Abstract

Objective.

LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses minority stress to improve sexual minority individuals’ mental and behavioral health. This treatment has never been tested in high-stigma contexts like China using online delivery.

Method.

Chinese young sexual minority men (n=120; ages 16–30; HIV-negative; reporting depression and/or anxiety symptoms and past-90-day HIV-transmission-risk behavior), were randomized to receive 10 sessions of culturally adapted asynchronous LGBTQ-affirmative internet-based CBT (ICBT) or weekly assessments only. The primary outcome included HIV-transmission-risk behavior (i.e., past-30-day condomless anal sex). Secondary outcomes included HIV social-cognitive mechanisms (e.g., condom use self-efficacy), mental health (e.g., depression), and behavioral health (e.g., alcohol use), as well as minority stress (e.g., acceptance concerns), and universal (e.g., emotion regulation) mechanisms at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up. Moderation analyses examined treatment efficacy as a function of baseline stigma experiences and session completion.

Results.

Compared to assessment only, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT did not yield greater reductions in HIV-transmission-risk behavior or social-cognitive mechanisms. However, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT yielded greater improvements in depression (d=−0.50, d=−0.63) and anxiety (d=−0.51, d=−0.49) at 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively; alcohol use (d=−0.40) at 8-month follow-up; and certain minority stress (e.g., internalized stigma) and universal (i.e., emotion dysregulation) mechanisms compared to assessment only. LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT was more efficacious for reducing HIV-transmission-risk behavior for participants with lower internalized stigma (d=0.42). Greater session completion predicted greater reductions in suicidality and rumination.

Conclusions.

LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT demonstrates preliminary efficacy for Chinese young sexual minority men. Findings can inform future interventions for young sexual minority men in contexts with limited affirmative supports.

Keywords: sexual and gender minorities, HIV, minority health, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), syndemic

Stigma and minority stress exacerbate the disproportionate risk of poor mental and behavioral health facing sexual minority men around the world, including co-occurring risk of depression, anxiety, substance use problems, and HIV-transmission risk (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016; Operario et al., 2022). China, the world’s most populous country, is no exception. Increasing evidence suggests that Chinese sexual minority men are at high risk of mental and behavioral health challenges (Sun, Pachankis, et al., 2020), with a high estimated prevalence of depression (43.2%), anxiety (32.2%), lifetime suicidal ideation (24%), and lifetime recreational drug use (77.3%), respectively (Wei et al., 2020; P. Zhao et al., 2016). These psychological burdens also help fuel HIV transmission (Stall et al., 2007), presenting an increasing public health challenge in China. According to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual minority men are the highest-risk group for HIV acquisition, and the proportion of HIV infection attributable to same-sex transmission has increased from 9.1% in 2009 to 23.3% in 2020 (He, 2021). Young adult (e.g., age 16–30) sexually active sexual minority men represent the most at-risk population for HIV infection in China today (Li et al., 2019; Wu, 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). Moreover, HIV transmission due to same-sex contact is likely to be underestimated given the normative lack of sexual minority disclosure in China (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019). At current trends, an estimated one in six Chinese sexual minority men will be infected with HIV by 2025 (Lou et al., 2018).

Minority stress theory suggests that environments characterized by normative stigma and identity invalidation drive psychosocial adaptations among sexual minority individuals that can ultimately erode their mental and behavioral health (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). These adaptations include psychosocial processes such as identity concealment, internalized stigma, and rejection hypervigilance (Hollinsaid et al., 2022; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis, Mahon, et al., 2020). Although these responses are initially learned through ongoing exposure to invalidating environments (Cardona et al., 2021), they can become chronic, ingrained coping tendencies that manifest in insalubrious outcomes, such as emotional and behavioral avoidance (e.g., rumination; hazardous alcohol use; Lewis et al., 2016; Szymanski et al., 2014) and the experience of maladaptive emotional processes (e.g., lack of emotion awareness) that predict the development of depression and anxiety (Pachankis, Rendina, et al., 2015).

The social environment in China can be characterized as a collectivistic culture with an emphasis on conforming to social norms and traditional family values including heterosexual marriage and procreation (Sun, Budge, et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021). Indeed, the tenets of minority stress theory have been supported among samples of Chinese sexual minority individuals, with notable exceptions. Structural stigma toward Chinese sexual minority men includes a lack of legal protections for same-sex marriage, inclusive sex education, or recourse to discrimination (Joint United Nations Development Programme, 2018; Miles-Johnson & Wang, 2018). Under this cultural background and with the introduction of early western psychiatry which characterized same-sex attraction as a form of psychopathology, sexual orientation conversion therapy is still being provided in formal settings across China (Burki, 2017; Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, the Chinese traditional value of ‘filial piety’, based on Confucian philosophy, emphasizes the importance of marriage and passing on one’s family lineage (Steward et al., 2013; Sun, Budge, et al., 2020). China’s collectivistic cultural norms might therefore exacerbate pressures emerging from one’s own family and community to conceal one’s sexual identity (Steward et al., 2013; Sun, Budge, et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021). For this reason, interpersonal minority stress reactions, most notably concerns about social acceptance, appear to be the most strongly related to both minority stress exposures (e.g., lack of family support) and poor mental health among Chinese sexual minority individuals (Sun, Budge, et al., 2020; Sun, Pachankis, et al., 2020), even more so than identity concealment. The consistent lack of association between identity concealment and poor mental health observed for Chinese sexual minority individuals (Sun et al., 2021) could perhaps be explained by the normative collectivistic values in Chinese culture (Steward et al., 2013) and the greater benefits than costs of concealment in high-stigma contexts (Pachankis, Mahon, et al., 2020). On the other hand, internalized stigma is significantly associated with poor mental health among Chinese sexual minority individuals (Su et al., 2018; W. Xu et al., 2017), like in the Western contexts in which these associations have been most often studied (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010).

LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) represents the only evidence-based intervention that seeks to address the hypothesized minority stress source of sexual minority men’s co-occurring mental and behavioral health risks (Pachankis, Harkness, Jackson, et al., 2022). Informed by minority stress theory (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003), LGBTQ-affirmative CBT seeks to instill coping skills against minority stress by addressing the cognitive (e.g., negative self-schemas), affective (e.g., emotion dysregulation), and behavioral (e.g., avoidance) pathways through which minority stress drives adverse mental and behavioral health outcomes. For example, LGBTQ-affirmative CBT modules raise awareness of the personal impact of minority stress and teaches cognitive flexibility for undoing negative self-schemas; other modules provide mindfulness and behavioral exposure exercises countering maladaptive avoidance tendencies (e.g., sexual health communication, social engagement, identity disclosure in safe contexts; Pachankis, Soulliard, et al., 2022). Several previous trials of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT, conducted in North America, have shown efficacy in improving psychosocial outcomes ranging from depressive and anxiety symptoms, alcohol use problems, and HIV-transmission-risk behavior compared to waitlist control conditions (Craig, Eaton, et al., 2021a; Craig, Leung, et al., 2021; Pachankis, McConocha, et al., 2020). When compared to active treatments (i.e., community-based affirmative counseling, HIV testing and counseling), LGBTQ-affirmative CBT shows smaller effects, but nonetheless statistically significant improvements for co-occurring mental and behavioral health outcomes (Pachankis, Harkness, Maciejewski, et al., 2022). Outcome data for cultural adaptations of the treatment, for instance for Black and Latinx gay and bisexual men in the US (Jackson et al., 2022) and sexual minority men living in China (Pan et al., 2021), also support the promise and transferability of this treatment.

Although emerging evidence has shown LGBTQ-affirmative CBT to be a promising intervention for addressing the downstream consequences of minority stress on sexual minority individuals’ co-occurring psychosocial health problems, it has typically been delivered by therapists one-on-one or in small group settings, thereby challenging its widespread implementation (Pachankis, Harkness, Jackson, et al., 2022). Implementation is further hindered by high-stigma, low-access resource contexts such as those in China, which often lack LGBTQ-affirmative providers and mental health providers in general, have geographically dispersed LGBTQ communities, and instill normative fears of accessing LGBTQ-specific spaces (Pan et al., 2020; X. Xu et al., 2017). Given these circumstances, emerging research documents the advantages of online approaches for addressing sexual minority individuals’ psychosocial health needs (Craig, Iacono, et al., 2021).

