Abstract

Fungal sinusitis encompasses a wide range of diseases, including both invasive and noninvasive, acute, and chronic forms. The incidence of invasive sinusitis is on the rise, primarily affecting immunocompromised individuals and diabetics. This case report highlights a patient who developed invasive fungal sinusitis despite no other apparent cause of immunosuppression. Imaging studies suggested the diagnosis, confirmed by presence of Aspergillus flavus on mycological culture.

Keywords: Invasive fungal sinusitis, Aspergillus flavus, CT, MRI

Introduction

Sinus fungal infections encompass several pathological entities. Differentiation between noninvasive and invasive forms of fungal sinusitis is based on the presence or absence of tissue invasion by the fungal pathogen [1]. Noninvasive fungal sinusitis includes 3 subtypes: fungal ball, saprophytic fungal sinusitis, and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Similarly, invasive fungal sinusitis can be classified into 3 subtypes: acute invasive rhinosinusitis, chronic invasive rhinosinusitis, and granulomatous invasive sinusitis [2,3]. Fungal sinusitis is more common in patients who are immunocompromised, diabetic, or undergoing corticosteroid therapy. The main symptoms include nasal congestion, cacosmia, nasal pain, and headache [[2], [3], [4]]. Typical radiological findings include sinus opacification on CT scans and a T2-weighted hypointense signal on MRI [5]. The combination of CT (showing diffuse, heterogeneous, hyperdense filling of the rhinosinus cavities, with "blown" expansions of the sinus bone walls) and MRI (revealing the extensive nature and T1 and T2 hyposignal lesions with a cerebriform appearance of the fungal process) aids in diagnosis [6]. This case study is particularly interesting due to the scarcity of epidemiological and imaging data on invasive fungal sinusitis in our region.

Case report

A 60-year-old female patient, with a family history of atopy, irregular corticosteroid intake, and a background of chronic sinusitis with poor follow-up, was referred to the medical imaging department due to left exophthalmos and visual disturbances. These symptoms were accompanied by nasal obstruction, anosmia, and chronic purulent rhinorrhea.

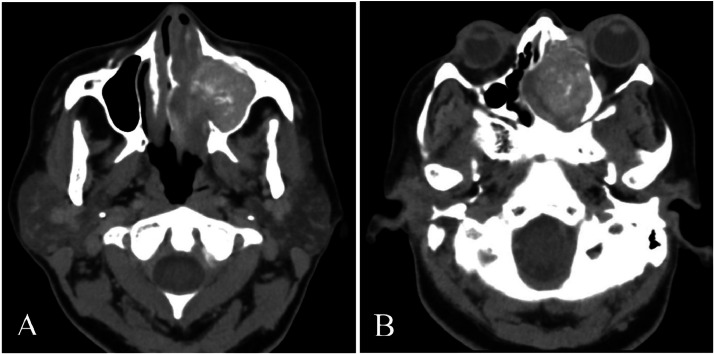

Orbital and cerebral CT scans, both without and with contrast medium injection, revealed a filling process containing calcifications involving the left sinuses, particularly the maxilla, extending into the left nasal cavity. This process disrupted the bony cortices of the sinus walls and partially lysed the roof of the left orbit, protruding into the skull at the left frontal lobe level. Additionally, it exerted a mass effect on the left medial rectus muscle, resulting in homolateral Grade I exophthalmos (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Axial slice CT scan in parenchymal window demonstrating heterogeneous spontaneously hyperdense filling, obstructing the left nasosinus cavities. The mass exerts pressure on the nasal septum, displacing it to the right, and contributes to grade I left exophthalmos.

Fig. 2.

CT axial section in parenchymal window (A) and a coronal reconstruction in bone window (B). It demonstrates the filling of the left nasosinus cavities with calcifications, associated with bone lysis affecting the sinus walls and the roof of the left orbit.

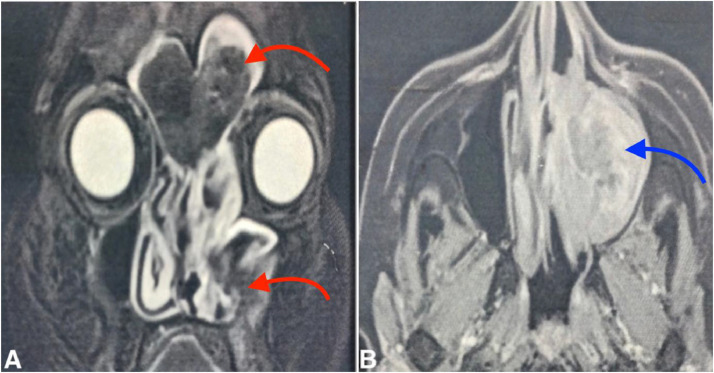

Further magnetic resonance imaging (with T2, T1 Fatsat sequences without and with gadolinium, and diffusion) confirmed extensive fronto-ethmoido-maxillary fungal sinusitis. This was characterized by complete filling of the left sinus cavities by a process with signal voids on T2 and with peripheral enhancement. There was maxillary ostio-meatal obstruction, compression of the nasal turbinates (especially the left middle turbinate), and deviation of the nasal septum to the right (Fig. 3). Notably, no diffusion restriction was observed within the sinus filling.

