Abstract

Background

Data regarding care access and outcomes in Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic (BIPOC/H) individuals is limited. This study evaluated care barriers, disease status, and outcomes among a diverse population of White/non-Hispanic (W/NH) and BIPOC/H inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients at a large U.S. health system.

Methods

An anonymous online survey was administered to adult IBD patients at Ochsner Health treated between Aug 2019 and Dec 2021. Collected data included symptoms, the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems and Barriers to Care surveys, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) via the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, the Medication Adherence Rating Scale-4, and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire. Medical record data examined healthcare resource utilization. Analyses compared W/NH and BIPOC/H via chi-square and t tests.

Results

Compared with their W/NH counterparts, BIPOC/H patients reported more difficulties accessing IBD specialists (26% vs 11%; P = .03), poor symptom control (35% vs 18%; P = .02), lower mean HRQOL (41 ± 14 vs 49 ± 13; P < .001), more negative impact on employment (50% vs 33%; P = .029), worse financial stability (53% vs 32%; P = .006), and more problems finding social/emotional support for IBD (64% vs 37%; P < .001). BIPOC/H patients utilized emergency department services more often (42% vs 22%; P = .004), reported higher concern scores related to IBD medication (17.1 vs 14.9; P = .001), and worried more about medication harm (19.5% vs 17.7%; P = .002). The survey response rate was 14%.

Conclusions

BIPOC/H patients with IBD had worse clinical disease, lower HRQOL scores, had more medication concerns, had less access to specialists, had less social and emotional support, and used emergency department services more often than W/NH patients.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, barriers to care, health disparities, social determinants of health

Key Messages.

What is known? Patients from historically marginalized populations face socioeconomic barriers to quality healthcare, with implicit biases and systemic racism affecting treatment and outcomes.

What is new here? Black/Indigenous/People of Color or Hispanic (BIPOC/H) patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) face more difficulties accessing specialists, have poorer symptom control, and have lower quality of life; they face more challenges in employment, financial stability, and finding IBD social/emotional support. BIPOC/H patients utilize emergency department services more frequently, and express higher medication concerns and worries about medication harm.

How can this study help patient care? These findings underscore disparities and outcomes for BIPOC/H individuals with IBD, emphasizing a need for targeted interventions and support.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises a group of chronic, recurrent inflammatory conditions that can affect any part of the digestive tract with painful symptoms impacting quality of life.1-3 Early epidemiologic studies, mainly with low representation from historically marginalized populations, concluded that the incidence and prevalence were higher in White individuals than in Black/Indigenous/People of Color or Hispanic (BIPOC/H) individuals.4-6 However, the incidence of IBD in BIPOC/H patients, particularly in Black people, has risen sharply over the past 3 decades.7 The prevalence of IBD in the Black population now approaches that of the non-Hispanic White population and others, with data suggesting that Black, Asian and Hispanic patients may have higher incidence of more severe disease, including perianal involvement and fistulas.8-12

However, the increased recognition of IBD prevalence in non-White patients has not resulted in more research into treatment, effectiveness, and outcomes in this population. Black individuals currently comprise approximately 14% of the United States population but comprise as low as 3% of people included in IBD-related randomized controlled trials and 1% of people included in real-world and outcome-based studies.7,13-15 Access to disease-modifying agents for treating IBD has been shown to vary by sociodemographics, potentially contributing to poorer outcomes and more severe disease in underserved populations.16,17 In the limited studies that have attempted to focus on IBD patients from historically marginalized communities, Black patients use fewer medications for IBD, particularly biologic agents.18 Racial disparities have also been observed in access to IBD specialist care and higher need for healthcare visits to the emergency department (ED).16,19,20 Poorer outcomes have also been observed in Black IBD patients, including longer lengths of hospitalization, higher rates of readmissions following hospitalizations and surgery, and lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL).19,20 Limited data currently exist examining patient perceived barriers to health care and outcomes in real-world clinical practice in diverse communities.

Ochsner Health is the largest nonprofit, academic healthcare system operating in Louisiana, serving New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Shreveport, Monroe, Lafayette, and other locations across Louisiana and Mississippi. Ochsner’s patients reflect the diversity of the communities it serves, with approximately 40% of its IBD patients being BIPOC/H individuals. This study was conducted to evaluate care barriers, clinical disease status, and outcomes among the diverse population of IBD patients.

