Abstract

SETTING

Daru Island in Papua New Guinea (PNG) has a high prevalence of TB and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the early implementation of a community-wide project to detect and treat TB disease and infection, outline the decision-making processes, and change the model of care.

DESIGN

A continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiative used a plan-do-study-act (PDSA) framework for prospective implementation. Care cascades were analysed for case detection, treatment, and TB preventive treatment (TPT) initiation.

RESULTS

Of 3,263 people screened for TB between June and December 2023, 13.7% (447/3,263) screened positive (CAD4TB or symptoms), 77.9% (348/447) had Xpert Ultra testing, 6.9% (24/348) were diagnosed with TB and all initiated treatment. For 5–34-year-olds without active TB (n = 1,928), 82.0% (1,581/1,928) had tuberculin skin testing (TST), 96.1% (1,519/1,581) had TST read, 23.0% (350/1,519) were TST-positive, 95.4% (334/350) were TPT eligible, and 78.7% (263/334) initiated TPT. Three PDSA review cycles informed adjustments to the model of care, including CAD4TB threshold and TPT criteria. Key challenges identified were meeting screening targets, sputum unavailability from asymptomatic individuals with high CAD4TB scores, and consumable stock-outs.

CONCLUSION

CQI improved project implementation by increasing the detection of TB disease and infection and accelerating the pace of screening needed to achieve timely community-wide coverage.

Keywords: continuous quality improvement, TB, community, PDSA framework

Abstract

CONTEXTE

L'île de Daru en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée (PNG) présente une forte prévalence de la TB et de la TB multirésistante (MDR-TB).

OBJECTIF

Évaluer la mise en œuvre précoce d'un projet à l'échelle de la communauté pour détecter et traiter la TB et l'infection, décrire les processus de prise de décision et changer le modèle de soins.

CONCEPTION

Une initiative d'amélioration continue de la qualité (CQI, pour l’anglais « continuous quality improvement ») a utilisé un cadre de planification, d'action, d'étude, d'action (PDSA, pour l’anglais «plan-do-study-act ») pour la mise en œuvre prospective. Les cascades de soins ont été analysées pour la détection des cas, le traitement et l'initiation du traitement préventif de la TB.

RÉSULTATS

Sur 3 263 personnes dépistées pour la TB entre juin et décembre 2023, 13,7% (447/3 263) ont été dépistées positives (CAD4TB ou symptômes), 77,9% (348/447) ont subi un test Xpert Ultra, 6,9% (24/348) ont reçu un diagnostic de TB et toutes ont commencé un traitement. Chez les 5 à 34 ans sans TB active (n = 1 928), 82,0% (1 581/1 928) ont subi un test cutané à la tuberculine (TCT), 96,1% (1 519/1 581) ont eu un test de dépistage du TCT, 23,0% (350/1 519) étaient positifs au TCT, 95,4% (334/350) étaient éligibles au TPT et 78,7% (263/334) ont initié le TPT. Trois cycles d'examen PDSA ont permis d'ajuster le modèle de soins, y compris le seuil CAD4TB et les critères TPT. Les principaux défis identifiés étaient l'atteinte des objectifs de dépistage, l'indisponibilité des expectorations chez les personnes asymptomatiques avec des scores CAD4TB élevés et les ruptures de stock de consommables.

CONCLUSION

L'ACQ a amélioré la mise en œuvre du projet en augmentant la détection de la TB et de l'infection et en accélérant le rythme de dépistage nécessaire pour atteindre une couverture à l'échelle de la communauté en temps opportun.

