Treating acetanilide with aqueous strong acids gives protonation at the amide O atom and a series of anhydrous hemi-protonated salt forms of this simple amide.

Keywords: crystal structure, acetanilide, pharmaceutical, salt selection, protonation, protonated amide

Abstract

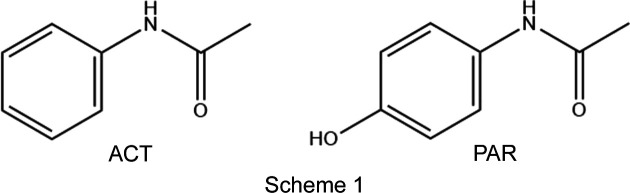

Treating the amide acetanilide (N-phenylacetamide, C8H9NO) with aqueous strong acids allowed the structures of five hemi-protonated salt forms of acetanilide to be elucidated. N-(1-Hydroxyethylidene)anilinium chloride–N-phenylacetamide (1/1), [(C8H9NO)2H][Cl], and the bromide, [(C8H9NO)2H][Br], triiodide, [(C8H9NO)2H][I3], tetrafluoroborate, [(C8H9NO)2H][BF4], and diiodobromide hemi(diiodine), [(C8H9NO)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, analogues all feature centrosymmetric dimeric units linked by O—H⋯O hydrogen bonds that extend into one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chains through N—H⋯X interactions, where X is the halide atom of the anion. Protonation occurs at the amide O atom and results in systematic lengthening of the C=O bond and a corresponding shortening of the C—N bond. The size of these geometric changes is similar to those found for hemi-protonated paracetamol structures, but less than those in fully protonated paracetamol structures. The bond angles of the amide fragments are also found to change on protonation, but these angular changes are also influenced by conformation, namely, whether the amide group is coplanar with the phenyl ring or twisted out of plane.

Introduction

The formation of salt phases of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) is a simple technique used by the pharmaceutical industry to enhance desirable materials properties of an acidic or basic API, whilst retaining the essential functional groups of the organic compound. Often the targeted property is enhanced aqueous solubility (Stahl & Wermuth, 2008 ▸). Salt screening is unlikely to be performed if the API contains only traditionally neutral functional groups, such as amides. All chemists learn at an early stage that amides are much less basic than amines, and it is perhaps this seed that leads to the misidentification or misnaming of amides as ‘non-ionizable’ (Manallack, 2007 ▸; Bethune et al., 2009 ▸). Just because a compound is not normally ionized, or not protonated under normal physiological conditions, does not of course mean that it cannot be protonated given the right conditions. Protonation of amides is common in acidic solution and protonated forms of amides may even be isolated in the solid state to allow characterization by diffraction. In 2012, Nanubolu et al. (2012 ▸) surveyed known crystal structures of protonated amides. Since then, much API relevant work on the crystal structures of protonated amides has concentrated on carbamazepine and its relatives (Perumalla & Sun, 2012 ▸, 2013 ▸; Buist et al., 2013 ▸, 2015 ▸; Buist & Kennedy, 2016 ▸; Eberlin et al., 2013 ▸) and, most importantly to the current work, on paracetamol (Perumalla & Sun, 2012 ▸; Perumalla et al., 2012 ▸; Trzybiński et al., 2016 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2020 ▸). Protonated amide cations are of course themselves strong acids and thus highly unlikely drug candidates. The interest in their isolation and characterization is thus driven by academic interest and by manufacturing considerations, such as utilizing their mechanical properties to change compaction and tableting properties prior to final formulation (Perumalla et al., 2012 ▸). Herein we report five crystal structures of hemi-protonated salt forms of the paracetamol congener acetanilide (ACT). Despite its historical use as a pharmaceutical and its structural similarity to paracetamol, ACT is no longer used as an API (Brodie & Axelrod, 1948 ▸). However, as a fundamental simple amide, it has multiple industrial uses, including as a synthetic precursor in the pharmaceutical industry (Singh et al., 2019 ▸; Li et al., 2024 ▸). The structures presented herein are [(ACT)2H][Cl], [(ACT)2H][Br], [(ACT)2H][I3], [(ACT)2H][BF4] and [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2. Previous solid-state phase work on such a fundamental compound as ACT has been surprisingly limited. Structures previously reported include that of the compound itself (Wasserman et al., 1985 ▸), those of a small number of cocrystal forms (e.g. Megumi et al., 2013 ▸; Oliveira et al., 2013 ▸), and a few structures where ACT acts as a ligand (e.g. Buchner & Müller,, 2023 ▸; Marchetti et al., 2008 ▸).

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

The I3, BF4 and mixed Br/I samples were obtained by dissolving ACT (0.21 g, 1.6 mmol) in methanol (1 ml). Approximately 1 ml of the appropriate concentrated aqueous acid was then added. For the mixed Br/I species, this acid was a 5:1 mixture of HI and HBr. In each case, after 3–7 d of slow evaporation, crystals were deposited. In the case of the mixed Br/I species, orange crystals of the ACT salt form were mixed with colourless crystals of the decomposition product [PhNH3][Br]. Crystals of the Cl salt were prepared in a similar way, but here ACT (0.40 g, 3 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (4 ml) and concentrated HCl (2 ml) added. Using similar techniques with concentrated HBr gave only crystals of [PhNH3][Br]. Crystals of the required Br salt form were thus prepared by dissolving ACT (0.25 g) in concentrated aqueous HBr (2 ml). Crystals of the Br salt were deposited within 3 d.

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▸. Data measured for [(ACT)2H][Br] were treated as twinned by a 180° rotation about [0, 0.71, −0.71] to give a HKLF 5 formatted reflection file. The BASF parameter refined to 0.3996 (13). The structure of the mixed I/Br species was originally refined as [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, with all halide sites ordered. However, residual electron density and displacement parameters suggested that this treatment was not idealized. Individual trial calculations treating each halide site as a mixture of I and Br suggested that a mixed model was appropriate for two of the halide sites. Thus, the I5/Br3 and Br1/I7 sites were modelled as mixed occupancy, each with a total halide occupancy of one. See Section 3 (Results and discussion) for further comment. All H atoms bound to C atoms were placed in idealized positions and refined in riding modes, with C—H = 0.95 and 0.98 Å for CH and CH3 groups, respectively. Uiso values were set at 1.2Ueq or 1.5Ueq of the parent atom for CH and CH3 groups, respectively. H atoms bound to N or to O atoms were refined isotropically, but with the X—H distances restrained to 0.88 (1) Å. The exceptions to this latter statement were [(ACT)2H][Cl], where H atoms bound to N atoms were refined freely and isotropically, and [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, where the half-occupancy H atoms of the OH groups were placed in idealized positions.

