Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa, or acne inversa, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with recurrent inflammatory nodules, abscesses, subcutaneous tracts, and scars. This condition may cause severe psychological distress and reduce the quality of life for affected individuals. It is considered to have one of the most damaging effects on quality of life of any skin disorder as a result of the discomfort and foul-smelling discharge from these lesions. Although the pathophysiology of HS is still unclear, multiple factors, including lifestyle, genetic, and hormonal factors, have been associated with it. The pathogenesis of HS is very complex and has wide clinical manifestations; thus, it is quite challenging to manage and often requires the use of combination treatments that must be tailored according to disease severity and other patient-specific factors. Although lifestyle changes, weight loss, quitting smoking, topical treatments, and oral antibiotics are adequate for mild cases, the challenge for healthcare professionals is dealing with moderate-to-severe HS, which often does not respond well to traditional approaches. This literature review, consisting of an overview of the various assessment tools and therapy strategies available for the diagnosis and treatment of HS from published literature, aims to be a guide for practicing clinicians in dealing with the complexities associated with this disease.

Keywords: acne inversa, hidradenitis suppurativa diagnosis, hidradenitis suppurativa treatment, hidradenitis suppurativa

Introduction

Highlights

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is considered to have one of the most damaging effects on the quality of life of any skin disorder.

A multidisciplinary team of dermatologists, surgeons, psychiatrists/mental health professionals, and pain specialists is required for the best management of patients with HS.

Individualizing treatments according to the severity of the disease, treatment response, and the presence of co-morbidities is quite an important consideration in managing affected patients.

Further research should focus on both expanding the current knowledge of the disease process and also on the evaluation of new treatments in clinical trials.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by recurring inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and, subsequent to this, the occurrence of subcutaneous sinus tracts and scars1. It has a significant psychological and functional impact on patients due to the discomfort and odorous discharge from the lesions2. The global prevalence of HS is estimated to be 0.00033–4.1%, with a European-US population frequency of 0.7–1.2%3. The most common age of onset is between the ages of 20 and 40; however, new-onset HS has been documented in both younger and older individuals4,5. Because of poor mental health, lost employment, reduced intimacy, chronic pain, and substance use disorders, hidradenitis suppurativa has one of the most damaging effects on quality of life of any skin disorder6–9. These lesions appear in intertriginous regions and apocrine gland-rich areas, most often in the axillary, groin, perianal, perineal, and inframammary areas10. Multiple comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, obesity, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, and spondylarthritis, have been linked to HS11,12. Because of these issues, prompt diagnosis and efficient treatment are essential.

The pathophysiology of HS is still poorly understood. As a result, HS is a complicated condition with a difficult treatment. Although lifestyle changes, weight loss, quitting smoking, topical treatments, and oral antibiotics typically suffice for managing mild cases, dealing with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), which often doesn’t respond well to traditional approaches, poses a significant challenge for healthcare professionals13.

This comprehensive review aims to offer valuable insights into the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) by comparing assessment tools and treatment options. Our goal is to shed light on effective approaches that may benefit clinicians and researchers, thereby enhancing the care and understanding of this challenging condition.

Methodology

Using keywords like ‘hidradenitis suppurativa’, ‘acne inversa’, ‘diagnosis’, ‘treatment’, ‘surgery’, and ‘medication therapy’, studies were searched in databases including PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar. This review includes case reports, case series, reviews, observational studies, randomized control trials, and meta-analyses discussing hidradenitis suppurativa. Only studies that have been published in English are included in this review. One hundred eleven papers are included in this evaluation after the studies were thoroughly extracted and analyzed.

