Abstract

Objectives

Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is a relatively well known complication that has been observed for a long time. Though the management and drugs in the perioperative period have changed, their impact on the generation of postoperative atrial fibrillation remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated various perioperative management methods and the occurrence of postoperative atrial fibrillation.

Methods

The patients underwent off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting between January 2010 and October 2019. The study was a retrospective observational study, and we investigated the incidence of atrial fibrillation during all 5 postoperative days. Patient factors included age, sex, height, and weight, preoperative factors included oral statin, HbA1c, left ventricular ejection fraction, and left atrial diameter; intraoperative factors included operation time, remifentanil use, beta-blocker use, magnesium-containing infusions use, in–out balance, and number of vascular anastomoses.

Results

Postoperative atrial fibrillation was recognized in 81 out of 276 cases. There were significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, left atrial diameter, and intraoperative remifentanil use. A logistic regression analysis presented the effects of age (OR 1.045, 95% CI 1.015–1.076, P < 0.01), preoperative left atrial diameter (OR 1.072, 95% CI 1.023–1.124, P < 0.01), and intraoperative remifentanil use (OR 0.492, 95% CI 0.284–0.852, P = 0.011) on postoperative atrial fibrillation.

Conclusions

Operative time did not affect postoperative atrial fibrillation. Age and left atrial diameter had previously been shown to affect postoperative atrial fibrillation, and our results were similar. This study showed that the use of remifentanil reduced the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. On the other hand, no other factors were found to have an effect.

Keywords: Coronary artery bypass surgery, Atrial fibrillation, Remifentanil

1. Introduction

A trial fibrillation is a type of arrhythmia that occurs frequently after cardiac surgery [1]. Postoperative atrial fibrillation has been reported to occur at a rate as high as 15–40% after coronary artery bypass surgery [2,3]. Studies suggest that the use of extracorporeal circulation does not affect the incidence of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery [4,5]. However, the situation is different from before, as surgery times are shorter and intraoperative remifentanil and magnesium-containing infusion products are used. On the other hand, how these changes may contribute to the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation remains unclear. To address this gap, we investigated the incidence of atrial fibrillation and the influence of perioperative management after off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection

We enrolled patients who underwent standby off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery at our hospital between January 2010 and October 2019, were not on dialysis and did not have atrial fibrillation.

2.2. Method

This was a retrospective observational study. Patients had continuous electrocardiogram monitoring for five postoperative days, and all arrhythmias were documented in medical records. The incidence of atrial fibrillation during all five postoperative days was extracted from the medical records. Only the occurrence of atrial fibrillation was studied. (The duration of atrial fibrillation was not studied.) We also collected data regarding patient factors such as age, sex, height, and weight; preoperative factors such as statin use, HbA1C level, left ventricular ejection fraction, and left atrial diameter; and intraoperative factors such as remifentanil use, use of infusions containing magnesium, beta blocker use, IN–OUT balance, number of anastomotic sites, operative time, and anesthesia time.

2.3. Statistical analysis

To compare the two groups, we performed the unpaired t-test, Mann–Whitney’s U-test, and Chi-square for independence test after examining the normality of the data. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine associations. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel 2010 (Microsoft, USA) with the add-in software Statcel 2 (OMS, Japan) and IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0 (IBM, USA).

2.4. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiga University of Medical Science [Approval No: R2019-275]. Since this study adopted a retrospective research method, informed consent was obtain in the form of opt-out on the web-site.

