Abstract

BACKGROUND

Breast cancer (BC) is a common cancer among females in Africa. Being infected with BC in Africa seems like a life sentence and brings devastating experiences to patients and households. As a result, BC is comorbid with trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and post-traumatic growth (PTG).

AIM

To identify empirical evidence from peer-reviewed articles on the comorbidity trajectories between BC and trauma, BC and PTSD, and BC and PTG.

METHODS

This review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines of conducting a systematic review. Literature searches of the National Library of Medicine, Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases were conducted using search terms developed for the study. The search hint yielded 769 results, which were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. At the end of the screening, 24 articles were included in the systematic review.

RESULTS

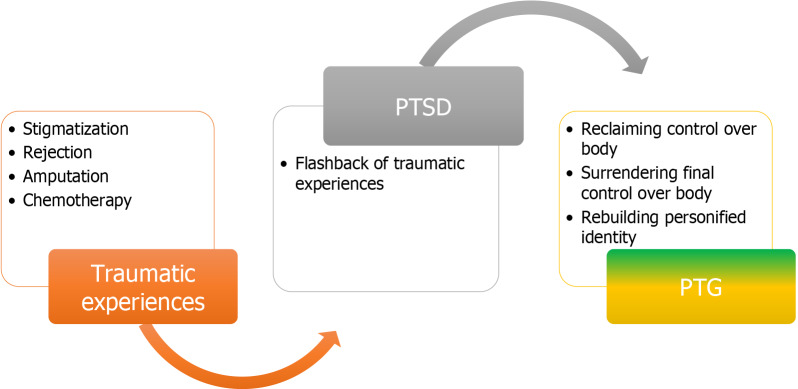

BC patients suffered trauma and PTSD during the diagnosis and treatment stages. These traumatic events include painful experiences during and after diagnosis, psychological distress, depression, and cultural stigma against BC patients. PTSD occurrence among BC patients varies across African countries, as this review disclosed: 90% was reported in Kenya, 80% was reported in Zimbabwe, and 46% was reported in Nigeria. The severity of PTSD among BC patients in Africa was based on the test results communicated to the patients. Furthermore, this review revealed that BC patients experience PTG, which involves losing, regaining, and surrendering final control over the body, rebuilding a personified identity, and newfound appreciation for the body.

CONCLUSION

Patients with BC undergo numerous traumatic experiences during their diagnosis and treatment. Psychological interventions are needed in SSA to mitigate trauma and PTSD, as well as promote PTG.

Keywords: Trauma, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Post-traumatic growth, Breast cancer, Patients, Sub-Saharan Africa

Core Tip: A high incidence of breast cancer (BC) is common among African females, and a diagnosis thereof is misconstrued as a death sentence because of the low survival rate. BC affects female patients from 25 years to 65 years of age and it is associated with psychological problems such as trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, there is a lack of pooled empirical evidence on the comorbidity of BC, trauma, PTSD, and post-traumatic growth among female African patients.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is a global disease[1]. A report from the Global Cancer Observatory revealed that BC has an incidence of 30.3% in female patients with cancer, irrespective of age, and caused approximately 685000 deaths in 2020[2,3], while in 2022, 2.3 million cases were reported and 670000 deaths were recorded globally[4]. The American Cancer Society estimated that, in 2024, 310720 new cases of invasive BC will be diagnosed, as well as 56500 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ, while approximately 42250 women will die from BC[5,6]. BC is also the most common type of cancer diagnosed among women in sub-Saharan African countries (SSA)[7,8]. SSA countries have the maximum age-standardized prevalence rate of 17.3 per 100000 women per year. The North African region has the highest occurrence of BC patients, with an age-standardized incidence of 43.2 per 100000 women per year[9] followed by Africa and Southern Africa countries with age-standardized occurrences of 38.6 and 38.9 per 100000 women per year, respectively[8].

BC occurs in every country worldwide. Furthermore, BC affects women, irrespective of age after puberty. However, there is a low prevalence of BC and a low death rate in countries with a very high human development index (HDI), whereas in countries with a low HDI, there is a significant prevalence of BC and high associated death rates[10]. In some parts of SSA, there is a misconception that BC cannot be cured[2]. Hence, BC ailment triggers psychological problems such as trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the recovery process known as post-traumatic growth (PTG) immediately after treatment starts.

Trauma is one of the psychological problems that has a severe emotional and biological stress reaction to an unusual event experienced as potentially harmful or aversive[11]. It has been conceptualized as the occurrence of events, victim experiences of the events, and the extent of emotional, physical, and social impacts[12].

BC diagnosis is a sudden traumatic event associated with doubt about the future and changes in social responsibility and relationships[13,14]. BC has been identified as a threat to patients’ identities, cultural ideals of feminism, beauty, sexuality, and maternal potential[15]. Individuals with BC habitually experience additional psychological difficulties due to the changes they undergo in their body, as well as family, social, and career roles. These unpleasant BC experiences usually result in traumatic experiences for the patient[16]. Women who have experienced trauma before reported severe BC-related traumatic symptoms and that childhood emotional abuse substantially predicted BC-related intrusive symptoms independently[17]. This report suggests that BC diagnosis has the highest chances of triggering cognitive and emotional reactions that are associated with patients’ previous trauma experiences.

