Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the improvement of pain and function after cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injections (CTFESI) for radicular pain.

Design

This is a retrospective observational study of patients receiving fluoroscopically-guided cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injections under a single provider at a tertiary referral center from December 2013 to December 2020. Primary outcome measures were Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), patient reported percent of pain relief, the Patient Health Questionnaire, the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Physical and Mental Health score, and the Pain Disability Questionnaire.

Results

A total of 219 individual patients underwent 261 CTFESI and were included in the analyses. The average subject age was 51.9 years (SD = 11.3) and 50.9 % were male. Following the intervention, average pain relief by NRS at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years was −4.07, −3.82, −4.20, and −4.45, respectively. The average functional improvement with PROMIS-GH physical at 3-months, 6-months, 1- year, and 2-years was 2.23, 2.35, 3.15, and 3.29, respectively.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that patients with cervical radiculopathy report significant pain relief and functional improvement following CTFESI. They can also report clinically important improvement in their health-related quality of life.

Keywords: Cervical radiculopathy, Cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injection

1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal complaints are common, and, specifically, neck pain is the sixth leading cause of years lost to disability [1]. Cervical radiculopathy is a common cause of neck pain that radiates down the arm (estimated annual incidence of 0.08 %), with men more likely to be affected than women. The leading causes of cervical radiculopathy include spondylosis and disc herniation [2]. The majority of cervical radiculopathy patients are managed with conservative treatment, including oral medications and physical therapy, with a favorable prognosis. However, some patients experience a persistence of symptoms requiring more invasive interventions, such as spinal injections or surgery [3,4].

Fluoroscopically-guided cervical epidural steroid injections offer an alternative to surgery for the treatment of refractory cervical radiculopathy. Historically, cervical spine injections have been performed using an interlaminar approach to administer the epidural steroid injection. Steroids in these injections act both to decrease local inflammation at the nerve root and to block nociceptive nerve transmission [5,6]. The transforaminal approach for the epidural injection allows the physician to inject the steroid within close proximity of the inflamed nerve where it can diffuse into the lateral and anterior aspects of the epidural space. This approach may allow for greater diagnostic specificity and more targeted therapeutic placement. These injections are guided using fluoroscopy to ensure correct injection placement and to minimize the risk of adverse events [7].

Currently, questions remain regarding the efficacy of cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injections (CTFESIs) in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. A previous systematic review suggests that about half of patients receive 50 % pain relief at short and intermediate follow-up from intervention with CTFESI [8]. Despite this, many physicians worry about rare, but serious complications of the procedure that have been reported in different case studies [[9], [10], [11]]. Thus, there is a great need to further understand the benefits that patients receive from these injections beyond pain relief. The present study evaluated the clinically important reduction after CTFESIs, characterized not only by patient reported pain, but also by utilizing patient reported outcome surveys before and after intervention to evaluate improvement in both physical and mental health. We also examined which patient and clinical characteristics were associated with improvement in pain.

2. Materials and methods

This was a retrospective, observational study conducted at a tertiary care center. After obtaining institutional review board approval, patients who received CTFESIs between December 11, 2013 and December 23, 2020 by a single spine fellowship-trained Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation staff physician in the Center for Spine Health (completed Spine Medicine Fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic) were identified using the corresponding CPT codes. Two hundred and nineteen individual patients were initially identified that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were patients undergoing CTFESI for cervical radicular pain due to cervical disc herniation, cervical foraminal stenosis and/or pseudoarthrosis by a single spine medicine provider. The exclusion criteria were patents undergoing selective nerve root block without the administration of steroid.

Basic patient data was collected from eligible patient electronic medical records. These data included age, gender, BMI, smoking status, duration of cervical radiculopathy symptoms, prior history of spinal surgery, cervical disk level of the injection, location (right vs left), procedure time (minutes), fluoroscopy time (seconds), positive response (defined as 80 % or greater relief of pain reported immediately post-procedure, during the period of activity of the local anesthetic), pathology (disk herniation vs bony foraminal stenosis), use of blood thinners, physical therapy, MRI, CT, x-ray, EMG, time since this provider's first injection (months), and progression to spine surgery (data was based on chart review).

2.1. Theory

We hypothesized that patients who received fluoroscopically guided cervical transforaminal injections for pain clinically due to cervical radiculitis would experience a clinically important reduction in level of pain and improvement in function after CTFESI.

