Abstract

Practical relevance:

Aggression towards owners is a common behavioural problem in cats, particularly in cats that have been obtained from pet shops or other sources where there has been inadequate socialisation with people, and in those kept only indoors. Very often aggression is associated with a stress response and it may potentially lead to relinquishment and euthanasia of the cat. Therefore, preventing and treating owner-directed aggression has significant benefits for the welfare of the cat and the quality of the cat–owner bond.

Aim:

The objectives of this article are to highlight the characteristics of the most common types of feline aggression towards human family members and to describe, in a very practical way, the main treatment strategies. The article is aimed at general practitioners; for severe cases of aggression and/or cases involving feral cats, referral to a specialist behaviourist is recommended.

Clinical challenges:

Veterinarians and behaviourists are not always able to witness the aggressive behaviour of the cat and therefore a detailed and accurate interview, as well as the use of complementary tools such as video recording, is essential to reach a diagnosis.

Evidence base:

This review draws on evidence from an extensive body of published literature as well as the authors’ clinical experience and own research.

Keywords: Aggression, behaviour, owner-directed aggression, cat–owner bond

Introduction

Aggressive behaviour towards owners and family members is very common in cats,1-5 especially in single-cat households. 6 Cats that have been obtained from pet shops and/or not properly socialised with people, those that are early weaned and indoor-only cats appear to be more likely to show aggression problems.7-10

Aggression towards human family members has a strong negative impact on the welfare of cats. Not only are most cases of aggressive behaviour a response to underlying stress, 11 but this form of aggression reduces the quality of the cat–owner bond,12,13 and may lead to relinquishment and euthanasia.14,15

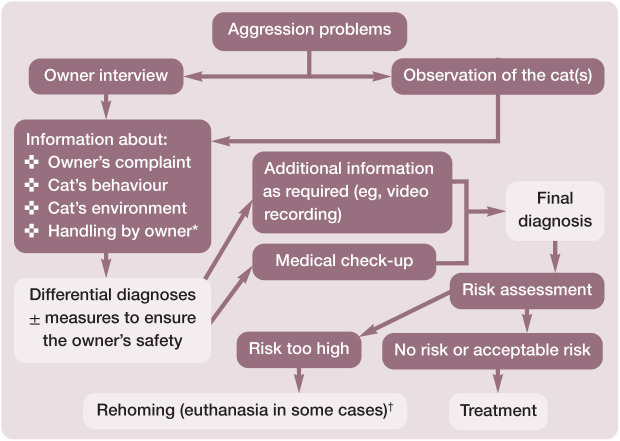

The first step of the diagnostic protocol is to characterise the type of aggression (see Figure 1). This can be achieved through a description of the cat’s behaviour obtained from a detailed owner interview and from observation of the cat in its home environment. 5

Figure 1.

Diagnostic protocol for feline aggression problems. *Includes aspects such as how the owner plays and interacts with their cat, the use of punishment and reinforcers, and consistency of handling. † Assess on a case-by-case basis; the welfare of the cat and safety of any future owners are the main concerns

Many specialists base the terminology used to classify aggression in cats on a system proposed around 50 years ago by Moyer. 16 The classification used in this review, as well as a qualitative estimate of the frequency of each type of aggressive behaviour, appears in Table 1. Recently, a classification system based on emotional motivations for aggression has also been used. 17 Several aspects of the treatment protocol are relevant across different types of aggressive behaviour, and are discussed in a section on general treatment strategies. Other aspects are specific to particular types of aggression, and are covered separately.

Table 1.

Types of aggressive behavior In cats and their estimated frequency

| Aggressive behaviour | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Misdirected predatory behaviour | Very common |

| Petting-related aggression | Very common |

| Fear-related aggression | Common |

| Redirected aggression | Common |

| Maternal aggression | Less common |

Adapted from Moyer. 16 Aggression may also be due to an underlying disease or medical condition, although this is less common

Two important aspects should be considered before treating aggressive behaviour in cats. First, a risk assessment should be performed,18,19 based on both the cat’s behaviour and its social environment (Table 2). When the risk of further aggression is high, it may be appropriate to rehome the cat to a more suitable environment that, for example, provides more space for the cat or reduces the need for frequent interactions with humans. This, however, needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and the welfare of the cat, as well as the safety of the future owners, must be the main concerns. In some cases, euthanasia of the cat is the only option.19-21

Table 2.

Risk assessment

| Risks related to the aggression problem itself | Offensive aggression (seen in maternal aggression and some cases of redirected aggression) |

| Impulsive attacks (seen in redirected aggression and in some cases of fear-related aggression, maternal aggression and aggression due to an underlying disease or medical condition) | |

| Risks related to the cat’s social environment | Children or elderly people in the house |

| Family members with physical and/or mental health problems | |

| Owners who are afraid of the cat |

Adapted from Moyer. 16 Aggression may also be due to an underlying disease or medical condition, although this is less common

Secondly, a medical check-up must be performed to rule out physical health conditions that could either cause the aggressive behaviour or prevent the administration of psychoactive medications.14,17,19 This second step can sometimes be postponed if manipulation of the cat increases the risk of aggression (ie, in cases of redirected aggression – see later). The most common physical health problems associated with aggression in cats are summarised in the box above.

