ABSTRACT

HepB-CpG is a licensed adjuvanted two-dose hepatitis B vaccine for adults, with limited data on exposure during pregnancy. We assessed the risk of pregnancy outcomes among individuals who received HepB-CpG or the 3-dose HepB-alum vaccine ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy at Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC). The pregnancy cohort included KPSC members aged ≥18 y who received ≥1 dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-CpG or HepB-alum) at KPSC outpatient family or internal medicine departments from August 2018 to November 2020. We followed these individuals through electronic health records from the vaccination date until the end of pregnancy, KPSC health plan disenrollment, or death, whichever came first. Among 81 and 125 eligible individuals who received HepB-CpG and HepB-alum, respectively, live births occurred in 84% and 74%, spontaneous abortion occurred in 7% and 17% (adjusted relative risk [aRR] 0.40, 95% CI: 0.16–1.00), and preterm birth occurred in 15% and 14% of liveborn infants (aRR 0.97, 95% CI 0.47–1.99). No major birth defects were identified through 6 months of age. The study found no evidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes for recipients of HepB-CpG in comparison to HepB-alum.

KEYWORDS: Hepatitis B vaccine, safety, HepB-CpG, pregnancy, birth defects

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes a substantial burden of disease in the United States (US), despite the availability of effective vaccines. In 2018, there were an estimated 21,600 new acute infections, but this number fell to 13,300 in 2021, potentially due to disruptions in HBV testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 An estimated 1.59 (range 1.25–2.49) million people in the US have chronic hepatitis B, although many individuals are unaware of the infection.2 Among pregnant people, the estimated prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection is 0.7–0.9%.3 HBV during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm delivery and potential for perinatal transmission in the absence of maternal antiviral treatment and infant postexposure prophylaxis.4,5 Of infants infected with HBV at birth, 25% will eventually die of HBV-associated cirrhosis or liver cancer.6

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends hepatitis B vaccination for all adults aged <60 y, including pregnant individuals.7 HepB-CpG (Heplisav-B) is an adult hepatitis B vaccine composed of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and a toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist adjuvant, CpG 1018. HepB-CpG was licensed in 2017 and requires two doses (at 0 and 1 month). In comparison, HepB-alum vaccine (Engerix-B) is composed of HBsAg with an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant and requires 3 doses (at 0, 1, and 6 months).8 In clinical trials, HepB-CpG elicited earlier and higher seroprotection than HepB-alum.9,10 HepB-CpG has also been associated with higher series completion compared to HepB-alum.11

HepB-CpG is not contraindicated during pregnancy; however, in pivotal clinical trials, only 36 individuals exposed to HepB-CpG and 17 exposed to HepB-alum prior to pregnancy had data on pregnancy outcomes, with no differences observed between groups.12 Since data on HepB-CpG exposure during pregnancy are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy, ACIP recommends that pregnant individuals needing hepatitis B vaccination receive a vaccine from a different manufacturer (e.g., HepB-alum, Recombivax HB, or Twinrix).7,13 Nonetheless, inadvertent exposure to HepB-CpG during pregnancy may occur, for example, if an individual is vaccinated before becoming aware of the pregnancy. Although safety during pregnancy has been examined for hepatitis B vaccines other than HepB-GpG without finding significant associations with adverse pregnancy and infant outcomes,14 similar post-licensure safety studies during pregnancy have not been conducted for HepB-CpG.

Recognizing the need for data on the safety of HepB-CpG vaccination during pregnancy, we conducted a retrospective cohort study nested within a large pragmatic vaccine study at Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC). This pragmatic study assessed safety using real-world data under routine clinical practice, instead of under ideal conditions as part of a traditional clinical trial. We compared pregnancy outcomes following receipt of HepB-CpG vs. HepB-alum, the hepatitis B vaccine product that had routinely been used at KPSC.

Methods

KPSC is an integrated health care system with >4.8 million sociodemographically diverse members. Comprehensive electronic health records (EHR) cover all details of care received at KPSC facilities, including diagnoses, vaccinations, procedures, laboratory tests and results, and medications ordered and dispensed. Care received outside of KPSC is integrated into the EHR. The study was approved by the KPSC IRB (#11601), which waived the requirement for informed consent due to minimal risk to participants.