TB remains a global public health crisis, with an estimated 1.3 million TB-related deaths in 2022.1 Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a low-middle-income country classified as a high-burden country for TB and multidrug/rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) by the World Health Organization (WHO). In 2014, an unprecedented outbreak of MDR/RR-TB in Daru, South Fly District, Western Province, triggered a coordinated emergency response led by the PNG National Department of Health and Western Provincial Health Authority (WPHA).2,3 The TB case notification rate for South Fly District in 2022 was 693/100,000, and TB was hyperendemic in Daru (2,170/100,000) (WPHA reports). The proportion of MDR/RR-TB in South Fly District is approximately 20% of all TB diagnoses, higher than other settings in PNG.3–5

In 2015, a community-based model of care for TB detection and treatment, including MDR/RR-TB, was introduced in Daru, improving treatment outcomes and stabilising case notifications.3 Key interventions included community engagement, WHO-recommended rapid diagnostics (Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert Ultra), new MDR-TB treatment regimens, a person-centred model of care, and enhanced data for decision-making. In 2017, screening and management of household contacts of TB cases were introduced, including TB preventive treatment (TPT) for well young children (<5 years) contacts of people with drug-susceptible (DS) TB. In 2019, TPT was introduced for child contacts of people with MDR/RR-TB.6 Despite progress, community transmission of TB in Daru, including MDR/RR-TB, continues,3,7 necessitating interventions to reduce transmission.

In 2023, following disruptions to TB services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the WPHA and partners commenced a comprehensive community-wide strategy, the Systematic Island-Wide Engagement & Elimination Project for TB (SWEEP-TB) or Yumi Bung Wantaim Na Rausim TB Long Daru (Let’s Work Together to End TB in Daru.8 Under an operational research framework, this public health intervention aims to reduce TB incidence in Daru by combining the detection and treatment of TB disease and infection, including MDR-TB. The assessment will use routine surveillance and notification data comparing the age-related burden of TB and MDR-TB between the 24-month pre-intervention and the 24-month post-intervention period.

High screening, treatment, and TPT uptake and treatment completion rates are critical for effectiveness. We aimed to evaluate the early implementation of SWEEP-TB Daru using a CQI initiative. A PDSA framework and TB case detection and prevention cascades were utilised9,10 to monitor progress, identify gaps, and adjust the model of care.11–14

METHODS

Study design

This prospective implementation study has two components: a CQI initiative using a PDSA framework and a care cascade evaluation of TB case detection, treatment, and TPT uptake for SWEEP-TB Daru participants. The study was conducted from May to December 2023 on Daru Island in the South Fly District of the Western Province of PNG.

Study setting and population

Daru is an island with an estimated population of 19,397⋀15. Residents live in overcrowded conditions with a crude population density of 2,500 persons/km2 and an average household size of 7.5.15 The WPHA leads the TB programme in Western Province with support from the National TB Program (NTP) and partners. Daru General Hospital is the only facility in the South and Middle Fly Districts that provides diagnosis and treatment services for MDR-TB. It has a 40-bed inpatient unit and one ambulatory TB clinic. Four community-based treatment centres at each ward on the island are staffed by nurses, community health workers, treatment supporters, and peer counsellors to provide community-based TB care.16 The study population was all Daru residents planning to live on the island for at least 12 months from household enumeration.

Study procedures

The SWEEP-TB team conducted community-based engagement, screening, diagnostic, and prevention activities, data collection and management, and associated procurement and logistics. This team was integrated into the routine TB program, which provides treatment and care for active TB and household contact investigation and management. Routine systems were used for TB drug supply, laboratory diagnostics, and surveillance, as described elsewhere.3

A Community Advisory Group (CAG), self-named TB Nanito Kopia Kodu (the Voice to Kill TB Forever) with members representing key stakeholder groups: churches, schools, businesses, and key populations, provided community input and co-design for TB public health activities, including developing community education materials and advising on optimising acceptability, coverage, and inclusion of the intervention.8 Before implementation, an extensive community engagement and education campaign was conducted to improve foundational knowledge of TB transmission, infection, and disease and to explain the screening and prevention activities in SWEEP-TB. The study had an inclusion framework for people with disabilities, pregnant women, and children.

Household mapping and enumeration were conducted in the pre-implementation phase to geolocate households and elicit household details, including the number of people to be screened. Further information and education, including details of the model, were provided.

