Abstract

Introduction:

Bowel cancer is a significant global health concern, ranking as the third most prevalent cancer worldwide. Laparoscopic resections have become a standard treatment modality for resectable colorectal cancer. This study aimed to compare the clinical and oncological outcomes of medial to lateral (ML) vs lateral to medial (LM) approaches in laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at a UK district general hospital from 2015 to 2019, including 402 patients meeting specific criteria. Demographic, clinical, operative, postoperative, and oncological data were collected. Participants were categorised into LM and ML groups. The primary outcome was 30-day complications, and secondary outcomes included operative duration, length of stay, lymph node harvest, and 3-year survival.

Results:

A total of 402 patients (55.7% males) were included: 102 (51.6% females) in the lateral mobilisation (LM) group and 280 (58.9% males) in the medial mobilisation (ML) group. Right hemicolectomy (n=157, 39.1%) and anterior resection (n=150, 37.3%) were the most performed procedures. The LM group had a shorter operative time for right hemicolectomy (median 165 vs. 225 min, P<0.001) and anterior resection (median 230 vs. 300 min, P<0.001). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of wound infection (P=0.443), anastomotic leak (P=0.981), postoperative ileus (P=0.596), length of stay (P=0.446), lymph node yield (P=0.848) or 3-year overall survival rate (Log-rank 0.759).

Discussion:

The study contributes to the limited evidence on ML vs LM approaches. A shorter operative time in the LM group was noted in this study, contrary to some literature. Postoperative outcomes were comparable, with a non-significant increase in postoperative ileus in the LM group. The study emphasises the safety and feasibility of both approaches.

Keywords: approach, cancer, colorectal, surgery

Introduction

Highlights

A lateral to medial operative approach is strongly associated with shorter operative times for right hemicolectomy and anterior resection procedures.

No difference is shown between these two approaches in terms of wound infection, anastomotic leak, postoperative ileus, length of stay, lymph node yield, or 3-year overall survival rate.

The study emphasises the safety and feasibility of both approaches.

Bowel cancer stands as the third most prevalent global cancer and ranks fourth in the United Kingdom (UK), representing the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality. Annually, around 43 000 individuals in the UK receive a bowel cancer diagnosis, constituting 11% of total cancer cases1. The adoption of laparoscopic colorectal resections has become widespread, offering outcomes comparable to open procedures2. Endorsement from both the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)3 and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS)4 solidifies laparoscopic surgery as the preferred approach for colorectal cancer resections.

The core principle guiding oncological resection in bowel cancer focuses on tumour removal with sufficient margins and the retrieval of lymph nodes in the mesentery along the draining blood vessels. Despite randomized trials not demonstrating a superior lymph node harvest with laparoscopic surgery compared to open techniques2,5, ACPGBI advocates for quality mesocolic excision to improve oncological outcomes in colon cancer resections. This discrepancy in outcomes has raised questions about the efficacy of various laparoscopic techniques. Historically, the lateral to medial approach prevailed during the era of open surgery. However, with technological advancements and the advent of laparoscopic surgery, the medial to lateral approach gained prominence and is practised widely.

The medial to lateral approach involves the exploration, identification, and proximal division of mesenteric vessels, followed by the division of lateral peritoneal attachments. In contrast, the lateral to medial approach follows the sequence employed in open procedures, involving the division of lateral peritoneal attachments before exploring the medial mesentery and performing the proximal division of the identified blood vessels6. In 2004, the European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons (EAES) consensus statement recommended that the medial to lateral approach is the preferred choice for mesocolic dissection7.

This study aims to compare the clinical and oncological outcomes of the medial to lateral (ML) versus lateral to medial (LM) approach in laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at a district general hospital in the United Kingdom. The study encompassed consecutive patients meeting specific inclusion and exclusion criteria over a 5-year period from January 2015 to December 2019.

Inclusion criteria comprised patients aged 18 years or older, of any sex, with a diagnosis of colorectal and anal cancer undergoing elective laparoscopic cancer resection with curative intent. Laparoscopic to open conversion was included only if mesenteric or colonic mobilisation was completed laparoscopically. All patients included had preoperative discussion in the colorectal Multi-Disciplinary Meeting (MDT). Exclusion criteria encompassed patients under 18 years, elective open colorectal cancer resections, laparoscopic to open conversion without laparoscopic mobilisation, emergency colorectal cancer resections, patients undergoing palliative procedures and patients with previous colonic stenting. All surgeries were performed by experienced colorectal surgeons with at least a consultant surgeon present throughout the operation. Complete mesocolic excisions were not performed in any of the cases in our study population.

Patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer were identified from a prospectively maintained local cancer office database. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a finalised patient list was developed. A password-encrypted data collection sheet was created, detailing demographic, clinical, and oncological variables. The local hospital cancer database and electronic medical records were accessed to collect data. Demographic data included age at presentation, gender, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) grade, Body Mass Index (BMI), and co-morbidities (Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Asthma, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Atrial fibrillation, and Heart failure).

