Abstract

Purpose:

Biliary tract lesions are comparatively rare neoplasms, with ambiguous indications for radiotherapy. The specific aim of this study was to report the clinical results of a single-institution biliary tract series treated with modern radiotherapeutic techniques, and detail results using both conventional and image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IG-IMRT).

Methods and materials:

From 2001 to 2005, 24 patients with primary adenocarcinoma of the biliary tract (gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts) were treated by IG-IMRT. To compare outcomes, data from a sequential series of 24 patients treated between 1995 and 2005 with conventional radiotherapy (CRT) techniques were collected as a comparator set. Demographic and treatment parameters were collected. Endpoints analyzed included treatment-related acute toxicity and survival.

Results:

Median estimated survival for all patients completing treatment was 13.9 months. A statistically significant higher mean dose was given to patients receiving IG-IMRT compared to CRT, 59 vs. 48 Gy. IG-IMRT and CRT cohorts had a median survival of 17.6 and 9.0 months, respectively. Surgical resection was associated with improved survival. Two patients (4%) experienced an RTOG acute toxicity score > 2. The most commonly reported GI toxicities (≽RTOG Grade 2) were nausea or diarrhea requiring oral medication, experienced by 46% of patients.

Conclusion:

This series presents the first clinical outcomes of biliary tract cancers treated with IG-IMRT. In comparison to a cohort of patients treated by conventional radiation techniques, IG-IMRT was feasible for biliary tract tumors, warranting further investigation in prospective clinical trials.

Keywords: Gallbladder cancer, Biliary tract cancer, Cholangiocarcinoma, Image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT), Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)

Adenocarcinomas of the biliary tract, including tumors of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts, represent a comparatively rare class of neoplasms [1]. These tumors are often diagnosed in an already advanced stage, precluding definitive and potentially curative surgical extirpation [2]. Consequently, several series have explored the utility of pre- and post-operative radiotherapy as an adjunct to surgical intervention [3,4]. However, owing to the numerical paucity of cases, definitive large-scale prospective radiotherapy series are logistically impractical, and the role of radiotherapy remains controversial [5–8]. Extant data typically encompass a long time frame in order to accrue sufficient numbers, and often exhibit heterogeneous or outdated radiotherapy techniques [9–11].

In the last decade, the technical development of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has provided capability to deliver markedly more conformal radiation dose to tumor target volumes.

While data regarding the feasibility of clinically integrating the concepts of IMRT and image-guidance for treatment of biliary and pancreatic cancers have been published [12,13] it remains unclear if a benefit in clinical outcomes can be derived from these advanced radiotherapy delivery techniques.

The present hypothesis generating study aims to evaluate clinical outcomes in a series of patients with biliary tract adenocarcinomas treated with IG-IMRT by comparison with a cohort of patients treated with conventional radiation therapy (CRT).

Methods and materials

This study was performed under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio as a retrospective chart review and analysis.

Between July 1995 and November 2005, a total of 48 patients with pathologically diagnosed primary adenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts and/or gallbladder were treated in the Department of Radiation Oncology at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX and the Cancer Therapy & Research Center, San Antonio, TX. Patients were required to have formal pathological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder or biliary duct and/or cholangiocarcinoma. Tumors of the ampulla of Vater, Klatskin’s tumor, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas were excluded. Of 48 patients, 24 were treated with ultrasound-based image-guided targeting during daily patient set-up for serial tomotherapeutic IMRT, while the remaining 24 patients received radiation therapy using conventional planning and delivery techniques. Demographic data, tumor characteristics, and AJCC staging are presented in Table 1. All patients (100%) received pre-therapy diagnostic CT-imaging. Of these, 31 (65%) had notation of a diagnostic CT with precontrast/arterial/portal phase/delayed phase acquisition (“3-phase CT). Sixteen patients (33%) had recorded endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Thirty-three (69%) had magnetic resonance imaging, with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography recorded for 15 cases (31%). 18FDG-PET was noted in seven patients (15%).

Table 1.

Demographic and treatment variables by cohort (%).

| All Pts (n = 48) | Bile duct (n = 19) | Gallbladder (n = 29) | IG-IMRT (n = 24) | CRT (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (range) | 65 (39–86) | 64 (39–86) | 65 (43–85) | 65 (39–86) | 63 (43–85) |

| Age > 65 years | 24 (50) | 9 (47) | 15 (52) | 12 (50) | 12 (50) |

| Age < 65 years | 24 (50) | 10 (53) | 14 (48) | 12 (50) | 12 (50) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (%) | 28 (58) | 6 (32) | 22 (76) | 10 (58) | 18 (75) |

| Male (%) | 20 (42) | 13 (68) | 7 (24) | 14 (42) | 6 (25) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White (%) | 20 (42) | 9 (47) | 11 (38) | 11 (46) | 9 (38) |

