Abstract

Direct ethanol fuel cells (DEFCs) have been widely considered as a feasible power conversion technology for portable and mobile applications. The economic feasibility of DEFCs relies on two conditions: a notable reduction in the expensive nature of precious metal electrocatalysts and a simultaneous remarkable improvement in the anode's long-term performance. Despite the considerable progress achieved in recent decades in Pt nanoengineering to reduce its loading in catalyst ink with enhanced mass activity, attempts to tackle these problems have yet to be successful. During the ethanol oxidation reaction (EOR) at the anode surface, Pt electrocatalysts lose their electrocatalytic activity rapidly due to poisoning by surface-adsorbed reaction intermediates like CO. This phenomenon leads to a significant loss in electrocatalytic performance within a relatively short time. This review provides an overview of the mechanistic approaches during the EOR of noble metal-based anode materials. Additionally, we emphasized the significance of many essential factors that govern the EOR activity of the electrode surface. Furthermore, we provided a comprehensive examination of the challenges and potential advancements in electrocatalytic EOR.

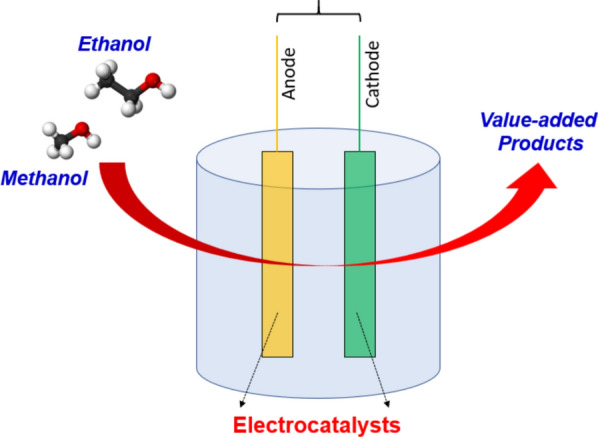

Graphic abstract

Keywords: Electrocatalysts, Pt-based catalysts, Ethanol oxidation reaction, Direct ethanol fuel cells

Introduction

Logical motivation

Every day, more and more people are finding it harder and more difficult to satisfy their insatiable need for energy. Non-renewable and eco-friendly fossil fuels are on trend to meet the world's enormous energy demands. Nevertheless, a lingering problem for society today is the creation of a self-motivated energy supply to help globally reduce fossil fuel’s depletion as well as environmental [1] issues [2, 3]. Finding abundant non-traditional options to bridge the difference of energy demand and supply is the pressing responsibility of our current generation. In this context, H2-O2 fuel cells (FCs) are emerging, eco-friendly, and silent power systems offering the direct conversion of latent chemical energy into electricity [4, 5]. When it comes to portable electronics and light-duty cars, to avoid the risk of flammable H2 (as fuel) and its expensive storage, the direct ethanol fuel cell (DEFC) is a great choice. However, the use of these devices at a practical level is still limited due to the requirement of inexpensive and high-performing electrocatalysts to catalyze the anode process, the ethanol oxidation reaction (EOR [6]) [4].

Catalysts for direct ethanol fuel cells

A significant amount of research has been conducted on the improvement of electrocatalytic kinetics in EOR using platinum (Pt) or Pt-based nanomaterials, as well as Pt-based hybrid materials combined with other transition metal oxides such as Fe2O3, TiO2, SnO2, MnO, Cu2O, and ZnO [4]. Recent studies have focused on examining the electrooxidation of Cn alcohols (n > 1) using noble metals including Pt, Au, and Pd, as well as their alloys. The selection of these metals is based on their inherent stability and robust catalytic activity [7, 8]. Withing this framework, the extensive research on the electrooxidation of C2H5OH began half a century ago, including several ground-breaking investigations [9]. In the 1960s, Petry et al. [10] reported significant advancements in surface electrochemistry methods, which have since undergone continual improvement. The significant findings obtained encompass several aspects: (i) a phenomenological elucidation of the anodic polarization curve, including the estimation of Tafel parameters for C2H5OH oxidation in alkaline electrolyte on Ni and Pt/C; (ii) the identification of the co-catalytic effect of Ru in relation to Pt for EOR; (iii) an exploration of the potential-dependent adsorption of C2H5OH and CH3COOH on Pt, along with an examination of the pathway mechanism; and (iv) the development of a mathematical model to elaborate the behavior of a flooded porous electrode [11–13]. Initially, the feasibility of using CH3OH, C2H5OH, and HCOOH as anodic fuels combined with oxygen or air gas diffusion cathodes was explored for energy production. Liquid electrolytes such as concentrated H2SO4, H3PO4, or KOH first facilitate ionic conductivity on the anode side. During the 1970s and 1980s, the primary focus of research was on investigating the electrooxidation reaction mechanism and identifying the surface adsorbed species that served as intermediates or catalytic poisons. However, advancements were obtained during this period with the advent of novel procedures for the fabrication of pristine single-crystal electrodes. Thus, Weaver et al. [14] performed a study to investigate the relative structural sensitivity of C2H5OH electrooxidation on single crystal Pt surfaces using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) in combination with quasi-steady state voltammetry, exploring the fundamental findings of EOR intermediate adsorption on Pt surfaces. In their study, Stede et al. [15] fabricated an electrode composed of Pt alloyed with Mo, V, Cu, W, Mn, or Ce and supported on porous graphite as an anode. The electrode was subjected to direct C2H5OH oxidation in a solution containing 30 vol% C2H5OH and 30 wt% H2SO4 at 30 V, demonstrating excellent EOR performance of this alloyed electrode material. Although significant advancements have been achieved in the study of DEFCs, there are several unresolved inquiries pertaining to their efficiency and the underlying comprehension of their structural and mechanistic characteristics, as elaborated upon below [16].

DEFCs' shortcomings and potential remedies

While there is a great deal of commercial potential for DEFCs, there are a number of obstacles to maximising their performance, including extremely sluggish EOR kinetics at the anode, partial oxidation of ethanol (C2H5OH), crossover of C2H5OH [17], expensive noble metal catalysts, blocking of the catalyst’s active site due to sensitive EOR intermediates, less durability of the electrocatalyst, and water, as well as heat management [18]. Usually, the catalyst’s surface provides the active sites for the EOR process, reducing the activation energy for the C2H5OH oxidation to proceed at a higher rate. Energy expended during the breaking and formation of the reactant and product bonds is greatly affected by a lower activation energy, while the time required for the reaction to complete is reduced by a greater rate. A number of processes lead to partially oxidised by-products, such as acetaldehyde (CH3CHO) and acetic acid (CH3COOH), when C2H5OH is oxidised [19–22]. When comparing DEFCs and direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs), the amount of C2H5OH crossing is lower in the former. Regardless, the mixed potential that develops at the cathode as a result of C2H5OH crossover or permeation has an impact on the DEFC's efficiency. Temperature, C2H5OH content, and flow rate are the three variables that have the most impact on the fuel crossover [23, 24]. For instance, Heysiattalab et al. [25] said that increasing the DEFC's working temperature makes the anode (EOR) and cathode (oxygen reduction reaction (ORR)) processes much faster. High temperatures can reduce the activation loss, improve the OH− ion conductivity, and thereby lower the ohmic loss. Additionally, increasing the flow rate of C2H5OH and O2 transportation can minimise concentration loss. Moreover, Li et al. [26, 27] proposed two reasons for the loss of DEFCs performance when exposed to excessive amounts of C2H5OH: (i) C2H5OH covers the electroactive sites, which reduces the adsorption of OH− ions, and (ii) the reduced level of OH− ionisation caused by the excess C2H5OH, increasing the cell resistance because ions can't move as freely. In the high-current density zone, Alzate et al. [28] discovered significant increment in mass transfer of C2H5OH and OH− from flow field to electrocatalyst can be achieved via increment of fuel flow rate, leading to better DEFC performance. Diluting the C2H5OH fluid is a good way to prevent the C2H5OH molecules from crossing over into the anode catalyst layer [29]. However, this can cause some energy loss in the DEFCs. Despite this approach, the development of efficient and C2H5OH-tolerant electrocatalysts for DEFC’s processes can also be a good approach. In this context, the unique electronic as well as remarkable catalytic properties of Pt-based materials at the atomic level make them promising electrocatalysts for DEFCs. However, when EOR takes place on Pt’s surface, the reactive EOR intermediates (CO*, CH3CHO*, etc.) cause the poisoning of Pt-active sites and therefore greatly reduce the overall DEFC’s performance. Moreover, Pt is a very expensive metal, which limits its further use as an electrocatalyst for EOR or calls for further research on reducing its amount in the catalyst’s ink to reduce the overall cost of the electrocatalyst to be used in DEFCs [30–33].

On the other hand, DEFCs produce CH3COOH, and CH3CHO as by-products of electrocatalytic EOR. The selectivity of acetaldehyde improves as the operating temperature rises, while the selectivity of acetic acid diminishes during DEFC operation. The presence of acetaldehyde and acetic acid can decrease the efficiency of DEFCs. Moreover, an elevated acetaldehyde concentration leads to a decrease in ethanol concentration, which subsequently causes a fall in voltage. Thus, through effective heat management, it is possible to regulate the byproducts generated during the EOR process. Therefore, heat management is an important parameter for the commercialization of this technology [34]. An increase in DEFC’s operating temperature causes an improvement in the selectivity towards CH3CHO formation, while a drop-in selectivity towards the formation of CH3COOH occurs under constant current operation. Current concentrations of CH3CHO and CH3COOH may reduce the overall efficiency of DEFCs. Voltage drops as the C2H5OH concentration drops due to the high CH3CHO concentration. Thus, heat management in DEFCs allows for control of the EOR process's by-products [35, 36]. Moreover, DEFC's performance will be negatively impacted by the generated cell resistance if H2O is not properly managed. The anode compartment can lose H2O, the cathode compartment can flood, and the device can short circuit if there is an incredible amount of H2O across the membrane. Research and development of an adequate electrode catalyst are crucial for the DEFCs electrode reactions to overcome these issues [37, 38], considering (i) the creation of inexpensive and effective electrocatalysts with good efficiency, stability, concentration control, and ethanol flow rate capabilities; (ii) the development of new membranes with less C2H5OH crossover properties; (iii) the heat and H2O management; and (d) designing the catalyst’s crystal structure for the oxidation of all C2H5OH molecules before their arrival at the anode-membrane interface.