We previously conducted a large pragmatic, prospective cohort study to examine the association of HepB-CpG with acute myocardial infarction15 and other safety outcomes;16 this study used a nonrandomized cluster design to distribute vaccines as part of routine care, such that HepB-CpG became the only hepatitis B vaccine available in 7 of the 15 KPSC medical centers in family and internal medicine departments, while the other eight medical centers continued to use HepB-alum vaccine. The cohort included KPSC members aged ≥18 y who received ≥1 dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-CpG or HepB-alum) at KPSC outpatient family or internal medicine departments from August 2018 to November 2020 (N = 69,625). Further details of the study design are described in our prior publications.11,15–17

In the nested study described in this manuscript, we included a subset of the HepB-CpG and HepB-alum cohorts that received ≥1 dose of HepB-CpG or HepB-alum ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy. Pregnancy start date (estimated date of conception) was determined by the estimated date of delivery (EDD) minus 38 weeks. If EDD was not available, the conception date was estimated by last menstrual period plus 2 weeks. For non-live birth outcomes where pregnancy dates were not readily available in automated data, chart review was conducted to confirm pregnancy start and end dates. We followed these individuals through the EHR from the vaccination date until the end of pregnancy, KPSC health plan disenrollment, or death, whichever came first.

Pregnancy outcomes included spontaneous abortion (involuntary pregnancy loss at <20 weeks of gestation), induced abortion, stillbirth (fetal death at ≥20 weeks of gestation), preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks), low birth weight (<2500 g at birth), and small for gestational age (birth weight below 10th percentile for gestational age and gender).18 Pregnancy delivery outcomes (live birth, spontaneous abortion, induced abortion, stillbirth) were extracted from the pregnancy episode flowsheet from the EHR. If the pregnancy outcome in the pregnancy episode flowsheet was missing (e.g. patient delivered outside of a KPSC hospital), diagnosis codes for live birth (ICD-10: Z37.0, Z37.2, and Z37.5) from the inpatient and emergency department settings were used to capture live birth outcomes. Chart review was conducted for all occurrences of the following outcomes: spontaneous abortion, induced abortion, stillbirth, and unknown pregnancy outcomes. As automated EHR data for gestational age (used to derive preterm birth and small for gestational age outcomes) and low birth weight were available for births at KPSC hospitals, chart review for these outcomes was only conducted for births occurring outside of KPSC.

Among KPSC liveborn infants of individuals included in the study, we assessed major birth defects using the National Birth Defects Prevention Network categorization (central nervous system, eye, ear, cardiovascular, orofacial, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, and chromosomal) with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes from birth through 6 months of age.19

We described characteristics of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum recipients, including age group, race/ethnicity, neighborhood median household income, timing of hepatitis B vaccination prior to or during pregnancy, pre-pregnancy body mass index, diabetes in the year prior to conception, and trimester of starting prenatal care; additional characteristics included Medicaid enrollment, duration of KPSC membership prior to conception, time from conception to vaccination, comorbidities in the year prior to conception (gestational diabetes, hypertension, substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, mental health disorder), smoking during current pregnancy, Charlson comorbidity index and individual Charlson comorbidities20 in the year prior to conception, year of conception (2018, 2019, 2020), single/multiple gestation, healthcare utilization (any inpatient visit, any emergency department visit, and number of outpatient visits in the year prior to conception), number of prior pregnancies, number of prior live births, number of prior pregnancies not ending in live births, complications of current pregnancy (e.g., gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, kidney disease, autoimmune disease, COVID-19 disease), other vaccinations between conception and hepatitis B vaccination, other vaccinations between hepatitis B vaccination and end of pregnancy, and other concomitant vaccinations on hepatitis B vaccine index date. We also describe the characteristics of infants including singleton/multiple gestation, infant sex, gestational age at birth (weeks), birth weight (g), birth length (cm), head circumference (cm), and birth location.

We estimated the incidence proportions of outcomes in the HepB-CpG and HepB-alum groups, defined as the number of events divided by the eligible population for the outcome. We compared the event rate between groups using robust Poisson regression, adjusting for potential confounders (variables identified a priori [maternal age] or based on p-value ≤.05) when there were sufficient events to provide at least 80% power to detect a relative risk (RR) of 5.

Results

During the study period, 81 and 125 eligible individuals received ≥1 dose of HepB-CpG or HepB-alum, respectively, ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy, the majority of whom received hepatitis B vaccination ≤28 d prior to conception or during the first trimester of pregnancy (87.6% of HepB-CpG recipients and 84.0% of HepB-alum recipients). Of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum recipients, respectively, the mean age was 31.4 and 30.1 y, and Hispanic individuals comprised 60.5% and 56.8% (Table 1). The distribution of median neighborhood income differed between groups. More HepB-CpG vs. HepB-alum recipients had a history of diabetes (38.3% vs. 25.6%, p-value 0.05), were overweight or obese (72.8% vs. 64.8%, p-value <.01), and started prenatal care during the first trimester (59.3% vs. 40.0%, p-value 0.01). Other characteristics were similar between groups (Appendix 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of adult recipients of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum during the 28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy from August 2018 to November 2020.

