Abstract

The inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) is a central regulator of NF-κB signaling. All IKK complexes contain hetero- or homodimers of the catalytic IKKβ and/or IKKα subunits. Here, we identify a YDDΦxΦ motif, which is conserved in substrates of canonical (IκBα, IκBβ) and alternative (p100) NF-κB pathways, and which mediates docking to catalytic IKK dimers. We demonstrate a quantitative correlation between docking affinity and IKK activity related to IκBα phosphorylation/degradation. Furthermore, we show that phosphorylation of the motif’s conserved tyrosine, an event previously reported to promote IκBα accumulation and inhibition of NF-κB gene expression, suppresses the docking interaction. Results from integrated structural analyzes indicate that the motif binds to a groove at the IKK dimer interface. Consistently, suppression of IKK dimerization also abolishes IκBα substrate binding. Finally, we show that an optimized bivalent motif peptide inhibits NF-κB signaling. This work unveils a function for IKKα/β dimerization in substrate motif recognition.

Subject terms: Kinases, X-ray crystallography, NF-kappaB

The inhibitor of kB kinase (IKK) is a central regulator of NF-kB signalling. Here the authors identify a motif conserved in substrates of canonical and alternative NF-kB pathways which mediates docking to catalytic IKK dimers: they show that phosphorylation of the conserved tyrosine suppresses the docking interaction.

Introduction

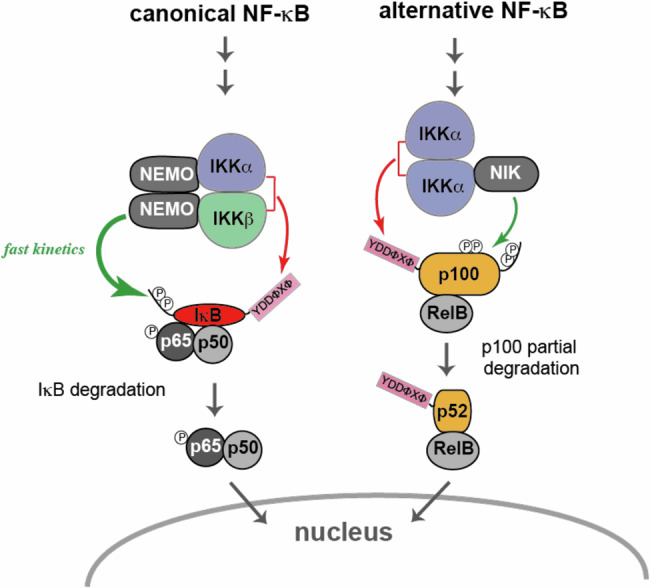

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling plays a central role in the regulation of cellular inflammatory, immune, and apoptotic responses1. Under homeostatic conditions, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm by interaction with inhibitor of κB (IκB) proteins or with the NF-κB precursor proteins p100 and p105. Receptor stimulation of the ‘canonical’ NF-κB pathway activates the inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK), which, in turn, phosphorylates IκB proteins. This results in the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IκB and subsequent nuclear translocation of p65/p50 NF-κB dimers2. Stimulation of the ‘alternative’ NF-κB pathway leads instead to IKK-mediated phosphorylation of p100, which triggers partial degradation of p100 into the mature p52 NF-κB subunit2.

Different IKK complexes (collectively referred to as IKKs hereafter) exist in cells and exhibit variable subunit composition. The core of the canonical IKK complex comprises a heterodimer of the catalytic IKKα/1 and IKKβ/2 subunits (named IKKα and IKKβ hereafter) and two copies of the regulatory NEMO subunit3–5. Whereas IKKα contributes to kinase activation by phosphorylating the IKKβ activation loop6, the IKKβ subunit directly phosphorylates a phospho-dependent DpSGxxpS/T βTrCP degron motif (where pS or pT are phosphoserine or phosphothreonine and x is any amino acid) of IκB proteins7. Upon phosphorylation, this motif is bound by the βTrCP-containing subunit of the SCF E3 ligase complex, leading to polyubiquitination and degradation of IκB proteins8. In contrast, the core of the complex acting in the alternative pathway consists of a homodimer of IKKα9,10.

Seminal work on the IKKα and IKKβ homodimers has revealed striking structural similarities, which are linked to the high sequence homology between these two subunits11–14. Both subunits share an identical architecture, which comprises an N-terminal kinase domain (KD), a ubiquitin-like domain (ULD), a helical scaffold dimerization domain (SDD), and a C-terminal NEMO binding domain. Dimerization is essentially mediated by the C-terminal portion of the SDD domain. For both IKKα and IKKβ, multiple dimer conformations have been observed, which differ in the extent of splaying apart of the KD-ULD portions. Such conformations are thought to be related to kinase activity. In particular, it has been proposed that an ‘open’ state of the dimer permits higher order oligomerization, which, in turn, contributes to kinase activation through a trans-autophosphorylation mechanism12,13.

NEMO is an obligate scaffolding protein15, consisting of an N-terminal region exhibiting high affinity for IKKβ, an extensive central coil-coil interspersed by disordered segments, and a C-terminal zinc-finger domain16,17. NEMO mediates activation of the canonical IKK complex by binding to polyubiquitin chains (polyUb) via its NOA/UBAN motif and the C-terminal zinc finger18–20. Recent studies have shown that multivalent NEMO/polyUb interactions drive the in vivo formation of lattice structures of IKK displaying liquid-like droplet properties, which are associated with IKK activation21,22.

The canonical complex is the most abundant IKK species in cells in stimulated conditions. However, IKKα and IKKβ also act as part of different IKKs on a variety of substrates involved in key cellular functions23. In particular, IKKα homodimers play important roles in the nucleus by phosphorylating transcription factors such as IRF724, co-activators, and co-repressors, including SMRT, CBP, SRC-3 (25 and references therein), and histone H326,27. IKKβ has instead been shown to act on several tumor suppressor pathways, including FOXO3a, TSC1, and p53 (25 and references therein).

Many kinases achieve high specificity by docking interactions that involve the recognition of Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs), which are distinct from the substrate motif recognized by the active site of the enzyme28. The NEMO subunit has been reported to interact with the IκBα substrate protein via its C-terminal zinc-finger domain15. However, since NEMO is not present in the alternative IKK complex, additional mechanisms must exist to mediate substrate recruitment to the kinase. In this work, we describe the identification and characterization of a SLiM that mediates docking of IKKα/β dimers to partner proteins in NF-κB signaling.

Results

IKKα and IKKβ dock to a YDDΦxΦ motif within IκBα

IκBα, the canonical substrate of IKK, comprises a disordered N-terminal region, which contains phospho-Ser32 and phospho-Ser36 residues that are part of the DpSGxxpS/T βTrCP degron motif, an ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) and a disordered C-terminal region containing a PEST sequence (Fig. 1a). To identify the IκBα region interacting with the IKKβ subunit, we performed in vitro pulldown experiments employing recombinant purified proteins. We produced IκBα constructs fused to the C-terminus of the maltose binding protein (MBP) and a nearly full-length (residues 1-669) and constitutively active (S177E/S181E) mutant construct of human IKKβ (named IKKβ(1-669) EE hereafter), which resembles the previously crystallized fragment of this protein12,14. The IKKβ homodimer was purified by affinity and size exclusion chromatography (see Methods section).

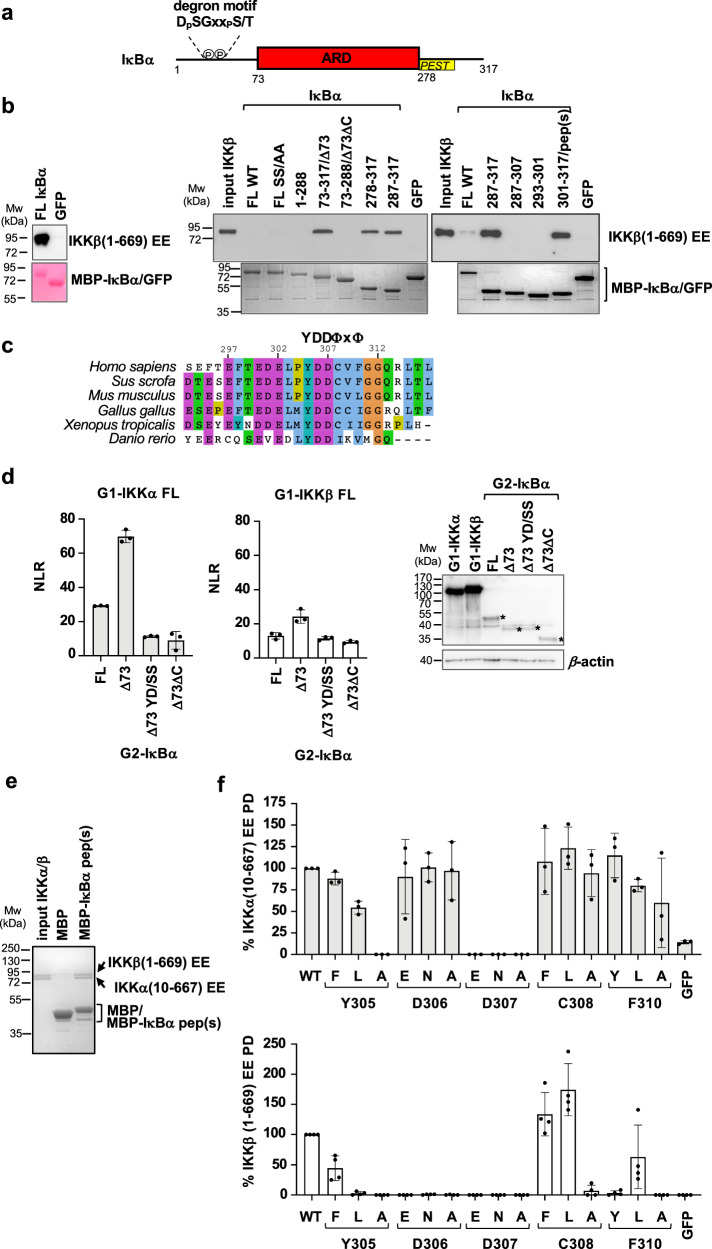

Fig. 1. IKKα and IKKβ interactions with the YDDΦxΦ motif of IκBα.

