Summary

Small ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) recognize small surface patches on ubiquitin with weak affinity, and it remains a conundrum how specific cellular responses may be achieved. Npl4-type zinc-finger (NZF) domains are ∼30 amino acid, compact UBDs that can provide two ubiquitin-binding interfaces, imposing linkage specificity to explain signaling outcomes. We here comprehensively characterize the linkage preference of human NZF domains. TAB2 prefers Lys6 and Lys63 linkages phosphorylated on Ser65, explaining why TAB2 recognizes depolarized mitochondria. Surprisingly, most NZF domains do not display chain linkage preference, despite conserved, secondary interaction surfaces. This suggests that some NZF domains may specifically bind ubiquitinated substrates by simultaneously recognizing substrate and an attached ubiquitin. We show biochemically and structurally that the NZF1 domain of the E3 ligase HOIPbinds preferentially to site-specifically ubiquitinated forms of NEMO and optineurin. Thus, despite their small size, UBDs may impose signaling specificity via multivalent interactions with ubiquitinated substrates.

Keywords: ubiquitin binding domain, mono-ubiquitination, ubiquitin chain linkage, ubiquitin code, optineurin, autophagy, IKK

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Comprehensive diUb-binding profiles of human NZF Ub-binding domains

-

•

TAB2 NZF domain prefers phosphorylated K6 chains present at depolarized mitochondria

-

•

Conserved secondary binding sites exist in most NZF domains

-

•

HOIP NZF1 domain utilizes secondary sites to bind monoubiquitinated NEMO or optineurin

Small ubiquitin-binding domains such as NZF domains bind ubiquitin with low affinity. Michel et al. show that secondary conserved patches on NZF domains provide either linkage or substrate specificity by providing avid bidentate interactions. This way, the NZF1 domain of HOIP reads ubiquitination events on NEMO and optineurin.

Introduction

Protein ubiquitination is a pervasive post-translational modification that regulates virtually all aspects of cell biology,1 including, most prominently, the regulation of protein half-life, whereby ubiquitin (Ub) modifications lead to the degradation of proteins by the proteasome or the lysosome.2 In addition, Ub has many non-degradative roles; e.g., in cell signaling, protein trafficking, replication, transcription, and translation.3,4 This versatility is enabled by a plethora of distinct Ub signals, which include polyUb chains formed via at least eight distinct linkage types in homotypic (one linkage type) and heterotypic (multiple linkage types) architectures.1,3,4 However, the most abundant Ub modification in cells is monoubiquitination, whereby a protein is modified on a Lys residue with a single Ub moiety. Comparatively little is known about how monoubiquitination regulates protein fate and is recognized and utilized as a specific signal. Elegant studies on histones,5,6 DNA repair proteins,7,8 as well as developmental processes9 have provided insight into the various regulatory roles of monoubiquitination.10

Ubiquitination events are typically recognized by Ub receptors that contain Ub-binding domains (UBDs). More than 20 types of UBDs have been identified; most are small protein folds that recognize Ub, most commonly by binding to the I44 hydrophobic patch of Ub.1,11,12 Weak binding affinities of UBDs for monoubiquitin (monoUb) in the range of 50–500 μM are common. In some cases, UBDs are linkage specific and can differentiate polyubiquitin (polyUb) signals by binding selectively to particular Ub chain types.1,13 This is usually accompanied by a 10- to 100-fold increase in affinity for their preferred chain type and enables the various distinct outputs of different polyUb signals. For monoubiquitination, however, such a distinction cannot be made. Considering the number of ubiquitinated proteins and the usually low occupancy of ubiquitination sites, it is unclear how a UBD can selectively identify a monoubiquitinated substrate against the backdrop of other ubiquitinated substrates and a high (10–20 μM) concentration of unconjugated, “free” Ub to ensure specific biological signaling.14

A versatile family of UBDs are Npl4-like zinc finger (NZF) domains, which comprise ∼30 residues, including four structural Cys residues that coordinate one zinc ion. NZF domains are a subgroup of the RanBP2 ZnF (zinc-finger) fold and are characterized by a conserved Thr-(Phe/Tyr) motif (hereafter called TF motif), which, together with a third conserved typically hydrophobic residue within the second C-X-X-C motif, enables binding to the I44 patch of Ub.15 Numerous structures have shown that Ub binds to the NZF TF motif in an essentially identical orientation.16,17,18,19,20 Importantly, a subset of NZF domains specifically recognize select chain types. TAB2 (TAK1 binding protein 2) and TAB3, adaptors of the nuclear factor κ B (NF-κB)-regulating protein kinase TAK1 (TGFβ-activated kinase 1), bind K63-linked chains16,21,22; HOIL-1L (Heme-oxidised IRP2 ubiquitin ligase-1L) and Sharpin, components of the linear Ub chain assembly complex (LUBAC) prefer M1-linked chains17,23; and the deubiquitinase TRABID (TRAF-binding domain containing protein, also known as ZRANB1) uses three NZF domains to specifically bind K29 and K33 linkages.19,20 Complex structures have revealed that these NZF domains simultaneously interact with two Ub moieties: the distal Ub moiety is recognized by the TF motif, while the proximal Ub is bound distinctly on an adjacent NZF interaction surface; the relative orientation of this second Ub at its NZF binding patch determines linkage specificity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ub linkage preference analysis of human NZF domains

(A) Domain architecture of NZF-containing human proteins drawn to scale. NZF domains are shown in red, while related RanBP2-like zinc fingers are shown in orange.

(B) Sequence alignment of all 15 human NZF domains, with invariant residues shown in red and Ub binding residues in green.

(C) Schematic and nomenclature of diUb binding to an NZF domain. The distal Ub is attached to a Lys of the proximal Ub and binds to the TF motif of the NZF domain via its I44 patch (blue). DiUb used in binding assays contains an unattached C terminus on the proximal Ub (shaded area).

(D) Coomassie-stained gel of purified NZF domain constructs. See STAR Methods for construct boundaries.

(E) Visualization of affinities of NZF domains as measured by SPR (Figure S1). For each linkage, the log2 of the fold preference compared to the weakest binding linkage for each NZF is plotted. Asterisks indicate NZF domains that demonstrate linkage specificity.

Of 15 annotated NZF domains in humans, five have been comprehensively tested for linkage specificity against the available linkage types. We here analyze linkage preference profiles for unstudied human NZF domains against eight types of Ub linkages, confirming linkage preferences for previously studied members. We redefine TAB2/3 as containing an NZF domain with preference for proximally phosphorylated K6-linked Ub chains, which is explained by TAB2 NZF complex crystal structures. Surprisingly, we find that the majority of NZF domains lack chain preference, despite some members exhibiting (an) additional conserved surface(s) on the NZF domain that does not overlap with the Ub binding patch. We reveal that these secondary sites can directly bind ubiquitinated substrates, forming bidentate interactions with Ub and substrate near ubiquitination sites that provide signaling specificity. This is exemplified by the NZF1 domain of the LUBAC component HOIP (HOIL-1 interacting protein), and we show how HOIP NZF1 directly and specifically binds to NEMO (NF-κB essential modifier, also known as Inhibitor of κB kinase γ) ubiquitinated on K285. Interestingly, the NZF binding region of NEMO is conserved in optineurin (OPTN) but not other UBAN (Ub-binding domains in ABIN proteins and NEMO)-domain containing Ub receptors, and we show by further complex structures how OPTN ubiquitinated on K448 would be preferentially recognized by HOIP NZF1. Interestingly, an adjacent non-Ub-binding RanBP2 ZnF domain in HOIP displays conserved UBAN binding residues, suggesting how HOIP forms a clamp around UBAN dimers. Our data provide a conceptual solution to how small UBDs have evolved to directly bind their ubiquitinated targets, providing evidence that site-specific ubiquitination of key proteins could be of high functional importance.

Results

Linkage specificity analysis of human NZFs

The human proteome contains 11 proteins that contain a total of 15 NZF domains (Figures 1A and 1B). Several NZF domains have been studied functionally and/or biochemically and structurally, and several bind diubiquitin (diUb) through simultaneous interactions with distal and proximal Ub (Figure 1C). However, diUb binding specificity and affinities considering all eight chain types is only available for the three NZF domains of TRABID19,20 and the two NZF domains of HOIP.24 We cloned, expressed and purified the eight remaining NZF domains (Figure 1D), excluding TAB3 and YAF2 for their high identity with TAB2 (77% identity) and RYBP (90%), respectively (Figures S1A and S1B).

Purified NZF domains were tested for linkage specificity using a previously established surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based platform,19 in which the eight types of diUbs are immobilized on SPR chips, and equilibrium binding is measured over a range of NZF concentrations to derive KD values. This revealed a 50-fold specificity of TRABID NZF1 for K29 and K33 chains,19 while HOIP NZF1 and NZF2 did not show linkage preference (less than 5-fold difference in KD values24) (Figure 1E). Our data verify the preference of HOIL-1L and Sharpin NZF domains for M1-linked chains (Figures 1E, S1C, and S1D), which had previously been suggested from comparison of three chain types.17 HOIL-1L NZF bound M1-diUb with 4 μM affinity and displayed a 50-fold specificity, whereas Sharpin bound both M1- and K63-diUb with lower affinities of 55 μM and 170 μM, respectively. Strikingly, with exception of TAB2 (discussed below), the remaining unstudied NZF domains lacked linkage preference (Figures 1E, S1C, and S1D). Calpain15/CAPN15 contains two NZF domains that bound to all chain types in the range of 110–190 μM for NZF1 and 143–296 μM for NZF2. The NZF of ZRANB3 bound chains with affinities of 28–48 μM, whereas NPL4 NZF and RYBP NZF displayed higher KD values of 113–189 μM and 255–348 μM, respectively. Pull-down analyses were used to confirm key findings of our biophysical data (Figures S1E–S1G). Together, this provided a comprehensive landscape of human NZF domain diUb interactions (Figure 1E).