| HepB-CpG Recipients | HepB-alum Recipients | Total | ||

| |

N = 81 n (%) |

N = 125 n (%) |

N = 206 n (%) |

p-value |

| Age (years) at vaccination | .09 | |||

| 18-25 | 15 (18.5) | 38 (30.4) | 53 (25.7) | |

| 26-35 | 40 (49.4) | 60 (48.0) | 100 (48.5) | |

| >35 | 26 (32.1) | 27 (21.6) | 53 (25.7) | |

| Mean±sd | 31.41 ± 6.40 | 30.08 ± 6.33 | 30.60 ± 6.37 | .12 |

| Race/Ethnicity | .75 | |||

| Hispanic | 49 (60.5) | 71 (56.8) | 120 (58.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic, Asian | 8 (9.9) | 10 (8.0) | 18 (8.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 9 (11.1) | 11 (8.8) | 20 (9.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic, White | 11 (13.6) | 25 (20.0) | 36 (17.5) | |

| None of the above/Unknown | 4 (4.9) | 8 (6.4) | 12 (5.8) | |

| Neighborhood median household income | .05 | |||

| <$40,000 | 10 (12.3) | 10 (8.0) | 20 (9.7) | |

| $40,000 -59,999 | 17 (21.0) | 39 (31.2) | 56 (27.2) | |

| $60,000 -79,999 | 24 (29.6) | 18 (14.4) | 42 (20.4) | |

| $80,000 -99,999 | 7 (8.6) | 20 (16.0) | 27 (13.1) | |

| $100,000+ | 8 (9.9) | 10 (8.0) | 18 (8.7) | |

| Missing | 15 (18.5) | 28 (22.4) | 43 (20.9) | |

| Timing of hepatitis B vaccination prior to or during pregnancy | .04 | |||

| ≤28 d prior to conception | 47 (58.0) | 49 (39.2) | 96 (46.6) | |

| First trimester | 24 (29.6) | 56 (44.8) | 80 (38.8) | |

| Second trimester | 8 (9.9) | 12 (9.6) | 20 (9.7) | |

| Third trimester | 2 (2.5) | 8 (6.4) | 10 (4.9) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI* | <.01 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Normal or healthy weight (18.5-24.9) | 17 (21.0) | 44 (35.2) | 61 (29.6) | |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 17 (21.0) | 33 (26.4) | 50 (24.3) | |

| Obese, class 1 (30.0-34.9) | 18 (22.2) | 25 (20.0) | 43 (20.9) | |

| Obese, class 2-3 (≥35.0) | 24 (29.6) | 23 (18.4) | 47 (22.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| History of diabetes in the year prior to conception | 31 (38.3) | 32 (25.6) | 63 (30.6) | .05 |

| Start of prenatal care | .01 | |||

| First trimester | 48 (59.3) | 50 (40.0) | 98 (47.6) | |

| Second trimester | 5 (6.2) | 6 (4.8) | 11 (5.3) | |

| Missing first prenatal care date | 28 (34.6) | 69 (55.2) | 97 (47.1) |

Abbreviations: sd, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

*Most recent BMI (kg/m2) from 2 y prior to conception date to conception date.

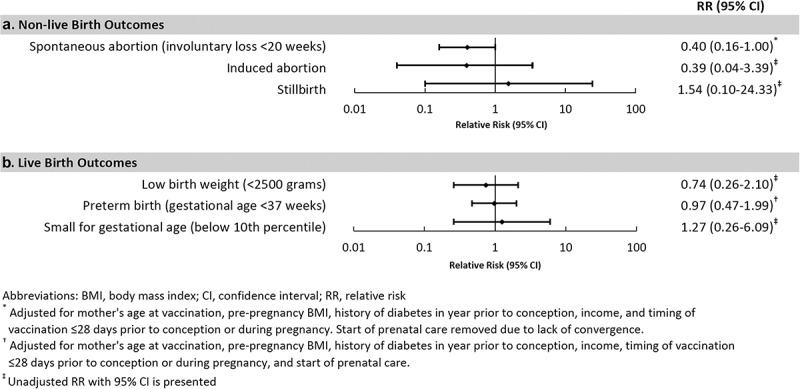

Live births occurred in 68 (84.0%) pregnancies among HepB-CpG recipients and 93 (74.4%) pregnancies among HepB-alum recipients. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 6 (7.4%) and 21 (16.8%) of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum recipients, respectively (adjusted RR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.16–1.00) (Figure 1, Table 2). There were insufficient events of induced abortion (one among HepB-CpG recipients and four among HepB-alum recipients) and stillbirth (one in each group) to assess the adjusted relative risk of these outcomes between groups.

Figure 1.

Relative risks of pregnancy outcomes comparing recipients of HepB-CpG with recipients of HepB-alum.

Table 2.

