Abstract

Importance:

Climate change may increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes by causing direct physiologic changes, psychological distress, and disruption of health-related infrastructure. Yet, the association between numerous climate change-related environmental stressors and the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events has not been systematically reviewed.

Objective:

To review the current evidence on the association between climate change-related environmental stressors and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Evidence Review:

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched to identify peer-reviewed publications evaluating associations between environmental exposures and cardiovascular mortality, acute cardiovascular events, and related healthcare utilization. Studies that only examined non-wildfire sourced particulate air pollution were excluded. Two investigators independently screened 20,798 articles and selected 2,564 for full-text review. Study quality was assessed using the Navigation Guide framework. Findings were qualitatively synthesized as substantial differences in study design precluded quantitative meta-analysis.

Findings:

Of 492 observational studies that met inclusion criteria, 182 examined extreme temperature, 210 ground-level ozone, 45 wildfire smoke, and 63 extreme weather events such as hurricanes, dust-storms, and droughts. These studies presented findings from 30 high-income, 17 middle-income, and 1 low-income countries. The strength of evidence was rated as sufficient for extreme temperature, ground-level ozone, tropical storms/hurricanes/cyclones, and dust storms, limited for wildfire smoke, and inadequate for drought and mudslides.

Exposure to extreme temperature was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, but the magnitude varied with temperature and duration of exposure. Ground-level ozone amplified the risk associated with higher temperatures and vice versa. Extreme weather events such as hurricanes were associated with increased cardiovascular risk that persisted for many months after the initial event. Some studies noted a small increase in cardiovascular mortality, out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, and hospitalizations for ischemic heart disease after exposure to wildfire smoke, while others found no association. Older adults, minortized populations, and lower wealth communities were disproportionately affected.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Several environmental stressors that are predicted to increase in frequency and intensity with climate change are associated with increased cardiovascular risk, but data on outcomes in low-income countries are lacking. Urgent action is needed to mitigate climate change-related cardiovascular risk, particularly in vulnerable populations.

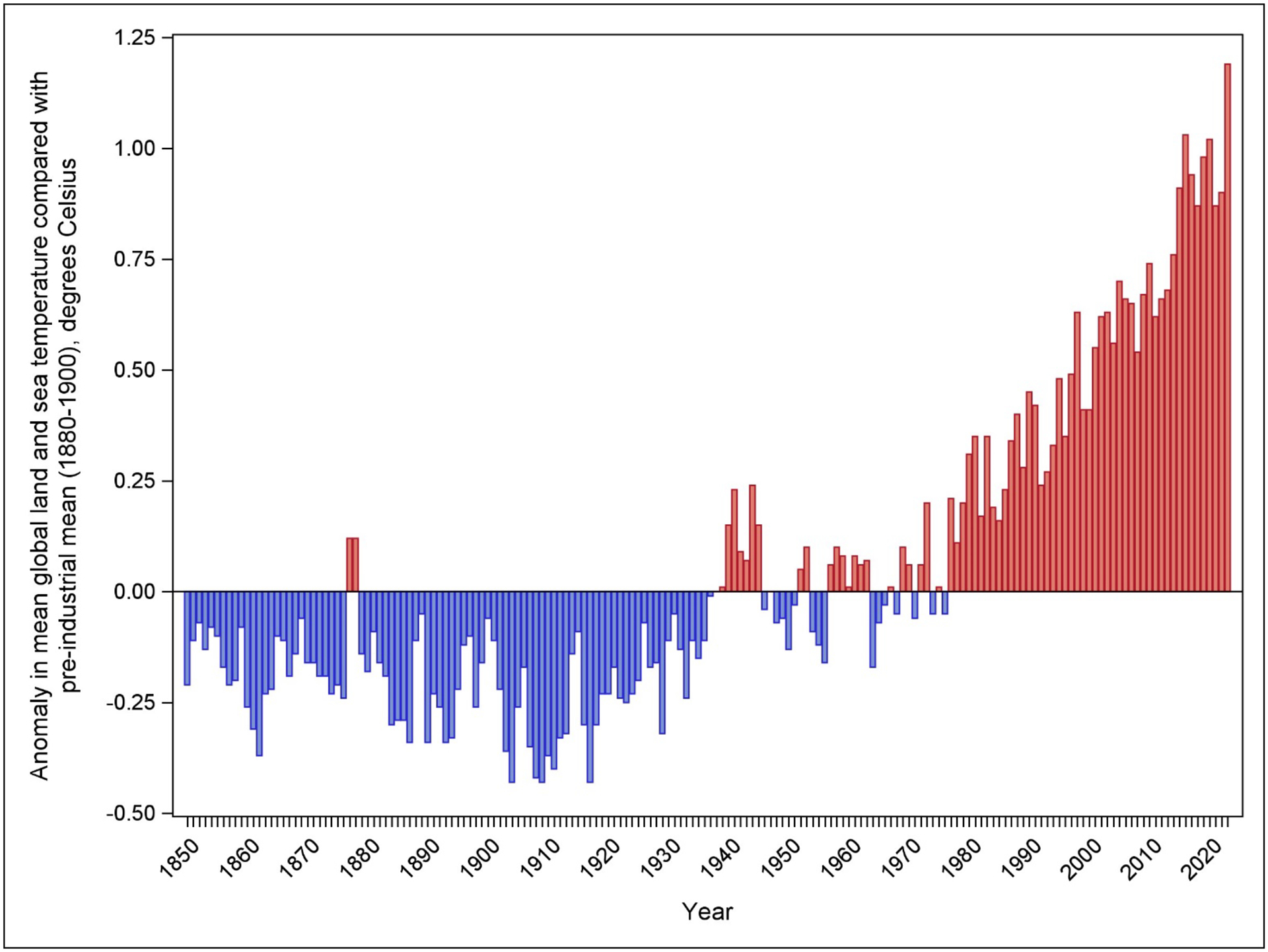

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally.1 Substantial improvements in CVD prevention and treatment have produced a 33% decline in age-adjusted CVD mortality in the past two decades,1 but climate change may undermine this progress. Combustion of fossil fuels over the past 150 years has greatly increased the atmospheric concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane and caused climate change, which includes long-term shifts in average weather patterns, disturbance of ecosystems, and rising sea levels (Table 1).2,3 A core feature of climate change is global warming. Our planet is now 1.4°C (2.5°F) warmer than in the late nineteenth century and the 10 warmest years on record have all occurred in the past decade (Figure 1).4,5

Table 1.

