Abstract

Background

Hypoalbuminemia is common in heart failure (HF) patients; however, there are no data regarding the possible long-term prognostic role of serum albumin (SA) in the younger population with chronic HF without malnutrition. The aim of this study was to examine the long-term prognostic role of SA levels in predicting major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in middle-aged outpatients with chronic HF.

Methods

In the present retrospective analysis, 378 subjects with HF were enrolled. MACE (non-fatal ischemic stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, cardiac revascularization or coronary bypass surgery, and cardiovascular death), total mortality, and HF hospitalizations (hHF) occurrence were evaluated during a median follow-up of 6.1 years.

Results

In all population, 152 patients had a SA value < 3.5 g/dL and 226 had a SA value ≥ 3.5 g/dL. In patients with SA ≥ 3.5 g/dL, the observed MACE were 2.1 events/100 patient-year; while in the group with a worse SA levels, there were 7.0 events/100 patient-year (p < 0.001). The multivariate analysis model confirmed that low levels of SA increase the risk of MACE by a factor of 3.1. In addition, the presence of ischemic heart disease, serum uric acid levels > 6.0 mg/dL, chronic kidney disease, and a 10-year age rise, increased the risk of MACE in study participants. Finally, patients with SA < 3.5 g/dl had a higher incidence of hHF (p < 0.001) and total mortality (p < 0.001) than patients with SA ≥ 3.5 g/dl.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic HF that exhibits low SA levels show a higher risk of MACE, hHF and total mortality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11739-024-03612-9.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, Albumin, MACE, Comorbidities

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a growing health problem, prevalence ranges from about 1.5 to 4% in developed countries [1]. Despite important pharmacological innovations in recent years, the prognosis of HF patients remains poor with a mortality rate of about 50% during the five-year follow-up [1]. Another critical issue in HF is represented by comorbidities that show a crucial role on diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Among non-cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities malnutrition and frailty, often under-diagnosed and undertreated, have particular relevance affecting clinical prognosis especially in elderly [2–4].

In this setting, hypoalbuminemia represents a marker of malnutrition and frailty, but also of comorbidities and inflammatory state burden [5, 6]. Hypoalbuminemia is a common condition in HF, with a prevalence up to 89% and is associated with an increased risk of HF onset and progression, as well as CV morbidity and mortality [6–15]. These findings are most evident in acute HF also in nonagenarian patients, in which severe hypoalbuminemia is a potential predictor of poor in-hospital outcome [16–18]. In addition, hypoalbuminemia was found to be a significant independent predictor of mortality in both acute and chronic HF; however, the follow-up in these studies rarely exceeded one year and study populations are mainly represented by elderly with acute HF [17–27].

The prognostic role of albumin is also confirmed in chronic HF patients with secondary mitral insufficiency [28]. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that changes in SA levels over time are associated with different prognosis in patients with chronic HF. In fact, while a decrease in SA levels over time is associated with a worse prognosis, an increase is associated with a better prognosis; this is probably because SA levels reflect the general condition of chronic HF patients [29]. Data are also confirmed by a recent meta-analysis, where hypoalbuminemia worsens the prognosis in both inpatients and outpatients [30].

In addition, the prognostic value of SA is particularly evident in high-intensity care populations such as HF patients in cardiogenic shock or patients in intensive care; indeed, in this category of patients, in addition to reduced SA levels, a reduction in SA levels during hospitalization worsens the prognosis [31, 32]. To our knowledge, the prognostic significance of hypoalbuminemia has not yet been fully evaluated in the HF clinical setting. According with this, there are no data regarding the possible long-term prognostic role of albumin in the younger population with chronic HF, especially in patients without malnutrition. The purpose of the present study was to examine the long-term prognostic role of serum albumin (SA) levels in predicting major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in middle-aged outpatients with chronic HF, after adjustment for known confounding factors and especially for inflammation, nutritional status, liver and kidney function. Total mortality and HF hospitalizations (hHF) during follow-up were also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Study population

In this retrospective analysis, 378 subjects with HF were enrolled, between October 2012 and June 2022, at the Geriatric Department of “Magna Graecia” University-Hospital of Catanzaro, Italy. The study included outpatients suffering from chronic HF from the CATAnzaro Metabolic Risk factors (CATAMERI) Study, an ongoing longitudinal observational study assessing cardio-metabolic risk in individuals, recruited at the University Hospital of Catanzaro. They were recruited according to the indications of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF [1]. The eligibility criteria included: written informed consent; age > 18 years; NYHA classes II–III. The exclusion criteria included: acute HF in the previous 6 months, chronic HF with NYHA class IV, respiratory failure, severe renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtrate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73m2); nephrotic syndrome, macroalbuminuria, severe hepatic impairment (Child–Pugh Class C); pregnancy or breastfeeding, malnutrition evaluated as Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) < 17 pts and cachexia [33]. A careful medical history was obtained in all subjects. A complete CV physical examination was performed, and both body weight and body mass index (BMI) were also measured. Blood samples were collected for the determination of several laboratory parameters.

The study was approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committees of University “Magna Graecia” of Catanzaro (code protocol number 2012.63). All patients signed informed consent and the study procedures were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory parameters

All laboratory measurements were performed on peripheral blood samples after at least 12 h of fasting. SA was measured with a colorimetric spectrophotometric method (Bromocresol green). Glycaemia was determined by the glucose oxidase method (glucose analyzer, BeckmanCoulter, Milan) and the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index was used for the determination of Insulin resistance [34]. Enzymatic methods (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) were used for determination of blood levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) by pyridoxal phosphate activated (liquid reagent), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) were evaluated by standardized method (COBAS Integra 800-Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Creatinine was measured using the Jaffé method. The CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) equation was used for the estimation of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [35]. Serum uric acid (UA) levels were assessed using URICASE/POD method (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). The immuno-turbidimetric method automated system (Cardio Phase hs-CRP, Milan, Italy) was used to assess the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP).