Event rates and relative risk for pregnancy outcomes among recipients of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum.

| HepB-CpG |

HepB-alum |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pregnancies/infants included | Number of events n (%) | Event rate (95% CI) | Number of pregnancies/infants included | Number of events n (%) |

Event rate (95% CI) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Adjusted RR (95% CI)* |

|

| Non-live birth outcomes | ||||||||

| Spontaneous abortion (involuntary loss <20 weeks) | 81 | 6 (7.4) | 0.07 (0.03-0.16) | 125 | 21 (16.8) | 0.17 (0.11-0.26) | 0.44 (0.19-1.05) | 0.40 (0.16,1.00)† |

| Induced abortion | 81 | 1 (1.2) | 0.01 (0.00-0.09) | 125 | 4 (3.2) | 0.03 (0.01-0.09) | 0.39 (0.04-3.39) | N/A |

| Stillbirth | 81 | 1 (1.2) | 0.01 (0.00-0.09) | 125 | 1 (0.8) | 0.01 (0.00-0.06) | 1.54 (0.10-24.33) | N/A |

| Live birth | ||||||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 grams) | 67 | 5 (7.5) | 0.07 (0.03-0.18) | 89 | 9 (10.1) | 0.10 (0.05-0.19) | 0.74 (0.26-2.10) | N/A |

| Preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks) | 68 | 10 (14.7) | 0.15 (0.08-0.27) | 94 | 13 (13.8) | 0.14 (0.08-0.24) | 1.06 (0.50-2.28) | 0.97 (0.47-1.99)‡ |

| Small for gestational age (below 10th percentile) | 67 | 3 (4.5) | 0.04 (0.01-0.14) | 85 | 3 (3.5) | 0.04 (0.01-0.11) | 1.27 (0.26-6.09) | N/A |

| Major birth defects among infants born in KPSC | ||||||||

| Central nervous system defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Eye defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ear defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cardiovascular defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Orofacial defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Gastrointestinal defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Genitourinary defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Musculoskeletal defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chromosomal defects | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Any major birth defect listed above | 66 | 0 | N/A | 67 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; KPSC, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

*Per protocol, adjusted robust Poisson regression models were used to compare event rates when there were sufficient events to provide at least 80% power to detect a relative risk of 5.

†Adjusted for mother’s age at vaccination, pre-pregnancy body mass index, history of diabetes in the year prior to conception, income, and timing of vaccination ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy. Start of prenatal care removed due to lack of convergence.

‡Adjusted for mother’s age at vaccination, pre-pregnancy body mass index, history of diabetes in the year prior to conception, income, timing of vaccination ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy and start of prenatal care.

Characteristics of live-born infants were also similar between HepB-CpG (n = 68) and HepB-alum (n = 95) groups (Appendix 2). All live-born infants were singletons, except for 4 (4.2%) infants in the HepB-alum group who were twins. Approximately 52% were female, and the median (IQR) gestational age at birth was 39 (37–39) weeks. Median (IQR) birth weight was 3325 (2990–3635) grams, length was 50 (48–52) cm, and head circumference was 34 (33–35) cm. More infants in the HepB-alum group than the HepB-CpG group were born outside of a KPSC hospital.

Preterm birth occurred among 10 (14.7%) infants in the HepB-CpG group and 13 (13.8%) in the HepB-alum group (adjusted RR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.47–1.99) (Figure 1, Table 2). Low birth weight occurred among five (7.5%) infants in the HepB-CpG group and nine (10.1%) in the HepB-alum group, and small for gestational age occurred among three (4.5%) infants in the HepB-CpG group and three (3.5%) in the HepB-alum group, respectively; there were insufficient events of these outcomes to assess the adjusted RR between groups. No major birth defects were identified through 6 months of age among infants born at KPSC (n = 66 for HepB-CpG and n = 67 for HepB-alum groups).

Discussion

In this observational study, nested within a large hepatitis B vaccine safety study, individuals exposed to HepB-CpG or HepB-alum just prior to conception or during pregnancy had similar rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Characteristics of live-born infants were similar between vaccine groups, and no major birth defects were identified through 6 months of age. The study included a real-world population of pregnant individuals who received hepatitis B vaccines, were racially and ethnically diverse, and had comorbidities. Given the dearth of existing data on HepB-CpG safety during pregnancy, our study offers an important contribution to the literature on pregnancy and infant outcomes among individuals exposed to HepB-CpG in the ≤28 d prior to conception or during pregnancy.

Hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all adults aged <60 y7 and is a critical strategy to reduce adverse maternal and infant outcomes associated with hepatitis B infection during pregnancy.4,21 As many healthy adults have infrequent preventive care visits or other health care encounters in which vaccinations may be offered, prenatal care visits can provide an opportunity to offer hepatitis B vaccination.22 A two-dose hepatitis B vaccine series compared to a 3-dose series could be advantageous to ensure series completion and protection against hepatitis B prior to delivery while individuals are engaged in care.11

Our study had several potential limitations. First, the sample size of eligible individuals inadvertently exposed to HepB-CpG was relatively small, as hepatitis B vaccines other than HepB-CpG were recommended for use during pregnancy. HepB-CpG exposures during pregnancy may have occurred prior to people becoming aware of pregnancy or for other reasons inconsistent with ACIP recommendations. Thus, our study had limited power to detect rare events; only spontaneous abortion and preterm birth occurred frequently enough for adjusted analyses. Second, the prevalence of diabetes was higher in our cohort than the general population, potentially because at the time of the study, KPSC had an EHR alert to offer hepatitis B vaccine to individuals with diabetes.23 Among pregnant vaccinated individuals, diabetes may have contributed to higher rates of stillbirth, preterm birth, and low birth weight that were observed in our study compared to vital statistics data.24,25 Rates of diabetes were somewhat higher in recipients of HepB-CpG (38.3%) than HepB-alum (25.6%), which would likely bias the unadjusted results toward higher rates of adverse outcomes in HepB-CpG recipients. Third, there is potential for misclassification of exposure and outcomes; however, these are unlikely, as HepB-CpG and HepB-alum were allocated to different medical center clusters, and vaccine doses were confirmed by the research team. We also used chart review to confirm the timing of exposure during pregnancy for non-live birth outcomes and to confirm certain pregnancy outcomes.

Nonetheless, this study is the first to document pregnancy outcomes following HepB-CpG vaccination in a real-world setting. These data are important given limited prior data on HepB-CpG exposure during pregnancy, and the potential role for HepB-CpG as a 2-dose vaccine to increase hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adults. Our study did not identify an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for recipients of HepB-CpG vs. HepB-alum, but ongoing surveillance of pregnancy outcomes following HepB-CpG vaccination is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Robert Janssen, MD, and Ouzama Henry, MD, MSc, who were employed at Dynavax Technologies Corporation during the study, and Ashley McDaniel, MA, who was employed by KPSC and provided research support.

Biography

Dr. Katia J Bruxvoort is an infectious disease epidemiologist with broad interests in infectious disease prevention. Her research focuses on vaccines, malaria, and HIV prevention, spanning international and U.S. health system and community settings, and incorporating a range of epidemiologic methods for observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Dr. Bruxvoort contributes to large observational studies to evaluate vaccine safety and effectiveness, including for COVID-19, hepatitis B, influenza, pneumococcal, meningococcal, and zoster vaccines. She also leads research in the U.S. Deep South and international settings on community-based HIV prevention strategies, implementation of malaria vaccines, and reducing disparities in vaccine uptake.

Appendix. 1. Additional characteristics of adult recipients of HepB-CpG and HepB-alum during the 1 d prior to conception or during pregnancy from August 2018 to November 2020

| HepB-CpG recipients | HepB-alum recipients | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

N = 81 n (%) |

N = 125 n (%) |

N = 206 n (%) |

|

| Medicaid enrollment, ever from conception to vaccination * | 9 (11.1) | 19 (15.2) | 27 (13.1) | .40 |

| Duration of membership prior to conception | .37 | |||

| None (enrolled after conception) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (1.6) | 4 (1.9) | |

| <1 month | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| 1 - <6 months | 11 (13.6) | 13 (10.4) | 24 (11.7) | |

| 6 months - <1 year | 5 (6.2) | 16 (12.8) | 21 (10.2) | |

| ≥1 year | 62 (76.5) | 94 (75.2) | 156 (75.7) | |

| Duration of membership from conception to vaccination | .14 | |||

| N/A (vaccination prior to conception) | 45 (55.6) | 49 (39.2) | 94 (45.6) | |

| <1 month | 18 (22.2) | 41 (32.8) | 59 (28.6) | |

| 1 - <4 months | 11 (13.6) | 20 (16.0) | 31 (15.0) | |

| ≥4 months | 7 (8.6) | 15 (12.0) | 22 (10.7) | |

| History of gestational diabetes in year prior to conception | 6 (7.4) | 7 (5.6) | 13 (6.3) | .60 |

| Hypertension in year prior to conception | 8 (9.9) | 8 (6.4) | 16 (7.8) | .36 |

| Substance use disorder in year prior to conception | 1 (1.2) | 5 (4.0) | 6 (2.9) | .25 |

| Alcohol use disorder in year prior to conception | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | .42 |

| Mental health disorder in year prior to conception | 1 (1.2) | 5 (4.0) | 6 (2.9) | .25 |

| Smoking during current pregnancy | .08 | |||

| No | 62 (76.5) | 79 (63.2) | 141 (68.4) | |

| Yes | 4 (4.9) | 5 (4.0) | 9 (4.4) | |

| Unknown | 15 (18.5) | 41 (32.8) | 56 (27.2) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index in year prior to conception | .30 | |||