Key Terminology in Climate Change.

| Climate change | Long-term shifts in global temperatures and weather patterns. These shifts may be natural, such as through variations in the solar cycle. However, since the 1800s, human activities have been the undisputable primary driver of climate change, primarily due to burning fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas. Global warming is one component of climate change, which is causing disruption of ecosystems and rising sea levels. |

| Global warming | Long-term heating of Earth’s surface observed since the pre-industrial period (between 1850 and 1900) due to human activities, primarily fossil fuel burning, which increases heat-trapping greenhouse gas levels in Earth’s atmosphere. Rising land and water temperatures set up positive feedback cycles: because water reflects less heat than ice, melting of polar ice caps contributes to further warming. Similarly, melting of the tundra ice exposes trapped carbonaceous material that releases additional carbon dioxide as it decays, setting up a vicious cycle. |

| Heat wave | A period of abnormally hot weather. The temperature threshold and duration of heat that is used to define a heat wave varies substantially by location, season, and study design. Adverse health outcomes vary by location and the population in consideration, but often start on the first day of high temperatures. |

| Cold spell | A period of abnormally cold weather. The temperature threshold and duration of cold that is used to define a cold spell varies substantially by location, season, and study design. Adverse health outcomes vary by location and the population in consideration, and may start on the first day of cold temperatures or be delayed by few days. |

| Ground-level ozone | Ground-level ozone, also known as tropospheric ozone, is an air pollutant that is created by chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds. This occurs when pollutants emitted by cars, power plants, industrial boilers, refineries, chemical plants, and other sources chemically react in the presence of sunlight. Higher temperatures accelerate the production of ground-level ozone. |

| Climate Penalty | Amplification of air pollution by climate change. For instance, higher temperatures increase production of ground-level ozone, both of which are associated with worse health outcomes. This is of particularly concern in Asia, which is home to a quarter of the world’s population and where many countries are already grappling with enormous epidemics of premature cardiovascular disease. |

| Carbon sinks | Natural resources, such as forests and oceans, that absorb more carbon dioxide than they release into the atmosphere. |

Figure 1. Global Temperature Trends 1881–2024.

The figure shows negative (blue) and positive (red) deviations from the average 20th century land temperature from 1850 to 2023. Despite year-on-year variability, a clear trend of warming temperatures is noted. All 10 of the warmest years on record have occurred in the past decade, and 2023 was the warmest year on record since record-keeping began in 1850. Data from the National Centers for Environmental Information at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.65

Climate change may affect cardiovascular health through several pathways (Figure 2). First, exposure to environmental stressors produces physiologic changes – such as increased heart rate and plasma viscosity with extreme heat exposure or local and systemic inflammation after inhalation of airborne particulate matter.6–10 Second, coping with extreme weather events increases stress, anxiety, and depression, and these adverse mental health effects may contribute to cardiovascular risk.11 Third, extreme events like hurricanes or floods disrupt healthcare infrastrucrture or healthcare delivery (e.g., through power outages or disrupted supply chains).12 Fourth, long-term socioeconomic effects of climate change may adversely affect cardiovascular health. For instance, changing rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, and saltwater intrusion into aquifers are projected to produce declines in agricultural productivity in many parts of the world; the resulting food insecurity may compromise nutritional quality and cardiovascular health.13 Climate-related migration will change where we seek and supply cardiovascular care. Sea level-rise may damage exisiting healthcare and transportation infrastructure, compromising healthcare access and delivery. Collectively, these pathways have the potential to undermine the cardiovascular health of the population, but the magnitude of this effect and the populations that will be particularly susceptible are uncertain.

Figure 2. Climate Change and Cardiovascular Health.

Climate change may adversely affect cardiovascular health through several pathways, including direct effects on physical and mental health and indirect effects from disruption of healthcare delivery or worsening social determinants of health. The relative importance of each of these mechanisms may vary by community and over time, but collectively they have the potential to undermine the substantial gains in cardiovascular health achieved globally in recent decades.

Therefore, we undertook a systematic review to summarize the associations between climate change-related events and cardiovascular health, clarify implications for clinicians and health systems, and identify knowledge gaps to direct future investigation.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Libary for peer reviewed English-language publications from January 1, 1970 through November 15, 2023 that evaluated associations between: (i) extreme ambient temperatures, (ii) wildfires and resulting particulate air pollution; (iii) ground level ozone; (iv) extreme weather events such as hurricanes, dust storms, or drought; (v) sea level rise; (vi) salt water intrusion, and (vii) climate-related migration with acute cardiovascular events (i.e., ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cardiac arrest, arrhythmias, and stroke), cardiovascular mortality, and CVD healthcare utilization. We excluded studies that only examined the well-established causal relationship between non-wildfire sourced particulate air pollution and CVD11,14 or exclusively focused on occupational exposures. Additional studies were identified through a review of the bibliographies of relevant publications (See Table S1 in the Appendix for full search strategy and included health outcomes). The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022320923) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.15,16 Since the review exclusively used publicly available data, the institutional review board at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center deemed that it did not constitute human subjects research.

Two investigators independently screened all included articles. For studies that met inclusion criteria, we extracted study design, exposure assessment, association of exposure with study outcomes, and, if reported, lag structure and observed heterogeneity.