One potential caveat emerges in proteins that contain multiple NZF domains (namely TRABID, HOIP, and CAPN15), as such UBDs in combination may exhibit linkage preference by juxtaposing I44-binding patches, akin to tandem UIM motifs.25 For TRABID and HOIP, combinations of NZF domains have been characterized previously.19,24 The unstudied CAPN15 contains five RanBP2-zinc fingers at its N terminus, the first two of which have an NZF TF motif (Figure 1B). Pull-down experiments confirmed the lack of linkage specificity in a construct containing NZF-1, -2, and -3, and binding affinity could be mostly attributed to NZF1 (Figures S1D and S1F). This is reminiscent of our previous data on TRABID, where NZF1 provides linkage preference, and NZF2 and NZF3 boost specificity by providing avidity.19

TAB2 is cross specific for K6 and K63 linkages

TAB2 and TAB3 contain K63-specific NZF domains21 explained by their mechanism of two-sided Ub binding.16,18 In our expanded analysis, we found that TAB2 NZF also interacted with K6-linked diUb with similar affinity as compared to K63-linked chains (Figures 1E, S1C, and S1D). This was surprising but consistent with a mass spectrometry-based study in which a K6-diUb matrix enriched TAB2 and TAB3 from cell lysates.26

We confirmed the dual specificity of TAB2 by pull-down analysis (Figure S1G), and, in addition, also determined a 1.5-Å crystal structure of TAB2 NZF bound to K6-linked diUb (Figures 2A and S2A; Table 1). Interestingly, the crystallographic setting of this UBD in complex with a K6 chain is identical to a previously determined structure of TAB2 NZF bound to K63-linked diUb (PDB: 2wwz 16), and the content of the asymmetric unit is superimposable with low root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) (1.55 Å) (Figure 2B). The NZF domain binds the I44 patch of a distal Ub in the NZF-typical fashion via the TF motif, whereas the proximal Ub binds, also via its I44 patch, to a second site on the NZF. The linker between Ub molecules is disordered in the K6-diUb:TAB2 NZF complex but the C termini of the distal and the side chain of the proximal moiety are within easily reachable distance from each other. This structure readily explains the cross-specificity of TAB2: association with either chain type places two Ub moieties at hydrophobic binding sites, orienting them so that the C terminus of the distal Ub can link to either K63 or K6 of the proximal Ub (Figure 2B). Other Lys residues or M1 are spatially out of reach for the distal Ub C terminus. Hence, TAB2 exploits spatial restraints present in the K6 and K63 subset of polyUb chains. All Ub-binding residues are conserved in TAB3 NZF, which shares an identical diUb-binding mode.18 We note that Sato and colleagues recently reported a similar analysis of the TAB2 NZF binding mechanisms with K6-linked diUb.27

Figure 2.

TAB2 NZF prefers K6/K63 and proximally phosphorylated chains

(A) Crystal structure of TAB2 NZF (red) bound to K6 diUb (turquoise) with cartoon. The coordinated zinc atom is shown as a gray sphere, and I44 of Ub is shown in blue. The dashed line indicates the flexible C terminus of the distal Ub.

(B) Overlay of TAB2 bound to K6 diUb as in (A), with TAB2 bound to K63 diUb (PDB: 2wwz16).

(C) In vitro pull-down assay of GST-tagged TAB2 NZF against K6 diUb, in which either proximal, distal, or both Ub molecules were phosphorylated on S65.

(D) As in (A) but for TAB2 NZF (red) bound to K6 diUb, which carries a phospho-S65 modification (shown as sticks) on the proximal Ub.

(E) Electron density contoured at σ = 1.0 for phospho-Ser65 of the proximal Ub and its coordination by Arg72 of the distal Ub.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| TAB2 NZF: K6 diUb | TAB2 NZF: K6 diUb pS65prox | HOIP NZF1: NEMO UBAN-Ub | HOIP NZF1: OPTN UBAN | HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN:Met1 diUba | HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN:Met1 diUba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 9AVT | 9AVW | 9AZJ | 9B0B | 9B12 | 9B0Z |

| Data collection | ||||||

| Beamline | Diamond I24 | Diamond I24 | Diamond I04 | Diamond I24 | Diamond I03 | Diamond I03 |

| Space group | P 65 2 2 | P 65 2 2 | P 212121 | P 212121 | C 1 2 1 | C 1 2 1 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 90.3, 90.3, 86.3 | 89.7, 89.7, 86.1 | 66.8, 101.4, 144.1 | 49.8, 92.7, 149.9 | 110.4, 70.2, 193.9 | 247.6, 72.3, 56.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 102.3, 90 | 90, 95.1, 90 |

| Wavelength | 0.96861 | 0.96861 | 0.97950 | 0.96859 | 0.96863 | 0.96863 |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.11–1.50 (1.55–1.50) | 39.77–1.75 (1.81–1.75) | 50.72–3.32 (3.44–3.32) | 56.26–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 45.78–1.81 (1.88–1.81) | 43.46–2.41 (2.49–2.41) |

| Ellipsoidal resolution limit (Å) [direction] | 2.96 [a∗] 2.43 [b∗] 1.74 [c∗] |

2.39 [a∗] 2.88 [b∗] 2.87 [c∗] |

||||

| Rmerge | 0.036 (0.942) | 0.376 (0.979) | 0.098 (1.0) | 0.073 (0.744) | 0.052 (0.637) | 0.052 (0.703) |

| Rpim | 0.023 (0.615) | 0.089 (0.248) | 0.048 (0.475) | 0.047 (0.480) | 0.033 (0.404) | 0.034 (0.449) |

| I/σI | 20.0 (1.8) | 7.2 (2.3) | 9.1 (2.0) | 12.1 (1.9) | 13.6 (1.8) | 14.8 (1.6) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.636) | 0.990 (0.523) | 0.990 (0.688) | 0.999 (0.592) | 0.998 (0.608) | 0.998 (0.611) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.8) | 99.2 (96.8) | 99.7 (99.9) | 100.0 (100.0) | 92.5 (74.8) | 91.3 (70.3) |

| Multiplicity | 6.4 (6.2) | 18.6 (16.6) | 5.6 (5.8) | 6.4 (6.4) | 3.3 (3.4) | 3.3 (3.4) |

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 39.11–1.50 | 39.77–1.75 | 50.72–3.32 | 56.26–1.70 | 44.17–1.81 | 43.46–2.41 |

| No. reflections | 33792 | 21098 | 15026 | 77092 | 58347 | 25006 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 18.24/20.33 | 19.34/22.14 | 24.31/28.47 | 19.61/22.17 | 23.13/26.85 | 22.08/26.95 |

| Number of atoms | ||||||

| Protein | 1,411 | 1,408 | 4,256 | 3,248 | 5,801 | 4,578 |

| Ligand/ion | 29 | 31 | 2 | 110 | 101 | 2 |

| Water | 133 | 121 | 0 | 283 | 187 | 45 |

| B-factors | ||||||

| Wilson B | 23.0 | 16.6 | 122.1 | 21.6 | 29.7 | 59.0 |

| Protein | 33.7 | 26.0 | 167.3 | 34.7 | 60.9 | 72.1 |

| Ligand/ion | 60.4 | 70.7 | 257.0 | 67.1 | 69.1 | 70.5 |

| Water | 42.8 | 36.4 | – | 47.0 | 42.7 | 55.9 |

| RMSDs | ||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.35 | 0.88 | 0.44 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 0.81 |

| Ramachandran statistics (favored/allowed/outliers) | 99.4/0.6/0 | 98.8/1.2/0 | 98.1/1.7/0.2 | 99.5/0.5/0 | 98.4/1.6/0 | 97.5/2.5/0 |

Numbers in brackets are for the highest-resolution bin.

Statistics are reported for ellipsoidally scaled data.

Ub phosphorylation enhances TAB2 interactions

Intriguingly, our crystal structure showed clear electron density corresponding to a sulfate group, immediately adjacent to the S65 side chain to the proximal Ub moiety, close to the distal Ub, and with potential to affect diUb conformation and interactions (Figure S2B). Ub is known to undergo phosphorylation at S65 after activation of the Ub kinase PINK1 upon mitochondrial damage,28,29,30,31,32 which is physiologically important for PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy33 and pathophysiologically relevant as PINK1 and Parkin mutations lead to early-onset Parkinson’s disease.34 To test whether the observed mimicry of phospho-S65 Ub in the crystal structures of TAB2 was functionally relevant, we performed studies with phosphorylated K6-linked diUb, which emerges as a product of Parkin during mitophagy initiation.35,36 Designer chains were generated in which either distal, proximal, or both Ub molecules were S65 phosphorylated, and their binding was tested by pull-down analysis. As suggested by the structure, all K6-diUb variants were able to bind TAB2 NZF, and binding was enhanced by proximal, but not distal, Ub phosphorylation (Figure 2C).

