Abstract

Background:

Hospitalizations rates for childhood pneumonia vary widely. Risk-based clinical decision support (CDS) interventions may reduce unwarranted variation.

Methods:

We conducted a pragmatic randomized trial in two US pediatric EDs comparing electronic health record (EHR)-integrated prognostic CDS vs usual care for promoting appropriate ED disposition in children (<18 years) with pneumonia. Encounters were randomized 1:1 to usual care vs custom CDS featuring a validated pneumonia severity score predicting risk for severe in-hospital outcomes. Clinicians retained full decision-making authority. The primary outcome was inappropriate ED disposition, defined as early transition to lower- or higher-level care. Safety and implementation outcomes were also evaluated.

Results:

The study enrolled 536 encounters (269 usual care and 267 CDS). Baseline characteristics were similar across arms. Inappropriate disposition occurred in 3% of usual care encounters and 2% of CDS encounters (aOR 0.99, 95% CI [0.32, 2.95]) Length of stay was also similar and adverse safety outcomes were uncommon in both arms. The tool’s custom user interface and content were viewed as strengths by surveyed clinicians (>70% satisfied). Implementation barriers included intrinsic (e.g., reaching the right person at the right time) and extrinsic factors (i.e., global pandemic).

Conclusions:

EHR-based prognostic CDS did not improve ED disposition decisions for children with pneumonia. Although the intervention’s content was favorably received, low subject accrual and workflow integration problems likely limited effectiveness.

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia accounts for 1–4% of emergency department (ED) visits in children and ranks among the top 3 reasons for pediatric hospitalization annually in the United States (US).1-5 In a study of >2000 pneumonia hospitalizations at three US children’s hospitals, one-third of children were hospitalized for less than 48 hours and nearly 10% for less than 24 hours.1 Some of these hospitalizations were probably unnecessary. Conversely, one-third admitted to intensive care were initially managed on a general ward, suggesting that earlier recognition of impending deterioration could improve outcomes. Others have documented wide institutional-level variation in ED disposition and other management decisions—unexplained by population or case-mix heterogeneity—among children with pneumonia.6,7 Variation in disposition decisions and clinician risk perceptions are also evident among ED clinicians caring for adults with pneumonia.8,9 These findings suggest that clinician preferences, local culture, and inaccurate risk perceptions unduly influence decision-making and may contribute to avoidable harm. New strategies to inform decision-making are needed.

We previously developed and validated a suite of prognostic models to identify risk for severe in-hospital pneumonia outcomes, such as need for intensive care or invasive mechanical ventilation.10,11 Each model estimates risk using a varying number of demographic, clinical, and diagnostic predictor variables, including an electronic health record (EHR) model that constrains predictors to those reliably available at the time of presentation. Each model demonstrated good predictive performance (c-statistic ~0.8) in both the derivation (inpatient) and validation (ED + inpatient) cohorts, with the parsimonious EHR model demonstrating performance on par to the other models. By objectively ascertaining risk for severe pneumonia, EHR-based clinical decision support (CDS) tools featuring these models could inform disposition and other management decisions and improve outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a pragmatic clinical trial at two US children’s hospitals to evaluate effectiveness and measure implementation of EHR-based prognostic CDS vs. usual care for promoting appropriate disposition decisions among pediatric pneumonia encounters in the ED (NCT06033079).

METHODS

Study Population

All study procedures were embedded within routine clinical care, facilitated by EHR-based screening, randomization, exposure to intervention or control conditions, data collection, and outcome ascertainment. The study population included children six months to <18 years presenting to the ED at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) in Nashville, TN, or the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, PA with clinician-confirmed radiographic pneumonia. Children with tracheostomy, cystic fibrosis, or immunosuppression were excluded, as were those hospitalized within the preceding seven days or previously enrolled within the preceding 28 days.