Patients may experience BC and PTSD as comorbid illnesses. PTSD is a flashback of traumatic experiences emanating from patients’ severe experiences of traumatic events[18]. Cancer has been recognized by the American Psychiatric Association as a traumatic stressor that could precipitate PTSD[19]. PTSD has three diagnostic characteristics, which include re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and moods, and arousal[20]. Prevalence of PTSD among BC patients is between 3%-32%[21]. Further, there are several factors that contribute to the occurrence of PTSD in BC patients, including the stage of cancer, prognosis, treatment method, extent of pain, social support, hospitalization, and the educational level of the patient[22,23].

In addition, despite the negative feelings BC patients experience after cancer diagnosis, they also experience positive effects, like realizing internal growth, shifting perceptions about life, and establishing rich interpersonal relations, which are all attributes of PTG[14]. PTG is designed to promote psychological adaptation, quality of life, facilitate health promotion behavior, and increase resistance and survival rates among BC patients[14,23]. PTG has three components, which include the perception of change in self (personal empowerment and resilience), change in feeling toward others (accepting various attitudes, improved compassion, and sympathy), and change in life philosophy (changing to feel out of control, helpless, and alienated)[24].

This review aimed to scope the current literature to map out empirical evidence from peer review articles on the trajectory of comorbidity between BC and trauma, BC and PTSD, and BC and PTG. Existing literature reviews, which examined the relationships between BC and trauma, BC and PTSD[25], and BC and PTG[26], were limited in scope because they examined the linear connection between the two variables in isolation, which is only a fraction of the current review. Nevertheless, the purpose of this review was to provide an updated empirical comparison of BC patient experiences with traumatic events, PTSD, and PTG, as well as their comorbidities. Based on extensive research of online databases, there was no existing literature in this regard; hence, this review is the first of its kind to holistically review the pooled trajectory of BC patient experiences of trauma to the recovery stage. This review may provide substance to mental health practitioners and cancer patients because it reveals verified and updated experiences of BC patients in relation to the concepts of trauma and the recovery stage. This review will make significant contributions to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), Goal 3, which ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being for all at all ages. We expect that the pooled empirical evidence will enable public health practitioners to collaborate with therapists to develop effective interventions and support services for BC patients to promote PTG among patients with trauma and PTSD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Empirically peer-reviewed articles from databases were pooled using the scope review approach. During the conceptualization of this topic, selected databases were screened for existing scoping reviews like the current review, but none were found. The scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search strategy

Peer-reviewed articles published from 1999 to 2024 were identified from databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, Scimago, and PsycINFO. We developed search terms based on the key variables in the topic. Search terms developed from the link between trauma and BC included “BC pains” “BC distress” “BC shocks”, “BC menace”, and “breast terrifying experience”. For the link between BC and PTSD, we used the following search terms: “BC patients’ experiences of PTSD”, “association between BC and PTSD”, and “comorbid BC and PTSD”. For the link between BC and PTG, we formulated the following search terms: “BC with comorbid PTG” and “PTG in women with BC”. The literature search was concluded in March 2024.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion Criteria: All studies included in this review were peer-reviewed and empirical research articles. Studies conducted in the English language that used qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods research approaches, and studies conducted exclusively on women from SSA women diagnosed with BC, were included.

Exclusion criteria: We excluded studies such as gray literature (theses or dissertations, book chapters, editorials, and conference abstracts), as well as all kinds of reviews and meta-analyses. Studies that addressed BC without trauma, PTSD, or PTG were excluded. In addition, studies that addressed trauma, PTSD, and PTG without BC were excluded.

Study screening

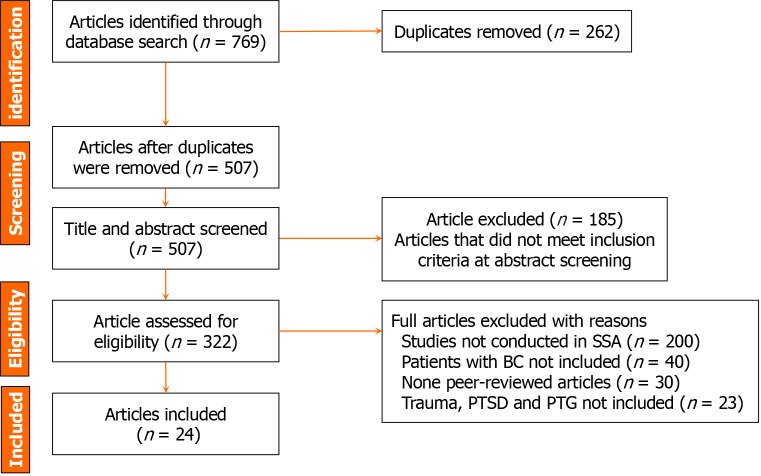

Screening and selection: At this stage, the two-selection process included abstract and full-text screenings. In addition to conducting extensive searches of selected databases, a co-author with a strong background in educational psychology independently screened the titles and abstract sections of the selected articles to determine if they met the criteria for full-text screening. For possible screening, the first author, who has a background in educational research, reviewed all the references in the article. The two authors screened each article in entirety. The two authors used consensus to determine article inclusion after extensive discussion of the differences. First, the authors coded the data for data extraction. The screening process is represented in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating the article selection processes from identification to inclusion. BC: Breast cancer; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder; SSA: Sub-Saharan African countries.

