Abstract

This study aimed to: (i) analyze the variations in psychophysiological demands (mean heart rate, meanHR; rate of perceived exertion, RPE) and technical performance (umber of successful and unsuccessful passes, and occurrences of ball loss) between 2v2 and 4v4 small-sided games (SSGs) formats, and (ii) examine the relationships of aerobic capacity measured in Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (YYIRT) on psychophysiological and technical performance during SSGs. This study used a cross-sectional design with repeated measures, where the same players participated in both 2v2 and 4v4 formats across two training sessions per format. Twenty-four talent/developmental male youth soccer players, aged 16.6 ± 0.5 years. The meanHR, measured through heart rate sensors, the RPE, assessed using the CR6-20 scale, and the number of successful and unsuccessful passes, along with occurrences of ball loss, recorded using an ad hoc observational tool, were evaluated in each repetition. Players during the 2v2 format had significantly greater mean HR (+4.1%; p < 0.001; d = 2.258), RPE (+12.2%; p < 0.001; d = 2.258), successful passes (+22.2%; p = 0.006; d = 0.884), unsuccessful passes (+62.5%; p < 0.001; d = 1.197) and lost balls (+111.1%; p < 0.001; d = 2.085) than 4v4 format. The YYIRT was significantly and largely correlated with unsuccessful passes (r = 0.502; p = 0.012) and lost balls (r = 0.421; p = 0.041) in 2v2 format. In conclusion, this study suggests that engaging in 2v2 activities constitutes a more intense form of practice, significantly enhancing individual participation in technical aspects. Moreover, aerobic capacity may influence the smaller formats of play and how players perform key technical actions. Therefore, coaches must consider this to ensure the necessary performance in such games.

Key points.

The 2v2 small-sided game format significantly increases psychophysiological intensity, with higher mean heart rates and perceived exertion, compared to the 4v4 format. This suggests 2v2 is a more demanding training activity.

Players in 2v2 games experience a substantial rise in both successful and unsuccessful passes, as well as ball losses, indicating heightened individual involvement in technical actions compared to 4v4 games.

While aerobic capacity does not correlate with overall psychophysiological demands in small-sided games, it is significantly linked to the frequency of unsuccessful passes and lost possessions specifically in the 2v2 format.

Key words: Football, sports performance, sports training, ecological training

Introduction

Small-sided games (SSGs) are widely utilized training drills by coaches to promote ecological dynamics during training sessions, incorporating various performance dimensions such as physical, physiological, technical, and tactical elements (Hill-Haas et al., 2011; Ferreira-Ruiz et al., 2022). These representative drills simplify the actual game format, allowing coaches to manipulate task constraints and promote adaptive behaviors in players. This approach helps guide players to achieve specific tactical objectives within the games, while providing a multifaceted stimulus that includes technical, physical, and physiological aspects (Davids et al., 2013). Thus, inclusion of these games in the soccer training plan become popular, as they allow coaches to target the above-mentioned myriad of objectives while maintaining the fundamental dynamic characteristics of the game (Dellal et al., 2011a; 2012b). However, a detailed understanding of the effects resulting from different task constraint manipulations aids coaches in effectively achieving the desired exercise objectives (Fernández-Espínola et al., 2020; Clemente et al., 2021).

Descriptive research on the effects of various task manipulations during SSGs is extensive and well-established (Halouani et al., 2014; Clemente and Sarmento, 2020; Dios-Álvarez et al., 2022). Currently, there is a consistent body of evidence indicating that smaller playing formats (e.g., 2v2 to 4v4) are generally associated with higher intensity in heart rate responses and perceived effort (Clemente et al., 2014; Bujalance-Moreno et al., 2019). In terms of locomotor demands, these formats are described to increase the frequency of accelerations and decelerations, with a minimal impact on high-speed or sprint running (Castellano and Casamichana, 2013; Castillo et al., 2019). Furthermore, when compared to larger formats, smaller ones tend to result in an increased number of individual technical actions (both successful and unsuccessful) during the games (Clemente and Sarmento, 2020).

Typically, 2v2 formats are linked to efforts approaching or exceeding 90% of maximal heart rate (HRmax), and as the number of players increases (e.g., in 4v4), the average heart rate tends to decrease (Rampinini et al., 2007; Hill-Haas et al., 2011). Regarding technical actions, 2v2 formats usually allow for 5 to 6 ball possessions per minute, while this number may decrease to 4 in larger formats like 4v4 (Dellal et al., 2012a). However, it is crucial to note that these values are averages, and outcomes explored in research are often highly variable due to unreported and unobserved contextual factors in descriptive studies, particularly in the between-players analysis (Hill-Haas et al., 2008; Clemente et al., 2022a). These factors include environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, grass), biological aspects (e.g., physical fitness, readiness, trainability, technical and tactical proficiency), and game dynamics (e.g., match status, period of the match).

