Abstract

Aim

This review aims to summarize the epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for mucormycosis. The goal is to improve understanding of mucormycosis and promote early diagnosis and treatment to reduce mortality.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted, focusing on recent studies and data on mucormycosis. The review includes an analysis of the disease’s epidemiology, etiology, and pathogenesis, as well as current diagnostic techniques and therapeutic strategies.

Results

Mucormycosis is increasingly prevalent due to the growing immunocompromised population, the COVID-19 pandemic, and advances in detection methods. The pathogenesis is closely associated with the host immune status, serum-free iron levels, and the virulence of Mucorales. However, the absence of typical clinical manifestations complicates diagnosis, leading to missed or delayed diagnoses and higher mortality.

Conclusion

An enhanced understanding of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation of mucormycosis, along with the adoption of improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, is essential for reducing mortality rates associated with this opportunistic fungal infection. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are critical to improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: Mucormycosis, COVID-19, clinical characteristics, therapeutic strategy

KEY MESSAGES

The incidence of mucormycosis has increased following the COVID-19 pandemic.

The presence of the halo sign and reverse halo sign may indicate the onset of pulmonary mucormycosis.

Early implementation of molecular diagnostic methods, such as mNGS and qPCR, may improve the early diagnosis rate of mucormycosis.

Isavuconazole and posaconazole can also be considered as first-line treatments for the initial management of mucormycosis.

Introduction

Mucormycosis is an opportunistic infection caused by filamentous molds of the order Mucorales. The primary routes of infection include inhalation of Mucorales spores through the respiratory tract, ingestion of contaminated food or invasion through skin wounds. The main pathogens are Rhizopus, Lichtheimia, and Mucor. Mucormycosis often occurs in immunocompromised individuals and usually progresses rapidly with high mortality (>40%) [1–3]. In the past 30 years, the increasing number of immunocompromised individuals and improvements in diagnostic techniques have led to increased morbidity of mucormycosis [4,5]. Several predisposing factors can contribute to the onset of mucormycosis, including immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus (DM), hematological malignancies (HMs), high-dose corticosteroid use, severe trauma, iron overload, malnourishment, and neonatal prematurity [6,7]. However, the lack of specific clinical manifestations and effective diagnostic methods has led to delayed treatment and increased mortality [3]. Owing to the ongoing prevalence of COVID-19, an increase in mortality remains a plausible prognosis [8]. Early diagnosis and timely effective treatment are critical for reducing mortality due to mucormycosis, so it is necessary to improve the awareness and clinical vigilance of mucormycosis. Herein, we review the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment of mucormycosis to aid in early diagnosis and treatment and reduce mortality.

Pathogens, epidemiology and risk factors

The order Mucorales contains a large number of species. The most common pathogens of mucormycosis include Rhizopus, Mucor, and Lichtheimia, which account for 90% of all cases [9]. Rhizopus spp. are the most prevalent pathogens responsible for >70% of mucormycosis cases globally [7,10]. Mucor spp., Lichetheimia spp., Cunninghamella spp., Apophysomyces spp., Rhizomucor spp., and Saksenaea spp. complexes are commonly observed in clinical practice [6]. Mucor spp. are the secondary causative agents in Africa, Asia, and Europe, followed by Lichtheimia spp. in Europe and North and South America [11]. However, Apophysomyces spp. are secondary pathogens in India [8]. There are also several uncommon pathogens reported in Asia, such as Rhizopus homothallicus and Mucor irregularis [12].

The global prevalence of mucormycosis remains undefined because of few population-based investigations [3,13]. Population-based laboratory active surveillance in the United States determined the cumulative incidence of mucormycosis to be 1.7 per million person-years [14]. The index constantly increased, and by 2016, the number of hospitalizations associated with mucormycosis had reached 16 per million person-years [15]. In addition, there are significant epidemiological differences between developed and developing countries [16]. The incidence of mucormycosis in India has always been much higher than the world average, with a prevalence of approximately 70 times the global incidence [17]. In particular, the number of COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) patients increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. An increase in the annual infection rate or incidence has also been observed in China [18], Pakistan and Iran [19,20]. The incidence of mucormycosis has also increased in developed and high-income countries [8], but the incidence in developed countries is lower than that in developing countries [21]. Similarly, mucormycosis cases have increased in developed and high-income countries [3]. The incidence of mucormycosis has increased in multiple European countries (France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Spain) in the last decade [22]. The incidences were 6.3 and 0.62 per 100,000 admissions, respectively, in Geneva [23] and Spain university hospitals [24].

Common risk factors for mucormycosis include DM, HM, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), solid organ transplant (SOT), long-term neutropenia, corticosteroid use, deferoxamine therapy [6], preterm birth and low birth weight [7,25]. Posttuberculosis and chronic kidney failure have also emerged as new risk groups [3]. HM and organ transplant recipients were the major risk factors in developed countries, whereas uncontrolled DM and inappropriate corticosteroid use were the major risk factors in developing countries [13,22]. Moreover, the use of antifungal drugs without activity against Mucorales, such as fluconazole, voriconazole, and caspofungin, may be related to mucormycosis occurrence [26,27]. Other conditions predisposing individuals to mucormycosis, such as injection drug use, diarrhea, malnutrition, and hepatic disease; however, they are relatively rare [7,25,26]. Construction work, contaminated air filters, and various healthcare-associated procedures and devices may also be associated with the onset of nosocomial mucormycosis [28]. In addition, immune suppression caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection or other viral infections, imbalances in the nasal microbiota, seasonal changes in temperature and humidity affecting particle concentrations in the air and mucor growth can all induce mucormycosis [29].

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of mucormycosis remains unclear, although multiple hypotheses have been proposed. Hyperglycemia may increase the risk of fungal infections that are potentially linked to fungal invasion. Increased intake of iron ions may also constitute a significant pathogenic mechanism. The influence of COVID-19 on the immune system may have contributed to the occurrence of mucormycosis during the pandemic [30].

Spore coat protein (CotH) mediates Mucor invasion

Previous studies have shown that the spore coat protein CotH expressed on the cell membrane of Mucorales spores is an important virulence factor [21,31–34]. Mucorales invade nasal epithelial cells via CotH3, which recognizes glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), and CotH7 interacts with integrin α3β1 receptors expressed on the membrane of alveolar epithelial cells, mediating invasion [33,34]. In the pathogenesis of pulmonary mucormycosis, integrin β1 mediates the phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on tyrosine residue 1068 after binding of integrin α3β1 to CotH7 [32]. The subsequent activation of EGFR signaling might lead to changes in the expression of 34 downstream target gene loci. Among these genes, the mir21 gene is overexpressed in lung epithelial cells via downregulation of the mir21 repressor gene. The mir21 gene is more functional and may be involved in Toll-like receptor (TLR)2-mediated signaling regulation and in the differentiation of monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages and T helper 2 cells (Th2 cells) and in macrophage activation [35]. This process induces and reinforces the invasion and damage of alveolar epithelial cells by Mucorales [36]. This finding suggested that EGFR signaling plays an important role in Mucorales invasion of lung epithelial cells and that EGFR inhibitors may be able to treat pulmonary mucormycosis [36], but more detailed mechanisms have yet to be explored. Infection-induced transcriptome analysis revealed the involvement of the interleukin-22 (IL-22) and interleukin-17A (IL-17A) pathways in mucormycosis [36].

