Abstract

Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, nitrosylation, and pupylation modulate multiple cellular processes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. While protein methylation at lysine and arginine residues is widespread in eukaryotes, to date only two methylated proteins in Mtb have been identified. Here, we report the identification of methylation at lysine and/or arginine residues in nine mycobacterial proteins. Among the proteins identified, we chose MtrA, an essential response regulator of a two-component signaling system, which gets methylated on multiple lysine and arginine residues to examine the functional consequences of methylation. While methylation of K207 confers a marginal decrease in the DNA-binding ability of MtrA, methylation of R122 or K204 significantly reduces the interaction with the DNA. Overexpression of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase (SahH), an enzyme that modulates the levels of S-adenosyl methionine in mycobacteria decreases the extent of MtrA methylation. Most importantly, we show that decreased MtrA methylation results in transcriptional activation of mtrA and sahH promoters. Collectively, we identify novel methylated proteins, expand the list of modifications in mycobacteria by adding arginine methylation, and show that methylation regulates MtrA activity. We propose that protein methylation could be a more prevalent modification in mycobacterial proteins.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis, is responsible for nearly one million deaths annually around the globe [1]. It resides dormant in the host for decades without detection and when the immune system wanes, it proliferates and causes active disease. The adeptness of mycobacteria to hijack the host cell can be attributed to the fine-tuning of signaling pathways. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) including serine/threonine phosphorylation, nitrosylation, and pupylation (addition of prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein) play an important role in regulating mycobacterial physiology and virulence [2–6]. While there are few specific examples of how these modifications affect the function of a protein, more mechanistic insight is required to delineate their regulatory roles. In addition to these modifications, proteins can be post-translationally modified by the addition of methyl groups, catalyzed by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) dependent methyltransferases [7], at the ε-amino group of lysine, guanidino group of arginine, or oxygen in the carboxylate side chain of glutamate [8–10]. Glutamate methylation of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins play a biologically conserved role in chemotaxis and provide rotational directionality to bacteria [11].

In eukaryotes, methylation of histone proteins at specific lysine residues regulates chromatin architecture and transcription, and aberrant methylation is associated with aging and cancer [12]. Arginine methylation is the most extensively studied protein modification in eukaryotes and its role in DNA repair, RNA metabolism, and transcriptional repair is well established [13]. Guanidino group of arginine is involved in the interaction with DNA; the addition of methyl group directly affects the activity of proteins. Methylation of Sam68 (an adapter protein for Src kinases during mitosis) at arginine residue restrains it’s binding to Src homology 3 (SH3) domain of phospholipase Cγ−1 and methylation at arginine and lysine residues of CHD1 (chromo-helicase/ATPase DNA-binding protein 1) results in a significant decrease in its binding affinity to DNA [8]. Several non-histone proteins, mainly transcription factors and histone- or chromatin-associated proteins are also regulated by methylation [12,14].

In bacteria, however, our understanding of the functional role of lysine or arginine methylation is limited [9]. Lysine methylation is associated with bacterial cell motility of Synechocystis sp. and with host colonization and disease initiation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa [15]. A recent proteomics study has identified abundant lysine and arginine methylation in Escherichia coli [16]. In Mtb, lysine residues of heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin (HBHA) and histone-like protein (HupB) have been shown to undergo methylation but there are no reports of arginine methylation. HBHA and HupB are both critical for infection by Mtb [17] and their methylation imparts protease resistance and thus increased stability, suggesting a role for methylation in disease pathogenesis [18]. Methylation reactions are catalyzed by SAM-dependent methyltransferases where S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH) and consequently homocysteine (Hcy) are generated as by-products. Methyltransferase reactions are dependent on the presence of balanced amounts of SAM and SAH as they are prone to SAH-mediated inhibition. Under normal conditions, SAH levels are regulated using SahH-mediated reversible hydrolysis of SAH to Hcy. We have previously shown that perturbation of levels of Mtb SahH impacts metabolic levels of Hcy and may affect SAH, a potent inhibitor of methyltransferases [19].

In this manuscript, we set out to determine the prevalence of methylation in Mtb proteins. Nine among the 72 proteins tested were found to be methylated either on lysine or arginine residues. To determine the functional consequences of methylation, we chose MtrA; an essential response regulator of the MtrB–MtrA two-component system (TCS) that regulates cell cycle progression. We show that methylation perturbs MtrA DNA-binding activity leading to modulation of its own expression. We also reveal that SahH, an enzyme that is required for SAM synthesis, modulates MtrA methylation. Taken together, we propose that methylation of lysine and arginine residues is an important additional regulatory modification in Mtb.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

E. coli strains DH5α (Novagen) and BL21-DE3 (Stratagene) were used for cloning and expression of recombinant proteins, respectively. Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 (Msm) and Mtb H37Rv were maintained in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco, BD) containing 10% ADC (albumin/dextrose/catalase) and 0.05% Tween-80 (Merck, U.S.A.), supplemented with 25 μg/ml kanamycin or 50 μg/ml apramycin when required. For assessing the effect of homocysteine (Hcy) on bacterial growth, Msm cells were grown in Sauton’s minimal medium supplemented with 0–0.8 mM DL-homocysteine (Sigma–Aldrich) at an initial A600 of 0.01. Absorbance was measured up to 36 h and colony-forming units (CFUs) were enumerated at 25 h. Reagents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich unless otherwise mentioned.

Generation of plasmid constructs

We selected 180 protein-coding genes from Mtb genome representing a random set across various functional classes (Supplementary Figure S1). Genes involved in regulation and information processing were over-represented in the list, while conserved hypotheticals and PE/PPE genes (encoding proteins containing Proline–Glutamate or Proline–Proline–Glutamate motifs) were under-represented. We did not select any gene from the categories stable RNAs, insertion sequences and phages, and those with unknown function. The generation of recombinant plasmids using the shuttle vector pVV16 was explained previously [20]. The recombinant clones (2 μg) were transformed individually in Msm. Mtb H37Rv genomic DNA was used to amplify mtrA (rv3246c; 687 bp) using forward and reverse primers containing NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. Digested PCR product was cloned into either pVV16 or the E. coli expression vector pET28a and recombinants were selected on kanamycin. E. coli K12 genomic DNA was used to amplify envZ (1353 bp) and cloned into pMAL-c2x at BamHI and HindIII restriction sites, recombinants were selected on ampicillin. Site-specific mutants of pVV16-mtrA and pET28a-mtrA were generated using QuikChange® XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mtb sahH (rv3248c; 1488 bp) was cloned in pVV16 vector at NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. All constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing (Invitrogen). Information about primers and plasmids used in this study is compiled in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

List of primers used in this study

| Primer name1 | Primer sequence (5′→3′)2 |

|---|---|

| MtrA F | GTCCCGATGTGGTGACATATGGACACCATGAGGC (NdeI) |

| MtrA R | GCATCGTCGCCGGCGAAGCTTCGGAGGTCCGGCCTTG (HindIII) |

| EnvZ F | ACGGCTCGGATCCATGAGGCGATTGCGCTTC (BamHI) |

| EnvZ R | CCTTCGCCTCAAGCTTATTTACCCTTCTTTTG (HindIII) |

| MtrAK204M F | GTCCAGCGTCTGCGGGCCATGGTCGAAAAGGATCCCGAG |

| MtrAK204M R | CTCGGGATCCTTTTCGACCATGGCCCGCAGACGCTGGAC |

| MtrAK207M F | CTGCGGGCCAAGGTCGAAATGGATCCCGAGAACCCGACTG |

| MtrAK207M R | CAGTCGGGTTCTCGGGATCCATTTCGACCTTGGCCCGCAG |

| MtrAR122M F | GGTGCGGGCGCGGCTGCGCATGAACGACGACGAACCCGCCG |

| MtrAR122M R | CGGCGGGTTCGTCGTCGTTCATGCGCAGCCGCGCCCGCACC |

| SahH F | GGATGAAAGCCCATATGACCGGAAATTTGG (NdeI) |

| SahH R | TGGGCGATTTTGCGTAAGCTTGCGGGTGGGA (HindIII) |

| OriC F | CACGGCGTGTTCTTCCGAC |

| OriC R | GTCGGAGTTGTGGATGACGG |

| SahHMs-pr F | GCGCCTGGCGATGAGCTACG |

| SahHMs-pr R | GCACACTCATGCCGACAACC |

| SahHMt-pr F | GCGGCTGTGCTTGAGCTACG |

| SahHMt-pr R | GCTCACAGGGATCCGAGCG |

| MtrART F | CCATCGTTCTGCGTGGTGAG |

| MtrART R | GGTCAGCATGACGATCGGC |

| SahH-RT F | GCGCCAAGAAGATCAACATC |

| SahH-RT R | CTCGGACAGCACGATGATC |

| SigA-RT F | CGTTCCTCGACCTCATCCA |

| SigA-RT R | GCCCTTGGTGTAGTCGAACTTC |

| 16S-RT F | AATTCGATGCAACGCGAAGA |

| 16S-RT R | GCGGGACTTAACCCAACATC |

‘F’ denotes forward primer and ‘R’ denotes reverse primer;

Restriction sites/mutations are underlined and Restriction enzymes are mentioned in parenthesis.

Table 2.

