAT, the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeAcrH2 and xanthene was found to be first-order in both complex and substrates (Figure 3d), and the resulting k2 values (0.0059 and 0.00065 M–1 s–1, respectively) are dependent upon the relative C–H bond dissociation enthalpies, BDEs, of the substrates. More specifically, the ∼1 order of magnitude faster reaction with MeAcrH2 reflects the smaller BDE of its reactive C–H bond compared to that of xanthene (73.0 and 77.9 kcal mol–1, respectively).83,84

Stoichiometric formation of H2O2 from the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeAcrH2 implies that [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ is converted solely to [CuII(OOH)(1)]+ (Scheme 2), which is probably either hydrolyzed during reaction or upon workup. The associated HAT reaction would generate 1 equiv of the N-methyl-9-acridinyl radical (A), which would then, presumably, react with O2 to give either 1 equiv of the N-methyl-9-acridinylperoxy radical (C) or 1/2 equiv of di(N-methyl-9-acridinyl) peroxide (B). Disproportionation of the former and heterolytic cleavage of the latter would afford 1/2 equiv each of the N-methyl-9-acridone and 9,10-dihydro-10-methyl-9-acridinol. Instantaneous extrusion of the hydroxide anion from 9,10-dihydro-10-methyl-9-acridinol, driven by aromatization, would yield the observed 1/2 equiv MeAcrH+.

Scheme 2. Possible Mechanisms for Equimolar Formation of N-Methylacridone and N-Methylacridinium from the Reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ with MeAcrH2.

Lastly, the reaction of [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ with substrates containing weak C–H bonds is difficult to study at −90 °C because it is tremendously slow. Consequently, we have measured kinetics for these reactions only at −40 °C (Figures S23 and S24b). Even at this temperature, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ displayed no observable reaction with xanthene, and the reaction with BNAH and MeAcrH2 proceeded slowly, affording respective k2 values of 0.14 and 0.00094 M–1 s–1. The latter k2 value is approximately 6 times smaller than that measured for [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ at −90 °C. Taking the temperature difference into account, it is estimated that [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ reacts with MeAcrH2 ∼ 200 times faster than [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+.

Conclusions

In previously published BPA-supported systems, mononuclear Cu–O2 adducts have been invoked as intermediates in the formation of dicopper-O2 adducts, P and O. However, they had never been directly observed, which left questions regarding their binding mode, electronic structure, and reactivity properties. Herein, by judicious incorporation of large aryl substituents onto the BPA ligand framework, we have developed a four-coordinate copper(I) complex, [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+, that binds O2 to give a superoxocopper(II) complex that is stable against collapse to higher nuclearity P or O species. This superoxocopper(II) complex was spectroscopically and computationally characterized, and it is concluded that it is end-on bound and is thusly formulated as [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+. There are only a handful of four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) model complexes, with the vast majority reported over the past 30+ years being five-coordinate species. Interestingly, all of these four-coordinate complexes have geometries that are best described as seesaw, with all but one being closer to square planar than tetrahedral.