a Domain architecture of IκBα. N-terminal region containing substrate degron motif (residues 1-72); ARD: ankyrin repeat domain (residues 73-278); C-ter region containing the PEST sequence (residues 278-317). b Pulldown analyzes using 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE and MBP-IκBα constructs coupled to amylose resin. The IKKβ concentrations were adjusted to 5 μM (left panel) or to 0.4 μM (right panel). MBP-GFP: negative control. (Left panel) Samples were migrated on two separate 10% SDS-PAGE gels, to detect IKKβ by Western blot (anti-His antibody) and MBP-IκBα by Coomassie staining, respectively. IκBα constructs 73–317, 73–288, and 301–317 are named Δ73, Δ73ΔC and pep(s), respectively. These interactions were reproduced in a second independent pulldown experiment. c Sequence alignment of residues 293-317 of human IκBα highlighting the YDDΦxΦ consensus. d (Left and middle panels) Representative GPCA datasets for the interactions of full-length wt IKKα and IKKβ proteins with IκBα constructs in HEK293T cells. IKK and IκBα constructs were fused to the G1 and G2 fragments of the luciferase, respectively. YD/SS: Y305S/D307S mutation in IκBα. NLR: normalized luminescence ratio (see methods section). The data (mean +/− SD) are derived from three independent transfection experiments. (Right panel) Western blot analysis of the expression levels of G1-IKKα, G1-IKKβ, and G2-IκBα (indicated by asterisks) constructs in HEK293T cells using an anti-luciferase antibody. e Pulldowns using purified IKKα/β heterodimer (reconstituted from 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE and Strep-IKKα(10-667) EE constructs) and MBP-IκBα pep(s) or MBP negative control. IKK and MBP-fusion proteins were visualized by Coomassie stain. f Results from pulldown analyzes of the interactions of 6xHis-IKKα(10-667) EE (upper panel) or 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE (lower panel) with MBP-IκBα pep(s) mutants. Three single amino acid substitutions were tested for each conserved position of the YDDΦxΦ consensus. IKKα or IKKβ bands were quantified and the data normalized to the interactions of IκBα pep(s) wt to IKKα or IKKβ (100%). For each panel, all interactions were processed in parallel (see Source Data file). The data (mean +/− SD) are derived from three (n = 3, upper panel) or four (n = 4, lower panel) independent pulldown experiments. See also Supplementary Fig. 1b, c for gel images. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The interaction of the IKKβ homodimer with full-length IκBα becomes clearly visible at relatively high concentrations of IKKβ (Fig. 1b, compare left panel - 5 μM of IKKβ - with right panel - 0.4 μM of IKKβ). Unexpectedly, deletion of the N-terminal region of IκBα enhances binding to IKKβ (Fig. 1bright panel, compare FL IκBα with IκBα(73-317), which is named IκBαΔ73 hereafter). In contrast, further deletion of the C-terminal region abolishes the interaction (Fig. 1bright panel, compare IκBαΔ73 with IκBα(73-288), which is named IκBαΔ73ΔC hereafter). Subsequent dissection of the C-terminus of IκBα identified a 17 amino acid peptide (residues 301-317 of IκBα, named IκBα pep(s) hereafter), which is necessary and sufficient for interaction with IKKβ at levels comparable to the N-terminal truncated construct (Fig. 1bright panel, compare IκBαΔ73 with IκBα pep(s)). Serine mutagenesis of IκBα pep(s) indicates that Tyr305, Asp306, Asp307, Cys308 and Phe310 residues are essential for the interaction with IKKβ (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Consistently, sequence alignments (Fig. 1c) reveal that these residues are conserved in IκBα proteins from different species and are part of a motif with a Y1D2D3Φ4x5Φ6 consensus (where Y is a tyrosine, D is an aspartic acid, Φ is a hydrophobic amino acid and x is any amino acid). This motif is flanked on the N-terminal side by a patch of acidic residues (residues 297-302) that are conserved across species.

Next, we analyzed IKK interactions with IκBα in cellulo using the Gaussia princeps protein complementation assay (GPCA)4. Here, full-length IKKα or IKKβ proteins and IκBα constructs were fused to the C-terminal extremities of the G1 and G2 fragments of the Gaussia luciferase, respectively. Pairwise combinations of G1-IKKα or G1-IKKβ and G2-IκBα were then co-transfected in HEK293T cells and the interactions monitored following the activity of the reconstituted luciferase. We found that both IKKα and IKKβ interact with full-length IκBα, with IKKα showing higher binding responses (Fig. 1d). In line with the pulldown results, truncation of the N-terminal region of IκBα again enhances binding to both IKKα and IKKβ (Fig. 1d, compare IκBα FL with IκBαΔ73). A possible explanation for this finding might be a steric hindrance effect of the N-terminal region of IκBα occurring when the p50/p65 NF-κB dimer is not bound to the ARD domain, a mechanism which may be related to the previously observed ability of IKK to discriminate between free and NF-κB bound IκBα substrate29. In contrast, further deletion of the disordered C-terminal region or the double serine substitution at positions Y1 and D3 of the motif (i.e. Y305S/D307S, named YD/SS hereafter) strongly decreases the interactions to both IKK homodimers (Fig. 1d, compared IκBαΔ73 with IκBαΔ73ΔC and IκBαΔ73 YD/SS).

We then proceeded to reconstitute the IKKα/β heterodimer by co-expression of 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE and Strep-IKKα(10-667) EE constructs in insect cells and purification by two consecutive affinity-chromatography steps (Ni2+-NTA and Strep-Tactin) plus gel filtration (see Methods section). The results from MBP-pulldown analyzes show that the IKKα/β heterodimer specifically binds to IκBα pep(s) (Fig. 1e).

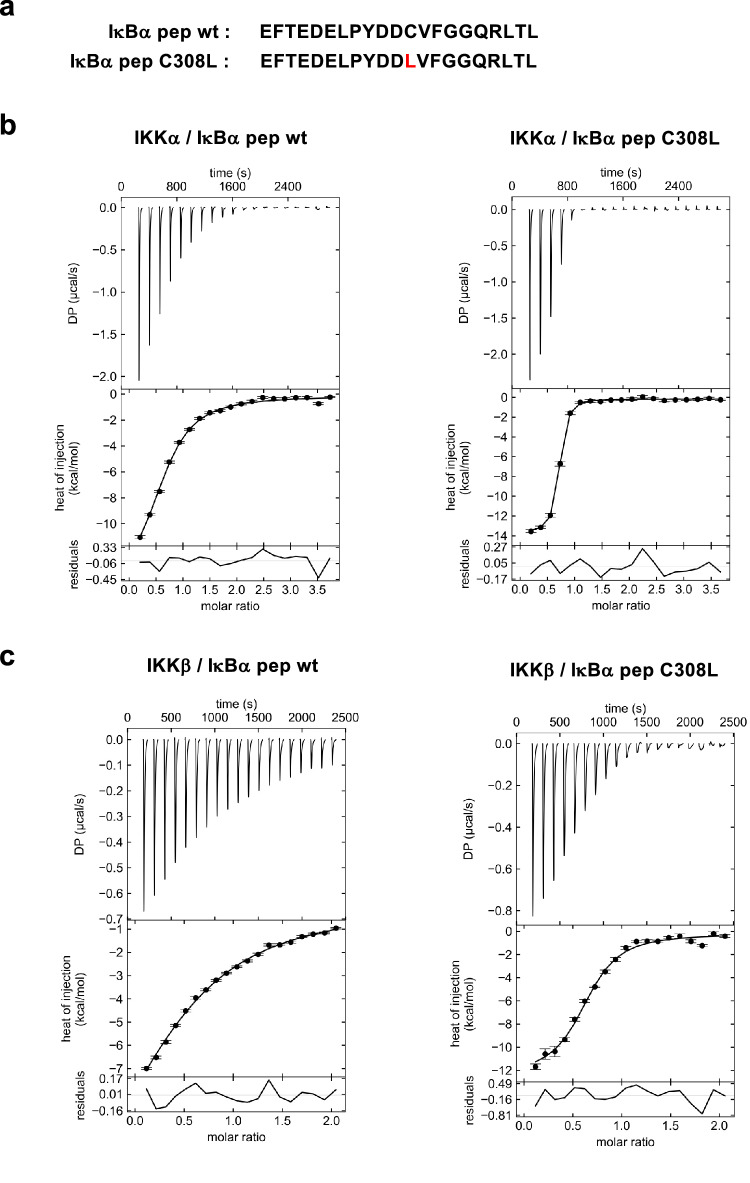

To evaluate binding affinities, we performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments using a synthetic peptide that comprises the YDDΦxΦ motif plus the N-terminal acidic patch (residues 297-317, named IκBα pep hereafter, Fig. 2a) and purified IKKβ(1-669) EE homodimer or an equivalent construct of the IKKα homodimer (i.e. IKKα(10-667) S176E/S180E13, named IKKα(10-667) EE hereafter). The results indicate significantly higher affinity for the interaction with IKKα (KD = 7.7 μM) as compared to IKKβ (KD = 40 μM) (Table 1 and Fig. 2b, c). In contrast, ITC analyzes on the IKKα/β heterodimer were prevented by strong sample aggregation at the concentrations required for these experiments.

Fig. 2. ITC analysis of the IKKα and IKKβ interactions with IκBα pep.

a Sequences of the IκBα pep wt and C308L synthetic peptides. b, c Representative ITC binding isotherms for the indicated interactions. The experiments used purified IKKα(10-667) EE or IKKβ(1-669) EE proteins at concentrations between 22 and 50 μM, depending on the experiment, and peptide concentrations were adjusted accordingly (i.e. between 220 and 975 μM). DP: differential power. The data were analyzed by global fitting (see Table 1). The residuals are calculated as differences between fitted and experimental values, whereas the error bars correspond to the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of the fitted and measured injection data as implemented in SEDPHAT61. Each interaction was measured in at least two independent ITC titration experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of IKKα or IKKβ binding to YDDΦXΦ peptides

| interaction | N | KD (μM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKKα / IκBα pep wt | 0.63 | 7.7 (6.5, 9.4) | −14.2 (−15.5, −13.2) | −7.23 | −6.97 |

| IKKα / IκBα pep C308L | 0.65 | 0.42 (0.33, 0.55) | −13.7 (−14.1, −13.4) | −5.01 | −8.69 |

| IKKα / pY-IκBα pep | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| IKKβ / IκBα pep wt | 0.63 | 40 (35, 46) | −16.3 (−19.3, −14.2) | −10.3 | −6.00 |

| IKKβ / IκBα pep C308L | 0.66 | 2.4 (1.7, 3.1) | −11.5 (−12.1, −10.8) | −3.83 | −7.67 |

| IKKα / p100 pep | 0.60* | 12** (3.5, 18) | −13.4** (−17.2, −8.30) | −6.69 | −6.71 |

| IKKα / IRF7 pep | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

All ITC experiments were performed at 25 °C. The data were fitted to a 1:1 binding model. N refers to the binding stoichiometry of IKKα/β: pep. Data were processed using the NITPIC software60. For each interaction, the thermodynamic parameters were derived from the global fitting of two independent titration curves (n = 2) using the SEDPHAT software61. For the best-fit values of KD and ΔH, a confidence interval at 68.3% probability (one SD assuming a Gaussian error distribution) was calculated (in brackets) using error surfaces prescribed by F-statistics.

*value constrained during fitting.

**broad confidence intervals correspond to poor convergence, therefore, for this titration fitted values should be considered as estimates.

N.D. not determined.

In the next step, we introduced single amino acid substitutions at the conserved positions of the motif of IκBα pep(s) (i.e. Y1, D2, D3, Φ4 and Φ6) and evaluated the impact on the interactions with purified IKK homodimers. Most of the mutations have a negative effect on the interactions with IKKβ, whereas IKKα appears to tolerate a higher number of substitutions, particularly at positions Y1, D2 and Φ6 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). In contrast, two substitutions at the Φ4 position, i.e. C308L and C308F, appear to enhance binding to IKKβ (Fig. 1flower panel). Consistently, ITC analyzes show that the C308L substitution increases IκBα pep affinities to both IKKα and IKKβ, by aproximately 20- and 15-fold, respectively (KD = 420 nM for IKKα and KD = 2.4 μM for IKKβ) (Table 1 and Fig. 2b, c).

