Abstract

Mangrove ecosystems are crucial for protecting littoral regions, preserving biodiversity and sequestering carbon. The implementation of effective conservation and management strategies requires a comprehensive understanding of mangrove community structure, canopy coverage and overall health. This investigation focused on four small islands located within the Bunaken National Park in Indonesia: Bunaken, Manado Tua, Mantehage and Nain. Utilising the line transect quadrant method and hemispherical photography, the investigation comprised a total of 12 observation stations. Nain had the greatest average canopy coverage at 76.09%, followed by Mantehage, Manado Tua and Bunaken at 75.82%, 71.83% and 70.01%, respectively. Mantehage had the maximum species density, with 770.83 ind/ha, followed by Bunaken, Nain and Manado Tua with 675 ind/ha, 616.67 ind/ha and 483.34 ind/ha, respectively. The predominant sediment type observed was sandy mud and the mangrove species identified were Avicennia officinalis (AO), Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (BG), Rhizophora apiculata (RA), R. mucronata (RM), and Sonneratia alba (SA). On the small islands, S. alba emerged as the dominant mangrove species based on the importance value index (IVI). In addition, the Mangrove Health Index revealed that only 6.79% of the region exhibited poor health values, while 50% of the region was categorised as being in outstanding condition. These findings indicate that the overall condition of mangroves on these islands was relatively favourable.

Keywords: Mangrove Ecosystem, Mangrove Health Index, Community Structure, Bunaken National Park

Highlights.

The health condition of the mangrove community can be considered relatively good, falling within the moderate category as indicated by the Mangrove Health Index (MHI) values. Approximately 6.79% of the area displays poor health condition, whereas 50% of the area was classified as being in excellent condition.

Sonneratia alba species demonstrated the highest Importance Value Index (IVI), while Rhizophora apiculata species exhibited the lowest IVI.

The mangrove community on these islands encompasses five different species, namely Avicennia officinalis, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, R. apiculata, R. mucronate and S. alba. The mangrove density ranged from 483.34 ind/ha to 770 ind/ha, with the average canopy cover falling between 70.04% and 76.09%.

INTRODUCTION

The global extent of mangrove ecosystems is estimated at 15 million hectares (ha), providing habitat for diverse marine organisms and offering various benefits to human populations (Carugati et al. 2018). Indonesia harbours the largest mangrove ecosystem worldwide, covering 22.6% of the total global area. The Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry reported that the country’s mangrove area spaned approximately 3.36 million ha (Rahadian et al. 2019). This extensive distribution can be attributed to Indonesia’s geographic location in the tropics, second-longest coastline globally and flat coastal geomorphology, which favour the growth of mangroves on land and small islands (Nugroho et al. 2019; Kusmana et al. 2020; Dharmawan & Pramudji 2020; Insani et al. 2020).

Within the mangrove ecosystem, litter plays a fundamental role as the primary component of the food chain. Litter comprises plant leaves, branches, fruits and stems, which are decomposed by microorganisms, resulting in detritus particles that serve as a food source for filter-feeding aquatic organisms. The productivity of mangrove litter was estimated to be 7 to 8 tonnes per year per hectare (Alongi et al. 2002; Holmer & Olsen 2002). Mangroves thrive in intertidal areas and exhibit adaptability to salinity. They also interact with both fresh and seawater, forming a cohesive ecosystem that supports the survival of associated biota, including aquatic and terrestrial flora and fauna (Lugo & Snedaker 1974; Friess 2016a; Romanach et al. 2018; Martin et al. 2019; Macintosh 1991).

The services provided by mangrove ecosystems are vital for human well-being; however, these services are increasingly threatened by the impacts of climate change (Friess 2016b). While mangrove forests are globally recognised as highly productive coastal ecosystems, they are also vulnerable to human disturbances (Elith & Leathwick 2009; Lee et al. 2019). Additionally, mangroves form complex topographic systems that provide habitats alongside seagrasses and coral reefs, offering natural protection against erosion and tidal flooding. However, these systems are becoming increasingly susceptible to anthropogenic effects and have suffered degradation in several locations (Beck et al. 2011; Duarte et al. 2013; Narayan et al. 2016; Goldberg et al. 2020). Other anthropogenic pressures include urban development, agricultural activities leading to fertiliser and pesticide use, eutrophication, overfishing and heavy metal pollutants. Furthermore, natural disasters and the threat of climate change pose significant risks to the habitat functions of mangrove ecosystems (Brent et al. 2015; Hashim & Hughes 2010; Barbier et al. 2008). Ecological services provided by the coastal ecosystems including the mangrove, seagrass and coral reef of Indonesia, support livelihoods of many (Husain et al. 2020). As climate change leads to rising sea levels, mangroves play a crucial role in protecting small islands, making them an essential ecosystem.

Despite Indonesia having the world’s largest mangrove ecosystem, it is not exempted from high threats, with a decrease in mangrove area of approximately 140,000 ha since 2012. Mangrove degradation in the country is one of the largest worldwide and has significant implications for climate change (Richards & Friess 2016; Ilman et al. 2016). The loss of mangrove ecosystems greatly impacts hydrodynamic and geomorphological conditions, affecting their growth (Hurst et al. 2015). Reduced water flow can lead to sediment accumulation, which is then stabilised by the mangrove root system (Duarte et al. 2013). Activities such as mangrove planting, restoration and protection are crucial for mitigating the effects of climate change and understanding the current conditions. Research on climate change events and their effects on natural ecosystems typically involves field and modeling studies (Alexander 2016; Grant et al. 2017; Shan et al. 2021).

Given the functions and challenges faced by the ecosystem in this particular location, a study focusing on mangrove health is necessary. The Mangrove Health Index (MHI) is a commonly used analysis to assess the overall health of mangrove ecosystems. It involves combining information from various health indicators, such as tree density, canopy cover, species diversity, and sedimentation rates. The MHI enables comparisons of mangrove health among different locations or regions. For example, it can be used to compare the health of mangrove forests in different countries or to identify areas where conservation and restoration efforts are most needed. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the MHI, community structure, and canopy cover of mangroves on the small islands of Bunaken National Park, including Mantehage, Bunaken, Nain and Manado Tua. Mantehage Island, Indonesia’s furthest island, is particularly important to study. The results will complement the database on the potential coastal resources of small islands. Consequently, comprehensive data on seagrass beds and coral reefs from the previous year can be combined to provide information on the condition of the mangrove ecosystem (Schaduw et al. 2020; Schaduw & Kondoy 2020). The findings from this study will inform policymakers in developing conservation and sustainable utilisation regulations for the mangrove ecosystem on the small islands of Bunaken National Park.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Site and Determination of Sampling Unit