Factors such as a player's physical fitness (Younesi et al., 2021), or tactical expertise (Praça et al., 2016) are commonly overlooked in comparisons of the effects of different task constraints on soccer players' performance. Additionally, there is a lack of comprehensive analysis that simultaneously examines psychophysiological (e.g., heart rate responses, rate of perceived exertion) responses and technical aspects while incorporating contextual information such as physical fitness. For instance, it is widely acknowledged that aerobic capacity is a crucial physical attribute for soccer players (Stolen et al., 2005). Most of the match requires players to have the energy availability for moderate running, interspersed with intense periods. Additionally, aerobic capacity has been found to correlate with players who cover greater distances during a match (Redkva et al., 2018). Examining one of the few studies that integrates aerobic capacity into SSGs, it was found that a heightened proficiency in making repeated efforts, as assessed by the 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test, is associated with covering greater distances across various speed thresholds during SSGs (Younesi et al., 2021). Additionally, increased levels of hemoglobin were found to be correlated with elevated physiological responses during the games. In two other studies, a positive correlation was identified between higher aerobic capacity and increased distances covered (Lemes et al., 2020; Clemente et al., 2022b).

Despite the studies mentioned above, physical fitness is consistently overlooked as a variable related with variations between different playing formats. Considering that smaller formats are often more metabolically demanding than larger formats (Laursen and Buchheit, 2019), which place more strain on neuromuscular properties, understanding how greater aerobic capacity can influence performance in SSG is important. This knowledge can help coaches manage heterogeneity while organizing formats and distributing players effectively. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study that integrates psychophysiological responses and technical performance in comparisons between playing formats while considering physical fitness. Analyzing multiple dimensions of performance provides a more holistic view of the impact of task constraints on players (Paul et al., 2015), and incorporating physical fitness as a related factor aid in understanding how coaches should be attentive when organizing teams based on contextual factors related to the biological characteristics of the players. This approach aims to achieve a better interaction between task constraints, biological constraints, and environmental constraints (Newell, 1986). With this understanding, organizing drills and adapting them to the diverse soccer population becomes less challenging. It also ensures that the stimulus is appropriately adjusted based on the groups of players.

Given the aforementioned considerations, the present research pursues two objectives: (i) to analyze the variances in psychophysiological responses (mean heart rate, meanHR; rate of perceived exertion, RPE) and technical performance (umber of successful and unsuccessful passes, and occurrences of ball loss) between 2v2 and 4v4 playing formats in youth male soccer players, and (ii) to examine the relationship of aerobic capacity on the observed responses during these SSGs formats.

Methods

Participants

This study adopted a cross-sectional study design with repeated measures, wherein the same players participated in both 2v2 and 4v4 playing formats across two training sessions per format. Consequently, the study encompassed a total of four sessions. The sampling was made by conveniency.

Context of the study

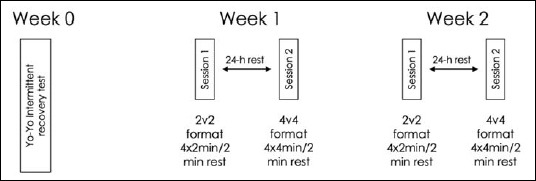

This study was conducted in the middle of the season, specifically during the autumn period, spanning two consecutive weeks. Participants underwent two sessions in each week. The first session involved the 2v2 format, followed by a 24-hour rest, and subsequently, they participated in the 4v4 format. This sequence was replicated in the second week. Importantly, the initial sessions in both weeks were scheduled 48 hours after the latest match. In the week preceding the observation of 2v2 and 4v4 sessions, the participants underwent an assessment of their aerobic capacity in the middle of the week (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

The sessions commenced at 5 pm and kicked off with a standardized warm-up protocol. This warm-up consisted of a 5-minute self-paced jogging, followed by 5 minutes of dynamic stretching focusing on the lower limbs, and concluded with a 5-minute ball possession game. Following a 2-minute rest, the players then engaged in the analyzed playing formats for this study.

The sessions took place on a synthetic turf, with no rainfall on the days of analysis. The average temperature throughout the sessions was 15.2 ± 1.6ºC, accompanied by a relative humidity of 66.2 ± 3.7%.