Together, these results demonstrate that homo- and heterodimers of the catalytic IKKα and IKKβ subunits dock to a YDDΦxΦ motif located in the C-terminal region of the IκBα substrate. This is in agreement with binding data from Xu and coworkers11, who suggested the existence of an exosite for IKKβ within the C-terminal region of IκBα11. Based on our findings, the motif seems to have significantly higher affinity for IKKα compared to IKKβ. Finally, amino acid replacements within the motif’s consensus enable us to modulate the affinity of the interaction in both positive and negative ways.

Docking affinity correlates with IKK activity

We assessed the impact of the docking interaction on IKK activity. To mimic in vivo conditions as previously described15, we performed in vitro kinase experiments in the presence of high concentrations of a nonspecific competitor protein (BSA), limiting concentrations of purified full-length wt or mutant IκBα proteins and endogenous canonical IKK that was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells using an anti-NEMO antibody. The results show that Ser32/Ser36 phosphorylation is highest for the IκBα C308L mutant with improved docking affinity, whereas IκBα YD/SS is not phosphorylated under these assay conditions (Fig. 3a). Similar results were obtained using recombinant purified IKKβ(1-669) EE instead of the endogenous canonical complex (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

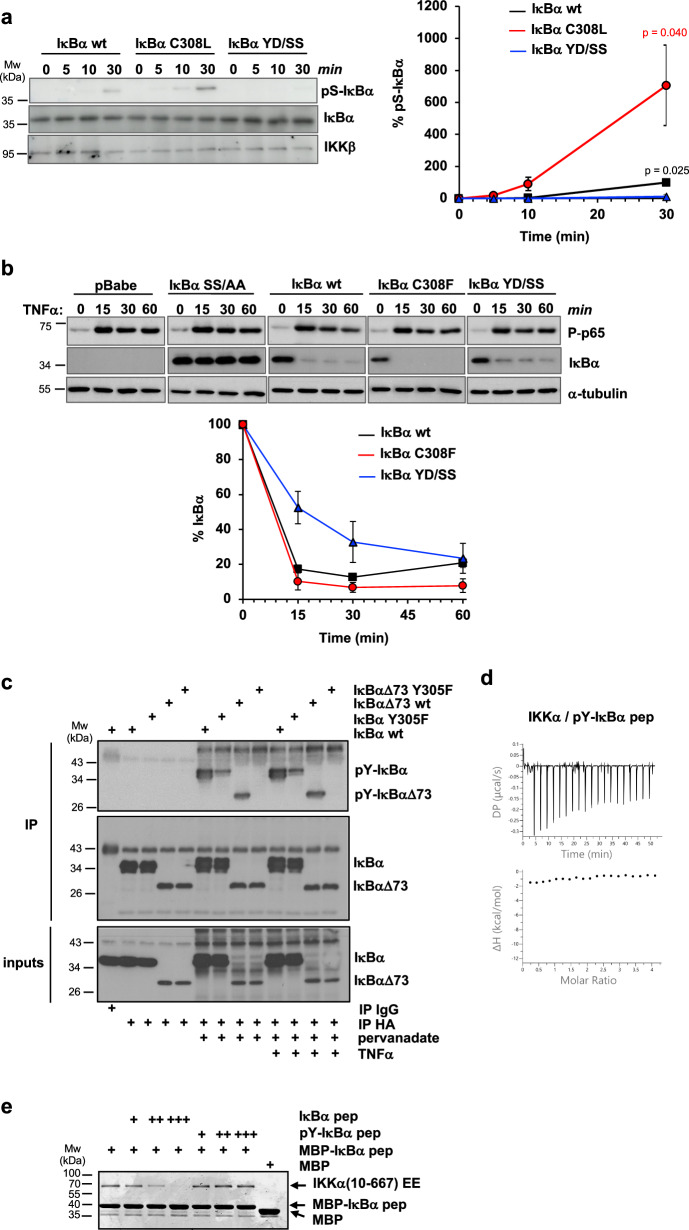

Fig. 3. Functional analyzes on the YDDΦxΦ docking interaction.

a In vitro kinase activity experiments using purified full-length 6xHis-IκBα proteins and endogenous IKK immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells. Aliquots of the reactions were taken at the indicated time points and immunoblotted using anti-His (IκBα), anti-phospho-Ser32/Ser36 IκBα (pS-IκBα) and anti-IKKβ (IKKβ) antibodies. Samples were run on two separate 10% SDS-PAGE gels for detection of total IκBα and pS-IκBα. (Left panel) Representative Western blot images. (Right panel) Quantification of pS-IκBα levels normalized to IκBα at 30 min (100%). The data (mean +/− SD) are obtained from three independent kinase activity experiments. The indicated P-values (p) are obtained from a two-tailed unpaired t-test, n = 3 biological triplicates. Black: differences between IκBα YD/SS and IκBα wt; red: differences between IκBα C308L/F and IκBα YD/SS. b In cellulo degradation of retro-transduced IκBα proteins in MEF cells KO for IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε. Cells were stimulated with TNFα (20 ng/ml) and collected at the indicated time points. Cellular extracts were immunoblotted using anti-IκBα (IκBα) and phospho-specific p65 (P-p65) antibodies. IκBα SS/AA: IκBα S32A/S36A. (Upper panel) Western blot images. Each IκBα mutant was migrated together with wt IκBα on the same gel (see Source Data file). (Lower panel). Quantification of IκBα levels normalized first to tubulin and, then, to the IκBα values at time 0 (100%). The data (mean +/− SD) are obtained from three measurements, with bars reporting on the quantification error. Similar IκBα degradation profiles were obtained in a second independent experiment. c Detection of IκBα tyrosine phosphorylation in HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated HA-tagged IκBα constructs, incubated, or not, with pervanadate (1 mM) for 30 min and stimulated, or not, with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 15 minutes before collection. Cleared lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA beads, and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-Tyr (pY-IκBα and pY-IκBαΔ73) and anti-HA (IκBα and IκBαΔ73) antibodies. The results were reproduced in a second independent experiment. d ITC data on the IKKα interaction with synthetic phospho-Tyr305 IκBα pep (pY-IκBα pep). e Competition MBP-pulldown experiment using 6xHis-IKKα(10-667) EE, MBP-IκBα pep coupled to amylose resin and an excess of synthetic IκBα pep or pY-IκBα pep peptides. IKKα : (pY-)IκBα pep stoichiometric ratios: 1:100 ( + ), 1:200 ( + + ); 1:500 (+++). Samples were migrated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and stained by Coomassie. These results were reproduced in a second independent pulldown experiment. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

We also evaluated the degradation profiles of wt or mutant IκBα proteins upon activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway. In these experiments, IκBα constructs are retro-transduced in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) lacking IκB family genes (MEF IκBα/IκBβ/IκBε KO) and their protein levels monitored at selected time points after TNFα stimulation. As expected, the S32A/S36A (SS/AA) mutation targeting phospho-acceptor residues completely suppresses IκBα degradation, as evidenced by the lack of change in IκBα levels following TNFα stimulation (Fig. 3b). Mutations at the YDDΦxΦ docking motif have milder effects on IκBα levels. The degradation of the IκBα YD/SS mutant appears to be slower, whereas the degradation of the higher affinity IκBα C308F mutant, which is used here due to the low expression levels of IκBα C308L in MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2b), is slightly faster compared to that of the wt IκBα protein (Fig. 3b).

Taken together, these results show that the affinity of the docking interaction correlates with both phosphorylation and degradation of the IκBα substrate. Yet, the residual degradation activity of the IκBα YD/SS mutant observed here indicates that additional determinants contribute to substrate recruitment, which may involve the NEMO interaction with IκBα15.

Docking is negatively regulated by a phosphorylation switch

The Y1 (Tyr305) position of the docking motif is a strictly conserved tyrosine (Fig. 1c), which suggests that it may be a target of phosphorylation. To explore this possibility, HA-IκBα and HA-IκBαΔ73 proteins transiently expressed in HEK293T cells were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-phospho-Tyr antibody. Results show that tyrosine phosphorylation of IκBα becomes detectable only when cells are treated with the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) inhibitor pervanadate (Fig. 3ctop and middle panels, compare pY-IκBα and pY-IκBαΔ73 bands). Remarkably, the conservative Y305F mutation reduces phosphorylation in full-length IκBα, while it completely suppresses it in the IκBαΔ73 construct, indicating that Tyr305 is the only phosphorylated tyrosine between residues 73 and 317 of IκBα under steady-state conditions (Fig. 3c top panel, lanes 6–7, and 8–9). On the other hand, TNFα stimulation does not appear to induce degradation of full-length IκBα, indicating that the pervanadate treatment impairs activation of the canonical pathway (Fig. 3c, lanes 10-13 of top and bottom panels and Supplementary Fig. 2c), and thereby preventing us from evaluating the phosphorylation state of Tyr305 during NF-κB signaling.

We thus investigated the impact of Y1 phosphorylation on docking by ITC, by titrating the IKKα homodimer, which displays higher affinity for the YDDΦxΦ motif as compared to IKKβ, with a synthetic phospho-Tyr305 IκBα pep (named pY-IκBα pep hereafter) peptide. The enthalpy (ΔH) term obtained is zero, which suggests an absence of interaction (Fig. 3d). To rule out the possibility that the zero ΔH value is accidental (i.e. arising as a consequence of the van’t Hoff rule), we performed MBP-pulldown experiments in the presence of increasing concentrations of competitor synthetic peptides. Whereas IκBα pep competes with MBP-IκBα pep for binding to IKKα, phosphorylated pY-IκBα pep does not appear to affect the IKKα/MBP-IκBα pep interaction (Fig. 3e).

To conclude, we demonstrate that phosphorylation at Y1 (Tyr305) drastically diminishes the binding affinity for IKK dimers. This position is phosphorylated under steady-state conditions. Interestingly, an independent study reported that Tyr305 phosphorylation is enhanced upon genotoxic stress and that this leads to IκBα accumulation and, consequently, inhibition of NF-κB gene expression30. Together, these findings suggest that a phosphorylation switch at Y1 may serve as a safeguard mechanism to prevent unwanted substrate phosphorylation of the N-terminal βTrCP degron motif of IκBα.