| Hispanic (%) | 27 (58) | 10 (53) | 18 (62) | 13 (54) | 15 (62) |

| AJCC stage | |||||

| IA (%) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| IB (%) | 16 (33) | 3 (16) | 13 (45) | 8 (33) | 8 (33) |

| IIA (%) | 22 (45) | 12 (63) | 10 (34) | 9 (38) | 13 (54) |

| IIB (%) | 4 (8) | 2 (11) | 2 (7) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) |

| III (%) | 4 (8) | 2 (11) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) |

| IV (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Pathology | |||||

| Bile duct primary | 19 (40) | - | - | 11 (46) | 8 (33) |

| Gallbladder primary | 29 (60) | - | - | 13 (54) | 16 (67) |

| Surgery | |||||

| Unresectable | 14 (29) | 9 (47) | 5 (17) | 5 (21) | 9 (38) |

| Resection performed | 34 (71) | 10 (53) | 24 (83) | 19 (79) | 15 (62) |

| Cholecystectomy | 26 (54) | 4 (22) | 22 (76) | 12 (50) | 14 (58) |

| Common bile duct resection | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | - | - | 1 (4) |

| Partial resection | 2 (4) | 2 (10) | - | 2 (9) | - |

| Aborted partial resection | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | - | 1 (4) | - |

| Whipple | 4 (8) | 2 (10) | 2 (7) | 4 (16) | - |

| Microscopically negative margin (R0) | 9 (19) | 2 (11) | 7 (24) | 4 (16) | 5 (21) |

| Microscopically positive margin (R1) | 18 (38) | 5 (26) | 13 (45) | 11 (46) | 7 (30) |

| Grossly positive margin (R2) | 3 (7) | 2 (11) | 1 (3) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

| Margin status not specified | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (10) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| None | 17 (35) | 6 (31) | 11 (38) | 10 (40) | 7 (30) |

| Concurrent chemoradiation | 31 (65) | 13 (69) | 18 (62) | 15 (60) | 16 (70) |

| 5-Flurouracil (5FU) | 22 (46) | 8 (61) | 14 (77) | 8 (32) | 14 (61) |

| Capecitabine | 9 (19) | 5 (39) | 4 (23) | 7 (28) | 2 (9) |

Abbreviations: IG-IMRT = image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy, CRT = conventional radiotherapy;

statistically significant by Fisher's exact test.

The majority of patients were referred for radiotherapy after surgical extirpation. Surgical intervention rate by treatment modality and primary site is summarized in Table 1. Of 34 patients who received a surgical intervention, margin status was formally reported in extant records in 30 cases; of these 9 were recorded as having no marginal involvement microscopically (R0), 18 were denoted as exhibiting positive microscopic involvement at resection margins (R1), and 3 were noted with grossly positive margins (R2). Margin status by primary malignancy and therapy cohort is tabulated in Table 1.

In addition to radiotherapy, the majority of patients received concurrent fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Concurrent fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy rates and regimens by treatment technique and disease site are tabulated in Table 1. Gemcitabine (three patients), irinotecan (one patient), and cisplatin (two patients) were also recorded as delivered during/immediately after radiotherapy. No clear pattern of chemotherapy or standardized dosing regimen was evidenced from chart data available for review.

IG-IMRT treatments were planned and delivered using previously reported methods [13,14]. IMRT treatment plans were generated based on contrast-enhanced slow helical computed tomography (CT) scans acquired during relaxed free breathing. Before 2005, all patients were simulated on a PQ 5000 CT-simulator (Marconi Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH); after 2004, patients ( = 4) were imaged on a GE Lightspeed RT scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). Patients simulated using the PQ 5000 were imaged using a slice of thickness 3.0 mm; all four patients simulated after 2004 were imaged using 4DCT with respiratory gating with 1.2 mm slice reconstruction. Before 4DCT availability, additional inhale/exhale CT scans were acquired in selected patients. Patients were simulated using a standardized simulation protocol, supine on a wingboard with arms above the head using custom vacuum bag immobilization (Medical Intelligence GmbH, Schwabmünchen, Germany). All simulations were performed using a timed bolus of non-ionic intravenous contrast media, with early arterial/portal venous contrast phase, and a secondary venous contrast phase acquisition. DICOM data were transferred to an inverse IMRT treatment planning station (Corvus 3.0/4.0/5.0, Nomos Corp., Cranberry Township, PA). Gross target volumes (GTVs) and clinical target volumes (CTVs) according to ICRU 62 definitions [15] were delineated on a slice-by-slice basis. If available, diagnostic MR data were incorporated into the target delineation process, either as a reference image set or via MRI-CT fusion. Organs-at-risk (OAR) delineated included the spinal cord, kidneys, and healthy liver. Simultaneously, reference vascular structures and/or operative clips adjacent to the CTV were identified, and their spatial geometry relative to target volumes was defined by volumetric delineation. Vascular guidance structures were individually selected and delineated in each patient depending upon individual anatomy and tumor location, with ease of ultrasound visualization as a priority. A planning tumor volume (PTV) was created by volumetric expansion of the CTV by 10–15 mm. When a planned boost was delivered to a reduced target volume (CTVboost), a PTVboost was created by safety margin expansion of 6–10 mm. Dose–volume histograms were utilized to evaluate plans. Prescribed doses to the initial PTV ranged from 46 to 56 Gy (median 50 Gy) in daily doses of 1.8–2 Gy. Prescription dose to the PTVboost was 3.6–18 Gy (median 14 Gy) in conventional fractionation. A priority target goal for PTV was set so as to allow PTV voxels to receive no less than 95% and no more than 117% of prescription dose. Spinal cord was given a 30 Gy structure goal, with a hard constraint set so as not to exceed 42 Gy to any voxel. Relative constraints included left kidneys constrained to a D100 of <20 Gy and D66 <18 Gy; right kidneys were specified to achieve D100 <30 Gy, with D66 <20 Gy. Total mean liver dose was specified to <22 Gy, and liver V20 kept under 33%. Treatments were delivered using a 6 MV linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) with 400 or 600 MU/min delivery capability using the dedicated serial tomotherapy MIMiC binary multi-leaf collimator (Nomos Corp., Cranberry Township, PA).