Next, we determined a 1.8-Å crystal structure of TAB2 NZF bound to proximally S65-phosphorylated K6-diUb (Figures 2D and S2C; Table 1). Identical positioning of distal and proximal Ub on the NZF domain confirmed that phosphorylation did not interfere with TAB2 binding. Importantly, phospho-S65 is positioned so that it is directly contacted by R72 of the distal Ub moiety, creating a second connection between Ub moieties and indeed the only one that is structurally resolved (residues 73–76 from the distal Ub lack electron density) (Figures 2D and 2E). Hence, it appears that Ub S65 phosphorylation is not only enabled in the context of TAB2 binding but even positively contributes to the conformation of diUb stabilized by UBD interaction. These findings likely extend to K63-linked chains, in which proximal phosphoUb would be forming identical interactions (Figure S2D). Moreover, while K6-linked chains are preferably phosphorylated at the distal Ub, K63-linkages are more uniformly phosphorylated at both Ub moieties, owing to its more open conformation.36

The observed cross-specificity of TAB2 further explains previous cell-biological data showing that fluorescent TAB2 NZF labels depolarized mitochondria exceedingly well.37 This had been explained by deposition of K63-linked chains on mitochondria upon PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy initiation. In the light of our specificity data and prior proteomic evidence of phosphorylated Ub and K6 chains on depolarized mitochondria,31,38 we now propose that it is phosphorylated K6 and K63 linkages on mitochondria that account for localizing TAB2 NZF at depolarized mitochondria.

Striking conservation in NZF domains lacking chain preference

Together with published work, our data molecularly explains all occurrences of linkage (cross)specificity in human NZF domains. With our insight into the mechanism of diUb binding, we wondered whether we could have predicted binding modes by analyzing sequence conservation in an evolutionary context. Characterization of sequence conservation between species individually for the 15 human NZF domains uncovered varying degrees of conservation within the NZF domains (Figure 3A) and, in some cases, in adjacent regions (Figure S3A). Invariant residues defining NZF domains include 4 Cys residues that bind a Zn ion, two structural residues (Trp preceding the first Cys and Asn between the second and third Cys), and the mentioned TF motif that binds Ub (Figure 3A). Sequence annotation was complemented with structural characterization using available experimental and AlphaFold39,40 models (Figure 3B). The latter provided high-quality models for NZF domains that were for the most part indistinguishable from experimental structures and further informed on likely secondary and tertiary structure elements that may lie in the vicinity of the NZF domains in multidomain proteins.

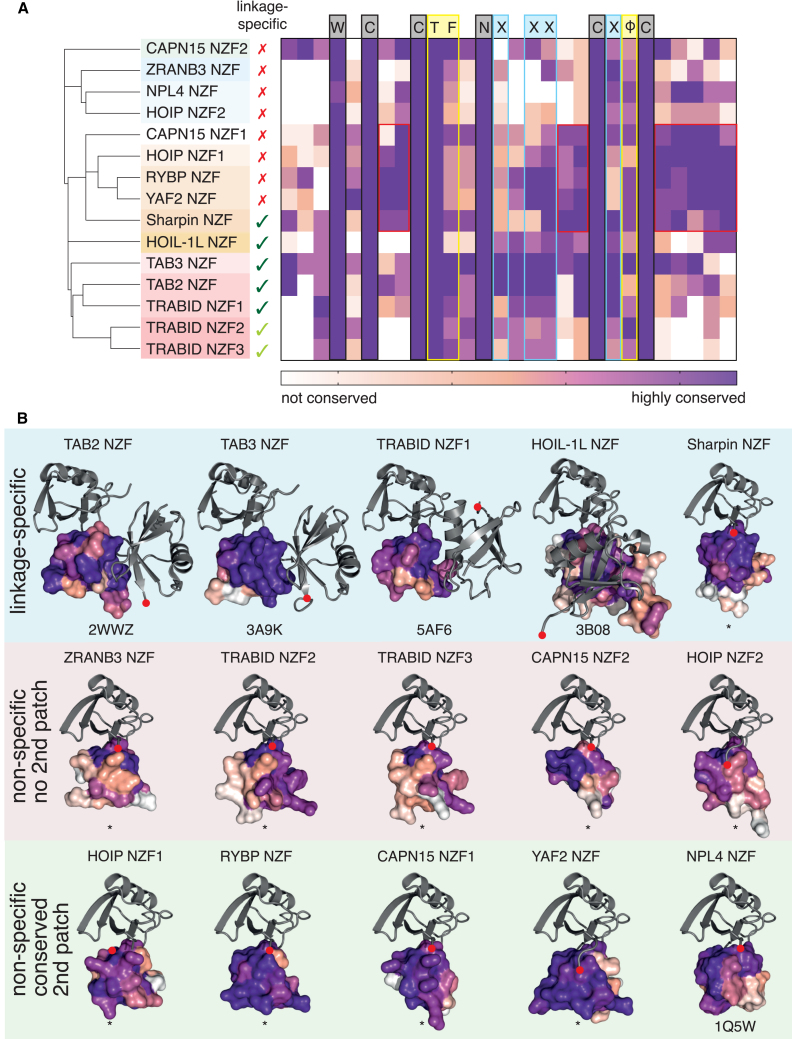

Figure 3.

Sequence conservation analysis of NZF domains

(A) Hierarchically clustered heatmap of NZF sequence conservation within NZF domains. Structural residues are indicated at the top in gray, Ub-binding residues in yellow, and residues that comprise a proximal Ub-binding site in blue. A cluster of additional stretches of high conservation is boxed in red.

(B) Sequence conservation of NZF domains mapped onto NZF:Ub models (∗) or deposited structures. The C terminus of Ub (gray) is shown as a red dot. Three categories are indicated by different colors.

Also see Figure S3.

Together, sequence and structure reveal differing conservation patterns that allow sub-classification into four subgroups: (1) no/little additional conservation apart from the primary Ub-binding site (NPL4, ZRANB3, and HOIP NZF2), (2) sequence conservation between the two C-X-X-C motifs (TAB2/3 and TRABID NZF1/2/3), (3) sequence conservation after the second C-X-X-C motif (HOIP NZF1, Sharpin, RYBP, YAF2, and CAPN15), and (4) sequence conservation before the first C-X-X-C motif (CAPN15 NZF2) (Figure 3A). HOIL-1L, an M1-specific NZF domain, would be classified as having only the primary Ub-binding site within the NZF domain; however, HOIL-1L uses an α-helical C-terminal extension to facilitate M1 linkage specificity, which was explained by crystal structures (Figure 3B).17 Indeed, the proximal Ub-interacting residues are evolutionarily invariant in HOIL-1L (Figure S3A). In the case of CAPN15, the entire stretch of residues between NZF1 and NZF2 is conserved and also folds into a short, conserved, amphipathic helix. We tested longer constructs encompassing NZF1 and 2 and the interspersing stretch in pull-down assays against diUb (Figure S1F), and this slightly improved diUb binding but did not sharpen linkage preference. Since the NZF domains are predicted to be somewhat separated, it is possible that CAPN15 recognizes longer chains, which remains to be tested. Conservation analysis hence explained that, while some NZF domains are linkage specific and contain two Ub-binding sites (Figure 3B, top row), the majority of NZF domains only comprise one Ub-binding site (Figure 3B, center/bottom rows).

The third group was most intriguing: NZF domains lacking linkage preference but showing an additional conserved surface patch of unknown function (Figure 3B, bottom row). In all cases, this additional patch was predicted to be surface-exposed by AlphaFold, and all NZFs were embedded within a flexible loop region (Figures S3B–S3F; see below). We wondered whether these UBDs had evolved to recognize ubiquitinated targets in a site-specific fashion.

HOIP NZF1 is a selective receptor for K285-ubiquitinated NEMO

The HOIP NZF1 domain does not show any linkage preference despite featuring a second conserved patch near the C terminus of the bound Ub (Figures 3A, 3B, and S4A). Since this site is C-terminal to Ub, we reasoned that this might be a binding site for a substrate. Interestingly, it has been shown that NEMO, binds HOIP through this surface.41 When Ub was modeled onto the structure of the HOIP NZF1:NEMO UBAN complex, the C terminus of Ub pointed toward K285 of human NEMO (K278 in mouse) (Figure S4B). Mutational analysis and functional studies had indicated key roles for NEMO ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling and showed that K285 of NEMO is a particularly important ubiquitination site that is, e.g., upregulated >30-fold in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha in A549 cells (Figure S4C).42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 K285 is the most frequently described ubiquitination site on NEMO that can be ubiquitinated by E3 ligases such as cIAP,45 TRAF2,42 TRAF6,42,43,45,51 and LUBAC.44,46 It is currently unclear how and why all these E3 ligases appear to preferentially target a specific Lys on NEMO to regulate NF-κB activation. A second possibility is that, upon complex formation, the NZF domain stabilizes the ubiquitination of K285 by preventing deubiquitination of this site by deubiquitinases.

Conservation analysis of the NEMO UBAN domain shows that K285, the interaction surface for HOIP NZF1, and the binding patch for M1 diUb are well conserved (Figure S4D). A competition pull-down experiment demonstrated that HOIP NZF1, while capable of binding to non-ubiquitinated NEMO, has a clear preference for K285-ubiquitinated NEMO (Figure 4A). To understand more about this interaction, a crystal structure of chemically K285C-ubiquitinated NEMO UBAN (residues 257–340, generated utilizing a K285C mutant that was modified with Ub G76C; STAR Methods) bound to HOIP NZF1 was determined to 3.3-Å resolution (Figures 4B and S4E; Table 1). The asymmetric unit contained two NEMO UBAN coiled coils, two HOIP NZF1 domains, and three Ub molecules (Figure S4E). The NZF1 domain of HOIP sits between Ub and the UBAN of NEMO, binding the I44 patch of Ub through its canonical TF motif and interacting with mostly hydrophobic residues on NEMO UBAN through the second conserved binding patch (Figures 4C and 4D), as observed previously for the structure of the mouse proteins.41,52,53

Figure 4.