Types of aggressive behaviours

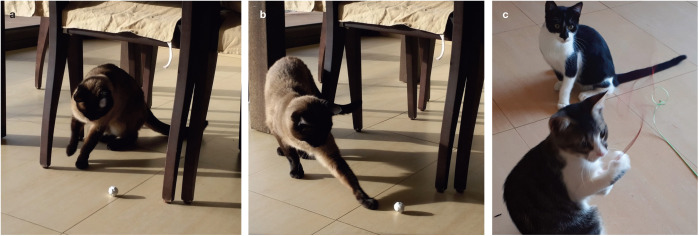

Misdirected predatory behaviour

Misdirected predatory behaviour is very common in cats, and one of the most frequent aggression problems affecting human family members.10,26,27 It is a normal feline behaviour but sometimes can result in severe injuries to people or other animals.19,20 The attack, usually silent, is triggered by movement (eg, moving the legs under the bed sheet, climbing the stairs, etc) and it involves stalking (Figure 2), chasing, catching and biting. In the literature, most authors refer to this problem as play-related aggression or inappropriate play.

Figure 2.

A predatory sequence involves stalking (pictured), chasing, catching and biting. Image ©iStock/cynoclub

This behaviour is more common in:

Petting-related aggression

Not all cats are equally tolerant of being stroked. Petting-related aggression can be very disconcerting for owners. While some cats refuse to be petted right from the start of the interaction, others demand attention and then bite and run away after a certain amount of physical contact (Figure 3).18,27 Petting-related aggression is very common and accounts for up to 40% of cases of aggressive behaviour seen by referral services.10,35,36

Figure 3.

Petting-related aggression is very common in cats and particularly disconcerting for owners.

Image ©iStock/Anastasia Lukinyh

Although the attacks are usually described by owners as being unpredictable, cats may show subtle changes in their body language before the aggressive reaction.14,20 For instance, cats may become tense, rotate and flatten their ears, and/or whip their tail.20,30 Although the precise mechanism underlying this behaviour is not properly understood, some authors suggest that it could result from a motivational conflict in the cat or a very low contact tolerance threshold.14,30

Fear-related aggression

Fear-related aggression is also a common feline behaviour problem. Although aggression is most often directed towards unfamiliar people, it can be directed towards the cat’s owners. 10 The first reaction of a cat when it feels threatened is to escape and hide; if this is not possible, it may resort to aggression as a defensive response.20,30,34

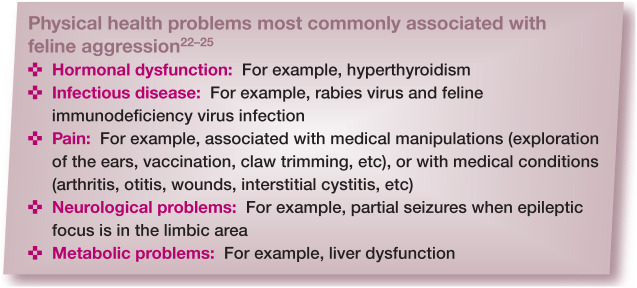

Cats’ defensive body postures and behaviours include crouching, an arched back, ears flattened, tail tucked under, piloerection, dilated pupils, snorting, grunting and sometimes screaming21,37 (Figure 4). In some cases, mainly due to chronicity of the problem, the approach of, or even simply visual contact with, the owner may cause the defensive reaction.14,18

Figure 4.

Defensive body postures in cats include (a) crouching, with ears flattened, and (b) arched back, piloerection and dilated pupils. Image (a) ©iStock/cynoclub and (b) ©iStock/GlobalP

A study conducted by Wilhelmy et al in 2016 described a higher risk of fear-related aggression towards familiar people in the Birman. 7 Although the genetic make-up of the animal is very important in fear-related problems, 38 inadequate socialisation or a previous traumatic experience with people are the main causes of fear-related aggression. 34 Cats without enough contact with people during the socialisation period (which starts at 2 weeks of age and ends at around 9 weeks) are more likely to develop fear towards people.39-42 In addition, negative experiences such as physical punishment or an unpleasant manipulation could cause fear-related problems.14,21

Redirected aggression

This category of aggression occurs when the aversive stimulus is not accessible and hence the cat attacks an alternative stimulus.33,43 This type of aggression is relatively frequent, as well as potentially being very violent and dangerous to people (Figure 5).19,33,43 Indeed, according to some authors it may account for up to 50% of all cases of aggressive behaviour towards people seen in referral practices. 44 Redirected attacks can be very unpredictable, although in many cases the owners describe a ‘weird’ behaviour before the attack. The cat’s arousal can last for a long time even after the triggering stimulus has been removed. 33 In fact, while some cats remain aroused for only 30 mins or so, others can be aroused for days.30,43,44

Figure 5.