Participants

Taking into account the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) values derived from a prior study that compared 2v2 and 4v4 play formats (Dellal et al., 2011a), an effect size of 0.727 was employed as a reference for estimating the a priori sample size for repeated measures ANOVA for a single group, with a power of 0.85 and a p-value of 0.05. According to these parameters, the recommended sample size was 7 by using the G*Power 3.1 software (Düsseldorf, Germany). However, utilizing a convenience sampling approach within a single team, the entire team, consisting of 27 players, was invited to participate, with 24 players ultimately taking part in the study after excluding the goalkeepers. The participants belonged to the same team, competing at the tier 2 level (talent/developmental) (McKay et al., 2022). All participants were male, with an average age of 16.6 ± 0.5 years and an average of 3.4 ± 0.9 years of experience. The eligibility criteria for participation in this study and subsequent data analysis were as follows: (i) attendance at all training sessions during the two-week observation period; (ii) completion of the aerobic capacity assessment; and (iii) acting as outfield players. Participants were invited to take part in the study, and detailed information about the study design, procedures, risks, and benefits was provided before the commencement of the study. Subsequently, the players and their legal guardians signed an informed consent, explicitly stating the option to withdraw from the study at any time without facing consequences. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Chengdu Institute of Physical Education, with reference code 2023#104 and adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The small-sided games

The SSG formats were incorporated into the team's training sessions three minutes after the warm-up protocol ended. The first training session, used for the evaluation of 2v2, took place 48 hours after the last match, while the second training session, used for the evaluation of 4v4, occurred 24 hours after the previous training. To ensure consistency, the warm-up followed a standardized routine: 5 minutes of running, 10 minutes of lower limb dynamic stretching, and 5 minutes of reactive strength exercises and accelerations.

The 2v2 format was implemented for each session, comprising 4 repetitions of 2 minutes each, with a 2-minute rest interval between repetitions. Similarly, the 4v4 format was employed with 4 repetitions of 4 minutes each, interspersed by 2 minutes of rest per session. Both formats were executed without goalkeepers, utilizing a small goal positioned at the center of the endline with dimensions of 2 x 1 meters.

The pitch dimensions for the 2v2 format were 25 x 15 meters, while the 4v4 format occupied a space of 35 x 17 meters. This resulted in relative pitch dimensions of 94 and 92 m² per player, respectively, with a consistent width-to-length ratio of 1.7 in both cases.

Game rules adhered closely to official match regulations, with the exclusion of offside and ball reposition (replaced by foot reposition). No verbal instructions or encouragements were provided during the sessions. Team organization was left to the coaches' subjective perception of quality, and the teams comprised players from various playing positions. To minimize contextual variations, teams remained consistent throughout the study, as did their opponents.

Aerobic capacity assessment

The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (YYIRT) was administered during the team's second training session in the week before the study (evaluating the 2v2 and 4v4 formats) began. The test followed a standardized warm-up as part of this fitness assessment. Participants started the test at an initial running speed of 8 km/h. The protocol consisted of a series of 20-meter shuttle runs interspersed with periods of active recovery, guided by audio signals. The test initiated at 8 km/h, adhering to the progression outlined in the previously published original protocol (Krustrup et al., 2003). Participants were allowed two faults in reaching the line, and the test concluded if they failed to maintain the pace dictated by the audio signals. The distance covered (m) in the final shuttle completed was considered as the outcome for the test.

Psychophysiological responses

The participants were monitored with a 1Hz heart rate sensor (Polar RS400, Kempele, Finland) to track the mean heart rate during repetitions of 2v2 and 4v4 formats. To ensure consistency and eliminate inter-unit variability, each player consistently utilized the same device. Mean heart rate was obtained for each repetition.

The RPE was assessed using the 6-20 Borg Scale (Borg, 1998). The scale was validated against power output, heart rate, and oxygen consumption in a recent study, which also observed a high level of reliability when considering the scale adapted to the Chinese population (Ding et al., 2020). After each SSGs repetition, players were prompted to rate their perceived effort based on the scale and associated verbal anchors. Individual scores were recorded on a specifically designed sheet. It's worth noting that players were already acquainted with the scale as it was incorporated into their regular training routines. The score provided by the players after each repetition was then used for the statistical analysis.

Technical performance

An AKASO EK7000, equipped with 4K video recording capabilities, was strategically positioned to capture the entire pitch. The recorded video footage served as the primary data source for coding various technical actions, specifically focusing on passes completed, unsuccessful passes, and instances of lost possession. An ad hoc observational instrument was utilized, specifically designed to collect data on the frequency of completed passes (i.e., when the ball is successfully transitioned from one teammate to another without interference from the opponent), unsuccessful passes (i.e., when a player attempts to pass the ball to a teammate but it is intercepted or recovered by the opponent, making it impossible for the teammate to receive the ball), and lost possession (i.e., when a player loses control of the ball to the opponent or when the ball goes out of bounds). These actions were individually coded for each player, and the cumulative totals for each game were calculated.

To ensure the robustness of the coding process, two researchers with experience in performance analysis and notational analysis were tasked with coding the recorded events. However, recognizing the significance of data reliability, a preliminary exploratory study was conducted. This involved assessing one repetition of each format of play, with the observers conducting assessments twice, spaced 20 days apart.

The intra-class correlation test results demonstrated a high level of within-observer reliability, with a coefficient of 0.96, indicating consistent coding by the same observer. Additionally, the between-observer variability exhibited an average coefficient of 0.92, highlighting the reliability of codes performed across different observers.