The concept and procedure of ultrasound-based image-guidance with the BAT system (North American Scientific, Chatsworth, CA) have been previously reported [12,16–19] and specific technical details regarding implementation for gallbladder tumors have been detailed in a previous study [13]. The system [14], originally developed for prostate targeting, was implemented to allow for visualization of CT-derived volumes for adjacent organs (liver and right kidney), named vascular guidance volumes (proper hepatic artery, main hepatic vein, portal vein–splenic vein confluence, portal vein, superior mesenteric and celiac arteries, and aorta) and fiducial markers (surgical clips). Briefly, patients were placed supine upon the treatment couch and skin marks aligned to room lasers. Transabdominal US images were acquired in axial and sagittal planes with CT-delineated target and guidance structure volumes superimposed upon real-time ultrasound images. After virtual shifts were estimated by the user to match CT planning structures to ultrasound anatomy, the patient’s three-dimensional position relative to primary room-axes was corrected, followed by a confirmation sonographic scan. Treatment fraction delivery then followed immediately thereafter.

All patients receiving conventional radiotherapy were CT simulated before radiation delivery, with 23/24 receiving three-dimensional treatment planning. All patients were simulated on a PQ 5000 CT-simulator (Marconi Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH) using a slice of thickness 3.0 mm, with arterial phase intravenous contrast. Immobilization was achieved using AlphaCradle (Smithers Medical Products, Inc., North Canton, OH) or Blue Bag immobilization (Medical Intelligence GmbH, Schwabmünchen, Germany). A variety of multi-beam techniques were used to treat the tumor bed to a median total prescription dose of 48 Gy. Typically, patients were treated to 46–50.4 Gy using two-field (anterior–posterior/posterior–anterior) or four-field (anterior–posterior/posterior–anterior with lateral beams). Thirteen patients received a boost of 4–10 Gy to a reduced treatment volume, using a combination of anterior–posterior, posterior–anterior, lateral, and oblique fields. Weekly portal imaging was utilized for alignment of bony anatomy. Patients were prescribed 1.8–2 Gy per fraction daily, 5 days a week using 6 MV photons.

Demographic data were collected regarding patient age, gender, ethnicity, histological classification, primary site, chemotherapy regimen, tumor staging, and surgical resection. Dosimetric parameters analyzed included total dose and number of fractions. Toxicity analysis involved recording weekly Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) acute toxicity scores, as well as number and duration of toxicity-related treatment interruptions. Patterns of failure were assessed by reviewing clinical follow-up charts, radiographic and pathology reports. Median time to local/distant progression was estimated using product-limit estimation of median survival. Survival data were collected and examined using the Kaplan–Meier method. Toxicity between groups was compared as a categorical variable using Chi-square proportional analysis with Fisher’s correction. Data analysis was performed using StatView and JMP v6 software (SAS Institute Cary, NC, USA). For this hypothesis generating dataset, a non-Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.05 threshold was used to assess for statistical significance.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics, by radiotherapy cohort and tumor type, are shown in Table 1.

Dose delivered to patients is detailed cumulatively and by cohort in Table 2. A statistically significant differential in mean delivered dose, 59 vs. 48 Gy, was observed between IG-IMRT and CRT cohorts, respectively (p = 0.0001). Cumulatively, the mean dose delivered to the IMRT cohort represented a 23% increase over the mean dose delivered to the CRT cohort.

Table 2.