List of plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid construct | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pVV16 | Mycobacterial expression vector with kanamycin resistance | [22] |

| pET28a | E. coli expression vector with His6-tag and kanamycin resistance | Novagen |

| pMAL-c2x | E. coli expression vector with MBP-tag and ampicillin resistance | New England BioLabs |

| pSET152 | Mycobacterial integrative vector with apramycin resistance | [21] |

For analyzing the effect of SahH on MtrA methylation, the genes encoding these proteins were co-expressed in Msm. Mtb sahH was cloned in mycobacterial integrative vector pSET152 [21]. For this, pVV-sahH was digested with HindIII and the ends were made blunt. A second digestion with XbaI yielded 1.86 kb fragment containing sahH under a heat shock gene promoter (hsp60). This fragment was ligated to pSET152 pre-digested with XbaI and EcoRV. pSET-sahH or pSET152 (2 mg each) was electroporated in Msm competent cells and apramycin resistant transformants were selected. pVV16-mtrA plasmid (2 mg) was then electroporated in competent Msm cells harboring either pSET152 or pSET152-sahH and the positive clones were selected on apramycin and kanamycin. His6-MtrA was purified from cells containing both pSET-sahH and pVV16-mtrA and used for Western blotting.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

For expression and purification of proteins from Msm, recombinant clones (2 μg) in pVV16 vector were electroporated and recombinants were selected on kanamycin. Expressed proteins were purified as described before [20]. Briefly, Msm cells expressing recombinant proteins were cultured individually in 200 ml of 7H9 medium and grown till mid-log phase (A600 ~ 0.8). The cells were harvested and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma–Aldrich), and protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). The lysates were centrifuged at 14 000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min, and the resulting supernatants containing His6-tagged proteins were incubated with Ni2+-NTA resin (Qiagen). The resin was washed thoroughly with a wash buffer (1X PBS, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol) and proteins were eluted in the elution buffer (1X PBS, 1 mM PMSF, 200 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol).

For purifying His6-MtrA from Mtb, pVV16-mtrA construct (2 μg) was electroporated and recombinants were selected on kanamycin. Recombinant cells were cultured in 200 ml of 7H9 media and grown till mid-log phase (A600 ~ 0.8). The cells were harvested and lysed by bead beating in lysis buffer (1X Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/ml lysozyme, and protease inhibitor cocktail) using 0.1 mm zirconium beads (Biospec). The lysate was centrifuged and the resulting supernatant containing His6-MtrA was incubated with Co2+ superflow resin (Thermo Scientific). The resin was washed thoroughly with wash buffer (1X TBS, 1 mM PMSF, and 10 mM imidazole) and the protein was eluted in the elution buffer (1X PBS, 1 mM PMSF, and 300 mM imidazole).

For protein expression in E. coli, pET28a- or pMAL-c2x-based plasmids (100 ng) were transformed, and proteins were overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The recombinant His6-tagged proteins were purified using Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen) and MBP (maltose-binding protein)-tagged EnvZ was purified using Amylose resin (NEB) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of purified proteins was estimated by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Purified proteins were resolved on SDS–PAGE and analyzed by staining with coomassie brilliant blue R250 (Sigma–Aldrich).

To analyze the effect of Hcy on MtrA methylation, Msm cells harboring pVV16-mtrA were grown in Sauton’s medium containing 0.4 mM Hcy. Cells were grown up to A600 ~ 0.8, harvested, and subjected to Ni2+-NTA chromatography for purification of His6-MtrA, as described above. The proteins were later analyzed by Western blotting. For normalization, His6-MtrA was purified from cells grown without the addition of Hcy.

Western blot analysis

Purified proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma–Aldrich) in 1X PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma–Aldrich) (1X PBST20) overnight at 4°C. After blocking, the blots were washed thrice with 1X PBST20 followed by incubation with antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Methyllysine immunoblots were developed by two separate antibodies from different manufacturers and one representative blot is shown in Figure 1a. The antibodies were: anti-methyllysine antibody from Abcam (ab23366; 1 : 10 000 dilution) and pan anti-mono, dimethyllysine antibody from PTM Biolabs (PTM-602; 1 : 2000 dilution). Other antibodies and their dilutions used were: anti-MtrA antibody (1 : 15 000 dilution; generated in the laboratory), anti-acetyllysine antibody (Cell Signaling; 1 : 3000 dilution), pan anti-succinyllysine antibody (PTM Biolabs; 1 : 2000 dilution), HRP-conjugated anti-His6 antibody (Abcam; 1 : 20 000 dilution), and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Bangalore Genei; 1 : 20 000 dilution). According to the manufacturer, the methyllysine antibodies used here can detect mono- or dimethyllysine with no cross-reactivity to acetyllysine. Antibodies to acetyllysine and succinyllysine have been successfully used in our previous study [20]. Antibodies against recombinant Mtb His6-MtrA were raised in Rabbits with the help of Dr. A. K. Goel (DRDE, Gwalior, India). The specificity of anti-MtrA antibody was validated by using a preparation of purified MtrA protein that had been confirmed by mass spectrometry. Also, these antibodies identified a single protein band corresponding to MtrA when whole cell lysate preparations of Mtb were probed. Anti Ef-Tu antibodies were used as previously mentioned [22]. Immunoblots were developed using Immobilon™ western chemiluminescent HRP substrate kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of immunoblots was performed using ImageJ software [23].

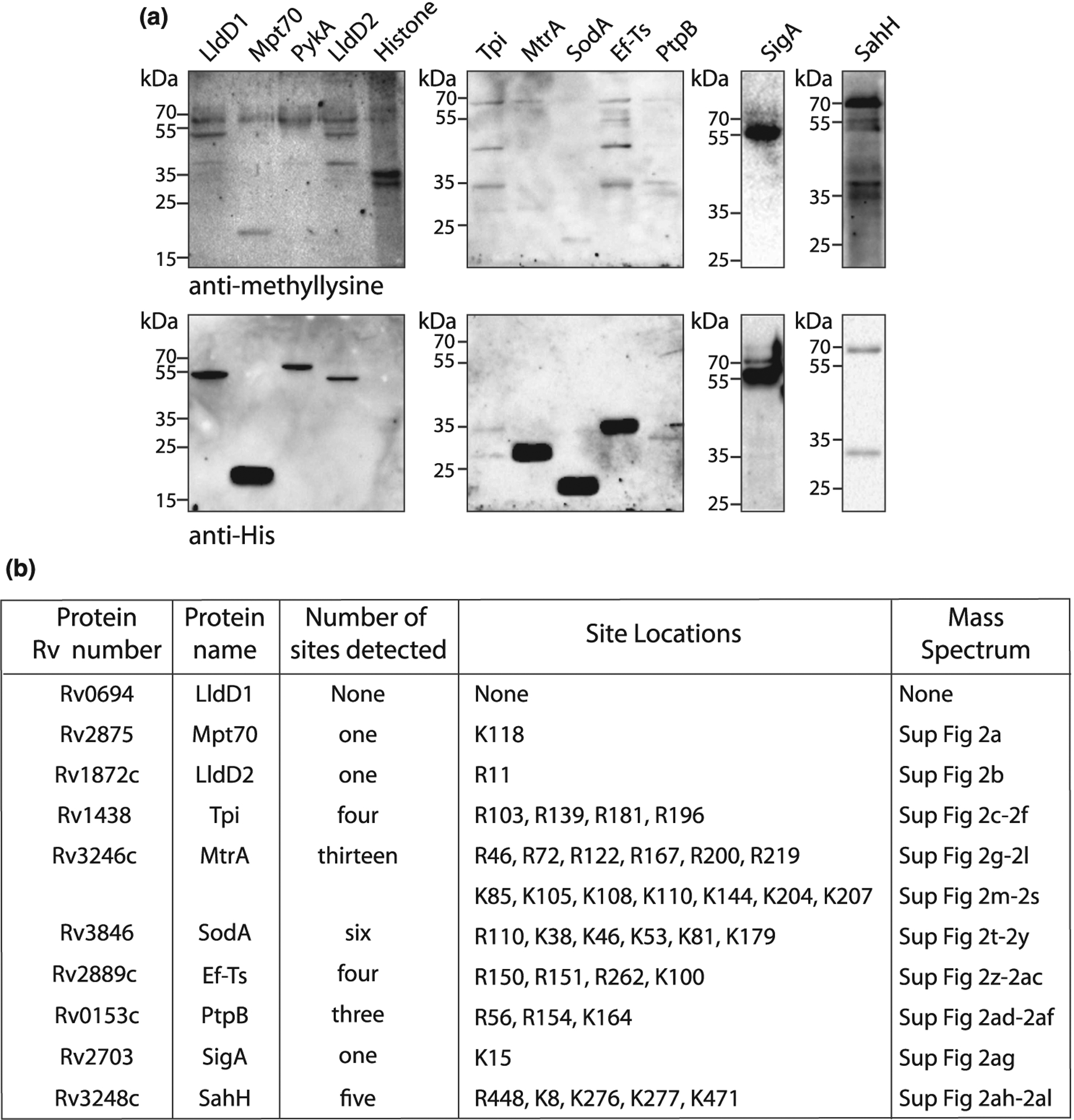

Figure 1. Multiple Mtb proteins are methylated on lysine and arginine residues.

(a) Ten recombinant proteins containing His6-tag were purified using Ni2+-NTA beads from Msm. Purified proteins were loaded on SDS–PAGE, transferred on nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-methyllysine or anti-His6 antibody. (b) Table shows the number and location of methylation sites in the recombinant proteins identified by mass spectrometry. The corresponding supplementary image number of mass spectra is also mentioned.

Mass spectrometry

Recombinant Mtb proteins purified from Msm were resolved on 12% SDS–PAGE and stained with coomassie brilliant blue R250. The stained bands were sliced from the polyacrylamide gel and subjected to in-gel reduction, carbamidomethylation, and an overnight tryptic digestion at 37°C. Alternatively, protein samples were subjected to chloroform-methanol precipitation and pooled before in-solution digestion and single-shot analysis. Mass spectrometry to identify protein methylation was essentially performed as described [24]. Peptides were separated on a 50 cm reversed-phase column (75 mm inner diameter, packed in-house with ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ 1.9 mm resin [Dr. Maisch GmbH]) over a 60- or 120-min gradient using the Proxeon Ultra EASY-nLC system. The LC system was directly coupled online with a Q Exactive HF instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) via a nano-electrospray source. Full scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer with resolution 60 000 at 200 m/z. For the full scans, 3E6 ions were accumulated within a maximum injection time of 120 ms and detected in the Orbitrap analyzer. The 10 most intense ions were sequentially isolated to a target value of 1e5 with a maximum injection time of 120 ms and fragmented by HCD in the collision cell (normalized collision energy of 25%) and detected in the Orbitrap analyzer at 30 000 resolution. Raw mass spectrometric data were analyzed in the MaxQuant environment v.1.5.3.31 and employed Andromeda for database search [25]. The MS/MS spectra were matched against the H37Rv proteome. Enzyme specificity was set to trypsin, and the search included cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification and methylation of lysine and arginine (+14.015650 Da) as variable modifications. Based on optimized parameters for PTM identification and localization [24], the search engine score was set to a minimum cutoff of 40 for the identification of methylated peptides. Additional annotations on low and high scoring peptides were performed by the ‘expert system’ for computer-assisted annotation of MS/MS spectra. Up to two missed cleavages were allowed for protease digestion, and peptides had to be fully tryptic. Downstream bioinformatics analysis was done in the Perseus software environment, which is part of MaxQuant. For MtrA mutants, we employed the matching between runs algorithm [26,27] in MaxQuant to alleviate the stochasticity of shotgun proteomics, which consists of transferring identifications of MS1 features between samples based on accurate mass and retention time values. Identification of lysine acetylation and succinylation was performed as described earlier [20].

