Abstract

Introduction

Local recurrence of conjunctival melanoma (CM) is common after excision. Local radiotherapy is an effective adjuvant treatment option, and brachytherapy with ruthenium-106 (106Ru) is one such option. Thus, herein, we aimed to describe our experience with and the clinical results of post-excision adjuvant 106Ru plaque brachytherapy in patients with CM.

Methods

Nineteen patients (8 men and 11 women) received adjuvant brachytherapy with a 106Ru plaque after tumor excision. The mean adjuvant dose administered was 109 Gy (range, 80–134 Gy), and a depth of only 2.2 mm was targeted because the tumor had been excised. A full ophthalmological examination including visual acuity testing, slit-lamp examination, and indirect ophthalmoscopy was performed before therapy and at every postoperative follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 62 months (range, 2–144 months).

Results

Three patients developed a recurrence in a nontreated area, at either the conjunctiva bulbi or the conjunctiva tarsi. None of the patients developed a recurrence in the treated area. The local control rate was 84% (16/19).

Conclusion

106Ru plaque brachytherapy is an effective adjuvant treatment to minimize the risk of local recurrence after excision of a CM. Patients have to be followed up regularly and carefully for the early detection of recurrence.

Keywords: Conjunctival melanoma, Ruthenium-106, Brachytherapy, Recurrence rate

Introduction

Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva (conjunctival melanoma [CM]) is a very rare disease, accounting for 2% of all ocular malignancies. Two new cases per year are identified in a population of 8.4 million inhabitants [1]. In Denmark, the incidence was 0.50 (0.43–0.60) cases per 1 million inhabitants, and it has increased since then [2, 3].

CM can be differently pigmented among individuals, ranging from amelanotic to darkly pigmented. It can develop de novo or from primary acquired melanosis (PAM) or a pre-existing conjunctival nevus [4, 5]. PAM has now been differentiated into PAM with atypia and PAM without atypia. PAM with atypia is called conjunctival melanocytic intraepithelial neoplasia [6].

According to most studies, PAM demonstrates a balanced sex distribution and occurs in adults (mean age, 60 years) [7]. Clinically, a brownish-to-reddish pigmented tumor is usually seen at the corneal limbus, conjunctiva bulbi, conjunctiva fornices, conjunctiva tarsi, caruncula, or the plica semilunaris. The latter three are considered atypical [8]. CM is classified according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [9]. CM demonstrates a pronounced tendency to metastasize, with a rate of approximately 25% over 10 years. The regional preauricular and submandibular lymph nodes are primarily affected. Due to the blinking-induced mechanical alteration of the tumor, it can metastasize along the lacrimal ducts (shown in Fig. 1) [10].

Fig. 1.

a Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva with clear cell abrasion in the tear pool (b). c Magnified image of the area seen in (a) and (b).

The local recurrence rate is approximately 51% within 10 years, and the recurrence is often amelanotic [8]. The 10-year mortality is reportedly 13% [10].

The treatment of CM depends on the clinical findings. If it is located at the limbus, excision can be performed with a lamellar preparation of the sclera and cornea. Cryotherapy of the excision margins of the conjunctiva is possible. Subsequently, the wound edges are closed. In very severe forms of CM that involve the conjunctiva fornices, the tumor is excised and the defect is covered with an autologous conjunctival graft from the contralateral eye or oral mucosa. Amniotic membrane graft can also be used.

Because of the high recurrence rate of CM, adjuvant local chemotherapy with mitomycin C (MMC), interferon alfa administration, or radiotherapy can be considered. Radiotherapy can include X-ray surface irradiation, ruthenium-106 (106Ru) plaque irradiation, or strontium-90 (90Sr) plaque brachytherapy [6, 11–13].

Tumor recurrence is a risk factor for metastatic disease and may indicate the tumors’ inherently aggressive nature [10, 14]. Thus, the regional lymph nodes should be carefully examined clinically and radiologically via sonography and computed tomography. Furthermore, the ear, nose, and throat should be examined, as metastases can spread to the lacrimal ducts. Due to the normal lacrimal drainage process, metastases have been described up to the epiglottis [15, 16]. CM recurrences are associated with a poor prognosis [17], and the significance of a sentinel lymph node biopsy remains unclear.

As CM is a rare disease, only a few studies on its adjuvant treatment with 106Ru are available. In this study, we aimed to describe our experience with and the clinical results of post-excision adjuvant 106Ru plaque brachytherapy in patients with CM.

