Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diabetic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a serious complication of diabetes. The role and mechanism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC)-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) in neuroinflammation post-ICH in patients with diabetes are unknown. In this study, we investigated the regulation of BMSC-exo on hyperglycemia-induced neuroinflammation.

AIM

To study the mechanism of BMSC-exo on nerve function damage after diabetes complicated with cerebral hemorrhage.

METHODS

BMSC-exo were isolated from mouse BMSC media. This was followed by transfection with microRNA-129-5p (miR-129-5p). BMSC-exo or miR-129-5p-overexpressing BMSC-exo were intravitreally injected into a diabetes mouse model with ICH for in vivo analyses and were cocultured with high glucose-affected BV2 cells for in vitro analyses. The dual luciferase test and RNA immunoprecipitation test verified the targeted binding relationship between miR-129-5p and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction, western blotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were conducted to assess the levels of some inflammation factors, such as HMGB1, interleukin 6, interleukin 1β, toll-like receptor 4, and tumor necrosis factor α. Brain water content, neural function deficit score, and Evans blue were used to measure the neural function of mice.

RESULTS

Our findings indicated that BMSC-exo can promote neuroinflammation and functional recovery. MicroRNA chip analysis of BMSC-exo identified miR-129-5p as the specific microRNA with a protective role in neuroinflammation. Overexpression of miR-129-5p in BMSC-exo reduced the inflammatory response and neurological impairment in comorbid diabetes and ICH cases. Furthermore, we found that miR-129-5p had a targeted binding relationship with HMGB1 mRNA.

CONCLUSION

We demonstrated that BMSC-exo can reduce the inflammatory response after ICH with diabetes, thereby improving the neurological function of the brain.

Keywords: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, Exosome, Diabetic cerebral hemorrhage, Neuroinflammation, MicroRNA-129-5p, High mobility group box 1

Core Tip: Diabetic intracerebral hemorrhage is a serious complication of diabetes. In this study, we investigated the effect of exosomes derived from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on the attenuation of neuroinflammation and neurological impairment after comorbid cerebral hemorrhage and diabetes. We also explored the specific mechanisms through which they perform their functions. Overall, we hypothesized that bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes could afford a novel remedy in the treatment of cerebral hemorrhage in patients with diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is characterized by elevated blood glucose levels. Persistent elevation of blood glucose can trigger oxidative stress and the inflammatory response, constituting the main mechanism behind the secondary damage to brain tissue after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)[1]. Neuroinflammation is a very complex process and is an important component of secondary injury[2]. Therefore, reducing neuroinflammation and neurological impairment after cerebral hemorrhage in DM patients has become an important focus in clinical management[3]. The treatment of cerebral hemorrhage is a global concern, but there is currently no specific targeted therapeutic approach[4]. This is largely due to the blood-brain barrier, which impedes the targeted delivery of most small molecule drugs to the affected area. Therefore, the discovery of a treatment that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and ensure the efficacy of drug delivery is urgently needed.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multifunctional stem cells with strong immunomodulatory, homeothermic, transdifferentiating, and paracrine abilities. MSCs have become the most extensively researched type of stem cell, and a large number of studies have demonstrated their safety and effectiveness in the treatment of many diseases[5]. Despite the availability of MSCs from various sources, bone marrow remains the predominant source. Bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) are the popular choice due to their advantages, including the abundant source and lack of ethical concerns[6]. MSCs can adhere to damaged tissues and differentiate to replace damaged tissue cells. However, only a tiny percentage of MSCs have been identified to survive in vivo and reach the injured site. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of MSCs is most likely attributable to their secretory capacity[7,8].

Exosomes (exo) are extracellular vesicles formed by the fusion of multivesicles to the plasma membrane. As a paracrine product, exo have therapeutic effects akin to those of parent cells, which can lessen immunogenicity and carcinogenic potential and improve transplant biocompatibility[9]. Therefore, using MSC-derived exo (MSC-exo) holds promise as a cell-free strategy for treating tissue damage.

It has been found that BMSC-derived exo (BMSC-exo) containing microRNA (miRNA)-21 can improve neuroplasticity and promote recovery of neurological function after cerebral hemorrhage[10]. In rat models of traumatic brain injury, BMSC-exo can effectively promote functional recovery by stimulating endogenous angiogenesis and neurogenesis and attenuating inflammatory responses[11]. It was shown that miR-26b-5p-modified BMSC-exo could inhibit the expression of inflammatory mediators after cerebral hemorrhage through the methionine adenosyl transferase 2A-mediated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 signaling pathway[12]. However, it is not known whether BMSC-exo are effective for treating cerebral hemorrhage in DM patients, and the underlying mechanisms have not been clarified.

In this study, we investigated the effect of BMSC-exo on the attenuation of neuroinflammation and neurological impairment after cerebral hemorrhage in DM mice and explored the specific mechanisms through which they perform their functions in depth. Overall, we hypothesized that BMSC-exo could afford a novel remedy in the treatment of comorbid cerebral hemorrhage and DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6 mice (20-22 g and 6-8 weeks of age) were used to establish DM with cerebral hemorrhage models. All mice were purchased from Changsheng Biology [License No.: SCXK (Liao) 2020-0001; Liaoning, Shenyang, China] and kept under a 12/12 hours light-dark cycle and given free access to food and water. The mice were acclimated to the experimental conditions for at least 1 week. Investigators who were blinded to group assignments evaluated all results. Animals were raised according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of Harbin Medical University (2022016). All animal experiments were carried out to reduce the number of animals[13].

Cell preparation

The mouse microglial BV2 cell line was purchased from Saibaikang (Shanghai) Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China) and utilized for the in vitro experiments[14]. The cell line was cultured in DMEM with high glucose (HG) + 10 mL/L fetal bovine serum + 1 mL/L penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C in an incubator at a 50 mL/L CO2 concentration. BMSCs were cultured in DMEM + 10 mL/L serum without added exo + 1 mL/L double antibody + 5 mL/L growth factor and were incubated at 37 °C at a CO2 concentration of 5 mL/L.

Isolation and characterization of BMSCs

The mouse femur was removed and fully immersed in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The epiphysis at both ends was excised, exposing the bone marrow cavity. Then, the femur was placed in a sterile petri dish containing 10 mL of complete culture medium. This flushing process was repeated three times to collect bone marrow cells. The cell suspension was pipetted to disperse the cells, and the bone marrow suspension was collected in a 15 mL centrifuge tube before being centrifuged at 1000 × g/minute at 24 °C for 5 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 6 mL of complete culture medium. The suspension was gently pipetted to make a single-cell suspension before being transferred to a complete medium. The third generation of cells was cultured to induce cartilage, osteogenesis, and adipogenic differentiation, followed by treatment with culture media. To identify their multidifferentiation potential, samples were stained with alcian blue, alizarin red, and oil red O.

Isolation and characterization of BMSC-exo

Cell supernatant (100 mL) was centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Once initially absorbed, the supernatant was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 minutes, then at 10000 × g for 30 minutes, and finally at 100000 × g for 90 minutes before being gently removed, washed with sterile PBS, and blow dried. The supernatant was then recentrifuged at 100000 × g for 90 min, and 100 μL sterile PBS was applied to precipitate the BMSC-exo. The BMSC-exo were stored at -80 °C for later use. The size of BMSC-exo was analyzed using a nanoparticle microscope (ZetaView; Particle Metrix, Ammersee, Germany). The morphology of the BMSC-exo was examined by transmission electron microscopy (SU5000; Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The surface markers of BMSC-exo were analyzed by western blot. The total protein content within the BMSC-exo was extracted through lysis, and the protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid kit (ST2222; Beyotime Biotech, Haimen, Jiangsu, China). After the sample was heated at 99 °C for 10 minutes, sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis was performed and the sample was transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The primary antibodies included cluster of differentiation (CD) 9 (1:1000; Abcam, Cam-bridge, United Kingdom), CD81 (1:1000; Abcam), and CD63 (1:1000; Abcam). The membrane was blocked with 5 mL/L bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated overnight with the primary antibody at 4 °C and secondary antibody at 37 °C for 1 hour.

Induction of ICH with DM model and BMSC-exo treatment

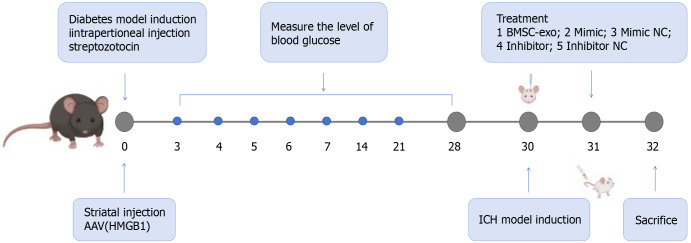

C57BL/6 mice, reared for 6-8 weeks, were intraperitoneally injected with streptozotoleutin (SolarBio, Beijing, China). Blood glucose levels were measured on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28, and blood glucose levels ≥ 16.7 were considered indicative of a successful model. An ICH model was induced after blood glucose was stabilized for 28 days. General procedures for inducing ICH in mice were carried out, as previously reported[15]. Mice were anesthetized with 3 mg/g isoflurane, which was reduced to 1 mg/g during the surgery. The head was shaved, and the skin was disinfected with betadine. A midline scalp was made, followed by drilling a 1 mm diameter burr hole on the left side of the skull at coordinates of 0.8 mm anterior and 2.2 mm lateral to the bregma. Using a 5 μL needle, we infused 0.075 U collagenase type VII-S (C2399-1.5KU, Type VII-S; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) in 0.5 μL sterile PBS through the hole at a depth of 2.7 mm. On the second day after the cerebral hemorrhage model was established, BMSC-exo, miR-129-5p-mimic/miR-129-5p-mimic negative control (NC), and miR-129-5p inhibitor/miR-129-5p inhibitor NC were injected through the tail vein, and the mice were executed on the following day (day 3). Specific modeling time points, drug treatments, and groupings are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Modeling time point, drug treatment, and grouping of animal models. HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; BMSC-exo: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes; NC: Negative control; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage.