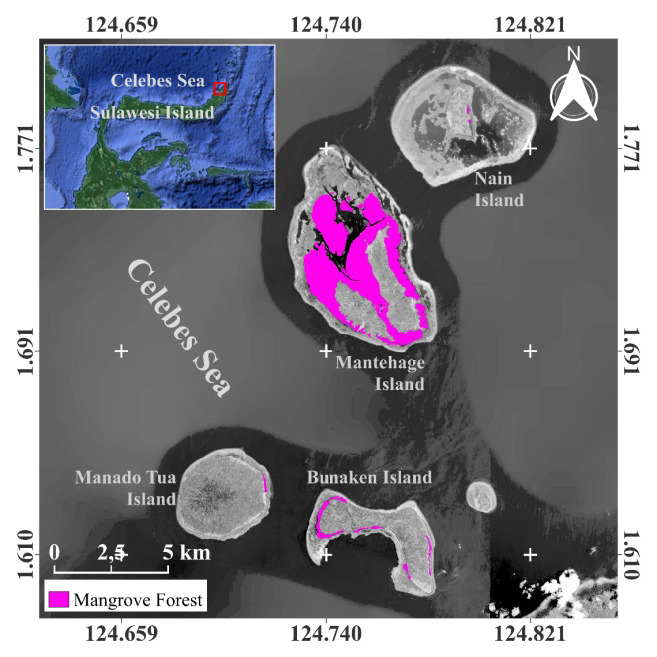

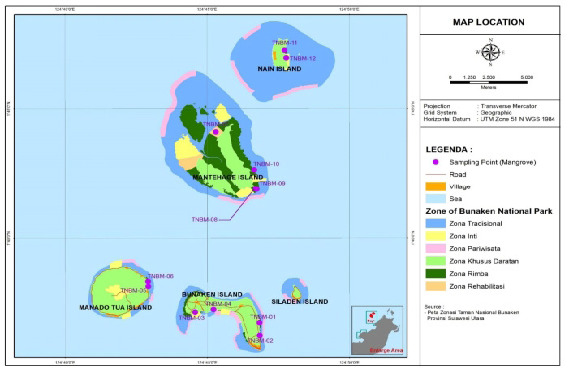

The present investigation was carried out within the small islands of Bunaken National Park, which encompass a mangrove ecosystems of the island Bunaken, Manado Tua, Mantehage and Nain. The study was conducted from August 2022 to May 2023. The research site was situated within two administrative regions of North Sulawesi Province, namely Manado City and North Minahasa Regency. Among the five small islands, only four were found to have a mangrove ecosystem, as depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 36 plots were established, distributed across 12 observation stations on each of the small islands, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Map of mangrove distribution at study locations.

Figure 2.

Study location and sampling point.

Community Structure

Community structure data were obtained by conducting surveys within each 10 m × 10 m plot. The mangrove stem diameters were measured with the stratified purposive sampling method. A minimum of three plots were sampled within each zone, and the circumference of each mangrove stem was recorded for all trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) of ≥ 16 cm. To mark each stem, spray paint with a width of less than 5 cm was used to encircle the tree. The measurements of stem circumference were then utilised to derive data on diameter (DBH), basal area, frequency, density, species dominance and the IVI. Additionally, satellite image analysis was employed to gather information on community structure and canopy cover, aiding in the determination of the area’s location and the overall community structure (Dharmawan, Suyarso, et al. 2020; Dharmawan, Hadi, et al. 2020). To identify all mangrove trees within each plot, reference books on mangrove identification were consulted (Tomlinson 1986; Kitamura et al. 1999; Noor et al. 1999; Giesen et al. 2006; Tomlinson 2016).

Canopy Cover of Mangrove Communities

The hemispherical photography method was employed as one of the techniques to analyse canopy characteristics in the mangrove community. This method involves using photos taken through a wide-angle lens to estimate the amount of sunlight radiation and determine the percentage of plant cover (Anderson 1964). Hemispherical photos were captured using a smartphone camera with a resolution of 5 MP (Ptotal = 5,038,848 pixels), following the established requirements described by (Dharmawan, Suyarso, et al. 2020; Dharmawan, Hadi, et al. 2020). These photos were taken perpendicular to the sky, and each 10 × 10 m2 plot was divided into subplots or quadrants to determine the photo-taking positions based on the mangrove forest conditions. The percentage of mangrove canopy cover was calculated using the hemispherical photography method, which involved capturing photos at specific points (Jenning et al. 1999; Korhonen et al. 2006). Although relatively new for mangrove forests in Indonesia, this technique was easy to implement and provided more accurate data. The analysis involved separating the sky and vegetation pixels, and the percentage of vegetation canopy pixels was calculated using binary image analysis (Ishida 2004). In each plot, five photos were taken to obtain a representative sample, which was then analysed using ImageJ software to determine the number of pixels representing the canopy (P255). The percentage of canopy cover (C) in the mangrove community was calculated using Equation 1.

| (1) |

where C = canopy cover; p255 = Konstanta canopy pixel and ptotal = pixel picture.

Data Analysis

The collected data on canopy percentage, tree density, diameter and basal area were subjected to descriptive quantitative analysis to determine the mean values and standard errors for each zone. The mean values of these parameters and the IVI for each species across the entire mangrove area in the small islands of Bunaken National Park were calculated, taking into account the proportion in each zone (Dharmawan, Suyarso, et al. 2020). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was conducted to assess the normal distribution of the data, followed by parametric analysis. Additionally, analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was performed on each parameter to identify differences in mean values among the zones.

For the interpolation of MHI values using remote sensing vegetation indices, linear regression analysis was conducted for each vegetation index. This analysis aimed to determine the best interpolation model for MHI values based on a single-band image. The Stepwise-Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to evaluate the possible influence of multiple vegetation indices on the MHI value. The interpolation model with the highest regression coefficient (R2-adjusted) value was selected, and MHI distribution was mapped based on this model. The area of each MHI category, derived from the results of the best model interpolation, was calculated using QGIS software (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021). The accuracy of the interpolation was assessed using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) method (Muhsoni et al. 2018).

Mangrove Health Index (MHI) Analysis

The MHI serves as a valuable tool for monitoring changes in mangrove health over time and prioritising areas that require restoration and conservation efforts. Higher MHI values indicate a healthier mangrove ecosystem with improved ecological functioning, while lower values indicate ecosystem degradation or damage.

The MHI value for each plot was derived from three key components of the mangrove community structure parameters: the percentage scores of community canopy cover (SC), tree density (Snsp) and tree diameter (Sdbh). These components were calculated using Equations 2–5 as outlined in (Dharmawan, Suyarso, et al. 2020). To perform the MHI interpolation, a linear regression analysis was conducted to identify the most significant coefficient between MHI and remote sensing-based vegetation indices (Table 1). The satellite imagery used for this analysis was obtained from the Sentinel-2 satellite with the code L1C_T52MHE_A028485_20201205T013711 (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021). Prior to the analysis, the satellite image underwent atmospheric and geometric correction using the Semi-Automatic Classification Plug-in (SCP) within the QGIS software, following the method described by Purwanto and Ardli (2020).

Table 1.

Vegetation indices based on remote sensing analysis (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021).

| Vegetation indices Reference | Formula |

|---|---|

| NDVI (Normalised Difference Vegetation Index)1 | |

| MI (Mangrove Index)1 | |

| MVI (Mangrove Vegetation Index)2 | |

| SAVI (Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index)1 | |

| NBR (Normalised Burn Ratio)1 | |

| GCI (Green Chlorophyll Index)1 | |

| EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index)1 | |

| SIPI (Structure Insensitive Pigment Index)1 | |

| ARVI (Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index)1 |

Notes: NIR = Near infrared; SWIR = Short-wave infrared; L = 1; G = 2.5, C1 = 6; C2 = 7.5.

