Abstract

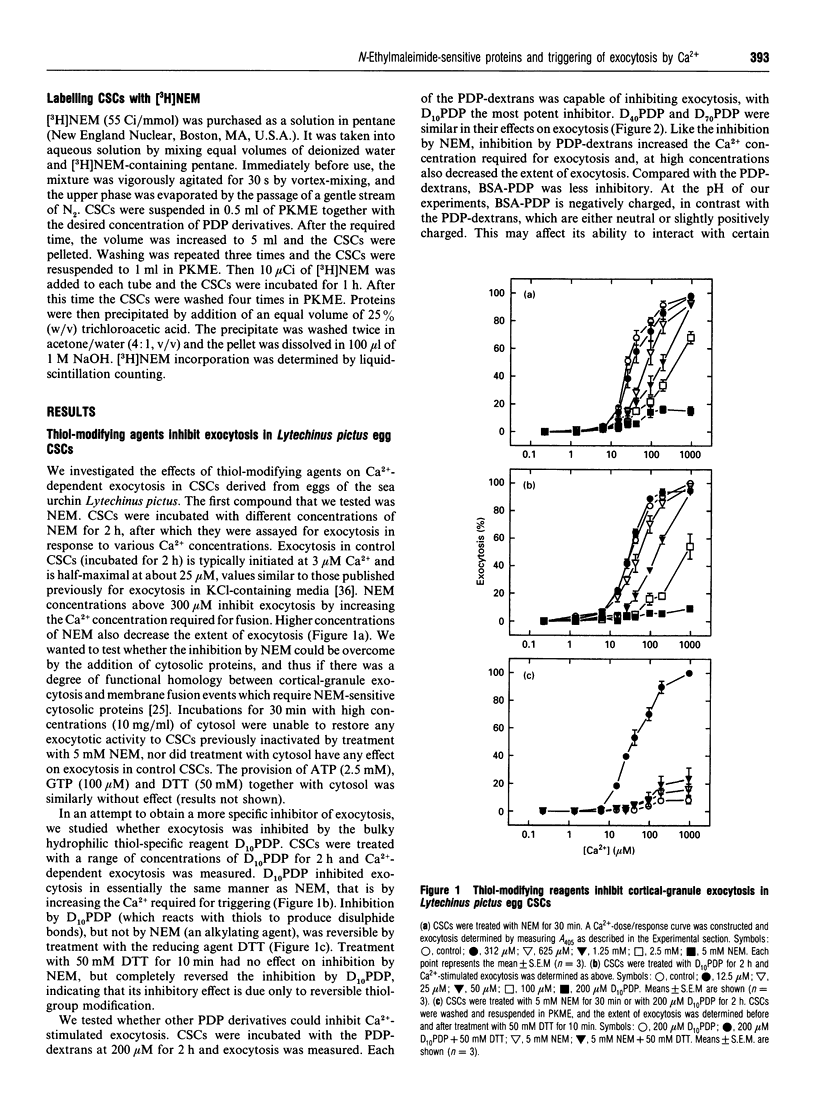

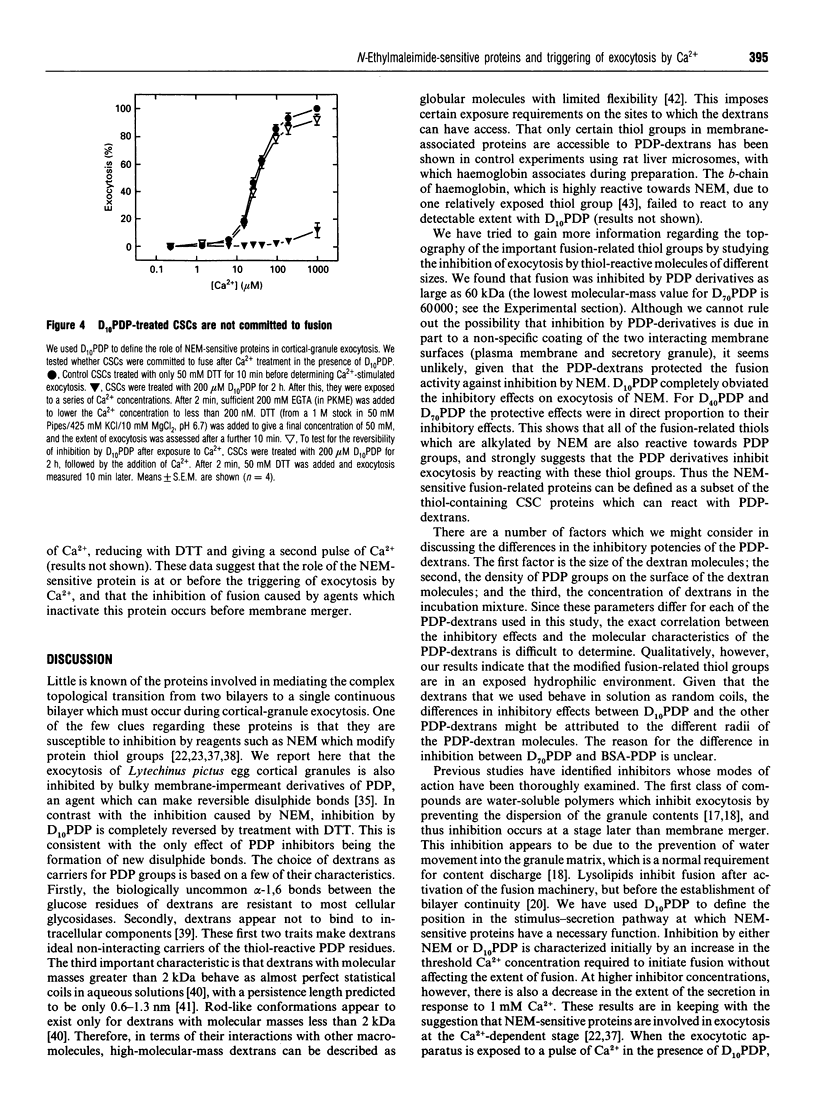

It is known that sea-urchin egg cortical-granule exocytosis is inhibited by agents such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) which modify thiol groups. The fusion-related proteins modified by these agents have yet to be identified, nor is there information regarding the topography of these thiol groups. Furthermore, the step in cortical-granule exocytosis at which these thiol groups participate is unknown. In this study we have investigated the topological properties of, and the temporal requirement for the function of, the fusion-related thiol groups by treating the isolated exocytotic apparatus with high-molecular-mass dextrans and BSA carrying thiol-reactive 3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate groups. The dextran derivatives inhibited exocytosis. The BSA derivative was much less inhibitory. Inhibition was reversed by treatment with dithiothreitol. When NEM was added to the dextran-derivative-treated exocytotic apparatus, treatment with dithiothreitol completely reversed inhibition, indicating that the dextran derivatives inhibit by reacting at the NEM-sensitive sites. A pulse of Ca2+ applied in the presence of inhibitors did not trigger any fusion following the removal of the inhibitor by dithiothreitol. These data show that the thiol groups, the modification of which by NEM inhibits exocytosis, are exposed to the medium in terms of their accessibility to macromolecules. They also show that the fusion-related thiol groups are required during the Ca(2+)-dependent stage of exocytosis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson E. Oocyte differentiation in the sea urchin, Arbacia punctulata, with particular reference to the origin of cortical granules and their participation in the cortical reaction. J Cell Biol. 1968 May;37(2):514–539. doi: 10.1083/jcb.37.2.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. F., Whitaker M. J. Influence of ATP and calcium on the cortical reaction in sea urchin eggs. Nature. 1978 Nov 30;276(5687):513–515. doi: 10.1038/276513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers C. J., Block M. R., Glick B. S., Rothman J. E., Balch W. E. Vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi stack requires the NEM-sensitive fusion protein. Nature. 1989 Jun 1;339(6223):397–398. doi: 10.1038/339397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. Regulated exocytosis. Biochem J. 1993 Jul 15;293(Pt 2):305–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2930305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson J., Drevin H., Axén R. Protein thiolation and reversible protein-protein conjugation. N-Succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate, a new heterobifunctional reagent. Biochem J. 1978 Sep 1;173(3):723–737. doi: 10.1042/bj1730723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D. E., Whitaker M., Zimmerberg J. High molecular weight polymers block cortical granule exocytosis in sea urchin eggs at the level of granule matrix disassembly. J Cell Biol. 