The ligand design strategy employed in this study was previously used in a series of tetradentate TMPA ligands and allowed us to synthesize a series of highly stable five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes. This included 2, which bears the same aryl substituents as 1. The similarity of these two ligands, which differ by a single pyridine donor, provides a hitherto unavailable opportunity to directly compare the inherent reactivity of four- and five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) species. It was discovered that [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ reacts with hydrogen atom donor substrates 2 orders of magnitude faster than [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+. More specifically, the former reacts with MeO-ArOH and MeAcrH2 approximately 100 and 200 times faster, respectively, than the latter. Furthermore, [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ is observed to react with the substrates 4-methoxyphenol and xanthene, which possess stronger O–H and C–H bonds, whereas [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+ cannot. From these observations, it can be inferred that the thermodynamic driving force for HAT to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(1)]+ is greater than that to [CuII(η1-O2•–)(2)]+. This is presumably due to the greater inherent electrophilicity of the four-coordinate center, which is a natural result of having a reduced number of ligand donors, and is evident in a 110 mV more positive CuII/CuI redox potential of [CuI(1)(NCMe)]+ compared with [CuI(2)(NCMe)]+. Similar parallels can be (or have been) drawn between CuII/I reduction potentials and the reactivity of five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes. For instance, Karlin and co-workers have shown, in two separate cases, that replacement of a nitrogen donor in a tripodal tetradentate N4 ligands by a thioether not only causes a significant increase in CuII/CuI redox potential but also leads to enhanced substrate reactivity.67,85 Similarly, the precursors to the four-coordinate complexes [CuII(η1-O2•–)(XPPEDC)]+ and [CuII(η1-O2•–)(PPMDC)]+ have CuII/CuI redox potentials of 0.4 and 0.17 V (vs SCE), respectively, and whereas the former is able to oxidize ferrocenes and intramolecularly hydroxylate the ligand’s phenylethyl substituent, the latter displays only nucleophilic reactivity.45,51

Nevertheless, there is wide variation between the reactivity of published CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes, with some four- and five-coordinate species displaying greater HAT reactivity than others. This presumably arises from the nature of the supporting ligands, with charge appearing to be a major contributing factor, which implies that ligand design can be used to further enhance/tune reactivity. Crucially, we anticipate our observations of higher reactivity in similarly ligated four- vs five-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) complexes will hold true elsewhere. By extension, it is likely no coincidence that four-coordinate CuII(η1-O2•–) intermediates, not their five-coordinate congeners, are believed to be the active oxidants in noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases and FGE, where high oxidative capacities are required for hydroxylation of C–H bonds.

Acknowledgments

J.E. is grateful to NTU (M4081442, 000416-00001) and the Ministry of Education of Singapore (AcRF Tier 1 grant RG8/19 (S), 002689-00001) for funding. S.D. thanks the Max Planck Society and the European Research Council (Synergy Grant 856446) for funding. O.M.S. thanks the International Max Planck Society Research School Recharge for funding. The authors thank Dr. Yongxin Li of the SPMS (NTU) X-ray lab for measurement and refinement of X-ray crystallographic data. They also thank Anchisar Libuda for help with collecting Resonance Raman data. Chris Pollock is thanked for his help as the PIPOXS beamline scientist at Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source. The authors acknowledge the DJEI/DES/SFI/HEA Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC) for the provision of high-performance computing facilities and technical support. T.K. thanks Dr. Ragnar Bjornsson (CEA Grenoble) for insightful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c12268.

Author Contributions