Screening was custom-developed within each site’s EHR – Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) at VUMC and Cerner Millennium (Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, MO) at UPMC. At VUMC, screening used a real-time, natural language processing classification tool to identify suspected pneumonia from chest radiograph reports.12 At UPMC, this approach was infeasible; instead, screening was triggered when a chest radiograph was ordered for encounters with a chief complaint reflecting acute respiratory illness (e.g., fever, cough, fast breathing). At both sites, a positive screen prompted an EHR alert to the ED clinician (faculty and trainee physicians and advanced practice providers) within the encounter to confirm the diagnosis of clinical plus radiographic pneumonia (based on clinician gestalt) and study eligibility. Treating clinicians could choose to confirm eligibility (alert no longer active), be reminded later (alert remained active), or opt themselves out (i.e., not the treating clinician; alert no longer active for that clinician but otherwise remained active). Once eligibility was confirmed, the encounter was considered enrolled. Encounters without confirmed eligibility (non-response or partial, ambiguous responses) were considered unknown. Enrollments accrued from November 2020 to December 2022. The study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by at both institutions.

Prognostic CDS Tool Development

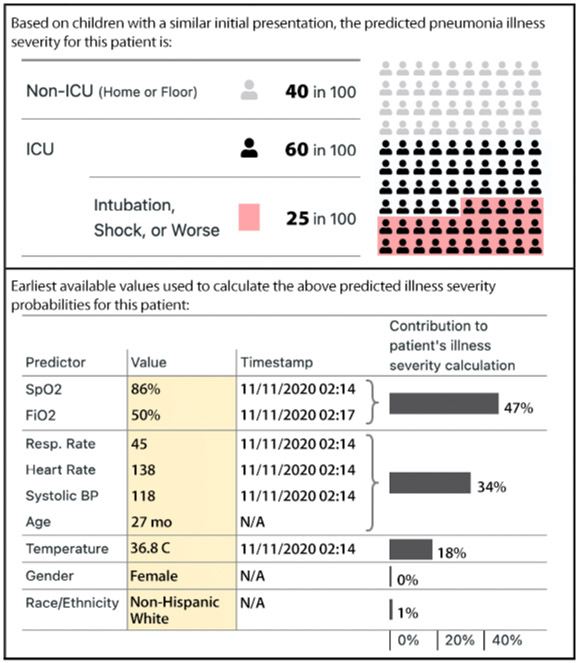

The intervention was an EHR-based prognostic CDS tool designed to communicate personalized risk probabilities for severe pneumonia at the point of care using data collected as early as possible during ED encounter (typically at triage). An iterative, user-centered design process,13,14 including observations, interviews, and usability testing with ED clinicians at both hospitals, was employed to create the tool according to CDS design principles.15-17 These activities highlighted the need for efficiency, transparency, and minimal workflow disruption. Iterative discussions determined the content, timing, and functionality of the CDS tool. This led to the development of a “SMART (Substitutable Medical Applications and Reusable Technologies)-on-FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources)” enabled CDS tool that: 1) identified encounter-level data for each predictor in the EHR model; 2) calculated risk probabilities for moderate/severe, severe, and very severe in-hospital outcomes; and 3) displayed model inputs and risk probabilities using a custom user interface (Figure 1). Trial awareness and education was provided in multiple formats to ED faculty and staff and pediatric and ED resident physicians via administrative meetings and educational conferences, email, and ad hoc one-on-one discussions in the clinical setting. Study personnel and clinician-champions remained engaged with ED providers throughout the trial.

Figure 1. Intervention Custom User Interface Demonstrating Estimated Risk Probabilities and Predictor Values.

Illustrative example of the custom-developed prognostic CDS user interface displaying risk probabilities for severe (intensive care) and very severe (invasive mechanical ventilation, shock, or worse) pneumonia, predictors and values used for score calculation, and the relative contribution (i.e. importance) of each predictor.