Screening was conducted in wards, the smallest administrative unit of government. In each ward, permission and support of ward leaders were obtained. A mobile TB case-finding clinic was deployed at multiple sites in each ward and included stations for education, screening, digital chest X-ray (CXR), clinical assessment, TPT, and vaccination. An innovative model of care was implemented using symptom screening, mobile digital CXR with computer-aided detection for TB (CAD4TB v6, Delft Imaging Systems, Netherlands), Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (GeneXpert, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, USA), tuberculin skin testing (TST), and TPT for both DS and MDR/RR-TB strains using a novel combination regimen of six months of daily isoniazid and levofloxacin (6HLfx).16 Participants who screened positive underwent clinical evaluation at the SWEEP site and, if required, were referred to the diagnostic clinic at the hospital for diagnosis, including testing with Xpert Ultra. People diagnosed with active TB were started on treatment. Young child (<5 years) contacts without TB were offered TPT based on the susceptibility pattern of the index case as per the routine TB program. Persons aged 5–34 years with infection (TST positive) but not disease were offered a TPT regimen of 6HLfx. Those without evidence of TB disease or infection were offered Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination (BCG) if not previously vaccinated.

Person-centred TPT care was provided. Education and counselling were delivered by trained peers (TB survivors).16 Participants on TPT were provided medication for self-administration and reviewed monthly in clinics. An active drug safety and monitoring system was established for the novel TPT regimen. Participants were reimbursed K20 (∼USD 5) for participating in screening and K60 (∼USD 15) for completing a TPT course. Standard operating procedures for the model of care were developed and adjusted throughout implementation. Verbal consent was obtained for screening. Written consent was obtained for participants eligible for TST and TPT. Consent was sought from guardians of children under 18 years, with assent from children aged 8–17 years.

Four CQI cycles based on a PDSA framework were conducted during the study period. These involved regular review meetings with real-time reporting of TB cases and prevention cascades to monitor progress, followed by a facilitated discussion and feedback from the implementation team to identify strengths and bottlenecks and adjust the implementation of the model of care accordingly.

Data collection and analysis

Data used for TB cascades were collected on paper-based forms and entered into an electronic medical records system (EMRS, Bahmni v.0.86; ThoughtWorks, Chicago, IL, USA).

Data were extracted from the EMRS system and analysed using R version 4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria). Demographic and clinical characteristics of people screened and diagnosed with active TB disease and TB infection were described as categorical variables by frequency and proportion.

TB case detection cascades during the study period were calculated using proportions based on numbers: 1) of participants who were screened; 2) who screened positive (symptoms, CAD4TB score >40, severe acute malnutrition); 3) who had diagnostic evaluation (sputum for Xpert Ultra assay); 4) diagnosed with active disease, and 5) initiated on treatment. TB prevention cascades reported on numbers: 1) of participants who were Daru residents aged 5–34 years without active TB (screened negative or who had active TB excluded after screening positive); 2) who had TST administered; 3) of TST read; 4) of TST positive; 5) eligible for TPT; and 6) initiated TPT. The proportion for each step was based on the denominator from the previous step and expressed as a percentage.

A standard template captured key discussions, actions, and changes to the model of care during PDSA cycle review meetings. Operational and implementation issues are documented in an issues tracker (Microsoft Excel) in real time using thematic categories—screening and diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. The PDSA cycle was described according to the four cycles. Changes to the model of care were described using the thematic categories.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the PNG Medical Research Advisory Committee (MRAC 22.04) and the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (568/22).