∇ S.D. and S.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Solomon E. I.; Heppner D. E.; Johnston E. M.; Ginsbach J. W.; Cirera J.; Qayyum M.; Kieber-Emmons M. T.; Kjaergaard C. H.; Hadt R. G.; Tian L. Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3659–3853. 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quist D. A.; Diaz D. E.; Liu J. J.; Karlin K. D. Activation of dioxygen by copper metalloproteins and insights from model complexes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 253–288. 10.1007/s00775-016-1415-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J. P. The copper-enzyme family of dopamine β-monooxygenase and peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase: Resolving the chemical pathway for substrate hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3013–3016. 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel M. J.; Bertozzi C. R. Formylglycine, a Post-Translationally Generated Residue with Unique Catalytic Capabilities and Biotechnology Applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 72–84. 10.1021/cb500897w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisinger F.; Miarzlou D. A.; Seebeck F. P. Non-Coordinative Binding of O2 at the Active Center of a Copper-Dependent Enzyme. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6154–6159. 10.1002/anie.202014981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel M. J.; Meier K. K.; Lafrance-Vanasse J.; Lim H.; Tsai C.-L.; Hedman B.; Hodgson K. O.; Tainer J. A.; Solomon E. I.; Bertozzi C. R. Formylglycine-generating enzyme binds substrate directly at a mononuclear Cu(I) center to initiate O2 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 5370–5375. 10.1073/pnas.1818274116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miarzlou D. A.; Leisinger F.; Joss D.; Häussinger D.; Seebeck F. P. Structure of formylglycine-generating enzyme in complex with copper and a substrate reveals an acidic pocket for binding and activation of molecular oxygen. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 7049–7058. 10.1039/C9SC01723B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meury M.; Knop M.; Seebeck F. P. Structural Basis for Copper–Oxygen Mediated C–H Bond Activation by the Formylglycine-Generating Enzyme. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8115–8119. 10.1002/anie.201702901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendelboe T. V.; Harris P.; Zhao Y.; Walter T. S.; Harlos K.; El Omari K.; Christensen H. E. M. The crystal structure of human dopamine β-hydroxylase at 2.9 Å resolution. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500980 10.1126/sciadv.1500980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley R. E.; Tian L.; Solomon E. I. Mechanism of O2 activation and substrate hydroxylation in noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 12035–12040. 10.1073/pnas.1614807113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.; Solomon E. I. Oxygen Activation by the Noncoupled Binuclear Copper Site in Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase. Reaction Mechanism and Role of the Noncoupled Nature of the Active Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4991–5000. 10.1021/ja031564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch E. F.; Rush K. W.; Arias R. J.; Blackburn N. J. Copper monooxygenase reactivity: Do consensus mechanisms accurately reflect experimental observations?. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 231, 111780. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2022.111780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch E. F.; Rush K. W.; Arias R. J.; Blackburn N. J. Pre-Steady-State Reactivity of Peptidylglycine Monooxygenase Implicates Ascorbate in Substrate Triggering of the Active Conformer. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 665–677. 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush K. W.; Eastman K. A. S.; Welch E. F.; Bandarian V.; Blackburn N. J. Capturing the Binuclear Copper State of Peptidylglycine Monooxygenase Using a Peptidyl-Homocysteine Lure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5074–5080. 10.1021/jacs.3c14705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Fan F.; Song J.; Peng W.; Liu J.; Li C.; Cao Z.; Wang B. Theory Demonstrated a “Coupled” Mechanism for O2 Activation and Substrate Hydroxylation by Binuclear Copper Monooxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19776–19789. 10.1021/jacs.9b09172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge S. T.; Eipper B. A.; Mains R. E.; Amzel L. M. Dioxygen Binds End-On to Mononuclear Copper in a Precatalytic Enzyme Complex. Science 2004, 304, 864–867. 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder G. C.; O’Dell W. B.; Webb S. P.; Agarwal P. K.; Meilleur F. Capture of activated dioxygen intermediates at the copper-active site of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 13303–13320. 10.1039/D2SC05031E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M. M.; Hedegård E. D. Molecular Mechanism of Substrate Oxidation in Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases: Insight from Theoretical Investigations. Chem. - Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202202379. 10.1002/chem.202202379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissaro B.; Eijsink V. G. H. Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases: enzymes for controlled and site-specific Fenton-like chemistry. Essays Biochem. 2023, 67, 575–584. 