1989 Sep;109(3):1269–1278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomordik L. V., Vogel S. S., Sokoloff A., Onaran H. O., Leikina E. A., Zimmerberg J. Lysolipids reversibly inhibit Ca(2+)-, GTP- and pH-dependent fusion of biological membranes. FEBS Lett. 1993 Feb 22;318(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley I., Whalley T., Whitaker M. Guanosine 5'-thiotriphosphate may stimulate phosphoinositide messenger production in sea urchin eggs by a different route than the fertilizing sperm. Cell Regul. 1991 Feb;2(2):121–133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R., Mayorga L. S., Weidman P. J., Rothman J. E., Stahl P. D. Vesicle fusion following receptor-mediated endocytosis requires a protein active in Golgi transport. Nature. 1989 Jun 1;339(6223):398–400. doi: 10.1038/339398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye R. A., Holz R. W. Arachidonic acid release and catecholamine secretion from digitonin-treated chromaffin cells: effects of micromolar calcium, phorbol ester, and protein alkylating agents. J Neurochem. 1985 Jan;44(1):265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y., Pfeffer S. R. Identification of a novel, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive cytosolic factor required for vesicular transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1991 Mar;112(5):823–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goud B., McCaffrey M. Small GTP-binding proteins and their role in transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991 Aug;3(4):626–633. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90033-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty J. G., Jackson R. C. Release of granule contents from sea urchin egg cortices. New assay procedures and inhibition by sulfhydryl-modifying reagents. J Biol Chem. 1983 Feb 10;258(3):1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. C., Modern P. A. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive protein(s) involved in cortical exocytosis in the sea urchin egg: localization to both cortical vesicles and plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 1990 Jun;96(Pt 2):313–321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. C., Ward K. K., Haggerty J. G. Mild proteolytic digestion restores exocytotic activity to N-ethylmaleimide-inactivated cell surface complex from sea urchin eggs. J Cell Biol. 1985 Jul;101(1):6–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye P. V., van der Merwe P. A., Millar R. P., Davidson J. S. Arachidonic acid-induced LH release is ATP-independent and insensitive to N-ethyl maleimide. J Endocrinol. 1992 Jan;132(1):77–82. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1320077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau M., Gomperts B. D. Techniques and concepts in exocytosis: focus on mast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991 Dec 12;1071(4):429–471. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(91)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby-Phelps K., Lanni F., Taylor D. L. Behavior of a fluorescent analogue of calmodulin in living 3T3 cells. J Cell Biol. 1985 Oct;101(4):1245–1256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan P. T., Wang J. T., Alston K., Rifkind J. M. Spin label probes of the environment of cysteine beta-93 in hemoglobin. Hemoglobin. 1990;14(1):41–67. doi: 10.3109/03630269009002254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsigny M., Petit C., Roche A. C. Colorimetric determination of neutral sugars by a resorcinol sulfuric acid micromethod. Anal Biochem. 1988 Dec;175(2):525–530. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy G. W., Kopf G. S., Gache C., Vacquier V. D. Calcium-mediated release of glucanase activity from cortical granules of sea urchin eggs. Dev Biol. 1983 Dec;100(2):267–274. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor V., Augustine G. J., Betz H. Synaptic vesicle exocytosis: molecules and models. Cell. 1994 Mar 11;76(5):785–787. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner H., Lumpert C. J., Knoll G., Kissmehl R., Höhne B., Momayezi M., Glas-Albrecht R. Stimulus-secretion coupling in Paramecium cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991 Jun;55(1):3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov S. V., Poo M. M. Synaptotagmin: a calcium-sensitive inhibitor of exocytosis? Cell. 1993 Jul 2;73(7):1247–1249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90352-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. E., Orci L. Molecular dissection of the secretory pathway. Nature. 1992 Jan 30;355(6359):409–415. doi: 10.1038/355409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H., Epel D. Cortical vesicle exocytosis in isolated cortices of sea urchin eggs: description of a turbidometric assay and its utilization in studying effects of different media on discharge. Dev Biol. 1983 Aug;98(2):327–337. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H. Modulation of calcium sensitivity by a specific cortical protein during sea urchin egg cortical vesicle exocytosis. Dev Biol. 1984 Jan;101(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt R. A., Alderton J. M. Calmodulin confers calcium sensitivity on secretory exocytosis. Nature. 1982 Jan 14;295(5845):154–155. doi: 10.1038/295154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt R., Zucker R., Schatten G. Intracellular calcium release at fertilization in the sea urchin egg. Dev Biol. 1977 Jul 1;58(1):185–196. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K., Whitaker M. The part played by inositol trisphosphate and calcium in the propagation of the fertilization wave in sea urchin eggs. J Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;103(6 Pt 1):2333–2342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söllner T., Bennett M. K., Whiteheart S. W., Scheller R. H., Rothman J. E. A protein assembly-disassembly pathway in vitro that may correspond to sequential steps of synaptic vesicle docking, activation, and fusion. Cell. 1993 Nov 5;75(3):409–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof T. C., De Camilli P., Niemann H., Jahn R. Membrane fusion machinery: insights from synaptic