Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this systematic review was to synthesise literature pertaining to patient and family violence (PFV) directed at Intensive Care Unit (ICU) staff.

Design:

Study design was a systematic review. The data was not amenable to meta-analysis.

Data Sources and Review Methods:

Electronic searches of databases were conducted to identify studies between 1 January 2000 and 6 March 2023, limited to literature in English only. Published empirical peer-reviewed literature of any design (qualitative or quantitative) were included. Studies which only described workplace violence outside of ICU, systematic reviews, commentaries, editorials, letters, non-English literature and grey literature were excluded. All studies were appraised for quality and risk of bias using validated tools.

Results:

Eighteen studies were identified: 13 quantitative; 2 qualitative and 3 mixed methodology. Themes included: (i) what is abuse and what do I do about it? (ii) who is at risk? (iii) it is common, but how common? (iv) workplace factors; (v) impact on patient care; (vi) effect on staff; (vii)the importance of the institutional response; and (viii) current or suggested solutions.

Conclusions:

This systematic review demonstrated that PFV in the ICU is neither well-understood nor well-managed due to multiple factors including non-standardised definition of abuse, normalisation, inadequate organisational support and general lack of education of staff and public. This will guide in future research and policy decision making.

Keywords: Aggression, workplace violence, patients, families, ICU, staff

Introduction

Healthcare professionals are exposed to violence 16 times more often than in any other field of employment. 1 Violence is a serious workplace problem especially in public health, and in high-risk areas such as emergency departments, psychiatric wards and intensive care (ICU). 2 To add insult to (real) injury for staff, impetus for change has been thwarted by the 21st century emphasis in healthcare on public relations and customer-centred services at the expense of staff. 3

Workplace violence is defined pragmatically here as an incident where an employee is abused, threatened or assaulted by patients or their relatives or friends, in circumstances arising out of – or in the course of their employment, irrespective of the intent for harm. 4 This includes, but is not limited to physical violence and abuse (e.g., throwing equipment, hitting, kicking, grabbing) and non-physical violence (e.g., shouting and verbal abuse). 5 We note that this definition focuses on patient and family-perpetrated violence (PFV), unlike broader definitions of workplace violence which encompass violence perpetrated by fellow staff.6 –10 In this review we focus on PFV, which we consider a distinct phenomenon with distinct causes and solutions.

While PFV has increasingly received attention with implementation of a range of workplace interventions, these have been focused on nursing home, mental health and emergency departments, 11 with relative neglect of ICU despite its recognition as a high-risk setting. 3 While a systematic review 12 evaluated occupational violence and aggression in both urgent and critical care in rural health settings, it did not address ICU exclusively, thus obfuscating specific needs of the ICU setting.

Much of the research to date has focused on nursing staff, as evidenced by a cross-sectional study (n = 3416) of membership of the New South Wales Nurses and Midwives’ Association, among whom 85% experienced PFV. 13

This review was an attempt to shed light on this occupational hazard and to explore strategies to improve workplace safety. The modified research PICo (Population, Interest, Context) question was: How do we understand aggression displayed by patients and families towards staff in ICU?

The primary objective of this systematic review was to synthesise literature pertaining to patient and family aggression directed at ICU staff.

Methodology

The systematic review followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol 14 and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023434566).

Search strategy

Electronic searches of databases including PubMed, Medline, PsycINFO, Embase and Emcare were conducted using mesh and tree text terms, designed to identify studies between 1 January 2000 and 6 March 2023. In addition to the database searches, other articles were identified from the reference lists of included papers and systematic reviews (see Supplemental File 1.1. for search terms). The search was limited to literature in English only. For literature in languages other than English, we attempted to find an English language version.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

Published empirical peer-reviewed literature were reviewed to identify studies of any design (qualitative or quantitative) which included workplace violence including assault and aggression of ICU staff (including nurses, allied health, doctors, ward persons, administrative officers) by patients and families.

Exclusion

Studies which described workplace violence outside of ICU were excluded unless ICU data was included in the paper. Systematic reviews, commentaries, editorials, letters, non-English literature and grey literature were excluded.