Pathophysiology

Although the etiology of HS is still unclear, significant advances have been achieved in recent studies3. In order to create effective treatments, it is imperative to further identify the various elements that contribute to HS. HS starts with follicular occlusion, which is likely due to infundibular keratosis and hyperplasia of the follicular epithelium, leading to the retention of secretions, rupture, and release of follicular contents14. Follicular content release in the dermis triggers an immune response that activates granulocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins (IL-1, IL-17), tumor necrosis factor, and interferon, resulting in a vicious cycle of tissue destruction15. In later stages, this causes abscess formation, severe inflammation, sinus tract formation, and scarring5.

Multiple factors have been associated with HS, including lifestyle factors, genetic factors, and hormonal factors:

Lifestyle factors

Smoking, stress, and obesity are all lifestyle factors that contribute to the development of HS. A study discovered that people with HS were almost four times more likely to be smokers16. HS patients are also four times more likely to be obese than the general population, and BMI is positively correlated with disease burden17. It has also been suggested that psychological stress contributes to the onset and development of this illness. Stress can impair immune function, causing disease development or exacerbations18. Stress and worry can also lead to habits like smoking or binge eating, which can lead to the worsening of HS symptoms.

Genetic factors

In Western countries, HS normally appears as a sporadic form, but in 40% of cases, it arises as a family disorder19. Positive family histories are commonly reported by HS patients20, and autosomal dominant inheritance patterns in affected families have been identified21, which strongly suggests a genetic component to this condition. According to the genetic mutations linked to HS that have been discovered to date, HS can be inherited as a polygenic disorder brought on by abnormalities in genes controlling immune system function, ceramide synthesis, or epidermal proliferation, or as a monogenic trait caused by a defect in either the Notch signaling pathway or inflammasome function20. Chromosome 1p21.1–1q25.3 region has been linked to a mutation in the γ-secretase pathway in several families with HS patients20,22. These patients exhibit a severe phenotype of HS20. Mutations in the nicastrin (NCSTN) gene, presenilin 1 (PSEN 1), and presenilin enhancer (PSENEN) genes have all been linked to HS19,20,23–25.

Hormonal factors

Hormones are also considered a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of HS. Indicators of hormonal involvement include predominance in females, onset in puberty, and alterations in HS activity during times of changing hormones such as premenstrual periods, pregnancy, and menopause26. Activation of androgen receptors in the sebaceous gland causes increased sebum and inflammation, which can contribute to the blockage of hair follicles, ultimately leading to HS26. Although patients with HS have not been found to have greater than normal plasma levels of testosterone or 5-DHT, studies have shown that the use of anti-androgenic drugs has a beneficial response compared to antibiotic-based treatment alone26.

Diagnosis

There have been several techniques reported for assessing patients with HS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment tools for hidradenitis suppurativa.

| Assessment tool | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Hurley27–33 | Simple to use and provides rapid classification. | It is ineffective for assessing therapy responses. |

| 2. The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR)34–36 | A valid, responsive, and meaningful endpoint for assessing the treatment effectiveness of HS in both clinical research and daily practice. | Its application is limited to evaluating treatment responses. HiSCR may lack sensitivity for milder cases due to its requirement of at least three abscesses and inflammatory nodules at baseline. Does not take draining tunnels into account in a dynamic manner, which can lead to an incomplete evaluation of the treatment response. |

| 3. Modified Sartorius Score2,37,38 | Dynamic scoring system that can detect changes in clinical disease severity. | Time-consuming, especially for patients with a wide-spread illness. |

| 4. Physician Global Assessment Tool for HS (HS-PGA)38–40 | Quick and simple assessment tool. Frequently used in clinical practice and clinical trials. | Largely dependent on the clinician’s capacity to identify essential lesions of HS. |

| 5. The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Index (HSSI)38,39 | It is simple and rapid, utilizing subjective and objective criteria, and can assess disease severity without the need to differentiate between distinct elementary lesions. It also evaluates body surface area, drainage, and pain severity. | Lacks validation and lacks detail compared to the modified Sartorius score. |

| 6. The International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity (IHS4) and IHS4-5536,39,41–43 | It is a validated score that provides a dynamic assessment of HS severity in both clinical practice and the clinical trial setting. | Time-consuming due to the need for counting individual lesions, and individual lesion counts were demonstrated to differ between raters when compared to patients with milder forms of the disease. |

HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Hurley staging

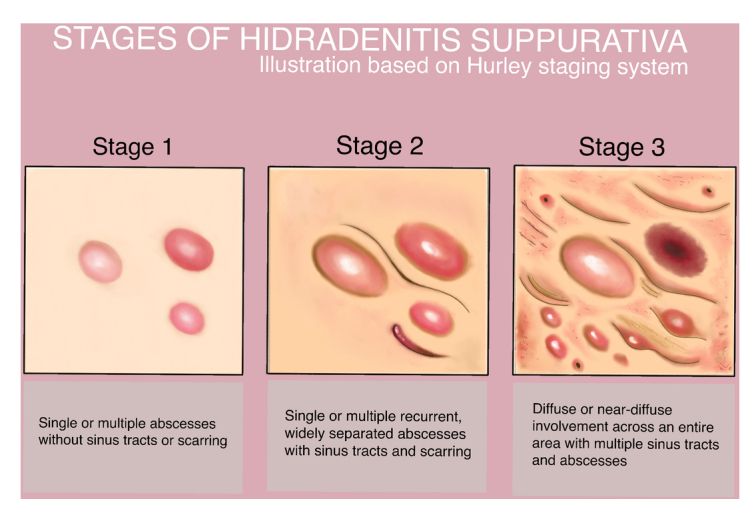

Hurley staging has been suggested in clinical settings due to its simplicity of use and rapid classification27. The Hurley scoring system is ineffective for assessing therapy response, as scarring may persist even after effective treatment28. Also, it is a static approach that is less appropriate for evaluating dynamic shifts in the severity of the illness27. Additionally, it does not measure the number of affected regions or evaluate disease activity or treatment response29. To address these limitations, the Refined Hurley staging has been developed30. The Hurley scoring system consists of three stages(Fig. 1)30:

Stage I: Single or multiple abscess formation without cicatrization or sinus tracts.

Stage II: Single or multiple recurrent abscesses, widely separated lesions with cicatrization and sinus tract.

Stage III: Diffuse or near-diffuse involvement across an entire area with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscesses.

Figure 1.

Stages of hidradenitis suppurativa according to Hurley staging system.

Since clinical examination alone can underestimate HS and thus lead to insufficient treatment, some studies recommend the classification of Hurley stage based on ultrasonography, as ultrasound could detect early alterations that are unnoticeable clinically31–33.

HiSCR

The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR) has increased sensitivity to identify treatment effects and might be a helpful tool in clinical practice and research studies to assess the success of HS therapy34. This score does not indicate a patient’s severity at a certain time, but rather whether or not the patient improved between two time points, such as after receiving therapy. According to HiSCR, responders are those who obtain at least a 50% reduction in abscess and nodule count (AN-count) without increasing the number of abscesses or draining tunnels compared to the baseline35. HiSCR is a valid, responsive, and a meaningful endpoint for assessing the treatment effectiveness of HS in both clinical research and daily practice35. HiSCR was designed and validated for patients with at least three total abscesses and inflammatory nodules at baseline, limiting its sensitivity in detecting changes in milder forms of the disease34. Additionally, HiSCR does not dynamically include draining tunnels, potentially limiting its ability to fully assess the impact of anti-inflammatory therapy36.

Modified sartorius score

This test counts individual nodules and fistulas in seven anatomical locations and measures the greatest distance between two lesions of the same type in each region2. This test is dynamic, meaning it is able to detect changes in clinical disease severity between visits37. However, calculating according to this scoring system is time-consuming, especially for patients with extensive disease38.