Table 1. Experimental details.

Experiments were carried out at 100 K with Cu Kα radiation using a Rigaku Synergy-i diffractometer. H atoms were treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement.

| [(ACT)2H][Cl] | [(ACT)2H][Br] | [(ACT)2H][I3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | |||

| Chemical formula | C8H10NO+·Cl−·C8H9NO | C8H10NO+·Br−·C8H9NO | C8H10NO+·I3−·C8H9NO |

| M r | 306.78 | 351.24 | 652.03 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21/n | Triclinic, P

|

Triclinic, P

|

| a, b, c (Å) | 7.7936 (1), 18.3639 (2), 16.3922 (1) | 7.8794 (2), 9.7748 (3), 16.2720 (4) | 7.3766 (2), 8.8131 (3), 9.3226 (2) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 102.245 (1), 90 | 104.385 (3), 98.342 (2), 96.386 (2) | 113.612 (2), 103.144 (2), 104.263 (3) |

| V (Å3) | 2292.69 (4) | 1186.86 (6) | 500.61 (3) |

| Z | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| μ (mm−1) | 2.26 | 3.59 | 36.86 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.20 × 0.15 × 0.12 | 0.18 × 0.04 × 0.04 | 0.32 × 0.08 × 0.05 |

| Data collection | |||

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (CrysAlis PRO; Rigaku OD, 2023 ▸) | Analytical [CrysAlis PRO (Rigaku OD, 2023 ▸), based on expressions derived by Clark & Reid (1995 ▸)] | Gaussian (CrysAlis PRO; Rigaku OD, 2023 ▸) |

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.725, 1.000 | 0.668, 0.890 | 0.034, 0.480 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 23203, 4444, 4113 | 8381, 8381, 7175 | 7238, 1900, 1846 |

| R int | 0.033 | Not applicable | 0.054 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.615 | 0.615 | 0.615 |

| Refinement | |||

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)], wR(F2), S | 0.031, 0.088, 1.04 | 0.054, 0.164, 1.11 | 0.038, 0.107, 1.10 |

| No. of reflections | 4444 | 8381 | 1900 |

| No. of parameters | 309 | 310 | 115 |

| No. of restraints | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.26, −0.30 | 0.73, −0.90 | 1.24, −1.79 |

| [(ACT)2H][BF4] | [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | ||

| Chemical formula | C8H10NO+·BF4−·C8H9NO | C8H10NO+·I2Br−·C8H9NO·0.5I2 |

| M r | 358.14 | 735.18 |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, P

|

Monoclinic, P21/m |

| a, b, c (Å) | 7.1070 (1), 9.5381 (1), 13.3592 (1) | 5.8956 (1), 18.6224 (4), 19.9632 (4) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 98.765 (1), 98.034 (1), 105.977 (1) | 90, 91.970 (2), 90 |

| V (Å3) | 844.56 (2) | 2190.47 (7) |

| Z | 2 | 4 |

| μ (mm−1) | 1.05 | 36.46 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.10 | 0.24 × 0.08 × 0.06 |

| Data collection | ||

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (CrysAlis PRO; Rigaku OD, 2023 ▸) | Analytical [CrysAlis PRO (Rigaku OD, 2023 ▸), based on expressions derived by Clark & Reid (1995 ▸)] |

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.816, 1.000 | 0.014, 0.164 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 16151, 3261, 3204 | 21645, 4338, 3762 |

| R int | 0.026 | 0.096 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.615 | 0.615 |

| Refinement | ||

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)], wR(F2), S | 0.036, 0.099, 1.04 | 0.052, 0.151, 1.08 |

| No. of reflections | 3261 | 4338 |

| No. of parameters | 241 | 245 |

| No. of restraints | 1 | 2 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.50, −0.29 | 1.50, −1.86 |