Clinical data were divided into preoperative, operative, and postoperative sets. Preoperative data included presenting symptoms and tumour location. The tumour location was based on preoperative imaging (CT scan or MRI), and MDT discussions confirmed curative resection intent. Operative data were reviewed from individual operation notes and theatre electronic records, documenting the operation name, mode (laparoscopic, laparoscopic converted to open), and method of mobilisation (medial to lateral, lateral to medial). For converted procedures, the laparoscopic completion of mobilisation was assessed. Postoperative data included length of stay, 30-day complications, re-admissions, and 3-year survival rates. Oncological data were collected from histopathology reports and postoperative MDT records, encompassing histology, grade of differentiation, Dukes’ stage, TNM stage, lymph node yield, and resection margins.

Participants were categorised into two groups based on the method of colon or mesenteric mobilisation: lateral to medial group (LM) and medial to lateral group (ML). We provide a comprehensive comparison of medial to lateral (ML) versus lateral to medial (LM) approaches across various types of colorectal resections. This approach reflects real-world clinical practice where surgeons utilise both ML and LM techniques for different types of colorectal surgeries. The primary outcome was 30-day complication occurrence, classified according to Clavien–Dindo classifications8. Secondary outcomes included operative duration, length of hospital stay, lymph node harvest, and 3-year survival.

Data were analysed using SPSS v 28, with significance set at P less than 0.05. Significance testing was performed only for variables that coincided with our study outcomes. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages, analysed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were presented as median and Interquartile range, with the Mann–Whitney U test for comparison. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox regression analysis were performed to determine hazard ratios. This work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria8.

Results

During the study period, colorectal cancer resection was performed on 586 patients, following predefined criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 176 patients. An additional eight patients were excluded due to incomplete data, yielding a final analysis comprising 402 patients.

Clinical demographics are presented in Table 1, illustrating that 30.3% were in the lateral to medial (LM) group and 69.7% in the medial to lateral (ML) group. The mean age (SD) was 68.3 (11.7) years, showing a comparable distribution in both groups. Males constituted 55.7% of the overall cohort, with a higher proportion of females in the LM group (51.6%) and males in the ML group (58.9%). The overall mean BMI (SD) was 28.1 (5.1), with no significant difference between the groups (P=0.625). The majority of patients were ASA 2 (57.7%) or ASA 3 (26.9%), with similar distributions across groups (P=0.574). Common co-morbidities included hypertension (45.0%) and diabetes mellitus (14.2%), with consistent prevalence across both groups. Predominant presenting symptoms included bleeding per rectum (29.9%), change in bowel habits (26.9%), and iron deficiency anaemia (23.9%). Tumour distribution revealed the rectum as the most common site (31.1%), followed by the sigmoid colon (21.6%), ascending colon (15.9%), and caecum (15.4%). The LM group exhibited similar trends, while the ML group demonstrated different frequencies, with the rectum (30.7%) being most frequent, followed by the sigmoid colon (26.4%), ascending colon (14.3%), and caecum (12.9%). The majority of operations were completed laparoscopically (90.5%), with comparable proportions in both groups (P=0.570). Right hemicolectomy was the most common operation (39.1%), followed by anterior resection (37.3%).

Table 1.

Clinical demographics

| Clinical demographic | Variable | Total (n=402) | Lateral to medial (LM) (n=122) | Medial to lateral (ML) (n=280) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year); Mean (SD) | 68.3 (11.7) | 70.7 (11.9) | 67.3 (11.5) | 0.007 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 178 (44.3) | 63 (51.6) | 115 (41.1) | 0.050 |

| Male | 224 (55.7) | 59 (48.4) | 165 (58.9) | ||

| BMI; Mean (SD) | 28.1 (5.1) | 27.9 (5.1) | 28.2 (5.2) | 0.625 | |

| ASA, n (%) | Score 1 | 58 (14.4) | 17 (13.9) | 41 (14.6) | 0.574 |

| Score 2 | 232 (57.7) | 70 (57.4) | 162 (57.9) | ||

| Score 3 | 108 (26.9) | 35 (28.7) | 73 (26.1) | ||

| Score 4 | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | Hypertension | 181 (45.0) | 57 (46.7) | 124 (44.3) | 0.652 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 (14.2) | 17 (13.9) | 40 (14.3) | 0.926 | |

| Asthma | 30 (7.5) | 7 (5.7) | 23 (8.2) | 0.385 | |

| COPD | 25 (6.2) | 5 (4.1) | 20 (7.1) | 0.245 | |

| AF | 20 (5.0) | 6 (4.9) | 14 (5.0) | 0.976 | |

| Heart failure | 15 (3.7) | 7 (5.7) | 8 (2.9) | 0.161 | |

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | CIBH | 108 (26.9) | 41 (33.6) | 67 (23.9) | 0.044 |

| PR bleeding | 120 (29.9) | 34 (27.9) | 86 (30.7) | 0.567 | |

| Abdominal pain | 74 (18.4) | 24 (19.7) | 50 (17.9) | 0.666 | |

| IDA | 96 (23.9) | 38 (31.1) | 58 (20.7) | 0.024 | |

| Weight loss | 41 (10.2) | 16 (13.1) | 25 (8.9) | 0.202 | |

| Constipation | 24 (6.0) | 10 (8.2) | 14 (5.0) | 0.214 | |

| Obstruction | 11 (2.7) | 4 (3.3) | 7 (2.5) | 0.660 | |

| Tumour location, n (%) | Appendix | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 0.048 |