Iron ion uptake: a crucial mechanism in mucorales infection

The ability of Mucorales to acquire iron ions from the host is crucial for their metabolic processes, cell growth, and development [37]. In a healthy host, iron homeostasis is efficiently maintained by iron-sequestering proteins such as transferrin, ferritin, and lactoferrin [38]. Only a small proportion of iron is present in the serum as free iron [38]. Therefore, Mucorales likely employ novel mechanisms to acquire iron ions from xenosiderophores, such as blocking these sequesters or generating an environment that weakens the iron-sequester bond. Fungi commonly produce and excrete iron-specific chelators known as siderophores with high affinity for iron, such as rhizoferrin (from Rhizobium oryzae) [21]. The siderophores that bind to iron are absorbed and internalized by fungi [39]. Additionally, ferric iron uptake from heme or direct intracellular uptake of heme is achieved by a reductive iron uptake system present on the fungal cell surface, which consists of ferric reductase, multicopper ferroxidase, and iron permease [40,41]. One study revealed that Rhizopus oryzae can acquire its own iron requirements even at extremely low environmental iron concentrations due to low iron concentrations, which induces the overexpression of the high affinity iron permease gene FTR1 [42]. A clinical study using serum ferritin as an indicator of free iron showed that higher serum free iron levels were associated with the severity of mucormycosis and were not affected by diabetes comorbidities [43]. Deferiprone is a potent iron chelator. In an in vitro experiment, deferiprone exhibited significant cidality when coincubated with Mucorales for 48 hours [44]. In mouse models of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), deferiprone and LAmB showed similar effects on improving survival and reducing the fungal load in the brains of mucormycotic mice. This protective effect disappeared with an increase in serum free iron levels and reversal of the effect of deferiprone [44]. Therefore, serum free iron levels are associated with mucormycosis, and potent iron chelators may be potential anti-mucor agents. However, ordinary iron chelators, such as desferriamine, which has been proven to be related to the onset or severity of mucormycosis, may be ‘captured’ by high-affinity iron permeases specific to Mucorales to become xenosiderophores [45].

Relationship between COVID-19 and mucormycosis

SARS-CoV-2 infection-mediated immune disorders, lung tissue damage and treatment for COVID-19, including invasive interventions and immunosuppressive therapy, increase the risk of secondary bacterial and fungal infections. COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) gained widespread attention due to a surge of mucormycosis cases during the second wave of COVID-19 in India [18]. Immunological perturbations may play an important role in CAM pathogenesis. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection might result in broad immune cell reduction, mainly involving T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs) [46,47]. SARS-CoV-2 infection can prevent DCs from maturing and reduce the secretion of cytokines such as type I interferon (IFN-I), and acute SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to functional impairment of both CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets, significantly inhibiting the expression of granzyme B, perforin, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [48]. In addition, hyperinflammation caused by the viral immune response following SARS-CoV-2 infection [49,50] also contributes to the establishment of a permissive environment for coinfection with fungi [51,52]. However, the prognosis of non-COVID-19 patients is worse than that of post-COVID-19 patients, which may be related to the more severe T-cell immune dysfunction in non-COVID-19 patients [53]. In addition, the immune response associated with severe COVID-19 is similar to that associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), and the use of therapeutic glucocorticoids may promote mucormycosis. Since humoral immunity plays an important role in fighting fungal infections, the reduction in the number and function of B cells caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection may also favor fungal infections. Figure 1 shows the connection between the pathogenic mechanisms of COVID-19 and mucormycosis.

Figure 1.

The pathogenesis of COVID-19-associated mucormycosis. Illustration: After binding to the ACE2 and GPR78 receptors expressed on the surface of oropharyngeal epithelial cells, SARS-CoV-2 induces cell death and the release of inflammatory mediators, damaging epithelial cells. This leads to the disruption of intercellular connections and dysfunction of epithelial cell function, establishing favorable conditions for the invasion of mucormycosis cells. Furthermore, the virus itself, by damaging the human blood glucose regulation system, can result in hyperglycemia, which is exacerbated by corticosteroids used to treat COVID-19. Hyperglycemia induces the upregulation of GPR78 expression on epithelial cells, increasing their susceptibility to mucormycosis invasion. Additionally, impairment of the immune system by COVID-19, such as a reduction in CD4+/CD8+ T-cell counts and dysfunction resulting in decreased expression of cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF, weakens resistance to Mucorales and renders individuals susceptible to infection.

Clinical characteristics of mucormycosis

The clinical types of mucormycosis are divided into pulmonary mucormycosis (PM), rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM), disseminated mucormycosis, cutaneous or soft tissue mucormycosis (CM), gastrointestinal mucormycosis (GM), and other rare forms, such as renal infection, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and peritonitis [2,54]. ROCM is the most prevalent, especially in patients with DM, followed by PM. ROCM was more common in diabetic patients. PM is often observed in patients with long-term neutropenia and treatment of severe graft-versus-host disease and diabetic ketoacidosis [55–57]. CM is the third most common type of mucormycosis and can occur in patients with no identified underlying disease, DM or HM [58]. Trauma is the most common mode of CM transmission. Furthermore, CM and GM occur more frequently in children [59], especially in malnourished and premature children [60]. In China, GM is often caused by chronic gastrointestinal ulcers [61]. The clinical characteristics of mucormycosis are diverse. The detailed clinical manifestations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The clinical manifestations of mucormycosis.

| Manifestations |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Signs | Imaging | References | ||

| Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis | Nasal cavity | *stuffiness Nasal discharge Epistaxis |

*Crusting and ulceration *Discharge Active epistaxis |

CT: Rhinosinusitis Orbital extension Intracranial extension: Brain infarct Intracranial bleed Bone destruction MRI: Hyperintensity shown in T2 signal in infected site. Proptosis of eyes, diffuse involvement of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinus, orbital apex may extend into the cavernous sinus. Brain abcess |

[62,63,64,65,66,67,68–70,71] |

| *Eye and adnexas | *Eye pain/Headache *Lid edema *Diminution of vision Proptosis Ptosis Diplopia |

Lid edema *Decreased visual acuity *Proptosis Chemosis *Ptosis Ophthalmoplegia |

|||

| Face, Neurological system Oral cavity |

Facial pain *Headache Facial ulcers One sided weakness Altered sensorium Facial deviation decreased Facial sensation Oral ulcers |

Ulceration Hemiplegia *Facial palsy *Altered sensorium Decreased facial sensation Discoloration Crusting and ulceration |

|||

| Pulmonary mucormycosis | Fever *Broenish or black sputum Chest pain *Hemoptysis Worsen cough |

No specific signs | *Reversed halo sign *Mycotic aneurysm Diffuse and mixed ground-glass opacity Thick-walled cavity necrotizing pneumonia Large consolidation or Bird’s nest signa Multiple large nodules(>1 cm) Pleural effusion |

[56,63,64,68,72,66,67,57,65] | |

| Disseminated mucormycosis | Two or more noncontiguous organs involved. Lung are the most commonly affected site, followed by the central nervous system, nasal sinuses, liver, kidneys, bones and joints. Systematic fever with pain and dysfuncation of infected sites are common clinical manifestations. Hepatic mucormycosis: hepatalgia, bellyache Renal involvement: hematuresis, lumbago,Sterile urine Bones and joints involvement: restricted movements, local pain, tenderness, and/or swelling, and cellulitis/abscess |

Hepatic involvement presents as a mass-like lesion with extensive liver infraction as well as Budd-Chiari syndrome or veno-occlusive disease. CT image commonly presents liver abscesses and hepatic nodules. Renal mucormycosis: ultrasound showed mass in a kidney, and the single kidney is generally involved. Heterogeneous mass can be seen on CT image. Bones and joints mucormycosis: Osteoarticular abnormalities included osteolytic lesions, bone destruction/erosion, lucencies, and increase of radionuclide uptake MRI demonstrated low signal intensity on T1 weighted and patches of high signal intensity on T2 weighted images. |