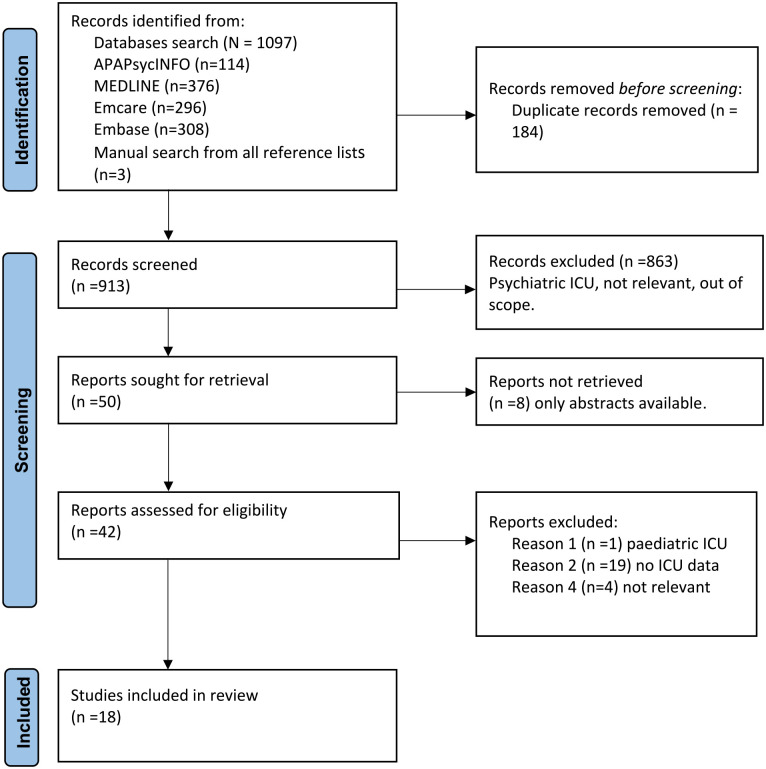

Study screening

Primary database search and manual screening was undertaken by the first author (VS), with subsequent rounds (including full paper screening) by all authors, with disagreement reconciled with consensus of all three authors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Quality assessment

Included articles were independently assessed for quality and bias by authors VS and KL. Differences were resolved by discussion with author CP until consensus reached and final rating determined. Quantitative studies were appraised for quality using Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Standard Quality Assessment Criteria (KMET). 15 The checklist includes study design and appropriateness, method of subject selection, random allocation and blinding, outcome measures, statistical methods (including confounding and estimates of variance) and reporting of results and conclusions. A formula is used to derive a final rating score, expressed as a percentage, with >80% being generally considered as high quality in absence of any validated cut-off scores for quality.16 –18

Qualitative studies were rated using Attree and Milton (2006) checklist 19 inclusive of research aims and objectives, appropriateness of study design, sampling methods, data collection, analysis and results, reflexivity, value and usefulness of the study and ethical considerations. Each item is rated from A (no or few flaws) to D (significant flaws threatening the validity of the entire study), with the final quality score (A–D) determined by the majority grade.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHQR) tool 20 which provides an overall bias rating of high, medium or low, based on the number of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses to each question in the rating tool.

Data extraction and synthesis

A table was created for the extraction of relevant data, including author details, year of study, country of study, characteristics of participants, study design, comparison group, outcome measures, risk of bias and methodological quality and score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data extraction: Included studies.

| Author year country |

Type of study | Aim | Setting/participants | Sample size | Exclusions/comparison | Outcomes | Qualitative rating (Attree & Milton) | Quantitative rating KMET 15 | Bias rating (AHQR) (low, medium, high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May, D.; 2002 USA 21 |

Descriptive, comparative study Quantitative |

To investigate nurse perceptions of the incidence and nature of verbal and physical assault or abuse by patients and their family members or visitors | 770 bedded acute care regional medical centre. Convenience sample of all RNs * employed in ED ** , CVICU *** , medical/surgical ICU, intermediate care unit, CCU **** , general medical/surgical floor, pulmonary speciality floor, diabetes floor, oncology, and cardiac progressive floor | 125 | Neuro ICU, neuro floor, paediatric ICU and floor, OR ***** , and recovery room. Temporarily employed nurses. | Confusion regarding legal definition of assault, rights and policies and procedures | 54.5% | Medium | |

| Lynch, J.; 2003 UK 22 |

Postal survey quantitative |

To ascertain the frequency of abusive and violent behaviour by patients and relatives towards ICU staff, discover perceived causes, effects and documentation of such behaviour and define current and proposed security arrangements for ICUs. | Postal survey to senior nurses of 188 general ICUs in England and Wales | 176 | 77% abuse by patients and 17% by relatives. Illness, distress, alcohol and sociopathic behaviour main causes | 45% | Medium | ||

| Gerberich, S G.; 2004 USA 23 |

Epidemiological study quantitative |

To identify the magnitude of and potential risk factors for violence within a major occupational population | Comprehensive surveys sent to random 6300 Minnesota licensed RNs and practical (LPNs) nurses to collect data on physical and non-physical violence for the prior 12 months | 79,128 | Non-fatal physical assault and non-physical forms of violence is frequent & perpetrated mainly by patients and environmental factors | 86.4% | Low |

Registered Nurse; **Emergency department; ***Cardiovascular intensive care unit; ****Coronary care unit; *****Operating room.

| Author Year Country |

Type of study | Aim | Setting/participants | Sample size | Exclusions/comparison | Outcomes | Qualitative rating (Attree & Milton) | Quantitative rating (KMET) | Bias rating (AHQR) (low, medium, high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed, A S.; 2012 Jordan 24 |