RESULTS

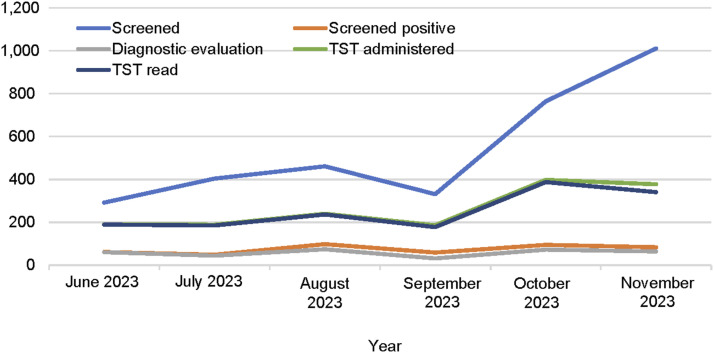

In Daru, 3,263 community participants were screened for TB from June to November 2023. The number screened represents 14.8% of the 22,099 people enumerated during island-wide household mapping. Participant characteristics for 3,159 with complete data (Table 1) were 51% female, 58% aged 5–34 years, and 97% had received BCG. A history of TB contact was reported by 13%, and previous TB treatment and TPT were reported by 9% and 1%, respectively. The number of participants screened per month increased from 292 in June to 1,011 in November (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants screened in the community during SWEEP-TB Daru, June to November 2023.

| Characteristic | (n = 3,159)* |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1,607 (51) |

| Male | 1,552 (49) |

| Age group, years | |

| 0–4 | 402 (13) |

| 5–14 | 825 (26) |

| 15–24 | 522 (17) |

| 25–34 | 474 (15) |

| 35–54 | 665 (21) |

| 55+ | 266 (8) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.2) |

| Nutritional assessment | |

| Normal | 1,850 (59) |

| Moderate | 290 (9.2) |

| Severe | 10 (1.0) |

| Overweight | 219 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 734 (23) |

| BCG vaccination | |

| Yes | 3,080 (97) |

| No | 16 (1) |

| Unknown | 63 (2) |

| History of TB treatment | |

| Yes | 268 (9) |

| No | 2,844 (90) |

| Unknown | 47 (1) |

| History of TPT | |

| Yes | 37 (1) |

| No | 3,037 (96) |

| Unknown | 85 (3) |

| Contact with known case | |

| Yes | 418 (13) |

| No | 2,741 (87) |

| Reported one or more symptoms | |

| Yes | 328 (10) |

| No | 2,831 (90) |

Excludes 104 participants with incomplete data entry at the time.

SWEEP-TB = Systematic Island-Wide Engagement & Elimination Project for TB; BCG = bacille Calmette-Guerin; TPT = TB preventive therapy.

FIGURE 1.

Implementation of SWEEP-TB Daru activities by month, June–November 2023. SWEEP-TB = Systematic Island-Wide Engagement & Elimination Project for TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