HOIP NZF1 is a substrate- and Ub site-specific receptor for NEMO ubiquitinated on K285

(A) In vitro pull-down experiment with His-SUMO-tagged HOIP NZF1 against NEMO UBAN and NEMO UBAN K285-Ub in isolation and in competition.

(B) Crystal structure of HOIP NZF1 (red) bound to NEMO UBAN (turquoise) chemically ubiquitinated on K285C (orange) (STAR Methods; Table 1; Figure S4).

(C) Close-up view of interactions between HOIP NZF1:NEMO UBAN. Dashed lines indicate polar interactions with backbone (∗) or side chains.

(D) Interactions of the canonical TF motif of HOIP NZF1 with the I44 patch of Ub. Zn-coordinating Cys residues are also shown.

Binding of NEMO to M1-linked Ub chains is considered an activating event during NF-κB signaling, and our structures predicted that NEMO K285 ubiquitination could happen alongside M1 diUb binding. His6-SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier)-tagged HOIP NZF1 was incubated with NEMO K285-Ub and either M1 diUb or K63 diUb to exclude direct binding of the diUb to HOIP NZF1. This experiment confirmed that NEMO K285-Ub can simultaneously interact with HOIP NZF1 and M1 diUb (Figure S4F). However, it cannot be ruled out that there is a certain degree of (anti-)cooperativity between these two events. A similar binding mode was suggested in a recent structural study.54

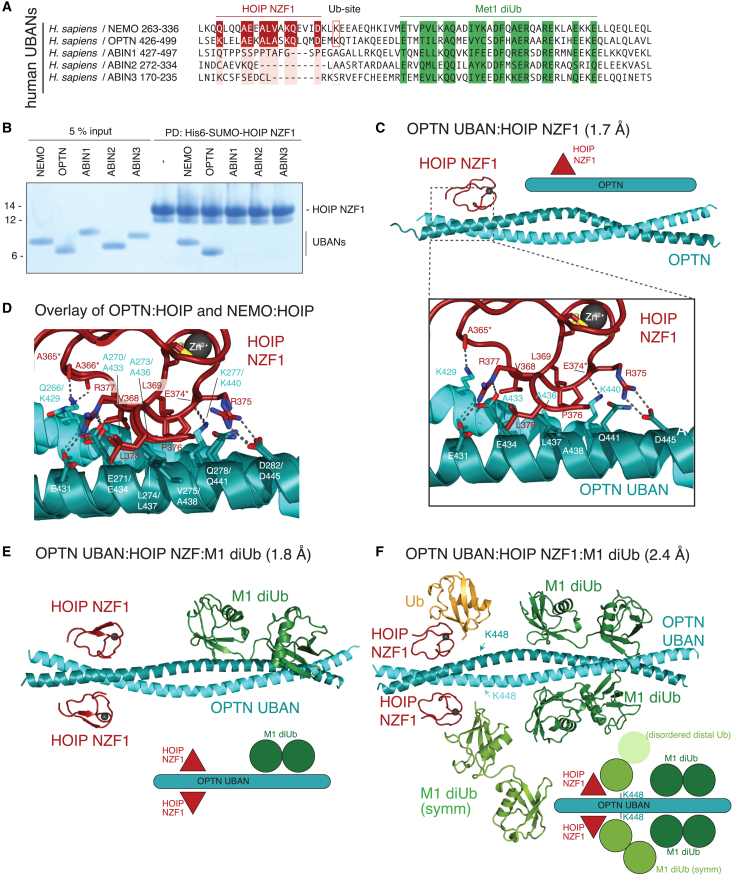

OPTN binds directly to HOIP NZF1 and M1 chains

Sequence analysis of other UBAN-domain containing Ub receptors revealed that the NZF-binding region in NEMO is conserved in OPTN but not ABIN1 (A20-binding inhibitor of NF-κB 1), ABIN2, or ABIN3 (Figure 5A). While there has been no biochemical or biophysical evidence of a direct interaction between HOIP and OPTN, an interaction was observed in overexpression experiments in HEK293T cells,55,56 HOIP was identified in an OPTN proximity labeling experiment,56 and HOIP co-localized with OPTN foci upon poly(I:C) treatment.56 We tested whether OPTN binds directly to the NZF1 domain of HOIP in a similar manner as NEMO. Pull-down of HOIP NZF1 showed a clear direct interaction with OPTN, but no binding to ABIN1, ABIN2, or ABIN3 (Figure 5B). More similarities exist when ubiquitination and Ub binding is considered. K448 in OPTN is located at the equivalent position to K285 in NEMO. K448 is a known ubiquitination site in OPTN, although not as often observed as K285 in NEMO.49,57,58,59 The NZF1 binding region, K448, and Ub-binding regions of OPTN are all well conserved or invariant across species (Figure S5A).

Figure 5.

OPTN UBAN can also bind HOIP NZF1 and form a trimeric complex with M1 diUb

(A) Sequence alignment of human UBANs. Highlighted are regions of conservation that bind to M1 diUb (green), HOIP NZF1 (red), or lysines that are known to be ubiquitinated.

(B) Pull-down of His-SUMO-tagged HOIP NZF1 against UBAN domains of NEMO, OPTN, and ABIN1–ABIN3.

(C) Crystal structure of OPTN UBAN (turquoise) in complex with HOIP NZF1 (red). An inset shows the close up of the interaction. Dashed lines indicate polar interactions with backbone (∗) or side chains.

(D) As in (C) but overlaid with HOIP NZF1:NEMO (PDB: 4owf41). UBAN residues are labeled for NEMO/OPTN.

(E) Structure of the first crystal form of OPTN UBAN (turquoise) in complex with HOIP NZF1 (red) and M1 diUb (green).

(F) Structure derived from the second crystal form of OPTN UBAN (turquoise) in complex with HOIP NZF1 (red) and M1 diUb (green), with five Ub molecules in the asymmetric unit that form symmetry contacts. K448 in OPTN, a known but not frequently observed ubiquitination site, corresponds to K285 in NEMO.

A co-crystal structure of HOIP NZF1 bound to OPTN was resolved to 1.7 Å (Figures 5C; Table 1), with an asymmetric unit containing two OPTN coiled coils and two HOIP NZF1 domains (Figure S5B). HOIP bound similarly to OPTN as to NEMO by using the secondary patch of NZF1 and forming a combination of hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges using near-identical residues of HOIP, from A365 to R375 (Figure 5D). As expected, the coil-coiled platform of OPTN strongly resembled NEMO, providing residues to enable a near-identical binding mode to HOIP NZF1 (Figures 5D and S5C).

Binding of the OPTN UBAN domain to M1- and K63-linked Ub chains was linked to its ability to suppress NF-κB signaling.55,60 Pull-down of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged OPTN UBAN and differently linked tetraUb chains demonstrated that the UBAN domain bound M1 chains preferentially over K6 and K63 tetraUb in isolation or in a competition experiment (Figure S5D). To better understand OPTN interactions, we crystallized the complex of OPTN UBAN, HOIP NZF1, and M1 diUb, resulting in two independent crystal structures with different molecular content and packing. The first, resolved to 1.8 Å, contained a single OPTN UBAN coiled coil bound to two HOIP NZF1 domains and one M1 diUb in the asymmetric unit (Figures 5E and S5E; Table 1). The HOIP NZF1 domain bound in an identical position as compared to the complex without diUb. The M1 diUb bound to OPTN at the expected location C-terminal to the HOIP NZF1, essentially as resolved previously (PDB: 5wq4 61). As observed previously,61 only one M1-diUb molecule binds OPTN, which is different from NEMO complex structures (PDB: 2zvo 62) but matches biophysical data on NEMO diUb interactions.53,62,63

A second crystal form led to a 2.4-Å structure with a different asymmetric unit and packing (Figures 5F and S5F; Table 1). The core structure of OPTN and HOIP NZF1 is identical, and in this crystal form, two M1-diUb molecules are bound symmetrically to the OPTN UBAN Ub-binding sites (Figure 5F). Intriguingly, this crystal form contained an additional poorly ordered M1-diUb bound to HOIP NZF1 on one side of the UBAN dimer; only the proximal Ub moiety is partially resolved and monoUb was modeled. The C-terminal tail of this additional NZF1-bound Ub extends toward K448 of OPTN. In fact, symmetry expansion also shows that the proximal Ub of one of the M1-diUb molecules bound at the UBAN, simultaneously interacts with the NZF1 domain of HOIP, and extends its free C terminus toward K448, again forming a symmetric interaction. Overall, this structure clearly indicates that an analogous ubiquitination event of K448 in OPTN, just like K285 in NEMO, could be preferentially recognized by HOIP (Figure 5F).

Together, our structures are consistent with the idea HOIP binding to ubiquitinated NEMO or OPTN can co-occur with M1-diUb binding to NEMO or OPTN in independent or interdependent events. However, we cannot exclude that a longer Ub chain (>3 Ub molecules) bound at the UBAN domain, could satisfy UBAN and NZF1 Ub binding sites in non-covalent interactions. Here it is interesting to note that the most frequently observed ubiquitination site in OPTN is K501 (>40 reports listed in www.phosphosite.org). K501 is located toward the C-terminal end of our 2.4-Å structure, and it appears possible that M1-diUb modification of this residue could occupy the UBAN domain in cis, and perhaps, M1-polyubiquitination could further occupy and strengthen interactions with HOIP NZF1 (and NZF2). Unfortunately, definitive identification of linkage type and chain length for a specific ubiquitination site for a given protein is out of reach for current methodologies.