HS-PGA

The Physician Global Assessment Tool for HS (HS-PGA) categorizes patients into six severity levels based on the quantity of abscesses, draining fistulas, inflammatory nodules, and non-inflammatory nodules39,40. Although HS-PGA is a quick and simple assessment tool, its effectiveness is largely dependent on the clinician’s capacity to identify HS essential lesions38.

HSSI

The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Index (HSSI) consists of five components: the number of sites affected, the body surface area (BSA), the number of inflammatory lesions, the number of dressing changes reflecting the quantity of drainage, and a visual analog pain scale39. This score uses both subjective and objective criteria to assess illness severity39. Furthermore, it may be estimated without separating between distinct elementary lesions, making it simple and rapid to use39. However, this test lacks validation and is not as detailed as the modified Sartorius score38.

IHS4 and IHS4-55

The International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity (IHS4) is based on the number of inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and draining tunnels41.

IHS4-55, a revised scoring system, was created and approved in 2022. Patients are divided into two groups by IHS4-55: responders and non-responders. Patients were categorized as responders if their IHS4 score decreased by at least 55% over the course of two visits; non-responders were the remaining patients. Because of its increased inclusivity, IHS4-55 is a useful supplement to current scoring systems, enabling a more thorough evaluation of patients with HS39,42.

They rely on counting individual lesions; therefore, their usefulness is limited in more severe diseases when lesions tend to coalesce36. Furthermore, individual lesion counts were shown to differ across raters when compared to individuals with milder illnesses43.

Treatment

Different methods for the management of HS are outlined in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment options for hidradenitis suppurativa.

| Treatment | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle modification and general management Lifestyle modification44–49 Cessation of smoking Avoid rough clothing and tight underwear, jeans, belts, bras, and collars and opt for loose cotton fabrics Reducing body weight General management2,6,29,50–53 Pain management Wound care Psychological support |

Valuable adjunctive options to conventional medical treatments. Useful in situations where prescription medications are unsuitable, e.g., immunosuppression or pregnancy. No side effects. |

Insufficient as a solitary treatment strategy. It demands considerable time, dedication, and overcoming ingrained habits. |

| Topical treatment2,54

Topical clindamycin 1% Topical resorcinol 15% Skin cleansers |

Simple to use and apply, with few systemic adverse effects, suitable for milder forms of HS. | Local side effects like skin irritation or allergic reactions. Not suitable for widespread illness. |

| Intralesional therapy55–57

Steroid (triamcinolone) injections |

A safe, well-tolerated, and efficient method that is known to reduce discomfort, swelling and hasten the shrinkage of fistulous tracts and abscesses. | May result in skin atrophy, telengiectasia, and hypopigmentation. The risk of glycemic decompensation in diabetic patients requires caution. |

| Systemic antibiotics5,58–62

Oral tetracyclines (eg. doxycycline 50-100 mg twice daily) Oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily plus oral rifampicin 600 mg daily for 12 weeks Moxifloxacin (400 mg daily), rifampicin (10 mg/kg daily), and metronidazole (500 mg thrice daily) for up to 12 weeks, with discontinuation of metronidazole after 6 weeks |

A widely utilized and effective treatment option, oral antibiotics offer ease of administration and convenience, particularly for treating widespread or inaccessible areas. They can also be combined synergistically with other therapies like topicals or biologics for enhanced efficacy. |

Side effects include gastointestinal disturbances, and sun sensitivity associated with tetracyclines; Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, rash, and hepatotoxicity linked to clindamycin; orange-tinged bodily fluids resulting from rifampin use; and methemoglobinemia and cyanosis of the lips associated with dapsone. Risk of leading to bacterial resistance |

| Biologics63–68

Adalimumab on Week 0 (160 mg S.C.), Week 2 (80 mg S.C.), and every week (40 mg S.C) for 12 weeks followed by assessment Secukinumab (300 mg weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks.) |