Methods

This was a survey study supplemented by electronic medical record (EMR) review (see Table S1), which evaluated patient-reported care barriers, clinical disease status, HRQOL and medication attitudes, access, and adherence among a diverse population of patients with IBD treated at Ochsner. To be included in the study, patients had to be 18 years of age or older; have an IBD diagnosis (either Crohn’s disease [International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision (ICD-10) K50.90] or ulcerative colitis [ICD-10 K51.x]); be receiving IBD care at an Ochsner facility on December 1, 2021, with a history of IBD treatment beginning no later than August 1, 2019; and consent to complete surveys online.

A survey was created in English with input from a diverse Patient Engagement Research Council (PERC) which comprised 15 racially and ethnically diverse patients with IBD. The survey was designed to incorporate social determinants of health (SDOH) domains, IBD symptoms and severity, IBD-related HRQOL, access to care (including specialists and medications), a health literacy screener, medication adherence, and attitudes toward medication. The resulting instrument was reviewed with the PERC in 3 virtual focus groups and finalized with the investigators. The survey was designed for administration online with invitations being sent through Ochsner’s MyChart (Epic) portal to adult patients actively receiving care for IBD. To comply with Ochsner’s policies regarding minimization of patient abrasion, email invitations were only allowed to be sent once to patients who had opted in to receive email communication via MyChart. To avoid oversampling of W/NH respondents, this demographic was capped at 60% in the sampling plan. Responses to the survey were anonymous, and patients were compensated $50 for participating. This study was approved by the Ochsner institutional review board.

Data collected in the survey included sociodemographics, IBD history including age at diagnosis, and current IBD symptoms. Symptom assessment included abdominal pain, diarrhea, and a global impression of symptom control in the prior 7 days. Access to IBD-related health care was assessed via an instrument created for this study. It incorporated questions from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems21 and the Barriers to Care survey22 and was designed to understand geographical, psychosocial, and resource-related barriers to healthcare receipt in the prior 12 months. Questions were administered on a-5 point Likert scale related to problems accessing care ranging from 0 (no problem) to a 4 (major problem). HRQOL was assessed via the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) version 5.23 The SIBDQ measures physical, social, and emotional status in the prior 2 weeks on a 7-point scale from 1 (poor HRQOL) to 7 (optimum HRQOL) and includes a total score, and 4 subscales (systemic, social, bowel, and emotional functioning). The survey also included the Medication Adherence Rating Scale-4 (MARS-4),24,25 and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ)26 to assess patients’ feelings on medications. The MARS-4 is a 5-point Likert scale in which respondents indicate their degree of agreement with statements about medicine taking, ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never). Scores are summed to give a total score ranging from 4 to 20, with scores <16 classified as lower adherence. The BMQ is an 18-item instrument assessing beliefs about medications on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with statements and subscales regarding medication necessity, concerns about medications, overuse, and potential harm. Health literacy was assessed via the Single Item Literacy Screener, a 1-question instrument that queries patients on a 5-point scale (never to always) about their need for help to read material from a doctor or pharmacy, with a score of 2 (sometimes) or more often interpreted as lower literacy.27 EMR data were linked to patient surveys via an anonymized identifier to verify IBD diagnosis, to determine medications prescribed and imaging results in the prior 12 months (see Supplementary Appendix).

Statistical methods described BIPOC/H and W/NH patients’ survey responses and compared results in a bivariate fashion. Examined were sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as the number of observations or mean ± SD for continuous variables. For categorical variables, percentages of subjects for each of the categories and numbers were presented. We compared W/NH and BIPOC/H patients using chi-square statistics or Fisher’s exact tests for cell counts <5 with a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons for discrete variables and Student’s t tests to compare means between groups for continuous variables.