A model for direct binding of NEMO or OPTN to HOIP/LUBAC

We next considered the observed HOIP:UBAN binding mode in the context of full-length HOIP models. The best models for HOIP rely on AlphaFold and a low-resolution cryoelectron microscopy structure and intramolecular crosslinking,64 which are consistent inasmuch as both indicate intrinsic interactions between the N-terminal PUB (peptide:N-glycanase and UBA or UBX-containing proteins) domain and the C-terminal RING-between-RING (RBR)/ (Linear ubiquitin chain determining domain (LDD) module in isolated HOIP (Figures S6A and S6B). Additionally, in vitro ubiquitination assays have demonstrated that the N-terminal portion of HOIP is autoinhibitory to RBR activity and that this inhibition is released upon complex formation with Sharpin and HOIL-1L.65

The relative disposition of the three central ZnF/NZF1/NZF2 modules in the AlphaFold model suggests a high degree of flexibility due to extensive unstructured linkers and drew our attention to the RanBP2-like ZnF domain of HOIP that, to date has no function assigned (Figure 6A). A sequence alignment of ZnF/NZF1 reveals that the ZnF domain lacks the Ub-binding TF motif but shows striking conservation of the NEMO/OPTN UBAN binding site (Figure 6B). Indeed, molecular docking the ZnF/NZF1/NZF2 modules onto NEMO UBAN using Colabfold66 readily places the ZnF and NZF1 domains onto their binding sites on NEMO, with the linker spanning around the coiled coil (Figure 6C). The second Ub-binding NZF2 domain may interact with polyubiquitinated (NEMO/OPTN) substrates; dual NZF constructs have not shown any chain preference,24 consistent with a long linker that provides considerable flexibility (Figure 6C). Preliminary assessments of binding of the isolated HOIP ZnF domain to NEMO or OPTN did not reveal measurable binding on their own, consistent with the idea that the ZnF/NZF1 module of HOIP require synergistic, Ub-driven interactions with UBAN domains in NEMO and OPTN (Figure 6D). Future studies of these difficult-to-produce constructs will be required to validate this model.

Figure 6.

HOIP ZnF and NZF1 domains display conserved UBAN binding sites

(A) In the AlphaFold2 model of HOIP (Figure S6), the ZnF and NZF1 domains are juxtaposed.

(B) Sequence alignments of the ZnF and NZF domains. Ub binding residues are indicated in orange, while NEMO/OPTN binding residues are indicated in turquoise.

(C) Colabfold66 model of the ZnF/NZF1/NZF2 domains of HOIP with the UBAN domain of NEMO, indicating how HOIP could clamp UBAN domains.

(D) Model of HOIP/LUBAC interaction with NEMO/OPTN.

Also see Figure S6.

Discussion

The Ub system continues to present many conundrums. While much progress has been made to understand Ub attachment and removal, comparably less is known about how UBD-containing readers of the Ub code are able to respond to low-abundance substrates that are ubiquitinated at low stoichiometry—often only 1% of total protein is modified, and modification may be scattered across sites—which puts the quantity of a specific ubiquitinated substrate in the cell at a picomolar or femtomolar concentration or, in a single cell, at tens to hundreds of individual molecules. This vanishingly low amount of ubiquitinated substrates is set against a backdrop of 10–20 μM free monoUb in most cell types or 500,000 copies of free Ub per cell.14

Some of the specificity of the Ub system arises from Ub chains and from the fact that select Ub chain architectures signal outcomes through dedicated receptors. By now, most of the Lys-linked chain types and some more complex chains (longer homotypic chains, or branched architectures) have been associated with a comparably low number of specific UBDs. In some cases, small UBDs are concatenated, and the context of their juxtaposition determines chain preferences. In related scenarios, a “main” canonical UBD may be flanked by lower-affinity, cryptic UBDs that do not bind Ub with appreciable affinity on their own but that attach to a chain and provide avidity and specificity once the first Ub is recognized. Other small UBDs provide linkage specificity by interacting with two Ub molecules in a chain so that only a subset of chain types can bind. We here focus on one such family; namely, the UBDs of the NZF family.

Several NZF family members, including those found in TRABID, HOIL-1L, and TAB2/3, were already known to be linkage selective, but not all members had been studied comprehensively. All 15 annotated human NZF domains bound Ub, but only the listed ones as well as Sharpin showed signs of linkage preference due to a dual Ub binding mode. This had been structurally understood in TRABID19,20 and HOIL-1L.17 For TAB2 and TAB3, early data (before other chain types were available) explained K63 preference,16,18 while more comprehensive later studies also revealed binding to K6 chains.26,27 Indeed, using biolayer interferometry, Zhang et al. found a 4-fold preference of TAB2 NZF for K6 over K63-linked diUb and higher specificity over K48-linked diUb.26 K6 linkages are obscure chain types of low abundance but with emerging cellular functions in mitophagy,31,35,36,67 p97-mediated processes,68 and, recently, resolution of RNA-protein crosslinks.69,70 An affimer for this chain type revealed E3 ligases and substrates.36,71 Importantly, mitophagy is more complex inasmuch as Ub is also phosphorylated by PINK1.34,72 Indeed, our structures explain how the TAB2 NZF domain preferentially binds K6 dimers where phosphorylated S65 contributes additional inter-Ub interactions to strengthen the TAB2 binding diUb conformation. These findings explain the otherwise puzzling earlier observation that a TAB2 NZF-based Ub sensor was labeling depolarized mitochondria37; we now re-interpret these data and posit that phosphorylated K6 chains are the reason why TAB2 labels depolarized mitochondria. It also raises the question of whether the TAK1 complex, comprising TAK1, TAB1, and TAB2 or TAB3, has roles in mitophagy; mitophagy has been linked to the activation of NF-κB signaling,73,74 and TAK1 inactivation causes accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria.75

It was perhaps surprising, however, that not more NZF domains bind chains in a linkage-specific fashion, especially when we realized that a subset contains additional conserved patches. We hypothesized that these domains could indeed explain the mentioned conundrum, by representing UBDs that bind both substrate and Ub in a ubiquitination site-specific manner. This model could, for example, apply to YAF2 and RYBP, both of which have been linked to histone H2K119 ubiquitination via the PRC1 complex.76,77 Secondary patches of unknown function were also present in NPL4, which is an adaptor of the p97 complexthat recognizes polyubiquitinated substrates, and in the uncharacterized calpain cysteine protease CAPN15.

We decided to further study HOIP. The NZF1 domain of HOIP interacts with NEMO and Ub, and the importance of both has been demonstrated with point mutations.41 Modeling of this interaction highlights the importance of K285, the most strongly and quickly induced ubiquitination site of NEMO.50,78 NF-κB activation is blunted in cells and in animal models when K285 is mutated. Our biochemical and structural studies on chemically K285-ubiquitinated NEMO (using a Cys-crosslinking strategy) with HOIP reveal the molecular basis for this bi-partite recognition as well as the seemingly independent M1-Ub binding, which is consistent with recent studies.54 Both may be relevant for LUBAC-regulated innate immune signaling and NF-κB activation41,79 inasmuch as it may explain how upstream E3 ligases such as TRAFs and cIAP42,43,44,45,51 induce recruitment of LUBAC by ubiquitinating NEMO, while HOIP M1 chain assembly on NEMO (including on K285 itself46) and other complex components enables interconnected multivalent complexes.80,81 Indeed, the HOIP enzymatic mechanism would require or at least prefer an already monoubiquitinated substrate.82,83 It is possible that HOIP merely extends chains on NEMO and that the NZF domain(s) help in substrate positioning. Indeed, we show that substrate binding is likely also facilitated by the HOIP ZnF domain that features a conserved UBAN binding site (Figure 6).

We further generalized these studies, showing that HOIP NZF1 interacts in a highly similar fashion with OPTN. A known OPTN ubiquitination site, K448, is structurally equivalent to NEMO K285, and while K448 has been identified in ubiquitinomics studies, this site is not induced; e.g., by TNF (tumor necrosis factor) treatment.78 OPTN tends to be protective in most autophagy-associated diseases, though the molecular mechanism of OPTN regulation in these diseases is not well understood. OPTN is a multifunctional protein that can contribute at multiple steps during autophagy: it acts as an autophagy receptor, connecting LC3-positive phagophore membranes with ubiquitinated autophagy substrates, and can initiate and accelerate the autophagic process.84,85 As such, OPTN is important in mitophagy86 but also xenophagy, where both LUBAC and OPTN are recruited to intracellular bacteria.24,87

Mutations in OPTN cause the fatal neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), characterized by the aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in affected motor neurons.88 There has been particular focus on the missense mutation E478G in the M1-binding region that abrogates binding to Ub and results in impaired xenophagy,89 aggrephagy,90 and mitophagy.91

We here establish a molecular interaction between OPTN and LUBAC, corroborating a role of LUBAC signaling in ALS and autophagy. Our data may underpin the observations that M1 chains and LUBAC colocalize with intracytoplasmic inclusions in motor neurons and that LUBAC inhibition ameliorates this proteinopathy in OPTN knockout cells.55,92,93 Indeed, ALS-associated OPTN mutations of unknown function are present close to K448, including M447R, I451T, and Q454E.88 The key role of LUBAC in inflammation may hence contribute to its role in neuroinflammatory diseases.