Randomization

Eligible encounters were randomized sequentially within each hospital 1:1 to the intervention or control conditions using a predetermined simple randomization sequence. For intervention encounters, ED clinicians were prompted to view the prognostic tool and provided instructions for its use. In the control arm, no decision support was provided. In both arms, treatment and other management recommendations were not provided. Clinicians retained all decision-making authority regarding ED disposition.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was inappropriate initial disposition from the ED. For encounters discharged from the ED, disposition was inappropriate if there was a return visit for persistent or worsening pneumonia resulting in hospitalization within 48 hours of the index discharge. Persistent or worsening pneumonia was defined as the presence of any of the following: documented ill appearance (e.g., toxic, limp, lethargic, irritable, inconsolable), hypoxemia or hypercapnia requiring intervention above baseline needs, hemodynamic instability, sepsis, bacteremia, intervention for pulmonary or other disease-related complications (e.g., pleural drainage procedure or bronchoscopy), need for new or expanded antibiotic therapy, intolerance to enteral nutrition, or acute dehydration requiring sustained parenteral fluid therapy (i.e., maintenance rate or higher). For encounters triaged to the acute care inpatient setting, disposition was inappropriate if: 1) hospital LOS was ≤ 24 hours without objective criteria for hospitalization (persistent or worsening pneumonia; documented concern regarding treatment compliance, ability to monitor at home, or lack of reliable follow up; or hospitalization related to management of comorbidity or concomitant diagnosis), or 2) intensive care was required during the first 24 hours of the encounter. Intensive care disposition was inappropriate if intensive care LOS was ≤ 24 hours and objective criteria for intensive care were not present (use of non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation; measured SpO2 ≤ 92% while receiving a fraction of inspired oxygen ≥ 50%; persistent apnea or concern for impending respiratory failure; fluid refractory shock requiring vasoactive medications; obtundation, stupor, coma, or documented Glasgow Coma Scale ≤ 8; documented need for intensive nursing care; or reason for intensive care related to management of comorbidity or concomitant diagnosis). Outcome adjudication, blinded to treatment assignment, was performed via manual EHR review by trained study staff and finalized by investigators at each site (DJW and JMM).

Safety and Implementation Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included encounter LOS (triage arrival to ED or hospital discharge, measured in hours), 3- and 7-day ED revisits and hospitalizations following index encounter discharge, and in-hospital and post-discharge deaths within 30 days of presentation. Implementation outcomes included the frequency and proportion of screening alerts whereby clinicians confirmed the encounter was study eligible, ineligible, or, if lack of clinician response, unknown. Due to differences in screening methods and data availability, these data were reported by hospital. Following trial closure, post hoc electronic surveys custom-developed by our human-centered design team (Supplemental Figure 1) were distributed to a convenience sample of participating clinicians to capture user perspectives grounded in the five rights of CDS (right information, right person, right time, right format, and right channel) using Likert scales and open-ended responses. Suggestions to enhance the tool and general opinions regarding use of CDS and pragmatic research within the ED environment were also solicited.

Statistical Analysis

A multivariable logistic regression model was fit for the primary outcome using Firth’s penalized likelihood approach to reduce bias due to small sample size.18 Similarly, a reduced set of a priori selected covariates were considered, and included age, sex, race, enrolling site, and calendar month. Analogous models were used for the binary secondary outcomes. A multivariable proportional hazards model was fit for hospital LOS with adjustment for the same covariates. Baseline comparisons between groups and implementation outcomes were compared using Pearson’s chi-square, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or t-tests as appropriate. We anticipated enrolling ~1000 encounters in each arm of the trial. This would allow for the detection of a true absolute difference of ≥3.4% for inappropriate initial disposition at an alpha level of 0.05 with 80% power. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.04 (https://www.R-project.org).

RESULTS

Study Population

The study enrolled 536 ED encounters (median age 4.4 years), including 269 randomized to usual care and 267 to CDS (Table 1; Supplemental Figure 2). Patient characteristics were similar across study arms with 50% girls, 67% white race, 16% black race, and 13% Hispanic ethnicity overall. Comorbidities were common (43%), including 33% of patients with complex chronic comorbidities. Triage risk scores were available for 464 encounters (87%), with a median risk probability of 11% for severe outcome or worse (3% very severe).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Combined N=536 |