Statistical procedures

The data is presented in the form of mean and standard deviation. The coefficient of variation (express in percentage) was calculated to express the variability of players within each format and between repetitions analyzed. The mean of the data extracted from the total repetitions was utilized for further inferential tests.

A t-paired test was performed to compare the same players in 2v2 and 4v4 formats of play. Effect size was calculated using the standardized effect size of Cohen (d). The magnitude of the effect size was categorized as follows (Cohen, 1988): 0.0-0.2, trivial; 0.2-0.5, small; 0.5-0.8, medium; and greater than 0.8, large. Additionally, correlations between aerobic capacity and psychophysiological and technical outcomes were explored using the Pearson product-moment correlation test. The magnitude of correlations was interpreted as follows (Hopkins et al., 2009): 0.0-0.1, trivial; 0.1-0.3, small; 0.3-0.5, moderate; 0.5-0.7, large; 0.7-0.9, very large; and greater than 0.9, nearly perfect. All statistical procedures were executed in SPSS (version 28.0.0., IBM, USA), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

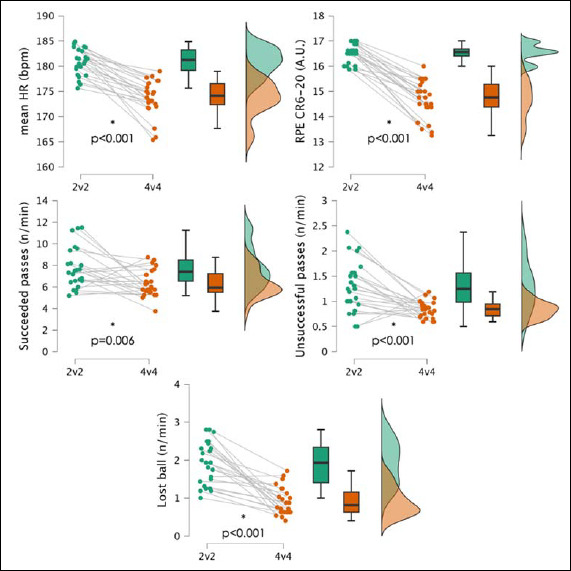

Figure 2 illustrates the descriptive statistics and within-player variation, taking into account psychophysiological responses and technical performance in both 2v2 and 4v4 formats. The within-player variability, expressed as the coefficient of variation (%), averaged across all repetitions in the 2v2 format, was 1.7% for mean heart rate, 8.6% for RPE, 29.2% for successful passes, 71.2% for unsuccessful passes, and 53.9% for lost balls. In the 4v4 format, the within-players variability averaged 2.5% for mean heart rate, 12.2% for RPE, 2.4% for successful passes, 64.1% for unsuccessful passes, and 66.9% for lost balls.

Figure 2.

Descriptive statistics showing players' psychophysiological responses and technical performance in both 2v2 and 4v4 formats. * significantly different between playing formats; HR: heart rate.

Players during the 2v2 format had significantly greater mean heart rate (+4.1%, 180.9 ± 2.7 vs. 173.7 ± 3.6 bpm; p < 0.001; d = 2.258 [95%CI: 1.371; 3.146]), RPE (+12.2%, 16.5 ± 0.4 vs. 14.7 ± 0.8 A.U.; p < 0.001; d = 2.258 [95%CI: 1.945; 4.029]), successful passes (+22.2%, 7.7 ± 1.9 vs. 6.3 ± 1.2 n/min; p = 0.006; d = 0.884 [95%CI: 0.225;1.543]), unsuccessful passes (+62.5%, 1.3 ± 0.5 vs. 0.8 ± 0.2 n/min; p < 0.001; d = 1.197 [95%CI: 0.517; 1.878]) and lost balls (+111.1%, 1.9 ± 0.6 vs. 0.9 ± 0.4 n/min; p < 0.001; d = 2.085 [95%CI: 1.215; 2.956] than 4v4 format.

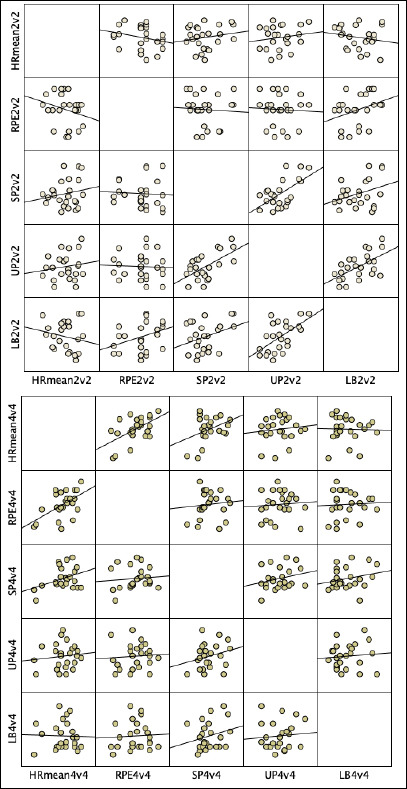

The relationships between psychophysiological responses and technical performance in both 2v2 and 4v4 formats are shown in Figure 3. No significant correlations (p > 0.05) were identified among variables in the 2v2 format. Conversely, in the 4v4 format, the mean HR exhibited a moderate correlation with successful passes, though the association did not reach statistical significance (r = 0.368 [95%CI: -0.050; 0.667]; p = 0.077).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot showing the associations between psychophysiological outcomes (mean heart rate: HRmean; rate of perceived exertion: RPE) and technical performance (SP: successful passes; UP: unsuccessful passes; LB: lost ball) for each play format.

