Abstract

Human sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) are expressed on subsets of immune cells. Siglec-8 is an immune inhibitory Siglec on eosinophils and mast cells, which are effectors in allergic disorders including eosinophilic esophagitis. Inhibition occurs when Siglec-8 is crosslinked by multivalent Siglec ligands in target tissues. Previously we discovered a high-affinity Siglec-8 sialoglycan ligand on human airways composed of terminally sialylated keratan sulfate chains carried on a single protein, DMBT1. Here we extend that approach to another allergic inflammatory target tissue, human esophagus. Lectin overlay histochemistry revealed that Siglec-8 ligands are expressed predominantly by esophageal submucosal glands, and are densely packed in submucosal ducts leading to the lumen. Expression is tissue-specific; esophageal glands express Siglec-8 ligand whereas nearby gastric glands do not. Extraction and resolution by gel electrophoresis revealed a single predominant human esophageal Siglec-8 ligand migrating at >2 MDa. Purification by size exclusion and affinity chromatography, followed by proteomic mass spectrometry, revealed the protein carrier to be MUC5B. Whereas all human esophageal submucosal cells express MUC5B, only a portion convert it to Siglec-8 ligand by adding terminally sialylated keratan sulfate chains. We refer to this as MUC5B S8L. Material from the esophageal lumen of live subjects revealed MUC5B S8L species ranging from ~1–4 MDa. We conclude that MUC5B in the human esophagus is a protein canvas on which Siglec-8 binding sialylated keratan sulfate chains are post-translationally added. These data expand understanding of Siglec-8 ligands and may help us understand their roles in allergic immune regulation.

Keywords: keratan sulfate, mucin, sialic acid, Siglec, submucosal gland

Introduction

Siglecs, sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins, are a family of 14 transmembrane receptors in humans, most of which are expressed on overlapping sets of immune cells and most of which are immune inhibitory (O’Sullivan et al. 2023). Siglec-8, expressed on human eosinophils and mast cells, is of special interest in allergic and other diseases in which those cells drive pathology (Galli et al. 2020; Wechsler et al. 2021). Eosinophils and mast cells are both linked to airway disorders including asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases including eosinophilic esophagitis, gastroenteritis and colitis. Since Siglec-8 engagement initiates an immune inhibitory response, Siglec-8 has been targeted therapeutically in these and other eosinophilic and mast cell related diseases (O’Sullivan et al. 2023). Humanized antibody against Siglec-8 results in its crosslinking on eosinophil and mast cell surfaces leading to eosinophil apoptosis and inhibition of mast cell mediator release (Youngblood et al. 2020). It has been proposed that physiological control of inflammation is induced when Siglec-8 is crosslinked by endogenous sialoglycan ligands (Propster et al. 2016; Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2023). Purification and identification of unique large (1 MDa) and highly glycosylated Siglec-8 ligands from human airways (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2021) and human brain parenchyma (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2022) support this scenario. Siglec-8 ligand from each source comprises a single predominant sialoglycoprotein with Siglec-8 binding determinants carried on sialylated keratan sulfate chains. Surprisingly, the unique protein carrier from each source is different – DMBT1 on airways and RPTPζ in the brain. Understanding the native ligands for Siglec-8, control of their expression, and their mechanisms of action contributes to a more complete appreciation of the pathophysiology of this immune inhibitory pathway and may provide insights to better target the pathway in disease. To this end, the study of endogenous human ligands for Siglec-8 was extended to the human esophagus, a target of eosinophilic inflammatory disease (Furuta and Katzka 2015).

The human esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, ~24 cm in length, extending from the pharynx to the stomach through which food passes (Connor et al. 2020). Its lumen is lined by a stratified epithelium supported by a lamina propria and a thin layer of smooth muscle (muscularis mucosa). These layers are surrounded by a submucosa and then outer muscle layers (muscularis propria). Among inflammatory diseases of the esophagus is eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), a relatively prevalent cause of feeding problems in children and dysphagia and food impaction in adults (Furuta and Katzka 2015). Whereas eosinophils are typically absent in normal esophageal mucosa, histological diagnosis of EoE is based on the presence of significant numbers of eosinophils in the epithelium, which may also appear as superficial eosinophil layers or eosinophilic abscesses on esophageal biopsy tissue (Gonsalves et al. 2006). Notably, the presence of mast cells along with the eosinophils correlates with disease-associated pain in EoE (Zhang et al. 2022). To extend our studies of Siglec-8 ligands of tissues that are subject to diseases related to Siglec-8 bearing immune cells, we report here the characteristics of Siglec-8 ligand in the human esophagus.

Results

Distribution of Siglec-8 sialoglycan ligands in human esophagus

Distal esophagus from human donors was fixed, paraffin embedded, and 5 μm cross sections captured on glass slides. Serial cross sections were: (i) stained with hematoxylin and eosin to identify characteristic esophageal histological structures; (ii) Overlaid with Siglec-8-Fc to detect Siglec-8 ligands; and (iii) pretreated with sialidase, then overlaid with Siglec-8-Fc to determine sialic acid dependent Siglec-8-Fc binding (Fig. 1). The major histological finding was the robust presence of Siglec-8 ligands in esophageal submucosal glands (Fig. 1B). Submucosal gland staining was dependent on Siglec-8-Fc (Fig. 1C) and was reversed by pretreatment with sialidase (Fig. 1F). Esophageal submucosal gland ducts orient toward the lumen to carry protective substances onto the esophageal epithelium (Sarosiek and McCallum 2000). Staining of an esophageal cross section where glands and ducts are both readily visible (Fig. 1D–F) revealed that Siglec-8-ligand densely populates the duct, presumably in transit to the lumen where it encounters Siglec-8 bearing immune cells.

Fig. 1.

Esophageal submucosal glands express a sialidase-sensitive Siglec-8 ligand. Postmortem human esophagus was dissected, fixed and paraffin embedded. Cross sections of distal esophagus were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and D) to identify characteristic esophageal structures, longitudinal muscle (LM), circular muscle (CM), submucosa (S), muscularis mucosae (MM), epithelium (EP), and lumen (L). To detect Siglec-8 ligands, sections were incubated with Siglec-8-Fc (B) or human IgG isotype control (C), each premixed with anti-human Fc secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). After incubation and washing, binding was detected with diaminobenzidine (DAB). To detect sialidase sensitive Siglec-8 ligands, tissue sections were pre-incubated with PBS as control (E) or with sialidase A (F), washed, and then incubated with Siglec-8-Fc pre-mixed with anti-human Fc secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP) and signal detected with Vector Red AP substrate followed by hematoxylin counterstain. Expression of Siglec-8 ligand is observed on esophageal submucosal glands and ducts, and is sialidase sensitive.