Results

Patient Characteristics

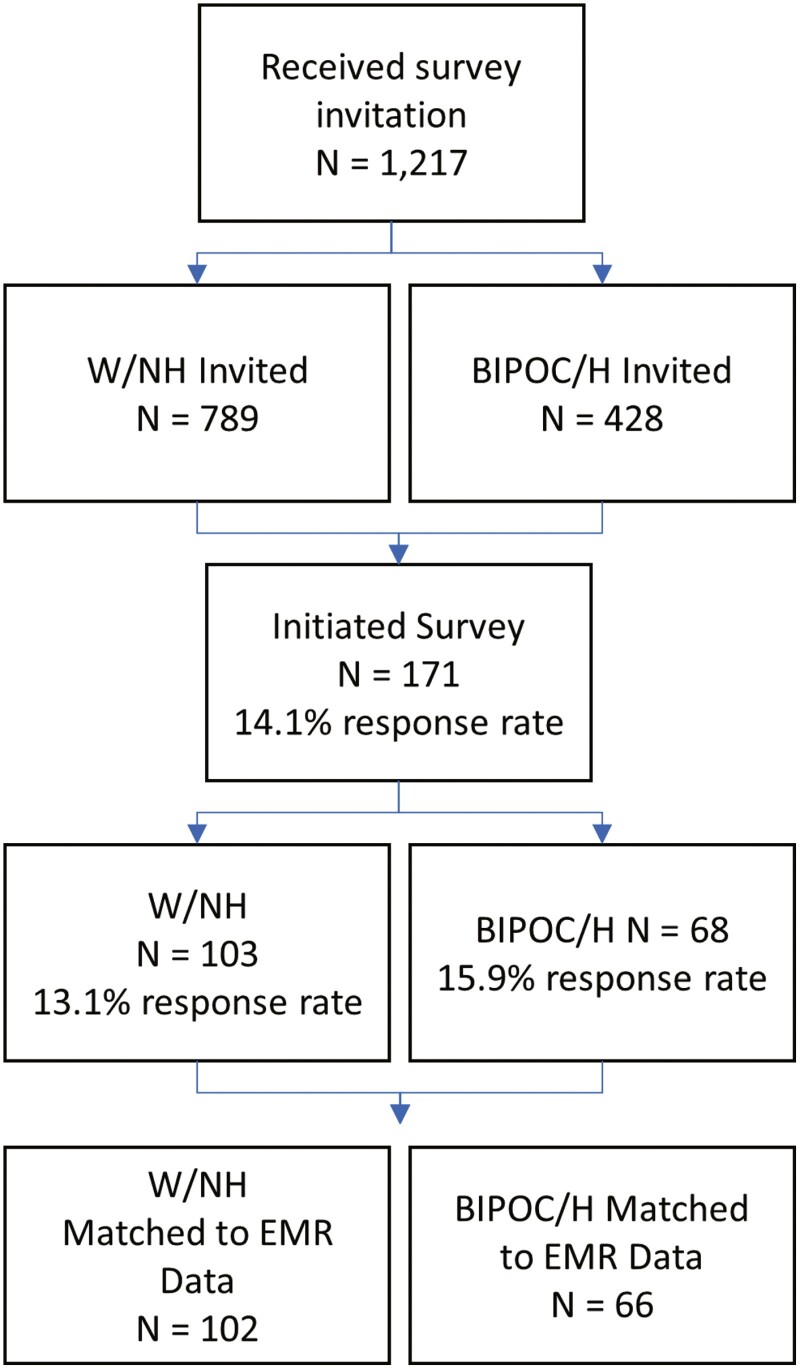

In total, 1217 patients (789 W/NH and 428 BIPOC/H) were invited to complete the survey. Of the entire patient population potentially eligible for the survey, 30% of invitees were coded in EMR data as BIPOC/H with a median age of 50 (range, 18 to >80) years, and 21% were insured by Medicaid. Of these 171 (14%) patients responded, with 168 completing all survey questions. Of all respondents, 40% self-identified as BIPOC/H, with 88% of non-White/non-Hispanic patients being Black. Of the total respondents, 53% had a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease confirmed in the EMR, 35% had ulcerative colitis, and 12% had both (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. BIPOC/H, Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic; EMR, electronic medical record; W/NH, White/non-Hispanic.

Compared with W/NH patients, BIPOC/H respondents were younger than W/NH patients (44 years of age vs 49 years of age; P = .03), were diagnosed more recently (15 years ago vs 19 years ago; P = .02), and were more often likely to be insured by Medicaid (43% vs 18%; P < .001), respectively. W/NH patients reported higher income and less financial strain related to their IBD. Groups were otherwise similar in terms of education, marital status, employment, and health literacy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographics.