2.2. Procedural description

All patients received at least one CTFESI. Following procedural informed consent, patients were placed in the supine position with their head turned towards the contralateral side. The fluoroscope was rotated to ∼45° ipsilateral and then, was optimized with further oblique and cranial-caudal adjustments. A 25 gauge, 2.5-inch needle was then inserted to contact the superior articular process. The needle tip was then walked off to enter the posterior neuroforamen. Non-ionized contrast, 180 or 300 mg omnipaque, and digital subtraction angiography were used to confirm positioning. Adjustments were made if a vascular flow was observed on any imaging plane. Once proper positioning was confirmed, 1 ml of 0.5%–2% lidocaine was injected. After a 30-s period without adverse symptoms, 10 mg of dexamethasone (non-particulate steroid) was injected in accordance with SIS guidelines (see Fig. 1) [12].

Fig. 1.

Cervical spine imaging- Ipsilateral oblique, AP with contrast, and DSA image in AP with contrast in neuroforamen outlining the proximal end of the exiting C6 nerve root with spread centrally toward the epidural space.

2.3. Outcome variables

Patient reported outcome (PRO) measures included the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), patient reported percent of pain relief, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System Global Health (PROMIS-GH) Physical and Mental Health T-scores [13,14]. NRS and percent relief were collected verbally pre-procedurally and during follow-up visits. The NRS specifically asked patients about their arm pain. The NRS was our primary outcome. For percent relief, patients directly reported at follow-up visits a percentage between 0 and 100 % to indicate their perceived amount of pain relief compared to their pre-injection pain level. The remaining PROs were conducted through standardized patient electronic survey responses, pre- and post-procedurally. The PHQ-9 and PROMIS-GH are used to measure patient reported depression, health related quality of life, and self-perceived physical disability [13,14]. In 2015, PROMIS-GH replaced EuroQol 5 Dimensions Questionnaire.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of baseline (pre-injection) patient and clinical characteristics were obtained. The PROs were collected at variable time points both pre- and post-injection, depending on when the patient had an appointment. For pre-injection scores, we used the score closest to but no more than 6 months before the patient's first injection. For post-injection scores, we used scores after the patient's last injection and we grouped follow-up times as: 3- month (1-120-days), 6-month (121–240 days), 1-year (241–540 days), and 2-year (541–900 days) post-last-injection. Estimates of average scores at pre-injection and change from pre-injection to each of these approximate follow-up times were obtained for PROs using mixed-effects linear regression. Mixed-effects modeling was used because not all patients had data at both pre-injection and at the follow-up time points and we wished to use all available data. For each PRO, the score was the dependent variable and time was a fixed-effect categorical variable (pre-injection, 3-month, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year follow-up). A random effect for patients was included to account for repeated measurements.

Additionally, we conducted a responder analysis for each PRO. The frequency and percentage of patients who improved by the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) from pre-injection to the aforementioned follow-up time points was computed for each PRO. The MCID value for the NRS was 2 points [15], while the MCID for PHQ-9 and each of PROMIS-GH Physical and Mental Health T-scores was 5. Because many patients were missing PRO data at the various time points, we conducted a worst-case responder analysis. The frequency and percentage of patients improving by the MCID was computed under the assumption that those with missing data did not improve by the MCID.

To examine which patient and clinical factors were associated with improvement in NRS arm pain, we fit single-variable logistic regression models. The dependent variable was improvement in NRS score by 2 points (yes vs. no), and we examined this as short-term improvement (≤3 months post-injection) and long-term improvement (>3 months post-injection). Independent variables considered included age, sex, BMI, active smoking status, symptom duration (0–3 months, 4–12 months, >12 months), history of cervical spine surgery, history of cervical interlaminar injection, disk level, location (right vs left), procedure time (minutes), fluoroscopy time (seconds), positive response, pathology (disk herniation vs bony foraminal stenosis), use of blood thinners, physical therapy, MRI, CT, x-ray, EMG, and time since this provider's first injection (months). Because of low sample size, we included only one independent variable at a time and did not perform multivariable modeling. Odds ratios along with 95 % confidence intervals and p-values were computed.

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.1) [16]. All tests were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, we did not formally adjust for multiple comparisons but interpret our findings in light of the many tests being performed.