10.1042/EBC20220250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg Z.; Sørlie M.; Petrović D.; Courtade G.; Aachmann F. L.; Vaaje-Kolstad G.; Bissaro B.; Røhr Å. K.; Eijsink V. G. H. Polysaccharide degradation by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 59, 54–64. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Walton P. H.; Rovira C. Molecular Mechanisms of Oxygen Activation and Hydrogen Peroxide Formation in Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 4958–4969. 10.1021/acscatal.9b00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissaro B.; Várnai A.; Åsmund K. R.; Eijsink V. G. H. Oxidoreductases and Reactive Oxygen Species in Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00029-18. 10.1128/MMBR.00029-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandrup T.; Frandsen K. E. H.; Johansen K. S.; Berrin J.-G.; Lo Leggio L. Recent insights into lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1431–1447. 10.1042/BST20170549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier K. K.; Jones S. M.; Kaper T.; Hansson H.; Koetsier M. J.; Karkehabadi S.; Solomon E. I.; Sandgren M.; Kelemen B. Oxygen Activation by Cu LPMOs in Recalcitrant Carbohydrate Polysaccharide Conversion to Monomer Sugars. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2593–2635. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.; Karlin K. D. Ligand–Copper(I) Primary O2-Adducts: Design, Characterization, and Biological Significance of Cupric–Superoxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 2197–2212. 10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell C. E.; Gagnon N. L.; Neisen B. D.; Dhar D.; Spaeth A. D.; Yee G. M.; Tolman W. B. Copper-Oxygen Complexes Revisited: Structures, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2059–2107. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirica L. M.; Ottenwaelder X.; Stack T. D. P. Structure and Spectroscopy of Copper-Dioxygen Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1013–1045. 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S.; Tachi Y. Structure and O2-reactivity of copper(I) complexes supported by pyridylalkylamine ligands. Dalton Trans. 2006, 4531–4538. 10.1039/b607964d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osako T.; Ueno Y.; Tachi Y.; Itoh S. Structures and Redox Reactivities of Copper Complexes of (2-Pyridyl)alkylamine Ligands. Effects of the Alkyl Linker Chain Length. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 8087–8097. 10.1021/ic034958h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas H. R.; Li L.; Sarjeant A. A. N.; Vance M. A.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. Toluene and Ethylbenzene Aliphatic C-H Bond Oxidations Initiated by a Dicopper(II)-μ-1,2-Peroxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3230–3245. 10.1021/ja807081d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahsini L.; Kotani H.; Lee Y.-M.; Cho J.; Nam W.; Karlin K. D.; Fukuzumi S. Electron-Transfer Reduction of Dinuclear Copper Peroxo and Bis-μ-oxo Complexes Leading to the Catalytic Four-Electron Reduction of Dioxygen to Water. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 1084–1093. 10.1002/chem.201103215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishita A.; Osako T.; Tachi Y.; Teraoka J.; Itoh S. Syntheses, structures, and O2-reactivities of copper(I) complexes with bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine and bis(2-quinolylmethyl)amine tridentate ligands. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 79, 1729–1741. 10.1246/bcsj.79.1729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osako T.; Terada S.; Tosha T.; Nagatomo S.; Furutachi H.; Fujinami S.; Kitagawa T.; Suzuki M.; Itoh S. Structure and dioxygen-reactivity of copper(I) complexes supported by bis(6-methylpyridin-2-ylmethyl)amine tridentate ligands. Dalton Trans. 2005, 3514–3521. 10.1039/b500202h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas H. R.; Meyer G. J.; Karlin K. D. CO and O2 Binding to Pseudo-tetradentate Ligand-Copper(I) Complexes with a Variable N-Donor Moiety: Kinetic/Thermodynamic Investigation Reveals Ligand-Induced Changes in Reaction Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12927–12940. 10.1021/ja104107q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa K.; Tanaka M.; Moro-oka Y.; Kitajima N. A Monomeric Side-On Superoxocopper(II) Complex: Cu(O2)(HB(3-tBu-5-iPrpz)3). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 12079–12080. 10.1021/ja00105a069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer D. J. E.; Aboelella N. W.; Reynolds A. M.; Holland P. L.; Tolman W. B. β-Diketiminate Ligand Backbone Structural Effects on Cu(I)/O2 Reactivity: Unique Copper-Superoxo and Bis(μ-oxo) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2108–2109. 10.1021/ja017820b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboelella N. W.; Lewis E. A.; Reynolds A. M.; Brennessel W. W.; Cramer C. J.; Tolman W. B. Snapshots of Dioxygen Activation by Copper: The Structure of a 1:1 Cu/O2 Adduct and Its Use in Syntheses of Asymmetric Bis(μ-oxo) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 10660–10661. 