Abstract

Aims and background

Emergency nurses are working in a stress-prone environment. It is critical to ensure adequate psychological aids to cope with the distress at work. The objective of this systematic review was to explore and evaluate the studies that have discussed the role of mindfulness-based interventions on occupational distress and resilience among emergency nursing professionals.

Materials and methods

This study was a systematic review. The databases used for this review were PubMed and Scopus from 2018 to 2023. Interventional studies published in English that used mindfulness-based techniques among emergency and critical care nurses to alleviate their occupational distress and burnout and improve resilience were considered for review. This systematic review adheres to the PRISMA guidelines. The study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024512071).

Results

Ten studies were found to be eligible and included in this review. Out of the 10 studies included, nine studies demonstrated the improvement of psychological well-being, compassion, and resilience followed by the intervention.

Conclusion

The findings of this systematic review suggest that mindfulness-centered interventions can be an effective strategy to cope with distress and burnout and in building compassion and resilience among the healthcare professionals who are employed at the emergency and critical care department in a hospital.

Clinical significance

Incorporating mindfulness-based practices and interventions in healthcare settings, especially among critical care and emergency departments may help in ameliorating the professional well-being of the staff which may result in a resilient work environment and improvement in the quality of patient care.

How to cite this article

Joseph A, Jose TP. Coping with Distress and Building Resilience among Emergency Nurses: A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-based Interventions. Indian J Crit Care Med 2024;28(8):785–791.

Keywords: Critical care nursing, Emergency nurses, Mindfulness-based interventions, Occupational distress, Resilience, Stress, Systematic review

Highlights

Mindfulness-based interventions are effective in dealing with occupational distress and burnout among emergency and critical care nursing professionals.

Incorporating mindfulness-based practices at the workplace may help in improving self-care and building resilience among the personnel working in emergency or critical care.

Introduction

Emergency nursing professionals are the first responders employed in the healthcare setting for the optimization of the treatment and medical care of the patients in the Emergency Department and trauma care. Emergency nurses, as they are dealing with patients with acute trauma and pain as well as their heavy workload make them more stressful resulting in burnout and occupational distress.1 Emergency nurses are exposed to a more stressful work environment and are more prone to mental health problems such as distress and mental fatigue than a general nursing population.2 Several factors such as lack of adequate sleep, shift work intolerance, regular exposure to extreme traumatic events such as acute wounds of patients, death of patients, conflict with physicians, etc.3 are the major causes of occupational distress and burnout among nurses. Healthcare workers’ personal and professional well-being is critical in building resilient healthcare systems. This is because the optimization of treatment as well as patient care depends on them. As emergency and critical care nurses are working in highly stress-prone environment, they develop occupational distress along with an increased turnover intention.4

Mindfulness-based stress reduction is a psycho-therapeutic approach which is focused on meditation and which was developed to alleviate the stress among the individuals.5 Studies conducted across different populations revealed that stress can be reduced and emotions can be regulated in a positive way by means of mindfulness-based stress reduction.6 Because of the potential mental health benefit of this therapeutic approach, it is being widely used to regulate and reduce stress. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is another major therapeutic approach which incorporates the elements of mindfulness-based techniques with cognitive behavior therapy.7 Mindfulness-based interventions are being used as an effective aid to mitigate distress and improve self-care.8

In the past 5 years, there has been a rising trend in the incorporation of mindfulness-based techniques to promote mental health and reduce burnout among emergency as well as critical care personnel.9 Maintaining work–life balance while working in a stress-prone environment is very much challenging, especially for those who are first responders employed in emergency departments. Some studies have shown that mindfulness training has improved well-being at the workplace.10

The present study aimed to analyze as well as synthesize the findings of the most relevant research papers that have explained the role of mindfulness-based interventions in alleviating the mental fatigue, stress as well as burnout among emergency nursing professionals.

Materials and Methods

The structuring of this article was done in accordance with the PRISMA reporting guidelines 2020.11 The study was registered under PROSPERO (CRD42024512071).

Data Retrieval

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the existing literature of the past 5 years from 2018 to 2023 was conducted using electronic databases such as PubMed and Scopus. The search was done in January 2024. Only the studies which were published in English were considered for the review. We used the following search terms such as “Emergency Nurse” AND distress, “Emergency nurse” AND burnout, Nurses AND Mindfulness, “Emergency nurses” AND Mindfulness, Mindfulness AND distress AND nurses, “Emergency nurses” AND Resilience, to locate the relevant research studies, related to the area of mindfulness, Distress as well as resilience among the emergency nurses. The searches were carried out using the Population, Intervention, Context, and outcome (PICO) framework.12

Study Selection

Studies which are selected for this review research were under the following criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Only included the studies that investigated the effect of mindfulness-based intervention among nurses in emergency or critical care departments in a hospital setting.