| Caecum | 62 (15.4) | 26 (21.3) | 36 (12.9) | ||

| Ascending colon | 64 (15.9) | 24 (19.7) | 40 (14.3) | ||

| Hepatic flexure | 22 (5.5) | 8 (6.6) | 14 (5.0) | ||

| Transverse colon | 21 (5.2) | 7 (5.7) | 14 (5.0) | ||

| Splenic flexure | 6 (1.5) | 2 (1.6) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Descending colon | 8 (2.0) | 1 (0.8) | 7 (2.5) | ||

| Sigmoid colon | 87 (21.6) | 13 (10.7) | 74 (26.4) | ||

| Rectosigmoid | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Rectum | 125 (31.1) | 39 (31.9)) | 86 (30.7) | ||

| Anus | 4 (1.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Operation mode, n (%) | Laparoscopic | 364 (90.5) | 112 (91.8) | 252 (90.0) | 0.570 |

| Converted open | 38 (9.5) | 10 (8.2) | 28 (10.0) | ||

| Operation name, n (%) | Right hemicolectomy | 157 (39.1) | 64 (40.7) | 93 (59.3) | 0.003 |

| Extended right hemi | 20 (5.0) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | ||

| Left hemicolectomy | 8 (2.0) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | ||

| Sigmoid colectomy | 27 (6.7) | 2 (7.4) | 25 (92.6) | ||

| Hartman’s | 9 (2.2) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | ||

| Subtotal colectomy | 3 (0.7) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Pan proctocolectomy | 2 (0.5) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Anterior resection | 150 (37.3) | 41 (27.3) | 109 (72.7) | ||

| APER | 20 (5.0) | 5 (25.0) | 15 (75.0) | ||

| ELAPE | 6 (1.5) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; APER, abdominoperineal excision of rectum; ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; CIBH, change in bowel habits; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ELAPE, extralevator abdominoperineal excision; IDA, iron deficiency anaemia.

Table 2 details the 30-day outcomes, with 79.3% experiencing no complications (77% in LM vs. 80% in ML). The most common Clavien–Dindo complication grades were Grade 1 (9.5%) and Grade 2 (6.5%), with similar reflections across both groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P=0.764). Wound infection occurred in 5% (14/280) and 3.2% (4/122) of patients in the ML and LM groups, respectively (P=0.443). The anastomotic leak rate was similar in the two groups (2.5%: P=0.981). Five patients (4.1%) returned to theatre in the LM group compared to 11 (3.9%) in the ML group (P=0.936). Ileus was more commonly observed in the LM group (n=22, 18%) than the ML group (n=13, 4.6%), though the result was not statistically significant (P=0.596). The overall 30-day readmission rate was 9.5% (38/402), with 9.0% and 9.6% in LM and ML groups, respectively (P=0.844).

Table 2.

30-day outcomes (complications, Clavien–Dindo grading, re-admissions)

| Clinical demographic | Variable | Total N=402 | Lateral to Medial (LM) N=122 | Medial to Lateral (ML) N=280 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications, n (%) | Wound infection | 18 (4.8) | 4 (3.2) | 14 (5.0) | 0.443 |

| Anastomotic leak | 10 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) | 7 (2.5) | 0.981 | |

| Return to theatre | 16 (4.0) | 5 (4.1) | 11 (3.9) | 0.936 | |

| Ileus | 35 (8.7) | 22 (18.0) | 13 (4.6) | 0.596 | |

| AKI | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Pulmonary complication | 14 (3.5) | 4 (3.2) | 10 (3.6) | ||

| Sepsis | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Abdominal collection | 8 (2.0) | 3 (2.5) | 5 (1.8) | ||

| UTI | 4 (1.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Ureter injury | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Bleeding | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 3 (1.1) | ||

| High stoma output | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Death | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | 0.910 | |

| Clavien–Dindo Grade, n (%) | No complication | 319 (79.3) | 94 (77.0) | 225 (80.4) | 0.764 |

| 1 | 38 (9.5) | 15 (12.3) | 23 (8.2) | ||

| 2 | 26 (6.5) | 8 (6.6) | 18 (6.4) | ||

| 3 | 16 (4.0) | 4 (3.3) | 12 (4.3) | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Re-admission, n (%) | 38 (9.5) | 11 (9.0) | 27 (9.6) | 0.844 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; UTI, urinary tract infection.

