Graphical Abstract

Key Words: cardiac masses, outcomes, treatment planning

Cardiac benign metastatic leiomyoma (BML) is a rare, but unique, occurrence that probably stems from the uterine leiomyoma (ULM) and entails a distinct pattern of tumor development involving the displacement of uterine muscle cells and implantation into the right side of the heart.1 Despite incomplete understanding of its pathogenesis, BML demonstrates a strong association with a precedent or concurrent history of ULM. This case report presents the management of a patient with BML attached to the Thebesian valve in the right atrium (RA), accompanied by multiple pulmonary metastases and a paraspinal mass. We also review the diagnosis and management of BML to raise awareness among clinicians about a rare, yet challenging, condition that is difficult to diagnose.

Case presentation

A 50-year woman was referred to our institute in March 2023 for the management of incidentally diagnosed RA mass suspicious of myxoma or thrombus on echocardiography. Patient was asymptomatic for chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope, hemoptysis, transient ischemic attacks, or stroke. Her past medical history was significant for myomectomy in 2008 and 2010, uterine rupture at 26 weeks of pregnancy in 2012 requiring emergent surgery, and supracervical hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and excision of parasitic urinary bladder mass in February 2022 for menorrhagia. Histopathology confirmed ULM with no evidence of malignancy in uterine, ovarian, and bladder mass specimens.

To delineate the nature of the mass, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed that demonstrated a 20 × 12-mm soft tissue mass located in the inferior aspect of RA, adjacent to the interatrial septum suspicious of myxoma. In addition, there were multiple pulmonary nodules (right > left) and a 3-cm enhancing soft tissue mass in the left paraspinal musculature. Positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET-CT) was negative for malignancy. Computed tomography (CT) guided biopsy of the left paraspinal mass and right upper lobe lung mass demonstrated smooth muscle tumor with minimal atypia that was positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, and estrogen receptor (ER), and negative for CD117, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), melanoma associated antigen recognized by T cells-1 (MART-1), CD34, pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), and S100 on immunohistochemical staining. The Mindbomb homolog-1 (MiB1)/Kiel-67 (Ki-67) proliferative index was <1%. Based on these findings, presumptive diagnosis of BML or low-grade leiomyosarcoma was made; the nature of the cardiac mass, however, remained unclear. To elucidate the nature of the cardiac mass and prevent the risk of pulmonary embolism, in July 2023, the patient underwent cardiac surgery through a median sternotomy under normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass without arresting the heart. Aorto-bicaval cannulation was performed, and cavae were snared. Right atriotomy was performed, and a 20 × 10-mm pedunculated mass attached to the Thebesian valve was excised completely along with the Thebesian valve. Right atriotomy was repaired and the patient weaned-off cardiopulmonary bypass without any problems. Patient made an uneventful recovery. Histopathology and immunohistochemical (Figure 1) staining of the mass confirmed leiomyoma that stained positive for ER, desmin, actin, and Wilms’ tumor-1 (WT-1), and had negative results for S-100, myogenin, and keratin. Chromosomal microarray analysis demonstrated gain of 1q21.1q32.1, and loss of 1p36.33p35.1, 1q42.12q44 (including fumarate hydratase [FH]), 2p25.3q14.3, 10q22.1q26.3 (including phosphatase and tensin homolog [PTEN]), 14q22.1q24.1 with a focal homozygous loss of 14q24.1 (disrupting RAD51 paralog B [RAD51B]), and 19q13.32q13.43. Immunohistochemical examination demonstrated normal expression of FH and S-(2-succinyl)- cysteine (2SC). These results conclusively established the diagnosis of BML. At last follow-up 6 months after surgery, the patient was doing well, in NYHA functional class I with a stable size of her pulmonary and paraspinal masses.