Wounds in an owner caused by his cat exhibiting redirected aggression. In this case, the triggering stimulus was a loud noise and the alternative target was the owner himself. It is important that owners are advised to seek medical attention when necessary

The most common triggers for redirected aggression are:43,44

Loud noises

Presence of other cats

Presence of unknown people

Redirected aggression can potentially be mistaken for aggression associated with physical health problems (see earlier) and a medical check-up is therefore essential. However, in most cases this assessment should be postponed until the behaviour of the cat is back to normal (ie, its arousal level is diminished), so that the risk of another attack is reduced. Meanwhile, the safety of the owners and the welfare of the cat should always be prioritised in any advice given by the practitioner or behaviourist.

Maternal aggression

Aggressive behaviour towards owners can be shown by pregnant queens at the end of gestation, as well as by cats exhibiting pseudo-gestation.34,45 Queens that have kittened may react aggressively when the owner approaches the litter or nest. This aggressive behaviour can be maintained throughout lactation and whenever the kittens are present.

In comparison with dogs, cats very rarely show pseudopregnancy. This is because, among other reasons, cats are induced ovulators and therefore pseudogestation only occurs in the event of an unfertile mating or when ovu-lation has been triggered by a tactile stimulus other than mating; for instance, stroking the cat. Pseudopregnant bitches may show a variety of clinical signs and behavioural changes, whereas the only sign that can be observed in pseudo-pregnant queens is maternal aggression.

Cats displaying maternal aggression may vocalise with long meows and growls and adopt an offensive body posture (ie, stiffened legs, hackles raised, staring and moving towards the target, stiff tail); typically the intensity of the aggression increases as the person approaches. Poor socialisation with people can aggravate this problem. 19 Maternal aggression disappears as the mother–offspring bond wanes or the plasma concentration of prolactin (in cases of pseudogestation) decreases. 46

Treatment strategies

There are aspects of the treatment protocol that are common across different types of aggressive behaviour (see box of general treatment recommendations below). Others are specific to particular types of aggression, as described in the following sections.

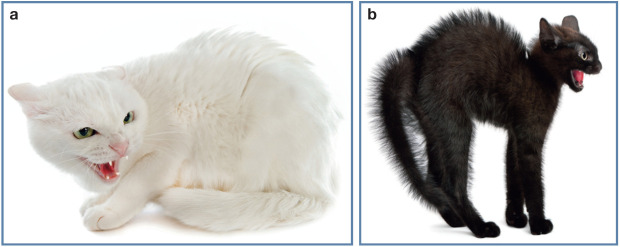

Figure 7.

Food concealed in various locations or provided using dispenser food toys will encourage exploratory behaviour and play. 47 This strategy is very useful for cats showing misdirected predatory behaviour

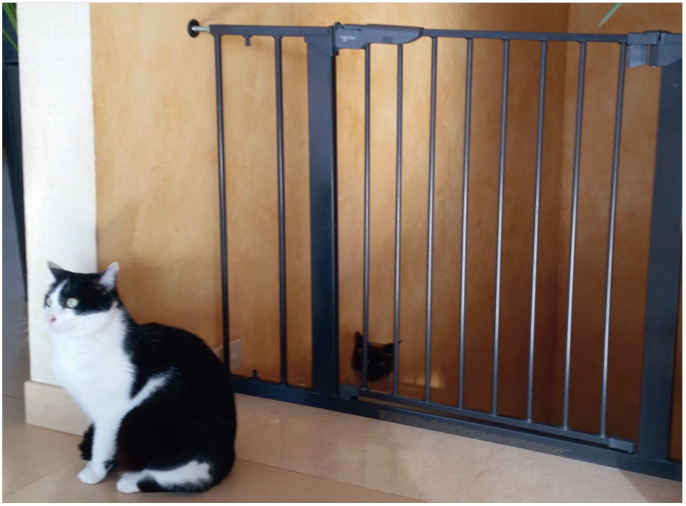

Figure 8.

A safe zone, where the cat is protected from aversive stimuli, is extremely useful for fearful animals. 34 In this case, the barrier prevented small children (which were the aversive stimuli) from accessing the cats’ area

Figure 9.

(a,b) Hiding places are crucial for cats,47,48 in particular those with fear-related problems

Specific treatment strategies for misdirected predatory behaviour

A summary of the strategies that can be used to treat misdirected predatory behaviour is shown in the box below. The main aim is to modify the target of the cat’s play so that play is directed towards toys instead of the owner’s body.