Data extraction process

Data were extracted from selected articles using a PICO-defined data extraction guideline. Data extracted from the literature include year, author name, country, population/sample, method, and results. The authors participated in the review. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of the articles reviewed

|

Ref.

|

Location

|

Variables

|

Participant characteristics

|

Method/sample

|

Instruments

|

Results

|

| Bosire et al[27], 2020 | South Africa | BC Comorbid suffering |

Qualitative study 50 women |

Interview | This study revealed that participants experienced discrimination and isolation, as well as fear of been rejected by their families. It was also found that BC patients are dissociated from their family members and the wider community | |

| Maree et al[28], 2015 | Zambian | BC Severe suffering |

48.2 years | Qualitative descriptive survey 10 participants |

Interview | This qualitative study revealed that patients with advanced BC experience severe suffering before diagnosis. After undergoing chemotherapy, the patient became fearful of stigma and lost their femininity, strength, appearance, role, and support system |

| Lambert et al[29], 2020 | South Africa | BC Trauma |

Aged between 28 and 76 years. Average 49 | Qualitative 50 black women |

Interview | This study revealed that most patients felt that they would die once diagnosed with cancer. Participants reported that chemotherapy causes fear, distress, and pain, which leads to traumatization |

| Coetzee et al[30], 2019 | South Africa | Breast treatment and experiences Distress |

Age between 48 and 66 years | Qualitative. 12 South African women | Interview | South African women react to BC with shock and disbelief. Women's experiences of diagnosis and treatment were accompanied by psychological distress |

| Teye-Kwadjo et al[31], 2022 | Ghana | BC Persistent pain, physical appearance |

Between 22 and 69 | Qualitative 12 Ghanaian women |

Interview | Participants revealed that BC treatment and diagnosis are associated with chronic pain in the breast, chest, and armpit areas. It was revealed that participants feared loss of hair, swollen hands, and numbness due to treatment |

| Nwakasi et al[32], 2023 | Nigeria | BC Cancer stigma |

Qualitative 30 BC survival |

Interview | BC is a potentially stigmatizing illness | |

| Iddrisu et al[33], 2020 | Ghana | BC Trauma |

From 28 to 45 years | Qualitative exploratory 12 participants |

Interview | BC patients felt depressed, cried, and were traumatized after being diagnosed with BC. Some of the patients felt that they were unattractive due to the mastectomy done; however, they used handkerchiefs as breast prostheses |

| Lebimoyo and Sanni[34], 2023 | Nigeria | BC, PTSD | Between 25 to 60 years | Descriptive 183 patiently diagnosed female BCs | Questionnaires | Post-traumatic stress symptoms were 46% at baseline assessment. However, there was a significant reduction after 3 months (31%) and 6 months (22%). It was observed that PTSS is higher at early diagnosis |

| Eugenia et al[35], 2019 | Zimbabwe | BC Anxiety, fear and depression, PTSD |

Aged 30 to 80 years | Qualitative study 12 participants |

Semi-structured interviews | 100% of participants experienced anxiety, 80% experienced post-traumatic stress, and 20% experienced depression |

| Alagizy et al[36], 2020 | Egypt | BC, Trauma symptoms (anxiety, perceived stress, and depression). |

Mean age 52.29 ± 11.64 years | Mixed method 60 BC patients | Questionnaires and interview | The study found that depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and perceived stress were 68.6%, 73.3%, and 78.1% among patients, respectively |

| van Oers and Schlebusch[37], 2021 | South Africa | BC Trauma symptoms (distress, suicidal ideation) |

Quantitative study. 80 female BC patients | Descriptive statistics Questionnaires | BC patients experienced high levels of hopelessness and suicidal ideation. These patients also encounter psychological stress | |

| Schlebusch and van Oers et al[38], 1999 | South Africa | BC Trauma symptoms (psychological distress, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation) |

Mean age for black 42.2 years and 54.3 years for white | Descriptive survey study. 50 South African women | Questionnaire | Black South Africans were found to experience depression, somatization, and body image dysphoria, and use less adaptive styles than white South Africans. As a result of BC symptoms, both groups experience the same level of anxiety |

| Stecher et al[39], 2023 | South Africa | BC Mastectomy |

Age (34 to 58) | Qualitative 7 participants | Semi-structured interviews | Cultural stigma against BC patients still exists in the South African population |

| Ofei et al[40], 2023 | Ghana | BC PTG |

128 BC survival | Questionnaire | PTG among BC patients is determined by social supports, optimism, religiosity, and hope, all of which assist them in managing their illness | |

| Aliche et al[41], 2023 | Nigeria | BC and other cancers PTG |

Age range 28–55 | 957 cancer patients | Questionnaire | In the Nigerian context, meaning in life, a mechanism of mindfulness was found to promote PTG in cancer patients |

| Olaseni et al[42], 2016 | Nigeria | BC and other cancers PTG |

Age range of 28–55 | 120 participants | Questionnaire | PTG was predicted by age, sex, education, and the results of the diagnosis |

| Aliche[43], 2022 | Nigeria | General cancer PTG |

550 patients | Questionnaire | Positive reappraisal and self-compassion independently mediated PTG. This indicates that reappraisal and self-compassion significantly facilitate PTG in patients with cancer | |

| Gorven et al[44], 2018 | South Africa | BC PTG |

25 and 50 years | Qualitative study 6 women |

Interview | In South Africa, PTG involves losing body control, reclaiming body control, surrendering final control over the body, rebuilding personified identity, and gaining a new appreciation for the body |