Usual care n=269 |

CDS n=267 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolling site | 0.001 | |||

| Vanderbilt | 62% (333) | 69% (185) | 55% (148) | |

| Pittsburgh | 38% (203) | 31% (84) | 45% (119) | |

| Age in years | 4.4 (2.1, 7.4) | 4.4 (2.1, 7.0) | 4.3 (2.1, 7.2) | 0.708 |

| Female sex | 50% (267) | 47% (126) | 53% (141) | 0.167 |

| Race | 0.199 | |||

| White | 67% (361) | 68% (184) | 66% (177) | |

| Black | 16% (86) | 13% (36) | 19% (50) | |

| Asian | 1% (6) | 1% (4) | 1% (2) | |

| Other | 4% (22) | 6% (15) | 3% (7) | |

| Unknown | 11% (61) | 11% (30) | 12% (31) | |

| Hispanic/Latinoethnicity | 13% (68) | 12% (32) | 13% (36) | 0.47 |

| Comorbidity1 (n=496) | 0.702 | |||

| Non-chronic | 57% (282) | 59% (150) | 55% (132) | |

| Non-complex chronic | 10% (51) | 10% (26) | 10% (25) | |

| Complex chronic | 33% (163) | 31% (80) | 35% (83) | |

| Insurance | 0.767 | |||

| Public | 55% (295) | 57% (153) | 53% (142) | |

| Private | 37% (196) | 35% (95) | 38% (101) | |

| Multiple | 7% (36) | 6% (16) | 7% (20) | |

| None | 2% (9) | 2% (5) | 1% (4) | |

| Triage vital signs | ||||

| Temperature (C) (n=535) | 37.3 (36.8, 38.1) | 37.5 (36.9, 38.2) | 37.2 (36.8, 38.1) | 0.017 |

| Heart rate (n=533) | 136 (118, 155) | 139 (121, 154) | 135 (117, 155) | 0.326 |

| Respiratory rate (n=528) | 31 (24, 40) | 30 (24, 40) | 32 (24, 41) | 0.725 |

| Systolic BP (n=488) | 108 (100, 117) | 108 (99, 117) | 108 (100, 117) | 0.582 |

| SpO2:FiO2 ratio (n=447) | 457.1 (447.6, 466.7) | 457.1 (442.9, 466.7) | 457.1 (447.6, 466.7) | 0.481 |

| Triage risk2 (n=464) | ||||

| Severe or very severe | 0.10 (0.05, 0.19) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.20) | 0.10 (0.05, 0.18) | 0.275 |

| Very severe | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.05) | 0.275 |

| ED disposition | 0.233 | |||

| Outpatient | 40% (216) | 40% (107) | 41% (109) | |

| Inpatient | 39% (209) | 42% (113) | 36% (96) | |

| Intensive Care Unit | 21% (111) | 18% (49) | 23% (62) |

Categorical data presented as % (frequency) and continuous data as median (interquartile range); 1Defined using the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm; 2Triage risk probabilities for severe or very severe pneumonia and very severe pneumonia represent risk estimates obtained from the predictive model featured in this trial (see references 9 and 10); Abbreviations: CDS, Clinical Decision Support; IQR, interquartile range

Appropriateness of ED Disposition

Overall, 40% of encounters were discharged home, 39% admitted to inpatient acute care, and 21% to intensive care with similar distributions across arms. Inappropriate ED disposition occurred in 13 (2%) encounters, including 3% of usual care encounters and 2% of CDS encounters (difference in proportions −0.36%, 95% CI [−0.036, 0.028]; aOR 0.99, 95% CI [0.32, 2.95])(Table 2). Of the 13 encounters with inappropriate disposition, 10 (77%) were for hospitalizations <24 hours without objective admission criteria, one (8%) was for admission to intensive care for <24 hours without objective criteria, and two (15%) were for encounters requiring early care escalation, including one hospitalization following ED discharge and one transfer to intensive care following acute care hospitalization.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Study Arm

| Outcomes | Combined | Usual care | CDS | Adjusted odds ratio or hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=536 | n=269 | n=269 | ||

| Primary Outcome | ||||

| Inappropriate disposition | 2% (13) | 3% (7) | 2% (6) | 0.99 (0.32, 2.95) |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

| Length of stay in hours, Median (interquartile range) | 22.9 (5.3, 55.2) | 23.2 (5.3, 63.2) | 22.4 (5.2, 50.9) | 1.10 (0.92, 1.31) |