(References: 1(Dharmawan, Suyarso, et al. 2020; 2Baloloy et al. 2020)

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where Sc = score value of community cover percentage; Snsp = sapling density; and SDBH = tree-spaling diameter.

RESULTS

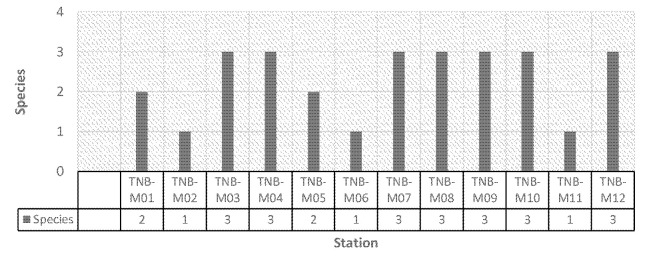

The number of mangrove species varied among the islands, as illustrated in Fig. 3, Table 2 and Table 3. These species included Avicennia officinalis (AO), Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (BG), Rhizophora apiculata (RA), Rhizophora mucronata (RM) and Sonneratia alba (SA). Specifically, Bunaken and Mantehage had four mangrove species, Nain had three and Manado Tua Island had two. However, S. alba was present on all of the small islands, as depicted in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Number of mangrove types at each station.

Table 2.

Station, geographical coordinates, sediment and species.

| No | Island | Local name | Station | Coordinate | Sediment | Number of species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Long | Lat | ||||||

| 1 | Bunaken | Bunaken Timur | TNB-M01 | 124°46′50,05″ | 01°36′45,31″ | Muddy sand | 2 |

| Bunaken Negeri | TNB-M02 | 124°44′34,28″ | 01°37′09,45″ | Muddy sand | 1 | ||

| Alung Banua | TNB-M03 | 124°46′50,34″ | 01°36′15,93″ | Muddy sand | 3 | ||

| Alung Banua | TNB-M04 | 124°45′12,89″ | 01°37′16,23″ | Muddy sand | 3 | ||

| 2 | Manado Tua | Papindang | TNB-M05 | 124°42′55,40″ | 01°38′08,93″ | Muddy sand | 2 |

| Papindang | TNB-M06 | 124°42′54,83″ | 01°38′20,31″ | Muddy sand | 1 | ||

| 3 | Mantehage | Buhias | TNB-M07 | 124°45′18,21″ | 01°44′06,23″ | Muddy sand | 3 |

| Tangkasi | TNB-M08 | 124°46′44,46″ | 01°41′53,26″ | Muddy | 3 | ||

| Tinongko | TNB-M09 | 124°46′42,17″ | 01°41′54,17″ | Muddy sand | 3 | ||

| Tinongko | TNB-M10 | 124°46′39,29″ | 01°42′38,98″ | Muddy sand | 3 | ||

| 4 | Nain | Tarente | TNB-M11 | 124°47′43,11″ | 01°47′13,81″ | Muddy sand | 1 |

| Tarente | TNB-M12 | 124°47′46,85″ | 01°46′56,35″ | Muddy sand | 3 | ||

Table 3.

Mangrove types on each island.

| Species | Island | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Bunaken | Manado Tua | Mantehage | Nain | |

| Avicennia officinalis (AO) | × | |||

| Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (BG) | × | |||

| Rhizophora apiculata (RA) | × | × | × | × |

| Rhizophora mucronata (RM) | × | × | × | |

| Sonneratia alba (SA) | × | × | × | × |

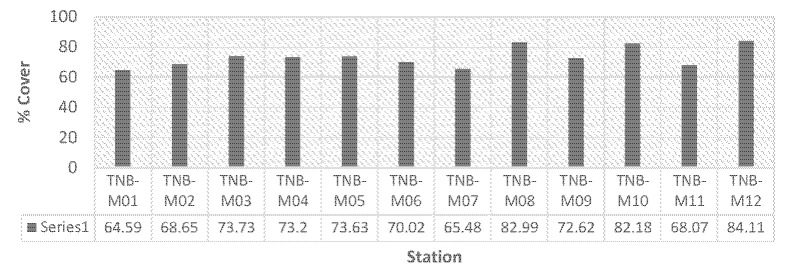

The percentage of canopy cover was assessed on various islands within Bunaken National Park. On Bunaken Island, the canopy cover ranged from 64.59% to 73.73%. Meanwhile, on Manado Tua Island, the range was between 70.02% and 73.63%. Mantehage Island and Nain Island exhibited canopy cover ranges of 65.48% to 82.99% and 68.07% to 84.11%, respectively, as presented in Table 4. Nain Island had the highest average percentage of canopy cover at 76.09%, followed by Mantehage, Manado Tua and Bunaken Island at 75.82%, 71.83% and 70.04%, respectively, as displayed in Fig. 4. The TNB-M12 station on Nain Island had the highest recorded canopy cover, while the TNB-M01 station on Bunaken Island had the lowest recorded canopy cover.

Table 4.

Canopy closure, density, and importance value index (IVI).

| No | Island | Local name | % cover | Density (ind/ha) | IVI | % cover (average) | Density (average) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Min | Max | |||||||

| 1 | Bunaken | Bunaken Timur | 64.59 ± 8.12 | 733.33 ± 70.33 | RM 16.66 | SA 283.34 | 70.04 | 675.00 |

| Bunaken Negeri | 68.65 ± 5.29 | 500 ± 49.35 | SA 300 | |||||

| Alung Banua | 73.73 ± 15.08 | 900 ± 89.76 | AO 18.42 | SA 199.12 | ||||

| Alung Banua | 73.20 ± 6.99 | 566.67 ± 163.30 | RA 26.49 | SA 218.54 | ||||

| 2 | Manado Tua | Papindang | 73,63 ± 3.91 | 650 ± 18,95 | RA 16.59 | SA 283.41 | 71,83 | 483,34 |

| Papindang | 70.02 ± 9.61 | 316.67 ± 67.19 | SA 300 | |||||

| 3 | Mantehage | Buhias | 65.48 ± 13.36 | 783.33 ± 39.18 | RA 35.20 | SA 140.67 | 75.82 | 770.83 |

| Tangkasi | 82.99 ± 9.52 | 950 ± 116.37 | RA 15.57 | RM 177.40 | ||||

| Tinongko | 72.62 ± 9.49 | 783.33 ± 215.06 | RA 46.34 | SA 130.24 | ||||

| Tinongko | 82.18 ± 11.09 | 566.67 ± 36.53 | BG 21.83 | SA 163.16 | ||||

| 4 | Nain | Tarente | 68.07 ± 9.59 | 483.33 ± 100.60 | RM 300 | 76.09 | 616.67 | |

| Tarente | 84.11 ± 8.11 | 750 ± 95.76 | RM 14.51 | RA 205.57 | ||||

Figure 4.

Percentage of mangrove tree density.