| Agyei[45], 2018 | Ghana | BC PTG |

Cross-sectional survey. 150 BC women | Questionnaires. | PTG was positively associated with age, survival year, and marital status. There was no association between educational level, religion, employment status, and PTG. It was also revealed that social support, coping, and optimism were directly related to PTG | |

| Fekih-Romdhane et al[46], 2022 | Tunisia | BC PTG |

Mean age of 52.7 ± 9.8 | Quantitative seventy-nine (79) postoperative BC women | Questionnaires | Patients found that they were stronger than they assumed (70.0%), had strong religious faith (65%), and had the capacity to accept the way things work out (63.8%). The results also revealed that anxiety and social support are substantially associated with PTG |

| Njoroge and Asata et al[47], 2022 | Kenya | BC Traumatic stress, and PTSD |

Age group of 25–47 years | Mixed method research design. 60 females sampled through purposeful sampling | Impact of events scale revised and interviews | The structure of traumatic stress at the time of BC diagnosis and treatment depended on how test results were communicated to the patients, and treatment associated side effects like body image changes, mastectomy, and weight loss or gain. Also, 90% of the participants reported severe PTSD, while 6.70% and 3.30% reported moderate and low PTSD, respectively |

| Kagee et al[48], 2017 | South Africa | BC Trauma symptoms (distress, and depression) |

Mean age 55.70 years | Quantitative study. Sample of 201 female BC | Checklist Questionnaire |

Distress and depression were prevalent among BC patients in South Africa, specifically those with higher body change stress and lower perceived support |

| Berhil et al[49], 2017 | Morocco | BC Traumatic distress |

Age 50 ± 8 | Quantitative sample of 446 Moroccan women | Questionnaire | A psychological distress prevalence rate of 26.9% was reported among Moroccan BC patients |

| Ohaeri et al[50], 2012 | Nigeria | BC, Trauma symptom (psychic distress, and adjustment) |

Age 49.9 | Descriptive research design. Sample of 63 attendees | Questionnaire | The greatest worry was associated with fear of death. Psychic distress was negatively associated with BC management. Fear of people's perceptions was a predictor of psychological distress |

BC: Breast cancer; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder; PTG: Post-traumatic growth.

RESULTS

The scoping review search produced 769 records from the databases. After removing duplicate articles, 507 titles and abstracts were screened, and 185 articles were eliminated. In total, 322 full articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 298 were removed. Finally, 24 articles were included in the study, as summarized in Figure 1.

Characteristics of the included articles

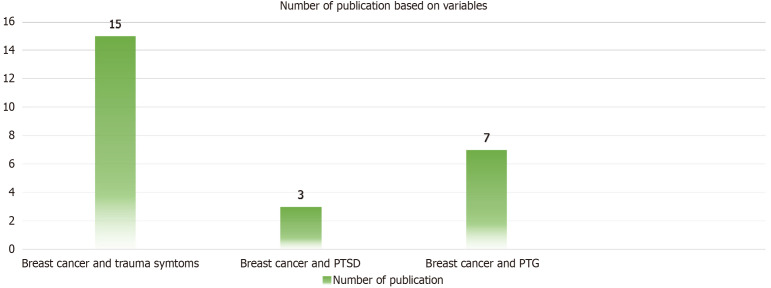

The features of the reviewed articles are presented in Table 1. The publication dates ranged from 1999 to 2023[27-50]. Fifteen studies investigated the comorbidity of trauma and BC, two studies treated BC and PTSD, and seven studies investigated the comorbidity of BC and PTG in Africa as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Publications on breast cancer and trauma, breast cancer and post-traumatic stress disorder, and breast cancer and post-traumatic growth. PTG: Post-traumatic growth; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

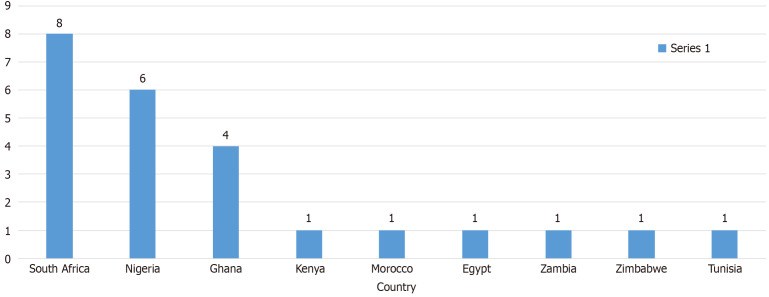

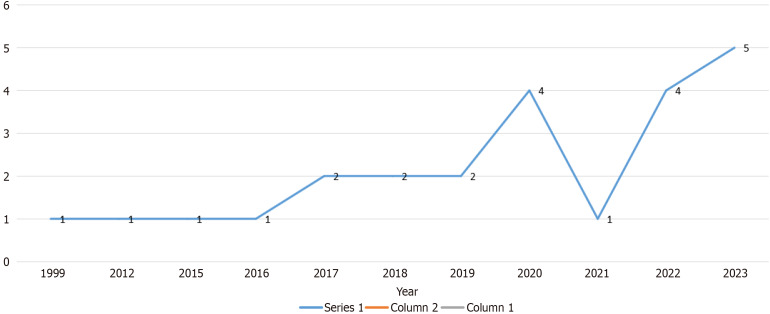

Most studies were conducted in South Africa[27-30,37-39,44,48], followed by Nigeria[32,34,41-43,50], Ghana[31,33,40], Kenya[47], Morocco[49], Egypt[35], Zambia[28], Zimbabwe[35], and Tunisia[46], as shown in Figure 3. The first article selected for this review was published in 1999, while the most recent article was published in 2023 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of selected studies by country.