Dosimetric parameters by cohort.

| Series | IG-IMRT | CRT | Bile duct | Gallbladder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total dose (Gy) | |||||

| Median (range) | 54 (30–70) | 59 (50–70) | 48 (30–56) | 54 (30–66) | 55 (41.4–70) |

| Mean (CI) | 53 (50–55) | 58.3 (56–60) | 47.5 (44–51) | 52 (48–57) | 54 (51–56) |

| Radiation fractions | |||||

| Median (range) | 28 (15–38) | 30 (27–38) | 26 (17–31) | 30 (17–35) | 38 (21–38) |

Toxicity data are compiled in Table 3. One patient failed to complete treatment, voluntarily withdrawing after receiving 27 Gy out of a planned 54 Gy total dose, with a maximum RTOG Grade 3 upper GI acute toxicity score (medication-refractory abdominal pain). Treatment interruptions were minimal for most patients, with the majority attributable to holidays and/or inclement weather. The most commonly reported GI toxicities requiring medication (≽RTOG Grade 2) were nausea requiring promethazine or ondansetron, and diarrhea requiring diphenoxylate or loperamide. The observed Grade 3 upper GI acute toxicities were nausea/vomiting requiring tube or parenteral support in one patient, and severe abdominal pain despite medication in the single patient withdrawing from therapy. There were no treatment-related deaths. No patients required hospital admission for symptoms related to treatment. Chi-square analysis with Fisher’s exact test was utilized to compare the ratio of patients experiencing RTOG Grade 2 or less vs. Grade 3 toxicity, and was not statistically significant (p = 0.067). However, a statistically significant (p = 0.0465) difference was noted in proportion of Grade 2 or higher toxicity between the CRT group and the IMRT cohorts (Table 3). No statistically significant proportional difference between IG-IMRT and CRT cohorts could be ascertained for Lower GI, Upper GI, or Maximum experienced RTOG scores could be ascertained (all p ≥ 0.08) when assessing toxicity as an ordinal variable.

Table 3.

RTOG acute toxicity score by cohort (%).

| Acute toxicity | All Pts | IG-IMRT | CRT | Bile duct | Gallbladder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Upper GI (%) | |||||

| 0 | 15 (31) | 7 (29) | 8 (33) | 7 (37) | 8 (28) |

| 1 | 11 (23) | 4 (17) | 7 (29) | 3 (16) | 8 (28) |

| 2 | 20 (42) | 11 (46) | 9 (38) | 8 (42) | 12 (41) |

| 3 | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | - | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Lower GI (%) | |||||

| 0 | 30 (63) | 10 (42) | 20 (83) | 18 (62) | 12 (63) |

| 1 | 12 (25) | 8 (33) | 4 (17) | 7 (24) | 5 (26) |

| 2 | 6 (12) | 6 (25) | 0 (0) | 4 (14) | 2 (10) |

| Maximum (%) | |||||

| 0 | 13 (27) | 5 (21) | 8 (33) | 6 (31) | 7 (24) |

| 1 | 11 (23) | 4 (17) | 7 (29) | 4 (21) | 7 (24) |

| 2 | 22 (46) | 13 (54) | 9 (38) | 8 (42) | 14 (48) |

| 3 | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

A total of 37 patients (77%) had evidence in the medical record specifying the status and the location of disease progression. The number, percentage, and median time to local or distant failure, as well as the first disease progression, are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Patterns of failure (n = 37).

| N Events | N Censored | Median (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Local failure | |||

| CRT | 6 | 11 | 12.0a |

| IG-IMRT | 9 | 11 | 9.6 |

| Gallbladder | 7 | 13 | 7.8a |

| Bile duct | 8 | 9 | 7.5 |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| CRT | 7 | 10 | 21.0 |

| IG-IMRT | 6 | 14 | 26.4 |

| Gallbladder | 4 | 16 | 22.0a |

| Bile duct | 9 | 8 | 17.7 |

| Recorded disease progression (any) | |||

| CRT | 12 | 5 | 5.2 |

| IG-IMRT | 13 | 7 | 7.5 |

| Gallbladder | 11 | 9 | 6.5 |

| Bile duct | 14 | 3 | 7.8 |

Biased estimate on product-limit analysis.