Descriptive cross-sectional study quantitative |

To determine the prevalence and sources of verbal and physical workplace abuse in the last 6 months, the nurse’s reactions to abuse, and their opinions about it | Questionnaire sent to 500 random nurses in 3 hospitals | 500 447 responses |

Low reporting of violence -decrease in quality of work Poor support from hospital |

68.2% | Medium | ||

| Fujita, S.; 2012 Japan 25 |

Questionnaire-based anonymous, self-administered cross-sectional survey, quantitative |

To investigate incidences of workplace violence and the attributes of healthcare staff who are at high risk | Healthcare staff of 19 hospitals in Japan | 11,095 | Adjusted odds ratio- high for ICU, high for verbal abuse, for long hours of work, seniority of staff and for sexual harassment | 77% | Medium | ||

| Unsal Atan, S., et al 2013 Turkey 26 |

Descriptive cross-sectional quantitative |

To study the rate of nurses’ experience of WPV * at 6 university hospital’s emergency departments, psychiatric clinics and intensive care units in Turkey. | No sampling used. Attempt made to reach all nurses in the study population | 720 658 invited 441 accepted |

Nurses who were on leave or had a health report during the research or those who did not agree to participate were not included | >60% nurses subject to violence which impacted nurse’s health and work performance | 54.5% | Medium | |

| Park, M.; 2015 South Korea 27 |

Cross-sectional | To identify prevalence and perpetrator of workplace violence against nurses and to examine the relationship of work demands and trust and justice in workplace with occurrence of violence | 970 female nurses from 47 nursing units at a university hospital in Seoul | 970 | Male nurses (n = 38) and psychiatric unit nurses (n = 13) were excluded | Varied prevalence of violence perpetrators across nursing units. Increased work demands and reduced trust and justice were associated with experience of violence |

77.3% | medium |

Workplace violence.

| Author Year Country |

Type of study | Aim | Setting/participants | Sample size | Exclusions/comparison | Outcomes | Qualitative rating (Attree & Milton) | Quantitative rating (KMET) | Bias rating (AHQR) (low, medium, high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shafran-Tikva, S.; 2017 Israel 28 |

Quantitative study | To examine different types of violence experienced by nurses and physicians, types of perpetrator and specialty fields involved | 729 physicians and nurses in a variety of hospital division and departments in a large general hospital | 678 responded 446 nurses and 232 physicians | Age, seniority had positive association with exposure to violence. Need for uniform standardised definitions of violent behaviours. | 86.4% | Low | ||

| Yoo, H J 2018 South Korea 29 |

Mixed | To identify intensive care nurse’s experience of violence from patients and families and investigate their coping methods, if any, in a tertiary hospital in South Korea | 200 | Included only female nurses. Males were excluded | Verbal violence more than physical violence.4 themes – perception of violence, coping with violence experience, coping resource & caring mind after experience. Moderate to severe response to violence based on scores. |

B | 77.3% | Medium | |

| Lal Gautam, P.; 2019 India 30 |

Questionnaire based cross-sectional, mixed |

To evaluate perceptions of healthcare workers(HCW) and patients’ attendants about factors responsible for widespread violence and patient-physician distrust | Conducted in medical, surgical, neurosurgery ICUs of a tertiary teaching Institute. Anonymous, questionnaire-based cross-sectional study conducted over a period of 1 year from Aug.2017-July 2018. | HCW 295 Attendants 142 |

142 responses from attendees of patients were also sought | Violence from patient’s attendants was common resulting in stressful and fearful environment at the healthcare facility. | B | 68.2% | Medium |

| Pol, A.; 2019 Australia 31 |

Retrospective pre and post study | To determine incidence of aggressive and violent behaviours, and determine the healthcare professionals most at risk of being subjected to occupational violence in this setting | A before and after retrospective review of medical records over a 24-month period to evaluate impact of NEAT * on aggressive or violent behaviours, conducted in a 45-bed adult ICU at metropolitan tertiary hospital in Victoria | Before = 18, After = 29 |

Increase in number of code black/grey (emergency codes) post intervention. Male nurses more likely to be involved in incidences of verbal violence |

68.2% | Medium | ||

| Sunil Kumar, N.; 2019 India 32 |

Pretested, self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire-based survey | To draw attention towards the issue of violence against critical care physicians, reveal dimensions of such violence and highlight ill effects of WPV on personal life of doctors | Survey conducted among critical care physicians attending a critical care conference |

N = 160, 118 responses |

Improving communication skills for conflict management. ‘Fight against disease and not doctor’ |