In silico analysis

Gene names, protein names, protein subcellular localization, and molecular functions were extracted from Mycobrowser (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch/) and UniProt databases (http://www.uniprot.org/). Protein functional categories were obtained as described earlier by Lew et al. [28]. Gene essentiality data were procured from Mycobrowser and from previous studies documenting gene essentiality during in vitro growth, infection, or growth on cholesterol-containing media [29–32]. MtrA crystal structure was obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 2GWR) [33] and viewed using UCSF Chimera [34].

Putative promoter regions of Mtb sahH or Msm sahH were predicted using BPROM (http://softberry.com). Probable MtrA-binding sites were searched at these promoter regions using the LASAGNA online tool (https://biogrid-lasagna.engr.uconn.edu) [35].

In vitro kinase assay

In vitro kinase assay was performed by a protocol described earlier [36]. Briefly, E. coli purified His6-MtrA and mutants (5 μg each) were incubated with MBP-EnvZ kinase (2 μg) in the kinase buffer (50 mM Tris–Cl [pH 7.4], 50 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM DTT) and [γ−32P]ATP (BRIT, Hyderabad, India) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 2X Laemmli buffer and proteins were resolved on 12% SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography using Personal Molecular Imager (PMI, Bio-Rad).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

DNA region encompassing Mtb oriC (205 bp) [37], putative Mtb sahH promoter (sahHMt-Pr, 199 bp), or putative Msm sahH promoter (sahHMs-Pr, 201 bp) were PCR amplified, and purified products were end-labeled with [γ−32P]ATP using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (Roche) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Varying amounts of His6-MtrA and its site-specific mutants were phosphorylated using 2 mg MBP-tagged E. coli EnvZ in the kinase buffer and 1 mM ATP at 37°C for 30 min. Phosphorylated MtrA and MtrA mutants (10–100 μM) were incubated with the labeled DNA probes at 4°C for 30 min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, and 5% glycerol in a total volume of 20 μl. Reaction samples were resolved using 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X Tris/Borate/EDTA buffer. Gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography in Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed using the protocols described previously [38] with few modifications. Briefly, log phase Msm cells were lysed in TRIzol® (Invitrogen) by bead beating using 0.1 mm zirconium beads. RNA was precipitated using isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in nuclease-free water. Before performing cDNA synthesis, RNA was treated with DNase (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol to remove traces of genomic DNA. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using random primers according to the protocol provided by the supplier (Thermo Scientific), and then used for measuring the expression of mtrA or sahH with gene-specific primers. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Roche) as per previously described protocols [39]. The data obtained were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method and the relative fold change in expression was calculated. Msm housekeeping gene sigA (encoding Sigma factor A) or 16S rRNA, was used as a control. The primers were sequence-specific for each gene analyzed, with PCR products between 100 and 200 bp.

For studying the effect of Hcy on mtrA or sahH expression, Msm cells were grown in an increasing concentration of Hcy and gene expression was measured using qRT-PCR. For assessing the effect of SahH on mtrA expression, Msm cells containing pVV16 or pVV16-sahH were used.

Results

Multiple Mtb proteins are methylated on lysine and arginine residues

In Mtb, the proteins involved in metabolism, respiration, and cell wall-related processes form the majority of functional proteome compared with regulatory and signaling proteins (Supplementary Figure S1a) [28]. Moreover, in E. coli the proteins involved in regulation and signaling represent a low copy number group as compared with the proteins involved in translation, protein folding, and other constitutive functions [40]. Therefore, for our study, we chose 180 candidate protein-coding genes belonging to different functional classes (Supplementary Figure S1a,b and Supplementary Table S1) with a focus on less prevalent regulatory and signaling proteins. We selected very few genes from ‘PE and PPE proteins’ and ‘conserved hypotheticals’ and did not select any genes from the categories ‘Stable RNAs’, ‘Insertion sequences and phages’, and ‘Unknown’. These genes were cloned into mycobacterial expression vector pVV16 that contains a carboxy-terminal His6-tag and the constructs were electroporated into Msm, a non-pathogenic model organism that provides appropriate cellular milieu close to Mtb. We successfully purified 72 out of the 180 proteins under non-denaturing conditions, while others failed to express or purify. Purified proteins were probed with anti-methyllysine antibody to determine their methylation status where Histone protein served as a positive control. The identity of each purified protein was confirmed by re-probing the immunoblot membranes with an anti-His6 antibody. Apart from identifying the purified target proteins, the anti-His6 antibody also detected the presence of a consistent protein band corresponding to Msm chaperon protein GroEL, which is highly abundant and contains a C-terminal histidine-rich tail (MSMEG_1583) [41], and a few other contaminating proteins (Figure 1a). Among the 72 recombinant proteins, 10 proteins were recognized by the anti-methyllysine antibody, suggesting the presence of methylation on lysine residues (Figure 1a). However, we could not detect a distinct methylated band for PykA. To validate the protein identity and the methylation of the 10 Western blot-positive candidate proteins, we performed high-resolution mass spectrometry. We were successful in detecting 20 methyllysine sites belonging to 7 candidate proteins except LldD1, LldD2, and Tpi (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, we also detected 18 methylarginine sites in 7 candidate proteins, which included LldD2 and Tpi (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S2). Together, we identified 20 methylly-sine and 18 methylarginine sites in 9 out of 10 Western blot-positive proteins.

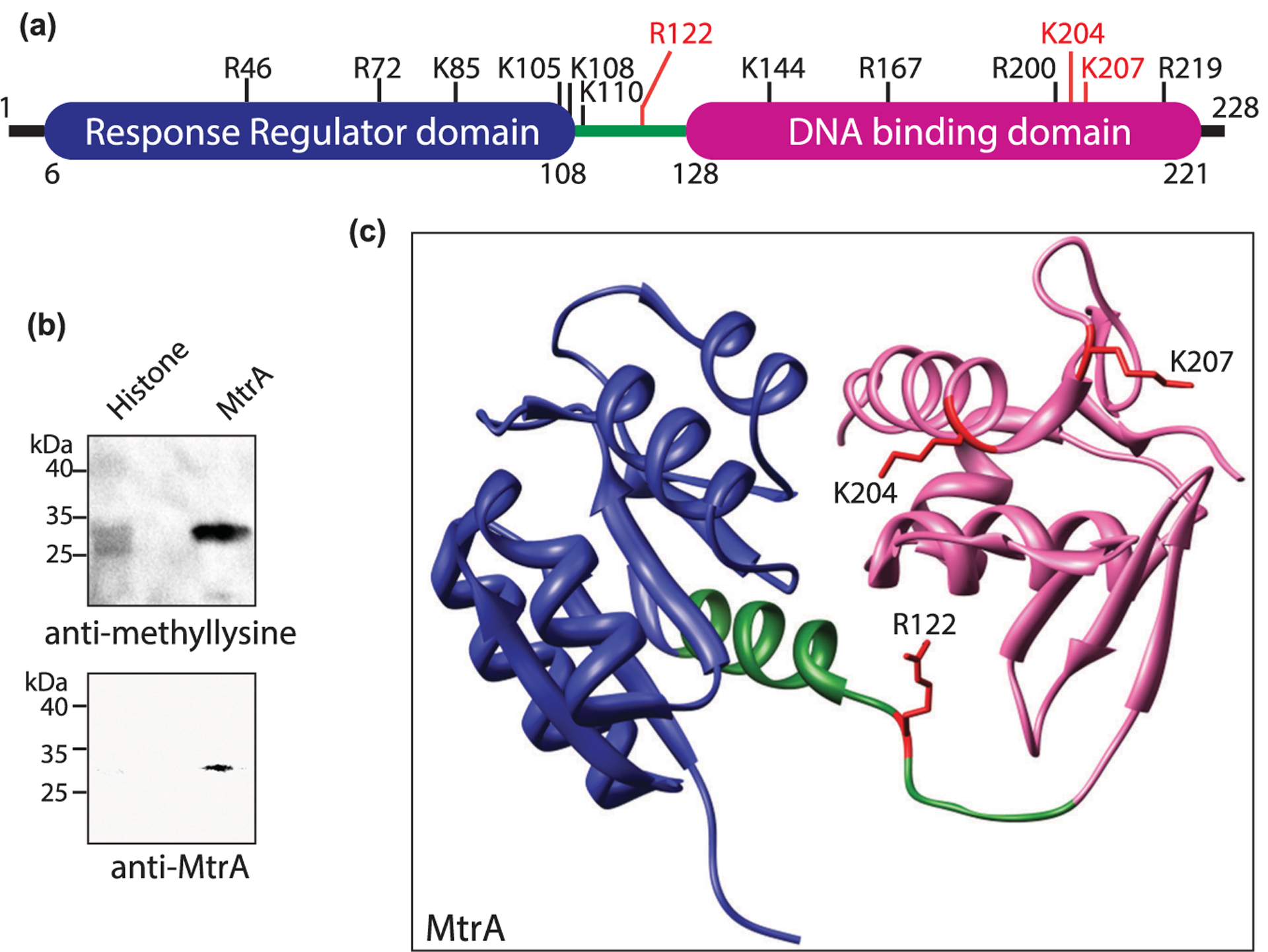

MtrA is methylated in Mtb

Subsequently, we set out to investigate the biological significance of methylation on lysine and arginine residues. Towards this, we chose MtrA as the candidate protein, which was methylated on both lysine and arginine residues. MtrB–MtrA is one among the 11 TCS systems present in Mtb where MtrB is the sensor histidine kinase and MtrA is the cognate response regulator. High throughput transposon mutagenesis experiments suggested mtrA to be an essential gene for in vitro growth of Mtb [29]. To determine if MtrA is methylated in Mtb, pVV16-mtrA expression construct was expressed in Mtb, and purified His6-tagged protein was probed with anti-MtrA and anti-methyllysine antibodies. Consistent with the results obtained in Msm (Figure 1a), MtrA was found to be methylated in Mtb (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. MtrA is methylated in Mtb.