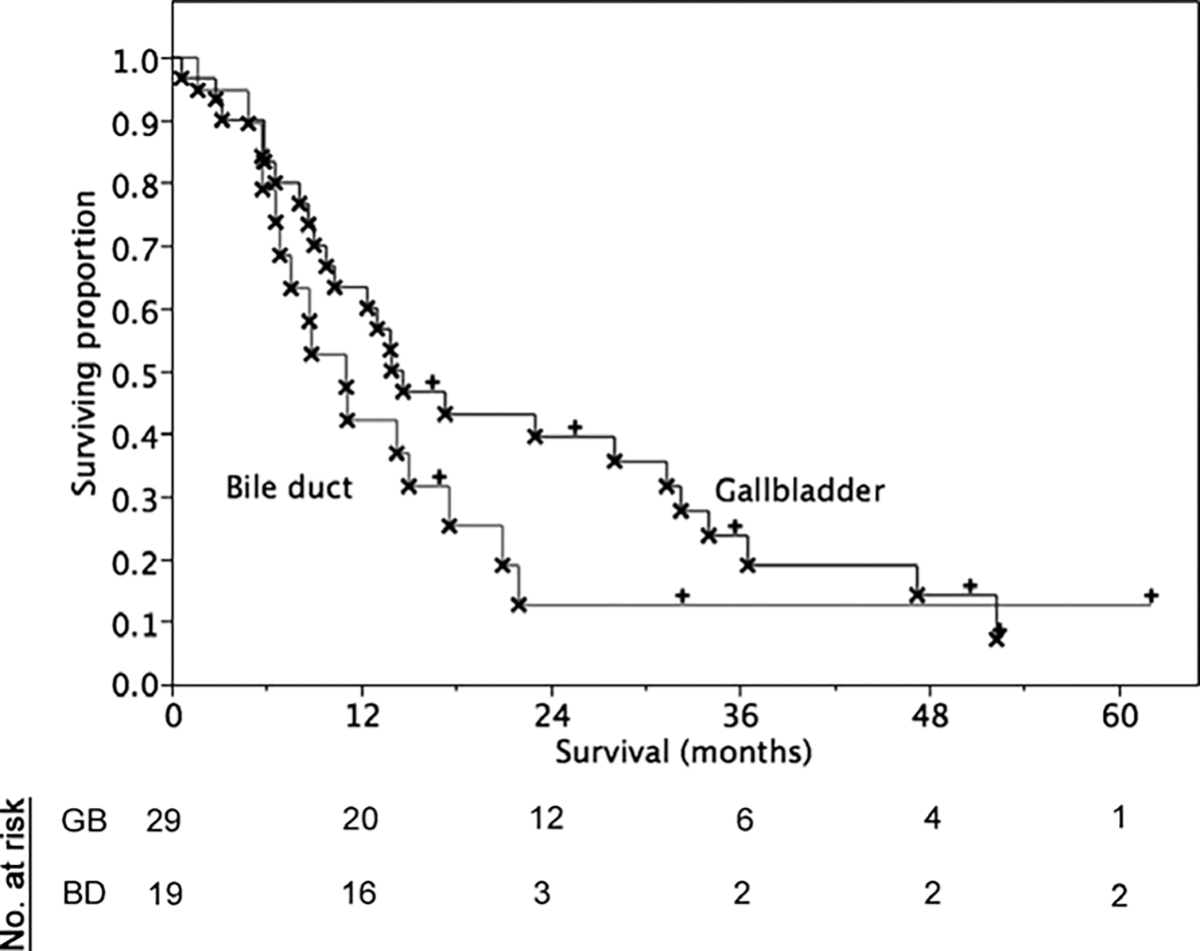

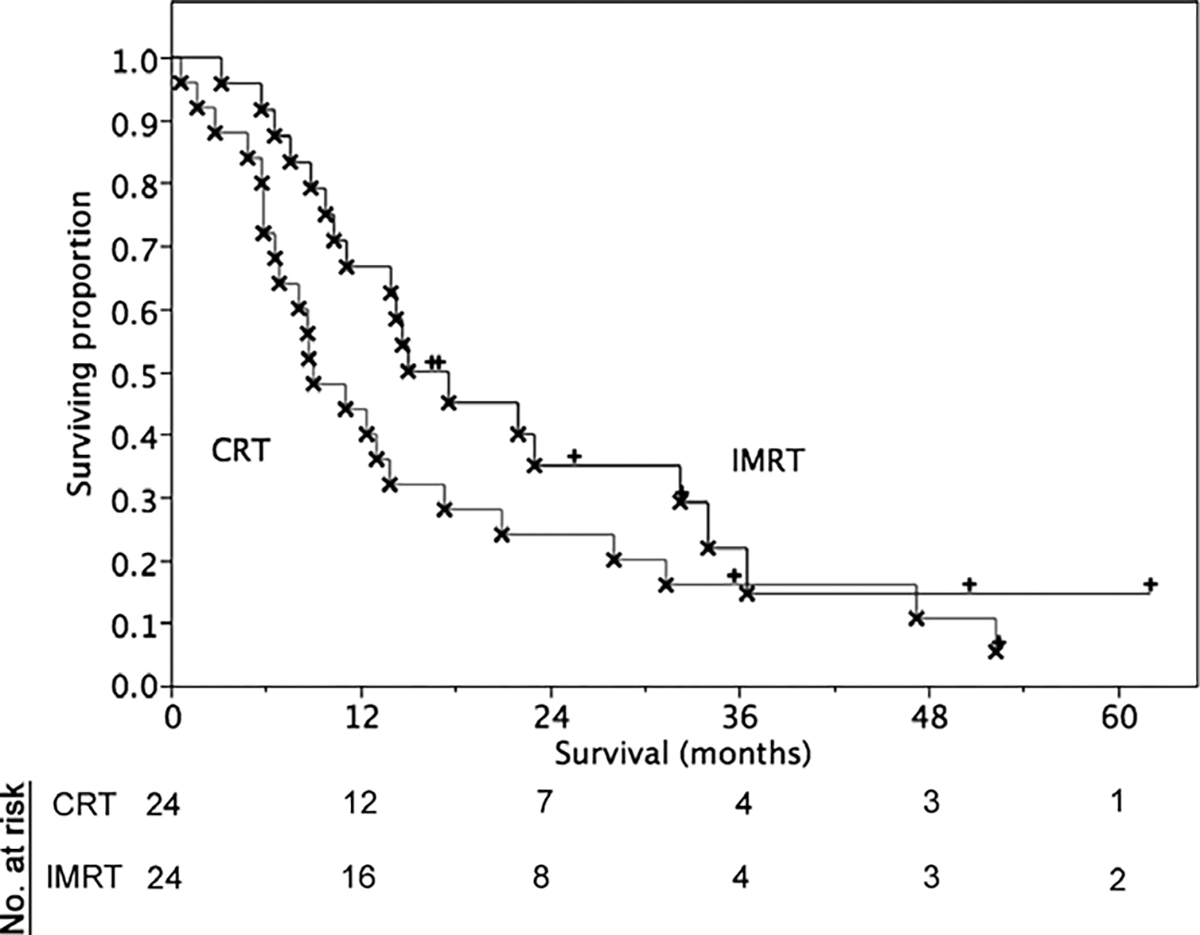

At last contact, 8/48 patients were alive (16%), with a median follow-up of 34 months (range 16.5–62) for those living at last contact. Overall survival for the entire series (n = 48) was 13.9 months (95% CI 9.0–17.6 months). Survival analysis by radiotherapy cohort/primary site is summarized in Table 5 and Figs. 1 and 2. Those patients who were receiving concomitant chemoradiation had a median survival of 14.7 months (CI 9.0–23.0) compared to a median survival of 11.1 (CI 4.9–17.3) months for those who were not receiving concurrent chemotherapy. Patients receiving radiation therapy as an adjuvant to surgery demonstrated a median survival of 17.3 months (CI 13.0–31.4), while those with unresectable disease at presentation showed a median survival of 6.6 months (CI 3.2–8.9). R0 resection status patients had a median survival of 16.9 months (CI 9.8–24.2 months), while positive surgical margin patients evinced a median 14.7 month (CI 8.22–22.1) overall survival. AJCC Stage I–II patients had a numerically greater survival at a median of 15.0 months (10.3–28.1) in contrast to 8.9 months (CI 5.8–21.0) for Stages III–IV.

Table 5.

Median survival outcomes for patients completing prescription (confidence intervals in parentheses); cohort numbers given in Table 1.

| Cohort | Series | Bile duct | Gallbladder |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All patients (series) | 13.9 (9.0–17.6) | 11.1 (6.6–17.6) | 14.7 (9.0–31.2) |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| IMRT | 17.6 (10.3–32.3) | 15.0 (7.6–22.3) | 23.0 (9.8–36.5) |

| CRT | 9.0 (6.6–17.3) | 6.9 (1.7–11.2) | 13.3 (5.9–31.4) |

| Surgery | |||

| Unresected | 6.6 (3.2–8.9 | 7.6 (1.7–11.1) | 3.2 (0.6-§) |

| Resectable | 17.3 (13.0–31.4) | 17.6 (5.7-§) | 17.2 (12.4–34.1) |

| R0 | 16.9 (9.8–24.2) | § | 17.3 (9.0-§) |