Avoid reinforcing the problem behaviour

The cat’s problem behaviour can be exacerbated due to unintentional reinforcement by the owner; for example, trying to redirect the attack by throwing a ball once the cat has already started the sequence may be a poor strategy because the cat could perceive that the owner is playing with it, hence rewarding this behaviour. 17 Another mistake is to move during the attack, as it is the movement of the owner’s body that triggers the cat’s behaviour. 17 Therefore, staying still may help to stop the attack or, at least, reduce the intensity of the aggression.17,18 This is not always easy, and ensuring that owners protect themselves with suitable clothing may be advisable.

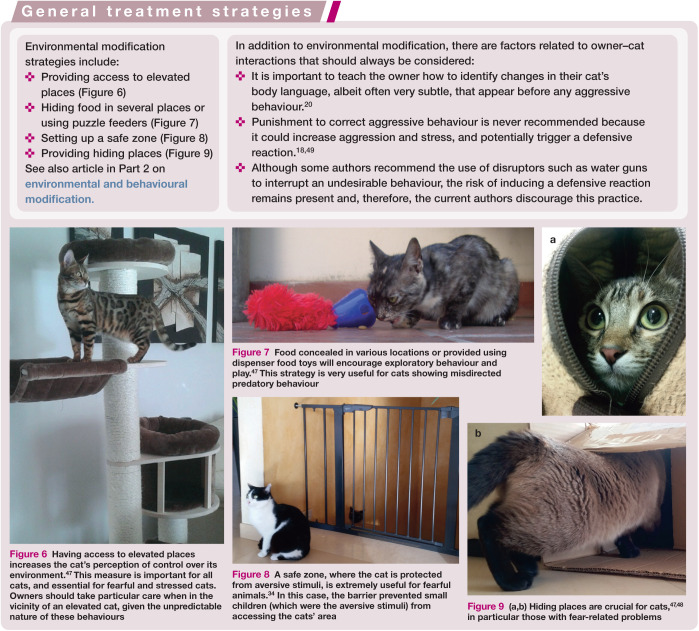

Encourage appropriate play

Play behaviour is very important for cats, especially those that do not have access to the outside. 18 Therefore, it is an activity that should be part of the daily routine. Owners should avoid playing with the cat using their hands and/or feet (Figure 10). The ideal play for cats is summarised in Table 3.

Figure 10.

(a,b) A ball of aluminium foil or (c) a length of ribbon are simple but effective play items for cats. Play should always be supervised and owners’ hands kept safely out of harm’s way (eg, the ribbon could be dangled from a chair)

Table 3.

| Main toy characteristics | Small |

| Mobile; easy to manipulate and chase | |

| Easy to grasp with the mouth | |

| Most appropriate time for playing | Immediately after the owner returns |

| home | |

| After a rest period | |

| Early evening | |

| Owner behaviours to avoid during play | Punishing the cat |

| Playing with their hands or feet, or using rod toys that have short rods |

As cats are crepuscular animals, there is a higher probability that they want to play in the evening. 18 Anticipating when and where inappropriate play is more likely to occur, so the owners can encourage appropriate play at these times, may reduce the likelihood of new attacks.

Specific treatment strategies for petting-related aggression

A summary of the strategies that can be used for cats that display petting-related aggression is given in the box below. A key aim is to make petting a positive experience for the cat.

Decrease contact with the cat

As this type of aggression occurs during handling, the number and duration of owner-cat interactions should be minimised. The owner should wait until the cat asks for attention and avoid handling in any other circumstances.18,20 If the cat seeks attention, the owner should give it a single stroke and initially avoid areas of the body such as the belly and the legs. Progressively, the owner can touch different body areas and pet the cat for a longer time.

Learn to interpret the body language

It is advisable to teach the owner how to identify signs that precede an aggressive reaction (eg, flicking of the tip of the tail). However, this can be difficult as some of these signs are very subtle indeed.

Make petting a positive experience for the cat

Pairing a very palatable food with petting could help to make owner contact a more positive experience (Figure 11). Areas of the body that cats generally dislike being petted (see above) should be avoided. 20 Petting should start once the cat is eating and finish before the cat stops eating. The duration of the petting sessions should be increased in a very gradual manner.

Figure 11.

A preferred food can be used as a reward while habituating the cat to being petted

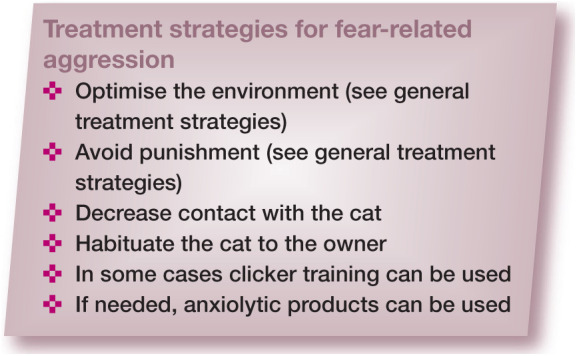

Specific treatment strategies for fear-related aggression

A summary of the strategies that can be used in fear-related aggression is given in the box below. The main aim is to reduce the cat’s tearfulness of its owners.

