Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (M-HLH) is a rare, life-threatening, and poorly understood complication of cancer characterized by profound immune dysregulation, the sequelae of which includes fevers, pancytopenia, coagulopathy, and multiorgan failure.1-5 M-HLH carries a grim prognosis and frontline management is geared towards addressing both the underlying malignancy as well as the inflammatory milieu, and frequently incorporates agents commonly used for treating both primary and secondary HLH including etoposide and high-dose steroids.2-5 Other immunosuppressive agents, such as ruxolitinib and anakinra, have been described for treating M-HLH, but robust single-agent efficacy data remain limited.6,7

Emapalumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralizes interferon-gamma (IFNγ).8 It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for adults and children with relapsed or refractory primary HLH, and the growing body of evidence supporting the clinical benefit of emapalumab for treating various other etiologies of secondary HLH and hyperinflammatory states is encouraging.9-14

It is often problematic to differentiate between M-HLH responses and responses to the underlying malignancy itself as collectively these patients have diverse presenting features and clinical characteristics. Additionally, responses are frequently confounded by multiple M-HLH treatments utilized in combination or quick succession.3,4 Furthermore, determining the immediate cause of death, whether M-HLH-related, malignancy-related, infection-related, or other, poses numerous challenges. Here, we report the initial Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) experience with emapalumab in the treatment of adults with refractory M-HLH.

We first queried the MSKCC pharmacy database to identify adults treated with emapalumab from January 2019 through December 2022. We performed manual chart reviews to confirm an active malignancy diagnosis, and extracted the data required for diagnosing HLH according to the HLH-2004 criteria, and for investigating other relevant M-HLH biomarkers.1,3,15

The primary objectives were to determine M-HLH-specific overall survival and emapalumab-specific overall survival, defined from the start of frontline M-HLH-directed treatment (steroids and/or etoposide), and from the first emapalumab dose until death or last follow-up, respectively. Secondary objectives included describing the patients’ baseline clinical characteristics and M-HLH biomarker responses to emapalumab. M-HLH biomarkers - ferritin, soluble interleukin-2 receptor α (sIL2r), lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell counts, and liver function tests - were considered assessable only if abnormal at the time of initiating emapalumab treatment. M-HLH biomarker responses were assessed according to the definitions in the pivotal primary HLH registry trial, and measured at the time of best ferritin response.8 Best ferritin response was defined as the maximum reduction in ferritin assessed ≥72 hours after the first emapalumab dose. This definition was selected based on the dosing frequency of emapalumab in the registry trial.8 Because cytokine measurements were ordered at the discretion of the treating physician, best response for sIL2r was assessed independently at the closest time point to best ferritin response. This retrospective study was approved by the MSKCC institutional review board. Informed consent was not required.

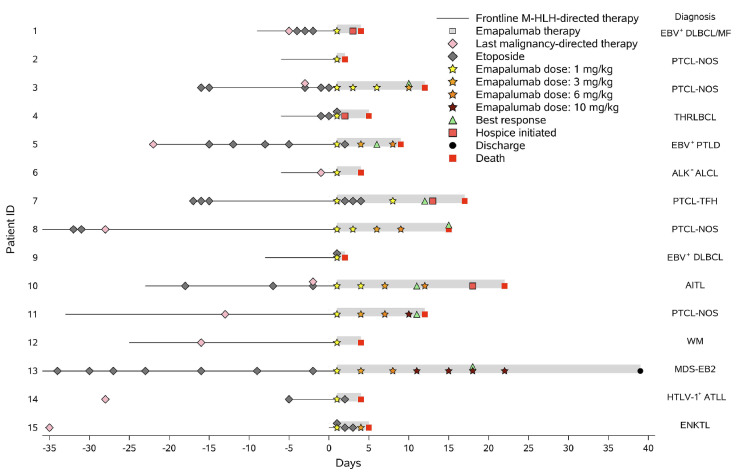

In total, 15 adult patients were treated with emapalumab for M-HLH. Their median age was 65 years (range, 19-73). All but one patient presented with M-HLH in the setting of relapsed malignancy, and most were heavily pretreated (Online Supplementary Table S1). At the start of emapalumab treatment, all patients had a markedly elevated ferritin (median 48,204 ng/mL; range, 6,007-372,503) and abnormal liver function tests, and most had pancytopenia. All patients assessed for sIL2r (N=13) had elevated levels, including above the upper limit reported (>20,000 pg/mL; N=7). Six patients had abnormal hepatic uptake on their positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan, two of whom underwent a biopsy that confirmed malignant involvement of the liver. All but three patients met the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria despite none undergoing natural killer cell activity testing, and five patients not having a bone marrow biopsy performed to determine evidence of hemophagocytosis (Online Supplementary Table S1).15 Patients received a median of two doses of emapalumab (range, 1-7), and all were hospitalized during treatment. All patients received high-dose steroids before and concurrently with emapalumab. Before their first emapalumab dose, nine (60%) patients received etoposide, and another two patients started etoposide concurrently with emapalumab (Figure 1, Online Supplementary Table S1). Three patients progressed on additional M-HLH-directed therapy prior to emapalumab (patient 5, tocilizumab x6 doses; patient 10, high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin; patient 11, alemtuzumab x8 doses). The median time from last malignancy-directed treatment (excluding steroids and/or etoposide alone) to first emapalumab dose was 8 days (range, not available-248).