40.9% | Medium | ||

| Cho, H.; 2020 USA 33 |

Cross-sectional secondary data analysis study | To examine differences in early-career nurses’ verbal abuse experience based on their socio-demographic characteristics, and to investigate associations of verbal abuse experience with nurse-reported care quality and patient safety outcomes | Using state RN licensure lists, RNs were randomly sampled using nested design in 20 metropolitan statistical areas and 1 rural county in 14 states across the country | 799 | 88 RN who had not been employed in nursing job that required RN licence, 208 nurses who worked in settings other than a hospital and 63 nurses who were not employed full time and 21 nurses who were not providing direct care were excluded. | Male nurses experience more verbal abuse. Step-down units and general wards experience more abuse than ICU and other units |

77.27% | Medium |

National emergency access target.

| Author Year Country |

Type of study | Aim | Setting/participants | Sample size | Exclusions/comparison | Outcomes | Qualitative rating (Attree & Milton) | Quantitative rating (KMET) | Bias rating (AHQR) (low, medium, high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dafny, H. A.; 2020 Australia 34 |

Exploratory, qualitative study | To examine nurses’ perceptions of physical and verbal violence perpetrated by patients and visitors and to investigate themes surrounding gender and the incidence of violence | Focus group interviews with 23 nurses from ED, ICU and Psychiatry Departments working in Queensland regional public hospital, Australia. | 23 | Violence increasing. Burden of Accepting as part of job. Difficult bureaucratic processes. |

B | Medium | ||

| Yi, X.; 2022 China 35 |

Questionnaire based cross-sectional survey | To explore current status and influencing factors of workplace violence to medical staff in ICU | 230 medical staff in ICU of Hengyang City were selected, from Oct. 2021 to Jan. 2022 | 230 | Interns, on leave for >3 months for maternity, staff in neonatal ICU, those who worked <1 year in ICU were excluded | Incidence 40%. Main reason is verbal miscommunication. Main coping style was patient explanation. Work experience and working hours independent high-risk factors. |

81.8% | Medium | |

| Alquwez, N. 2023 Saudi Arabia 36 |

Cross-sectional study | Examine the association between workplace incivility experience of nurses and patient safety culture in hospital. | Survey of 261 nurses in Saudi Arabia from June 2019 to August 2019 using ‘Hospital Survey of patients’ safety Culture’ and ‘Nurse Incivility Scale’ in 2 tertiary-level acute care facilities in Riyadh | 261 | Most incivility by patients and visitors. High in ICU | 90.9% | Low | ||

| Parke, R., et al 2023 ANZ 37 |

Prospective cross-sectional online survey | To determine self-reported occurrence of bullying, discrimination, and sexual harassment among ICU nurses in Australia and NZ | Nurses working in or nurses who had worked in ICUs in ANZ in the preceding 12 months. Undertaken in May-June 2021 |

679 | Bullying 57.1% Discrimination 32.6% Sexual harassment 1.9%. (mainly by patients) 66% non-respondents. True extent difficult to estimate. |

B | 81.8% | Medium | |

| Patterson, S., et al 2023 Australia 38 |

Qualitative descriptive study | To describe and reflect upon aggression towards staff in ICU from the perspective of staff members. | Data collected from semi-structured interviews of 19 staff members of 10-bed ICU in Queensland | 19 | Perceived knowledge and skill deficit along with stigma of engaging with certain subpopulations contributes to WPV in ICU. | A | Medium |

We used the method of thematic synthesis. VS undertook primary open coding of included texts (Results and Discussion). Subsequent development of descriptive themes, followed by consolidation and interpretation to generate analytical themes was undertaken by all three authors. 39

Statistician input was sought for feasibility of meta-analysis.

Results

This literature review included 18 studies: four from USA, three from Australia; two each from India, South Korea; and one each from China, Jordan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Japan, UK and Israel; with one combined study from Australia and New Zealand. Of the studies included, 13 were quantitative, 2 were qualitative and the remaining 3 mixed-method studies.

Of 18 included studies, 10 focused on nurses at various stages of their careers,21,23,24,26,27,29,33,34,36,37 7 on a range of workers including nurses, doctors and other hospital employees22,25,28,30,31,35 with one dedicated to doctors. 32 Only 7 studies focused only on ICU22,29,31,32,35,37,38 with the remaining 11 studies included various units in the hospital including ICU.21,23 –28,30,33,34,36

Of 18 studies included, 5 were rated high quality16,17,18 (>80%) using KMET quantitative rating; 7 scored between 60–80%, 4 studies between 40–60%. The three qualitative studies scored between A and B on Attree and Milton qualitative ratings. 19

Thematic synthesis yielded a number of themes which included:

What is abuse and what do I do about it?

The studies identified showed a lack of understanding, identification and recognition of PFV which was normalised or considered part of job.29,34,37,38 Several studies reported lack of standardised definition of what constitutes PFV, which can include ‘being kicked’, ‘pinched’, ‘spat upon’, ‘cursed at’, ‘yelled at’, ‘threatened with harm’ to ‘swearing’, ‘reviling’, ‘punching’, ‘scratching’, ‘throwing an object’.21,24,26,28,29 Similarly, studies showed poor understanding of legal implications of PFV including the differences between ‘assault’ and ‘abuse’, and reporting policies and procedures.21,26,37

It is common, but how common?