Guided internet-based CBT (ICBT) refers to any structured, goal-oriented CBT delivered through an online platform containing treatment materials, assessment instruments, and technological capacity for facilitating asynchronous interactions with therapists who can review clients’ written exercises and provide technical and psychological support (Almlöv et al., 2011; Andersson et al., 2016). The efficacy of ICBT shows equivalence with face-to-face CBT while also overcoming several of the implementation challenges of traditional CBT delivery modalities (Andersson et al., 2014; Andersson et al., 2019; Andrews et al., 2018). Furthermore, with the rapid development of information technology, internet coverage now reaches 76.4% of citizens in China, and 99.8% have access via mobile phone (China Internet Network Information, 2023). For these reasons, ICBT seems promising as a treatment approach for sexual minority individuals living in China and other contexts of high stigma and few identity-affirming resources. In further support of this possibility, although a recent randomized controlled trial with sexual minority young adults across the US found small, non-significant effects for LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to an assessment-only control, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT’s comparative effects were larger and statistically significant for participants living in US locales with high degrees of normative anti-LGBTQ bias (Pachankis et al., 2023).

Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that stigma can enhance or undermine intervention efficacy for stigmatized populations, depending on the level at which stigma is measured (e.g., internalized vs. structural) and whether or not the intervention is adapted to address the distinct concerns of the stigmatized population (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2021). For instance, adapted mental and behavioral health interventions for stigmatized populations have been found to be most efficacious for individuals experiencing the highest degrees of internalized and interpersonal stigma (e.g., Lee et al., 2019; Millar et al., 2016; Pachankis, Williams, et al., 2020). Conversely, non-adapted interventions delivered to stigmatized populations are less effective in contexts of high, compared to low, structural stigma (Price et al., 2021; Reid et al., 2014); however, when interventions are adapted to address the distinct needs of the stigmatized, some emerging evidence suggests an opposite effect – under conditions of high structural stigma, these adapted interventions are actually more efficacious than under conditions of low structural stigma (Pachankis et al., 2023). Not only does LGBTQ-affirmative CBT represent an adaptation to standard CBT informed by minority stress theory, but LGBTQ-affirmative CBT has been even further adapted through a multistage adaptation process to address manifestations of minority stress for sexual minority men living in China (Pan et al., 2021). This research lays the groundwork for LGBTQ-affirmative CBT, as adapted for Chinese sexual minority men, to be tested using the efficient ICBT delivery platform particularly suited to this context.

The present study used a randomized control trial to assess the efficacy of the Chinese culturally adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to an assessment-only condition at 4- and 8-month post-baseline. Based on the above evidence including the normative structural stigma in China, we expected LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT to show stronger efficacy across outcomes as compared to the relatively weak effect sizes when this treatment was tested in the US (Pachankis et al., 2023). At the same time, consistent with past research showing that adapted treatments have stronger effects for individuals with higher degrees of internalized stigma (e.g., Millar et al., 2016), we expected LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT to be even more efficacious for participants with higher levels of internalized stigma at baseline.

Method

Study design

This study employed a parallel randomized controlled trial with a 1:1 ratio allocation to two conditions (LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT vs. assessment only). The trial protocol was pre-registered on ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT04718194).

Setting

This study was carried out online in Hunan Province, which is a medium-developing province in China with a population of 66,040,000 in 2022 (People’s Government of Hunan Province, 2023). By the end of October 2022, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS in Hunan Province was approximately 53,030, with 5,463 new infections from January to October 2022 of which 17% were attributed to sexual minority men (Hunan Provincial Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 2022). As noted above, sexually active young sexual minority men represent the highest-transmission risk group in China today (Li et al., 2019; Wu, 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). Consequently, this study enrolled young sexual minority men and assessed HIV-transmission-risk behavior alongside other co-occurring mental and behavioral health outcomes disproportionately affecting this population.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) 16–30 years old, since LGBTQ-affirmative therapy was originally developed for this age of group (Pachankis, 2015), and because the minimum age of consent to HIV testing is 16 in China; (2) self-identified male gender; (3) living in Hunan province China; (4) reporting having sex with men in the previous 12 months; (5) reporting having condomless anal sex in the previous 3 months; (6) confirmed HIV-negative status upon at-home testing; (7) reporting past-week symptoms of depression or anxiety (Brief Symptom Inventory-4 score > 2.5 on either the depression subscale, anxiety subscale, or both; Lang et al., 2009); (8) reporting no past-3-month mental health services (i.e., no more than 2 visits/month); (9) reporting having weekly access to the internet on a laptop, desktop, or tablet device; and (10) having ability to read, write, and speak in Mandarin. Exclusion criteria included: (1) current active suicidality or homicidality (defined as active intent or concrete plan, as opposed to passive ideation); (2) evidence of active and untreated mania or psychosis that could interfere with the participant’s ability to volitionally consent to research or interfere with their ability to complete the study safely and reliably.

Recruitment

Recruitment started in September 2021 and ended in March 2022, and the last data were collected in November 2022. We recruited participants via social networking platforms catering to young sexual minority men (e.g., WeChat, Blued) and via paper advertisements (e.g., posters) posted in the lobbies of an LGBTQ-friendly community-based organization called Zuo An Cai Hong, which has seven offices in seven cities of Hunan province and provides over 11,000 HIV tests per year and offers free counseling to sexual minority men. This organization has a strong collaboration with the local Center of Disease Prevention and Control. Snowball sampling was also used to recruit participants.

Screening procedure

The CONSORT diagram in Figure 1 provides an overview of the study flow and structure. Potential participants scanned a QR code through WeChat on the flyer that linked to an online screener on the Sojump survey platform (similar to Qualtrics). Preliminarily eligible participants were further confirmed by phone screen, where review of the study procedures and consent also took place. Upon confirming eligibility and providing consent, participants were sent a self-testing kit for HIV and syphilis.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through study procedures

Upon receiving the kit, participants scheduled a phone appointment with a study counselor for voluntary counseling and testing (VCT). Study VCT counselors, who also served as ICBT counselors, were trained in VCT by the second and last author and staff from the LGBTQ-friendly organization described above (Zuo An Cai Hong), which has an 11-year history of providing identity-affirming, sex-positive VCT to sexual minority men. Participants who preferred not to receive the self-testing kit by mail could pick up the kit from one of the seven offices of Zuo An Cai Hong. We based our self-testing VCT protocols on US Centers for Disease Control (Hurt & Powers, 2014) and World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2016) guidelines. VCT counselors conducted pre-test counseling for all participants and post-test counseling for positive or inconclusive results, with linkage to care to Zuo An Cai Hong for confirmatory testing, care, and treatment. Only participants who received an HIV-negative test result were eligible for this study. Eligible participants uploaded their test results onto a secure study platform. These practices have been used and validated previously (Grov et al., 2016).

A call was scheduled with eligible participants to review and sign the consent form. The participants who signed the electronic consent form via Sojump were assigned a username and password for the secure ICBT BASS platform, which has been used in previous ICBT studies for various populations and outcomes (e.g., Bjureberg et al., 2022; Ljótsson et al., 2014). Only participants who completed the baseline assessment on the platform were randomized.

Randomization and masking

An apriori power analysis indicated that a sample size of 120 participants (60 per condition) with approximately 20% attrition would provide ≥ 80% power to detect a difference (p < .05) between the conditions of d = .40. A random number table was generated using SPSS 26.0 to randomly assign participants to intervention or control conditions using a 1:1 ratio with block size of two. Prior to the baseline surveys, the random number table was sealed in sequentially numbered and opaque envelopes. Once an eligible participant completed the consent form and the baseline survey, a research assistant opened the envelope and informed the participant of their assigned condition. Neither participants nor counselors were masked to condition assignment given the nature of the treatment.

Interventions

Assessment Only (Control).