This review focuses on the recent advancements in DEFCs regarding catalyst engineering and DEFC performance. The paper goes into great detail about the study and workings of Pt-based electrocatalysts for the EOR. It focuses on unresolved problems in material design, electrode processes, and performance factors that affect DEFCs. Academics, researchers, and scientists involved in (i) electrocatalytic alcohol oxidation reactions, (ii) electrocatalysts based on noble metals for these reactions, (iii) the relationship between the structure of a catalyst and its EOR catalytic activity, and (iv) maximizing the alcohol fuel cells' usefulness in the real world will find this review appealing.

Temperature-dependence of DEFCs and electrode process

Working temperatures of DEFCs

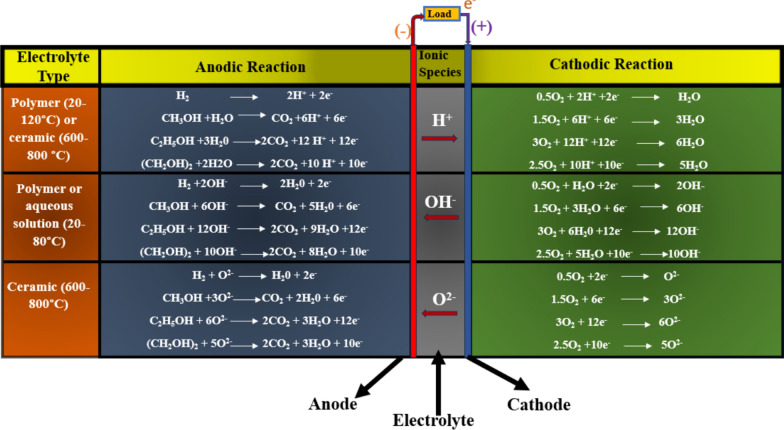

At the moment, there are various types of alcohol FCs that are still in the early stages of development. These FCs contain solid or liquid electrolytes that conduct oxygen ions, direct or indirect alcohol fueling systems, and can be operated at temperatures as low as 100 °C and as high as 400–500 °C [39, 40]. Usually, transforming alcohol into H2 gas and CO is the first step in indirect alcohol FCs. High-temperature FCs based on solid oxide or molten carbonate use H2 gas as fuel [41]. On the other hand, low-temperature FCs based on proton exchange membranes use C2H5OH as fuel, ideally, but they also use CH3OH and (CH2OH)2. The specific number of electrons needed to completely oxidize H2, CH3OH, C2H5OH, and (CH2OH)2 are 2, 6, 12, and 10, respectively [42]. The temperature ranges for ceramic-centered electrolyte FCs are 600–800 °C, while electrolytes based on polymer membranes can operate from 20 to 120 °C [43]. Further, in alcohol-based FCs, H2O is formed at the anode in electrolytes that conduct oxygen and hydroxyl ions and at the cathode in electrolytes that conduct protons, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A graphical representation of various temperature dependent DEFCs along with their electrochemical reactions.

Taken from [44], Copyright 2015, Elsevier publishing group

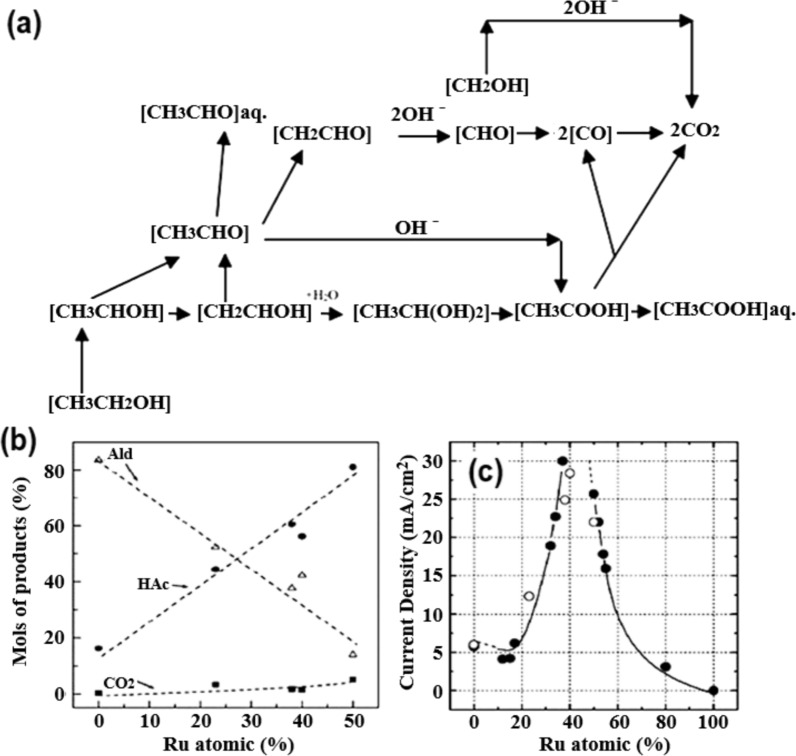

Electro-oxidation of ethanol

Usually, the more carbon atoms there are in an alcohol molecule, the more steps are needed to electro-oxidize that alcohol [22, 23], and certain catalysts are needed for such alcohol oxidation [45]. Figure 2a shows the typical process of ethanol electro-oxidation, which results in the production of CH3CHO, CH3COOH, and CO. In order to examine the impact of C2H5OH concentration on the distribution of byproducts, Iwasita et al. [46] developed a catalyst based on Pt. The results showed that there was no CH3CHO production at C2H5OH concentrations lower than 0.5 M. The CH3CHO yield was greater than the CH3COOH yield when the concentration of C2H5OH was greater than 0.15 M. As shown in Fig. 2b, the increase in CH3COOH concentration that takes place in the presence of Ru (Pt-Ru) has an impact on the distribution of the products. The highest current density for oxidizing C2H5OH (at 0.5 V vs. RHE) made CH3COOH as the main product, as seen in Fig. 2c, which shows the 40% Ru catalyst.

Fig. 2.

a Multistep reaction model for ethanol electrooxidation. Adapted with permission [47]. Copyright @2008, Springer. Effect of Ru content on C2H5OH electrooxidation: b the product distribution after 3 min of polarization at 0.5 V versus RHE. c Oxidation current density after 30 min of polarization at 0.5 V versus RHE. 1 M C2H5OH–0.5 M H2SO4; 298 K.

Adapted with permission [46]. Copyright @2005, Elsevier

Advances in electrocatalyst’s engineering for ethanol oxidation reaction

As discussed in the above sections, Pt-based materials possess promising features for electrocatalytic EOR. In last decades, the approaches, including creation of nano-engineering of Pt, blending of Pt with other transition metals, and incorporation of Pt-based catalysts with conductive support, have been experimented to achieve the ideal performance of Pt-based catalysts.

Creation of nano-engineering of Pt

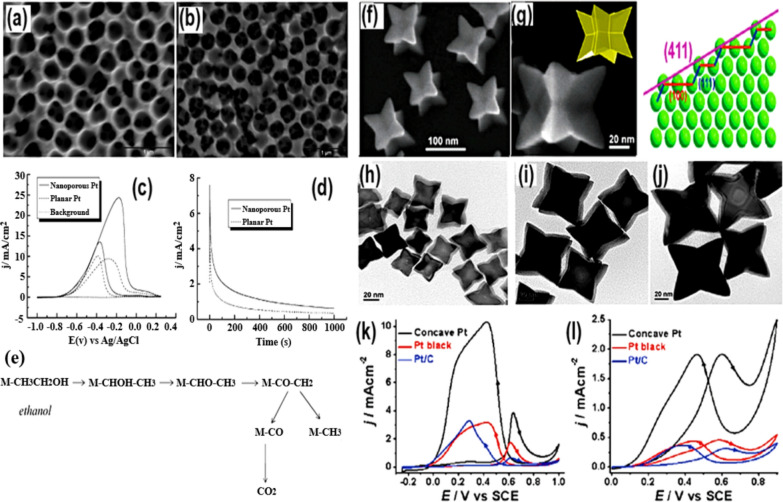

Usually, Pt presents itself in three distinct morphologies: Pt (100), Pt (110), and Pt (111). Among these, Pt (111) appeared to be the best in generation of current density. To evaluate the effect of these different forms of Pt catalyst on electrocatalytic oxidation of alcohol, Dimos and colleagues [48] reported to have prepared two phases of Pt, nano-porous (having a high surface area) and planar (having a low surface area), and tested their electrocatalytic EOR (Fig. 3a, b). These results indicated that nanoporous Pt exhibited better electrocatalytic performance in the form of lower onset potential and good stability under standard conditions as compared to planer Pt catalysts [49]. Nano-porous Pt has a larger anodic peak ratio, which allows it to oxidize CO more effectively (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

SEM pictures of nanoporous a Pt and b Pd deposited onto silica substrate. c CVs, and d Chronamperometric curves, recorded in 1.0 M EtOH/1.0 M KOH electrolyte for both the nanoporous and planar Pt. e The proposed EOR mechanism on Pt-site. Taken with permission from [48]. Copyrights @2010, American Chemical Society. f, g The SEM picture along with crystal structure. h–j The TEM picture, and the CV plots for electro-oxidation of k HCOOH and l C2H5OH, for of concave Pt nanocrystals.

Taken with permission from [50]. Copyrights @2010, American Chemical Society

Furthermore, in a basic medium, nanoporous Pt can achieve a larger current density than in an acidic one. However, the reaction intermediates can cause the blocking of Pt active sites, reducing the EOR kinetics and reducing the catalyst’s efficiency (Fig. 3e). Moreover, the extremely high cost and low stability of Pt-based materials drastically restrict their wide range of potential applications. In this context, lots of work have been done to replace the Pt-based catalysts or to bring down the Pt loading in the catalyst layer, blending Pt with other non-noble, effective, and durable materials [4, 51, 52]. The production of such nanoscale electrocatalysts with well-defined geometries, compositions, and configurations considerably improved efficiency in the EOR process. Huang et al. [50] recently documented the formation of concave Pt nanocrystals with high-index facets, primarily made up of atoms with low coordination numbers on the surface (Fig. 3f–j). The electrocatalytic performance of these nanocrystals was superior compared to their low-index equivalents. A solvothermal method with PVP and methylamine surfactant was used to make a nanocrystal with high-index [50] exposed facets and a concave structure. Due to the high-index facets, the concave Pt nanocrystals showed amazing electrocatalytic EOR performance, demonstrating 4.2 and 6.0 times greater than commercial Pt black and Pt/C, respectively, at 0.60 V (vs SCE) (Fig. 3k–l) [50].