| ED revisit (3 days) | 3% (16) | 4% (10) | 2% (6) | 0.86 (0.30, 2.37) |

| ED revisit (7 days) | 4% (24) | 6% (15) | 3% (9) | 0.78 (0.32, 1.82) |

| Hospitalization (3 days) | 2% (9) | 1% (3) | 2% (6) | 1.50 (0.42, 6.24) |

| Hospitalization (7 days) | 5% (26) | 4% (14) | 5% (12) | 0.81 (0.36, 1.80) |

| Death within 30 days | 1% (7) | 1% (3) | 1% (4) | 1.72 (0.41, 7.90) |

Multivariable logistic regression models were fit for categorical outcomes using Firth’s penalized likelihood approach to reduce bias of the maximum likelihood estimation due to small sample size. The covariates included age, sex, race, enrolling site, and month. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was fitted for hospital length of stay with adjustment for the same covariates. Abbreviations: CDS, Clinical Decision Support; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; ED Emergency Department

Safety Outcomes

Median ED LOS (4.2 vs. 4.2 hours, p=0.66) and total encounter LOS 23.2 vs 22.4 hours, aHR 1.10, 95% CI [0.92, 1.31]) were similar between arms ((Table 2). ED revisits and hospitalizations at 3- and 7-days post-index encounter discharge were uncommon, occurring in <5% of all encounters in both arms. There were 7 (1%) deaths.

Implementation Outcomes

At VUMC, 25% of the 1310 screened encounters were confirmed by clinicians as study eligible (six screening alerts per encounter) and 16% were confirmed ineligible (four screening alerts per encounter) (Table 3A). Eligibility was not confirmed due to lack of ED clinician engagement (no or incomplete response to screening alerts) in 59% of encounters (three alerts per encounter); the proportion of encounters without confirmed eligibility increased over the study period (Figures 2A). At UPMC, 6% of the 3117 screened encounters were confirmed eligible, 19% were confirmed ineligible, and eligibility was not confirmed for 74% (Table 3B, Figure 2B).

Table 3A.

Screening and Enrollment Data, By Encounter (VUMC)

| Eligibility of screened encounters 1 | Usual care n=673 |

CDS n=637 |

Combined N=1310 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible | 27% (185) | 23% (148) | 25% (333) |

| Alerts per encounter, Mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 7.8 ± 3.9 | 6.4 ± 3.9 |

| Ineligible | 16% (106) | 16% (99) | 16% (205) |

| Alerts per encounter, Mean ± SD | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.8 |

| Unknown | 57% (382) | 61% (390) | 59% (772) |

| Alerts per encounter, Mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

A positive screen was defined as ≥ 27% probability of pneumonia estimated using natural language processing machine learning algorithm of radiologist interpretation of chest radiograph; Abbreviations: VUMC, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; CDS, Clinical Decision Support; SD, Standard Deviation

Figure 2. Eligibility of Screened Encounters Over the Study Period at VUMC (A) and UPMC (B).

2A. A positive screen was defined as ≥ 27% probability of pneumonia estimated using natural language processing machine learning algorithm of radiologist interpretation of chest radiograph; Eligibility was confirmed by clinicians. Encounters without clinician confirmation were considered unknown.

2B. A positive screen was defined as any encounter with a chief complaint of suspected acute respiratory infection (e.g., fever, cough, fast breathing) plus an order for a chest radiograph; Frequency of repeated screening alerts not available; Eligibility was confirmed by clinicians Encounters without clinician confirmation were considered unknown.

Table 3B.