Figure 1.

Swimmer plot summarizing the treatment course from day -35 prior to the first dose of emapalumab in 15 patients with malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. All patients received steroids from the start of malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (M-HLH) treatment and concurrently with emapalumab. The start of frontline M-HLH-directed therapy included initiation of steroids and/or etoposide. Last malignancy-directed therapy included any treatment other than steroids and/or etoposide alone. Last malignancy-directed therapies prior to day -35 are not shown. ID: identity; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MF: mycosis fungoides; PTCL-NOS: peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified; THRLBCL: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; PTLD: post-transplant (allogeneic stem cell transplant) lymphoproliferative disorder; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ALCL: anaplastic large cell lymphoma; PTCL-TFH: peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a follicular T-helper cell phenotype; AITL: angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; WM: Waldenström macroglobulinemia; MDS-EB2: myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts 2; HTLV-1: human T-lymphotropic virus type 1; ATLL: adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; ENKTL: extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.

The median M-HLH-specific and emapalumab-specific overall survival were 18 days (range, 4-292) and 4 days (range, 1-257), respectively (Figure 1). Seven patients died or initiated hospice care within 72 hours of their first emapalumab dose, seven patients lived longer than 7 days, and four patients lived longer than 14 days. One patient (patient 13) was discharged and was still alive at the time of data cutoff (257 days after the first emapalumab dose). The immediate precipitating cause of death was deemed secondary to M-HLH-associated organ failure complications in eight (53%) patients, directly related to organ failure complications from sepsis in three (20%) patients, and directly related to the progression of malignancy in three (20%) patients (Online Supplementary Table S1).

The eight patients who survived ≥72 hours after their first emapalumab dose were assessed for M-HLH biomarker responses (Figure 2). Seven (88%) showed a best ferritin response, at a median of 10 days (range, 5-17%) and three doses (range, 2-5), with a 64% median reduction in ferritin (range, 29-91%). Among these responders, those assessable for sIL2r (N=4), total bilirubin (N=5), aspartate aminotransferase (N=5), and alanine aminotransferase (N=3) had median reductions in these biomarkers of 35% (range, 32-62%), 26% (range, 17-46%), 86% (range, 15-93%), and 87% (range, 34-91%), respectively. Lymphocyte counts, neutrophil counts, hemoglobin concentrations, and platelet counts improved in only one patient (patient 13, Figure 3). Her hemoglobin concentration and platelet count before emapalumab were 9.3 g/dL and 15x109L, respectively; the values stabilized after emapalumab, and the patient remained persistently transfusion-independent at the time of the last follow-up (257 days after the first emapalumab dose). No patients achieved a best ferritin response of <2,000 ng/mL, which defined a complete response.8 Figure 3 depicts three patients who demonstrated sustained improvements in M-HLH biomarkers with emapalumab monotherapy after progression on etoposide and steroids. All three had both a >50% reduction as their best ferritin response, and a sustained improvement in sIL2r.8 Notably, none of these three patients was treated with concurrent malignancy-directed therapy after starting emapalumab. Before receiving emapalumab, seven patients displayed Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation, while eight had an undetectable EBV viral load. Among the former group, post-emapalumab EBV viral load decreased (N=2), remained above the upper limit clinically reported (>800,000 IU/mL; N=1), or was not reassessed (N=1), and three died <72 hours after emapalumab. Among the latter group, EBV remained undetectable for 9-21 days (N=3) or reactivated (7,313 IU/mL; N=1, day 7), and four patients died <72 hours after emapalumab.

Figure 2.

Percent change in malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis biomarkers for patients surviving ≥72 hours after their first emapalumab dose as determined at the time of best ferritin response. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (M-HLH) biomarker responses were not calculated if their corresponding values were not abnormal at the time of the first dose of emapalumab or if they were never evaluated and these represent the missing values. Patients 5 and 11 did not demonstrate a change in soluble interleukin-2 receptor level below the upper limit that is clinically reported (20,000 pg/mL) at any time point. sIL2r: soluble interleukin-2 receptor α; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

Five patients displayed cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation before receiving emapalumab, while nine had undetectable CMV. Among the former group, post-emapalumab CMV viral load decreased (N=1) or was not reassessed (N=1), and three patients died <72 hours after emapalumab. Among the latter group, CMV remained undetectable (N=4), or was not reassessed (N=2), and three patients died <72 hours after emapalumab. One patient was never assessed for CMV viral load. In total, nine (60%) patients were treated for other infections before or concurrently with emapalumab treatment.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal improvements in malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis biomarkers in three patients who demonstrated both a >50% reduction as their best ferritin response, and a sustained improvement in soluble interleukin-2 receptor α with emapalumab monotherapy after progression on etoposide and steroids. Percent change at each timepoint was calculated from day -6 before emapalumab for patients 3 and 8, and from day -7 before emapalumab for patient 13. AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; Tbili: total bilirubin; sIL2r: soluble interleukin-2 receptor α; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ALC: absolute lymphocyte count.