3. Results

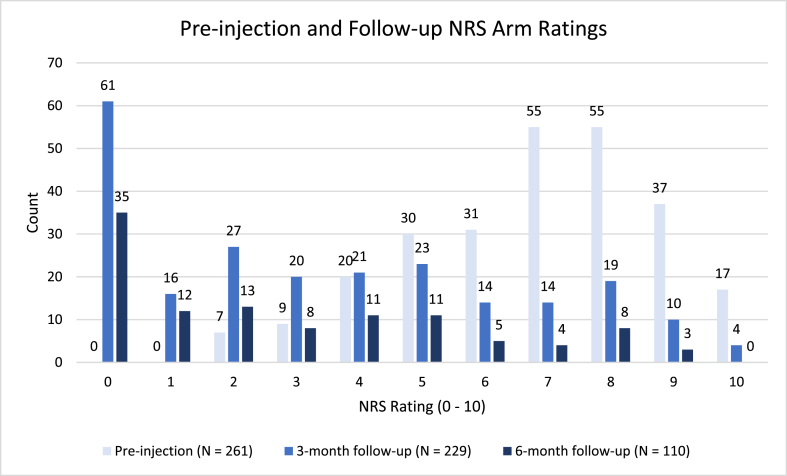

A total of 219 individual patients who underwent cervical injection between December 11, 2013 and December 23, 2020 were included. Average age of the patients was 51.9 years (SD = 11.3 years), 50.9 % were male, and 16.4 % (36/219) of patients had a repeat CTFESI (Table 1). A few of these patients had a repeat injection at a different side and/or different level. At pre-injection, patients reported mean NRS arm pain of 6.9 (SD = 2.0), mean PHQ-9 score 9.1 (SD = 6.3), mean PROMIS-GH Physical Health T-score 38.1 (SD = 7.0), and mean PROMIS-GH Mental Health T-score 45.5 (SD = 9.9). Fig. 2 displays NRS arm prior to CTFESI, and at estimated 3 months and 6 months follow-up intervals.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for patients who underwent cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injection.

| N | 261 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 51.9 (11.3) |

| Male | 133 (50.9 %) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.1 (5.3) |

| Active Smoker | 59 (26.9) |

| Duration of Symptoms (months), Median (IQR) | 9 (4, 25) |

| History of Cervical Surgery | 49 (18.8 %) |

| History of Cervical Interlaminar ESI | 50 (19.2 %) |

| Disk Level | |

| C3-4 | 10 (3.8 %) |

| C4-5 | 24 (9.2 %) |

| C5-6 | 109 (41.8 % |

| C6-7 | 99 (37.9 %) |

| C7-T1 | 19 (7.3 %) |

| Positive Response | 224 (85.8 %) |

| Cervical Pathology | |

| Disk Herniation | 86 (32.9 %) |

| Bony Foraminal Stenosis | 172 (65.9 %) |

| Pseudoarthrosis | 3 (0.11 %) |

| Physical Therapy | 215 (82.4 %) |

| MRI | 255 (97.7 %) |

| CT | 95 (36.4 %) |

| Xray | 234 (89.7 %) |

| EMG | 111 (42.5 %) |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, Interquartile Range.

Fig. 2.

Pre-injection Pain Scores (0–10) on NRS scale compared to 3-month and 6-month follow-up.