We conducted the animal study in three segments. Experiment 1 involved C57BL/6 mice that were randomly divided into two groups: (1) ICH + DM (n = 6); and (2) ICH + DM + BMSC-exo (n = 6). BMSC-exo function was detected by immunofluorescence, western blot, brain water content assessment, nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and neurologic deficit scores. In experiment 2, the function of miR-129-5p in BMSC-exo was investigated. We randomly assigned C57BL/6 mice to six groups: (1) ICH + DM (n = 6); (2) ICH + DM + BMSC-exo (n = 6); (3) ICH + DM + miR-129-5p-mimic (n = 6); (4) ICH + DM + miR-129-5p-mimic NC (n = 6); (5) ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor (n = 6); and (6) ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC (n = 6). The function of miR-129-5p in BMSC-exo was detected by immunofluorescence, western blotting, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), brain water content assessment, MRI, and neurologic deficit scores. In experiment 3, inflammation factors in the C57BL/6 mouse models were investigated. The mice were randomly divided into three groups: (1) ICH + DM (n = 6); (2) ICH + DM + adeno-associated virus-high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (n = 6); and (3) ICH + DM + adeno-associated virus-NC (n = 6). The function of HMGB1 was detected by immunofluorescence, western blot, real-time qPCR, and ELISA.

Internalization of BMSC-exo

The enriched BMSC-exo was resuspended in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes with 500 μL PBS. Then, 50 μL exo-red mixture (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States) was added to the resuspended BMSC-exo, and the samples were incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. The labeling reaction was terminated by adding 100 μL complete medium, and the mixture was placed on ice for 30 minutes. The samples were centrifuged at 14000 × g for 3 minutes, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μL PBS.

BMSC-exo pretreatment with miR-129-5p

Four 5 mL sterile Eppendorf tubes were prepared. To each tube, 120 μL of Ribobio transfection buffer was added along with 13 μL of CP reagent to the mimic and mimic NC tubes and 12 μL of CP reagent for the inhibitor and inhibitor NC tubes. The contents were mixed thoroughly and incubated for 5 minutes at 24 °C. After incubation, 5 μL of mimic, 5 μL of mimic NC, 10 μL of inhibitor, and 10 μL of inhibitor NC were pipetted to the relevant tube and gently blown, mixed, and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. The final concentration of the mimic was 50 nM, and the final concentration of the inhibitor was 100 nM. After 24 hours, the old medium was aspirated and discarded, and a complete medium was added to continue the incubation. After 24 hours, the supernatant was collected for the extraction of BMSC-exo.

Detection of inflammatory cytokines

Based on an established protocol[16], 10 mg of the sample was weighed after cutting the specimen, and 100 μL PBS was added. The sample was maintained at 4 °C. The specimens were homogenized by hand and then centrifuged for 20 minutes at (2000-3000) × g, and the supernatant was collected. The levels of various cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, were measured using appropriate commercial ELISA kits (Yanzun, Shanghai, China).

Immunofluorescence assay

Formalin-fixed brain tissue samples from the mice were cut into 6 μm thick sections for immunofluorescence staining[17]. After blocking with 5 mL/L BSA, the samples were incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: HMGB1 (1:250; Abcam); ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (1:200; Abcam); glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:250; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States); and neun (1:250; Abcam). Then, the samples were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies (1:200; Abcam) at 37 °C for 1 hour. The samples were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at room temperature for 5-10 minutes, and the sections were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

qPCR

qPCR was performed to detect the expression levels of miR-129-5p and HMGB1 in BMSCs and brain tissues[18]. Total RNA and miRNA were extracted using total RNA and miRNA Isolation Kits (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, United States). The RNA concentration was determined using standard professional instruments (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). For reverse transcription, U6 (RNU6-1) was quantified as an internal miRNA control, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal RNA control. The relative expression of genes was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The PCR primers are listed in Table 1. All primers were synthesized by Tongyong Biotech (Chuzhou, Anhui, China).

Table 1.

The sequences of primers used in the experiments

|

Name

|

|

Sequence (5’-3’)

|

| miR-129-5p | Forward | CGGCGGTTTGCGGTCTGGGCT |

| Reverse | CAACTGGAGGACTCCATGCTG | |

| U6 | Forward | GATCTCGGAAGCTAAGCAGG |

| Reverse | TGGTGCAGGGAGGTAT | |

| mouseHMGB1 | Forward | ATCCCAATGCACCCAAGAGG |

| Reverse | CAATGGACAGGCCAGGATGT | |

| mouseGAPDH | Forward | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| Reverse | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTC | |

| mouseIL-6 | Forward | GGCCCTTGCTTTCTCTTCG |

| Reverse | ATAATAAAGTTTTGATTATGT | |

| mouseTNF-α | Forward | GACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT |

| Reverse | CCTCCACTTGGTGGTTTGCT |

HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from BV2 cells and brain tissues using pyrolysis liquid with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and were separated by sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis. Then, the separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5 mL/L BSA, the PVDF membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies, including CD9 (1:1000; Abcam), CD63 (1:1000; Abcam), CD81 (1:1000; Abcam), HMGB1 (1:10000; Abcam), Tlr4 (1:500; Abcam), Il-1β (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), Nf-κB (1:1000; Abmart, Shanghai, China), and tumor necrosis factor (Tnf)-α (1:1000; Abcam) at 4 °C overnight. The next day, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies (1:2500; Affinity Biosciences, Philadelphia, PA, United States) at 37 °C for 1 hour. The proteins were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Sweden/LAS 500) and analyzed using ImageJ software. β-tubulin (1:10000; Affinity Biosciences) served as the internal control.

RNA immunoprecipitation

BV2 microglial cells were used in the argonaute (AGO)-RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States). Briefly, we harvested 1 × 107 BV2 microglial cells with 1 mL PBS. After lysis with RIP buffer for 15 minutes on ice, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 (1:1000; Abcam) or anti-immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:1000; Abcam) overnight using protein A/G magnetic beads. Then, magnetic bead-bound complexes were washed with PBS six times. Finally, the immunoprecipitated RNAs were extracted and detected by qPCR.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

293T cells in the logarithmic growth phase were collected and seeded at a density of 1.0 × 104 cells per well into a 96-well plate, and 90 μL of complete medium and 10 μL of miRNA mimic and lipo6000TM mixture were added to each well. The final concentration of the mimic was 50 nM, and the final concentration of plasmids was 500 ng/mL. After 48 hours of transfection, the medium was removed, and 35 μL of luciferase reagent (Riebo Bio, Chengdu, China) was added to each well to measure the fluorescence (Veritas 9100-002 microplate reader). Finally, a stop reagent was added to measure the fluorescence intensity.

Calculation of hematoma volume

Cerebral hematoma volume measurements have been reported in the literature[19]. After the brain was extracted by perfusion, the tissue was sliced coronally in successive layers with a thickness of 1 mm in a stainless-steel mouse brain sectioning mold, placed sequentially on smooth photographic paper, and analyzed using ImageJ software. The area of each section with hemorrhagic foci was measured and multiplied by the thickness of 1 mm to determine the volume of the hemorrhagic foci in that section.

MRI scanning and measurements

During the MRI[20], mice were anesthetized with 2 mL/L isoflurane and pure oxygen. MRI scans were performed in a 9.4 Tesla scanner (Bruker, Breman, Germany) with the following parameters: Repetition time/effective echo time of T2 MRI, 4000/60 s; field of view, 20 mm × 20 mm; matrix, 256 × 256; echo spacing, 15 ms; and total scan time, 8 minutes 30 seconds.

Neurological deficit scores

The neurological function of the mice was evaluated using a 24-point neural score system[21]. The evaluation included body symmetry, gait, climbing behavior, circling behavior, forelimb symmetry, and forced circling behavior, each of which was rated on a scale of 0-4, with a total maximum score of 24 points (Table 2). Next, the mice were allowed to walk on a balance beam measuring 80.0 cm × 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm and elevated 10 cm above the ground, and the balance beam score was evaluated. The researchers were blinded to the study groups.

Table 2.

Neurological function rating scale

|

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

| Body symmetry | Normal | Slight asymmetry | Moderate asymmetry | Significant asymmetry | Extreme asymmetry |

| Gait | Normal | Stiffness and rigidity | Limping | Trembling, stumbling, falling | No walking |

| Climbing | Normal | Stressful climbing and weakness of limbs | Grasping the slope without sliding or climbing | Sliding down a slope, falling uncontrollably | Immediately slides and fallsun control-lably |

| Turning behavior | No appearance | Tendency to turn to one side | Occasional tendency to turn to one side | Constant tendency to turn to one side | Rotation, swaying, immobility |

| Anterior symmetry | Normal | Mild asymmetry | Significant asymmetry | Clearly asymmetry | Slight asymmetry, immobility of body limbs |

| Forced circling | No appearance | Tendency to turn to one side | - | - | - |

Evans blue

Blood-brain barrier permeability was assessed by Evans blue extravasation as previously described[22]. The tail vein was injected with a 4 g/100 mL Evans blue solution in normal saline. After perfusion with normal saline, trichloroacetic acid (0.1 mg/μL) was added to the brain samples, which were ground thoroughly. The samples were then incubated at 60 °C for 24 hours and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 620 nm using a spectrophotometer (BioRad, Hercules, CA, United States).

Cerebral edema measurement

The water and blood stains on the surface of the brains were blotted with filter paper. The whole brain was weighed on an electronic scale, and the weight of M1 was considered the wet weight of the mouse brain. Then, each brain was placed in a dryer for 16-24 hours and subsequently removed; the weight was measured again (M2), which was considered the dry weight of the mouse brain. The amount of cerebral edema was defined as (M1-M2)/M1 × 100%[23].