Further, Chen et al. [53] proposed a new approach to design an effective electrocatalysts for the electrocatalytic EOR process. They created a mesoporous carbon (MPC) as a nanoscale reactor and deposited a precursor onto it via a melt-diffusion process. Afterwards, Pt NPs were created by reducing the material under H2 gas. These NPs were then evenly distributed throughout the channel's tiny mesopores and the pore wall, forming Pt/MPC. During EOR process, the resultant Pt/MPC catalyst demonstrated exceptional catalytic activity and long-term durability. Particularly noteworthy were the increased selectivity for the conversion of C2H5OH to CO2 and the increased reactivity in C–C bond breakage demonstrated by the catalysts in their natural state. The improved electrocatalytic performance of the Pt/MPC catalyst was explained by three main factors: (a) the large pore volume and specific surface area of MPC, along with the interpenetrated small-sized mesopores in the pore walls, which allow reactive species to be efficiently transported and Pt NPs to be evenly dispersed. (b) The limited expansion of Pt nanoparticles, caused by the creation of Pt NPs with limited coordination sites in the small mesopores and meso-channels, limits their expansion. (c) The use of the unrelenting carbon elements within the mesoporous carbon channels, along with the melt-diffusion method for precursor loading, enhances the electrical conductivity and efficiently utilises Pt nanoparticles. Furthermore, the chronoamperometric results showed that the prepared Pt/MPC catalyst had remarkable stability, with a current density of 675 mA/cm2 at 0.64 V versus SCE. In addition, the CV results demonstrated the ability to sustain the maximum current density for 1800s and 4000 cycles [53].

Blending of Pt with other transition metals

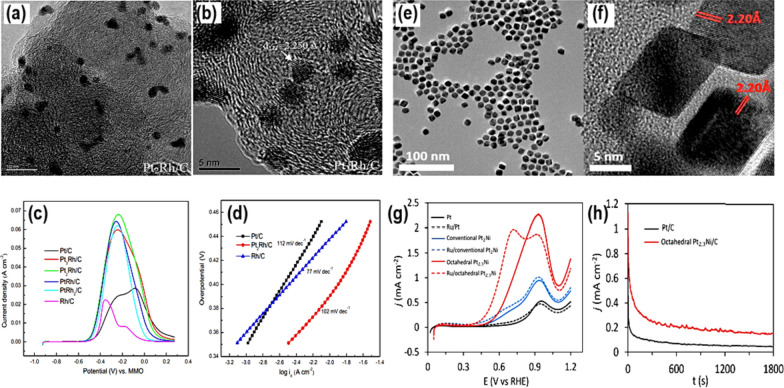

Besides, adding a second metal to Pt catalysts, forming an alloy, can alter the Pt’s electronic as well as coordination structure, particle size, shape, surface structure, chemical selectivity, and catalytic activity. Following increment of active sites along with surface area via Pt incorporation can bring significant improvement in catalytic performance. In order to test how well bimetallic electrocatalysts work towards the EOR process, Shen et al. [54] reported having prepared Pt–Rh/C-based electrocatalysts using the microwave-assisted polyol approach (Fig. 4a, b). The electrochemical behavior of these catalysts was recorded using cyclic voltammetry in alkaline circumstances, and compared with Pt/C. These catalysts improved the onset potential for CO formation during EOR, along with improved peak current density. Among the fabricated catalysts, Pt2Rh/C showed, in comparison to Pt/C, a lower peak potential of 0.08 V, a lower onset potential of 0.55 V, and a greater peak current density of 0.172 A cm−2 (Fig. 4c). For Pt2Rh/C, the If/Ib ratio was 1.9, which was twice as high as the value achieved for Pt/C. At a lowered overpotential, the exchange current density calculated using the Tafel slope was 1.5 × 10−6 A cm−2. Pt2Rh/C has a smaller Tafel slope (112 mV dec−1) compared to Pt/C (Fig. 4c, d). Further, they suggested that the synergistic effect between Rh and Pt metals made it simpler to convert CO–CO2 and quicker to break C–C bonds when Rh was present, which explained the increased electrocatalytic activity of Pt2Rh/C. These results have important implications for future work on DEFCs and electrochemical application-specific high-performance electrocatalyst design and development [54]. However, the expense of this catalyst is a significant concern for future studies on it. In order to reduce the cost of this catalyst, Bu et al. [55] reported having fabricated hierarchical Pt–Co nanowires (Pt3Co NWs/C) with high-index facets using a strong wet-chemical method. The electrocatalyst that was made has the same dense dendritic structure as the commercial Pt/C catalyst (58.8 m2 g−1), which means that it has the most electrochemically active surface area (52.1 m2 g−1). Because of this property, the electrocatalytic activity and stability during the EOR process were found to be superior as compared to commercial Pt and Pt/C, with a specific activity of 1.55 mA cm−2 and a great mass activity of 0.81 A mg−1. This work demonstrated that the incorporation of a cheap transition metal with Pt can benefit its electrocatalytic features towards EOR.

Fig. 4.

a TEM, and b HRTEM picture, c EOR LSVs (recorded in 1.0 M KOH + 1.0 M C2H5OH), and d Tafel plots, for the Pt2Rh/C catalyst. Taken with permission from [54]. Copyrights @2010, Elsevier. e TEM, and f HRTEM pictures of octahedral Pt2.3Ni. g CVs, and h Chronoamperometric plots for octahedral Pt2.3Ni recorded in 0.2 M C2H5OH + 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte.

Taken with permission from [56]. Copyrights @2017, American Chemical Society

Following the same approach, Suleiman et al. [56] created an electrocatalyst, octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C, with an average size of about 10 nm (Fig. 4e, f). The electrocatalytic activity in forward peak current density was about 2.4 times greater for the newly synthesized octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C catalyst than for commercial Pt/C and 3.7 times higher than for conventional Pt2Ni/C. Using in situ FTIR measurements, they tracked reaction intermediates and products and discovered that Pt/C was more selective for CO2 than CH3COOH. Nevertheless, decreased stability and activity can result from CO poisoning. By favoring C2 reaction pathways over C1, the octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C catalyst reduced CO poisoning and improved kinetics along C2 routes. Typically, the C1 route proceeds via 12 electron transfer, forming COads as an intermediate and later CO2 or carbonate in alkaline solutions. In contrast, under the same reaction conditions, the C2 route predominantly produces CH3COOH with the involvement of 4 electrons and CH3CHO with the involvement of 2 electrons. While the C1 pathway can attain higher electro-efficiency, the C2 pathway is typically more prevalent in the overall EOR. Hence, improving the C1 route through the strategic development of high-performance catalysts is a viable approach to enhancing DEFC's efficiency. The catalyst's activity was modulated by its structure and the interplay of two metals. The octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C catalyst outperformed the standard Pt2Ni/C by 2.4 times and Pt/C by 3.7 times, with a peak current density response of 1.46 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4g). In comparison to the regular Pt2Ni/C and Pt/C catalysts, the octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C catalyst exhibited a greater forward-to-backward peak current ratio, suggesting full ethanol oxidation, and stayed stable for 1800s (Fig. 4h). These results point to the possibility of the newly produced octahedral Pt2.3Ni/C catalyst as an efficient electrocatalytic ethanol oxidation catalyst.

In a similar way, Liu et al. [57] proposed a one-pot process for the synthesis of uniformly distributed monodisperse PtCu alloy polyhedrons with a size range of 4.6–5.1 nm. In comparison to Pt/C, the Pt68Cu32 nanoalloy demonstrated superior mass activity and specific activity. This catalyst displayed a current density of 11.8 mA cm−2 @2.31 A mg−1 at − 0.1 V versus Ag/AgCl. The Pt68Cu32 nanoalloy also had a much lower onset potential than Pt/C, which suggests that the C2H5OH oxidation process happened more quickly. In a 3600-s chronoamperometry experiment, the Pt68Cu32 nanoalloy had a much bigger and more stable current density response than the other materials that were tested. The calculated If/Ib ratio for the Pt68Cu32 nanoalloy was higher than that for Pt/C (1.89 vs. 1.21). It also absorbed less CO and made the EOR process easier. The finding suggested that the high density of edges, low coordination atoms, and corners on the PtCu nanoalloy surface is a result of its tiny, monodisperse polyhedral structure. The electrical and chemical properties of Pt metal were affected by ligand and strain effects when Cu and Pt were incorporated into the crystal phase. And the Pt d-band got smaller. Now, instead of harmful intermediates, Pt is weakly connected to OH− molecules that work in OER. All these features were responsible for the significant improvement in the catalytic performance of the Pt68Cu32 nanoalloy [57].

On the other hand, Bai et al. [58] used hydrothermal conditions and the straightforward complex-reduction synthetic process to create this bimetallic PtRh nanodendritic alloy. The different metal precursors and polyallylamines had different interaction strengths, which changed the initial reduction step throughout the synthesis. They conducted an extensive investigation into PtRh nanodendrites utilising a variety of physical and electrochemical techniques, paying special attention to their synthesis, structure, form, and electrocatalytic capabilities (Fig. 5a). The Rh crystal nuclei went through catalytic development and atomic inter-diffusion, which made a dendritic shape (Fig. 5b–d). It was shown that the pH and composition of Pt1Rh1 nanodendrite alloys affected their electrocatalytic activity for the EOR process. This electrocatalyst had better electrocatalytic activity, with a lower onset potential and a higher oxidation current. At 0.88 V versus RHE, the anodic current was eight times higher than that of the Pt nanocrystal electrocatalyst. When tested in basic media, this catalyst showed twice the electrocatalytic activity as compared to that observed in H2SO4 electrolyte (Fig. 5e–h). Because of changes in structure and chemistry, Pt1Rh1 nanodendrite alloys had better reaction kinetics in an alkaline solution [58].

