Abstract

This scoping review explores the breadth and depth to which Domestic Violence Intervention Programs (DVIPs) in the United States and globally: (a) incorporate components that address the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and social injustice, racism, economic inequality, and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs); (b) use restorative (RJ)/transformative justice (TJ) practices, individualized case management, partnerships with social justice actors, and strengths-based parenting training in current programming; and (c) measure effectiveness. In 2021, we searched 12 academic databases using a combination of search terms and Medical Subject Headings. In all, 27 articles that discussed at least one key concept relative to DVIP curricula were included in the final review. Findings suggest that very few DVIPs address ACEs and/or the relationship between structural violence, social inequality, and IPV perpetration. Even fewer programs use restorative practices including RJ or TJ. Furthermore, DVIPs use inconsistent methods and measures to evaluate effectiveness. To respond to IPV perpetration more effectively and create lasting change, DVIPs must adopt evidence-informed approaches that prioritize social and structural determinants of violence, trauma-informed care, and restoration.

Keywords: domestic violence, cultural contexts, batterers, violent offenders, intervention/treatment

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a prevalent public health problem that negatively affects communities, survivors, offenders, 1 and families. Risk factors for IPV perpetration span various social and structural circumstances, and individual traits. Social and structural risk factors for IPV perpetration include income inequality, community disadvantage, systemic marginalization, traditional gender norms, racism, poverty, and adverse experiences of trauma and stress, particularly during childhood (Bell, 2009; Schneider et al., 2016; Solar & Irwin, 2010; Voith, 2019; Voith, Logan-Greene et al., 2020; Whitfield et al., 2003). A growing body of scholarship also recognizes the relationship between criminogenic risk factors and IPV perpetration. Such risk factors include but are not limited to antisocial personality patterns, social supports for IPV, substance abuse, dysfunctional family relationships, and low self-control/impulsivity (Bonta & Andrews, 2016; Hilton & Radatz, 2018, 2021; Stewart & Power, 2014).

Legal system actors rely heavily upon Domestic Violence Intervention Programs (DVIPs), also referred to as Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs) or offender treatment, as the standard intervention for IPV offenders. DVIPs commonly use psychoeducation-based models rooted in feminist theory that focus on dismantling offender beliefs about “power and control.” Founded in 1977 and 1983, respectively, Emerge and Duluth are two popular feminist-oriented models that hinge on the premise that IPV is a result of patriarchal social and cultural norms and that changing individual-level beliefs and attitudes will lead to behavior change (Hamel, 2020; Pence, 1983; Rosenbaum & Leisring, 2001). These programs are often paired with cognitive-behavioral programming, which focuses primarily on improving skills such as communication and emotional control (Rosenbaum & Leisring, 2001). There is limited evidence of DVIP efficacy in this regard, and scholarship has called these commonly used methods into question (Aaron & Beaulaurier, 2017; Karakurt et al., 2019; Travers et al., 2021; Weissman, 2020).

Programming focused on attitudes and behaviors related to “power and control” also neglects to consider how both criminogenic risk factors, and major structural and social factors such as systemic injustice and racism, economic inequality, and neighborhood disadvantage impact offenders and contribute to violence perpetration (Armstead et al., 2021; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002; Voith, 2019). Moreover, standard DVIP curricula often fail to address offenders’ mental health and trauma histories; decades of research suggest IPV offenders have experienced more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and related trauma, compared to the general population (Bell, 2009; Voith, Logan-Greene et al., 2020; Whitfield et al., 2003). Finally, the narrow view taken by popular DVIP models fails to consider IPV survivors. Advocates who work with survivors of domestic violence report that survivors want involvement with and a meaningful process by which the person who harmed them may be held accountable (Bolitho, 2015).

In addition to deficits in comprehensive programming, researchers and practitioners have also recognized that current measures of DVIP efficacy, which is typically assessed by re-arrest rates, offender self-report, or partner self-report, are both inadequate and fraught with complexity, and that more comprehensive indicators are required to accurately gage DVIP implementation and outcomes (Babcock et al., 2016). Currently, however, there is no consensus as to what constitutes “success” for DVIPs, nor how to operationalize “desistance” from violent behavior or recidivism. Similarly, validated measures that assess attainment of program content, mental health and substance use indicators, and indicators of program implementation are lacking in evaluations of DVIPs. Findings from a multi-site study of DVIPs that examined state standards found that “only 5% of states rely on state-of-the-art evidence-based models of partner violence [treatments],” thus indicating the need for measurements of program efficacy (Babcock et al., 2016).

Given the mixed evidence regarding the appropriateness and effectiveness of current DVIP models, scholars and providers are exploring alternative and complementary treatment models that utilize social, restorative (RJ), and transformative (TJ) justice frameworks. RJ, a survivor-centered approach, promotes the agency and perspective of those harmed and leverages community relationships and resources to provide an opportunity for healing (Gang et al., 2021; Kim, 2021). There is evidence for the effectiveness of RJ interventions in other areas, including violent crimes, property crimes, and drunk driving (Sherman & Strang, 2007). TJ encourages broad community participation beyond the survivor/offender dyad, prioritizing comprehensive and collaborative strategies to improve individual and structural circumstances that may contribute to violent behavior (Weissman, 2020). Efforts toward incorporating RJ and TJ into DVIPs are in the early stages, but two small randomized controlled trials in Arizona and Utah have shown encouraging results with respect to effectiveness (Mills et al., 2013, 2019). In addition, some DVIPs have started to experiment with wrap-around, or holistic, community-involved, social justice-oriented services. For example, the House of Ruth in Maryland provides services that assist with individualized needs such as employment, substance abuse counseling, mental health treatment, and parenting programs (Center for Justice Innovation, n.d.). Other programs draw on fatherhood as a motivator and focus on strength-based parenting and skill building to help break intergenerational cycles of violence and assist fathers in becoming supportive parents and partners (Futures Without Violence, 2023; Strong Fathers Program, n.d.). Finally, frameworks like the Risk-Need-Response (RNR) and Principles of Effective Interventions (PEI) assess offenders’ criminogenic risks and needs, then match treatment strategies and programmatic intensity to these unique needs in tailored treatment programs (Bonta & Andrews, 2007; Radatz & Wright, 2016). Research suggests that programs that adhere to individually tailored treatment plans are effective in reducing recidivism among domestic violence offenders (Radatz & Wright, 2016; Radatz et al., 2021).

The consensus among scholars and practitioners underscores the necessity to modernize offender treatment, aligning it with current knowledge, given the recognized ineffectiveness of traditional feminist models. Evidence-based frameworks such as the RNR and PEI show promise in addressing offenders’ criminogenic needs, and at least one systematic review has been conducted to assess the uptake and effectiveness of these frameworks (Radatz & Wright, 2016). However, the uptake and effectiveness of RJ, TJ, social justice principles, and strategies that acknowledge the relationship between social and structural determinants of violence and IPV perpetration beg further investigation. In response to this need, we conducted a scoping review to explore how these approaches are currently incorporated into DVIPs, and whether and how programs using these frameworks are evaluating effectiveness. The following research questions guide this review: (a) To what extent do existing DVIPs incorporate components that address the relationship between IPV and social/structural issues including social injustice, racism, economic inequality, and ACEs? (b) To what extent do existing DVIPs use RJ/TJ practices, individualized case management, strengths-based parenting training, and partnerships with social justice actors in current programming? (c) How do these programs measure effectiveness?