10.1021/ja027164v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A. M.; Gherman B. F.; Cramer C. J.; Tolman W. B. Characterization of a 1:1 Cu-O2 Adduct Supported by an Anilido Imine Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 6989–6997. 10.1021/ic050280p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovan D. A.; Wrobel A. T.; McClelland A. A.; Scharf A. B.; Edouard G. A.; Betley T. A. Reactivity of a stable copper–dioxygen complex. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 10306–10309. 10.1039/C7CC05014C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carsch K. M.; Iliescu A.; McGillicuddy R. D.; Mason J. A.; Betley T. A. Reversible Scavenging of Dioxygen from Air by a Copper Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18346–18352. 10.1021/jacs.1c10254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi R.; Aboelella N.; Fujisawa K.; Tolman W. B.; Hedman B.; Hodgson K. O.; Solomon E. I. X-ray Absorption Edge Spectroscopy and Computational Studies on LCuO2 Species: Superoxide-CuII versus Peroxide-CuIII Bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8286–8296. 10.1021/ja0615223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboelella N. W.; Kryatov S. V.; Gherman B. F.; Brennessel W. W.; Young V. G. Jr.; Sarangi R.; Rybak-Akimova E. V.; Hodgson K. O.; Hedman B.; Solomon E. I.; Cramer C. J.; Tolman W. B. Dioxygen Activation at a Single Copper Site: Structure, Bonding, and Mechanism of Formation of 1:1 Cu-O2 Adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16896–16911. 10.1021/ja045678j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue P. J.; Gupta A. K.; Boyce D. W.; Cramer C. J.; Tolman W. B. An Anionic, Tetragonal Copper(II) Superoxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15869–15871. 10.1021/ja106244k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishita A.; Kubo M.; Sugimoto H.; Ogura T.; Sato K.; Takui T.; Itoh S. Mononuclear Copper(II)-Superoxo Complexes that Mimic the Structure and Reactivity of the Active Centers of PHM and DβM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2788–2789. 10.1021/ja809464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T.; Hori Y.; Shiota Y.; Ohta T.; Morimoto Y.; Sugimoto H.; Ogura T.; Yoshizawa K.; Itoh S. Cupric-superoxide complex that induces a catalytic aldol reaction-type C–C bond formation. Commun. Chem. 2019, 2, 12. 10.1038/s42004-019-0115-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schön F.; Biebl F.; Greb L.; Leingang S.; Grimm-Lebsanft B.; Teubner M.; Buchenau S.; Kaifer E.; Rübhausen M. A.; Himmel H.-J. On the Metal Cooperativity in a Dinuclear Copper–Guanidine Complex for Aliphatic C–H Bond Cleavage by Dioxygen. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11257–11268. 10.1002/chem.201901906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaikowski M. E.; McNeece A. J.; Boyn J.-N.; Jesse K. A.; Anferov S. W.; Filatov A. S.; Mazziotti D. A.; Anderson J. S. Generation and Aerobic Oxidative Catalysis of a Cu(II) Superoxo Complex Supported by a Redox-Active Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 15569–15580. 10.1021/jacs.2c04630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey W. D.; Dhar D.; Cramblitt A. C.; Tolman W. B. Mechanistic Dichotomy in Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer Reactions of Phenols with a Copper Superoxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5470–5480. 10.1021/jacs.9b00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey W. D.; Gagnon N. L.; Elwell C. E.; Cramblitt A. C.; Bouchey C. J.; Tolman W. B. Revisiting the Synthesis and Nucleophilic Reactivity of an Anionic Copper Superoxide Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 4706–4711. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirovano P.; Magherusan A. M.; McGlynn C.; Ure A.; Lynes A.; McDonald A. R. Nucleophilic Reactivity of a Copper(II)-Superoxide Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5946–5950. 10.1002/anie.201311152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S. Developing Mononuclear Copper-Active-Oxygen Complexes Relevant to Reactive Intermediates of Biological Oxidation Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2066–2074. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishita A.; Ertem M. Z.; Okubo Y.; Tano T.; Sugimoto H.; Ohkubo K.; Fujieda N.; Fukuzumi S.; Cramer C. J.; Itoh S. Active Site Models for the CuA Site of Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase and Dopamine β-Monooxygenase. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 9465–9480. 10.1021/ic301272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tano T.; Okubo Y.; Kunishita A.; Kubo M.; Sugimoto H.; Fujieda N.; Ogura T.; Itoh S. Redox Properties of a Mononuclear Copper(II)-Superoxide Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10431–10437. 