(a) Pictorial representation of MtrA domain organization showing the location of different methylated sites. (b) His6-MtrA was overexpressed and purified from Mtb. Purified protein was probed with anti-methyllysine antibody (upper panel) and anti-MtrA (lower panel) antibody. Histone was used as a positive control. (c) Structural representation of MtrA (PDB ID: 2GWR). Response regulator domain (blue), linker region (green), and DNA binding domain (pink) are visible with the three crucial methylated sites marked red.

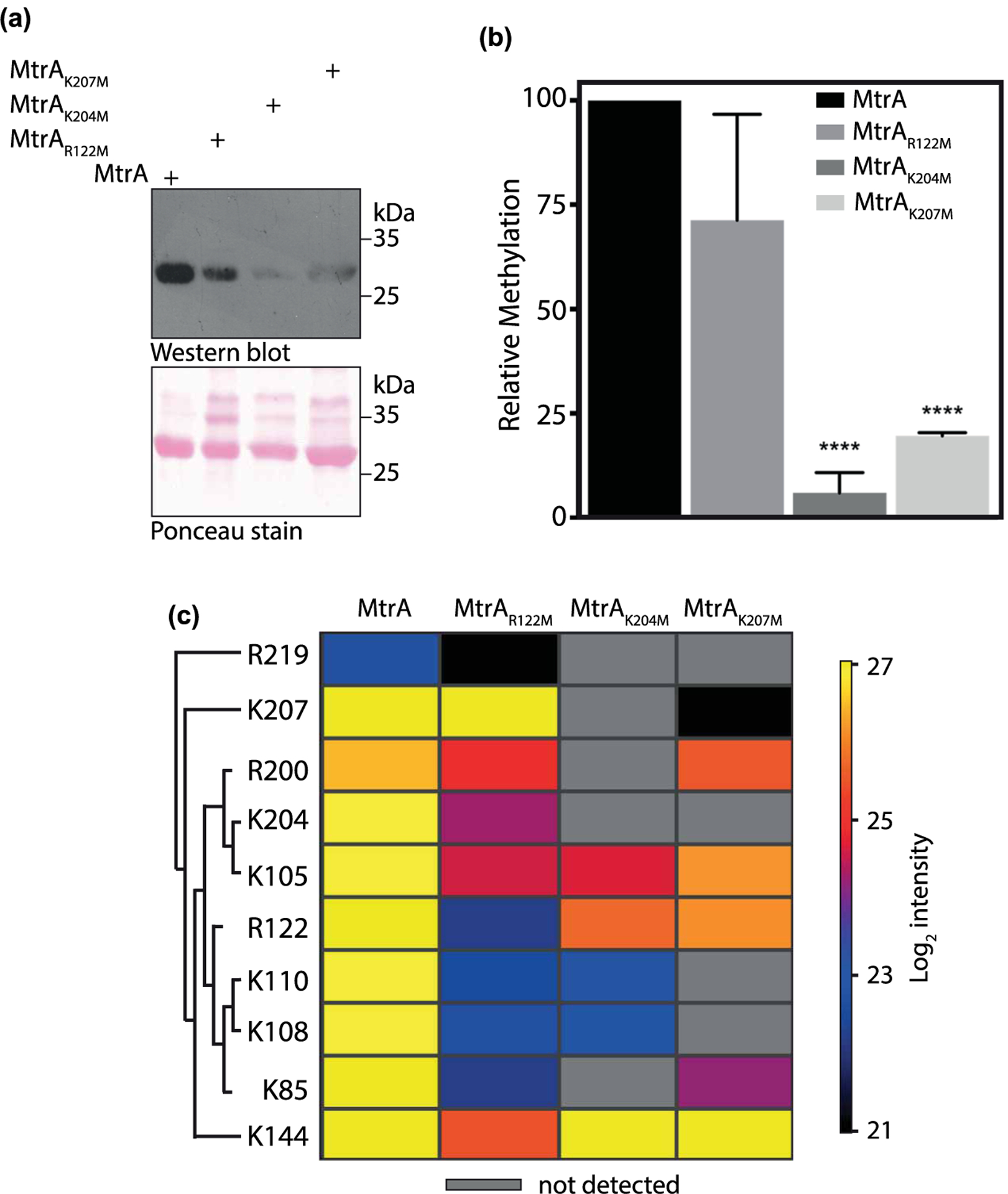

MtrA is a 228 amino acid (aa) long protein with a 102 aa long N-terminal response regulator domain and a 93 aa long C-terminal winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain homologous to E. coli OmpR (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure S3) [42,43]. Mass spectrometry data showed that MtrA was methylated on six arginine residues and seven lysine residues (Figure 1b). Analysis of these 13 methylated residues showed that R122 is a conserved residue present in the linker region, and K204 and K207 are adjacent to the DNA recognition helix (Figure 2c and Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, we examined the roles of R122, K204, and K207 by mutating them individually to methionine residues, the closest structural mimic to dimethyllysine [44]. Wild type and mutant MtrA proteins were expressed in Msm and the purified proteins were probed with anti-methyllysine antibody to compare their relative methylation (Figure 3a). Densitometric analysis of blots suggested that mutating R122, K204, or K207 individually resulted in decreased overall methylation levels, albeit the extent of reduction varied. While MtrAK204M and MtrAK207M had considerable decrease in the extent of methylation (95% and 80%, respectively; P-value < 0.0001), MtrAR122M mutant only lost marginal methylation (30%) (Figure 3b). The contribution of these three amino acid residues towards total MtrA methylation was further analyzed by a quantitative proteomics-based method to determine the extent of methylation at 10 sites in MtrA. A heat-map was generated representing the methylation intensities of identified peptides in MtrA, MtrAR122M, MtrAK204M, and MtrAK207M. The fold change of signal intensities at specific sites in MtrA mutants relative to that in MtrA are shown in Supplementary Table S3. The comparison shows that mutating any of these residues negatively affects the methylation at other sites; K204M or K207M completely abolish the methylation at four other sites (Figure 3c). We observed a background signal for amino acid position 207 in the MtrAK207M mutant, which was due to the ‘match between run’ event rather than a bonafide MS/MS signal. Moreover, the signal was only 0.4% compared with that in MtrA-WT signal, suggesting that it most likely represents the noise (Supplementary Table S3). Similarly, background signal was also observed for amino acid position 122 in MtrAR122M mutant, which may be due to noise but could not be attributed to ‘match between run’ event. Collectively, the data indicate that multiple methylated residues of MtrA act co-operatively and K204 and K207 are crucial for MtrA methylation.

Figure 3. MtrA is methylated at lysine and arginine residues.

(a) MtrA and its mutants were overexpressed and purified from Msm. Purified proteins were loaded on SDS–PAGE, transferred on nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-methyllysine antibody. Ponceau-stained membrane image is shown in the lower image. (b) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot shown in (a). The bar graph depicts intensities obtained after normalization with protein amounts detected by ponceau staining. The intensity of methylated MtrA was considered as 100% and relative methylation intensities of mutants are plotted. Data (mean ± s.d.) are from three individual replicates. **** P ≤ 0.0001, as determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. (c) Heat map showing the effect of mutation of R122, K204, and K207 residues on methylation intensities at other sites. Each row depicts the residue at which quantitative analysis was performed and each column represents the protein analyzed. Mass spectrometric intensities are color-coded according to the key given below the heat map (log2 scale).