Results and discussion

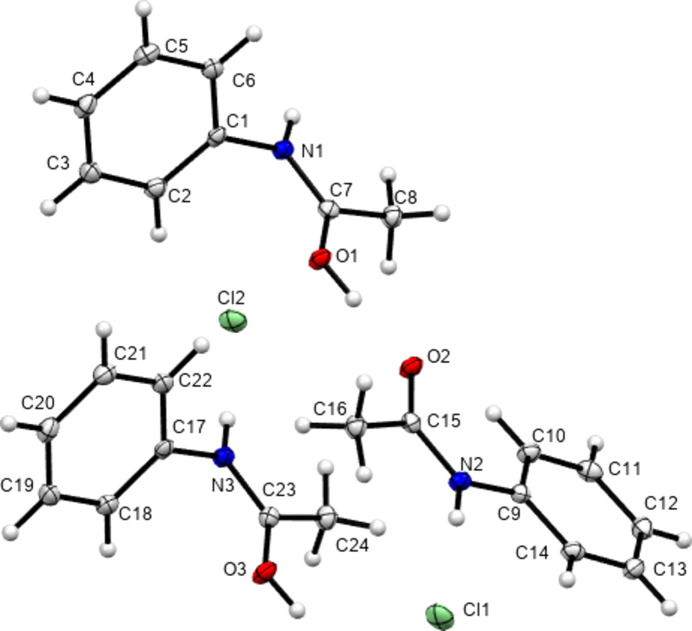

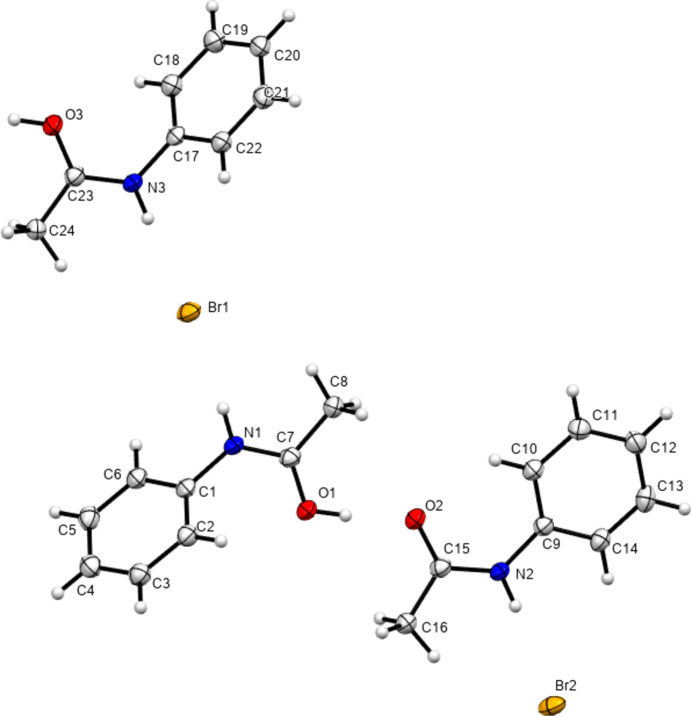

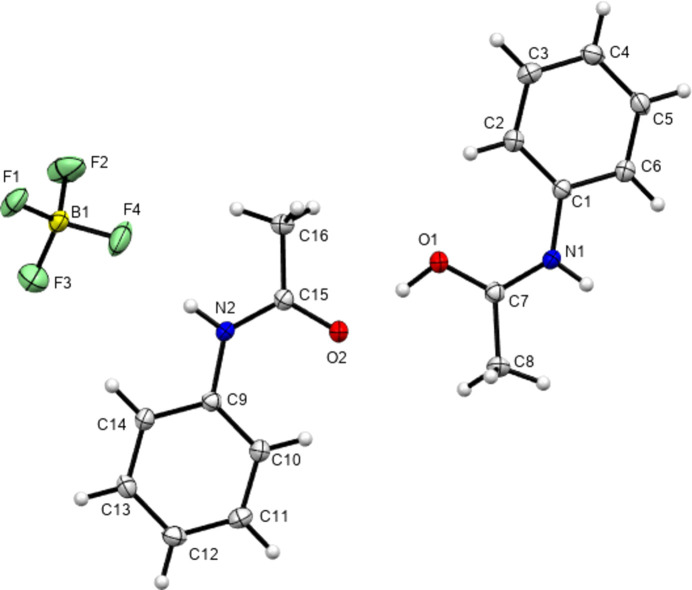

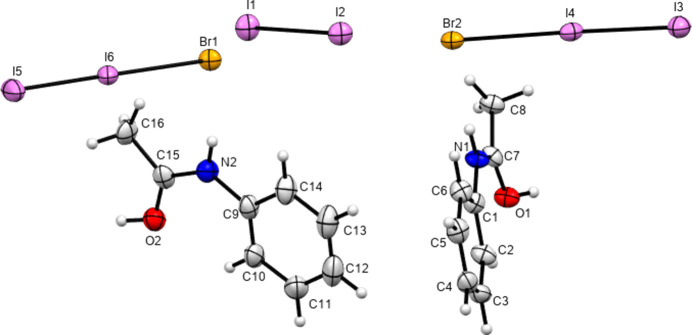

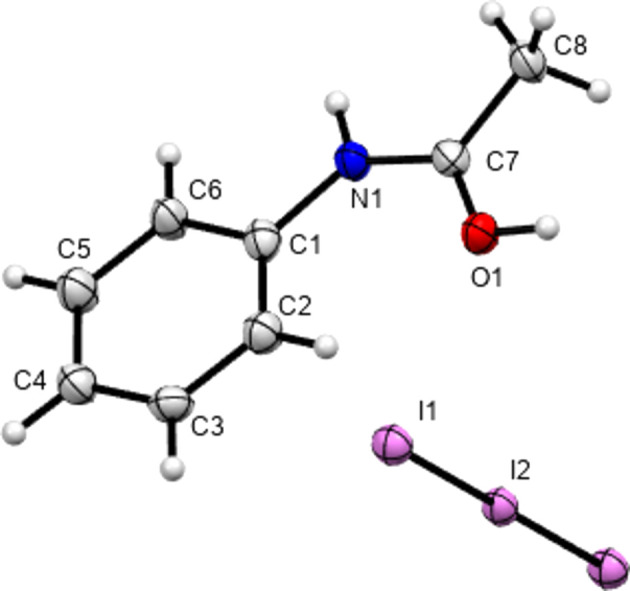

In 2012, Perumalla & Sun (2012 ▸) reported that non-aqueous sources of HCl were capable of protonating amides that concentrated aqueous hydrochloric acid could not, and that non-aqueous sources of HCl could give anhydrous versions of salt forms of amides where aqueous acid could not. It has been shown since that salt forms of amides (including anhydrous salts) are accessible by either simply dissolving the amide in the concentrated aqueous acid or by adding concentrated aqueous acid to alcohol solutions of the amide (Buist et al., 2015 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸). The latter aqueous methods were adopted here using the strong acids HX (X = Cl, Br and I) and HBF4. All isolated crystals containing ACT were found to be anhydrous hemi-protonated salt forms. The asymmetric unit contents of the five structures [(ACT)2H][Cl], [(ACT)2H][Br], [(ACT)2H][I3], [(ACT)2H][BF4] and [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2 are presented in Figs. 1 ▸–5 ▸ ▸ ▸ ▸, with selected crystallographic and refinement parameters given in Table 1 ▸. Note that for the mixed I/Br species, the formula used herein, [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, is a simplified approximation. Two of the halide atom sites were modelled as mixed I/Br sites, see Section 2.2 (Refinement). A small excess of I in the refined model implies the existence of some I3− anions, as well as the majority I2Br−, and gives an overall formula of [(ACT)2H][I2Br]0.93[I3]0.07·0.5I2. All the halide atoms of this structure lie on the mirror plane of the space group P21/m. Well-ordered organic structures containing mixed-halide anions such as I2Br are known (Buist & Kennedy, 2014 ▸), but, as here, structures with mixed I/Br polyhalides are often found to be disordered (e.g. Kobra et al., 2019 ▸; Laukhina et al., 1997 ▸). A recent article describes how the structures of polyiodide and related salt forms can be treated as being formed from X−, X3− and X2 building blocks (Blake et al., 2024 ▸).