| W/NH (n = 103)a | BIPOC/H (n = 68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49 ± 14 | 44 ± 13 | .03 |

| Years since first IBD diagnosis | 19 ± 13 | 15 ± 9 | .02 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 71 (69) | 48 (71) | .87 |

| Male | 32 (31) | 20 (29) | |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | — | 3 (4) | — |

| Asian | — | 1 (2) | — |

| Black or African American | — | 60 (88) | — |

| White | 103 (100) | 3 (4) | — |

| Other/multiracial | — | 1 (2) | — |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | — | 5 (7) | — |

| Not Hispanic | 103 (10) | 63 (93) | — |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current | 10 (10) | 7 (10) | .016 |

| Former | 39 (38) | 12 (18) | |

| Never | 54 (52) | 49 (72) | |

| Highest level of education | |||

| High school graduate or less | 20 (20) | 17 (25) | .11 |

| Some college or 2-y degree | 29 (28) | 24 (35) | |

| 4-y college graduate | 23 (22) | 9 (13) | |

| More than 4-y college degree | 31 (30) | 14 (21) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried (single, divorced, widowed) | 30 (29) | 30 (44) | .09 |

| Married/domestic partnership | 54 (52) | 25 (37) | |

| Widowed | 19 (18) | 13 (19) | |

| Type(s) of health insurance | |||

| HMO/PPO/private insurance | 66 (64) | 28 (41) | <.001 |

| Medicare | 21 (20) | 18 (27) | |

| Medicaid | 19 (18) | 29 (43) | |

| No insurance/self-pay | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Years with current insurer | 7 ± 7 | 10 ± 8 | .02 |

| Employment status | |||

| Full time | 55 (53) | 25 (37) | .20 |

| Part time/seasonal | 6 (6) | 6 (9) | |

| Self-employed | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Unemployed | 39 (38) | 35 (52) | |

| Income | |||

| $20 001-$40 000 | 21 (20) | 15 (12) | .001 |

| $40 001-$60 000 | 8 (8) | 5 (7) | |

| $60 001-$80 000 | 13 (13) | 4 (6) | |

| $80 001-$100 000 | 9 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| >$100 000 | 28 (28) | 8 (12) | |

| Prefer not to answer, but I have faced financial difficulties affecting my ability to get IBD healthcare | 11 (11) | 18 (27) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 13 (13) | 18 (30) | |

| SILS >2b | 4 (4) | 6 (9) | .19 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Abbreviations: BIPOC/H, Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SILS, Single Item Literacy Screener; W/NH, White/non-Hispanic.

a3 patients reporting Hispanic ethnicity reported race as White. These patients were analyzed in the BIPOC/H cohort.

bScores of 2 or higher indicate limited reading ability.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

With respect to patient-reported symptom control compared with their W/NH counterparts, BIPOC/H patients were more likely to report symptoms being not well controlled in the past 7 days (35% vs 18%; P = .02) and less likely to report bowel movements as normal in frequency (31% vs 53%; P = .01) vs W/NH patients. BIPOC/H patients also indicated more abdominal pain (66% vs 51%; P = .05). BIPOC/H patients reported a poorer quality of life via the SIBDQ, and global HRQOL scores were significantly lower in BIPOC/H patients (41.3 vs 49.4; P < .001), as well as in each subscale score: social HRQOL (9.1 vs 11.1; P < .001), bowel-related HRQOL (12.7 vs 15.8; P < .001), emotional-related HRQOL (12.5 vs 14.0; P = .041), and systemic impacts related HRQOL (7.6 vs 8.8; P = .019) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-reported IBD symptom control and IBD-related HRQOL.

| W/NH (n = 103) | BIPOC/H (n = 68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBD symptoms | |||

| Symptoms less than well controlled—past 7 d | 36 (35) | 12 (18) | .02 |

| Any abdominal pain—past 7 d | 52 (51) | 45 (66) | .05 |

| Bowel movement frequency—past 7 d | |||

| My normal amount | 55 (53) | 21 (31) | .01 |

| 1-2 stools a day more than normal | 15 (15) | 18 (27) | |

| 3-4 stools more than normal | 12 (12) | 15 (22) | |

| 5 or more stools more than normal | 13 (13) | 6 (9) | |

| I am constipated | 4 (4) | 7 (10) | |

| I have a colostomy | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Blood in stool—past 7 d | 21 (20) | 16 (24) | .63 |

| Received narcotic pain medication for IBD | 33 (32) | 36 (55) | .004 |

| IBD-related HRQOL (SIBDQ) | |||

| Total score | 49.4 ± 13.1 | 41.3 ± 14.2 | <.001 |

| Systemic subscale | 8.8 ± 3.3 | 7.6 ± 3.3 | .019 |

| Social subscale | 11.1 ± 3.2 | 9.1 ± 3.8 | <.001 |

| Bowel subscale | 15.8 ± 4.1 | 12.7 ± 4.6 | <.001 |

| Emotional subscale | 14.0 ± 4.3 | 12.5 ± 4.9 | .041 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: BIPOC/H, Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SIBDQ, Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; W/NH, White/non-Hispanic.