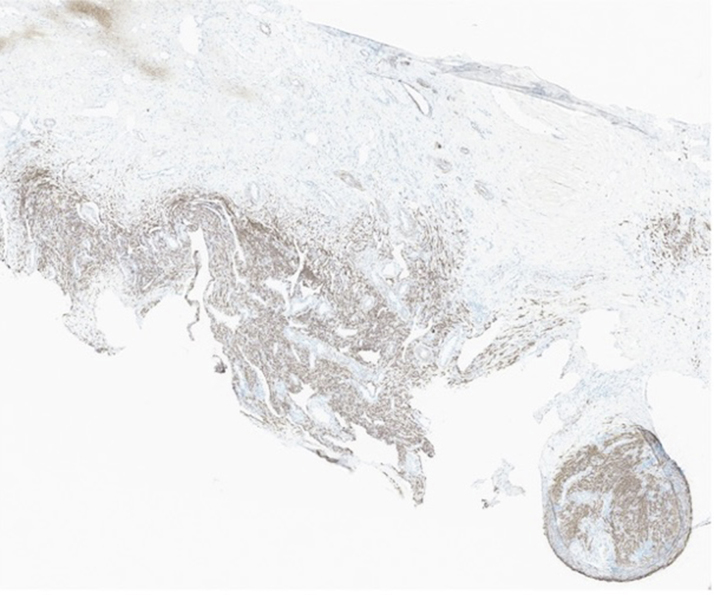

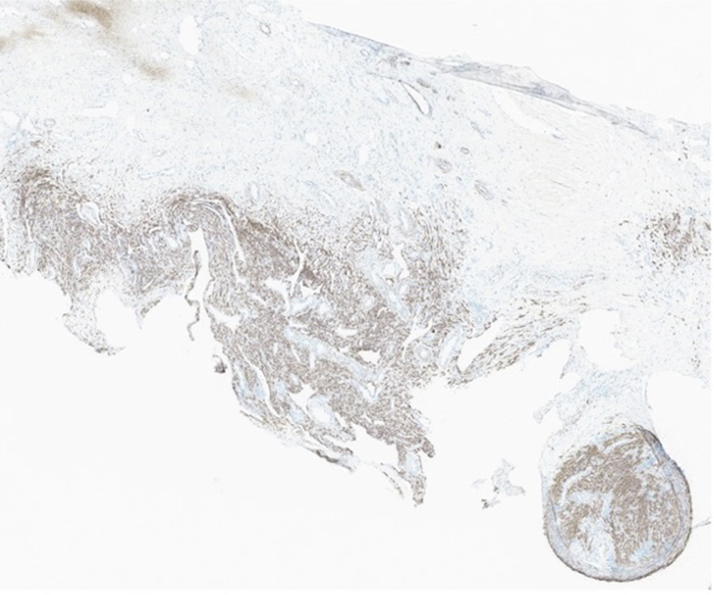

Figure 1.

Immunohistopathology of the Right Atrial Mass

Immunohistopathology of the right atrial mass at 40× magnification showing tumor cells diffusely positive for muscle markers desmin.

Discussion

Uterine leiomyomas constitute the most common benign uterine tumors in women in their reproductive years.2 Although rare, ULM may metastasize to any organ including the heart, with lungs being the most common site. Although BML can be metastatic, the tumor is truly benign with spread to various organs and tissues from the uterine leiomyoma by detachment of muscle cells that are spread via uterine veins. This is further substantiated by the fact that despite dissemination to various organs, this neoplasm demonstrates a remarkably slow growth rate. Moreover, the tumor does not recur after complete excision of metastatic lesions.

Among 15 cases of cardiac BML reported in the literature including ours, all were women who were >35 years at the time of diagnosis, and most had a prior history of myomectomy or hysterectomy. The tumor was unilobed or multilobed; single or multiple; and size ranged from 20 to >90 mm. Two-thirds of the patients had metastasis to the right ventricle with or without tricuspid valve (TV) involvement, whereas an RA tumor was reported in only 2 patients including our patient. Smaller tumors were asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed, whereas large tumors usually presented with dyspnea or as an emergency with TV obstruction. Most patients had concomitant extracardiac metastasis. Complete resection of the cardiac tumor was possible in all except 1 patient, and 6 patients required simultaneous TV repair or replacement3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 7 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Management and Outcome of Patients With Benign Metastatic Leiomyoma

| Subject No. | First Author | Cardiac Mass Resection | Additional Cardiac Procedure | Additional Procedure | Cardiac Mass Immunohistochemical Stain (PR, ER Status) | Follow-Up Duration | Hormonal Therapy | Outcome | Fate of Extracardiac Masses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Takemura et al11 | Yes | Tricuspid valve replacement, permanent pacemaker placement | Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Positive | 20 mo | LHRH analogue | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 2 | Galvin et al9 | Yes | None | None | Positive | 18 mo | Not reported | Alive No recurrence |

None |

| 3 | Cai et al12 | No (Multiple cardiac masses unamenable for resection and no hemodynamic compromise) | None | Hysterectomy without oophorectomy Abdominal wall nodule resection; Oophorectomy offered during follow due to increase in mass size, but patient refused |

Cardiac mass not resected Positive in other metastatic sites |

2 y | LHRH analogue | Alive No recurrence Masses enlarged |

Increased in size as patient stopped antihormone therapy due to side effects |

| 4 | Consamus et al1 | Yes | None | None | Positive | 16 mo | Not reported | Alive no recurrence |