The quality of studies was evaluated using the Navigation Guide framework for reviews of observational studies in environmental health.17–19 Briefly, we assessed each study for risk of bias (separately for exposure, outcome, and confounders, and overall), evaluated the quality of evidence across studies, and examined the strength of evidence across studies. See Appendix for additional details (Table S2). Country-level income category was assigned using the World Bank 2021 classification.20 Race/ethnicity, where available, were reported as defined by individual studies. Study-level estimates were qualitatively synthesized as substantial study design differences precluded quantitative meta-analysis. The review was performed using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

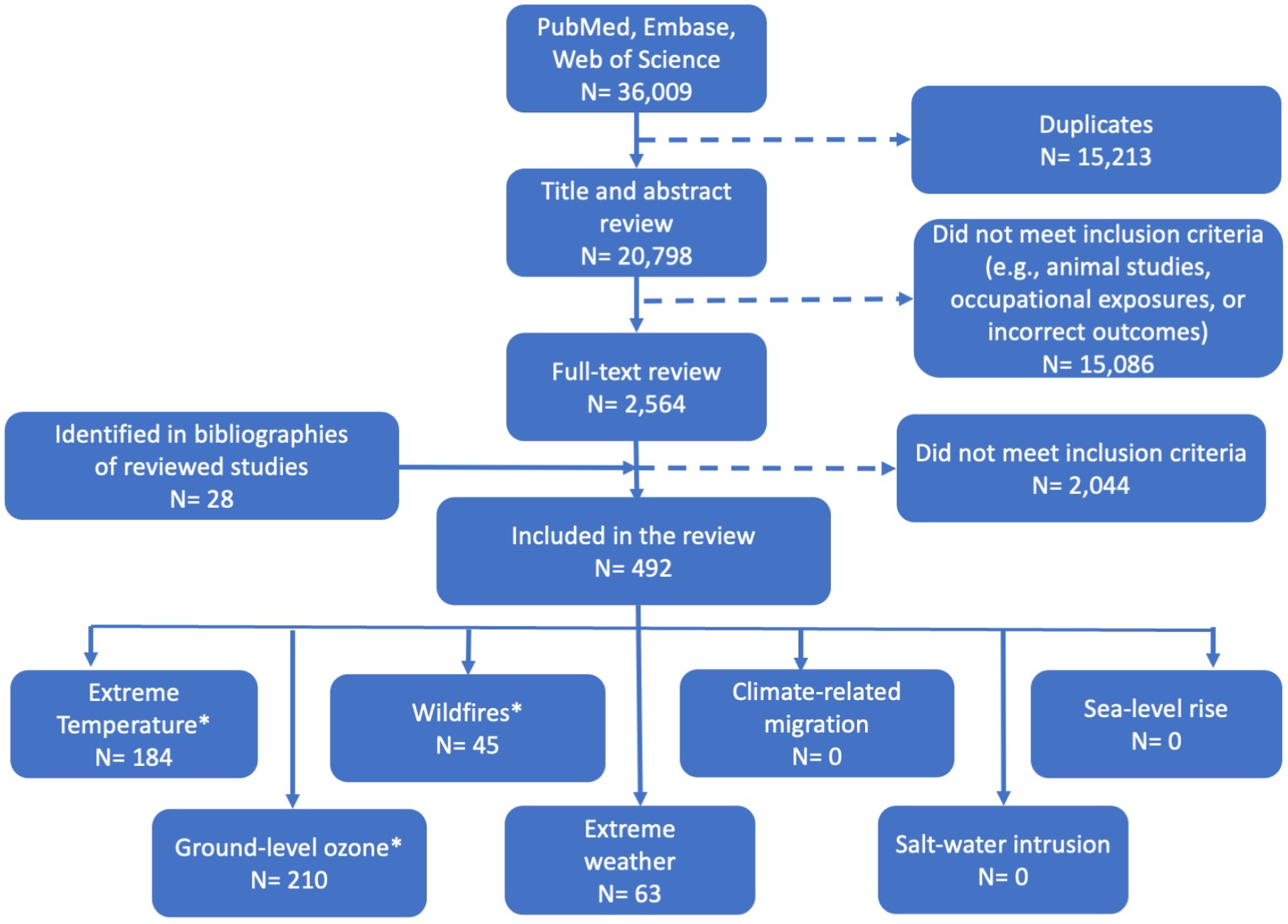

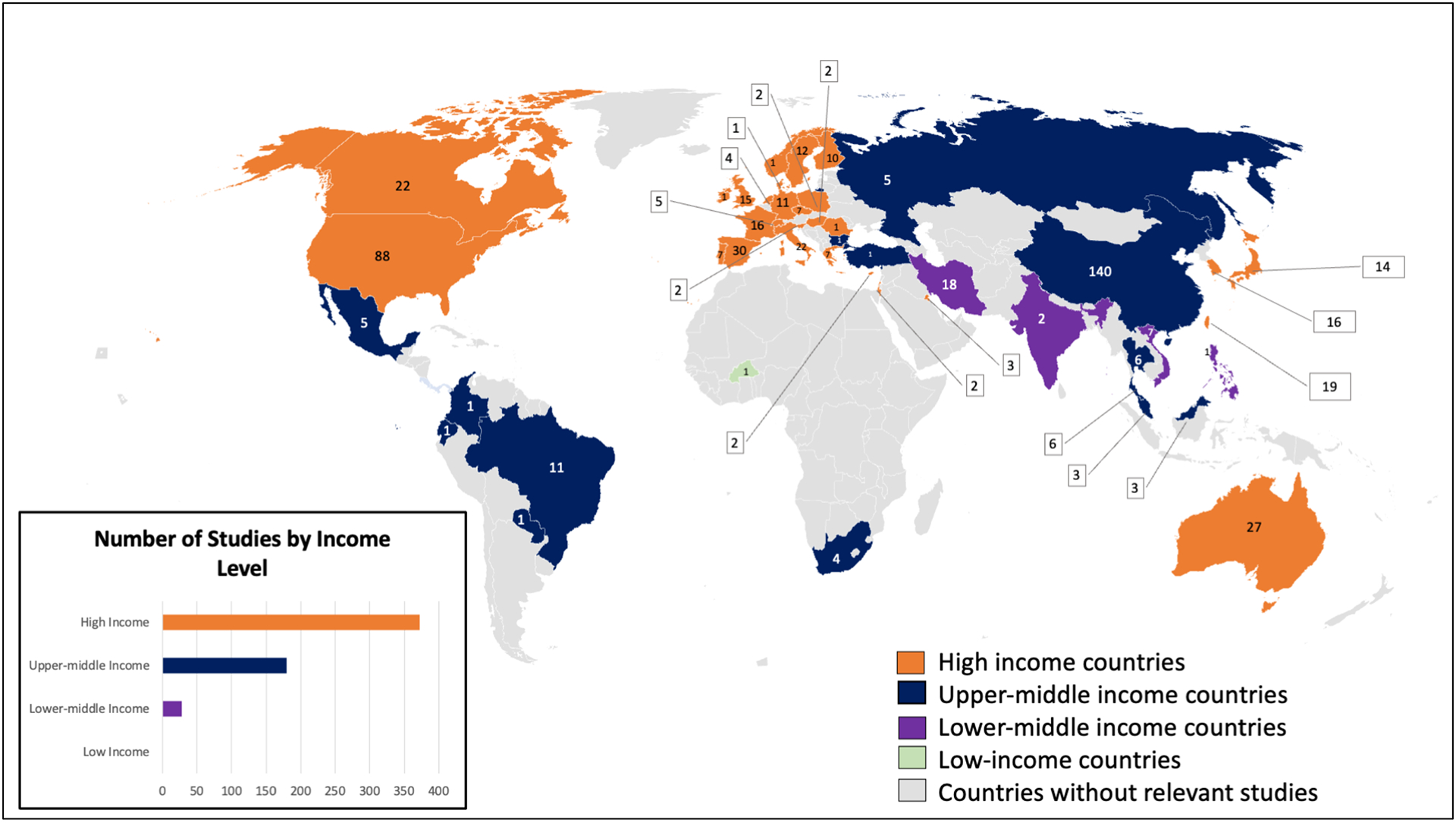

Two investigators independently screened 20,798 articles, of which 2,564 were selected for full-text review based on relevancy of titles and abstracts (Figure 3). A total of 492 studies met inclusion criteria (Table S3), including 167 extreme heat, 97 extreme cold, 210 ground-level ozone, 45 wildfires, and 63 extreme weather studies (Figure 3). We identified no studies evaluating the relationship between sea level-rise, salt-water intrusion, or climate-related migration and cardiovascular outcomes. The studies reported data from 30 high income, 13 upper-middle income, 4 lower-middle income countries, and one low income countries (Figure 4). All studies were observational in design. 446 studies (91%) were rated with low risk or probably low risk of bias (Figure S1). Across all studies, the quality of evidence was rated as high for extreme temperature, tropical storms, and dust storms; moderate for ozone and wildfire smoke; and low for other exposures. The overall strength of evidence was rated as sufficient for extreme temperature, ozone, tropical storms, and dust storms (i.e., the conclusion unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies); limited for wildfire smoke (i.e., the observed effect could change as more information becomes available); and inadequate for floods, drought, and mudslides (i.e., more information may allow an assessment of effects).

Figure 3. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases for relevant publications from 1970 to 2023. Two investigators independently screened the titles and abstracts of 20,798 articles, of which 2,564 were considered for full-text review. A total of 492 studies were included in the final analysis.

*Six studies assessed both extreme temperature and ground-level ozone, 1 study assessed both extreme tmpereature and wildfires, and 1 study assessed both wildfires and extreme weather(dust storms)

Figure 4. Countries with Studies Examining the Association Between Climate Change and Cardiovascular Health.

The 492 studies that met inclusion criteria for this systematic review reported data from 30 high-income, 13 upper-middle income, 4 lower-middle income countries, and one low-income countries. Numbers indicate the number of included studies from each country. Several studies included data from more than one country. The dearth of studies from low- and middle-income countries is problematic both because of the large number of people at risk and because of the greater expected impact of climate change in these countries.

Extreme Heat and Heat Waves