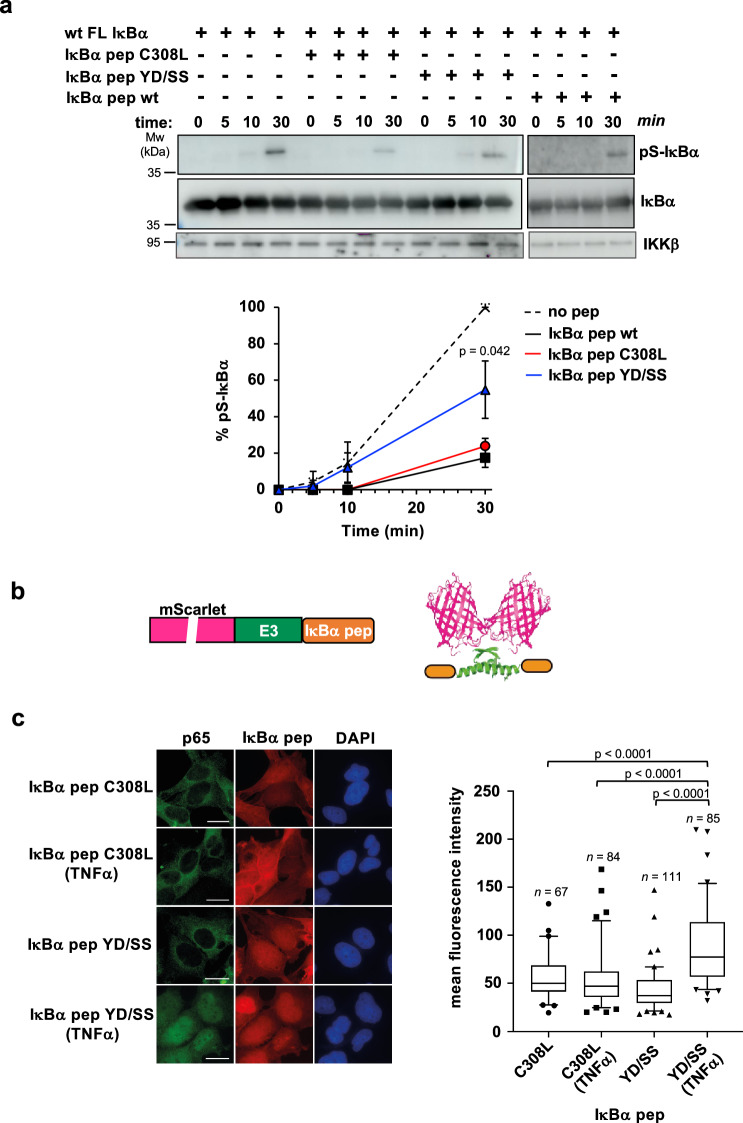

YDDΦxΦ motif-containing peptides inhibit NF-κB signaling

The MBP-IκBα pep fusion comprising the C308L mutation is able to capture endogenous IKKβ from clarified extracts of HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a). This raises the possibility that docking motif peptides could act as competitive inhibitors of IKK-substrate interactions. Consistently, results from in vitro kinase experiments performed in the presence of synthetic IκBα pep variants indicate that both wt and C308L peptides inhibit IκBα phosphorylation more efficiently than the YD/SS negative control peptide (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Inhibition of canonical NF-κB signaling by IκBα pep.

a In vitro inhibition of IKKβ kinase activity by synthetic IκBα pep variants. The experiment uses full-length wt 6xHis-IκBα, endogenous IKK, and an excess of synthetic IκBα pep variants. Samples were run on two separate gels for detection of total IκBα and pS-IκBα. See also legend of Fig. 3a. (Upper panel) Representative Western blot images. All different IκBα pep conditions were migrated with the reference (no peptide) on the same gel (see Source Data file). (Lower panel) Quantification of IκBα phosphorylation levels normalized to the values obtained in the absence of peptide (no peptide) at 30 minutes incubation (100%). The data (mean +/− SD) are obtained from three independent kinase activity experiments. The indicated P-value (p) was obtained from a two-tailed unpaired t-test, n = 3 biological triplicates and reports on differences between IκBα pep YD/SS and IκBα pep wt at t = 30 min. b Schematic representation of mScarlet-E3-IκBα pep constructs. Purple: mScarlet, green: the E3 dimerization peptide; orange: the IκBα pep sequence. c In vivo inhibition of NF-κB signaling by IκBα pep. (Left panel) Immunofluorescent staining of MRC5 cells electroporated with mRNAs coding for mScarlet-E3-IκBα pep fusions. After electroporation, cells were treated or not with TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 30 minutes before fixation. The translated constructs were detected by direct immunofluorescence of the mScarlet (red). p65 was detected using an anti-p65 antibody followed by an anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488 (green). Nuclei were stained by DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (Right panel) Mean fluorescence intensities of nuclear p65 in the four conditions. The data are displayed in a box-and-whisker representation showing the median in the center line, the 75/25 percentiles at the boxes, the 5/95 percentiles at the whiskers and the extreme values to the minimum and maximum of the raw fluorescence data. Statistical analysis was performed by ordinary one-way ANOVA test. n: number of cells analyzed. See also Supplementary Fig. 3b for quantification of the nuclear expression levels of IκBα pep fusions. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

To improve binding activity for in vivo studies, we created bivalent peptides by fusing the IκBα pep sequence to the E3 tag, a peptide derived from the oligomerization domain of p53, which was engineered to mediate the formation of strong homodimers31. The E3-IκBα pep constructs were appended to the C-terminus of the mScarlet protein for fluorescent detection (Fig. 4b). These mScarlet-E3-IκBα pep fusions were then transfected as mRNAs into human fetal lung fibroblast (MRC-5) and activation of canonical NF-κB signaling was monitored by following nuclear translocation of p65. As expected, in unstimulated conditions p65 is found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4cleft panel). Upon TNFα induction, p65 translocates into the nucleus only in the case of the fusion containing the IκBα pep YD/SS negative control sequence, whereas the IκBα pep C308L sequence efficiently retains p65 in the cytoplasm at levels comparable to the unstimulated condition (Fig. 4cleft and right panels and Supplementary Fig. 3b).

These results provide evidence that the docking mechanism is active during signaling and that it can be blocked by YDDΦxΦ peptides leading to inhibition of the canonical NF-κB pathway.

Structural studies of the IKKβ/IκBα pep complex

We carried out several crystallization screenings on samples of IKKα or IKKβ homodimers bound to synthetic IκBα pep wt or C308L peptides. Most crystals obtained displayed poor x-ray diffraction patterns, reflecting previously reported difficulties linked to high-resolution structural studies on these dimers13. Nevertheless, we were able to identify one crystal grown from a sample of IKKβ(1-669) EE mixed with wt IκBα pep, which diffracted synchrotron radiation to a resolution of 4.15-6.8 Å (anisotropic diffraction, see Supplementary Table 1), allowing for structure determination by molecular replacement. The asymmetric unit of the crystal contains five IKKβ protomers. Four protomers form two distinct homodimers (A-B and C-D) with the characteristic “scissor-like” structure mediated by contacts involving the C-terminal portions of the SDD domains (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). The fifth protomer of the unit cell homodimerizes with its symmetry equivalent molecule from a neighboring asymmetric unit. The conformations of the A-B and C-D homodimers differ in the extent of the splaying apart of the KD-ULD portions, with the A-B homodimer displaying a relatively ‘closed’ conformation compared to the C-D homodimer (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). B-factor analysis indicates lower flexibility for the helices of the SDD domain in the A-B homodimer than in the C-D homodimer (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

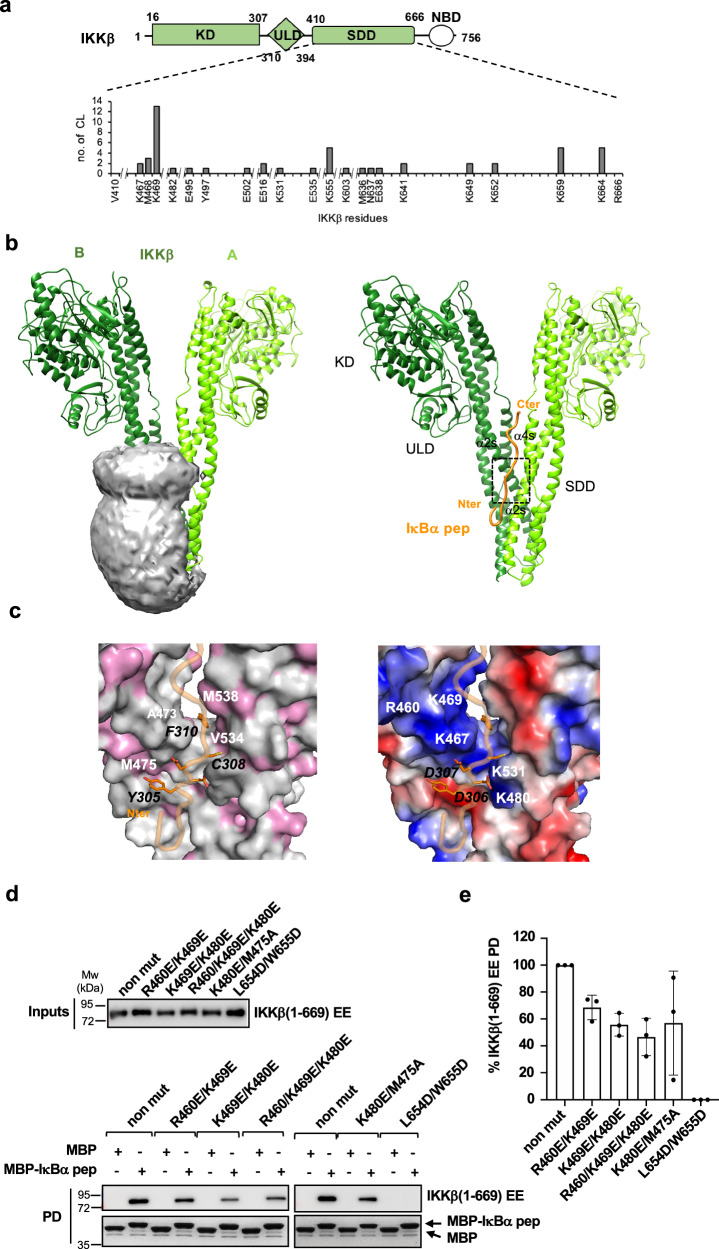

Fig. 5. Structural analyzes of the IKKβ/IκBα pep interaction.

a (Upper panel) Architecture of IKKβ. Green: KD, ULD and SDD domains present in the IKKβ(1-669) EE construct; white NEMO binding domain (NBD). (Lower panel) SDD residues involved in cross-links (CL) with the IκBα pep peptide. Y axis: total number of links obtained with the three cross-linkers (EDC/NHS, BS3 and sulfo-SDA). b (Left panel) The volume accessible to IκBα pep for interaction with IKKβ calculated using the CLMS data and the DisVis program34. The gray mesh indicates the center-of-mass position of IκBα pep, while protomers A and B of the IKKβ dimer crystal structure are shown in the ribbon representation in light and dark green, respectively. (Right panel) Best model of the IKKβ/IκBα pep complex obtained using the x-ray A-B IKKβ dimer structure and CLMS derived distance restraints for docking of IκBα pep (orange). The dashed box positions the YDDΦxΦ motif. Images were made using the UCSF Chimera software74. c Molecular views of the complex interface showing IKKβ and IκBα pep in the surface and ribbon representation, respectively. Side-chains of conserved YDDΦxΦ residues are displayed and indicated by black labels. IKKβ interface residues are indicated by white labels. (Left panel) Surface hydrophobic residues of IKKβ (pink). (Right panel) Surface charge potential of IKKβ. Blue: positive charge; red: negative charge. d Pulldown analyzes of the interactions between recombinant purified IKKβ mutants and MBP-IκBα pep(s). non mut: 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE without additional mutations. (Upper and lower panels) Representative gel images. IKKβ proteins were detected by Western blot (anti-His antibody), while MBP-IκBα pep(s) by Coomassie staining. See also legend of Fig. 1b. e Quantification of pulldown analyzes. The IKKβ band intensities were normalized to 100% for the reference protein (i.e. non mut IKKβ). The data (mean +/− SD) are derived from three independent experiments (n = 3). Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

Whereas our data recapitulate previously observed structural features of IKKβ, we were unable to clearly observe electron density for the IκBα pep ligand due to the lack of high resolution. We therefore turned to cross-linking mass spectrometry (CLMS)32 to independently map the binding site of IκBα pep on IKKβ. For this, purified IKKβ(1-669) EE was mixed with a 10-fold molar excess of synthetic IκBα pep C308L/R314K, which incorporates an additional Arg to Lys substitution to improve peptide cross-linking efficiency. Protein samples were cross-linked using three distinct agents with different chemistries and spacer lengths: EDC/sulfo-NHS, sulfo-SDA and BS3. Protein-peptide cross-linked species were isolated by migration on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c) and analyzed by MS.