Methods

Definitions and Selection Criteria

This review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations for systematic and scoping reviews. We focused on several key concepts including program effectiveness, family group counseling, restorative justice, transformative justice, social justice, case management, program partners, economic inequality, racism, ACEs, and strength-based parenting. Our team agreed upon the definitions of these key terms based on prior knowledge and expertise; we included any related content that embodied the key concept (see Table 1 for definitions). To be included, studies met the following criteria: (a) pertained to DVIPs, (b) discussed at least one key concept of interest, and (c) were written or translated into English. Studies were excluded if they: (a) were conducted before 2000, (b) did not focus on domestic violence interventions (e.g., focused on anger management, couples counseling), (c) program participants were under 18 years old, (d) key concepts of interest were not discussed, or (e) key concepts of interest were not a part of programming. No restrictions were placed on participants’ gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, nationality, or any other demographic characteristics. Furthermore, no restrictions were placed on the country in which the study took place or where the DVIP was created or operated, whether participants were court mandated or self-referred into treatment, or type of publication (e.g., peer-reviewed manuscript, dissertation, critical essay).

Table 1.

Description of Key Concepts of Interest.

| Key Term | Description of Concept |

|---|---|

| Program effectiveness | • Definition or measures of effectiveness or program success. |

| Family group counseling | • Helping families and/or couples cope with domestic violence, structural inequities, and social injustice related to domestic violence. |

| Restorative justice | • Engaging the person(s) causing harm to acknowledge the harm that they have caused, prioritize ending violence, promoting safety and empowerment, and changing social norms. • Prioritizing survivor empowerment, healing, involvement, and perspectives into offender treatment. |

| Transformative justice | • Efforts to gain community support to address conditions that create violence and disavow carceral, punitive approaches to transgressive behavior. |

| Social justice | • Endeavors to respect the diversity of cultural values and the impact of systemic oppression on interpersonal violence. |

| Case management | • Holistic, “wrap-around,” or individualized services provided to an offender that goes beyond the bounds of the program curriculum to address additional needs. This may include referral practices, follow-up, cultural tailoring, etc. |

| Program partners | • Collaborations and partnerships with other community-based agencies that are relevant to offender treatment and secondary IPV prevention. |

| Economic inequality | • Fees, financial burdens, employment assistance, economic resources, or anything related to DVIP participants’ economic or financial stability. |

| Racism | • Discrimination or oppression based on race, ethnicity, immigration status, primary language spoken, or anything related to racial inequality. |

| Adverse childhood experiences | • Offenders’ history of childhood trauma, abuse, or neglect. |

| Strengths-based parenting | • Promoting positive, strengths-based parenting from the father or abusive partner. |

Note. DVIPs = Domestic Violence Intervention Programs; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Search Strategy and Data Extraction

In early 2021, we searched PubMed, Academic Search Premier, PyscINFO, Social Work Abstracts, JSTOR, Sociological Abstracts, PAIS Index, Political Science Database, GenderWatch, Social Services Abstracts, Criminal Justice Database, and Social Science Research Network, using a combination of search terms and Medical Subject Headings. For all database searches, we used the Boolean search string: ((“Abuser” OR “Batterer”) AND (“Treatment” OR “Intervention”) AND (“Program”)) OR (“Domestic Violence Intervention Program” OR “DVIP”) OR (“Fatherhood” OR “Strong Fathers” AND (“Domestic Violence”)). We downloaded returned articles from each database, removed duplicates, and uploaded articles into the systematic review automation manager, Covidence. Five reviewers (JC, SN, SH, SM, and JW) reviewed all titles and abstracts; each article was evaluated by two reviewers, and discrepancies were recorded by Covidence. Reviewers then met to resolve discrepancies and reach an agreement regarding which articles met the criteria for full review. Three reviewers (JC, SN, and BN) assessed the full text of each potentially relevant article and these reviewers met again to resolve discrepancies.

To achieve harmony in data extraction, reviewers collaboratively designed an extraction tool and agreed upon which data to extract. To assess patterns in study results, we extracted article title, author names, year of publication, study design and site, years of data collection, sample size, relevant sample demographics (e.g., gender, age, educational attainment), description of how the key concept was implemented into programming, the measure or indicator used to assess program effectiveness, and key findings related to key concepts of interest (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Articles Included in Scoping Review (N = 27).

| Authors, Title, and Year of Publication | Years of Data Collection | Study Design and Site | Sample Demographics | Key Concept | Implementation of Concept | Measure/Indicator Assessing Program Effectiveness | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Babcock et al. (2016). Domestic violence perpetrator programs: A proposal for evidence-based standards in the United States | 1990–2016 | Literature review on the characteristics and efficacy of DVIPs in the United States and Canada | N/A | ACEs Racism |

- Recommend program components should help clients: (a) identify and overcome abusive and dysfunctional patterns of behavior from childhood; (b) address toxic effects of shame; (c) understand trauma’s impact on the brain and human development; and (d) learn about the effects of domestic violence on children and teach positive parenting skills. - Integrate curricula with considerations for social conditions, stressors, religion, and spirituality relevant to ethnic minority communities. |

- Likelihood of repeated acts of violence - Reductions in frequency and severity of violence - Willingness to change and take responsibility for behavior - Attachment style - Expressive and instrumental motives of violence perpetration - Program completion - Fidelity to state standards |

- The limitations of DVIP success are in large part due to the limitations of current state standards regulating these programs. - State standards are not necessarily grounded in empirical research evidence or best practices. |

| 2. Crockett et al. (2015). Breaking the mold: Evaluating a non-punitive domestic violence intervention program | Not given | Single sample pre–post-test design Austin, TX, USA |

N = 149 DVIP participants (n = 35 female, n = 110 male) - Average age = 35.1 years - 44.8% White; 23.9% Black/African American; 21.6% Hispanic; 1.5% Asian; and 8.2% “Other” - 14.5% no high school; 28.1% high school diploma; 41.3% some college; 36.4% college degree. |

ACEs | - Resolution Counseling Intervention Programs (RCIPs): psychoeducational programs that teach healthy relationship skills and include elements of traditional DVIPs while focusing on addressing violence in the origin family. RCIPs encourage customized sessions to address individual client vulnerabilities, providing more diverse treatment options than a “one-size-fits-all” model. |

- Perceived stress - Desire for change - Accountability - Safety planning (potential for diffusing violent situations) - Anger management - Controlling behaviors - Violent behavior - Social desirability |

Participation in RCIP fostered attitudes known to be associated with nonviolence, including perceptions of accountability, anger management, indications of safety planning and reported desire for change. In addition, self-reported levels of psychological and physical violence decreased from pre- to post-treatment. |

| 3. Cuevas and Bui (2016). Social factors affecting the completion of a batterer intervention program | 2006–2010 | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of clinical files of male batterers who completed at least an intake assessment in a state-approved DVIP Los Angeles, CA, USA | N = 180 male offenders. All were over 18 years old; the majority were between 26 and 35 years old. Most were Latino/Hispanic, had an annual income <$19,999, had a Graduate Equivalency Degree (GED), and lived alone. | ACEs | - Individualized treatment plan that addresses experiences of childhood abuse, witnessing sibling and parental violence, having a distant relationship with one’s father, and experiencing parental divorce. Emphasis should be placed on aspects of intergenerational patterns that model and transmit violence. | - Program completion - Suggests measuring participant experiences of childhood abuse, and aspects of participants’ relationship with their father |