The majority of studies examining extreme heat exposure reported an association with increased cardiovascular mortality (87 of 101 studies, 86%) (Table S4). For instance, in a study of all counties in the contiguous U.S., each additional day of heat exposure (defined as heat index ≥90 °F [32.2 °C] and in the 99th percentile of the maximum heat index for that day) was associated with a 0.12% (95% CI, 0.04%-0.21%; P=0.004) increase in monthly cardiovascular mortality among adults 20 years or older.21 The authors estimated that between 2008 and 2017, an estimated 5,958 (95% CI, 1,847–10,069) excess CVD deaths were associated with heat exposure.21 Alahmad and colleagues found similar results in a multi-country cohort from 567 cities in 27 countries: extreme heat (99th percentile) was associated with higher risk of dying from any CVD, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.22 Since the risk typically rose starting on the day of exposure, short lags fully captured the association of extreme heat and heat waves with CVD.

Among a subset of studies that examined heatwaves, i.e., sustained periods of high termperature typically defined as lasting two or more days, 24 of 28 (85%) reported an association with increased cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovascular risk increased with higher temperatures and longer heatwaves.23 Studies examining the association of extreme heat or heatwaves with cardiovascular morbidity or healthcare utilization found less consistent results than studies examining cardiovascular mortality (35 of 69 morbidity studies, or 51%, reported a positive association) (Table S4).

The association between heat and CVD varied by characteristics of the exposed population and by location. Age greater than 65 years, male gender, minoritized populations, pre-existing cardiovascular or pulmonary conditions, and employment in outdoor work were associated with increased CVD risk following heat exposure.21,23 Residence in urban heat islands – areas warmer than surrounding areas due to the relative lack of vegetation, increased presence of heat-absorbing manmade surfaces (i.e. concrete), and inefficient ventilation of warm air – was associated with increased risk of CVD,24 whereas access to air-conditioning was protective. There was marked regional variation, with cardiovascular hospitalizations rising at lower temperatures in cooler climates than in warmer climates.

Extreme Cold and Cold Spells

Although climate change is primarily projected to increase episodes of extreme heat globally, some regions may paradoxically experience increases in extremely cold weather due to arctic ice melt and changes in atmospheric and ocean currents.25 Forty nine of 60 studies (82%) found associations between cold exposure and cardiovascular mortality, but the magnitude of the association ranged widely (from 3% to 172% increase, varying by region and temperature thresholds used) (Table S5).26,27 This association appeared to persist after accounting for seasonality and the concurrent burden of influenza cases (which may confound the association of extreme cold with cardiovascular outcomes). Longer lag periods were required to capture the full association of cold with cardiovascular mortality because the increased risk peaked days to weeks after cold exposure.24 Among a subset of 11 studies evaluating cold-spells, defined as extreme low temperatures lasting two or more days, 10 studies (91%) reported an association with increased CVD mortality.