[7,73,74,69,70,75,76,77,78] | ||

| Cutaneous/soft tissue mucormycosis | acute necrotic: erythema, swelling, plaques, pustules, ulcers, necrosis, and eschars | [79–82] | |||

| subacute or chronic cutaneous mucormycosis: skin plaques and swelling, gradually leading to ulceration | |||||

| Gastrointestinal(GI) mucormycosis | Fever, nausea, abdominal pain, GI bleeding, and perforation Large ulcers with necrosis, adherent, thick, green exudate |

A gaint ulcer, the greater curvature, fundus and antrum under gastrointestinal endoscopy | [83,84,85,85] | ||

Headache and nasal congestion are the initial symptoms of ROCM. The paranasal sinuses and nasal mucosa are the primary sites of infection. Due to the angioinvasive nature of hyphae, Mucorales gradually invade and destroy surrounding tissues. Periorbital abscesses, bone destruction, and soft tissue swelling around the infection site are common computed tomography (CT) findings in ROCM [65]. Manifestations of orbital apex syndrome, such as exophthalmos, eyelid ptosis, and decreased vision, may occur if Mucorales invades orbital tissue. Intracranial infections may present with cranial nerve palsy III–VI, hemiparesis and hemiplegia, altered sensorium, seizures, and coma [65]. Once a lesion invades brain tissue, patient mortality increases significantly.

There are no specific symptoms or signs of PM. Fever, cough, and hemoptysis are common in PM patients, and superficial lymphadenectasis may occasionally be observed [86]. Consolidation, cavitation, patchy shadows, and pleural effusion can be observed on chest CT [72]. Halo and reverse halo signs on CT images may indicate Mucorales infection [72]. Features similar to those of CT images can be seen in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can be used to detect lesions during early-stage infection and facilitate mucormycosis staging [87,88]. PM is also associated with poor prognosis in patients with HMs. Edema of the mucosa, hyperemic edema, bronchial stenosis, and obstruction due to mucosal necrosis and uneven mucosa or mass were observed under bronchoscopy, which are particularly prone to being confounded with neoplastic conditions or pulmonary tuberculosis [89]. There are also a few reports suggesting that patients may present with isolated central airway involvement (trachea and major bronchi) without parenchyma or segmental bronchial involvement, and patients may present with productive cough, hemoptysis, and hoarseness [90].

Disseminated mucormycosis refers to a form of mucormycosis that simultaneously involves two or more noncontiguous organs. The lungs are the predominant organs infected with Mucor, followed by the central nervous system (CNS), liver, and kidneys [73,74]. Hepatalgia and hematuria are the principal clinical manifestations involving the liver and kidney, respectively. The involved organs usually exhibit necrotic inflammation and vascular invasion, which lead to organ dysfunction and symptoms of bleeding and ischemia [7]. According to two wide-scale studies, the mortality rate of disseminated mucormycosis is >90% [7,91].

CM usually involves subcutaneous tissue, and the symptoms or signs primarily include skin erythema, swelling, ulcers, pustules, necrosis, and eschars [58]. GM often has an insidious onset, with symptoms resembling those of other gastrointestinal infections, such as anemia, hematochezia, nausea, and vomiting.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mucormycosis is difficult, mainly based on: (1) host risk factors; (2) clinical manifestations of mucormycosis; (3) microbiological evidence (sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, bronchial brush extracts, or sinus puncture extracts found Mucorales by etiological diagnosis); and (4) histopathological evidence (Mucorales were found by etiological or histopathological diagnosis from tissues or other specimens taken from sterile sites). Possible mucormycosis: 1 + 2; probable mucormycosis: 1 + 2 + 3; confirmed mucormycosis: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 [92,93].

A positive etiology is necessary for a definitive diagnosis of mucormycosis. Culturing, microscopic examination of smears, and biopsy of lesions, including specific stains (Blankophor, Calcofluor White) [94], represent the most convenient diagnostic methods for determining the etiology in clinical settings [3]. Pathologically, Mucor is characterized by broad, irregular, and aseptate hyphae surrounded by necrotic tissue or inflammatory cells, as observed under a microscope. Angioinvasion, neural invasion, and thrombosis are commonly observed in lesions [62,95,96]. If Mucor spores or hyphae are detected, subsequent species identification should be performed [3,97,98]. Culture is the gold standard for microbial diagnosis, and antifungal susceptibility testing can be performed. However, due to the lack of clinical data, antifungal susceptibility testing for the management of mucormycosis is not recommended. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) [99] and molecular-based methods can be used for culture isolate identification. Serological diagnostic methods such as (1,3)-β-D-glucan (BDG) and serum galactomannan detection are not used to diagnose mucormycosis but can be used to differentiate invasive aspergillosis [100].

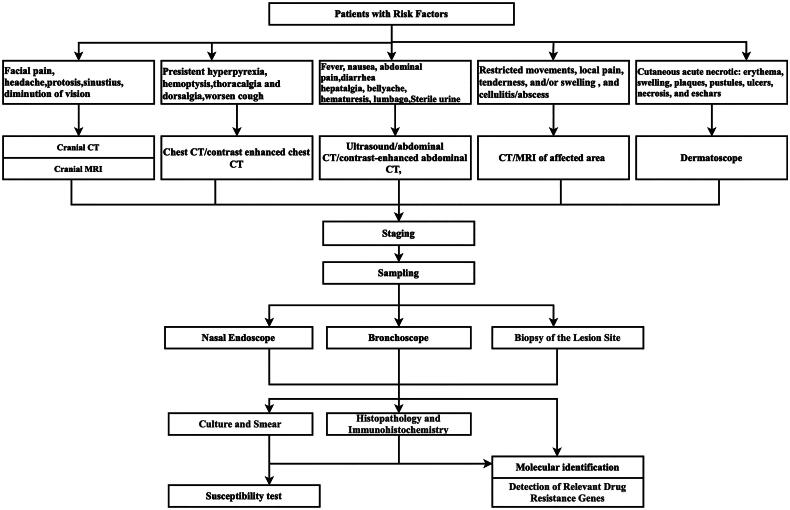

Molecular biological examination of clinical specimens, including quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), is an important supplementary method for histopathological and microbiological diagnosis. Recent studies have shown that the detection of Mucorales in serum, body fluids, tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with suspected mucormycosis by qPCR has high sensitivity and specificity (85%–100%). Because CotH is uniquely and universally present in Mucorales, CotH may be a potential target for the molecular diagnosis of mucormycosis. Animal studies have shown that it can be detected in plasma and urine as early as the fourth day after infection, but further clinical specimens are needed for confirmation. mNGS is also increasingly used to assist in the clinical diagnosis of invasive mucormycosis [101], but similar to PCR, the false positive rate is higher than that of traditional methods, and it needs to be integrated with risk factors, clinical characteristics and other pathogenic test results. Figure 2 shows the diagnostic pathway for mucormycosis.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic pathway of mucormycosis. Comments: For individuals at high risk, proactive measures following this protocol are recommended. Even in individuals without underlying disease, suspected mucormycosis can be diagnosed early by referring to this protocol.