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis

The obtained differential miRNAs were annotated based on the Gene Ontology (GO) database to obtain all the functions that the genes are involved in. The significance level (P < 0.05) and false positive rate of each function were calculated using Fisher’s exact test and multiple comparison test.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis

The obtained differential miRNAs were subjected to Pathway Annotation based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database to obtain all the signaling pathways involved with the miRNAs. The significance level (P < 0.05) and false positive rate of each signaling pathway were calculated using Fisher’s exact test and multiple comparisons test.

Cell Counting Kit-8 measurement

BV2 microglia (2000 cells in 100 μL per well) were seeded into 96-well plates and divided into the following five groups (eight wells per group): BV2 group; HG + hemin; HG + hemin + BMSC-exo (25 μg/mL); HG + hemin + BMSC-exo (50 μg/mL); and HG + hemin + BMSC-exo (100 μg/mL). The cells were incubated for 24 hours, after which 10 μL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) (Biotime, Beijing, China) were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 hours. After incubation, the optical density value at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Model 680; BioRad). Cell viability was compared to that in the BV2 group (100%).

TUNEL staining

Brains of DM mice combined with cerebral hemorrhage were collected respectively, dehydrated and paraffin embedded, and cut into 2 μm thick paraffin sections. TUNEL staining was performed using an in situ apoptosis detection kit. Fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used for observation, and the cells with positive TUNEL expression were counted by ImageJ software.

Nissl staining

Brains of DM mice combined with cerebral hemorrhage were collected respectively, dehydrated and paraffin embedded, and cut into 2 μm thick paraffin sections. Neuronal staining was performed with Nissl staining solution. The number of positive cells, observed under microscope, was counted using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SD and compared using one-way variance analysis. GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, United States) was used for statistical analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

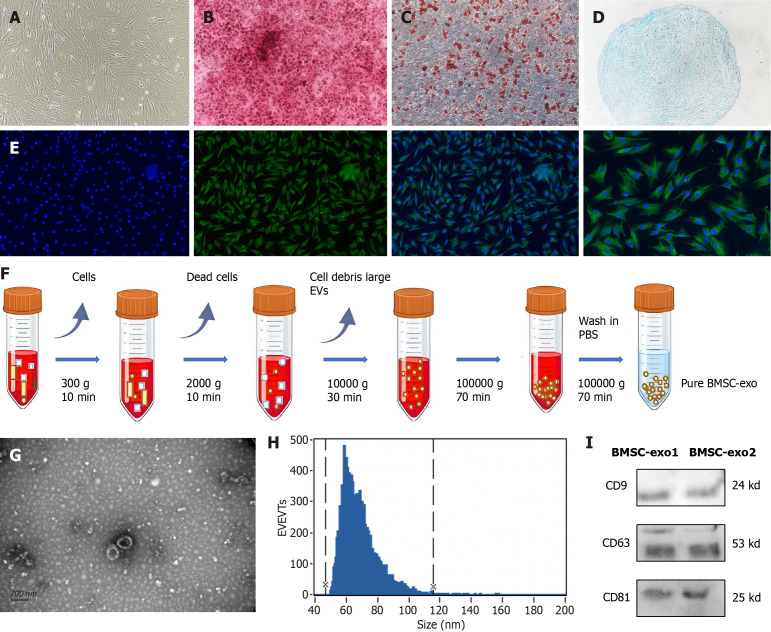

Characterization of BMSCs and BMSC-exo

The extracted BMSC were characterized. With the growth and proliferation of the BMSC, 2-3 generations of the BMSC fused into a single layer and presented with a long spindle-shaped morphology (Figure 2A). The BMSC were further induced to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes. The osteoblasts were stained with marine red (Figure 2B), the adipocytes with oil red O staining (Figure 2C), and the cartilage with alcian blue (Figure 2D) to verify the success of BMSC differentiation. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on the extracted BMSC, and CD44 was positive (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. A: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSC) were fusiform. Scale = 50 μm; B: Osteoblast alizarin red, before and after staining. Scale = 50 μm; C: Lipoblast oil red O, before and after staining. Scale = 50 μm; D: Formation of chondrospheres, stained with alcian blue. Scale = 50 μm; E: Cluster of differentiation (CD) 44 immunofluorescence staining. Scale = 50 μm/25 μm; F: Extraction of BMSC-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) by ultrafast centrifugation; G: BMSC-exo appeared saucer-shaped under electron microscopy. Scale = 200 nm; H: BMSC-exo particle microscopy with 47 nm and 116 nm diameters; I: Western blot analysis of protein expression of exosome markers: CD9; CD63; and CD81. EVs: Extracellular vesicles; PBS: Phosphate buffered saline; BMSC-exo: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes.

The process of centrifugation for BMSC-exo extraction is shown in Figure 2F. Electron microscopy was performed to confirm the identity of the isolated extracellular particles as exo. The images revealed that BMSC-exo exhibited a cup-shaped or round-shaped morphology (Figure 2G). Then, we analyzed the particle size using a nanoparticle tracking system and found that the diameter ranged between 47 nm and 116 nm (Figure 2H). Finally, western blot analysis of the protein expression of exo markers, including CD9, CD63, and CD81, provided additional confirmation of the exo (Figure 2I). BMSC-exo were successfully isolated and identified.

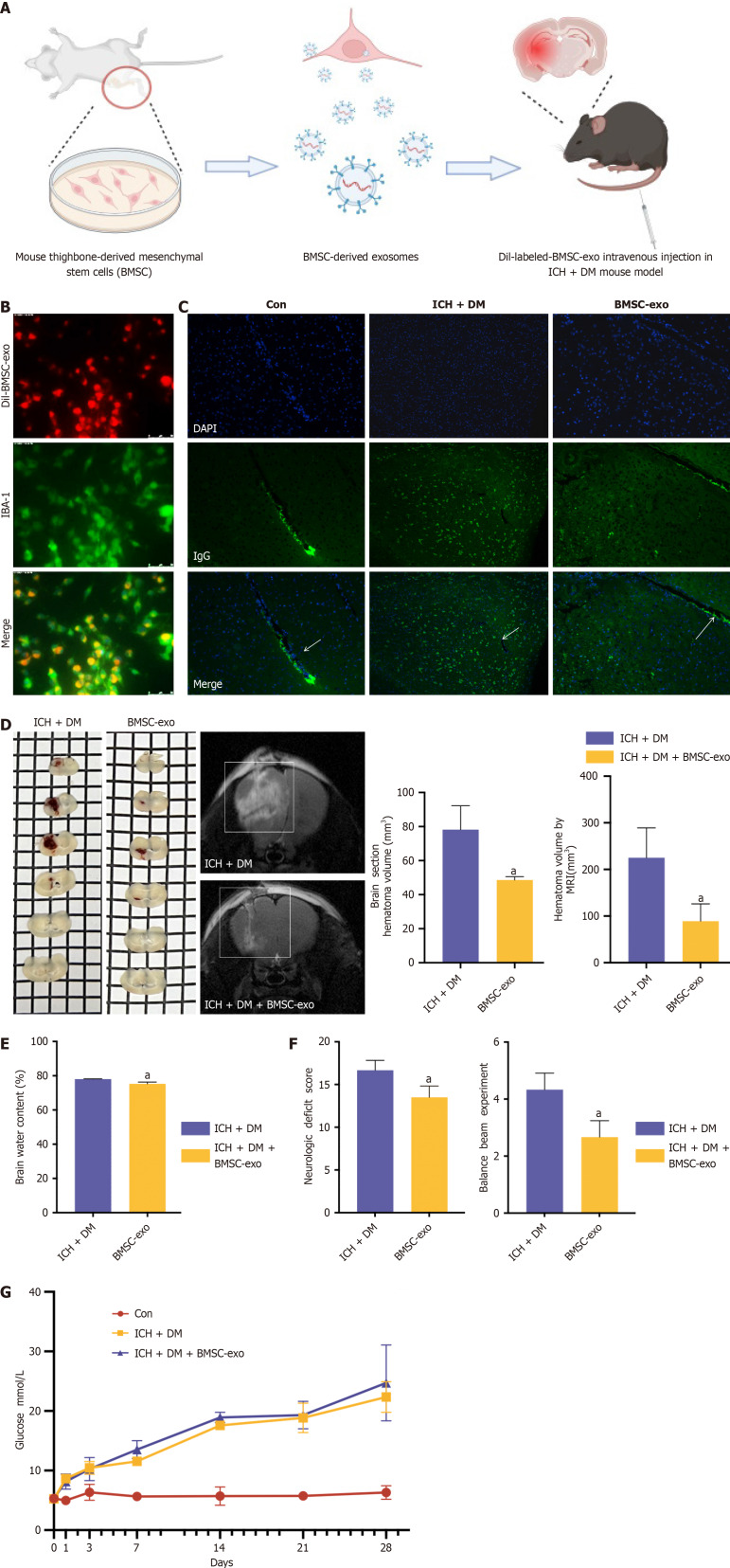

BMSC-exo attenuated neurological deficits in vivo

We explored the function of BMSC-exo in our mouse model of ICH with DM. To verify whether BMSC-exo could reach the injured brain, we intravenously injected BMSC-exo into each mouse (Figure 3A). The dil-labeled BMSC-exo were injected into the tail veins of mice, and the distribution of dil-BMSC-exo was observed in the mouse brain 24 hours after administration (Figure 3B). The experimental results showed that IgG was expressed in blood vessels in the control group. After DM and ICH were induced, IgG diffused through blood vessels into the brain parenchyma. After the administration of BMSC-exo, only a small amount of IgG was found to leak out of the blood vessels, which provided further evidence that BMSC-exo can significantly reduce the permeability of the blood-brain barrier in comorbid ICH and DM (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome attenuated neurological deficits in vivo. A: Dil-labeled bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) were injected in the tail vein of mice; B: Microglia (green) were labeled with ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 to observe the phagocytosis of BMSC-exo (red) by microglia. Scale bar = 50 μm; C: Immunofluorescence staining to observe the location of immunoglobulin G expression. Scale bar = 100 μm; D: Brain slices and hematoma volume were analyzed based on T2 magnetic resonance imaging. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) + diabetes mellitus (DM) group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group, t-test; E: Brain water content analysis. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group, t-test; F: Neurological function scores and balance beam scores. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group, t-test; G: The blood glucose levels of mice in each group were detected, and it was found that BMSC-exo could not reduce the blood glucose levels after diabetic cerebral hemorrhage in mice. Con: Control; BMSC-exo: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage; DM: Diabetes mellitus; IgG: Immunoglobulin G.