Methods

Patients with CM who were treated with adjuvant 106Ru brachytherapy between September 2011 and May 2023 were included in this retrospective study. A total of 19 patients were included. After tumor excision, a conjunctivoplasty (n = 16) or an oral mucosal transplantation (n = 3) with wound closure was performed. In 8 patients, the CM had been excised at clinics close to their hometown, and they had been referred to us after histological confirmation of malignancy. Two weeks later, adjuvant irradiation was administered using a 106Ru plaque. In all patients, under general anesthesia, the plaque was fixed transconjunctivally to the sclera at the site of excision using nonabsorbable monofilament sutures (shown in Fig. 2). Thus, the patients were hospitalized. In all the patients, a 106Ru plaque CCA from Eckert & Ziegler BEBIG® (Berlin, Germany) was used. The plaque is 15.3 mm in diameter with a half-life of 373.6 days. The irradiation was administered continuously and not in fractional doses. The beta radiation emitted by 106Ru/rhodium-106 has a limited range, providing a high dose to intraocular tumors up to 6 mm in thickness. Because all the tumors had been excised, a mean adjuvant dose of 109 Gy (range, 80–134 Gy) up to a depth of 2.2 mm was administered. The plaques were removed under local anesthesia.

Fig. 2.

Post-excision treatment of the site of CM with a 106Ru plaque.

According to the AJCC classification, 18 of the CMs were cT1 and one was cT2. After the irradiation, all patients were offered an adjuvant chemotherapy with MMC (0.04%) eyedrops. The drops were to be instilled four times a day for 1 week, followed by a break for 1 week, for a total of three cycles.

All patients underwent a full ophthalmological examination including visual acuity testing, slit-lamp examination, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and intraocular pressure measurement prior to therapy and at every postoperative follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 62 months (range, 2–144 months).

The patients consulted an otolaryngologist every 6 months for an examination of the local lymph nodes and the nasopharynx. This retrospective review of patient data did not require ethical approval in accordance with the national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients, before conducting the clinical examinations described above.

All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB® (version R2023b; The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages, and the continuous variables are presented as means and ranges. Visual acuity is documented as a decimal number. Time to local recurrence was calculated from the first day of brachytherapy.

Results

The study included 11 females and eight males, and the mean age of the patients was 65 years (range, 25–89 years). None of the patients developed a recurrence in the irradiated area. Three patients (16%) developed recurrences in nontreated areas (shown in Fig. 3). CM recurred at 7, 8, and 10 months after brachytherapy (Fig. 4). Two of these patients underwent tumor excision and irradiation using a 106Ru plaque. In the third patient, the tumor had recurred under the upper eyelid at the conjunctiva tarsi. Thus, after tumor excision, adjuvant MMC (0.04%) was administered. None of the patients developed a second recurrence. Of the 19 study participants offered adjuvant MMC therapy, only 11 (58%) agreed to the treatment. Two patients developed iris atrophy adjacent to the irradiated area, 1 patient developed a sectorial cataract at the treated area, and 1 patient developed a keratopathy. The mean visual acuity was 0.7 (range, 0.1–1.0) prior to brachytherapy and 0.7 (range, 0.01–1.0) at the last follow-up.

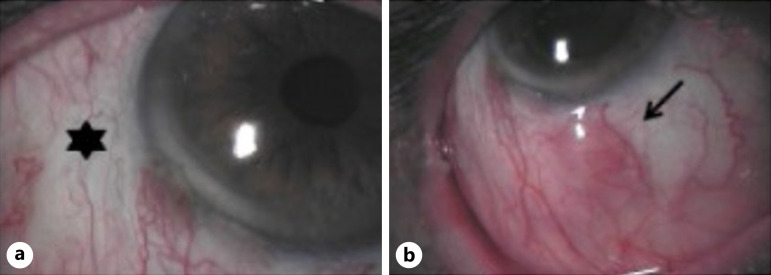

Fig. 3.

a Area after tumor excision and irradiation (*). b Non-pigmented histologically confirmed recurrence (arrow) adjacent to the irradiated area.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival curve with lower or upper bound.

Discussion

CM is a rare tumor associated with a high recurrence rate and high mortality. Often, the tumor recurs or new tumors develop. Thus, the appropriate amount of adjuvant therapy to reduce the recurrence frequency remains debatable. Evaluating the individual adjuvant therapy options is challenging because the tumor is rare. Furthermore, there are no large randomized studies that have compared the different adjuvant methods.