Fig. 3.

MRI in coronal T2 FATSAT sequence with signal voids within the frontal and left maxillary sinus opacities (red arrows) (A), and an axial T1 FATSAT sequence post-Gadolinium injection demonstrating contrast enhancement (blue arrow) (B).

Despite reflow of the papyraceous lamina and enhancement of the left frontal diploea and left leptomeninge, there was no invasion of the orbital fat. Endoscopic surgery was undertaken based on these findings, with histological and mycological culture samples confirming the presence of Aspergillus flavus.

Discussion

Invasive fungal sinusitis occurs exclusively in immunocompromised patients and is primarily caused by Aspergillus, especially in diabetic patients [7,8]. In our case, the patient was not diabetic but had a history of chronic sinusitis with fairly regular corticosteroid intake. Long-term corticosteroid therapy is known to cause immunosuppression [9]. Tanon AK et al. reported a rare case of invasive fungal maxillary sinusitis in an immunocompetent subject [10].

Clinical suspicion should guide the choice of the most appropriate imaging method [11]. CT scans are used to diagnose invasive sinusitis (characterized by the association of sinus thickening and contact osteolysis) and to assess the extent of the disease. Osteolysis is not always visible on CT; however, when present, it should raise suspicion of an invasive fungal origin [7,12]. MRI is often performed when there is suspected endocranial and/or orbital extension on CT [13]. In our case, MRI confirmed the suspected endocranial extension, showing a process occupying the sphenoidal sinus, eroding its various walls, and extending into the cavernous cavities. There was no invasion of orbital fat, but enhancement of the left frontal diploic space and left leptomeninges was observed.

Acute invasive fungal sinusitis is characterized histologically by fungal invasion of blood vessels, resulting in severe clinical manifestations, including vasculitis, thrombosis, hemorrhage, tissue necrosis, and an acute inflammatory infiltrate rich in neutrophils [14]. Invasive fungal sinusitis caused by Aspergillus usually occurs in debilitated patients (e.g., those with diabetes or immunosuppression). It progresses rapidly to the perisinus structures (orbits, face, skull base, endocranium) through vascular, tissue, and bone invasion and can be life-threatening if left untreated. CT/MRI imaging is used to assess the extent of this invasive fungal pathology, which can be confirmed by biopsies of nasosinus lesions [4,15].

The chronic form (evolving after 4 weeks) also shows bone metaplasia and mucoperiosteal thickening of the sinus walls. Chronic granulomatous fungal rhinosinusitis has a geographical predisposition (India, Pakistan, Sudan, Saudi Arabia). Its clinical and radiological presentation is similar to that described above, occurring in immunocompetent patients. Diagnosis is histological, with Aspergillus flavus being the most common pathogen. Management, which is not well codified, involves both medical and surgical approaches [16].

In both acute and chronic forms, imaging is used to look for extension to soft tissues (e.g., orbital fat, retro-maxillary fat) and cerebromeningeal spaces, as well as invasion of adjacent structures. Imaging also helps identify complications such as sub- or extra-dural empyema, meningitis, abscess, thrombophlebitis, and arteritis. Despite extensive surgical debridement and antifungal treatment, the prognosis remains poor [7].

Several differential diagnoses may be considered in cases of invasive fungal sinusitis, including lymphoma, tuberculosis, or malignancy [17]. Najoua B. N et al., in 2018, studied 2 cases of nasal lymphoma where CT helped orient the diagnosis, often revealing a solid tumor appearance that was poorly or not enhanced by contrast injection. MRI is useful in assessing extension to adjacent structures and differentiating the tumoral process from an inflammatory appearance [18].

Primary nasosinus tuberculosis is a relatively rare condition with a polymorphous and nonspecific clinical presentation. In their 2020 study, Zegmout A et al. described CT findings similar to our own, showing a filling of all facial sinuses with tissue-dense material, local lysis, and expansion of the ethmoidal cell walls, in addition to slight deviation of the inner wall of the right orbit, pushing back the medial rectus muscle. Definitive diagnosis of nasosinus tuberculosis is based on pathological and mycobacteriological examination of a biopsy specimen [19].