Our work highlights how the 30-residue NZF UBD family continues to provide fascinating global insights into the Ub system. Some NZF domains in intriguing proteins remain poorly studied, such as in CAPN15, ZRANB3, and YAF2/RYBP, and it will be interesting to see how they utilize Ub signals. Importantly, our concept that even small UBDs may harbor conserved secondary patches that enable recognition of ubiquitination-site-specific substrate interfaces could be applicable to other domain families. Of special interest here are UBA (Ub-associated) and CUE (coupling if Ub to ER-associated degradation) domains, which mostly display low Ub affinity, but, akin to NZF domains, some feature conserved secondary patches that can instill linkage preference. Therefore, small UBDs themselves could provide previously unappreciated layers of specificity in the Ub system.

Limitations of the study

Various limitations emerge with characterization of isolated domains for biochemical properties such as Ub binding. Flanking sequences of UBDs in the full-length protein context, as well as the structural context in larger multiprotein complexes, could contribute to sharpen or soften UBD preferences. While we have tried to account for this for a subset of NZF proteins in multi-UBD proteins (e.g., by using various CAPN15 constructs), the linkage and/or target preference presented here require validation in full-length proteins and in cells. Similarly, the model provided in Figure 6 requires validation by biochemical and cell biological studies.

A further limitation in the Ub field is the difficulty of studying homogeneously (mono)ubiquitinated proteins, relevant for our key finding that some NZF domains recognize the first Ub attached to a substrate by interacting with both substrate and Ub. While for NEMO, we engineered a ubiquitinated substrates with Cys chemistry, other proteins are less amenable to this approach. Therefore, our work on OPTN should be regarded as a starting point to assess whether K448-ubiquitinated OPTN preferentially recruits and cooperates with LUBAC in a cellular setting.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Ubiquitin (Ubi-1) | Novus Biologicals | Cat#NB300-130; RRID: AB_2238516 |

| HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse | Cytiva | Cat#NA931; RRID: AB_772210 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| K27 diUb | UbiQ | Cat#UbiQ-015 |

| Deposited data | ||

| TAB2 NZF:K6 diUb structure | This study | PDB: 9AVT |

| TAB2 NZF:K6 diUb pS65prox structure | This study | PDB: 9AVW |

| HOIP NZF1:NEMO UBAN-Ub | This study | PDB: 9AZJ |

| HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN | This study | PDB: 9B0B |

| HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN:Met1 diUb | This study | PDB: 9B12 |

| HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN:Met1 diUb | This study | PDB: 9B0Z |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for cloning | This study | Table S1 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pOPINK-CAPN15 NZF1 (1–42) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-CAPN15 NZF2 (34–72) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK- CAPN15 (N)ZF1-3 (1–173) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-CAPN15 ZF3 (141–173) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-CAPN15 ZF4 (337–369) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-CAPN15 ZF5 (411–444) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-HOIL-1L NZF (195–252) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-Sharpin NZF (347–376) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-RYBP NZF (20–51) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-NPL4 NZF (574–608) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINK-ZRANB3 NZF (619–650) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINS-HOIP NZF1 (351–379) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINB-NEMO UBAN (257–340) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINB-OPTN UBAN (419–512) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINB-ABIN1 UBAN (407–496) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINB-ABIN2 UBAN (255–345) | This study | N/A |

| pOPINB-ABIN3 UBAN (150–223) | This study | N/A |

| pGex6P1-NEMO UBAN (257–364) | (Komander et al.)94 | N/A |

| pOPINJ-TAB2 NZF (585–693) | (Kulathu et al.)16 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Phaser | (McCoy et al.)95 | https://www.phaser.cimr.cam.ac.uk/index.php/Phaser_Crystallographic_Software |

| Aimless | (Evans et al.)96 | https://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/harry/pre/aimless.html |

| The STARANISO Server | Global Phasing Ltd. | https://staraniso.globalphasing.org/cgi-bin/staraniso.cgi |

| Phenix | (Adams et al.)97 | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | (Emsley et al.)98 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | (Jumper et al.)40 | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| PyMOL | Schrödinger, L. & DeLano, W., 2020. | https://www.pymol.org |

| Other | ||

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Roche | Cat#11697498001 |

| KOD HotStart Polymerase | Novagen | Cat#71086 |

| In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit | Clontech | Cat#638918 |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#DN25 |

| Glutathione resin | Amintra | Cat#AGS0100 |

| TALON resin | Clontech | Cat#635504 |

| NuPAGE 4%–12% Bis-Tris Gel | Invitrogen | Cat#NP0322 |

| Trans-Blot Turbo Nitrocellulose Membrane | Bio-RAD | Cat#1704158 |

| InstantBlue Coomassie Protein Stain | Abcam | Cat#ab119211 |

| Silver Stain Plus Kit | Bio-RAD | Cat#1610461 |

| Series S Sensor Chip CM5 | Cytiva | Cat#29149603 |

| Lysozyme | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#L6876 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, David Komander (dk@wehi.edu.au).

Materials availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available from the lead contact, and will be made available via Addgene.

Data and code availability

-

•

All data is available from the lead contact upon request. Crystallographic data and refined models have been submitted to the protein databank with accession codes listed in the key resource table and Table 1.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject participant details

All proteins were expressed in Rosetta2 (DE3) pLacI cells. Cultures for expression were grown from overnight cultures in 2xTY media supplemented with 35 μg/mL chloramphenicol and either 50 μg/mL kanamycin (for constructs in pOPIN vectors) or 100 μg/mL ampicillin (for constructs in pGex6P1). Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 ∼0.8, cooled to 20°C and induced with 300 μM IPTG. Pellets were harvested after overnight expression, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and frozen until use.

Method details

Molecular biology

DNA sequences were amplified from human cDNA and plasmids using KOD HotStart DNA polymerase. See Table S1 for Primer sequences. Constructs for CAPN15 NZF1 (aa 1–42), CAPN15 NZF2 (aa 34–72), CAPN15 (N)ZF1-3 (aa 1–173), CAPN15 ZF3 (aa 141–173), CAPN15 ZF4 (aa 337–369), CAPN15 ZF5 (aa 411–444), HOIL-1L NZF (aa 195–252), Sharpin NZF (aa 347–376), RYBP NZF (aa 20–51), NPL4 NZF (574–608) and ZRANB3 NZF (aa 619–650) were cloned into pOPIN-K using the In-Fusion HD Cloning kit. pOPIN-K encodes an N-terminal, 3C-cleavable His-GST tag. HOIP NZF1 (aa 351–379) was cloned into pOPIN-S which encodes an N-terminal His-SUMO tag. NEMO UBAN (aa 257–340) as well as OPTN UBAN (aa 419–512), OPTN UBAN (aa 419–512) C471S/S472E, ABIN1 UBAN (aa 407–496), ABIN2 UBAN (aa 255–345) and ABIN3 UBAN (aa 150–223) were cloned into pOPIN-B which encodes an N-terminal, 3C-cleavable His-tag. See Table S1 for primer sequences. A slightly longer version of NEMO UBAN (aa 257–364) in pGex6P1 with a 3C-cleavable GST-tag was described previously.94 The construct for TAB2 NZF (aa 585–693) is described in.16 Mutations were introduced by QuikChange using Phusion DNA polymerase.

Protein purification

Cell pellets were thawed, supplemented with DNaseI, lysozyme and protease inhibitor cocktail and lysed by sonication. All constructs in pOPIN vectors were purified by ion metal affinity chromatography using TALON resin. Cleared supernatant was added to the beads and washing was performed with lysis buffer. Proteins were cleaved at 4°C overnight on beads by addition of His-tagged 3C protease. Constructs in pGex6P1 were instead purified using glutathione beads (Amintra) but following the same protocol as for the TALON resin. Cleaved proteins were eluted from TALON or glutathione resin using lysis buffer. The eluate was concentrated and purified to homogeneity using size exclusion chromatography (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75, Cytiva) in SEC buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTT). Pure protein was pooled, concentrated, flash frozen and stored at −80°C.

Ub and its variants were expressed and purified as described,99 except that 4 mM DTT was included in buffers for variants containing Cys residues. Differently linked diUbs were assembled enzymatically as described.99 For generation of K6 diUb with a phosphorylated S65 in the proximal Ub, Ub 1–74 was phosphorylated by PINK1 and purified. It was then mixed 1:1 with Ub K6R in an assembly reaction containing NleL and OTUB1.99 Other phospho-permutations of K6 diUb were assembled analogously from Ub K6R and Ub 1–74.

Generation of chemically ubiquitinated UBANs

NEMO UBAN constructs (257–364 and 257–340) were mutated so they only contained one Cys residue at K285C (257–364 K285C/C347S and 257–340 K285C). NEMO UBAN was mixed with an 8-fold molar excess of Ub G76C and reduced for 1 h at 4°C in the presence of 1 mM TCEP. The sample was buffer exchanged into 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl and diluted to a total free thiol concentration of approximately 1 mM (i.e., 110 μM NEMO and 880 μM Ub). Then 1 mM CuSO4 pH 8.5 was added to the solution and left to react at 4°C for 10 min. The reaction mixture was purified by size exclusion chromatography (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75, Cytiva) in SEC buffer without reducing agent (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl).

Surface plasmon resonance

SPR experiments were carried out as previously described19 using a Biacore 2000 system (Cytiva). In brief, diUb species in 20 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.5 were immobilized onto activated CM5 chips (Cytiva) by injection at 100 ng/μL until ∼2000 RU was achieved. For affinity measurements, NZF domains were buffer exchanged into SPR buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and a dilution series was injected at temperature of 20°C for 60 s and equilibrium binding was observed. Data was fitted in Prism to a one-site specific binding model, except for HOIL-1L where a two-site specific binding model better described the data. For other linkage-specific NZFs, the two affinities were presumably too similar to resolve accurately in fitting.