Methylation of MtrA is critical for DNA binding

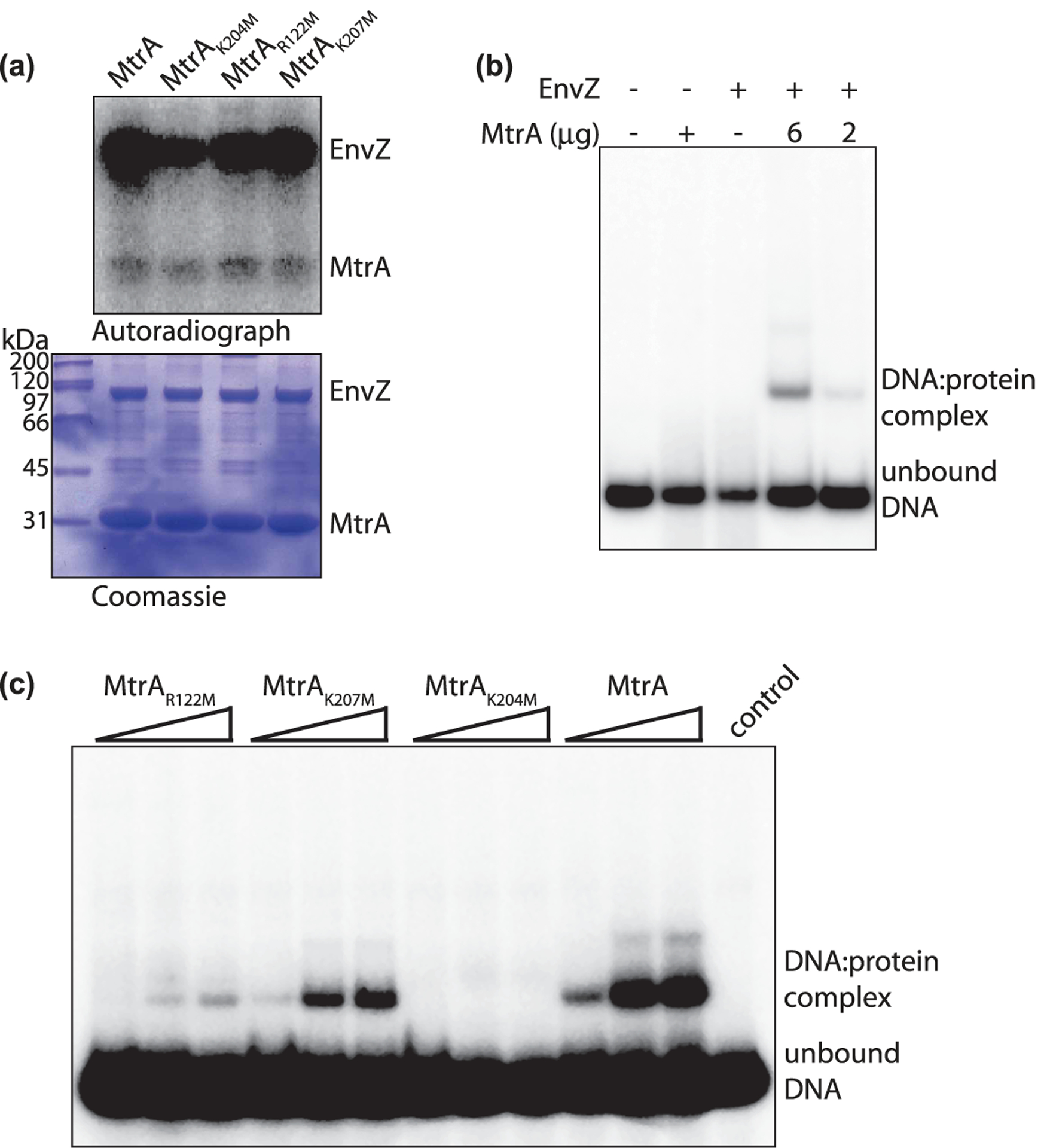

The binding of MtrA to DNA is contingent upon its phosphorylation on D56 residue by the sensor kinase MtrB [42]. Once phosphorylated, MtrA is known to regulate DNA replication by binding to the repeat nucleotide motifs at the origin of replication (oriC) [37]. To evaluate the role of methylation of MtrA on its DNA-binding ability, we chose the 205 bp long region of oriC as a probe to perform EMSA with purified MtrA and its methylation site mutants MtrAR122M, MtrAK204M, and MtrAK207M. To phosphorylate and activate MtrA, we utilized EnvZ, a homolog of MtrB in E. coli that has been used in several previous studies [36,37,45]. MtrA, MtrAR122M, MtrAK204M, or MtrAK207M proteins were incubated with EnvZ in the presence of [γ−32P]ATP and their phosphorylation status was analyzed by autoradiography. As anticipated, EnvZ was found to be autophosphorylated likely on the histidine residue (Figure 4a; upper band). In addition to the autophosphorylated EnvZ, we detected efficient phosphorylation of MtrA and its site-specific mutants (Figure 4a; lower band). Moreover, phosphorylation of MtrA was found to be similar for wild type and mutant proteins suggesting that EnvZ does not differentiate between these substrates (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Role of methylated residues in DNA-binding activity of MtrA.

(a) MtrA WT and mutants were expressed and purified from E. coli and equal amounts were phosphorylated by EnvZ in the presence of γ[32P]ATP. The reactions were resolved on SDS–PAGE, coomassie stained (lower panel), and autoradiographed (upper panel). (b) Radiolabelled Mtb oriC DNA probe was synthesized using γ[32P]ATP by PCR. DNA binding assay was performed in the presence of unphosphorylated (6 mg, lane 2) or phosphorylated MtrA (6 μg and 2 μg, lanes 4 and 5). As a control, reactions were performed in the absence of MtrA (lane 3) or without any protein (lane 1). The reactions were resolved on native PAGE and gels were autoradiographed. DNA: protein complex and the unbound DNA are shown. (c) Radiolabelled oriC probe was incubated in the presence of 0–100 μM phosphorylated MtrA, MtrAK204M, MtrAK207M, or MtrAR122M proteins. The reactions were resolved on native PAGE and gels were autoradiographed. DNA:protein complex and the unbound DNA are shown.

Next, we evaluated the DNA-binding activity of wild type MtrA with or without EnvZ incubation by EMSA using radiolabeled oriC fragment as the DNA probe. It is apparent from the data that there is no DNA: protein complex formation if either MtrA or EnvZ is absent (Figure 4b). We observed DNA binding only upon incubation of phosphorylated MtrA with radiolabeled oriC DNA fragment and the binding efficiency was dependent on the concentration of MtrA (Figure 4b). These results show that, EnvZ efficiently phosphorylates MtrA in vitro, and phosphorylated MtrA proficiently interacts with the DNA (Figure 4a,b).

Finally, we compared the DNA-binding activity of MtrA and MtrA mutants that were phosphorylated by EnvZ (Figure 4c). Equal amounts of phosphorylated MtrA, MtrAR122M, MtrAK204M, or MtrAK207M were incubated with oriC DNA probe and EMSA was performed. While we could detect DNA: protein complex with MtrA, and MtrAK207M proteins; mutants MtrAR122M and MtrAK204M showed marginal or no binding, respectively. Since lysine residues can be modified by other PTMs such as acetylation, we analyze whether MtrA was a target of any of these other modifications. We performed an additional mass spectrometric analysis to identify lysine modifications on His6-MtrAMtb expressed and purified from Msm. The mass spectrometric analysis showed the presence of acetylation and succinylation on MtrA and both modifications were found to be on K207 residue, but not on K204 residue, suggesting that the only modification detected on K204 is methylation (Supplementary Figure S4). Taken together this data suggest that the methylation of R122 and K204 plays an important role in modulating the interaction of MtrA with DNA.

Perturbation of metabolic intermediate levels influences MtrA methylation

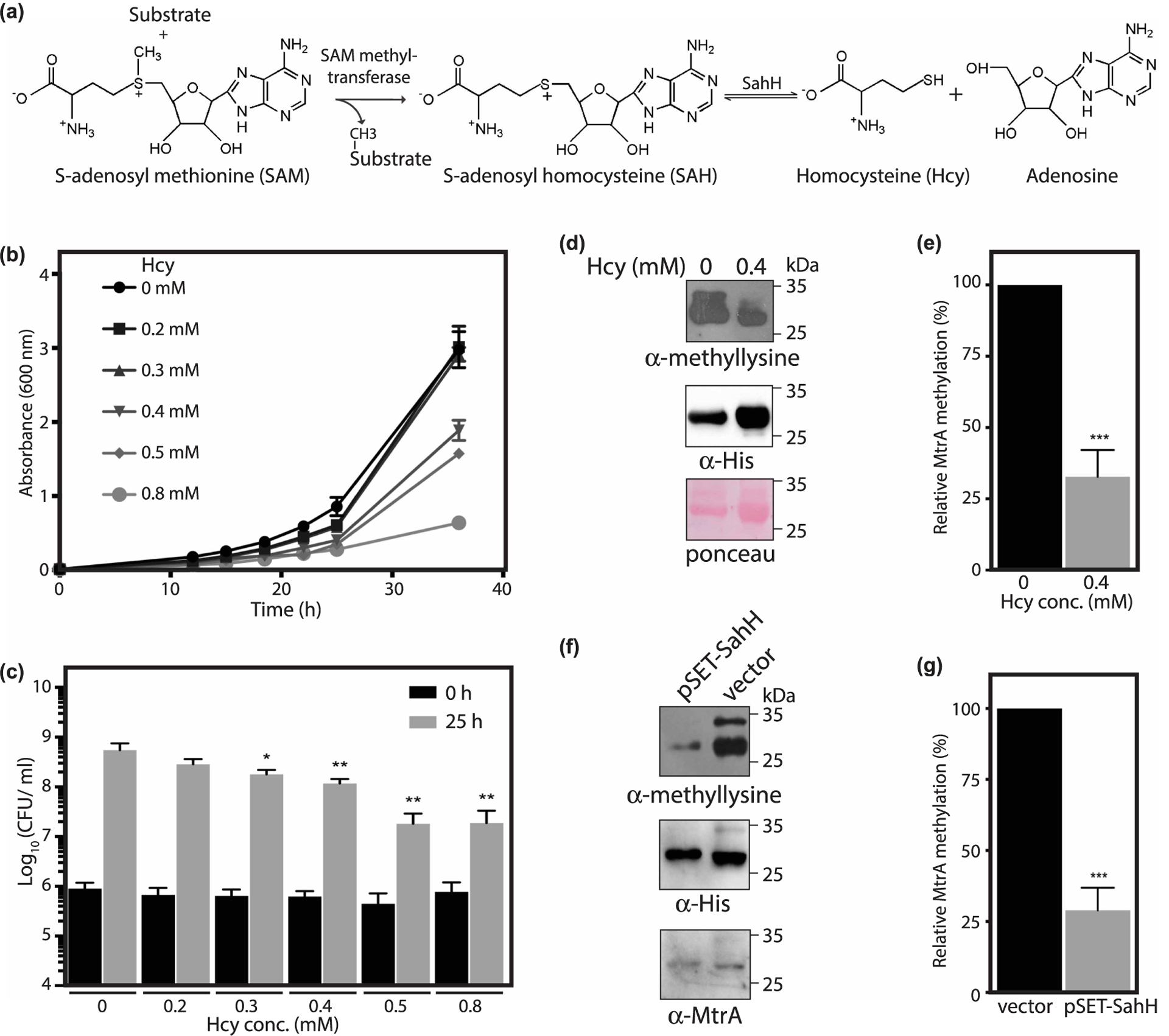

Next, we tried to identify mechanisms that regulate protein methylation. Methylation reactions are catalyzed by SAM-dependent methyltransferases where SAH and consequently Hcy are generated as by-products (Figure 5a). We have previously shown that perturbation of levels of Mtb SahH impacts metabolic levels of Hcy and may affect SAH, a potent inhibitor of methyltransferases [19]. Interestingly, Mtb sahH (encoding SahH), an essential gene, is present in the genomic vicinity of mtrA [29]. This led us to hypothesize that SahH-mediated perturbation in the levels of SAH or Hcy may impact methylation of proteins like MtrA.