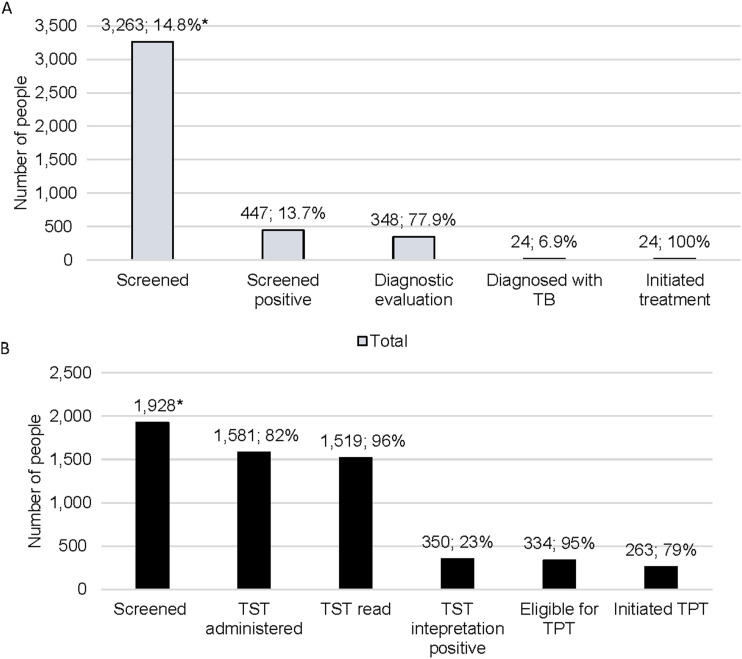

The TB case detection cascade is presented in Figure 2A. Of 3,263 participants, 13.7% (447/3,263) screened positive by symptoms and/or CAD4TB score. The majority (77.9%) underwent further evaluation for TB and provided a sputum sample for Xpert Ultra. Twenty-four TB cases were detected, 23 bacteriologically confirmed and one clinically diagnosed, representing a screening yield of 0.7% and a diagnostic yield of 5.4%. All detected cases were linked to treatment.

FIGURE 2.

SWEEP-TB Daru case detection and prevention cascades, June–November 2023. A) TB case detection cascade, June-November 2023. Screening yield: 24/3,263 (0.7%); diagnostic yield: 24/447 (5.4%). *Proportion of 22,099 people enumerated during household mapping. The denominator for each proportion is the total from the previous step of the cascade; B) TB prevention cascade, June–November 2023. *The number screened is of those aged 5–34 years and active TB ruled out. The denominator for each proportion is the total from the previous step of the cascade. TST = tuberculin skin test; TPT = tuberculosis preventive therapy.

There were 1,928 participants eligible for a TST (aged 5–34 and screened negative or screened positive but did not have TB diagnosed after further evaluation). The number of TST placements and reading increased over time, peaking in October 2023 (Figure 1). The overall proportion of TST reading was high at 96.1%, and uptake of TPT was high at 78.7% (Figure 2B).

Four PDSA cycles were completed before and during implementation (baseline, Month 1–2; Month 3–5; Month 6) (Table 2). Cycle 0 (baseline) shows the initial model review during the pre-implementation phase. The focus was on reviewing tools, standard operating procedures, training materials, and human resources. Cycle 1 reflects further changes in the revised model of care. Key challenges identified during the Cycle 1 review include a slow screening pace, diagnosis and management of asymptomatic participants with a high CAD4TB score who did not have bacteriological confirmation, and supply chain management leading to stockouts of Xpert Ultra cartridges, TPT drugs, PPD, and other consumables. Recommendations and changes led to Cycle 2 and 3 reviews with a plan for better efficiencies in the next implementation phase.

TABLE 2.

PDSA cycle in SWEEP-TB Daru implementation, May–December 2023.

| Cycle | Plan | Do | Study | Act |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0: Pre-implementation (May 2023) | Trial implementation | Pilot implementation conducted: November 2022 |

|

|

| Test tools and process in trial implementation | Version 1 of tools and SOP used in trial implementation |

|

|

|

| Team recruitment, training, and orientation | 33 new staff recruited, total SWEEP-TB staff (n = 45); SWEEP-TB staff trained and orientated | Staff assessed after training and orientation for sub-team allocation as per organogram | Allocated in sub-teams to focus on specific activities/tasks | |

| Staff screening in preparation for full implementation in the community | 57 staff screened in May 2023 | Revised process and tools with team |

|

|

| 1: Start implementation (1 June–22 August 2023) | Full implementation by ward: sequence: Ward 1 > Ward 2 > Ward 3 > Ward 4 | Ward 1:

|

|

|

| 2: Implementation (23 August–7 November 2023) | Progress implementation with recommended actions from Cycle 1 | Continued screening and TPT in Ward 1 |

|

|

| 3: Implementation (8 November–15 December 2023) | Continue and progress implementation with recommended actions from Cycle 2 | Progressed screening in Ward 1 |

|

|

PDSA = plan-do-study-act; SWEEP-TB = Systematic Island-Wide Engagement & Elimination Project for TB; DGH = Daru General Hospital SOP = standard operating procedure; EMRS = Electronic Medical Record System; HEO = Health Extension Officer; CHW = Community Health Worker; VPN = virtual private network; DEO = Data Entry Officer PPD = purified protein derivative; CAG = Community Advisory Group; UPS = uninterruptible power supply; CXR = chest X-ray; CAD4TB = computer-aided diagnostics for TB; TBDC = TB Diagnostic Centre; TPT = TB preventive therapy.