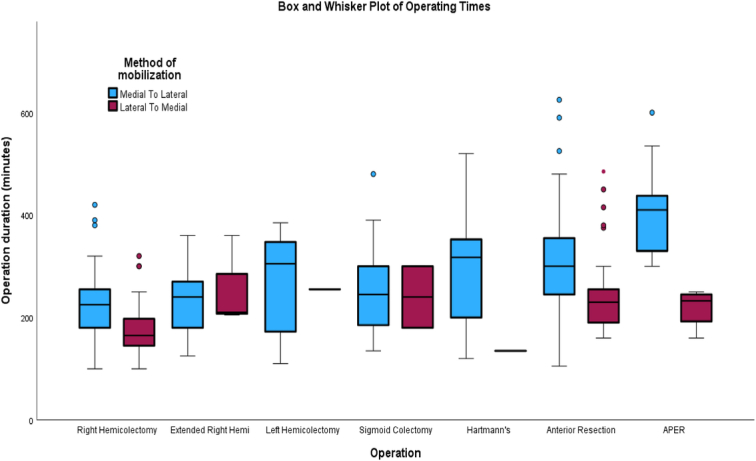

Table 3 demonstrates the operative duration in the LM group to be significantly shorter compared to the ML group (P<0.001). The mean (SD) operative time in the LM and ML groups was 213 (80.8) and 274 (94.9) minutes, respectively, while the median (IQR, range) in the two groups was 195 (85, 100–570) and 255 (118, 100–625) min, respectively (Table 3). Subgroup analysis was performed on individual operations comparing the two groups. Right hemicolectomy had a much shorter operative duration in the LM group compared to the ML group (Median 165 vs. 225 min), and this was statistically significant (P<0.001). Similar trends of shorter operative time were identified in the LM group in anterior resections (Median 230 vs. 300 min: P≤0.001) and APER (Median 233 vs. 410 min: P<0.001), as shown in Table 4 and Figure 1.

Table 3.

Overall operative duration in the two groups (min)

| Lateral to medial (LM) (min) | Medial to lateral (ML) (min) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operation duration (min) mean (SD) | 213.6 (80.8) | 274.9 (94.9) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 195 (85, 100–570) | 255 (118, 100–625) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Table 4.

Operative duration of individual operations (min)

| Operation | Mean (min) | Range (min) | IQR (min) | Median (min) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right hemicolectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 223 | 100–420 | 75 | 225 | <0.001 |

| Lateral to medial | 176 | 320–100 | 54 | 165 | |

| Extended right hemicolectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 234 | 125–360 | 108 | 240 | 0.603 |

| Lateral to medial | 258 | 205–360 | — | 210 | |

| Left hemicolectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 263 | 110–385 | 190 | 305 | 0.948 |

| Lateral to medial | |||||

| Sigmoid colectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 265 | 135–480 | 133 | 245 | 0.703 |

| Lateral to medial | 240 | 180–300 | — | 240 | |

| Hartmann’s Procedure | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 298 | 120–520 | 184 | 318 | 0.267 |

| Lateral to medial | |||||

| Subtotal colectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 408 | 210–605 | — | 408 | 0.789 |

| Lateral to medial | |||||

| Pan proctocolectomy | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 405 | 240–570 | — | 405 | NA |

| Lateral to medial | |||||

| Anterior resection | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 303 | 105–625 | 113 | 300 | <0.001 |

| Lateral to medial | 246 | 160–485 | 75 | 230 | |

| APER | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 404 | 300–600 | 120 | 410 | <0.001 |

| Lateral to medial | 219 | 160–250 | 71 | 233 | |

| ELAPE | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 380 | 160–520 | 300 | 420 | 0.730 |

| Lateral to medial | 425 | 410–440 | — | 425 | |

| Right-sided resections | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 225 | 100–420 | 75 | 225 | <0.001 |

| Lateral to medial | 180 | 100–360 | 60 | 165 | |

| Left-sided resections | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 271 | 110–520 | 164 | 283 | 0.299 |

| Lateral to medial | 218 | 135–300 | 143 | 218 | |

| Anorectal resections | |||||

| Medial to lateral | 317 | 105–625 | 114 | 300 | <0.001 |

| Lateral to medial | 252 | 160–485 | 80 | 240 | |

APER, abdominoperineal excision of rectum; ELAPE, extralevator abdominoperineal excision; IQR, interquartile range, NA, not applicable.

Figure 1.

Box and Whisker plot of operating times (individual operations). APER, abdominoperineal excision of rectum.

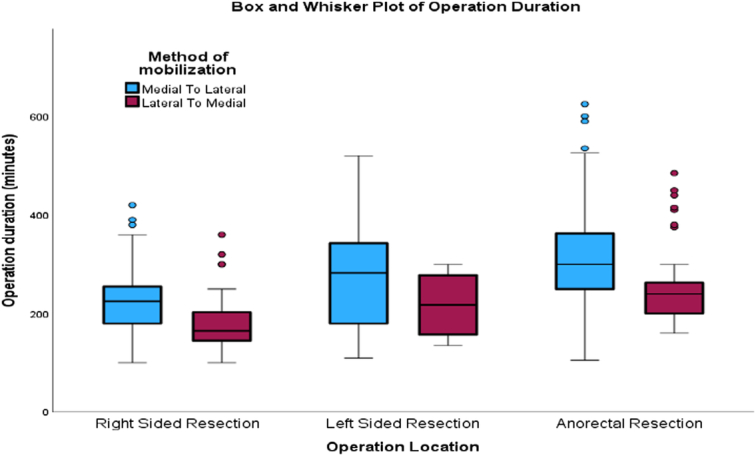

Figure 2 demonstrates operations grouped into ‘right-sided resection’ (right hemicolectomy and extended right hemicolectomy), ‘left-sided resection’ (left hemicolectomy, sigmoid colectomy, and Hartmann’s), and ‘anorectal resections’ (anterior resection and Extralevator abdominoperineal excision). Both right-sided resections (Median 165 vs. 225 min) and anorectal resections (Median 240 vs. 300 min) had a shorter operative duration in the LM group, and this was statistically significant (P<0.001). Although left-sided resections also had a shorter operative duration in the LM group (Median 218 vs. 283 min), this was not statistically significant (P=0.299). Overall, the mean (SD) length of stay was 8 (4) days with a median (IQR, range) of 6 (5, 2–54) days. The mean length of stay in the LM and ML groups was 8.5 and 7.9 days, respectively, and this was not statistically significant (P=0.446). Comparison of the length of stay of individual operations among the two groups is shown in Table 5, and the results were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Box and Whisker plot of operating times based on side of resection.