Beta rays are effective in patients with CM [12, 14, 18–25]. However, because of the low incidence of CM, only a few studies have reported the outcome of brachytherapy for CM. With 106Ru brachytherapy, the recurrence rate varies from 17% to 19% in the studies by Brouwer et al. [25] and Damato et al. [6]. With 90Sr brachytherapy, the recurrence rate varies from 18% to 60% [16, 19, 25, 26]. In our retrospective study, the recurrence rate was 16%. The involvement of the nonepibulbar conjunctiva is a major risk factor for recurrence [10, 14]. In our study, the bulbar conjunctiva was involved in 18 patients (cT1), and 1 patient had a cT2 tumor.

The radiation from 106Ru penetrates a soft tissue depth of approximately 6 mm, which is slightly more than the penetrative depth of 90Sr plaque. Because the plaque was retained in the eye for continuous irradiation, the patients had to be hospitalized. Suturing the 106Ru plaque to the eye reduced the inaccuracy that may have occurred if it were to be held manually on the area to be irradiated as it is using a 90Sr plaque. Furthermore, compared to the 90Sr plaque, the CCA 106Ru plaque has a larger contact surface area. Thus, it is safer, because a larger area of the conjunctiva is irradiated. A disadvantage of the 106Ru plaque is the slightly higher penetration depth. This is demonstrated by the fact that patients developed iris atrophy close to the treated area (n = 2), a keratopathy, and sectorial cataracta complicata (n = 1). However, the cataract was excised without complications, and the complications of irradiation were tolerable despite the severity of the disease. None of the patients exhibited radiation scars within the eye in the area of the choroid or retina. No patient developed rubeosis iridis, secondary glaucoma, or hypotension.

Surgical techniques for the removal of the affected conjunctiva with a safety margin, while avoiding intraoperative tumor cell seeding in healthy conjunctival regions, have been established. Several studies have demonstrated a significantly reduced recurrence rate in patients who underwent simultaneous cryocoagulation of the excised margins intraoperatively. Recent data have demonstrated that adjuvant radiotherapy and local chemotherapy are superior to cryocoagulation [6, 27]. If the tumor has spread to the corneal epithelium, it should be removed. Preparing the affected epithelium with absolute alcohol allows it to be removed as a whole. If deeper corneal structures are affected, lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty should be performed [6].

Some studies have demonstrated that treatment with MMC drops can reduce the risk of recurrence [26, 28–30]. After brachytherapy administration, we offered MMC therapy to each patient. However, only 11 patients (58%) accepted the offer. The 3 patients who had developed a recurrence had not received adjuvant MMC therapy. An advantage of MMC therapy is that it coats the entire conjunctival sac, including the folds. Thus, scattered and non-detectable atypical cells can be targeted. However, dry eye symptoms, trophic corneal changes, and occlusion of the lacrimal punctum can occasionally develop after treatment with MMC [31]. Apart from the development of dry eye symptoms and the need for artificial tears, we have not observed any other complications following MMC therapy [15, 16].

The number of study participants is not large enough to generate statistically significant results. However, the study results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the treatment. After brachytherapy with the 106Ru plaques, there was no recurrence in the irradiated area. Three patients (16%) developed a recurrence or new tumor in a non-irradiated area. Thus, the administration of local MMC therapy after irradiation to target atypical cells throughout the conjunctival sac should be considered and may require further investigation. This could further reduce the recurrence rate. However, a cumulative increase in the side effects is to be expected.

Statement of Ethics

This retrospective review of patient data did not require ethical approval in accordance with the national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