Offenders who had a close relationship with their father and who did not experience child abuse, sibling abuse, parental violence, or parental divorce, had a 0.72 probability of completing the program. Perpetrators who had a distant relationship with their father and who experienced child abuse, sibling abuse, parental violence, and parental divorce, had a 0.23 probability of completing the program. |

| 4. Domoney and Trevillion (2020). Breaking the cycle of intergenerational abuse: A qualitative interview study of men participating in a perinatal program to reduce violence | 2015–2019 | Cross-sectional qualitative study using semi-structured interviews London, England, United Kingdom | N = 10 men. All (100%) were White British males with children. Mean age = 29 years. 60% cohabitated with their child’s mother, 40% were in a relationship with the child’s mother but lived separately. | Strengths-based parenting | Parenting intervention (“For Baby’s Sake”) is aimed at families in the perinatal period where there is identified IPV. The program uses videos, interactive guidance, and practical skill building to target IPV, mental health, parenting, and parents’ histories of trauma to break intergenerational cycles of trauma and abuse and improve parenting techniques. | Not described | - New fatherhood is a motivator for change in partner-abusive men. Intervening in the perinatal period and including a focus on parenting may improve engagement in programs to reduce violence and help reduce the impacts of intergenerational trauma. |

| 5. Garcia (2010). Contraindications of discourse: Evaluating the successes and problems of a batterer intervention program | N/A | Critical essay by former DVIP participant/current DVIP facilitator Georgia, USA | N/A | Transformative justice Social justice | - The Men Stopping Violence (MSV) curriculum includes a discussion on the intersection between race, gender, class, and violence; information on the formation of social structures within the man’s community is intended to push and challenge patriarchal views of violence outside of the DVIP class. The DVIP at MSV is part of a larger community accountability model that sees violence against women as a systemic problem and maintains that the solution must be community-based. |

Not described | The belief in DVIPs as the sole solution to men’s violence remains widespread. - DVIPs should build relationships with organizations that share a common goal outside of the criminal justice system. Accountability from external groups can empower DVIP facilitators to incorporate victims’ experiences, without placing the burden on victims to train men as allies. |

| 6. Gondolf (2008). Program completion in specialized batterer counseling for African American Men | 2001–2003 | Randomized control trial with assignment to conventional counseling in a mixed racial group, conventional counseling in an all-African American group, or culturally focused counseling in an all-African American group Pittsburg, PA, USA | N = 501 African American men. 56% were older than 30 years; 60% were unemployed and 20% were considered to have “high income” (cutoff not specified). | Racism Social justice |

Culturally focused counseling groups for African American men should include: 1. A culturally rooted African American counselor with ties to predominantly African American neighborhoods. 2. Acknowledgment and elaboration of cultural issues (e.g., past and recent experiences of violence, reactions to discrimination and prejudice, being oppressed and being the oppressor, finding peace when you feel powerless, and more). |

- Completion rates - Curriculum fidelity |

Completion rates were the same across groups (i.e., the novel program did not improve completion rates), but there was an interaction effect for racial identification and group type such that, men with high racial identities were 33% more likely to complete specialized counseling groups than standard counseling groups. |

| 7. Gondolf (2011). The weak evidence for batterer program alternatives | N/A | Literature review of alternative approaches to DVIPs | N/A | Racism | - Curricula should address topics such as black male identity, racial discrimination, the criminal justice system, and neighborhood resources, as well as the spiritual strength and heritage of the African American community. | - Re-arrest - Re-assault - Feelings of comfort in the group (comfort with talking to other men in the group, developing friendships outside of the group) - Program completion |

Findings are mixed. Some studies find no differences in effect between Black and White participants, others find that participants feel more comfortable in racially/culturally specific groups. |

| 8. Kreuziger (2020). Fifty-two-week batterer intervention programs (BIPs): An effective alternative to incarceration for male perpetrators | Not given | Exploratory qualitative study San Bernardino County, CA, USA |

N = 42 (n = 22 BIP participants, n = 22 BIP facilitators) Participants: 100% male; age range 20–50+; race (not given); 77% were employed with wages, 14% were self-employed, 5% were looking for work, and 5% unable to work Facilitators: 52% male, 48% female; age range 20–50+; race/ethnicity not given, 81% employed with wages, and 19% self-employed |

Strengths-based parenting Economic inequality ACEs Case management |

- Psychoeducational behavioral modification groups focused on skill building for accountability, parenting, communication, identifying red flags and consequences of actions before violence occurs, and stress management. - Post-graduation counseling; group parenting courses, mental health counseling, accountability - Professional and economic development both during and after treatment; job acquisition assistance, job training, and sliding fee scales. - Open-door policy for offenders to return and use services. |

- Facilitator and offender opinions, gathered through in-depth interviews, about what program components and supporting factors make a DVIP successful. - Mean scores on subjective value of different components. |

Both facilitators and participants agree that trauma-informed, positive thinking, and behavior change components are needed. Facilitators believe that an effective offender–facilitator relationship is the most important supporting factor and offenders believe that financial options are the most important supporting factor. |

| 9. LaViolette (2001). Batterers’ treatment: Observations from the trenches | N/A | Description of the Alternatives to Violence program Los Angeles, CA, USA | N/A | Family group counseling Program partners | - Family is included in intake and invited to discuss concerns with facilitators. The program hosts annual family events. - Program builds and maintains relationships with city prosecutors, judges, police officers, clergy, children’s advocates, battered women’s advocates, probation officers, representatives from children’s services, etc., and approaches offender treatment from a “holistic” perspective. |

- Cessation of physical aggression - Recognition of non-physical abuse - Changes in attitudes or beliefs - Acceptance of responsibility - Shorter, less intense outbursts with longer periods between episodes - Development of empathy for the victims of their abuse - Regular group attendance - Cooperation in the group and compliance with group rules - Redefinition of power - Ability to take a time-out - Recognition of controlling behaviors |

Offenders are not a homogeneous population and different participants require different treatment approaches. DVIPs are part of a larger social movement to end violence; such programs are only one part of a much larger network of interventions. |

| 10. Macleod et al. (2008). Batterer intervention systems in California—An evaluation: Policy issues and research implications | 2006 | Quasi-experimental study California, USA |

N = 1,457 male offenders who were convicted of a criminal IPV offense against a female partner. Average age = 33.68 years 17% African American; 51% Hispanic; 22% White; 10% “Other” Average annual income <$18,000 23% some college, 47% are employed full time; and 22% are unemployed. |

Case management | Comprehensive intake assessment administered by the trained facilitator that includes the offender’s age, medical history, employment and service records, educational background, community and family ties, prior incidents of violence, police report, treatment history, demonstrable motivation, history or current substance use. This tailored approach recognizes the diverse needs, issues, and strengths of offenders and their partners, as opposed to a one-size-fits-all approach that shows limited effectiveness. | - Re-arrest - Program completion - Violation of probation - Changes in attitudes and beliefs (BIP Process Survey) |

Because of the salience of individual characteristics in predicting program completion and re-offense, enhanced risk and needs assessment at intake may improve offender treatment. Drug/alcohol treatment may be essential to help offenders end their abuse. The current DVIP fee structure may hinder differentiated case management. |

| 11. Magruder (2017). Working the front lines of intimate partner violence (IPV): Responders’ perceptions of interrole collaboration | 2015–2016 | Exploratory qualitative study Florida, USA. |

N = 15 providers (DVIP and domestic violence victim service providers, and prosecutors). Data collected on 14/15 respondents: 71.4% Female; 92.9% White; average age = 37.9 years; average of 11.43 years of experience, range 1–30 years |

Program partners | Engage in inter-agency collaboration through a shared victim-centered approach; take on the perspectives of respondents in other roles; acknowledge the unique skill set of each partner; engage in respectful and frequent communication; share details about cases and interactions with victims and offenders; express gratitude and praise for other partners; provide networking opportunities; remain open to new ways of doing things; support partners through respectful education. | Not described | - Inter-agency collaboration and cross-training is essential for successful offender treatment. - There are several challenges to successful collaboration. |

| 12. McGill (2007). Emotional transformation: Investigating the short-term change in emotional intelligence of men who participated in a feminist-based cognitive behavioral batterer intervention program | 2007 | Exploratory qualitative study Midwestern region, USA |

N = 12 male batterers enrolled in a DVIP for the first time. Average age = 38.17 years old 100% African American 17% some high school; 17% high school graduate; 25% some college; 42% college graduate 8% unemployed; 17% part time; and 75% full time |