| R1/R2 | 14.7 (8.22–22.1) | 15.0 (5.7–21.0) | 14.7 (8.1–36.5) |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| None | 11.1 (4.9–17.3) | 8.7 (4.9–14.2) | 17.3 (6.5–36.5) |

| Chemoradiation | 14.7 (9.0–23.0) | 17.8 (6.6-§) | 13.0 (9.8–31.7) |

- could not be calculated.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival by primary site.

Fig. 2.

Overall survival by treatment cohort.

Discussion

Both gallbladder adenocarcinomas and cholangiocarcinomas are numerically rare neoplasms [20,21]. Owing, in part to the rarity of these lesions, the role of radiotherapy in the treatment of these biliary tract cancers remains controversial. Though surgical extirpation remains the cornerstone of curative intent therapy, a minority of patients present with resectable disease [22]. Current multimodality management appears to exhibit potential for improvement in clinical outcomes in selected patient groups [23,24], most notably in cases amenable to resection [25,26]. Radiotherapy has also demonstrated potential for benefit in patients with unresectable disease [27]. Nonetheless, the optimal implementation of radiotherapy techniques within multimodality protocols has yet to be ascertained, a matter of no small difficulty owing to the numerical paucity of radiotherapy series [9].

Previous reports have documented the implementation of ultrasound-based image guidance for abdominal malignancies, in an effort to increase capacity for daily target positional verification, and afford consequent PTV reductions [16–19,28]. Verification studies have demonstrated the validity of positional shifts for neoplastic lesions in visceral organs, as well as the capacity to deliver reduced dose to OARs in both pancreatic and biliary tract tumors [13,14]. The implemented IGRT system accounts for inter-fraction set-up error. However, in future series, it is critical to incorporate intra-fractional motion control, such as respiratory gating, active breathing control, dynamic motion correction, or other methods [29,30].