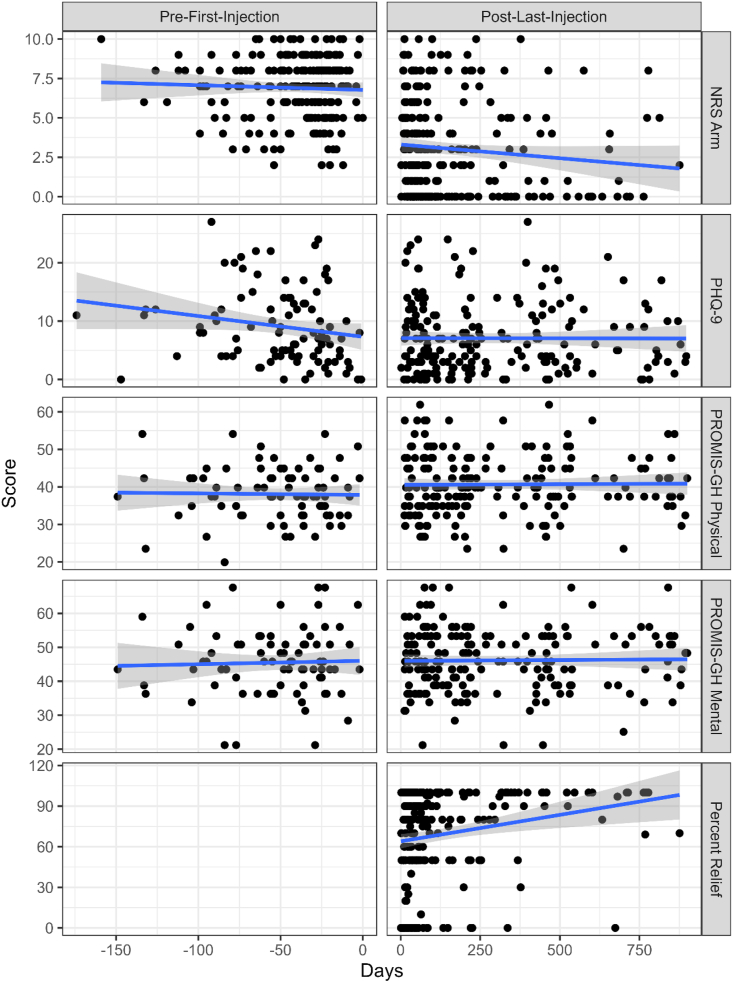

Fig. 3 shows scatterplots of NRS arm, PRO scores over time for both pre- and post-injection and Percent Relief. Estimates of PRO scores at pre-injection and change from pre-injection to follow-up are shown in Table 2. NRS arm pain and PROMIS-GH Physical Health T-scores significantly improved at all follow-up time points. PHQ-9 scores significantly improved from pre-injection to the 3- month, 6-month, and 2-year follow-up, but not at the 1-year follow-up. PROMIS-GH Mental T-scores improved only at the 2-year follow-up time point. Patient-reported percent relief mean (SD) reported values was 66.0 % (SD = 33.5 %) at 3-month, 66.2 % (SD = 37.4 %) at 6-month, 83.1 % (25.0 %) at 1-year, and 85.8 % (SD = 28.4 %) at 2-year follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Scatterplots of NRS Arm, PRO scores for both pre- and post-injection and Patient reported Percent Relief of Arm pain.

Table 2.

Mixed-effect linear regression model estimated means and change in means from pre-injection to approximate 3-month, 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year post-injection follow-up, and responder and worst-case responder analysis. The worst-case responder analysis was conducted under the assumption that patients who were missing data at the pre- and/or post-injection time point did not improve by the MCID.

| Time | N | Estimated Mean (95 % CI) | Estimated Mean Change From Pre-Injection (95 % CI) |

P-value | Responder (Improved by MCID) Proportion (%) |

Worst-Case Responder Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS Arm (MCID = 2) | Pre-Injection | 217 | 6.89 (6.57, 7.22) | ||||

| 3-month | 163 | 3.21 (2.81, 3.60) | −3.68 (−4.10, −3.27) | <0.001 | 117/163 (71.8 %) | 117/219 (53.4 %) | |

| 6-month | 38 | 3.25 (2.50, 4.02) | −3.64 (−4.40, −2.89) | <0.001 | 27/38 (71.1 %) | 27/219 (12.3 %) | |

| 1-year | 36 | 2.65 (1.92, 3.43) | −4.24 (−5.02, −3.47) | <0.001 | 29/36 (80.6 %) | 29/219 (13.2 %) | |

| 2-year | 17 | 2.30 (1.14, 3.33) | −4.60 (−5.69, −3.50) | <0.001 | 15/17 (88.2 %) | 15/219 (6.8 %) | |

| PHQ-9 (MCID = 5) | Pre-Injection | 97 | 9.01 (7.81, 10.32) | ||||

| 3-month | 77 | 7.01 (5.65, 8.31) | −2.00 (−3.39, −0.62) | 0.005 | 20/71 (28.2 %) | 20/219 (9.1 %) | |

| 6-month | 43 | 6.66 (4.92, 8.21) | −2.35 (−4.07, −0.64) | 0.007 | 9/39 (23.1 %) | 9/219 (4.1 %) | |

| 1-year | 51 | 7.66 (6.15, 9.32) | −1.35 (−2.96, 0.26) | 0.101 | 13/46 (28.3 %) | 13/219 (5.9 %) | |

| 2-year | 29 | 6.95 (5.22, 9.02) | −2.06 (−4.08, −0.04) | 0.046 | 6/25 (24.0 %) | 6/219 (2.7 %) | |

| PROMIS-GH Physical (MCID = 5) | Pre-Injection | 82 | 38.17 (36.43, 39.78) | ||||

| 3-month | 68 | 40.87 (39.25, 42.60) | 2.70 (1.24, 4.16) | <0.001 | 22/63 (34.9 %) | 22/219 (10.0 %) | |