Case management | Mandatory “after care” (i.e., follow-up after program completion) that resembles Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) where participants have sponsors who were previously considered batterers but who have gone a long time without using any violence. Sponsors are to be trained in mentorship and facilitate connections with the community. | - -Changes in empathy (Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale) - Changes in emotional intelligence (General Emotional Intelligence Scale) - -Stages of change (Safe at Home Readiness for Change Survey) |

“A 24-week program is not enough time to challenge a lifetime’s worth of internalizing deficient belief systems, attitudes, and behavioral responses. While the intent is not to make a direct comparison with AA, and NA Support Groups in which some members participate voluntarily over the lifetime of their challenge, a much longer commitment to change from violent, abusive behavior like the aforementioned practices is highly indicated.” |

| 13. Mills et al. (2006). Enhancing safety and rehabilitation in intimate violence treatments: New perspectives | N/A | Viewpoint | N/A | Restorative justice | Family Group Conferencing (FGC) gathers family and supportive friends of the offender and the victim together with a facilitator, and child welfare and criminal justice professionals to hold the offender accountable for the harm done, ensure victim safety, facilitate open dialog about the violence, and develop a plan to rectify the problem. | Not described | Because this was not a research study, there were no findings, but the authors provide support for restorative justice practices and conclude that “FGC may actually provide greater victim empowerment and satisfaction than the criminal justice process alone.” |

| 14. Mills et al. (2013). The next generation of court-mandated domestic violence treatment: A comparison study of batterer intervention and restorative justice programs. | 2005–2007 | Randomized control study of participants assigned to either a standard DVIP or Circles of Peace Nogales, Arizona, USA. |

N = 152 Th average age at the time of domestic violence arrest: 33.5 years - 81% male; 83% Hispanic, 74.3% employed 30.3% had no high school education |

Restorative justice | - Circle of Peace (CP): designed to “restore” following a crime, moving beyond changing attitudes, beliefs, and getting the offender engaged in defining his or her future and using a social compact that guides weekly sessions. CPs include discussions about family history of abuse, triggers of violence, how socioeconomic status, cultural norms, racial oppression, and religious beliefs affect the dynamic of abuse, and incorporate family strengths and traditions. - Must include trained facilitators and offender support people. Victim participation is optional. Must be held in a private space (not a group). |

- Recidivism is measured as the number of domestic violence and non-domestic violence re-arrests. - Domestic violence arrest data referred to any new arrest for a domestic assault post-random assignment into treatment. Non-domestic violence arrest data was measured in terms of any new arrests not including domestic violence crimes during the post-randomization period. |

CP participants experienced less recidivism than DVIP participants during all follow-up comparisons. However, statistically significant differences were detected only for the 6-month (p < .1) and the 12-month (p < .05) follow-up comparisons for non-domestic violence re-arrests, and no statistically significant differences were detected for the domestic violence re-arrests. |

| 15. Montoya-Miller (2015). Development and evaluation of a supplemental curriculum for working with female domestic violence offenders: A narrative approach | Not provided | Mixed methods design California, USA | N = 5 facilitators of female-only DVIPs | ACEs | Narrative therapy curriculum where one module is dedicated to attachment style and history of caregiver attachment, and trauma in childhood. The attachment style is explored in group discussions and class activities (e.g., handouts). | DVIP facilitator opinions regarding the feasibility and acceptability of the narrative therapy curriculum. | Participants perceived that the narrative therapy ACES-focused supplemental curriculum was useful, applicable to female clients, and mostly addressed the needs of the female batterer but suggested that the amount of time allotted to cover each module should be increased. |

| 16. Morrison et al. (2019). Human services utilization among male IPV perpetrators: Relationship to timing and completion of batterer intervention programs | 2010–2015 | Cross-sectional exploratory study Pennsylvania, USA |

N = 330 men Average age = 35.6 years 50% White, 41% Black/African American; 7% Multiracial, 3% other |

Case management Program partners |

DVIPs had partnerships with human services agencies that address mental health, substance use, housing and homelessness (e.g., county housing authorities), health/medical assistance (e.g., Medicaid), general welfare (e.g., food stamps, TANF, SSI), legal involvement (probation and parole, juvenile justice), child welfare. | - Intake assessment that asks participants to indicate current or historical involvement with a list of agencies (measuring involvement as a binary variable and timing of involvement). - Recidivism |

“Improving BIP efficacy may be related to the ability to ensure that perpetrators’ co-occurring psychosocial and health needs are identified and met. Arguably, one agency cannot provide all services to all perpetrators, and thus, our findings support the need to continue working toward a coordinated community response to IPV perpetration.” |

| 17. Pitts et al. (2009). The need for a holistic approach to specialized domestic violence court programming: Evaluating offender rehabilitation needs and recidivism | 2004–2006 | Quasi-experimental design Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA |

N = 200; n = 100 offenders and 100 matched controls. Offenders: 100% male; 11% White, 6% Black, 14% American Indian, 63% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 5% Other; age range not reported, 36% unemployed |

Case management | - Case management should occur during and after DVIP participation. Direct services are provided by contracted agencies or referrals to other community resources for offenders, victims, and families. DVIPs should take a “holistic approach” to addressing mental health, substance abuse, vocational, living skills, relationship improvement, power and control issues, educational, or other needs. |

- Recidivism - Program completion - Length of time enrolled in the DVIP - Victim participation |

There is a strong positive correlation between employment status and those who are successfully discharged, meaning employment status at discharge is important for treatment success. This suggests that case management that helps offenders maintain employment is associated with positive treatment outcomes. |

| 18. Portnoy (2016). Behavior change processes of partner violent men: An in-depth analysis of recidivist events following abuser intervention program completion | Not provided | Exploratory qualitative study Howard County, MD, USA |

N = 11 offenders who had completed DVIP treatment and who had re-offended at least once after completing treatment. Average age = 37.5 years - 36% African American, 45% White, 9% Hispanic, 9% Indian - 36% completed High School, 45% some college, 9% graduate school, 1% less than high school 36% unemployed, 55% full-time work, 9% part-time work |

Family group counseling | - Flexible, tailored treatment that gives participants the option of group, individual and/or couples therapy. - Skill acquisition and practice applying skills related to communication, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, anger management, cognitive restructuring, and substance use |

- Offender perceived reason for re-offending - Offender perceived influence of DVIP on behavior - Offender’s perception of the skills they gained (or did not gain) during treatment |

- Participants requested a flexible treatment approach (e.g., options for group, individual, or couples therapy, focused treatment for substance use, and/or a drop-in group following treatment completion. - Participants desired additional resources for co-occurring substance use and identified financial barriers to getting help, financial problems, parenting stress, and a history of trauma as variables that influence violent behavior. |

| 19. Saunders (2008). Group interventions for men who batter: A summary of program descriptions and research | N/A | Literature review on all male interventions for men who batter, program components, treatment effectiveness, and methods for enhancing treatment. Global locations (mostly USA, some programs from Europe reviewed) |

N/A | Racism Case management |

- Offer men a choice between same- or mixed-race programs or programs that “treat everyone the same” versus those that address historical and contemporary experiences of particular cultural groups and center-specific cultures in treatment. The goals of such programs are to: (a) address resentment toward the criminal justice system and society as a whole; (b) increase training and information; and (c) network and consult with minority communities on culturally sensitive responses and evaluating efforts. - 3–4 extra-long sessions per week in the first few months to support offenders’ needs most during the period when re-assault is most likely to occur. Then provide continued case management. |

Not described | “Domestic violence programs rely heavily on cognitive–behavioral and gender resocialization methods. Despite an accumulation of outcome studies, very few are rigorous. Firm conclusions cannot be made about intervention effectiveness. . .Increased attention to cultural competence is another promising development. However, the integration of abuser, survivor, and criminal justice interventions within each community may provide the key to the most effective interventions.” |

| 20. Scott et al. (2007). Guidelines for intervention with abusive fathers. | N/A | Description of the Caring Dads program The program began in London, Ontario, Canada; is now available in Canada and the USA. |