Figure 5. The perturbation of metabolic intermediate levels influences MtrA methylation.

(a) Reaction showing the synthesis of Hcy from SAH catalyzed by SahH. (b,c) Msm cells were grown in the presence of 0–0.8 mM Hcy and growth was measured. Data (mean ± s.d.) are from four individual replicates. (b) A600 was plotted as a function of time. (c) Graph shows Log10(CFU/ml) calculated during the exponential growth phase as a function of Hcy concentration. (d, e) MtrA was expressed and purified from Msm using Ni2+-NTA chromatography in the absence or presence of 0.4 mM Hcy. (d) Immunoblotting was performed using anti-methyllysine antibody followed by an anti-His6 antibody. (e) Graph showing the relative methylation of MtrA in the presence of Hcy with respect to methylation of MtrA in the absence of Hcy. Methyllysine intensities were normalized to MtrA protein levels as measured by anti-His6 immunoblot. Data (mean ± s.d.) are from three individual replicates. (f,g) MtrA was expressed and purified from Msm strain that overexpressed SahH using Ni2+-NTA chromatography. (f) Immunoblotting was performed using anti-methyllysine antibody followed by anti-His6 and anti-MtrA antibodies. (g) Graph showing the methylation of MtrA in the presence of overexpressed SahH relative to the methylation of MtrA in the presence of vector control. Methyllysine intensities were normalized to MtrA protein levels as measured by anti-His6 immunoblot. Data (mean ± s.d.) are from three individual replicates. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, as determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

To test our hypothesis, we first evaluated the effect of increasing Hcy on the growth of Msm. Bacteria were grown in minimal growth medium containing varying concentrations of Hcy and their growth was measured. We found that increasing concentration of Hcy negatively affects bacterial growth in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5b,c). Results suggested that higher than 0.4 mM Hcy resulted in more than a log-fold decrease in Msm CFUs during the exponential growth phase. Therefore, we decided to use a sub-lethal concentration of 0.4 mM for further experiments. We analyzed methylation of MtrA purified from Msm grown in the presence or absence of 0.4 mM Hcy using immunoblotting. In line with our hypothesis, the addition of Hcy resulted in a ~70% decrease in methylation of MtrA (Figure 5d,e).

Next, we addressed the influence of overexpressing SahH on MtrA methylation. We analyzed methylation of MtrA purified from Msm containing an integrated copy of Mtb SahH. We observed that overexpression of SahH also resulted in a ~70% decrease in MtrA methylation levels, presumably because of perturbed SAH levels as SAH is a potent inhibitor of methyltransferases (Figure 5f,g). Collectively, the data suggest that perturbation of metabolic intermediates negatively modulates MtrA methylation.

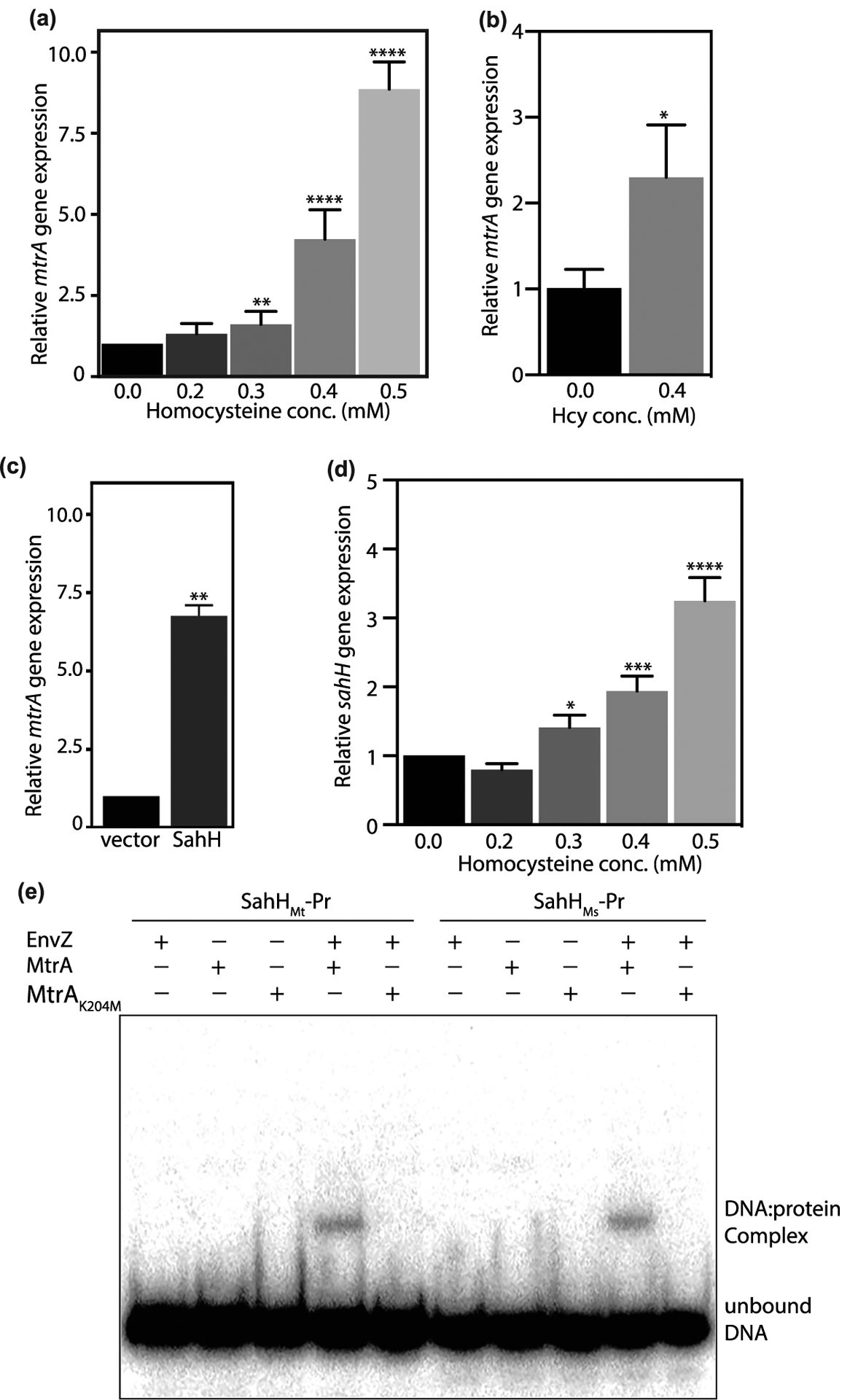

MtrA methylation negatively regulates transcriptional activation

In Figure 4, we showed that the methylation mimetic mutant of K204 (K204M) does not bind with the DNA. As a corollary, methylation of MtrA should negatively modulate MtrA-mediated transcriptional activation, whereas a decrease in the methylation should positively modulate transcriptional activation. Results in Figure 5 showed that the addition of Hcy or overexpression of SahH results in decreased methylation of MtrA. Taken together, we theorized that the addition of Hcy or overexpression of SahH would increase the transcriptional activation by MtrA. MtrA is known to bind to its own promoter and regulates its expression [37]. Thus, we monitored the expression level of mtrA in the presence of an increasing concentration of Hcy. Msm cells were grown in minimal medium supplemented with increasing concentration of Hcy and mtrA expression was measured using qRT-PCR. In line with our hypothesis, we observed increased transcription of mtrA with an increasing concentration of Hcy (Figure 6a). In these qRT-PCR reactions, the expression was normalized with respect to the expression of sigA. To reconfirm these results, we performed a new set of qRT-PCR reactions in the presence of 0.4 mM Hcy, except that the expression of mtrA was normalized with respect to the expression of 16S rRNA (Figure 6b). The results were in agreement with the data presented in Figure 6a, confirming that the addition of Hcy increases the expression of mtrA. Next, we examined the expression levels of mtrA upon expression of SahH by utilizing Msm harboring pVV16-sahH plasmid (Figure 6c). We observed a ~6-fold increase in the transcript levels of mtrA in the presence of overexpressed SahH.

Figure 6. MtrA methylation negatively regulates transcriptional activation.

(a–c) mtrA expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR in Msm cultures grown in the presence of Hcy (a,b) or SahH overexpression (c). Expression level of mtrA was analyzed with respect to sigA (a,c) or 16S rRNA (b). (d) sahH expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR in Msm cultures grown in the presence of Hcy with respect to sigA. Data (mean ± s.d.) are from six (a) or three (b,c, and d) biological triplicates. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, **** P ≤ 0.0001 as determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (compared with control values). (e) DNA binding assay was performed using putative sahH promoter fragments from Mtb (sahHMt-Pr) or Msm (sahHMs-Pr). MtrA and MtrAK204M were used in unphosphorylated or phosphorylated forms. The reactions were resolved on native PAGE and gels were autoradiographed. DNA:protein complex and the unbound DNA are shown.