Cardiovascular endpoints

MACE were identified as study endpoints (non-fatal ischemic stroke, non-fatal coronary events, and CV death). Total mortality and HF hospitalizations (hHF) during follow-up were also evaluated. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction was made according to the universal definition [36]. CV death included progressive HF and death related to surgical or percutaneous revascularization procedures, and sudden death. The diagnosis of ischemic stroke was determined by clinical manifestations and radiological findings [37]. Data on MACE were collected during the follow-up. A standardized form was filled out by the examiners when an event occurred. Details of each event were recorded, as well as death certificates, hospital discharge letter or copy of hospitalization medical record, and other clinical documentation obtained from patients or their relatives.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR), and number and percentage for categorical variables, when appropriate. Student’s t-test was performed for unpaired data for continuous variables, Mann–Whitney’s test for unpaired data for non-continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. According to the clinical cut-off of SA (3.5 g/dL), the overall population was divided into two groups; of interest, this value has been already associated with increased thrombotic risk [38, 39]. Simple linear regression and multivariate stepwise linear regression models were constructed to evaluate independent predictors of hypoalbuminemia, both as a continuous and dichotomous variable. Variables that correlated significantly with MACE were entered into a multivariate stepwise linear regression model to evaluate independent predictors of SA levels. The accuracy of the SA value as a predictor of MACE, both as a categorical and continuous variable, was evaluated by processing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the curve (AUC) described the magnitude to which the SA value was associated with the onset of events. The number of events per 100 patient-year was used to calculate the incidence of events. The onset of MACE was not assessed at the same time, because the follow-up was not uniform for all patients, so a regression analysis based on the Cox proportional model was used, correcting the analysis for possible covariates associated with the finding of MACE. In particular, a univariate Cox regression model was performed on the incidence of MACE; subsequently, the variables that significantly correlated with the appearance of MACE were included in a multivariate Cox regression model to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) for the independent predictors associated with the incidence of MACE. Analysis was corrected for pharmacological treatments. The differences were considered statistically significant for p value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS 20.0 statistical program for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study population

378 patients were enrolled with average age of 67.1 ± 11.2 years, 107 were females and 271 males, 220 had HF with mildly reduced (HFmrEF) and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and 158 were affected by HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In all study population, 152 patients had a SA value < 3.5 g/dL, and none of these received albumin supplementation during follow-up, while the remaining 226 had a SA value ≥ 3.5 g/dL (Supplementary Fig. 1). The median follow-up was 6.1 (3.1–9.9) years.

Table 1 shows the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the entire study population, stratified by the clinical cut-off of SA (3.5 g/dL). Statistically significant differences between the two groups were observed for prevalence of Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and dyslipidemia significantly higher in patients with lower SA levels. There was no difference between the two groups for intake of antihypertensive drugs, oral antidiabetics, insulin, oral anticoagulants, anti-aggregants, statins, beta-blockers, loop diuretics, SGLT2-inhibitors, sacubitril–valsartan, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Regarding clinical, hemodynamic, and laboratory parameters, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups, except, obviously, for SA levels, but also for hs-CRP and microalbuminuria, significantly higher in patients with SA < 3.5 g/dL (Table 1). In addition, the two groups differed in MNA with worse results in lower albumin levels group.

Table 1.

Clinical, epidemiological, laboratory, echocardiographic parameters, and pharmacotherapy of study population at baseline according to clinical cut-off of serum albumin

| All population (n 378) | Albumin < 3.5 g/dl (n. 152) | Albumin ≥ 3.5 g/dl (n. 226) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67.0 ± 11.2 | 67 ± 10.9 | 66.9 ± 11.4 | 0.551ǂ |

| Female gender, n (%) | 107 (28.3) | 46 (30.2) | 61 (26.9) | 0.488* |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 31.0 ± 4.8 | 30.8 ± 4.6 | 31.1 ± 5.0 | 0.450ǂ |

| IHD, n (%) | 233 (61.6) | 95 (62.5) | 138 (61.0) | 0.778* |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 196 (51.9) | 72 (47.4) | 124 (54.9) | 0.152* |

| AF, n (%) | 76 (20.1) | 26 (17.1) | 50 (22.1) | 0.232* |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 145 (38.9) | 69 (45.4) | 76 (33.6) | 0.021* |

| SAS, n (%) | 119 (31.4) | 55 (36.1) | 64 (28.3) | 0.106* |

| CKD, n (%) | 95 (21.1) | 41 (26.9) | 54 (23.9) | 0.498* |

| COPD, n (%) | 81 (21.4) | 35 (23.0) | 46 (20.3) | 0.534* |

| NAFLD, n (%) | 42 (11.1) | 29 (19.0) | 13 (5.7) | < 0.001* |

| Obesity, n (%) | 92 (24.3) | 41(26.9) | 51(22.6) | 0.327* |

| T2DM, n (%) | 193 (51.0) | 78 (51.3) | 115 (50.1) | 0.934* |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 63 (16.6) | 22 (14.4) | 41 (18.1) | 0.348* |

| Smokers, n (%) | 134 (35.4) | 59 (38.8) | 75 (33.1) | 0.261* |

| MLHFQ, pt | 95.3 ± 11.2 | 95.23 ± 3.0 | 226 ± 3.1 | 0.619ǂ |

| MNA, pts | 22.9 ± 3.3 | 21.7 ± 2.9 | 23.8 ± 3.2 | < 0.001ǂ |

| SBP, mmHg | 123.0 ± 15.6 | 122.0 ± 15.9 | 124.0 ± 15.4 | 0.166ǂ |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.09 ± 9.7 | 73.9 ± 10.1 | 74.3 ± 9.4 | 0.704ǂ |

| HR, bfm | 68.9 ± 14.5 | 69.7 ± 15.5 | 68.42 ± 13.9 | 0.387ǂ |

| RR, afm | 18.9 ± 1.8 | 18.8 ± 1.9 | 18.9 ± 1.7 | 0.745ǂ |

| Hb, g/dl | 12.2 ± 1.6 | 12.1 ± 1.7 | 12.2 ± 1.5 | 0.546ǂ |

| Hct, % | 38.3 ± 5.4 | 37.9 ± 5.5 | 38.53 ± 5.3 | 0.304ǂ |

| Na, mmol/l | 140.7 ± 33.1 | 140.61 ± 3.0 | 140.7 ± 2.5 | 0.685ǂ |

| Mg, mg/dl | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.95 ± 0.2 | 1.93 ± 0.2 | 0.742ǂ |