| 6-month | 42 | 40.86 (38.89, 42.73) | 2.69 (0.95, 4.43) | 0.003 | 10/38 (26.3 %) | 10/219 (4.6 %) | |

| 1-year | 51 | 41.69 (39.78, 43.53) | 3.52 (1.90, 5.13) | <0.001 | 18/48 (37.5 %) | 18/219 (8.2 %) | |

| 2-year | 28 | 41.77 (39.44, 44.13) | 3.60 (1.55, 5.64) | <0.001 | 8/25 (32.0 %) | 8/219 (3.7 %) | |

| PROMIS-GH Mental (MCID = 5) | Pre-Injection | 80 | 45.62 (43.60, 47.71) | ||||

| 3-month | 69 | 46.01 (43.91, 48.17) | 0.39 (−1.23, 2.01) | 0.636 | 16/63 (25.4 %) | 16/219 (7.3 %) | |

| 6-month | 43 | 46.39 (44.16, 48.77) | 0.77 (−1.16, 2.71) | 0.432 | 8/38 (21.1 %) | 8/219 (3.7 %) | |

| 1-year | 50 | 45.15 (42.83, 47.30) | −0.47 (−2.30, 1.37) | 0.616 | 8/45 (17.8 %) | 8/219 (3.7 %) | |

| 2-year | 28 | 48.31 (45.78, 50.74) | 2.69 (0.41, 4.97) | 0.021 | 12/25 (48.0 %) | 12/219 (5.5 %) |

CI – confidence interval; MCID – minimal clinically important difference.

Responder analysis revealed that about 71 % of patients improved in NRS arm pain at 3 and 6 months and about 81–88 % of patients improved at the 1-year and 2-year follow-up marks. These percentages are based on patients who had available data at pre-injection and each post-injection time point. Assuming those with missing data did not improve by the MCID (i.e. worst-case analysis), about 53 % would have improved in NRS arm pain at 3-months and about 7–13 % would have improved at the other time points. For the other PROs, about 23%–28 % improved in PHQ-9 score, 26–38 % of patients improved in PROMIS-GH Physical Health, and about 18–48 % of patients improved in PROMIS-GH Mental Health. Worst-case analysis for these other PROs would result in 10 % or fewer patients improving.

Among the 219 included patients, 18 patients never followed up after their first injection and did not have surgery. Among the 201 patients who followed up, 62 (30.8 %) went on to have cervical spine surgery. Median follow-up time for all patients was 181 days (IQR, 67–619; range, 6-2331).

Table 3 shows results of the logistic regression models for short-term (≤3 months) and long-term (>3 months) improvement in NRS arm pain. A total of 163 patients had data for short-term improvement, of which 117 (71.8 %) improved by 2 or more points. A total of 84 patients had data for long-term improvement, of which 64 (76.2 %) improved. For short-term improvement, patients who had a positive response had 1.61 times higher odds of short-term improvement, compared to patients who did not have a positive response (OR = 1.61, 95 % CI = 1.32–1.96, P < 0.001). No other variables were associated with short-term improvement in NRS arm pain. For long-term improvement older age was associated with greater odds of improving in NRS arm pain (10-year OR = 1.11, 95 % CI = 1.03–1.21, P = 0.011), and female sex was associated with lower odds of improvement (OR = 0.80, 95 % CI = 0.66–0.95, P = 0.015). No other variables were associated with long-term improvement in NRS arm pain.

Table 3.

Single-predictor logistic regression model results for short-term (≤3 months) and long-term (>3months) improvement in NRS arm pain by 2 or more points.

| Improvement ≤3 months post-injection (N = 163) |

Improvement >3 months post-injection (N = 84) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.10) | 0.266 | 1.11 (1.03, 1.21) | 0.011 |

| Female (vs. Male) | 1.09 (0.95, 1.25) | 0.216 | 0.80 (0.66, 0.95) | 0.015 |

| Body Mass Index (per 10 units) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.29) | 0.061 | 1.04 (0.88, 1.23) | 0.645 |

| Active Smoker | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) | 0.775 | 0.89 (0.73, 1.09) | 0.257 |

| Symptom Duration (years) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.142 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.073 |

| History Cervical Surgery | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) | 0.680 | 1.00 (0.80, 1.26) | 0.976 |

| History Cervical Interlaminar Injection | 0.96 (0.81, 1.15) | 0.673 | 1.01 (0.82, 1.25) | 0.891 |