Submucosal gland densities vary along the proximal-to-distal axis of the human esophagus (Long and Orlando 1999). This was apparent in esophageal cross sections from a single donor collected from mid-esophagus to distal sections nearest the stomach (Supplementary Fig. 1). Throughout the length of the human esophagus, submucosal glands stained robustly for Siglec-8 ligand with no other structures as distinctly stained in the multiple layers of the fibromuscular tube.

Esophageal submucosal secretions are rich in acid mucins along with other glycoproteins, bicarbonate and non-bicarbonate buffers, and protective growth factors (Sarosiek and McCallum 2000). Since Alcian Blue staining is commonly used to view acidic mucins, including in submucosal glands, we compared Alcian Blue staining with Siglec-8-Fc overlay staining for Siglec-8 ligands in a far distal esophageal cross section, rich in submucosal glands, just proximal to the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 2). Siglec-8 ligand histochemical distribution correlated precisely with esophageal submucosal glands and ducts stained with Alcian Blue. In contrast, it was absent from other Alcian Blue stained structures. The gastroesophageal junction is marked by an abrupt change from a lumen bounded by squamous epithelium to one bounded by columnar epithelium. Whereas Siglec-8 ligand is abundant on the esophageal side of this divide, it is completely absent on the stomach side (Fig. 2A and B). At higher magnification (Fig. 2D and E) structures stained with Alcian Blue with morphologies matching esophageal submucosal glands and ducts are well-stained with Siglec-8-Fc, whereas nearby structures with morphologies of gastric glands completely lack Siglec-8 ligands.

Fig. 2.

Esophageal but not gastric mucus-secreting glands express Siglec-8-ligand. Human esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) was dissected, fixed and paraffin embedded. A serial cross section was stained with Alcian Blue to detect mucin-producing glands and associated ducts (A and D). A serial cross section was overlaid with Siglec-8-Fc (B and E) or human IgG control (C and F), each precomplexed with HRP-conjugated anti-human-Fc. Siglec ligand signal was detected with DAB. Siglec-8 ligand was observed in esophageal submucosal glands (SMG), and glandular ducts but absent in mucus-producing gastric glands (*).

Extraction of Siglec-8 ligands from human esophagus

Postmortem human esophagus that included all tissue layers from the epithelium to the longitudinal muscle were extracted under stringent conditions (6 M guanidinium hydrochloride, GuHCl) to maximize protein solubilization. Proteins were dialyzed into urea-containing buffer to accommodate gel electrophoresis, resolved on composite agarose-polyacrylamide gels, blotted and Siglec-8 ligands detected by Siglec-8-Fc overlay. Extracts of two transverse sections from each of 3 organ donors revealed variable amounts of a very large molecular weight Siglec-8 ligand (>2 million daltons, Fig. 3A). In most extracts, only a single molecular weight species was detected. When equal aliquots based on tissue wet weight were resolved, large differences in both Siglec-8-Fc binding intensity and total protein extracted (Fig. 3B) were observed. Siglec-8-Fc binding intensity did not correlate with total protein in extracts, even in samples from the same donor. We interpret these data as indicating that there is great variation in the amount of Siglec-8 ligand expressed between individuals and/or along the length of the esophagus in the same individual, consistent with the variability of inter-subject density and lengthwise distribution of esophageal submucosal glands (Long and Orlando 1999), which may be the source of much of the Siglec-8 ligand in postmortem human esophagus (Figs 1 and 2). Another notable conclusion is that all Siglec-8 ligand detected in stringently extracted human postmortem esophagus migrates at >2 MDa.

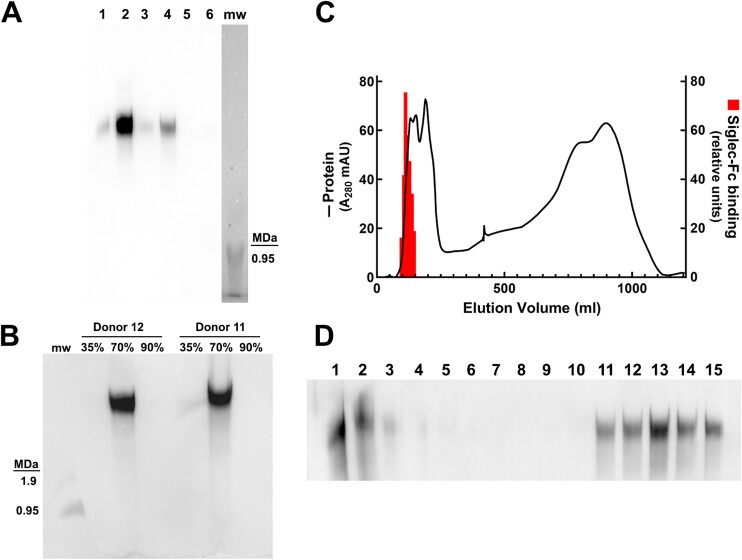

Fig. 3.

Siglec ligand in human esophagus extracts. Transverse tissue rings were dissected from postmortem distal esophagi at two proximal-to-distal levels from each of three tissue donors. Tissues were flash frozen, pulverized, and extracted with GuHCl-containing extraction buffer. Aliquots were dialyzed into urea-containing buffer and subjected to gel electrophoresis. A) Proteins were resolved by composite agarose-polyacrylamide SDS gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with Siglec-8-Fc to detect Siglec-8 ligands via enhanced chemiluminescence. The entire length of the gel blot is shown, with an arrow designating the front. A custom molecular weight marker (m) consisting of crosslinked prelabeled IgM was run on the same gel in an adjacent lane that was imaged using white light. B) Aliquots of the same samples were resolved by 4%–12% polyacrylamide SDS gels electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue as protein loading controls. Lanes 1–2, donor 2; lanes 3–4, donor 3; lanes 5–6, donor 4.