| K, mmol/l | 4.4 ± 0.41 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.503ǂ |

| HOMA, pts | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.9 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 0.502ǂ |

| HbA1c, % | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 0.827ǂ |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 70.7 ± 18.9 | 68.6 ± 18.5 | 72.2 ± 19.0 | 0.071ǂ |

| Microalbuminuria, mg/l | 34.2 ± 14.2 | 41.4 ± 17.4 | 29.3 ± 8.6 | < 0.001ǂ |

| LDL, mg/dl | 63.36 ± 28.9 | 62.32 ± 27.2 | 64.06 ± 30.1 | 0.566ǂ |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 128.0 ± 46.1 | 124.5 ± 34.8 | 131.6 ± 52.3 | 0.147ǂ |

| AST, U/L | 21.4 ± 9.2 | 20.7 ± 7.9 | 21.9 ± 9.9 | 0.205ǂ |

| ALT, U/L | 20.8 ± 9.7 | 19.6 ± 6.9 | 21.5 ± 11.2 | 0.063ǂ |

| γ-GT, U/L | 36.0 ± 20.2 | 36.1 ± 18.4 | 35.9 ± 21.4 | 0.941ǂ |

| Albumin, mg/dl | 3.8 ± 0.46 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | < 0.001ǂ |

| NT-pro-BNP, pg/ml | 2283.3 ± 582.4 | 2320.8 ± 556.0 | 2258.1 ± 19.0 | 0.305ǂ |

| Uricemia, mg/dl | 5.9 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 0.173ǂ |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | < 0.001ǂ |

| LAVi, ml/m2 | 44.5 ± 11.5 | 44.5 ± 12.4 | 44.5 ± 10.9 | 0.990ǂ |

| LVEF, % | 43.0 ± 9.1 | 42.9 ± 9.3 | 43.1 ± 8.9 | 0.816ǂ |

| CI, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1909.1 ± 197.6 | 1897.6 ± 196.1 | 1916.7 ± 198.6 | 0.358ǂ |

| E/A | 0.80 ± 0.46 | 0.79 ± 0.47 | 0.81 ± 0.45 | 0.817ǂ |

| E/e’ | 15.4 ± 4.6 | 15.5 ± 4.6 | 15.3 ± 4.5 | 0.681ǂ |

| TAPSE, mm | 17.6 ± 3.8 | 17.4 ± 3.5 | 17.7 ± 4.0 | 0.369ǂ |

| s-PAP, mmHg | 42.3 ± 11.1 | 43.1 ± 10.1 | 41.7 ± 11.3 | 0.237ǂ |

| TAPSE/s-PAP, mm/mmHg | 0.45 ± 0.19 | 0.44 ± 0.18 | 0.46 ± 0.19 | 0.199ǂ |

| β-blockers, n (%) | 337 (89.1) | 134 (77.9) | 203 (89.8) | 0.609* |

| ACEi/ARBs, n (%) | 189 (50.0) | 73 (48.0) | 116 (51.3) | 0.529* |

| MRAs, n (%) | 156 (41.3) | 60 (39.4) | 96 (42.4) | 0.560* |

| ARNI, n (%) | 171 (45.2) | 72 (47.4) | 99 (43.8) | 0.494* |

| SGLT2i, n (%) | 158 (41.8) | 66 (43.4) | 92 (40.7) | 0.600* |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 297 (78.6) | 127 (83.5) | 170 (75.2) | 0.053* |

| OADs, n (%) | 193 (50.9) | 78 (51.3) | 115 (50.9) | 0.934* |

*performed by chi-square test

ǂ performed by t-test for unpaired data

BMI body mass index, IHD ischemic heart disease, AF atrial fibrillation, SAS sleep apnea syndrome, CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, MLHFQ minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire, MNA mini-nutritional assessment, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate, Hb hemoglobin, Hct hematocrit, Na Sodium, Mg Magnesium, K Potassium, HOMA homeostatic HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, e-GFR estimate glomerular filtration rate, LDL low-density lipoproteins, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GT gamma-glutamyltransferase, NT-pro-BNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, LAVi left atrial volume index, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, CI cardiac index, RVOTp right ventricular outflow tract proximal, E/A ratio between wave E (the wave of rapid filling in early diastole) and wave A (the wave of atrial contraction), E/e’ between wave E and wave e′ (reliable estimate of changes in end-diastolic blood pressure), TAPSE tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, s-PAP systolic pulmonary arterial pressure, ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARBs Angiotensin II receptor blockers, MRAs mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, ARNI angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, OADs oral antidiabetic drugs

Variables associated with hypoalbuminemia in the study population

From the first simple linear regression model, considering albumin as a continuous variable, the following variables correlated significantly: hs-CRP (r = −0.398; p < 0.001), MNA score < 23 pts (r = 0.189; p < 0.001), NAFLD (r = −0.206; p < 0.001) and microalbuminuria (r = −0.109; p = 0.015). At multivariate stepwise linear regression, the variable that was most associated with serum albumin levels were hs-CRP serum levels and the whole model correlated for 35.3% of albumin levels. Data were also confirmed by the second simple linear regression model; in fact, considering albumin as a dichotomous variable, the following variables correlated significantly: hs-CRP (r-0.513; p < 0.001), MNA score < 23 pts (r = 0.213; p < 0.001), NAFLD (r = −0.114; p = 0.004) and microalbuminuria (r = −0.039; p = 0.004). At multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis, hs-CRP levels were the main variable that was most associated, and the whole model correlated for 43.6% of SA levels (supplementary Tables 1–2).