Figure 4.

Trend of publication on trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic growth based on year.

We included 3316 BC patients in this review. The comorbidity of trauma, PTSD, and PTG among BC patients gained the attention of research from 2017 until 2020, when there was a drastic decline in the interest of researchers in the area (Figure 4). However, there was a sharp increase in the interest of researchers from 2022 to 2023.

The major variables considered were trauma or trauma symptoms, PTSD, and PTG. The age of the participants in this review ranged from 25 to 80 years. Most of the studies adopted a quantitative[37,38,40-50], qualitative[27-33,39,44], and mixed method[36,47]. The instruments for data collection were interviews for qualitative studies and questionnaires for quantitative studies. However, some studies that adopted a mixed method utilized both interviews and questionnaires (Table 1).

Outcomes of the reviewed articles

Table 1 reveals the major outcomes of the selected studies in this scoping review. These variables are organized into three major themes based on the three variables of the study, including the comorbidity of traumatic symptoms and BC ailment, PTSD and BC ailment, and PTG and BC (Figure 5). Fifteen studies investigated the comorbidity of BC and traumatic symptoms, revealing that BC patients experience traumatic events such as trauma associated with chemotherapy treatment[29]; discrimination, isolation, and rejection[27]; severe pains before diagnosis[28]; loss of femininity[28]; stigmatization[39]; psychological distress associated with diagnosis and treatment[30]; fear of loss of hair; swollen hands and numbness due to treatment[31]; depression after being diagnosed with BC[33]; experiencing high levels of hopelessness and suicidal ideation; and that cultural stigma against BC patients still prevails within the South African population[39].

Figure 5.

Summary of findings. PTG: Post-traumatic growth; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Studies have shown that the extent to which BC patients experience PTSD varies. In Kenya, a study found that 90% of the participants experienced severe PTSD, 6.70% experienced moderate PTSD, and 3.30% experienced low PTSD[47]. In Zimbabwe, a study revealed that 80% of BC patients reported PTSD[35]. In Nigeria, a study revealed that post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) were 46% at baseline assessment and observed that PTSS is higher at early diagnosis[34]. The extent of PTSD experiences among BC patients during diagnosis and treatment in Africa depends on how the test results are communicated to the patients, and treatment associated side effects include body image changes, mastectomy, and weight loss or gain[47].

This review disclosed that PTG among BC patients in South Africa involves losing, regaining, surrendering final control over the body, rebuilding a personified identity, and newfound appreciation for the body[44]. In Nigeria and Ghana, PTS was promoted by social support, optimism, religiosity, and hope[41,45] as well as mindfulness[41]. In Tunisia, PTG was positively associated with strong religious faith (65%), and the potential to accept the way things work out (63.8%); however, it was negatively associated with anxiety. PTG among BC patients in Nigeria was mediated by positive reappraisal and self-compassion[43]. There is controversy over the predictors of PTG among BC patients in Africa. In Nigeria, a study found that educational levels of BC patients, knowledge of diagnosis, and religion predicted PTG among BC patients[42]. However, in Ghana, educational level, religion, and employment were not predictors[45].

DISCUSSION

This scoping review is the first to examine existing empirical literature on the comorbidity of trauma, PTSD, and PTG among BC patients in Africa. Understanding the simultaneous occurrence of these psychological variables and BC ailments in patients is crucial to guide future research and identify areas that need support and intervention. This is crucial since trauma, which is a psychological injury due to strong emotional stimulus, causes adverse mental health problems among BC patients. This discussion includes empirical evidence of the comorbidity of trauma and BC in patients, PTSD and BC, and PTG and BC.

With respect to the comorbidity of trauma and BC in patients, this study, through a systematic search for empirical evidence, revealed that BC patients experience several traumatic symptoms before diagnosis, during diagnosis, and during treatment in Africa. An amputation of the breast is one of the most common traumatic events experienced by BC patients in Africa. Amputation of the breast is linked to chemotherapy, which is characterized by excruciating pains that often lead to amputation of the breast. BC patients in Africa experienced chemotherapy, expressing fear of stigma and loss of femininity, appearance, and feminine roles due to amputation[27]. Studies have indicated that there is still a stigma associated with BC in Africa, and that family members, close friends, and the broader community discriminate against BC patients[27,39]. These experiences have resulted in the development of depressive symptoms, somatization, and body image dysphoria among African BC patients and survivors. In this severe scenario, traumatic experiences have engendered hopelessness, depression, and suicide ideation among patients and survival in the African region[37]. Briefly, the comorbidity of BC and traumatic experiences have devastating impacts on the mental health of BC patients in Africa, which needs immediate attention. This finding confirms the review reports of Freeney and Tormey[51] on BC and chronic pain. It was found in the study that BC is associated with chronic pain resulting from its symptoms and treatment, such as chemotherapy. The results of this review report confirm those of a scoping review conducted by Eseadi and Amedu[2] on BC patient depression experiences. The report from the scoping review revealed that depression is one of the common psychological problems that BC patients experience in Nigeria.