Figure 1.

Contents of the asymmetric unit of [(ACT)2H][Cl]. Note that atom Cl1 sits on a crystallographic centre of symmetry. Here and elsewhere, displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level and H atoms are drawn as small spheres of arbitrary size.

Figure 2.

Contents of the asymmetric unit of [(ACT)2H][Br].

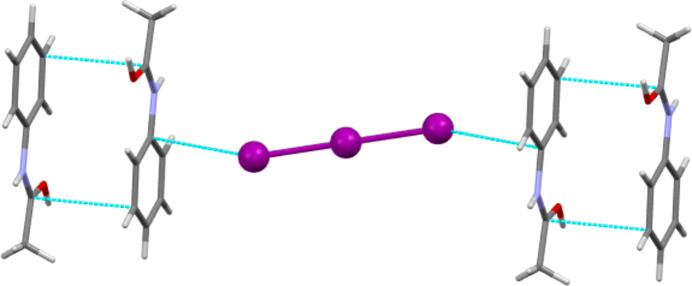

Figure 3.

Contents of the asymmetric unit of [(ACT)2H][I3], expanded to show the complete triiodide anion.

Figure 4.

Contents of the asymmetric unit of [(ACT)2H][BF4].

Figure 5.

Contents of the asymmetric unit of [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, with atoms of the minor disorder positions omitted for clarity.

All five structures are protonated at the amide O atom and all form O—H⋯O hydrogen-bonded dimers between what have been modelled as protonated ACT(H) cations and neutral ACT molecules. Note that, in all cases, free refinement of the H-atom position resulted in the H atom moving towards the centre of the O⋯O separation and that in the given models the acidic H atom has been restrained to sit 0.88 (1) Å from the O atom to which it was found to be closest. The very short O⋯O distances of 2.422 (10)–2.4650 (12) Å indicate strong interactions and it should be borne in mind that the models with distinct ACT(H) and ACT units may in fact represent cases where the H atom is intermediate between the two O-atom positions. A relevant precedent for such an intermediate behaviour is given by Eberlin et al. (2013 ▸). An obvious difference between paracetamol (PAR) and ACT is that, under a wide variety of aqueous, non-aqueous and even solid-grinding preparation methods, PAR tends to give fully protonated [PAR(H)][X] species, where X is Cl, Br, I or a variety of RSO3 anions (Perumalla et al., 2012 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2020 ▸; Trzybiński et al., 2016 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸). In contrast, the only structures of PAR hemi-protonated forms reported are with Cl− and I3− anions (Perumalla & Sun, 2012 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸). That ACT was only found to form hemi-protonated salts may be due to a lower basicity of the amide caused by it lacking the electron-donating para-OH group of PAR. This conjecture is supported by the only other structure available with a protonated (Ar)NHC(O)Me fragment. Reaction of o-tolylNHC(O)Me, which has no strong electron-donating substituent, with nitric acid was found to give a hemi-protonated salt form (Gubin et al., 1989 ▸). All hemi-protonated forms of PAR and of o-tolylNHC(O)Me feature the same dimer motif linked by O—H⋯O hydrogen bonding between protonated and neutral amide functions, as is seen in the five ACT structures.