Despite the large excess of peptide added, the totality of the intermolecular IKKβ-peptide cross-links identified in the different samples map to the SDD domain of IKKβ, strongly supporting the specificity of this interaction (Fig. 5alower panel and Supplementary Fig. 5d). This finding is also in line with a previous study showing that a construct of the isolated SDD domain of IKKβ is sufficient for interaction with IκBα11. EDC/sulfo-NHS, a zero-length cross-linker catalyzing amide bond formation, provided 10 cross-links mostly involving Glu or Asp residues of the N-terminal acidic patch of IκBα pep and Lys residues of the dimerization region of IKKβ (Supplementary Fig. 5dupper panel). Consistently, the long-range BS3 cross-linker identified 5 amine-to-amine links between the peptide’s N-terminus and the same Lys residues (Supplementary Fig. 5dmiddle panel), thereby confirming the proximity of the N-terminal acidic patch of IκBα pep to the IKKβ dimerization region. Sulfo-SDA, a short spacer (3.9 Å) cross-linker that conjugates primary amines or hydroxyls with any amino acid group after UV photoactivation33, provided 26 links (Supplementary Fig. 5dlower panel).

Topological analysis of the CLMS data using the DisVis tool34 indicates that the volume accessible to IκBα pep for interaction with IKKβ is consistent with a binding interface, which involves the dimerization and middle regions of the two adjacent SDD domains of the IKK dimer (Fig. 5bleft panel). Many of the identified cross-links map to IKKβ residues Lys467-Met468-Lys469 (Fig. 5alower panel). Consistently, after careful inspection of the x-ray data we were able to identify a small lobe of extra electron density in the proximity of these residues in the ‘closed’ A-B homodimer (Supplementary Fig. 4b), which suggests that IκBα pep might be bound at this site but not entirely visible at this resolution.

In the next step, we calculated a model of the IKKβ/IκBα complex. Unbound IκBα pep appears to be mostly random coil in solution (Supplementary Fig. 6). This peptide was docked in an extended conformation to the IKKβ A-B homodimer crystal structure using CLMS-derived distance restraints and the HADDOCK software (Fig. 5bright panel). Eight acceptable clusters were obtained based on the HADDOCK score and interface root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In all clusters, IκBα pep binds to the two adjacent SDD domains of the IKKβ homodimer, with the YDDΦxΦ motif accommodated in a groove contributed by helices α2s and α4s from protomer A, and α2s from protomer B of the SDD middle portions (Fig. 5bright panel and Supplementary Fig. 7b). Structural alignment of the models shows high precision for most of the clusters, with mean within-cluster interface RMSD values ranging between 1.3 and 1.8 Å. (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The best model from the cluster with the lowest HADDOCK score (cluster 1) is chosen as a representative model (Supplementary Data 1). Overall CLMS distance restraints are in good agreement with this final model (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Most over-length cross links involve flexible residues at the N-terminus of IκBα pep (Glu 297 and Phe298) and of the C-terminus of IKKβ (Lys659 and Lys 664), and likely reflect disorder and/or the capturing of transient oligomeric interactions (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d).

The YDDΦxΦ binding groove is dominated by polar and positively charged residues, with a few hydrophobic contributions observed in the proximity of the Y1 (Tyr305), Φ4, (Cys308) and Φ6 (Phe310) positions of the motif (Fig. 5c). Specifically, whereas Tyr305 makes stacking interactions with Met475 of IKKβ, Cys308 and Phe310 are inserted in a cavity contributed by Ala473, Val530, Val534 and Met538 of the two adjacent SDD domains of IKKβ (Fig. 5cleft panel). The acidic residues of the motif (Asp306 and Asp307) are instead stabilized by a positively charged patch comprising Lys467, Lys480 and Lys531 of IKKβ (Fig. 5c, right panel). Several residues lining the YDDΦxΦ groove are conserved across species in both IKKα and IKKβ, whereas the positively charged surface contacting the N-terminal acidic patch of the IκBα pep appears to be more variable (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Based on the structural model, we designed IKKβ mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9a) and evaluated their interactions with the IκBαΔ73 and IκBα pep(s) constructs by the GPCA and pulldown assays, respectively. Strikingly, the L654D/W655D mutation in the C-terminal portion of the SDD domain, previously reported to suppress IKKβ dimerization12, completely abolishes binding to IκBα in both assays, thereby providing evidence that an intact dimer is required for the interaction with the substrate (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). This is in line with previous results, showing that this mutation markedly reduces IKKβ-mediated phosphorylation of the IκBα substrate12. In addition, we also identified single amino acid substitutions introducing charge reversal (K469E and K480E) or affecting hydrophobicity (M475A) at specific positions of the YDDΦxΦ binding groove, which significantly attenuate the binding response to IκBα (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). The combination of these substitutions in single constructs (K469E/K480E and K469E/M475A) leads to a stronger reduction of binding activity in both assays (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). In contrast, the R460E mutation appears to reduce binding to IκBαΔ73 but not to the IκBα pep(s), suggesting that Arg460 may contribute to interactions involving IκBα residues outside the YDDΦxΦ motif (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). Significant effects are also observed for charge reversal mutations within the C-terminal helix contacting the N-terminal patch of IκBα pep (K641E, R645E, K659E and K664E), suggesting that this interface may provide additional electrostatic contributions (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c).

Together the results described in this section indicate that the YDDΦxΦ motif interacts with a conserved groove at the interface of the IKKβ homodimer.

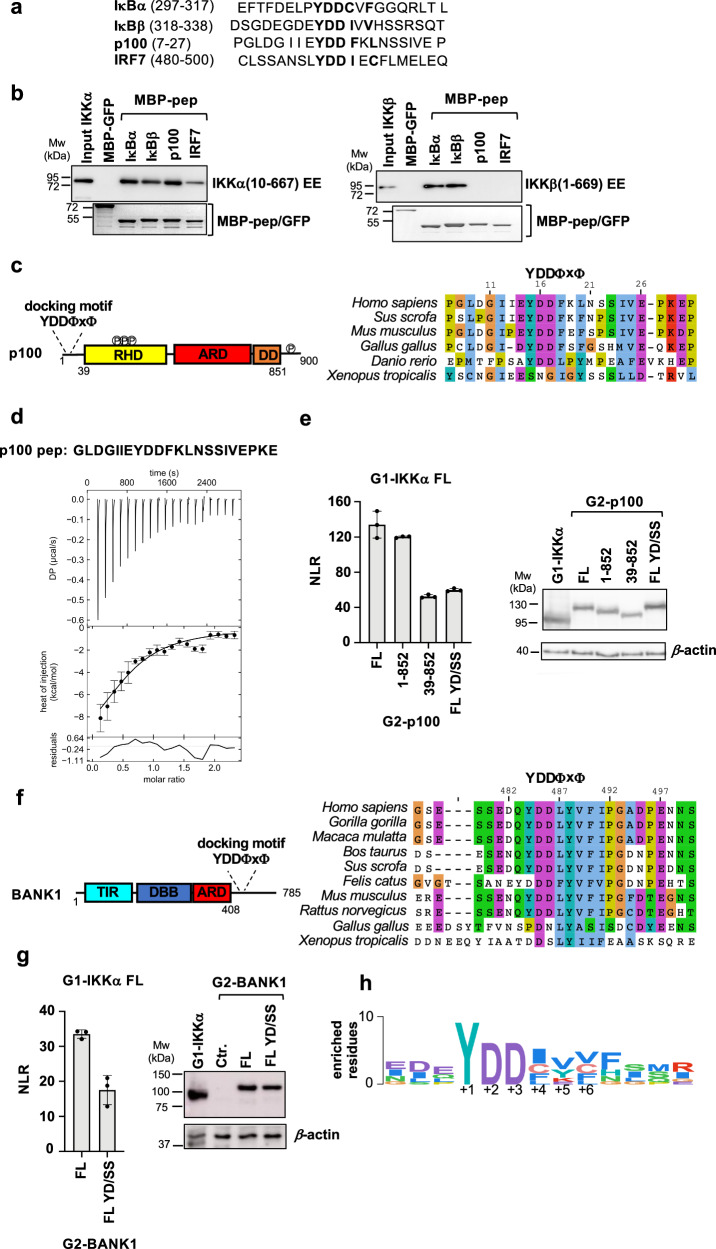

The YDDΦxΦ motif mediates IKK interactions with partner proteins in NF-κB signaling

Proteome-wide bioinformatic analyzes using SLiMSearch35 detected 27 matches with an accessible YDDΦxΦ consensus (YDD[MILVCF].[MILVCF]) (Supplementary Data 2). Among these matches we found three proteins annotated to bind to IKKα or IKKβ, namely: IκBβ, a canonical substrate of IKKβ and orthologue of IκBα; p100, the IKKα substrate in the alternative NF-κB pathway; and interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7), which was also reported to be a substrate of IKKα24. We thus designed peptides containing the YDDΦxΦ sequences from these proteins (referred to as IκBβ pep, p100 pep and IRF7 pep hereafter, Fig. 6a) and tested them against recombinant IKKα and IKKβ by pulldown (Fig. 6b). The results show that IKKβ binds uniquely to peptides derived from the catalytic IκB substrates (IκBα pep and IκBβ pep) and not to p100 pep or IRF7 pep. In contrast, all the peptides interact with IKKα.