The majority of studies (33 of 43, 77%) demonstrated in an association between cold exposure and increased cardiovascular morbidity or healthcare utilization. For instance, cold-spells were associated with increases in CVD-related emergency department visits in Canada28 and stroke hospitalizations in Australia.29

Women and older individuals were more susceptible to the increased cardiovascular risk associated with extreme cold exposure.30,31 Differences in outcomes by socioeconomic level appeared to be less pronounced than with heat exposure.24

Ground-level Ozone

High temperatures increase ground-level ozone production by accelerating photochemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds. Of studies that evaluated increased ground-level ozone concentrations, 44 of 71 (62%) studies identified an association with icreased CVD mortality (Table S6). The association with cardiovascular morbidity was less consistent: 82 of 143 (57%) reported increased CVD morbidity, 51 (36%) reported no change, and 10 (7%) reported a negative correlation. In studies based out of the United States and France, ozone exposure after a myocardial infarction were associated with increased risk of recurrent ischemic events (cerebral or cardiac; odds ratio [OR], 1.074; 95% CI 1.016–1.135 per 10 μg/m3 in straight 8-hour mean ambient ozone concentration), worse anginal symptoms, and higher cardiovascular mortality.32,33 In contrast, a study out of Boston, Massachusetts of more than 15,000 patients found no significant correlation between elevated ground-level ozone and admission for myocardial infarction (proportional increase, 0.90%; 95% CI −8.36%-6.55%).34

A positive interaction between ozone levels and temperature on adverse cardiovascular events was observed in 11 of 16 studies (69%), with higher levels of ozone amplifying the association of high temperature or high temperature amplifying the association of ground-level ozone exposure.35 For instance, an increase in the 24-hour mean ambient ozone concentration was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality when the temperature was above the 75th percentile but not when temperatures were less than the 25th percentile.36

Wildfires

The 45 studies evaluating the association between wildfire smoke and CVD used varying definitions of fire exposure (e.g., aerial photographs of smoke versus ground-level monitoring of particulate pollution) and outcomes (Table S7). As a result, the findings were less consistent: 4 of 10 (40%) examining the association with cardiovascular mortality found a positive association whereas 6 of 10 (60%) did not. A large study using a global chemical transport model to estimate wildfire-related PM2.5 and daily death counts from 749 cities in 43 countries and regions found a 1.7% (95% CI, 1.2–2.1%) increase in the pooled relative risk of cardiovascular mortality associated with a 10 μg/m3 increase in the 3-day moving average of wildfire-related PM2·5 concentrations.37 But a significant association was not seen with Australian bushfire smoke using particulate matter data from fixed monitoring sites.38 Because wildfire smoke can be carried by the wind over very long distances, the association with CVD outcomes was detectable thousands of miles from the source of the fire.

Studies also reported variable associations with cardiovascular morbidity or healthcare utilization, with 16 of 37 (43%) studies reporting a positive association. Of these, the strongest associations were observed for increased emergency department visits or hospitalization for ischemic heart disease39–41 and cardiac arrest.39,42–44 Wildfire smoke exposure was associated with more emergency department visits for heart failure, arrhythmias, and hypertension.39,41,45,46 Among studies that reported an association with CVD, the association peaked on lag days 1–3 but extended up to a week after smoke exposure.39,47,48

Populations with lower baseline air pollution exposure, older adults, and residents of lower-wealth communities had larger increases in adverse CVD outcomes related to wildfire smoke exposure.39,45,49 For instance, in Australia, indigenous people exposed to wildfire smoke were more likely to be hospitalized for ischemic heart disease than non-indigenous people (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.14–2.55) despite similar exposure levels.46

Extreme Weather Events

Tropical storms, Hurricanes/Cyclones, Floods, and Mudslides

Of studies examining the association of hurricanes or cyclones (n=17), floods (n=3), and mudslides (n=1), the majority reported increased CVD mortality (8 of 9 studies, 89%) and worse cardiovascular morbidity (17 of 20 studies, 85%) during these events (Table S8–10). Notably, the increased CVD risk outlasted the extreme weather event in several studies. For instance, among U.S. adults 65 years of age or older exposed to Hurricane Sandy, cardiovascular morbidity was greater during the storm than during similar periods before and after the storm (rate ratio, 2.65; 95% CI, 2.64–2.66),50 and risk remained elevated up to 12 months after the storm (rate ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 2.64–2.65).50 Disrupted healthcare access due to Hurricane Sandy was also associated with worse blood pressure control among U.S. veterans after two years.51 Women and older adults may be at greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events from hurricanes.52,53 Hurricanes also affected mental health, an important determinant of CVD risk. Katrina survivors who developed post-traumatic stress disorder or depression were more likely to require hospital admission or die from CVD.54,55 Given the small number of studies that examined floods and mudslides, their association with cardiovascular outcomes was uncertain (Tables S9 and S10).

Dust Storms

Of studies examining the relationship between dust storms and adverse CVD outcomes (n=30), a majority reported an association with increased CVD mortality (12 of 19 studies, 63%) or CVD morbidity (9 of 12 studies, 75%) (Table S11). Dust storms were associated with a 65% increase in the odds of hospitalization for myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.18–2.29) in Japan56 and 83% relative increase in mortality from ischemic heart disease (RR, 1.183; 95% CI, 1.017–1.348) in China.57

Drought

Four studies examined the association of drought with CVD, all of which adjusted for the effect of temperature. (Table S12). Of three studies that examined cardiovascular mortality, two reported a small but statistical increase in cardiovascular mortality during drought compared with non-drought reference periods. Drought was associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes in Portugal (RR for cardiovascular mortality, 1.011; 95% CI, 1.004–1.019),58 but not in the United States.59

Discussion

This systematic review of 492 studies yields several key insights regarding the relationship between climate change-related environmental stressors and cardiovascular health. First, the majority of included studies found that extreme ambient temperatures, ground-level ozone, and severe weather events such as hurricanes and dust storms were associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. On the other hand, the association with adverse cardiovascular outcomes was less certain for exposure to wildfire smoke and some extreme weather events such as floods, mudslides and drought. Second, the temporal association between the exposure and cardiovascular events was variable: the increased risk was observed on the day of the exposure, such as with extreme heat, or delayed days to weeks, as in the case of extreme cold. For some environmental exposures, the increased risk persisted well beyond the inciting event – with increased cardiovascular risk noted 12 months after a severe storm. Third, there may be an interaction among some stressors: heat-fueled production of ground-level ozone may amplify the increased cardiovascular risk associated with high temperatures. This is of particular concern in Asia, which is home to a quarter of the world’s population and where many countries are already grappling with extreme temperatures, high concentrations of ozone and other pollution, and epidemics of premature CVD. Fourth, people living hundreds of miles from the source may experience increased CVD risk, as with wildfire smoke and dust-storms. Fifth, while all segments of the population are likely to be affected in some way, climate change-related CVD risk disproportionately affects older adults, individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups, and lower wealth communities. This may be due to differences in baseline health and nutrition status, access to healtcare, and available resources to respond to extreme weather.24 Thus, climate change may compound health inequities that arise from socioeconomic disadvantage and structural racism.60