Decrease contact with the cat

Cats with fear-related aggression react aggressively when they feel threatened and have no opportunity to escape. Therefore, it is very important that the cat is not forced to interact with people.31,34

Increase the predictability of the environment

One of the factors that has a major influence on an animal’s stress response is its capacity to control and predict the occurrence of aversive events.54-56 When a negative stimulus (ie, one that elicits fear) is predictable for the animal, the stress response is less pronounced.34,49,57

A cat’s sense of control can be increased by:

Providing elevated areas (eg, shelves or cat trees) (Figure 6);

Establishing consistent daily routines;

Attaching a bell to the clothing of any young children that are a stressful stimulus, to help the cat to gauge the child’s proximity.

Figure 6.

Having access to elevated places increases the cat’s perception of control over its environment. 47 This measure is important for all cats, and essential for fearful and stressed cats. Owners should take particular care when in the vicinity of an elevated cat, given the unpredictable nature of these behaviours

Habituate the cat to the owner

The behaviour modification protocol should be tailored to each particular situation as, for example, some cats may react defensively to the mere presence of a person, whereas others will only react negatively if there is physical contact.

The first goal is to change the perception of the cat, pairing the presence of the owner with a reward.18,27,58,59 For instance, owners can place bits of food within the cat’s reach and walk away, allowing the cat to come to eat as it chooses. After some time, the cat stops seeing the person as a potential threat and, instead, begins to associate them with a positive stimulus (food or treat).

Once the cat has become habituated to the presence of the owner, the cat should be rewarded by the owner when it comes closer. For example, the owner can sit on the floor (to appear less threatening) and throw a treat some distance away from themselves, then a second one closer and so on. The last reward should always be thrown some distance away again so the cat returns to its comfort zone, away from the threatening stimulus (ie, the owner). 59 This exercise should be repeated for several days until the cat approaches the owner with confidence. The next step is to train the cat to tolerate direct contact.

These exercises can be carried out using a clicker as a secondary reinforcer. 27 If the fear response is severe, it may be necessary to use an anxiolytic product. It is important to remember that although the temperament of the cat cannot be changed, its perceptions can be shaped.

* Clicker training The clicker allows a behaviour to be rewarded at the precise moment it is performed and from a distance (Figure 12). Therefore, if the cat approaches the owner in a relaxed manner, the owner can reward it with the clicker and then give a food reward. 34 Before doing this, the clicker has to be ‘loaded’ or conditioned; that is, the sound of the clicker is paired with a reward several times until the cat associates the sound with a positive stimulus. 18 If the cat is very fearful, a loud clicker should be avoided. One option is to use the clicker while inside a pocket or wrapped in a piece of material to attenuate its sound.

* Use of anxiolytic products An anxiolytic product can improve the welfare of cats with severe fear and facilitate the implementation of the behavioural modification program. 18 (For further discussion, see the article in Part 2 on psychoactive medications.) Some anxiolytics can be mixed with food or with other substances (eg, malt extract) to avoid the stress of forced oral administration (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

In fearful cats, the clicker allows a desirable behaviour to be rewarded without direct owner-cat contact

Figure 13.

If a cat rejects the food that contains the medication, one option is to mix the drug with malt extract and place it on the cat’s paw

There are two fundamental considerations when administering any anxiolytic drug:

A check-up is a prerequisite, as an underlying disease or medical condition could be involved;

Handling should be minimised as it may increase the risk of aggression. 48

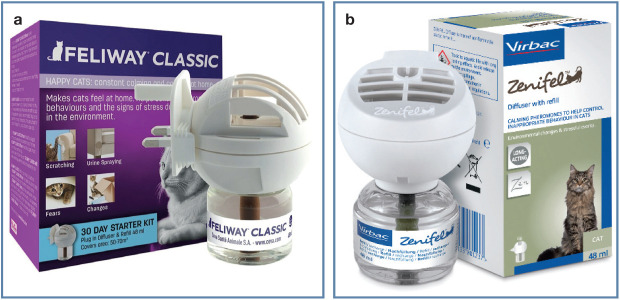

Other anxiolytic products, such as nutraceuti-cals and pheromones (Figure 14), can potentially be useful in these cases (see article in Part 2 on pheromone therapy). However, there are currently no peer-reviewed studies on their use to treat human-directed aggression in cats.

Figure 14.