N/A | Strengths-based parenting | - Group therapy focused on child safety and well-being that focuses on parenting, fathering, battering, and child protection practices - Aims to boost men’s motivation, encourage child-centered fathering, address co-parenting respectfully, consider children’s trauma, and collaborate with other service providers to ensure children’s welfare. |

Not described | This was a program description, not an evaluation study so there are no key findings. However, additional information about effectiveness can be found on the organization’s website at caringdads.org. |

| 21. Simmons (2006). African-American male batterers’ perceptions of treatment program effectiveness | 2004–2005 | Exploratory qualitative study Washington, D.C., USA |

N = 8 African American men who completed a DVIP. Average age = 38.75 years 100% African American men 13% some high school; 13% high school graduate; 25% some college; 38% college graduate; 13% not given 50% unemployed; 50% full-time employment |

Racism | Culturally sensitive, strengths-based group treatment for African American men that integrates aspects of Black culture, identity, spirituality, and experiences of discrimination. Treatment should address the sociocultural environments in which offenders learn violence and corresponding attitudes and actions. Also, practitioners should incorporate key elements of Afrocentric theory’s emphasis on empowering individuals to change through a comprehensive analysis of the offenders’ strengths. | Not described | Participants noted the following areas as helpful in considering when working with African American male offenders: (a) environmental and social factors have a strong influence on behavior, (b) cultural background and sociocultural dissonance influence behavior, and (c) perceptions and levels of cultural awareness and identity impact behavior. |

| 22. Sullivan (2006). Evaluating parenting programs for men who batter: Current considerations and controversies | N/A | Commentary on the criteria that should be considered when judging the success of efforts in working on parenting with men who batter | N/A | Strengths-based parenting | - Key aspects of DVIP parenting programs: 12-step educational criteria, skilled facilitators, optional involvement of mothers and children when safe. - Ensure cultural relevance, especially for LGBTQ+, immigrant/refugee, disabled, and marginalized parents. - Include guidelines for how to safely involve survivors and children including how to communicate with survivors; obtain consent/assent for children’s participation; conduct interviews with survivors and children; confidentiality and safety. |

- Essential elements for evaluation include interviews with program participants; input from the children’s mother on the extent to which actual change has taken place; and input from children if appropriate. Proxy indicators for success include measures of anger management, self-esteem, and psychiatric disorder. |

Parenting programs should focus on educating batterers that (a) family abuse in any form is unacceptable, (b) their behavior is and will be tied to their access to their children, and (c) they are responsible for all behavioral choices they make. |

| 23. Todahl et al. (2012). Client narratives about experiences with a multi-couple treatment program for intimate partner violence | Not provided | Exploratory qualitative study that utilized narrative methods Oregon, USA |

N = 53; n = 48 DVIP participants, n = 5 DVIP staff facilitators. Demographics not provided. |

Family group counseling | - CARE (Couples Achieving Relationship Enhancement) program: couples meet in a multi-couple, open-group format. A rotating, 10-week, solution-focused curriculum that emphasizes self-awareness, self-soothing and emotion regulation, attachment theory, interpersonal processes, the process of “outgrowing power and control,” brain anatomy and physiology, and self-mastery. - Participation is voluntary and initiated by the survivor. |

- Qualitative narrative interviews designed to explore the subjective experiences of participants | - Participants generally found the program to be safe and useful. Most female participants indicated that their voluntary involvement, their ability to withdraw from services at any time, and the pre-CARE women’s group were all factors in reasonably ensuring their safety. |

| 24.Tollefson (2001). Factors associated with batterer treatment success and failure | 1994–1998 | Secondary analysis of DVIP agency case records Utah, USA |

N = 197 Gender: n = 165 (84%) males and n = 32 (16%) females. Race: 88.8% white 40.1% unemployed; 54.4% less than a high school education |

Family group counseling | - Option to engage in regular groups, individual counseling, and/or couples counseling. - Couples counseling is available when: the offender completes at least 15 group sessions without re-offense, the offender’s partner wishes to participate following a discussion of safety issues, and the therapist believes the offender has taken responsibility for their behavior. - Program staff work with child welfare staff on cases where IPV and child abuse intersect. Staff members attend child protection team meetings and participate in case consultations to offer information and insight concerning family members. |

- Dropout/completion rates - Recidivism |

This was a study about factors that predict program dropout/attrition. The author found that socioeconomic status and psychopathology were major predictors of program attrition but did not evaluate the effects of treatment modality (individual, group, or couples) on any outcomes. |

| 25.Voith, Logan-Greene, et al. (2020). A paradigm shift in batterer intervention programming: A need to address unresolved trauma | N/A | Literature review that draws upon theories of trauma and the etiologies of violence perpetration and proposes an alternative model of care for men with IPV histories | N/A | ACEs | - Actively use trauma-informed principles in practice and interventions in programming through consideration of individual trauma histories. - Address trauma symptoms on neurological and physiological levels through mindfulness practices such as meditation, yoga, and breathing exercises. - Identify and process unresolved trauma and formerly adaptive thought patterns related to violence perpetration. - Develop and practice coping skills to manage emotional and behavioral responses to triggers. |

Programs should use the Trauma Symptom Inventory and Extended ACEs screening tools to assess trauma and tailor trauma-informed treatments to individual offenders. | “There is ample research to suggest that trauma and toxic stress are central in the etiology of the perpetration of domestic violence; yet the deep emotional, physiological, and psychological toll that men carry with them may be difficult to address with solely psychoeducation or cognitive restructuring (aka the current dominant approaches). Therefore, program components that intervene in trauma may be necessary to achieve changes in violent behavior.” |

| 26.Voith, Russell et al. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, trauma symptoms, mindfulness, and intimate partner violence: Therapeutic implications for marginalized men | 2017–2018 | Cross-sectional study. Midwestern region, USA |

N = 67 Average age = 32.42 6% White; 76.1% Black; 10.4% Hispanic or Latino; 1.5% Native American or Alaska Native 6% other Education: 4.5% less than high school; 26.9% some high school; 49.2% high school diploma or equivalent; 17.9% some college |

ACEs Racism |

- Including mindfulness in DVIPs may help reduce psychological aggression. - Attention to trauma and stress associated with low-income socio-economic status and historical/intergenerational trauma related to racism |

- ACE questionnaire - PTSD checklist - Self-report Inventory for Disorders of Extreme Stress (SIDES-SR) - Revised mindfulness self-efficacy scale (MSES-R) measures mindfulness self-efficacy, emotional regulation, equanimity, social skills, distress tolerance, taking responsibility, and interpersonal effectiveness. |

- “Adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness-based therapies were effective in reducing IPV perpetration rates among men and women.” - “ACEs and proximal trauma symptoms are related to self-reported IPV perpetration and victimization among socioeconomically disadvantaged men of color. . . Mindfulness self-efficacy may be one protective factor that contributes to diminished IPV among marginalized men.” |

| 27.Zakheim (2011). Healing circles as an alternative to batterer intervention programs for addressing domestic violence among Orthodox Jews | 2009 | Exploratory qualitative study Passaic, NJ, USA |

N = 14 Male Orthodox Jewish offenders enrolled in a DVIP and their partners/families. Additional demographic information was not provided. |

Restorative justice | - Healing circles (HCs) are a restorative justice (RJ) process involving the abuser, victim, both families, and the community. Participation is voluntary and aims to aid victim healing, ensure protection, and support abuser rehabilitation. HCs stress family and community problem-solving, cultural sensitivity, and reducing isolation for both the victim and abuser. They allow victims to define restitution and involve the entire family and community, serving as a culturally sensitive community intervention before domestic violence arrests. | - Motivation for victims and abusers to participate (measured through qualitative interviews) - Changes in relationship dynamics that led couples to want to participate in HC Recidivism |

