Abstract

Aims

Cardiac energy metabolism is perturbed in ischaemic heart failure and is characterized by a shift from mitochondrial oxidative metabolism to glycolysis. Notably, the failing heart relies more on ketones for energy than a healthy heart, an adaptive mechanism that improves the energy-starved status of the failing heart. However, whether this can be implemented therapeutically remains unknown. Therefore, our aim was to determine if increasing ketone delivery to the heart via a ketogenic diet can improve the outcomes of heart failure.

Methods and results

C57BL/6J male mice underwent either a sham surgery or permanent left anterior descending coronary artery ligation surgery to induce heart failure. After 2 weeks, mice were then treated with either a control diet or a ketogenic diet for 3 weeks. Transthoracic echocardiography was then carried out to assess in vivo cardiac function and structure. Finally, isolated working hearts from these mice were perfused with appropriately 3H or 14C labelled glucose (5 mM), palmitate (0.8 mM), and β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) (0.6 mM) to assess mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and glycolysis. Mice with heart failure exhibited a 56% drop in ejection fraction, which was not improved with a ketogenic diet feeding. Interestingly, mice fed a ketogenic diet had marked decreases in cardiac glucose oxidation rates. Despite increasing blood ketone levels, cardiac ketone oxidation rates did not increase, probably due to a decreased expression of key ketone oxidation enzymes. Furthermore, in mice on the ketogenic diet, no increase in overall cardiac energy production was observed, and instead, there was a shift to an increased reliance on fatty acid oxidation as a source of cardiac energy production. This resulted in a decrease in cardiac efficiency in heart failure mice fed a ketogenic diet.

Conclusion

We conclude that the ketogenic diet does not improve heart function in failing hearts, due to ketogenic diet-induced excessive fatty acid oxidation in the ischaemic heart and a decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation.

Keywords: Ischaemic heart failure, Ketogenic diet, Cardiac energy metabolism, Metabolism, Isolated working heart perfusion

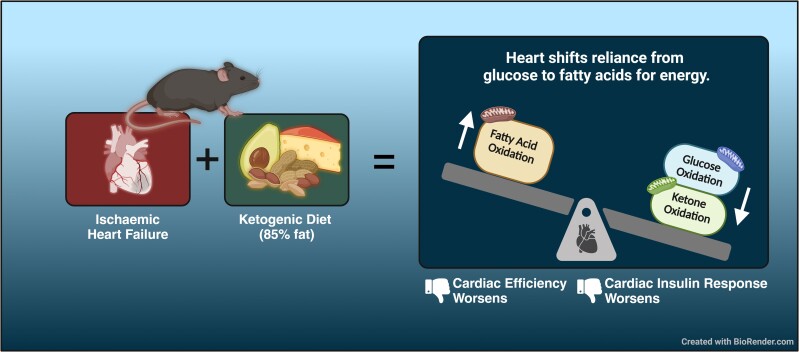

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Time of primary review: 20 days

See the editorial comment for this article ‘The ketogenic diet is unable to improve cardiac function in ischaemic heart failure: an unexpected result?', by C.M. Greco and E. Nisoli, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvae126.

1. Introduction

Heart failure is a major burden to society, affecting approximately 8% of all older adults.1 Alterations in cardiac energy metabolism contribute to the development and progression of heart failure.2,3 While the healthy heart is normally flexible as to which energy substrates it can use for energy production, the failing heart is metabolically inflexible as well as energy starved.3 The failing heart is characterized by a shift from mitochondrial oxidative metabolism to glycolysis for its energy.4 While controversy exists around whether fatty acid oxidation rates are increased, unchanged, or decreased in the setting of heart failure, there is more consensus with regard to glucose oxidation being decreased in heart failure.5

Ketone oxidation in heart failure has generated considerable interest in the last few years due to the observation that the failing heart relies more on ketones as a source of energy.6–8 This increase in ketone oxidation is thought to be an adaptive process that provides the ‘energy-starved’ failing heart with an additional source of energy.9–12 In support of this, we showed that increasing ketone oxidation in the failing heart can increase overall cardiac energy production while not significantly inhibiting glucose or fatty acid oxidation.13 Thus, we wanted to determine whether increasing energy production in the setting of ischaemic heart failure, via increasing ketone delivery to the heart, would be beneficial for cardiac energetics and function.

There are various methods to increase ketone delivery to the heart—ketone salts, ketone esters, medium-chain triacylglycerols, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, intermittent fasting, or the ketogenic diet.14,15 The ketogenic diet is a popular high-fat low-carbohydrate diet that causes blood ketone levels to increase due to the restriction of carbohydrates and decreased insulin signaling.16,17 The ketogenic diet is used primarily for the purposes of weight loss since carbohydrate restriction promotes mobilization of fat stores. However, the cardiovascular effects of a ketogenic diet remain unclear, with some studies showing an increased risk of insulin resistance while others show an increased risk of cardiovascular risk factors.18–20 On the other hand, studies have shown improvements in glycaemic and lipid control following consumption of a ketogenic diet.21,22 The uncertainty surrounding the benefits or risks of a ketogenic diet may be due to several factors including, but not limited to, the study model used (healthy, obesity, diabetes, and heart failure), the source of fatty acids being consumed (polyunsaturated fatty acids vs. saturated fatty acids), the daily caloric intake (isocaloric studies vs. non-isocaloric studies), or the duration of the diet. Moreover, the effects of a ketogenic diet on heart function and cardiac energy metabolism remain unclear due to mixed results in various rodent and human models.23–26 Therefore, whether the ketogenic diet can be implemented in the setting of heart failure to increase ketone delivery to the heart and confer cardiovascular benefits remains unknown. As such, we investigated the functional and energy metabolic effects of the ketogenic diet in a murine model of ischaemic heart failure.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal studies

All protocols involving mice were approved by the University of Alberta Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice received treatment and care abiding by the guidelines set out by the Canadian Council on Animal Care and Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. All mice were housed in a controlled environment with regulated temperature and a 12-h light and dark cycle. Additionally, mice had access to water and their food ad libitum. C57Blk/6J male mice, 8 weeks of age, were obtained from Jackson Labs and allowed to acclimatize in our facility for 4 weeks. At 12 weeks of age, mice were subjected to a left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery surgery to permanently ligate the LAD coronary artery and induce a myocardial infarction (MI), as described previously.27 Permanent ligation of the LAD coronary artery or a sham surgery was carried out in a blinded manner. After anaesthetization via intra-peritoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg/10 mg/kg), mice underwent a thoracotomy after which the LAD was ligated with a 6-0 silk suture. Sham mice similarly underwent a thoracotomy but the LAD was not ligated. Mice were then carefully inspected and provided with analgesia (subcutaneous injection of Metacam 1 mg/kg) over the course of the next 7 days while they recovered. After the mice recovered, they were subjected to further experiments.