Barriers to Care

BIPOC/H patients were more likely than their W/NH counterparts to report having experienced barriers to IBD care in the prior 12 months. BIPOC/H patients reported significantly more difficulty accessing an IBD specialist (26% vs 11%; P = .03) and reported needing to utilize ED services for their IBD nearly twice as often than W/NH patients (42% vs 22%; P = .004). BIPOC/H patients reported markedly more difficulty accessing and receiving emotional support to deal with IBD (18% vs 42%; P < .001) and cited inadequate access to community support to deal with IBD significantly more often (29% vs 17%; P = .05). BIPOC/H patients reported higher negative impacts to the ability to work/attend school (49% vs 26%; P = .005) and pay bills (35% vs 20%; P = .048) related to their IBD. There were no reported differences in ability to access medication, having access to a clinician that listens to and respects them, and obtaining understandable explanations or care without delays when needed (Table 3). Although BIPOC/H patients reported more severe symptoms and disease activity, there were no significant differences in medications prescribed as documented in EMRs (Table S2).

Table 3.

Barriers to IBD-related care problems in the past 12 months.

| W/NH (n = 102) | BIPOC/H (n = 65) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problems receiving help dealing with emotions because of IBD | 19 (18) | 28 (42) | <.001 |

| Problems working or attending school because of IBD | 27 (26) | 32 (49) | .005 |

| Needed to seek care in the emergency department due to IBD | 22 (22) | 28 (42) | .004 |

| Problems seeing an IBD specialist | 11 (11) | 17 (26) | .03 |

| Problems finding community support for IBD | 17 (17) | 29 (29) | .05 |

| Problems paying bills because of IBD | 21 (20) | 23 (35) | .048 |

| Problems with transportation to IBD care | 3 (3) | 6 (9) | .08 |

| Problems having clinician that really listens to you | 18 (18) | 15 (23) | .42 |

| Problems getting explanations in ways you understand | 13 (13) | 10 (15) | .63 |

| Problems with delays accessing care | 22 (21) | 16 (24) | .66 |

| Problems feeling respected by providers | 11 (11) | 8 (12) | .81 |

| Problems accessing medications | 23 (22) | 15 (23) | .95 |

Values are n (%). Patients reported more than a slight problem on a 4-point Likert scale with 0 = no problem, 1 = slight problem, 2 = somewhat of a problem, and 3 = a major problem. Three patients declined to answer.

Abbreviations: BIPOC/H, Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; W/NH, White/non-Hispanic.

Medication Attitudes

With respect to medication attitudes as measured by the BMQ, in both the W/NH and BIPOC/H patient groups there were no differences in the belief that their IBD medication was necessary in supporting and maintaining current and future health. They equally endorsed statements that without their IBD medication they would be very ill. However, BIPOC/H patients reported higher mean scores on the medication concern subscale (3.4 vs 3.0; P = .001), including expressing more worry about long-term effects of medications (2.6 vs 2.0; P = .001) and concerns about becoming dependent on medication (3.6 vs 3.0; P = .007). BIPOC/H patients also reported higher scores on the harm subscale, including more concern that medications are addictive (4.1 vs 3.7; = .009) and are toxic (4.1 vs 3.6; P = .016). The additional concern about medications and fear of harm did not translate into statistically significant medication adherence differences in BIPOC/H patients via the MARS-4; however, BIPOC/H patients tended to report more intentional skipping of doses (Table 4).

Table 4.

Beliefs about medications and adherence.

| W/HN (n = 102) | BIPOC/H (n = 66) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about medications | |||

| Necessity | 11.3 ± 5.7 | 11.1 ± 4.9 | .749 |

| Currently my health depends on my medication | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | .753 |

| My life would be impossible without my medication | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | .732 |

| Without my medication I would be very ill | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | .420 |

| My health and future depend on my medication | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | .438 |

| My medication prevents my condition from getting worse | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | .838 |

| Harm | 19.5 ± 3.5 | 17.7 ± 4.0 | .002 |

| People who take medication should stop for a period of time once in a while | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | .355 |

| Most medications are addictive | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | .009 |

| Natural remedies are safer than medicines | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | .002 |