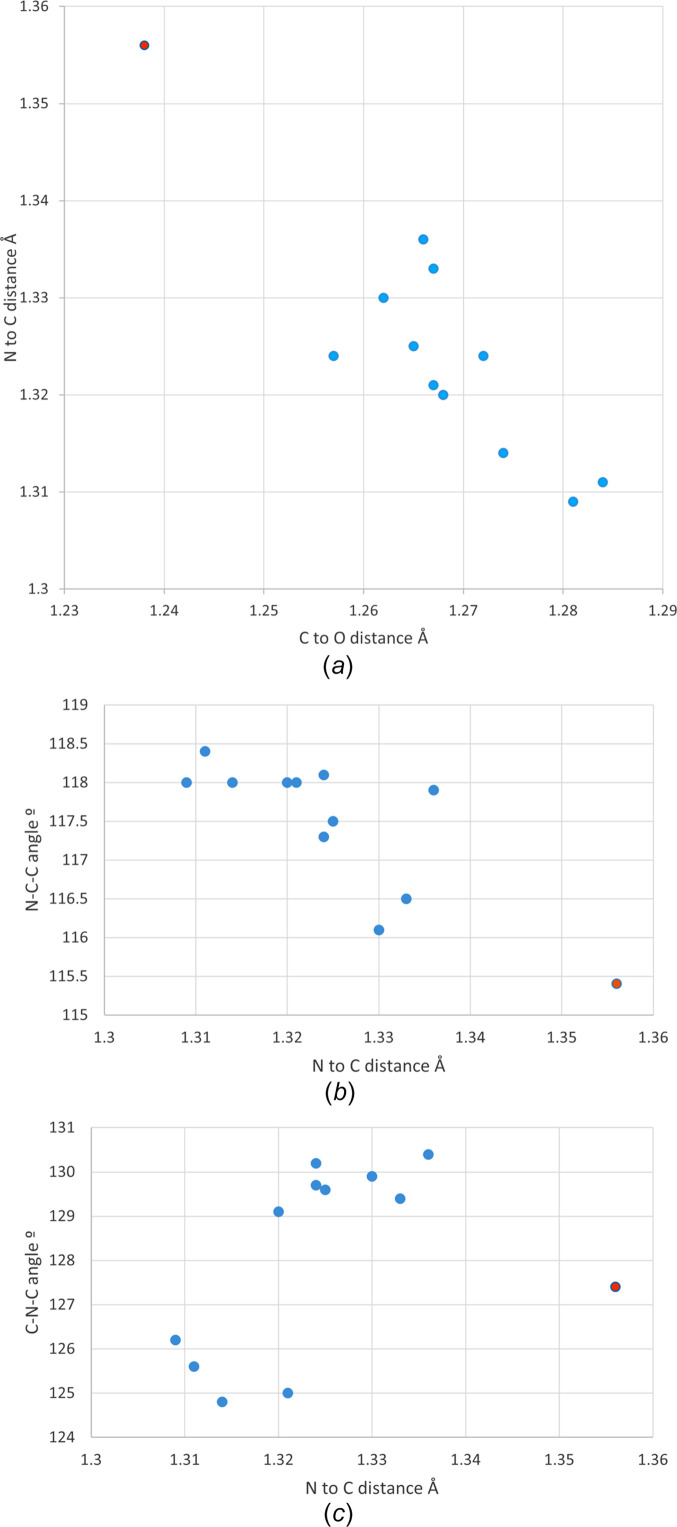

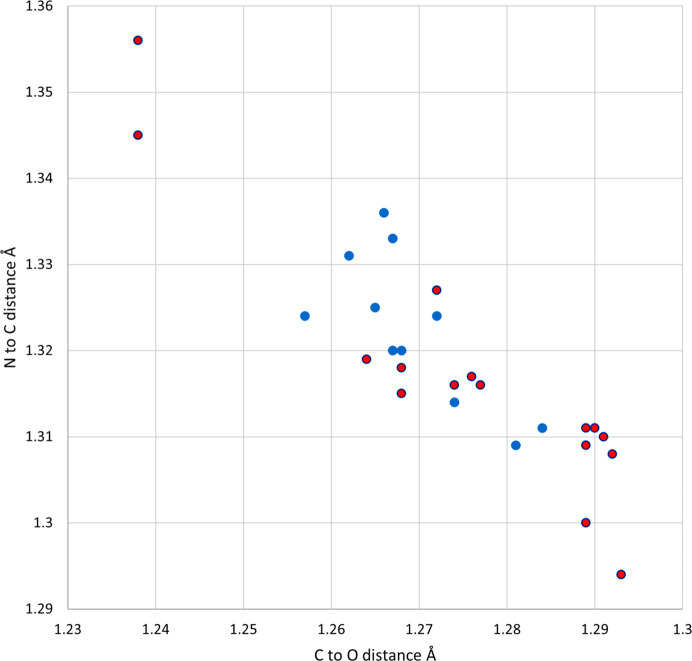

Protonation of the amide in carbamazepine has been shown to lengthen the amide C—O bond and shorten the amide C—N bond, as would be expected for a structure showing resonance of the N-atom lone pair through to the O atom (Buist et al., 2013 ▸; Eberlin et al., 2013 ▸). Similar geometric changes can be seen in the amide groups of the five protonated ACT structures (see Fig. 6 ▸). The C=O bond distances lengthen from 1.238 Å in ACT to a range of 1.257 (5)–1.2843 (15) Å for the ACT(H) species. This is accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the C—N distance from 1.356 Å in ACT to 1.3114 (16)–1.336 (10) Å for ACT(H). That all crystallographically independent ACT fragments show changes in bond lengths indicate that all are affected to some degree by protonation – despite the structural models formally containing both ACT and ACT(H) fragments. Comparison of Fig. 6 ▸ with Fig. 7 ▸ shows that these changes are comparable with those found in the structures of hemi-protonated PAR salt forms (Perumalla & Sun, 2012 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸). They are also similar to the geometric changes caused by coordination of ACT to main group or transition metals (Megumi et al., 2013 ▸; Oliveira et al., 2013 ▸). Fig. 7 ▸ also shows a cluster of points below and to the right of the hemi-protonated species, these are the fully-protonated PAR salt forms which can be seen to show larger deviations from the geometries of the parent APIs than do the hemi-protonated salt forms (Perumalla et al., 2012 ▸; Suzuki et al., 2020 ▸; Trzybiński et al., 2016 ▸; Kennedy et al., 2018 ▸).

Figure 6.

(a) Amide C—O and N—C distances in hemi-protonated ACT(H) structures. Amide N—C distances plotted against (b) N—C—C and (c) C—N—C angles. Blue dots = hemi-protonated ACT species from this article and orange dots = neutral ACT from the high-resolution charge–density data set of Hathwar et al. (2011 ▸).

Figure 7.

Amide C—O and N—C distances in ACT and PAR structures. Blue dots = hemi-protonated ACT species from this article, orange dots = neutral ACT and PAR (Nichols & Frampton, 1998 ▸), and red dots = hemi- and fully-protonated PAR species.

The bond angles of the amide group can also be seen to change upon protonation. The N—C—CH3 angle widens from 115.4° in ACT to between 116.1 (1) and 118.4 (1)° in the ACT(H) fragments. Correspondingly, the O—C—N angle decreases from 123.4° in ACT to between 120.1 (1) and 121.9 (1)° for ACT(H). Plotting N—C—CH3 against the N—C bond length (Fig. 6 ▸) shows that the values for two of the ACT(H) fragments are displaced somewhat towards the values for ACT. Interestingly, these displaced values are for the single crystallographically independent ACT moiety in the Cl and Br structures that are modelled as being nonprotonated. Thus, despite undoubtably having an intermediate-type geometry, these moieties modelled as ACT are truly more ACT-like than are those modelled as ACT(H). The same is not true of the fragment modelled as ACT in the BF4 structure, and careful examination of the residual electron density suggests that the ACT/ACT(H) model adopted here is indeed less suitable and that both fragments should perhaps bear a partial H atom.

A final interesting feature shown in Fig. 6 ▸ is that, on protonation of the amide, the C—N—C angles do not either uniformly widen or narrow. Instead, both behaviours are observed [C—N—C for ACT of 127.4° versus the range 124.8 (3)–130.4 (6)° for the ACT(H) salt forms]. This causes the ACT(H) structures to split into two separate clusters when, for instance, the C—N—C angle is plotted against the N—C distance. The four points where the angle has narrowed correspond to the four fragments with nonplanar conformations, whilst the larger group all have the amide group approximately coplanar with the aromatic ring (compare twist angles of 49.1–57.5 ° for the nonplanar group to twist angles of 2.0–13.6° for the planar group). A similar effect can be seen in the protonated PAR structures from the literature. Of 14 crystallographically independent PAR units, ten are planar and these all show an increase in the C—N—C angle upon protonation. Four structures of protonated PAR structures, those with sulfonate anions, adopt twisted conformations and for these the C—N—C angle remains constant or decreases upon protonation. Presumably an out-of-plane twist reduces steric contacts between the amide fragments and the rings, allowing the angles about the N atom to narrow.