Subsequently, we asked if the addition of Hcy impacts the expression of sahH and if so, does MtrA binds to the promoter region of sahH. To address this question, we evaluated the expression of Msm sahH in the presence of an increasing concentration of Hcy (Figure 6d). The results showed a direct correlation between Hcy concentration and expression of sahHMs. Besides mtrA promoter regions, we identified MtrA-binding sites in the putative sahH promoter region. Thus to examine if MtrA binds to putative sahHMs (sahHMs-Pr) and sahHMt (sahHMt-Pr) promoter regions, we performed EMSA with radiolabeled sahH promoter regions from Msm and Mtb, respectively. While only EnvZ or unphosphorylated MtrA does not bind with the DNA, we observed robust binding of phosphorylated MtrA with both sahHMs-Pr and sahHMt-Pr DNA fragments (Figure 6e). Most importantly, MtrAK204M mutant that showed abrogated binding with oriC fragment in the previous EMSA experiments (Figure 4c) failed to bind with both sahHMs-Pr and sahHMt-Pr DNA fragments, confirming that methylation of MtrA negatively modulates DNA binding and hence its activity both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

Covalent modification of side chains of multiple amino acids in proteins regulates their activity and function thus controlling cellular processes [46]. In addition to phosphorylation, which has been extensively investigated, multiple additional modifications have been identified with the help of high throughput mass spectrometry or by candidate-specific approaches. In this report, we used a candidate approach to identify proteins that are methylated on lysine residue, and the methylation of the positive candidates was validated by mass spectrometry. Most of the candidate proteins that were chosen for the study belonged to the regulatory protein class (Supplementary Figure S1a,b), followed by intermediary metabolism, and cell wall and cell processes. While a high throughput mass spectrometry approach may have provided a more comprehensive list of methylated proteins, with our approach we detected methylation of proteins in the functional categories that are relatively less prevalent. We have used a similar candidate approach previously to identify novel acylated proteins in Mtb [20]. In an independent study, Western blot analysis of MtHU (HupB) expressed and purified from Msm revealed the presence of acetylation, and the target sites were subsequently identified by mass spectrometry [47]. We identified a total of 10 proteins by Western blot and the mass spectrometry analysis showed nine of them to be methylated on lysine/arginine residues. Identification of 10 Western blot positive methylated proteins among the 72 candidates suggest that methylation could be a more frequent modification in mycobacterial proteins and warrant future large-scale analyses of the whole proteome. We propose that the present study be used in parallel with global proteomics-based approaches in order to have an unbiased analysis of both over-and under-represented protein functional categories in the whole proteome.

Analysis of Mtb genome suggests the presence of 57 probable methyltransferases- 29 of them may be involved in intermediary metabolism and respiration, 12 of them are probable lipid methyltransferases, 8 could be involved in RNA methylation, and 7 in DNA methylation (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch/). To date, only three methyltransferases-Rv1988, Rv2966c, and MamA- have been functionally characterized. Rv1988 is a secretory methyltransferase that enters the host nucleus and methylates histone H3 at arginine residues and regulates the expression of genes involved in combating reactive oxygen species [48]. Rv2966c is also a secretory methyltransferase that localizes to the host nucleus and methylates host DNA at cytosine residues [49]. MamA is a DNA N6-adenine methyltransferase that regulates the expression of multiple genes that provide fitness during hypoxia [50]. Methylation of Mtb HBHA and HupB by unknown methyltransferase(s) renders them proteolytic resistant [18]. Recently, a host methyltransferase is shown to methylate Mtb HupB to confer protection against invading bacilli [51]. Thus far, lysine/arginine methyltransferases that can act on the bacterial protein targets have not been characterized in mycobacteria. Identification of lysine/arginine methylation of many essential Mtb proteins indicate that mycobacterial methyltransferases might play important role in the pathogenesis and physiology of mycobacteria. Elucidating the specificities and mode of substrate recognition of methyltransferases would help in understanding the biological significance of protein methylation.

To elucidate the functional relevance of methylation in mycobacteria, we chose MtrA, an essential response regulator of TCS MtrB–MtrA in Mtb. MtrB is a non-essential membrane-bound sensor kinase that transfers a phosphate group to a conserved aspartate residue (D56) in MtrA. MtrA binds to the promoters of ripA (encoding peptidoglycan hydrolase), fbpA (encoding secreted antigen 85B), fbpB (encoding cell wall mycolyl hydrolase), dnaA (encoding replication initiator protein) and oriC (origin of replication) and regulates cell cycle progression [37,52]. Although phosphorylation at D56 is the primary regulatory mechanism for MtrA, the protein has also been reported to be pupylated at K207 [53] and acetylated at K110 [54]. We now show that MtrA is modified by lysine/arginine methylation, lysine acetylation, and lysine succinylation. Different lysine modifications occurring on MtrA might play a role in regulating different aspects of MtrA, such as methylation-mediated regulation of DNA-binding activity and pupylation-mediated regulation of protein turnover rate. Methylation of MtrA on arginine and lysine residues was found to negatively regulate its DNA-binding function (Figure 4). Arginine methylation regulates several mammalian processes associated with gene expression but is largely unrecognized in bacteria [8]. Proteomics analysis has revealed >25 arginine methylated proteins in Leptospira interrogans, but no functional role has been assigned to their methylation [55]. In most of these proteins, lysine methylation occurs in conjunction with arginine methylation on the same protein as is the case with mycobacterial MtrA. On the contrary, all the arginine methylated proteins of Desulfovibrio vulgaris do not contain methyllysine [56]. Although a dimethylarginine was spotted on a D. vulgaris transcriptional response regulator DVUA0086, its functional role remained obscure. Further revelation of the role of arginine methylation in bacteria is, therefore, essential.

Methyltransferase reactions are dependent on the presence of balanced amounts of SAM and SAH as they are prone to SAH-mediated inhibition. Under normal conditions, SAH levels are regulated using SahH-mediated reversible hydrolysis of SAH to Hcy. Hcy supplementation may allow the net flux of this reversible reaction towards SAH synthesis, which can negatively regulate methyltransferases activity. In a similar vein, overexpression of SahH may lead to depletion of SAH, which in turn leads to lower levels of SAM, a substrate for methyltransferases, thus influencing the activity. In agreement with this hypothesis, we observed that the addition of Hcy or overexpression of SahH led to decreased methylation of MtrA (Figure 5). DNA-binding experiment suggests that methylation negatively regulates MtrA interaction with DNA (Figure 4) and overexpression of SahH or addition of Hcy decreases MtrA methylation. In accordance, SahH or Hcy were found to increase mtrA transcription which may lead to altered expression of genes targeted by MtrA such as ripA, fbpB, and dnaA and regulate cell cycle progression. It is to be noted that SahH has previously been found to be associated with differential DNA and RNA methylation in eukaryotes [57–59], thus pointing towards a more general implication of SahH in regulating one-carbon metabolism. In mycobacteria, one-carbon metabolism pathway involving SAM and methionine biosynthesis has been proposed as a powerful target for anti-mycobacterial agents [60]. Mycobacterial strains deficient in SAM and methionine biosynthesis were found to be remarkably vulnerable in host tissues. Interestingly, such metabolic perturbation was shown to be associated with altered methylation at DNA and other important metabolites like biotin. In another study, disruption of one-carbon metabolism by antifolate molecules led to the efficient killing of Mtb [61]. These studies suggest the significance of studying regulators of one-carbon metabolism and highlight SahH as a promising drug target.

In summary, the present study provides a framework for elucidation of protein methylation in mycobacteria. We report the addition of protein arginine methylation to the growing list of regulatory PTMs in mycobacteria and suggest that methylation of MtrA at lysine and arginine residues regulates its activity. This study provides an orchestration of methylation and TCS signaling and therefore illuminates the critical role of methylation in bacterial physiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from Prof. Matthias Mann (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Germany) for the mass spectrometry for the identification of methylated peptides. The authors thank Christian Hentschker and Döerte Becher (University of Greifswald, Germany) for their help in identifying protein acetylation and succinylation by mass spectrometry.

Funding

This work was supported by the CSIR BSC-0123, BSC-0104, and J.C. Bose fellowship to Y.S.; CSIR research associate fellowship to A.Si.; and CSIR senior research fellowship to R.V. S.N. is funded through a CSIR-Senior research fellowship.

Abbreviations

- CFUs

colony-forming units

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- HBHA

heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin

- Hcy

homocysteine

- HupB

histone-like protein

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- SAH

S-adenosyl homocysteine

- SahH

S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- TCS

two-component system

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

CRediT Contribution

Yogendra Singh: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing — original draft, Project administration, Writing — review and editing. Anshika Singhal: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing — original draft, Writing — review and editing. Richa Virmani: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing — original draft, Writing — review and editing. Saba Naz: Investigation, Methodology, Writing — review and editing. Gunjan Arora: Conceptualization, Formal analysis. Mohita Gaur: Investigation, Methodology. Parijat Kundu: Methodology. Andaleeb Sajid: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing — review and editing. Richa Misra: Methodology. Ankita Dabla: Methodology. Suresh Kumar: Methodology. Jacob Nellissery: Resources, Formal analysis. Virginie Molle: Resources, Formal analysis, Methodology. Ulf Gerth: Resources, Methodology. Anand Swaroop: Resources, Formal analysis. Kirti Sharma: Resources, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing — review and editing. Vinay Kumar Nandicoori: Resources, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing — original draft, Writing — review and editing.

Data availability

Original mass spectrometry spectra are submitted in Supplementary Figure S2. All the reagents utilized in the manuscript would be available upon request.

References

- 1.WHO (2019) World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis report.