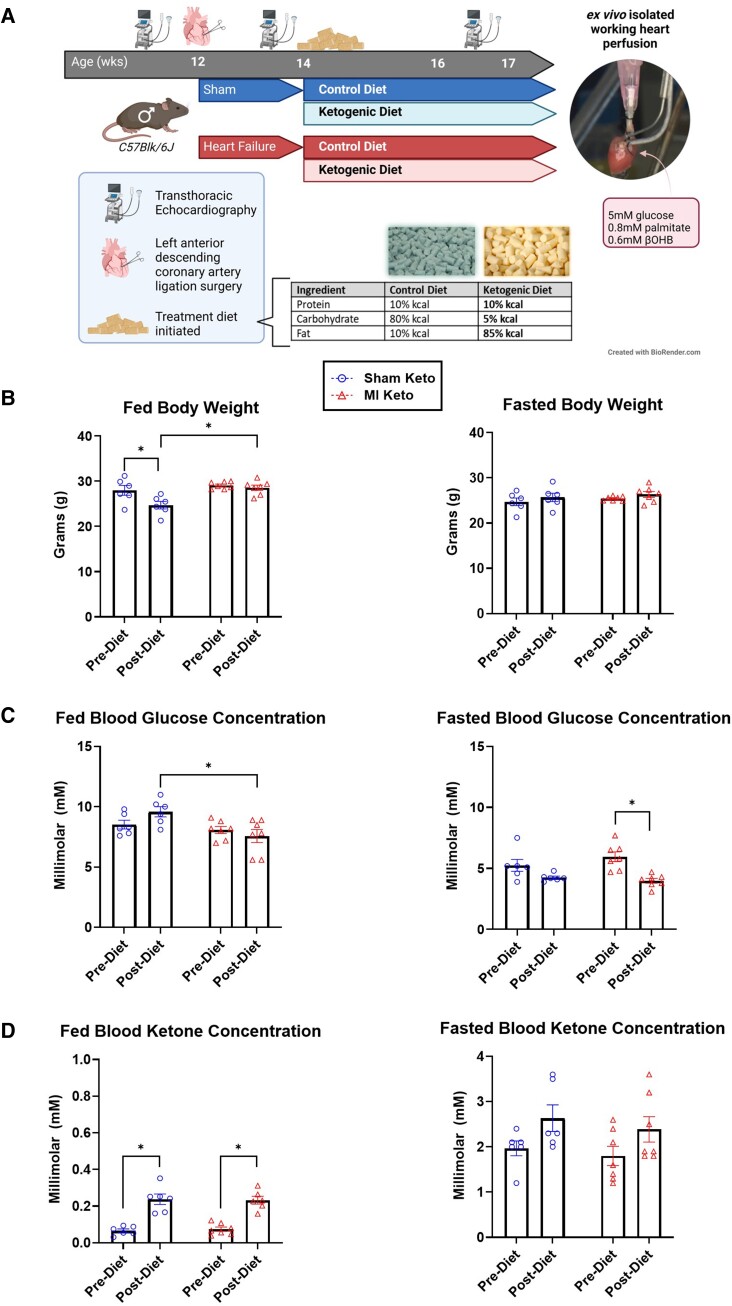

Mice were randomized 2 weeks after surgery to receive either a control diet (80% carbohydrates, 10% fat, and 10% protein) or a ketogenic diet (5% carbohydrates, 85% fat, and 10% protein) for 3 weeks. Specific details about the diet composition are provided in Supplementary material online, Table S1. During this period, transthoracic echocardiography was carried out to assess in vivo heart function pre-surgery (0 weeks), pre-diet (1 week), and post-diet (5 weeks). Blood glucose and ketone levels were also measured from tail whole blood using a Contour Next blood glucose meter (Bayer) and FreeStyle Precision Neo ketone meter (Abbott). Plasma ketone bodies were measured from plasma isolated from whole blood collected at the experiment’s endpoint using an in vitro assay (Wako Autokit Total Ketone Bodies). Five weeks after MI, mice were injected intra-peritoneally with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and hearts were excised and perfused as isolated working hearts to assess ex vivo cardiac function as well as the cardiac energy metabolic profile. Finally, hearts were snap frozen and used for biochemical analysis. Figure 1 outlines the experimental protocol followed for this study.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol and effect of the ketogenic diet on body weight, blood glucose, and blood ketones. (A) Experimental protocol. Please see methods for specific details. (B) Fed and fasted body weight of mice pre- and post-control/ketogenic diet implementation. (C) Fed and fasted blood glucose of mice pre- and post-control/ketogenic diet implementation. (D) Fed and fasted β-OHB levels of mice pre- and post-control/ketogenic diet implementation. Sham keto mice n = 6; MI keto mice n = 7. Values are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the pre-dietary implementation experimental group (two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test).

2.2. Transthoracic echocardiography

Prior to surgery and at 1 and 5 weeks after LAD ligation or sham surgery, mice were anaesthetized with 3% isoflurane prior to transthoracic echocardiography. A Vevo 3100 high-resolution imaging system was used with the 30 MHz transducer (RMV-707B, VisualSonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Specific details regarding the procedure used for transthoracic echocardiography have already been previously described.28

2.3. Isolated working heart perfusions

Five weeks after MI, mice were anesthetized with an intra-peritoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg), and once mice were unresponsive, hearts were excised and subjected to an isolated working heart perfusion. Isolated working hearts were perfused with a Krebs–Henseleit solution consisting of 2.5 mM Ca2+, 5 mM glucose, 0.8 mM palmitate (pre-bound to 3% albumin), and 600 µM β-OHB. Insulin (100 µU/mL) was added to the perfusate at 30 minutes of perfusion. Palmitate and β-OHB oxidation rates were measured by simultaneously collecting 3H2O and 14CO2 produced from the oxidation of [9,10-3H] palmitate and [3-14C] hydroxybutyrate, respectively, as described previously.29 Glycolysis and glucose and oxidation rates were measured by simultaneously measuring in a parallel series of hearts by collecting 3H2O and 14CO2 produced by [5-3H] glucose and [U-14C]glucose, respectively, as described previously.29 ATP production rates were calculated based on 31 ATP produced from each glucose oxidized, 2 ATP from each glucose passing through glycolysis, 104 moles of ATP produced from each molecule of palmitate oxidized, and 21.25 ATP from each molecule of β-OHB oxidized. Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) rates were calculated based on 2 acetyl CoA produced from each glucose molecule oxidized, 8 acetyl CoA produced from each molecule of palmitate oxidized, and 2 acetyl CoA from each molecule of β-OHB oxidized. Cardiac work was calculated from left ventricular developed pressure and cardiac output, as previously described.30,31 Myocardial O2 consumption was measured using in-line O2 probes in the left atrial inflow line and cannulated pulmonary artery.32 At the end of the 60-minute perfusion period, hearts were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80°C.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Between 10 and 15 mg of frozen myocardial tissue was homogenized in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40 (IGEPAL), 1% Tx-100, 10 mM sodium butyrate, 5 mM nicotinamide,1 µM trichostatin A (Sigma), protease, and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Next, cellular contents were extracted from homogenization lysate via centrifugation at 10 000 g for 15 min. Cell lysate was then subjected to a Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad) to determine protein concentration. Once protein concentration was determined, 25 μg of protein was loaded per gel lane in a 10-well 10% polyacrylamide gel that was used to resolve samples via sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After samples were resolved by their molecular weight, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane via a wet overnight transfer at 22 V. Membranes were then blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 3 h and probed with the following antibodies: anti-ACADL (Abcam 129711, 1/2000 dilution, abbreviated in paper as ‘LCAD’), anti-OXCT1 (Proteintech 12175-1-AP, 1/1000, abbreviated in paper as ‘SCOT’), anti-β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (BDH1) (Novus Biologicals NBP1-88673, 1/1000), anti-phospho-pyruvate dehydrogenase (P-PDH) (Millipore ABS204), anti-T-PDH (Cell Signaling 3205S), anti-P-Akt (Cell Signaling 9271S), anti-interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (Abcam ab9722), anti-NLRP3 (Cell Signaling 15101S), and anti-interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Thermo Fisher M620). Protein targets were normalized to anti-VDAC (Cell Signaling 4661S, 1/1000), and this was used as the loading control. Between targets, membranes were washed with a tris-buffered saline solution that was mixed with tween-20 and, if necessary, stripped with Restore™ Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific). Incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies was carried out following primary antibody incubation for about 1 h at room temperature, and visualization of the membrane was carried out with Western Lightning Plus-Enhanced Chemiluminescence Substrate (Perkin Elmer). Lastly, densitometric analysis was carried out with the software ImageJ and analysis was done with Microsoft Excel.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data are presented throughout the paper as mean ± SEM. Significant differences were calculated via two-way ANOVAs when comparing more than two means followed by a Tukey post hoc test. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism V9. Differences were deemed statistically significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The ketogenic diet does not improve in vivo or ex vivo cardiac function in mice with heart failure

Mice were subjected to a LAD coronary artery surgery to induce ischaemic heart failure (herein referred to as MI mice). Mice were then randomized to either receive a control diet or a ketogenic diet for 3 weeks (Figure 1A). Fed body weight was decreased in healthy mice fed a ketogenic diet but unchanged in mice that had heart failure (Figure 1B). Fasted body weight was unchanged (Figure 1B). In mice with heart failure, there was a significant decrease in fasted blood glucose levels (Figure 1C) and a statistically significant increase in fed ketone body levels in mice fed a ketogenic diet (Figure 1D).