“Healing Circles may be more effective in addressing domestic violence because the treatment involved both partners in an environment that provided support and safety. Making use of emergent themes from the interview process, Healing Circles were shown not only to result in decreased domestic violence but also in concrete ideas of how the participating couples might improve their relationships.” |

Note. ACEs = adverse childhood experiences; DVIPs = Domestic Violence Intervention Programs; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Results

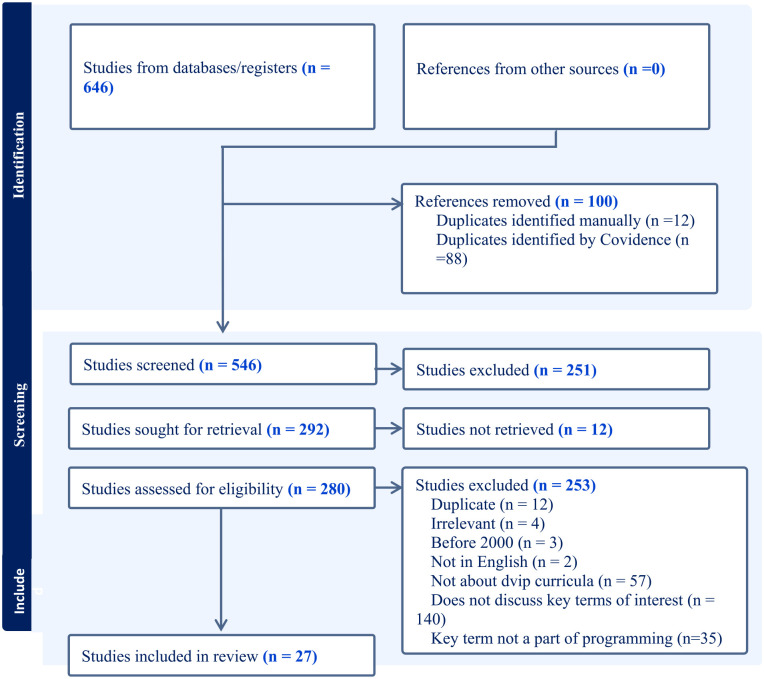

In our initial database search, we identified 546 unduplicated documents. After title and abstract screening, we retained 292 articles eligible for full-text review. Of these, we identified criteria for exclusion in 253 articles; 12 articles could not be retrieved. The final sample contained 27 articles (Figure 1 and Table 2). The study selection process, with detailed exclusion explanations, is presented in Figure 1. The social-ecological model often serves as a conceptual framework for understanding the complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, societal, and structural determinants of behavior. Behavioral interventions, accordingly, often target one or more levels within this model (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). To systematically delineate the initiatives undertaken by DVIPs to address the social and structural determinants of violence, we use this model to guide the presentation of the findings in a hierarchical manner, moving from overarching and structural considerations to nuanced and personalized strategies.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting diagram.

Innovations at the Structural Level

Key terms relevant to structural determinants of IPV included social justice, racism, and economic inequality. Eight studies addressed at least one of these determinants, with only one addressing more than one concept within a single curriculum. Most programs (n = 6) that incorporated any content related to structural determinants of IPV focused on racial discrimination against Black men. Of these, one randomized control trial and two literature reviews recommended facilitating groups that are comprised exclusively of Black men or giving participants a choice between mixed- or same-race groups. Findings on the effectiveness of this approach are mixed: some studies found no differences in outcomes between Black and White participants, others found that participants reported feeling more comfortable in racially/culturally specific groups and that participants in culturally specific groups may be more likely to complete programming than participants in conventional racially mixed groups (Gondolf, 2008, 2011). All six studies recommended that DVIPs should draw connections between violent behavior, current and historical experiences of racial discrimination, and systems of oppression; integrate aspects of tradition, religion, and spirituality relevant to ethnic minority communities into program curricula; and employ diverse program facilitators that have personal ties to culturally specific communities. Studies suggest acknowledging how systems of oppression have rendered many racially minoritized communities powerless and emphasizing the strengths of these communities and individuals (Gondolf, 2008, 2011; Saunders, 2008; Simmons, 2006).

Two articles addressed social injustice more broadly focusing on inequities including, but not limited to, racial inequities. One randomized control trial suggested that programs should acknowledge and elaborate upon cultural issues in programming, including reactions to discrimination and prejudice, identifying as oppressed and identifying as being the oppressor, and finding peace when you feel powerless (Gondolf, 2008). The second article, a critical essay by a former DVIP participant, argued programs must build relationships with social justice organizations outside of the criminal justice system and develop common goals and strategies to reformulate the social structures within offenders’ communities that perpetuate intersectional social injustices relative to race, gender, and class (Garcia, 2010). No articles that emerged in this review addressed social injustices in any communities other than communities of Black men.

Only one article in this review addressed economic inequality. In a 2020 dissertation, Kreuziger conducted an exploratory qualitative study to investigate DVIP program components that contribute to therapeutic gains and reductions in violence. Both DVIP program facilitators and participants agreed that information and instruction on professional and economic development both during and after treatment; job acquisition assistance; job training; and sliding fee scales are vital components of a successful DVIP (Kreuziger, 2020) (Table 2).

Innovations at the Program Level

Key terms relevant to innovative practices at the program level included case management and connecting with program partners. Of the six studies that discussed case management, three stressed the importance of ensuring that participants continue to receive supportive services for both IPV-related and non-IPV-related (e.g., housing, employment, substance use) needs during and after programming because the typical length of programming (24–52 weeks) is insufficient to address the complex needs of many offenders. In two separate exploratory qualitative studies, an “after care,” or maintenance component of programming was identified as vitally important by DVIP participants themselves (Kreuziger, 2020; McGill, 2007). One suggested having an “open door policy” whereby participants can return to treatment when necessary, and the second suggested a mandatory peer mentorship program following program completion. The third, a quasi-experimental study, found that case management provided during and after treatment helps offenders maintain employment and is associated with positive treatment outcomes (Pitts et al., 2009). Other articles emphasized how a “one-size-fits-all” approach to offender treatment does not capture the complex and varying needs, problems, and strengths of offenders and their partners, and shows little effectiveness. Consequently, comprehensive intake assessments designed to clearly delineate offenders’ needs are required to facilitate the tailoring of wrap-around services (MacLeod et al., 2008). Researchers further recommended that programs should provide continued case management either in-house (when possible) or via referrals to partnering organizations. Results from a cross-sectional exploratory study suggest that services should address issues including but not limited to mental health, substance use, housing and homelessness, health/medical assistance, food insecurity, legal involvement, and child welfare (Morrison et al., 2019).

These articles suggested that program partners are vital to successful case management; thus, networking and coalition building are critical to the long-term success of violence prevention and intervention. Of the three articles that discussed program partners, one cross-sectional study and one detailed description of the Alternatives to Violence DVIP made specific suggestions about the types of organizations and individuals that DVIPs should have close partnerships with (Laviolette, 2001; Morrison et al., 2019). Examples include judges, police and probation officers, clergy, children’s advocates, victim’s advocates, human service agencies (e.g., housing, employment), and welfare agencies (e.g., TANF, SSI). The third, an exploratory qualitative study, noted that many of the agencies involved in violence prevention and intervention may operate through different philosophies or frameworks. Thus, open, respectful, frequent, and supportive collaborative efforts are critical (Magruder, 2017) (Table 2).