Table 5.

Length of stay (overall and individual operations)

| Operation | Lateral to medial (LM) | Medial to lateral (ML) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.0 (4) | 8.5 (7) | 7.9 (7.1) | 0.446 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 6 (5, 2–54) | 6 (5, 2–45) | 5 (4, 2–54) | |

| Right hemicolectomy | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (6.8) | 6.7 (6.9) | 0.322 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 6 (5, 2–37) | 5 (2, 2–42) | ||

| Extended right hemicolectomy | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.3 (9.5) | 8.3 (5.4) | 0.311 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 9 (—, 5–23) | 7 (6, 2–21) | ||

| Left hemicolectomy | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2 (—) | 7 (4.7) | 0.361 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | — | 5 (5, 4–17) | ||

| Sigmoid colectomy | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4 (—) | 5.9 (4.1) | 0.513 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 5 (2, 3–21) | |||

| Hartmann’s | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9 (—-) | 14.8 (9.3) | 0.569 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 14 (15, 4–32) | |||

| Anterior resection | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (5.5) | 8.5 (7.8) | 0.848 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 7 (6, 2–23) | 6 (5, 3–54) | ||

| APER | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.6 (16.6) | 9.1 (6.5) | 0.209 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 9 (23, 5–45) | 6 (6, 3–22) | ||

| ELAPE | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.5 (4.9) | 9.5 (4.8) | 0.225 | |

| Median (IQR, range) | 16 (—, 12–19) | 10 (9, 4–14) | ||

APER, abdominoperineal excision of rectum; ELAPE, extralevator abdominoperineal excision; IQR, interquartile range.

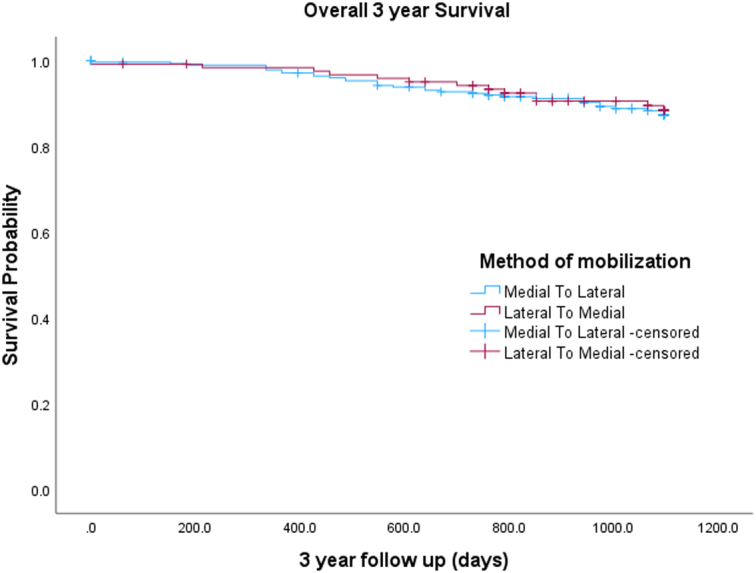

Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology in either group, with 93.4% in LM or 94.6% in ML. Most tumours were moderately differentiated, with 77% in the LM and 74.8% in ML groups. Dukes’ and TNM staging were comparable in the two groups. A total of 3.3% (4/122) in the LM and 1.8% (5/280) in the ML group had R1 resection, but this was not statistically significant (P=0.352), as shown in Table 6. The mean and median lymph node yield in the two groups were comparable, with no statistically significant difference (P=0.848). Table 7 demonstrates the overall and individual operation lymph node yield in the two groups, with no statistically significant difference observed. The 3-year overall survival rate was analysed between the two groups. In the LM group, 13 patients (10.7%) died over a 3-year period compared to 32 patients (11.4%) in the ML group. A Log-rank test was used to ascertain any difference between the two groups. Overall 3-year survival was similar in the two groups (Log-rank 0.759) in Figure 3. Cox regression analysis is depicted in Table 8 to ascertain the significant co-variants between the two groups, including demographics, side of resection, symptoms, co-morbidities, and postoperative histology. None of the co-variants had a statistically significant difference.

Table 6.