Biologics specifically target the underlying inflammatory pathways involved in HS, offering high efficacy, long-term disease control, and improved overall well-being. | It requires careful monitoring due to infection, drug interaction risks, and the potential for malignancy, like lymphomas. Secukinumab has been associated with Crohn's disease. |

| Surgery37,69–73

Incision and Drainage Deroofing Excision Lasers |

Offers significant advantages in severe cases of HS, particularly for addressing recurrent or persistent abscesses. | May lead to scarring, infection, bleeding, pain, wound dehiscence, and recurrence |

HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Lifestyle modification

Patients should avoid rough clothing and tight underwear, jeans, belts, bras, and collars, especially nonbreathable fabrics like polyester and nylon, as they can increase discomfort and lesion formation44, and opt for loose cotton fabrics45. Research indicates that 70–90% of HS patients smoke46. There are, however, conflicting findings about the relationship between smoking and the severity of HS47. Despite these findings, patients are suggested to avoid smoking since there is compelling evidence of the harmful pathophysiological effects of tobacco smoke and its byproducts on skin and HS lesions48. Reducing weight is highly recommended, as several studies have shown that a reduction in weight leads to major improvements45,49. Despite encouraging results, studies related to non-pharmacological therapies are inadequate. Nonetheless, they offer valuable adjunctive options to conventional medical treatments, particularly in situations where prescription medications are unsuitable, such as immunosuppression, or during pregnancy45.

General management

Pain management

One major contributing factor to the reduced quality of life experienced by people with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is pain6. HS pain is similar to persistent post-traumatic headaches and more severe than blistering diseases, vulvar lichen sclerosis, vasculitis, and leg ulcers6.

To address acute pain, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and surgical techniques (such as incision and drainage of inflammatory nodules) are recommended50. Corticosteroids injections alone or with 1% xylocaine can be used to treat inflammatory nodules50.

Management of chronic pain should be based on the WHO pain ladder29. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, pregabalin, gabapentin, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and, in more complex cases, judicious use of antidepressants may also be used for chronic pain6.

For severe pain, short-acting opioid analgesics can be prescribed individually and cautiously29.

Wound care

In a study of 50 dermatologists investigating wound care counseling in HS, the most generally prescribed dressings were abdominal pads (80%), gauze (76%), and pantyliners or menstrual pads (52%)51. The suggested methods for managing flares at home were Epsom salt baths (18%), zinc oxide lotion (28%), warm compresses (76%), bleach baths (50%), and Vicks VapoRub (12%)51. Warm compresses, followed by bleach baths and Epsom salt baths, had the largest proportion of dermatologists rating the product as outstanding for flares51.

Psychological support

Patients with HS experience severe psychological effects as a result of the discomfort and foul-smelling discharge from the lesions2. Group psychotherapy could be beneficial for these patients52. Psychological support for HS patients is critical and should be included in the disease management plan52.

Topical therapy

Topical antibiotics, keratolytic agents, and skin cleansers are all part of the topical therapy for HS. Although there is no data to support the use of any particular skin cleanser, the use of zinc pyrithione, benzoyl peroxide, and chlorhexidine is supported by professional opinion74. The most commonly used topical antibiotic for HS is clindamycin 1%. Topical clindamycin 1% twice daily for 12 weeks is the first line of management for less severe stages of HS (Hurley I–II), with its effect comparable to oral tetracyclines2. Another topical agent used in HS is resorcinol 15%, a chemical peeling agent with keratolytic and anti-inflammatory properties75. A retrospective analysis of 134 individuals with mild-to-moderate HS (Hurley stages I and II) discovered that the response to 15% resorcinol outperformed the response to topical clindamycin 1% in terms of clinical response and disease-free survival54. The same study suggested that topical resorcinol 15% may be a useful substitute for clindamycin, reducing antibiotic usage and the development of antibiotic resistance54.