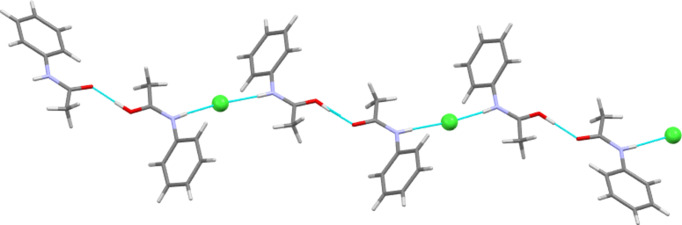

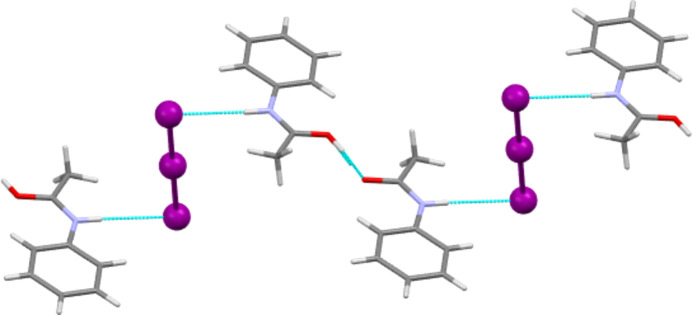

As described above, the main intermolecular feature of each hemi-protonated ACT structure is the strong centrosymmetric O—H⋯O hydrogen-bond contact that forms dimers between ACT molecules and ACT(H) cations. This dimer is also seen in the structures of other hemi-protonated amides. Another intermolecular contact common to all five ACT species herein is that the N—H group always acts as a hydrogen-bond donor to the anion (see Tables 2 ▸–6 ▸ ▸ ▸ ▸ for details). In the Cl, Br and mixed I/Br salt forms, the N—H to anion interactions link the dimers described above to give  (10) one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chains (see Fig. 8 ▸ for an example). In the Cl and Br salts, each chain involves all crystallographically unique molecules and ions, whilst in the mixed I/Br structure, it is only the Br site of each I2Br− anion that accepts hydrogen bonds from N—H and each crystallographically unique ACT fragment propagates a separate hydrogen-bonded chain. The I3 and BF4 salt forms display equivalent chain motifs, but, in these cases, a three-atom link through the body of the anion replaces the single halide atom link above (see Fig. 9 ▸). Thus, these are formally

(10) one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chains (see Fig. 8 ▸ for an example). In the Cl and Br salts, each chain involves all crystallographically unique molecules and ions, whilst in the mixed I/Br structure, it is only the Br site of each I2Br− anion that accepts hydrogen bonds from N—H and each crystallographically unique ACT fragment propagates a separate hydrogen-bonded chain. The I3 and BF4 salt forms display equivalent chain motifs, but, in these cases, a three-atom link through the body of the anion replaces the single halide atom link above (see Fig. 9 ▸). Thus, these are formally  (12) motifs.

(12) motifs.

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for [(ACT)2H][Cl].

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1N⋯Cl2i | 0.854 (18) | 2.237 (19) | 3.0899 (11) | 176.6 (16) |

| N2—H2N⋯Cl1 | 0.851 (18) | 2.297 (18) | 3.1464 (10) | 177.0 (16) |

| N3—H3N⋯Cl2 | 0.844 (18) | 2.275 (18) | 3.1189 (11) | 177.6 (16) |

| O1—H1H⋯O2 | 0.90 (1) | 1.57 (1) | 2.4650 (12) | 175 (3) |

| O3—H2H⋯O3ii | 0.88 (1) | 1.56 (1) | 2.4370 (16) | 176 (7) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Table 3. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for [(ACT)2H][Br].

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1N⋯Br1 | 0.88 (1) | 2.35 (1) | 3.228 (3) | 176 (4) |

| N2—H2N⋯Br2 | 0.88 (1) | 2.44 (1) | 3.316 (3) | 176 (4) |

| N3—H3N⋯Br1 | 0.88 (1) | 2.39 (2) | 3.256 (3) | 174 (4) |

| O1—H1H⋯O2 | 0.89 (1) | 1.57 (2) | 2.454 (4) | 172 (6) |

| O3—H2H⋯O3i | 0.88 (1) | 1.55 (2) | 2.428 (5) | 173 (16) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Table 4. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for [(ACT)2H][I3].

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1N⋯I1i | 0.88 (1) | 2.82 (1) | 3.700 (3) | 178 (5) |

| O1—H1H⋯O1ii | 0.88 (1) | 1.55 (2) | 2.430 (6) | 175 (15) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Table 5. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for [(ACT)2H][BF4].

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1N⋯F1i | 0.854 (18) | 2.007 (19) | 2.8606 (13) | 177.6 (16) |

| N2—H2N⋯F4 | 0.859 (17) | 2.033 (18) | 2.8744 (14) | 166.0 (15) |

| O1—H1H⋯O2 | 0.91 (1) | 1.53 (1) | 2.4333 (12) | 174 (3) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Table 6. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2.

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1N⋯Br2 | 0.88 (1) | 2.49 (1) | 3.367 (5) | 175 (7) |

| N2—H2N⋯Br1 | 0.88 (1) | 2.69 (2) | 3.546 (10) | 164 (7) |

| O1—H1H⋯O1i | 0.88 | 1.62 | 2.442 (10) | 155 |

| O2—H2H⋯O2ii | 0.88 | 1.58 | 2.434 (10) | 164 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Figure 8.