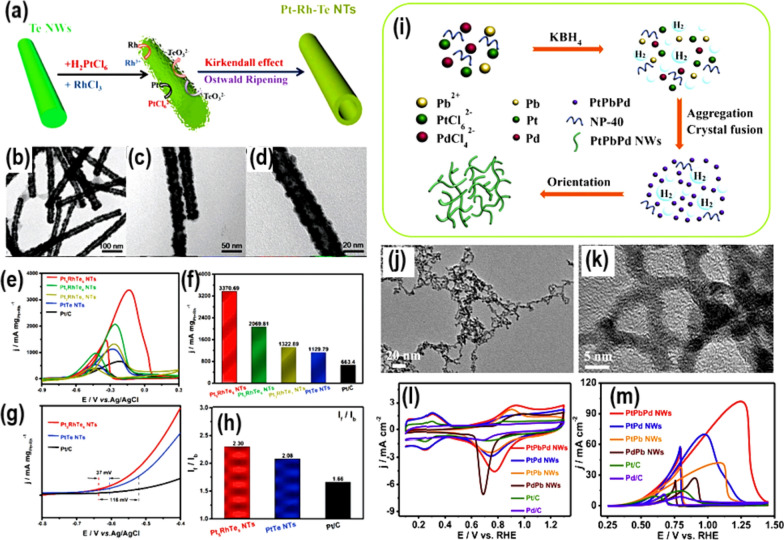

Fig. 5.

a Preparation scheme, and b–d TEM pictures of the prepared PtRhTe NTs catalysts. e CV curves (recorded in 1 M KOH + 1 M CH3CH2OH). f Histograms of mass activities. g CV Onset potential, and h The If/Ib ratios, for the prepared PtRhTe catalysts. Taken with permission from [58]. Copyrights @2018, ACS. i Synthesis scheme, j, k TEM pictures, and l, m CV curves (recorded before and after addition of 0.5 M C2H5OH in 0.5 M KOH), for PtPbPd NWs catalyst. Copyrights @2019, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Taken with permission from [60]. Copyrights @2019, Elsevier

Recently, Paulo et al. [59] used a novel Pechini method to prepare a CeO2-modified Pt-based electrode (1 and 5 wt%, respectively) to investigate the C2H5OH oxidation activity of Pt NPs (10–20 nm). The results consistently showed that the activity of Pt NPs was greatly enhanced by adding 1 wt% of CeO2. The catalyst's reduced micro-strain in comparison to pure Pt and the robust interaction between CeO2 and Pt were both found to be the reasons for the enhanced catalytic activity of the Pt electrode. Small amounts of CeO2 (Ce4+) changed the binding energy of Pt, and oxidised CeO2 reduced the strength of Pt–CO interactions and made CO oxidation to CO2 simpler.

In order to get more improvement in the catalytic activity of bimetallic Pt-based catalysts towards the EOR process, Duan et al. [60] fabricated ultrathin trimetallic nanowires of PtPbPd using an octyl-phenoxy-poly-ethoxy-ethanol-facilitated one-step aqueous approach under the effect of in situ-generated H2 bubbles as a dynamic template (Fig. 5i–k). The results suggested that the material's catalytic properties towards the EOR process were better than those of PtPd NWs, PdPb NWs, PtPb NWs, and commercial Pt/C (20 wt%). The most interesting things about the catalyst that was found in a 0.5 M KOH solution are that it is more stable over time, has more mass/specific activity, a better on-set potential, and a higher current density. The excellent catalytic performance of this catalyst was attributed to (i) electronic control and synergies among Pt, Pd, and Pb atoms and (ii) numerous open and accessible electroactive sites created by the interconnection of the nanowires (Fig. 5l, m) [60]. Following the similar approach, Zhang et al. [61] used octyl-phenoxy-poly-ethoxy-ethanol along with NaBr to fabricate an ordered multi-branched PdRuCu nano-assembly. The results indicated that the as-prepared PdRuCu-based catalyst was more stable, displaying remarkable electrocatalytic activity towards the EOR process with a 3.78 mA cm−2 current density and 1.16 A mg−1 specific and mass activity, as compared to commercial Pd/C (1.81 mA cm−2 and 0.17 A mg−1). In addition, a stability test was carried out with a peak potential of 0.97 V versus RHE and a maximum current density of 127 mA cm−2 maintained for 4000 s. Table 1 showed the EOR performance of some Pt-based electrocatalysts.

Table 1.

EOR performance of some Pt-based electrocatalysts

| Catalysts | Electrolytic solution | Peak potential (V vs. RHE) | Stability (s × 103) | Current density (mA cm−2) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoporous Pt | A | 0.855 | 1 | 24.30 | [48] |

| Concave Pt | B | 1.65 | – | 2.00 | [50] |

| Pt/MPC | B | 1.69 | 0.8 | 674.00 | [53] |

| Pt3-PEI | D | 0.77 | – | 197.00 | [62] |

| Pt3Co/C NWs | B | 1.00 | – | 14.20 | [55] |

| Pt2.3Ni/C | B | 0.92 | 1.8 | 1.50 | [56] |

| Pt–Mo–Ni NWs | C | 1.65 | 1.5 | 2.50 | [4] |

| Pt68Cu32 | A | 1.03 | 3.6 | 19.30 | [57] |

| Pt/Ru0.67 Sn0.33O2 | C | 1.65 | 3.5 | 113.20 | [63] |

| Pt23Pd77/C | A | 0.85 | 3.6 | 173.30 | [64] |

| Pt1Rh1 (dendritic) | A | 0.88 | 2 | 32.60 | [58] |

| Pt2Rh/C | A | 0.86 | – | 172.00 | [54] |

| Pt5RhTe6 | A | 0.88 | 3.5 | 247.20 | [65] |

| d-PtIr/C | B | 1.68 | 7.2 | 13.80 | [66] |

| h-ZrPt3 | C | 1.73 | 2 | 1.20 | [67] |

| PtPb0.27 NWs | B | 1.70 | 1 | 9.20 | [68] |

| PtPbPd NWs | D | 1.24 | 10 | 105.00 | [60] |

A = 1 M KOH + 1 M EtOH; B = 0.1 M HClO4 + 0.1 M EtOH; C = 0.5 M H2SO4 + 2.0 M EtOH; D = 0.5 M NaOH + 0.5 M EtOH

Incorporation of Pt-based materials with conductive support

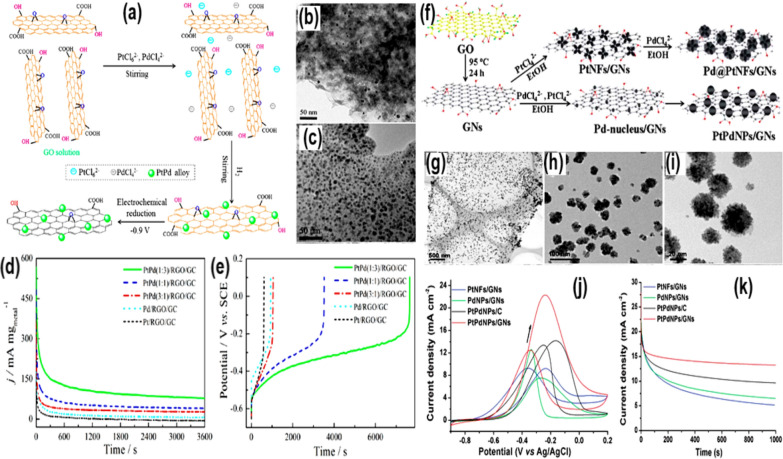

The findings in the last decades suggested that using conductive supports like graphene (Gr), graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and transition metal oxides, the catalytic stability and activity of the Pt-based electrocatalysts can be improved. Usually, the supporting materials offer the following salient characteristics: (i) large surface area; (ii) a solid catalyst-support contact; (iii) superior water handling; (iv) easy catalyst extraction; (v) mesoporous structure; and (vi) high resistance to corrosion in acidic environments. Considering the points, Ren et al. [69] reported having prepared a composite material, PtPd/rGO, with different Pt/Pd ratios (Fig. 6a). The characterization techniques suggested that the size of PtPd NPs was in the range of 4–7 nm with a well-controlled Pt–Pd precursor ratio (Fig. 6b, c). The electrochemical results showed that the PtPd/rGO (with a 1:3 ratio of Pt and Pd) catalyst was the most effective for the EOR process. The PtPd (1:3)/rGO catalyst performed better than either the Pt or Pd catalysts in a solution of 1.0 M KOH/1.0 M C2H5OH, displaying 105.9 mA cm−2 current density at a peak potential of − 0.3 V versus SCE, and this stable current response was sustained for a duration of 3600 s (Fig. 6d, e). According to the Hammer Norskov [69] d-band hypothesis, the ligand effect, the synergistic effect of the two metals, and the rGO support's huge surface area, high conductivity, and abundance of active sites all contributed to the enhanced catalytic activity.

Fig. 6.

a Preparation scheme, b, c TEM picture, d EOR chronoamperometric, and e EOR chrono-potentiometric plots (recorded in 1.0 M EtOH + 1.0 M KOH) for the prepared Pt, and Pd based catalysts. Taken with permission from [69]. Copyrights @2012, ACS. f Preparation scheme, g–i TEM pictures, j CV, and k chrono-potentiometric plots, for the prepared PtPdNPs/GNs based catalysts.