This review identified major knowledge gaps and prioroity areas for future investigation. Only one study was conducted in a low-income country (Burkina Faso) and only five were based in Africa. This gap is particularly alarming given expected greater harms of climate change in low- and middle-income countries.61 Studying the health effects of climate change in low-income countries will require investments in both environmental measurements as well as surveillance systems for accurate collection of health data. The design of included studies precluded causal attribution; future studies applying newer causal inference frameworks should address this limitation. Future studies should examine whether the association varies by exposure subtypes (e.g., whether wildfires are burning natural vegetation or building materials), characterize the sequalae of recurrent exposures (e.g., consecutive summers of active wildfires), and clarify the biological and socioeconomic mechanisms underlying the observed association between environmental exposures and CVD outcomes. For instance, although the association of environmental exposures with long-term CVD outcomes may be partially explained by disruption in health care delivery, changes in health care seeking behavior, and declines in mental health, further defining causal mechanisms (e.g., epigenetic changes resulting from chronic stress) may help identify solutions. Because of substantial individual variability in risk, a “climate change CVD risk score” that helps clinicians identify patients at greatest risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes with environmental stressors is urgently needed.62,63 Future studies should help identify interventions to mitigate climate change-related cardiovascular risk, such as the use of high-efficiency particulate air purifiers during periods of high levels of wildfire smoke levels.

Despite these knowledge gaps, our findings have important clinical implications. Clinicians should consider evaluating each patient’s CVD risk from climate change-exposures based on individual, community, and health system attributes.64 For instance, does the patient have higher-than-average exposure to environmental stressors (e.g., employment that requires outdoor work), higher susceptibility (e.g., presence of cardiorespiratory comorbidities), or limited resources to avoid the exposure (e.g., housing without air conditioning)? Clinicians should be aware that heat-related cardiovascular risk varies by community, pradoxically rising at lower temperatures in cooler areas (such as the northwestern U.S., where homes do not typically have air-conditioning) compared with areas accustomed to high temperatures (such as the southwestern U.S., where air-conditioning is widely available).28 Conversely, cold-related cardiovascular risk is greater in the southern U.S. than in the north.24 Thus, local data are necessary to guide policy and clinical practice. In regions with frequent wildfire smoke days, susceptible patients should learn how to interpret local air quality indices and stay indoors during periods of high wildfire-smoke levels. In areas prone to extreme weather events such as hurricanes or flooding, clinicians should assist patients in developing contingency plans to ensure uninterrupted access to medications and healthcare as needed.

Our study has a few limitations. Study heterogeneity, particularly with regard to how exposures are ascertained and quantified, limits inter-study comparability. For instance, there is no unviersal definition of what constitutes extreme heat, how many days of extreme heat constitutes a heat wave, or how one measures wildfire smoke exposure. Universal definitions would enhance comparability among studies and allow clinicians and policy-makers to apply the findings to their own contexts. Our evaluation of temperature focused on studies examining the association of extreme temperature and cardiovascular health and therefore excluded studies examining more moderate but “non-optimal” temperatures. Our analysis was restricted to studies that examined fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular outcomes and therefore cannot address questions about underlying mechanism or potential mitigation strategies, which are the focus of future work.

Conclusion

Exposure to climate change-related environmental stressors is associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality and morbidity, but persistent knowledge gaps include the effect in low-income countries, the long-term cardiovascular sequelae of recurrent environmental events, and the interplay between climate change and social determinants of health. Continued gains in cardiovascular health require urgent action to identify and implement cost-effective interventions to reduce climate change-related CVD risk, particularly in vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Is there an association between climate change-related environmental stressors and cardiovascular health outcomes?

Findings:

In this systematic review of 492 observational studies, exposure to climate change-related exposures like extreme temperature and hurricanes was strongly associated with increased morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease, while increased risk after exposure to wildfire smoke was less certain. Older adults, individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups, and lower wealth communities were disproportionately affected, while data on outcomes in low-income countries were lacking.

Meaning:

Urgent action is needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and lower climate change-related cardiovascular risk in vulnerable populations.

SOCIAL MEDIA POST.

Systematic review finds that environmental stressors like extreme temperature, hurricanes, and wildfires are associated w/ increased CV morbidity & mortality. Urgent action is needed to mitigate climate-related CV risk, esp. in vulnerable populations

FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Burke Fellowship from the Harvard Global Health Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (D.S.K) and institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors would like to thank Mr. Nathan Norris, MLS, Senior Information Specialist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts for his technical assistance with implementing the literature search, Mr. Yang Song, PhD, MSc, Director of Research S tatistics at the Smith Center for Outcomes Research, Boston, Massachusetts and Mr. Hibiki Orui, MA, Biostatistician at the Smith Center for Outcomes Research, Boston Massachusetts for their assistance with creating Figure 1.