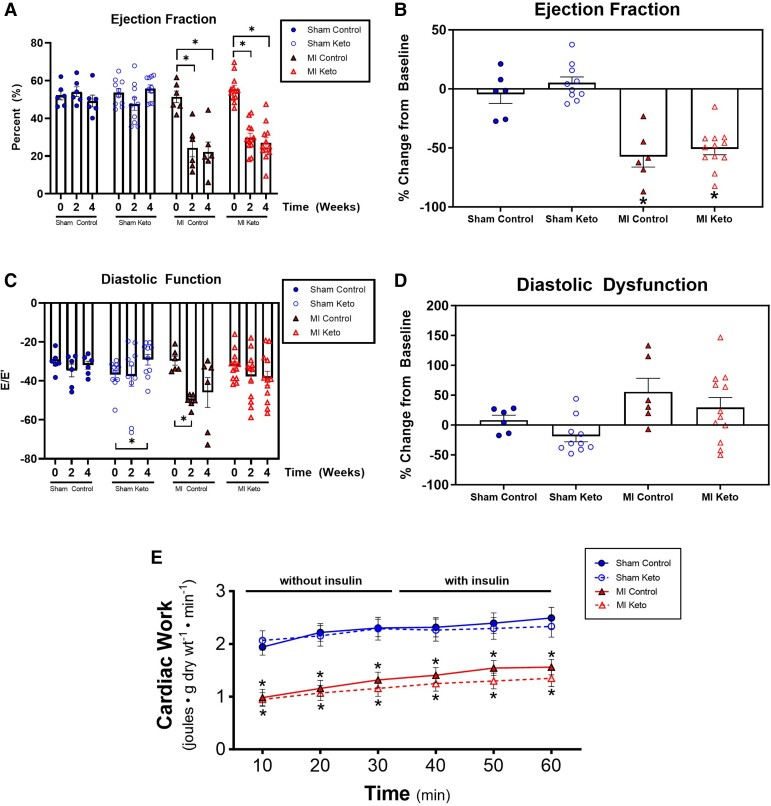

While the ketogenic diet had the predicted effects on body weight and blood ketones, this was not accompanied by an improvement in cardiac function in post-MI mice. As expected, MI control mice exhibited a 57% drop in ejection fraction (Figure 2A and B; Supplementary material online, Figure S1A) and a 55% increase in diastolic dysfunction (E/E′ ratio) by 4 weeks after MI (Figure 2C and D; Supplementary material online, Figure S1B) compared with sham control mice. However, this decrease in percent ejection fraction (%EF) was not different between MI mice fed a control diet vs. a ketogenic diet (Figure 2A and B), signifying that the ketogenic diet does not improve systolic function after MI. Diastolic dysfunction, assessed by using the ‘E-wave to E-prime wave’ ratio was also not different between MI mice on a control diet and MI mice on a ketogenic diet (Figure 2C and D), signifying that the ketogenic diet also does not improve diastolic dysfunction after MI. In addition to the in vivo echocardiographic assessment of heart function, ex vivo cardiac function of the mice hearts was also assessed in isolated working heart perfusions. Cardiac work dropped by 42% in MI control mice compared with sham control mice (Figure 2E), paralleling the decrease in %EF seen in vivo. However, mirroring the in vivo studies, the ketogenic diet had no effect on cardiac work in either sham mice or MI mice (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Ketogenic diet effects on in vivo and ex vivo cardiac function in post-MI mice. Transthoracic echocardiographic measurements of in vivo cardiac function: (A, B) ejection fraction and (C, D) diastolic function. Sham control mice n = 6; MI control mice n = 6; sham keto mice n = 10; MI keto mice n = 12. (E) Ex vivo measurement of cardiac function in isolated working hearts. Sham control mice n = 19; MI control mice n = 25; sham keto mice n = 11; MI keto mice n = 16. Values are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the respective sham group (one-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test for A–D; two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test for E).

3.2. The ketogenic diet does not increase cardiac ketone oxidation rates but instead increases the heart’s reliance on fatty acids for energy production

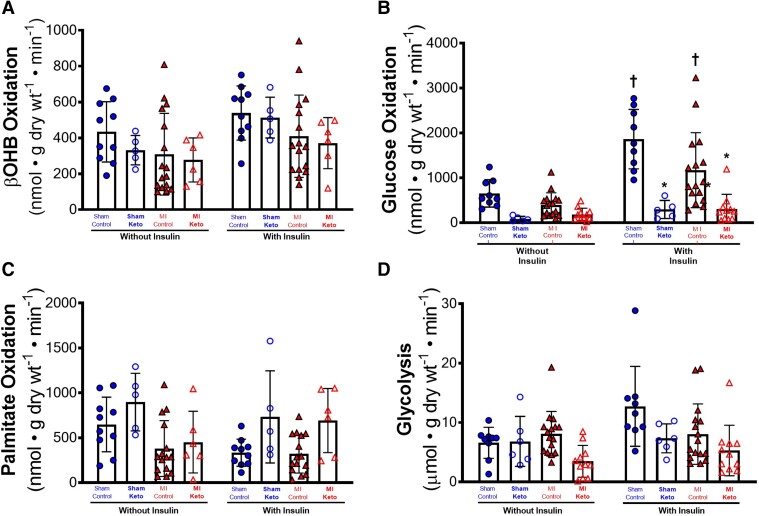

Because increasing cardiac ketone oxidation can benefit the failing heart, we determined what effect the ketogenic diet had on ketone oxidation rates in the post-MI mice. Similar to previous findings from our lab in mice subjected to pressure overload heart failure, absolute ketone body oxidation rates were unchanged between sham and MI control mice, regardless of whether insulin was present or not (Figure 3A). However, normalization of the absolute ketone body oxidation rates to cardiac work (to account for the significant drop in overall mitochondrial oxidative metabolism due to decreased cardiac work in the MI hearts) suggests that the ischaemic failing heart relies more on ketone metabolism for energy (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). Intriguingly, myocardial ketone body oxidation rates were not affected by the ketogenic diet, in either the Sham mice or the MI mice (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Ketogenic diet effects on β-OHB oxidation, glucose oxidation, fatty acid oxidation, and glycolysis in post-MI hearts. Cardiac energy metabolic rates were measured in isolated working hearts: (A) β-OHB oxidative rates without and with insulin (ketone body oxidation rates), (B) glucose oxidation rates without and with insulin, (C) palmitate oxidation rates without and with insulin, and (D) glycolytic rates without and with insulin. For A and C, sham control mice n = 10; MI control mice n = 16; sham keto mice n = 5; and MI keto mice n = 6. For B and D, sham control mice n = 9; MI control mice n = 16; sham keto mice n = 5; and MI keto mice n = 11. Values are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with respective control group, †P < 0.05 compared with the ‘without insulin’ group (two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test).