Screening and Enrollment Data, By Encounter (UPMC)

| Eligibility of screened encounters 1 | Usual care n=1547 |

CDS n=1570 |

Combined N=3117 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible | 5% (84) | 7% (117) | 6% (201) |

| Ineligible | 19% (289) | 19% (305) | 19% (594) |

| Unknown | 76% (1174) | 73% (1148) | 74% (2322) |

A positive screen was defined as any encounter with a chief complaint of suspected acute respiratory infection (e.g., fever, cough, fast breathing) plus an order for a chest radiograph; Frequency of repeated screening alerts not available; Abbreviations: UPMC, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; CDS, Clinical Decision Support

Thirty ED clinicians (10 ED faculty, 5 ED fellows, 10 pediatrics residents; 18 with >5 years ED experience; 22 from VUMC and 8 from UPMC) responded to the post-trial survey. When asked for general opinions regarding CDS in the ED (Supplemental Figure 3A), >80% recorded “favorable” or “very favorable” responses for order sets (97%), web-based applications and calculators (93%), practice guidelines and pathways (86%), and online reference resources (83%). Risk scores and prognostic content were rated favorably by 57% of respondents. Alerts and pop-up windows were the least favored with only 31% rating favorably and an equal proportion rating as “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable.” When asked about general opinions regarding clinical research embedded within the ED, 67% of responses were favorable; the remaining respondents were neutral with no unfavorable responses.

Among those responding as “familiar” or “very familiar” with the CDS tool featured in the trial (n=14; Supplemental Figure 3B), 57% were satisfied with “to whom the risk information was presented,” while only 29% were satisfied with “when the risk information was presented.” Most were satisfied with “what information was presented” (71%) and “how information was presented” (79%).

DISCUSSION

We sought to determine if EHR-integrated CDS equipped with objective risk information improves ED disposition for pneumonia. The primary endpoint of inappropriate ED disposition occurred in ≤3% of encounters in both arms. Encounter LOS was approximately 24 hours in both arms, with 3- or 7-day ED revisits or hospitalizations occurring in <5% and deaths in <1%. Surveyed clinicians expressed predominantly favorable opinions regarding the CDS user interface and content, although important workflow barriers were identified that likely hindered effectiveness.

There are inherent challenges to defining appropriateness of ED disposition as many determinants influence triage decisions, including patient (e.g., baseline health, acute illness severity), clinician (e.g., risk tolerance, cognitive bias), institutional (e.g., ED acuity, bed capacity, flow, culture), and sociocultural (e.g., caregiver preferences, transportation, follow-up availability) factors. Regardless of the contributors, preventable disparities and harm associated with inappropriate disposition decisions should be eliminated. Our outcome was designed to evaluate the need for hospitalization and intensive care using objective criteria. By collating and sharing this information at the point of care, we hypothesized that risk-based CDS would improve outcomes. Unfortunately, lower than anticipated subject accrual, resulting from factors intrinsic to the study’s pragmatic design, as well as external factors (i.e., global pandemic), challenged our ability to detect differences. Thus, our findings may reflect an error of omission (i.e., implementation failure). The primary endpoint of inappropriate disposition was also infrequently observed. Overcoming these implementation barriers and testing intervention efficacy in larger, more heterogeneous populations—across differing institutional environments and clinician profiles—is an important next step in our work.

Implementation is a critical determinant of effectiveness. Viewed through Osheroff’s “five rights of CDS” framework,19 successes and challenges were evident. In considering “information,” “channel,” and “format,” our tool featured an EHR-integrated calculator that estimated disease-specific probabilities for intensive care and respiratory failure, shock, or death. Most clinicians surveyed viewed this information favorably, but some expressed ambivalence towards its utility. For example, the tool did not estimate risk for hospitalization which may hamper clinician interpretation. Similarly, it did not address the full spectrum of determinants influencing disposition decision-making (e.g., functional status, social risk). Nonetheless, our approach mirrors other clinical risk-based tools, including in adult pneumonia,20-23 where severity scores predicting 30-day mortality and respiratory failure or shock have safely reduced hospitalizations among low-risk patients and improved guideline-concordant antibiotic management.24-27 Refining the tool to better capture baseline health and social risk data, translate and apply prognostic content, and leverage risk stratification to inform key decisions beyond disposition (e.g., antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship), may boost utility.