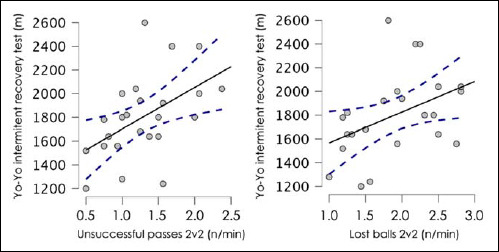

Figure 4 shows the scatterplot considering the relationships between the YYIRT distance covered and the unsuccessful passes and lost balls in 2v2 format. The YYIRT was significantly and largely correlated with unsuccessful passes (r = 0.502 [95%CI: 0.113;0.748]; p = 0.012) and lost balls (r = 0.421 [95%CI: 0.012;0.700]; p = 0.041) in 2v2 format. However, no significant correlations were found between YYIRT and unsuccessful passes (r = -0.061; p = 0.779) and lost balls (r = -0.188; p = 0.380) in 4v4 format. Additionally, no significant correlations were found between YYIRT in mean heart rate (2v2: r = 0.103, p = 0.632; 4v4: r = -0.105, p = 0.624), RPE (2v2: r = 0.174, p = 0.417; 4v4: r = -0.002, p = 0.994), and successful passes (2v2: r = 0.111, p = 0.604; 4v4: r = 0.368, p = 0.077).

Figure 4.

Scatterplot considering the relationships between the performance at Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test level 1 (YYIRT) and the number of unsuccessful passes and lost balls in 2v2 format.

Discussion

This study revealed that 2v2 serves as a significantly more intense drill in terms of heart rate stimulus and perceived exertion. Furthermore, individual technical actions standardized per minute were significantly higher in the 2v2 format compared to the 4v4 format. Although most results suggest a lack of significant correlations between psychophysiological responses and technical performance outcomes, aerobic capacity showed significant correlations only with lost balls and unsuccessful passes in the 2v2 format.

Our findings revealed that both mean HR and RPE were significantly higher in 2v2 formats. The substantial difference in magnitude suggests that the smaller the format, the more intense the psychophysiological response. These results align with prior studies that consistently show 2v2 to be typically more intense in terms of heart rate responses (Williams and Owen, 2007; Dellal et al., 2011b), blood lactate concentrations (Aroso et al., 2004; Hill-Haas et al., 2009), and perceived exertion (Little and Williams, 2007).

This heightened intensity in 2v2 can be attributed to various factors, one of which is individual participation in the match (Clemente and Sarmento, 2020). In very small formats, such as 2v2, individual actions are more pronounced, as evidenced by the number of technical actions analyzed in our study. Furthermore, tactical behaviors like 2v2 tend to be more focused on attempts for penetration (Castelão et al., 2014), lost balls and recovers for defensive action, requiring players to dynamically switch between attacking and defending roles often. Technical and tactical behavior can constrain physical demands, specifically by increasing the frequency of high accelerations and reducing the time for individual recovery between actions (Dimitriadis et al., 2022).

As the number of players increases in larger formats, such as 4v4, the game becomes more structured, considering player positions (Machado et al., 2019). This results in a decrease in individual initiative to overcome direct opponents, giving way to more collective behaviors like ball circulation, mobility actions, and cohesive team play (Castelão et al., 2014). Both 2v2 and 4v4 formats exhibit these behaviors, leading to variations in locomotor and mechanical actions. Smaller formats, with their reduced pitch dimensions, show greater accelerations, decelerations, and changes of direction, imposing higher metabolic demands (Lacome et al., 2018).

As the number of players progresses to larger formats, the pitch size also increases (Hill-Haas et al., 2011). Despite maintaining the relative area per player, the larger space make possible covering greater distances and achieving higher running intensities (Castagna et al., 2017). However, the structured actions become more prevalent in players, resulting in a less intense physiological response (Clemente et al., 2020). Nevertheless, there may be an increase in certain running actions, such as high-intensity running, as the game evolves with more players on the field in a larger longitudinal space.