Taken with permission from [70]. Copyrights @2014. The Royal Society of Chemistry

Further, Chen et al. [70] incorporated the PtPd NPs on graphene nanosheets (PtPdNPs/GNs) to catalyze the EOR process (Fig. 6f). Following the same approach, a variety of metal NP structures were produced on GN surfaces, including nanoflowers of Pd@PtNFs, nanodendrites of Pt3Pd1NPs, and spherical NPs of Pt1Pd1NPs (Fig. 6g–i). In addition to increasing surface area, GNs improved the electron transfer mechanism during the EOR process. The high current density and negative onset potential of the PtPdNPs/GNs samples showed that they were more electrocatalytically active than the other samples. Because of the negative shift in the anodic onset potential, it is clear that C2H5OH on the PtPdNPs and GNs is easily oxidised. The PtPdNPs/GNs catalyst showed a peak current density of 22.4 mA cm−2 at − 0.1 V versus Ag/AgCl, which was about 2.5, 3.0, and 1.6 times greater than the PtNFs/GNs (9.1 mA cm−2), PdNPs/GNs (7.5 mA cm−2), and PtPdNPs/C (14.2 mA cm−2) catalysts, respectively (Fig. 6j, k). The results suggested that the enhanced electrocatalytic performance of PtPdNPs/GNs catalyst can be attributed to (i) the high surface area, which allowed the active sites to be finely dispersed; (ii) the removal of CO from the surfaces of metal nanoparticles due to functionalized GNs; (iii) appropriate interatomic Pt–Pt distances, which were more favorable for the facile adsorption of C–C bonds; (iv) the number of d-band vacancies, which increased when Pd was added to Pt, altering its electronic structure; and (v) the oxophilic characteristic of Pd, which enhanced the removal of CO from surfaces of Pt.

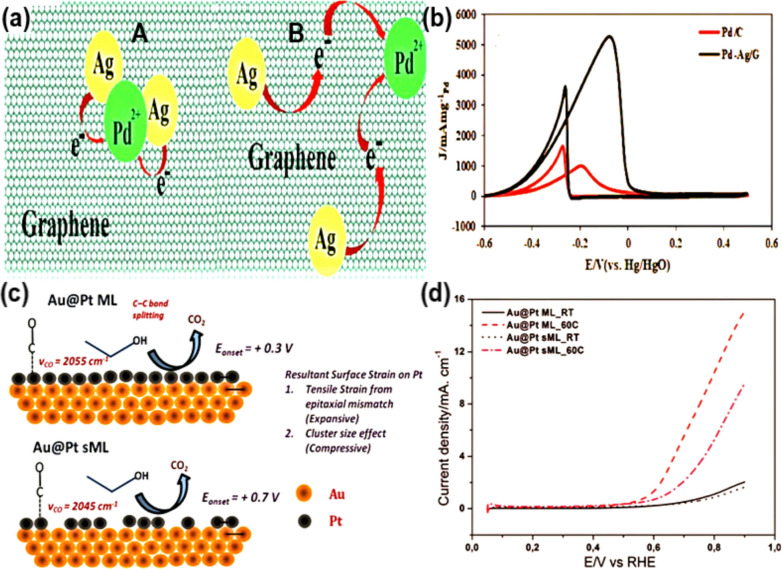

Douk et al. [71] on the other hand, suggested a straightforward, simple, low-temperature, surfactant-free way to improve the surface of graphene for Pd–Ag NPs that are evenly distributed and measure 2–3 nm. The fabricated catalyst (Pd–Ag/G) displayed excellent electrocatalytic performance in terms of high stability (over 7200 s), low activation energy, high If/Ib ratio, and high catalytic activity (J = 355 mA cm−2 at 0.82 V vs. RHE) towards the EOR process. The results showed that the Pd–Ag/G electrocatalyst worked better because (a) Pd and Ag were mixed together and (b) very small Pd–Ag NPs were spread out evenly. According to Hammer's theory, the adsorbate binding energy increased and Pd reactivity for CO oxidation was enhanced because the graphene support prevented particle agglomeration and the Pd d-band centre was raised following Ag incorporation, leading to the high surface area and excellent activity (Fig. 7a, b).

Fig. 7.

a A systematic illustration of direct (A), and indirect (B) mechanisms during the galvanic movement process. b CV plots, recorded in 1.0 M KOH/1.0 M C2H5OH, for Pd–Ag/G and Pd/C electrocatalysts. Taken from [71]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. c The graphical representation of the effect of Pt layer the prepared Au@Pt-based materials on vibrations of CO, used as probe, at C–C bonds breaking, and CO2 formation onset potentials during EOR process. d EOR LSVs the prepared Au@Pt-based materials (recorded in 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1 M C2H5OH).

Taken from [72]. Copyright 2014, Royal Society of Chemistry

Even though adding metal nanoparticles to graphene-based materials greatly increased their catalytic activity, the fact that the sheets of graphene still tend to stack on top of each other makes them less useful for large-scale use as catalyst supports. In order to overcome this issue, Kung et al. [73] used a 3D graphene foam with a huge surface area to support the hierarchically ordered Pt-Ru NPs. The PtRu NPs/3D GF did a great job of electrocatalyzing the EOR, and it was also less likely to get CO poisoning. A reduction in the size of the PtRu NPs on 3D graphene to 3.5 nm led to 186.2 m2 g−1, significantly enhanced active surface area. The PtRu/3D GF has approximately twice the EOR rates of PtRu/C and PtRu, displaying 78.6 mA cm−2 current density at 0.91 V versus SCE. The current density dropped to 25.5 mA cm−2 after 900 cycles while measuring the cycling stability. The If/Ib ratio of PtRu/3D GF is higher than that of PtRu and PtRu/C because it works better at oxidizing C2H5OH. The 3D multilayered graphene foam structure has a lot of surface area and conducting channels, which makes it a good electrode that can stand on its own and easily transfer charges. The surface of the graphene foam is also covered with metal nanoparticles that are spread out evenly. This prevents the materials from stacking together and gives the electrode catalytic activity a huge boost.

In order to use CNTs as support for Pt-based NPs, Loukrakpam et al. [72] functionalized CNTs with PtxMy NPs (M = Pd and Au; x and y = 1–3). The characterization results showed that CNTs' surface was evenly coated with PtAu NPs, which had spherical shapes and diameters between 2 and 6 nm, a large surface area of 206.6 m2 g−1, a low onset potential of 0.28 V, a high peak current density of 22.5 mA cm−2 at 0.62 V versus Ag/AgCl, minimal charge transfer resistances, a high If/Ib ratio of 0.88, durability of 800 cycles, and superior resistance to CO poisoning during the EOR process (Fig. 7c, d). The following three main factors of this catalyst are essentially responsible towards EOR process: (i) the functionalized CNTs' high conductivity, responsible for transferring e-among CNTs, catalysts as well as electrolyte; (ii) CO oxidation because of addition of a second metal, which had a synergistic effect; and (iii) the enhanced surface area and conductivity due to uniformly distributed small-size metal NPs on the CNTs. In conclusion, the study shows that functionalized CNTs might be useful as long-lasting alcohol oxidation catalysts that are not affected by CO poisoning. Table 2 showed the EOR performance of some Pt and Pd based nanocomposites.

Table 2.

EOR performance of some Pt and Pd based nanocomposites

| Catalyst | Electrolytic solution | Peak potential (V vs. RHE) | Stability (s × 103) | Current density (mA cm−2) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Pt3Cu1/GNPs | A | 0.72 | 3.6 | 42.4 | [74] |

| PtRu/3D GF | C | 1.96 | – | 78.6 | [73] |

| PtPd NPs/GNs | D | 0.82 | 1 | 22.4 | [70] |

| PtPd (1:3)/rGO | A | 0.77 | 3.6 | 105.9 | [69] |

| D-PtPd/rGO | A | 0.97 | 4 | 210.0 | [75] |

| Pt70Pd24Ni6/rGO | A | 0.80 | – | ~ 79.0 | [76] |

| PtAu/CNTs | C | 1.68 | – | 22.5 | [77] |

| Pd/NS-rGO | D | 0.90 | 7 | 74.8 | [78] |

| Pd–PdOx | D | 0.90 | – | 14.0 | [79] |

| Pd/Cu/Gr | A | 0.80 | 3.5 | 26.6 | [80] |

| PdCo NTAs/CFC | A | 0.98 | 0.6 | 11.7 | [81] |

| PdCo@ NPNCs | A | 0.84 | 8 | 176.4 | [82] |

| FePd–Fe3C/MWNTs | A | 0.90 | 1 | 84.8 | [83] |

| Pd–Ni/CNF | A | 0.77 | 1.8 | 199.8 | [84] |

A = 1 M KOH + 1 M EtOH; B = 0.1 M HClO4 + 0.1 M EtOH; C = 0.5 M H2SO4 + 2.0 M EtOH; D = 0.5 M NaOH + 0.5 M EtOH

Technical factors impacting DEFC’s performance

Harmony between electrocatalysis and electrode system

In the bulk of experiments on DEFCs, the catalytic interface, whether supported or unsupported, has often been implemented using either a catalyst-coated membrane (CCM) or a catalyst-coated diffusion layer (CCDL). Both topologies play a significant role in electrode design and are often referred to as gas diffusion electrodes. These electrodes may be characterized by the presence of a microporous gas diffusion and distribution zone, as well as a thin layer mostly composed of mesoporous materials. The gas diffusion electrode membrane assembly is formed by subjecting all the layers to hot pressing. Extensive practical and theoretical investigations have been undertaken into the assembly of gas diffusion electrodes and membranes. The utilization efficiency of the catalyst in a gas diffusion electrode is typically limited to a range of 10–50%. Consequently, the fuel utilization efficiency of this kind of electrode may be suboptimal, leading to an elevated crossover rate across the membrane and subsequently impacting the cathodic performance. In this context, Wilkinson et al. [85] introduced a unique multi-layer anode design aimed at enhancing alcohol utilization efficiency in FCs. This design involves the stacking of several CCDLs to expand the volume of the reaction zone. An increase in alcohol utilization efficiency of 33% was seen when carbon-supported Pt-Ru catalysts were spread across three distinct diffusion layers, compared to a single CCDL.