Studies which used randomized control trial (RCT) or quasi-experimental design.

The studies which reported the results in quantitative or qualitative way to assess the effect of the intervention on distress, burnout, and resilience among emergency nurses.

Studies published in English language.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies have not been conducted among nurses working in emergency department.

Studies not using mindfulness-based interventions.

Studies not in the English language.

Literature reviews, Book reviews, case studies, and commentary

Articles from non-SCOPUS Journals.

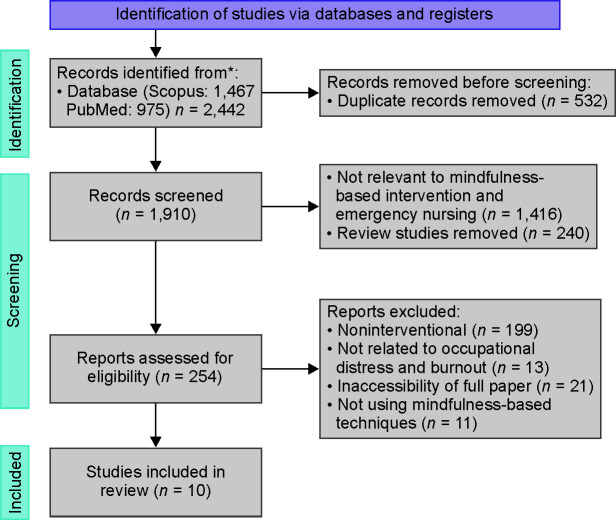

The PRISMA flow diagram which shows the systematic screening of the research papers which were relevant to the current research is depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram showing the selection and screening process of the eligible research for the review as per the PRISMA guidelines

*Records are identified from the respective database using the significant key terms relevant to the research

The initial search using the key terms resulted in 2,442 studies. After removing the duplicates there were 1,910 research articles. Out of these, 1,656 studies were excluded because of the incongruence with the eligibility criteria. The remaining 254 studies were again screened and extensively reviewed, after the exclusion of the ineligible research papers there were ultimately 10 studies which are included in this review.

Analysis of Data

Titles as well as abstracts of the relevant research articles found were screened and analyzed independently by the two authors of this research. Discrepancies that aroused were figured out and resolved by means of consensus. Assessment of the full text was carried out only for those articles which were potentially significant.

Data were analyzed as well as extracted based on the inclusion as well as exclusion criteria which are mentioned above, It consisted of the study characteristics (Interventional or non-interventional), participants characteristics (nurses who are working in an emergency department), type of intervention (mindfulness-based), outcome measures (distress, burnout, and resilience), as well as key findings that contribute to the well-being of emergency nurses.

Quality Assessment

The reporting as well as methodological quality of the included studies were assessed by both authors using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal checklist for randomized control trial, quasi-experimental trials, and qualitative design.13 The quality assessment tools developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were used to assess the quality of pre- and post studies with no control group. The quality assessment of each study is given in Tables 1 to 4.

Table 1.

Quality appraisal of randomized control studies using JBI checklist

| JBI Critical appraisal Checklist for RCT | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argyriadis et al.14 | Marotta et al.15 | Xu et al.16 | Yıldırım and Yıldız17 | |

| 1. True randomization followed. | + | + | + | + |

| 2. Concealed allocation to treatment group done. | + | + | + | + |

| 3. Treatment groups similar at the baseline. | + | + | + | + |

| 4. Participants are blind to the assignment of treatment group. | + | + | + | + |

| 5. Those who were delivering treatment are blind to assignment of treatment group. | + | + | + | + |

| 6. The outcome assessors are blind to the assignment of treatment group. | + | + | + | + |

| 7. Treatment groups are treated identically other than the desired intervention. | + | + | + | + |

| 8. Follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? | − | − | + | − |

| 9. Participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. | + | + | + | + |

| 10. Outcome measures done in the same way for treatment groups. | + | + | + | + |

| 11. Outcomes are measured in a reliable way. | + | + | + | + |

| 12. Statistical methods used was appropriate. | + | + | + | + |

| 13. Appropriate trial design was used. | + | + | + | + |

‘+’ sign indicates yes and ‘−’ indicates no or not clear

Table 4.