Our findings also indicated that successful and unsuccessful passes, as well as lost possessions, were significantly more frequent during 2v2 compared to 4v4 matches. These results align with previous studies that have reported similar findings (Clemente and Sarmento, 2020). In smaller formats, the proximity of players without the ball is higher (Silva et al., 2016), providing a closer passing option for the player in possession. This proximity may create opportunities for successful passes, but it also contributes to an increase in lost possessions. In 2v2 matches, where the field is smaller, the frequency of attempts, especially those aimed at penetration or passing to a teammate, can lead to more lost possessions due to interceptions by opponents, who are closer to the center of the game (Dellal et al., 2012a).

The higher volume of successful passes in 2v2 matches is accompanied by a corresponding increase in unsuccessful passes. This dynamic is likely a result of the more frequent attempts to penetrate or execute passes (Castelão et al., 2014), leading to a higher likelihood of both successful and unsuccessful outcomes. Moreover, the significantly higher physiological intensities in the 2v2 format may also influence the ability to maintain accuracy in technical performance due to potential interference from fatigue (Dong et al., 2022).

Interestingly, when examining the correlations between aerobic capacity and technical performance, our study revealed that higher aerobic capacity is associated with a greater number of unsuccessful passes and lost possessions. Although this study did not have access to systems for monitoring locomotor demands, it is commonly observed that higher aerobic capacity is linked to increased distances covered (Lemes et al., 2020; Clemente et al., 2022b). Players with higher aerobic capacity typically cover greater distances during a game. This increased movement can lead to greater physical and mental fatigue over time, potentially impacting their technical skills such as passing accuracy and ball control. The cognitive and physical demands of maintaining high performance across extended periods can lead to errors and decreased technical execution (Younesi et al., 2021).

This lack of correlation may stem from the evidence that, typically, higher aerobic capacity correlates with greater distances covered, and this increased neuromuscular effort may impair the ability to execute technical actions effectively (Kellis et al., 2006), potentially contributing to the higher incidence of unsuccessful passes and lost possessions.

While the study results reveal interesting insights, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations. One limitation of the study is that it was conducted within a single team, warranting caution when generalizing the findings. This also introduces a potential bias, as only some participants played on the weekend, which could influence the training sessions after the matches. To establish the robustness of the results, it is imperative to consider multiple contexts. Additionally, this study did not delve into the analysis of locomotor and mechanical demands, as well as tactical collective behaviors, which are pivotal variables that could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics influencing the observed outcomes. Therefore, future research should take a holistic approach by integrating physiological, physical, technical, and tactical responses. This would allow for the identification of correlations and interactions between these variables, helping to explain potential performance impairments during specific formats.

Despite these limitations, the study holds practical implications. For instance, it suggests that 2v2 serves as a SSG format for inducing the most intense physiological stimulus in players while fostering more individual technical actions. Coaches should take this into account when selecting drills based on their objectives. Moreover, due to its intensity, the metabolic efforts involved in 2v2 can be recommended for a more aerobic power workout. As a key takeaway, coaches should ultimately organize player assignments to teams based on their aerobic capacity. They can use additional task constraints to increase or decrease the intensity, ensuring that the technical performance during these games is not significantly impacted.

Conclusion

The 2v2 format reveals significantly higher psychophysiological intensity compared to the 4v4 format, and the minimal variability observed within and between sessions suggests the stability of these results. Additionally, there is a notable increase in both successful and unsuccessful passes, as well as lost possessions, in the 2v2 setting when contrasted with the 4v4 scenario. Notably, aerobic capacity does not appear to exhibit a meaningful correlation with overall psychophysiological efforts, consistent with prior findings. However, in our study, we observed a correlation between aerobic capacity and the frequency of unsuccessful passes and lost possessions specifically within the context of 2v2 play.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare no potential or actual conflicts of interest. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author who was an organizer of the study. The experiments comply with the current laws of the country where they were performed.

Biographies

Tao WANG

Employment

Geely University of China, 641423 Chengdu, China

Degree

University Teachers

Research interests

Mainly engaged in research in sports training and fitness, etc.

E-mail: wangtao@guc.edu.cn

TianQing XUE

Employment

School of Physical Education, Chizhou University, Anhui,China

Degree

University Teachers

Research interests

Mainly engaged in research in sports training and tennis, etc.

E-mail: xtq2022@czu.edu.cn

Jia HE

Employment

Sichuan Normal University, 610066 Chengdu, China

Degree

University Teachers

Research interests

Mainly engaged in research in sports training, soccer and fitness, etc.