Pull-downs

For pull-down experiments with NZF domains, 30 μg of the GST-fusion construct was immobilized on 30 μL of glutathione beads. The beads were then incubated in 700 μL pull-down buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% NP-40) with 1.5 μg of differently linked diUb for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed five times with pull-down buffer and the bound fraction analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen).

For pull-downs with HOIP NZF1, 20 μg of His6-SUMO-HOIP NZF1 was immobilized on 15 μL of TALON resin. Beads were resuspended in 500 μL pull-down buffer containing 10 mM imidazole and 5 μg of individual UBAN constructs (for NEMO, the 257–364 construct was used). Samples were incubated for 4 h at 4°C, and then beads were washed three times with pull-down buffer containing 10 mM imidazole prior to SDS-PAGE.

Proteins were visualized by either InstantBlue Coomassie Protein Stain (Abcam) or Silver Stain Plus Kit (Bio-RAD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, or by immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to a Trans-Blot Turbo PVDF membrane (BIO-RAD) and blocked in PBST containing 5% (w/v) milk for 1 h. Incubation with anti-Ub (Novus Biologicals), at a dilution of 1:1000, was performed overnight at 4°C prior to incubation with a secondary, HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed using ECL Prime Reagent (Amersham).

Crystallography

TAB2 NZF and K6 diUb were mixed at a 1:1 ratio to a final concentration of 16 mg/mL. The sample was mixed 1:1 with 2.2 M ammonium sulfate in a 200 nL drop at room temperature. Crystals of TAB2 NZF bound to K6 diUb pS65prox were grown as described above, except that the sample was mixed with 2.2 M ammonium sulfate and 20% glycerol. Crystals were cryoprotected in 3.5 M ammonium sulfate prior to vitrification.

NEMO UBAN (257–364) K285C-UbG76C and HOIP NZF1 were mixed at a 1:1.1 M ratio to a final concentration of 8 mg/mL 150 nL of this sample was then mixed with 50 nL reservoir solution containing 0.1 M Tris/Bicine pH 8.6, 24.2% PEG 500 MME, 8% PEG 20K, 0.03 M each of NaI, NaBr, and NaF. Crystals grew at room temperature and were cryoprotected in mother liquor containing 20% glycerol prior to vitrification.

For the OPTN UBAN:HOIP NZF1 structure, a OPTN UBAN construct (aa 419–512) with C472S, S473E mutations was used, which showed improved protein yield. OPTN UBAN:HOIP NZF1 were mixed at a 1:1.2 M ratio to a final concentration of 8.5 mg/mL. The sample was mixed 3:1 with reservoir solution containing 10% PEG 8K, 20% ethylene glycol, 0.1 M Tris/Bicine pH 8.5, 0.03 M MgCl2 and 0.03 M CaCl2. Crystals grew at room temperature and were cryoprotected in mother liquor containing 10% glycerol prior to vitrification.

OPTN UBAN:HOIP NZF1:M1 diUb were mixed at 1:1.2:1.2 M ratio to a final concentration of 16 mg/mL. For crystals that diffracted to 1.8Å, the sample was mixed 3:1 with reservoir solution containing 50% PEG 200 and 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5. Crystals were vitrified without further cryoprotection. For crystals that diffracted to 2.4Å, the sample was mixed 1:1 with reservoir solution containing 20% PEG 2K MME, 0.2 M TAO and 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5. Crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor containing 20% glycerol prior to vitrification.

Diffraction data was collected at DLS beamlines I24, I03 and I04 (see Table 1) and diffraction images were integrated using XDS.100 The two datasets for HOIP NZF1:OPTN UBAN:Met1 diUb were scaled anisotropically using STARANISO. All other datasets were scaled spherically in AIMLESS.96 The structures containing TAB2 were solved by molecular replacement in PHASER95 with TAB2 NZF:K63 diUb (PDB: 2wwz,16) but where the proximal Ub was removed. All other structures were solved by molecular replacement with NEMO UBAN:HOIP NZF1 (PBD: 4owf,41) but with a truncated coiled coil. Iterative rounds of automated refinement and manual model building were performed in PHENIX97 and COOT,98 respectively. Data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

Bioinformatic sequence conservation analysis

Full-length human sequences of all 11 NZF-containing proteins were searched for orthologues on the ConSurf server against the Uniref. 90 database with a BLAST E-value cut-off of 0.001 (http://consurf.tau.ac.il/).101 The resulting sequence alignments were manually curated to remove orthologues that do not contain a full NZF domain. The curated sequence alignment was then rerun on ConSurf and conservation scores extracted. To color conservation onto NZF:Ub structures/models, structures were collected from the PDB or AlphaFold. The loadBfacts plugin for Pymol was then used to replace the B factor columns with conservation scores. The color_b.py script (Robert L. Campbell, 2004) was used to color residues according to conservation scores: user_rgb=(86,9,171, 242,167,140, 255,255,255). For clustering, Manhattan distances of the conservation score matrix were calculated, and single linkage clustering performed in R.

Acknowledgments

We thank Balaji Santhanam (MRC LMB) for advice with bioinformatics, Malte Gersch and other members of the D.K. lab for reagents and advice, and beamline staff at ESRF and DLS for assistance. Access to DLS was supported in part by the EU FP7 infrastructure grant BIOSTRUCT-X (contract 283570). Work in the D.K. lab (Cambridge) was funded by the Medical Research Council (U105192732), the European Research Council (309756 and 724804), and the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine. M.A.M. was supported by a PhD fellowship of the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds and a Doc.Mobility fellowship of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Work in the D.K. lab (WEHI) is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator grant (GNT1178122).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M., S.S., and D.K.; investigation, M.A.M., S.S., and D.K.; writing, M.A.M., S.S., and D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K.

Declaration of interests

D.K. is founder, shareholder, and SAB member of Entact Bio and Proxima Bio.