3. Results

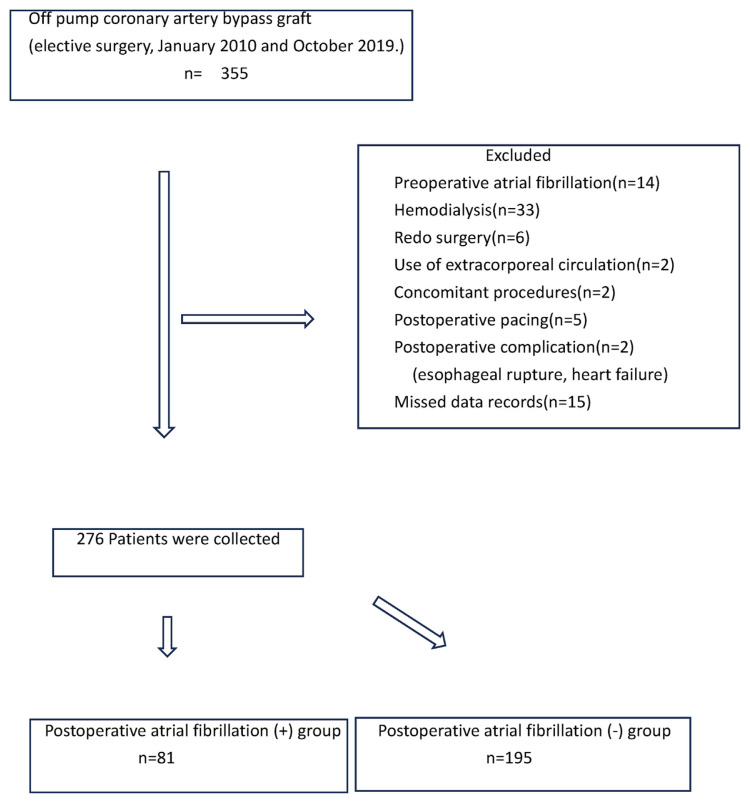

Patient characteristics: A total of 276 patients were included after the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied. Of them, 195 patients did not develop postoperative atrial fibrillation, whereas the remaining 81 patients developed postoperative atrial fibrillation (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Comparison of the two groups: A comparison of patient and operative characteristics between the patients with and without atrial fibrillation is presented in Table 1. There were significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, preoperative left atrial diameter, and intraoperative remifentanil use. There was no significant difference in any of the other factors (Table 1). A logistic regression analysis with postoperative atrial fibrillation as the dependent variable and each factor as the independent variable further demonstrated significant associations for age (odds ratio (OR): 1.045, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.015–1.076, p < 0.01), preoperative left atrial diameter (OR: 1.072 95% CI: 1.023–1.124, p < 0.01), and remifentanil use (OR: 0.492, 95% CI: 0.284–0.852, p = 0.011) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline data and perioperative findings.

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation (+) | Postoperative atrial fibrillation (−) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Yr) | 72 (66–77) | 69 (60.5–74) | 0.007 |

| Sex (male) | 68 (84.0%) | 158 (81.0%) | 0.566 |

| Height (cm) | 165 (157.3–169) | 163.2 (157.2–169) | 0.49 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.1 ± 13.6 | 62.1 ± 10.8 | 0.512 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.4 (5.9–7.2) | 6.4 (5.9–7.2) | 0.773 |

| Preoperative left atrial diameter (mm) | 40.1 (36.3–44.1) | 38.1 (35.4–41.6) | 0.006 |

| Preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 57 (49–61) | 59 (47–65) | 0.415 |

| Preoperative Statin use (n) | 52 | 141 | 0.181 |

| Operative time (min) | 239.8 ± 61.6 | 227.1 ± 60.5 | 0.115 |

| Intraoperative remifentanil use (n) | 40 | 123 | 0.035 |

| Intraoperative β-blocker use (n) | 14 | 36 | 0.817 |

| Intraoperative Magnesium-containing infusions use (n) | 17 | 32 | 0.365 |

| Intraoperative In–Out balance (mL) | 3547 (2512–4115) | 3322 (2590–4100) | 0.598 |

| Intraoperative number of anastomotic sites (n) | 4 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 0.224 |

Table 2.