E-mail: 8524917@qq.com

References

- Aroso J., Rebelo A.N., Gomes-Pereira J. (2004) Physiological impact of selected game-related exercises. Journal of Sports Sciences 22, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Borg G. (1998) Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign IL, USA: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Bujalance-Moreno P., Latorre-Román P.Á., García-Pinillos F. (2019) A systematic review on small-sided games in football players: Acute and chronic adaptations. Journal of Sports Sciences 37, 921-949. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1535821 10.1080/02640414.2018.1535821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna C., Francini L., Póvoas S.C.A., D’Ottavio S. (2017) Long-Sprint Abilities in Soccer: Ball Versus Running Drills. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 12, 1256-1263. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0565 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelão D., Garganta J., Santos R., Teoldo I. (2014) Comparison of tactical behaviour and performance of youth soccer players in 3v3 and 5v5 small-sided games. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport 14, 801-813. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2014.11868759 10.1080/24748668.2014.11868759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano J., Casamichana D. (2013) Differences in the number of accelerations between small-sided games and friendly matches in soccer. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 12, 209-210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24137079/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D., Raya-González J., Clemente F.M., Yanci J. (2019) The influence of youth soccer players’ sprint performance on the different sided games’ external load using GPS devices. Research in Sports Medicine 28, 194-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2019.1643726 10.1080/15438627.2019.1643726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Afonso J., Castillo D., Arcos A.L., Silva A.F., Sarmento H. (2020) The effects of small-sided soccer games on tactical behavior and collective dynamics: A systematic review. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 134, 109710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109710 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Afonso J., Sarmento H. (2021) Small-sided games: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Plos One 16, e0247067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247067 10.1371/journal.pone.0247067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Aquino R., Praça G.M., Rico-González M., Oliveira R., Silva A.F., Sarmento H., Afonso J. (2022a) Variability of internal and external loads and technical/tactical outcomes during small-sided soccer games: a systematic review. Biology of Sport 39, 647-672. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2022.107016 10.5114/biolsport.2022.107016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Martins F.M.L., Mendes R.S. (2014) Developing Aerobic and Anaerobic Fitness Using Small-Sided Soccer Games: Methodological Proposals. Strength and Conditioning Journal 36, 76-87. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000063 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Sarmento H. (2020) The effects of small-sided soccer games on technical actions and skills: A systematic review. Human Movement 21, 100-119. https://doi.org/10.5114/hm.2020.93014 10.5114/hm.2020.93014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente F.M., Silva A.F., Kawczyński A., Yıldız M., Chen Y.S., Birlik S., Nobari H., Akyildiz Z. (2022b) Physiological and locomotor demands during small-sided games are related to match demands and physical fitness? A study conducted on youth soccer players. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 14, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00535-w 10.1186/s13102-022-00535-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Davids K., Araújo D., Correia V., Vilar L. (2013) How small-sided and conditioned games enhance acquisition of movement and decision-making skills. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 41, 154-161. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e318292f3ec 10.1097/JES.0b013e318292f3ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellal A., Chamari K., Owen A.L., Wong D.P., Lago-Penas C., Hill-Haas S. (2011a) Influence of technical instructions on the physiological and physical demands of small-sided soccer games. European Journal of Sport Science 11, 341-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2010.521584 10.1080/17461391.2010.521584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellal A., Drust B., Lago-Penas C. (2012a) Variation of Activity Demands in Small-Sided Soccer Games. International Journal of Sports Medicine 33, 370-375. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1295476 10.1055/s-0031-1295476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellal A., Hill-Haas S., Lago-Penas C., Chamari K. (2011b) Small-Sided Games in Soccer: Amateur vs. Professional Players’ Physiological Responses, Physical, and Technical Activities. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 25, 2371-2381. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fb4296 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fb4296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellal A., Varliette C., Owen A., Chirico E.N., Pialoux V. (2012b) Small-Sided Games Versus Interval Training in Amateur Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26, 2712-2720. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31824294c4 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31824294c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis Y., Michailidis Y., Mandroukas A., Gissis I., Mavrommatis G., Metaxas T. (2022) Internal and external load of youth soccer players during small-sided games. Trends in Sport Sciences 29, 171-181. [Google Scholar]