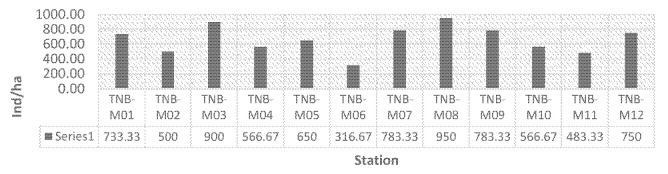

The analysis results concerning the average density of mangrove trees reveal that Mantehage Island exhibited the highest value of 770.83 ind/ha. This was followed by Bunaken, Nain and Manado Tua, with densities of 675 ind/ha, 616.67 ind/ha and 483.34 ind/ha, respectively, as depicted in Table 4. Fig. 5 illustrates the density at each observation station, with TNB-M08 on Mantehage Island recorded the highest value of 950 ind/ha, while the lowest density of 316.67 ind/ha was observed at TNB-M06 on Manado Tua Island. In contrast, Anthoni et al. (2017) reported that the northern mainland of Bunaken National Park displayed the highest density in Tiwoho Village for R. mucronata, with a value of 1,330 ind/ha. On the other hand, the lowest density of 330 ind/ha was found in Bahowo Village for B. gymnorrhiza and R. mucronata. Mangrove density refers to the number of trees per unit area within a specific forest and varies based on factors such as mangrove species, environmental conditions and human activities.

Figure 5.

Mangrove importance value index.

The highest IVI for mangroves on Bunaken Island was observed for S. alba, while R. mucronata had the lowest IVI. On Manado Tua Island, S. alba had the highest IVI, while R. apiculata had the lowest. Mantehage Island possessed the largest mangrove ecosystem area, with the highest IVI attributed to S. alba and the lowest IVI associated with R. apiculata. In contrast, Nain Island displayed the highest IVI for R. apiculata and the lowest IVI for S. alba, as depicted in Table 4. Generally, S. alba exhibited the highest IVI among the small islands. In the northern mainland, A. officinalis had the highest IVI, while R. mucronata had the lowest IVI.

These variations in IVI values may be attributed to environmental factors specific to each study area, such as competition for nutrients, substrate conditions and variations in salinity levels, which can also influence the IVI and diversity index of mangrove species. The composition of the mangrove community is determined by several key factors, including substrate type, tidal conditions and salinity levels. In some cases, light availability and water movement also play important roles (Peng et al. 2016).

The obtained IVI values signify the ecological importance of each species within the ecosystem. In the context of mangroves, species with higher IVI are considered more ecologically and economically valuable. Furthermore, IVI can aid in management and conservation efforts by identifying species that are crucial for the health and productivity of the mangrove ecosystem. For instance, species with high IVI can be prioritised for protection and restoration measures, while those with low IVI may be managed differently.

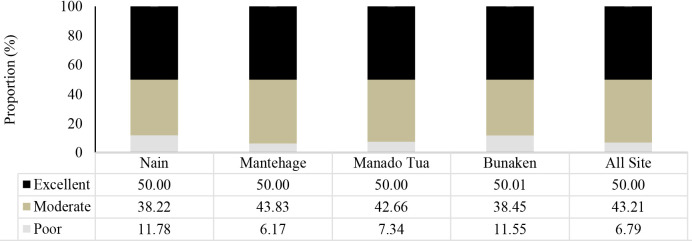

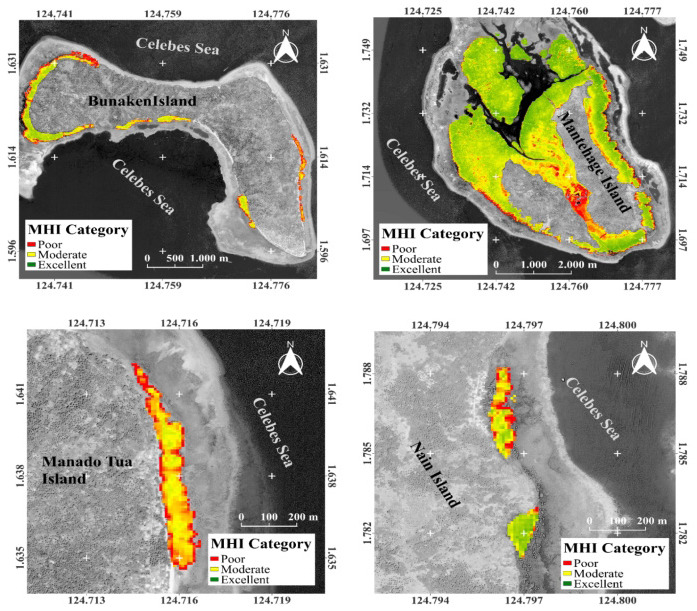

MANGROVE HEALTH INDEX (MHI)

In general, the MHI in the small islands of Bunaken National Park can be classified as good, with an average proportional distribution of 50% excellent, 43% moderate and 6.69% poor, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The proportional range for excellent values was between 50% and 50.01%, for moderate values it was 38.22% to 43.83%, and for poor values, it ranged from 6.17% to 11.78%. The MHI varied among the different islands, with Mantehage Island having the highest value of 71.51, followed by Nain (62.65), Bunaken (58.44) and the lowest value was recorded in Manado Tua at 52.96, as shown in Fig. 7. These values indicate that the mangroves in the small islands were in good condition.

Figure 6.

The proportion of mangrove health index for each island.

Figure 7.

Mangrove health index for each island.

The results of linear regression analysis between remote sensing-based vegetation indices and MHI values indicate that the Mangrove Vegetation Index (MVI) exhibits the highest correlation with a regression coefficient of 0.71, compared to other individual indices, as presented in Table 5. MVI is a rapid and accurate method for identifying mangrove ecosystems using satellite imagery. This index incorporates information on greenness and moisture with 92% accuracy (Baloloy et al. 2020). However, a stronger relationship (R2-adjusted = 0.831) can be achieved by combining the values of the Normalised Burn Ratio (NBR), Green Chlorophyll Index (GCI), Structure Insensitive Pigment Index (SIPI) and Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI). The regression coefficients for the first three vegetation indices were smaller than 0.50, as shown in Table 4. The interpolation values obtained are relatively accurate, as indicated by the root mean square error (RMSE) value of 4.46% or less than 5% (Table 5) (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021). A lower RMSE value indicates that the employed formula is more effective in predicting actual values (Siddiq et al. 2020).

Table 5.

Linear models for predicting MHI value based on remote sensing vegetation indices, regression coefficient Adjusted R2 significance (F) and Accuracy-Test Value (RMSE).

| Vegetation indices (X) | Formula: MHI (Y) = | R2-adjusted | F | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | 84.81*NDVI + 16.709 | 0.631 | 30.068*** | 7.31 |

| MI | −3.488*MI + 97.967 | 0.480 | 16.705** | 10.25 |

| MVI | 28.367*MVI + 75.135 | 0.711 | 42.897*** | 6.46 |

| SAVI | 103.912*SAVI + 31.845 | 0.563 | 22.902*** | 7.95 |

| NBR | 209.780*NBR-79.158 | 0.481 | 16.749** | 12.49 |

| GCI | 2.677*GCI + 45.22 | 0.384 | 11.577** | 9.44 |

| EVI | 7.85*EVI + 41.965 | 0.389 | 11.803** | 9.41 |

| SIPI | −243.007*SIPI + 322.104 | 0.389 | 11.825** | 9.40 |

| ARVI | 65.831*ARVI + 25.264 | 0.665 | 34.810*** | 6.96 |

| NBR, GCI, SIPI, ARVI | 102.12*NBR – 4.64*GCI + 178.15*SIPI + 159.53*ARVI - 252.39 | 0.831 | 21.8987*** | 4.46 |

Notes: NDVI = Normalised Difference Vegetation Index; MI = Mangrove Index; MVI = Mangrove Vegetation Index; SAVI = Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index; NBR = Normalised Burn Ratio; GCI = Green Chlorophyll Index; EVI = Enhanced Vegetation Index; SIPI = Structure Insensitive Pigment Index; ARVI = Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index