The one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chain formed by O—H⋯O and N—H⋯Cl contacts in [(ACT)2H][Cl]. Similar chains are present in the Br and I/Br salt structures.

Figure 9.

The stepped one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chain formed by O—H⋯O and N—H⋯I contacts in [(ACT)2H][I3]. A similar chain motif is present in [(ACT)2H][BF4], but here the steps caused by the linear I3− anion are absent.

Other intermolecular contacts of around the sum of the van der Waals radii or less are more variable. The I3, BF4 and mixed I/Br salt forms all feature π–π interactions between ACT fragments [minimum C⋯C distances of 3.330 (7), 3.355 (2) and 3.348 (11) Å for the I3, BF4 and mixed I/Br salts, respectively]. For the latter species, this is between offset parallel ACT units, and for the I3 and BF4 salt forms, this is between antiparallel units. Fig. 10 ▸ shows the π–π interactions of [(ACT)2H][I3] and also illustrates the last type of intermolecular contact to be highlighted here. The Cl, Br and I3 salt forms all feature short π-geometry contacts between halide atoms and C atoms adjacent to the N atom of the formally positively charged amide group. The C⋯X distances are 3.3286 (12), 3.469 (4) and 3.677 (4) Å for the Cl, Br and I3 salts, respectively. For Cl and Br, these distances are to the carbonyl C atom, but for I3, the closest contact is to atom C1 of the phenyl ring.

Figure 10.

Section of the structure of [(ACT)2H][I3], showing both antiparallel π–π contacts between ACT fragments and π-geometry C⋯I contacts between the amide and the anion.

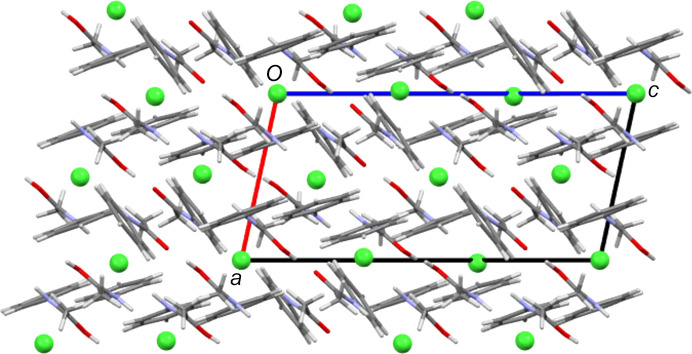

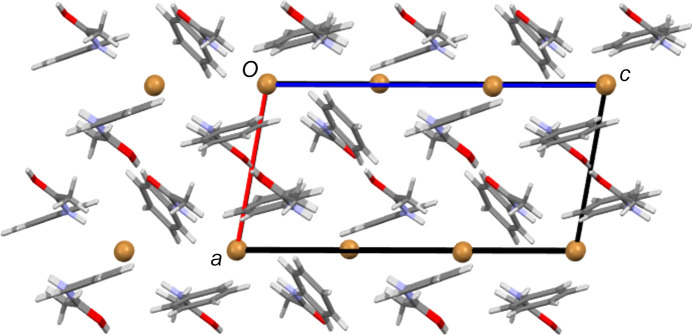

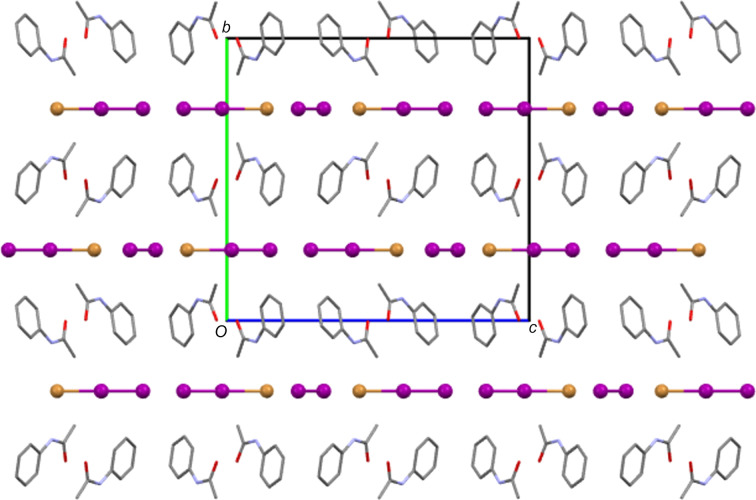

In many ways, the structures of the Cl and Br salt forms are very similar. Both contain three crystallographically independent ACT fragments, two of which have twisted conformations, and two halide sites, one of which is a crystallographic centre of symmetry. As Table 7 ▸ shows, they also feature the same types of intermolecular interactions. Despite this, the two salt forms have different packing structures. Comparing Figs. 11 ▸ and 12 ▸ shows that the Br salt forms a layered structure with alternating layers of anions and bilayers of ACT species, whilst in the Cl salt structure, there are no complete anion layers due to their interruption by amide fragments. Of the other structures, the I3 and mixed I/Br salt forms give structures with alternate monolayers of anions and organic species (see Fig. 13 ▸), whilst the BF4 salt does not form layers.

Table 7. Intermolecular interactions found in hemi-protonated ACT structures.

| Anion | O—H⋯O dimer | Hydrogen-bonded chain | π-anion | π–π | Layering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Br | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| I3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BF4 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| I2Br | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Figure 11.

The packing structure of [(ACT)2H][Cl], viewed along the b axis.

Figure 12.

The packing structure of [(ACT)2H][Br], viewed along the b axis. Note the layers of halide ions and bilayers of ACT fragments that alternate along the a direction.

Figure 13.

The packing structure of [(ACT)2H][I2Br]·0.5I2, with H atoms and minor disorder components omitted for clarity. The view is down the a axis. Note the layers of halide atoms and ACT fragments that alternate along the b direction.