Participants in the control condition completed a weekly self-monitoring survey for 10 weeks, which they were required to complete within a 4-month period; the mean interval between surveys was approximately 1.6 weeks. This type of self-monitoring has been shown to produce reductions in depression symptoms over time and yield improvement in behavioral health outcomes (Kauer et al., 2012; Livingston et al., 2017). These weekly assessments of participants’ past-7-day mental and behavioral health and minority stress experiences were collected via the ICBT platform using the following scales: (1) depression symptoms using the 5-item Overall Depression Severity & Impairment Scale (Bentley et al., 2014); (2) anxiety symptoms using the 5-item Overall Anxiety Severity & Impairment Scale (Norman et al., 2006); (3) HIV-transmission-risk behavior (i.e., “Did you have any sexual activity with another person in the past week that could have put you at risk for sexually transmitted infections?”), and (4) minority stress experiences using 13 items adapted from previous studies (e.g., “How worried or anxious have you been about being rejected because you are LGBTQ+?”; Eldahan et al., 2016; Heron et al., 2018).

LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT.

In addition to completing the 10 weekly assessments described above, participants in the intervention condition received LGBTQ-affirmative CBT as previously adapted for Chinese sexual minority men (Pan et al., 2021) and uploaded for this study onto the ICBT platform (BASS, as described above). To create LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT from the Chinese culturally adapted version of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT, the Chinese-adapted materials (e.g., manual, handouts) were transformed into ICBT content (e.g., self-guided exercises, videos, counselor instructions). This in-person-to-online transformation involved the following five steps: (1) We created the online psychoeducational content of the 10 modules based on the content of the in-person manual and handouts of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT (Pachankis, Harkness, Jackson, et al., 2022) and its Chinese cultural adaptation (Pan et al., 2021). Each ICBT module contained 4–5 online pages of engaging psychoeducational content (e.g., “the emotional costs of stigma and stress”) and accompanying exercises (e.g., “how my feelings shape my actions”) and homework (e.g., “asserting myself”); (2) For each ICBT module, we created a 2–5 minute video to illustrate the more complex ICBT components (e.g., identifying core beliefs; designing an effective behavioral experiment); (3) We uploaded all intervention content and assessments onto the ICBT platform with technical support from the developer of the ICBT technical platform; (4) 10 sexual minority men pilot-tested the 10 Chinese culturally adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT modules. Following completion of the 10 modules, the 10 participants gave feedback in an interview with study staff about the modules, exercises, homework, and videos; (5) Based on feedback from these interviews, we made revisions to ensure the comprehension, appropriateness, and acceptability of the text and videos (e.g., added culturally animated depictions to elucidate the subgoals encompassed within each module; added two videos acted by two study counselors, i.e., coming out to one’s parents after being urged to get married and negotiating condom use with one’s partner, as examples of behavioral experiments; replaced all images with Chinese cultural references and faces). The resulting Chinese culturally adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT contained 10 modules: (1) introduction to culturally adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT and goal setting; (2) monitoring LGBTQ-related stress and emotions; (3) understanding emotions; (4) awareness of LGBTQ-related stress reactions; (5) automatic thoughts; (6) understanding emotion avoidance; (7) emotion-driven behaviors; (8) behavioral skills training; (9) behavioral experiments; and (10) consolidating treatment gains and setting future goals (Pachankis, Harkness, Jackson, et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2021). Importantly, these modules were adapted for the cultural context of Chinese sexual minority men in a previous multistage adaptation process described elsewhere (Pan et al., 2021). In short, this adaptation process identified several ways in which LGBTQ-affirmative CBT content could be presented more harmoniously within Chinese culture, such as active collaboration on treatment goals rather than deference to a therapist as authority figure and revising the individualistic focus of assertiveness training to instead address the collectivistic context, often familial, in which expressions of personal authenticity occur.

Participants were instructed to read the materials and finish the exercises contained within the 10 modules at one-week intervals within a 4-month window. Participants received counseling support from one of the study’s five counselors via a call before initiating the intervention and in the middle of the intervention, and received weekly text support from their counselor via the platform related to each module. The five counselors included one nursing professor, one psychiatrist, two advanced nurses with certificates of psychological consultation, and one experienced VCT counselor; all therapists were trained by the developer of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT and have delivered original LGBTQ-affirmative CBT in-person with fidelity (Pan et al., 2021), and practiced each module with each other before engaging with participants. All counseling was supervised by a psychologist with a bicultural and bilingual background (Chinese and English) who provided weekly group supervision to ensure fidelity throughout the trial.

Outcomes and measures

All measures except HIV/syphilis testing were administered online at baseline and 4- and 8-month post-baseline follow-up. HIV/syphilis testing occurred at baseline and 8-month follow-up.

Primary outcome measure

HIV-transmission-risk behavior

The online Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) was used to assess past-30-day sexual behaviors. TLFB is an assessment of retrospective event-level risk behavior, including sexual-risk behaviors (Carey et al., 2001), and has been validated in the online format used here (Pedersen et al., 2012). Participants reported past 30-day sexual experiences with current main or casual partners in terms of number of partners, partner type, sexual act, condom use, and each partner’s HIV status. To facilitate recollection, meaningful events (e.g., holidays,) were used as reminders. HIV-transmission-risk behavior was operationalized as past-30-day condomless anal sex with a primary or casual partner given the lack of readily available HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in China (Guo et al., 2023).

Secondary outcome measures

HIV/syphilis testing

Participants performed HIV and syphilis self-testing using at-home kits (Alere Determine HIV 1/2 and treponema pallidum antibody detection) mailed from study staff or picked up from an office of our partner organization. This test involves collecting blood via a finger-prick and provides results in 20 minutes.

HIV social-cognitive mechanisms

The Condom Self-Efficacy Scale-Traditional Chinese (Y. Zhao et al., 2016) was used to assess one’s self-efficacy for consistently using condoms. The scale has 14 items and covers three subscales measuring one’s self-efficacy for consistent condom use, correct use, and related communication (e.g., “I could use a new condom each time I and my partner had sex.”). A Likert-type scale captured responses (1 = very unsure, 5 = very sure) with a total score ranging from 14 to 70; the items were summed. Cronbach’s alphas for this measure were 0.92, 0.94, and 0.90 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

The Decisional Balance for Condom Use Scale (Parsons et al., 2000; Prochaska et al., 1994) was used to assess the extent to which participants assign benefits to using condoms (e.g., “Sex without a condom is more spontaneous.”). It is an 18-item measure based on a Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). We calculated the sum score, with higher scores indicating greater benefits. The English version was translated and back-translated by bilingual scholars. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.75, 0,79, and 0.78 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Mental and behavioral health

Depression symptoms

The Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2014) was used to evaluate past-2-week participants’ depression severity (e.g., “little interest or pleasure in doing things”). Participants rated the frequency of each of nine symptoms using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly everyday), with a higher total score representing more severe depression symptom. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.86, 0.86, and 0.86 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Anxiety symptoms

The Chinese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2013) was used to evaluate past-2-week anxiety severity (e.g., “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”). The GAD-7 contains eight items rated using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly everyday). We calculated the sum score, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety severity. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.91, 0.93, and 0.91 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Suicidal ideation

The Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale- Chinese version (SIDAS; Han et al., 2017; van Spijker et al., 2014) was used to assess severity of suicide ideation (e.g., “How often have you had thoughts about suicide?”) in the past month. The SIDAS includes five items and is rated using an 11-point Likert scale (e.g., 0 = never, 10 = always). A sum score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater suicidal ideation severity. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.79, 0.89, and 0.79 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Alcohol use problems

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) was used to assess frequency and severity of alcohol use and related problems (e.g., “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?”), which is available in approximately 40 languages including Chinese. The AUDIT is a 10-item measure using eight 5-point Likert scales (e.g., 0 = never, 4 = daily or almost daily) and two 3-point Likert scales (e.g., 0 = no, 4 = yes, during the past year). We calculated a summed total score, with higher scores indicating more frequent and severe alcohol use. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89, 0.84, and 0.85 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Substance use problems

The Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT; Berman et al., 2005; Voluse et al., 2012) was used to assess frequency and severity of substance use problems for substances other than alcohol (e.g., “How often do you use drugs other than alcohol?”). The DUDIT is an 11-item measure rated using nine 5-point Likert scales (0 = never, 4 = daily or almost daily) and two 3-point Likert scales (0 = no, 4 = yes, over the past year). We used the Madarin version (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2005). We calculated a sum score with higher scores indicating more frequent and severe use. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.80, 0.79, and 0.79 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Minority stress mechanisms

The Concealment Motivation Subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS; Mohr & Kendra, 2011; Chinese version; Su & Zheng, 2022) was used to assess participants’ sexual orientation concealment (e.g., “I keep careful control over who knows about my same-sex romantic relationships.”). This subscale contains three items rated using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 6 = agree strongly). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.86, 0.91, and 0.90 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

The Acceptance Concerns Subscale of the LGBIS was used to assess participants’ acceptance concerns (e.g., “I often wonder whether others judge me for my sexual orientation.”). This sub-scale contains three items rated using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 6 = agree strongly). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.83, 0.91, and 0.91 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

The Internalized Homonegativity Subscale of LGBIS was used to assess participants’ internalized stigma (e.g., “If it were possible, I would choose to be straight.”). This subscale contains three items rated using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 6 = agree strongly). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89, 0.86, and 0.86 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively. We calculated a mean score for each of the LGBIS subscales, with higher scores indicating greater concealment, acceptance concern, and internalized stigma.

Universal mechanisms

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form (DERS-SF; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Kaufman et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018) was used to evaluate participants’ emotion dysregulation (e.g., “have no idea how I am feeling.”). The DERS-SF contains 18 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost never [0–10%], 5 = almost always [91–100%]). We calculated a sum score, with higher scores indicating greater emotion dysregulation. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.87, 0.90, and 0.90 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Dambi et al., 2018; Zimet et al., 1990) was used to assess participants’ perceived social support from a significant other, family, and friends (e.g., “There is a special person who is around when I am need”). The MSPSS contains 12 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree, 7 = very strongly agree). We calculated a mean score, with higher scores indicating higher perceived social support. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.91, 0.93, and 0.91 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

The Brooding Subscale of the Ruminative Responses Scale (Han & Yang, 2009; Treynor et al., 2003) was used to assess participants’ cognitive processes when feeling down, sad, or depressed (e.g., think “what am I doing to deserve this?”). This subscale contains five items rated using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 4 = almost always). We calculated the sum score, with higher scores indicating higher rumination. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.86, 0.87, 0.87 at baseline and 4- and 8-month follow-up, respectively.

Analytic plan

To examine the efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT in the Chinese context, we used an intent-to-treat analysis in which data were analyzed according to participants’ treatment assignment regardless of their retention. Descriptive statistics (i.e., means [M] and standard deviations [SD]; frequencies and proportions) were calculated for the overall sample. All variables included in analytic models were assessed for normality using skewness thresholds of ≥ 2 and kurtosis thresholds of ≥ 7. Outliers were evaluated using histograms and boxplots (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2010). All variables met assumptions of normality except for HIV-transmission-risk behavior, AUDIT, DUDIT, and SIDAS, which were zero-inflated. For models fit with the AUDIT, DUDIT, and SIDAS (ordinal variables), we used generalized linear mixed effects models with square root transformation to address normality. For HIV-transmission-risk behavior (a count variable), we followed best practices for zero-inflated count data and used a negative binomial zero-inflated regression model to account for the overdispersion and excess zeros (Brooks et al., 2017).

We used generalized linear mixed effect modeling to test whether receipt of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT vs. assessment only affected changes in the count of past-30-day HIV-transmission-risk behavior from baseline to 8-month follow-up (Condition × Time). We used an unstructured covariance matrix (Fitzmaurice et al., 2011). To test whether treatment efficacy on our primary outcome variable, HIV-transmission-risk behavior, was moderated by baseline levels of minority stress, we added a three-way interaction into our linear mixed effect models (three-way interactions of Condition × Time × Moderator). Each moderator was entered separately into the models for each outcome. Significant three-way interactions of Condition × Time × Stigma were further probed and plotted. Finally, we examined whether treatment engagement (i.e., number of ICBT sessions completed) was associated with outcomes by examining a Time × Sessions Completed interaction among participants randomized to the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition. All results were evaluated at p < .05. We reported means, standard deviations, 95% confidence intervals, and effect sizes for all models. Effect sizes (d) for linear mixed models were calculated as mean pre-post change in the immediate intervention condition minus the mean pre-post change in the assessment-only control condition, divided by the pooled baseline standard deviation (Morris, 2008). Effects were unable to be tested for HIV and STI test results due to the fact that no participant tested positive for HIV and one participant in the assessment-only condition tested positive for syphilis at all three timepoints (consistent with the type of syphilis test used here, in which a positive result does not necessarily indicate a new infection). All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.2).

Ethical considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee (2000029433) and the Institutional Review Board of the Behavioral and Nursing Research of Central South University (E2021128). All participants provided informed consent. In accordance with local Chinese regulations (China Medical Products Administration, 2020), parental consent is not required for participants ages 16–17 living in China; however, no participant under age 18 participated in this study. Study data, participants’ safety, and adverse events were reviewed and monitored by a data and safety monitoring board composed of researchers with relevant expertise in the US and China.

Results

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the participants – 120 Chinese young sexual minority men (age M = 23.22, SD = 3.26) – stratified by treatment condition. About 91.7% of the sample self-identified as gay and 8.3% as bisexual. Most participants (75.8%) reported having a college education, higher than the average education among the Hunan population (Hunan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2021). Slightly over half (55.8%) reported being single but having a regular partner. Nearly half (49.2%) reported having low income (<3000RMB [≈$460] / month), slightly less than half (45.8%) had a full-time job, and 41.7% were students. Participants in the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition completed a mean of 6.63 (SD = 3.88) sessions and half (50.0%) completed all 10 sessions; two participants withdrew after completing no or one session, respectively. No adverse events occurred throughout the trial.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristic | Total (n = 120) | LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT (n = 60) | Assessment Only (n = 60) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 23.22 | 3.26 | 23.73 | 3.36 | 22.72 | 3.09 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||||

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||

| Male | 120 | 100.0 | 60 | 100.0 | 60 | 100.0 |

| Female | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Bisexual | 10 | 8.3 | 3 | 5.0 | 7 | 11.7 |

| Gay | 110 | 91.7 | 57 | 95.0 | 53 | 88.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Han | 113 | 94.2 | 58 | 96.7 | 55 | 91.7 |

| Hui | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 |

| Miao | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 3.3 | 1 | 1.7 |

| Tujia | 3 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.0 |

| Education degree | ||||||

| Junior high school or less | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 |

| High school/vocational school | 15 | 12.5 | 9 | 15.0 | 6 | 10.0 |

| College/four-year university | 91 | 75.8 | 44 | 73.3 | 47 | 10.0 |

| Graduate school or above | 13 | 10.8 | 7 | 11.7 | 6 | 78.3 |

| Marital/relationship status | ||||||

| Single, without a regular partner | 46 | 38.3 | 22 | 36.7 | 24 | 40.0 |

| Single, but having a regular partner | 67 | 55.8 | 34 | 56.7 | 33 | 55.0 |

| Married | 5 | 4.2 | 2 | 3.3 | 3 | 5.0 |

| Divorced | 2 | 1.7 | 2 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Estimated income per month | ||||||

| <3000 RMB | 59 | 49.2 | 30 | 50.0 | 29 | 48.3 |

| 3000~5000 RMB | 31 | 25.8 | 14 | 23.3 | 17 | 28.3 |

| 5000~8000 RMB | 17 | 14.2 | 9 | 15.0 | 8 | 13.3 |

| >8000 RMB | 13 | 10.8 | 7 | 11.7 | 6 | 10.0 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Full-time job | 55 | 45.8 | 26 | 43.3 | 29 | 48.3 |