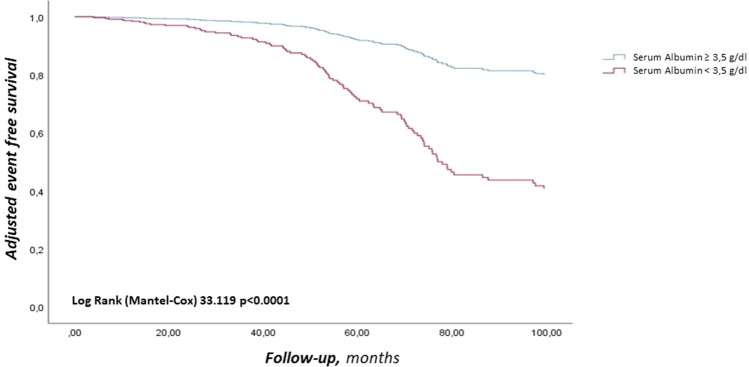

Major adverse cardiovascular events and hospitalization for Heart Failure

In the whole population a total of 94 (24.9%) MACE were observed (3.8 events/100 patient-year) (Fig. 1). In particular, 45 (11.9%) were non-fatal coronary events (1.8 events/100 patient-year), 25 (6.6%) non-fatal stroke events (1.0 events/100 patient-year) and 24 (6.3%) CV death (0.9 events/100 patient-year). In patients with SA < 3.5 g/dL, MACE observed were 60 (6.8 events/100 patient-year); while in the group with SA ≥ 3.5 g/dL were 34 (2.1 events/100 patient-year) (p < 0.001) (Log-Rank test p < 0.001, Fig. 1). Non-fatal coronary events were 27 (17.8%) in the first group (3.1 events/100 patient-year) and 18 (7.9%) in the second group (1.1 events/100 patient-year) (p = 0.003); furthermore, non-fatal stroke events were 17 (11.2%) in the first group (1.9 events/100 patient-year) and 8 (3.5%) in the second group (0.5 events/100 patient-year) (p = 0.003). CV death events were 16 (10.5%) in the first group (1.8 events/100 patient-year) and 8 (3.5%) in the second group (0.5 events/100 patient-year) (p = 0.006) (Table 2). In addition to CV death, during the follow-up, 46 (12.2%) deaths due to non-CV causes occurred (1.9 events/100 patient-year), of which 30 (19.7%) in patients with SA < 3.5 g/dL (3.4 events/100 patient-year) and 16 (7.0%) in patients with SA ≥ 3.5 (1.0 events/100 patient-year) (p < 0.001). To further evaluate the relationship between SA and MACE, we divided the population into increasing tertiles of SA, each tertile consisted of 126 patients. Specifically, we observed more MACE in the tertile with lower SA levels followed by the second and third tertiles, in detail: 52 MACE in the first tertile, 28 in the second tertile and 14 in the third tertile, confirming the association between reduced SA levels and MACE (p < 0.001). Regarding hHF during follow-up, there were 112 (29.6%) hospitalizations in the whole study population (4.6 events/100 patient-year), of which 68 (44.7%) in the group with SA < 3.5 g/dL (7.7 events/100 patient-year) and 44 (19.5%) in the group with SA ≥ 3.5 g/dL (2.8 events/100 patient-year) (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier on MACE, according to cut-off value of SA, Adjusted for: SA as dichotomous value, IHD, UA as dichotomous value, CKD, and Age as 10 years. MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, SA Serum albumin, IHD ischemic heart disease, UA uric acid, CKD chronic kidney disease

Table 2.

Cardiovascular events and hHF in the study population according to clinical cut-off of serum albumin

| All population (n. 378) | Albumin < 3.5 g/dl (n. 152) | Albumin ≥ 3.5 g/dl (n. 226) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n (%) | 94 (3.8) | 60 (6.8) | 34 (2.1) | < 0.001* |

| Nonfatal Stroke, n (%) | 25 (1.0) | 17 (1.9) | 8 (0.5) | 0.003* |

| NF Coronary events, n (%) | 45 (1.8) | 27 (3.1) | 18 (1.1) | 0.003* |

| CV mortality, n (%) | 24 (0.9) | 16 (1.8) | 8 (0.5) | 0.006* |

| Non CV Mortality, n (%) | 46 (1.9) | 30 (3.4) | 16 (1.0) | < 0.001* |

| Total mortality, n (%) | 70 (2.8) | 46 (5.2) | 24 (1.5) | < 0.001* |

| hHF, n (%) | 112 (4.6) | 68 (7.7) | 44 (2.8) | < 0.001* |

*performed by chi square test

Data described as number of patients (number of events per 100 patient-year)

hHF Heart failure hospitalizations, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, NF Non-fatal, CV cardiovascular

The accuracy of SA as a predictive value of the onset of MACE both as a continuous (Fig. 2A) and as dichotomous value (Fig. 2B) was evaluated by AUC. Figure 2A shows the ROC curve of SA as a continuous variable; notably, SA as a continuous variable has a greater discriminating power in predicting the development of MACE (AUC 0.708; standard error 0.030; 95% CI 0.650–0.766; p < 0.001), compared with SA as a dichotomous value (AUC 0.663; standard error 0.032; 95% CI 0.600–0.725; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A ROC curves on MACE, according to SA as continuous variable. AUC area under the curve, MACE major cardiovascular adverse events, ROC receiver operating characteristic, SA serum albumin. B ROC curves on MACE, according to SA as dichotomous variable. AUC area under the curve, MACE major cardiovascular adverse events, ROC receiver operating characteristic, SA serum albumin

Cox regression analysis

Cox linear regression analysis shows a statistically significant association between MACE and age (considering 10 years’ variation), CKD, Ischaemic heart disease (IHD), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and UA > 6 mg/dL (Table 3). The variables significantly associated with the onset of MACE in the Cox univariate analysis were included in a multivariate analysis model to define the independent predictors of clinical outcome (Table 4). Of interest, albumin levels < 3.5 g/dL were associated with 3.1-fold increase in the risk of MACE, the presence of IHD and circulating UA levels > 6.0 mg/dL explained an increased risk of MACE by 2.3- and 2.2-fold, respectively. The presence of CKD also doubles the risk of MACE. Finally, a 10-year increase in age results in a 33% higher risk of MACE.The text continues here.

Table 3.