Not reported |

| 5 | Williams et al2 | Yes | No | None; Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy recommended 3 m after cardiac surgery |

Positive Ki-67 <10% |

2 mo | Aromatase inhibitor then GnRH analogue | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 6 | Meddeb et al3 | Yes | Tricuspid valve repair | None | Positive Ki-67 <10% |

6 mo | Aromatase inhibitor | Alive No recurrence |

Stable |

| 7 | Gad et al4 | Yes | Tricuspid valve repair | None | Positive | Not reported | GnRH analogue | Alive No recurrence Right heart failure post-surgery |

Slight shrinkage of pelvic mass |

| 8 | Karnib et al13 | Yes | No | None | Positive KI-67 <2% |

3 y | Progestin receptor modulator | Alive No recurrence RV failure |

Pulmonary masses were stable But pelvic mass increased |

| 9 | Li et al14 | Yes | No | None | Positive KI-67 <2% |

12 mo | No | Alive No recurrence |

None |

| 10 | Reis Soares et al5 | Yes | Tricuspid valve replacement | Pelvic mass resection | Positive | Not reported | No | Alive No recurrence |

None |

| 11 | Jaber et al6 | Yes | Tricuspid valve replacement | Planned for hysterectomy and antihormonal therapy | Positive | Not reported | Proposed | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 12 | Morimoto et al15 | Yes | No | None | Positive | 18 mo | Yes | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 13 | Pfenniger et al7 | Yes | Tricuspid valve repair | None | Positive | Not reported | No | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 14 | Thukkani et al8 | Yes | Tricuspid valve replacement | Laparotomy for intra-abdominal hemorrhage | Not reported | 12 mo | GnRH analogue | Alive No recurrence |

Not reported |

| 15 | Index patient | Yes | No | Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy Bladder mass |

Positive Ki-67 <1% |

4 mo | No | Alive No recurrence |

Patient still due for follow-up |

ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor.

Due to its rarity, our understanding about the origin of cardiac BML is limited. Dislodgment of uterine muscle cells into the uterine veins following surgical intervention for ULM remains the most widely acknowledged hypothesis. This is further substantiated by the fact that cardiac BML is almost always associated with metastasis to 1 or more extracardiac sites, and there is a lag period of years between ULM intervention and the diagnosis of cardiac BML.7 Invariable expression of ER and progesterone receptors (PR), a nonrandom pattern of genetic alterations including loss of genetic material involving various chromosomes and high mobility group A-1 (HMGA1) rearrangement, and long or very long telomere length seen in BML also substantiate that both BML and ULM have a common origin and that BML arises from cytogenetically abnormal ULM. Further, 40% of ULMs harbor nonrandom structural abnormality including balanced translocations and deletions. The metastatic potential of ULMs has been attributed to HMGA1 locus rearrangements in the presence of 1p, 19q, and/or 22q chromosome deletion. Our patient also had loss of 19q and 1p. All these substantiate that BMLs are clonally derived from phenotypically benign, but karyotypically abnormal, ULMs that harbor genetic alterations that impart the ability to metastasize.9 Further, cytogenetic testing of extrauterine leiomyomas can aid in the diagnosis of BML, whereas cytogenetic analysis of the myomectomy or hysterectomy specimens can help in predicting the future risk of metastasis of ULM. Presence of these aberrations should alert the physician to keep the patient under close surveillance for the development of BML.

Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of any specific diagnostic features, it is important to consider potential alternative diagnoses, for example, thrombus, cardiac myxoma, and primary cardiac leiomyoma. BML may be confused with well-differentiated uterine leiomyosarcoma. However, in BML, smooth muscle cells are normal appearing with minimal atypia, no or minimal necrosis and vascularization, mitotic index is <10%, anaplasia and tissue invasion are absent, telomeres are long or very long, and cytogenetic aberrations are less complex with a balanced karyotype.1,10

Cardiac BML is mostly seen incidentally as a cardiac mass on echocardiography while evaluating for other conditions. Echocardiography is an important initial modality to characterize the nature of mass and rule out any significant right ventricular inflow or outflow obstruction. To distinguish cardiac BML from the other cardiac masses, and to diagnose concomitant extracardiac thoracic metastasis, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI chest scans are preferred modalities.3 In addition, CT or MRI scans of the abdomen and brain should be performed to investigate the other sites of metastasis, and PET-CT to rule out the malignant nature of the masses. Newer modalities such as dual radiolabeled 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) and 18-F fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) PET-CT may provide useful information about ER expression and glucose metabolism, and carries the potential for targeted antihormonal therapy in the future.3 Core biopsy of an extracardiac mass may give a clue, but the diagnosis of cardiac BML may remain elusive until the resection of the cardiac mass, as in our patient.

