Abstract

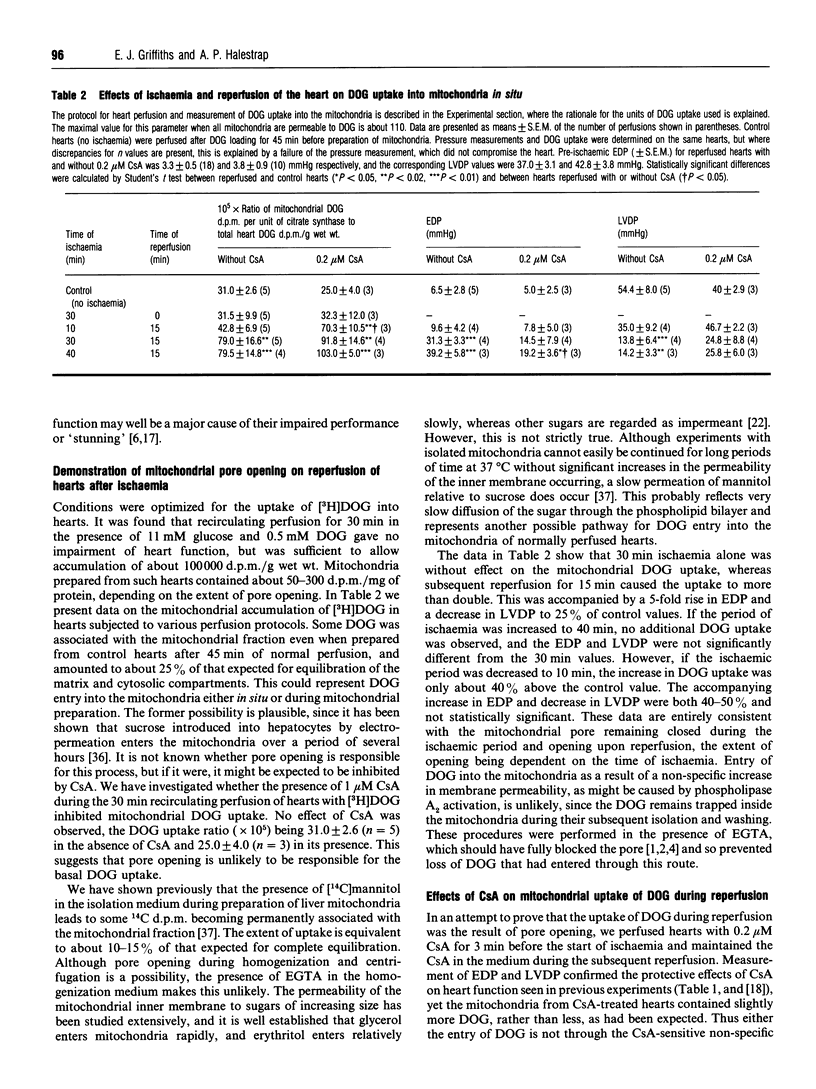

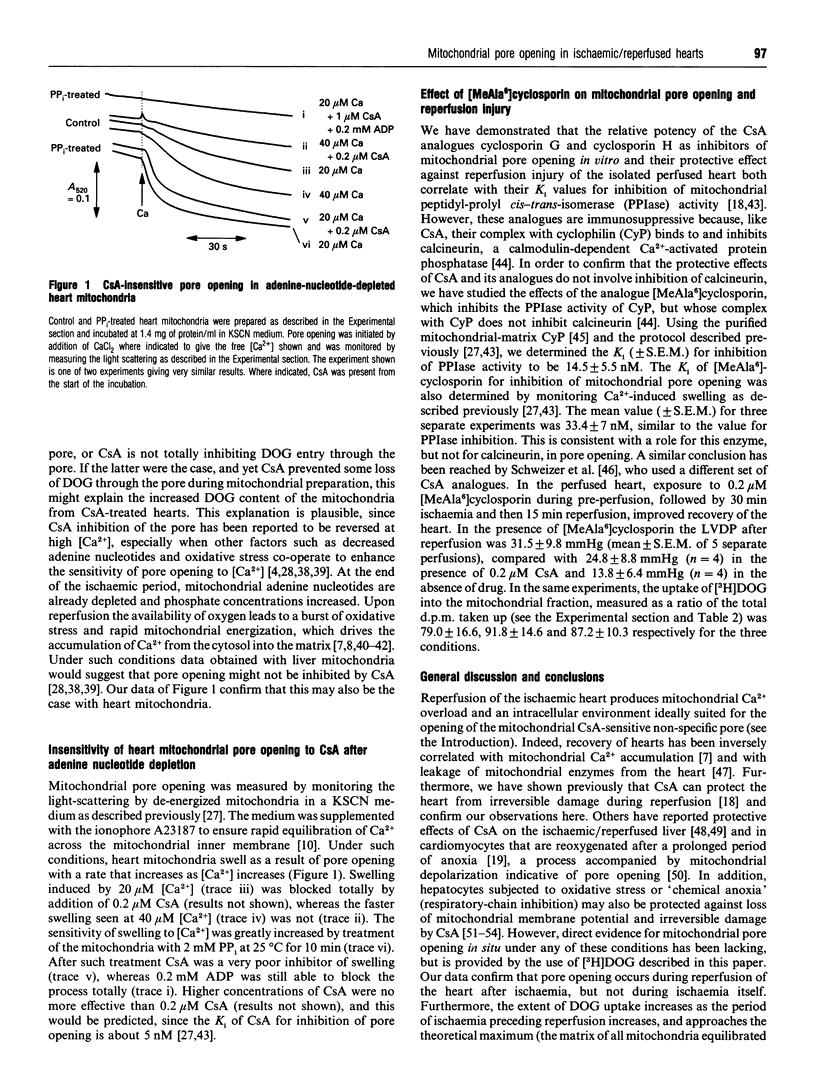

1. The yield of mitochondria isolated from perfused hearts subjected to 30 min ischaemia followed by 15 min reperfusion was significantly less than that for control hearts, and this was associated with a decrease in the rates of ADP-stimulated respiration. 2. The presence of 0.2 microM cyclosporin A (CsA) in the perfusion medium during ischaemia and reperfusion caused mitochondrial recovery to return to control values, but did not reverse the inhibition of respiration. 3. A technique has been devised to investigate whether the Ca(2+)-induced non-specific pore of the mitochondrial inner membrane opens during ischaemia and/or reperfusion of the isolated rat heart. The protocol involved loading the heart with 2-deoxy[3H]glucose ([3H]DOG), which will only enter mitochondria when the pore opens. Subsequent isolation of mitochondria demonstrated that [3H]DOG did not enter mitochondria during global isothermic ischaemia, but did enter during the reperfusion period. 4. The amount of [3H]DOG that entered mitochondria increased with the time of ischaemia, and reached a maximal value after 30-40 min of ischaemia. 5. CsA at 0.2 microM did not prevent [3H]DOG becoming associated with the mitochondria, but rather increased it; this was despite CsA having a protective effect on heart function similar to that shown previously [Griffiths and Halestrap (1993) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 25, 1461-1469]. 6. The non-immunosuppressive CsA analogue [MeAla6]cyclosporin was shown to have a similar Ki to CsA on purified mitochondrial peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase and mitochondrial pore opening, and also to have a similar protective effect against reperfusion injury. 7. Using isolated heart mitochondria, it was demonstrated that pore opening could become CsA-insensitive under conditions of adenine nucleotide depletion and high matrix [Ca2+] such as may occur during the initial phase of reperfusion. The apparent increase in mitochondrial [3H]DOG in the CsA-perfused hearts is explained by the ability of the drug to stabilize pore closure and so decrease the loss of [3H]DOG from the mitochondria during their preparation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen S. P., Darley-Usmar V. M., McCormack J. G., Stone D. Changes in mitochondrial matrix free calcium in perfused rat hearts subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993 Aug;25(8):949–958. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore by the proton electrochemical gradient. Evidence that the pore can be opened by membrane depolarization. J Biol Chem. 1992 May 5;267(13):8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J. M., Herman B., Lemasters J. J. Protection by acidotic pH against anoxia/reoxygenation injury to rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991 Sep 16;179(2):798–803. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91887-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekemeier K. M., Carpenter-Deyo L., Reed D. J., Pfeiffer D. R. Cyclosporin A protects hepatocytes subjected to high Ca2+ and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 1992 Jun 15;304(2-3):192–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80616-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekemeier K. M., Pfeiffer D. R. Cyclosporin A-sensitive and insensitive mechanisms produce the permeability transition in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Aug 30;163(1):561–566. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connern C. P., Halestrap A. P. Purification and N-terminal sequencing of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase from rat liver mitochondrial matrix reveals the existence of a distinct mitochondrial cyclophilin. Biochem J. 1992 Jun 1;284(Pt 2):381–385. doi: 10.1042/bj2840381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connern C. P., Halestrap A. P. Recruitment of mitochondrial cyclophilin to the mitochondrial inner membrane under conditions of oxidative stress that enhance the opening of a calcium-sensitive non-specific channel. Biochem J. 1994 Sep 1;302(Pt 2):321–324. doi: 10.1042/bj3020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M., Costi A. Kinetic evidence for a heart mitochondrial pore activated by Ca2+, inorganic phosphate and oxidative stress. A potential mechanism for mitochondrial dysfunction during cellular Ca2+ overload. Eur J Biochem. 1988 Dec 15;178(2):489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. J., Macleod B. A., Tabrizchi R., Walker M. J. An improved perfusion apparatus for small animal hearts. J Pharmacol Methods. 1986 Feb;15(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darley-Usmar V. M., Stone D., Smith D., Martin J. F. Mitochondria, oxygen and reperfusion damage. Ann Med. 1991;23(5):583–588. doi: 10.3109/07853899109150521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen M. R., McGuinness O., Brown L. A., Crompton M. On the involvement of a cyclosporin A sensitive mitochondrial pore in myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Oct;27(10):1790–1794. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace A. A., Kirschenlohr H. L., Metcalfe J. C., Smith G. A., Weissberg P. L., Cragoe E. J., Jr, Vandenberg J. I. Regulation of intracellular pH in the perfused heart by external HCO3- and Na(+)-H+ exchange. Am J Physiol. 1993 Jul;265(1 Pt 2):H289–H298. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.1.H289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. Further evidence that cyclosporin A protects mitochondria from calcium overload by inhibiting a matrix peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase. Implications for the immunosuppressive and toxic effects of cyclosporin. Biochem J. 1991 Mar 1;274(Pt 2):611–614. doi: 10.1042/bj2740611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. Protection by Cyclosporin A of ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage in isolated rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993 Dec;25(12):1461–1469. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. Pyrophosphate metabolism in the perfused heart and isolated heart mitochondria and its role in regulation of mitochondrial function by calcium. Biochem J. 1993 Mar 1;290(Pt 2):489–495. doi: 10.1042/bj2900489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Gunter K. K., Sheu S. S., Gavin C. E. Mitochondrial calcium transport: physiological and pathological relevance. Am J Physiol. 1994 Aug;267(2 Pt 1):C313–C339. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.2.C313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Pfeiffer D. R. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol. 1990 May;258(5 Pt 1):C755–C786. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.5.C755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigney M. C., Miyata H., Lakatta E. G., Stern M. D., Silverman H. S. Dependence of hypoxic cellular calcium loading on Na(+)-Ca2+ exchange. Circ Res. 1992 Sep;71(3):547–557. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. Calcium-dependent opening of a non-specific pore in the mitochondrial inner membrane is inhibited at pH values below 7. Implications for the protective effect of low pH against chemical and hypoxic cell damage. Biochem J. 1991 Sep 15;278(Pt 3):715–719. doi: 10.1042/bj2780715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P., Davidson A. M. Inhibition of Ca2(+)-induced large-amplitude swelling of liver and heart mitochondria by cyclosporin is probably caused by the inhibitor binding to mitochondrial-matrix peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase and preventing it interacting with the adenine nucleotide translocase. Biochem J. 1990 May 15;268(1):153–160. doi: 10.1042/bj2680153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P., Griffiths E. J., Connern C. P. Mitochondrial calcium handling and oxidative stress. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993 May;21(2):353–358. doi: 10.1042/bst0210353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism through changes in matrix volume. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994 May;22(2):522–529. doi: 10.1042/bst0220522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. The regulation of the matrix volume of mammalian mitochondria in vivo and in vitro and its role in the control of mitochondrial metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Mar 23;973(3):355–382. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. The regulation of the oxidation of fatty acids and other substrates in rat heart mitochondria by changes in the matrix volume induced by osmotic strength, valinomycin and Ca2+. Biochem J. 1987 May 15;244(1):159–164. doi: 10.1042/bj2440159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy L., Clark J. B., Darley-Usmar V. M., Smith D. R., Stone D. Reoxygenation-dependent decrease in mitochondrial NADH:CoQ reductase (Complex I) activity in the hypoxic/reoxygenated rat heart. Biochem J. 1991 Feb 15;274(Pt 1):133–137. doi: 10.1042/bj2740133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth R. A., Hunter D. R. The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. II. Nature of the Ca2+ trigger site. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979 Jul;195(2):460–467. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearse D. J., Garlick P. B., Humphrey S. M. Ischemic contracture of the myocardium: mechanisms and prevention. Am J Cardiol. 1977 Jun;39(7):986–993. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igbavboa U., Zwizinski C. W., Pfeiffer D. R. Release of mitochondrial matrix proteins through a Ca2+-requiring, cyclosporin-sensitive pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Jun 15;161(2):619–625. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imberti R., Nieminen A. L., Herman B., Lemasters J. J. Mitochondrial and glycolytic dysfunction in lethal injury to hepatocytes by t-butylhydroperoxide: protection by fructose, cyclosporin A and trifluoperazine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993 Apr;265(1):392–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Reimer K. A. Lethal myocardial ischemic injury. Am J Pathol. 1981 Feb;102(2):241–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass G. E., Juedes M. J., Orrenius S. Cyclosporin A protects hepatocytes against prooxidant-induced cell killing. A study on the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ cycling in cytotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992 Nov 17;44(10):1995–2003. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90102-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. FK506 and ciclosporin: molecular probes for studying intracellular signal transduction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993 May;14(5):182–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata H., Lakatta E. G., Stern M. D., Silverman H. S. Relation of mitochondrial and cytosolic free calcium to cardiac myocyte recovery after exposure to anoxia. Circ Res. 1992 Sep;71(3):605–613. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Steenbergen C., Levy L. A., Gabel S., London R. E. Measurement of cytosolic free calcium in perfused rat heart using TF-BAPTA. Am J Physiol. 1994 May;266(5 Pt 1):C1323–C1329. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. P., Tipton K. F. Effects of chronic ethanol feeding on rat liver mitochondrial energy metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992 Jun 23;43(12):2663–2667. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90158-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M., Takami H., Kaneko M., Nakano S., Matsuda H., Kurosawa K., Inoue T., Tagawa K. Mechanism of mitochondrial enzyme leakage during reoxygenation of the rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Jun;27(6):1116–1122. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.6.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novgorodov S. A., Gudz T. I., Brierley G. P., Pfeiffer D. R. Magnesium ion modulates the sensitivity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to cyclosporin A and ADP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994 Jun;311(2):219–228. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novgorodov S. A., Gudz T. I., Milgrom Y. M., Brierley G. P. The permeability transition in heart mitochondria is regulated synergistically by ADP and cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 1992 Aug 15;267(23):16274–16282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper H. M., Noll T., Siegmund B. Mitochondrial function in the oxygen depleted and reoxygenated myocardial cell. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Jan;28(1):1–15. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. C., Halestrap A. P. Transport of lactate and other monocarboxylates across mammalian plasma membranes. Am J Physiol. 1993 Apr;264(4 Pt 1):C761–C782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer M., Schlegel J., Baumgartner D., Richter C. Sensitivity of mitochondrial peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, pyridine nucleotide hydrolysis and Ca2+ release to cyclosporine A and related compounds. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993 Feb 9;45(3):641–646. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90138-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Kamiike W., Hatanaka N., Miyata M., Inoue T., Yoshida Y., Tagawa K., Matsuda H. Beneficial effects of cyclosporine on reoxygenation injury in hypoxic rat liver. Transplantation. 1994 Jun 15;57(11):1562–1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Kamiike W., Hatanaka N., Nishimura M., Miyata M., Inoue T., Yoshida Y., Tagawa K., Matsuda H. Enzyme release from mitochondria during reoxygenation of rat liver. Transplantation. 1994 Jan;57(1):144–148. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. W., Pastorino J. G., Attie A. M., Farber J. L. Protection by cyclosporin A of cultured hepatocytes from the toxic consequences of the loss of mitochondrial energization produced by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992 Aug 18;44(4):833–835. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90425-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolleshaug H., Seglen P. O. Autophagic-lysosomal and mitochondrial sequestration of [14C]sucrose. Density gradient distribution of sequestered radioactivity. Eur J Biochem. 1985 Dec 2;153(2):223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg J. I., Metcalfe J. C., Grace A. A. Intracellular pH recovery during respiratory acidosis in perfused hearts. Am J Physiol. 1994 Feb;266(2 Pt 1):C489–C497. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.2.C489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitch K., Hombroeckx A., Caucheteux D., Pouleur H., Hue L. Global ischaemia induces a biphasic response of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Anoxic pre-perfusion protects against ischaemic damage. Biochem J. 1992 Feb 1;281(Pt 3):709–715. doi: 10.1042/bj2810709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps D. E., Halestrap A. P. Rat liver mitochondria prepared in mannitol media demonstrate increased mitochondrial volumes compared with mitochondria prepared in sucrose media. Relationship to the effect of glucagon on mitochondrial function. Biochem J. 1984 Jul 1;221(1):147–152. doi: 10.1042/bj2210147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]