Fig. 6. The YDDΦxΦ motif in NF-κB signaling partners of IKKs.

a Motif peptide sequences from human IκBα, IκBβ, p100 and IRF7 proteins used in the pulldown experiments shown in (b). b Pulldown analyzes of the interactions between recombinant 6xHis-IKKα(10-667) EE (left panel) or 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE (right panel) proteins and MBP-peptide fusions. IKKα and IKKβ were detected by Western blot (anti-His antibody) and MBP-peptides by Coomassie staining. These results were reproduced in at least two independent pulldown experiments. See also legend of Fig. 1b. c (Left panel) Domain architecture of p100. Disordered N-terminal region containing the YDDΦxΦ motif; RHD: Rel homology domain (residues 38-343) containing IKKα phosphorylation sites; ARD: ankyrin repeat domain (residues 487-758); DD: death domain (residues 764-851); disordered C-terminal region containing IKKα phosphorylation sites. (Right panel) Sequence alignment of residues 7-30 of human p100 showing conservation of the YDDΦxΦ motif. d Representative ITC binding isotherm for the IKKα/p100 pep interaction. The sequence of the synthetic p100 pep peptide is reported at the top. The data were analyzed by global fitting (see Table 1). The interaction was measured in two independent ITC titrations. Error bars correspond to the RMSD of the fitted curve and experimental values. See also legend of Fig. 2. e (Left panel) Representative dataset for the GPCA analysis of the interactions between full-length wt G1-IKKα and G2-p100 proteins. G2-p100 FL YD/SS: G2-p100 FL Y15S/D17S. (Right panel) Expression levels of G1-IKKα and G2-p100 constructs in HEK293T cells. See also legend of Fig. 1d. f (Left panel) Domain architecture of BANK1. TIR: Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance protein domain (residues 25-153); DBB: Dof/BCAP/BANK domain (residues 200-327); ARD: ankyrin repeat domain (residues 342-408); disordered C-terminal region containing the YDDΦxΦ motif. (Right panel) Sequence alignment of residues 475-500 of human BANK showing conservation of the YDDΦxΦ motif in mammalian orthologs. g (Left panel) Representative dataset for the GPCA analysis of the interactions between full-length wt G1-IKKα and G2-BANK1 proteins. G2-BANK1 FL YD/SS: G2-BANK1 FL Y484S/D486S. (Right panel) Expression levels of G1-IKKα and G2-BANK1 constructs in HEK293T cells. Ctr.: non transfected cells. See also legend of Fig. 1d. h Sequence Logo showing the position-specific frequency of amino acids composing the motif in orthologues of IκBα, IκBβ, p100, IRF7 and BANK1. The Logo is based on the PSSM created using the binomial log10 scoring scheme from PSSMSearch (https://slim.icr.ac.uk/pssmsearch/) for the five validated peptides. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The alternative p100 substrate consists of an N-terminal disordered region, followed by a Rel homology domain (RHD), an ankyrin repeat domain (ARD), a death domain (DD) and a disordered C-terminal region (Fig. 6cleft panel). The YDDΦxΦ motif is located in the N-terminal disordered region and is conserved from human to fish (Fig. 6cright panel), whereas the IKKα phosphorylation sites are situated within the RHD and C-terminal regions10. Synthetic p100 pep binds to purified IKKα with an affinity (KD) of approximately 12 μM, which is very similar to that of IκBα pep (Table 1 and Fig. 6d). In vivo GPCA analyzes show that deletion of the C-terminal region of p100 harboring some of the phospho-acceptor residues does not affect IKKα interaction with p100 (Fig. 6e, left panel, compare FL with 1-852). Instead, a double Ser substitution at the Y1 and D3 positions of the docking motif (i.e. YD/SS) or deletion of the motif strongly reduces binding to IKKα (Fig. 6eleft panel, compare FL with FL YD/SS and 39-852).

In IRF7 the YDDΦxΦ motif is conserved in mammalian orthologues and lies within a C-terminal autoinhibitory domain (ID), just downstream of the serine cluster phosphorylated by the TBK1/IKKε kinase (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b)36,37. ITC measurements show that IRF7 pep binds with weak affinity to IKKα (Supplementary Fig. 10c). While we were able to reproduce IRF7 protein binding to IKKα in vivo by GPCA, such interaction is not affected by mutation of the Y1 and D3 motif positions (IRF7 YD/SS in Supplementary Fig. 10d). Since TBK1/IKKε phosphorylation of IRF7 induces major conformational changes in the ID domain of IRFs38, which may enhance motif accessibility, we introduced phosphomimetic mutations in the serine cluster and tested the impact on the IKKα/IRF7 interaction (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The results show no effect of such mutations on the interaction (Supplementary Fig. 10d), suggesting that a mechanism other than TBK1/IKKε phosphorylation may be associated with motif regulation in IRF7.

We also designed peptides from seven other matches with an accessible motif and with a functional relation to cell signaling (Supplementary Data 2 and Supplementary Fig. 11a). Such peptides were tested for interaction with recombinant IKKα and IKKβ homodimers by pulldown. Only one peptide derived from the B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats (BANK1) is found to interact with IKKα, while no peptide interacts with IKKβ (Supplementary Fig. 11b). These results indicate that specific residue positions, e.g. the variable x of the motif or positions flanking the motif, are probably not compatible with certain amino acids. The sequence Logo derived from orthologous peptides from IκBα, IκBβ, p100, IRF7 and BANK1 is shown in Fig. 6h.

In BANK1 the YDDΦxΦ motif is conserved in mammalian orthologues and lies in the C-terminal region predicted to be disordered (Fig. 6f). Results from in vivo GPCA analyzes validate the interaction between the full-length IKKα and BANK1 proteins and further demonstrate the contribution of the motif since mutation of the Y1 and D3 positions (YD/SS) leads to a reduction of IKKα binding (Fig. 6g). Notably, BANK1 is expressed in B-cells and has been shown to function downstream of the BCR receptor and to associate to the NF-κB effectors TRAF6 and MyD8839,40.

Taken together these results show that the YDDΦxΦ motif is required for docking of IKKα and IKKβ homo- and heterodimers to multiple partner proteins within the NF-κB compartment.

Discussion

Kinase-substrate interactions involving SLiM recognition are mediated by docking grooves either within the kinase domain, or in separate globular domains (eg. SH2, SH3) or in associated regulatory proteins (e.g. cyclins)28. In this work, we show that IKKs have developed an alternative mechanism, which relies on a docking groove generated by dimerization of the SDD domain and which is negatively regulated by SLiM phosphorylation. Since dimerization is also required for kinase activation through the formation of higher order oligomers12, it appears that the SDD domain has evolved as a versatile structure, which ensures kinase activation and, at the same time, interaction with the substrate. This domain is also present in the IKK-related kinases TBK1 and IKKε, where it mediates dimerization and kinase activation via trans-autophosphorylation41. However, we did not detect any significant interaction between TBK1 or IKKε and the YDDΦxΦ motif peptides investigated in this work (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggesting that this motif is specific for dimers of IKKα and IKKβ. The IKK docking mechanism described here is reminiscent of the mode of action of the protein kinase A (PKA) holoenzyme, which uses dimerization of the DD domain of the PKA regulatory subunit (PKA-R) to generate a hydrophobic groove that targets helical motifs of AKAP proteins42,43.

Here we show that the affinity of the docking interaction correlates with phosphorylation of the IκBα substrate. This result is in agreement with early reports on the higher catalytic efficiencies of IKKβ homo- and heterodimers for the full-length IκBα protein comprising the YDDΦxΦ motif as compared to an N-terminal IκBα peptide encompassing the phosphorylation site44–46. Remarkably, these studies report that catalytic efficiency is the highest in the case of the IKKα/IKKβ heterodimer, a finding which could be explained by the higher binding affinity of IKKα for the docking motif as compared to IKKβ. Together, these results indicate that, in addition to mediating IKKβ activation and p100 phosphorylation, IKKα provides substrate recruitment functions in NF-κB signaling.

Upon stimulation of canonical NF-κB signaling, phosphorylation of IκB proteins occurs much more efficiently and rapidly as compared to other substrates such as p65 and p105, or of p100 after stimulation of the alternative pathway47. Such a fast response is primarily mediated by the scaffolding function of NEMO, which interacts with both IKK dimers via its N-terminus and with IκBs via its C-terminal zinc-finger domain, thereby channeling IKK activity specifically to IκBs15. From this, it appears that canonical IKK may use at least two interfaces to interact with IκBs, i.e. the YDDΦXΦ docking groove and the NEMO zinc finger (Fig. 7). Whether these interfaces co-exist in a single IKK/NEMO-IκB complex or whether different conformational states of the complex exist remains to be determined. Interestingly, Hoffmann and coworkers report that the NEMO-IκBα interaction is strengthened by IKKβ, an observation that would be in favor of co-existence of multiple interfaces15.

Fig. 7. Illustration of known protein-protein interactions mediating substrate recruitment to IKK complexes in NF-κB signaling.

Red arrows: interactions involving YDDΦxΦ docking to catalytic dimers; green arrows: interactions involving regulatory subunits.

Here, we find that the YDDΦxΦ motif also mediates p100 recruitment to the IKKα homodimer. In a previous study, Xiao et al. found that the NIK kinase associated to the ‘alternative’ IKK complex interacts with p10010. Hence, the overall picture which emerges from this and previous studies is that IKK complexes acting in NF-κB signaling use multiple binding interfaces, which are contributed by both catalytic dimers and regulatory subunits (Fig. 7).

To the best of our knowledge, the YDDΦxΦ consensus has not been previously reported for a SLiM. This consensus is conserved in NF-κB substrates (IκB and p100) from humans to fish. We find that phosphorylation at the strictly conserved Y1 position occurs in IκBα at steady state and has a detrimental effect on the binding to IKK dimers. These results are in line with previous work showing that phosphorylation at this position in IκBα increases upon activation of the c-Abl kinase by genotoxic stress30, and that this is associated with IκBα accumulation and inhibition of expression of NF-κB-dependent cell survival genes30,48. Together, these findings suggest that Tyr305 phosphorylation may represent a critical point of regulation by signaling pathways converging at the canonical IKK-IκBα complex.

The YDDΦxΦ motif is also conserved in IRF7, a known substrate of IKKα. However, although an IRF7 peptide binds weakly to IKKα in vitro, our analyzes failed to demonstrate a significant contribution of the motif towards the IKKα/IRF7 interaction in vivo. Based on YDDΦxΦ motif predictions, we identified BANK1 as a partner of IKKα. BANK1 is a scaffold protein expressed in B-cells, first described to function downstream of the BCR receptor to promote Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores39 and, more recently, reported to associate to TRAF6 and MyD88, two major NF-κB effectors in immune cells39,40. Elucidation of the function of the IKK/BANK1 interaction, i.e. substrate phosphorylation or anchoring of IKK to receptor-associated complexes, will be the subject of future studies.

IKKs have been reported to interact with a large number of substrates involved in several signaling pathways23. Yet, so far, only effectors of NF-κB signaling seem to interact with IKK dimers via the YDDΦxΦ motif. Thus, we expect that, just like in the case of MAPK kinases49, variations of the YDDΦxΦ consensus would still be recognized by the docking groove identified in this work. Given the lack of high-resolution reporting on side-chain conformation, it is difficult to predict such variations. In addition, IKK dimers may also encompass other docking grooves/pockets, which target completely unrelated SLiMs, similarly, to Protein Ser/Thr phosphatase-1 (PP1), which has developed distinct binding pockets dedicated to the different motifs of PP1-interacting proteins (PPI)50. Future proteome-wide analyzes combined with structural studies will provide a global view on the protein-protein interaction mechanisms used by IKKs to selectively recruit their substrates.