Leveraging the EHR to screen, enroll, and assess outcomes was essential as it allowed the trial to continue uninterrupted amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The iterative, user-centered design process allowed for CDS co-production between the research, clinical, and health information technology teams to maximize utility. Commercial EHR system constraints led us to develop a custom, SMART-on-FHIR application to assimilate and present risk information using EHR-generated data within a custom user interface. This approach uses common data standards to maximize interoperability, while allowing for custom development of important design features that are EHR vendor- and institution-agnostic. These design decisions were crucial. Supporting this assertion, surveyed clinicians expressed favorable views of EHR-based CDS, in general, and our tool’s user interface specifically.

Barriers were evident in reaching the “right people,” at the “right time,” and in the “right format.” These are highlighted by the high frequency of repeated screening alerts and screening failures without eligibility confirmation, as well as post-trial clinician surveys. While we endeavored to follow CDS design standards, practical and technical constraints persisted. For example, reliance on natural language processing to parse radiology reports delayed screening alerts and subsequent provision of risk information. While this approach has theoretical advantages (i.e., enhanced screening specificity without sacrificing sensitivity), in practice it was often ineffective due to timing delays. In comparison, reliance on an imaging order alone may create excessive noise and workflow disruption. Embedded predictive modeling using multiple triage data elements (e.g., chief complaint, vital signs, nursing assessment are typically documented within 30 minutes of triage),28 or silent screening and randomization approaches could overcome the dual challenges of screening accuracy and timeliness. Second, severity scores were missing at triage in approximately 15% of subjects due to missing clinical data (e.g., vital signs). Third, screening alerts sometimes fired for non-target users or at the wrong time (e.g., after leaving the ED). Fourth, clinicians were often required to interrupt their workflow to confirm findings (i.e., imaging results), gather additional data, or view risk information. It will be important to address these issues to ensure reliable delivery of risk information to the appropriate clinicians as triage decisions are being made. Practical considerations also influenced us to retain an interruptive screening alert confirming study eligibility that no doubt was a key contributor to screening failures. Designing non-obtrusive, reusable infrastructure to support EHR-based clinical trials would facilitate trial recruitment and retention, thereby enhancing rigor, efficiency, and accelerating discovery and care innovation.

Limitations of the study included its conduct during a global pandemic that substantially altered respiratory disease epidemiology and hospital utilization.30 This undoubtedly contributed to low participant accrual. Associated factors, including increased diagnostic uncertainty and clinician “pandemic fatigue,” may also have influenced CDS utilization. Enrolled encounters may not represent the full population of children with pneumonia within or across sites, including those who may not have had imaging performed. Similarly, post-trial surveys were completed by a convenience sample and may not reflect the full scope of clinician views. Some clinicians may have experienced both control and intervention conditions during the trial, raising concern for contamination; such bias would underestimate intervention effectiveness. The intervention, however, presented risk probabilities for each encounter not otherwise available, suggesting contamination would be minimal.

To conclude, in this clinical trial, EHR-based prognostic CDS did not improve disposition decisions for children with pneumonia. Although the intervention’s prognostic information was favorable to clinicians, low subject accrual and workflow integration problems limited effectiveness. Overcoming these challenges and enhancing content to best capture user needs are required before ascertaining the utility of prognostic CDS for improving care delivery for pediatric pneumonia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the children and their families who participated in the study. We also thank the clinicians and pediatric emergency departments at both institutions that contributed to participant recruitment, members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, and the following collaborators from VUMC: Zameer Lodhi, MS; Tom Wilson, MS, PharmD; Leigh Price, MA; Kathryn Edwards, MD, and Ritu Banerjee, MD, PhD; and UPMC: Jennifer Opal, RN; Scott Coglio; Lisa Meyers, RN; and Henry Ogoe, PhD.

Funding/Support:

Drs. Williams, Freundlich, and Antoon received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI125642, K23HL148640, and K23AI168496). The study was also partly funded by a grant from the NCATS to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (UL1TR002243).

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Abbreviations

- CAP

community-acquired pneumonia

- ED

emergency department

- EHR

electronic health record

- CDS

clinical decision support

- US

United States of America

- UPMC

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

- LOS

length of stay

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures): Derek Williams reports in-kind research support from BioMerieux for unrelated work; Judith Martin receives funding to the University from: Merck, Sharp and Dome, National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Moderna for unrelated work; Carlos Grijalva reports consultancy fees from Pfizer, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur; and grants from Campbell Alliance/Syneos Health and Sanofi for unrelated work. Robert Freundlich reports stock in 3M and consulting from Oak Hill Clinical Informatics for unrelated work. Matthew Weinger consults for Fresenius Kabi USA and is the PI on an investigator-initiated grant from Merck for unrelated work.