- 2.van Els CA, Corbiere V, Smits K, van Gaans-van den Brink JA, Poelen MC, Mascart F et al. (2014) Toward understanding the essence of post-translational modifications for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunoproteome. Front. Immunol 5, 361 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canova MJ and Molle V (2014) Bacterial serine/threonine protein kinases in host-pathogen interactions. J. Biol. Chem 289, 9473–9479 10.1074/jbc.R113.529917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Festa RA, McAllister F, Pearce MJ, Mintseris J, Burns KE, Gygi SP et al. (2010) Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [corrected]. PLoS One 5, e8589 10.1371/journal.pone.0008589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee KY, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P and Nathan CF (2005) S-nitroso proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: enzymes of intermediary metabolism and antioxidant defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 467–472 10.1073/pnas.0406133102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sajid A, Arora G, Singhal A, Kalia VC and Singh Y (2015) Protein phosphatases of pathogenic bacteria: role in physiology and virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 69, 527–547 10.1146/annurev-micro-020415-111342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schubert HL, Blumenthal RM and Cheng X (2003) Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem. Sci 28, 329–335 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedford MT and Clarke SG (2009) Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 33, 1–13 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanouette S, Mongeon V, Figeys D and Couture JF (2014) The functional diversity of protein lysine methylation. Mol. Syst. Biol 10, 724 10.1002/msb.134974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cain JA, Solis N and Cordwell SJ (2014) Beyond gene expression: the impact of protein post-translational modifications in bacteria. J. Proteom 97, 265–286 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salah Ud-Din AIM and Roujeinikova A (2017) Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins: a core sensing element in prokaryotes and archaea. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 74, 3293–3303 10.1007/s00018-017-2514-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greer EL and Shi Y (2012) Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet 13, 343–357 10.1038/nrg3173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedford MT (2007) Arginine methylation at a glance. J. Cell Sci 120, 4243–4246 10.1242/jcs.019885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Wen H and Shi X (2012) Lysine methylation: beyond histones. Acta Biochim. Biophys Sin. (Shanghai) 44, 14–27 10.1093/abbs/gmr100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbier M, Owings JP, Martinez-Ramos I, Damron FH, Gomila R, Blazquez J et al. (2013) Lysine trimethylation of EF-Tu mimics platelet-activating factor to initiate Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. MBio 4, e00207–e00213 10.1128/mBio.00207-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Xu JY, Hu H, Ye BC and Tan M (2018) Systematic proteomic analysis of protein methylation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes revealed distinct substrate specificity. Proteomics 18, 1700300 10.1002/pmic.201700300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pethe K, Alonso S, Biet F, Delogu G, Brennan MJ, Locht C et al. (2001) The heparin-binding haemagglutinin of M. tuberculosis is required for extrapulmonary dissemination. Nature 412, 190–194 10.1038/35084083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pethe K, Bifani P, Drobecq H, Sergheraert C, Debrie AS, Locht C et al. (2002) Mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin and laminin-binding protein share antigenic methyllysines that confer resistance to proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 99, 10759–10764 10.1073/pnas.162246899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singhal A, Arora G, Sajid A, Maji A, Bhat A, Virmani R et al. (2013) Regulation of homocysteine metabolism by Mycobacterium tuberculosis S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Sci. Rep 3, 2264 10.1038/srep02264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singhal A, Arora G, Virmani R, Kundu P, Khanna T, Sajid A et al. (2015) Systematic analysis of mycobacterial acylation reveals first example of acylation-mediated regulation of enzyme activity of a bacterial phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem 290, 26218–26234 10.1074/jbc.M115.687269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santhosh RS, Pandian SK, Lini N, Shabaana AK, Nagavardhini A and Dharmalingam K (2005) Cloning of mce1 locus of Mycobacterium leprae in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155 SMR5 and evaluation of expression of mce1 genes in M. smegmatis and M. leprae. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol 45, 291–302 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sajid A, Arora G, Gupta M, Singhal A, Chakraborty K, Nandicoori VK et al. (2011) Interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis elongation factor Tu with GTP is regulated by phosphorylation. J. Bacteriol 193, 5347–5358 10.1128/JB.05469-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS and Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma K, D’Souza RC, Tyanova S, Schaab C, Wisniewski JR, Cox J et al. (2014) Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 8, 1583–1594 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV and Mann M (2011) Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res 10, 1794–1805 10.1021/pr101065j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinitcyn P, Rudolph JD and Cox J (2018) Computational methods for understanding mass spectrometry–based shotgun proteomics data. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci 1, 207–234 10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-080917-013516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox J, Matic I, Hilger M, Nagaraj N, Selbach M, Olsen JV et al. (2009) A practical guide to the MaxQuant computational platform for SILAC-based quantitative proteomics. Nat. Protoc 4, 698–705 10.1038/nprot.2009.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jones LM and Cole ST (2011) Tuberculist–10 years after. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 91, 1–7 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeJesus MA, Gerrick ER, Xu W, Park SW, Long JE, Boutte CC et al. (2017) Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. MBio 8, e02133–16 10.1128/mBio.02133-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH and Rubin EJ (2003) Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol 48, 77–84 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin JE, Gawronski JD, Dejesus MA, Ioerger TR, Akerley BJ and Sassetti CM (2011) High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002251 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sassetti CM and Rubin EJ (2003) Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 100, 12989–12994 10.1073/pnas.2134250100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedland N, Mack TR, Yu M, Hung LW, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS et al. (2007) Domain orientation in the inactive response regulator Mycobacterium tuberculosis MtrA provides a barrier to activation. Biochemistry 46, 6733–6743 10.1021/bi602546q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC et al. (2004) UCSF chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C and Huang CH (2013) LASAGNA-search: an integrated web tool for transcription factor binding site search and visualization. Biotechniques 54, 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fol M, Chauhan A, Nair NK, Maloney E, Moomey M, Jagannath C et al. (2006) Modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proliferation by MtrA, an essential two-component response regulator. Mol. Microbiol 60, 643–657 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopalan M, Dziedzic R, Al Zayer M, Stankowska D, Ouimet MC, Bastedo DP et al. (2010) Mycobacterium tuberculosis origin of replication and the promoter for immunodominant secreted antigen 85B are the targets of MtrA, the essential response regulator. J. Biol. Chem 285, 15816–15827 10.1074/jbc.M109.040097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta M, Sajid A, Sharma K, Ghosh S, Arora G, Singh R et al. (2014) Hupb, a nucleoid-associated protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is modified by serine/threonine protein kinases in vivo. J. Bacteriol 196, 2646–2657 10.1128/JB.01625-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arora G, Sajid A, Arulanandh MD, Singhal A, Mattoo AR, Pomerantsev AP et al. (2012) Unveiling the novel dual specificity protein kinases in Bacillus anthracis: identification of the first prokaryotic dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase (DYRK)-like kinase. J. Biol. Chem 287, 26749–26763 10.1074/jbc.M112.351304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishihama Y, Schmidt T, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Hartl FU, Kerner MJ et al. (2008) Protein abundance profiling of the Escherichia coli cytosol. BMC Genom. 9, 102 10.1186/1471-2164-9-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ojha A, Anand M, Bhatt A, Kremer L, Jacobs WR Jr and Hatfull GF (2005) GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell 123, 861–873 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Zeng J and He ZG (2010) Characterization of a functional C-terminus of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis MtrA responsible for both DNA binding and interaction with its two-component partner protein, MtrB. J. Biochem 148, 549–556 10.1093/jb/mvq082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Hackert E and Stock AM (1997) Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol 269, 301–312 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyland EM, Molina H, Poorey K, Jie C, Xie Z, Dai J et al. (2011) An evolutionarily ‘young’ lysine residue in histone H3 attenuates transcriptional output in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 25, 1306–1319 10.1101/gad.2050311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plocinska R, Purushotham G, Sarva K, Vadrevu IS, Pandeeti EV, Arora N et al. (2012) Septal localization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis MtrB sensor kinase promotes MtrA regulon expression. J. Biol. Chem 287, 23887–23899 10.1074/jbc.M112.346544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pejaver V, Hsu WL, Xin F, Dunker AK, Uversky VN and Radivojac P (2014) The structural and functional signatures of proteins that undergo multiple events of post-translational modification. Protein Sci. 23, 1077–1093 10.1002/pro.2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosh S, Padmanabhan B, Anand C and Nagaraja V (2016) Lysine acetylation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis HU protein modulates its DNA binding and genome organization. Mol. Microbiol 100, 577–588 10.1111/mmi.13339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yaseen I, Kaur P, Nandicoori VK and Khosla S (2015) Mycobacteria modulate host epigenetic machinery by Rv1988 methylation of a non-tail arginine of histone H3. Nat. Commun 6, 8922 10.1038/ncomms9922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma G, Upadhyay S, Srilalitha M, Nandicoori VK and Khosla S (2015) The interaction of mycobacterial protein Rv2966c with host chromatin is mediated through non-CpG methylation and histone H3/H4 binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3922–3937 10.1093/nar/gkv261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shell SS, Prestwich EG Baek SH, Shah RR, Sassetti CM, Dedon PC et al. (2013) DNA methylation impacts gene expression and ensures hypoxic survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003419 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yaseen I, Choudhury M, Sritharan M and Khosla S (2018) Histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 participates in host defense by methylating mycobacterial histone-like protein HupB. EMBO J. 37, 183–200 10.15252/embj.201796918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purushotham G, Sarva KB, Blaszczyk E, Rajagopalan M and Madiraju MV (2015) Mycobacterium tuberculosis oriC sequestration by MtrA response regulator. Mol Microbiol. 98, 586–604 10.1111/mmi.13144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witze ES, Old WM, Resing KA and Ahn NG (2007) Mapping protein post-translational modifications with mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 798–806 10.1038/nmeth1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh KK, Bhardwaj N, Sankhe GD, Udaykumar N, Singh R, Malhotra V et al. (2019) Acetylation of response regulator proteins, TcrX and MtrA in M. tuberculosis tunes their phosphotransfer ability and modulates two-component signaling crosstalk. J. Mol. Biol 431, 777–793 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao XJ, Dai J, Xu H, Nie S, Chang X, Hu BY et al. (2010) High-coverage proteome analysis reveals the first insight of protein modification systems in the pathogenic spirochete Leptospira interrogans. Cell Res. 20, 197–210 10.1038/cr.2009.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaucher SP, Redding AM, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD and Singh AK (2008) Post-translational modifications of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough sulfate reduction pathway proteins. J. Proteome Res 7, 2320–2331 10.1021/pr700772s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baric I, Fumic K, Glenn B, Cuk M, Schulze A, Finkelstein JD et al. (2004) S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency in a human: a genetic disorder of methionine metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 4234–4239 10.1073/pnas.0400658101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mull L, Ebbs ML and Bender J (2006) A histone methylation-dependent DNA methylation pathway is uniquely impaired by deficiency in Arabidopsis S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Genetics 174, 1161–1171 10.1534/genetics.106.063974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radomski N, Kaufmann C and Dreyer C (1999) Nuclear accumulation of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase in transcriptionally active cells during development of Xenopus laevis. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4283–4298 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berney M, Berney-Meyer L, Wong KW, Chen B, Chen M, Kim J et al. (2015) Essential roles of methionine and S-adenosylmethionine in the autarkic lifestyle of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, 10008–10013 10.1073/pnas.1513033112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nixon MR, Saionz KW, Koo MS, Szymonifka MJ, Jung H, Roberts JP et al. (2014) Folate pathway disruption leads to critical disruption of methionine derivatives in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol 21, 819–830 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Original mass spectrometry spectra are submitted in Supplementary Figure S2. All the reagents utilized in the manuscript would be available upon request.