Post-operative histology outcomes

| Postoperative Outcome | Variable | Total N=402 | Lateral to medial (LM) N=122 | Medial to lateral (ML) N=280 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology, n (%) | Adenocarcinoma | 379 (94.2) | 114 (93.4) | 265 (94.6) | 0.480 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 10 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) | 7 (2.5) | ||

| Neuroendocrine | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (1.1) | ||

| No residual malignancy | 7 (1.7) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | ||

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Grade of differentiation, n (%) | Well | 45 (11.2) | 14 (11.5) | 31 (11.1) | 0.826 |

| Moderate | 303 (75.4) | 94 (77.0) | 209 (74.6) | ||

| Poor | 45 (11.2) | 11 (9.0) | 34 (12.1) | ||

| Not graded | 9 (2.2) | 3 (2.5) | 6 (2.1) | ||

| Duke’s stage, n (%) | A | 65 (16.2) | 19 (15.6) | 46 (16.4) | 0.200 |

| B | 177 (44.0) | 56 (45.9) | 121 (43.2) | ||

| C1 | 130 (32.3) | 33 (27.0) | 97 (34.6) | ||

| C2 | 6 (1.5) | 3 (2.5) | 3 (1.1) | ||

| D | 12 (3.0) | 7 (5.7) | 5 (1.8) | ||

| No grade | 12 (3.0) | 4 (3.3) | 8 (2.9) | ||

| TNM, n (%) | T0 | 11 (2.7) | 4 (3.3) | 7 (2.5) | 0.566 |

| T1 | 42 (10.4) | 9 (7.4) | 33 (11.8) | ||

| T2 | 76 (18.9) | 27 (22.1) | 49 (17.5) | ||

| T3 | 208 (51.7) | 61 (50.0) | 147 (52.5) | ||

| T4 | 65 (16.2) | 21 (17.2) | 44 (15.7) | ||

| N0 | 263 (65.4) | 87 (71.3) | 176 (62.9) | 0.567 | |

| N1 | 95 (23.6) | 27 (22.1) | 68 (24.3) | ||

| N2 | 44 (10.9) | 11 (9.0) | 33 (11.8) | ||

| M0 | 380 (94.5) | 113 (92.6) | 267 (95.4) | 0.259 | |

| M1 | 22 (5.5) | 9 (7.4) | 13 (4.6) | ||

| R, n (%) | R0 | 393 (97.8) | 118 (96.7) | 275 (98.2) | 0.352 |

| R1 | 9 (2.2) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (1.8) |

Table 7.

Lymph node yield—individual operations

| Operation name | Lateral to medial | Medial to lateral | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 0.848 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 17 (8, 0–51) | 17 (10, 0–51) | |

| Right hemicolectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18 (8) | 20 (7) | 0.200 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 17 (8, 0–42) | 19 (9, 0–44) | |

| Extended right hemicolectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 31 (18) | 19 (6) | 0.021 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 26 (—, 17–51) | 17 (9, 11–30) | |

| Left hemicolectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19 (—) | 14 (4) | 0.301 |

| Median (IQR, range) | — | 15 (6, 9–21) | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13 (6) | 15 (6) | 0.789 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 13 (—, 9–18) | 14 (7, 5–31) | |

| Hartmann’s | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14 (—) | 18 (6) | 0.586 |

| Median (IQR, range) | — | 15 (12, 12–29) | |

| Subtotal colectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 37 (—) | 17 (1) | 0.055 |

| Median (IQR, range) | — | 17 (—, 16–18) | |

| Pan proctocolectomy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 19 (—, 18–21) | ||

| Anterior resection | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16 (6) | 18 (9) | 0.285 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 17 (8, 0–29) | 16 (9, 0–51) | |

| APER | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17 (5) | 18 (6) | 0.849 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 17 (8, 12–24) | 17 (8, 10–35) | |

| ELAPE | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.523 |

| Median (IQR, range) | 9 (—, 6–11) | 9 (3, 9–13) | |

APER, abdominoperineal excision of rectum; ELAPE, extralevator abdominoperineal excision; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve for 3-year survival (overall).

Table 8.

Cox regression analysis between two groups

| Variable adjusted | Unadjusted hazards ratio (95% CI) | P | Adjusted hazards ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral to medial | 0.90 (0.48–1.72) | 0.760 | 0.95 (0.44–2.04) | 0.897 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.019 | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | 0.007 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 1.07 (0.59–1.91) | 0.833 | 0.93 (0.45–1.94) | 0.851 |

| BMI | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 0.627 | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.666 |

| Tumour location | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.144 | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 0.284 |

| Operation mode (lap vs. open) | 0.74 (0.29–1.87) | 0.534 | 0.68 (0.23–2.01) | 0.489 |

| Operation Duration | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.879 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.269 |

| Lateral to medial | 0.90 (0.48–1.72) | 0.760 | 0.95 (0.44–2.04) | 0.897 |

| Right-sided resections | 1.63 (0.91–2.94) | 0.102 | ||

| Left-sided resections | 1.27 (0.54–2.99) | 0.589 | ||

| Anorectal resections | 0.56 (0.29–1.05) | 0.069 | ||

| Lateral to medial | 0.90 (0.48–1.72) | 0.760 | 0.79 (0.41–1.55) | 0.504 |

| CIBH | 1.65 (0.90–3.01) | 0.104 | 1.77 (0.92–3.39) | 0.089 |

| Rectal bleeding | 0.91 (0.48–1.73) | 0.772 | 0.86 (0.43–1.72) | 0.664 |

| Abdominal pain | 1.77 (0.91–3.43) | 0.091 | 1.22 (0.55–2.69) | 0.621 |

| IDA | 1.12 (0.57–2.20) | 0.753 | 1.19 (0.59–2.42) | 0.629 |

| Weight loss | 2.01 (0.94–4.32) | 0.073 | 1.59 (0.70–3.65) | 0.265 |

| Constipation | 1.10 (0.34–3.56) | 0.869 | 0.69 (0.19–2.46) | 0.574 |

| Bowel obstruction | 4.03 (1.44–11.26) | 0.008 | 3.35 (0.99–11.27) | 0.051 |

| Lateral to medial | 0.90 (0.48–1.72) | 0.760 | 0.96 (0.49–1.84) | 0.891 |

| Hypertension | 0.99 (0.55–1.78) | 0.976 | 1.04 (0.56–1.93) | 0.899 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.59 (0.21–1.65) | 0.317 | 0.57 (0.19–1.63) | 0.290 |