Fraction 3 of the feline facial pheromone appears to have anxiolytic properties. 65 If fear or stress responses are involved, a diffuser (a,b) releasing this pheromone could be placed where the cat spends most of its time (eg, safe area)

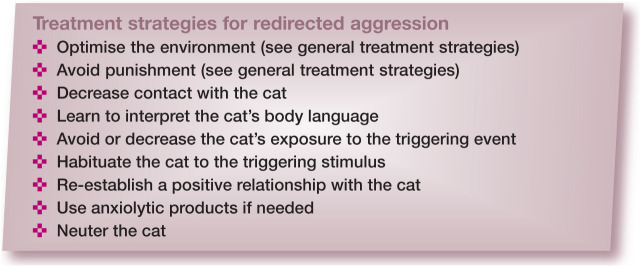

Specific treatment strategies for redirected aggression

A summary of the strategies that can be used to treat redirected aggression is given in the box below. The main aim is to avoid further attacks and increase the tolerance of the cat to the triggering event.

Decrease contact with the cat

Cats displaying redirected aggression could maintain a state of arousal for hours and even days. During this period, the risk of new attacks is very high. Therefore, the owners should avoid interacting with the cat. 44

Learn to interpret the cat’s body language

It is useful to teach owners how to identify the signals that precede an attack, although, as already noted, this may be difficult as such signals can be very subtle. 19 A change in the cat’s facial expression, as well as ‘weird’ behaviour, are often described preceding redirected attacks.

Avoid or decrease the cat’s exposure to the triggering event

If the triggering stimulus has been identified, it should be removed whenever possible. 19 Sometimes this can be done relatively easily; for example, by avoiding loud noises or exposing the cat to the smell of other cats.

Habituate the cat to the triggering stimulus

Whenever the cause of a redirected attack has been identified, a desensitisation protocol should be applied, though only when the cat is not aroused. This involves presenting the triggering stimulus gradually, either by slowly increasing its intensity (eg, when the triggering stimulus is a sound) or by reducing its proximity to the cat. See the article in Part 2 on environmental and behavioural modification for further information.

Re-establish the relationship with the cat

After a redirected attack, the aggressor cat may develop a bad relationship with the alternative target. If the alternative target of the attacks is the owner, the measures described in the discussion on fear-related aggression (see page 250) may be useful. If the alternative target is another cat in the same household, a reintroduction protocol should be implemented (see the accompanying article in this issue on aggression in multi-cat households).

Use of an anxiolytic

There are few studies on redirected aggression in cats. According to one of them, the owners described a defensive posture in 80% of cases, suggesting that fear, as well as frustration, can be an underlying motivation 43 Studies performed in other species showed that individuals that redirect their aggression had lower levels of glucocorticoids compared with those that do not. 67 This suggests that redirected aggression may be a coping mechanism in stressful situations and hence the administration of an anxiolytic product could be beneficial. As discussed earlier, if an anxiolytic drug is administered, a medical check-up is required and handling should be minimised 44

Neutering

A correlation between high circulating sex hormone levels and an increased risk of aggressive interactions between cats has been shown 33 Based on this, and considering that stimuli from other cats are one of the most common triggers for redirected aggression, neutering can be useful.

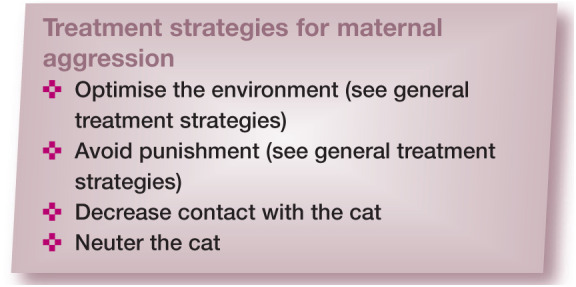

Specific treatment strategies for maternal aggression

A summary of the strategies that can be used to treat maternal aggression is given in the box below. The main aim is to avoid further attacks and rejection of the kittens.

Decrease contact with the cat

It is recommended that handling of the kittens is minimised during the first few days, when the mother is more protective. If the queen tolerates the proximity of the owner to the kittens but reacts aggressively when the owner tries to touch them, the owner could sit close to the female and offer food or treats so that the queen learns that the presence of the owner is not dangerous for the kittens. 20

If it is essential to check the offspring, the queen can be distracted away using food. Otherwise, the kittens can be supervised and the nest cleaned when the queen is away from it. It is important not to use heavily scented or potentially harmful products to clean the nest.

Neutering

Neutering the female will prevent the occurrence of maternal aggression. 34

Key Points

Whenever a cat shows aggression towards the owner, it is essential to carry out a risk assessment and ensure the owner’s safety throughout the process.

In severe cases and/or cases involving feral cats, referral to a specialist behaviourist is recommended.

Physical health problems may directly or indirectly influence the cat’s behaviour.

Misdirected predatory behaviour and petting-related aggression are very common. An understanding of feline behaviour and underlying motivations will help to decrease the risk of these problem behaviours.