The results of this study indicate that PTSD and BC are comorbid among patients in Africa. This demonstrates that BC patients and survivors in Africa experience flashbacks of the painful experiences encountered at the time of diagnosis and treatment. However, the BC literature emphasizes that PTSD rates vary from country to country. Current evidence indicates that PTSD is high among Kenyan BC patients; 90% of Kenyan BC patients experience severe PTSD[47]. Zimbabwe came in second in the rankings for high incidence of PTSD among BC survivors, as a study found that over 80% of Zimbabwean BC patients were suffering from PTSD[35]. Nigeria took third place, as a study revealed that 46% of female BC patients experience PTSD at early diagnosis[34]. In Africa, BC patient experiences of PTSD are higher in early diagnosis, which is triggered by how the results of the diagnosis are communicated to patients. The manner in which BC patients receive their health information considers the severity of the ailment, deformation of the female body structure, and treatment implications to determine the degree of PTSD at later stages.

This scoping review revealed that PTSD experiences are not high among BC patients in Africa, as detailed in only three literature reports. The experience of PTSD among African BC patients has a substantial adverse impact on their mental health. Since the literature has emphasized that BC incidence is high at early diagnosis, early intervention should be emphasized among traumatized patients. This could be attributed to the low survival rate of BC patients, the lack of researcher interest in investigating the incidence of PTSD in BC patients, or the impact of support services that buffer the negative impact of traumatic experiences on developing PTSD. This finding confirms those of the systematic literature conducted by Parikh[26]. The study reported that PTSD is present at the early diagnosis of BC among patients, while PTG develops once treatment is initiated. The prevalence rate of PTSD among BC patients is higher than the results of the meta-analysis done by Wu et al[52], which revealed that the pooled incidence of PTSD among BC patients is 9.6%, and young adults are at a higher risk of developing PTSD.

Finally, this review found that BC patients in Africa experience PTG, which is the positive change individual patients experience after encountering traumatic events associated with BC treatment. PTG manifests in BC patients in Africa through losing the body, reclaiming control over the body, surrendering final control over the body, rebuilding a personified identity, and newfound appreciation for the body[41,45]. It is important to note that BC PTG is a complicated process of transmission from negative feelings that arise because of traumatic events to positive feelings of acceptance of changes as a result of the cancer diagnosis. Therefore, the PTG among BC patients in Africa centers on the total and significant conception of body structure. Several factors have been identified in the literature that promote PTG among BC patients in Africa. However, these factors vary across African countries. The common facilitators of PTG among BC patients in Africa are strong religious faith, social support, educational status, and the individual potential to accept the way things unfold[40,42,46]. Religion and education have been identified as significant variables that promote PTG among BC patients in Africa due to the fact that most African countries are spiritually inclined and BC patients attach their medical treatment and recovery to their faith in God. However, there is still controversy among public health researchers in BC literature that some of these variables, such as religion and educational level, do not contribute to PTG in African patients. Therefore, we call on future researchers to investigate the variables that promote PTG among BC patients on the African continent and to resolve the lingering disagreement in the BC literature on the effectiveness of religiosity and education in enhancing PTG.

In the context of BC literature, this finding supports those of previous studies. The study conducted by Casellas-Grau et al[53] revealed that PTG among BC patients is positively associated with spirituality, hope, and meaning, and negatively associated with depressive and anxious symptoms. In addition, this supports a global review done by Kolokotroni et al[54], which revealed that PTG is related to social support, cognitive processing of BC, and coping strategies of BC women.

Knowledge gap in the literature

This review has identified some significant knowledge gaps in research on traumatic, PTSD, and PTG experiences among BC patients in the African context. Most of the studies included in this review were conducted in South Africa, followed by Nigeria, and Ghana. This implies that research on the comorbidity of traumatic experiences, PTSD, and PTG is still growing. This is because few studies were retrieved from north, east, and central African countries. This infers that researchers within these locations are not aware of the devastating impact of the comorbidity of trauma and BC on the mental health of patients. Concerning the adverse effect of comorbidity in PTSD and BC patients, only three studies were conducted in this regard, while only seven studies revealed the PTG of BC patients. We call for more empirical studies in these areas to unveil recent empirical evidence on the experiences of trauma, PTSD, and PTG among BC patients in Africa.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review is the first to establish the trajectory of traumatic experiences, PTSD, and PTG among patients on the African continent. This review was able to explore several databases regarding traumatic experiences peculiar to BC patients in Africa. In addition, this review extended the scope of the literature to cover PTSD, and PTG among BC patients in Africa. We did not employ date restriction; hence, we revealed holistic empirical evidence concerning BC patient experiences of traumatic events, PTSD, and PTG in an African context. As strong as this review is, it has some inherent limitations. The review was limited to empirical literature published in English only, and other exclusion criteria were employed in the review process. The search terms used to explore the literature may have also contributed to the categories of studies retrieved for this review. These criteria may have excluded significant information that concerns the traumatic events, PTSD, and PTG experiences of BC patients in the African context. It should be noted, however, that these limitations do not invalidate the contribution of this review to the existing BC literature regarding the lives of African BC survivors with respect to their experiences of traumatic events, PTSD, and PTG.