10.1021/ic401261z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh H.; Cho J. Synthesis, characterization and reactivity of non-heme 1st row transition metal-superoxo intermediates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 382, 126–144. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W. Structure and reactivity of the first-row d-block metal-superoxo complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 9469–9489. 10.1039/C9DT01402K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek S. Y.; Debnath S.; Laxmi S.; van Gastel M.; Krämer T.; England J. Sterically Stabilized End-On Superoxocopper(II) Complexes and Mechanistic Insights into Their Reactivity with O–H, N–H, and C–H Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 19731–19747. 10.1021/jacs.1c07837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Powell D. R.; Houser R. P. Structural variation in copper(i) complexes with pyridylmethylamide ligands: structural analysis with a new four-coordinate geometry index, τ4. Dalton Trans. 2007, 955–964. 10.1039/B617136B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki Y.; Yokoyama H.; Yamauchi O. Copper(I) Complexes with a Proximal Aromatic Ring: Novel Copper–Indole Bonding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2401–2403. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti D.; Day M. W.; Agapie T. Metal-templated ligand architectures for trinuclear chemistry: tricopper complexes and their O2 reactivity. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 785–790. 10.1039/C2SC21758A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. T.; Braun-Cula B.; Hoof S.; Dürr M.; Ivanović-Burmazović I.; Limberg C. Ligands with Two Different Binding Sites and O2 Reactivity of their Copper(I) Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4017–4027. 10.1002/ejic.201600420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addison A. W.; Rao T. N.; Reedijk J.; van Rijn J.; Verschoor G. C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. 10.1039/DT9840001349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelli T. G.; Rahaman S. M. W.; Daran J. C.; Krys P.; Matyjaszewski K.; Poli R. Effect of Ligand Structure on the CuII–R OMRP Dormant Species and Its Consequences for Catalytic Radical Termination in ATRP. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 7749–7757. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. L.; Himes R. A.; Kotani H.; Suenobu T.; Tian L.; Siegler M. A.; Solomon E. I.; Fukuzumi S.; Karlin K. D. Cupric Superoxo-Mediated Intermolecular C-H Activation Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1702–1705. 10.1021/ja110466q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woertink J. S.; Tian L.; Maiti D.; Lucas H. R.; Himes R. A.; Karlin K. D.; Neese F.; Würtele C.; Holthausen M. C.; Bill E.; Sundermeyer J.; Schindler S.; Solomon E. I. Spectroscopic and Computational Studies of an End-on Bound Superoxo-Cu(II) Complex: Geometric and Electronic Factors That Determine the Ground State. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9450–9459. 10.1021/ic101138u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. L.; Ginsbach J. W.; Cowley R. E.; Qayyum M. F.; Himes R. A.; Siegler M. A.; Moore C. D.; Hedman B.; Hodgson K. O.; Fukuzumi S.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. Stepwise Protonation and Electron-Transfer Reduction of a Primary Copper-Dioxygen Adduct. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16454–16467. 10.1021/ja4065377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz M.; Raab V.; Foxon S. P.; Brehm G.; Schneider S.; Reiher M.; Holthausen M. C.; Sundermeyer J.; Schindler S. Dioxygen complexes: Combined spectroscopic and theoretical evidence for a persistent end-on copper superoxo complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4360–4363. 10.1002/anie.200454125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra M.; Transue W. J.; Lim H.; Cowley R. E.; Lee J. Y. C.; Siegler M. A.; Josephs P.; Henkel G.; Lerch M.; Schindler S.; Neuba A.; Hodgson K. O.; Hedman B.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. A Thioether-Ligated Cupric Superoxide Model with Hydrogen Atom Abstraction Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3707–3713. 10.1021/jacs.1c00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanci M. P.; Smirnov V. V.; Cramer C. J.; Gauchenova E. V.; Sundermeyer J.; Roth J. P. Isotopic Probing of Molecular Oxygen Activation at Copper(I) Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14697–14709. 10.1021/ja074620c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. M.; Shahi A. R. M.; Aquilante F.; Cramer C. J.; Gagliardi L. What Active Space Adequately Describes Oxygen Activation by a Late Transition Metal? CASPT2 and RASPT2 Applied to Intermediates from the Reaction of O2 with a Cu(I)-α-Ketocarboxylate. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 2967–2976. 