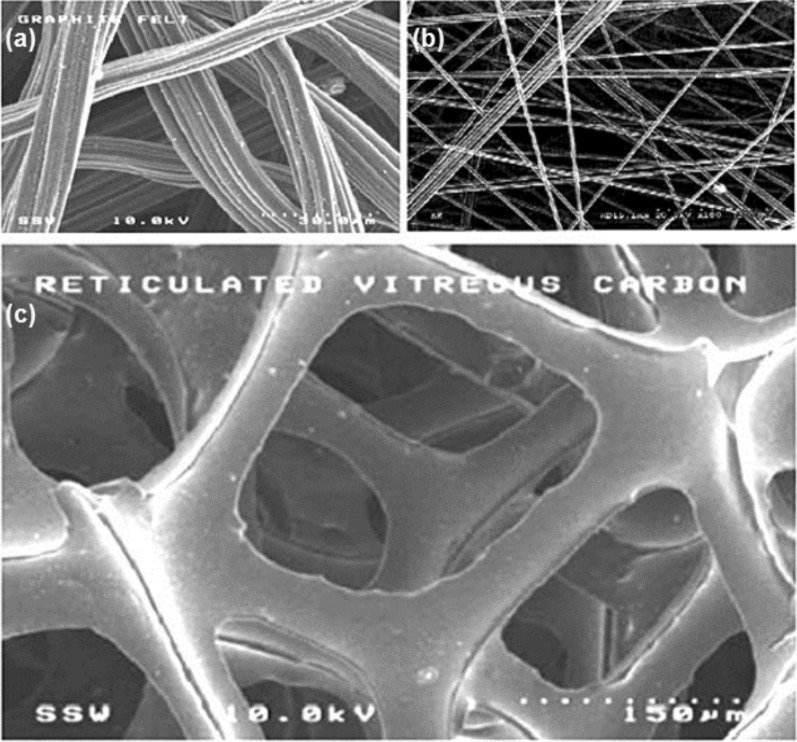

This observation was made under constant current density conditions of 200 mA cm−2 at a temperature of 388 K while maintaining the total anode catalyst loading constant. The use of a 3D matrix for the purpose of evenly dispersing an electrocatalyst has the potential to provide an expanded reaction zone for fuel electro-oxidation. The function of 3D support is complex and has an impact on the mass transfer characteristic as well as the interaction between the catalyst and the support material. The use of a support system has the potential to enhance multiphase mass transfer in the direct cell anode compared to the gas diffusion electrode. In the second scenario, the equilibrium gas bubble pressure is described by Laplace's equation. The presence of mass and micropores in the catalyst layer restricts the growth and detachment of the gas bubbles from the surface. As a result, the CO2 molecules dissociate from the catalyst layer, leading to a decrease in the effective electrolyte conductivity. This disturbance in the current distribution causes an increase in the concentration of the overpotential of the reactant in the liquid phase. Micropores of larger diameters (> 50 nm) have a greater propensity for bubble development, coalescence, and detachment, as shown in Fig. 8a–c. Additionally, the presence of local gas evolution may enhance the transport of reactant mass to the surface, thereby reducing the concentration of overpotential.

Fig. 8.

Examples of three-dimensional supports for extended reaction zone anodes DMFCs. a undressed graphite felt UGF. Adapted with permission [86]. Copyright @2006, Elsevier. b pressed graphite felt GF, c reticulated vitreous carbon RVC.

Adapted with permission [87]. Copyright @2006, Elsevier

Incorporation of conductive polymer supports

Utilization of conducive polymers (like polyaniline (PAni)) as catalyst supports can offer the well-dispersion of the catalyst’s NPs in the catalyst layer, superior physical and chemical stability, enhanced electronic interaction with the catalyst, and favourable surface properties that facilitate the transport and adsorption of reaction species [88]. For instance, Hable et al. [89] used Pt-Ru/PAni and Pt–Sn/PAni materials for the EOR process. The polymer matrix was combined with the catalyst by potential cycling deposition on PAni/GC. PAni offered good electronic conductivity that enhanced the electro-kinetics of the EOR process. In a similar way, the Pt–Sn catalyst supported by PAni exhibited the highest level of EOR activity, although both Pt-Ru and Pt–Sn catalysts showed sensitivity towards the electro-oxidation of alcohol. However, the formed reaction intermediates showed a detrimental impact on the performance of PAni [89]. Further, a comparative investigation was conducted to assess the deposition of a Pt electrode on carbon in comparison to PAni-modified carbon. The findings revealed that the latter instance exhibited superior performance in terms of alcohol oxidation current density at a potential of 0.5 V versus SCE [90]. Also, the granular form of PAni, which is a simple polymer form made by electro-polymerization in H2SO4, is much better than the fibrous form of PAni made in HBF4 or HClO4 [91]. This advantage is attributed to both the high surface area and the well dispersion of the catalyst, as the same quantity of Pt catalyst used with granular PAni results in approximately six times higher alcohol oxidation compared to fibrous PAni.

Conclusions

In summary, this review presents a comprehensive analysis of the electrocatalytic ethanol oxidation reaction, several methods of enhancing the kinetics of this reaction through Pt-based nanoengineering, technological hurdles associated with DEFCs, recent advancements in the field, current obstacles, and possible future prospects. Clean and inexpensive energy sources have the potential to address numerous global health, energy, and environmental challenges. The current era's primary urgency is the substitution of finite fossil fuels with fuel cells, specifically direct alcohol fuel cells, that necessitate the use of cost-effective, plentiful, and effective materials. Because of their unique electrocatalytic properties, noble metals such as Pt and Pd are considered favorable electrocatalysts for the EOR process in DEFCs. However, their limited availability and exorbitant cost have impeded their widespread marketability. Unlike materials with fewer noble metals, these materials are chemically stable in both basic and acidic environments, making them suitable for use across the entire pH spectrum. This review paper provided a comprehensive examination of the fundamental chemistry that controls ethanol oxidation using platinum (Pt) electrocatalysts for the advancement of direct ethanol fuel cells (DEFCs). The main focus of this work was on the catalytic system, which includes the basic chemistry of direct ethanol fuel cells (DEFCs), anode engineering, and the parameters that influence DEFCs' performance. The design of the diffusion catalyst layer involved a thorough investigation of the interaction between the catalyst, support, and other chemical species, with particular emphasis on understanding their dynamics. The ability of DEFCs to attain optimal performance and cost-effectiveness relies on developments in both electrocatalysis and electrochemical engineering.

Despite significant advancements, the following obstacles persist, necessitating additional study prior to widespread commercial use of DEFCs: (i) The C–C bond must be broken during C2H5OH electro-oxidation. The C2H5OH undergoes partial oxidation to CH3COOH or CH3CHO (a 2–4 electron process), even though full oxidation requires 12 electrons. The generation of these reaction intermediates is capable of blocking the active sites of the catalysts, reducing the overall efficiency of the DEFCs. Therefore, in order to achieve ideal OER without the use of costly noble metals, a very active EOR catalyst is needed. (ii) Researchers are showing interest in metal NP phase engineering as a promising future approach because of the significant impact that nanoparticle size, shape, and architecture can have on electrocatalytic activity. However, the precise control of this feature of the catalyst is still a very challenging task. In this context, one viable alternative would be to use a surfactant-free synthesis approach to produce single-metal atom NPs with demonstrated electrocatalytic activity and standard crystal phases. (iii) In order to attain a high level of electrocatalytic activity, further research is needed to comprehend the basic relationship of conductive support with the metal sites at the interface. Therefore, using in situ characterization techniques, including differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS), in situ FTIR spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy, a full picture of the reaction mechanism and the steps that control the activity should be investigated in the near future. In this case, studying kinetics can help a lot with making an electrocatalyst that is more active and stable. Theoretical and simulation studies can help us learn more about catalytic mechanisms, active site structures, intrinsic reactivities, and reaction intermediates. DFT calculations can effectively be used to evaluate the electrocatalytic performance, the electric double layer's geometrical and electronic structures, and the design of electrocatalysts made of metals or non-metals more effectively. (iv) The long-term cyclic stability test shows absence of strong bond of catalyst with supporting material. This is true even though the hybrid structural design is an effective way to spread the electrocatalyst evenly on the support surface. To understand the catalyst's stability during EOR, post-analysis of its composition, structure, and morphology should be explored. (v) It is crucial to study how an electrocatalyst performs in relation to temperature during the EOR process and to find the exact temperature range that maximizes a catalyst's efficiency. (vi) To enhance contact with the electrode material, it is necessary to enhance the electrolyte diffusibility between the membrane and electrodes. Therefore, binary and ternary composites should be investigated for the EOR process because their regulated shape and composition create unique paths and mechanisms that produce outstanding performance. (vii) Besides the above parameters, the technical issues related to electrolyte content, ethanol concentration, oxidant flow rate, moisture and heat management, and membrane thickness should be thoroughly investigated to achieve greater efficiency in DEFCs. (viii) While an electrocatalyst's performance in an acidic electrolyte is significantly worse than in an alkaline medium DEFC, there are still a number of issues that can occur from the presence of a base, such as a decrease in the membrane's ionic conductivity and a decrease in the electrode's hydrophobicity. Therefore, in order to achieve the catalyst's exceptional electrocatalytic performance, it is necessary to resolve these challenges.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to GLA University for providing infrastructural support during this work.

Author contributions

JK wrote the original draft. AK and RKG supervised the project throughout.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jasvinder Kaur, Email: jasvinderkaur2911@gmail.com.

Anuj Kumar, Email: anuj.kumar@gla.ac.in.