Published: July 23, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114545.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Komander D., Rape M. The Ubiquitin Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko A., Ciechanover A. THE UBIQUITIN SYSTEM. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swatek K.N., Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016;26:399–422. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh E., Akopian D., Rape M. Principles of Ubiquitin-Dependent Signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;34:137–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617-062802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan M.T., Haj-Yahya M., Ringel A.E., Bandi P., Brik A., Wolberger C. Structural basis for histone H2B deubiquitination by the SAGA DUB module. Science. 2016;351:725–728. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge W., Yu C., Li J., Yu Z., Li X., Zhang Y., Liu C.-P., Li Y., Tian C., Zhang X., et al. Basis of the H2AK119 specificity of the Polycomb repressive deubiquitinase. Nature. 2023;616:176–182. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05841-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakeel S., Rajendra E., Alcón P., O’Reilly F., Chorev D.S., Maslen S., Degliesposti G., Russo C.J., He S., Hill C.H., et al. Structure of the Fanconi anaemia monoubiquitin ligase complex. Nature. 2019;226:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1703-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rennie M.L., Arkinson C., Chaugule V.K., Toth R., Walden H. Structural basis of FANCD2 deubiquitination by USP1-UAF1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021;28:356–364. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner A., Baur R., Teerikorpi N., Kaya D.U., Rape M. Multisite dependency of an E3 ligase controls monoubiquitylation-dependent cell fate decisions. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/elife.35407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magits W., Sablina A.A. The regulation of the protein interaction network by monoubiquitination. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022;73 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2022.102333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husnjak K., Dikic I. Ubiquitin-Binding Proteins: Decoders of Ubiquitin-Mediated Cellular Functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley J.H., Lee S., Prag G. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem. J. 2006;399:361–372. doi: 10.1042/bj20061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulathu Y., Komander D. Atypical ubiquitylation — the unexplored world of polyubiquitin beyond Lys48 and Lys63 linkages. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:508–523. doi: 10.1038/nrm3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clague M.J., Heride C., Urbé S. The demographics of the ubiquitin system. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alam S.L., Sun J., Payne M., Welch B.D., Blake B.K., Davis D.R., Meyer H.H., Emr S.D., Sundquist W.I. Ubiquitin interactions of NZF zinc fingers. EMBO J. 2004;23:1411–1421. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulathu Y., Akutsu M., Bremm A., Hofmann K., Komander D. Two-sided ubiquitin binding explains specificity of the TAB2 NZF domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1328–1330. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Y., Fujita H., Yoshikawa A., Yamashita M., Yamagata A., Kaiser S.E., Iwai K., Fukai S. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by the Npl4 zinc finger (NZF) domain of the HOIL-1L subunit of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20520–20525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y., Yoshikawa A., Yamashita M., Yamagata A., Fukai S. Structural basis for specific recognition of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains by NZF domains of TAB2 and TAB3. EMBO J. 2009;28:3903–3909. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michel M.A., Elliott P.R., Swatek K.N., Simicek M., Pruneda J.N., Wagstaff J.L., Freund S.M.V., Komander D. Assembly and specific recognition of k29- and k33-linked polyubiquitin. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristariyanto Y.A., Rehman S.A.A., Campbell D.G., Morrice N.A., Johnson C., Toth R., Kulathu Y. K29-selective ubiquitin binding domain reveals structural basis of specificity and heterotypic nature of k29 polyubiquitin. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanayama A., Seth R.B., Sun L., Ea C.-K., Hong M., Shaito A., Chiu Y.-H., Deng L., Chen Z.J. TAB2 and TAB3 activate the NF-kappaB pathway through binding to polyubiquitin chains. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato Y., Yoshikawa A., Mimura H., Yamashita M., Yamagata A., Fukai S. Structural basis for specific recognition of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains by tandem UIMs of RAP80. EMBO J. 2009;28:2461–2468. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott P.R. Molecular basis for specificity of the Met1-linked polyubiquitin signal. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016;44:1581–1602. doi: 10.1042/bst20160227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noad J., von der Malsburg A., Pathe C., Michel M.A., Komander D., Randow F. LUBAC-synthesized linear ubiquitin chains restrict cytosol-invading bacteria by activating autophagy and NF-κB. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sims J.J., Cohen R.E. Linkage-Specific Avidity Defines the Lysine 63-Linked Polyubiquitin-Binding Preference of Rap80. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X., Smits A.H., van Tilburg G.B.A., Jansen P.W.T.C., Makowski M.M., Ovaa H., Vermeulen M. An Interaction Landscape of Ubiquitin Signaling. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y., Okatsu K., Fukai S., Sato Y. Structural basis for specific recognition of K6-linked polyubiquitin chains by the TAB2 NZF domain. Biophys. J. 2021;120:3355–3362. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane L.A., Lazarou M., Fogel A.I., Li Y., Yamano K., Sarraf S.A., Banerjee S., Youle R.J. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 2014;205:143–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazlauskaite A., Kondapalli C., Gourlay R., Campbell D.G., Ritorto M.S., Hofmann K., Alessi D.R., Knebel A., Trost M., Muqit M.M.K. Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65. Biochem. J. 2014;460:127–139. doi: 10.1042/bj20140334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyano F., Okatsu K., Kosako H., Tamura Y., Go E., Kimura M., Kimura Y., Tsuchiya H., Yoshihara H., Hirokawa T., et al. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature. 2014;510:162–166. doi: 10.1038/nature13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ordureau A., Sarraf S.A., Duda D.M., Heo J.-M., Jedrychowski M.P., Sviderskiy V.O., Olszewski J.L., Koerber J.T., Xie T., Beausoleil S.A., et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveal a Feedforward Mechanism for Mitochondrial PARKIN Translocation and Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:360–375. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wauer T., Swatek K.N., Wagstaff J.L., Gladkova C., Pruneda J.N., Michel M.A., Gersch M., Johnson C.M., Freund S.M., Komander D. Ubiquitin Ser65 phosphorylation affects ubiquitin structure, chain assembly and hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2015;34:307–325. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harper J.W., Ordureau A., Heo J.-M. Building and decoding ubiquitin chains for mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:93–108. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt M.F., Gan Z.Y., Komander D., Dewson G. Ubiquitin signalling in neurodegeneration: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:570–590. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00706-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham C.N., Baughman J.M., Phu L., Tea J.S., Yu C., Coons M., Kirkpatrick D.S., Bingol B., Corn J.E. USP30 and parkin homeostatically regulate atypical ubiquitin chains on mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:160–169. doi: 10.1038/ncb3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gersch M., Gladkova C., Schubert A.F., Michel M.A., Maslen S., Komander D. Mechanism and regulation of the Lys6-selective deubiquitinase USP30. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:920–930. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Wijk S.J.L., Fiskin E., Putyrski M., Pampaloni F., Hou J., Wild P., Kensche T., Grecco H.E., Bastiaens P., Dikic I. Fluorescence-based sensors to monitor localization and functions of linear and K63-linked ubiquitin chains in cells. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swatek K.N., Usher J.L., Kueck A.F., Gladkova C., Mevissen T.E.T., Pruneda J.N., Skern T., Komander D. Insights into ubiquitin chain architecture using Ub-clipping. Nature. 2019;572:533–537. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tunyasuvunakool K., Adler J., Wu Z., Green T., Zielinski M., Žídek A., Bridgland A., Cowie A., Meyer C., Laydon A., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature. 2021;596:590–596. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03828-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujita H., Rahighi S., Akita M., Kato R., Sasaki Y., Wakatsuki S., Iwai K. Mechanism Underlying IκB Kinase Activation Mediated by the Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;34:1322–1335. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01538-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbott D.W., Yang Y., Hutti J.E., Madhavarapu S., Kelliher M.A., Cantley L.C. Coordinated regulation of Toll-like receptor and NOD2 signaling by K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:6012–6025. doi: 10.1128/mcb.00270-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh M.C., Kim G.K., Maurizio P.L., Molnar E.E., Choi Y. TRAF6 autoubiquitination-independent activation of the NFkappaB and MAPK pathways in response to IL-1 and RANKL. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tokunaga F., Sakata S., Saeki Y., Satomi Y., Kirisako T., Kamei K., Nakagawa T., Kato M., Murata S., Yamaoka S., et al. Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-kappaB activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:123–132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinz M., Stilmann M., Arslan S.Ç., Khanna K.K., Dittmar G., Scheidereit C. A Cytoplasmic ATM-TRAF6-cIAP1 Module Links Nuclear DNA Damage Signaling to Ubiquitin-Mediated NF-κB Activation. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niu J., Shi Y., Iwai K., Wu Z.-H. LUBAC regulates NF-κB activation upon genotoxic stress by promoting linear ubiquitination of NEMO. EMBO J. 2011;30:3741–3753. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ni C.-Y., Wu Z.-H., Florence W.C., Parekh V.V., Arrate M.P., Pierce S., Schweitzer B., Kaer L.V., Joyce S., Miyamoto S., et al. Cutting Edge: K63-Linked Polyubiquitination of NEMO Modulates TLR Signaling and Inflammation In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7107–7111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jun J.C., Kertesy S., Jones M.B., Marinis J.M., Cobb B.A., Tigno-Aranjuez J.T., Abbott D.W. Innate immune-directed NF-κB signaling requires site-specific NEMO ubiquitination. Cell Rep. 2013;4:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner S.A., Satpathy S., Beli P., Choudhary C. SPATA2 links CYLD to the TNF-α receptor signaling complex and modulates the receptor signaling outcomes. EMBO J. 2016;35:1868–1884. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiskin E., Bionda T., Dikic I., Behrends C. Global Analysis of Host and Bacterial Ubiquitinome in Response to Salmonella Typhimurium Infection. Mol. Cell. 2016;62:967–981. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sebban-Benin H., Pescatore A., Fusco F., Pascuale V., Gautheron J., Yamaoka S., Moncla A., Ursini M.V., Courtois G. Identification of TRAF6-dependent NEMO polyubiquitination sites through analysis of a new NEMO mutation causing incontinentia pigmenti. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2805–2815. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vincendeau M., Hadian K., Messias A.C., Brenke J.K., Halander J., Griesbach R., Greczmiel U., Bertossi A., Stehle R., Nagel D., et al. Inhibition of Canonical NF-κB Signaling by a Small Molecule Targeting NEMO-Ubiquitin Interaction. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep18934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivins F.J., Montgomery M.G., Smith S.J.M., Morris-Davies A.C., Taylor I.A., Rittinger K. NEMO oligomerization and its ubiquitin-binding properties. Biochem. J. 2009;421:243–251. doi: 10.1042/bj20090427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahighi S., Iyer M., Oveisi H., Nasser S., Duong V. Structural basis for the simultaneous recognition of NEMO and acceptor ubiquitin by the HOIP NZF1 domain. Sci. Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakazawa S., Oikawa D., Ishii R., Ayaki T., Takahashi H., Takeda H., Ishitani R., Kamei K., Takeyoshi I., Kawakami H., et al. Linear ubiquitination is involved in the pathogenesis of optineurin-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Loughlin T., Kruppa A.J., Ribeiro A.L.R., Edgar J.R., Ghannam A., Smith A.M., Buss F. OPTN recruitment to a Golgi-proximal compartment regulates immune signalling and cytokine secretion. J. Cell Sci. 2020;133 doi: 10.1242/jcs.239822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akimov V., Barrio-Hernandez I., Hansen S.V.F., Hallenborg P., Pedersen A.-K., Bekker-Jensen D.B., Puglia M., Christensen S.D.K., Vanselow J.T., Nielsen M.M., et al. UbiSite approach for comprehensive mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:631–640. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boeing S., Williamson L., Encheva V., Gori I., Saunders R.E., Instrell R., Aygün O., Rodriguez-Martinez M., Weems J.C., Kelly G.P., et al. Multiomic Analysis of the UV-Induced DNA Damage Response. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1597–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Povlsen L.K., Beli P., Wagner S.A., Poulsen S.L., Sylvestersen K.B., Poulsen J.W., Nielsen M.L., Bekker-Jensen S., Mailand N., Choudhary C. Systems-wide analysis of ubiquitylation dynamics reveals a key role for PAF15 ubiquitylation in DNA-damage bypass. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:1089–1098. doi: 10.1038/ncb2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gleason C.E., Ordureau A., Gourlay R., Arthur J.S.C., Cohen P. Polyubiquitin binding to optineurin is required for optimal activation of TANK-binding kinase 1 and production of interferon β. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:35663–35674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m111.267567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li F., Xu D., Wang Y., Zhou Z., Liu J., Hu S., Gong Y., Yuan J., Pan L. Structural insights into the ubiquitin recognition by OPTN (optineurin) and its regulation by TBK1-mediated phosphorylation. Autophagy. 2018;14:66–79. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1391970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rahighi S., Ikeda F., Kawasaki M., Akutsu M., Suzuki N., Kato R., Kensche T., Uejima T., Bloor S., Komander D., et al. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by NEMO is important for NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 2009;136:1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lo Y., Lin S., Rospigliosi C., Conze D., Wu C., Ashworth A., Eliezer D., Wu H. Structural Basis for Recognition of Diubiquitins by NEMO. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:602–615. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]