proteins. Cell. 1993 Oct 8;75(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagaya M., Wilson D. W., Brunner M., Arango N., Rothman J. E. Domain structure of an N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein involved in vesicular transport. J Biol Chem. 1993 Feb 5;268(4):2662–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. R., Jaffe L. A., Fein A. Regulation of cortical vesicle exocytosis in sea urchin eggs by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and GTP-binding protein. J Cell Biol. 1986 Jan;102(1):70–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. R., Jaffe L. A., Primakoff P. A cholera toxin-sensitive G-protein stimulates exocytosis in sea urchin eggs. Dev Biol. 1987 Apr;120(2):577–583. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacquier V. D. The isolation of intact cortical granules from sea urchin eggs: calcium lons trigger granule discharge. Dev Biol. 1975 Mar;43(1):62–74. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. S., Chernomordik L. V., Zimmerberg J. Calcium-triggered fusion of exocytotic granules requires proteins in only one membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992 Dec 25;267(36):25640–25643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. S., Leikina E. A., Chernomordik L. V. Lysophosphatidylcholine reversibly arrests exocytosis and viral fusion at a stage between triggering and membrane merger. J Biol Chem. 1993 Dec 5;268(34):25764–25768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. S., Zimmerberg J. Proteins on exocytic vesicles mediate calcium-triggered fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 May 15;89(10):4749–4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley T., Crossley I., Whitaker M. Phosphoprotein inhibition of calcium-stimulated exocytosis in sea urchin eggs. J Cell Biol. 1991 May;113(4):769–778. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley T., Whitaker M. Exocytosis reconstituted from the sea urchin egg is unaffected by calcium pretreatment of granules and plasma membrane. Biosci Rep. 1988 Aug;8(4):335–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01115224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker M. J., Baker P. F. Calcium-dependent exocytosis in an in vitro secretory granule plasma membrane preparation from sea urchin eggs and the effects of some inhibitors of cytoskeletal function. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1983 Jul 22;218(1213):397–413. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker M. How calcium may cause exocytosis in sea urchin eggs. Biosci Rep. 1987 May;7(5):383–397. doi: 10.1007/BF01362502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker M., Zimmerberg J. Inhibition of secretory granule discharge during exocytosis in sea urchin eggs by polymer solutions. J Physiol. 1987 Aug;389:527–539. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg J., Whitaker M. Irreversible swelling of secretory granules during exocytosis caused by calcium. Nature. 1985 Jun 13;315(6020):581–584. doi: 10.1038/315581a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]