Appropriate socialisation with people and good habituation to negative stimuli, such as noises, may reduce the risk of fear-related aggression, maternal aggression and redirected aggression.

Treatment strategies should include safety measures for owners, environmental and behavioural modification, and changes in owner-cat interactions.

Supplemental Material

Special issues on feline behaviour and problem behaviours

Acknowledgments

We thank Susana Le Brech, Camino Garcia-Morato and Tomas Camps for their help.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and /or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Wright JC, Amoss RT. Prevalence of house soiling and aggression in kittens during the first year after adoption from a humane society. Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224: 1790-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bamberger M, Houpt KA. Signalment factors, comorbidity, and trends in behavior diagnoses in cats: 736 cases (1991–2001). / Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 229: 1602-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bradshaw JWS, Casey RA, Brown SL. Undesirable behaviour of the domestic cat. In: Bradshaw JWS, Casey RA, Brown SL. (eds). The behaviour of the domestic cat. 2nd ed. Wallingford: CABI, 2012, pp 190-205. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wassink-van der Schot AA, Day C, Morton JM, et al. Risk factors for behavior problems in cats presented to an Australian companion animal behavior clinic. / Vet Behav 2016; 14: 34-10. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stelow E. Diagnosing behavior problems: a guide for practitioners. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018; 48: 339-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Association of Pet Behaviour Counsellors. Annual review of cases 2005. www.apbc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/review_2005.pdf (2005, accessed December 11, 2018).