3.3. The ketogenic diet selectively decreases glucose oxidation in mice with heart failure

Confirming previous studies, insulin stimulates cardiac glucose oxidation in sham control mice (Figure 3B; Supplementary material online, Figure S2B). In MI control hearts, while trending to have lower glucose oxidation rates than sham control hearts, insulin also significantly increased glucose oxidation rates (Figure 3B). In contrast, sham and MI hearts from mice that consumed the ketogenic diet had significantly reduced glucose oxidation rates, regardless of whether insulin was added or not, suggesting a lack of cardiac insulin sensitivity in the ketogenic diet mice (Figure 3B). This dramatic drop in insulin stimulated glucose oxidation in MI keto mice hearts persisted when rates were normalized for cardiac work (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2B).

Palmitate oxidation rates, while trending to increase with the ketogenic diet in both sham and MI mice, did not reach statistical significance between any groups (Figure 3C). Similarly, glycolytic rates were not significantly different between the experimental groups (Figure 3D).

3.4. The ketogenic diet prevents the increase in BDH1 protein expression seen in MI hearts

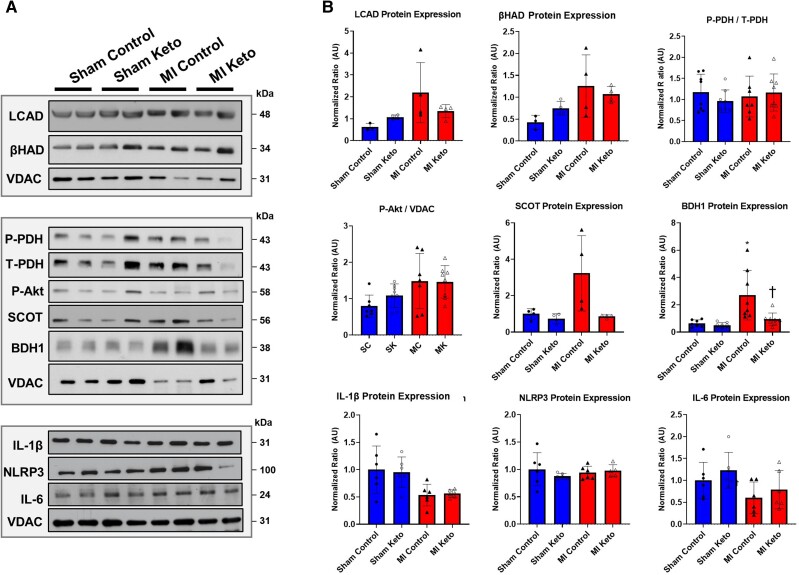

BDH1 protein expression was significantly increased in MI control hearts compared with sham control hearts, supporting our and others’ findings that the failing heart has an increased BDH1 expression that accompanies their increased reliance on ketone metabolism for energy. Consistent with a reduction in myocardial ketone body oxidation rates (Figure 3A), two important enzymes in the ketone oxidative pathway, BDH1 and succinyl-CoA-oxoacid transferase (SCOT), had decreased protein expression in MI mice on the ketogenic diet vs. MI mice on a control diet (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Ketogenic diet effects on cardiac protein expression of various metabolic and inflammatory targets in post-MI hearts: (A, B) LCAD, β-HAD, phospho-pyruvate dehydrogenase (p-PDH), serine/threonine protein kinase Akt (Akt), SCOT, BDH1, IL-1β, NACHT, LRR, PYD domains containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, and IL-6. Sham control mice n = 7; MI control mice n = 8; sham keto mice n = 8; and MI keto mice n = 8. Values are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with sham control (two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test).

The fatty acid oxidation enzymes long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) and β-hydroxyacyl-CoA-dehydrogenase (β-HAD) both trended to increase in MI hearts compared with sham hearts, although the ketogenic diet had no effect on their expression. Similarly, phosphorylation of the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt or PDH, the rate-limiting enzyme of glucose oxidation, was not significantly different between any of the experimental groups.

Recent studies have suggested that the protective effect of enhanced ketone oxidation in heart failure is partially due to modifying inflammation.33 Therefore, we examined the effect of the ketogenic diet feeding on several markers of inflammation, namely IL-1β, NACHT, LRR, and IL-6. However, we did not observe a significant effect of the ketogenic diet on any of these markers.

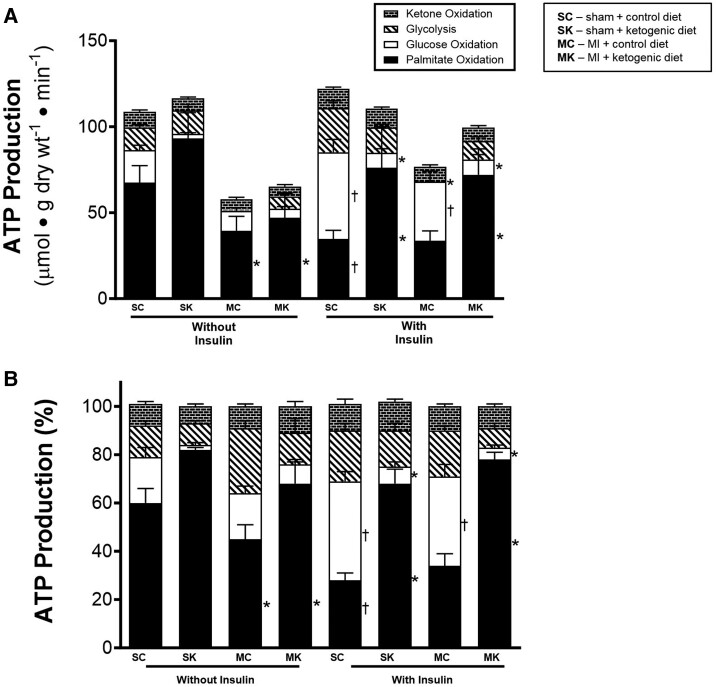

3.5. The ketogenic diet shift the heart’s ATP production to fatty acid oxidation at the expense of glucose oxidation

In the absence of insulin, control sham hearts relied primarily on fatty acid oxidation for their ATP production, followed by glucose oxidation, glycolysis, and ketone oxidation (Figure 5A and B). In the presence of insulin, glucose oxidation became the major source of ATP production in control sham hearts (Figure 5A and B). However, in sham + ketogenic diet hearts, fatty acid oxidation was the primary source of ATP production, even in the presence of insulin. This was primarily due to a dramatic decrease in ATP production from glucose oxidation.

Figure 5.

Ketogenic diet effects on cardiac ATP production rates in post-MI hearts. (A) Absolute ATP production rates coming from palmitate oxidation, glucose oxidation, ketone oxidation, and glycolysis without and with insulin. (B) Per cent contribution of palmitate oxidation, glucose oxidation, ketone oxidation, and glycolysis to total per cent of ATP production without and with insulin. For palmitate and ketone oxidation: sham control mice n = 10; MI control mice n = 16; sham keto mice n = 5; and MI keto mice n = 6. For glycolysis and glucose oxidation: sham control mice n = 9; MI control mice n = 16; sham keto mice n = 5; and MI keto mice n = 13. Values are the mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 compared with respective control group, †P < 0.05 compared with the ‘without insulin’ group (two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test).

In MI control hearts, overall ATP production was decreased both in the absence and presence of insulin (Figure 5A). The ketogenic diet did not have much effect on overall ATP production. However, in MI + keto diet mice, fatty acid oxidation was the major source of ATP production (Figure 5A and B), primarily at the expense of ATP production from glucose oxidation. This was particularly evident in hearts perfused in the presence of insulin.