The mangrove ecosystem area in the small islands of Bunaken National Park encompassed a total of 748.53 ha. Among these, 374.27 ha were classified as being in excellent condition, 323.47 ha in moderate condition, and 50.79 ha in poor condition. Mantehage Island possessed the largest mangrove ecosystem area, covering 654.84 ha, with 327.42 ha in excellent condition, 286.99 ha in moderate condition, and 4.43 ha in poor condition. Bunaken Island followed with an area of 79.51 ha, comprising 39.76 ha in excellent condition, 30.57 ha in moderate condition, and 9.18 ha in poor condition. Manado Tua Island had an area of 11.04 ha, with 5.52 ha in excellent condition, 4.71 ha in moderate condition, and 0.81 ha in poor condition. Nain Island had the smallest area, measuring 3.14 ha, with 1.57 ha in excellent condition, 1.2 ha in moderate condition, and 0.37 ha in poor condition, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mangrove area and MHI condition in each island.

| Area (ha) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| MHI category | Nain | Mantehage | Manado Tua | Bunaken | All site |

| Poor | 0.37 | 40.43 | 0.81 | 9.18 | 50.79 |

| Moderate | 1.2 | 286.99 | 4.71 | 30.57 | 323.47 |

| Excellent | 1.57 | 327.42 | 5.52 | 39.76 | 374.27 |

|

| |||||

| Total mangrove (ha) | 3.14 | 654.84 | 11.04 | 79.51 | 748.53 |

DISCUSSION

The diversity of mangroves in the small islands of Bunaken National Park is categorised as low due to the presence of only five species in this study. The level of diversity has a significant impact on the carbon absorption capacity of mangroves, with heterogeneous types demonstrating better carbon absorption compared to homogeneous types (Tinh et al. 2020). Dharmawan et al. (2020) observed that oceanic mangroves in small islands of Papua were predominantly dominated by S. alba, while Owi and Wundi Islands in Biak exhibited complete domination (IVI = 300%) due to the presence of a hard substrate type, consisting of sand and coral fragments. Despite their low canopy cover percentage, S. alba competes for space by producing allelopathic compounds that inhibit the growth of other mangrove species (Xin et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2018). This pattern is similar to the mangroves in the northern part of Bunaken National Park, where six species were identified, namely A. officinalis, Avicennia marina (AM), B. gymnorrhiza, R. apiculata, R. mucronata and S. alba (Anthoni et al. 2017). Species distribution models can be utilised to assess the contributions of environmental variables and predict the spatial distribution of mangrove species (Austin et al. 2006; Merow et al. 2013; Rodriguez-Medina et al. 2020; Vessella & Schirone 2013).

Various factors influence the growth and distribution of mangroves, and these factors can be classified into several categories. These include sediment characteristics, physical and chemical attributes of water (such as temperature and salinity), climatic conditions (such as temperature and rainfall), tides, water quality, duration of flooding, coastline width and human activities related to land use (Giri et al. 2008; Forouzannia & Chamani 2022; Long et al. 2022). In addition to these factors, physiological characteristics of plants and other studies have identified 29 environmental variables that are utilised to predict suitable habitats for mangrove forests. These variables are grouped into four categories: bioclimate, terrain, water quality and hydrological conditions (Hu et al. 2020). These variables play a crucial role in determining the ecological conditions required for the establishment and persistence of mangrove ecosystems.

The average canopy cover of mangroves in the small islands of Bunaken National Park was recorded at 73.44%. This differs from the canopy cover observed in the mangroves of the northern mainland of Bunaken National Park. In the northern mainland, the highest canopy cover value was found in Meras Village, measuring 82.78%, while the lowest was recorded in Molas Village, with a value of 61.24%. Despite the variation, both areas can be categorised as having very dense canopy cover (≥ 75%) and being in good condition (Anthoni et al. 2017). Similarly, in comparable communities located on coral islands in Biak Regency, the percentage of canopy cover was approximately 61.32% (Dharmawan & Pramudji 2020). Another study conducted in Ayau Islands reported a relatively high percentage of mangrove canopy cover, ranging from 76.57% to 86.49% (Pribadi et al. 2020). Additionally, mangroves in Middleburg-Miossu Island, covering an area of 16.11 ha, exhibited relatively favourable community conditions. According to the classification outlined in Minister of Environment Regulation No. 201 of the Year 2004, the canopy cover percentage of mangrove communities in this island falls within the dense category (C ≥ 75%), with an average value of 75.82 ± 2.60% (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021).

However, the extent of canopy cover has a significant impact on the condition of mangrove seedlings, as their survival ability diminishes considerably within a canopy cover range of 60%–90% (Jiang et al. 2019). Moreover, Nurdiansah and Dharmawan (2018) discovered a lower percentage of canopy cover (61.02%) in a mangrove community dominated by S. alba compared to communities dominated by Rhizophoraceae in the waters of Tidore and its surrounding areas, this matter pioneer species that thrives at the lower intertidal zone, with stronger wave and softer substratum. Conversely, the Rhizophoraceae mangrove community in the natural area of Wondama Regency exhibited a canopy cover percentage exceeding 75% (Dharmawan & Widyastuti 2017). The percentage of canopy cover directly influences light gaps and intensity, which is a factor that affects mangrove growth and regeneration (Peng et al. 2016). Additionally, tree size plays a vital role in assessing biomass and carbon dynamics, as well as ecosystem-level responses to environmental factors (Piponiot et al. 2022). Larger trees within the forest ecosystem significantly contribute to biomass and carbon stocks (Lindenmayer et al. 2012; Lutz et al. 2012; Ali et al. 2019).

The mean mangrove density in the small islands of Bunaken National Park was recorded as 636 individuals per hectare (ind/ha). Mangrove density serves as a crucial ecological indicator that reflects the overall health and productivity of the ecosystem. In general, mangrove forests with higher density are considered to be in a healthier and more productive state compared to those with lower density. This factor can also have implications for other important ecosystem functions and services, including carbon storage, coastal protection and habitat provision. Mangroves with higher density have the capacity to store more carbon per unit area, offer more effective protection against coastal erosion and storm events, and provide better habitats for a diverse range of marine species (Lindenmayer et al. 2012; Lutz et al. 2012; Ali et al. 2019; Piponiot et al. 2022; Tinh et al. 2020).

In certain instances, exceedingly high mangrove forest density can lead to overcrowding, resulting in resource competition for essentials such as light and nutrients. Consequently, this competition negatively impacts the growth and productivity of individual trees and ultimately leads to a decline in the overall health of the forest (Peng et al. 2016; Jiang et al. 2019).