10.1021/ct900282m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson E. D.; Dong G.; Veryazov V.; Ryde U.; Hedegård E. D. Is density functional theory accurate for lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase enzymes?. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 1501–1512. 10.1039/C9DT04486H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paria S.; Ohta T.; Morimoto Y.; Sugimoto H.; Ogura T.; Itoh S. Structure and Reactivity of Copper Complexes Supported by a Bulky Tripodal N4 Ligand: Copper(I)/Dioxygen Reactivity and Formation of a Hydroperoxide Copper(II) Complex. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2018, 644, 780–789. 10.1002/zaac.201800083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra M.; Lee J. Y. C.; Cowley R. E.; Kim S.; Siegler M. A.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding Enhances Stability and Reactivity of Mononuclear Cupric Superoxide Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9042–9045. 10.1021/jacs.8b04671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz D. E.; Quist D. A.; Herzog A. E.; Schaefer A. W.; Kipouros I.; Bhadra M.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. Impact of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding on the Reactivity of Cupric Superoxide Complexes with O–H and C–H Substrates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17572–17576. 10.1002/anie.201908471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. J.; Cho K.-B.; Kubo M.; Ogura T.; Karlin K. D.; Cho J.; Nam W. Spectroscopic and computational characterization of CuII-OOR (R = H or cumyl) complexes bearing a Me6-tren ligand. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 2234–2241. 10.1039/c0dt01036g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S.; Nagatomo S.; Kitagawa T.; Funahashi Y.; Ozawa T.; Jitsukawa K.; Masuda H. Copper Hydroperoxo Species Activated by Hydrogen-Bonding Interaction with Its Distal Oxygen. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 6968–6970. 10.1021/ic035080x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishita A.; Scanlon J. D.; Ishimaru H.; Honda K.; Ogura T.; Suzuki M.; Cramer C. J.; Itoh S. Reactions of Copper(II)-H2O2 Adducts Supported by Tridentate Bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine Ligands: Sensitivity to Solvent and Variations in Ligand Substitution. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 8222–8232. 10.1021/ic800845h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y.; Peterson R. L.; Ohkubo K.; Garcia-Bosch I.; Himes R. A.; Woertink J.; Moore C. D.; Solomon E. I.; Fukuzumi S.; Karlin K. D. Mechanistic Insights into the Oxidation of Substituted Phenols via Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by a Cupric-Superoxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9925–9937. 10.1021/ja503105b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram M. S.; Hupp J. T. Linear free energy relations for multielectron transfer kinetics: a brief look at the Broensted/Tafel analogy. J. Phys. Chem. A 1990, 94, 2378–2380. 10.1021/j100369a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherly S. C.; Yang I. V.; Thorp H. H. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Duplex DNA: Driving Force Dependence and Isotope Effects on Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Guanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1236–1237. 10.1021/ja003788u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osako T.; Ohkubo K.; Taki M.; Tachi Y.; Fukuzumi S.; Itoh S. Oxidation mechanism of phenols by dicopper-dioxygen (Cu2/O2) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11027–11033. 10.1021/ja029380+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttenplan J. B.; Cohen S. G. Triplet energies, reduction potentials, and ionization potentials in carbonyl-donor partial charge-transfer interactions. I.. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 4040–4042. 10.1021/ja00766a079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P. J.; Lam H. M. H. Charge-transfer quenching of triplet.alpha.-trifluoroacetophenones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4167–4172. 10.1021/ja00532a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J. J.; Tronic T. A.; Mayer J. M. Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961–7001. 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.-Q.; Zhang M.-T.; Yu A.; Wang C.-H.; Cheng J.-P. Hydride, Hydrogen Atom, Proton, and Electron Transfer Driving Forces of Various Five-Membered Heterocyclic Organic Hydrides and Their Reaction Intermediates in Acetonitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2501–2516. 10.1021/ja075523m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Lee J. Y.; Cowley R. E.; Ginsbach J. W.; Siegler M. A.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. A N3S(thioether)-Ligated CuII-Superoxo with Enhanced Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2796–2799. 10.1021/ja511504n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.