Determining the prevalence of PFV is constrained by this lack of definition. Studies suggested that verbal abuse was the most common form (50–90%) of aggression.21,22,24,26 –30,32,33 Main perpetrators were male patients followed by visitors or carers.23,24,35

Who is at risk?

ICU nurses, who work around-the-clock at patient bedsides, experience more PFV. 28 Several studies suggested the prototype victim of PFV was a female nurse,14,15,19,22 –26,28,30,33 with proposed reasons including maternalistic attitudes towards patients,22,24,28 and the gender bias for sexual harassment.21,22,24,28,38 In contrast, one paper suggested that male nurses experienced more PFV because they were perceived as bodyguards. 34

Three studies28,33,35 reported an association between seniority and experience of PFV, although the reasons for this are unclear. On the one hand there was a positive association between doctors’ rank and exposure to PFV; yet being older reduced risk for both doctors and nurses. 28

Patient factors

ICU is an area which provides high quality care for very sick patients, and uncertainty of recovery adds to stress of families and staff equally but for different reasons. Notably, with regards to potential sources of family stress, staff perceived that patients with unexplained conditions, poor prognosis, extended hospital stays, unexpected complications and unexpected deaths were responsible for aggression. 30 Admission from ED to ICU with a variety of diagnoses and acuity of illness was also associated with more aggression. 31 Patient mix, specifically absence of adult male patients influenced PFV. 25 While staff (nursing staff) perceive causes of patient violence to be related to ‘distress’ ‘alcohol or illegal drugs’ ‘psychiatric illness’ and ‘sociopathic personality’, 22 no studies reported psychiatric assessments or diagnoses of aggressive patients.

Workplace factors

A range of workplace factors appeared to be related to PFV. PFV occurred most frequently on night shifts 30 and in settings with higher work demands (workload), staff (nursing) shortages, higher hospital costs24,30,37 leading to higher levels of stress for the families, and public, metropolitan and level 3 ICUs. 37 Workplace practices including longer working hours, constant and direct interaction with patients, posed risks for all types of aggression including physical aggression, verbal abuse and sexual harassment. 25 Lack of staff training causing skill and knowledge deficits was also evident with staff reporting feeling ill-prepared to work with aggressive patients, whose management they relegated to mental health services. 38

Impact on patient care

This was minimally studied. One study found that PFV was significantly associated with negative perceptions of unit-level patient safety 36 ; another study reported that junior nurses who experience verbal abuse are less likely to report high-quality care and favourable safety ratings. 33

Effect on staff

Negative impacts of PFV on staff wellbeing and work productivity and quality were wide-ranging. Psychological effects ranged from psychological and somatic symptoms to frank mental health disorders such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Depression with impact on family life and social life.23,24,26 Occupational effects included increased sick leave, decreased job satisfaction, consideration of quitting the profession and attrition of staff.24,26

The importance of the institutional response

Inadequate support from management was noted in 9 of 18 studies identified.22,26,29,30,31,33,34,37,38 PFV in the ICU had a significant effect on perception of employer or organisation with effects of inaction including distrust 34 and an expressed need for legislation to tackle PFV. 32 There was strong agreement among studies that more concerted efforts from organisations was required to work towards employee satisfaction, increased public awareness and upskilling and supporting staff in dealing with PFV.24,26,29,30,32,34 There was perception of overemphasis on the institution and patient rights over that of employees. 21

Current or suggested solutions

Many remedies were proposed including education of staff and general public, improved reporting of incidences, better security, Code Black teams (emergency response team for aggressive behaviour), restricted access to the ICU for visitors.21,29,30,31,32,33,36 ‘Zero Tolerance Policy’, ‘Hospital Protection Act 2008’ and Doctor’s Protection Act 2010 in India were legislative solutions.30,32

Discussion

In this systematic review we synthesised the available literature on aggression displayed by patients and families towards staff in the ICU. As far as we are aware, this is the only systematic review on this topic. The representation of studies across the USA, Australia, South Korea India, China, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel and UK suggests that this is global problem not limited to certain cultural settings, although in the absence of cross-cultural studies, we do not know how culture influences either manifestations of aggression or solutions. The quality and bias ratings, paucity of studies on crucial issues such as patient diagnoses contributing to aggression, and the impact of PFV on patient care, and general lack of amenability of the data to meta-analysis suggests that this is an under-researched topic. Notwithstanding this, the richest source of data lay in the qualitative studies. Our thematic synthesis yielded a number of observations, many of which posed further questions. These included: (i) what is abuse and what do I do about it? (ii) who is at risk? (iii) it is common, but how common? (iv) workplace factors;(v) impact on patient care (vi) effect on staff; (vii) the importance of the institutional response; and (viii) current or suggested solutions.