There are many diagnostic techniques for Mucorales that are still being studied, such as monoclonal antibodies (2DA6) that are highly reactive to purified Mucor sp. fucomannan [102], lateral flow immunoassays that can quickly and accurately detect Mucorales in mouse models [102], and volatile metabolite sesquiterpenes that can distinguish mucormycosis from aspergillosis [103]. Mold-reactive T cells, CD154+ T cells, are significantly elevated in patients with invasive fungal infections [104]. In addition, CRISPR–Cas technology is a promising molecular diagnostic technology for Mucorales [105]. However, more clinical data are needed for these diagnostic techniques.

Treatment

Treatment strategies for mucormycosis emphasize a comprehensive approach, including surgery, systemic antifungal therapy, supportive care and control of the underlying disease, such as strict glycemic control and rational use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive drugs [56,106]. There is no standard duration of treatment for mucormycosis; as a principle, antifungal therapy should be continued until resolution of all clinical symptoms, laboratory and imaging, and reversal of immunosuppression.

Surgery

For mucormycosis treatment, many guidelines [3,56,106] have suggested radical surgical debridement as the first-line therapy. A meta-analysis [57] showed that surgery was associated with better outcomes in ROCM patients without central nervous system (CNS) involvement. However, surgery did not significantly affect the survival of ROCM patients with CNS involvement. It has been [107] reported that patients who underwent surgical intervention before disease progression to the dural interface at the skull base recuperated quickly postoperation, with a significantly reduced incidence of neurological sequelae. Therefore, appropriate and repeated surgical debridement may improve the prognosis of patients with ROCM. Early radical surgery can prolong the survival of patients with ROCM. The scope of debridement should be extensive, encompassing the margins of the normal tissue adjacent to the lesion [106]. For ROCM, the outcome of surgical treatment is also related to whether the skull base is involved and whether there is intracranial diffusion. Therefore, subtype classification helps to stratify the disease, thus facilitating surgical planning and improving prognosis [104]. Surgical treatment for pulmonary mucormycosis includes open surgery (thoracotomy, lobectomy) and minimally invasive surgery (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery). Surgical resection and minimally invasive surgery can significantly improve the survival rate of patients with PM and are strongly recommended. Bronchoscopic debridement also contributes to improved prognosis [108,109], but massive bleeding can occur. In addition, some studies have indicated that surgery does not always increase the survival rate of patients with mucormycosis if their predisposing conditions, especially HM, are not reversed [110]. In senior patients with multiple underlying diseases, neutropenia and platelet counts lower than 50,000 cells/µL may be associated with increased postoperative mortality [3,6,111,112]. Cutaneous mucormycosis generally has a better prognosis, and antifungal agents combined with surgical debridement and/or vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) drainage shorten the recovery time compared with systemic antifungal drugs alone [113].

Antifungal agents

Amphotericin B formulations

Amphotericin B is the most active drug against Mucorales in vitro. Multiple international guidelines recommend LAmB as a first-line treatment for mucormycosis. Because amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmBD) has more adverse effects, it is only used when other antifungal drugs are unavailable. Previous studies have shown that LAmB can be successfully used in different clinical types of patients with mucormycosis. However, AmBD alone has also shown efficacy in the treatment of mucormycosis, and combined surgical debridement has better therapeutic efficacy. A meta-analysis [114] showed that patients treated with either AmBD or LAmB experienced adverse reactions, including hypokalemia, mild to moderate renal impairment, and mild liver impairment. One patient developed acute renal failure after receiving LAmB. The adverse reactions to AmBD appear to exhibit heterogeneity, with some patients who tolerate the drug showing no significant hepatic or renal impairment even after long-term administration of high doses [114]. Because AmBD can be excreted from the urine and feces of a prototype [115], AmBD may be a potential drug for treating mucormycosis of the urinary system. The recommended doses of AmBD for the treatment of mucormycosis (excluding craniocerebral mucormycosis) are 0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day and 1.0-1.5 mg/kg/day for craniocerebral mucormycosis. LAmB can be used at higher doses than AmBD. A dose of 5–10 mg/kg/day is strongly recommended for all organ infections, but the recommended therapeutic dose for central nervous system infections is ≥10 mg/kg/day. Doses <5 mg/kg/day and >10 mg/kg/day are marginally recommended because of decreasing antifungal activity or increasing nephrotoxicity [116,117]. In addition, the topical use of amphotericin B has also shown efficacy in combination with systemic antifungal therapy. Intensive intravitreal LAmB injections for treating Mucor chorioretinitis [118] and subcutaneous LAmB injections [119] have demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy. LAmB atomization and infusion via fiberoptic bronchoscopy can also be used to treat PM. Recently, a novel lipid nanocrystal (LNC), oral amphotericin B (MAT2203; Matinas Biopharma), was developed [120]. Randomized controlled trials have shown that the LNC formulation exhibits antifungal activity, similar survival rates, and lower toxicity than IV-administered amphotericin B [120]. This finding suggests a new direction for the development of antifungal drugs.

Posaconazole

Among the azole drugs, only posaconazole and isaconazole showed significant activity against Mucorales in vitro. Posaconazole (POS) is a broad-spectrum triazole [121] that inhibits fungal enzymes and 14α-ergosterol demethylases and blocks cell membrane synthesis [122]. Posaconazole is currently available in three dosage forms: posaconazole oral suspension (OS), posaconazole delayed-release tablets (DR) and intravenous posaconazole (IV), the latter two being new formulations (POSnew). POSnew was developed and leads to better bioavailability and drug exposure [123], and POSnew exhibits pharmacokinetic advantages with less interpatient variability than the suspension formulation [124]. The guidelines moderately recommend DR-POS and IV-POS as first-line therapies [3]. The overall success rate of posaconazole in treating mucormycosis was 54% [125]. A retrospective study showed that POSnew has a better response, lower 42-day all-cause mortality, and fewer side effects than AmB in the treatment of mucormycosis, and POSnew may be an alternative for the treatment of invasive mucormycosis. Moreover, posaconazole is occasionally used in children, and the median dosage of 21 mg/kg was safe and tolerable [126]. POSnew monotherapy was recommended as a salvage treatment (level BII) [106] for ECIL-6 in 2016. A patient with mucormycosis who received a heart-kidney transplant did not respond to AmBD treatment, and the clinical outcome improved with posaconazole salvage therapy [127]. For immunocompromised patients, particularly those with neutropenia and graft-versus-host disease, DR-POS and IV-POS can be used as primary prophylactic medications [3,128]. Posaconazole-based prophylaxis significantly reduces the risk of IFDs and prolongs the infection-free survival period [129]. Serum concentrations of posaconazole are associated with therapeutic and prophylactic effects; therefore, monitoring of serum concentrations of posaconazole is recommended.

Isavuconazole

Isavuconazole is a novel azole agent that exerts antifungal effects by reducing ergosterol synthesis. The pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole show significant advantages compared with those of other azoles (posaconazole and voriconazole), with a substantially longer terminal half-life (184 h) and larger volume of distribution (400 L) [130]. Its increased permeability leads to increased concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in both animal models and patients with cerebral fungal disease [131,132]. It also demonstrates strong in vitro activity against the order Mucorales, particularly Lichtheimia, Rhizopus, and Rhizomucor spp [6,133,134]. The activity of isavuconazole against Mucorales appears to be species specific. The sensitivity of Rhizopus arrhizus to isavuconazole was similar to that of Rhizopus spp. but significantly greater than that of Mucor spp. and Mucor circinelloides [133–135]. A global multicenter study showed that isavuconazole is as effective as AmB for the treatment of mucormycosis and is well tolerated [136]. The use of isavuconazole for the treatment of pediatric mucormycosis is generally uncommon. However, isavuconazole combined with caspofungin and AmB has also been used successfully for disseminated mucormycosis in children with acute leukemia [137]. Isavuconazole, a salvage therapy, has also shown significant therapeutic efficacy in treating pediatric mucormycosis [138]. Isavuconazole demonstrated greater tolerance than AmB [136] and fewer adverse events [139]. Isavuconazole is currently recommended for salvage treatment of mucormycosis [3]. Notably, monitoring plasma drug concentrations is unnecessary for isavuconazole. In addition, isavuconazole for the prophylaxis of IFDs in patients with acute myeloid leukemia neutropenia demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy [132]. The possibility of prophylaxis for mucormycosis exists in clinical practice and needs to be further explored.