| Part-time job | 9 | 7.5 | 5 | 8.3 | 4 | 6.7 |

| Student | 50 | 41.7 | 26 | 43.3 | 24 | 40.0 |

| Unemployment | 6 | 5.0 | 3 | 5.0 | 3 | 5.0 |

Intervention efficacy

HIV-transmission risk behavior

HIV-transmission risk behavior, operationalized in terms of condomless anal sex acts with any partner type (i.e., main or casual), significantly decreased over time in both conditions. No Condition × Time interaction was observed, indicating that the significant decrease in HIV-transmission risk behavior across 4- and 8-month follow-ups did not differ between the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT and assessment-only conditions (see Table 2). Effect sizes for condition comparisons were small at 4-month (d = −0.01) and (d = −0.02) at 8-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Condition × Time Comparisons of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT and Assessment Only

| LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT n = 60 | Assessment Only n = 60 | Condition × Time n = 120 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| HIV-TRANSMISSION-RISK BEHAVIOR | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | β | 95% CI | p-value | Cohen’s d | |

|

| ||||||||

| HIV-transmission-risk Behavior a | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1.98 | 3.78 | 1.80 | 2.34 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 0.58 | 1.06 | 0.80 | 2.04 | −0.17 | [−0.91, 0.57] | 0.65 | −0.01 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 0.50 | 1.22 | 0.65 | 1.36 | −0.36 | [−1.17, 0.46] | 0.39 | −0.02 |

|

| ||||||||

| HIV SOCIAL-COGNITIVE MECHANISMS | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Condom Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES-TC) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 55.5 | 9.46 | 55.9 | 9.63 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 56.5 | 8.50 | 57.1 | 9.95 | −0.09 | [−3.14, 2.96] | 0.95 | −0.01 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 58.8 | 7.05 | 57.9 | 8.53 | 1.34 | [−1.71, 4.39] | 0.39 | 0.11 |

| Decisional Balance for Condom Use (DBCUS) | ||||||||

| Baseline 61.2 | 8.29 | 61.5 | 10.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline 59.1 | 9.65 | 60.6 | 9.99 | −1.15 | [−4.75, 2.44] | 0.53 | −0.08 | |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline 57.4 | 8.04 | 59.3 | 10.0 | −1.36 | [−4.95, 2.24] | 0.46 | −0.10 | |

|

| ||||||||

| MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Depression Symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 12.4 | 5.70 | 10.4 | 5.28 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 8.33 | 3.85 | 10.0 | 4.74 | −3.65 | [−5.57, −1.73] | <0.001 | −0.50 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 7.28 | 4.47 | 10.0 | 3.98 | −4.65 | [−6.57, −2.73] | <0.001 | −0.63 |

| Anxiety Symptoms (GAD-7) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 9.55 | 5.05 | 9.03 | 5.06 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 5.72 | 3.77 | 8.80 | 4.64 | −3.60 | [−5.43, −1.77] | <0.001 | −0.51 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 5.54 | 3.34 | 8.47 | 4.22 | −3.45 | [−5.28, −1.62] | <0.001 | −0.49 |

| Suicidal Ideation (SIDAS) b | ||||||||

| Baseline | 5.07 | 6.70 | 5.47 | 7.36 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 2.09 | 4.56 | 4.17 | 7.30 | −0.49 | [−1.07, 0.08] | 0.09 | −0.22 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 1.76 | 3.74 | 2.97 | 6.10 | −0.21 | [−0.79, 0.37] | 0.47 | −0.09 |

| Alcohol Use (AUDIT) b | ||||||||

| Baseline | 4.32 | 5.47 | 4.88 | 5.87 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 3.44 | 4.57 | 4.68 | 5.53 | −0.25 | [−0.66, 0.16] | 0.23 | −0.16 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 2.43 | 3.52 | 5.30 | 5.89 | −0.63 | [−1.03, −0.22] | 0.003 | −0.40 |

| Substance Use (DUDIT) b | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1.38 | 2.99 | 1.97 | 3.82 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 0.91 | 2.17 | 1.40 | 3.03 | −0.11 | [−0.51, 0.29] | 0.59 | −0.07 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 0.61 | 1.39 | 1.33 | 2.91 | −0.12 | [−0.52, 0.28] | 0.56 | −0.08 |

|

| ||||||||

| HIV/SYPHILLIS TEST RESULTS | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | β | 95% CI | p-value | Cohen’s d | |

|

| ||||||||

| HIV Test Results c | ||||||||

| Baseline | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Syphilis Test Results c | ||||||||

| Baseline | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1.7% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1.7% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1.7% | -- | -- | -- | -- |

HIV-transmission-risk behavior was operationalized as number of condomless anal sex acts using a zero-inflated negative binomial model.

Mixed effects model conducted with root squared transformed variables to adjust for issues of non-normality. Means and SDs are the raw variables for interpretability

Displaying frequencies for positive testing results

HIV social-cognitive mechanisms

No significant differences between the two conditions were observed for condom use self-efficacy and decisional balance (see Table 2).

Mental and behavioral health

Condition × Time interactions were observed for mental and behavioral health outcomes. For participants assigned to LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT, we found significantly greater improvements in mental health (i.e., depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms) and behavioral health (i.e., alcohol use problems) at 8-month follow-up (and at 4-month follow-up for depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms) compared to the assessment-only condition. Effect sizes for these outcomes were medium and in the expected direction (see Figure 2). There was not a significant Condition × Time interaction observed for substance use problems or suicidal ideation; however, there was a significant reduction in suicidal ideation for all participants across the 4- and 8-month follow-ups (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Significant Outcomes by Treatment Condition and Follow-up Assessment Periods

Note: Gray areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Scores for alcohol use problems were transformed using square root.

Minority stress mechanisms

Condition × Time effects were observed for acceptance concerns and internalized stigma, indicating relative improvements in these minority stress mechanisms for participants in the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition compared to the assessment-only condition at 4-month (acceptance concerns, d = −0.36) and 8-month follow-up (internalized homonegativity, d = −0.28, see Figure 2). No Condition × Time effects were observed for sexual orientation concealment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Condition × Time Comparisons of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT and Assessment Only

| LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT n = 60 | Assessment Only n = 60 | Condition × Time n = 120 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| MINORITY STRESS MECHANISM | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | β | 95% CI | p-value | Cohen’s d | |

|

| ||||||||

| Concealment Motivation (LGBIS-CM) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 4.66 | 1.27 | 4.36 | 1.25 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 4.59 | 1.23 | 4.40 | 1.25 | −0.18 | [−0.56, 0.21] | 0.37 | −0.12 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 4.55 | 1.23 | 4.44 | 1.22 | −0.22 | [−0.60, 0.17] | 0.27 | −0.15 |

| Acceptance Concerns (LGBIS-AC) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 4.73 | 1.23 | 4.63 | 1,05 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 4.38 | 1.18 | 4.75 | 1.05 | −0.53 | [−0.92, −0.14] | 0.008 | −0.36 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 4.36 | 1.40 | 4.53 | 1.11 | −0.30 | [−0.69, 0.09] | 0.129 | −0.20 |

| Internalized Stigma (LGBIS-IH) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 3.68 | 1.60 | 3.19 | 1.30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 3.60 | 1.52 | 3.37 | 1.46 | −0.32 | [−0.72, 0.09] | 0.13 | −0.20 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 3.30 | 1.59 | 3.22 | 1.37 | −0.44 | [−0.84, −0.03] | 0.04 | −0.28 |

|

| ||||||||

| UNIVERSAL MECHANISMS | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Emotion Dysregulation (DERS-SF) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 55.9 | 9.64 | 54.70 | 10.7 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 50.0 | 11.5 | 55.2 | 10.0 | −6.24 | [−9.95, −2.52] | 0.001 | −0.44 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 48.2 | 10.6 | 53.0 | 10.2 | −6.01 | [−9.73, −2.29] | 0.002 | −0.42 |

| Social Support (MSPSS) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 3.53 | 1.28 | 3.66 | 1.30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 3.79 | 1.34 | 3.49 | 1.26 | 0.40 | [−0.01, 0.80] | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 3.98 | 1.30 | 3.81 | 1.18 | 0.28 | [−0.12,0.69] | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Rumination (RRS) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 13.9 | 3.33 | 14.2 | 3.13 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 12.6 | 3.12 | 13.6 | 3.67 | −0.70 | [−1.90, 0.49] | 0.248 | −0.15 |

| 8-Month Post-Baseline | 12.3 | 2.77 | 13.0 | 3.48 | −0.60 | [−1.79, 0.60] | 0.326 | −0.13 |

Universal mechanisms

Condition × Time effects were observed for emotion dysregulation indicating relative improvements in this universal mechanism for participants in the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition compared to the assessment-only condition at both the 4- and 8-month follow-up (d = −0.44, d = −0.42). We also found a marginally significant effect for social support at the 4-month follow-up (d = −0.26, see Figure 2). No Condition × Time interaction was observed for rumination (see Table 3).