Quality appraisal for qualitative study using JBI checklist

| JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative study | Study |

|---|---|

| Trygg Lycke et al.23 | |

| 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | Yes |

| 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | Yes |

| 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Yes |

| 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Yes |

| 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Yes |

| 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | Yes |

| 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | No |

| 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | Yes |

| 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Yes |

| 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | Yes |

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of quasi-experimental study using JBI checklist

| JBI Critical appraisal checklist for Quasi-experimental study | Study |

|---|---|

| Othman et al.22 | |

| 1. Is it clear in the study what the ‘cause’ is and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | Yes |

| 2. Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | Yes |

| 3. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | Yes |

| 4. Was there a control group? | Yes |

| 5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | Yes |

| 6. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? | No |

| 7. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | Yes |

| 8. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Yes |

| 9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes |

Table 3.

Quality appraisal for pretest posttest interventional studies with no control group using NIH checklist

| NIH checklist for pretest posttest interventional studies | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson18 | Delaney20 | Wong et al.21 | Gracia Gozalo et al.19 | |

| 1. Was the study question or objective clearly stated? | + | + | + | + |

| 2. Were eligibility/selection criteria for the study population pre-specified and clearly described? | + | + | + | + |

| 3. Were the participants in the study representative of those who would be eligible for the test/service/intervention in the general or clinical population of interest? | + | + | + | + |

| 4. Were all eligible participants that met the pre-specified entry criteria enrolled? | + | + | + | + |

| 5. Was the sample size sufficiently large to provide confidence in the findings? | − | − | + | − |

| 6. Was the test/service/intervention clearly described and delivered consistently across the study population? | + | + | + | + |

| 7. Were the outcome measures pre-specified, clearly defined, valid, reliable, and assessed consistently across all study participants? | + | + | + | + |

| 8. Were the people assessing the outcomes blinded to the participants’ exposures/interventions? | + | + | − | − |

| 9. Was the loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? Were those lost to follow-up accounted for in the analysis? | − | − | + | − |

| 10. Did the statistical methods examine changes in outcome measures from before to after the intervention? Were statistical tests done that provided p values for the pre-to-post changes? | + | + | + | + |

| 11. Were outcome measures of interest taken multiple times before the intervention and multiple times after the intervention (i.e., did they use an interrupted time-series design)? | − | − | − | − |

| 12. If the intervention was conducted at a group level (e.g., a whole hospital, a community, etc.) did the statistical analysis take into account the use of individual-level data to determine effects at the group level? | − | + | − | − |

+ Indicates yes, ‘−‘ indicates no or not defined

Results

Study and Participant Characteristics

Out of the included 10 studies, 4 studies followed RCT design.14–17 Four studies followed pre- and post-interventional design.18–21 One study was quasi-experimental,22 and one was qualitative in nature.23

The studies included in this review consisted of a total of 531 participants. All the participants were employed in either the emergency or critical care department as nurses or nursing assistants in a hospital setting. Three of the studies included focused on the frontline nurses who were involved in the care of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patients.22,15,17

Intervention

All the included studies used mindfulness-based interventions adopted from the mindfulness practice developed by Kabat-Zinn.5 Three studies used mindfulness-based stress reduction.18,19,15 Two studies used mindfulness training as the intervention.21,23

Two studies used mindfulness-based intervention (MBI).14,22 The rest of the selected studies used mindfulness- based compassion training,20 mindfulness-based music and breathing therapy17 and smartphone-based mindfulness practice.16

Table 5 shows the study characteristics as well as the major findings of the included studies in the review.

Table 5.

Study characteristics as well as major findings of the included studies in the review

| Author and year | Country | Setting | Sample | Research design | Intervention | Outcome measure | Quality assessment score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson18 | United Kingdom | Critical care | 25 Critical care nurses | Pre- and post-interventional design | MBSR | Perceived stress, Professional quality of life, mindful attention awareness | 8/12 |

| Argyriadis et al.14 | Greece | Hospital emergency department | 14 Emergency Nurses | RCT | MBI | Cognitive functions, Personal satisfaction, Interpersonal relations, Sleep quality. | 12/13 |

| Delaney20 | Ireland | Hospital | 13 Frontline Nurses | Pre- and post-interventional design | MSCT | Self-compassion, resilience, professional quality of life | 9/12 |