Echinocandins

Echinocandins are specific noncompetitive inhibitors targeting β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase (GS), an enzyme that synthesizes essential components of the fungal cell wall [140,141]. In Mucorales, the cell wall mainly contains β-(1,6)-D-glucans, leading to decreased activity of echinocandins against Mucorales in vitro [142,143]. In standard in vitro susceptibility tests, echinocandins showed no activity against Mucorales. However, the combination of caspofungin with amphotericin B, posaconazole, or itraconazole has synergistic effects in vitro [144]. Animal experiments also showed that ABLC combined with carpofungin, LAmB combined with micafengin or LAmB combined with anidulafengin can synergistically reduce the mortality of mice infected with R. oryzae compared with polyene monotherapy. This may be due to the inhibitory effect of echinocandins on the 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase of Rhizopus oryzae [145]. Polyene-caspofungin therapy also showed a greater treatment success rate and longer survival time than polyene monotherapy in patients with puncturally confirmed ROCM, especially in patients with cerebral involvement [146]. There are three possible mechanisms by which echinocandins improve the efficacy of polyene in the treatment of mucormycosis [147]: (1) enhancing the delivery of polyene to cell membranes through the destruction of β-glucan crosslinking of the cell wall; (2) altering fungal virulence by inhibiting mycelia growth or changing the cell wall ssscontent; and (3) enhancing the host response to fungi. Further study on the role of echinocandins in the treatment of mucormycosis is needed.

Combination therapy

The efficacy of combination therapy for mucormycosis remains uncertain due to limited data. In vitro combination studies have shown that most of the interactions between antifungal drugs are indifferent, and only echinocandins combined with azole or amphotericin B can achieve a certain synergistic effect. In animal models, the combination of antifungal agents does not always exhibit synergistic effects [148–150]. LAmB combined with TRIzole is the predominant combination therapy for mucormycosis in clinical practice. A meta-analysis revealed that the mortality of patients who received combination treatment with AmB plus azole (6.6%) was lower than that of patients who received monotherapy with AmB (31.5%) [151]. Patients with refractory mucormycosis also benefit from AmB formulations combined with posaconazole [152,153]. The combined administration of AmB formulations and fluconazole for mucormycosis treatment is particularly rare. Because there is currently insufficient evidence that combination therapy is superior to monotherapy, the guidelines [3] do not recommend combination therapy as first-line therapy. Combinations of antifungal and nonantifungal agents, including immune suppressors and fungal enzyme inhibitors, have also been explored in vitro and in animal models. Iron chelators can reduce free iron levels and have synergistic effects with AmB. Deferasirox is an iron chelator with antifungal activity. Deferritin monotherapy can significantly improve the survival rate of mucormycotic mice and reduce the tissue fungal burden. The efficacy of deferritin monotherapy is similar to that of AmB monotherapy. Moreover, the efficacy of AmB against Mucorales was improved by combination with deferasirox [154].

The immune suppressors sirolimus and cyclosporin A showed synergistic effects when combined with AmB. The Hos2 fungal histone deacetylase inhibitors MGCD290 and posaconazole had synergistic effects on 93% of the tested Mucorales isolates [155]. The combination of statins with azole had synergistic effects on only 30% of R. arrhizus strains [156]. Antiprotozoal miltefosine combined with posaconazole had synergistic effects on 50% of the isolates [157]. The majority of current data on combination therapy are derived from retrospective studies, individual cases, and in vitro experiments, and almost all of these studies have focused on R. arrhizus. Therefore, new animal experiments and prospective studies are urgently needed, and different species of Mucorales should be included in combination therapy exploration.

Adjunctive therapy

Immune exhaustion can be induced by a hyperinflammatory response, as observed in patients with COVID-19 and influenza [158]. Immune exhaustion is also associated with the overexpression of immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [159]. This immune state establishes a highly permissive environment for fungal coinfections [160]. Therefore, systemic antifungal therapy combined with immunomodulatory therapy may be more beneficial. In the antifungal immune response, IFN-γ and type I IFNs play crucial roles in antigen presentation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines [161]. Recombinant IFN-γ was used to treat mucorrhea patients, and the clinical symptoms improved rapidly [162,163]. A previous study showed that PD-1 and programmed death ligand-1 (PDL-1) significantly improved survival, reduced morbidity, and lowered the fungal burden in Rhizopus arrhizus-infected mice [164]. Animal experiments have shown that monoclonal anti-CotH3 antibodies protect immunosuppressed mice against mucormycosis by augmenting macrophage phagocytosis and preventing invasion [165]. Granulocyte (macrophage) colony-stimulating factors have also been proposed as adjuvant therapy [166]. Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy improves the function of neutrophils through increased oxygen pressure, promotes AmB activity by reversing acidosis, and increases the rate of wound healing by inhibiting fungal growth. HBO treatment is also effective as an adjunct to surgery and antifungal treatment for mucormycosis, especially in diabetic patients with sinusitis or cutaneous mucormycosis [167]. Given the limited evidence, adjuvant treatment strategies need to be evaluated individually, taking into account the patient’s immune status and balancing the benefits and potential harms.

New antifungal agents

The choice of antifungal agents for treating mucormycosis is very limited, and additional novel antimucromycotic drugs are needed. VT-1161 [168] is a novel inhibitor of the fungal CYP51 that has in vitro activity against Mucorales and can prolong the survival of mice infected with Rhizopus oryzae. APX001A is an antifungal agent targeting Gwt1 that has moderate in vitro activity and protects immunosuppressed mice from Rhizopus delemar infection. Hemofungin also inhibited Rhizopus growth in vitro [169].

Multidisciplinary approaches for treating mucormycosis

The clinical manifestations of mucormycosis are nonspecific, requiring clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion in populations at risk, early diagnosis and early effective treatment to save lives, which requires multidisciplinary team (MDT) management [170–173]. The guidelines [3] suggested that the involvement of radiology, infectious disease, and surgery is crucial in an MDT for mucormycosis treatment. Nevertheless, pathology and laboratory results are critical to the diagnosis of mucormycosis [8,95,174]. Otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and neurosurgery also play significant roles in the successful debridement of certain patients [173]. Critical care medicine has also provided comprehensive postoperative medical support for patients with severe illness [173]. Clinical pharmacists provide guidance on the safe administration of medications. Overall, an MDT is an important management model for early diagnosis, individualized treatment, and improved prognosis of mucormycosis patients.

Conclusion

Comprehensively, high-risk groups of mucormycosis are primarily immunocompromised patients. Amphotericin B remains the mainstay of treatment, although its nephrotoxicity limits its use, and surgical intervention plays a crucial role in controlling the infection. Due to the increased incidence of mucormycosis and poor prognosis, clinicians must be highly vigilant, and early diagnosis and early treatment are needed to reduce mortality. Although advances in molecular diagnostic technology have improved the detection rate of Mucor, new detection methods still need to be developed. Treatment mainly relies on surgery combined with antifungal drugs. However, therapeutic agents are limited, and new therapeutic agents and strategies are needed to improve therapeutic effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Decheng Jiang of West China Hospital, Sichuan University for his help with the preparation of figures in this paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the 1·3·5 project for Disciplines of Excellence-Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University [grant number 2021HXFH032].