Treatment was administered by L.K., L.G., and C.K., and the irradiation dose was calculated by L.K., M.W., and I.F.C. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by L.G. and M.W. The first draft of the manuscript was written by L.G. All authors contributed to the study conception and design, commented on the previous versions of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, L.G. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- 1. Seregard S, Kock E. Conjunctival malignant melanoma in Sweden 1969−91. Acta Ophthalmol. 1992;70(3):289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Larsen AC. Conjunctival malignant melanoma in Denmark. Epidemiology, treatment and prognosis with special emphasis on tumorigenesis and genetic profile. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94(8):842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Triay E, Bergman L, Nilsson B, All-Ericsson C, Seregard S. Time trends in the incidence of conjunctival melanoma in Sweden. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(11):1524–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shields CL, Fasiuddin AF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Conjunctival Nevi: clinical features and natural course in 410 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(2):167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shields CL, Markowitz JS, Belinsky I, Schwartzstein H, George NS, Lally SE, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: outcomes based on tumor origin in 382 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(2):389–95.e952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Damato B, Coupland SE. Management of conjunctival melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9(9):1227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larsen AC, Dahmcke CM, Dahl C, Siersma VD, Toft PB, Coupland SE, et al. A retrospective review of conjunctival melanoma presentation, treatment, and outcome and an investigation of features associated with Braf mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(11):1295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buckman G, Jakobiec FA, Folberg R, McNally LM. Melanocytic nevi of the palpebral conjunctiva: an extremely rare location usually signifying melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(8):1053–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coupland SE, Barnhill R, Conway RM, et al. No title. Conjunctival melanoma. In: Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al., editors. Cancer staging manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017. p. 803–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gündüz K, Cater J, Mercado GV, Gross N, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(11):1497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shields CL, Shields JA, Armstrong T. Management of conjunctival and corneal melanoma with surgical excision, amniotic membrane allograft, and topical chemotherapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(4):576–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pk L. Beta irradiation of conjunctival melanomas. In: Trans ophthalmol soc UK; 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lommatzsch PK, Werschnik C. Das maligne Melanom der Bindehaut - Klinische übersicht mit empfehlungen zur diagnose, therapie und nachsorge. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2002;219(10):710–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Missotten GS, Keijser S, De Keizer RJW, De Wolff-Rouendaal D. Conjunctival melanoma in The Netherlands: a nationwide study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krause L, Mladenova A, Bechrakis NE, Kreusel KM, Plath T, Moser L, et al. [Treatment modalities for conjunctival melanoma]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2009;226(12):1012–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krause L, Ritter C, Wachtlin J, Kreusel KM, Höcht S, Foerster MH, et al. Rezidivhäufigkeit nach exzision von bindehautmelanomen und adjuvanter strontium-90-kontaktbestrahlung. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2008;225(07):649–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shields CL, Kaliki S, Al-Dahmash SA, Lally SE, Shields JA. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) clinical classification predicts conjunctival melanoma outcomes. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(5):313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Westekemper H, Meller D, Darawsha R, Scholz SL, Flühs D, Steuhl KP, et al. Operative Therapie und Bestrahlung konjunktivaler Melanome. Ophthalmologe. 2015;112(11):899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen VML, Papastefanou VP, Liu S, Stoker I, Hungerford JL. The use of strontium-90 beta radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment for conjunctival melanoma. J Oncol. 2013;2013:349162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lederman M, Jones CH. Beta irradiation of the conjunctival sac: description of a new applicator. Br J Radiol. 1966;39(467):867–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rasmussen KE. [Therapy of superficial eye diseases with the strontium 90 beta-ray applicator]. Nord Med. 1969;81(11):333–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paridaens ADA, Minassian DC, McCartney ACE, Hungerford JL. Prognostic factors in primary malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva: a clinicopathological study of 256 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78(4):252–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tuomaala S, Eskelin S, Tarkkanen A, Kivelä T. Population-based assessment of clinical characteristics predicting outcome of conjunctival melanoma in whites. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(11):3399–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jain P, Finger PT, Fili M, Damato B, Coupland SE, Heimann H, et al. Conjunctival melanoma treatment outcomes in 288 patients: a multicentre international data-sharing study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(10):1358–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brouwer NJ, Marinkovic M, Peters FP, Hulshof MCCM, Pieters BR, de Keizer RJW, et al. Management of conjunctival melanoma with local excision and adjuvant brachytherapy. Eye. 2021;35(2):490–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Damato B, Coupland SE. An audit of conjunctival melanoma treatment in Liverpool. Eye. 2009;23(4):801–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jakobiec FA, Brownstein S, Albert W, Schwarz F, Anderson R. The role of cryotherapy in the management of conjunctival melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(5):502–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Demirci H, Mccormick S, Finger P. Topical mitomycin chemotherapy for conjunctival malignant melanoma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia: clinical experience with histopathologic observations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(7):885–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurli M, Finger PT. Topical mitomycin chemotherapy for conjunctival malignant melanoma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia: 12 years’ experience. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243(11):1108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Westekemper H, Freistuehler M, Anastassiou G, Nareyeck G, Bornfeld N, Steuhl KP, et al. Chemosensitivity of conjunctival melanoma cell lines to single chemotherapeutic agents and combinations. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(4):591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khong JJ, Muecke J. Complications of mitomycin C therapy in 100 eyes with ocular surface neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(7):819–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, L.G. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.