CONCLUSION

The comorbidities of trauma, PTSD, and BC have adverse effects on patient mental health; however, PTG promotes positive self-perception change. Our study revealed that BC patients in Africa experience many traumatic experiences that limit their recovery time, alter their self-perception, and change their role in society. In addition, empirical evidence has demonstrated that few of these BC survivors in Africa experience PTSD, which has a detrimental effect on their mental health. However, BC literature has revealed that some patients develop PTG after experiencing traumatic events, which is positively associated with recovery. In the Africa context, PTG has been associated with patients' faith in God, support services, and knowledge of the BC ailment. It is significant to emphasize the fact that BC patients, despite their encounter with traumatic events during diagnosis and treatment, also experience stigmatization and discrimination. This review has shown that the literature on trauma, PTSD, and PTG among BC patients in Africa is still growing; hence, more research needs to be done on the continent. We call for more research on the traumatic events associated with chemotherapy treatment and PTSD experiences in the African context. Researchers in Africa have underemphasized the experience of PTSD in BC patients. In light of the fact that BC is associated with psychological problems such as trauma and PTSD, we advocate for more intervention programs to curtail the adverse effects on patients. Furthermore, we call for a more collaborative approach to providing support services that will facilitate the PTG of BC patients in the African context.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflicts of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Africa

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Ghimire R, Nepal S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang WB

References

- 1.Arinola GO, Edem FV, Odetunde AB, Olopade CO, Olopade OF. Serum Inflammation Biomarkers and Micronutrient Levels in Nigerian Breast Cancer Patients with Different Hormonal Immunohistochemistry Status. Arch Breast Cancer. 2021;8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eseadi C, Amedu AN. Examining Depression among Breast Cancer Survivors in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. Arch Breast Cancer. 2024;11 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadhav BN, Abdul Azeez EP, Mathew M, Senthil Kumar AP, Snegha MR, Yuvashree G, Mangalagowri SN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of breast self-examination is associated with general self-care and cultural factors: a study from Tamil Nadu, India. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24:151. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-02981-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla N, Shah K, Rathore D, Soni K, Shah J, Vora H, Dave H. Androgen receptor: Structure, signaling, function and potential drug discovery biomarker in different breast cancer subtypes. Life Sci. 2024;348:122697. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Key Statistics for Breast Cancer. How Common Is Breast Cancer? Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html .

- 6.Breast Cancer Facts and Stats 2024. Incidence, Age, Survival, and More. Natl. Breast Cancer Found. Available from: https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-cancer-facts .

- 7.Bhuiyan M. Profile and Features of Breast Cancer in HIV Positive and Negative Patients at Mankweng Academic Hospital, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Arch Breast Cancer. 2023;10 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adewale Adeoye P. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Breast Cancer Updates. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azubuike SO, Muirhead C, Hayes L, McNally R. Rising global burden of breast cancer: the case of sub-Saharan Africa (with emphasis on Nigeria) and implications for regional development: a review. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:63. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1345-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Breast cancer. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer .

- 11.Day S, Hay P, Tannous WK, Fatt SJ, Mitchison D. A Systematic Review of the Effect of PTSD and Trauma on Treatment Outcomes for Eating Disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25:947–964. doi: 10.1177/15248380231167399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Available from: https://calio.dspacedirect.org/items/50091c5f-47e2-4045-9686-3af13ce0f4c8 .