Contact information and diclosures for authors

| Name | Address + Tel no. + Email | Disclosures | Funding related to this work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kazi | 375 Longwood Ave, 4th Floor Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-632-7699 Fax: 617-632-7698 Email: dkazi@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | Burke Fellowship from the Harvard Global Health Institute Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology |

| Katznelson | 1305 York Ave New York, NY 10021 Phone: 650-387-7118 Email: rpp9004@nyp.org |

None | None |

| Liu | 375 Longwood Ave, 4th Floor Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-632-7699 Fax: 617-632-7698 Email: a126833028@gmail.com |

None | None |

| Al-Roub | 375 Longwood Ave, 4th Floor Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-632-7699 Fax: 617-632-7698 Email: nalroub@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| Chaudhary | 375 Longwood Ave, 4th Floor Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-632-7699 Fax: 617-632-7698 Email: rchaudh2@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| Young | Information Systems - Knowledge Services Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center 185 Pilgrim Road, Baker 101 Boston, MA 02215 Telephone: 617-632-8311 Email: dyoung3@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| McNichol | Information Systems - Knowledge Services Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center 185 Pilgrim Road, Baker 101 Boston, MA 02215 Telephone: 617-632-8311 Email: mmcnich3@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| Mickley | Pierce Hall, 29 Oxford Street Cambridge MA 02138 Phone: 617-496-5635 Fax: 617-495-4551 Email: mickley@fas.harvard.edu |

None | US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grant 83587201 |

| Kramer | 375 Longwood Ave, 4th Floor Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-632-7699 Fax: 617-632-7698 Email: dkramer@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| Cascio | 109 T.W. Alexander Drive MC: 305-01, B-310F Durham, NC 27711 Phone: 919-541-2508 Email: cascio.wayne@epa.gov |

None | None |

| Bernstein | 300 Longwood Ave Boston, MA 02115 Email: aaron_bernstein@hms.harvard.edu |

None | None |

| Rice | Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Ks/Bm23 330 Brookline Ave Boston MA 02215 Phone: 617-667-5864 Email: mrice1@bidmc.harvard.edu |

None | National Institutes of Health Conservation Law Foundation fees for expert testimony |

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

We declare no competing interests.

DISCLAIMER

The research described in this article has been subjected to review by the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Research and Development and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policy of the Agency, nor doesmention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

DATA SHARING

This study relies on published data that are already in the public domain and can be obtained from the primary publications cited in the Appendix. The study protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID Number CRD42022320923).

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, et al. IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Published online In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.What Is Climate Change? United Nations. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature Analysis Team. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP v4). Published online 2021. Accessed April 7, 2021. https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/

- 5.Change NGC. Global Surface Temperature | NASA Global Climate Change. Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Published December 3, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keatinge WR, Coleshaw SR, Easton JC, Cotter F, Mattock MB, Chelliah R. Increased platelet and red cell counts, blood viscosity, and plasma cholesterol levels during heat stress, and mortality from coronary and cerebral thrombosis. Am J Med. 1986;81(5):795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim YH, Park MS, Kim Y, Kim H, Hong YC. Effects of cold and hot temperature on dehydration: a mechanism of cardiovascular burden. Int J Biometeorol. 2015;59(8):1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell ML, Goldberg R, Hogrefe C, et al. Climate change, ambient ozone, and health in 50 US cities. Clim Change. 2007;82(1):61–76. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9166-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bevan GH, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Münzel T, Rajagopalan S. Ambient Air Pollution and Atherosclerosis: Insights Into Dose, Time, and Mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(2):628–637. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US EPA National Center for Environmental Assessment RTPN, Sacks J Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter (Final Report, Dec 2019). Accessed January 5, 2022. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=347534

- 11.Osborne MT, Shin LM, Mehta NN, Pitman RK, Fayad ZA, Tawakol A. Disentangling the Links Between Psychosocial Stress and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(8):e010931. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks CA, Kesselheim AS, Fralick M. The Shortage of Normal Saline in the Wake of Hurricane Maria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):885–886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crimmins A, Balbus J, Gamble JL, et al. USGCRP, 2016: The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC; 2016. Accessed May 27, 2022. https://health2016.globalchange.gov/executive-summary.html [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Biswal S, Rajagopalan S. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(10):656–672. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0371-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazi D, Bernstein A, Rice M, et al. Climate Change and Cardiovascular Health: A Review. PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022320923. Accessed May 9, 2022. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022320923 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodruff TJ, Sutton P, The Navigation Guide Work Group. An Evidence-Based Medicine Methodology To Bridge The Gap Between Clinical And Environmental Health Sciences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(5):931–937. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Varghese BM, Hansen A, et al. Heat exposure and cardiovascular health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(6):e484–e495. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00117-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson PI, Sutton P, Atchley DS, et al. The Navigation Guide—Evidence-Based Medicine Meets Environmental Health: Systematic Review of Human Evidence for PFOA Effects on Fetal Growth. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(10):1028–1039. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Published 2021. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 21.Khatana SAM, Werner RM, Groeneveld PW. Association of Extreme Heat and Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: A County-Level Longitudinal Analysis From 2008 to 2017. Circulation. 2022;146(3):249–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alahmad B, Khraishah H, Royé D, et al. Associations Between Extreme Temperatures and Cardiovascular Cause-Specific Mortality: Results From 27 Countries. Circulation. 2023;147(1):35–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Q, Wang J. The association between consecutive days’ heat wave and cardiovascular disease mortality in Beijing, China. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):223. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4129-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson BG, Bell ML. Weather-related mortality: how heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2009;20(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petoukhov V, Semenov VA. A link between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents. J Geophys Res Atmospheres. 2010;115(D21). doi: 10.1029/2009JD013568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han J, Liu S, Zhang J, et al. The impact of temperature extremes on mortality: a time-series study in Jinan, China. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014741. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Yao Y, Duan Y, et al. Years of life lost and mortality risk attributable to non-optimum temperature in Shenzhen: a time-series study. J Expo Sci Env Epidemiol. 2021;31(1):187–196. doi: 10.1038/s41370-020-0202-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavigne E, Gasparrini A, Wang X, et al. Extreme ambient temperatures and cardiorespiratory emergency room visits: assessing risk by comorbid health conditions in a time series study. Env Health. 2014;13(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1476-069x-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z, Tong S, Pan H, Cheng J. Associations of extreme temperatures with hospitalizations and post-discharge deaths for stroke: What is the role of pre-existing hyperlipidemia? Env Res. 2021;193. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moghadamnia MT, Ardalan A, Mesdaghinia A, Naddafi K, Yekaninejad MS. The Effects of Apparent Temperature on Cardiovascular Mortality Using a Distributed Lag Nonlinear Model Analysis: 2005 to 2014. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2018;30(4):361–368. doi: 10.1177/1010539518768036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Son JY, Gouveia N, Bravo MA, de Freitas CU, Bell ML. The impact of temperature on mortality in a subtropical city: effects of cold, heat, and heat waves in São Paulo, Brazil. Int J Biometeorol. 2016;60(1):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00484-015-1009-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henrotin JB, Zeller M, Lorgis L, Cottin Y, Giroud M, Béjot Y. Evidence of the role of short-term exposure to ozone on ischaemic cerebral and cardiac events: The Dijon Vascular project (DIVA). Heart. 2010;96(24):1990–1996. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.200337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malik AO, Jones PG, Chan PS, Peri-Okonny PA, Hejjaji V, Spertus JA. Association of long-term exposure to particulate matter and ozone with health status and mortality in patients after myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(4). doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):890–895. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen K, Wolf K, Breitner S, et al. Two-way effect modifications of air pollution and air temperature on total natural and cardiovascular mortality in eight European urban areas. Env Int. 2018;116:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi W, Sun Q, Du P, et al. Modification Effects of Temperature on the Ozone-Mortality Relationship: A Nationwide Multicounty Study in China. Env Sci Technol. 2020;54(5):2859–2868. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b05978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen G, Guo Y, Yue X, et al. Mortality risk attributable to wildfire-related PM2·5 pollution: a global time series study in 749 locations. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(9):e579–e587. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00200-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston F, Hanigan I, Henderson S, Morgan G, Bowman D. Extreme air pollution events from bushfires and dust storms and their association with mortality in Sydney, Australia 1994–2007. Env Res. 2011;111(6):811–816. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller Nolan, Molitor David, Zou Eric. Blowing Smoke: Health Impacts of Wildfire Plume Dynamics (Working Paper). Published online 2017. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://nmiller.web.illinois.edu/documents/research/smoke.pdf