The functional experiments showed that BMSC-exo decreased the volume of brain hemorrhage, lowered brain water content, and improved neurological grading scores in the ICH + DM group (Figure 3D-F). Finally, following the quantification of blood glucose levels in mice injected with BMSC-exo, no significant change in the blood glucose level of mice in the BMSC-exo group was observed compared with the ICH + DM group (Figure 3G), suggesting that BMSC-exo do not mitigate neurological damage by lowering the blood glucose level of mice.

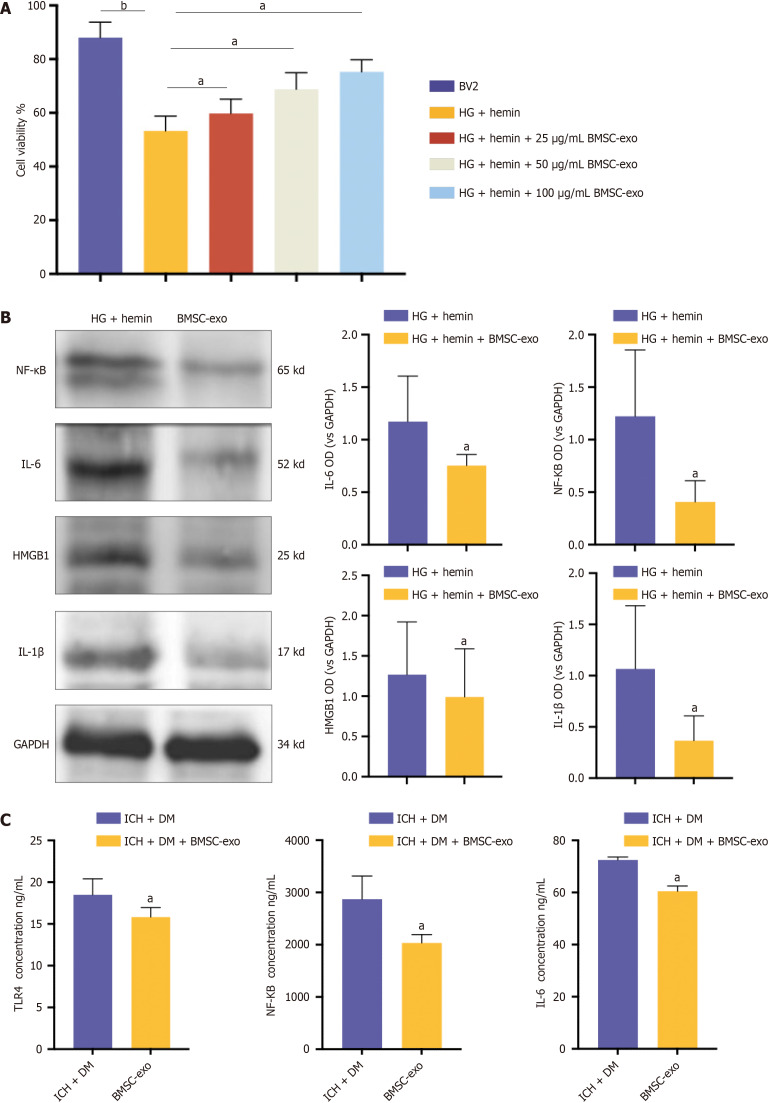

BMSC-exo attenuated neuroinflammation in DM mice with ICH

To verify the effect of BMSC-exo on microglia in vitro, we treated microglia with different concentrations of BMSC-exo to observe cell viability. The CCK8 results showed that cell viability increased with increasing exo concentrations. Notably, BMSC-exo concentrations of 25 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL had no significant effect on microglial viability. However, 100 μg/mL of BMSC-exo significantly increased microglial activity (Figure 4A). Therefore, in the subsequent experiment, we selected BMSC-exo with a 100 μg/mL concentration to treat microglia. The western blot results revealed that compared with hemin and HG-induced microglia, the expression levels of HMGB1 and its downstream inflammatory factors NF-κB, IL-6, and IL-1β in microglia treated with BMSC-exo were significantly decreased (Figure 4B). These data indicated that BMSC-exo reduced the inflammatory response of microglia induced by hyperglycoheme. The expression of inflammatory factors in the brain tissues of mice was detected by ELISA in vivo. The results showed that compared with mice in the ICH + DM group, the levels of the inflammatory factors TLR4, NF-κB, and IL-6 in the brains of mice in the BMSC-exo group were significantly reduced (Figure 4C). Both in vitro and in vivo results indicated that BMSC-exo reduced the neuroinflammatory response of DM complicated with ICH by reducing the expression level of inflammatory factors.

Figure 4.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome attenuated neuroinflammation in mice with diabetes and intracerebral hemorrhage. A: Microglia were treated with different concentrations of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo), and cell viability was observed using the cell counting kit-8 assay. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. bP < 0.01, BV2 group vs high glucose (HG) + hemin group; aP < 0.05, HG + hemin group vs HG + hemin + 25 μg/mL BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, HG + hemin group vs HG + hemin + 50 μg/mL BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, HG + hemin group vs HG + hemin + 100 μg/mL BMSC-exo group, t-test; B: Western blot assay was performed to detect the expression levels of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), interleukin (IL) 6, IL-1β, and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) inflammatory factors in the cells. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, HG + hemin group vs HG + hemin + BMSC-exo group, t-test; C: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection of toll-like receptor 4, NF-κB, and IL-6 expression. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) + diabetes mellitus (DM) group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group, t-test. BMSC-exo: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes; HG: High glucose; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; IL: Interleukin; HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; TLR: Toll-like receptor; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage.

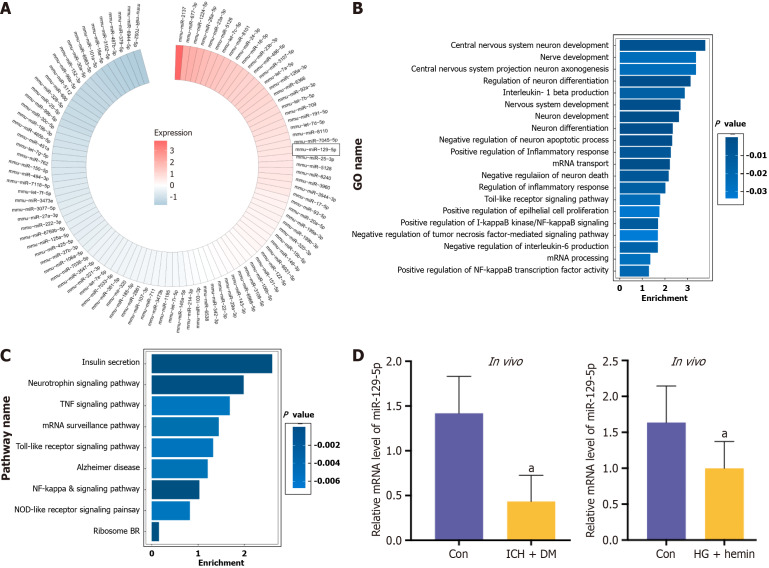

Screening for miRNA

MiRNA microarray sequencing of BMSC-exo was conducted, and the top 100 miRNAs present in BMSC-exo were identified and summarized (Figure 5A). At the same time, the GO functional enrichment analysis (Figure 5B) and KEGG analysis (Figure 5C) were performed. The results showed that the higher content of miRNAs were mainly involved in the regulation of biological processes and functions of neurological function, and the main biochemical metabolic pathway and signaling pathway was the regulation of inflammatory signaling pathway expression.

Figure 5.

Screening for microRNA. A: Heat maps showed microRNA content in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes; B: Gene Ontology functional enrichment analysis; C: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis; D: The expression of microRNA-129-5p in the intracerebral hemorrhage + diabetes mellitus mice and high glucose + hemin-treated BV2 was detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay. The experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. In vivo: aP < 0.05, control group vs intracerebral hemorrhage + diabetes mellitus group, t-test. In vitro: aP < 0.05, control group vs high glucose + hemin group, t-test. GO: Gene Ontology; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; HG: High glucose; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage.

Combining this information with the relevant literature, miR-129-5p was finally selected for subsequent experiments because of its high abundance in BMSC-exo. Many studies showed that miR-129-5p played an essential protective role in neurological diseases[7,24-29]. The expression of miR-129-5p was found to be significantly downregulated in the brain tissue of ICH + DM mice and in HG + hemin-induced BV2 cells compared with the control group (Figure 5D), indicating that the expression of miR-129-5p was decreased after injury, and an increase in its expression facilitated the repair of the body after injury. Therefore, after analyzing the experimental results and combining them with existing literature, it was conclusively determined that the miRNA potentially regulating neuroinflammation and nerve function in BMSC-exo was miR-129-5p. Next, we verified the function of miR-129-5p in BMSC-exo.