| Medicines do more harm than good | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | .003 |

| All medications are toxic | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | .016 |

| Concern | 17.1 ± 4.6 | 14.9 ± 3.8 | .001 |

| Having to take medications worries me | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | .001 |

| I sometimes worry about the long term effects of my medication | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | .001 |

| My medications are a mystery to me | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | .160 |

| My medication disrupts my life | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | .054 |

| I sometimes worry about being too dependent on my medication | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | .007 |

| Overuse | 10.4 ± 2.9 | 9.7 ± 2.4 | .127 |

| Doctors prescribe too many medications | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | .127 |

| Doctors put too much trust in medications | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | .340 |

| If doctors spent more time with patients they would prescribe few medications | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | .090 |

| Medication adherence (MARS-4) | 18 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 | .13 |

| Nonadherent a | 26 (26) | 25 (38) | .08 |

| Component score b | |||

| I alter the dose | 16 (16) | 13 (20) | .54 |

| I forget to take a dose | 17 (17) | 18 (28) | .12 |

| I decide to miss a dose | 9 (9) | 13 (20) | .06 |

| I decide to stop medications altogether | 15 (15) | 9 (14) | .85 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Abbreviations: BIPOC/H, Black/Indigenous/People of Color/Hispanic; MARS-4, Medication Adherence Rating Scale-4; W/NH, White/non-Hispanic.

aScore of ≤16 was defined as nonadherence.

bProportion answering “sometimes,” “often,” or “always.”

Discussion

We found that BIPOC/H patients with IBD face wide ranging and significant challenges related to care access, disease control, and quality of life, and also face less social/emotional support. The study validated well-documented differences in SDOH in BIPOC/H patients, particularly underinsurance and income disparities that can impact health and well-being. Being underinsured has been associated with worse IBD-related clinical outcomes in previous studies. Although not a specific focus of this investigation, other research has demonstrated that those insured by Medicaid who were members of historically disadvantaged races are less likely to receive surgical treatment for the most severe disease and have longer wait times for needed procedures, likely resulting in lower quality of life and higher mortality.28,29 BIPOC/H patients experienced significantly more impacts on their ability to work and go to school due to their high IBD symptom burden and its consequences, a finding that supports earlier studies that suggest that, controlling for other SDOH factors such as socioeconomic status and insurance status, Black and Hispanic people with IBD have significantly impaired productivity.30 Opportunities persist to improve access to care that can positively impact the potential for more optimal outcome.

BIPOC/H patients with IBD experienced significantly more difficulty accessing care from an IBD specialist when needed. As in earlier studies, Black patients were less likely to be receiving regular IBD care from a gastroenterologist and were more likely to have required ED evaluation and treatment.16 Utilization of the ED is a recognized indicator of disparities in care delivery, and this was observed in the BIPOC/H patients.31 Access to appropriate specialist care can significantly affect outcomes, with treatment delays risking progression to irreversible bowel damage.32 One quarter of all patients reported difficulties accessing IBD medications, a surprisingly high finding; however, interestingly, there were no differences in reported difficulty between White and non-White patients. Regardless, findings indicate that BIPOC/H people with IBD experience higher symptom burden, including pain and diarrhea, and substantially reduced quality of life.

Negative quality-of-life impacts may be compounded by the finding that BIPOC/H patients report barriers to the receipt of support to help deal with the significant emotional and functional impacts of IBD. Lack of social support, inadequate interaction and engagement, and social isolation especially in the COVID-19 pandemic have been associated exacerbation of functional gastrointestinal symptoms in IBD patients.33 Recognized challenges facing IBD patients include the unpredictable nature of living with IBD, emotional turmoil related to coping with IBD symptoms, and difficulty maintaining a normal life in light of symptoms.34 BIPOC/H patients in this study report inadequate resources available to connect with others and receive support for dealing with IBD. This finding is a particular relevance for providers striving to improve care to its IBD patients via creation and implementation of materials that clinicians can share with patients to assist connection with that needed support.