| Disk Level (vs. C5–C6) | ||||

| C6–C7,C7-T1 | 1.13 (0.89, 1.44) | 0.316 | 1.02 (0.74, 1.40) | 0.891 |

| C3–C4,C4–C5 | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) | 0.897 | 0.95 (0.69, 1.30) | 0.742 |

| Location Left | 0.96 (0.83, 1.10) | 0.549 | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) | 0.531 |

| Procedure Time (per 10 min) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.02) | 0.120 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.09) | 0.521 |

| Fluoroscopy Time (per 10 min) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.523 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.980 |

| Positive Response | 1.61 (1.32, 1.96) | <0.001 | 1.20 (0.91, 1.59) | 0.205 |

| Cervical Pathology (vs. Disk Herniation) | ||||

| Bony Foraminal Stenosis | 0.88 (0.76, 1.03) | 0.106 | 1.10 (0.90, 1.34) | 0.363 |

| Pseudoarthrosis | 0.87 (0.51, 1.47) | 0.598 | 1.36 (0.73, 2.52) | 0.332 |

| Blood Thinners | 0.91 (0.66, 1.25) | 0.553 | 1.28 (0.78, 2.10) | 0.330 |

| Physical Therapy | 1.08 (0.90, 1.29) | 0.412 | 1.04 (0.79, 1.37) | 0.776 |

| MRI | 0.75 (0.50, 1.12) | 0.156 | 0.78 (0.48, 1.28) | 0.330 |

| CT | 1.00 (0.86, 1.15) | 0.981 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.32) | 0.439 |

| X-ray | 0.90 (0.68, 1.18) | 0.447 | 1.01 (0.66, 1.56) | 0.955 |

| EMG | 0.96 (0.83, 1.10) | 0.559 | 1.03 (0.85, 1.24) | 0.771 |

| Time since Provider's 1st Injection (per year) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 0.120 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.270 |

CI – confidence interval.

4. Discussion

One of the aims of this study was to evaluate the improvement in pain relief after CTFESI. The effectiveness of CTFESIs in treating cervical radicular pain has been examined previously in a review by Engel [9] in 2014. These authors concluded that the evidence after CTFESI provided short-term relief of radicular pain and limited evidence of long-term benefit. While some patients may experience pain relief, the evidence was of very low quality according to the GRADE criteria, especially as the follow-up time periods increased. In that study, they also reviewed the literature for complications of the procedure and concluded that the evidence at that time did not support the use of CTFESIs. They called for future research and stated that future studies would likely change their presented conclusions. A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis [8] in 2020 concluded that about half of patients can expect to have at least 50 % pain relief for up to 3 months. The same review reported CTFESI using non-particulate steroids reduction of pain scores by ≥ 50 % was estimated at 56 % at 1 month and 68 % at 3 months. Other studies reported relief at 6 and 12 months, but were excluded from this analysis due to inadequate technique description, non-standard technique, or failure to utilized contrast imaging. This updated systematic review and meta-analysis deemed the quality of evidence for pain relief after CTEFSI as very low using the GRADE criteria.

Our data is consistent with previous studies showing that patients following CTFESI can achieve pain relief in the short-term. Similar to other studies, significant improvement in pain based on NRS, did not differ based on pathology due to spondylosis or disc herniation. We also found that older age was associated with greater reduction in pain after CTFESI, similar to Kumar and Gowda [20],. In contrast to the existing literature this cohort reports long-term pain relief greater than one year and achieving MCID after CTESI in those patients who provided long-term follow up. We believe utilizing a standardized technique with peri-neural needle placement may account for our responder rates.

We also analyzed patient-reported outcomes on functional status metrics as collected by patient-completed survey data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of CTFESIs on patient quality of life measures using PHQ9 and PROMIS-GH. Previous studies have often used the Neck Disability Index (NDI) to evaluate functional status and shown improvement following CTFESI [8,[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. The NDI is used to measure patient-reported disability specific to neck pain [22,23], however, NDI is not collected at our institution. The surveys used in our study provide insight into the patient's self-perceived disability level, depression, and health-related quality of life, respectively. This trend suggests that patients not only receive pain relief from their injections, but also improve their functional quality of life. We hope these findings help future researchers better understand the use of these instruments in the assessment of cervical radiculopathy.