| 0 | 46 (56.8) | 83 (66.4) | 129 (62.6) | |

| 1 | 24 (29.6) | 29 (23.2) | 53 (25.7) | |

| 2 | 8 (9.9) | 12 (9.6) | 20 (9.7) | |

| 3+ | 3 (3.7) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Individual Charlson comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | .42 |

| Dementia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 (7.4) | 9 (7.2) | 15 (7.3) | .96 |

| Connective tissue/rheumatic disease | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | .21 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Mild liver disease | 1 (1.2) | 5 (4.0) | 6 (2.9) | .25 |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Diabetes without complications | 25 (30.9) | 25 (20.0) | 50 (24.3) | .08 |

| Diabetes with complications | 6 (7.4) | 7 (5.6) | 13 (6.3) | .60 |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | .42 |

| Renal disease | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | .08 |

| Cancer | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | .21 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| AIDS/HIV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Date of conception | .80 | |||

| January-December 2018 | 19 (23.5) | 33 (26.4) | 52 (25.2) | |

| January-December 2019 | 38 (46.9) | 53 (42.4) | 91 (44.2) | |

| January-November 2020 | 24 (29.6) | 39 (31.2) | 63 (30.6) | |

| Single/multiple gestation | .25 | |||

| Singleton pregnancy | 81 (100.0) | 123 (98.4) | 204 (99.0) | |

| Multiple gestation | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Any inpatient visit in year prior to vaccination | 5 (6.2) | 10 (8.0) | 15 (7.3) | .62 |

| Any emergency department visit in year prior to vaccination | 19 (23.5) | 29 (23.2) | 48 (23.3) | .97 |

| Number of outpatient visits in year prior to conception | .64 | |||

| 0 | 7 (8.6) | 5 (4.0) | 12 (5.8) | |

| 1 | 5 (6.2) | 6 (4.8) | 11 (5.3) | |

| 2-4 | 15 (18.5) | 26 (20.8) | 41 (19.9) | |

| 5-9 | 25 (30.9) | 45 (36.0) | 70 (34.0) | |

| 10+ | 29 (35.8) | 43 (34.4) | 72 (35.0) | |

| Number of prior pregnancies | .40 | |||

| 0 | 21 (25.9) | 25 (20.0) | 46 (22.3) | |

| 1 | 22 (27.2) | 29 (23.2) | 51 (24.8) | |

| 2+ | 32 (39.5) | 54 (43.2) | 86 (41.7) | |

| Missing | 6 (7.4) | 17 (13.6) | 23 (11.2) | |

| Number of prior live births | .15 | |||

| 0 | 31 (38.3) | 38 (30.4) | 69 (33.5) | |

| 1 | 20 (24.7) | 43 (34.4) | 63 (30.6) | |

| 2+ | 24 (29.6) | 27 (21.6) | 51 (24.8) | |

| Missing | 6 (7.4) | 17 (13.6) | 23 (11.2) | |

| Number of prior pregnancies not ending in live birth | .44 | |||

| 0 | 47 (58.0) | 64 (51.2) | 111 (53.9) | |

| 1 | 19 (23.5) | 26 (20.8) | 45 (21.8) | |

| 2+ | 9 (11.1) | 18 (14.4) | 27 (13.1) | |

| Missing | 6 (7.4) | 17 (13.6) | 23 (11.2) | |

| Complications of current pregnancy | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | 14 (11.2) | 9 (11.1) | 23 (11.2) | .98 |

| Preeclampsia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Kidney disease | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | .08 |

| Autoimmune disease | 1 (0.8) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (2.4) | .76 |

| COVID-19 disease | 1 (0.8) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (2.4) | .06 |

| Other vaccinations between conception and hepatitis B vaccination (excluding the hepatitis B vaccination date) | ||||

| Influenza | 10 (12.3) | 26 (20.8) | 36 (17.5) | .12 |

| Pneumococcal | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | .42 |

| COVID-19 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| HPV | 1 (1.2) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (1.9) | .55 |

| HepA | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | .21 |

| Hib | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Japanese encephalitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| MMR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Meningococcal | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Polio | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Rabies | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Tdap | 5 (6.2) | 9 (7.2) | 14 (6.8) | .77 |

| Td | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Typhoid | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Varicella | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | .42 |

| Yellow fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Zoster | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Other vaccinations between hepatitis B vaccination and end of pregnancy (excluding hepatitis B vaccination date) | ||||

| Influenza | 36 (44.4) | 45 (36.0) | 81 (39.3) | .23 |

| Pneumococcal | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | N/A |

| COVID-19 | 3 (3.7) | 2 (1.6) | 5 (2.4) | .34 |

| HPV | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | N/A |

| HepA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Hib | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Japanese encephalitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| MMR | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | .25 |