Univariate Cox regression analysis on MACE

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, yes/no | 1.471 | 0.183–11.820 | 0.717 |

| Age, 10 years | 1.296 | 1.021–1.824 | 0.013 |

| IHD, yes/no | 2.241 | 1.940–5.343 | 0.046 |

| AF, yes/no | 2.164 | 0.753–6.218 | 0.152 |

| SAS, yes/no | 1.015 | 0.522–1.972 | 0.965 |

| CKD, yes/no | 3.449 | 1.559–7.629 | 0.002 |

| COPD, yes/no | 2.449 | 0.923–6.499 | 0.072 |

| NAFLD, yes/no | 1.619 | 0.693–3.783 | 0.265 |

| Obesity, yes/no | 1.346 | 0.653–2.777 | 0.421 |

| T2DM, yes/no | 1.019 | 0.474–2.193 | 0.961 |

| Alcohol, yes/no | 1.400 | 0.518–3.781 | 0.507 |

| Smokers, yes/no | 1.397 | 0.659–2.962 | 0.383 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.030 | 1.003–1.058 | 0.032 |

| DBP, mmHg | 0.981 | 0.938–1.025 | 0.387 |

| HR, bfm | 1.014 | 0.991–1.037 | 0.239 |

| RR, afm | 1.162 | 0.951–1.419 | 0.143 |

| Hb, g/dl | 1.156 | 0.865–1.544 | 0.327 |

| Hct, % | 1.048 | 0.960–1.145 | 0.293 |

| K, mmol/l | 1.345 | 0.596–3.038 | 0.476 |

| HbA1c > 6.8%, yes/no | 1.871 | 0.956–3.662 | 0.068 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 1.002 | 0.990–1.015 | 0.723 |

| AST, 1 U/L | 1.006 | 0.983–1.029 | 0.622 |

| ALT, 1 U/L | 1.024 | 1.000–1.048 | 0.055 |

| γ-GT, 1 U/L | 0.990 | 0.978–1.002 | 0.109 |

| MNA, 1 pt | 0.955 | 0.897–1.016 | 0.141 |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dl, yes/no | 6.177 | 2.895–13.182 | < 0.001 |

| NT-pro-BNP, pg/ml | 1.000 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.286 |

| UA > 6.0 mg/dl, yes/no | 3.706 | 1.900–7.227 | < 0.001 |

| Iron deficiency, yes/no | 2.875 | 1.081–7.649 | 0.034 |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | 0.797 | 0.642–0.990 | 0.040 |

| NYHA class I, yes/no | 2.035 | 0.061–68.111 | 0.692 |

| NYHA class II, yes/no | 6.435 | 0.644–64.263 | 0.113 |

| NYHA class III, yes/no | 1.706 | 0.171–16.982 | 0.649 |

MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, IHD ischemic heart disease, AF atrial fibrillation, SAS sleep apnea syndrome, CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate, Hb hemoglobin, Hct hematocrit, K Potassium, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, LDL low-density lipoproteins, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GT gamma-glutamyltransferase, MNA mini nutritional assessment, NT-pro-BNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, UA uric acid, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Table 4.

Multivariate stepwise Cox regression analysis on MACE

| HR | CI 95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dl, yes/no | 3.114 | 1.899–5.106 | < 0.001 |

| IHD, yes/no | 2.264 | 1.311–3.909 | 0.003 |

| UA > 6.0 mg/dl, yes/no | 2.183 | 1.275–3.737 | 0.004 |

| CKD, yes/no | 2.050 | 1.263–3.327 | 0.004 |

| Age, 10 years increase | 1.336 | 1.055–1.692 | 0.016 |

MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, IHD ischemic heart disease, UA uric acid, CKD chronic kidney disease

Discussion

This study, conducted in a population of middle-age outpatients with HF (both HFrEF and HFmrEF/HFpEF, NYHA class II and III) with several comorbidities, showed that there is an association between low SA levels and incidence of MACE during a median follow-up of 6.1 years. Specifically, SA values < 3.5 g/dl increased the risk of MACE by 3.1-fold. This association also persisted after adjustment of other demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, concomitant cardiovascular disease, nutritional status, liver and kidney function. The analysis of the processed ROC curve and measurement of relative AUC also demonstrated the accuracy of SA levels as predictor of MACE occurrence. These results are clinically relevant because albumin represents a routinely dosed analyte in daily clinical practice for HF patients with several comorbidities.

SA value < 3.5 g/dL has already been described as a risk factor for the development of MACE in both inpatients and outpatients [40, 41]. In fact, in the general population, hypoalbuminemia is a powerful and independent predictor of all-cause mortality and CV mortality [42, 43]. In addition, several studies have shown that hypoalbuminemia predicts the occurrence of HF in particular patients’ settings, such as CKD, elderly and diabetic patients independently of traditional CV risk factors and CV and non-CV comorbidities [38, 39]. In recent years, the prognostic role of low SA value in patients with HF has been established, but with different study population and methodology. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated a close association between reduced SA levels and poor prognosis in both acute and chronic HF [40, 42]. However, these studies considered mainly hospitalized or elderly subjects during a short follow-up, in addition patients showed frequently malnutrition, with a reduction in the functional reserve for a greater burden of comorbidities.

According with this, in a retrospective cohort study including 8,246 patients hospitalized for acute HF, hypoalbuminemia was an important predictor of 30-day and 1-year mortality in this setting, regardless of the HF phenotype, both HFrEF and HFpEF. Moreover, SA levels < 3.4 g/dl were associated with a two-fold increase in mortality risk at 1 year, in elderly patients hospitalized for acute HF. In this study more than 50% of the population showed SA levels < 3.4 g/dL, this could be explained by the higher number of comorbidities, especially liver and kidney disease, and by hospitalization that results in a major inflammatory burden, all conditions that may negatively affect circulating albumin levels [21]. Considering this, it is not surprising that in the sub-analysis of the CHARM study, after adjustment for confounding factors, albumin has lost its prognostic role during a median follow-up of 3.2 years, in fact in the multivariate model also parameters of liver dysfunction were included [7]. Furthermore, in the COAPT study, in patients with chronic HF and functional mitral insufficiency, having serum albumin levels < 4 g/dl was associated with reduced survival over a 4-year follow-up, but was not associated with an increased incidence of hospitalization [28].