Systemic antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics are a commonly utilized therapeutic strategy for HS and are indicated in every published HS treatment guideline58–60. Oral tetracyclines (e.g. doxycycline 50–100 mg twice daily) are the first-line treatment for milder diseases5. That said, it is believed that the anti-inflammatory rather than the antibacterial properties of tetracyclines and other antibiotics provide their benefits in HS58,59.

A combination of systemic antibiotics are also used for the management of HS. A study concluded that the combination of oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily with oral rifampicin 600 mg daily for 12 weeks was effective and tolerable for the majority of the patients with HS61. Certain antibiotic regimens have been proposed involving multiple antibacterial drugs, including moxifloxacin (400 mg daily), rifampicin (10 mg/kg daily), and metronidazole (500 mg thrice daily) for up to 12 weeks, with discontinuation of metronidazole after 6 weeks for HS not responding to therapy60.

Other systemic therapy

Hormonal therapy

Anti-androgenic medication has been shown to enhance clinical outcomes in female HS patients76. Hormonal agents, such as estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, metformin, and finasteride, can be used as monotherapy for mild-to-moderate HS or in combination with other medications for more severe disease74,76. In a retrospective analysis of 20 female HS patients treated with spironolactone 100 to 150 mg daily, 85% (17/20) showed improvement77. Four global case reports comprising 13 patients investigated the efficacy of finasteride (1.25–10 mg/d) for HS, collectively demonstrating the beneficial effects of finasteride in treating HS78. The link between HS and PCOS is well established, with some authors even proposing that all female patients presenting with HS be tested for underlying PCOS and insulin resistance79. Recently, several studies have been published on the advantages of metformin in HS, which have been related to its anti-inflammatory properties, effects on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, and influence on hormones like androgens80,81. Metformin may be recommended for people who have concomitant diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome62. An uncontrolled prospective study comprising 25 patients with HS, the great majority of whom were female and some had PCOS, found considerable clinical effectiveness of metformin (500 mg 2–3 times a day) in treating HS79. Women whose HS worsens with the menstrual cycle and have a shorter disease course may benefit the most from OCP therapy. It has been reported that OCPs may improve the number of abscesses and inflammatory nodules (AN) in women with HS82.

Oral isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is only recommended as a second or third line of treatment, or for people who have concomitant acne5. In a retrospective study with 39 HS participants, 14 patients (or 35.9%) indicated that isotretinoin had a positive effect83. Another retrospective analysis found a 68% isotretinoin response rate in their HS patient population. According to the same study, those who responded to isotretinoin therapy in any way were more likely to be female, younger, weigh less, and have acne84.

Cyclosporine

It has been suggested that cyclosporine might be used to treat recalcitrant HS85. According to a case study, 9 out of 18 severe HS patients responded well to cyclosporine treatment86.

Methotrexate

According to published studies, methotrexate may not be an effective treatment for HS87. However, a retrospective study suggests that methotrexate may be an effective therapy in a certain subset of patients with HS, particularly older people with lower body mass indices, although it seems ineffective in patients treated in combination with biological therapies88.

Oral steroid therapy

Oral corticosteroids are helpful as a low-dose adjuvant with biologics and other immunomodulating drugs, and they are known to offer rapid relief in acute flare-ups of HS59. High-dose systemic corticosteroids have been shown to be useful in treating HS; however, the benefit was short-lived after tapering of the dose. To establish long-term control and minimize unwanted side effects, treating HS with low-dose systemic steroids over time is an alternate treatment option89.

Intralesional steroid therapy

Intralesional steroids are beneficial in acute flares55. Intralesional triamcinolone injection into inflammatory HS lesions results in a considerable decrease in erythema, edema, suppuration, and nodule size62.