| Asthma | 1.74 (0.69–4.41) | 0.243 | 1.79 (0.70–4.61) | 0.223 |

| COPD | 3.00 (1.34–6.73) | 0.008 | 2.93 (1.23–6.63) | 0.010 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 2.11 (0.75–5.89) | 0.156 | 1.98 (0.68–5.79) | 0.212 |

| Heart failure | 1.34 (0.33–5.54) | 0.685 | 1.33 (0.29–6.05) | 0.710 |

| Lateral to medial | 0.90 (0.48–1.72) | 0.760 | 0.79 (0.39–1.57) | 0.503 |

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 1.00 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.45 (0.35–5.98) | 0.609 | 1.06 (0.23–4.89) | 0.939 |

| Grade of differentiation | ||||

| Well | 1.00 | |||

| Moderate | 0.88 (0.34–2.28) | 0.795 | 0.65 (0.24–1.74) | 0.389 |

| Poor | 2.73 (0.95–7.87) | 0.063 | 1.34 (0.43–4.16) | 0.615 |

| Dukes stage | ||||

| A | 1.00 | |||

| B | 0.88 (0.27–2.84) | 0.825 | 0.54 (0.11–2.67) | 0.447 |

| C | 3.93 (1.38–11.2) | 0.011 | 0.98 (0.11–9.10) | 0.987 |

| D | 8.73 (2.17–35.02) | 0.002 | 3.32 (0.26–42.15) | 0.355 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | 1.00 | |||

| T2 | 0.69 (0.16–3.11) | 0.634 | 0.82 (0.17–3.90) | 0.804 |

| T3 | 1.50 (0.45–5.01) | 0.510 | 1.37 (0.27–6.91) | 0.705 |

| T4 | 4.46 (1.29–15.31) | 0.018 | 2.52 (0.47–13.59) | 0.281 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | 1.00 | |||

| N1 | 3.28 (1.60–6.73) | 0.001 | 1.72 (0.32–9.35) | 0.532 |

| N2 | 7.26 (3.49–15.05) | <0.001 | 3.00 (0.51–17.65) | 0.224 |

| M stage | ||||

| M0 | 1.00 | |||

| M1 | 3.90 (1.74–8.75) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.27–2.98) | 0.859 |

| R malignancy | ||||

| R0 | 1.00 | |||

| R1 | 2.59 (0.63–10.69) | 0.189 | 1.31 (0.29–6.00) | 0.731 |

CIBH, change in bowel habits; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IDA, iron deficiency anaemia.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the outcomes of medial to lateral (ML) versus lateral to medial (LM) mobilisation approaches in laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections, contributing to the limited existing evidence on this topic. Traditionally, the lateral to medial approach dominated colorectal cancer resections during the open surgery era, transitioning to laparoscopic surgery with a subsequent trend toward ML approach, which is widely adopted today9. This retrospective study, involving 402 patients analysed prospectively collected data, contains the second largest study population compared to previous studies10–12. Our results demonstrated a shorter operative duration in the LM group, a finding not entirely consistent with existing literature6. The incidence of right colon and rectal cancers in the study reflected a gradual increase reported in recent studies.

In contrast to some prior research, our study noted a significantly reduced operative time in the LM group12–14. Subgroup analysis highlighted the consistency of this finding in both right-sided and anorectal resections. The shorter operative time observed in the LM group could be attributed to the surgeon’s transition from a traditional lateral to medial approach in the open era5. This familiarity may have facilitated quicker adoption and implementation of the laparoscopic technique, compared to performing the entire operation using a novel approach.

The study revealed comparable 30-day postoperative outcomes between the LM and ML groups, with a non-significant increase in postoperative ileus in the LM group, similar to the results in another retrospective cohort study11. The absence of significant intraoperative complications aligns with the overall safety of both approaches. However, the incidence of ileus may be influenced by technical aspects, such as the initial dissection starting laterally in the LM approach, potentially causing increased traction on the colon15. Notably, no significant differences were identified in terms of 30-day complication rates, operative blood loss, and length of hospital stay between the two groups, although the median length of stay was slightly shorter in the ML group. One explanation of less blood loss in ML group as mentioned by in previous studies10 can be that in the ML technique the vessels are ligated and divided early thus reducing the risk of bleeding. Furthermore, the reduced median length of stay may be attributed to the reduced incidence of postoperative ileus and earlier return of bowel function10,11.