Innovations at the Individual Level

Key terms relevant to innovative practices at the individual participant level included screening for and addressing ACEs, and strengths-based parenting. Of all the key concepts we included in this review, ACEs were the most widely discussed. Many DVIPs are aware of the well-established relationship between ACEs and violence perpetration and are already working to “help clients identify and overcome the abusive and dysfunctional patterns of behavior they may have learned from their childhood of origin” (Babcock et al., 2016). All six of the included studies on ACEs recommend using principles of trauma-informed care to educate participants about the effects of trauma. These articles—which include two literature reviews, a longitudinal study, two cross-sectional studies, and a mixed methods study—primarily recommended doing this through cognitive-behavioral, dialectical-behavioral, or acceptance and commitment therapy (Babcock et al., 2016; Crockett et al., 2015; Cuevas & Bui, 2016; Kreuziger, 2020; Montoya-Miller, 2015; Voith, Russell et al., 2020). One cross-sectional study with 67 DVIP participants suggested that mindfulness and meditation activities may help reduce aggression (Voith, Russell et al., 2020).

Four programs, as described in two exploratory qualitative studies, and two commentaries on programmatic guidelines, focused on strengths-based parenting, asserting that fatherhood is a motivator for change in partner abusive men. Parenting-oriented programs focused on skill building to help participants take accountability for abusive behavior, break intergenerational patterns of trauma and violence, practice healthy parenting, and enhance the safety and well-being of their children (Domoney & Trevillion, 2021; Kreuziger, 2020; Scott et al., 2007; Sullivan, 2006) (Table 2).

Restoration-Orientated Programs

Key terms relevant to restorative programming included restorative justice (RJ), transformative justice (TJ), and family group counseling. One randomized control trial, one viewpoint essay, and one exploratory qualitative study described how traditional RJ practices, such as family group conferences, circles of peace, and healing circles, can be applied to IPV-offender treatment (Mills et al., 2006, 2013; Zakheim, 2011). Authors explained that these practices generally involve the offender, the victim, families, and communities, and are intended to facilitate victim healing and safety, and offender accountability. Participation of supportive others is vital to help offenders develop and maintain strategic, tailored plans to change their behavior and rectify problems. Findings from these studies suggest that RJ may be more effective in addressing IPV than traditional DVIPs, and provides greater victim empowerment, agency, and satisfaction than the criminal justice process alone (Mills et al., 2006, 2013; Zakheim, 2011). While these studies emphasized the critical importance of including family and community members in restorative practices, only one publication—a critical essay by a former DVIP participant—discussed how to extend these practices to include TJ or the transformation of structures and systems that perpetuate and exacerbate violent behavior. This article stressed how and why pushing, challenging, and transforming violence outside of the DVIP classroom is necessary to effectuate large-scale, prolonged changes that promote violence reduction (Garcia, 2010).

Finally, family group counseling, which is an activity associated with RJ and highlights the value of including victims’ perspectives, was discussed in four articles (Laviolette, 2001; Portnoy, 2016; Todahl et al., 2012; Tollefson, 2001). Together, one program description, two exploratory qualitative studies, and one secondary analysis of DVIP agency case records stressed the importance of including victims and families on a voluntarily basis and when it is safe. All four articles suggest giving victims and families the option to participate in counseling sessions with the offender, and/or discuss concerns with program facilitators. One exploratory qualitative study found that victims perceived these programs to be safe and effective (Todahl et al., 2012), and in another qualitative analysis of offenders’ perceptions of treatment, DVIP participants requested that family group counseling be an optional activity (Portnoy, 2016) (Table 2).

Measuring Effectiveness

We assessed how programs measured success/efficacy and/or how they operationalized indicators of change relative to innovative program components. Of the 27 included articles, 20 provided details on measurement. In terms of indicators of success, seven used rearrest (to assess recidivism); eight used program completion, attendance, or participation; five used self-reported changes in attitudes, beliefs, motivations, or intentions; and five used self-reported changes in empathy, emotional control, use of skills, or violent behavior (i.e., cessation of violent behavior, decreases in severity, or frequency of violent behavior). Five qualitatively evaluated participant and/or facilitator perceptions of success, and five described measurements taken at intake that are not indicative of programmatic effectiveness (e.g., documenting ACEs, attachment style).

Indicators including program completion, rearrest, and attendance were not measured using validated tools, and qualitative studies that used semi-structured interview scripts did not use validated scales either. One study (Laviolette, 2001) measured recidivism and changes in attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs about violence perpetration but did not specify that any of the tools used were assessed for validity and reliability.

Six studies employed or recommended specific, validated measurement tools to assess various aspects relative to DVIP effectiveness. Babcock et al. (2016) recommended using the ODARA, SARA, or Propensity for Abusiveness Scale to assess the risk of repeat violence, and other validated tools (e.g., Danger Assessment) for evaluating abuse type, frequency, severity, impact on victims and families, motivation to change, and relevant personality, relationship, and social factors (Babcock et al., 2016). Crockett et al. (2015) utilized multiple scales, including the Perceived Stress Scale, Anger Readiness to Change Scale, State Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Measure of Control in Romantic Relationships Scale, Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale, and the Marlowe Crowne Social Desirability Scale to gage emotional control and violent behavior (Crockett et al., 2015). Macleod et al. (2008) used the BIP Process Survey to assess changes in attitudes and beliefs (MacLeod et al., 2008). McGill (2007) used the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale, the General Emotional Intelligence Scale, and the Safe at Home Readiness for Change Survey for empathy, emotional intelligence, and change stages, respectively (McGill, 2007). Voith, Russell et al. (2020) used the ACEs Questionnaire, the Self-report Inventory for Disorders of Extreme for Trauma Experiences, and the Revised Mindfulness Self-Efficacy Scale to assess emotional control, social skills, and accountability (Voith, Russell et al., 2020). Finally, Sullivan (2006) emphasized the need to develop and validate tools for assessing parenting intervention program effectiveness in IPV cases (Table 2).

Discussion

The information summarized in this review suggests only a handful of DVIPs across the United States and abroad are exploring or adopting evidence-informed approaches that prioritize principles of social and structural determinants of violence, trauma-informed care, restoration, and social justice. Some programs draw connections between ACEs and IPV perpetration and focus on disrupting intergenerational patterns of violence using trauma-informed practices and focusing on positive parenting and skill building. While this shift is promising, more support in terms of curriculum development and widespread uptake of innovative programming is needed to help offender treatment programs evolve more holistically and successfully prevent and respond to IPV perpetration (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Critical Findings.

| • Only a handful of DVIPs are adopting evidence-informed approaches that prioritize social and structural inequities and determinants of violence, trauma-informed care, restoration, and social justice. |

| • There is a need for more inclusive and restorative DVIP programs that consider the diverse characteristics and circumstances of IPV offenders. |

| • Most articles do not describe how programs should address social and structural issues in programming beyond group conversations and building partnerships with social justice-oriented organizations. Examples of activities and actionable ways for practitioners to address social/structural determinants of violence are needed |

| • DVIPs use inconsistent and inappropriate tools and methods to measure program effectiveness. |

Note. DVIPs = Domestic Violence Intervention Programs; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Table 4.

Implications for Practice, Policy and Research.

| • Innovative programming should educate participants about how structural and social injustices intersect to produce stress and violent behavior. |

| • DVIPs should make their curricula and materials, including examples of activities and actionable ways for practitioners to address innovative issues accessible to the public. |

| • Federal and state funding should be allocated to the development, training, and evaluation of innovative DVIPs. |

| • Future studies should investigate additional known correlates of violent behavior when exploring whether and how DVIPs are employing innovative strategies. |

| • The development of more reliable, accurate, and innovative measurement tools and methods is needed to appropriately evaluate domestic violence intervention program efficacy. |

Note. DVIPs = Domestic Violence Intervention Programs.