Author contributions

Mei Liang: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-review&editing; Jian Xu: Resources, Writing-review&editing, Visualization; Yanan Luo: Resources, Writing-Review&Editing; Junyan Qu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-Review&Editing, Visualization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Disclaimers

This article represents the original work of the author team and has not been published in any other journal, nor is it being submitted simultaneously to any other publishing entity. Each author contributed to this research, reviewed the manuscript, and agreed to its submission.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.Maertens JA, et al. Invasive fungal infections. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M.. The EBMT handbook: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies. Cham (CH): Springer; 2019. p. 273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang N, Zhang L, Feng S.. Clinical features and treatment progress of invasive mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies. J Fungi (Basel). 2023;9(5):592. [published Online First: 20230519] doi: 10.3390/jof9050592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):e405–e21. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30312-3.[published Online First: 20191105] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz JE, Stratton CW, Persing DH, et al. Forty years of molecular diagnostics for infectious diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(10):e0244621. [published Online First: 20220719] doi: 10.1128/jcm.02446-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azhar A, Khan WH, Khan PA, et al. Mucormycosis and COVID-19 pandemic: clinical and diagnostic approach. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(4):466–479. [published Online First: 20220218] doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong W, Keighley C, Wolfe R, et al. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(1):26–34. [published Online First: 20180721] doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(5):634–653. [published Online First: 20050729] doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skiada A, Lass-Floerl C, Klimko N, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis. Med Mycol. 2018;56(suppl_1):93–101. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uppuluri P, Alqarihi A, & Ibrahim AS. Mucormycoses. In: Zaragoza Ó, Casadevall A. Encyclopedia of Mycology. Elsevier; 2021. Vol. 1, pp. 600–612. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.21013-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ.. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(2):236–301. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.236-301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özbek L, Topçu U, Manay M, et al. COVID-19-associated mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 958 cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023;29(6):722–731. [published Online First: 20230313] doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2023.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prakash H, Chakrabarti A.. Global epidemiology of mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2019;5(1):26. [published Online First: 20190321] doi: 10.3390/jof5010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel A, Kaur H, Xess I, et al. A multicenter observational study on the epidemiology, risk factors, management and outcomes of mucormycosis in India. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(7):944.e9-44–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rees JR, Pinner RW, Hajjeh RA, et al. The epidemiological features of invasive mycotic infections in the San Francisco Bay area, 1992-1993: results of population-based laboratory active surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(5):1138–1147. doi: 10.1093/clinids/27.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kontoyiannis DP, Yang H, Song J, et al. Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):730. [published Online First: 20161201] doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spellberg B, Edwards J, Jr., Ibrahim A.. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):556–569. doi: 10.1128/cmr.18.3.556-569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakash H, Chakrabarti A.. Epidemiology of mucormycosis in India. Microorganisms. 2021;9(3):523. [published Online First: 20210304] doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin E, Moua T, Limper AH.. Pulmonary mucormycosis: clinical features and outcomes. Infection. 2017;45(4):443–448. [published Online First: 20170220] doi: 10.1007/s15010-017-0991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motamedi M, Golmohammadi Z, Yazdanpanah S, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, therapeutic interventions and outcomes of mucormycosis in Shiraz: an 8-year retrospective case study with comparison between children and adults. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17174. [published Online First: 20221013] doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaezi A, Moazeni M, Rahimi MT, et al. Mucormycosis in Iran: a systematic review. Mycoses. 2016;59(7):402–415. [published Online First: 20160215] doi: 10.1111/myc.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebremariam T, Liu M, Luo G, et al. CotH3 mediates fungal invasion of host cells during mucormycosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):237–250. [published Online First: 20131220] doi: 10.1172/jci71349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Drogari-Apiranthitou M.. Epidemiology of mucormycosis in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 6:67–73. [published Online First: 20140306] doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambrosioni J, Bouchuiguir-Wafa K, Garbino J.. Emerging invasive zygomycosis in a tertiary care center: epidemiology and associated risk factors. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14 Suppl 3:e100-3–e103. [published Online First: 20100324] doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres-Narbona M, Guinea J, Martínez-Alarcón J, et al. Workload and clinical significance of the isolation of zygomycetes in a tertiary general hospital. Med Mycol. 2008;46(3):225–230. doi: 10.1080/13693780701796973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dantas KC, Mauad T, de André CDS, et al. A single-center, retrospective study of the incidence of invasive fungal infections during 85 years of autopsy service in Brazil. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3943. [published Online First: 20210217] doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83587-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skiada A, Pagano L, Groll A, et al. Zygomycosis in Europe: analysis of 230 cases accrued by the registry of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Working Group on Zygomycosis between 2005 and 2007. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(12):1859–1867. [published Online First: 20110701] doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puerta-Alcalde P, Monzó-Gallo P, Aguilar-Guisado M, et al. Breakthrough invasive fungal infection among patients with hematologic malignancies: a national, prospective, and multicenter study. J Infect. 2023;87(1):46–53. [published Online First: 20230516] doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2023.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54 Suppl 1: s 23–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudramurthy SM, Hoenigl M, Meis JF, et al. ECMM/ISHAM recommendations for clinical management of COVID-19 associated mucormycosis in low- and middle-income countries. Mycoses. 2021;64(9):1028–1037. [published Online First: 20210726] doi: 10.1111/myc.13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pushparaj K, Kuchi Bhotla H, Arumugam VA, et al. Mucormycosis (black fungus) ensuing COVID-19 and comorbidity meets – magnifying global pandemic grieve and catastrophe begins. Sci Total Environ. 2022;805:150355. [published Online First: 20210916] doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szebenyi C, Gu Y, Gebremariam T, et al. cotH genes are necessary for normal spore formation and virulence in Mucor lusitanicus. mBio. 2023;14(1):e0338622. [published Online First: 20230110] doi: 10.1128/mbio.03386-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alqarihi A, Gebremariam T, Gu Y, et al. GRP78 and integrins play different roles in host cell invasion during mucormycosis. mBio. 2020;11(3):e01087-20. [published Online First: 20200602] doi: 10.1128/mBio.01087-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghuman H, Shepherd-Roberts A, Watson S, et al. Mucor circinelloides induces platelet aggregation through integrin αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIA. Platelets. 2019;30(2):256–263. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2017.1420152 [published Online First: 20180103] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M, Spellberg B, Phan QT, et al. The endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1914–1924. [published Online First: 20100517] doi: 10.1172/jci42164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croston TL, Lemons AR, Beezhold DH, et al. MicroRNA regulation of host immune responses following fungal exposure. Front Immunol. 2018;9:170. [published Online First: 20180207] doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins TN, Gebremariam T, Swidergall M, et al. Inhibition of EGFR signaling protects from mucormycosis. mBio. 2018;9(4):e01384-18. [published Online First: 20180814] doi: 10.1128/mBio.01384-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride WJH. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, 7th edition. Sex Health. 2010;7(2):218–218. doi: 10.1071/SHv7n2_BR3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ibrahim AS. Host-iron assimilation: pathogenesis and novel therapies of mucormycosis. Mycoses. 2014;57 Suppl 3(0 3):13–17. [published Online First: 20140901] doi: 10.1111/myc.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Artis WM, Fountain JA, Delcher HK, et al. A mechanism of susceptibility to mucormycosis in diabetic ketoacidosis: transferrin and iron availability. Diabetes. 1982;31(12):1109–1114. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanford FA, Voigt K.. Iron assimilation during emerging infections caused by opportunistic fungi with emphasis on mucorales and the development of antifungal resistance. Genes (Basel). 