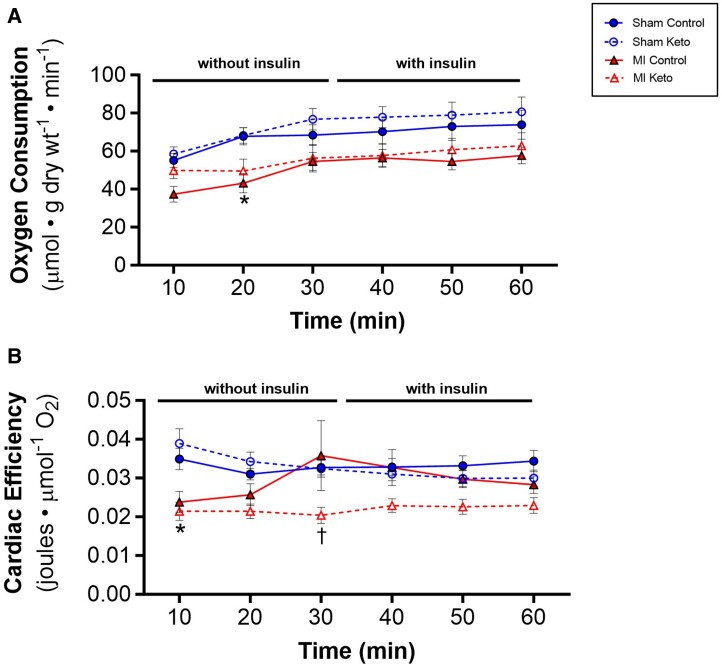

3.6. The ketogenic diet decreases cardiac efficiency

Oxidation of fatty acids is a less efficient (cardiac work/O2 consumed) source of energy than the oxidation of glucose. We, therefore, examined what effect the ketogenic diet had on cardiac efficiency in the MI hearts. To determine whether the effect of the ketogenic diet in switching the failing hearts from glucose oxidation to fatty acid oxidation affected cardiac efficiency, oxygen consumption was measured in the isolated working hearts. In sham hearts, the ketogenic diet had no effect on oxygen consumption (Figure 6A) or cardiac efficiency (Figure 6B) in sham hearts, regardless of whether insulin was present or absent. While MI control hearts had lower oxygen consumption rates than sham control hearts (Figure 6A), cardiac efficiency was not decreased (Figure 6B), primarily due to the lower cardiac work in the MI control hearts. However, the ketogenic diet did decrease cardiac efficiency in the MI hearts (Figure 6B), which is consistent with the increased reliance of these hearts on fatty acid oxidation (Figure 5A).

Figure 6.

Ketogenic diet on oxygen consumption and cardiac efficiency in post-MI hearts. (A) Oxygen consumption rates as measured in isolated working hearts. (B) Cardiac efficiency as determined by normalizing ex vivo cardiac work to oxygen consumption rates. Sham control mice n = 16; MI control mice n = 22; sham keto mice n = 11; and MI keto mice n = 12. Values are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the respective sham group, †P < 0.05 compared with respective control diet group (two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test).

4. Discussion

Considerable recent interest has focused on the potential of the ketogenic diet as a therapeutic approach to treat heart failure.34–36 This has been bolstered by the recent observations that increasing cardiac ketone supply and oxidation may be beneficial to the failing heart.9,37–42 However, studies demonstrating the efficacy of a ketogenic diet in lessening heart failure severity have produced mixed results.26,34,43,44 Here, we demonstrate that a ketogenic diet has no benefit in a murine model of ischaemic heart failure. We also report the first direct measurements of what effect a ketogenic diet has on cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Interestingly, the ketogenic diet did not increase cardiac ketone oxidation rates and, instead, blunted insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation rates, shifting the heart’s reliance on energy to fatty acid oxidation and consequently decreasing cardiac efficiency.

The healthy heart is metabolically flexible and able to dynamically draw different proportions of energy from fatty acids, glucose, ketones, lactate, and amino acids depending on the metabolic state of the body. This inherent ability to switch between fuel substrates differentiates a healthy heart from a failing heart. In the failing heart, a lack of understanding and confusion persists in the literature regarding the decisive metabolic changes that occur. The failing heart is metabolically inflexible and switches its reliance on energy from oxidative metabolic processes to glycolysis.5 As a consequence of mismatched ATP supply and demand, phosphocreatine, creatine, and ATP levels drop in the failing myocardium, leading to an ‘energy-starved’ state.3 Therefore, therapeutic strategies to restore the energy levels of the failing heart are of interest. Increasing ketone oxidation may be one such strategy,15,35 as well as stimulating glucose oxidation.4,45 Unfortunately, the ketogenic diet achieved neither of these goals. While the ketogenic diet did provide an additional supply of ketones for the failing heart, it also resulted in a down-regulation of myocardial ketolysis enzymes. Of importance, it also markedly decreased insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation and increased the reliance of the heart on fatty acid oxidation. This might be expected as a similar cardiac metabolic phenotype occurs in the presence of high-fat feeding.46–49 Therefore, our data suggest that strategies to increase ketone oxidation in the failing heart should ideally occur without shifting the balance of glucose and fatty acid oxidation in the heart.4,48,50–52

The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin, and specifically its ground-breaking clinical trial (EMPA-REG) catalysed a plethora of interest in ketone bodies and their potentially beneficial role in the setting of cardiovascular disease.53 Moreover, studies from our lab and others determined that the pressure overload hypertrophic heart relies more on ketones for energy, a process that is likely adaptive.6–9,11 We have also previously determined that ketones are readily metabolized by the healthy heart and can be used as extra source of fuel for the heart.13 Therefore, we initially hypothesized that increasing ketone delivery, via a ketogenic diet, to the failing heart would improve its energy-starved state and potentially improve cardiac function. However, while the ketogenic diet did increase ketone levels, this was not accompanied by changes in in vivo or ex vivo cardiac function in MI heart failure mice. This contrasts the findings of a study investigating the ketogenic diet in the setting of pressure overload hypertrophy.42 In a transverse aortic constriction model of heart failure, mice exhibited decreased cardiac hypertrophy and improved heart function.42 However, it is not clear what happened to cardiac energy metabolism in these mice. In addition, other studies have shown either little or no benefit of a ketogenic diet in similar models of TAC heart failure.40,54

In a model utilizing a cardiac-specific knockout of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC), mice developed dilated cardiomyopathy that was reversed after 3 weeks of a ketogenic diet.40 In a similar study in cardiac-specific MPC knockout mice, 15 weeks of a ketogenic diet reversed cardiac dysfunction induced by the lack of MPC.54 While it is not entirely clear why these findings contradict our findings, it could be due to the different model of heart failure being studied, as well as the fact that glucose oxidation would also be expected to already be markedly decreased in the MPC knockout mice. Therefore, the potential benefit of increasing ketone supply to the heart would not be offset by decreasing glucose oxidation in the heart.

We demonstrate that while a ketogenic diet increases blood ketone levels and ketone delivery to the heart, this does not correspond to an increase in ketone body oxidation in the heart. In fact, ketone oxidation rates were unchanged between control-fed and ketogenic-fed mice regardless of whether they had heart failure. Specifically, in MI mice fed a control diet, BDH1 protein expression was significantly increased compared with healthy sham mice fed a control diet. This supports previous findings published by our lab and others.6,7 However, implementation of the ketogenic diet decreased BDH1 protein expression in MI hearts. A possible explanation for this could be the compensatory decrease in BDH1 protein expression. Previous work by Wentz et al.55 has found that cardiac energy metabolism can adapt to a ketogenic nutritional state by promoting transcriptional suppression of ketolytic enzymes (specifically SCOT). We also found that the ketolytic enzyme SCOT trended to decrease in ketogenic diet-fed MI mice hearts vs. control diet-fed MI mice hearts though this did not reach statistical significance. As such, a compensatory transcriptional down-regulation of ketone metabolic enzymes may explain the absence of increased ketone body oxidative rates in our study.