Data regarding IMRT for biliary tract lesions specifically have remained limited to date. Milano et al. report three patients with cholangiocarcinoma exhibiting a median survival of 9.3 months following IMRT treatment with doses ranging from 45 to 59.4 Gy [31]. Extant conventional radiotherapy series have implemented a range of prescription doses to target volumes for biliary tract tumors (Table 6), with survival parameters comparable to the current series. For gallbladder cancers, typical conventional radiotherapy doses have been between 50 and 58 Gy [25,32–34]. Cholangiocarcinoma series have evidenced similar dose prescriptions (Table 6). Compared with published radiotherapy series in the literature, the present IG-IMRT cohort of patients received modestly higher doses (median prescribed dose 59 Gy), with a maximum dose of 70 Gy, consistent with the higher end of previously reported treatment prescriptions delivered without IG-IMRT [25,33–37].

Table 6.

Selected external beam biliary radiotherapy cohorts from recent literature.

| Study first author | n | Median dose (Gy) | Mean dose (Gy) | Range (Gy) | Median survival (months) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | ||||||

| Crane | 52 | - | - | 30–85 | 10 | All patients had unresectable disease |

| Ben-David | 81 | 30–66 | - | 23–83.6 | 14.7 | Series showed no differential between R1 and R2 disease in adjuvant setting |

| Stein | 16 | - | 53 | 40–74 | 24.5 | All patients post resection |

| Nelson | 45 | 50.4 | - | 34 | All patients with adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemoradiation | |

| Current study (cholangio only) | 19 | 54 | 52 | 30–66 | 11.1 | |

| Gallbladder | ||||||

| Czito | 22 | 45 | - | 39.6–60 | 22.8 | All patients received chemoradiation, primarily 5FU-based |

| Kresl | 21 | 54 | - | 50.5–60.8 | 31.2 | All patients received concomitant 5FU |

| Current study (gallbladder only) | 29 | 55 | 54 | 41.4–70 | 14.7 | |

Surgical resectability in previous series has represented a potent harbinger of outcome in biliary tract neoplasms [35,36]. Surgical extirpation remains the cornerstone of therapy, as demonstrated by the increase in survival for surgically resectable patients (median 17.3 months vs. 6.6 months for unresected disease). This study, like most retrospective biliary tract series involving chemoradiation, is hampered by the lack of uniform chemoradiation protocol. The predominant pattern in the present study involved fluorouracil-based regimens, either as an intravenous infusion or as an orally delivered pro-drug (Table 1). The use of intravenous 5-FU chemoradiotherapy for biliary tract cancers has been reported repeatedly [26,38,39]; however, while many series have explored single-or multi-agent protocols containing capecitabine for biliary tract lesions, few descriptions of capecitabine chemoradiotherapy have been reported.

While excessive generalization of observed findings would be specious, this series represents the largest documented series of biliary tract cancers treated with image-guided IMRT, as well as one of the larger series of gallbladder adenocarcinomas treated with modern radiotherapy techniques. Nonetheless, inherent study limitations must be noted. This study is numerically limited and, though the total number of cases approximates previous series, draws from a single institutional experience [9,25,26,32,33]. As with any retrospective series, specific treatment parameters (initial MRCP/ERCP evaluation, chemotherapy regimen, degree of hepatic extension, etc.) were difficult to characterize fully from chart review, and thus could not be accounted for with optimum reliability. The high proportion of patients with advanced/metastatic disease at presentation in our series also hampers generalization of this dataset. The presentation of dose data in this series is performed primarily as a mechanism of generating testable hypotheses for future prospective series, and should not be implemented into treatment planning approaches without substantive verification. We have previously presented data regarding dose parameters using virtual plan comparison [13], and we hope to utilize these findings as a benchmark in future prospective series.

This report suggests that moderate dose escalation via conformal radiotherapy techniques is technically and clinically feasible. The present series alludes to the capability of IG-IMRT to realize modest dose escalation in the absence of substantial dose-limiting toxicity [14]. It is imperative that the radiotherapy community definitively determine whether technical improvements in dose delivery, such as IG-IMRT, are an avenue for greater clinical efficacy for biliary tract cancers [40].

Acknowledgements

C.D.F. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, “Multidisciplinary Training Program in Human Imaging” (5T32EB000817–04); this funder had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Preliminary aspects of these data were presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology, November 5–9, 2006. Special thanks are given to Bill Salter, PhD, Adrian Wong, MD, and Garrett Starling, MD for their assistance in data collection.