One of the most troubling observations is that this global problem in healthcare is common, but its proper documentation remains elusive. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Attacks on Health Care Intiative 2019–2022, of 594 reported attacks on healthcare workers resulting in 959 deaths and 1561 injuries in 19 countries, 62% intentionally targeted healthcare.40,41 While this may be a global problem, it is a problem undefined, and therefore unstudied and unsolved. Lack of international consensus of definition of PFV, in both legal and clinical contexts provides an impediment to both reporting and data collection, as well as remedy in raising staff awareness and garnering adequate systemic responses including prosecutions where appropriate. Future research might be directed to international collaboration on recognising and tackling PFV, with first steps being a consensual definition of PFV to improve epidemiological understanding of PFV. What is also needed is collaboration with our legal colleagues, starting with a review of prosecutions in this space.

While the literature shows tentative links between PFV and patient safety and quality, there is no doubt about effects on staff welfare and productivity. Echoed in other more general studies of workplace violence in healthcare settings, failure to address the problem has consequences both for staff in terms of psychological and physical harm, but also for the facility, mediated by job satisfaction, job commitment, sick leave, staff turnover, and associated economic costs. 42 The Price-Muller Turnover Model 43 indicates that organisational commitment has a mediating effect on relationship between job burnout and turnover intention, with higher burnout scores associated with stronger turnover intention.44 –46

We have identified a number of putative risk factors for PFV that warrant further empirical investigation of odds ratios for aggression, in order to inform prevention strategies. It was found that nursing occupation, female gender, junior ranking, long-working hours were potential risk factors for PFV. The main perpetrators were male patients followed by visitors or carers. Patient complexity and poor prognostic factors that likely fuel family stress and accordingly aggression, are likely important but need further examination. Moreover, better understanding of patient variables such as delirium and psychiatric diagnoses is also required. Further to the issue of international consensus, collaboration and data gathering, a potential model for taking this area of research forward can be found in the Sprint National Anaesthesia Projects (SNAPs) conducted not only in the UK, but in Australia and New Zealand. Although craft-specific, the SNAPs capture data related to commonly occurring phenomena over a few days, then analyse and report on the data in peer-reviewed papers in clinical journals. 47

It was generally found that there was a lack of institutional support or policies dealing with PFV. Or even if these were in place, they were either unknown or difficult to navigate. Organisations need to consider their health and safety obligations and duty of care to staff in this context of harm and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, 48 with particular attention to the workplace factors that either promote or mitigate against risk for PFV, including policies such as family access and visitation policy 49 and unit size and design ensuring visibility of care and emergency exits. 50 These systemic changes needed to be echoed by political will for change including legislation enforcing both remedy and penalty.51 –53

A range of targets for staff training have been identified here and elsewhere. These include staff training on topics such as patient and family communication skills, trauma-informed care, de-escalation skills and resilience training.54 –57 Although identified in emergency departments, but of equal relevance here, is the need for accessible experiential training in de-escalation.58 –60 Further to education and support, collaboration between ICU and mental health utilising novel initiatives such as a liaison-psychiatrist embedded within the ICU 61 might be pursued.

We summarise the solutions proposed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Synthesis of proposed solutions to PFV.

| Proposed solutions |

|---|

| International taskforce and consensus group on PFV in healthcare |

| Systemic organisational commitment to zero tolerance policy and staff support |

| Mandatory data gathering and reporting |

| Staff awareness raising including Red Flag/Risk Factor Warning signs |

| Mandatory staff training in communication and de-escalation |

| Embedded consultation-liaison psychiatrist within ICU |

Limitations

As with any systematic review, there is inherent limitation in terms of missed literature due to exclusion of grey literature, non-English literature, editorials and letters. Further, subsequent to completion of the review, relevant studies meeting eligibility criteria may have been missed. Another factor effecting the quality of the systematic review is the quality of the included studies, with highest quality found in qualitative studies, with quantitative not amenable to meta-analysis. Consistent quantitative data across several studies was lacking. For example, assault incidence was mostly reported as anecdotal survey data only, with quantified assault rates – for example, assaults per bed per day – insufficiently reported for meta-analysis. We considered requesting a measured assault rate from study authors for meta-analysis purposes but acknowledge that data was unlikely to be available to them without information on the rostering of each survey respondent. Rather, richness of data lay with the qualitative perceptions and experiences of healthcare professionals. As such, this study focused on a thematic synthesis of the literature.

Conclusion

This systematic review included 18 articles that met eligibility criteria out of a potential 1097 identified from searches. It appears that PFV is commonly encountered by ICU staff particularly nursing staff, but otherwise we know very little about its epidemiology and risk. Although the past decade has seen a shift towards addressing this widespread occupational hazard, it has neither been sufficient nor effective in addressing occupational safety. Given the normalisation by staff that FPV is part of the job, perhaps a starting point from the organisation down is to say it is not part of the job, and to echo a zero-tolerance policy, internationally.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inc-10.1177_17511437241231707 for Understanding aggression displayed by patients and families towards intensive care staff: A systematic review by Varadaraj Sridharan, Kelvin CY Leung and Carmelle Peisah in Journal of the Intensive Care Society

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Tracy McDonald and Ms. Claire Ambrose, Librarians at Cumberland Hospital, Westmead for their immense help in sourcing the articles, education with use of Endnote, OVID search engine and for being available at short notices to address the most trivial of queries; and James Elhindi – statistician at Research and Education Network, Westmead Hospital for providing input on feasibility of a meta-analysis.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Varadaraj Sridharan  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0956-632X

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0956-632X

Kelvin CY Leung  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7669-3147

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7669-3147

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Elliott PP. Violence in health care. What nurse managers need to know. Nurs Manag 1997; 28: 38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hahn S, Müller M, Hantikainen V, et al. Risk factors associated with patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: results of a multiple regression analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50: 374–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey RL, Ramanan M, Litton E, et al. Staff perceptions of family access and visitation policies in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: the WELCOME-ICU survey. Aust Crit Care 2022; 35: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Queensland Health. Occupational violence prevention in Queensland Health’s hospital and health services: Taskforce report. 31 May 2016. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/443265/occupational-violence-may2016.pdf (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 5. Speroni KG, Fitch T, Dawson E, et al. Incidence and cost of nurse workplace violence perpetrated by hospital patients or patient visitors. J Emerg Nurs 2014; 40: 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fair Work Ombudsman. Fair Work Ombudsman website, Australian Government. Available at: https://www.fairwork.gov.au (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 7. Australian Human Rights Commission, Australian Human Rights Commission website, Australian Government. Available at: https://www.humanrights.gov.au (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 8. Legal Services Commission South Australia. Legal Services Commission South Australia website, South Australian Government. Available at: https://www.lawhandbook.sa.gov.au (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 9. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. U.S. Department of Labour, Government of U.S.A. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/workplace-violence (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 10. Safe Work Australia. Safe Work Australia website, Australian Government. Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au (accessed 6 March 2024).

- 11. Spelten E, van Vuuren J, O’Meara P, et al. Workplace violence against emergency health care workers: what strategies do workers use? BMC Emerg Med 2022; 22: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grant SL, Hartanto S, Sivasubramaniam D, et al. Occupational violence and aggression in urgent and critical care in rural health service settings: A systematic review of mixed studies. Health Soc Care Community 2022; 30: e3696–e715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pich J, Roche M. Violence on the job: the experiences of nurses and midwives with violence from patients and their friends and relatives. Healthcare 2020; 522: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kmet L, Lee R. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields AHFMRHTA Initiative20040213. HTA Initiative, 2004: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee L, Packer TL, Tang SH, et al. Self-management education programs for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Australas J Ageing 2008; 27: 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee SY, Fisher J, Wand APF, et al. Developing delirium best practice: a systematic review of education interventions for healthcare professionals working in inpatient settings. Eur Geriatr Med 2020; 11: 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wand AP, Browne R, Jessop T, et al. A systematic review of evidence-based aftercare for older adults following self-harm. Aust N Z J Psychiatr 2022; 56: 1398–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Attree P, Milton B. Critically appraising qualitative research for systematic reviews: defusing the methodological cluster bombs. Evid Policy 2006; 2: 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viswanathan M, Patnode CD, Berkman ND, et al. Recommendations for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health-care interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 97: 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. May DD, Grubbs LM. The extent, nature, and precipitating factors of nurse assault among three groups of registered nurses in a regional medical center. J Emerg Nurs 2002; 28: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lynch J, Appelboam R, McQuillan PJ. Survey of abuse and violence by patients and relatives towards intensive care staff. Anaesthesia 2003; 58: 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gerberich SG, Church TR, McGovern PM, et al. An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occup Environ Med 2004; 61: 495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahmed AS. 318 verbal and physical abuse against Jordanian nurses in the work environment. East Mediterr Health J 2012; 18: 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujita S, Ito S, Seto K, et al. Risk factors of workplace violence at hospitals in Japan. J Hosp Med 2012; 7: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ünsal Atan S, Baysan Arabaci L, Sirin A, et al. Violence experienced by nurses at six university hospitals in Turkey. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2013; 20: 882–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park M, Cho S-H, Hong H-J. Prevalence and perpetrators of workplace violence by nursing unit and the relationship between violence and the perceived work environment. Journal of nursing scholarship 2015; 47: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shafran-Tikva S, Zelker R, Stern Z, et al. Workplace violence in a tertiary care Israeli hospital - a systematic analysis of the types of violence, the perpetrators and hospital departments. Isr J Health Policy Res 2017; 6: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoo HJ, Suh EE, Lee SH, et al. Experience of violence from the clients and coping methods among ICU nurses working a hospital in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res 2018; S1976–1317(17)30673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lal Gautam P, Sharma S, Kaur A, et al. Questionnaire-based evaluation of factors leading to patient-physician distrust and violence against healthcare workers. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019; 23: 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pol A, Carter M, Bouchoucha S. Violence and aggression in the intensive care unit: What is the impact of Australian National Emergency Access Target? Aust Crit Care 2019; 32: 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar NS, Munta K, Kumar JR, et al. A survey on workplace violence experienced by critical care physicians. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019; 23: 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cho H, Pavek K, Steege L. Workplace verbal abuse, nurse-reported quality of care and patient safety outcomes among early-career hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag 2020; 28: 1250–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dafny HA, Beccaria G. I do not even tell my partner: Nurses’ perceptions of verbal and physical violence against nurses working in a regional hospital. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 3336–3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yi X, Feng X. Study on the current status and influencing factors of workplace violence to medical staff in Intensive Care Units. Emerg Med Int 2022; 2022: 1792035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36. Alquwez N. Association between nurses’ experiences of workplace incivility and the culture of safety of hospitals: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs 2023; 32: 320–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parke R, Bates S, Carey M, et al. Bullying, discrimination, and sexual harassment among intensive care unit nurses in Australia and New Zealand: an online survey. Aust Crit Care 2023; 36: 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patterson S, Flaws D, Latu J, et al. Patient aggression in intensive care: a qualitative study of staff experiences. Aust Crit Care 2023; 36: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. WHO. Attacks on Heath Care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41. WHO. Attacks on Health Care Initiative 2019-2022. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lepiešová M, Tomagová M, Bóriková I, et al. Experience of nurses with in-patient aggression in the Slovak Republic. Cent Eur J Nurs Midwifery 2015; 6: 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Price JL. Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. Int J Manpow 2001; 22: 600–624. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gharakhani D, Zaferanchi A. The effect of job burnout on turnover intention with regard to the mediating role of job satisfaction. J Health Law 2019; 10: 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee YH, Chelladurai P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, coach burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in sport leadership. Eur Sport Manag Q 2018; 18: 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang T, Abrantes ACM, Liu Y. Intensive care units nurses’ burnout, organizational commitment, turnover intention and hospital workplace violence: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Open 2023; 10: 1102–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Royal College of Anaesthetists Sprint National Anaesthesia Projects (SNAPs). Available at: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/research/research-projects/sprint-national-anaesthesia-projects-snaps (accessed 1 December 2023).

- 48. Kozarov v Victoria [2022] HCA 12 (13 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bailey RL, Ramanan M, Litton E, et al. Staff perceptions of family access and visitation policies in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: the WELCOME-ICU survey. Aust Crit Care 2022; 35: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Keys Y, Stichler JF. Safety and security concerns of nurses working in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Crit Care Nurs Q 2018; 41: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sethi A, Laha G, Shringarpure K. Comparative analysis of various prevention of violence against doctors state acts in India-a descriptive study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2021; 25: S52–S53. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shukla S. Violence against doctors in Egypt leads to strike action. Lancet 2012; 380: 1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hu X, Xu J, Wang K, et al. The study on risk factors for severity of physical violence against the medical staff in China. Biomed Res 2017; 28: 7960–7971. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boudreaux A. Keeping your cool with difficult family members. Nursing 2010; 40: 48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sona C, Taylor B, Prentice D, et al. 1186: workplace violence pilot study: response Algorithms and other measures for staff safety. Crit Care Med 2022; 50: 592–592. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, et al. Workplace violence against nurses–prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 56: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wood A, Achary C, Pennington J, et al. Risk assessing and managing aggression and violence in mental health patients in a tertiary intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Soc 2019; 20: 240. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Davids J, Murphy M, Moore N, et al. Exploring staff experiences: a case for redesigning the response to aggression and violence in the emergency department. Int Emerg Nurs 2021; 57: 101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moore N, Ahmadpour N, Brown M, et al. Designing virtual reality experiences to supplement clinician Code Black education. Int J Heal Simul 2022; 1: S12–S14. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moore N, Ahmadpour N, Brown M, et al. Designing virtual reality-based conversational agents to train clinicians in verbal de-escalation skills: exploratory usability study. JMIR Serious Games 2022; 10: e38669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peisah C, Goh D. A liaison psychiatrist attached to an intensive care unit: why such a rare creature? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2020; 54: 1040–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inc-10.1177_17511437241231707 for Understanding aggression displayed by patients and families towards intensive care staff: A systematic review by Varadaraj Sridharan, Kelvin CY Leung and Carmelle Peisah in Journal of the Intensive Care Society