Due to the nature of the ketogenic diet, circulating insulin levels remain low and it has been speculated that this could lead to improvements in glycaemic regulation.56 However, recent work from our lab has found that a ketogenic diet does not improve glucose homoeostasis or promote weight loss in obese mice isocalorically fed a ketogenic diet or control diet.57 Additionally, other animal models have found that a ketogenic diet can cause dyslipidaemia and glucose intolerance.58,59 Accordingly, at the level of the heart, we also found impaired cardiac insulin responsivity. While insulin can stimulate glucose oxidation in sham and MI hearts, hearts from mice fed a ketogenic diet had blunted glucose oxidation rates that did not respond to the addition of insulin to the heart. This suggests that there may be insulin resistance at the level of the heart, which may exacerbate the energy deficit seen in the failing heart, ultimately contributing to a decrease in cardiac efficiency.

It is interesting that fed glucose levels in MI mice (on a ketogenic diet) were significantly lower than sham mice (on a ketogenic diet) (Figure 1C). We would have expected increased glucose levels in MI mice compared with sham mice due to the correlation between blood glucose levels and heart failure.60 However, the observed difference between the two groups could be due to malnutrition (due to possible altered intestinal function, malabsorption, and neurohormonal changes in heart failure), which can provoke hypoglycaemia in heart failure.61

An increased reliance on fatty acid oxidation can decrease cardiac efficiency due to increased oxygen consumed per ATP molecule produced, reciprocal inhibition of glucose oxidation exacerbating the uncoupling of glycolysis and glucose oxidation, which increases proton levels and intracellular calcium and sodium. As such, ATP must be redirected to maintain ionic homoeostasis and, thus, cardiac efficiency decreases.62 This may explain why the ketogenic diet decreased cardiac efficiency in our study. By shifting the energy profile of the heart to rely more on fatty acid oxidation, the ketogenic diet could decrease cardiac efficiency.

5. Future studies

We acknowledge that intestinal microbiota are susceptible to changes from the presence of experimental heart failure as well as the implementation of our experimental diets.63 However, the way in which a ketogenic diet affects intestinal microbiota is not clearly defined. Studies have shown that a ketogenic diet can reduce microbiota diversity, but if weight loss is achieved with the ketogenic diet, long-term increases in microbiota diversity can be observed.64,65 Furthermore, previous work has found that the gut microbiota can regulate myocardial ketone body metabolism.66 As such, ketogenic diet-associated decreases in microbiota diversity may have contributed to the decreased ability for the heart to oxidize ketone bodies, potentially explaining why we did not observe increases in our ketone body oxidative rates in ketogenic diet-fed sham and MI mice hearts (Figure 3A). While we did not collect faecal samples from our mice, future studies that profile the gut microbiome of mice with heart failure fed a ketogenic diet would be interesting.

On a metabolite level, previous work has suggested that short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria is decreased in patients with heart failure.67,68 The ketogenic diet has also been associated with a significant reduction in SCFA production.69,70 SCFAs, one of the main metabolites produced by gut microbiota, have been shown to provide cardiometabolic benefits, and, specifically, the SCFA, butyric acid, has been shown to improve mitochondrial function and increase insulin sensitivity.71 Therefore, the reduction of SCFAs with the ketogenic diet could have contributed to cardiac metabolic dysfunction72 and, to some degree, promoted the blunting of insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation in hearts from mice fed a ketogenic diet (Figure 3B). Another gut microbiota-derived metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), has been correlated with cardiometabolic diseases and increased cardiovascular incidents.73 Elevated TMAO levels have been shown to accelerate pathological cardiac remodeling.74 Whether our ketogenic diet increases TMAO levels and contributes to the lack of cardiovascular benefits observed in our study would be interesting to investigate in future studies.34,75

Since we found evidence to suggest that the ketogenic diet promotes cardiac insulin resistance, future studies that more thoroughly investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the blunted insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation in mice on a ketogenic diet are warranted.

6. Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged in our study, which include the use of only male mice. Sex-specific differences unquestionably affect the regulation of cardiac energy metabolism so future studies will need to include female mice. Additionally, glycolytic rates are high in mice so future studies utilizing rats or mammals closer to humans would be ideal. As previously mentioned, there were discrepancies between our ketogenic diet and what others have used in their studies. A drawback to studying the ketogenic diet is the lack of diet standardization. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that alternate-day feeding of a ketogenic diet may be beneficial while continuous ketogenic diet feeding aggravates diastolic dysfunction in a model of pressure overload hypertrophy.76 Therefore, future studies that assess cardiac energy metabolism while also applying an alternate-day feeding model would be interesting to carry out. Additionally, we acknowledge that circulating levels of metabolites may not parallel its uptake into a specific organ, and therefore, future studies that measure uptake via quantification of cardiac levels of C4OH-carnitine and C2-carnitine are warranted to see whether ketogenic-fed mice have decreased cardiac ketone body uptake despite increased circulating ketone levels.

7. Conclusions

Taken together, we present the first study to directly assess ketone body metabolism in the setting of ischaemic heart failure and show that the ketogenic diet does not improve cardiac function and, instead, shifts the heart’s reliance to fatty acids for energy, blunts glucose oxidation rates, and ultimately decreases cardiac efficiency.

Translational perspective.

From a clinical perspective, our study helps direct therapeutic strategies to treat heart failure patients. Until now, whether an ischaemic heart failure patient could be put on a ketogenic diet was unclear. Although the ketogenic diet is strongly promoted for weight loss, whether this popular high-fat low-carbohydrate diet would translate to beneficial effects in heart failure remains topical. Based on our results, we do not recommend ischaemic heart failure be treated with a ketogenic diet since it promotes and exacerbates cardiac insulin resistance and, thus, worsens cardiac efficiency and heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Kim L Ho, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Qutuba G Karwi, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Faqi Wang, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Cory Wagg, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Liyan Zhang, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Sai Panidarapu, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Brandon Chen, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Simran Pherwani, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Amanda A Greenwell, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Gavin Y Oudit, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

John R Ussher, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Gary D Lopaschuk, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Authors’ contributions

K.L.H.’s role in this project included performing experiments alongside the writing of the manuscript. Q.K., L.Z., S.P., B.C., S.P., A.A.G., and F.W. were involved in the experimental aspects of the study. G.O., J.R.U., and G.D.L. were involved in the design of the study and the editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant as well as the Heart and Stroke Foundation to G.D.L. K.L.H. was supported by a CIHR Canadian Graduate Doctoral Scholarship, an Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Scholarship (Killam Trusts), and an Alberta Innovates Graduate Studentship (Alberta Innovates).