In addition, an observational study of 5779 chronic HF patients with a mean age of 75 years confirmed the prognostic role of SA. Indeed, SA levels < 3.8 g/dl were associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR: 5.74, 95% CI: 4.08–8.07, p < 0.001) during a mean follow-up of 576 days. Moreover, in the study, SA levels at follow-up were available in 77% of enrolled patients, and it was seen that a decrease in albumin on follow-up was an independent predictor of increased mortality (HR: 2.58, 95% CI: 2.12–3.14, p < 0.001); confirming the prognostic role of SA in patients with chronic HF [29].

Our study has been conducted in middle-aged outpatients, with a median follow-up of 6.1 years excluding patients with liver dysfunction and malnutrition, well-known confounders that may affect SA levels and MACE occurrence. Of interest, in our study SA levels did not lose their predictive power even after correction for liver and kidney function, inflammation, and nutritional status. In addition, ROC curves analysis showed a predictive accuracy of SA levels both as continuous (AUC 0.708) and dichotomous (AUC 0.663) value for MACE occurrence. This result is consistent with previous data from our group reporting a high prevalence of SA < 3.5 g/dL in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients with a significant association with poor survival and enhanced occurrence of venous and arterial thrombosis [40]. In fact, hypoalbuminemia as a marker of underlying comorbidities, malnutrition, cachexia, and inflammatory state, may justify a poor clinical prognosis [6]. However, in the present study circulating albumin levels were mainly justified by hs-CRP, indicating that chronic low grade inflammation could represent the main predictor of SA levels.

Of interest, in our analysis IHD, UA and CKD doubled the risk of MACE in the study population and age as 10 years increase augmented the risk of 33%, thus confirming the prognostic value of these factors in particular in HF patients [44–46]. Thus, it is appropriate to ask whether hypoalbuminemia is only an epiphenomenon, a marker of comorbidities burden and inflammation, or it represents a causal factor for MACE. Of interest, besides to be the most represented protein in blood, albumin performs several physiological functions; in fact, it is primarily responsible for oncotic blood pressure and it can inhibit coagulation activation through modulation of hepatic biosynthesis of coagulation factors or heparin-like activity [47]. In addition, albumin exerts antiplatelet activity by blocking thromboxane A2 activity or via an oxidative stress-mediated mechanism [48]. In fact, hypoalbuminemia confirms its prognostic role in different clinic al settings, it increases the risk of MACE in acute and chronic HF, but also in hospitalized patients regardless of the cause of hospitalization and in T2DM. Furthermore, in our work, the prognostic role of circulating albumin levels is confirmed for long-term follow-up, even after correction for known confounding factors, in particular for clinical conditions that may result in hypoalbuminemia such as nutritional status, inflammation, liver and kidney disease [40, 41]. Finally, we observed that patients with SA values < 3.5 g/dl showed an increased risk for hHF compared to patients with higher SA values.

These results are in agreement with previous evidence demonstrating that reduced SA levels increase the risk of HF onset and progression. In fact, hypoalbuminemia, by reducing the colloid-osmotic pressure of the bloodstream, can promote pulmonary and systemic congestion with a consequent worsening of heart failure [11, 12]. According with this, as a future perspective, the potential prognostic role of serum albumin on risk on a combined endpoint of non-fatal events, and additionally on hHF and all-cause mortality, could be evaluated.

The present study has also several limitations; at first, it is a retrospective observational study. Another important limitation is represented by the imbalance of patients’ number according to two groups, the low percentage of women and the relatively small sample size with a long duration of enrollment. In addition, our study measured SA levels only at baseline and did not assess whether increasing SA levels could result in an improved prognosis and eventually a reduction in MACE; this issue deserves further investigations. This suggests a potential role of SA as a biomarker able to identify patients with chronic HF at high risk of developing MACE even in the absence of malnutrition and inflammation, in this context it is not possible to exclude a direct role of albumin in CV risk. According with this, it’s important to remark the potential negative impact of hypoalbuminemia on efficacy of antithrombotic and antiplatelet drugs, further increasing the risk of MACE [40, 41].

Considering the results of our study, it seems important to include SA levels among the variables considered in the scores used to stratify the risk of patients with HF such as the MECKI score for HFrEF, and to the variables considered in the MAGGIC meta-analysis for HF in the various phenotypes [49, 50].

Conclusion

This study, conducted on outpatients with HF and several comorbidities, showed that there is an association between lower SA levels and MACE occurrence during a long-term follow-up. In particular, a value < 3.5 g/dL of SA levels was associated with a 3.1-fold increased risk. Notably, this association persists even after adjustment for confounding factors such as age, inflammation, nutritional status, liver and kidney function. Present data suggest the potential usefulness of SA as prognostic factor for incident MACE and hHF in outpatients with HF during a long-term follow-up, in particular for a value < 3.5 g/dL and it may be helpful to identify patients with a lower response to antithrombotic drugs. Of interest, in the study population, the group with SA < 3.5 g/dl had a higher total mortality than the group with SA ≥ 3.5 g/dl. In conclusion, a considerable proportion of patients with chronic HF exhibits low SA levels and show a higher risk of MACE, hHF and total mortality.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors contribution

GA, VaC (Valentino Condoleo), CAP, MG, AF, DM, VeC (Velia Cassano), LB, DP, RM, TM, FA, GS, FV and AS participated in study conceptualization and design. GA, FV and AS participated in the methodology acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. GA, VaC, CAP, MG, AF, DM, VeC, LB, DP, RM, TM, FA, GS, FV and AS participated in writing–original draft preparation. GA, VaC, CAP, MG, AF, DM, VeC, LB, DP, RM, TM, FA, GS, FV and AS participated in writing–review and editing. GA, FV and AS participated in study supervision. GA, VaC, CAP, MG, AF, DM, VeC, LB, DP, RM, TM, FA, GS, FV, and AS read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli studi "Magna Graecia" di Catanzaro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This manuscript received no external funding.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not available.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee Azienda Ospedaliera universitaria “Mater Domini” approved the protocol in date 17/10/2012, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants (code protocol number 2012.63).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Human and animal rights statement