References

- [1].Baillie J Tumors of the gallbladder and bile ducts. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;29:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg 2000;232:557–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fields JN, Emami B. Carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary system – results of primary and adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1987;13:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hishikawa Y, Tanaka S, Miura T. Radiotherapy of carcinoma of the gallbladder. Radiat Med 1983;1:326–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR Jr, Ravdin PM. Prediction model for estimating the survival benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy for gallbladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thomas CR, Fuller CD. Biliary tract and gallbladder cancer: diagnosis & therapy. New York, NY: Demos; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Macdonald OK, Crane CH. Palliative and postoperative radiotherapy in biliary tract cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2002;11:941–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Serafini FM, Sachs D, Bloomston M, et al. Location, not staging, of cholangiocarcinoma determines the role for adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. Am Surg 2001;67:839–43 [discussion 843–834]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Houry S, Barrier A, Huguier M. Irradiation therapy for gallbladder carcinoma: recent advances. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2001;8:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Houry S, Schlienger M, Huguier M, Lacaine F, Penne F, Laugier A. Gallbladder carcinoma: role of radiation therapy. Br J Surg 1989;76:448–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Houry S, Haccart V, Huguier M, Schlienger M. Gallbladder cancer: role of radiation therapy. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:1578–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fuss M, Wong A, Fuller CD, Salter BJ, Fuss C, Thomas CR. Image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2007;1:2–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fuller CD, Thomas CR Jr, Wong A, et al. Image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy for gallbladder carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 2006;81:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fuss M, Salter BJ, Cavanaugh SX, et al. Daily ultrasound-based image-guided targeting for radiotherapy of upper abdominal malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:1245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon beam therapy. Bethesda, MD: International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lattanzi J, McNeeley S, Hanlon A, Schultheiss TE, Hanks GE. Ultrasound-based stereotactic guidance of precision conformal external beam radiation therapy in clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology 2000;55:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fuss M, Cavanaugh SX, Fuss C, Cheek DA, Salter BJ. Daily stereotactic ultrasound prostate targeting: inter-user variability. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2003;2:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chandra A, Dong L, Huang E, et al. Experience of ultrasound-based daily prostate localization. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;56:436–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mohan DS, Kupelian PA, Willoughby TR. Short-course intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer with daily transabdominal ultrasound localization of the prostate gland. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Gallbladder cancer. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2006;9:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Patel T. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;3:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Leone N, De Paolis P, Garino M, et al. Surgery for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Our experience. Panminerva Med 2002;44:227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morganti AG, Trodella L, Valentini V, et al. Combined modality treatment in unresectable extrahepatic biliary carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:913–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sasson AR, Hoffman JP, Ross E, et al. Trimodality therapy for advanced gallbladder cancer. Am Surg 2001;67:277–83 [discussion 284]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kresl JJ, Schild SE, Henning GT, et al. Adjuvant external beam radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy in the management of gallbladder carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Czito BG, Hurwitz HI, Clough RW, et al. Adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy after resection of primary gallbladder carcinoma: a 23-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;62:1030–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Uno T, Itami J, Aruga M, Araki H, Tani M, Kobori O. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder: role of external beam radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced tumor. Strahlenther Onkol 1996;172:496–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lattanzi J, McNeeley S, Pinover W, et al. A comparison of daily CT localization to a daily ultrasound-based system in prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;43:719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].D’Souza WD, McAvoy TJ. An analysis of the treatment couch and control system dynamics for respiration-induced motion compensation. Med Phys 2006;33:4701–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gierga DP, Brewer J, Sharp GC, Betke M, Willett CG, Chen GT. The correlation between internal and external markers for abdominal tumors: implications for respiratory gating. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;61:1551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Milano MT, Chmura SJ, Garofalo MC, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in treatment of pancreatic and bile duct malignancies: toxicity and clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bosset JF, Mantion G, Gillet M, et al. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder. Adjuvant postoperative external irradiation. Cancer 1989;64:1843–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Czito B, Clough R, Tyler D, et al. Adjuvant external beam radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy following resection of primary gallbladder carcinoma: a 23-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;57:S385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Silk YN, Hü Douglass HO, Nava HR, Driscoll DL, Tartarian G. Carcinoma on the gallbladder: the Roswell park experience. Ann Surg 1989;210:751–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ben-David MA, Griffith KA, Abu-Isa E, et al. External-beam radiotherapy for localized extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66:772–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stein DE, Heron DE, Rosato EL, Anne PR, Topham AK. Positive microscopic margins alter outcome in lymph node-negative cholangiocarcinoma when resection is combined with adjuvant radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 2005;28:21–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Crane CH, Macdonald KO, Vauthey JN, et al. Limitations of conventional doses of chemoradiation for unresectable biliary cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;53:969–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Buskirk SJ, Gunderson LL, Adson MA, et al. Analysis of failure following curative irradiation of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1984;10:2013–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nelson JW, Ghafoori AP, Willett CG, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;73:148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ling CC, Yorke E, Fuks Z. From I.M.R.T. to IGRT: frontierland or neverland? Radiother Oncol 2006;78:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]