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Emmons-Bell S, Johnson C, Roth G. Prevalence, incidence and survival of heart failure: a systematic review. Heart 2022;108:1351–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bing RJ. The metabolism of the heart. Harvey Lect 1954;50:27–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neubauer S, Horn M, Cramer M, Harre K, Newell John B, Peters W, Pabst T, Ertl G, Hahn D, Ingwall Joanne S, Kochsiek K. Myocardial phosphocreatine-to-ATP ratio is a predictor of mortality in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1997;96:2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Tian R, Wende AR, Abel ED. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ Res 2021;128:1487–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karwi QG, Uddin GM, Ho KL, Lopaschuk GD. Loss of metabolic flexibility in the failing heart. Front Cardiovasc Med 2018;5:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ho KL, Zhang L, Wagg C, Al Batran R, Gopal K, Levasseur J, Leone T, Dyck JRB, Ussher JR, Muoio DM, Kelly DP, Lopaschuk GD. Increased ketone body oxidation provides additional energy for the failing heart without improving cardiac efficiency. Cardiovasc Res 2019;115:1606–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aubert G, Martin OJ, Horton JL, Lai L, Vega RB, Leone TC, Koves T, Gardell SJ, Krüger M, Hoppel CL, Lewandowski ED, Crawford PA, Muoio DM, Kelly DP. The failing heart relies on ketone bodies as a fuel. Circulation 2016;133:698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bedi KC Jr, Snyder NW, Brandimarto J, Aziz M, Mesaros C, Worth AJ, Wang LL, Javaheri A, Blair IA, Margulies KB, Rame JE. Evidence for intramyocardial disruption of lipid metabolism and increased myocardial ketone utilization in advanced human heart failure. Circulation 2016;133:706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horton JL, Davidson MT, Kurishima C, Vega RB, Powers JC, Matsuura TR, Petucci C, Lewandowski ED, Crawford PA, Muoio DM, Recchia FA, Kelly DP. The failing heart utilizes 3-hydroxybutyrate as a metabolic stress defense. JCI insight 2019;4:e124079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nielsen R, Møller N, Gormsen LC, Tolbod LP, Hansson NH, Sorensen J, Harms HJ, Frøkiær J, Eiskjaer H, Jespersen NR, Mellemkjaer S, Lassen TR, Pryds K, Bøtker HE, Wiggers H. Cardiovascular effects of treatment with the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate in chronic heart failure patients. Circulation 2019;139:2129–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uchihashi M, Hoshino A, Okawa Y, Ariyoshi M, Kaimoto S, Tateishi S, Ono K, Yamanaka R, Hato D, Fushimura Y, Honda S, Fukai K, Higuchi Y, Ogata T, Iwai-Kanai E, Matoba S. Cardiac-specific Bdh1 overexpression ameliorates oxidative stress and cardiac remodeling in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e004417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schugar RC, Moll AR, André d'Avignon D, Weinheimer CJ, Kovacs A, Crawford PA. Cardiomyocyte-specific deficiency of ketone body metabolism promotes accelerated pathological remodeling. Mol Metab 2014;3:754–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho KL, Karwi QG, Wagg C, Zhang L, Vo K, Altamimi T, Uddin GM, Ussher JR, Lopaschuk GD. Ketones can become the major fuel source for the heart but do not increase cardiac efficiency. Cardiovasc Res 2021:117:1178–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yurista SR, Chong CR, Badimon JJ, Kelly DP, de Boer RA, Westenbrink BD. Therapeutic potential of ketone bodies for patients with cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1660–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Ho KL, Pherwani S, Ketema EB. Ketone metabolism in the failing heart. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2020;1865:158813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilder R. The effect of ketonemia on the course of epilepsy. Mayo Clin Bulletin 1921;2:307–308. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wheless JW. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2008;49:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grandl G, Straub L, Rudigier C, Arnold M, Wueest S, Konrad D, Wolfrum C. Short-term feeding of a ketogenic diet induces more severe hepatic insulin resistance than an obesogenic high-fat diet. J Physiol (Lond) 2018;596:4597–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jornayvaz FR, Jurczak MJ, Lee HY, Birkenfeld AL, Frederick DW, Zhang D, Zhang XM, Samuel VT, Shulman GI. A high-fat, ketogenic diet causes hepatic insulin resistance in mice, despite increasing energy expenditure and preventing weight gain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;299:E808–E815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long F, Bhatti MR, Kellenberger A, Sun W, Modica S, Höring M, Liebisch G, Krieger J-P, Wolfrum C, Challa TD. A low-carbohydrate diet induces hepatic insulin resistance and metabolic associated fatty liver disease in mice. Mol Metab 2023;69:101675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jani S, Da Eira D, Stefanovic M, Ceddia RB. The ketogenic diet prevents steatosis and insulin resistance by reducing lipogenesis, diacylglycerol accumulation and protein kinase C activity in male rat liver. J Physiol (Lond) 2022;600:4137–4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yuan X, Wang J, Yang S, Gao M, Cao L, Li X, Hong D, Tian S, Sun C. Effect of the ketogenic diet on glycemic control, insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism in patients with T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Diabetes 2020;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paoli A. Ketogenic diet for obesity: friend or foe? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:2092–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mansoor N, Vinknes KJ, Veierød MB, Retterstøl K. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr 2016;115:466–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, Keller U, Yancy WS Jr, Brehm BJ, Bucher HC. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kosinski C, Jornayvaz FR. Effects of ketogenic diets on cardiovascular risk factors: evidence from animal and human studies. Nutrients 2017;9:517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kassiri Z, Zhong J, Guo D, Basu R, Wang X, Liu PP, Scholey JW, Penninger JM, Oudit GY. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 accelerates maladaptive left ventricular remodeling in response to myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail 2009;2:446–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou YQ, Foster FS, Nieman BJ, Davidson L, Chen XJ, Henkelman RM. Comprehensive transthoracic cardiac imaging in mice using ultrasound biomicroscopy with anatomical confirmation by magnetic resonance imaging. Physiol Genomics 2004;18:232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopaschuk GD, Barr RL. Measurements of fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism in te isolated working rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem 1997;172:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larsen TS, Belke DD, Sas R, Giles WR, Severson DL, Lopaschuk GD, Tyberg JV. The isolated working mouse heart: methodological considerations. Pflügers Archiv 1999;437:979–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barr RL, Lopaschuk GD. Direct measurement of energy metabolism in the isolated working rat heart. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 1997;38:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karwi QG, Wagg CS, Altamimi TR, Uddin GM, Ho KL, Darwesh AM, Seubert JM, Lopaschuk GD. Insulin directly stimulates mitochondrial glucose oxidation in the heart. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020;19:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Byrne NJ, Soni S, Takahara S, Ferdaoussi M, Al Batran R, Darwesh AM, Levasseur JL, Beker D, Vos DY, Schmidt MA, Alam AS, Maayah ZH, Schertzer JD, Seubert JM, Ussher JR, Dyck JRB. Chronically elevating circulating ketones can reduce cardiac inflammation and blunt the development of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13:e006573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kodur N, Yurista S, Province V, Rueth E, Nguyen C, Tang WHW. Ketogenic diet in heart failure: fact or fiction? JACC Heart Fail 2023;11:838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsuura TR, Puchalska P, Crawford PA, Kelly DP. Ketones and the heart: metabolic principles and therapeutic implications. Circ Res 2023;132:882–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luong TV, Abild CB, Bangshaab M, Gormsen LC, Sondergaard E. Ketogenic diet and cardiac substrate metabolism. Nutrients 2022;14:1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yurista SR, Matsuura TR, Sillje HHW, Nijholt KT, McDaid KS, Shewale SV, Leone TC, Newman JC, Verdin E, van Veldhuisen DJ, de Boer RA, Kelly DP, Westenbrink BD. Ketone ester treatment improves cardiac function and reduces pathologic remodeling in preclinical models of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2021;14:e007684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gopalasingam N, Christensen KH, Berg Hansen K, Nielsen R, Johannsen M, Gormsen LC, Boedtkjer E, Norregaard R, Moller N, Wiggers H. Stimulation of the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 with the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate and niacin in patients with chronic heart failure: hemodynamic and metabolic effects. J Am Heart Assoc 2023;12:e029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yurista SR, Eder RA, Welsh A, Jiang W, Chen S, Foster AN, Mauskapf A, Tang WHW, Hucker WJ, Coll-Font J, Rosenzweig A, Nguyen CT. Ketone ester supplementation suppresses cardiac inflammation and improves cardiac energetics in a swine model of acute myocardial infarction. Metab Clin Exp 2023;145:155608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCommis KS, Kovacs A, Weinheimer CJ, Shew TM, Koves TR, Ilkayeva OR, Kamm DR, Pyles KD, King MT, Veech RL, DeBosch BJ, Muoio DM, Gross RW, Finck BN. Nutritional modulation of heart failure in mitochondrial pyruvate carrier–deficient mice. Nature Metabolism 2020;2:1232–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guo Y, Liu X, Li T, Zhao J, Yang Y, Yao Y, Wang L, Yang B, Ren G, Tan Y, Jiang S. Alternate-day ketogenic diet feeding protects against heart failure through preservation of ketogenesis in the liver. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022;2022:4253651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakamura M, Odanovic N, Nakada Y, Dohi S, Zhai P, Ivessa A, Yang Z, Abdellatif M, Sadoshima J. Dietary carbohydrates restriction inhibits the development of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2021:117:2365–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shemesh E, Chevli PA, Islam T, German CA, Otvos J, Yeboah J, Rodriguez F, deFilippi C, Lima JAC, Blaha M, Pandey A, Vaduganathan M, Shapiro MD. Circulating ketone bodies and cardiovascular outcomes: the MESA study. Eur Heart J 2023;44:1636–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dynka D, Kowalcze K, Charuta A, Paziewska A. The ketogenic diet and cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients 2023;15:3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karwi QG, Ho KL, Pherwani S, Ketema EB, Sun Q, Lopaschuk GD. Concurrent diabetes and heart failure: interplay and novel therapeutic approaches. Cardiovasc Res 2022;118:686–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alrob OA, Sankaralingam S, Ma C, Wagg CS, Fillmore N, Jaswal JS, Sack MN, Lehner R, Gupta MP, Michelakis ED, Padwal RS, Johnstone DE, Sharma AM, Lopaschuk GD. Obesity-induced lysine acetylation increases cardiac fatty acid oxidation and impairs insulin signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2014;103:485–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karwi QG, Zhang L, Altamimi TR, Wagg CS, Patel V, Uddin GM, Joerg AR, Padwal RS, Johnstone DE, Sharma A, Oudit GY, Lopaschuk GD. Weight loss enhances cardiac energy metabolism and function in heart failure associated with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019;21:1944–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ussher JR, Koves TR, Jaswal JS, Zhang L, Ilkayeva O, Dyck JR, Muoio DM, Lopaschuk GD. Insulin-stimulated cardiac glucose oxidation is increased in high-fat diet-induced obese mice lacking malonyl CoA decarboxylase. Diabetes 2009;58:1766–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fukushima A, Lopaschuk GD. Cardiac fatty acid oxidation in heart failure associated with obesity and diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1861:1525–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fillmore N, Lopaschuk GD. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an approach to treat heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1833:857–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fillmore N, Levasseur JL, Fukushima A, Wagg CS, Wang W, Dyck JRB, Lopaschuk GD. Uncoupling of glycolysis from glucose oxidation accompanies the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Molecular Medicine 2018;24:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhabyeyev P, Gandhi M, Mori J, Basu R, Kassiri Z, Clanachan A, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Pressure-overload-induced heart failure induces a selective reduction in glucose oxidation at physiological afterload. Cardiovasc Res 2013;97:676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang Y, Taufalele PV, Cochran JD, Robillard-Frayne I, Marx JM, Soto J, Rauckhorst AJ, Tayyari F, Pewa AD, Gray LR, Teesch LM, Puchalska P, Funari TR, McGlauflin R, Zimmerman K, Kutschke WJ, Cassier T, Hitchcock S, Lin K, Kato KM, Stueve JL, Haff L, Weiss RM, Cox JE, Rutter J, Taylor EB, Crawford PA, Lewandowski ED, Des Rosiers C, Abel ED. Mitochondrial pyruvate carriers are required for myocardial stress adaptation. Nat Metab 2020;2:1248–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wentz AE, d'Avignon DA, Weber ML, Cotter DG, Doherty JM, Kerns R, Nagarajan R, Reddy N, Sambandam N, Crawford PA. Adaptation of myocardial substrate metabolism to a ketogenic nutrient environment. J Biol Chem 2010;285:24447–24456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Locatelli CAA, Mulvihill EE. Islet health, hormone secretion, and insulin responsivity with low-carbohydrate feeding in diabetes. Metabolites 2020;10:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Greenwell AA, Saed CT, Tabatabaei Dakhili SA, Ho KL, Gopal K, Chan JSF, Kaczmar OO, Dyer SA, Eaton F, Lopaschuk GD, Al Batran R, Ussher JR. An isoproteic cocoa butter-based ketogenic diet fails to improve glucose homeostasis and promote weight loss in obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2022;323:E8–E20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ellenbroek JH, Dijck LV, Töns HA, Rabelink TJ, Carlotti F, Ballieux BEPB, Koning E. Long-term ketogenic diet causes glucose intolerance and reduced β- and α-cell mass but no weight loss in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014;306:E552–E558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kinzig KP, Honors MA, Hargrave SL. Insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance are altered by maintenance on a ketogenic diet. Endocrinology 2010;151:3105–3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barsheshet A, Garty M, Grossman E, Sandach A, Lewis BS, Gottlieb S, Shotan A, Behar S, Caspi A, Schwartz R, Tenenbaum A, Leor J. Admission blood glucose level and mortality among hospitalized nondiabetic patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Poznyak AV, Litvinova L, Poggio P, Sukhorukov VN, Orekhov AN. Effect of glucose levels on cardiovascular risk. Cells 2022;11:3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fillmore N, Lopaschuk G. Impact of fatty acid oxidation on cardiac efficiency. Heart Metab 2011;53:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paoli A, Mancin L, Bianco A, Thomas E, Mota JF, Piccini F. Ketogenic diet and microbiota: friends or enemies? Genes (Basel) 2019;10:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gutierrez-Repiso C, Hernandez-Garcia C, Garcia-Almeida JM, Bellido D, Martin-Nunez GM, Sanchez-Alcoholado L, Alcaide-Torres J, Sajoux I, Tinahones FJ, Moreno-Indias I. Effect of synbiotic supplementation in a very-low-calorie ketogenic diet on weight loss achievement and gut microbiota: a randomized controlled pilot study. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019;63:e1900167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reddel S, Putignani L, Del Chierico F. The impact of low-FODMAPs, gluten-free, and ketogenic diets on gut microbiota modulation in pathological conditions. Nutrients 2019;11:373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Crawford PA, Crowley JR, Sambandam N, Muegge BD, Costello EK, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Regulation of myocardial ketone body metabolism by the gut microbiota during nutrient deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:11276–11281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lupu VV, Adam Raileanu A, Mihai CM, Morariu ID, Lupu A, Starcea IM, Frasinariu OE, Mocanu A, Dragan F, Fotea S. The implication of the gut microbiome in heart failure. Cells 2023;12:1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sun W, Du D, Fu T, Han Y, Li P, Ju H. Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Front Microbiol 2021;12:813289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ferraris C, Meroni E, Casiraghi MC, Tagliabue A, De Giorgis V, Erba D. One month of classic therapeutic ketogenic diet decreases short chain fatty acids production in epileptic patients. Front Nutr 2021;8:613100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. He C, Wu Q, Hayashi N, Nakano F, Nakatsukasa E, Tsuduki T. Carbohydrate-restricted diet alters the gut microbiota, promotes senescence and shortens the life span in senescence-accelerated prone mice. J Nutr Biochem 2020;78:108326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 2009;58:1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nogal A, Valdes AM, Menni C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut Microbes 2021;13:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tang WH, Kitai T, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ Res 2017;120:1183–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Organ CL, Otsuka H, Bhushan S, Wang Z, Bradley J, Trivedi R, Polhemus DJ, Tang WH, Wu Y, Hazen SL, Lefer DJ. Choline diet and its gut microbe-derived metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide, exacerbate pressure overload-induced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e002314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tang WHW, Li DY, Hazen SL. Dietary metabolism, the gut microbiome, and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:137–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Guo Y, Zhang C, Shang FF, Luo M, You Y, Zhai Q, Xia Y, Suxin L. Ketogenic diet ameliorates cardiac dysfunction via balancing mitochondrial dynamics and inhibiting apoptosis in type 2 diabetic mice. Aging Dis 2020;11:229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.