Purification of Siglec-8 ligands from human esophagus

Consistent with ligand histochemistry, most of the Siglec-8 ligand was found in the more luminal tissue layers (Fig. 4A). Based on these findings, the inner esophageal layers (epithelium to submucosa) were separately collected and stringently extracted. Subsequent ethanol precipitation separated large, charged ligands from smaller proteins and solutes, with nearly all of the ligand captured by 70% ethanol precipitation (Fig. 4B). The precipitate was solubilized and subjected to size-exclusion chromatography using Sephacryl S-500 to separate proteins over a range of 40 kDa to several MDa. Siglec-8 ligand eluted with a minority of the protein near the excluded volume (Fig. 4C). Fractions containing Siglec-8 ligand were combined, concentrated and captured on beads covalently derivatized with Siglec-8-Fc, with ligand eluted using high salt (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Purification of human esophageal Siglec-8 ligand. A) Freshly isolated post-mortem human distal esophagi were blunt dissected to separate the inner esophageal layer (epithelium and submucosa) from the outer esophageal tissue layer (muscle). Both portions were extracted in 6 M GuHCl, dialyzed into urea-containing buffer, resolved by composite agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blotted with Siglec-8-Fc precomplexed with HRP-conjugated anti-human-Fc that was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence. Data from two donors are shown, with odd numbered lanes representing muscle layers and even numbered lanes epithelial/submucosal layers. Lanes 5–6 were loaded with re-extracted insoluble residue from the same tissues as lanes 3–4, demonstrating near complete recovery in the first extraction. B) The epithelial/submucosal layer extract from two donors, were sequentially precipitated with 35%, 70%, and 90% ethanol, the pellet solubilized in GuHCl and a small portion dialyzed against urea containing buffer, resolved by composite agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF, and blotted with Siglec-8-Fc precomplexed with HRP-conjugated anti-human-Fc. C) Solubilized 70% ethanol-precipitated sample was buffer exchanged to size exclusion buffer (containing 4 M GuHCl) and resolved on a Sephacryl S-500 size exclusion column. Fractions were collected and analyzed by semi-quantitative dot-blotting with Siglec-8-Fc. Protein elution (A280, line) and Siglec-8 ligand (bars) are plotted against elution volume. D) Fractions containing Siglec-8 ligand were combined and concentrated, cleared with protein G beads, then affinity-captured by Siglec-8-Fc on protein G beads, washed and salt-eluted. Lanes: 1, pre-column; 2, precleared; 3–4, wash buffer; 5–15, stepwise NaCl gradient in urea buffer as follows: 5–6, 25 mM; 7–8, 50 mM; 9–10, 75 mM; 11–12, 100 mM; 13–14, 150 mM; 15, 1 M.

MUC5B carries Siglec-8 ligands in the human esophagus

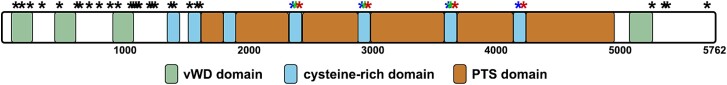

Siglec-8 ligand that was purified from postmortem human esophagus in duplicate preparations was subjected to proteomic MS (see Supplemental Data). Sorting by Proteome Discoverer 3.1 Sequest HT score, of the top 25 proteins identified in duplicate experiments there are only 2 potential protein carriers of the Siglec-8 ligand after elimination of proteins used in purification and common MS contaminants (Mellacheruvu et al. 2013). The two potential carriers were MUC5B and fibrillin-1. MUC5B has a polypeptide molecular weight of 596 kDa and >1,600 potential O-glycosylation sites (Julenius et al. 2005). Since 80%–90% of its molecular weight can be carried as glycans, its total mass can be ~3–6 MDa. In contrast, fibrillin-1 has a polypeptide mass of 312 kDa and 118 potential O-glycosylation sites and has not been reported to migrate >500 kDa upon gel electrophoresis. We therefore focused on MUC5B as the likely carrier of Siglec-8 ligand in the human esophagus. In duplicate purifications 30 unique MUC5B peptides were identified (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2). Since some of these are found in repeat sequences, 38 peptide sites were identified stretching across the entire MUC5B sequence. As predicted, all of these peptides, which are identified in proteomic MS based on their non-glycosylated masses, were from regions devoid of predicted glycosylation and not from highly glycosylated proline, threonine, serine rich (PTS) repeat domains.

Fig. 5.

MUC5B is the protein carrier of Siglec-8 ligand from human esophagus. A map of human MUC5B (UniProtKB: Q9HC84) with domains as reported by the mucin biology groups, Gothenburg, Sweden (https://www.medkem.gu.se/mucinbiology). Asterisks denote peptides identified by proteomic mass spectrometry (Supplementary Table 2). Colored asterisks denote peptide sequences repeated in consecutive cysteine-rich domains.

The identification of MUC5B as the carrier of Siglec-8 ligand in the human esophagus was supported by electrophoretic co-migration. Purified human esophageal Siglec-8 ligand was subjected to agarose-polyacrylamide electrophoresis, blotted to nitrocellulose, then the blot was double-labeled with Siglec-8-Fc to locate the Siglec-8 ligand and α-MUC5B (Fig. 6). The two stains precisely overlapped in the high molecular weight region.

Fig. 6.

Comigration of Siglec-8-Fc binding and anti-MUC5B immunostaining in purified human esophageal Siglec-8 ligand. Siglec-8 ligand purified from postmortem human esophagus was resolved by agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotted to PVDF, and double-probed with Siglec-8-Fc to detect Siglec-8 ligand (lane 1) and anti-MUC5B antibody (lane 2). The high-molecular weight bands precisely overlaid (lane 3).