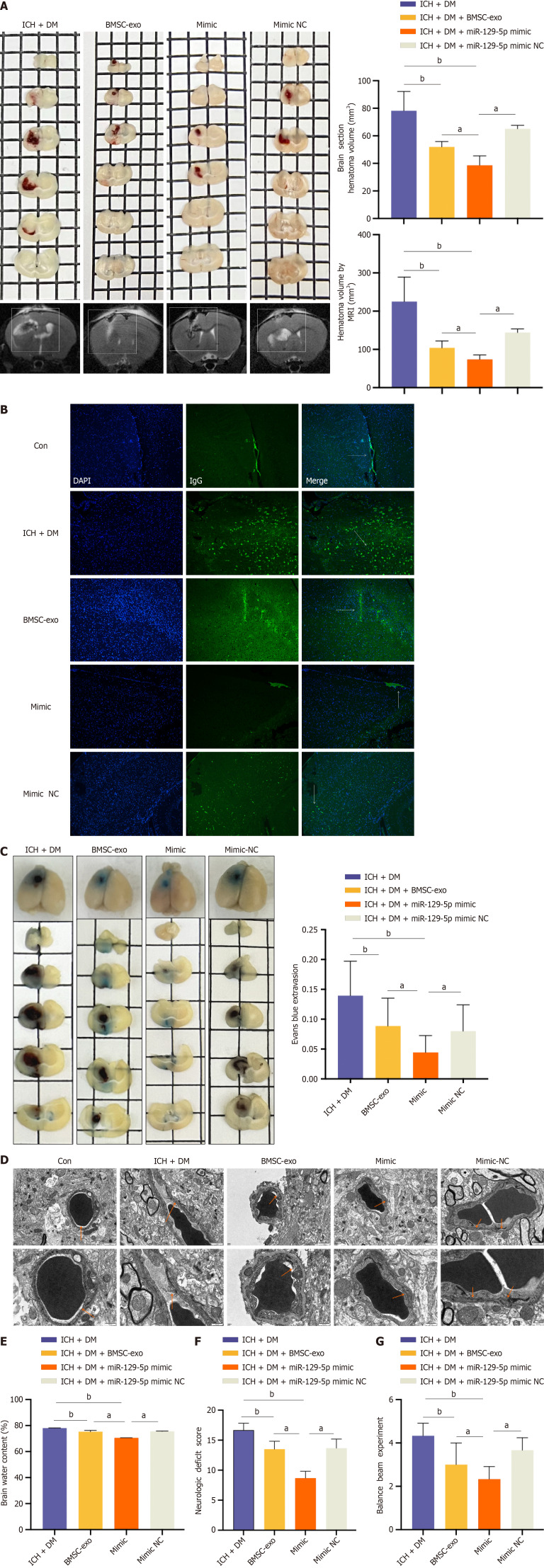

Overexpression of miR-129-5p attenuated neurological deficits after ICH in DM mice

We injected BMSC-exo loaded with overexpressed miR-129-5p (miR-129-5p mimic) into mice (the identification of BMSC-exo loaded with miR-129-5p is shown in Supplementary Figure 1). The results revealed that the cerebral hematoma volume was significantly reduced in the miR-129-5p mimic group compared with the ICH + DM group (Figure 6A). Immunofluorescence detection of IgG revealed distinct patterns. IgG was predominantly confined to the blood vessels in the control group. In the ICH + DM group, most IgG diffused through the blood vessels into the brain parenchyma. Administration of BMSC-exo mitigated this diffusion, resulting in partial IgG protein expression in the blood vessels and brain parenchyma. In comparison, the miR-129-5p mimic group exhibited significantly reduced diffusion of IgG, indicating that heightened miR-129-5p expression could effectively reduce blood-brain barrier damage and permeability (Figure 6B). The same result was obtained in the Evans blue experiment (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of microRNA-129-5p attenuated neurological deficits after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice with diabetes. A: Brain sections and T2 magnetic resonance imaging to detect intracerebral hematoma volume in mice. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) + diabetes mellitus (DM) + bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic negative control (NC) group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group, t-test; B: Immunofluorescence staining to detect the location of immunoglobulin G protein expression; C: Evans blue detection of blood-brain barrier damage. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic NC group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group, t-test; D: Transmission electron microscopic observation of blood-brain barrier damage; E: Dry and wet weight method to measure edema after cerebral hemorrhage in mice. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic NC group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group, t-test; F and G: Neurological score and balance beam test to detect the neurological function of mice after cerebral hemorrhage. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic NC group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group, t-test. DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage; BMSC-exo: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes; NC: Negative control.

Transmission electron microscopy results showed disruption of endothelial cell tight junctions after DM cerebral hemorrhage. Overexpression of miR-129-5p significantly reduced endothelial cell damage (Figure 6D). Moreover, after overexpression of miR-129-5p, the brain water content was markedly reduced compared with that of the ICH + DM group (Figure 6E). Finally, assessment of neurological deficit scores in each group of mice, coupled with measurements of the balance beam scores, revealed a significant improvement in neurological function within the miR-129-5p mimic group (Figure 6F and G). Therefore, the above results demonstrated that BMSC-exo attenuated neurological impairments in DM mice with cerebral hemorrhage by loading an overexpression of miR-129-5p.

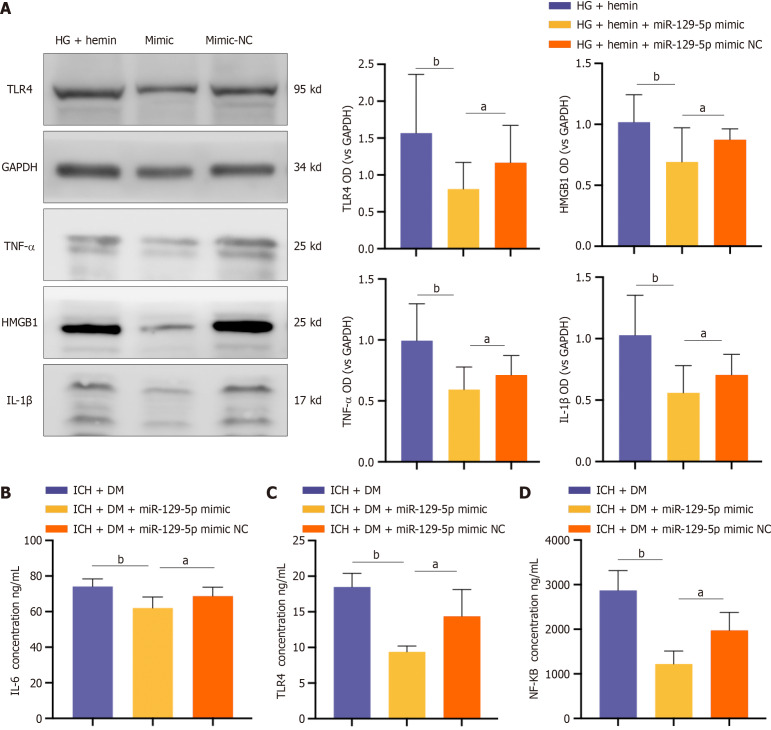

BMSC-exo loading overexpression of miR-129-5p attenuated neuroinflammation after ICH in DM mice

BV2 cells were treated with BMSC-exo loaded with miR-129-5p mimic. Western blot results showed that the expression of the inflammatory factors IL-1β, TLR4, HMGB1, and TNF-α were significantly decreased in the miR-129-5p mimic group compared with that of the HG + hemin group (Figure 7A). At the same time, we used ELISA to detect the expression levels of the inflammatory factors TLR4, IL-6, and NF-κB in mice, and the results similarly showed that the levels of inflammatory factors in the miR-129-5p mimic group were significantly lower than those in the other groups (Figure 7B-D). It indicated that BMSC-exo attenuated neuroinflammation after cerebral hemorrhage in DM mice by loading overexpression of miR-129-5p.

Figure 7.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome overexpression of microRNA-129-5p attenuated neuro-inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice with diabetes. A: The expression of some inflammatory factors [toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and interleukin (IL)-1β] in BV2 cells was detected by western blot. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, high glucose (HG) + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic negative control (NC) group, t-test; bP < 0.01, HG + hemin group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group; B-D: Levels of inflammatory factors TLR4, IL-6, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) + diabetes mellitus (DM) + miR-129-5p mimic group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic NC group, t-test; bP < 0.01, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p mimic group. The mimic group in panel A was HG + hemin + microRNA-129-5p mimic; the mimic NC group was HG + hemin + microRNA-129-5p mimic NC. TLR: Toll-like receptor; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; NC: Negative control.

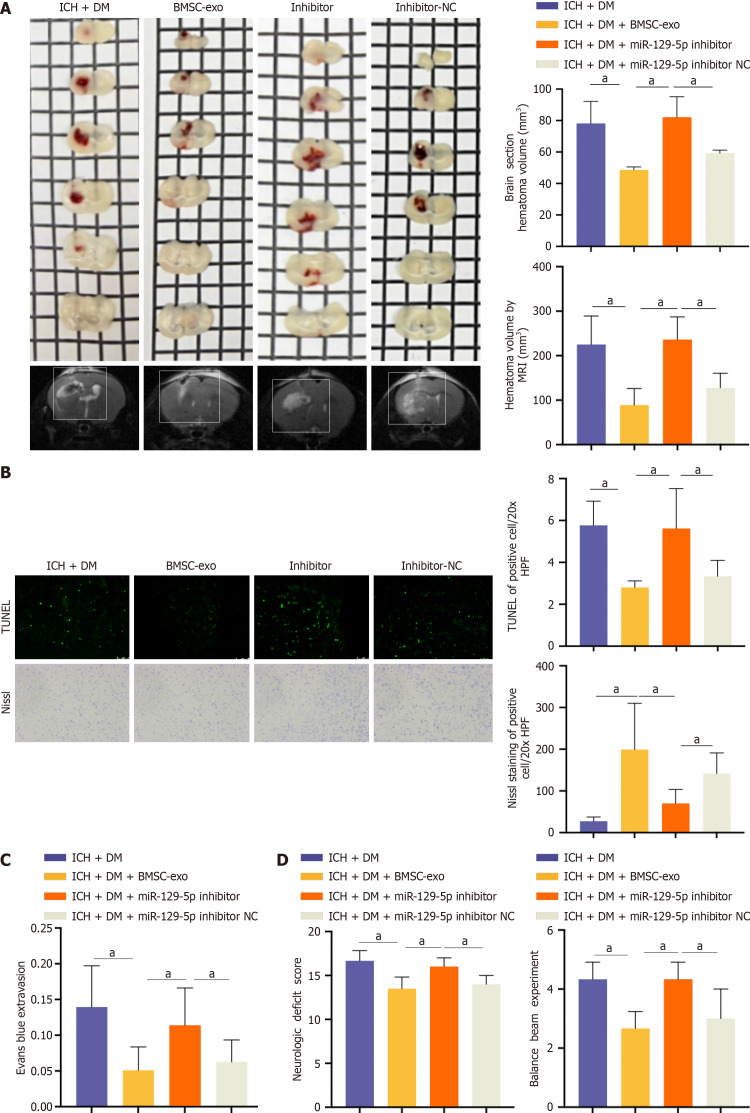

BMSC-exo alleviated neuroinflammation and neurological impairment through miR-129-5p following ICH in DM mice