- Ding W., You T., Gona P.N., Milliken L.A. (2020) Validity and reliability of a Chinese rating of perceived exertion scale in young Mandarin speaking adults. Sports Medicine and Health Science 2, 153-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2020.08.001 10.1016/j.smhs.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dios-Álvarez D.E. V, Lorenzo-Martínez M., Padrón-Cabo A., Rey E. (2022) Small-sided games in female soccer players: a systematic review. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 62, 1474-1480. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12888-9 10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12888-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Pageaux B., Romeas T., Berryman N. (2022) The effects of fatigue on perceptual-cognitive performance among open-skill sport athletes: A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2135126 10.1080/1750984X.2022.2135126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Espínola C., Robles M.T.A., Fuentes-Guerra F.J.G. (2020) Small-sided games as a methodological resource for team sports teaching: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061884 10.3390/ijerph17061884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Ruiz Á., García-Banderas F., Martín-Tamayo I. (2022) Systematic Review: Technical-Tactical Behaviour in Small-Sided Games in Men’s Football. Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes 148, 42-61. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/2).148.06 10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/2).148.06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halouani J., Chtourou H., Gabbett T., Chaouachi A., Chamari K. (2014) Small-sided games in team sports training: a brief review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 28, 3594-3618. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000564 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Haas S., Coutts A., Rowsell G., Dawson B. (2008) Variability of acute physiological responses and performance profiles of youth soccer players in small-sided games. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 11, 487-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.006 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Haas S. V, Dawson B.T., Coutts A.J., Rowsell G.J. (2009) Physiological responses and time-motion characteristics of various small-sided soccer games in youth players. Journal of Sports Sciences 27, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802206857 10.1080/02640410802206857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Haas S. V, Dawson B., Impellizzeri F.M., Coutts A.J. (2011) Physiology of small-sided games training in football: a systematic review. Sports Medicine 41, 199-220. https://doi.org/10.2165/11539740-000000000-00000 10.2165/11539740-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins W.G., Marshall S.W., Batterham A.M., Hanin J. (2009) Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 41, 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis E., Katis A., Vrabas I.S. (2006) Effects of an intermittent exercise fatigue protocol on biomechanics of soccer kick performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 16, 334-344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00496.x 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krustrup P., Mohr M., Amstrup T., Rysgaard T., Johansen J., Steensberg A., Pedersen P.K., Bangsbo J. (2003) The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test: Physiological Response, Reliability, and Validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 35, 697-705. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000058441.94520.32 10.1249/01.MSS.0000058441.94520.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacome M., Simpson B.M., Cholley Y., Lambert P., Buchheit M. (2018) Small-Sided Games in Elite Soccer: Does One Size Fit All? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 13, 568-576. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0214 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen P., Buchheit M. (2019) Science and Application of High-Intensity Interval Training: Solutions to the Programming Puzzle. Champaign IL, USA: Human Kinetics. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781492595830 10.5040/9781492595830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemes J.C., Guerreiro R.C., Rodrigues V.A.O., Bredt S.G.T., Diniz L.B.F., Chagas M.H., Praca G. M. (2020) Effect of specific endurance on the physical responses of young athletes during soccer small-sided games. Kinesiology 52, 258-264. https://doi.org/10.26582/k.52.2.11 10.26582/k.52.2.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little T., Williams A.G. (2007) Measures of Exercise Intensity During Soccer Training Drills With Professional Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 21, 367-371. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-19445.1 10.1519/R-19445.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado G., Padilha M.B., Víllora S.G., Clemente F.M., Teoldo I. (2019) The effects of positional role on tactical behaviour in a four-a-side small-sided and conditioned soccer game. Kinesiology 51, 261-270. https://doi.org/10.26582/k.51.2.15 10.26582/k.51.2.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay A.K.A., Stellingwerff T., Smith E.S., Martin D.T., Mujika I., Goosey-Tolfrey V.L., Sheppard J., Burke L. M. (2022) Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 17, 317-331. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0451 10.1123/ijspp.2021-0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell K.M. (1986) Constraints on the development of coordination. In: Motor Development in children: Aspects of coordination and control. Ed: Wade M.G. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff. 341-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4460-2_19 10.1007/978-94-009-4460-2_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D. J., Bradley P. S., Nassis G.P. (2015) Factors Impacting Match Running Performances of Elite Soccer Players: Shedding Some Light on the Complexity. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 10, 516-519. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0029 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praça G.M., Costa C.L.A., Costa F.F., de Andrade A.G.P., Chagas M.H., Greco J.P. (2016) Tactical behavior in soccer small-sided games: Influence of tactical knowledge and numerical superiority. Journal of Physical Education (Maringa) 27. [Google Scholar]

- Rampinini E., Impellizzeri F.M., Castagna C., Abt G., Chamari K., Sassi A., Marcora S. M. (2007) Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. Journal of Sports Sciences 25, 659-666. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410600811858 10.1080/02640410600811858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redkva P.E., Paes M.R., Fernandez R., Da-Silva S.G. (2018) Correlation Between Match Performance and Field Tests in Professional Soccer Players. Journal of Human Kinetics 62, 213-219. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2017-0171 10.1515/hukin-2017-0171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Vilar L., Davids K., Araújo D., Garganta J. (2016) Sports teams as complex adaptive systems: manipulating player numbers shapes behaviours during football small-sided games. Springerplus 5, 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1813-5 10.1186/s40064-016-1813-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolen T., Chamari K., Castagna C., Wisloff U. (2005) Physiology of soccer: an update. Sports Medicine 35, 501-536. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535060-00004 10.2165/00007256-200535060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K., Owen A. (2007) The impact of player numbers on the physiological responses to small sided games. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine Suppl 10, 99-102. [Google Scholar]

- Younesi S., Rabbani A., Clemente F.M., Silva R., Sarmento H., Figueiredo A.J. (2021) Relationships Between Aerobic Performance, Hemoglobin Levels, and Training Load During Small-Sided Games: A Study in Professional Soccer Players. Frontiers in Physiology 12, 649870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.649870 10.3389/fphys.2021.649870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]