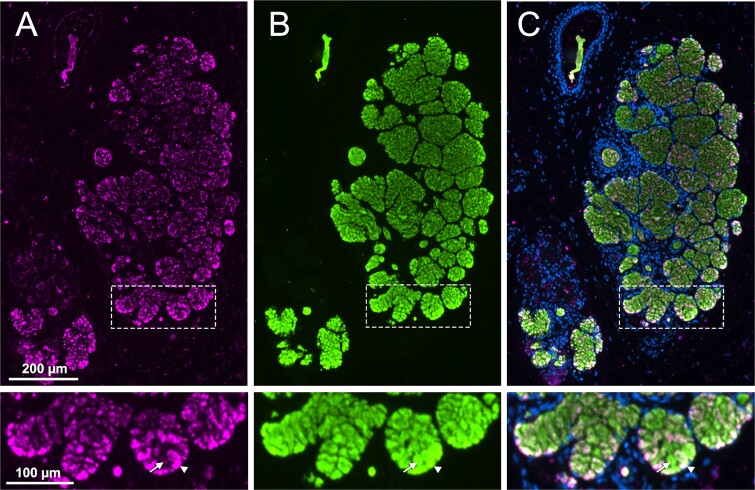

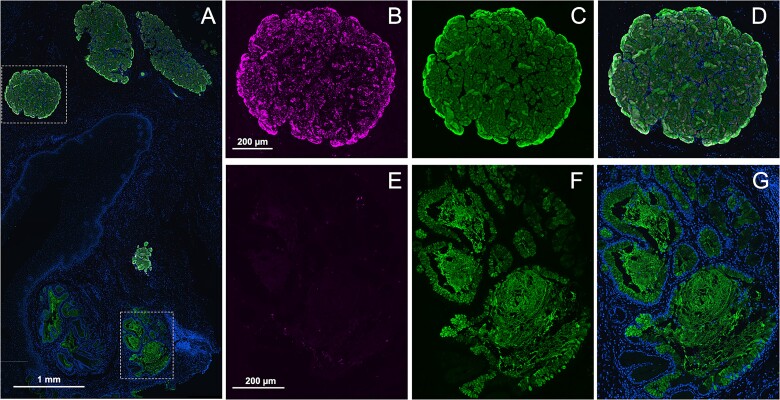

Histological colocalization also supported MUC5B as carrier of Siglec-8 ligands, but revealed cell-to-cell variation in the degree of Siglec-8-binding glycan carried by MUC5B (Fig. 7). Essentially every cell in human esophageal submucosal ancini is stained with α-MUC5B antibody (Fig. 7B), the intensity varies acinus-to-acinus and cell-to-cell, with the most intense staining often of cells at the periphery of the acinus. Staining with Siglec-8-Fc is more variable, with many cells within an acinus not expressing Siglec-8 ligand and intense staining of many cells on the periphery of the acinus (Fig. 7A). At higher magnification, adjacent cells in the submucosal gland acinus may express high levels of MUC5B, with one expressing equally high levels of Siglec-8 ligand and the other none at all. These data emphasize that Siglec-8 ligand is a post-translational modification under the control of selectively expressed biosynthetic enzymes. This finding was further emphasized by double-labeling the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 8). The lumen of the esophagus is bordered by a stratified squamous epithelium which abruptly changes to a columnar epithelium at the border with the stomach. Whereas esophageal glands are co-stained with α-MUC5B and Siglec-8-Fc (Fig. 8B and C), nearby stomach structures expressing MUC5B express no Siglec-8 ligand (Fig. 8E and F). We designate the subset of MUC5B mucin that carries Siglec-8 ligands as MUC5BS8L, consistent with past nomenclature recommendations (Taylor et al. 2022).

Fig. 7.

Expression of Siglec-8 ligand and MUC5B in human esophageal submucosal glands. Cross sections of human esophagus were incubated first with Siglec-8-Fc precomplexed with unconjugated anti-human-Fc and anti-MUC5B antibody, and then with corresponding secondary antibodies with different fluorophores. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. A) Siglec-8-Fc overlay; B) anti-MUC5B; C) merge. Bottom panels: Arrowhead, cell that expresses MUC5B and Siglec-8 ligand; arrow, cell expressing MUC5B that does not express Siglec-8-ligand.

Fig. 8.

Expression of MUC5B and Siglec-8 ligand at the gastroesophageal junction. A cross section of distal esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction was co-stained with anti-MUC5B and Siglec-8-Fc) precomplexed with unconjugated goat anti-human Fc detected with different fluorescent antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. A) Merged channels of a portion of the esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction. B–D) A single esophageal gland magnified to show Siglec-8-Fc overlay (B), anti-MUC5B overlay (C), and merged (D). E–G) Gastric glands magnified to show Siglec-8-Fc overlay (E), anti-MUC5B overlay (F), and merged (G). Siglec-8 ligand appears in the esophageal but not the gastric gland.

Sialylated keratan sulfate chains are Siglec-8 ligands on human esophageal MUC5B

Prior studies identified the key glycan binding determinant for Siglec-8 binding as Neu5Acα2–3(6-SO4)Galβ1-4GlcNAc, which in airways and brain is carried on sialylated keratan sulfate (KS) chains as the di-sulfated trisaccharide Neu5Acα2-3(6-SO4)Galβ1-4(6-SO4)GlcNAc (Propster et al. 2016; Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2023). To test whether the esophageal ligand likewise was a sialylated KS, Siglec-8 ligand purified from postmortem human esophagus was pretreated with sialidases or keratanase I prior to agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotting and detection using α-MUC5B antibody or Siglec-8-Fc overlay. Treatment with α2,3-selective sialidase resulted in a decrease in migration but no decrease in immunostaining with α-MUC5B (Fig. 9A). Treatment with a pan-sialic acid sialidase resulted in a greater decrease in motility but no decrease in α-MUC5B staining. We interpret these data as indicating that a significant amount of negative charge on MUC5B is removed by these treatments, slowing electrophoretic migration. Both treatments completely eliminated Siglec-8-Fc binding. Likewise, treatment with keratanase I reduced migration of α-MUC5B immunostaining, indicating that the purified Siglec-8 ligand carried sufficient sulfated KS chains to alter electrophoretic migration (Fig. 9B). Like sialidases, treatment with keratanase I eliminated Siglec-8-Fc binding. Treatment with chondroitinase, keratanase II or PNGase did not eliminate Siglec-8-Fc binding (data not shown). These data indicate that the human esophageal Siglec-8 ligand, like those from airways and brain, are sialylated keratan sulfate chains.

Fig. 9.

Esophageal Siglec-8 ligand is an α2-3 linked sialylated keratan sulfate. A) Sialidase treatment of MUC5BS8L. Siglec ligand purified from postmortem human esophagus was pre-treated with recombinant α2-3 specific sialidase (neuraminidase S, lanes 1), broad-specificity sialidase (neuraminidase A, lanes 2) or buffer alone (lanes 3). After treatment, aliquots were resolved by agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on replicate gels, blotted to PVDF, and probed with anti-MUC5B and Siglec-8-Fc as indicated. B) Keratanase I treatment of MUC5BS8L. Siglec ligand was pre-treated with keratanase (lanes 1) or buffer alone (lanes 2). Aliquots were resolved by electrophoresis on replicate gels, blotted, and probed with anti-MUC5B and Siglec-8-Fc as indicated. Molecular weight probe (m) consisted of crosslinked IgM.