The changes in the model of care for the community-wide screening, treatment, and prevention of TB are described in Table 3. Most notable changes are 1) modified consent procedures to engage the household head and increase the age of consent from 16 to 18 years based on CAG advice, 2) the CAD4TB threshold reduced from 50 to 40 as a baseline before an assessment can be made for an ideal threshold for the project, 3) exclusion of participants from TPT eligibility who were previously treated for TB or took TPT within the last 12 months, and 4) use of a shield in pregnancy during CXR procedures and avoiding TPT in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Changes in the SWEEP-TB Daru model of care over time during a continuous quality improvement initiative.

| Category | Activity | Initial | Pre-implementation | Month 1: Implementation | Month 2: Implementation | Month 3: Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and diagnosis | Consenting (screening) |

|

|

|

No change | No change |

| Symptom screening | Symptom screening at household | No change | No change | No change | No change | |

| CXR (CAD4TB) |

|

|

|

|

Order protective shield for pregnant women | |

| Sputum collection (Xpert Ultra) |

|

|

|

|

No change | |

| Clinical evaluation |

|

|

|

No change |

|

|

| Consenting (TST/TPT) | Written consent at the screening site |

|

|

Exclusion if previous TB treatment or TPT in the past 12 months | No change | |

| TST |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Treatment | MTB/RR-TB detected | Refer to hospital for active TB treatment | Same as the initial follow-up to confirm treatment initiation | Same as pre-implementation | Same as pre-implementation | Same as pre-implementation |

| Presumptive, MTB not detected | Based on clinical evaluation | Refer to hospital for further evaluation | Same as pre-implementation | Same as pre-implementation | Same as pre-implementation | |

| Prevention | TPT | TST-positive initiated on 6HLFx (5–34 years) and 6Lfx (<5 years) |

|

Follow-up clinics at the screening site | TPT considerations for pregnant participants |

|

| BCG | 0–34 years who have never been vaccinated | No change | No change | No change | No change |

CXR = chest radiography; CAD4TB = computer-aided diagnostics for TB; SAM = severe acute malnutrition; DS-TB = drug-susceptible TB; DR-TB = drug-resistant TB; GA = gastric aspirate; FNAB = fine-needle aspirate biopsy; TST = tuberculin skin test; TPT = TB preventive therapy; MTB = Mycobacterium tuberculosis; RR-TB = rifampicin-resistant TB; 6HLfx = 6 months of isoniazid and levofloxacin; DART = Daru Accelerated Response to TB.

DISCUSSION

Early experiences from implementing SWEEP-TB Daru, a comprehensive community-wide initiative to detect, treat, and prevent TB, have demonstrated an effective model with high uptake rates. Notably, there have been reasonable rates of linkage to evaluation for active disease and TB infection among those eligible, complete linkage of diagnosed cases to active TB treatment, and high rates of TPT uptake among eligible (TST-positive) children, adolescents, and adults. The yield of active TB and TB infection among community participants screened is moderately high, supporting the continuation of the initiative. Although our study has only completed four cycles by the time of this interim analysis, findings and lessons from the CQI initiative optimised the implementation of SWEEP-TB. However, there is room for improvement. High uptake and completion across all stages of the detection and prevention cascades will be required to reduce TB incidence. We have found the PDSA cycle to be an effective framework for CQI that will be continued as part of SWEEP-TB Daru.