- 40.Johnston FH, Purdie S, Jalaludin B, Martin KL, Henderson SB, Morgan GG. Air pollution events from forest fires and emergency department attendances in Sydney, Australia 1996–2007: a case-crossover analysis. Environ Health. 2014;13(1):105. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mott JA, Mannino DM, Alverson CJ, et al. Cardiorespiratory hospitalizations associated with smoke exposure during the 1997, Southeast Asian forest fires. Int J Hyg Env Health. 2005;208(1–2):75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones CG, Rappold AG, Vargo J, et al. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrests and Wildfire-Related Particulate Matter During 2015–2017 California Wildfires. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(8):e014125. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haikerwal A, Akram M, Monaco AD, et al. Impact of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure during wildfires on cardiovascular health outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(7). doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dennekamp M, Straney LD, Erbas B, et al. Forest Fire Smoke Exposures and Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrests in Melbourne, Australia: A Case-Crossover Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(10):959–964. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wettstein ZS, Hoshiko S, Fahimi J, Harrison RJ, Cascio WE, Rappold AG. Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Emergency Department Visits Associated With Wildfire Smoke Exposure in California in 2015. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(8). doi: 10.1161/jaha.117.007492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnston FH, Bailie RS, Pilotto LS, Hanigan IC. Ambient biomass smoke and cardio-respiratory hospital admissions in Darwin, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2007;7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delfino RJ, Brummel S, Wu J, et al. The relationship of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions to the southern California wildfires of 2003. Occup Env Med. 2009;66(3):189–197. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.041376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rappold AG, Stone SL, Vaughen-Batten H, et al. Peat Bog Wildfire Smoke Exposure in Rural North Carolina Is Associated with Cardiopulmonary Emergency Department Visits Assessed through Syndromic Surveillance. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(10):1415–1420. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Resnick A, Woods B, Krapfl H, Toth B. Health outcomes associated with smoke exposure in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the 2011 Wallow fire. J Public Health Manag Pr. 2015;21 Suppl 2:S55–61. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawrence WR, Lin Z, Lipton EA, et al. After the Storm: Short-term and Long-term Health Effects Following Superstorm Sandy among the Elderly. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(1):28–32. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baum A, Barnett ML, Wisnivesky J, Schwartz MD. Association Between a Temporary Reduction in Access to Health Care and Long-term Changes in Hypertension Control Among Veterans After a Natural Disaster. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915111. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cruz-Cano R, Mead EL. Causes of Excess Deaths in Puerto Rico After Hurricane Maria: A Time-Series Estimation. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(7):1050–1052. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S, Kulkarni PA, Rajan M, et al. Hurricane Sandy (New Jersey): Mortality Rates in the Following Month and Quarter. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1304–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lenane Z, Peacock E, Joyce C, et al. Association of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Following Hurricane Katrina With Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events Among Older Adults With Hypertension. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(3):310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edmondson D, Gamboa C, Cohen A, et al. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality and hospitalization among Hurricane Katrina survivors with end-stage renal disease. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e130–137. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishii M, Seki T, Kaikita K, et al. Short-term exposure to desert dust and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in Japan: a time-stratified case-crossover study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(5):455–464. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00601-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X, Cai H, Ren X, et al. Sandstorm weather is a risk factor for mortality in ischemic heart disease patients in the Hexi Corridor, northwestern China. Env Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(27):34099–34106. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09616-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salvador C, Nieto R, Linares C, Díaz J, Alves CA, Gimeno L. Drought effects on specific-cause mortality in Lisbon from 1983 to 2016: Risks assessment by gender and age groups. Sci Total Environ. 2021;751. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berman JD, Ebisu K, Peng RD, Dominici F, Bell ML. Drought and the risk of hospital admissions and mortality in older adults in western USA from 2000 to 2013: a retrospective study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1(1):e17–e25. doi: 10.1016/s2542-5196(17)30002-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Environmental Health Matters Initiative. Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. (Reich A, Ulman A, Berkower, eds.). National Academies Press (US); 2022. Accessed May 9, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576618/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.IPCC, 2022: Summary for Policymakers [Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Tignor M, Alegría A, Craig M, Langsdorf S, Löschke S, Möller V, Okem A (Eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (Eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rappold AG, Reyes J, Pouliot G, Cascio WE, Diaz-Sanchez D. Community Vulnerability to Health Impacts of Wildland Fire Smoke Exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(12):6674–6682. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manangan AP, Uejio CK, Sahat S, et al. Assessing Health Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Guide for Health Departments | U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit Published online June 2021. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://toolkit.climate.gov/tool/assessing-health-vulnerability-climate-change-guide-health-departments [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salas RN. The Climate Crisis and Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(7):589–591. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2000331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.NOAA National Centers for Environmental information. Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series. Published November 2021. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/globe/land_ocean/12/1/1880-2021 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study relies on published data that are already in the public domain and can be obtained from the primary publications cited in the Appendix. The study protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID Number CRD42022320923).