References

- 1.Periasamy P, Mohanta YK. Global energy crisis: need for energy conversion and storage, green nanomaterials in energy conversion and storage applications. Palm Bay: Apple Academic Press; 2024. p. 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar A, Vashistha VK, Das DK. Recent development on metal phthalocyanines based materials for energy conversion and storage applications. Coord Chem Rev. 2021;431:213678. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A, Zhang Y, Liu W, Sun X. The chemistry, recent advancements and activity descriptors for macrocycles based electrocatalysts in oxygen reduction reaction. Coord Chem Rev. 2020;402:213047. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaqoob L, Noor T, Iqbal N. A comprehensive and critical review of the recent progress in electrocatalysts for the ethanol oxidation reaction. RSC Adv. 2021;11:16768–804. 10.1039/D1RA01841H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han A, Wang B, Kumar A, Qin Y, Jin J, Wang X, Yang C, Dong B, Jia Y, Liu J. Recent advances for MOF-derived carbon-supported single-atom catalysts. Small Methods. 2019;3:1800471. 10.1002/smtd.201800471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao W, Li M, Hu S. Insight into the ordering process and ethanol oxidation performance of Au–Pt–Cu ternary alloys. Dalton Trans. 2024;53:8750–5. 10.1039/D4DT00553H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H, Guo T, Yin D, Liu Q, Zhang X. A high-efficiency noble metal-free electrocatalyst of cobalt-iron layer double hydroxides nanorods coupled with graphene oxides grown on a nickel foam towards methanol electrooxidation. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2020;112:212–21. 10.1016/j.jtice.2020.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kianfar S, Golikand AN, Zare Nezhad BJ. Nanostruct Chem. 2020;4:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Lao X, Yang L, Fu A, Guo P. Assembly of trimetallic palladium-silver-copper nanosheets for efficient C2 alcohol electrooxidation. Sci China Mater. 2023;66:150–9. 10.1007/s40843-022-2104-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q, Lu X, Xin Q, Sun G. Polyol-synthesized Pt2.6Sn1Ru0.4/C as a high-performance anode catalyst for direct ethanol fuel cells. Chin J Catal. 2014;35:1394–401. 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60063-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badreldin A, Youssef E, Djire A, Abdala A, Abdel-Wahab A. A critical look at alternative oxidation reactions for hydrogen production from water electrolysis. Cell Reports Physical Science. 2023;4:101427. 10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perazio A. Electrolyzer and catalyst engineering for acidic CO2 reduction. Paris: Sorbonne Université; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braunchweig B, Hibbitts D, Neurock M, Wieckowski A. Electrocatalysis: a direct alcohol fuel cell and surface science perspective. Catal Today. 2013;202:197–209. 10.1016/j.cattod.2012.08.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yougui C, Zhuang L, Juntao L. Non-Pt anode catalysts for alkaline direct alcohol fuel cells. Chin J Catal. 2007;28:870–4. 10.1016/S1872-2067(07)60073-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badwal S, Giddey S, Kulkarni A, Goel J, Basu S. Direct ethanol fuel cells for transport and stationary applications—a comprehensive review. Appl Energy. 2015;145:80–103. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lao X, Liao X, Chen C, Wang J, Yang L, Li Z, Ma JW, Fu A, Gao H, Guo P. Pd-enriched-core/Pt-enriched-shell high-entropy alloy with face-centred cubic structure for C1 and C2 alcohol oxidation. Angew Chem. 2023;135:e202304510. 10.1002/ange.202304510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dybiński O, Milewski J, Szabłowski Ł, Szczęśniak A, Martinchyk A. Methanol, ethanol, propanol, butanol and glycerol as hydrogen carriers for direct utilization in molten carbonate fuel cells. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2023;48:37637–53. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.05.091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Zhao J, Sun Y, Yang X, Chen J. Facile synthesis of Ni/sepiolite and its excellent performance toward electrocatalytic ethanol oxidation. J Appl Electrochem. 2024;54:519–30. 10.1007/s10800-023-01990-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamarudin M, Kamarudin S, Masdar M, Daud W. Direct ethanol fuel cells. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2013;38:9438–53. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.07.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J, Zhao T, Li Y, Yang W. Synthesis and characterization of the Au-modified Pd cathode catalyst for alkaline direct ethanol fuel cells. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2010;35:9693–700. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.06.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An L, Zhao T, Li Y. Carbon-neutral sustainable energy technology: direct ethanol fuel cells. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;50:1462–8. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.05.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueiredo MC, Santasalo-Aarnio A, Vidal-Iglesias FJ, Solla-Gullon J, Feliu JM, Kontturi K, Kallio T. Tailoring properties of platinum supported catalysts by irreversible adsorbed adatoms toward ethanol oxidation for direct ethanol fuel cells. Appl Catal B. 2013;140:378–85. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.04.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James DD, Pickup PG. Effects of crossover on product yields measured for direct ethanol fuel cells. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55:3824–9. 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song S, Zhou W, Tian J, Cai R, Sun G, Xin Q, Kontou S, Tsiakaras P. Ethanol crossover phenomena and its influence on the performance of DEFC. J Power Sources. 2005;145:266–71. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2004.12.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heysiattalab S, Shakeri M, Safari M, Keikha M. Investigation of key parameters influence on performance of direct ethanol fuel cell (DEFC). J Ind Eng Chem. 2011;17:727–9. 10.1016/j.jiec.2011.05.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, He Y, Yang W. Performance characteristics of air-breathing anion-exchange membrane direct ethanol fuel cells. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2013;38:13427–33. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.07.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Zhao T, Liang Z. Effect of polymer binders in anode catalyst layer on performance of alkaline direct ethanol fuel cells. J Power Sources. 2009;190:223–9. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.01.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alzate V, Fatih K, Wang H. Effect of operating parameters and anode diffusion layer on the direct ethanol fuel cell performance. J Power Sources. 2011;196:10625–31. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.08.080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishnoi P, Mishra K, Siwal SS, Gupta VK, Thakur VK. Direct ethanol fuel cell for clean electric energy: unravelling the role of electrode materials for a sustainable future. Adv Energy Sustain Res. 2024;5:2300266. 10.1002/aesr.202300266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Clament Sagaya Selvam N, Fang J. Shape-controlled synthesis of platinum-based nanocrystals and their electrocatalytic applications in fuel cells. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023;15:83. 10.1007/s40820-023-01060-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews T, Mbokazi SP, Dolla TH, Gwebu SS, Mugadza K, Raseruthe K, Sikeyi LL, Adegoke KA, Saliu OD, Adekunle AS. Electrocatalyst performances in direct alcohol fuel cells: defect engineering protocols, electrocatalytic pathways, key parameters for improvement, and breakthroughs on the horizon, small. Science. 2024;4:2300057. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halder A, Sharma S, Hegde M, Ravishankar N. Controlled attachment of ultrafine platinum nanoparticles on functionalized carbon nanotubes with high electrocatalytic activity for methanol oxidation. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:1466–73. 10.1021/jp8072574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang Y, Pyo JB, Ye X, Gordon TR, Murray CB. Synthesis, shape control, and methanol electro-oxidation properties of Pt–Zn alloy and Pt3Zn intermetallic nanocrystals. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5642–7. 10.1021/nn301583g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Yang Z, Tang X, Zhang J, Lv G. Hydrogen production through distinctive C–C cleavage during acetic acid reforming at low temperature. ChemSusChem. 2024;17:e202301532. 10.1002/cssc.202301532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jablonski A, Kulesza PJ, Lewera A. Oxygen permeation through Nafion 117 membrane and its impact on efficiency of polymer membrane ethanol fuel cell. J Power Sources. 2011;196:4714–8. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.01.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taneda K, Yamazaki Y. Study of direct type ethanol fuel cells: analysis of anode products and effect of acetaldehyde. Electrochim Acta. 2006;52:1627–31. 10.1016/j.electacta.2006.03.093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddington E, Sapienza A, Gurau B, Viswanathan R, Sarangapani S, Smotkin ES, Mallouk TE. Combinatorial electrochemistry: a highly parallel, optical screening method for discovery of better electrocatalysts. Science. 1998;280:1735–7. 10.1126/science.280.5370.1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Y, Cui X, Yen CH, Wai CM. PtRu/carbon nanotube nanocomposite synthesized in supercritical fluid: a novel electrocatalyst for direct methanol fuel cells. Langmuir. 2005;21:11474–9. 10.1021/la051272o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikuma Y, Niwa K, Imamura T. Thermodynamically spontaneous reactions and use of acetaldehyde as fuel in direct ethanol fuel cells. ECS Adv. 2023;2:044501. 10.1149/2754-2734/ad040b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh B, Mahapatra S. Performance study of palladium modified platinum anode in direct ethanol fuel cells: a green power source. J Indian Chem Soc. 2023;100:100876. 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramli ZAC, Pasupuleti J, Zaiman NFHN, Saharuddin TST, Samidin S, Isahak WNRW, Sofiah A, Kamarudin SK, Tiong SK. Evaluating electrocatalytic activities of Pt, Pd, Au and Ag-based catalyst on PEMFC performance: a review. Int J Hydrog Energy. (2024).

- 42.Jiang Y, Li S, Fan X, Tang Z. Recent advances on aerobic photocatalytic methane conversion under mild conditions. Nano Res. 2023;16:12558–71. 10.1007/s12274-023-6244-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding J, Teng Z, Su X, Kato K, Liu Y, Xiao T, Liu W, Liu L, Zhang Q, Ren X. Asymmetrically coordinated cobalt single atom on carbon nitride for highly selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH. Chem. 2023;9:1017–35. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu EH, Krewer U, Scott K. Principles and materials aspects of direct alkaline alcohol fuel cells. Energies. 2010;3:1499–528. 10.3390/en3081499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Gao W, Wan Z, Wan X, Ye J, Gao J, Wen D. Confining N‐doped carbon dots into PtNi aerogels skeleton for robust electrocatalytic methanol oxidation and oxygen reduction. Small, 2024; 2400158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Camara GA, De Lima R, Iwasita T. The influence of PtRu atomic composition on the yields of ethanol oxidation: a study by in situ FTIR spectroscopy. J Electroanal Chem. 2005;585:128–31. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2005.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gyenge E. Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol, ethanol and formic acid. In: PEM fuel cell electrocatalysts and catalyst layers: fundamentals and applications. Springer; 2008. pp. 165–287.