Community-wide, systematic household screening, treatment, and prevention of TB is novel for PNG and the region. Implementation in a population with such a high prevalence of MDR/RR-TB is also novel, with specific challenges such as overcrowding and a highly mobile population.8 As the context and scope of this community-wide project are innovative and unique and only partially implemented, it is difficult to compare to the final findings from other programmes. A community-wide intervention in a remote Pacific island with a smaller population had a similar screening yield (0.75%) and introduced TPT for household contacts with infection.17 Across the border in a district of Indonesia’s Papua province, a CQI approach was employed to successfully strengthen and decentralise TB services with increased case detection at the primary care level and the introduction of TPT, but this was also limited to eligible household contacts in a setting with a low prevalence of MDR/RR-TB.18 Similar comprehensive search, treat, and prevent initiatives19 are now being implemented in the Asia-Pacific region but not in high transmission MDR/RR-TB settings.20,21

In Daru, the pace of screening coverage needs to be accelerated further to achieve impact. This has been a major focus of the implementation team and the CQI initiative. A protracted intervention is likely to be less effective at reducing transmission and burden than a rapid one, but by how much is not known. Annual screening performed for three years in communities in southern Vietnam significantly impacted TB prevalence and transmission measured at four years after intervention compared to non-intervention communities.22 The resources required for multiple, rapid active case-finding (ACF) cycles are considerable and well beyond the usual capacity of TB programmes. The impact on TB notifications over time from this “real-world” implementation project in PNG and similar community-wide approaches20,21 in the region will be informative.

A model of care was developed for SWEEP-TB with CAG and broad stakeholder input before implementation, and adjustments were made during implementation. We found that most changes to the model of care were required for the screening component during the four phases of revision. This may be because a greater proportion of issues were identified in activities relating to screening compared to treatment and prevention. In addition, this analysis reports the initial phase of implementation with fewer issues identified for treatment and prevention activities.

We found that around 20% of participants were lost to care in the case detection (from screen positive to diagnostic evaluation) and prevention (TPT eligible to initiated) cascades. In our setting, “structural barriers” such as social and financial issues and population mobility have been identified as barriers to accessing TB services rather than inadequate knowledge or health-seeking behaviours.23 All people diagnosed with TB were linked to the routine TB program for treatment registration and continuation of care, and those receiving TPT are being routinely and regularly followed to completion. However, this interim analysis is too early to report on treatment outcomes, including infection with TPT.

We identified high BCG coverage for the population screened thus far. Infant BCG immunisation has been recommended in PNG for decades but with low uptake in the past few years.24 In our study, evidence of BCG coverage included examination for a typical scar rather than relying only on recall. Most participants in SWEEP-TB are adolescents and adults, so our findings reflect mainly past rather than recent immunisation coverage or uptake. Nonetheless, the high coverage is an encouraging finding given that low childhood immunisation coverage in PNG and Western Province is a major public health concern.24

A strength of this study is the use of systematically recorded data for real-time evaluation, monitoring, and evaluation. Data-informed change was used to monitor the impact of the change. The high yield from case detection and prompt initiation of treatment indicates the quality of care provided. The willingness of individuals to participate and overall acceptance of SWEEP-TB by the community may reflect the sustained and recent efforts to engage and educate the community over many years, including input from the CAG and involvement of community leaders, likely leading to a sense of community “ownership” and less TB-related stigma.2,3,8 One limitation is a potential bias in our reporting, as the primary focus of the CQI approach was towards improving outcomes with positive results. However, identified challenges and negative outcomes or data did inform the process as barriers to overcome. Early analysis of implementation data may not be representative of the final analysis. However, for the CQI framework, continuous monitoring of cascade data is necessary and important to guide implementation. There are no data yet for the outcomes of TB treatment or TPT. These key programmatic indicators will be analysed to report full cascades of care. In conclusion, implementing the CQI initiative using a PDSA framework improved project implementation. Detection of TB disease and infection in island residents increased, and the pace of screening was needed to achieve timely community-wide coverage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was part of the Operational Research Course for TB in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 2022–2023. The specific training programme that resulted in this publication was developed and implemented by the Burnet Institute (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) in collaboration with the PNG Institute of Medical Research (Goroka) and University of PNG (Port Moresby, PNG) and supported by the PNG National TB Programme.

The model is based on the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the WHO/TDR.