2020;11(11):1296. [published Online First: 20201030] doi: 10.3390/genes11111296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwok EY, Severance S, Kosman DJ.. Evidence for iron channeling in the Fet3p-Ftr1p high-affinity iron uptake complex in the yeast plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2006;45(20):6317–6327. doi: 10.1021/bi052173c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibrahim AS, Gebremariam T, Lin L, et al. The high affinity iron permease is a key virulence factor required for Rhizopus oryzae pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77(3):587–604. [published Online First: 20100601] doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhadania S, Bhalodiya N, Sethi Y, et al. Hyperferritinemia and the extent of mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20569. [published Online First: 20211221] doi: 10.7759/cureus.20569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE, Jr., Fu Y, et al. Deferiprone iron chelation as a novel therapy for experimental mucormycosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(5):1070–1073. [published Online First: 20060823] doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boelaert JR, Fenves AZ, Coburn JW.. Deferoxamine therapy and mucormycosis in dialysis patients: report of an international registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;18(6):660–667. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou R, To KK, Wong YC, et al. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection impairs dendritic cell and T-cell responses. Immunity. 2020;53(4):864–877.e5. [published Online First: 20200804] doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas C, Wong P, Klein J, et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2020;584(7821):463–469. [published Online First: 20200727] doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao YD, Ding M, Dong X, et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: a review. Allergy. 2021;76(2):428–455. [published Online First: 20201204] doi: 10.1111/all.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gürsoy B, Sürmeli CD, Alkan M, et al. Cytokine storm in severe COVID-19 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2021;93(9):5474–5480. [published Online First: 20210515] doi: 10.1002/jmv.27068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin K, Peluso MJ, Luo X, et al. Long COVID manifests with T-cell dysregulation, inflammation and an uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2024;25(2):218–225. [published Online First: 20240111] doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. Cell. 2021;184(1):149–168.e17. [published Online First: 20201119] doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schulte-Schrepping J, Reusch N, Paclik D, et al. Severe COVID-19 is marked by a dysregulated myeloid cell compartment. Cell. 2020;182(6):1419–1440.e23. [published Online First: 20200805] doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dandu H, Kumar M, Malhotra HS, et al. T-cell dysfunction as a potential contributing factor in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis. Mycoses. 2023;66(3):202–210. [published Online First: 20221104] doi: 10.1111/myc.13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta I, Baranwal P, Singh G, et al. Mucormycosis, past and present: a comprehensive review. Future Microbiol. 2023;18(3):217–234. [published Online First: 20230327] doi: 10.2217/fmb-2022-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xhaard A, Lanternier F, Porcher R, et al. Mucormycosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a French Multicenter Cohort Study (2003-2008). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(10):E396–400. [published Online First: 20120604] doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muthu V, Agarwal R, Patel A, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of COVID-19-associated pulmonary mucormycosis: Delphi consensus statement from the Fungal Infection Study Forum and Academy of Pulmonary Sciences, India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):e240–e53. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00124-4.[published Online First: 20220404] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Carvalho A, et al. The emergence of COVID-19 associated mucormycosis: a review of cases from 18 countries. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(7):e543–e52. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skiada A, Drogari-Apiranthitou M, Pavleas I, et al. Global cutaneous mucormycosis: a systematic review. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8(2):194. [published Online First: 20220216] doi: 10.3390/jof8020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zaoutis TE, Roilides E, Chiou CC, et al. Zygomycosis in children: a systematic review and analysis of reported cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(8):723–727. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318062115c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaur H, Ghosh A, Rudramurthy SM, et al. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis in apparently immunocompetent hosts – a review. Mycoses. 2018;61(12):898–908. [published Online First: 20180620] doi: 10.1111/myc.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei LW, Zhu PQ, Chen XQ, et al. Mucormycosis in Mainland China: a systematic review of case reports. Mycopathologia. 2022;187(1):1–14. [published Online First: 20211202] doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00607-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khullar T, Kumar J, Sindhu D, et al. CT imaging features in acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis – recalling the oblivion in the COVID era. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2022;51(5):798–805. [published Online First: 20220207] doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2022.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu J, Liu X, Lv X.. Pulmonary mucormycosis as the leading clinical type of mucormycosis in Western China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:770551. [published Online First: 20211122] doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.770551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garg M, Prabhakar N, Muthu V, et al. CT findings of COVID-19-associated pulmonary mucormycosis: a case series and literature review. Radiology. 2022;302(1):214–217. [published Online First: 20210831] doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021211583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sweed AH, Mobashir M, Elnashar I, et al. MRI as a road map for surgical intervention of acute invasive fungal sinusitis in Covid-19 era. Clin Otolaryngol. 2022;47(2):388–392. [published Online First: 20220111] doi: 10.1111/coa.13907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sreshta K, Dave TV, Varma DR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(7):1915–1927. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1439_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.He R, Hu C, Niu R.. Analysis of the clinical features of tracheobronchial fungal infections with tumor-like lesions. Respiration. 2019;98(2):157–164. [published Online First: 20190508] doi: 10.1159/000496979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Damaraju V, Agarwal R, Dhooria S, et al. Isolated tracheobronchial mucormycosis: report of a case and systematic review of literature. Mycoses. 2023;66(1):5–12. [published Online First: 20220901] doi: 10.1111/myc.13519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanz-Bueno J, Castellanos-González M, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Disseminated zygomycosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;140(11):e21. [published Online First: 20130326] doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horiguchi T, Tsukamoto T, Toyama Y, et al. Fatal disseminated mucormycosis associated with COVID-19. Respirol Case Rep. 2022;10(3):e0912. [published Online First: 20220213] doi: 10.1002/rcr2.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(4):1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, et al. Revision and update of the Consensus Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Medical Mycology Society of Chinese Medicine and Education Association; Chinese Mucormycosis Expert Consensus Group. Expert consensus on diagnosis and management of mucormycosis in China . Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2023;62(6):597–605. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20220729-00557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lackner N, Posch W, Lass-Flörl C.. Microbiological and molecular diagnosis of mucormycosis: from old to new. Microorganisms. 2021;9(7):1518. [published Online First: 20210716] doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shanmugasundaram S, Ramasamy V, Shiguru S.. Role of histopathology in severity assessments of post-COVID-19 rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis – a case–control study. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2023;67:152183. [published Online First: 20230727] doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2023.152183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Frater JL, Hall GS, Procop GW.. Histologic features of zygomycosis: emphasis on perineural invasion and fungal morphology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125(3):375–378. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0375-hfoz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 3:5–26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dannaoui E. Antifungal resistance in mucorales. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(5):617–621. [published Online First: 20170809] doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salas V, Pastor FJ, Calvo E, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of posaconazole and amphotericin B in a murine invasive infection by Mucor circinelloides: poor efficacy of posaconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2246–2250. [published Online First: 20120130] doi: 10.1128/aac.05956-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B.. Identification of molds by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(2):369–379. [published Online First: 20161102] doi: 10.1128/jcm.01640-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Skiada A, Lanternier F, Groll AH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies: guidelines from the 3rd European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL 3). Hematologica. 2013;98(4):492–504. doi: 10.3324/hematol.2012.065110.[published Online First: 20120914] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang W, Yao Y, Li X, et al. Clinical impact of metagenomic next-generation sequencing of peripheral blood for the diagnosis of invasive mucormycosis: a single-center retrospective study. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12(1):e0355323. [published Online First: 20231214] doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03553-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burnham-Marusich AR, Hubbard B, Kvam AJ, et al. Conservation of Mannan synthesis in fungi of the zygomycota and ascomycota reveals a broad diagnostic target. mSphere. 