There have been cases documenting potentially serious complications associated with CTFESIs, many of which are thought to be due to the intravascular uptake of injected steroid, leading to brain and spinal cord infarction events [10]. While not the original objective of our study, it is worth noting that, while no patients experienced cerebrovascular accidents, one patient in this cohort had the procedure aborted due to a seizure with no long term sequalae. A case series in 2007 investigating selective cervical nerve root blocks described a single case of a grand mal seizure following intervention; the patient's seizure lasted 3–4 min and he experienced full recovery within 30 min [24]. Another case report in 2011, described seizure-like activity following accidental injection of lidocaine into the vertebral artery [25]. While we are unsure of the etiology in our study, it is possible that a similar mechanism occurred. No other complications were reported in our cohort of patients. Since the single complication, our technique was altered with a lower dose of lidocaine from 2 % to 0.5 % and no manipulation of extension tubing once no vascular flow was visualized on digital subtraction angiography. It is imperative to employ risk mitigation strategies including use of non-particulate steroid, extension tubing, live fluoroscopy, and DSA (digital subtraction angiography) also described as digital subtraction imaging (DSI) [11,26,27]. The use of DSA is the safest way to minimize risk, but not completely protective against complications such as seizure, stroke, spinal cord injury, or death [9,11].

A recent retrospective review by Levin et al., noted that patients referred by a spine provider who performs CTESI compared to a non-interventionalist had better pain relief outcomes as defined by >80 % pain reduction with a mean follow up of 21 days [28]. We observed that approximately 25–30 % of our patients proceeded to spinal surgery before the close of our study period. The only factor that was associated with increased surgery rates in our population was prior cervical spinal surgery. In our patients who had a history of cervical spine surgery (fusion or no fusion), there was an increased tendency for referral from spine surgery compared to medical spine.

The retrospective study design under a single provider cohort may limit our results. We chose a single provider and institution approach to our analysis to limit procedure variability. The retrospective nature of this study led to non-standardized follow-up time points. When using patient survey data retrospectively, it is inevitable that some patients will have incomplete data recorded resulting in exclusion from analysis. This was certainly the case with our data, where large proportions of patients were missing scores at follow-up time points, particularly those beyond 3-months after their most recent injection. The results of our analysis should be interpreted with caution. In addition, our cohort included patients who travel vast distances and may have had follow-up closer to home and were missing follow-up using our patient reported outcome measures. Future prospective studies with standardized follow-up and strategies to mitigate missing data are warranted. Since our data was based on chart review, we may have missed cervical spine surgery performed outside our health system. Finally, the follow-up period represents a period longer than what is expected for corticosteroid response. Therefore, sustained benefit may relate to other factors or management, such as physical therapy, psychological support, use of oral analgesics, all of which are difficult to account for in a retrospective study, although all patients were managed with usual care. Finally, therapeutic effectiveness or efficacy cannot be inferred from the temporal relationship after CTFESI.

5. Conclusion

This study suggests that patients receiving CTFESIs for cervical radiculopathy report improvements in pain relief and function following intervention. These findings warrant future prospective, multi-institutional investigation to gain a more applicable understanding of long-term pain relief and function after CTFESIs.

Disclosures

T.J. Kristoff reports no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; J.T. Sinopoli has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; M. Abbott has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; N.R. Thompson has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; H Koech reports no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; N. Rabah has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; KK. Goyal reports no disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

Study funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Cleveland Clinic Foundation's NI Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation, Section of Biostatistics for their statistical support, the Cleveland Clinic Foundation's Knowledge Program Data Registry for collection of patient surveys, and The Cleveland Clinic Foundation's Spine Research Study Group for supporting this research endeavor.