Deregulation of NF-κB signaling occurs in many pathologies, including infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Since enzymatic inhibitors of IKKβ have been associated with serious side effects51, peptide inhibitors derived from the NEMO subunit have been proposed as alternative therapeutic approaches52,53. Here, we show that a bivalent peptide derived from the YDDΦxΦ motif of IκBα efficiently inhibits canonical NF-κB signaling. It is tempting to speculate that, in addition to inhibiting interactions with the substrate, the bivalent peptide may also reduce kinase activation, by constraining the IKK dimer in a closed conformation and, thus, preventing IKK dimer oligomerization or secondary interface IKK-NEMO interactions54. Further structural analyzes will be required to evaluate this hypothesis.

To conclude, this work unveils the mechanism of substrate docking to IKK catalytic dimers. This mechanism, which is conserved in both the ‘canonical’ and ‘alternative’ branches of NF-κB signaling, probably conveys an upper level of recognition, with fine tuning of substrate specificity and/or kinetics being achieved through regulatory proteins of IKK complexes.

Methods

Details of reagents used in this study are provided in Supplementary Data 3.

DNA constructs

Expression in E. coli and insect cells

Full-length and deletion constructs of IκBα for E. coli expression were amplified by PCR and cloned into the NcoI and BamH1 sites of a modified pETM-41 and/or pETM10 vectors (kindly provided by G. Stier, University of Heidelberg), allowing for expression of N-terminal MBP and 6xHis tags, respectively. MBP-peptide fusions were obtained by ligation of complementary oligonucleotides coding for the peptide sequence into the NcoI and BamH1 sites of the modified pETM-41 vector.

The IKKβ(1-669) S177E/S181E (i.e. IKKβ(1-669) EE) and the IKKα(10-667) S176E/S180E (IKKα(10-667) EE) constructs for baculovirus expression were amplified by PCR and inserted by Gateway cloning into modified pBacPAK8 vectors, thereby allowing for expression of N-terminal 6xHis or Strep tags followed by a TEV protease cleavage site.

Expression in mammalian cells

Full-length IKKα, IKKβ, IκBα, p100, IRF7, BANK1, and constructs of these proteins used in the GPCA experiments were amplified by PCR and inserted into the pSPICA-N1 and pSPICA-N2 (both derived from the pCiNeo mammalian expression vector and kindly provided by Y. Jacob, Institut Pasteur, Paris) by Gateway cloning. These vectors enable expression of the Gluc1 (pSPICA-N1) and Gluc2 (pSPICA-N2) complementary fragments of the Gaussia princeps luciferase, which are linked to the N-terminal ends of the tested proteins by a flexible 20 amino acid linker55. Full-length wt and mutant IκBα constructs for virus preparation were cloned in the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the pBABE-puro retroviral vector56. To generate the mScarlet-E3-IκBα pep fusions, the DNA sequences coding for the E3 peptide31 fused to the IκBα pep variants were synthetized by Integrated DNA Technologies and cloned into the NheI and EcoRI sites of a pET vector allowing for the expression of a N-terminal mScarlet tag.

Mutagenesis

Side-directed mutagenesis of IKKα, IKKβ, IκBα, p100, IRF7, and BANK1 was performed using the QuickChange II kit (Agilent).

ORFs coding for IKKα, IKKβ, IκBα, p100, and IRF7 were obtained from Addgene. The ORF of BANK1 from DNASU. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Virus production

The recombinant viruses (bacmid) for expression in insect cells were generated by co-transfection of Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells (Oxford Expression Technologies) grown in Grace insect medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco)57. Briefly, 250 ng of linearized AcMNPV BAC10:KO1629, Δv-cath/chiA, mCherry bacmid57 and 750 ng of pBacPAK8 vectors containing the IKKα(10-667) EE or IKKβ(1-669) EE inserts were transfected into Sf9 cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in a T25 flask. Viruses contained in the medium after one-week incubation at 27 °C were subjected to a round of amplification yielding the P1 virus stock.

Viruses used for MEF transduction were obtained by transfecting Phoenix-eco cells (5 × 106) with 6 μg of pBABE-IκBα plasmid (empty vector was used as control) and 12 μl of TransIT (Mirus) as a transfection reagent. The medium was changed after 6 hours and replaced with 8 ml of fresh medium. The medium with virus was collected after 48 hours, filtered and used to infect MEFs.

Cell culture and transfection

Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells used to generate and amplify viruses were grown in Grace medium supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco), whereas Sf21 cells (Oxford Expression Technologies) for expression in insect cells were grown in the serum-free medium (Gibco). HEK293T were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% FCS at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and transfected using JetPEI® (Polyplus transfection). MEFs KO for IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε (kindly provided by Alexander Hoffmann, UCLA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and Pen-strep. Supernatants containing viruses (see above) were added to 2 × 106 MEF cells with polybrene (4 μg/ml) overnight. The medium was subsequently changed with some fresh growing medium. MRC5 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose, 10% FCS and 1 mM pyruvate.

Protein expression

E. coli

MBP-IκBα, MBP-peptide and 6xHis-IκBα fusion constructs for pulldown and in vitro activity assays were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Cultures were grown at 37 °C until an optical density of 0.2–0.6 at 600 nm. The cultures were then incubated overnight at 18 °C. Cells were harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Insect cells

For production of 6xHis-IKKα(10-667) EE and 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE homodimer samples, Sf21 cells grown in suspension were infected with the corresponding virus, harvested after 3 days incubation at 27 °C, washed in PBS containing 10% v/v glycerol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Typically, cells are grown in 2 L flasks containing 500 ml of medium and are infected at a density of 1.106 cells/ml using 20 ml of P1 virus stock (assuming a titer of 5 × 107 pfu/ml, it corresponds to a multiplicity of infection of 2). For production of the IKKα/β heterodimer, Sf21 cells were co-infected with Strep-IKKα(10-667) EE and 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE viruses. Cells were typically infected at a density of 2.106 cells/ml with a nominal multiplicity of infection of 0.5 for each virus (10 ml of each P1 virus stock for a 500 ml culture).

Protein purification

IKKα and IKKβ homodimers

Purification of 6xHis- IKKα(10-667) EE and 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE constructs was carried out as previously reported12,13, with modifications according to the specific use of the samples. Briefly, SF21 cells expressing IKKα or IKKβ proteins were resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml DNaseI, 0.2 μg/ml RNase, Roche completeTM protease inhibitor cocktail) and lysed by mild sonication. Lysates were centrifuged at 14500 g for 45 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatants were applied by gravity flow to Ni2+-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated in wash buffer 1 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT). The resin was extensively washed by four consecutive steps using the following buffers: (i) wash buffer 1, (ii) wash buffer 2 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT), (iii) wash buffer 3 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT) and (iv) wash buffer 1. IKKα or IKKβ proteins were eluted using elution buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 250 mM imidazole, 2 mM DTT).

In the case of IKKα and IKKβ proteins to be used for pulldown and kinase activity assays, samples were concentrated and incubated in the presence of 1 mM ATP plus additives (20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) for 1 hour on ice. Samples were then purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex® 200 10/30 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated in gel filtration buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 2 mM DTT). In the case of cross-linking mass spectrometry experiments, concentrated IKKβ samples were incubated with a 20-fold excess of ML120B inhibitor (Sigma) plus additives for 1 hour on ice and then loaded on the Superdex® 200 10/30 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated in gel filtration buffer 2 (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM TCEP).

For the ITC and crystallization experiments, after the Ni2+-NTA step the 6xHis tag was removed from the IKKα and/or IKKβ constructs by overnight digestion with TEV protease at the same time as dialysis against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 5% glycerol. Then, the sample was applied to Ni2+-NTA resin pre-equilibrated in dialysis buffer and the flow-through containing the IKKα or IKKβ protein collected. Next, the samples were concentrated, incubated with ML120B inhibitor plus additives for 1 hour on ice and was applied to a Superdex® 200 16/60 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated in gel filtration buffer 2 (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP). Finally, fractions containing the IKKα or IKKβ proteins were pooled together and the NaCl concentration adjusted to 150 mM. Purified IKKα and IKKβ samples were stored at 4 °C for up to 5 days.

IKKα/β heterodimer

SF21 cells expressing the Strep-IKKα(10-667) EE and 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE proteins were resuspended in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml DNaseI, 0.2 μg/ml RNase, Roche cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor cocktail) and lysed by mild sonication. Lysates were centrifuged at 14 500 g for 45 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatants were applied by gravity flow to Strep-Tactin XT 4 F resin (IBA-lifesciences) pre-equilibrated in wash buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM DTT). After extensive washing the proteins were eluted with elution buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT, and 50 mM biotin). The eluate was then applied to Ni2+-NTA resin, which was washed and eluted as described above for the IKK homodimers. IKKα/β heterodimer samples were then concentrated and incubated in the presence of 1 mM ATP plus additives (see above) for 1 hour on ice. Finally, samples were purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex® 200 10/30 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated in gel filtration buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 2 mM DTT).

6xHis-IκBα

BL21 cells expressing 6xHis-IκBα proteins for kinase activity studies were resuspended in 50 ml of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 0.2 % NP40, 2 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml DNase I, 0.2 μg/ml RNase, Roche cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor cocktail) and lysed by sonication. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 96 000 g for 45 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was applied by gravity flow to Ni2+-NTA agarose resin pre-equilibrated in wash buffer 1 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2 mM DTT). The resin was washed with: (i) wash buffer 1, (ii) wash buffer 2 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 2 mM DTT), (iii) wash buffer 3 (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 M NaCl, 2 mM DTT) and (iv) wash buffer 1. Subsequently, 6xHis-IκBα proteins were eluted with elution buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 2 mM DTT). Finally, imidazole was eliminated using a PD-10 desalting column (Cytiva) equilibrated in assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT). Samples were concentrated, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

MBP-fusions

For pulldowns, MBP-IκBα and MBP-peptide constructs were coupled to the amylose resin. Pellets of 10–25 ml of bacterial culture were resuspended in 2.5 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2 % NP40, 2 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml DNase I, 0.2 μg/ml RNase, Roche cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor cocktail) and lysed by sonication. Lysates were centrifugated using a benchtop centrifuge at maximal speed and at 4 °C. Clarified lysates were incubated with 100 μl (dry bead volume) of previously equilibrated amylose resin (New England Biolabs) for 45 minutes at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. Resins were washed first with wash buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT) and then with wash assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT). Resins coupled to MBP-fusion constructs were stored at 4 °C up to one week.

Chemical peptide synthesis

The synthesized peptides have the sequences reported below.

IκBα pep (residues 297-317 of IκBα): EFTEDELPYDDCVFGGQRLTL

C308L IκBα pep: EFTEDELPYDDLVFGGQRLTL

pY-IκBα pep: EFTEDELPpYDDLVFGGQRLTL

YD/SS IκBα pep: EFTEDELPSDSCVFGGQKLTL

C308L/R314K IκBα pep: EFTEDELPYDDLVFGGQKLTL

C308L/R314K IκBα-biot pep EFTEDELPYDDLVFGGQKLTLGGG-(PEG)3-K-biotin

p100 pep (residues 8-29 of p100): GLDGIIEYDDFKLNSSIVEPKE

IRF7 pep (residues 495-516 of IRF7 isoform D): LSSANSLYDDIECFLMELEQPA

IκBα pep, pY-IκBα pep and p100 pep peptides were prepared by Fmoc/tBu-solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS)58 with the help of an ABI 433 A automatic peptide synthesizer in the form of Cα-carboxylates using preloaded resins (Novabiochem). C308L IκBα pep was assembled by Fmoc/tBu-SPPS using a CEM Liberty Blue microwave-assisted synthesizer in the form of Cα-amide (Rink-amide resin from Iris Biotech). YD/SS IκBα pep, C308L/R314K IκBα pep, C308L/R314K IκBα-biot pep and IRF7 pep were prepared by manual ‘in situ neutralization’ manual Boc/Bzl-SPPS59 using MBHA-resin (Iris Biotech) as Cα-amides. IRF7 pep was acetylated at N-terminus. Standard protocols and commercial amino acid building blocks were used in each case. Purification was carried out by reverse-phase HPLC (C18 column). Purity was controlled by analytical HPLC ( > 95%) and masses were confirmed by LC-MS using electrospray ionization (ESI).