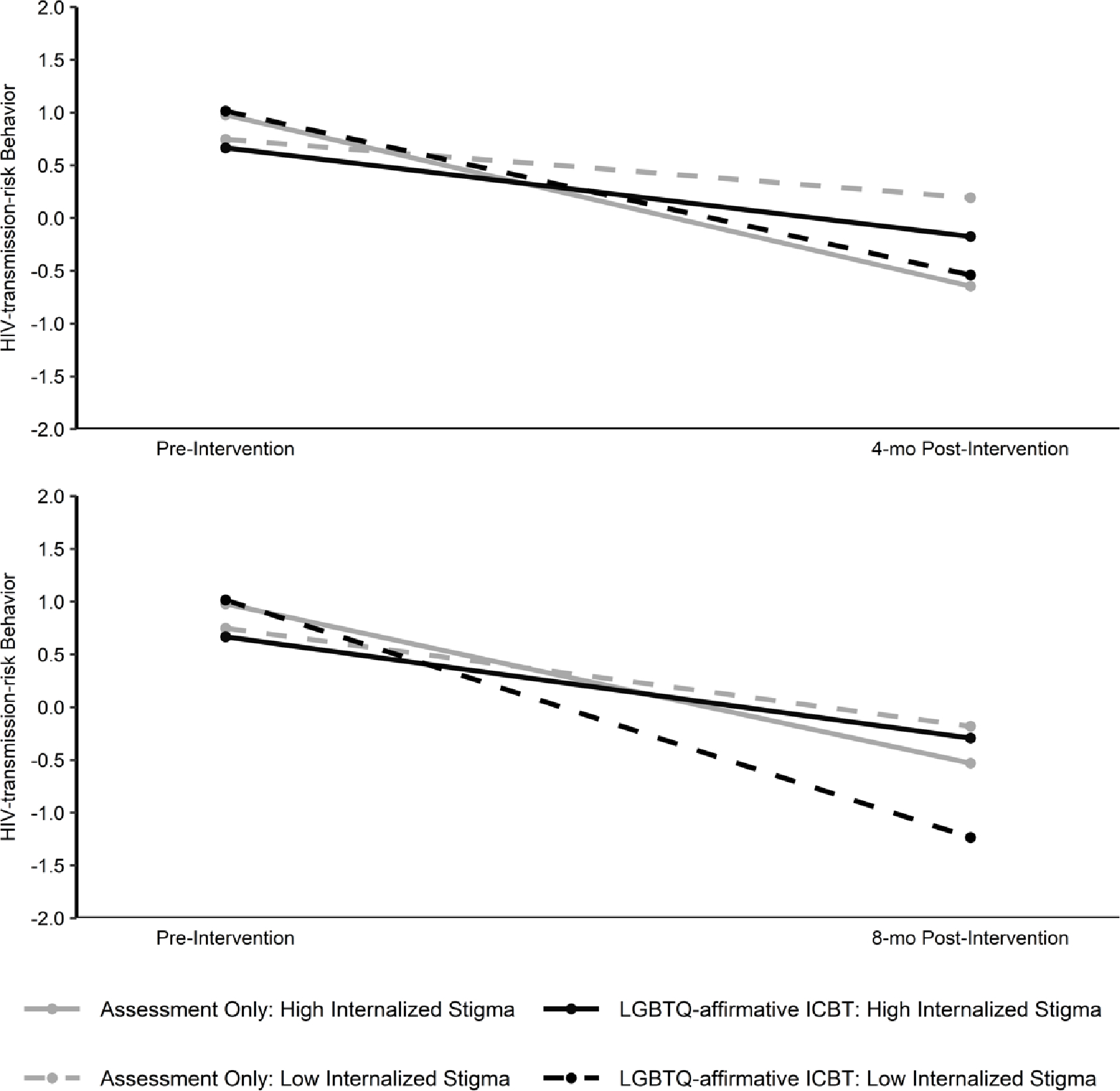

Intervention efficacy moderated by minority stress

Of the minority stress variables examined as potential treatment effect moderators, only internalized stigma significantly moderated Condition × Time interaction effects for HIV-transmission risk behavior at both the 4- and 8-month follow-up (see Table 4). Probing these interactions further, we found greater efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to assessment only for participants experiencing lower levels of internalized stigma, probed at one standard deviation below the mean (see Figure 3). Specifically, for participants with low levels of internalized stigma, we observed significant improvements in HIV-transmission risk behavior scores between baseline and 4-month follow-up for participants in the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition (Mean Difference [MD] = 1.55, SE = 0.040, p = 0.001), but not for those in the assessment-only condition (MD = 0.55, SE = 0.32, p = 0.49). We found a similar effect when comparing baseline to 8-month follow-up for participants in the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition (MD = 2.25, SE = 0.51, p = 0.0001) compared to the assessment-only condition (MD = 0.93, SE = 0.34, p = 0.07). For participants with higher levels of internalized stigma, probed at one standard deviation above the mean, we did not find greater efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to assessment only at either follow-up period. Concealment motivation and acceptance concerns did not moderate Condition × Time interaction effects for HIV-transmission risk behavior at 4- or 8-month follow-up.

Table 4.

HlV-transmission-risk Behavior

| 4-Month Post-Baseline | 8-Month Post Baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | Cohen’s d | β | 95% CI | p-value | Cohen’s d | |

|

| ||||||||

| Condition × Time × Concealment Motivation | 0.06 | [−0.55, 0.66] | 0.85 | 0.24 | 0.18 | [−0.49, 0.84] | 0.60 | 0.36 |

| Condition × Time × Internalized Stigma | 0.61 | [0.09, 1.12] | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.64 | [0.08, 1.20] | 0.03 | 0.42 |

| Condition × Time × Acceptance Concerns | −0.20 | [−0.82, 0.41] | 0.52 | 0.20 | −0.41 | [−1.11, 0.29] | 0.25 | 0.43 |

Note. HIV-transmission-risk behavior was operationalized as number of condomless anal sex acts using a zero-inflated negative binomial model.

Figure 3.

Moderation of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT efficacy on HIV-transmission-risk behavior by internalized stigma at 4-month follow-up and 8-month follow-up

Intervention efficacy moderated by treatment engagement

In analyses conducted within the LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT condition, we found significant Time × Sessions Completed interactions when predicting suicidal ideation (SIDAS) and rumination (RRS), but no other outcomes. Greater number of sessions completed was associated with greater reductions in suicidal ideation at the 4-month follow-up and rumination at the 8-month follow-up. Supplemental Table 1 displays these results.

Discussion

This study represents the first test of an intervention to address minority stress en route to improving sexual minority men’s mental and behavioral health in China. Although results show that LGBTQ-affirmative internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) did not exert significantly stronger effects than an assessment-only control condition on HIV-transmission-risk behavior or HIV social-cognitive mechanisms (i.e., condom use self-efficacy, decisional balance for condom use), effect sizes for this outcome were in the small-to-medium range consistent with previous trials of psychosocial interventions for this population (Pantalone et al., 2020). Further, LGBTQ-affirmative CBT yielded comparatively greater improvements in mental and behavioral health (i.e., depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, alcohol use problems) and theorized minority stress mechanisms (i.e., acceptance concerns, internalized homonegativity) and universal mechanisms (i.e., emotion regulation) compared to the assessment-only control condition. There was no significant difference between conditions for substance use problems or suicidal ideation. Moderation analyses revealed greater potential efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to an assessment-only control for decreasing HIV-transmission-risk behavior for participants experiencing lower, compared to higher, levels of internalized stigma.