- 48.Dimos MM, Blanchard G. Evaluating the role of Pt and Pd catalyst morphology on electrocatalytic methanol and ethanol oxidation. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:6019–26. 10.1021/jp911076b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar A, Kuang Y, Liang Z, Sun X. Microwave chemistry, recent advancements, and eco-friendly microwave-assisted synthesis of nanoarchitectures and their applications: A review. Mater Today Nano. 2020;11:100076. 10.1016/j.mtnano.2020.100076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang X, Zhao Z, Fan J, Tan Y, Zheng N. Amine-assisted synthesis of concave polyhedral platinum nanocrystals having 411 high-index facets. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4718–21. 10.1021/ja1117528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren X, Lv Q, Liu L, Liu B, Wang Y, Liu A, Wu G. Current progress of Pt and Pt-based electrocatalysts used for fuel cells. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2020;4:15–30. 10.1039/C9SE00460B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vyas AN, Saratale GD, Sartale SD. Recent developments in nickel based electrocatalysts for ethanol electrooxidation. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2020;45:5928–47. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen M-H, Jiang Y-X, Chen S-R, Huang R, Lin J-L, Chen S-P, Sun S-G. Synthesis and durability of highly dispersed platinum nanoparticles supported on ordered mesoporous carbon and their electrocatalytic properties for ethanol oxidation. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:19055–61. 10.1021/jp1091398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen S, Zhao T, Xu J. Carbon supported PtRh catalysts for ethanol oxidation in alkaline direct ethanol fuel cell. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2010;35:12911–7. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.08.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu K-H, Zhang C, Berry GJ, Altman RB, Ré C, Rubin DL, Snyder M. Predicting non-small cell lung cancer prognosis by fully automated microscopic pathology image features. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12474. 10.1038/ncomms12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sulaiman JE, Zhu S, Xing Z, Chang Q, Shao M. Pt–Ni octahedra as electrocatalysts for the ethanol electro-oxidation reaction. ACS Catal. 2017;7:5134–41. 10.1021/acscatal.7b01435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu T, Wang K, Yuan Q, Shen Z, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Wang X. Monodispersed sub-5.0 nm PtCu nanoalloys as enhanced bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction and ethanol oxidation reaction. Nanoscale. 2017;9:2963–8. 10.1039/C7NR00193B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bai J, Xiao X, Xue Y-Y, Jiang J-X, Zeng J-H, Li X-F, Chen Y. Bimetallic platinum–rhodium alloy nanodendrites as highly active electrocatalyst for the ethanol oxidation reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:19755–63. 10.1021/acsami.8b05422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paulo MJ, Venancio RH, Freitas RG, Pereira EC, Tavares AC. Investigation of the electrocatalytic activity for ethanol oxidation of Pt nanoparticles modified with small amount (≤ 5 wt%) of CeO2. J Electroanal Chem. 2019;840:367–75. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duan J-J, Feng J-J, Zhang L, Yuan J, Zhang Q-L, Wang A-J. Facile one-pot aqueous fabrication of interconnected ultrathin PtPbPd nanowires as advanced electrocatalysts for ethanol oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2019;44:27455–64. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang R-L, Duan J-J, Han Z, Feng J-J, Huang H, Zhang Q-L, Wang A-J. One-step aqueous synthesis of hierarchically multi-branched PdRuCu nanoassemblies with highly boosted catalytic activity for ethanol and ethylene glycol oxidation reactions. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;506:144791. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mourdikoudis S, Chirea M, Altantzis T, Pastoriza-Santos I, Pérez-Juste J, Silva F, Bals S, Liz-Marzán LM. Dimethylformamide-mediated synthesis of water-soluble platinum nanodendrites for ethanol oxidation electrocatalysis. Nanoscale. 2013;5:4776–84. 10.1039/c3nr00924f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hang H, Altarawneh RM, Brueckner TM, Pickup PG. Pt/Ru–Sn oxide/carbon catalysts for ethanol oxidation. J Electrochem Soc. 2020;167:054518. 10.1149/1945-7111/ab7f9e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Q, Chen T, Jiang R, Jiang F. Comparison of electrocatalytic activity of Pt 1–x Pd x/C catalysts for ethanol electro-oxidation in acidic and alkaline media. RSC Adv. 2020;10:10134–43. 10.1039/D0RA00483A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin L, Xu H, Chen C, Shang H, Wang Y, Wang C, Du Y. Porous Pt–Rh–Te nanotubes: an alleviated poisoning effect for ethanol electrooxidation. Inorg Chem Front. 2020;7:625–30. 10.1039/C9QI01249D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee Y-W, Hwang E-T, Kwak D-H, Park K-W. Preparation and characterization of PtIr alloy dendritic nanostructures with superior electrochemical activity and stability in oxygen reduction and ethanol oxidation reactions. Catal Sci Technol. 2016;6:569–76. 10.1039/C5CY01054C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramesh GV, Kodiyath R, Tanabe T, Manikandan M, Fujita T, Umezawa N, Ueda S, Ishihara S, Ariga K, Abe H. Stimulation of electro-oxidation catalysis by bulk-structural transformation in intermetallic ZrPt3 nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:16124–30. 10.1021/am504147q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang N, Guo S, Zhu X, Guo J, Huang X. Hierarchical Pt/Pt x Pb core/shell nanowires as efficient catalysts for electrooxidation of liquid fuels. Chem Mater. 2016;28:4447–52. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ren F, Wang H, Zhai C, Zhu M, Yue R, Du Y, Yang P, Xu J, Lu W. Clean method for the synthesis of reduced graphene oxide-supported PtPd alloys with high electrocatalytic activity for ethanol oxidation in alkaline medium. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:3607–14. 10.1021/am405846h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen X, Cai Z, Chen X, Oyama M. Green synthesis of graphene–PtPd alloy nanoparticles with high electrocatalytic performance for ethanol oxidation. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:315–20. 10.1039/C3TA13155F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Douk AS, Saravani H, Farsadrooh M, Noroozifar M. An environmentally friendly one-pot synthesis method by the ultrasound assistance for the decoration of ultrasmall Pd-Ag NPs on graphene as high active anode catalyst towards ethanol oxidation. Ultrason Sonochem. 2019;58:104616. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loukrakpam R, Yuan Q, Petkov V, Gan L, Rudi S, Yang R, Huang Y, Brankovic SR, Strasser P. Efficient C–C bond splitting on Pt monolayer and sub-monolayer catalysts during ethanol electro-oxidation: Pt layer strain and morphology effects. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:18866–76. 10.1039/C4CP02791D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kung C-C, Lin P-Y, Xue Y, Akolkar R, Dai L, Yu X, Liu C-C. Three dimensional graphene foam supported platinum–ruthenium bimetallic nanocatalysts for direct methanol and direct ethanol fuel cell applications. J Power Sources. 2014;256:329–35. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.01.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang G, Yang Z, Zhang W, Hu H, Wang C, Huang C, Wang Y. Tailoring the morphology of Pt 3 Cu 1 nanocrystals supported on graphene nanoplates for ethanol oxidation. Nanoscale. 2016;8:3075–84. 10.1039/C5NR08013D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li S-S, Zheng J-N, Ma X, Hu Y-Y, Wang A-J, Chen J-R, Feng J-J. Facile synthesis of hierarchical dendritic PtPd nanogarlands supported on reduced graphene oxide with enhanced electrocatalytic properties. Nanoscale. 2014;6:5708–13. 10.1039/C3NR06808K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhunia K, Khilari S, Pradhan D. Monodispersed PtPdNi trimetallic nanoparticles-integrated reduced graphene oxide hybrid platform for direct alcohol fuel cell. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:7769–78. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Themsirimongkon S, Sarakonsri T, Lapanantnoppakhun S, Jakmunee J, Saipanya S. Carbon nanotube-supported Pt-Alloyed metal anode catalysts for methanol and ethanol oxidation. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2019;44:30719–31. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.04.145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang J, Yang X, Shao H, Tseng C, Wang D, Tian S, Hu W, Jing C, Tian J, Zhao Y. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Pd oxide-rich Pd particles on nitrogen/sulfur Co-doped graphene with remarkably enhanced ethanol electrooxidation. Fuel Cells. 2017;17:115–22. 10.1002/fuce.201600153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krittayavathananon A, Duangdangchote S, Pannopard P, Chanlek N, Sathyamoorthi S, Limtrakul J, Sawangphruk M. Elucidating the unexpected electrocatalytic activity of nanoscale PdO layers on Pd electrocatalysts towards ethanol oxidation in a basic solution. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2020;4:1118–25. 10.1039/C9SE00848A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dong Q, Zhao Y, Han X, Wang Y, Liu M, Li Y. Pd/Cu bimetallic nanoparticles supported on graphene nanosheets: facile synthesis and application as novel electrocatalyst for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2014;39:14669–79. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang AL, He XJ, Lu XF, Xu H, Tong YX, Li GR. Palladium–cobalt nanotube arrays supported on carbon fiber cloth as high-performance flexible electrocatalysts for ethanol oxidation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:3669–73. 10.1002/anie.201410792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Z, Liu S, Tian X, Wang J, Xu P, Xiao F, Wang S. Facile synthesis of N-doped porous carbon encapsulated bimetallic PdCo as a highly active and durable electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and ethanol oxidation. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5:10876–84. 10.1039/C7TA00710H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Y, He Q, Guo J, Wang J, Luo Z, Shen TD, Ding K, Khasanov A, Wei S, Guo Z. Ultrafine FePd nanoalloys decorated multiwalled cabon nanotubes toward enhanced ethanol oxidation reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:23920–31. 10.1021/acsami.5b06194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maiyalagan T, Scott K. Performance of carbon nanofiber supported Pd–Ni catalysts for electro-oxidation of ethanol in alkaline medium. J Power Sources. 2010;195:5246–51. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.03.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wouters B, Hereijgers J, De Malsche W, Breugelmans T, Hubin A. Electrochemical characterisation of a microfluidic reactor for cogeneration of chemicals and electricity. Electrochim Acta. 2016;210:337–45. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.05.187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shao Z-G, Lin W-F, Zhu F, Christensen PA, Li M, Zhang H. Novel electrode structure for DMFC operated with liquid methanol. Electrochem Commun. 2006;8:5–8. 10.1016/j.elecom.2005.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bauer A, Gyenge EL, Oloman CW. Electrodeposition of Pt–Ru nanoparticles on fibrous carbon substrates in the presence of nonionic surfactant: application for methanol oxidation. Electrochim Acta. 2006;51:5356–64. 10.1016/j.electacta.2006.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Diaz A, Logan J. Electroactive polyaniline films. J Electroanal Chem Interfacial Electrochem. 1980;111:111–4. 10.1016/S0022-0728(80)80081-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hable CT, Wrighton MS. Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol and ethanol: a comparison of platinum-tin and platinum-ruthenium catalyst particles in a conducting polyaniline matrix. Langmuir. 1993;9:3284–90. 10.1021/la00035a085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Niu L, Li Q, Wei F, Wu S, Liu P, Cao X. Electrocatalytic behavior of Pt-modified polyaniline electrode for methanol oxidation: effect of Pt deposition modes. J Electroanal Chem. 2005;578:331–7. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2005.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kitani A, Akashi T, Sugimoto K, Ito S. Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol on platinum modified polyaniline electrodes. Synth Met. 2001;121:1301–2. 10.1016/S0379-6779(00)01522-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.