Summary

The structures of five anhydrous hemi-protonated salt forms of the simple amide ACT are presented. That no fully protonated forms were isolated is a fundamental difference from ACT’s close congener PAR. All five structures are based around O—H⋯O-contacted ACT(H)–ACT dimers that further link into one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chains through N—H⋯anion hydrogen bonds. Both amide bond lengths and bond angles change upon protonation. As expected from resonance considerations, the C=O bond lengthens and the C—N bond shortens. The magnitude of these deviations from the geometry of neutral ACT are in line with similar changes seen in hemi-protonated PAR but less than those seen in fully protonated PAR salts. That care should be taken in ascribing all observed changes to protonation is shown by the C—N—C angle. Here large changes seem to be associated more with a change in conformation between planar and twisted units than they are with protonation of the amide.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) ACTHCl, ACTHBr, ACTHI3, ACTHBF4, ACTHI2Br, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHCl. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHClsup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHBr. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBrsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHI3. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI3sup4.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHBF4. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBF4sup5.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHI2Br. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI2Brsup6.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHClsup7.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBrsup8.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI3sup9.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBF4sup10.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI2Brsup11.cml

References

- Bethune, S. J., Huang, N., Jayasankar, A. & Rodríguez-Hornedo, N. (2009). Cryst. Growth Des.9, 3976–3988.

- Blake, A. J., Castellano, C., Lippolis, V., Podda, E. & Schröder, M. (2024). Acta Cryst. C80, 311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brodie, B. B. & Axelrod, J. (1948). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.94, 22–28. [PubMed]

- Buchner, M. R. & Müller, M. (2023). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.649, e202200347.

- Buist, A. R., Edgeley, D. S., Kabova, E. A., Kennedy, A. R., Hooper, D., Rollo, D. G., Shankland, K. & Spillman, M. J. (2015). Cryst. Growth Des.15, 5955–5962.

- Buist, A. R. & Kennedy, A. R. (2014). Cryst. Growth Des.14, 6508–6513.

- Buist, A. R. & Kennedy, A. R. (2016). Acta Cryst. C72, 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buist, A. R., Kennedy, A. R., Shankland, K., Shankland, N. & Spillman, M. J. (2013). Cryst. Growth Des.13, 5121–5127.

- Clark, R. C. & Reid, J. S. (1995). Acta Cryst. A51, 887–897.

- Eberlin, A. R., Eddleston, M. D. & Frampton, C. S. (2013). Acta Cryst. C69, 1260–1266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, L. J. (2012). J. Appl. Cryst.45, 849–854.

- Gubin, A. I., Buranbaev, M. Zh., Erkasov, R. Sh., Nurakhmetov, N. N. & Khakimzhanova, G. D. (1989). Krystallografiya, 34, 1305–1306.

- Hathwar, V. R., Thakur, T. S., Row, T. N. G. & Desiraju, G. R. (2011). Cryst. Growth Des.11, 616–623.

- Kennedy, A. R., King, N. L. C., Oswald, I. D. H., Rollo, D. G., Spiteri, R. & Walls, A. (2018). J. Mol. Struct.1154, 196–203.

- Kobra, K., Li, Y., Sachdeva, R., McMillen, C. D. & Pennington, W. T. (2019). New J. Chem.43, 12702–12710.

- Laukhina, E. E., Narymbetov, B. Zh., Zorina, L. V., Khasanov, S. S., Rozenberg, L. P., Shibaeva, R. P., Buravov, L. I., Yagubskii, E. B., Avramenko, N. V. & Van, K. (1997). Synth. Met.90, 101–107.

- Li, K. W., Dong, S. F., Li, S. L., Chen, Z. Q. & Yin, G. C. (2024). Org. Biomol. Chem.22, 4089–4095. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C. F., Sovago, I., Cottrell, S. J., Galek, P. T. A., McCabe, P., Pidcock, E., Platings, M., Shields, G. P., Stevens, J. S., Towler, M. & Wood, P. A. (2020). J. Appl. Cryst.53, 226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manallack, D. T. (2007). Perspectives Med. Chem.1, 25–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, F., Pampaloni, G. & Zacchini, S. (2008). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2008, 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Megumi, K., Yokota, S., Matsumoto, S. & Akazome, M. (2013). Tetrahedron Lett.54, 707–710.

- Nanubolu, J. B., Sridhar, B. & Ravikumar, K. (2012). CrystEngComm, 14, 2571–2578.

- Nichols, C. & Frampton, C. S. (1998). J. Pharm. Sci.87, 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, F. C., Denadai, A. M. L., Guerra, L. D. L., Fulgêncio, F. H., Windmöller, D., Santos, G. C., Fernandes, N. G., Yoshida, M. I., Donnici, C. L., Magalhães, W. F. & Machado, J. C. (2013). J. Mol. Struct.1037, 1–8.

- Perumalla, S. R., Shi, L. & Sun, C. C. (2012). CrystEngComm, 14, 2389–2390.

- Perumalla, S. R. & Sun, C. C. (2012). Chem. A Eur. J.18, 6462–6464. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perumalla, S. R. & Sun, C. C. (2013). CrystEngComm, 15, 8941–8946.

- Rigaku OD (2019). CrysAlis PRO. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Ltd, Yarntown, Oxfordshire, England.

- Rigaku OD (2023). CrysAlis PRO. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Ltd, Yarntown, Oxfordshire, England.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015a). Acta Cryst. A71, 3–8.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015b). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Singh, R. K., Kumar, A. & Mishra, A. K. (2019). Lett. Org. Chem.16, 6–15.

- Stahl, P. H. & Wermuth, C. G. (2008). Editors. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Salts: Properties, Selection and Use. Zurich: VHCA.

- Suzuki, N., Kanazawa, T., Takatori, K., Suzuki, T. & Fukami, T. (2020). Cryst. Growth Des.20, 590–599.

- Trzybiński, D., Domagała, S., Kubsik, M. & Woźniak, K. (2016). Cryst. Growth Des.16, 1156–1161.

- Wasserman, H. J., Ryan, R. R. & Layne, S. P. (1985). Acta Cryst. C41, 783–785.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) ACTHCl, ACTHBr, ACTHI3, ACTHBF4, ACTHI2Br, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHCl. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHClsup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHBr. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBrsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHI3. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI3sup4.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHBF4. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBF4sup5.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) ACTHI2Br. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI2Brsup6.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHClsup7.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBrsup8.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI3sup9.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHBF4sup10.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624007332/ef3058ACTHI2Brsup11.cml