Clinical Trials Registration: NCT06033079

Data Sharing Statement:

Deidentified individual participant data will not be made available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee GE, Lorch SA, Sheffler-Collins S, Kronman MP, Shah SS. National hospitalization trends for pediatric pneumonia and associated complications. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):204–213. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AHRQ. National Estimates on Use of Hospitals by Children from the HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID). Published 2012. Accessed January 12, 2014. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

- 4.Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Self WH, Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, et al. Rates of emergency department visits due to pneumonia in the United States, July 2006-June 2009. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(9):957–960. doi: 10.1111/acem.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539–545. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brogan TV, Hall M, Williams DJ, et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect J. 2012;31(10):1036–1041. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825f2b10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean NC, Jones BE, Jones JP, et al. Impact of an Electronic Clinical Decision Support Tool for Emergency Department Patients With Pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. Published online February 26, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean NC, Jones JP, Aronsky D, et al. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoon JW, Nian H, Ampofo K, et al. Validation of Childhood Pneumonia Prognostic Models for Use in Emergency Care Settings. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2023;12(8):451–458. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piad054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DJ, Zhu Y, Grijalva CG, et al. Predicting Severe Pneumonia Outcomes in Children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JC, Spann A, McCoy AB, et al. Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning to Enable Clinical Decision Support for Treatment of Pediatric Pneumonia. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2020;2020:1130–1139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuler D, Namioka A. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices. L. Erlbaum Associates; 1993. Accessed November 10, 2023. http://www.gbv.de/dms/bowker/toc/9780805809510.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinger M, Wiklund M, Gardner-Bonneau D. Handbook of Human Factors in Medical Device Design. CRC Press/Taylor Francis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2003;10(6):523–530. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller A, Koola JD, Matheny ME, et al. Application of contextual design methods to inform targeted clinical decision support interventions in sub-specialty care environments. Int J Med Inf. 2018;117:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward MJ, Chavis B, Banerjee R, Katz S, Anders S. User-Centered Design in Pediatric Acute Care Settings Antimicrobial Stewardship. Appl Clin Inform. 2021;12(1):34–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1718757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med. 2002;21(16):2409–2419. doi: 10.1002/sim.1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osheroff JA, Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. Improving Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support : An Implementer’s Guide. 2nd ed. HIMSS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(4):243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim WS, Lewis S, Macfarlane JT. Severity prediction rules in community acquired pneumonia: a validation study. Thorax. 2000;55(3):219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):375–384. doi: 10.1086/589754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espana PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, et al. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(11):1249–1256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-177OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renaud B, Coma E, Labarere J, et al. Routine use of the Pneumonia Severity Index for guiding the site-of-treatment decision of patients with pneumonia in the emergency department: a multicenter, prospective, observational, controlled cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(1):41–49. doi: 10.1086/509331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atlas SJ, Benzer TI, Borowsky LH, et al. Safely increasing the proportion of patients with community-acquired pneumonia treated as outpatients: an interventional trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(12):1350–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, Wong CJ, Vandervoort MK, Feagan BG. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. CAPITAL Study Investigators. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin. JAMA. 2000;283(6):749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, Choudhury G, Mandal P, Hill AT. Safety and efficacy of CURB65-guided antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. Published online November 16, 2010. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savard N, Bédard L, Allard R, Buckeridge DL. Using age, triage score, and disposition data from emergency department electronic records to improve Influenza-like illness surveillance. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(3):688–696. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choe J, Lee SM, Hwang HJ, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Lung Imaging. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;43(06):946–960. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1755571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoon JW, Williams DJ, Thurm C, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Changes in Healthcare Utilization for Pediatric Respiratory and Nonrespiratory Illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(5):294–297. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified individual participant data will not be made available.