Fig. 8 depicts the conditions of MHI for each island along with their proportional areas. These findings are consistent with the MHI observed in Molas Village, where the range fell between 48.66% and 69.79%, categorising it as “good.” Similarly, in Biak Numfor Regency, the MHI value was 65%, with a range of 39.3% to 76.8% (Dharmawan, Hadi, et al. 2020; Schaduw et al. 2021). On Middleburg-Miossu Island, less than 5% of mangroves exhibited poor health within the community. Utilising the interpolation method with the established formula, it was determined that the majority (55.73%) of mangroves were in the “moderate” health category, followed by 40.74% (6.56 ha) classified as “very good,” while only 3.53% were deemed to be in “poor” health (Nurdiansah & Dharmawan 2021). The ability of mangroves to attenuate wave energy is primarily influenced by the extent of forest area and the structural composition of the community (Bao 2011; Horstman et al. 2014).

Figure 8.

Interpolated mangrove health index distribution map.

The integration of remote sensing techniques with analysis of mangrove community structure and MHI has facilitated a more comprehensive assessment of mangrove health. The NBR index was employed to analyse the extent of mangrove areas, while the GCI index (Green Chlorophyll Index) was commonly used to estimate the chlorophyll content in leaves of various species, serving as an indicator of physiological and health conditions of the vegetation (Wu et al. 2012). The SIPI (Structure Insensitive Pigment Index) takes into account the ratio of carotenoids to chlorophyll, providing insights into mangrove health (Chaube et al. 2019). Additionally, the ARVI (Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index) exhibited a relatively high regression coefficient with MHI, and its correlation with mangrove carbon reserves in Teluk Benoa Bali was considered reasonably strong (Siddiq et al. 2020).

Tree density, diversity, evenness index and species richness are commonly used indicators for assessing mangrove health. However, these indicators may not provide stable measurements in homogeneous mangrove ecosystems, such as those found on small islands. In recent studies, satellite imagery has been utilised to evaluate the spatial quality of mangroves (Prasetya et al. 2017; Razali et al. 2019; Chougule & Sapkale 2020). The Mangrove Quality Index (MQI) has been developed to assess the overall quality of mangrove ecosystems based on the interrelationships between biotic, abiotic and socio-economic parameters. Nevertheless, the inclusion of complex parameters in the MQI presents challenges and requires significant resources (Faridah-Hanum et al. 2019). The MHI serves as a valuable tool for the conservation and management of mangrove ecosystems, providing a comprehensive assessment of their health status. The MHI can guide decision-making processes by informing the implementation of effective strategies for the protection and restoration of mangrove ecosystems and their associated ecological values.

The mangrove health index analysis method has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Primarily, this method focuses primarily on the physical and structural characteristics of mangrove ecosystems, including tree density, canopy cover and stem diameter. It does not encompass other critical dimensions of mangrove health, such as biodiversity, ecosystem services and ecological processes. Consequently, a comprehensive evaluation of mangrove health necessitates the integration of additional indicators and metrics.

Another limitation pertains to the absence of a standardised protocol for conducting mangrove health index analysis. This lack of standardisation can result in inconsistent and unreliable outcomes across different studies. The absence of uniform guidelines makes it challenging to compare and contrast the health status of diverse mangrove ecosystems. Consequently, efforts to establish a standardised framework for conducting mangrove health index analyses are warranted to enhance the reliability and comparability of findings in future research endeavours.

CONCLUSION

The small islands within Bunaken National Park, namely Mantehage, Bunaken, Nain and Manado Tua, possess distinct mangrove ecosystems. Among these islands, Mantehage Island harbors the largest mangrove ecosystem, whereas Manado Tua Island exhibits the smallest extent. The mangrove community on these islands encompasses five different species, namely A. officinalis, B. gymnorrhiza, R. apiculata, R. mucronata and S. alba. The mangrove density ranged from 483.34 ind/ha to 770 ind/ha, with the average canopy cover falling between 70.04% and 76.09%. Notably, S. alba species demonstrated the highest IVI, while R. apiculata species exhibited the lowest IVI. Overall, the health condition of the mangrove community can be considered relatively good, falling within the moderate category as indicated by the MHI values. Approximately 6.79% of the area displays poor health condition, whereas 50% of the area was classified as being in excellent condition. These findings collectively suggest that the mangrove condition on these islands was generally favourable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Sam Ratulangi University (Unsrat) Institute for Research and Community Service Unsrat (LPPM) 1681/UN12.13/PM/2023, The Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of Indonesia, National Research and Innovation Agency, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Unsrat, Bunaken National Park, and North Sulawesi Provincial Government, as well as all parties involved in this data for the assistance and cooperation provided.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS: Joshian Nicolas William Schaduw: Analysed the data and prepared the first article, designed the study.

Trina Ekawati Tallei: Responsible for finalising the article for publication, contributed to to the writing of the article draft as well as edited the final manuscript.

Deiske A Sumilat: Analyse the data and continued the article draft.

All authors contributed to this article and approved of the submitted version.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available on request.