While traditional feminist-oriented programs do address structural gender inequities, they were designed for heterosexual male offenders. These models lack important nuance for intervention with female offenders (Miller, 2005), or for LGBTQ+ couples, who experience IPV at similar or higher rates than heterosexual, cis-gender couples (Edwards et al., 2015). A more inclusive and restorative DVIP format requires consideration of the diverse characteristics and circumstances of offenders, and the involvement of their partners, families, and communities (Nicolla et al., 2023) (Table 3).

We found that structural and systemic racism is addressed relatively often in the few programs that claim to utilize alternative treatment models. This suggests that programs are aware of and putting effort into addressing the influence of structural racism on violent behavior, particularly among Black men. However, very few programs address social injustice and systemic inequalities that disproportionately affect other marginalized groups. More programs should consider programming that recognizes the structural and systemic oppression of sexual and gender minorities, immigrants, indigenous populations, people with disabilities, and unhoused individuals. Furthermore, very few programs consider structural inequities related to economic strain, educational attainment, employment, housing, and wage discrimination. Innovative programming should educate participants about how structural and social injustices intersect to produce stress and other mediators of violent behavior and work to help offenders overcome associated barriers. A striking gap is that even when they acknowledged the importance of structural issues, most articles did not elaborate upon how programs should address structural issues in programming beyond group conversations and building partnerships with social justice-oriented organizations. Program materials are rarely accessible to the public; thus, details about how to incorporate these innovative practices into programming are scarce. More examples of activities and actionable ways for practitioners to address these issues are needed (Tables 3 and 4).

Evidence on the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of RJ- and TJ-informed practices, including family group counseling, is growing, and suggests that it may be a preferred type of intervention among IPV survivors (Decker et al., 2020; Kim, 2021; Mills et al., 2019). Programs that are already doing family group counseling, or involving survivors and families in programming in some way may consider expanding and formalizing these practices to align with RJ practices. Better still would be adopting transformative practices by partnering with other community organizations to transform local systems, norms, and community practices to support offenders in abstaining from violence and facilitate victim healing. Notably, some DVIP and victims’ services providers are hesitant to incorporate aspects of RJ and TJ into offender treatment, citing concerns related to survivor safety, re-traumatization, and power imbalances inherent to IPV (Campbell et al., 2023; Curtis-Fawley & Daly, 2005; Proietti-Scifoni & Daly, 2011). As such, RJ and TJ should be initiated on a case-by-case basis, align with the legal and social circumstances of the offender (e.g., consider protective or no-contact orders), and be tailored to the specific needs and desires of survivors while emphasizing survivor safety and autonomy. Evidence-based frameworks such as RNR and PEI (Bonta & Andrews, 2007; Hilton & Radatz, 2018; Radatz & Wright, 2016; Radatz et al., 2021) and guiding principles recommended by nationally recognized organizations, like the Center for Court Innovation (Cissner et al., 2019) can guide practitioners in developing tailored treatment plans that are sensitive to offenders’ unique criminogenic and social/structural needs (Table 4).

Inadequate funding, limited staff capacity, and a lack of buy-in from critical community and institutional partners (e.g., state-wide organizations that support and regulate DVIPs) are barriers for many programs to effectuate change (Campbell et al., 2023). In response to these barriers, programs may introduce low-cost activities to start, like discussions and support groups. However, to effectively target the social and structural determinants of violence that impact IPV, interventions inevitably must expand these efforts beyond educational initiatives by implementing evidence-based curriculums and activities that target mechanisms, like intentions and self-efficacy, which are determinants known by health behavior theorists to directly influence behavior change (Ajzen, 1991; Champion & Skinner, 2008).

Finally, efforts to develop novel program curricula that integrate social, structural, and restorative interventions with other evidence-based programming (e.g., RNR or PEI) is needed. Such curricula should address a spectrum of social and structural issues including but not limited to income inequality, community disadvantage, systemic marginalization, racism, poverty, adverse experiences of trauma and stress, parenting dynamics, and restorative and TJ. Program components should encompass tailored psychological and substance use support, ongoing individualized case management, social, emotional, and instrumental support, inter-agency partnerships and collaborations, acknowledgment and dismantling of oppressive policies and practices, consideration of unique cultural contexts in both individual and group settings, implementation of circles of peace and victim–offender dialogs when appropriate, active communication with survivors, family inclusion in programming, and positive parenting skill building. The development of such curricula should be ideally undertaken through collaborative endeavors involving research experts, practitioners, survivors, and offenders. It is imperative that innovative programs undergo comprehensive evaluation using appropriate measures to assess both the extent of curriculum implementation and fidelity, as well as the overall effectiveness of the program. Ideally, the application of rigorous research methodologies, such as randomized control trials or pre–post-test longitudinal studies, should be considered, with adaptability based on local resource availability and specific needs considered (Table 4).

There are at least two limitations to this review. First, some studies were unavailable because of a lack of institutional access to particular journals. It is possible that the inclusion of additional studies would change the results slightly. Nevertheless, the central finding—that many DVIPs that have been operational in the last two decades are not incorporating innovations that focus on social and structural correlates of IPV perpetration into practice—would be unlikely to change with the inclusion of a handful of additional studies. Second, it is possible that if we had included different search terms, we would have identified additional articles that discussed other innovative practices. It is possible that DVIPs are employing other types of novel programming that reflect different key concepts or correlates of IPV and these were not captured in our search. However, given the relationship between structural and social inequities, ACEs, and IPV perpetration, findings suggest that most programs are not addressing important known social and structural predictors of violent behavior. Future studies may seek to include more known correlates of violent behavior to explore whether programs are employing innovative strategies in other ways.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified relatively few studies that describe or assess the effectiveness of DVIPs that incorporate social and structural innovations beyond the standards set forth by the feminist psycho-education models of the original DVIP curricula. Furthermore, we found that DVIPs measure effectiveness inconsistently, and often use insufficient measures, like re-arrest and program completion rates, which are not designed to gauge DVIP implementation and outcomes. More research is needed to reveal what other types of novel programming DVIPs may or may not be engaging in and how effective these alternative curricula are. Priority should be placed on developing recommendations for how DVIPs can alter current practices to align with evidence-based techniques that address known social and structural causes of violence and implement plans and activities to more effectively prevent and mitigate IPV perpetration.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Scarlett Hawkins, MS, Savanah Morgan, JD, Bridget Nelson, BA, Erika Redding, MSPH, and Julia Weinrich, MPH for their contributions to this research.

Author Biographies

Julia K. Campbell, MPH, is a doctoral student and graduate research assistant at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is interested in community and policy-based approaches to the prevention of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and firearm violence.

Sydney Nicolla, PhD, is an assistant professor of Strategic Communications and health communication researcher at the School of Communications at Elon University in North Carolina. Her research is focused on using digital and social media to improve adolescent health, particularly in the area of gender-based violence.

Deborah M. Weissman, JD, is the Reef C. Ivey II distinguished professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law. Her research, teaching, and practice interests include gender-based violence law, immigration law, and human rights in the local and international realms. She is the Chair of the North Carolina Commission on Domestic Violence.

Kathryn E. (Beth) Moracco, PhD, MPH, is an associate professor in the Department of Health Behavior at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and the associate director of the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center. She is an applied, mixed-methods public health researcher with expertise in formative research, intervention development, and evaluation, primarily focused on gender-based violence.

The terms “perpetrator” and “offender” are used interchangeably throughout the literature on DVIPs to refer to an individual who commits acts of domestic violence.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported, in part, by the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center, which is partly supported by grant number R49/CE000196 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was also supported, in part, by funds from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost.

ORCID iDs: Julia K. Campbell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2674-1830

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2674-1830

Sydney Nicolla  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3167-6623

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3167-6623

References

*Indicates publication that is included in the review.

- Aaron S. M., Beaulaurier R. L. (2017). The need for new emphasis on batterers intervention programs. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(4), 425–432. 10.1177/1524838015622440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]