| Gracia Gozalo et al.19 | Spain | Hospital intensive care unit | 32 Nurses and nursing assistants in ICU | Pre- and post-interventional design | MBSR | Burnout, empathy self-compassion | 7/12 |

| Marotta et al.15 | Italy | Hospital | 53 Nurse and allied health professionals | RCT | MBSR | Burnout, well-being and Perceived stress | 12/13 |

| Othman et al.22 | Egypt | Hospital critical care | 60 Frontline nurse (COVID) | Quasi-experimental | MBSR | Burnout, Self-compassion | 8/9 |

| Trygg Lyke et al.23 | Sweden | Emergency department | 51 Emergency Nurses | Qualitative | Mindfulness training | Stress level, compassion Empathy, | 9/10 |

| Wong et al.21 | USA | Pediatric emergency department | 83 Pediatric emergency staff | Pre- and post-interventional design | On-shift Mindfulness-based training | Distress and burnout levels | 9/12 |

| Xu et al.16 | Australia | Emergency department | 148 Emergency department nurses and nursing assistants | RCT | Smartphone guided mindfulness practice | Burnout and well-being | 13/13 |

| Yıldırım and Yıldız17 | Turkey | Hospital critical care | 52 Frontline nurses in COVID-19 care | RCT | Mindfulness-based breathing and music therapy | Work stress and strain, anxiety and well-being | 12/13 |

MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; MSCT, mindful self-compassion training; MBI, mindfulness-based intervention; RCT, randomized control trial

Discussion

The studies that we analyzed in this review provide an insight into the possible advantages of mindfulness-based therapies for promoting mental health and well-being of nursing professionals who are working in emergency and critical care departments in a hospital setting.

Among the included studies, nine out of 10 studies reported that mindfulness-based interventions and training are effective in managing burnout, reducing stress as well as negative emotions and improving well-being, self-compassion, empathy and resilience. In addition, These studies also suggest that the mindfulness-based interventions can be administered as concomitant methods such as MBSR, MBI, MSCT, mindfulness training which is guided by a smartphone, mindfulness-based breathing, and music therapy. However, one study showed that there is no significant change or difference in distress and burnout levels pre- and post-mindfulness-based intervention.21

Studies have investigated the effectiveness of mindfulness training on life satisfaction and perceived stress levels in emergency and critical care settings in a hospital suggesting that mindfulness interventions can play a crucial role in identifying the stressors and coping the distress through awareness generated through the intervention.18,15

In addition, Delany,20 Trygg Lycke et al.23 and Gracia Gozalo et al.19 emphasized the significance of mindfulness-based interventions and practices in promoting self-compassion as well as self-awareness among emergency healthcare nurses. These research revealed that mindfulness practices are not only benefitting the psychological well-being of emergency nurses but also have a significant impact on patient care outcomes, improved empathy as well as interpersonal relations.

Studies conducted in the Indian context also signify the higher prevalence of burnout and distress among frontline nurses in the emergency care departments.24,25 In addition, these studies suggest the necessity of incorporating the potential psychological interventions to build resilience among professionals.

The combined results of these researches emphasize the importance of incorporating mindfulness-based practices and interventions in healthcare settings, especially among critical care and emergency departments to address distress, promote well-being, and raise the standard of care given to patients by the staff. This research encompasses the scope of developing mindfulness programs for healthcare workers not only in emergency departments but also in different healthcare environments and investigating the sustainability and long-term impacts of mindfulness interventions in fostering resilience and mental health in healthcare workers. Overall, the outcomes of this research highlight the potential benefit of mindfulness-centered interventions for enhancing emergency nurse's emotional and mental health.

However, it is necessary to address certain limitations that underlie this research and call for further investigation. The heterogeneity of the research designs and outcome measures prevents us from making a precise and definitive generalization and conclusion about the effectiveness of the intervention. Additionally, the small sample size, lack of RCT design, and lack of adequate follow-ups limit the generalization of the effectiveness of the intervention.

Hence, in order to gain further insight into the long-term benefits of mindfulness-centered interventions or therapies and their implications for healthcare practice, prospective studies should concentrate on undertaking more extensive investigations in a larger scale using rigorous methodology.

Conclusion

The systematic review of these studies reveals that mindfulness interventions not only have the potential to alleviate stress and improve psychological outcomes but also contribute to a positive work environment and patient care. By promoting self-awareness, emotional regulation, and self-compassion, mindfulness practices can help healthcare professionals cope with the demands of their roles and enhance their ability to provide compassionate care to patients.