MBP-pulldown

Experiments were performed in PD buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT). For each experiment, 10 μl of amylose resin (dry bead volume) coupled to MBP-fusion constructs were incubated with 500 μl of purified 6xHis-IKKα(10-667) EE or 6xHis-IKKβ (1-669) EE adjusted to a concentration of 0.4 μM for 2 hours at 4 °C. In the case of competition PD experiments, IKK samples were pre-incubated with an excess of synthetic IκBα pep peptides for one hour on ice. After two quick washing steps with PD buffer, complexes were eluted by incubation with 20 μl of the same buffer supplemented with 20 mM maltose for 15 minutes at 4 °C. After mild centrifugation, supernatants were recovered and migrated onto two separate 10% SDS-PAGE gels. One gel was used for Western blot analysis to detect His-IKKα or His-IKKβ using and anti-6xHis antibody (Sigma), the other for Coomassie staining to detect MBP-fusion proteins. Quantification of band intensity was done using the Image J software.

GPCA

HEK293T cells were transfected using the reverse transfection method. Transfection mixes containing 100 ng of pSPICA-N2 and 100 ng of pSPICA-N1 plasmids expressing test proteins plus PEI-MAX (Polysciences) were dispensed in white 96-well plates. HEK293T cells were then seeded on the DNA mixes at a concentration of 4.2 × 104 cells per well. 48 hours after transfection, cells were washed with 50 µl of PBS and lysed with 40 µl of Renilla lysis buffer (Promega) for 30 minutes with agitation. Gaussia princeps luciferase enzymatic activity was measured using a Berthold Centro LB960 luminometer by injecting 50 µl per well of luciferase substrate reagent (Promega) and counting luminescence for 10 seconds. Results are expressed as a fold change normalized over the sum of controls, specified herein as normalized luminescence ratio (NLR)55. For a given protein pair A/B, NLR = (Gluc1-A + Gluc2-B) / [(Gluc1-A + Gluc2) + (Gluc1 + Gluc2-B)]. In each GPCA dataset interactions were measured in three independent transfection experiments.

The expression levels of Gluc1- and Gluc2-fused proteins were checked by Western blotting. At 24 h post-transfection cells were collected, lysed by incubation on ice with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor) and centrifuged. Aliquots of cleared supernatants were loaded onto an 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were detected using a polyclonal antibody against the Gaussia P. luciferase (New England Biolabs or Invitrogen).

ITC

All experiments were performed in ITC buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP) unless otherwise stated. Purified IKKα(10-667) EE and IKKβ(1-669) EE protein samples were dialyzed overnight against ITC buffer at 4 °C. Just before the ITC experiments, IKKα or IKKβ samples were concentrated, incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 11 000 g to remove eventual precipitate. The final concentrations of IKKα and IKKβ in the sample cell varied between 22 and 50 μM, depending on the measurement. HPLC purified synthetic peptides were further desalted using a Nap5 (Cytiva, #17-0853-01) column equilibrated in milliQ water, lyophilized and then resuspended in ITC buffer. Peptide concentration in the syringe varied between 220 and 975 μM, depending on the measurement.

All ITC measurements were performed using a PEAQ-ITC MALVERN instrument. The titration parameters were set as following: temperature 25 °C, reference power 10 μcal/s, feedback=high, stirring speed 750 RPM, initial delay 60 s, first injection 0.4 μL in 0.8 s and the remaining 19 injections were 2 μL in 4 s with 120 s of spacing. The data were fitted to a 1:1 binding model. Initial data processing was carried out in MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis software. For thermodynamic analysis, all data were processed using NITPIC software60 and global fitting of two datasets was carried out using SEDPHAT61. For some interaction pairs sample aggregation during the titration caused disturbed baselines. For this, unbiased baseline subtraction of NITPIC was instrumental in obtaining the data suitable for the analysis. The error analysis was done using error surfaces prescribed by F-statistics as implemented in SEDPHAT. The confidence intervals at 68.3% probability corresponding to one SD assuming a Gaussian error distribution were derived for KD and ∆H best-fit values and are reported in Table 1. The binding in IKKα/pY-IκBα pep and IKKα/IRF7 pep interactions was too weak to allow for accurate thermodynamic analysis.

In vitro kinase assays

Using recombinant IKKβ

Reactions were performed in the kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 400 μM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM DTT, and 400 µM ATP) using 0.5 nM of purified 6xHis-IKKβ(1-669) EE protein and 1 µM of purified full-length 6xHis-IκBα wt or mutant constructs.

Using endogenous IKK complex

IKK was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells. 3 petri dishes (100 × 15 mm) of cells at 70% confluence were induced with 10 nM recombinant TNFα (R&D Systems) for 10 minutes, and then washed twice by cold PBS. The whole-cell extracts were prepared by addition of 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM mM HEPES pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, Roche cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) and homogenized by passing through a 21-gauge needle for 5-10 times. After 30 minutes of incubation on ice, the extracts were centrifuged at 11,000 g and at 4 °C. The cleared supernatants were incubated with 15 µl of anti-NEMO antibody (Santa Cruz biotech) overnight at 4 °C and, then, immunoprecipitated with 150 µl of protein G Sepharose® beads (Cytiva) for 2 hours at 4 °C. The beads were washed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM Na orthovanadate, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT) and then resuspended with wash buffer to a final volume of 150 µl. Kinase reactions were performed in kinase buffer (defined above) using 50 µl of immunoprecipitant and 1 µM of purified full-length 6xHis-IκBα wt or mutant constructs. For evaluation of peptide inhibitory activity, the reactions were supplemented with 500 µM of synthetic IκBα pep peptide variants.

All reaction mixtures were set-up in a total volume of 150 µl and incubated at 30 °C, with 30 µl aliquots sampled at 0, 5, 10 and 30 minutes time points. Reactions were stopped by addition of Laemmli sample buffer plus heating for 5 minutes at 95 °C and analyzed on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel followed by Western blotting using anti-phospho-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-IKKβ (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-6xHis (Sigma) antibodies. The relative amounts of phosphorylated IκBα were quantified using ImageJ.

In cellulo inhibition of NF-κB signaling

The mRNAs coding for the mScarlet-E3-IκBα pep fusions were transcribed from the T7 promoter using HiScribeTM T7 ARCA mRNA Kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer recommendations. 0.5 µg mRNAs were electroporated in 1.105 MRC-5 cells using the NeonTM transfection system (Invitrogen)62. 24 hours after electroporation, cells were treated or not with TNFα (R&D system) at 20 ng/ml for 30 minutes. Hence, cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes in PBS buffer, 10% FCS. Cells were incubated with anti-p65 antibody (1/2000 dilution) (Santa-Cruz biotechnology,) followed by an anti-mouse mAb-Alexa-Fluor 488 conjugated (Invitrogen). Coverslips were then mounted with Fluoromount G containing 4’,6’–diamidino-2-phenyleindole (SouthernBiotech). Treated cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Leica DM5500B and LAS AF software). Image processing was performed using ImageJ 2.3.0. Data analysis was performed using Prism 9 software. Statistical analysis was performed by ordinary one-way ANOVA test.

Antibodies

Immunoblotting

Anti-6xHis (Sigma, H1029), anti-HA (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-7392), anti-IKKβ (Cell Signaling Technology, 2684), anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-371), anti-phospho-Ser32,Ser36-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology, 9246), anti-Gluc (New England Biolabs, E8023, Invitrogen, PA1-181), anti-phospho-tyrosine (Millipore, 05-321), anti-HSP90 (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-13119).

Immunoprecipitation

Anti-NEMO (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-166398), anti-HA beads (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-7392AC), mouse IgG (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-2025).

Immunofluorescence

Anti-p65 (Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-8008), Anti-mouse secondary antibody-AlexaFluor 488 (Invitrogen, A-11001).

x-ray crystallography

Crystallization

The purified IKKβ(1-669) EE construct in 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP was concentrated to 15 mg/ml, mixed with a 1.5 molar excess of synthetic wt IκBα pep and incubated on ice for 1 hour. Crystallization experiments were performed by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 277 K using a Mosquito Crystal nanolitre dispensing robot (SPT Labtech) and several commercially available screens, i.e. the Berkeley screen (prepared in-house63), the ProComplex suite, the Classics suite and the PEGs suite (Qiagen), the JCSG+ suite and the Wizard Classic 1 & 2 suite (Molecular Dimensions). 0.1 µl of the sample solution was mixed with 0.1 µl of the reservoir solution and equilibrated against 50 µl of reservoir solution in 96-well MRC2 sitting drop vapor diffusion crystallization plates (Molecular Dimensions). The plates were stored at 277 K and automatically imaged using a RockImager 1000 (Formulatrix).

Small initial crystals ( ~ 50 ×15 x 15 µm) appeared after 2 days in condition 4 of the Berkeley screen (1.8 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Bis-Tris HCl pH 6.5, 10% 2-propanol) but appeared multiple. After manual reproduction of the condition, large single crystals ( ~ 500 ×80 x 40 µm) grew after 8 days. The crystals were transferred to 2 M Li2SO4, 0.1 M Bis-Tris HCl pH 6.5 before flash cooling in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and processing, and structure determination

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K on an EIGER X 9 M detector (Dectris) at the Proxima 2 A beamline of Synchrotron SOLEIL (Paris). 360° of data were collected using 0.1° rotation and 0.025 s exposure per image at 100% beam intensity at an energy of 12.65 keV (wavelength = 0.98 Å). The data were processed and scaled using XDS64 before anisotropic truncation and correction was performed using the STARANISO server65. The crystal diffracted anisotropically to 4.2 Å (6.8 Å in the worst direction) and belonged to the C-centered monoclinic space group C2 with unit cell dimensions a = 226.3 Å, b = 136.8 Å, c = 204.4 Å, β = 91.45°.

The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER66 in the PHENIX suite67 using a monomer extracted from the structure of the asymmetric dimer of human IκB kinase β14 (PDB ID 4KIK) as a search model. The asymmetric unit contains five copies of the protein (two dimers, and one monomer that forms a dimer with itself over a crystallographic 2-fold rotation axis), with a corresponding Matthews’ coefficient of 4.1 Å3 Da-1 and a solvent content of 69.9 %. Refinement of the structures was performed using PHENIX68 and BUSTER69 followed by with iterative model building in COOT70. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Cross-linking mass spectrometry (CLMS)

Sample preparation