| Meningococcal | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Polio | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Rabies | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Tdap | 61 (75.3) | 72 (57.6) | 133 (64.6) | <.01 |

| Td | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Typhoid | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Varicella | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Yellow fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Zoster | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Other concomitant vaccinations on hepatitis B vaccination date | ||||

| Yes | 32 (39.5) | 47 (37.6) | 79 (38.3) | .78 |

| Influenza | 18 (22.2) | 21 (16.8) | 39 (18.9) | .33 |

| Pneumococcal | 9 (11.1) | 12 (9.6) | 21 (10.2) | .73 |

| COVID-19 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| HPV | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.4) | 3 (1.5) | .16 |

| HepA | 1 (1.2) | 4 (3.2) | 5 (2.4) | .37 |

| Hib | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Japanese encephalitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| MMR | 4 (4.9) | 11 (8.8) | 15 (7.3) | .30 |

| Meningococcal | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | .76 |

| Polio | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Rabies | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Tdap | 2 (2.5) | 7 (5.6) | 9 (4.4) | .28 |

| Td | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Typhoid | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Varicella | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.8) | 6 (2.9) | .05 |

| Yellow fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Zoster | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; HPV, human papillomavirus; HepA, hepatitis A; Hib, Haemophilus influenzae type B; MMR, measles, mumps, rubella; Tdap, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; Td, tetanus-diphtheria.

*Vaccination refers to the first hepatitis B dose during the period from 28 d prior to conception through the end of pregnancy.

Appendix 2. Characteristics of live born infants of individuals exposed to hepatitis B vaccine during the 2 d prior to conception or during pregnancy from August 2018 to November 2020

| HepB-CpG-exposed infants | HepB-alum-exposed infants | Total | p-value | |

| |

N = 68 n (%) |

N = 95 n (%) |

N = 163 n (%) |

|

| Single/multiple gestation | .09 | |||

| Singleton | 68 (100.0) | 91 (95.8) | 159 (97.5) | |

| Twins | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Triplets or greater | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Infant sex | .60 | |||

| Male | 31 (45.6) | 43 (45.3) | 74 (45.4) | |

| Female | 36 (52.9) | 48 (50.5) | 84 (51.5) | |

| Intersex/other/unknown | 1 (1.5) | 4 (4.2) | 5 (3.1) | |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | .75 | |||

| <28 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| 28-31 | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (2.5) | |

| 32-36 | 8 (11.8) | 10 (10.5) | 18 (11.0) | |

| 37-39 | 47 (69.1) | 62 (65.3) | 109 (66.9) | |

| ≥40 | 11 (16.2) | 20 (21.1) | 31 (19.0) | |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | .46 | |||

| Mean ± sd | 37.93 ± 2.13 | 38.06 ± 2.63 | 38.01 ± 2.43 | |

| Median (IQR) | 38 (37-39) | 39 (37-39) | 39 (37-39) | |

| Birth weight, g | .89 | |||

| Mean ± sd | 3286.01 ± 619.56 | 3296.52 ± 665.50 | 3292.01 ± 644.15 | |

| Median (IQR) | 3330 (3000, 3580) | 3320 (2960, 3660) | 3325 (2990, 3635) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.5) | 6 (6.3) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Birth length, cm | .42 | |||

| Mean ± sd | 49.87 ± 3.33 | 49.87 ± 6.84 | 49.87 ± 5.46 | |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (48-52) | 51 (49-52) | 50 (48-52) | |

| Missing | 2 (2.9) | 20 (21.1) | 22 (13.5) | |

| Head circumference, cm | .85 | |||

| Mean (sd) | 33.94 (1.94) | 33.86 (1.97) | 33.90 (1.95) | |

| Median (IQR) | 34 (33-36) | 34 (33-35) | 34 (33-35) | |

| Missing | 2 (2.9) | 27 (28.4) | 29 (17.8) | |

| Birth location | <.01 | |||

| KPSC hospital | 66 (97.1) | 67 (73.6) | 133 (83.6) | |

| Non-KPSC hospital/non-hospital setting | 2 (2.9) | 28 (29.5) | 30 (18.4) |

Abbreviations: sd, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Dynavax Technologies Corporation. The study funder had the right to comment on the study design, interpretation of data, and manuscript content. However, they had no role in the conduct of the study; collection, management, and analysis of the data; preparation of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The sponsor did not have the right to veto publication or to decide to which journal the paper was submitted.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Ackerson, Dr. Bruxvoort, Dr. Qian, Ms. Sy, and Ms. Solano received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies unrelated to this paper. Ms. Solano received research funding from Gilead for studies unrelated to this paper. Dr. Ackerson, Dr. Bruxvoort, Dr. Qian, Ms. Qiu, and Ms. Sy received research funding from Moderna for studies unrelated to this paper. Dr. Ackerson, Dr. Bruxvoort, and Mr. Slezak received research funding from Pfizer for studies unrelated to this paper. Dr. Reynolds received research funding from Novartis, Amgen Inc., and Merck & Co. for studies unrelated to this paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2397872

Author contributions statement

Drs Bruxvoort, Ackerson, Qian, Reynolds, Ms Sy, Mr Slezak, and Ms Qiu were involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and revised the paper critically for intellectual content. Dr Bruxvoort was involved in the drafting of the paper. Ms Solano was involved in the acquisition of the data and revised the paper critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Meeting presentation

Preliminary results of this study were presented at the Annual Conference on Vaccinology Research, June 5–7, 2023, Virtual.