Another key finding of this study is the great concern for long-term medication use and the fear of medication-associated harms among BIPOC/H patients. Nguyen et al35 demonstrated that patients’ trust in physicians is a potentially modifiable predictor of adherence to IBD medical therapy. Although adherence appeared numerically lower in BIPOC/H than W/NH patients in our study, this difference was not statistically different, possibly due to insufficient statistical power. However, it is clear that BIPOC/H patients with IBD have significant greater concerns regarding becoming dependent on medications, fears about addictiveness and toxicity, and worry about the effects of long term use. During the survey development when the multiracial PERCs were engaged to consult on the content, participants expressed that when medication changes were made by their clinicians, it was typically in times of severe symptom exacerbation or crisis, and that little detailed shared communication between patients and clinicians occurred regarding medication options and their pros and cons. The PERC members stated that they wished that there was a mechanism to be better informed about their medications to minimize fears and concerns. Upon completion of the results, the survey findings were shared back to the PERC participants that informed the survey development. The BIPOC/H participants agreed that the findings were relevant to their own experiences, and were not surprising. As one Black PERC patient shared, “I definitely agree with these key findings. It’s definitely heart-wrenching when you really think about it. I’ve dealt with it personally, especially when it comes to health-related quality of life. And I also have a brother who has a similar illness to mine, and we speak about it quite often because I have children and I’m concerned about their health as well.” In addition, several noted similar experiences issues including delays in diagnosis, poor outcomes, and lack of access to specialists. This input supports the need for developing and implementing resources for patients and clinicians to improve access to culturally competent care, including patient decision aid in support of shared decision making for diverse patients with IBD in a culturally competent manner to address this issue. Shared decision making is an approach in which clinicians and patients make decisions together using the best available evidence, presented in a manner that allows patients to understand risks and benefits of treatments in plain language, and provides patients an opportunity to explore what is important to their healthcare goals within the context of the medication decision while communicating this to their clinician.36 With implementation of tools to support shared decision making, it will be useful to examine if IBD patients have improved medication self-efficacy and less medication decisional conflict.

The limitations to this study include a single-center survey of a small number of patients that may not be representative of the diverse IBD community. Moreover, the survey was only sent out once via email communication through MyChart, and to those who could respond to online surveys in English, with no attempt to follow-up with a paper-based survey. This is a relatively small response rate (14%), limiting response data in patients with the greatest sociodemographic challenges, particularly those with access challenges to technology, those with lower literacy, or those not fluent in English. Study results are generalizable only to patients with characteristics similar to those included in this study during the study period, which overlapped at least partially with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data may not be generalizable to other populations, or similar populations treated in different time frames. Patients may have experienced additional challenges with care access and social isolation during the pandemic. Another limitation was the reliance on self-reported medication adherence without an objective measurement of refills, as an example. It is possible that trends toward nonadherence would be different with a more robust measure. Last, differentiating UC from CD relied on ICD-10 medical record coding, which may be subject to inaccuracies when discriminating between the two. Although both can coexist, we had a larger than expected subgroup with both diagnoses likely due to these coding issues.

Conclusions

This is a comprehensive study of sociodemographics and barriers to care in a racially and ethnically diverse patient population with IBD. The results confirm that IBD patients from historically marginalized communities have worse symptom control, poorer HRQOL, more barriers to accessing specialty care and social/emotional support for their IBD, more negative impacts of IBD on employment and finances, and more concerns about taking long-term medications for their IBD. Future work on developing resources and solutions for clinicians and patients to improve outcomes is warranted.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Inflammatory Bowel Diseases online.

Contributor Information

Shamita Shah, Department of Gastroenterology, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Alicia C Shillington, EPI-Q Inc, Oak Brook, Illinois, USA.

Edmond Kato Kabagambe, Department of Gastroenterology, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA; Research Administration, Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health, Lancaster, PA, USA.

Kathleen L Deering, EPI-Q Inc, Oak Brook, Illinois, USA.

Sheena Babin, Department of Gastroenterology, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Joseph Capelouto, Department of Gastroenterology, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Cedric Pulliam, Prevention Access Campaign, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Aarti Patel, Population Health, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Titusville, NJ, USA.

Brandon LaChappelle, EPI-Q Inc, Oak Brook, Illinois, USA.