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O et al (2021) ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 42(36):3599–3726. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gale SE, Mardis A, Plazak ME, Kukin A, Reed BN (2021) Management of noncardiovascular comorbidities in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Pharmacotherapy 41(6):537–545. 10.1002/phar.2528 10.1002/phar.2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sciacqua A, Succurro E, Armentaro G, Miceli S, Pastori D, Rengo G, Sesti G (2023) Pharmacological treatment of type 2 diabetes in elderly patients with heart failure: randomized trials and beyond. Heart Fail Rev 28(3):667–681. 10.1007/s10741-021-10182-x 10.1007/s10741-021-10182-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang L, Zhao X, Huang L, Tian P, Huang B, Feng J, Zhou P, Wang J, Zhang J, Zhang Y (2023) Prevalence and prognostic im-portance of malnutrition, as assessed by four different scoring systems, in elder patients with heart failure. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 33(5):978–986. 10.1016/j.numecd.2023.01.004 10.1016/j.numecd.2023.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasini E, Aquilani R, Gheorghiade M, Dioguardi FS (2003) Malnutrition, muscle wasting and cachexia in chronic heart failure: the nutritional approach. Ital Heart J 4(4):232–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araújo JP, Lourenço P, Rocha-Gonçalves F, Ferreira A, Bettencourt P (2011) Nutritional markers and prognosis in cardiac ca-chexia. Int J Cardiol 146(3):359–363. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.042 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen LA, Felker GM, Pocock S, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Wang D, Yusuf S, Michelson EL, Granger CB, CHARM Investigators (2009) Liver function abnormalities and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program. Eur J Heart Fail 11(2):170–177 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Haehling S, Lainscak M, Springer J, Anker SD (2009) Cardiac cachexia: a systematic overview. Pharmacol Ther 121(3):227–252. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.009 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chojkier M (2005) Inhibition of albumin synthesis in chronic diseases: molecular mechanisms. J Clin Gastroenterol 39(4 Suppl 2):S143–S146. 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155514.17715.39 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155514.17715.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adlbrecht C, Kommata S, Hülsmann M, Szekeres T, Bieglmayer C, Strunk G, Karanikas G, Berger R, Mörtl D, Kletter K et al (2008) Chronic heart failure leads to an expanded plasma volume and pseudoanaemia, but does not lead to a reduction in the body’s red cell volume. Eur Heart J 29(19):2343–2350. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn359 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arques S, Ambrosi P (2011) Human serum albumin in the clinical syndrome of heart failure. J Card Fail 17(6):451–458. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.02.010 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche M, Rondeau P, Singh NR, Tarnus E, Bourdon E (2008) The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS Lett 582(13):1783–1787. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.057 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Chan CP, Yan BP, Zhang Q, Lam YY, Li RJ, Sanderson JE, Coats AJ, Sun JP, Yip GW et al (2012) Albumin levels predict survival in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 14(1):39–44. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr154 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metra M, Cotter G, El-Khorazaty J, Davison BA, Milo O, Carubelli V, Bourge RC, Cleland JG, Jondeau G, Krum H et al (2015) Acute heart failure in the elderly: differences in clinical characteristics, outcomes, and prognostic factors in the VERITAS Study. J Card Fail 21(3):179–188. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.012 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uthamalingam S, Kandala J, Selvaraj V, Martin W, Daley M, Patvardhan E, Capodilupo R, Moore S, Januzzi JL Jr (2015) Out-comes of patients with acute decompensated heart failure managed by cardiologists versus noncardiologists. Am J Cardi-ol 115(4):466–471. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.034 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arques S, Roux E, Stolidi P, Gelisse R, Ambrosi P (2011) Usefulness of serum albumin and serum total cholesterol in the prediction of hospital death in older patients with severe, acute heart failure. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 104(10):502–508. 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.06.003 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanagisawa S, Miki K, Yasuda N, Hirai T, Suzuki N, Tanaka T (2010) Clinical outcomes and prognostic factor for acute heart failure in nonagenarians: impact of hypoalbuminemia on mortality. Int J Cardiol 145(3):574–576. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.05.061 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.05.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwich TB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, MacLellan RW, Fonarow GC (2008) Albumin levels predict survival in patients with systolic heart failure. Am Heart J 155(5):883–889. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.043 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau GT, Tan HC, Kritharides L (2002) Type of liver dysfunction in heart failure and its relation to the severity of tricuspid re-gurgitation. Am J Cardiol 90(12):1405–1409. 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02886-2 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02886-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arques S, Roux E, Sbragia P, Gelisse R, Pieri B, Ambrosi P (2008) Usefulness of serum albumin concentration for in-hospital risk stratification in frail, elderly patients with acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol 125(2):265–267. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.094 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uthamalingam S, Kandala J, Daley M, Patvardhan E, Capodilupo R, Moore SA, Januzzi JL Jr (2010) Serum albumin and mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure. Am Heart J 160(6):1149–1155. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.004 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinugasa Y, Kato M, Sugihara S, Hirai M, Kotani K, Ishida K, Yanagihara K, Kato Y, Ogino K, Igawa O et al (2009) A simple risk score to predict in-hospital death of elderly patients with acute decompensated heart failure–hypoalbuminemia as an additional prognostic factor. Circ J 73(12):2276–2281. 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0498 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arques S, Pieri B, Biegle G, Roux E, Gelisse R, Jauffret B (2009) Comparative value of B-type natriuretic peptide and serum al-bumin concentration in the prediction of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients admitted for acute severe heart failure. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 58(5):279–283. 10.1016/j.ancard.2009.09.003 10.1016/j.ancard.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domínguez JP, Harriague CM, García-Rojas I, González G, Aparicio T, González-Reyes A (2010) Acute heart failure in patients over 70 years of age: Precipitating factors of decompensation. Rev Clin Esp 210(10):497–504. 10.1016/j.rce.2010.04.020 10.1016/j.rce.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López Castro J, Almazán Ortega R, De Juan P, Romero M, González Juanatey JR (2010) Mortality prognosis factors in heart failure in a cohort of North-West Spain. EPICOUR study. Rev Clin Esp 210(9):438–447. 