MUC5BS8L from esophageal mucus collected from live human subjects

The detection of Siglec-8 ligand in postmortem human esophageal submucosal glands and in their attached ducts is consistent with MUC5BS8L secretion into the esophageal lumen. To test this hypothesis, small quantities of esophageal swab fluid from live human subjects were resolved by agarose-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotted to nitrocellulose, and double probed with α-MUC5B and Siglec-8-Fc (Fig. 10). Volunteers performed an Esophageal String Test (EST) by swallowing capsules containing an adsorptive woven nylon string, that when withdrawn from the esophagus captures a liquid biopsy containing luminal secretions, inflammatory and epithelial cells (Ackerman et al. 2019). After recovery, elution and centrifugation to remove particulate matter, proteins in the remaining fluid were electrophoretically resolved and double-stained. Although the results were variable subject-to-subject, double-stained entities were observed in each sample. Notably, these were of varying molecular weights (via electrophoretic migration) with the most intense double-labeled bands migrating near 1 MDa along with minor species at higher molecular weights. Given their robust staining with α-MUC5B antibody, the faster migrating double-stained bands are consistent with proteolytic fragments of MUC5B.

Fig. 10.

MUC5BS8L in the esophageal lumen. Three subjects (numbered 1–3, subjects 33, 39 and 43 respectively, Supplementary Table 1) with eosinophilic esophagitis performed an EST by swallowing a weighted capsule containing a woven nylon string, which was later withdrawn (Ackerman et al. 2019). Material adsorbed to the string was eluted, the eluate further solubilized with loading buffer, and equivalent volumes resolved by composite agarose-acrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and double-label probed with Siglec-8-Fc pre-conjugated to goat anti-human Fc and donkey anti-goat 680 (A), and mouse anti-MUC5B antibody detected with donkey anti-mouse 800 (B). The double-stained image (C) was captured using a LI-COR odyssey CxL scanner. Asterisks mark the migration of major and minor Siglec-8-Fc labeled bands, all of which co-migrated with anti-MUC5B.

Discussion

Siglec-8 sialoglycan ligands engage Siglec-8 on the surface of eosinophils and mast cells to regulate allergic inflammation. Our prior studies targeting human airway revealed that a single major 1 MDa sialoglycoprotein ligand for Siglec-8 was produced in airway submucosal glands and secreted via their ducts onto the mucus of the airway lumen (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2021). These data, along with glycosidase susceptibility, support the conclusion that human airway Siglec-8 ligand is a minor isoform of the single carrier protein DMBT1 that is specifically decorated with terminally sialylated keratan sulfate chains. This is consistent with the specificity of Siglec-8 for the terminal structure Neu5Acα2-3[6-SO4]Galβ1-4[6-SO4]GlcNAc (Propster et al. 2016), The current report extends the exploration of Siglec-8 ligands to human esophagus, another tissue susceptible to eosinophil-mediated disease (Furuta and Katzka 2015). The findings are both highly consistent with the airway findings yet surprisingly distinct.

As in airways, Siglec-8 ligand in esophagus is synthesized in submucosal glands and is dense in ducts extending from those glands. This implies that, as in airway, the ligand is secreted onto the mucus of the esophageal lumen. The discovery of Siglec-8 ligand on esophageal lumen mucus from live subjects is consistent with this hypothesis. Analysis of Siglec-8 ligand extracted from the esophagus reveal a single high molecular weight protein carrier as in airway, and susceptibility of Siglec-8-Fc binding to treatment with sialidase and keratanase are consistent with the esophageal Siglec-8 ligand carrying the same target terminal sialoglycan as in airway, Neu5Acα2-3[6-SO4]Galβ1-4[6-SO4]GlcNAc. That is where the similarities end.

Unlike in airway, where a minor isoform of DMBT1 carries nearly all of the Siglec-8 ligand structure, in esophagus it is a minor isoform of MUC5B. Extracts of multiple postmortem human esophagi have the same major single Siglec-8 ligand migrating well above 2 MDa that was identified by proteomic mass spectrometry as MUC5B and comigrates with MUC5B immunoblotting upon gel electrophoresis. This finding is especially surprising since MUC5B is highly abundant in human airways yet is not a major carrier of Siglec-8 ligands. Our conclusion is that different human tissues (airway, esophagus) each post-translationally decorate primarily a single protein with Siglec-8 binding sialylated keratan sulfate chains, but that protein varies between tissues (Table 1). Our prior studies revealed that airway MUC5B carries the majority of Siglec-9 ligand but not Siglec-8 ligand (Jia et al. 2015). We view the findings in aggregate to indicate that certain carrier proteins act as a canvas on which biosynthetic enzymes in the Golgi apparatus coordinate to attach Siglec binding sialoglycans. This is further supported by data from the human brain (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2022), in which Siglec-8 ligands are sialylated keratan sulfate chains on a minor isoform of yet another single carrier protein, RPTPζ.

Table 1.

Siglec-8 ligands in human tissues.

| Tissue | Protein carrier | Molecular Wt (kDa) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airway submucosal glands & secreted mucins | DMBT1 | 1000 | (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2021) |

| Cerebral cortex | RPTPζ | 1000 | (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2022) |

| Esophagus submucosal glands | MUC5B | 5000 | this paper |

| Esophagus luminal secretions | MUC5B | 1000 | this paper |

The biochemical basis for carrier protein selectivity is, as yet, unclear. One can posit that when carrier proteins and the appropriate glycosyltransferases are in the same intracellular compartment, presumably within the Golgi apparatus, biosynthesis of Siglec-8 sialoglycan ligands proceeds. Comparative gene expression data for human brain, airways, and esophagus do not completely resolve Siglec-8 ligand expression specificity in the three tissues studied (Supplementary Fig. 2). Terminal transferases ST3GAL4 and CHST1 are well expressed across the tissues. DMBT1 and MUC5B are most highly expressed in airways. PTPRZ1 (RPTPζ) is most highly expressed in brain, but is well expressed in the other tissues. Whether the tissue specificity of carrier protein selection for biosynthesis of Siglec-8 ligands is based on coordinated gene expression at the single cell level, distribution of carriers and transferases within the Golgi apparatus, or carrier competition for transferases has yet to be determined.

It was interesting to note that DMBT1S8L and RPTPζS8L are both 1 MDa in tissues and secreted forms. On the esophageal mucus recovered from living subjects, most of the MUC5BS8L was also 1 MDa, although the parent ligand from esophageal submucosal glands and ducts appeared to be ~4 MDa. It is unknown whether the smaller MUC5BS8L in esophageal secretions represents a directed proteolytic processing to the smaller size. The limited volume of esophageal secretions available from the EST procedure precluded further exploration.