Julia Liu, Department of Gastroenterology, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Conflicts of Interest

A.P. is a current employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. A.C.S., K.L.D., and B.L. are employees of EPI-Q Inc, which received payment from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, associated with the development and execution of this study. At the time of the study, S.S., E.K.K., J.A.C., and S.B. were employees of Ochsner Health, which received payment from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, associated with the participation as a site for this study. J.L. has served as a consultant for Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

References

- 1. Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD.. Landmark article Oct 15, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathological and clinical entity. By Burril B. Crohn, Leon Ginzburg, and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251(1):73-79. doi: 10.1001/jama.251.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2-6; discussion 16. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abraham C, Cho JH.. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2066-2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Odes HS, Fraser D, Hollander L.. Epidemiological data of Crohn’s disease in Israel: etiological implications. Public Health Rev. 1989;17(4):321-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright JP, Marks IN, Jameson C, Garisch JA, Burns DG, Kottler RE.. Inflammatory bowel disease in Cape Town, 1975-1980. Part II. Crohn’s disease. S Afr Med J. 1983;63(7):226-229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loftus EV, Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR.. Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1161-1168; erratum in: Gastroenterology 1999;116(6):1507. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afzali A, Cross RK.. Racial and ethnic minorities with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a systematic review of disease characteristics and differences. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(8):2023-2040. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brant SR, Okou DT, Simpson CL, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies African-specific susceptibility loci in African Americans with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):206-217.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguyen GC, Torres EA, Regueiro M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics among African Americans, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites: characterization of a large North American cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(5):1012-1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson JF, 3rd, Dhere T, Repaka A, Shaukat A, Sitaraman S.. Crohn’s disease in an African-American population. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(5):389-392. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31816a5c06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alli-Akintade L, Pruthvi P, Hadi N, Sachar D.. Race and fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e21-e23. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castaneda G, Liu B, Torres S, Bhuket T, Wong RJ.. Race/Ethnicity-specific disparities in the severity of disease at presentation in adults with ulcerative colitis: a cross-sectional study. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2876-2881. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4733-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sedano R, Hogan M, Mcdonald C, Aswani-Omprakash T, Ma C, Jairath V.. Underrepresentation of minorities and underreporting of race and ethnicity in Crohn’s disease clinical trials. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):338-340.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi HY, Levy AN, Trivedi HD, Chan FKL, Ng SC, Ananthakrishnan AN.. Ethnicity influences phenotype and outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(2):190-197.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1398-1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flasar MH, Johnson T, Roghmann MC, Cross RK.. Disparities in the use of immunomodulators and biologics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):13-19. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, Wang MH, Datta LW, Brant SR.. Racial disparities in utilization of specialist care and medications in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(10):2202-2208. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alchirazi KA, Mohammed A, Eltelbany A, et al. Racial disparities in utilization of medications in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S):e758-e759. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000860820.62357.d2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Straus WL, Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray SC, Sessions JT.. Crohn’s disease: does race matter? The Mid-Atlantic Crohn’s disease study group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(2):479-483. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.t01-1-01531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walker C, Allamneni C, Orr J, et al. Socioeconomic status and race are both independently associated with increased hospitalization rate among Crohn’s Disease patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1-6. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22429-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS). Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heckman TG, Somlai AM, Peters J, et al. Barriers to care among persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban and rural areas. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):365-375. doi: 10.1080/713612410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK.. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s relapse prevention trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(8):1571-1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horne R, Weinman J.. Self-regulation and self management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):17-32. doi: 10.1080/08870440290001502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horne R, Parham R, Driscoll R, Robinson A. Patients’ attitudes to medicines and adherence to maintenance treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(6):837-844. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M.. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14(1):1-24. doi: 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B.. The single item literacy screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen GC, Bayless TM, Powe NR, Laveist TA, Brant SR.. Race and health insurance are predictors of hospitalized Crohn’s disease patients undergoing bowel resection. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(11):1408-1416. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen GC, Laveist TA, Gearhart S, Bayless TM, Brant SR.. Racial and geographic variations in colectomy rates among hospitalized ulcerative colitis patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(12):1507-1513; erratum in: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(6):765. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Agrawal M, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Kayal M, et al. Disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients is associated with race, ethnicity and socio-economic factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(5):564-571. doi: 10.1111/apt.15107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li D, Collins B, Velayos FS, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization and outcomes among ulcerative colitis patients in an integrated health-care organization. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(2):287-294. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2908-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berg DR, Colombel JF, Ungaro R.. The role of early biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019. ;25(12):1896-1905. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Byron C, Cornally N, Burton A, Savage E.. Challenges of living with and managing inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-synthesis of patients’ experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(3-4):305-319. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nass BYS, Dibbets P, Markus CR.. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inflammatory bowel disease: the role of emotional stress and social isolation. Stress Health. 2022;38(2):222-233. doi: 10.1002/smi.3080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, Datta LW, Bayless TM, Brant SR.. Patient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1233-1239. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R.. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.