Overall, treatment effects for mental and behavioral problems and minority stress and universal risk factors were in the expected direction and consistent with previous research on LGBTQ-affirmative CBT specifically (Craig, Eaton, et al., 2021; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2015; Pachankis, McConocha, et al., 2020) and psychosocial interventions focused on sexual minority individuals’ co-occurring syndemic outcomes more generally (Pantalone et al., 2020). Although a decrease over time was observed for both conditions in HIV-transmission-risk behavior, the lack of significant differences between conditions in this outcome and its theorized social-cognitive correlates (i.e., condom use self-efficacy, decisional balance for condom use) is consistent with previous research (Pachankis, Harkness, Maciejewski, et al., 2022) and could be explained by several factors. First, LGBTQ-affirmative CBT primarily addresses minority stress as a transdiagnostic source of sexual minority individuals’ co-occurring psychosocial health risks. In so doing, the treatment does not specifically focus on HIV-transmission-risk behaviors, such as consistent condom use, but rather assumes that these outcomes will be improved as a result of promoting minority stress coping (Pachankis, Harkness, Jackson, et al., 2022). While perhaps true in the case of mental health outcomes as found in this study, this theoretical assumption might be less true in the case of behavioral health patterns, thus explaining the lack of efficacy for this particular outcome. Second, repeated assessment of condom use and other behavioral outcomes (e.g., substance use) has been found to be an effective strategy to reduce these outcomes in and of itself (Newcomb et al., 2018). Indeed, participants in both conditions in this study experienced reductions in HIV-transmission-risk behavior. Future research is needed both to study ways to more explicitly address HIV-transmission-risk behavior in a transdiagnostic intervention such as this focused more on minority stress pathways than on any specific outcome, as well as ways to enhance efficient intervention approaches such as weekly self-assessment, which hold preliminary promise (Rapaport et al., 2023). Third, HIV-transmission-risk behavior was relatively infrequent in this study, thereby limiting variability from which to predict condition effects. Relatedly, condomless anal sex was assessed across the past 30 days rather than over a longer period (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2015) so as to guard against retrospective recall bias introduced by reporting across longer periods. Yet, this decision might have limited variability in HIV-transmission-risk acts. Fourth, this trial was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hunan Province, China, and travel restrictions and lockdowns (e.g., in residential quarters and schools) were in place (Xinhua, 2021), which led to known decrease of sexual activities and other behavioral risks (i.e., alcohol and substance use problems; Yang et al., 2022). Fifth, perhaps changes in behavioral risks such as HIV-transmission-risk behavior are secondary to improvements in depression and anxiety and, as such, might take longer than the current follow-up period to improve.

On the other hand, effect sizes for depression and anxiety symptoms and alcohol use problems were medium-to-large and in the expected direction, suggesting that LGBTQ-affirmative CBT can have a powerful impact on the mental and behavioral health of young Chinese sexual minority men, with capability for being delivered and disseminated in similar high-stigmatized contexts with limited affirmative mental health resources. These effects are generally consistent with previous studies testing the use of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT delivered in person (Craig, Eaton, et al., 2021; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2015; Pachankis, McConocha, et al., 2020) and with general CBT approaches adapted for Chinese people (Ng & Wong, 2018). However, the present effect sizes were much larger than those found in the most similar previous study of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT delivered in the US using the same delivery platform, research design, and control condition. In that study, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT yielded no significantly greater improvement in depression or anxiety symptoms or alcohol use problems compared to the assessment-only control (Pachankis et al., 2023). A key difference between that study and the present study is location, with the present study being delivered in the arguably higher stigma context of China with fewer available LGBTQ-affirmative supports. In fact, the US trial of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT found that the treatment was only efficacious in higher-stigma US counties, supporting the possibility that stigma context moderates intervention efficacy, a postulation also consistent with other treatment effect moderation research pertaining to interventions for sexual minority and other stigmatized populations (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2021).

Consistent with previous research on minority stress in the Chinese context (Sun, Pachankis, et al., 2020), this study found that acceptance concerns, also sometimes referred to as rejection sensitivity (Pachankis et al., 2008), showed the strongest comparative reductions of the minority stress mechanisms between conditions, whereas internalized stigma showed delayed comparative reductions between conditions, emerging at the 8-month follow-up. These findings are among the first to suggest potential minority stress mechanisms within studies of LGBTQ-affirmative interventions and are consistent with the results of at least one other intervention – a brief psychoeducational intervention focused squarely on internalized stigma – showing efficacy for improving that outcome (Lin & Israel, 2012). The fact that LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT exerted significant impact on acceptance concerns suggests its promise in addressing interpersonal forms of minority stress perhaps particularly common in collectivistic cultural contexts where interpersonal relations and acceptance by others are important in one’s construction of self (Sun et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2023).

To advance research on treatment effect moderation by stigma (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2021), we also examined minority stress factors as moderators of treatment efficacy on the primary outcome, HIV-transmission-risk behavior. We found that internalized stigma, in particular, moderated the relative efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT. Specifically, the moderation analysis revealed greater treatment efficacy for improving HIV-transmission-risk behavior for participants experiencing lower levels of internalized stigma at baseline. This finding contradicts previous research on LGBTQ-affirmative CBT delivered to sexual minority men in the US, in which participants with higher levels of internalized stigma benefited more from the intervention in terms of depression, anxiety, heavy alcohol use, and HIV-transmission-risk behavior (Millar et al., 2016). However, that study differed from the present study in several notable respects. In addition to being conducted in the US, that study employed a waitlist comparison, both implicit and explicit measures of internalized stigma, and tested LGBTQ-affirmative CBT as delivered synchronously in person. Whether these methodological distinctions, or alternately, differences in the experiences of stigma or culture, explained this opposite pattern of findings remains to be tested. One possibility is that in a context of highly normative structural stigma, internalized stigma poses a high barrier to psychological engagement with the minority stress treatment content. If this were indeed the case, future research would need to identify ways to lower such psychological barriers to engagement in contexts in which internalized stigma reflects structural norms for the treatment of sexual minority individuals.

Finally, participants in the ICBT conditions completed an average of 6.63 sessions. This rate of engagement was slightly higher than a similar trial in the US (Pachankis et al., 2023), but lower than other studies of ICBT (Andrews et al., 2018). Treatment engagement did not yield significant moderating effects in the primary outcome of HIV-transmission-risk behavior, nor in depression and anxiety, which was inconsistent with a similar study in the U.S. (Pachankis et al., 2023). However, increased participant engagement was related to greater reductions in suicidal ideation at the 4-month follow-up and greater reduction in rumination at the 8-month follow-up. Neither suicidal ideation nor rumination were significant in the efficacy analyses, suggesting that a higher intervention dosage might be necessary to effect change in these perhaps ingrained cognitive-affective processes. Therefore, future research should consider strategies to improve online treatment engagement, for example strengthening the digital therapeutic alliance, increasing therapist support, and improving digital platform usability and satisfaction.

LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT also demonstrated comparatively greater improvements in emotion dysregulation. This finding extends the relatively scant previous intervention research that has examined the efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT on potential intervention mechanisms, in which factors such as hope and optimism have been found to be impacted (Craig, Eaton, et al., 2021; Craig, Leung, et al., 2021). This finding is also consistent with the theoretical basis of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) and empirical research in support of that theory (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Pachankis, Rendina, et al., 2015) and extends this work to an experimental test of an intervention targeting emotion dysregulation in a high-stigma context.

Given that this study found stronger efficacy for LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT compared to a similar trial of the treatment conducted in the US, which found that the treatment was most effective in US counties with the highest degrees of structural support (Pachankis et al., 2023), future research of this intervention might seek ways to more directly address the structural context to enhance impact. Such a focus on structural context may be particularly relevant for sexual minority individuals in China, where LGBTQ structural stigma is high (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019). Indeed, an emerging body of research has found that the structural context in which psychotherapies are delivered is associated with psychotherapy efficacy. For instance, psychotherapy has been found to be less effective for Black youth living in U.S. counties with higher anti-Black racism (Price et al., 2022). Such findings suggest that individual-level interventions delivered to stigmatized populations might need to be adapted to address the structural determinants that might underlie much of the disproportionate mental and behavioral health burden among these populations (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2021). How to best do this remains a question for future research, but might entail adjunctively facilitating community connectedness and shared resilience (Jackson et al., 2021).