In addition to tissue-to-tissue variation in Siglec-8 ligand expression we found cell-to-cell variation at the single cell level. It was remarkable that esophageal submucosal cells adjacent to one another in a single acinus that both expressed ample MUC5B either robustly expressed Siglec-8 ligand or expressed none at all. We conclude that expression of a single glycosyltransferase (or suite of glycosyltransferases) or carbohydrate sulfotransferase(s) is expressed to drive Siglec ligand biosynthesis. This level of control may be a mechanism that controls Siglec ligand expression cell-to-cell and in a single cell in response to inflammatory signaling. The latter scenario would explain our finding of increased Siglec ligand expression in human diseases (Jia et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2021; Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2022). Understanding the gene expression and biosynthetic determinants underlying Siglec ligand expression may help us better understand this primarily immune inhibitory mechanism.

Materials and methods

Human esophagi and esophageal mucins

Postmortem human esophagi from 3 men and 5 women with no esophageal disease aged 41–65 years were acquired from the National Disease Research Interchange (Supplementary Table 1). A 5–10 cm portion of distal esophagus from each donor was dissected within hours of death, placed on ice in RPMI media with antibiotics (100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin), and shipped to the investigators within 24 h. Upon receipt, the esophagi were dissected on ice. Some portions were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C in advance of biochemical extraction. Others portions were fixed in 4% neutralized paraformaldehyde at ambient temperature for ≥24 h, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm and captured on glass slides for histochemical studies. When present, the gastroesophageal junction was captured separately.

Esophageal mucus from 3 live subjects with EoE who performed the EST was collected for a separate study (Ackerman et al. 2019). The Enterotest string device (HDC Corporation, Milpitas, CA) was used to capture surface material, including luminal secretions, inflammatory and epithelial cells from the esophagus. The weighted gelatin capsule containing a woven nylon string was swallowed and the proximal end taped to the subject’s cheek. One hour after swallowing the capsule, the string was removed, the esophageal segment identified, harvested, and placed in elution buffer, and the eluate was aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C for analyses. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Illinois at Chicago and is listed at clinicaltrials.gov as protocol NCT02008903.

Siglec-8 ligand histochemical detection

Siglec-8 ligands were detected on esophageal tissue sections by overlay with Siglec-8-Fc, an expressed and purified chimeric protein consisting of the entire Siglec-8 extracellular domain in frame with human IgG Fc domain as described (Jia et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2017).

Protocol 1: Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, then heated in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 9, containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for antigen retrieval. Slides were then blocked at ambient temperature with 30 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 (PBSTr) for 30 min, then with Bloxall Enzyme Blocker (Vector Laboratories) for 10 min, and then human Fc blocker (Innovex) for 30 min before washing with PBSTr. Siglec-8-Fc was precomplexed at a 2:1 ratio with goat anti-human IgG, Fc specific (MilliporeSigma I2136) in PBSTr containing 10 mg/mL BSA for ≥30 min. Blocked slides were overlaid with precomplexed Siglec-8-Fc (15 μg/mL) then incubated at 4 °C for >12 h. Slides were washed with PBSTr, incubated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch 305-035-003) at 4 °C for >12 h, washed, and signal developed using diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories).

Protocol 2: The method of Protocol 1 was followed except Siglec-8-Fc was precomplexed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG, Fc specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 109-055-008) and binding was detected using Vector Red alkaline phosphatase substrate (Vector Laboratories SK-51000) after washing the slide with 100 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 8.3.

As indicated, slides were pretreated with PBS (experimental) or 100 mU/ml of Vibrio cholerae sialidase (Moustafa et al. 2004) in PBS (negative control) at 37 °C for ≥2 h prior to Siglec-8-Fc. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to compare histological hallmarks or with Alcian Blue (Vector Laboratories H-3501) to detect glycosaminoglycans and mucins. Stained slides were dehydrated, mounted in Krystalon (MilliporeSigma) and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 90i or Nikon N-IE microscope (Nikon Instruments).

MUC5B/Siglec-8 ligand dual fluorescence histology

Tissue sections were deparaffinized, blocked and washed as above then overlaid with PBSTr/10 mg/mL BSA containing rabbit anti-MUC5B antibody (Sigma HPA008246, 1:200 dilution) and Siglec-8-Fc precomplexed with unconjugated goat anti-human Fc specific antibody (MilliporeSigma I2136) as described above. After incubation for >12 h at 4 °C the slides were washed and overlaid with a combination of AlexaFluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Invitrogen A32790) and AlexaFluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-goat (Invitrogen A32754) antibodies for 2 h at ambient temperature. Slides were washed, nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) then slides were processed and imaged as above.

Tissue extraction and Siglec ligand purification

Previously frozen esophageal tissues were thawed on ice. As indicated, some tissue samples were blunt dissected to separate the luminal layers (epithelium, mucosa, submucosa) from muscle layers. Tissues were weighed, transferred to a mortar, frozen by addition of liquid nitrogen, then pulverized with a pestle to 1–2 mm particles. These were suspended in cold extraction buffer (6 M guanidinium hydrochloride (GuHCl), 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM sodium phosphate, 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and protease inhibitor (Sigma P8340, diluted 1/100), pH 6.5) at a volume of 1 mL per 100 mg tissue wet weight. The slurry was sealed in a plastic tube and shaken at 4 °C for 24 h. The resulting crude extract was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min to remove insoluble components. As indicated, the pellet was re-extracted to determine the initial extraction efficiency.

Large glycoproteins in the GuHCl extracts were purified by stepwise cold ethanol precipitation. Ethanol chilled to −20 °C was added to extracts to 35% (v/v), vigorously mixed for 15 s and incubated at −20 °C for 6–16 h. Samples were then centrifuged at 30,000 × g, 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was recovered, additional cold ethanol added to bring the final concentration to 70% (v/v) and precipitation repeated. To that cleared supernatant, additional cold ethanol was added to bring the final concentration to 90% (v/v) and precipitation repeated. The resulting pellets were treated with 4 M GuHCl in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7 and incubated with shaking at 4 °C for >12 h.

For size exclusion chromatography, samples were dialyzed against 4 M GuHCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7 in 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff dialysis filters (Spectra) to remove residual ethanol and small proteins. The samples were then centrifuged (30,000 × g, 10 min), the supernatant collected, and 5-ml aliquots loaded into an AKTA fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system fitted with a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-500 HR size exclusion chromatography column (Cytiva). The column was eluted with 4 M GuHCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7 at 1 mL per min. Aliquots of fractions were dialyzed against Urea Buffer (1 M urea, 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7), electrophoresed, and blotted, after which Siglec-8 ligands were detected by lectin overlay (see below). Fractions containing Siglec-8 ligand were combined, concentrated and buffer exchanged to Urea Buffer using 100 kDa cutoff filters.