Factors associated with the incidence of Atrial fibrillation in both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| OR | 95%CI | P | OR | 95%CI | P | |

| Sex (male) | 1.225 | 0.613–2.449 | 0.566 | 1.233 | 0.587–2.588 | 0.581 |

| Age | 1.038 | 1.010–1.067 | 0.007 | 1.045 | 1.015–1.076 | 0.003 |

| Preoperative left atrial diameter | 1.067 | 1.021–1.115 | 0.004 | 1.072 | 1.023–1.124 | 0.004 |

| Remifentanil use | 0.571 | 0.338–0.964 | 0.036 | 0.492 | 0.284–0.852 | 0.011 |

4. Discussion

Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery is a common postoperative arrhythmia and has long been considered a clinical issue. It complicates postoperative management due to hemodynamic instability and may lead to complications such as cerebral infarction and prolonged ICU stay [4,6], although the latter claim has not been conclusively proven [7]. Conventional coronary artery bypass surgery has been associated with a high rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation (15–40%). Although the surgical technique has been revised to forego the use of a heart-lung machine, some suggest that the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation is not affected by the use of a heart-lung machine [4,5,8]. In general, old age, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are considered risk factors for postoperative atrial fibrillation [9]. Over time, surgical techniques have improved significantly, and this has resulted in reduced operative time. Notably, perioperative management practices have also changed; for example, many patients are now administered preoperative statins, and some remain on statins up until surgery. The use of remifentanil in cardiac surgical anesthesia has also been on the rise. Magnesium has long been used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation, and the intraoperative use of magnesium-containing infusions have become more common. In some cases, intraoperative short-acting β-blockers are used when needed. However, whether these perioperative changes alter the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation has been unclear.

Our data showed that postoperative atrial fibrillation occurred in 29.3% (81/276) of patients. This incidence rate is in accordance with previous studies [2,3]. We further demonstrated that the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation was associated with age, left atrial diameter, and intraoperative use of remifentanil. The use of magnesium-containing infusion products, which was expected to be beneficial, was found to have no significant impact. While previous studies demonstrated that magnesium is effective in suppressing postoperative atrial fibrillation [10,11], some indicated that further studies are needed [9]. Although a variety of infusions containing magnesium are available, the amount of Mg [2+]contained in infusions is about 2 mEq/L. Our findings indicate the need to reconsider total infusion volume in future studies. β-blockers are commonly used to treat atrial fibrillation, and their use during the perioperative period is believed to be effective in suppressing postoperative atrial fibrillation. While these studies administered β-blockers for several days [12], we demonstrated that intraoperative use of β-blockers for a very short period of time had no suppressive effect on atrial fibrillation. β-blockers must be used carefully as the perioperative use of β-blockers has been associated with an elevated risk of cerebral infarction [13]. Statins have various pharmacological effects, such as anti-inflammation and plaque reduction and stabilization. They are often taken perioperatively without cessation. Although statins were initially thought to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation [14,15], a subsequent large study demonstrated that it had negative effects including a risk to renal function [16,17]. Our results indicated that the use of statins had no effect on postoperative atrial fibrillation.

We demonstrated that the use of remifentanil may reduce the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Remifentanil has analgesic properties, and it has been previously indicated to suppress inflammatory responses [18]. This anti-inflammatory effect may have suppressed the occurrence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. However, remifentanil has also been associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia, and postoperative pain augmentation may excite the sympathetic nervous system, contributing to the development of atrial fibrillation [19,20]. Thus, remifentanil use should be carefully considered.

This study had certain limitations. First, we examined the effect of drugs and infusions based on their use and did not examine the dose or the duration of administration. Future studies should evaluate the dose and duration of administration.

Second, all patients with atrial fibrillation listed in the medical record were included in the study, and the need for treatment was not considered. Previous studies also did not include clear distinction. Thus, future studies should be developed based on the discussion on how to define atrial fibrillation. Third, old data was used in this study. It is necessary to incorporate new data in the future.

Our findings suggest that the anti-inflammatory effect of remifentanil could suppress atrial fibrillation. This raises a question as to whether other anti-inflammatory drugs such as dexmedetomidine and remimazolam would also have similar effects [21,22]. In Japan, remifentanil was approved for use in postoperative ICU settings in 2023. The effect of long-term use of remimazolam and remifentanil on postoperative atrial fibrillation is currently unknown.