Compared with the BMSC-exo group, the miR-129-5p inhibitor group had a larger hematoma area (Figure 8A). Upon observing neuronal apoptosis and neuronal activity, we found that neuronal apoptosis was more pronounced and neuronal activity was lower in the miR-129-5p inhibitor group compared to the BMSC-exo group (Figure 8B). The miR-129-5p inhibitor group had a greater severity of blood-brain barrier damage after cerebral hemorrhage compared with the BMSC-exo group (Figure 8C). Finally, neurological function was assessed, and the balance beam test was performed to detect the neurological function of the mice. The neurological function of mice in the miR-129-5p inhibitor group was more severely damaged compared with that of the BMSC-exo group (Figure 8D). This suggested that the inhibition of miR-129-5p attenuated the protective effect of BMSC-exo against neurological impairment in DM mice following ICH. Additionally, it indicated that BMSC-exo exerted a protective effect on the organism through the action of miR-129-5p.

Figure 8.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome alleviated neuroinflammation and neurological impairment through microRNA-129-5p following intracerebral hemorrhage in mice with diabetes. A: The volume of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) detected by magnetic resonance imaging in mice. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + diabetes mellitus (DM) group vs ICH + DM + bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor negative control (NC) group, t-test; B: Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling and Nissl staining were used to detect neuronal apoptosis and activity. Scale = 50 μm. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC group, t-test; C: Blood-brain barrier injury was detected by Evans blue. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC group, t-test; D: Nervous system score and balance beam test were used to detect the neurological function of the mice after ICH. The experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, ICH + DM group vs ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC group, t-test. BMSC-exo: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome; NC: Negative control; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage.

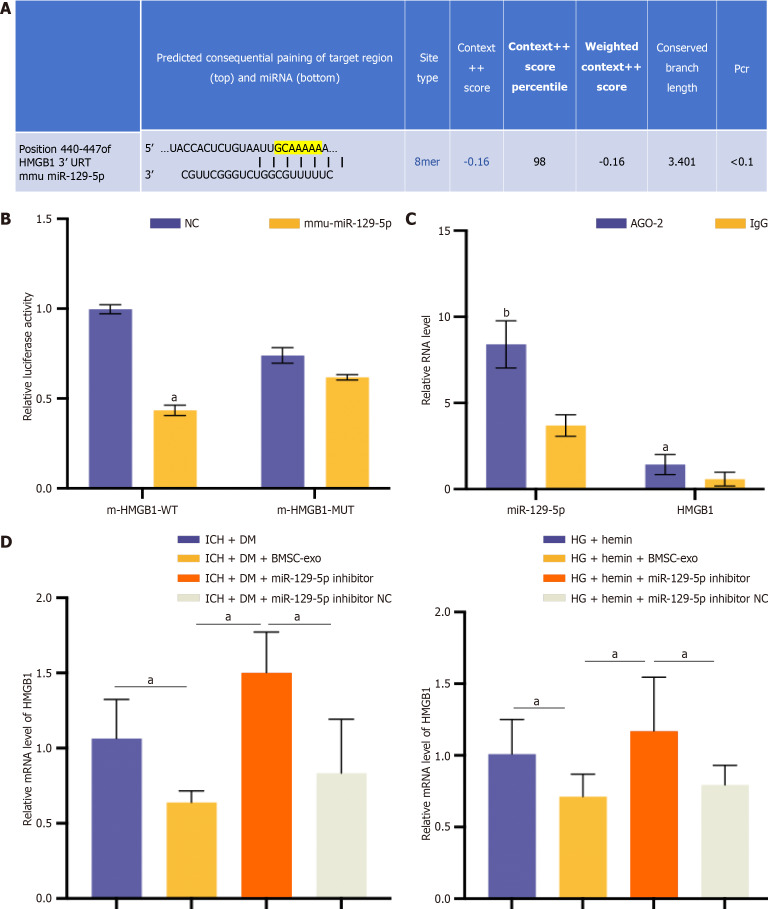

MiR-129-5p targeted and regulated HMGB1 expression

Further evidence of the targeting relationship between miR-129-5p and HMGB1 was obtained. The Targetscan database (http://www.targetscan.org/) had predicted the presence of a binding site between miR-129-5p and HMGB1 (Figure 9A). The dual luciferase reporter gene assay verified the target relationship between miR-129-5p and HMGB1. The results showed that miR-129-5p significantly inhibited the activity of HMGB1, but no evident inhibitory effect was observed after the mutation of the miR-129-5p binding site in HMGB1 (Figure 9B). According to the results of the RIP assay, both miR-129-5p and HMGB1 can bind to the AGO2 protein, indicating that miR-129-5p could bind to AGO2 protein and thus inhibit HMGB1 expression (Figure 9C). The relationship between HMGB1 and miR-129-5p was further verified in vivo and in vitro. qPCR results showed that the expression of HMGB1 was significantly reduced after BMSC-exo intervention compared with the ICH + DM/HG + hemin group, and HMGB1 expression was elevated in the miR-129-5p inhibitor group compared with the BMSC-exo group (Figure 9D). These results suggest that the inhibition of miR-129-5p could increase HMGB1 expression.

Figure 9.

MicroRNA-129-5p targeted and regulated high mobility group box 1 expression. A: Bioinformatic analysis of binding sites of microRNA (miR-129-5p) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) 3’ untranslated region; B: A dual luciferase reporter gene assay was used to verify the specific binding of miR-129-5p and HMGB1. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, negative control (NC) group vs mmu-miR-129-5p group, t-test; C: RNA binding protein immunoprecipitation assay verified the specific binding of miR-129-5p and HMGB1. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, AGO-2 vs immunoglobulin G (IgG) (HMGB1 group); bP < 0.01, AGO-2 vs IgG (miR-129-5p group), t-test; D: The expression of HMGB1 was detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in vitro and in vivo, and the experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. In vivo: aP < 0.05, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) + diabetes mellitus (DM) group vs ICH + DM + bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-exo) group; aP < 0.05, ICH +DM + BMSC-exo group vs ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, ICH + DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs ICH +DM + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC group, t-test. In vitro: aP < 0.05, high glucose (HG) + hemin group vs HG + hemin + BMSC-exo group; aP < 0.05, HG + hemin + BMSC-exo group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p inhibitor group; aP < 0.05, HG + hemin + miR-129-5p inhibitor group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p inhibitor NC group, t-test. BMSC-exo: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes; HG: High glucose; NC: Negative control; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ICH: Intracerebral hemorrhage; IgG: Immunoglobulin G.

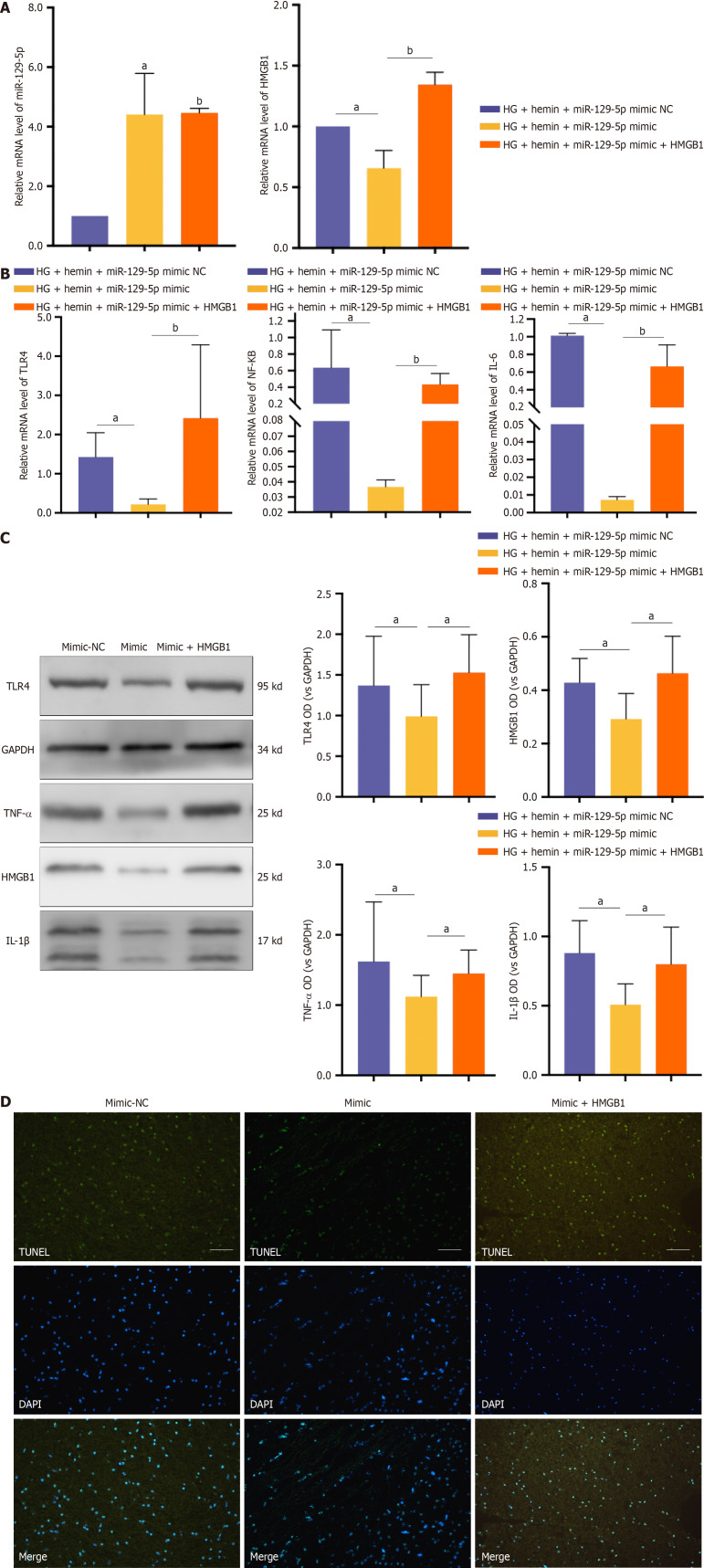

BMSC-exo attenuated neuroinflammation after ICH in DM mice by targeting the expression of HMGB1 in microglia through miR-129-5p