The investigators acknowledge and thank the following people who contributed to the protocol development, planned data collection, or analysis from which the operational research topic was developed: S Vaccher, D Lin, T Kelebi, C Manorh, T Dalmong, M Namaibai, J Sawi, A Koivaku, and the SWEEP-TB Team.

The training programme was delivered as part of the SWEEP-TB Daru and PRIME-TB projects, supported by the Australian Government and implemented by the Burnet Institute. The Reducing the Impact of Drug-Resistant TB (RID-TB) Western Province programme is supported by the Australian Government and implemented by the Burnet Institute as part of the Western Province TB Programme in partnership with the Western Provincial Health Authority, PNG Australia Transition to Health (PATH) and World Vision International. The SWEEP-TB Daru project is supported by a Medical Research Future Fund grant (MRF 121008) from the Australian government. The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and are not necessarily those of the Australian or PNG Governments. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Footnotes

SSM and TM contributed equally.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis report, 2023. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kase P, Dakulala P, Bieb S. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis on Daru Island: an update. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(8):e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris L, et al. The emergency response to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Western Province, Papua New Guinea, 2014–2017. Public Health Action. 2019;9(Suppl 1):S4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aia P, et al. The burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Papua New Guinea: results of a large population-based survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavu E, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis diagnosis since Xpert MTB/RIF introduction in Papua New Guinea (2012-2017). Public Health Action. 2019;9(Suppl 1):S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honjepari A, et al. Implementation of screening and management of household contacts of tuberculosis cases in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action. 2019;9(Suppl 1):S31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainomugisa A, et al. Multi-clonal evolution of multi-drug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a high-prevalence setting of Papua New Guinea for over three decades. Microb Genom. 2018;4(2)e000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majumdar SS, et al. Contact screening and management in a high-transmission MDR-TB setting in Papua New Guinea: progress, challenges and future directions. Front Trop Dis. 2023;3:1085401. [Google Scholar]

- 9.King’s Improvement Science . Step 1: KIS introduction to quality improvement. London, UK: KIS, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leis JA, Shojania KG. A primer on PDSA: executing plan-do-study-act cycles in practice, not just in name. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(7):572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memiah P, et al. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) institutionalization to reach 95:95:95 HIV targets: a multicountry experience from the Global South. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiferaw MB, Sisay Misganaw A. Evaluation of continuous quality improvement of tuberculosis and HIV diagnostic services in Amhara Public Health Institute, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaga S, et al. Continuous quality improvement in HIV and TB services at selected healthcare facilities in South Africa. S Afr J HIV Med. 2021;22(1):a1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pai M, Temesgen Z. Quality: the missing ingredient in TB care and control. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;14:12–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Statistical Office . Population estimates, 2021. Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea: National Statistical Office, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adepoyibi T, et al. A pilot model of patient education and counselling for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action. 2019;9:S82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brostrom RJ, et al. TB-free Ebeye: results from integrated TB and noncommunicable disease case finding in Ebeye, Marshall Islands. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2024;35:100418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lestari T, et al. Impacts of tuberculosis services strengthening and the COVID-19 pandemic on case detection and treatment outcomes in Mimika District, Papua, Indonesia: 2014–2021. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(9):e0001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangaka MX, et al. Controlling the seedbeds of tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis infection. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2344–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman M, et al. Population-wide active case finding and prevention for tuberculosis and leprosy elimination in Kiribati: the PEARL study protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e055295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks GB, et al. Epidemiological approach to ending tuberculosis in high-burden countries. Lancet. 2022;400:1750–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks GB, et al. Community-wide screening for tuberculosis in a high-prevalence setting. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1347–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jops P, et al. Beyond patient delay: navigating structural health system barriers to timely care and treatment in a high burden TB setting in Papua New Guinea. Glob Public Health. 2023;18:2184482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mekonnen DA, et al. Use of a catch-up programme to improve routine immunization in 13 provinces of Papua New Guinea, 2020–2022. West Pac Surveill Response J. 2023;14(4):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]