- 7. Wilhelmy J, Serpell J, Brown D, et al. Behavioral associations with breed, coat type, and eye color in single-breed cats. / Vet Behav 2016; 13: 80-87. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahola MK, Vapalahti K, Lohi H. Early weaning increases aggression and stereotypic behaviour in cats. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heidenberger E. Housing conditions and behavioural problems of indoor cats as assessed by their owners. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1997; 52: 345-364. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amat M, Ruiz de la Torre JL, Fatjo J, et al. Potential risk factors associated with feline behaviour problems. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2009; 121: 134-139. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kruk MR, Halasz J, Meelis W, et al. Fast positive feedback between the adrenocortical stress response and a brain mechanism involved in aggressive behavior. Behav Neurosci 2004; 118: 1062-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Houpt KA, Honig SU, Reisner IR. Breaking the human-companion animal bond. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 208: 1653-1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Serpell JA. Evidence for an association between pet behavior and owner attachment levels. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1996; 47: 49-60. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bain M, Stelow E. Feline aggression toward family members: a guide for practitioners. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2014; 44: 581-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salman MD, Hutchison J, Ruch-Gallie R, et al. Behavioral reasons for relinquishment of dogs and cats to 12 shelters. J Appl Anim Welf Sci 2000; 3: 93-106. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moyer KE. Kinds of aggression and their physiological basis. Commun Behav Biol 1968; 2: 65-87. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casey R. Human-directed aggression in cats. In: Rodan I, Heath S. (eds). Feline behavioral health and welfare. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016, pp 374-380. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowen J, Heath S. Feline aggression problems. In: Bowen J, Heath S. (eds). Behaviour problems in small animals: practical advice for the veterinary team. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp 205-227. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hunthausen WL. Helping owners handle aggressive cats. Vet Med 2006; 101: 719-727. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Curtis TM. Human-directed aggression in the cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2008; 38: 1131-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berger J. Feline aggression toward people. In: Little S. (ed). August’s consultations in feline internal medicine. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016, pp 911-918. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reisner I. The pathophysiologic basis of behavior problems. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1991; 21: 207-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horwitz DF, Neilson JC. Aggression: medical differentials. In: Horwitz DF, Neilson JC. (eds). Blackwell’s five-minute veterinary consult clinical companion: canine and feline behavior. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp 179-185. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. Approach to diagnosis [in Spanish]. In: Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. (eds). Practical manual of clinical ethology of the cat. Sant Cugat: Multimedica Ediciones Veterinarias, 2017, pp 3-25. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martell-Moran NK Solano M Townsend HGG . Pain and adverse behaviour in declawed cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 280-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Borchelt PL, Voith VL. Aggressive behavior in cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1987; 9: 49-56. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Landsberg G, Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Feline aggression. In: Landsberg G, Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. (eds). Handbook of behavior problems of the dog and cat. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2003, pp 205-227. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Overall K. Management related problems in feline behavior. Feline Pract 1994; 22: 13-15. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Overall K. Feline aggression, part 1. Feline Pract 1994; 22: 25-26. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beaver BV. Feline social behavior. In: Beaver BV. (ed). Feline behavior. A guide for veterinarians. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2003, pp 127-163. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horwitz DF, Neilson JC. Aggression/feline: play related. In: Horwitz DF, Neilson JC. (eds). Blackwell’s five-minute veterinary consult clinical companion: canine and feline behavior. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp 141-147. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hart BL, Hart LA. Feline behavioural problems and solutions. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat. The biology of its behaviors. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp 201-212. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beaver BV. Fractious cat and feline aggression. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Overall K. Undesirable, problematic, and abnormal feline behavior and behavioural pathologies. In: Overall K. (ed). Manual of clinical behavioral medicine for dogs and cats. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 2013, pp 360-456. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chapman BL. Feline aggression. Classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1991; 21: 315-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramos D, Mills DS. Human directed aggression in Brazilian domestic cats: owner reported prevalence, contexts and risk factors. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 835-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bradshaw J, Cameron-Beaumont C. The signalling repertoire of the domestic cat and its undomesticated relatives. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behavior. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp 68-93. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turner DC, Feaver J, Mendl M, et al. Variation in domestic cat behaviour towards humans: a paternal effect. Anim Behav 1986; 34: 1890-1892. [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCune S. The impact of paternity and early socialization on the development of cat’s behaviour to people and novel objects. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1995; 45: 109-124. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Karsh EB, Turner DC. The human-cat relationship. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp 159-178. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Casey RA, Bradshaw JWS. The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behavior and suitability as a pet. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2008; 114: 196-205. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Turner DC. The human-cat relationship. In: Turner D, Batson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp 193-206. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amat M, Manteca X, Ruiz de la Torre JL, et al. Evaluation of inciting causes, alternative targets, and risk factors associated with redirected aggression in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2008; 233: 586-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chapman BL, Voith VL. Cat aggression redirected to people: 14 cases (1981–1987). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990; 196: 947-950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Inselman-Temkin BR, Flynn JP. Sex-dependent effects of gonadal and gonadotrop-ic hormones on centrally elicited attack in cats. Brain Res 1973; 60: 393-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hart BL. The behavior of domestic animals. New York: WH Freeman & Co, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ellis S, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Amat M, Camps T, Manteca X. Stress in owned cats: behavioural changes and welfare implications. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 18: 577-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pachel C. Intercat aggression: restoring harmony in the home: a guide for practitioners. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2014; 44: 565-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hall SL, Bradshaw JWS, Robinson IH. Object play in adult domestic cats: the roles of habituation and disinhibition. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2002; 79: 263-271. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. Treatment of inappropriate play [in Spanish]. In: Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. (eds). Practical manual of clinical ethology of the cat. Sant Cugat: Multimedica Ediciones Veterinarias, 2017, pp 179-182. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Levine E, Perry P, Scarlett J, et al. Intercat aggression in households following the introduction of a new cat. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2005; 90: 325-336. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crowell-Davis SL. Intercat aggression. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2007; 29: 541-546. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weinberg J, Levine S. Psychobiology of coping in animals: the effects of predictability. In: Levine S, Ursin H. (eds). Coping and health. New York: Plenum Press, 1980, pp 39-59. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Carlstead K, Brown JL, Strawn W. Behavioural and physiological correlates of stress in laboratory cats. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1993; 38: 143-158. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011; 35: 1291-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Demontigny-Bedard I, Frank D. Developing a plan to treat behavior disorders. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018; 48: 351-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schwartz B, Wasserman EA, Robbins SJ. Pavlovian conditioning: basic phenomena. In: Schwartz B, Wasserman EA, Robbins SJ. (eds). Psychology of learning and behavior. 5th ed. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2002, pp 41-69. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tejedor S, Amat M, Camps T, et al. A new approach to treat fear-related problems towards unfamiliar people in dogs. Proceedings of the ECAWBM-AWSELVA-ESVCE Congress, 2015, September 30 to October 3, Bristol (UK), p 63. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Landsberg G, Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Pharmacological intervention in behavioral therapy. In: Landsberg G, Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. (eds). Handbook of behavior problems of the dog and cat. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2003, pp 117-151. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Crowell-Davis SL, Murray T. Veterinary psychopharmacology. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. Psychopharmacology [in Spanish]. In: Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. (eds). Practical manual of clinical ethology of the cat. Sant Cugat: Multimedica Ediciones Veterinarias, 2017, pp 67-83. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sinn L. Advances in behavioral psychophar-macology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018; 48: 457-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Center SA, Elston TH, Rowland PH, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with oral administration of diazepam in 11 cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 209: 618-625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pageat P, Gaultier E. Current research in canine and feline pheromones. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2003; 33: 187-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. Treatment of redirected aggressiveness [in Spanish]. In: Amat M, Camps T, Le Brech S. (eds). Practical manual of clinical ethology of the cat. Sant Cugat: Multimedica Ediciones Veterinarias, 2017, pp 191-195. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dantzer R. Coping with stress. In: Stanford SC, Salmon P. (eds). Stress from synapse to syndrome. London: Academic Press, 1993, pp 167-187. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Special issues on feline behaviour and problem behaviours