We treated microglia with BMSC-exo loaded with miR-129-5p mimic and HG + hemin while transfecting HMGB1 to overexpress HMGB1. BMSC-exo loaded with miR-129-5p mimic increased the expression of miR-129-5p and inhibited the expression of HMGB1. The effect of miR-129-5p mimic in BMSC-exo was reversed after transfection of HMGB1 (Figure 10A). Meanwhile, BMSC-exo loaded with miR-129-5p mimic reduced the expression level of inflammatory factors (Figure 10B and C) and inhibited cell apoptosis (Figure 10D). The beneficial effects of miR-129-5p mimic on microglia were reversed after HMGB1 overexpression. The above experimental results indicated that BMSC-exo combined with miR-129-5p reduced neuroinflammation after DM complicated with cerebral hemorrhage via modulating the expression of HMGB1.

Figure 10.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome attenuated neuroinflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice with diabetes by targeting the expression of high-mobility group box 1 in microglia through microRNA-129-5p. A: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction detected the expression levels of miR-129-5p and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). The experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, high glucose (HG) + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic negative control (NC) group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group; bP < 0.01, HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic + HMGB1 group, t-test; B: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction detected the expression levels of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), interleukin (IL) 6, and toll-like receptor 4 inflammatory factors. The experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.01, HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic NC group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group; bP < 0.001, HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic + HMGB1 group, t-test; C: Western blot detected the expression level of inflammatory factors, and the experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. aP < 0.05, HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic NC group vs HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic group, t-test; D: Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling of neuronal apoptosis. The mimic NC group was HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic NC, the mimic group was HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic, and the mimic + HMGB1 group was HG + hemin + miR-129-5p mimic + HMGB1 in Panels B and D. HG: High glucose; NC: Negative control; HMGB1: High-mobility group box 1; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; IL: Interleukin; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

DISCUSSION

Many studies on the pathogenesis and treatment of comorbid ICH and DM have shown that nerve injury plays a vital role in the pathological process of ICH in the background of DM. In this study, we innovatively substantiated that BMSC-exo can alleviate ICH in DM mice by reducing an inflammatory response and neurological impairment. These findings suggested that BMSC-exo might be a new remedy for treating ICH in patients with DM.

Recently, cell-based therapies have been shown to be effective in treating cerebral hemorrhage. MSCs are a class of multifunctional stem cells with a high self-renewal capacity that has been widely studied. Numerous studies have demonstrated that MSCs are safe and effective in treating various diseases. Despite the availability of multiple sources of MSCs, bone marrow remains the primary source[6]. Since the source of MSCs significantly influences their therapeutic potential, it is crucial to consider the tissue source of MSCs as an essential factor in improving their therapeutic efficacy. BMSCs are more suitable for the treatment of neurological diseases such as brain and spinal cord injuries, adipose-derived MSCs are appropriate for the treatment of skin regeneration, and umbilical cord-derived MSCs are ideal for the treatment of respiratory diseases[5]. BMSCs promote functional recovery after traumatic brain injury in rats by promoting endogenous angiogenesis and neurogenesis to attenuate the inflammatory response[11]. Therefore, in this study, we selected BMSCs to treat ICH in mice with DM.

The therapeutic effect of MSCs is most likely attributable to their secretory capacity. Exo derived from MSCs can participate in intercellular communication by encapsulating and transferring many functional factors (including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and miRNAs)[30]. There is increasing evidence that BMSC-exo have protective effects against various injury-related diseases, such as liver injury, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, and neurological injury[31-34]. In diseases affecting the locomotor system, BMSC-exo have been found to promote tendon-bone healing via the miR-21-5p/SMAD7 pathway, and exo secreted from BMSCs, stimulated by hypoxia in rats, promoted the healing of grafted tendon-bone tunnels in an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction model[35,36]. In neurological disorders, BMSC-exo can be taken up by neurons, astrocytes, and microglial cells, promoting the recovery of neurological function[30].

We explored methods for mitigating neuroinflammation and functional impairments. We accomplished this by leveraging the advantages of BMSC-exo, including safety, a broad range of drug-carrying capabilities, and the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. We extracted BMSC-exo by culturing primary BMSCs, collecting the cell supernatant, and injecting exo labeled with red fluorescein into mice with DM and ICH via the tail vein. There are many ways that BMSC-exo can be delivered in animal experiments, including oral administration, intravenous injection, and intraperitoneal injections. Among these, intravenous injection is the most employed method for delivering BMSC-exo. Studies have demonstrated that intravenous administration of exo is more effective than intraperitoneal injection in reducing proinflammatory factors in serum[37]. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated the phagocytosis of BMSC-exo by microglia in the brain tissue. We found that microglia could recognize and ingest most of the BMSC-exo. In addition, we observed attenuation of neurological impairment and neuroinflammatory responses after ICH in DM mice.

Exo contain many types of RNAs, including circular RNAs, long noncoding RNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs. While miRNAs can regulate the silencing of post-transcriptional gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, they also participate in various biological activities[38]. miRNA may be one of the main functional components within exo, and this area of study has increased recently[11]. Exo-loaded miRNAs play essential roles in the treatment of various diseases[39], such as traumatic brain injury, myocardial infarction, lung injury, and spinal cord injury[40].

A previous study demonstrated that BMSC-exo could improve myocardial ischemia by inhibiting cardiomyocyte apoptosis via miR-125b-5p. As a new drug carrier, exo could improve the specificity of drug delivery in ischemic diseases[41]. Another study showed that after cerebral hemorrhage, miRNA-21-loaded BMSC-exo promoted the recovery of disease function[10]. In this study, we explored the mechanisms by which exo attenuate neuroinflammation and neurological impairment and searched for miRNAs in exo that exert neuroprotective effects. Through sequencing BMSC-exo, we identified the presence of more than 3000 miRNAs. We summarized the top 100 miRNAs in BMSC-exo. We combined the literature findings and experimental data to select miR-129-5p as our target miRNA. We found that overexpression of miR-129-5p significantly reduced the expression of inflammatory factors and reduced neurological impairment in DM mice with ICH.

The role of miRNAs in neuroinflammation is closely related to the activity of their target genes. Thus, investigating this relationship can provide insights into the disease mechanism. In the current study, we performed bioinformatic prediction through Targetscan and a luciferase reporter assay, which revealed that HMGB1 was a target of miR-129-5p. Before being released into the extracellular environment, HMGB1 can bind to the cell surface via receptors such as RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4. Subsequently, NF-κB signaling is activated, which ultimately promotes the production of various cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6[42]. Elevated expression levels of these inflammatory factors contribute to astrocyte proliferation and neutrophil recruitment around hematomas, thereby leading to blood-brain barrier damage[43], traumatic brain injury[44], and neurodegenerative diseases[45-48].

Treatment targeting HMGB1 can attenuate tissue damage due to the inflammatory response[49]. In this work, the expression of HMGB1 was significantly increased in mice brains after DM with ICH. Silencing of HMGB1 could reduce the expression of inflammatory factors (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, in vitro experiments revealed a decrease in HMGB1 levels associated with BMSC-exo loaded with overexpression of miR-129-5p. Our experimental results confirmed that BMSC-exo attenuated neuroinflammation and brain damage after ICH in DM mice by targeting and regulating the expression of HMGB1 through the loading of miR-129-5p. This cell-free approach based on BMSC-exo has excellent potential as an effective and safe therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ICH in patients with DM. It may facilitate the clinical application of exo-based therapy in this disease.

CONCLUSION

We used bioinformatics, cell biology, and molecular biology approaches to investigate the role of BMSC-exo in neuroinflammation both in vivo and in vitro through the miRNA-129-5p/Hmgb1 axis. The experimental results confirmed that BMSC-exo attenuated neuroinflammation and brain damage after ICH in DM mice by targeting and regulating the expression of HMGB1 through the loading of miR-129-5p. In brief, this cell-free method based on BMSC-exo has great potential as an effective and safe treatment for ICH in patients with DM and may promote the clinical application of extracellular vesicle-based therapies in diseases of the nervous system.

Footnotes

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All animal experiments were conducted following the national guidelines and the relevant national laws on the protection of animals and were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harbin Medical University (Approval No. 2022016).

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Cai L; Grabovskis A; Weston R S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L

Contributor Information

Yue-Ying Wang, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Ke Li, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Jia-Jun Wang, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Wei Hua, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Qi Liu, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Yu-Lan Sun, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Ji-Ping Qi, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Yue-Jia Song, Department of Endocrinology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China. songyuejia@126.com.

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available by request (songyuejia@hrbmu.edu.cn).