When using intralesional steroids, a prospective study with 247 lesions that evaluated ultrasound-guided intralesional steroids injections in HS patients found that 81.1% (30/37) of nodules, 72% (108/150) of abscesses, and 53.3% (32/60) of draining fistulas responded to the steroid injections55. In another retrospective, multi-center study involving HS patients receiving intralesional corticosteroid injection, 95 lesions (70.37%) exhibited a complete response, 34 showed a partial response (25.19%), and 6 (4.44%) showed no response at all56. However, according to another research, there was no statistically significant difference identified between different doses of triamcinolone and normal saline for the treatment of acute HS lesions over a period of 14 days, suggesting that steroid injections may not be as beneficial for managing acute HS as is commonly believed57. Despite there being no statistically significant difference in the effectiveness of triamcinolone injections compared to normal saline, the average patients did report experiencing some degree of improvement. The authors suggested the possibility of relief being linked to the act of puncturing a lesion or introducing an external solution57.

Biologics

Adalimumab, a TNF-α inhibitor, is the first medication approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for moderate-to-severe HS63. Adalimumab is prescribed in HS at a dosage of 160 mg on Week 0, 80 mg on Week 2, and then a 40 mg injection every week64,65. Reviewing the continuation of adalimumab medication is necessary if a patient does not exhibit improvement by week 12. Using a topical antiseptic wash on HS lesions every day is advised throughout adalimumab therapy, and antibiotics may be continued if needed64.

Until 31 October 2023, adalimumab stood as the sole FDA-approved biologic drug for HS until secukinumab was granted FDA approval for the same condition65,66. Secukinumab is a biological drug that preferentially targets interleukin-17 (IL-17)65. In a multi-center retrospective study, 31 patients who had failed or were contraindicated for at least one anti-TNF-alpha were treated with secukinumab67. In this trial, 41% of patients at week 28 attained the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response Score (HiSCR), with the sole adverse effect noted being a facial eruption resembling acne67.

Another study with twenty HS patients used subcutaneous injections of secukinumab 300 mg once a week for five weeks, then once every four weeks for a total of sixteen weeks. Seventy-five percent of patients (15/20) had a satisfactory HiSCR response after 16 weeks of treatment, whereas two individuals developed Crohn’s disease (CD) after three and five months of therapy68.

Additional biologics are under investigation for their potential application in treating HS, such as IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra90,91, canakinumab92,93), TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab94–96, etanercept97), IL-17 inhibitors (bimekizumab98), IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab99,100, risankizumab101,102), IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitor (ustekinumab103), phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (apremilast104), Janus kinase 1 inhibitor (INCB054707105), and chimeric monoclonal antibody against the CD20 protein (rituximab106,107).

Surgery

Surgery is frequently necessary and quite prevalent in HS patients since nonsurgical alternatives often result in an unsatisfactory outcome37. The location and extent of HS, as well as whether the excision is sufficient, are all important factors in the surgical process69. Local excision of single lesions is only suggested for limited, well-defined lesions of Hurley I and II37.

For patients presenting with acute, painful, fluctuant abscesses, incision and drainage (I&D) is a beneficial technique70. While its high recurrence rate makes it unsuitable for long-term practice, it is helpful in treating acute pain and suffering70. For large chronic lesions, an extensive excision, CO2, or electrosurgical excision (with or without repair) is recommended29,108.

Deroofing, a minimally invasive procedure that can be performed under local anesthesia, involves stripping the “roof” from abscesses or sinus tracts to expose lesion floors in Hurley stage I or II hidradenitis suppurativa71. Deroofing is a surgery option that provides cosmetically acceptable results and prevents contractures71. Many techniques, including primary suturing, skin grafting, flap reconstruction, and secondary healing, have been employed to promote healing of the postsurgical defects without wound contracture and postsurgical complications72. Less invasive techniques including platelet-enriched plasma, dermal replacements, and vacuum-assisted closure (VAC treatment) provide a significant boost to the reconstructive strategy70. Continuing medical treatment throughout the perioperative period may be advantageous and reduce the risk of postoperative complications29.