The final step in purification was Siglec-8 affinity chromatography. To the concentrated combined size exclusion fractions in Urea Buffer was added PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) at 1:4 (v/v). The mixture was pre-cleared by incubating with 200 μL of Protein G magnetic beads (Cytiva) loaded with 250 μg of human IgG-Fc (Millipore) at ambient temperature for 1 h. The beads were magnetically captured, the cleared supernatant recovered and added to 200 μL of Protein G magnetic beads preloaded with 250 μg of Siglec-8-Fc. The suspension was mixed by rotation for >12 h at 4 °C after which the beads were magnetically captured, washed with Urea Buffer/PBST mixture (4:1) and eluted with a step-wise gradient of NaCl (25 mM to 1 M). Siglec-8 ligand in each fraction was determined by gel electrophoresis, blotting and Siglec-8-Fc overlay as detailed below. Active fractions were combined and dialyzed against Urea Buffer.

Siglec-8 ligand resolution and detection via composite gel electrophoresis

Large proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel electrophoresis on custom-cast composite agarose-polyacrylamide gels (Johansson and Hansson 2012). Agarose (1.5%–2% final), acrylamide (1%–1.5% final) and glycerol (7%–12%) were dissolved in 0.4 M Tris buffer pH 8 containing 4 M urea at 60 °C. Tetramethylethylenediamine and ammonium persulfate were added to induce polymerization and gels were cast at 60 °C using a mini gel system (Invitrogen). Running buffer contained 0.1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA in 0.2 M Tris-borate buffer pH 8. Since GuHCl is incompatible with this system, aliquots of samples containing GuHCl were dialyzed against 1–2 M urea in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4. Samples were mixed with NuPAGE loading buffer (Thermo) containing 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and heated at 95 °C for 10 min before loading and resolving for 2.5 h at 100 V. Resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) or nitrocellulose membranes for 7 min at 20 V using the iBlot2 system (Invitrogen). Ligand migration was compared to that of custom pre-stained molecular weight marker (950 kDa, 1.9 MDa) consisting of covalently crosslinked human IgM (Gonzalez-Gil et al. 2021). Alternatively, dot blots were used to track elution of Siglec-8 ligand from size exclusion chromatography. Aliquots of fractions were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a BioRad DotBlot system.

Siglec-8 ligand was detected on blots via lectin overlay. Siglec-8-Fc was pre-complexed at a 2:1 ratio with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody (Fc specific, MilliporeSigma A0170) for 30 min in PBST. Blots were blocked for 30 min at ambient temperature by incubating in 5% w/v non-fat dry milk in PBST then overlaid with precomplexed Siglec-8-Fc in PBST at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL based on Siglec-8-Fc. After incubation for >12 h at 4 °C, blots were washed with PBST and bound antibody detected using chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo 34577) detected using a Syngene PXi image analysis system.

Human MUC5B immunoblotting was performed by overlaying blots with polyclonal rabbit anti-human MUC5B (MilliporeSigma HPA008246) or mouse monoclonal anti-human MUC5B (Novus NBP2-50522 or Abcam ab105460) in PBST as indicated. After incubation for >12 h at 4 °C blots were washed, incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies and imaged.

For fluorescent double-labeling, Siglec-8-Fc was precomplexed with unconjugated goat anti-human IgG Fc-specific secondary antibody and IRDye 680 donkey anti-goat tertiary antibody (LI-COR 926-68074) at a ratio of 4:2:1. Blots were blocked as above and incubated with Siglec-8-Fc complex (1 μg/mL based on Siglec-8-Fc) and mouse monoclonal anti-MUC5B antibody. After incubation for >12 h at 4 °C blots were washed and anti-MUC5B antibody detected with IRDye donkey anti-mouse antibody (LI-COR 926-32212). Double-stained images were captured using a LI-COR Odyssey CxL scanner.

Proteomic mass spectrometry

Siglec-8 ligand purified by sequential ethanol precipitation, size exclusion chromatography, and affinity chromatography was reduced with 10 mM DTT for 1 h at 37 °C then alkylated with 30 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 30 min at ambient temperature. Samples were dialyzed against 2 M urea, 50 mM Tris, 10 mM CaCl2 pH 8.0 at 4 °C, then 60 ng of LysC were added to 200 μL of purified material and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 6 h. Sterile water was added to the samples to dilute the urea to 1 M, 60 ng of trypsin were added, and the reaction incubated at ambient temperature for >12 h. Highly glycosylated and undigested peptides were removed using a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff Amicon filter and the filtrate collected and stored at −20 °C. Trifluoracetic acid was added to the peptides (0.05%) and the peptides purified on a C18 spin column (PierceTM). Peptides were eluted with 80% acetonitrile, evaporated and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid.

Proteomic analyses were performed on a TIMSTOF Flex mass analyzer (Bruker) coupled to an EasyNLC 1200 system (Proxeon) by a 15 cm × 75 μm PepSep column with 1.5 μm Reprosil particles with an inline 3 cm × 75 μm PepMap Trap (Thermo Fisher). Data was acquired using a data dependent method where ions were selected for fragmentation with a 1/k0 value between 0.6 and 1.6 and a m/z 400–1,700. Ions meeting these previously described parameters were fragmented in order of their relative signal intensity. A custom isolation polygon was utilized to exclude +1 ions from fragmentation. Due to the low intensity of these samples the “high sensitivity” mode was employed with a compensation voltage of 40 V. The chromatography gradient ramped from 8% buffer B (80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid) to 35% B in 45 min with a flow rate of 350 nL/min prior to a rapid increase to 100% B at 500 nL/min by 60 min. Data were processing in FragPipe 18 (Kong et al. 2017).

Treatment with glycosidases

Samples were dialyzed in PBS using a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff MINI dialysis device (Invitrogen). All enzymatic reactions were completed with glycosidase at a 50 mU/mL final concentration, in sterile buffers at 37 °C for ≥4 h. Neuraminidase from Arthrobacter (Agilent GK80040), or neuraminidase S (Agilent GK80021), or neuraminidase from V. cholerae (in-house) was added to samples in PBS. PNGase F (NEB 0704) was added to samples supplemented with GlycoBuffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5) with or without NP-40 and Denaturing Buffer (0.5% SDS, 40 mM DTT). Chondroitinase ABC from Proteus vulgaris (Sigma) was added to samples in 50 mM sodium acetate pH 8. Keratanase I from Pseudomonas sp. (AMSBIO) was added to samples in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 7. Keratanase II from Bacillus sp. (Steward et al. 2015) was added to samples in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 7. Keratanase I acts on low sulfated keratan sulfate and keratanase II on high sulfated keratan sulfate. Addition of 1:40 of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma P8340) in the keratanase I reaction was required to prevent MUC5B degradation.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

T August Li, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Anabel Gonzalez-Gil, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Abduselam K Awol, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Steven J Ackerman, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, 900 S. Ashland Avenue, Chicago, IL 60607, United States.