References

- 1.Chen S, Wan Y, Guo H, Shen J, Li M, Xia Y, Zhang L, Sun Z, Chen X, Li G, He Q, Hu B. Diabetic and stress-induced hyperglycemia in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A multicenter prospective cohort (CHEERY) study. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023;29:979–987. doi: 10.1111/cns.14033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren H, Han R, Chen X, Liu X, Wan J, Wang L, Yang X, Wang J. Potential therapeutic targets for intracerebral hemorrhage-associated inflammation: An update. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40:1752–1768. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20923551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gómez-de Frutos MC, Laso-García F, García-Suárez I, Piniella D, Otero-Ortega L, Alonso-López E, Pozo-Novoa J, Gallego-Ruiz R, Díaz-Gamero N, Fuentes B, Alonso de Leciñana M, Díez-Tejedor E, Ruiz-Ares G, Gutiérrez-Fernández M. The impact of experimental diabetes on intracerebral haemorrhage. A preclinical study. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;176:116834. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Yang QW, Wang J. Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:420–433. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoang DM, Pham PT, Bach TQ, Ngo ATL, Nguyen QT, Phan TTK, Nguyen GH, Le PTT, Hoang VT, Forsyth NR, Heke M, Nguyen LT. Stem cell-based therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:272. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01134-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao C, Lei M, Hu W, Han S, Wang Q. A brief review: the therapeutic potential of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:242. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0697-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, Liang Z, Wang F, Zhou C, Zheng X, Hu T, He X, Wu X, Lan P. Exosomes from mesenchymal stromal cells reduce murine colonic inflammation via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuo R, Liu M, Wang Y, Li J, Wang W, Wu J, Sun C, Li B, Wang Z, Lan W, Zhang C, Shi C, Zhou Y. BM-MSC-derived exosomes alleviate radiation-induced bone loss by restoring the function of recipient BM-MSCs and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ZX, He D, Mo QW, Xie LP, Liang JR, Liu L, Fu WJ. MiR-129-5p protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via targeting HMGB1. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:4440–4450. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Wang Y, Lv Q, Gao J, Hu L, He Z. MicroRNA-21 Overexpression Promotes the Neuroprotective Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2018;9:931. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, Xiong Y. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:856–867. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Wang B, Guo Q. MiR-26b-5p-modified hUB-MSCs derived exosomes attenuate early brain injury during subarachnoid hemorrhage via MAT2A-mediated the p38 MAPK/STAT3 signaling pathway. Brain Res Bull. 2021;175:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Zhang D, Fu X, Yu L, Lu Z, Gao Y, Liu X, Man J, Li S, Li N, Chen X, Hong M, Yang Q, Wang J. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-3 protects against ischemic stroke by suppressing neuroinflammation and alleviating blood-brain barrier disruption. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:188. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Li Q, Gao Y, Cheng T, Wan J, Zhu W, Wang J. Pinocembrin protects hemorrhagic brain primarily by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 and reducing M1 phenotype microglia. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;61:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voet S, Prinz M, van Loo G. Microglia in Central Nervous System Inflammation and Multiple Sclerosis Pathology. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Lan X, Han X, Wang J. Expression of Tmem119/Sall1 and Ccr2/CD69 in FACS-Sorted Microglia- and Monocyte/Macrophage-Enriched Cell Populations After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:520. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Li Y, Shi J, Zhu L, Dai Y, Fu P, Liu S, Hong M, Zhang J, Wang J, Jiang C. Lymphocyte-Related Immunomodulatory Therapy with Siponimod (BAF-312) Improves Outcomes in Mice with Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Aging Dis. 2023;14:966–991. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Wang J. (-)-Epicatechin, a Natural Flavonoid Compound, Protects Astrocytes Against Hemoglobin Toxicity via Nrf2 and AP-1 Signaling Pathways. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:7898–7907. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0271-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CF, Cai L, Wang J. Translational intracerebral hemorrhage: a need for transparent descriptions of fresh tissue sampling and preclinical model quality. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:384–389. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Li Q, Wang Z, Qi C, Han X, Lan X, Wan J, Wang W, Zhao X, Hou Z, Gao C, Carhuapoma JR, Mori S, Zhang J, Wang J. Multimodality MRI assessment of grey and white matter injury and blood-brain barrier disruption after intracerebral haemorrhage in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40358. doi: 10.1038/srep40358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Zhuang H, Doré S. Heme oxygenase 2 is neuroprotective against intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G, Manaenko A, Shao A, Ou Y, Yang P, Budbazar E, Nowrangi D, Zhang JH, Tang J. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 facilitates heme scavenging after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:1299–1310. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16654494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Tsirka SE. Tuftsin fragment 1-3 is beneficial when delivered after the induction of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:613–618. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155729.12931.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qinlin F, Bingqiao W, Linlin H, Peixia S, Lexing X, Lijun Y, Qingwu Y. miR-129-5p targets FEZ1/SCOC/ULK1/NBR1 complex to restore neuronal function in mice with post-stroke depression. Bioengineered. 2022;13:9708–9728. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2059910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Expression of concern: Effect of microRNA-129-5p targeting HMGB1-RAGE signaling pathway on revascularization in a collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage rat model [Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 93 (2017) 238-244] Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113826. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statement of Retraction: MicroRNA-129-5p alleviates nerve injury and inflammatory response of Alzheimer's disease via downregulating SOX6. Cell Cycle. 2022;21:1347. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2022.2046811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li XQ, Chen FS, Tan WF, Fang B, Zhang ZL, Ma H. Elevated microRNA-129-5p level ameliorates neuroinflammation and blood-spinal cord barrier damage after ischemia-reperfusion by inhibiting HMGB1 and the TLR3-cytokine pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:205. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0977-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Zhao S, Li G, Wang D, Jin Y. Neuroprotective Effect of HOTAIR Silencing on Isoflurane-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction via Sponging microRNA-129-5p and Inhibiting Neuroinflammation. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2022;29:369–379. doi: 10.1159/000521014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobricic V, Schilling M, Schulz J, Zhu LS, Zhou CW, Fuß J, Franzenburg S, Zhu LQ, Parkkinen L, Lill CM, Bertram L. Differential microRNA expression analyses across two brain regions in Alzheimer's disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:352. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xin H, Li Y, Liu Z, Wang X, Shang X, Cui Y, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. MiR-133b promotes neural plasticity and functional recovery after treatment of stroke with multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in rats via transfer of exosome-enriched extracellular particles. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2737–2746. doi: 10.1002/stem.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, Chen TS, Salto-Tellez M, Timmers L, Lee CN, El Oakley RM, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP, Lim SK. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Rivero Vaccari JP, Brand F 3rd, Adamczak S, Lee SW, Perez-Barcena J, Wang MY, Bullock MR, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. Exosome-mediated inflammasome signaling after central nervous system injury. J Neurochem. 2016;136 Suppl 1:39–48. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phinney DG, Pittenger MF. Concise Review: MSC-Derived Exosomes for Cell-Free Therapy. Stem Cells. 2017;35:851–858. doi: 10.1002/stem.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang ZG, Buller B, Chopp M. Exosomes - beyond stem cells for restorative therapy in stroke and neurological injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:193–203. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu XD, Kang L, Tian J, Wu Y, Huang Y, Liu J, Wang H, Qiu G, Wu Z. Exosomes derived from magnetically actuated bone mesenchymal stem cells promote tendon-bone healing through the miR-21-5p/SMAD7 pathway. Mater Today Bio. 2022;15:100319. doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, Yan S, Song Y, Chen C, Xu D, Lu B, Xu Y. Exosomes secreted by hypoxia-stimulated bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote grafted tendon-bone tunnel healing in rat anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction model. J Orthop Translat. 2022;36:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2022.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S, Li H, Zhangdi H, Xu R, Zhang X, Liu J, Hu Y, Ning D, Jin S. Hair follicle-MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles as a novel remedy for acute pancreatitis. J Control Release. 2022;352:1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papoutsidakis N, Deftereos S, Kaoukis A, Bouras G, Giannopoulos G, Theodorakis A, Angelidis C, Hatzis G, Stefanadis C. MicroRNAs and the heart: small things do matter. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:216–230. doi: 10.2174/1568026611313020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakashima M, Suga N, Ikeda Y, Yoshikawa S, Matsuda S. Relevant MicroRNAs of MMPs and TIMPs with Certain Gut Microbiota Could Be Involved in the Invasiveness and Metastasis of Malignant Tumors. Innov Discov. 2024;1:10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan L, Shi E, Jiang X, Shi J, Gao S, Liu H. Inhibition of MicroRNA-204 Conducts Neuroprotection Against Spinal Cord Ischemia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q, Huang J, Hu J, Zhu H. Advance in spinal cord ischemia reperfusion injury: Blood-spinal cord barrier and remote ischemic preconditioning. Life Sci. 2016;154:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu LP, Tian T, Wang JY, He JN, Chen T, Pan M, Xu L, Zhang HX, Qiu XT, Li CC, Wang KK, Shen H, Zhang GG, Bai YP. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics. 2018;8:6163–6177. doi: 10.7150/thno.28021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su X, Wang H, Zhao J, Pan H, Mao L. Beneficial effects of ethyl pyruvate through inhibiting high-mobility group box 1 expression and TLR4/NF-κB pathway after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011:807142. doi: 10.1155/2011/807142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang C, Guo H, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Liu S, Lai J, Wang TJ, Li S, Zhang J, Zhu L, Fu P, Zhang J, Wang J. Molecular, Pathological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Aspects of Perihematomal Edema in Different Stages of Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3948921. doi: 10.1155/2022/3948921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin D, Wang J, Le A, Wang TJ, Chen X, Wang J. Traumatic Brain Injury: Ultrastructural Features in Neuronal Ferroptosis, Glial Cell Activation and Polarization, and Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown. Cells. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/cells10051009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minghetti L. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:901–910. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giulian D, Lachman LB. Interleukin-1 stimulation of astroglial proliferation after brain injury. Science. 1985;228:497–499. doi: 10.1126/science.3872478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allan SM, Tyrrell PJ, Rothwell NJ. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:629–640. doi: 10.1038/nri1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao N, Zhang J, Chen C, Wan Y, Wang N, Yang J. miR-129-5p improves cardiac function in rats with chronic heart failure through targeting HMGB1. Mamm Genome. 2019;30:276–288. doi: 10.1007/s00335-019-09817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available by request (songyuejia@hrbmu.edu.cn).