REFERENCES

- Alexander LV. Global observed long-term changes in temperature and precipitation extremes: A review of progress and limitations in IPCC assessments and beyond. Weather and Climate Extremes. 2016;11:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.wace.2015.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Lin SL, He JK, Kong FM, Yu JH, Jiang HS. Big-sized trees overrule remaining trees’ attributes and species richness as determinants of aboveground biomass in tropical forests. Global Change Biology. 2019;25(8):2810–2824. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi DM, Trott LA, Wattayakorn G, Clough F. Below-ground nitrogen cycling in relation to net canopy production in mangrove forests of Southern Thailand. Marine Biology. 2002;140:855–864. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0757-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MC. Studies of the wood-land light climate I. The photographic computation of light condition. Journal of Ecology. 1964;52:27–41. doi: 10.2307/2257780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anthoni A, Schaduw JNW, Sondakh C. Persentase tutupan dan struktur komunitas mangrove di sepanjang pesisir Taman Nasional Bunaken bagian utara. Marine Environmental Research. 2017;2(1):13–21. doi: 10.35800/jplt.5.3.2017.16909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MP, Belbin L, Meyers JA, Doherty MD, Luoto M. Evaluation of statistical models used for predicting plant species distributions: Role of artificial data and theory. Ecological Modelling. 2006;199:197–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao TQ. Effect of mangrove forest structures on wave attenuation in coastal Vietnam. Oceanologia. 2011;53(3):807–818. doi: 10.5697/oc.53-3.807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baloloy AB, Blanco AC, Ana RRCS, Nadaoka K. Development and application of a new mangrove vegetation index (MVI) for rapid and accurate mangrove mapping. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2020;166:95–117. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier EB, Koch EW, Hacker SD, Wolanski E, Primavera J, Granek EF, et al. Coastal ecosystem-based management with nonlinear ecological functions and values. Science. 2008;319(5861):321–323. doi: 10.1126/science.1150349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck MW, Brumbaugh RD, Airoldi L, Carranza A, Coen LD, Crawford C, Defeo O, Edgar GJ, Hancock B, Kay MC, et al. Oyster reefs at risk and recommendations for conservation, restoration, and management. Bioscience. 2011;61:107–116. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brent BH, Matthew DL, Monique CF, Aaron BC, Francisco PC, Mary GG. Climate mediates hypoxic stress on fish diversity and nursery function at the land-sea interface. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 2015;112(26):8025–8030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505815112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugati L, Gatto B, Rastelli E, Martire ML, Coral C, Greco S, Danovaro R. Impact of mangrove forests degradation on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaube NR, Lele N, Misra A, Murthy TVR, Manna S, Hazra S, Panda M, Samal RN. Mangrove species discrimination and health assessment using AVIRIS-NG hyperspectral data. Current Science. 2019;116:1136–1142. doi: 10.18520/cs/v116/i7/1136-1142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chougule VA, Sapkale JB. Detecting changes and health status of mangrove forest in Achara estuary, Maraharashtra using remote sensing and GIS. Sustainability Agri Food Environmental Research (SAFER) 2020;8(3):212–221. doi: 10.7770/safer-V0N0-art2093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawan IWE, Widyastuti A. Pristine mangrove community in Wondama gulf, West Papua, Indonesia. Journal of Marine Research. 2017;42(2):73–82. doi: 10.14203/mri.v42i2.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawan IWE, Pramudji Mangrove community structure in Papuan Small Islands, Case study in Biak Regency. Proceeding The IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Purwokerto, Indonesia. 21–23 August 2019; 2020. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawan IWE, Suyarso, Ulumuddin YI, Prayudha B, Pramudji . Manual for mangrove community structure monitoring and research in Indonesia. Makassar, Indonesia: NAS Media Pustaka; 2020a. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawan IWE, Hadi TA, Arbi UY, Makatipu PC, Rahmawati S, Budiyanto A, Sitepu AB, Usman B, Halang P, Kapitaraw Y, Sulaksmana A, Dan FCE, Otoluwa B. Monitoring kesehatan terumbu karang dan ekosistem terkait di Kabupaten Biak-Numfor. Jakarta: COREMAP CTI, LIPI; 2020b. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte CM, Losada IJ, Hendriks IE, Mazarrasa I, Marba N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:961–968. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Xie M, Wang Y, Chen Z, Liu W, Liao J, Chen B. Connectivity of fish assemblages along the mangrove-seagrass-coral reef continuum in Wenchang, China. Acta Oceanologica Sinica. 2020;39(8):43–52. doi: 10.1007/s13131-019-1490-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elith J, Leathwick JR. Species distribution models: Ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2009;40:677–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faridah-Hanum I, Yusoff FM, Fitrianto A, Ainuddin NA, Gandaseca S, Zaiton S, Norizah K, Nurhidayu S, Roslan MK, Hakeem KR, Shamsuddin I. Development of a comprehensive mangrove quality index (MQI) in Matang Mangrove: Assessing mangrove ecosystem health. Ecological Indicators. 2019;102:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friess DA. Mangrove forests. Current Biology. 2016a;26:R739–R755. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friess DA. Ecosystem services and disservices of mangrove forests: Insights from historical colonial observations. Forests. 2016b;7:183. doi: 10.3390/f7090183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzannia M, Chamani A. Mangrove habitat suitability modeling: Implications for multi-species plantation in an arid estuarine environment. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2022;194:552. doi: 10.1007/s10661-022-10194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri C, Zhu Z, Tieszen LL, Singh A, Gillette S, Kelmelis JA. Mangrove forest distributions and dynamics (1975–2005) of the tsunami-affected region of Asia. Journal of Biogeography. 2008;35:519–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01806.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen W, Wulffraat S, Zieren M, Scholten L. Mangrove guidebook for Southeast Asia. Bangkok: FAO and Wetlands International; 2006. https://www.fao.org/3/ag132e/ag132e.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Grant PR, Grant BR, Huey RB, Johnson MTJ, Knoll AH, Schmitt J. Evolution caused by extreme events. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2017;372(1723):20160146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim NR, Hughes F. The responses of secondary forest tree seedlings to soil enrichment in Peninsular Malaysia: An experimental approach. Tropical Ecology. 2010;51(2):173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Wang Y, Dong P, Zhang D, Yu W, Ma Z, Chen G, Liu Z, Du J, Chen B, Lei G. Predicting potential mangrove distributions at the global northern distribution margin using an ecological niche model: Determining conservation and reforestation involvement. Forest Ecology and Management. 2020;478:118517. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst TA, Pope AJ, Quinn GP. Exposure mediates transitions between bare and vegetated states in temperate mangrove ecosystems. Marine Ecology Progress Series (MEPS) 2015;533:121–134. doi: 10.3354/meps11364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husain P, Idrus AA, Ihsan MS. The ecosystem services of mangroves for sustainable coastal area and marine fauna in Lombok, Indonesia: A review. Jurnal Inovasi Pendidikan Sains. 2020;1(1):1–7. doi: 10.51673/jips.v1i1.223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmer M, Olsen AB. Role of decomposition of mangrove and seagrass detritus in sediment carbon and nitrogen cycling in a tropical mangrove forest. Marine Ecology Progress Series (MEPS) 2002;230:87–101. doi: 10.3354/meps230087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman EM, Dohmen-Janssen CM, Narra PMF, Van den Berg NJF, Siemerink M, Hulscher SJ. Wave attenuation in mangroves: A quantitative approach to field observations. Coastal Engineering. 2014;94:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2014.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilman M, Dargusch P, Dart P. A historical analysis of the drivers of loss and degradation of Indonesia’s mangroves. Land Use Policy. 2016;54:448–459. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insani WON, Widayati W, Sawaludin S. Analisis degradasi hutan mangrove di Kecamatan Kaledupa Kabupaten Wakatobi. JAGAT (Jurnal Geografi Aplikasi Dan Teknologi) 2020;4(1):15–24. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3871258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida M. Automatic thresholding for digital hemispherical photography. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 2004;34:2208–2216. doi: 10.1139/x04-103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenning SB, Brown ND, Sheil D. Assessing forest canopies and understorey illumination: Canopy closure, canopy closure and other measures. Forestry. 1999;72(1):59–74. doi: 10.1093/forestry/72.1.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Guan W, Xiong Y, Li M, Chen Y, Liao B. Interactive effects of intertidal elevation and light level on early growth of five mangrove species under Sonneratia apetala Buch. Hamplantation canopy: Turning monocultures to mixed forests. Forests. 2019;10(2):83–97. doi: 10.3390/f10020083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Anwar C, Chaniago A, Baba S. Handbook of mangroves in Indonesia. Denpasar, Indonesia: Saritaksu; 1999. https://onesearch.id/Record/IOS3812.slims-464 . [Google Scholar]