2018;3(3):e00094-18. [published Online First: 20180502] doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00094-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koo S, Thomas HR, Daniels SD, et al. A breath fungal secondary metabolite signature to diagnose invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1733–1740. [published Online First: 20141022] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chakravarty S, Nagarkar NM, Mehta R, et al. Skull base involvement in covid associated rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis: a comprehensive analysis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;75(3):1–13. [published Online First: 20230408] doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-03717-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang L, Fu J, Cai G, et al. Rapid and visual RPA-Cas12a fluorescence assay for accurate detection of dermatophytes in cats and dogs. Biosensors (Basel). 2022;12(8):636. [published Online First: 20220813] doi: 10.3390/bios12080636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tissot F, Agrawal S, Pagano L, et al. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Hematologica. 2017;102(3):433–444. doi: 10.3324/hematol.2016.152900.[published Online First: 20161223] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jiang RS, Hsu CY.. Endoscopic sinus surgery for rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13(2):105–109. doi: 10.2500/105065899782106751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang Y, Chen X, Wang J, et al. Oral posaconazole and bronchoscopy as a treatment for pulmonary mucormycosis in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(6):e24630. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000024630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.He R, Hu C, Tang Y, et al. Report of 12 cases with tracheobronchial mucormycosis and a review. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(4):1651–1660. [published Online First: 20180219] doi: 10.1111/crj.12724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vironneau P, Kania R, Morizot G, et al. Local control of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis dramatically impacts survival. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(5):O336–9. [published Online First: 20131106] doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Multani A, Reveron-Thornton R, Garvert DW, et al. Cut it out! Thoracic surgeon’s approach to pulmonary mucormycosis and the role of surgical resection in survival. Mycoses. 2019;62(10):893–907. [published Online First: 20190806] doi: 10.1111/myc.12954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Clark FL, Batra RS, Gladstone HB.. Mohs micrographic surgery as an alternative treatment method for cutaneous mucormycosis. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(8):882–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tang X, Guo P, Wong H, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure and skin grafting combined with amphotericin B for successful treatment of an immunocompromised patient with cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis: a case report and literature review. Mycopathologia. 2021;186(3):449–459. [published Online First: 20210615] doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chegini Z, Didehdar M, Khoshbayan A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of cerebral mucormycosis in diabetic patients: a systematic review of case reports and case series. Mycoses. 2020;63(12):1264–1282. [published Online First: 20201003] doi: 10.1111/myc.13187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bekersky I, Fielding RM, Dressler DE, et al. Pharmacokinetics, excretion, and mass balance of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and amphotericin B deoxycholate in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(3):828–833. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.3.828-833.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walsh TJ, Goodman JL, Pappas P, et al. Safety, tolerance, and pharmacokinetics of high-dose liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) in patients infected with Aspergillus species and other filamentous fungi: maximum tolerated dose study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(12):3487–3496. doi: 10.1128/aac.45.12.3487-3496.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lanternier F, Poiree S, Elie C, et al. Prospective pilot study of high-dose (10 mg/kg/day) liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB) for the initial treatment of mucormycosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(11):3116–3123. [published Online First: 20150827] doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jung S, Kim MS.. Fungal endophthalmitis in a case of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis treated with 0.02% intravitreal liposomal amphotericin B injection: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2023;37(5):434–436. [published Online First: 20230912] doi: 10.3341/kjo.2023.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smith LD, Ahmad M, Ashraf DC, et al. Cutaneous mucormycosis of the eyelid treated with subcutaneous liposomal amphotericin B injections. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;40(2):e42–e45. [published Online First: 202403/04] doi: 10.1097/iop.0000000000002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Boulware DR, Atukunda M, Kagimu E, et al. Oral lipid nanocrystal amphotericin B for cryptococcal meningitis: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(12):1659–1667. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Torres HA, Hachem RY, Chemaly RF, et al. Posaconazole: a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(12):775–785. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(05)70297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Antifungal Agents . LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen L, Krekels EHJ, Verweij PE, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of posaconazole. Drugs. 2020;80(7):671–695. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McKeage K. Posaconazole: a review of the gastro-resistant tablet and intravenous solution in invasive fungal infections. Drugs. 2015;75(4):397–406. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Keating GM. Posaconazole. Drugs. 2005;65(11):1553–1567. discussion 689. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lehrnbecher T, Attarbaschi A, Duerken M, et al. Posaconazole salvage treatment in pediatric patients: a multicenter survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(8):1043–1045. [published Online First: 20100522] doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tobón AM, Arango M, Fernández D, et al. Mucormycosis (zygomycosis) in a heart-kidney transplant recipient: recovery after posaconazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(11):1488–1491. [published Online First: 20030516] doi: 10.1086/375075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sipsas NV, Gamaletsou MN, Anastasopoulou A, et al. Therapy of mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4(3):90. [published Online First: 20180731] doi: 10.3390/jof4030090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang T, Bai J, Huang M, et al. Posaconazole and fluconazole prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54(6):1139–1146. [published Online First: 20200801] doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lewis JS, 2nd, Wiederhold NP, Hakki M, et al. New perspectives on antimicrobial agents: isavuconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(9):e0017722. [published Online First: 20220815] doi: 10.1128/aac.00177-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lamoth F, Mercier T, André P, et al. Isavuconazole brain penetration in cerebral aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(6):1751–1753. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Davis MR, Chang S, Gaynor P, et al. Isavuconazole for treatment of refractory coccidioidal meningitis with concomitant cerebrospinal fluid and plasma therapeutic drug monitoring. Med Mycol. 2021;59(9):939–942. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myab035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Badali H, Cañete-Gibas C, McCarthy D, et al. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibilities of mucoralean fungi in clinical samples from the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(9):e0123021. [published Online First: 20210818] doi: 10.1128/jcm.01230-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Alvarez E, Sutton DA, Cano J, et al. Spectrum of zygomycete species identified in clinically significant specimens in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1650–1656. [published Online First: 20090422] doi: 10.1128/jcm.00036-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Arendrup MC, Jensen RH, Meletiadis J.. In vitro activity of isavuconazole and comparators against clinical isolates of the Mucorales order. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(12):7735–7742. [published Online First: 20151005] doi: 10.1128/aac.01919-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case–control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):828–837. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)00071-2.[published Online First: 20160309] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pomorska A, Malecka A, Jaworski R, et al. Isavuconazole in a successful combination treatment of disseminated mucormycosis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and generalized hemochromatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):81–88. [published Online First: 20180723] doi: 10.1007/s11046-018-0287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L, Bilavsky E, Levy I, et al. Isavuconazole as successful salvage therapy for mucormycosis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(8):718–724. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000002671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA, et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mold disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomized-controlled, noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):760–769. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01159-9.[published Online First: 20151210] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Douglas CM, D’Ippolito JA, Shei GJ, et al. Identification of the FKS1 gene of Candida albicans as the essential target of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(11):2471–2479. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Warrilow AG, Hull CM, Parker JE, et al. The clinical candidate VT-1161 is a highly potent inhibitor of Candida albicans CYP51 but fails to bind the human enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7121–7127. [published Online First: 20140915] doi: 10.1128/aac.03707-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Szymański M, Chmielewska S, Czyżewska U, et al. Echinocandins – structure, mechanism of action and use in antifungal therapy. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37(1):876–894. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2022.2050224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]