The median number of lymph nodes obtained in the two groups in our study was 17 (P=0.848). Even on subgroup analysis based on the operation, we did not identify any statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 7). One previous study also did not identify any difference in the lymph node yield in the two groups16; however other this was contrasted with increased lymph node yield in the medial group in other papers10,17. This may emphasise on factors such as the proximal ligation of the pedicle and the method of mesenteric division may influence the outcome on lymph node yield14. In our study we did not specifically investigate these factors related to lymph node yield, but what is an adequate lymphadenectomy is still subject to debate18,19. The 3-year overall survival rates did not exhibit significant differences between the LM and ML groups, aligning with similar findings in the literature6.

There are some limitations of this study. Firstly, it being a retrospective study, with the potential for selection bias. To mitigate this effect, a clear and precise inclusion and exclusion criterion were used. In addition, due to the retrospective nature of the study equal group sizes were not maintained, which can also contribute to the possible selection bias. Secondly, the operations were performed by a number of surgeons with variable experience and potentially variable operative times which may require further sub-analysis in future studies. This may have been a confounding factor between the two groups. Thirdly, as mentioned above, there are several factors that can affect lymph node yield, but this was not included in the study. Another limitation is the survival follow-up. The overall survival was reported and not disease-free survival or recurrence. Lastly, the length of follow-up would ideally have been at least 5 years duration.

In conclusion, this study, the second largest of its kind, contributes valuable insights to the ongoing debate on the optimal mobilisation approach in colorectal cancer resections. While it did not conclusively demonstrate superiority of ML over LM, it did reveal a shorter operative time in the LM group and a reduced incidence of postoperative ileus in the ML group. Large-scale randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up periods are warranted to provide a more definitive understanding of the comparative efficacy and outcomes associated with each approach. Nonetheless, the study suggests that both ML and LM approaches are acceptable and offer favourable outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as no participants were recruited for this study and no clinical intervention was implemented. This purely a retrospective data analysis within retrospectively maintained databases within the hospital trust and therefore this project was deemed as a service improvement project.

Consent

No consent required for this study as this was deemed a service improvement project.

Source of funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

M.I.: study concept, design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. K.A.: data analysis, manuscript writing. S.P.: data collection and analysis. W.C.: data collection and analysis. W.R.: data collection and analysis. S.-J.W.: project supervisor.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

researchregistry9956.

Guarantor

Muhammad Rafaih Iqbal.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Provenance and peer review

Not applicable.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital library facilities for their availability and helpful staff.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Rafaih Iqbal, Email: drmriqbal@hotmail.com.

Kaso Ari, Email: kasoari@doctors.org.uk.

Spencer Probert, Email: Spencer.probert@nhs.net.

Wenyi Cai, Email: Wenyi.cai2@nhs.net.

Wafaa Ramadan, Email: Wafaa.ramadan@nhs.net.

Sarah-Jane Walton, Email: Sarah-jane.walton@nhs.net.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK 2023 . Bowel cancer statistics. Assessed 15 July, 2023. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer

- 2.Fleshman J Sargent DJ Green E et al. Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group . Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg 2007;246:655–662; discussion 662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faiz O. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland (ACPGBI): Guidelines for the Management of Cancer of the Colon, Rectum and Anus (2017) - Audit and Outcome Reporting. Colorectal Dis 2017;19(suppl 1):71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You YN Hardiman KM Bafford A et al. On Behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons . The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2020;63:1191–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillou PJ Quirke P Thorpe H et al. MRC CLASICC trial group . Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:1718–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Navid A, et al. Meta-analysis of medial-to-lateral versus lateral-to-medial colorectal mobilisation during laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veldkamp R Gholghesaei M Bonjer HJ et al. European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) . European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) laparoscopic resection of colon cancer: consensus of the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc 2004;18:1163–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew G, Agha R, for the STROCSS Group . STROCSS 2021: Strengthening the Reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in Surgery. Int J Surg 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau WY, Leow CK, Li AK. History of endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery. World J Surg 1997;21:444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poon JT, Law WL, Fan JK, et al. Impact of the standardized medial-to-lateral approach on outcome of laparoscopic colorectal resection. World J Surg 2009;33:2177–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain A, Mahmood F, Torrance AW, et al. Impact of medial-to-lateral vs lateral-to-medial approach on short-term and cancer-related outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;26:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan J, Ying MG, Zhou D, et al. A prospective randomized control trial of the approach for laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy: medial-to-lateral versus lateral-to-medial. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2010;13:403–405; Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang JT, Lai HS, Huang KC, et al. Comparison of medial-to-lateral versus traditional lateral-to-medial laparoscopic dissection sequences for resection of rectosigmoid cancers: randomized controlled clinical trial. World J Surg 2003;27:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, et al. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:354–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turnbull RB, Jr, Kyle K, Watson FR, et al. Cancer of the colon: the influence of the no-touch isolation technic on survival rates. Ann Surg 1967;166:420–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotholtz NA, Bun ME, Tessio M, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy: medial versus lateral approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009;19:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honaker M, Scouten S, Sacksner J, et al. A medial to lateral approach offers a superior lymph node harvest for laparoscopic right colectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016;31:631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeples C, Shellnut J, Wasvary H, et al. Predictive factors affecting survival in stage II colorectal cancer: is lymph node harvesting relevant? Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg R, Friederichs J, Schuster T, et al. Prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer is associated with lymph node ratio: a single-center analysis of 3,026 patients over a 25-year time period. Ann Surg 2008;248:968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.