The findings of the present study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size of this trial might have limited power to detect significant changes between conditions in all outcomes. Indeed, this study was powered to detect effect sizes of at least d = 0.40, but under assumptions of general linear models not met by the HIV-transmission-risk behavior count outcome. Second, a weekly assessment of mood and minority stress and behavioral health was selected as a relatively active control group. Results of this present study support other preliminary research showing that repeated assessment of mental and behavioral health outcomes is associated with improvement over time in those outcomes (Kauer et al., 2012; Livingston et al., 2017). Whether LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT might have yielded stronger relative effects than a waitlist control condition, more commonly used in this research area, remains unknown. Third, this trial was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictive policies in China, which might have influenced intervention efficacy in ways unknown, although stress, mental health, and behavioral outcomes such as HIV-transmission-risk behavior have all been documented to have been influenced by the pandemic (Hong et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). Notably, on the one hand, COVID-19 control measures could have exacerbated mental health disparities among LGBTQ youth (Ormiston & Williams, 2022), thereby increasing the value of an LGBTQ-affirmative CBT intervention. On the other hand, social restriction policies reduced the rate of sexual practices (Masoudi et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022) and thus may have reduced the ability of the intervention tested here to exert a meaningful impact on HIV-transmission-risk behavior.

The study findings have implications for future research and practice. Overall, results suggest that LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT has potential to reduce mental and behavioral health problems among young sexual minority men in China and perhaps other similar contexts globally. Because stigma can hinder access to identity-specific services, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT might be particularly well-suited to addressing minority stress and related mental and behavioral health risks in context such as China where stigma is high. This study used an online platform to deliver the intervention, whereas future research might identify other platforms, including mobile phone applications, that might achieve even wider dissemination. The present findings can serve as the basis of future research to test the efficacy, relative acceptability, and cost-effectiveness of LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT as compared to other delivery modalities, including in-person. Further, the acceptability and satisfaction of such an online counseling intervention can be qualitatively examined, and relevant modifications can be incorporated to facilitate widely scaled interventions in China and other high-stigma contexts. Future research is also needed to identify the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT in general and ICBT in particular. This study is among the few to identify potential minority stress mechanisms, including acceptance concerns and internalized stigma, but no study to date, including this one, has been sufficiently powered and employed long-enough follow-up periods to identify mechanisms serving as statistical mediators of LGBTQ-affirmative CBT efficacy (Burger et al., 2023). Future research is needed to identify these and other such mechanisms to enhance the efficacy of these interventions through enhancing their focus on their active targets.

In conclusion, this study finds that Chinese culturally adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT demonstrated medium-to-large comparative effects across most assessed mental and behavioral health outcomes, as well as small-to-medium comparative effects across several minority and universal mechanisms. In terms of HIV-transmission-risk behavior, LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT was associated with greater efficacy for Chinese young sexual minority men experiencing lower levels of internalized stigma, suggesting both potential areas of future research and implementation targets. Given the preliminary efficacy of Chinese-adapted LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT, scaling up this intervention could be one strategy to help advance internationals goals of reducing the impact of HIV on particularly affected populations (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2022), and advancing mental and behavioral health equity for this increasingly visible segment of the global population (World Health Organization, 2015).

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance.

Sexual minority men represent one of the highest-risk populations for co-occurring mental and behavioral problems globally, yet few psychosocial interventions have been tested for efficacy to address the syndemic factors that generate these challenges in high-stigma contexts like China. This first randomized trial of LGBTQ-affirmative internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) in China finds that the treatment has potential to improve sexual minority men’s mental and behavioral health concerns. Results of this trial can inform the future design and delivery of online interventions for young sexual minority men living in high-stigma contexts with limited affirmative health resources.

Highlights.

LGBTQ-affirmative internet-based CBT was tested among sexual minority men in China.

LGBTQ-affirmative ICBT yielded greater mental health effects than assessment-only.

Treatment impact on HIV risk was stronger for those with lower internalized stigma.

Identity-focused treatments might be most efficacious in high-stigma settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their help with study implementation and intervention delivery: Kriti Behari, Ying He, Xiangyu Li, Yang Xiong, Run Wang. We thank the members of the data and safety monitoring board for this clinical trial: Aaron Blashill, Corina Lelutiu-Weinberger, Haiqun Lin, Honghong Wang. The authors would also like to acknowledge the participants who participated in this trial for their contributions to the research and the staff at Zuo An Cai Hong (an LGBTQ community-based organization in China) for their assistance in recruitment for this study.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (R21TW011762); Mengyao Yi’s contributions to this study were also supported by the postgraduate scientific research innovation project of Hunan Province (CX20210349) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (2021zzts1009). Shufang Sun’s effort on this paper is also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P30AI042853) and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K23AT011173). Si Pan’s effort on this study is also supported by the Nature Science Foundation of China (72074226). Ashley Hagaman’s effort on this paper is also supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH125142). This work used the BASS platform from the eHealth Core Facility at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

John E. Pachankis receives royalties from Oxford University Press for books related to LGBTQ-affirmative mental health treatments, and other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

John Pachankis receives royalties from Oxford University Press for books related to LGBTQ-affirmative mental health treatments.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almlöv J, Carlbring P, Källqvist K, Paxling B, Cuijpers P, & Andersson G (2011). Therapist effects in guided internet-delivered CBT for anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39(3), 311–322. 10.1017/s135246581000069x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Carlbring P, & Lindefors N (2016). History and Current Status of ICBT. In Lindefors N & Andersson G (Eds.), Guided Internet-Based Treatments in Psychiatry (pp. 1–16). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-06083-5_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Riper H, & Hedman E (2014). Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13(3), 288–295. 10.1002/wps.20151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Titov N, Dear BF, Rozental A, & Carlbring P (2019). Internet-delivered psychological treatments: from innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 20–28. 10.1002/wps.20610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Basu A, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, English CL, & Newby JM (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 70–78. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, & Barlow DH (2014). Development and Validation of the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 815–830. 10.1037/a0036216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, & Schlyter F (2005). Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. European Addiction Research, 11(1), 22–31. 10.1159/000081413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjureberg J, Ojala O, Berg A, Edvardsson E, Kolbeinsson Ö, Molander O, Morin E, Nordgren L, Palme K, Särnholm J, Wedin L, Rück C, Gross JJ, & Hesser H (2022). Targeting maladaptive anger with brief therapist-supported internet-delivered emotion regulation treatments: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 10.1037/ccp0000769 (Advance online publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ME, Kristensen K, Benthem K. J. v., Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, Skaug HJ, Mächler M, & Bolker BM (2017). Modeling zero-inflated count data with glmmTMB. BioRxiv, 132753. 10.1101/132753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR (1981). Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Wang K, Hollinsaid NL, Safren SA, & Pachankis JE (2023). Toward a Mechanistic Understanding of LGBTQ-Affirmative CBT: Testing Treatment Mediators in a Sample of Young Adult Gay and Bisexual Men [Unpublished manuscript]. Yale University, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Burki T (2017). Health and rights challenges for China’s LGBT community. The Lancet, 389(10076), 1286. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30837-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, 2nd ed. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona N, Madigan R, & Sauer S (2021). How Minority Stress Becomes Traumatic Invalidation: An Emotion-Focused Conceptualization of Minority Stress in Sexual and Gender Minority People. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 29(2), 185–195. 10.1037/cps0000054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, & Weinhardt LS (2001). Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International Journal of Std & Aids, 12(6), 365–375. 10.1258/0956462011923309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Internet Network Information. (2023). The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. [Google Scholar]

- China Medical Products Administration. (2020). Good Clinical Practice. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/xxgk/fgwj/xzhgfxwj/20200426162401243.html [Google Scholar]