10.1016/j.rce.2010.02.009 10.1016/j.rce.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Sharma R, Francis D, Knosalla C, Davos CH, Cicoira M, Shamim W, Kemp M et al (2003) Uric acid and survival in chronic heart failure: validation and application in metabolic, functional, and hemodynamic staging. Circulation 107(15):1991–1997. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065637.10517.A0 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065637.10517.A0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson CE, Bezlyak V, Tsorlalis IK et al (2009) Multimarker laboratory testing in acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) how much prognostic information do novel biomarkers BNP, troponin and CRP provide in addition to routine laboratory tests? Eur Heart J 30:711 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng KY, Ambrosy AP, Zhou Z, Li D, Kong J, Zaroff JG, Mishell JM, Ku IA, Scotti A, Coisne A, Trial Investigators COAPT et al (2023) Association between serum albumin and outcomes in heart failure and secondary mitral regurgitation: the COAPT trial. Eur J Heart Fail 25(4):553–561. 10.1002/ejhf.2809 10.1002/ejhf.2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotsman I, Shauer A, Zwas DR, Tahiroglu I, Lotan C, Keren A (2019) Low serum albumin: A significant predictor of reduced survival in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Cardiol 42(3):365–372. 10.1002/clc.23153 10.1002/clc.23153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Iskandarani M, El Kurdi B, Murtaza G, Paul TK, Refaat MM (2021) Prognostic role of albumin level in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(10):e24785 10.1097/MD.0000000000024785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schupp T, Behnes M, Rusnak J, Ruka M, Dudda J, Forner J, Egner-Walter S, Barre M, Abumayyaleh M, Bertsch T et al (2023) Does albumin predict the risk of mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock? Int J Mol Sci 24(8):7375. 10.3390/ijms24087375 10.3390/ijms24087375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chao P, Cui X, Wang S, Zhang L, Ma Q, Zhang X (2022) Serum albumin and the short-term mortality in individuals with congestive heart failure in intensive care unit: an analysis of MIMIC. Sci Rep 12(1):16251. 10.1038/s41598-022-20600-1 10.1038/s41598-022-20600-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, Guigoz Y, Morley JE, Chumlea W, Salva A, Rubenstein LZ et al (2006) Overview of the MNA - Its history and challenges. J Nutr Health Aging 10(6):456–463 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28(7):412–419. 10.1007/BF00280883 10.1007/BF00280883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T et al (2009) CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150(9):604–612. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD (2007) Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 50(22):2173–2195. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Clinical Cardiology Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Cardiovascular Radi-ology and Intervention Council; Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Working Group; Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Coun-cil, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups (2007) The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation. 115(20):e478–e534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Harnett JD, Foley RN, Kent GM, Barre PE, Murray D, Parfrey PS (1995) Congestive heart failure in dialysis patients: prevalence, incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Kidney Int 47(3):884–890. 10.1038/ki.1995.132 10.1038/ki.1995.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filippatos GS, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, Fonarow GC, Love TE, Aban IB, Iskandrian AE, Konstam MA, Ahmed A (2011) Hypoalbuminaemia and incident heart failure in older adults. Eur J Heart Fail 13(10):1078–1086. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr088 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sciacqua A, Andreozzi F, Succurro E, Pastori D, Cammisotto V, Armentaro G, Mannino GC, Fiorentino TV, Pignatelli P, Angiolillo DJ et al (2021) Impaired clinical efficacy of aspirin in hypoalbuminemic patients with diabetes mellitus. Front Pharmacol 22(12):695961. 10.3389/fphar.2021.695961 10.3389/fphar.2021.695961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Violi F, Novella A, Pignatelli P, Castellani V, Tettamanti M, Mannucci PM, Nobili A. REPOSI (REgistro POliterapie SIMI, Società Italiana di Medicina Interna) Study Group (2023) Low serum albumin is associated with mortality and arterial and ve-nous ischemic events in acutely ill medical patients. Results of a retrospective observational study, Thromb Res. 225:1–10, doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2023.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Herrmann FR, Safran C, Levkoff SE, Minaker KL (1992) Serum albumin level on admission as a predictor of death, length of stay, and readmission. Arch Intern Med 152:125e30 10.1001/archinte.1992.00400130135017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyons O, Whelan B, Bennett K, O’Riordan D, Silke B (2010) Serum albumin as an outcome predictor in hospital emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med 21(1):17–20. 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.10.010 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverdal J, Sjöland H, Bollano E, Pivodic A, Dahlström U, Fu M (2020) Prognostic impact over time of ischaemic heart disease vs. non-ischaemic heart disease in heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 7(1):264–273. 10.1002/ehf2.12568 10.1002/ehf2.12568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sciacqua A, Perticone M, Tassone EJ, Cimellaro A, Miceli S, Maio R, Sesti G, Perticone F (2015) Uric acid is an independent pre-dictor of cardiovascular events in post-menopausal women. Int J Cardiol 15(197):271–275. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.069 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen M, Rumjaun S, Lowe-Jones R, Ster IC, Rosano G, Anderson L, Banerjee D (2020) Management and outcomes of heart failure patients with CKD: experience from an inter-disciplinary clinic. ESC Heart Fail 7(5):3225–3230. 10.1002/ehf2.12796 10.1002/ehf2.12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ronit A, Kirkegaard-Klitbo DM, Dohlmann TL, Lundgren J, Sabin CA, Phillips AN, Nordestgaard BG, Afzal S (2020) Plasma albumin and incident cardiovascular disease: results from the CGPS and an updated meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 40(2):473–482. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313681 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maclouf J, Kindahl H, Granström E, Samuelsson B (1980) Interactions of prostaglandin H2 and thromboxane A2 with human serum albumin. Eur J Biochem 109(2):561–566. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04828.x 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agostoni P, Corrà U, Cattadori G, Veglia F, La Gioia R, Scardovi AB, Emdin M, Metra M, Sinagra G, Limongelli G, et al. MECKI Score Research Group (2013) Metabolic exercise test data combined with cardiac and kidney indexes, the MECKI score: a multiparametric approach to heart failure prognosis. Int J Cardiol. 167(6):2710–2718. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJ, Maggioni A, Køber L, Squire IB, Swedberg K, Dobson J, Poppe KK, Whalley GA et al (2013) Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J 34(19):1404–1413. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs337 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not available.