References

- 1.Murray C.J.L., Mokdad A.H., Ballestros K., et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319(14):1444–1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radhakrishnan K., Litchy W.J., O’fallon W.M., Kurland L.T. Minnesota; 1994. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy: a population-based study from Rochester. 1976 through 1990. Brain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saal J.S., Saal J.A., Yurth E.F. Nonoperative management of herniated cervical intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. Spine. 1996 doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honet J.C., Puri K. Cervical radiculitis: treatment and results in 82 patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson A., Hao J., Sjölund B. Local corticosteroid application blocks transmission in normal nociceptive C‐fibres. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1990.tb03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberman A.C., Druker J., Garcia F.A., Holsboer F., Arzt E. Annals of the New York academy of sciences. 2009. Intracellular molecular signaling: basis for specificity to glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory actions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzon H.T., Huntoon M.A., Rathmell J.P. Improving the safety of epidural steroid injections. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conger A., Cushman D.M., Speckman R.A., Burnham T., Teramoto M., McCormick Z.L. The effectiveness of fluoroscopically guided cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injection for the treatment of radicular pain; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2020;21(1):41–54. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel A., King W., MacVicar J. Standards Division of the International Spine Intervention Society. The effectiveness and risks of fluoroscopically guided cervical transforaminal injections of steroids: a systematic review with comprehensive analysis of the published data. Pain Med. 2014 Mar;15(3):386–402. doi: 10.1111/pme.12304. Epub 2013 Dec 5. PMID: 24308846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malhotra G., Abbasi A., Rhee M. Complications of transforaminal cervical epidural steroid injections. Spine. 2009 Apr 1;34(7):731–739. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318194e247. PMID: 19333107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kupperman W., Goyal K.K. Image-guided cervical injections with most updated techniques and society recommendations. Adv Clin Radiol. 2022;4(1):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.yacr.2022.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogduk N. Practice guidelines for spinal diagnostic and treatment procedures. second ed. International Spine Intervention Society; San Francisco: 2013. Sacral procedures; pp. 655–684. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. PMID: 11556941; PMCID: PMC1495268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cella D., Yount S., Rothrock N., Gershon R., Cook K., Reeve B., et al. PROMIS cooperative Group. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007 May;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. PMID: 17443116; PMCID: PMC2829758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs F.M., Abraira V., Royuela A., et al. Minimum detectable and minimal clinically important changes for pain in patients with nonspecific neck pain. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2008;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2018. R: a language and environment for statistical computing.http://www.R-project.org/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J.H., Lee S.H. Comparison of clinical effectiveness of cervical transforaminal steroid injection according to different radiological guidances (C-arm fluoroscopy vs. computed tomography fluoroscopy) Spine J. 2011 May;11(5):416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.04.004. PMID: 21558036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persson L., Anderberg L. Repetitive transforaminal steroid injections in cervical radiculopathy: a prospective outcome study including 140 patients. Evid Base Spine Care J. 2012 Aug;3(3):13–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327805. PMID: 23531493; PMCID: PMC3592766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jee H., Lee J.H., Kim J., Park K.D., Lee W.Y., Park Y. Ultrasound-guided selective nerve root block versus fluoroscopy-guided transforaminal block for the treatment of radicular pain in the lower cervical spine: a randomized, blinded, controlled study. Skeletal Radiol. 2013 Jan;42(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1434-1. Epub 2012 May 20. PMID: 22609989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar N., Gowda V. Cervical foraminal selective nerve root block: a 'two-needle technique' with results. Eur Spine J. 2008 Apr;17(4):576–584. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0600-6. Epub 2008 Jan 18. PMID: 18204941; PMCID: PMC2295277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim E., Chotai S., Schneider B.J., Sivaganesan A., McGirt M.J., Devin C.J. Effect of depression on patient-reported outcomes following cervical epidural steroid injection for degenerative spine disease. Pain Med. 2018;19(12):2371–2376. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernon H., Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1991 Sep;14(7):409–415. Erratum in: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992 Jan;15(1). PMID: 1834753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young I.A., Cleland J.A., Michener L.A., Brown C. Reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness of the neck disability index, patient-specific functional scale, and numeric pain rating scale in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Oct;89(10):831–839. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181ec98e6. PMID: 20657263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schellhas K.P., Pollei S.R., Johnson B.A., Golden M.J., Eklund J.A., Pobiel R.S. Selective cervical nerve root blockade: experience with a safe and reliable technique using an anterolateral approach for needle placement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007 Nov-Dec;28(10):1909–1914. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0707. Epub 2007 Sep 28. PMID: 17905892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung S.G. Convulsion caused by a lidocaine test in cervical transforaminal epidural steroid injection. PMR. 2011 Jul;3(7):674–677. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.02.005. PMID: 21777868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreyfuss P., Baker R., Bogduk N. Comparative effectiveness of cervical transforaminal injections with particulate and nonparticulate corticosteroid preparations for cervical radicular pain. Pain Med. 2006 Jun;7(3):237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levin J., Mohan M., Levi D., Horn S., Smuck M. Incidence of extravascular Perivertebral artery contrast flow during cervical Transforaminal epidural injections. Pain Med. 2020 Sep;21(9):1753–1758. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin J., Gall N., Chan J., Huynh L., Koltsov J., Kennedy D.J., Smuck M. Results of cervical epidural steroid injections based on the physician referral source. Intervent Pain Med. Dec. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.inpm.2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]