The limitations to this study include the variabilities in emapalumab dosing strategies as well as the variabilities in the patients’ underlying clinical characteristics, prior malignancy-directed treatments, and pre-emapalumab M-HLH-directed therapies. These differences contributed to the marked heterogeneity of our study population. Additionally, this cohort was enriched in patients with particularly aggressive malignancies as the majority were heavily pretreated for their cancer, had M-HLH refractory to etoposide, and had received prolonged treatment with high doses of steroids before starting emapalumab therapy, compounding the generally high mortality rate of M-HLH.1,3 The absence of monitoring serum C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) levels is another potential limitation of this study. CXCL9 is a specific and reliable surrogate of localized IFNγ activity, and reductions in serum CXCL9 levels are associated with responses to emapalumab when treating primary HLH and macrophage activation syndrome.8,12 Uniform assessments of serum CXCL9 levels in these patients may have identified those who had M-HLH that was primarily driven by IFNy, and may have guided emapalumab dosing strategies relative to improvements or progressions in other M-HLH biomarkers and clinical parameters. Nonetheless, further research in this context is needed before definitive conclusions can be made.

In summary, these data suggest that salvage emapalumab when administered with an arbitrary dosing approach for refractory M-HLH patients with multiply relapsed hematologic malignancies absent of effective concurrent malignancy-directed therapy is not highly beneficial. Nevertheless, seven out of the eight patients who survived ≥72 hours after the initiation of emapalumab therapy demonstrated notable improvements in M-HLH biomarkers, including patients who had progressed on etoposide and steroids and were not treated with any further malignancy-directed therapy. This suggests that IFNy may represent a therapeutic target to mitigate the hyperinflammatory state of M-HLH. A prospective study is warranted to determine whether utilizing emapalumab earlier in the M-HLH course, in synergy with malignancy-directed treatment, and with dosing strategies guided by serum CXCL9 levels, can improve the outcomes of M-HLH patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patients and caregivers. Editorial support was provided by Hannah Rice, MA, ELS at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Funding Statement

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center support grant (P30 CA00878), and The Nonna’s Garden Foundation.

Data-sharing statement

Requests for deidentified data that are not included in this article should be directed to the author for correspondence, William T. Johnson (johnsow3@mskcc.org).

References

- 1.Zoref-Lorenz A, Murakami J, Hofstetter L, et al. An improved index for diagnosis and mortality prediction in malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2022;139(7):1098-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Rosee P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamamyan GN, Kantarjian HM, Ning J, et al. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: relation to hemophagocytosis, characteristics, and outcomes. Cancer. 2016;122(18):2857-2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehmberg K, Nichols KE, Henter JI, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with malignancies. Haematologica. 2015;100(8):997-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bubik RJ, Barth DM, Hook C, et al. Clinical outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis treated with the HLH-04 protocol: a retrospective analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(7):1592-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trantham T, Auten J, Muluneh B, Van Deventer H. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a cautionary tale. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(4):1005-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naymagon L. Anakinra for the treatment of adult secondary HLH: a retrospective experience. Int J Hematol. 2022;116(6):947-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locatelli F, Jordan MB, Allen C, et al. Emapalumab in children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. New Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1811-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNerney KO, DiNofia AM, Teachey DT, Grupp SA, Maude SL. Potential role of IFNgamma inhibition in refractory cytokine release syndrome associated with CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3(2):90-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rainone M, Ngo D, Baird JH, et al. Interferon-gamma blockade in CAR T-cell therapy-associated macrophage activation syndrome/hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood Adv. 2023;7(4):533-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuelke MR, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, et al. Emapalumab for the treatment of refractory cytokine release syndrome in pediatric patients. Blood Adv. 2023;7(18):5603-5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Benedetti F, Grom AA, Brogan PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of emapalumab in macrophage activation syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(6):857-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunvarjee B, Bidgoli A, Madan RP, et al. Emapalumab as bridge to hematopoietic cell transplant for STAT1 gain-of-function mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(3):815-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triebwasser MP, Barrett DM, Bassiri H, et al. Combined use of emapalumab and ruxolitinib in a patient with refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis was safe and effective. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2021;68(7):e29026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Requests for deidentified data that are not included in this article should be directed to the author for correspondence, William T. Johnson (johnsow3@mskcc.org).