Lasers, such as Nd:YAG or CO2, are emerging as potential therapy techniques for hidradenitis suppurativa since they provide focused tissue destruction while reducing lesion burden with little invasiveness73. While studies have shown promising results for CO2 laser therapy, further study is needed to determine its long-term usefulness71,73.

Hyperhidrosis treatments in HS

Hyperhidrosis reduces the quality of life for people with hidradentitis suppurativa by aggravating odor and pruritus109,110. An age-adjusted and gender-adjusted multivariable logistic regression revealed a 3.61-fold (95% CI 2.83–4.61, P<0.0001) higher risk of hyperhidrosis in HS patients, indicating a link between hyperhidrosis and HS111. Treatment of hyperhidrosis in locations where individuals have HS lesions may help both illnesses109. Hyperhidrosis treatments tested in HS patients include botulinum toxin A (BTX-A), botulinum toxin B (BTX-B), suction-curettage, 1450 nm diode laser, and microwave-based energy device (MED)109. A systematic review found that treatments for hyperhidrosis, including BTX, may be helpful in the treatment of HS, while MEDs may be harmful109.

Strengths and limitations

This literature review has several strengths, such as predominantly comprising of papers published in the recent years. It provides an overview of the diagnosis and treatment options for HS and their respective advantages and disadvantages. However, this literature review has some limitations. Firstly, it does not provide the same level of evidence as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or meta-analyses. Furthermore, because this review is limited to papers published in English it may miss valuable insights from studies published in other languages.

Conclusion

This literature review gives an overview of both the assessment tools and the current therapeutic strategies for HS. Despite important advances made in recent studies, the pathophysiology of HS remains unclear. Multiple factors including lifestyle, genetic and hormonal factors are linked to the development of HS. Although various modalities of treatment exist for HS, such as lifestyle modifications, topical and systemic antibiotics, and surgical interventions, the evidence supporting their efficacy is quite limited. It is essential for patients with HS to avoid trigger factors such as smoking and obesity, wear loose-fitting cotton clothing, and apply topical therapy. In cases where a patient shows inefficacy of topical and oral antibiotics, consideration of intralesional steroids, systemic steroids, oral retinoids, hormone therapy, biologics, or other treatments is given. Surgical management may also be required for severe cases. Because no medication works universally for all patients, those with HS require personalized treatment strategies and multidisciplinary collaboration from dermatologists, surgeons, pain specialists and mental health professionals. Future research should focus on broadening the current understanding of HS pathogenesis and assessing new treatments in clinical trials.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this review.

Consent

Informed consent was not required for this review.

Source of funding

Funding was not received for this study.

Author contribution

A.P.: concept, manuscript preparation, edit and review.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The author of this paper has no conflicting interests.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Archana Pandey.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- 1.Ocker L, Abu Rached N, Seifert C, et al. Current medical and surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa-a comprehensive review. J Clin Med Res 2022;11:7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2021;12:20406223211055920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen TV, Damiani G, Orenstein LAV, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on epidemiology, phenotypes, diagnosis, pathogenesis, comorbidities and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021;35:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seyed Jafari SM, Hunger RE, Schlapbach C. Hidradenitis suppurativa: current understanding of pathogenic mechanisms and suggestion for treatment algorithm. Front Med 2020;7:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021;85:187–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chernyshov PV, Zouboulis CC, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. Quality of life measurement in hidradenitis suppurativa: position statement of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology task forces on Quality of Life and Patient-Oriented Outcomes and Acne, Rosacea and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:1633–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy S, Orenstein LAV, Strunk A, et al. Incidence of long-term opioid use among opioid-naive patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol 2019;155:1284–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel KR, Lee HH, Rastogi S, et al. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa, depression, anxiety, and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis Suppurativa [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed 14 January 2024.: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534867/

- 11.Deckers IE, Benhadou F, Koldijk MJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: Evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022;86:1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram JR, Collier F, Brown D, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa) 2018. Br J Dermatol 2019;180:1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krueger JG, