Abstract

Objective:

Learning health care networks can significantly improve the effectiveness, consistency, and cost-effectiveness of care delivery. As part of the data harmonization process, it is critical to incorporate the perspectives of community partners to maximize the relevance and utility of the data.

Methods:

A mixed method focus group study was conducted with early psychosis (EP) program providers, leadership, service-users, and family members to explore their data collection priorities regarding EP care. Focus group transcripts were analyzed utilizing thematic analysis.

Results:

22 focus groups including 178 participants were completed across 10 EP programs. Participants considered functioning, quality of life, recovery, and symptoms of psychosis as key outcomes to assess, although variation by role was also evident. Participants emphasized the clinical utility of assessing a broad range of predictors of outcomes, wanted a broad conceptualization of the constructs assessed, and indicated a preference for client-report measures. Participants also emphasized the importance of surveys adopting a recovery-oriented, strengths-based approach.

Conclusions:

Large-scale aggregation of health care data collected as part of routine care offers remarkable opportunities for research. This ongoing collection of data can also have a positive impact on care delivery and quality improvement activities. However, these benefits are contingent on the data being both relevant and accessible to those that deliver and receive such care. This study highlights an approach that can significantly inform the development of core assessment batteries used, optimizing the utility of such data for all community partners.

Introduction

Learning health care networks (LHCNs) aim to increase the reliability, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of healthcare delivery (1). Central to LHCNs is data collected through routine care delivery that can lead to innovation and improved outcomes (2, 3). One recent example is the Early Psychosis Intervention Network (EPINET), including over 100 early psychosis (EP) clinics linked through eight regional US hubs (4).

An Important component of LHCN development includes data collection harmonization across clinic sites. The development of clinical trial Core Assessment Batteries (CABs) typically incorporate community partner perspectives (5). This is important, given service-users and family members frequently have different outcome priorities to clinicians and researchers (6, 7). In the LHCN paradigm, community partner perspectives on battery development could be considered even more critical. In clinical trial CABs, the focus is developing a consensus on what instruments are used to measure a therapeutic effect (8). In LHCNs, priorities extend to how data collection can be integrated into clinics to facilitate measurement-based care and quality improvement (4). Recognizing the importance of community partner involvement, the National Academy of Medicine define patients and family involvement as a core feature of a LHCN (1).

There are numerous benefits of data collection in behavioral healthcare (9). This includes supporting service improvement through benchmarking (10), identifying undetected client symptoms or needs, quantifying symptom trajectories, improving patient-provider communication (11–13), and improving quality of life (14). However, benefits are contingent on ensuring the data collected are relevant to clinic leadership, providers, clients, and family members involved in service improvement and the delivery or receipt of care.

In the EPINET development phase, a steering committee of clinical and research experts from the hubs and coordinating center developed the EPINET CAB (15). the California hub – EPI-CAL – conducted a focus group study with EPI-CAL EP clinical providers, county leadership, service-users, and family members to explore their perspectives around what data would be most useful to collect as part of routine EP care. The purpose of was to determine what data domains different community partners wanted captured; how domains should be conceptualized, operationalized, and collected; and what the utility of the data could be to service delivery, evaluation, and research. These data were used to develop the EPI-CAL-specific assessment battery, with findings also fed back to the EPINET CAB Steering Committee to support decision-making regarding the development of the EPINET CAB.

Methods:

Study Design

A mixed method focus group study was completed to explore community partner priorities for what data should be collected in the EPI-CAL CAB.

Participants

Participants included local mental health department staff, EP clinic leadership, providers, service-users, and family members from 10 participating EPI-CAL clinics. Providers were categorized by their self-identified role (see definitions in Supplemental Materials). Focus groups were delivered in English or Spanish. Participants were required to have sufficient proficiency in either language to participate in a group discussion, determined via self-report. Family members were defined as any person who performed an active role in the clients’ care. No additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were adopted beyond each clinics’ eligibility criteria, included in the Supplemental Materials.

Procedures

Focus group guides were developed for provider, and client and family groups (see Supplemental Materials). For the Spanish-speaking groups, all study documents were translated by a bilingual research team member, reviewed, and back translated by UC Davis medical interpretive services. All procedures were approved by the UC Davis IRB (Protocol 1403828) and individual county boards, as necessary. Prior to each group, participants provided consent, or assent with parental consent.

Quantitative Data Collection Procedures

During the focus groups, participants were presented with a provisional list of 15 domain areas with proposed definitions and measures, selected from the Early Psychosis PhenX toolkit (16). Measures of proposed domains were provided for participants’ review. Participants were invited to propose additional domains, review terms and definitions, and then vote for the four domains they considered most important. Following the group discussion, participants completed a second vote as a record of participant priorities.

Qualitative Data Collection Procedures

Facilitators led an open discussion on what aspects of each domain were important to capture, why, and how data should be collected, starting with domains the participants voted for as most important. The discussion was framed around reviewing measures that were being considered for the EPI-CAL CAB. When saturation was reached for the top-voted domains, the facilitators invited groups to discuss the less frequently voted for domains to understand why these were not typically voted for.

Groups lasted 90 minutes and were audio recorded and transcribed using rev.com. For Spanish focus groups, recordings were transcribed and translated by a vendor, Hazletree. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to focus groups being held via teleconference.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to explore participant demographics and review voting patterns. Transcripts were analyzed utilizing thematic analysis (17). Following familiarization with the data, the coding team (KN, LB, MS, SE, VT) developed a preliminary codebook. A positionality statement from each coder and lead facilitator is included in the Supplemental Materials.

The preliminary coding framework was refined following a process of multiple coding (18). First, the coding team coded two transcripts as a team, after which the team was deemed sufficiently concordant to code transcripts separately. Next, the coding team met 1) in alternating dyads to review coding after each transcript to minimize risk of siloing and support reflexivity (19) and 2) weekly as a team to resolve discrepancies and update the coding framework, as necessary. All transcripts were coded using NVivo 12 (20). The coding framework was then developed by MS, LB and reviewed by the coding team before being finalized.

Results

Focus Group and Participant Demographics

Twenty-two focus groups (20 in English, two in Spanish) were completed between 10/08/2019 and 8/31/2020, including 178 participants. Group and participant-level demographics are presented in Table 1. Group sizes ranged from two to 18 participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the focus group sites, types, and participants

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sites Included in Current Analysis (n = 10, n %) |

||

| University | 4 | 40.0% |

| Community | 5 | 50.0% |

| Both | 1 | 10.0% |

| Group Type (n = 22, n %) | ||

| Provider | 10 | 45.5% |

| Service-user | 5 | 22.7% |

| Family member | 7 | 31.8% |

| Group Format (n = 22, n%) | ||

| In-person group | 17 | 77.3% |

| Remote teleconference | 5 | 22.7% |

| Participants (N = 178, n %) | ||

| Provider | 108 | 60.7% |

| Service-user | 34 | 19.1% |

| Family member | 36 | 20.2% |

| Provider Roles (n = 108, n %) | ||

| Clinicians | 37 | 34.3% |

| Administrators | 13 | 12.0% |

| Prescribers | 11 | 10.2% |

| Clinical supervisors / Team lead | 25 | 23.1% |

| Senior leadership | 4 | 3.7% |

| Other (SEES, Peers, Family advocates) | 17 | 15.7% |

| Missing | 1 | 0.9% |

Quantitative Findings

Participant voting patterns post-discussion are presented in Figure 1. Functioning was identified as the most important domain. Other domains with a high proportion of votes included quality of life, recovery, family functioning, and psychiatric symptoms. Clinical status, homelessness risk, incarceration/recidivism, service satisfaction, and impact of medication received the fewest votes. Trauma, substance use, and details regarding culture were proposed for inclusion. Some variability by role was evident. Prescribers prioritized psychiatric symptoms, functioning, and medication utilization. Senior leadership considered risk to self and others and family impact as most important. Peers, family advocates, and supported employment and education specialists prioritized recovery. Family members and service-users were more likely to prioritize homelessness risk and the impact of medication, relative to most provider groups.

Figure 1:

Data Domain Priorities by Role

Note: Darker squares indicate a higher proportion of time each domain was selected as one of the four most important by participants. The bottom eight rows in the figure represent domains not originally included in the proposed battery, but suggested by participants

Qualitative Findings

Quotes indicative of the broader themes described below are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes that focus group participants considered important for early psychosis care, with selected quotations

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Selected Quote | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| What data domains are important to capture | Functioning, quality of life, and recovery identified as key outcomes | “I think a high quality of life is what everyone strives for. We all strive to be happy and these other things that we do, go to school, interact with others, socialize, these are all things we do in order to make use happy. These are kind of the end goals.” | Client Group 1. |

| Conceptual overlap between functioning, quality of life, and recovery | “Is there not a measure that combines the social and role functioning with quality of life and well-being? I mean, this feels.., to me it feels odd that we’re separating out those things.” | Provider Group 2. | |

| Capturing family functioning and stress important for family members | “That’s something that, for me, as a family member, I really appreciated when I was asked, ‘okay, we know what is going on with the client, but how are you doing? How are you feeling?’ I feel like, ‘oh, I’m important too. They want to know how I feel too.’” | Spanish Speaking Family Group 1 | |

| Homelessness considered not highly prevalent in EP services | “When I hear this domain [homelessness], it’s not really resonating with the current clients that we have under our program. It resonates a little bit more with our higher activity program like FSP.” | Provider Group 2. | |

| Why proposed data domains were considered important | Importance of predictors of outcome in clinical care | “If I want a tablet to give me some data that’s going to be useful to me, I want it to be predictive data, not just descriptive. If I’m thinking purely clinically, I would err on predictive versus descriptive.” | Provider Group 3. |

| How outcomes data can be used for external reporting | “If engagement in our program moves people on average two points on the quality-of-life scale, that’s a simple thing that you can say to an insurer, to a stakeholder, to a lawmaker. That’s a valuable outcome.” | Provider Group 4. | |

| Using data to support therapeutic interventions. | “I could see implementing this in treatment planning. Where ‘we’re going to quantify how satisfied are you with […] your health. Okay it’s January, you’re a five. Let’s come back again in six months or a year. We want you to be an eight. How are we going to get to an eight?’”. | Provider Group 5. | |

| Reducing redundancy of data collection | “They see a lot of us on different days, a therapist, then an occupational specialist, and a supported education/employment specialist, they probably don’t want to be answering these questions over and over. Having them answer them once and having access to them as a clinician or as a therapist, or education specialist I think would be good. |

Provider Group 6. | |

| How Data Should be Collected | Value of service-user self-report | “Self-reporting would be valuable for me because I want to encourage and increase engagement in the client and take ownership of the process. And then, by encouraging them to participate, answering these questions is gonna activate their own reflections of their own progress in their journey.” | Provider Group 7. |

| Type of Data that should be collected | Importance of concrete metrics, particularly for Hispanic/Latinx families | “That word: concrete. I think for ethnic minorities, maybe particularly Latino families, that concreteness of seeing their daughter or son going back to school, it’s something tangible to them that really, I think, makes a big difference in treatment recovery.” | Provider Group 4. |

| Conceptualization of Constructs | Recovery oriented, “I” statements in self-report measures valued | “These questions are amazing, and this is great. Like, this would be so helpful in outcomes, but also in clinical value. And for quality of life, it gives a really good overview of how they are thinking directly about themselves or ‘I’ statements for most of them. Like 99%. | Provider group 8. |

| Importance of using recovery-oriented, non-pejorative language in assessment tools |

“For me, I couldn’t say ‘stress’ or ‘family burden’ because it would affect my daughter to hear those two words. I know that it would affect her to know that her mother is thinking that she is a burden, or that she causes stress.” | Spanish speaking family group 1. | |

| Adopting a broad conceptualization of domains | Interviewer: “Which bits about family impact are most important? So, when we say ‘impact’, do you mean emotionally? Do you mean financially? Do you mean in terms of your own functioning and being able to get out and do things?” Family Member 1: “All of the Above” Family Member 4: “All of the above for us, personally.” |

English speaking family group 1. |

Data Domains Important to Capture

Congruent with the quantitative findings, quality of life, functioning, recovery, and symptoms were consistently identified as key domains to assess during EP care. Many participants highlighted the substantial impact psychosis can have on functioning, which in turn impacts quality of life. Given these were considered key outcomes of EP care, recovery was often framed as improvements these domains. Consequently, many participants used these interchangeably, or recognized substantial conceptual overlap between the terms, leading some to suggest the need to evaluate these collectively. Regarding less frequently voted for domains, substance use reduction was considered an important outcome for some service-user participants, while for family participants suicide risk, family functioning, and family impact was considered particularly meaningful.

When exploring why outcomes such as incarceration and homelessness were not frequently voted for, most participants recognized these as important, especially on a community level. However, many provider participants reported that they rarely interacted with homeless individuals due to their clinic’s inclusion criteria (i.e., the young age criteria; early course of illness; requirement for private insurance at some clinics). Many providers suggested this may be a greater issue after clients leave the clinic or later in their lives. For family and client participants, the issue of homelessness appeared more current. Multiple family and client participants recalled people they knew who became homeless or were concerned that homelessness may be a future outcome either after they age out of specialized care or when their family is no longer able to support them.

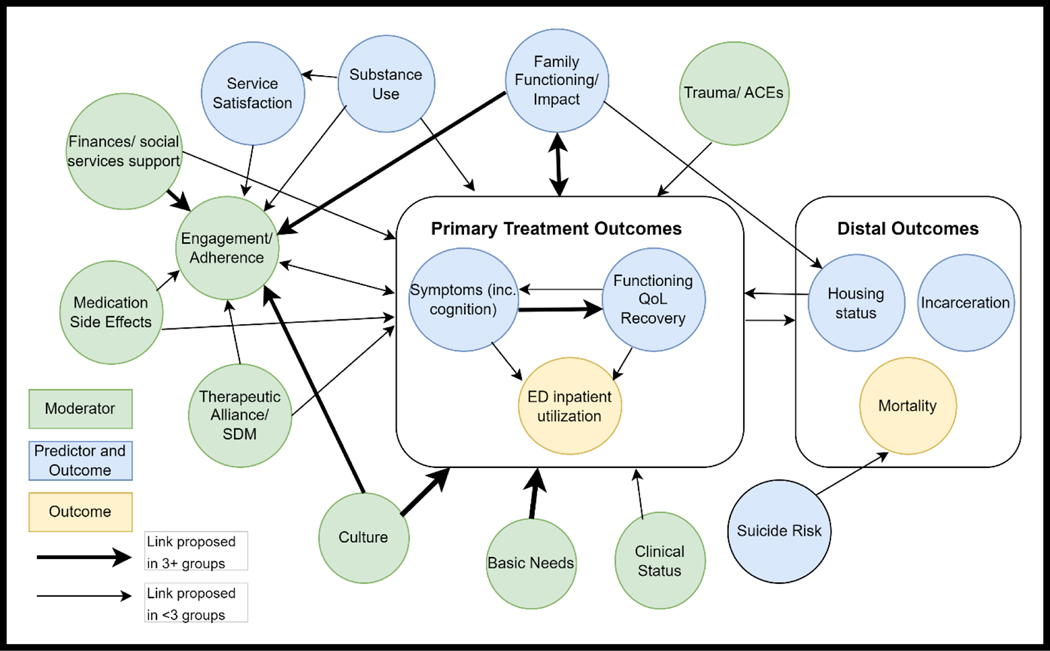

While the focus groups were originally framed around outcome assessment priorities, participants frequently switched the discussion to the importance of moderators and predictors of outcomes. The hypothesized relationships between predictors and outcomes proposed across the groups is detailed in Figure 2. These hypothesized predictors of outcome were considered critical to understanding a service-users’ clinical presentation, aid care planning, and to provide useful indicators of potential recovery trajectories. Modifiable predictors of outcome, such as family functioning, were considered particularly important given these were identified as potential opportunities to improve recovery trajectories.

Figure 2:

Schematic Framework of Hypothesized Relationships between Key Outcomes and Predictors, as Reported by Focus Group Participants

Participants identified multiple uses for the data. At the clinic level, outcomes data were considered important for service evaluation, quality improvement, and for external reporting to justify service funding. Questions about prior experiences were identified as important to family members and clients to ensure important issues were not missed. Providing data access to the whole clinical team was considered important to reduce the redundancy of data collection, and therefore, improve efficiency and client experience. Finally, the ability to track outcomes over time was considered particularly powerful for informing care delivery, quantifying treatment response, and utilizing as a therapeutic tool within sessions.

How Data Should be Collected

Participants explored the merits of utilizing self-report, clinician ratings, and collateral information. Some participants felt self-report surveys give greater agency to the client, may foster treatment engagement, can provide additive information to the provider, and may lead to more honest responses, particularly regarding suicidal ideation. However, across all roles, participants voiced concerns regarding the accuracy of self-report, suggesting that the impact of symptoms, social desirability, lack of trust, and challenges around understanding experiences and their attribution may negatively impact accuracy. Collateral information was considered important to mitigate some inaccuracies in client reports, particularly regarding observable behavior, with the added benefit of engaging the support person into care. Family participants emphasized needing their input to be confidential to ensure they can be honest. Additionally, there were concerns that family members may not know the full extent of some service-users’ experiences, possibly leading to inaccurate assessments.

Clinician administered surveys were considered helpful to address client comprehension challenges and relevancy of responses, and to create the opportunity for follow up questions that can both improve accuracy and help providers develop a greater understanding of the client. One drawback of clinician-rated assessments was a concern that they may add too much burden to already overworked clinical staff. Others were concerned about inter-rater reliability and the challenges of ensuring the consistency of ratings across multiple clinics and clinicians. Overall, participants appeared to indicate a preference for self-report, augmented with some collateral and provider information.

Type of Data Collected

Participants explored the benefits of utilizing objective metrics, for example, whether the service-user is employed or in school, versus abstract or summary scores, such as Likert scale ratings regarding treatment satisfaction. Overall, objective metrics were considered more accurate and translatable while helping to identify and evaluate actionable treatment goals and progress. Objective metrics were also considered more impactful in external reporting to community partners and funders. Regarding abstract scales, multiple participants felt they enabled greater subjectivity to represent clients’ wants and needs, with summary scores allowing for quicker interpretation. Overall, participants emphasized the importance of collecting both types of data for different purposes to maximize the utility of the information collected.

Conceptualization of Constructs

Participants emphasized the importance of adopting a recovery-oriented, strengths-based approach. Some participants were concerned that many of the published surveys reviewed during the focus group discussion focused too much on deficits, as opposed to strengths. Instead, participants reported that the data collected should be focused on client priorities and perspectives. In self-report surveys, the use of ‘I’ statements was appreciated.

Concerns around scales not utilizing recovery-oriented language were identified in multiple groups, with the term “family burden” used in one scale considered particularly problematic. Other areas where concerns were raised included “medication compliance/adherence”, “insight”, and the term “health issues”, given that some clients may not identify their experiences as such. To address this, terms such as “family impact” and “medication utilization” were proposed as more appropriate alternatives.

Another consistent theme regarding the conceptualization of constructs was that the prioritized domains should be considered in a broad fashion. Examples include incorporating social cognition within cognitive assessment batteries; extending family impact to consider the emotional, financial, social, vocational, and health impacts on the family; expanding incarceration to include all law enforcement contacts; and to examine shared decision-making, empathy, affect matching, and trust when considering therapeutic alliance. In the assessment of an individual’s background, participants highlighted the need for extensive information including prior treatment, duration of untreated psychosis, details of community support, family history, comorbid diagnoses, law enforcement contacts, and information about the culture of the client and their support system. Regarding cultural information relevant to care this included race and ethnicity, but extended to degree and nature of family involvement, understanding, cultural norms, and expectations of mental health treatment. Background information was considered important as a moderator of program engagement, clinical presentation, and treatment trajectory, all of which can inform treatment planning.

Discussion

Functioning, quality of life, recovery, and psychiatric symptoms were considered key outcomes to assess in EP care. However, predictors of outcomes, particularly modifiable predictors, were also considered important for their clinical utility. Overall, participants reported a preference for self-report measures, augmented with collateral and clinician ratings to support data accuracy. Clients and providers recognized the importance of both concrete and abstract measures as indicators of outcome, with each addressing different needs. To maximize the clinical utility of the data, participants encouraged a broad conceptualization of the prioritized domains and proposed adopting a recovery-oriented, strengths-based approach regarding both the constructs measured and the language used.

A strength of the study is the extensive process undertaken to solicit community partner feedback, including 178 participants across 10 clinics. Family members, clients, and providers across a diverse range of clinics participated. Additionally, the clinics themselves deliver early psychosis care to a diverse range of consumers in terms of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and gender identity. To support inclusion, focus group were conducted both in Spanish and English.

One limitation of the study is presenting a pre-determined list of domains, which was efficient but may have influenced voting patterns. Another was the challenge of implementing this project during the COVID-19 pandemic. This lengthened the project timeline, resulting in focus group members not being involved in a review of the conclusions consistent with best practice (21). Additionally, later groups were shifted to a remote platform, potentially creating a barrier to engagement for some. During this period, dropout led to only one participant presenting for a group on two occasions, and two participants for one Spanish Family group. Ultimately, the decision was taken to include the dyadic interview as a “group”, given they do facilitate interaction between participants (22), but exclude the single-person interviews. Notably, in all three occasions the data were highly consistent with the presented findings. Finally, in some instances, it was not possible to attribute quotes in the audio recording to a particular participant.

Throughout this study, a consistent theme was that providers, clients, and family members wanted their data to inform individual care decision-making and support clinic sustainability and development. Many identified various benefits of adopting measurement-based care practices in the EP setting. In large-scale collaborations where data is typically accumulated into a central repository for the purposes of research (i.e., 23), these findings highlight potential opportunities of ensuring that the same data is also made available to clients and providers to support assessment, care planning, and quantify treatment response. While the systematic collection of data can have a substantial positive impact on the delivery of mental health care (9, 24), these benefits are obviously contingent on the availability of that data to those that deliver and receive such care.

Notably, while the groups were initially framed around outcome prioritization, participants instead elected to dedicate a significant proportion of the discussion to focus on the merits of collecting predictive data. While some hypothesized connections between predictors and outcomes presented in the model have been reported in the literature (i.e., 25, 26), for others the existence of any causal pathway is currently undetermined and merits further investigation. Regardless, participants suggested such data were important to aid assessment, care planning, treatment delivery, and predict recovery trajectories. In the quantitative data, collection priorities differed across provider roles. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of engaging the full spectrum of community partners. Additionally, in the EP setting where the multidisciplinary team is key (27), it is important to consider that different team members may have different data needs and prioritize different outcomes.

Conclusions

This study highlights the impact that engagement of community partners can have on the development of CABs when they are fully integrated into the design process. Because of this work, the language used in the EPI-CAL battery was substantially amended (i.e., references to “family burden” were replaced with “family impact”). The battery also focuses on client self-report surveys, extensively reviews the clients’ history and cultural context in an “about you” survey, incorporates a mix of concrete and abstract measures of outcomes, expands the breadth of the constructs explored, and includes extensive information regarding identified predictors of outcomes that can inform care delivery in multiple ways. Additionally, these findings informed the EPI-CAL CAB development steering committee decision-making process, including shifting the emphasis of data collection to self-report measures, and supporting the inclusion of trauma and cognition measures as optional EPI-CAL CAB domains. By ensuring the voices of community partners were heard both on the statewide and national stage, it is hoped that the data being collected both through EPI-CAL and EPINET can better meet the priorities of all community partners. Finally, this work represents a roadmap to integrate community partners voices in the development of future LHCN’s and data harmonization efforts.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Service-users, family members, and providers considered functioning, quality of life, recovery, and symptoms of psychosis as key outcomes to assess in early psychosis care.

Participants emphasized the clinical utility of assessing predictors of outcomes, wanted a broad conceptualization of the constructs assessed, and preferred client-report measures.

Providers, service-users, and family members wanted their data to inform individual care decision-making and support clinic sustainability and development.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the early psychosis clinics and focus group attendees for their participation in the study. Additionally, we would like to thank Christopher Blay, Savinnie Ho, Antionette Aragon, Gabrielle Nguyen, Janet Mendoza, Julianna Kirkpatrick, and Samantha Sadler who conducted the cleaning of the focus group transcripts.

This research was funded by One Mind, the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH120555), Los Angeles County, Napa County, Orange County, San Diego County, Solano County, Sonoma County, and Stanislaus County. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of our funders, including the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM (eds): Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britto MT, Fuller SC, Kaplan HC, et al. : Using a network organisational architecture to support the development of Learning Healthcare Systems. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27:937–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon S, Florence P, Grigas M, et al. : Creating a learning healthcare system in surgery: Washington State’s Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) at 5 years. Surgery 2012; 151:146–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinssen RK, Azrin ST: A national learning health experiment in early psychosis research and care. Psychiatr Serv 2022; 73:962–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR: Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers J, Keeley T, Jones L, et al. : Using qualitative research to understand what outcomes matter to patients: direct and indirect approaches to outcome elicitation. Trials 2015; 16:1–125971836 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mease PJ, Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, et al. : Identifying the clinical domains of fibromyalgia: contributions from clinician and patient Delphi exercises. Arthritis Care Res Off J Am Coll Rheumatol 2008; 59:952–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. : Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012; 13:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaly T, Coombs T, Berk M: Routine outcome measurement by mental health-care providers. The Lancet 2003; 361:1137–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins R: Measuring outcomes in mental health: implications for policy, in Mental health outcome measures. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010, pp 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhalgh J, Meadows K: The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: a literature review. J Eval Clin Pract 1999; 5:401–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noonan VK, Lyddiatt A, Ware P, et al. : Montreal Accord on Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) use series–Paper 3: patient-reported outcomes can facilitate shared decision-making and guide self-management. J Clin Epidemiol 2017; 89:125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Os JIM, Altamura AC, Bobes J, et al. : Evaluation of the two-way communication checklist as a clinical intervention: results of a multinational, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184:79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priebe S, Kelley L, Omer S, et al. : The effectiveness of a patient-centred assessment with a solution-focused approach (DIALOG+) for patients with psychosis: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial in community care. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84:304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George P, Rosenblatt A, Daley T, et al. : The early psychosis intervention network (EPINET) national core assessment battery: building the foundation for a learning health care partnership, in the American Public Health Association’s VIRTUAL Annual Meeting and Expo. American Public Health Association. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon L, Jones N, Loewy R, et al. : Recommendations and challenges of the clinical services panel of the PhenX Early Psychosis Working Group. Psychiatr Serv 2019; 70:514–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V, Clarke V: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbour RS: Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? Bmj 2001; 322:1115–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, et al. : Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res 1999; 9:26–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lumivero NVivo (Version 12) www.lumivero.com.

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19:349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan DL, Ataie J, Carder P, et al. : Introducing Dyadic Interviews as a Method for Collecting Qualitative Data. Qual Health Res 2013; 23:1276–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkow ND, Koob GF, Croyle RT, et al. : The conception of the ABCD study: From substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2018; 32:4–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. : Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35:575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Rosenheck RA, et al. : Predictors of Hospitalization of Individuals With First-Episode Psychosis: Data From a 2-Year Follow-Up of the RAISE-ETP. Psychiatr Serv 2019; 70:569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mascayano F, van der Ven E, Martinez-Ales G, et al. : Disengagement from Early Intervention Services for Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr Serv 2021; 72:49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinssen RK, Goldstein AB, Azrin ST: Evidence-Based Treatments for First Episode Psychosis: Components of Coordinated Specialty Care 2014. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/nimh-white-paper-csc-for-fep_147096.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.