Benjamin C Orsburn, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Ronald L Schnaar, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Author contributions

T. August Li (Conceptualization [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Anabel Gonzalez-Gil (Conceptualization [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Abduselam Awol (Investigation [equal]), Steven Ackerman (Conceptualization [equal], Resources [equal]), Benjamin Orsburn (Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), and Ronald Schnaar (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—original draft [equal])

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI136443 (R.L.S.), HL141952 (A.G.G.), AG064908 (B.C.O.) and GM135083 (T.A.L.), Food and Drug Administration grant FD004086 (S.J.A.), and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (R.L.S.). We gratefully acknowledge the use of tissues procured by the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI) with support from National Institutes of Health grant U42OD11158.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Data availability

Data are included in the manuscript or Supplement.

References

- Ackerman SJ, Kagalwalla AF, Hirano I, Gonsalves N, Katcher PM, Gupta S, Wechsler JB, Grozdanovic M, Pan Z, Masterson JC, et al. One-hour Esophageal string test: a nonendoscopic minimally invasive test that accurately detects disease activity in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019:114(10):1614–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JR, El-Zimaity H, Riddell RH. Esophagus. In: Mills SE, editors. Histology for pathologists. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020. pp. 570–601 [Google Scholar]

- Furuta GT, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2015:373(17):1640–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli SJ, Gaudenzio N, Tsai M. Mast cells in inflammation and disease: recent progress and ongoing concerns. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020:38(1):49–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006:64(3):313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gil A, Li TA, Porell RN, Fernandes SM, Tarbox HE, Lee HS, Aoki K, Tiemeyer M, Kim J, Schnaar RL. Isolation, identification, and characterization of the human airway ligand for the eosinophil and mast cell immunoinhibitory receptor Siglec-8. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021:147(4):1442–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gil A, Porell RN, Fernandes SM, Maenpaa E, Li TA, Li T, Wong PC, Aoki K, Tiemeyer M, Yu ZJ, et al. Human brain sialoglycan ligand for CD33, a microglial inhibitory Siglec implicated in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 2022:298(6):101960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gil A, Li TA, Kim J, Schnaar RL. Human sialoglycan ligands for immune inhibitory Siglecs. Mol Asp Med. 2023:90:101110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Yu H, Fernandes SM, Wei Y, Gonzalez-Gil A, Motari MG, Vajn K, Stevens WW, Peters AT, Bochner BS, et al. Expression of ligands for Siglec-8 and Siglec-9 in human airways and airway cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015:135(3):799–810.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson ME, Hansson GC. Analysis of assembly of secreted mucins. Methods Mol Biol. 2012:842:109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julenius K, Molgaard A, Gupta R, Brunak S. Prediction, conservation analysis, and structural characterization of mammalian mucin-type O-glycosylation sites. Glycobiology. 2005:15(2):153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong AT, Leprevost FV, Avtonomov DM, Mellacheruvu D, Nesvizhskii AI. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat Methods. 2017:14(5):513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Gonzalez-Gil A, Drake V, Li TA, Schnaar RL, Kim J. Induction of the endogenous sialoglycan ligand for eosinophil death receptor Siglec-8 in chronic rhinosinusitis with hyperplastic nasal polyposis. Glycobiology. 2021:31(8):1026–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JD, Orlando RC. Esophageal submucosal glands: structure and function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999:94(10):2818–2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellacheruvu D, Wright Z, Couzens AL, Lambert JP, St-Denis NA, Li T, Miteva YV, Hauri S, Sardiu ME, Low TY, et al. The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat Methods. 2013:10(8):730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa I, Connaris H, Taylor M, Zaitsev V, Wilson JC, Kiefel MJ, von Itzstein M, Taylor G. Sialic acid recognition by vibrio cholerae neuraminidase. J Biol Chem. 2004:279(39):40819–40826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan J, Youngblood BA, Schleimer RP, Bochner BS. Siglecs as potential targets of therapy in human mast cell- and/or eosinophil-associated diseases. Semin Immunol. 2023:69:101799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propster JM, Yang F, Rabbani S, Ernst B, Allain FH, Schubert M. Structural basis for sulfation-dependent self-glycan recognition by the human immune-inhibitory receptor Siglec-8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016:113(29):E4170–E4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarosiek J, McCallum RW. Mechanisms of oesophageal mucosal defence. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000:14(5):701–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward M, Berezovskaya Y, Zhou H, Shediac R, Sun C, Miller N, Rendle PM. Recombinant, truncated B. Circulans keratanase-II: description and characterisation of a novel enzyme for use in measuring urinary keratan sulphate levels via LC-MS/MS in Morquio a syndrome. Clin Biochem. 2015:48(12):796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ME, Drickamer K, Imberty A, van Kooyk Y, Schnaar RL, Etzler ME, Varki A. Discovery and classification of glycan-binding proteins. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Stanley P, Hart GW, Aebi M, Mohnen D, Kinoshita T, Packer NH, et al., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2022. pp. 375–386 [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler ME, Munitz A, Ackerman SJ, Drake MG, Jackson DJ, Wardlaw AJ, Dougan SK, Berdnikovs S, Schleich F, Matucci A, et al. Eosinophils in health and disease: a state-of-the-art review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021:96(10):2694–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngblood BA, Leung J, Falahati R, Williams J, Schanin J, Brock EC, Singh B, Chang AT, O’Sullivan J, Schleimer RP, et al. Discovery, function, and therapeutic targeting of Siglec-8. Cells. 2020:10(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Gonzalez-Gil A, Wei Y, Fernandes SM, Porell RN, Vajn K, Paulson JC, Nycholat CM, Schnaar RL. Siglec-8 and Siglec-9 binding specificities and endogenous airway ligand distributions and properties. Glycobiology. 2017:27(7):657–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Shoda T, Aceves SS, Arva NC, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, et al. Mast cell-pain connection in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2022:77(6):1895–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are included in the manuscript or Supplement.