Appendices

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance U.S ., 2021. 2023. Contract No.: 2024 Mar 8.

- 2.Lim JK, Nguyen MH, Kim WR, Gish R, Perumalswami P, Jacobson IM.. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(9):1429–10. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Electronic address pso, Badell ML, Badell M, Prabhu M, Dionne J, Tita ATN. Society for maternal-fetal medicine consult series #69: hepatitis B in pregnancy: updated guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;230(4):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionne-Odom J, Cozzi GD, Franco RA, Njei B, Tita ATN. Treatment and prevention of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(3):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X, Sun D, Li C, Ying J, Yan Y. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and preterm labor(birth) in pregnant women-an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2018;90(1):93–100. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Hepatitis B: perinatal transmission. 2022. [accessed 2024 Feb 9]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/perinatalxmtn.htm.

- 7.Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, Frey S, Ault K, Moore KL, Hall EW, Morgan RL, Campos-Outcalt D, Wester C, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19–59 years: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(13):477–483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HEPLISAV-B Package Insert . 2023. [accessed 2018 May]. https://www.fda.gov/media/108745/download?attachment.

- 9.Heyward WL, Kyle M, Blumenau J, Davis M, Reisinger K, Kabongo ML, Bennett S, Janssen RS, Namini H, Martin JT, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational hepatitis B vaccine with a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) compared to a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in healthy adults 40–70 years of age. Vaccine. 2013;31(46):5300–5305. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson S, Lentino J, Kopp J, Murray L, Ellison W, Rhee M, Shockey G, Akella L, Erby K, Heyward WL, et al. Immunogenicity of a two-dose investigational hepatitis B vaccine, HBsAg-1018, using a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant compared with a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in adults. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruxvoort K, Slezak J, Huang R, Ackerson B, Sy LS, Qian L, Reynolds K, Towner W, Solano Z, Mercado C, et al. Association of number of doses with hepatitis B vaccine series completion in US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2027577. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushner T, Huang V, Janssen R. Safety and immunogenicity of HepB-CpG in women with documented pregnancies post-vaccination: a retrospective chart review. Vaccine. 2022;40(21):2899–2903. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, Romero J, Ward J, Nelson N. Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(15):455–458. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6715a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groom HC, Irving SA, Koppolu P, Smith N, Vazquez-Benitez G, Kharbanda EO, Daley MF, Donahue JG, Getahun D, Jackson LA, et al. Uptake and safety of hepatitis B vaccination during pregnancy: a vaccine safety datalink study. Vaccine. 2018;36(41):6111–6116. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruxvoort K, Slezak J, Qian L, Sy LS, Ackerson B, Reynolds K, Huang R, Solano Z, Towner W, Mercado C, et al. Association between 2-dose vs 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine and acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1260–1268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackerson B, Sy LS, Slezak J, Qian L, Reynolds K, Huang R, Solano Z, Towner W, Qiu S, Simmons SR, et al. Post-licensure safety study of new-onset immune-mediated diseases, herpes zoster, and anaphylaxis in adult recipients of HepB-CpG vaccine versus HepB-alum vaccine. Vaccine. 2023;41(30):4392–4401. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruxvoort K, Sy LS, Ackerson B, Slezak J, Qian L, Towner W, Reynolds K, Solano Z, Carlson CM, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Challenges in phase 4 post-licensure safety studies using real world data in the United States: hepatitis B vaccine example. Vaccine: X. 2021;8:8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2021.100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talge NM, Mudd LM, Sikorskii A, Basso O. United States birth weight reference corrected for implausible gestational age estimates. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):844–853. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birth defects definition group. Descriptions for NBDPN core, recommended, and extended conditions. 2017.

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACOG Committee Opinion No . 741: maternal immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):214–217. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall H, McMillan M, Andrews RM, Macartney K, Edwards K. Vaccines in pregnancy: the dual benefit for pregnant women and infants. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(4):848–856. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1127485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease C, Prevention . Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1709–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory EC, Valenzuela CP, Hoyert DL. Fetal mortality: United States, 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2022;71(4):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osterman M, Hamilton B, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. Births: final data for 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70(17):1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.