The imaging appearance of invasive fungal sinusitis can resemble an intrasinus malignant tumor. Nasosinus malignancies encompass a wide range of tumors with varied histologies and localizations but often present similarly clinically. Nasosinus carcinoma is the most common form. Diagnosis of these tumors is challenging and requires a multidisciplinary approach. The usual radiological appearance is a solid, homogeneous tumor mass, enhancing after injection of contrast and typically osteolytic. Intratumoral calcifications may also be present [20].

In our case, imaging guided the diagnosis, but definitive confirmation was provided by microbiological examination, which showed isolation of Aspergillus flavus after culture on Sabouraud's medium.

Conclusion

Invasive fungal sinusitis presents a significant clinical challenge owing to its aggressive local nature, often mimicking tumoral pathology on imaging. Within the context of immunodepression, characteristic imaging findings such as sinus filling with calcifications on CT and T2 signal voids on MRI strongly indicate the diagnosis. Confirmation typically entails the isolation of filamentous fungi, predominantly Aspergillus flavus.

Patient consent

The patient has signed an informed consent form.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Références

- 1.Lassausaie A, Barthélémy I. Rhinosinusites fongiques des sinus maxillaires. Chirurgie Orale Et Maxillo-Faciale. 2021;34(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira MLC, Anselmo-Lima WT, Faria FM, Queiroz DLC, Nogueira RL, Leite MGJ, et al. Impact of early detection of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in immunocompromised patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3938-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharif MS, Ali S, Nisar H. Frequency of granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis in patients with clinical suspicion of chronic fungal rhinosinusitis. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4757. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deutsch PG, Whittaker J, Prasad S. Invasive and non-invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: a review and update of the evidence. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55(7):319. doi: 10.3390/medicina55070319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raz E, Win W, Hagiwara M, Lui YW, Cohen B, Fatterpekar GM. Fungal sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2015;25(4):569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Marco L, Pujo K, Molly D, Boibieux A, Ltaïef-Boudrigua A. Rhino sinusite fongique allergique: un diagnostic à évoquer. Presse Med. 2018;47:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lafont E, Aguilar C, Vironneau P, Kania R, Alanio A, Poirée S, et al. Sinusites fongiques. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires. 2017;34(6):672–692. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkinson, J.C.; Clarke, R.W. Scott-Brown's Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery: 1: Basic sciences, endocrine surgery, rhinology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018.

- 9.Mustafa SS. Steroid-induced secondary immune deficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023;130(6):713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanon AK, Assouan C, Anzouan-Kacou E, N’guessan D, Salami A, Boni S, et al. Infection invasive à champignon filamenteux pseudotumorale du sinus maxillaire à Abidjan. J Mycol Med. 2017;27(2):285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poto R, Pelaia C, di Salvatore A, Saleh H, Scadding GW, Varricchi G. Imaging of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in the era of biological therapies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;24(4):243–250. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne SJ, Mitzner R, Kunchala S, Roland L, McGinn JD. Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: a 15-year experience with 41 patients. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:759–764. doi: 10.1177/0194599815627786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolsi N, Zrig A, Chouchene H, Bouatay R, Harrathi K, Koubaa J. Imaging of complicated frontal sinusitis. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:209. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.26.209.11817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vatin L, Vitte J, Radulesco T, Morvan JB, Del Grande J, Varoquaux A, et al. New tools for preoperative diagnosis of allergic fungalsinusitis? A prospective study about 71 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2019;44(1):91–96. doi: 10.1111/coa.13243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun JJ, et de Blay F. Aspergillus et rhinosinusites : de l’infection fongique à la sinusite fongique allergique. Rev Fr Allergol. 2017;58(3):194–196. doi: 10.1016/j.reval.2018.02.184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh V. Fungalrhinosinusitis: unravelling the disease spectrum. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2019;18:164–179. doi: 10.1007/s12663-018-01182-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahfoudhi M, Khamassi K. Sinusite aspergillaire invasive chez un diabétique. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:279. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.279.6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouayad N, Oubelkacem N, Bono W, Masbah O, Bouhafa T, Elmazghi A, et al. Lymphome T/NK nasal: à propos de deux cas rares. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:141. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.141.7721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zegmout A, Rouihi A, Boucaid A, Amchich Y, Souhi H, El Ouazzani H, et al. Gestion de la rechute d’une tuberculose naso-sinusienne primaire. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:84. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.84.13067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youssef D, Mohamed MT, Chihani M, El Alami J, Bouaity B, Ammar H. Les tumeurs malignes naso-sinusiennes: à propos de 32 cas et revues de la littérature. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:342. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.22.342.8220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]