- 13.Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, Juvet LK, Elvsaas IK, Oldervoll L, Anker G, Falkmer U, Lundgren S, Leivseth G. Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20:909–918. doi: 10.1002/pon.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bae KR, So WY, Jang S. Effects of a Post-Traumatic Growth Program on Young Korean Breast Cancer Survivors. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/healthcare11010140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang SY, Shu BC, Chang YJ. The effect of breast reconstruction surgery on body image among women after mastectomy: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karimzadeh Y, Rahimi M, Goodarzi MA, Tahmasebi S, Talei A. Posttraumatic growth in women with breast cancer: emotional regulation mediates satisfaction with basic needs and maladaptive schemas. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12:1943871. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1943871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith RE, Jandorf L, Valdimarsdottir H, Amend KL, Stoudt BG, Rini C, Hershman D, Neugut A, Reilly JJ, Tartter PI, Feldman SM, Ambrosone CB, Bovbjerg DH. Traumatic stress symptoms and breast cancer: the role of childhood abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amedu AN. Assessment of psychological treatments and its affordability among students with post-traumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Int J Home Econ Hosp Allied Res. 2023;2:248–264. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Am Psychiar Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM Libr. 2013. Available from: https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Arnaboldi P, Lucchiari C, Santoro L, Sangalli C, Luini A, Pravettoni G. PTSD symptoms as a consequence of breast cancer diagnosis: clinical implications. Springerplus. 2014;3:392. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnaboldi P, Riva S, Crico C, Pravettoni G. A systematic literature review exploring the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and the role played by stress and traumatic stress in breast cancer diagnosis and trajectory. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2017;9:473–485. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S111101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honari S, Soltani D, Mirimoghaddam MM, Kheiri N, Rouhbakhsh Zahmatkesh MR, Saghebdoust S. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Growth in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study in a Developing Country. Indian J Gynecol Oncolog. 2022;20:60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan MW, Ho SM, Tedeschi RG, Leung CW. The valence of attentional bias and cancer-related rumination in posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2011;20:544–552. doi: 10.1002/pon.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The Foundations of Posttraumatic Growth: An Expanded Framework. In: Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth. Routledge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai W, Nusrath S, Zhu R. Systematic review of depressive, anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms among Asian American breast cancer survivors. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037078. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh D, De Ieso P, Garvey G, Thachil T, Ramamoorthi R, Penniment M, Jayaraj R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients--a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:641–646. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.2.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosire EN, Mendenhall E, Weaver LJ. Comorbid Suffering: Breast Cancer Survivors in South Africa. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:917–926. doi: 10.1177/1049732320911365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maree JE, Mulonda J. “My experience has been a terrible one, something I could not run away from”: Zambian women’s experiences of advanced breast cancer. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2015;3:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert M, Mendenhall E, Kim AW, Cubasch H, Joffe M, Norris SA. Health system experiences of breast cancer survivors in urban South Africa. Womens Health (Lond) 2020;16:1745506520949419. doi: 10.1177/1745506520949419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coetzee B, Roomaney R, Smith P, Daniels J. Exploring breast cancer diagnosis and treatment experience among a sample of South African women who access primary health care. South African Journal of Psychology. 2020;50:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teye-Kwadjo E, Goka AS, Ussher YAA. Unpacking the psychological and physical well-being of Ghanaian patients with breast cancer. Dialogues Health. 2022;1:100060. doi: 10.1016/j.dialog.2022.100060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nwakasi C, Esiaka D, Chinelo N, Ahmed S. How will I live this life that I'm trying to save? Being a female breast cancer survivor in Nigeria. Ethn Health. 2024;29:147–163. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2023.2279478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iddrisu M, Aziato L, Dedey F. Psychological and physical effects of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on young Ghanaian women: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:353. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02760-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebimoyo AA, Sanni MO. A prospective longitudinal study of post-traumatic stress symptoms and its risk factors in newly diagnosed female breast cancer patients. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2023;30:105. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eugenia M, Sanganai K, Herbert Z. Psychosocial challenges affecting women survivors of breast cancer. A case from Gweru, Zimbabwe. IJEPC. 2019;9:92–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alagizy HA, Soltan MR, Soliman SS, Hegazy NN, Gohar SF. Anxiety, depression and perceived stress among breast cancer patients: single institute experience. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27:29. [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Oers H, Schlebusch L. Breast cancer patients' experiences of psychological distress, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. J Nat Sci Med. 2021;0:0. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlebusch L, van Oers HM. Psychological Stress, Adjustment and Cross-Cultural Considerations in Breast Cancer Patients. South African Journal of Psychology. 1999;29:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stecher NE, Cohen MA, Myburgh EJ. Experiences of women in survivorship following mastectomy in the Cape Metropole. S Afr J Surg. 2019;57:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ofei SD, Teye-Kwadjo E, Amankwah-Poku M, Gyasi-Gyamerah AA, Akotia CS, Osafo J, Roomaney R, Kagee A. Determinants of Post-Traumatic Growth and Quality of Life in Ghanaian Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Invest. 2023;41:379–393. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2023.2181636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aliche CJ, Ifeagwazi CM, Ezenwa MO. Relationship between mindfulness, meaning in life and post-traumatic growth among Nigerian cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 2023;28:475–485. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2022.2095576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olaseni A, Ayodele I, F FA. Life Orientation and Personality Attributes: Implications on Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) Among Diagnosed Cancer Patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Res Health Sci Nurs. 2016;2:01–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aliche CJ. The mediating role of positive reappraisal and self-compassion on the relationship between mindfulness and posttraumatic growth in patients with cancer. South African Journal of Psychology. 2023;53:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorven A, du Plessis L. Corporeal Posttraumatic Growth As a Result of Breast Cancer: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2021;61:561–590. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agyei Wiafe S. Posttraumatic Growth Among Breast Cancer Survivors in Ghana. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fekih-Romdhane F, Riahi N, Achouri L, Jahrami H, Cheour M. Social Support Is Linked to Post-Traumatic Growth among Tunisian Postoperative Breast Cancer Women. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Njoroge M, Asatsa S. Traumatic Stress in Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer amongst Women in Nairobi County, Kenya. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kagee A, Roomaney R, Knoll N. Psychosocial predictors of distress and depression among South African breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27:908–914. doi: 10.1002/pon.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berhili S, Kadiri S, Bouziane A, Aissa A, Marnouche E, Ogandaga E, Echchikhi Y, Touil A, Loughlimi H, Lahdiri I, El Majjaoui S, El Kacemi H, Kebdani T, Benjaafar N. Associated factors with psychological distress in Moroccan breast cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Breast. 2017;31:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohaeri BM, Ofi AB, Campbell OB. Relationship of knowledge of psychosocial issues about cancer with psychic distress and adjustment among breast cancer clinic attendees in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Psychooncology. 2012;21:419–426. doi: 10.1002/pon.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feeney LR, Tormey SM, Harmon DC. Breast cancer and chronic pain: a mixed methods review. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187:877–885. doi: 10.1007/s11845-018-1760-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X, Wang J, Cofie R, Kaminga AC, Liu A. Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Breast Cancer Patients: A Meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:1533–1544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casellas-Grau A, Ochoa C, Ruini C. Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer: A systematic and critical review. Psychooncology. 2017;26:2007–2018. doi: 10.1002/pon.4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolokotroni P, Anagnostopoulos F, Tsikkinis A. Psychosocial factors related to posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: a review. Women Health. 2014;54:569–592. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.899543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]