5. Conclusions

Intraoperative use of remifentanil may be effective in reducing the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Future studies are needed to determine appropriate dosage and its combination with other drugs.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions: Conception and design of Study: YI, HK. Literature review: YI, SH, MI, TM, MO. Acquisition of data: YI, SH, MI, TM, MO. Analysis and interpretation of data: YI, HK. Research investigation and analysis: YI, SH, MI, TM, MO. Data collection: YI, SH, MI, TM, MO. Drafting of manuscript: YI, HK. Revising and editing the manuscript critically for important intellectual contents: YI, SH, HK. Data preparation and presentation: YI, MO. Supervision of the research: YI, HK. Research coordination and management: YI, HK. Funding for the research: YI, HK.

Disclosure of funding: All authors receive no funding.

References

- 1. Maisel WH, Rawn JD, Stevenson G. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:1061–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-12-200112180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. El-Chami MF, Kilgo P, Thourani V, Lattouf OM, Delurgio DB, Guyton RA, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rollo P. Postoperative atrial fibri llation and Mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:742–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hossein G. Predictors and impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on patinets’outcomes:A report from the Randomized on versus off Bypass trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andre L. Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1489–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Almassi GH, Schowalter T, Nicolosi AC, Aggarwal A, Moritz TE, Henderson WG, et al. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a major morbid event? Ann Surg. 1997;226:501–11. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen L, Dai W. Effects of short-term episodes of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting on the long-term incidence of atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke. Heart Surg Forum. 2024;27:E014–9. doi: 10.59958/hsf.6787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arslan G. The incidence of atrial fibrillation after on-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Heart Surg Forum. 2021;24:E645–50. doi: 10.1532/hsf.3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Omae T, Inada E. New-Onset atrial fibrillation : an update. J Anesth. 2018;32:414–24. doi: 10.1007/s00540-018-2478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller S. Effects of magnesium on atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2005;91:618–23. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.033811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgess DC. Interventions for prevention of post-operative atrial fibrillation and its complications after cardiac surgery:a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2846–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tamura T, Yatabe T, Yokoyama M. Prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery using low-dose landiolol: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2017;42:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bangalore S, Wetterslev J, Pranesh S, Sawhney S, Gluud C, Messerli GF. Perioperative β blockers in patients having non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;372:1962–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mariscalco G, Lorusso R, Klersy C, Ferrarese S, Tozzi M, Vanoli D, et al. Observational study on the beneficial effect of preoperative statins in reducing atrial fibrillation after coronary surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Winchester DE, Wen X, Xie L, Bavry AA. Evidence of pre-procedural statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1099–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zheng Z, Jayaram R, Jiang L, Emberson J, Zhao Y, Li Q, et al. Prioperative rosuvastatin in cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1744–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Putzu A, Capelli B, Belletti A, Cassina T, Ferrari E, Gallo M, et al. Perioperative statin therapy in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2016;20:395. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasegawa A, Iwasaka H, Hagiwara S, Hasegawa R, Kudo K, Kusaka J, et al. Remifentanil and glucose suppress inflammation in a rat model of surgical stress. Surg Today. 2011;41:1617–21. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4457-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santonocito C, Noto A, Crimi C, Sanfilippo F. Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia: current perspectives on mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:15–23. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S143618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Hoogd S, Ahlers SJGM, van Dongen EPA, van de Garde EMW, Daeter EJ, Dahan A, et al. Randomized controlled trial on the influence of intraoperative remifentanil versus fentanyl on acute and chronic pain after cardiac surgery. Pain Pract. 2018;18:443–51. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S143618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang K, Wu M, Xu J, Wu C, Zhang B, Wang G, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on perioperative stress, inflammation, and immune function: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:777–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu X, Lin S, Zhong Y, Shen J, Zhang X, Luo S, et al. Remimazolam protects against LPS-induced endotoxicity improving survival of endotoxemia mice. Front Pharmacol. 2021:12. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.739603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]