- Kusmana C, Dwiyanti FG, Malik Z. Comparison of several methods of stands inventory prior to logging towards the yield volume of mangrove forest in Bintuni Bay, West Papua Province, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity. 2020;21(4):1438–1447. doi: 10.13057/biodiv/d210423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen L, Korhonen KT, Rautiainen M, Stenberg P. Estimation of forest canopy cover: A comparison of field measurement techniques. Silva Fennica. 2006;40(4):577–588. doi: 10.14214/sf.315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Hamilton S, Barbier EB, Primavera J, Lewis RR., III Better restoration policies are needed to conserve mangrove ecosystems. Nature Ecology and Evolution. 2019;3:870–872. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0861-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer DB, Laurance WF, Franklin JF. Global decline in large old trees. Science. 2012;338(6112):1305–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.1231070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo AE, Snedaker SC. The ecology of mangroves. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 1974;5:39–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.000351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz JA, Larson AJ, Swanson ME, Freund JA, Bond-Lamberty B. Ecological importance of large-diameter trees in a temperate mixed-conifer forest. PloS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C, Dai Z, Wang R, Lou Y, Zhou X, Li S, Nie Y. Dynamic changes in mangroves of the largest delta in northern Beibu Gulf, China: Reasons and causes. Forest Ecology and Management. 2022;504:119855. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh DJ. Final report of the integrated multidisciplinary survey and research programme of the Ranong mangrove ecosystem. Thailand: National Mangrove Committee of the National Research Council of Thailand; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Almahasheer H, Duarte C. Mangrove forests as traps for marine litter. Environmental Pollution. 2019;247:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merow C, Smith MJ, Silander JA., Jr A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species’ distributions: What it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography. 2013;36:1058–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.07872.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhsoni FF, Sambah AB, Mahmudi M, Wiadnya DGR. Comparison of different vegetation indices for assessing mangrove density using sentinel-2 imagery. International Journal of GEOMATE. 2018;14:42–51. doi: 10.21660/2018.45.7177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan S, Beck MW, Reguero BG, Losada IJ, Van Wesenbeeck B, Pontee N, Sanchirico JN, Ingram JC, Lange GM, Burks-Copes KA. The effectiveness, costs and coastal protection benefits of natural and nature-based defences. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho TS, Fahrudin A, Yulianda F, Bengen DG. Structure and composition of riverine and fringe mangroves at Muara Kubu protected areas, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation and Legislation. 2019;12(1):378–393. https://www.bioflux.com.ro/docs/2019.378-393.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Nurdiansah D, Dharmawan IWE. Komunitas mangrove di wilayah pesisir Pulau Tidore dan sekitarnya. Oseanologi dan Limnologi di Indonesia. 2018;3(1):1–9. doi: 10.14203/oldi.2018.v3i1.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nurdiansah D, Dharmawan IWE. Community structure and healthiness of mangrove in Middleburg-Miossu Island, West Papua. Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan Tropis. 2021;13(1):81–96. doi: 10.29244/jitkt.v13i1.34484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noor YR, Khazali M, Suryadiputra INN. Panduan pengenalan mangrove di Indonesia. Bogor: PHKA/Wi-IP; 1999. https://indonesia.wetlands.org/id/publikasi/panduan-pengenalan-mangrove-di-indonesia . [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Diao J, Zheng M, Guan D, Zhang R, Chen G, Lee SY. Early growth adaptability of four mangrove species under the canopy of an introduced mangrove plantation: Implications for restoration. Forest Ecology and Management. 2016;373:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piponiot C, Anderson-Teixeira KJ, Davies SJ, Allen D, Bourg NA, Burslem DFRP, C’ardenas D, Chang-Yang C–H, Chuyong G, Cordell S, et al. Distribution of biomass dynamics in relation to tree size in forests across the world. New Phytologist. 2022;234(5):1664–1677. doi: 10.1111/nph.17995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasetya JD, Ambariyanto, Supriharyono, Purwanti F. Mangrove health index as part of sustainable management in mangrove ecosystem at Karimunjawa National Marine Park Indonesia. Advanced Science Letters. 2017;23(4):3277–3282. doi: 10.1166/asl.2017.9155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pribadi R, Dharmawan IWE, Bahari AK. Penilaian kondisi kesehatan ekosistem mangrove di Ayau dan Ayau Kepulauan, Kabupaten Raja Ampat. Majalah Ilmiah Biologi Biosfera. 2020;37(2):106–111. doi: 10.20884/1.mib.2020.37.2.1206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto AD, Ardli ER. Development of a simple method for detecting mangrove using free open source software. Jurnal Segara. 2020;16(2):71–82. doi: 10.15578/segara.v16i2.7512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahadian A, Prasetyo LB, Setiawan Y, Wikantika K. A historical review of data and information of Indonesian mangroves area. Media Konservasi. 2019;24(2):163– 178. doi: 10.29244/medkon.24.2.163-178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Razali SM, Nuruddin AA, Lion M. Mangrove vegetation health assessment based on remote sensing indices for Tanjung Piai, Malay Peninsular. Journal of Landscape Ecology. 2019;12(2):26–40. doi: 10.2478/jlecol-2019-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DR, Friess DA. Rates and drivers of mangrove deforestation in Southeast Asia, 2000–2012. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(2):344–349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510272113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Medina K, Yanez-Arenas C, Peterson AT, Euan Avila J, Herrera-Silveira J. Evaluating the capacity of species distribution modeling to predict the geographic distribution of the mangrove community in Mexico. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanach S, Deangelis D, Hock LK, Li Y, Su YT, Sulaiman R, Zhai L. Conservation and restoration of mangroves: Global status, perspectives, and prognosis. Ocean and Coastal Management. 2018;154:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaduw JNW, Kondoy KIF, Manoppo VEN, Luasunaung A, Mudeng J, Pelle WE, Ngangi ELA, Manembu IS, Wantasen NS, Sumilat DA, et al. Data on percentage coral reef cover in small islands Bunaken National Park. Data in Brief. 2020;31:105713. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaduw JNW, Kondoy KFI. Seagrass percent cover in small islands of Bunaken National Park, North Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. AACL Bioflux. 2020;13(2):951–957. [Google Scholar]

- Schaduw JNW, Bachmid F, Paat GR, Elisa ML, Devira, Maleke C, Upara U, Henry EL, Mamesah J, Azis TA, et al. Mangrove Health Index and carbon potential of mangrove vegetation in marine tourism area of Nusantara Dian Center, Molas Village, Bunaken District, North Sulawesi Province. SPATIAL. 2021;21(2):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shan Q, Ling H, Zhao H, Li M, Wang Z, Zhang G. Do extreme climate events cause the degradation of Malus sieversii forests in China? Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021;12:608211. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.608211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiq A, Dimyati M, Damayanti A. Analysis of carbon stock distribution of mangrove forests in the coastal city of Benoa, Bali with combination vegetation index, and statistics approach. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology. 2020;10(6):2386–2393. doi: 10.18517/ijaseit.10.6.12991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinh HP, Hanh NTH, Thanh VV, Tuan MS, Quang PV, Sharma SP, MacKenzie RA. A comparison of soil carbon stocks of intact and restored mangrove forests in northern Vietnam. Forests. 2020;11(6):660–669. doi: 10.3390/f11060660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson PB. The botany of mangroves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson PB. The botany of mangroves. 2nd Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vessella F, Schirone B. Predicting potential distribution of Quercus suber in Italy based on ecological niche models: Conservation insights and reforestation involvements. Forest Ecology and Management. 2013;304:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Niu Z, Gao S. The potential of the satellite-derived green chlorophyll index for estimating midday light use efficiency in maize, coniferous forest and grassland. Ecological Indicators. 2012;14(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin K, Zhou Q, Arndt SK, Yang X. Invasive capacity of the mangrove Sonneratia apetala in Hainan Island, China. Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 2013;25(1):70–78. https://www.frim.gov.my/v1/JTFSOnline/jtfs/v25n1/70-78.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liang FP, Li YYW, Zhang JW, Zhang SJ, Bai H, Liu Q, Zhong CYR, Li L. Allelopathic effects of leachates from two alien mangrove species, Sonneratia apetala and Laguncularia racemosa on seed germination, seedling growth and antioxidative activity of a native mangrove species Sonneratia caseolaris. Allelopathy Journal. 2018;44(1):119–130. doi: 10.26651/allelo.j/2018-44-1-1158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.