For management, complete resection of cardiac BML is the treatment of choice as it is safe, usually feasible, and prevents recurrence and potential complications. Management of concomitant extracardiac BML, however, depends upon the site, size, and number of masses and accessibility for surgical excision. Wherever feasible, complete surgical excision of extracardiac BMLs is the treatment of choice. When complete surgical excision is not feasible, or there is residual tumor, and in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women; surgical castration in form of BSO should be performed. Surgical castration in most cases regresses or at least stabilizes the extracardiac BML. Patients should remain under close follow-up with CT surveillance, as there have been reports of tumor progression despite the surgical castration. This is especially true in patients on hormone replacement therapy and in postmenopausal women, probably due to the small amount of estrogen produced from the extra-ovarian sites, or the influence of other non-ovarian steroid hormones and nonhormonal factors.1,8

Young patients who undergo complete surgical excision of cardiac and extracardiac BML can be followed closely without BSO or antihormonal therapy. Patients who have undergone BSO can also be followed up without initiating antihormonal therapy. Young patients with residual or recurrent BML should preferably undergo surgical castration due to its superiority over medical castrations in terms of residual tumor regression, and prevention of tumor growth and recurrence. However, for patients who wish to preserve their ovaries, medical castration using aromatase inhibitors, ER blockers, and gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists should be considered. Patients should be followed closely with CT surveillance, both for the compliance as well as tumor progression, and persuaded to have surgical castration if there is continued tumor progression at any site.2, 3, 4,11, 12, 13

Conclusions

Among the potential diagnostic considerations for cardiac masses, cardiac BML, although rare, should be acknowledged. Diagnosis is facilitated by comprehensive imaging and supplemented with pathological and cytogenetic assessment. To prevent the recurrence and avert the risk of potentially fatal obstructive and embolic complications, complete surgical excision of cardiac and extra-cardiac BML is strongly recommended. Long-term surveillance is advised to ensure comprehensive monitoring and optimal patient care.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Consamus E.N., Reardon M.J., Ayala A.G., Schwartz M.R., Ro J.Y. Metastasizing leiomyoma to heart. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014;10(4):251–254. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-10-4-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams M., Salerno T., Panos A.L. Right ventricular and epicardial tumors from benign metastasizing uterine leiomyoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(2):e21–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meddeb M., Chow R.D., Whipps R., Haque R. The heart as a site of metastasis of benign metastasizing leiomyoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Cardiol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/7231326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gad M.M., Găman M.A., Bazarbashi N., Friedman K.A., Gupta A. Suspicious right heart mass: a rare case of benign metastasizing leiomyoma of the tricuspid valve. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis Soares R., Ferber Drumond L., Soares da Mata D., Miraglia Firpe L., Tavares Mendonça Garretto J.V., Ferber Drumond M. Cardiac metastasizing leiomyoma: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;77:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.11.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaber M., Winner P.J., Krishnan R., Shu R., Khandelwal K.M., Shah S. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma causing severe tricuspid regurgitation and heart failure. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2023;11 doi: 10.1177/23247096231173397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfenniger A., Silverberg R.A., Lomasney J.W., Churyla A., Maganti K. Unusual case of right ventricular intravenous leiomyoma. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(8) doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.010363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thukkani N., Ravichandran P.S., Das A., Slater M.S. Leiomyomatosis metastatic to the tricuspid valve complicated by pelvic hemorrhage. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(2):707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton K.T., Cheng L., Papavero V., et al. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma: clonality, telomere length and clinicopathologic analysis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(1):130–140. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvin S.D., Wademan B., Chu J., Bunton R.W. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma: a rare metastatic lesion in the right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(1):279–281. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takemura G., Takatsu Y., Kaitani K., et al. Metastasizing uterine leiomyoma. A case with cardiac and pulmonary metastasis. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192(6):622–629. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80116-6. discussion 630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai A., Li L., Tan H., Mo Y., Zhou Y. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma. Case report and review of the literature. Herz. 2014;39(7):867–870. doi: 10.1007/s00059-013-3904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karnib M., Rhea I., Elliott R., Chakravarty S., Al-Kindi S.G. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma in the heart of a 45-year-old woman. Tex Heart Inst J. 2021;48(1) doi: 10.14503/THIJ-19-7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J., Zhu H., Hu S.Y., Ren S.Q., Li X.L. Case report: cardiac metastatic leiomyoma in an Asian female. Front Surg. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.991558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimoto Y., Sato M., Yamada A., Gan K. Large right ventricle cardiac leiomyoma metastasis from uterine leiomyoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(12) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2022-252389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]