Clinical Significance

Organizations may cultivate a patient-centered, resilient work environment that promotes compassion and resilience of the healthcare employees by establishing a major emphasis on the emotional and physical well-being of healthcare personnel, especially by means of mindfulness-based interventions and training.

PROSPERO Registration

This study was registered under PROSPERO registry with registration number CRD42024512071.

CRediT Authorship Statement

Both authors have equally contributed for this review. Albin Joseph: Writing – Original draft, Data curation, Methodology, investigation, Formal analysis, software. Dr Tony P Jose: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Reviewing and editing.

Orcid

Albin Joseph https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9722-3195

Tony P Jose https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6246-4076

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Adeb-Saeedi J. Stress amongst emergency nurses. Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2002;5(2):19–24. doi: 10.1016/S1328-2743(02)80015-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Van Der Doef M, Maes S. Exploring the burden of emergency care: Predictors of stress-health outcomes in emergency nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(6):1317–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alomari AH, Collison J, Hunt L, Wilson NJ. Stressors for emergency department nurses: Insights from a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(7):975–985. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norful AA, Cato K, Chang BP, Amberson T, Castner J. Emergency nursing workforce, burnout, and job turnover in the united states: A national sample survey analysis. J Emerg Nurs. 2023;49(4):574–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2022.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(6):519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sipe WEB, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):63–69. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer S. Mindfulness-based Interventions: Can they improve self-care and psychological well-being? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26(4):409–410. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein A, Taieb O, Xavier S, Baubet T, Reyre A. The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: A systematic review. Explore. 2020;16(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellor NJ, Ingram L, Van Huizen M, Arnold J, Harding A-H. Mindfulness training and employee well-being. Int J Work Heal Manag. 2016;9(2):126–145. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-11-2014-0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/J.IJSU.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, Klugar M, Tufanaru C, Leonardi-Bee J, et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):494–506. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argyriadis A, Ioannidou L, Dimitrakopoulos I, Gourni M, Ntimeri G, Vlachou C, et al. Experimental mindfulness intervention in an emergency department for stress management and development of positive working environment. Healthc (Basel, Switzerland). Epub ahead of print. 2023;11(6):879. doi: 10.3390/HEALTHCARE11060879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marotta M, Gorini F, Parlanti A, Berti S, Vassalle C. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the well-being, burnout and stress of Italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Med, Epub ahead of print. 2022;11(11) doi: 10.3390/JCM11113136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu HG, Eley R, Kynoch K, Tuckett A. Effects of mobile mindfulness on emergency department work stress: A randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34(2):176–185. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yıldırım D, Yıldız CÇ. The effect of mindfulness-based breathing and music therapy practice on nurses’ stress, work-related strain, and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Holist Nurs Pract. 2022;36(3):156. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson N. An evaluation of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for critical care nursing staff: A quality improvement project. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(6):441–448. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gracia Gozalo RM, Ferrer Tarrés JM, Ayora Ayora A, Alonso Herrero M, Amutio Kareaga A, Ferrer Roca R. Application of a mindfulness program among healthcare professionals in an intensive care unit: Effect on burnout, empathy and self-compassion. Med Intensiva (English Ed) 2019;43(4):207–216. doi: 10.1016/J.MEDINE.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaney MC. Caring for the caregivers: Evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses’ compassion fatigue and resilience. PLoS One, Epub ahead of print. 2018;11(13) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0207261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong KU, Palladino L, Langhan ML. Exploring the effect of mindfulness on burnout in a pediatric emergency department. Workplace Health Saf. 2021;69(10):467–473. doi: 10.1177/21650799211004423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Othman SY, Hassan NI, Mohamed AM. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout and self-compassion among critical care nurses caring for patients with COVID-19: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trygg Lycke S, Airosa F, Lundh L. Emergency department nurses’ experiences of a mindfulness training intervention: A phenomenological exploration. J Holist Nurs. 2023;41(2):170–184. doi: 10.1177/08980101221100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose S, Dhandapani M, Cyriac MC. Burnout and resilience among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in the emergency department of a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;24(11):1081–1088. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunil R, Bhatt MT, Bhumika TV, Thomas N, Puranik A, Chaudhuri S, et al. Weathering the storm: psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on clinical and nonclinical healthcare workers in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(1):16–20. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]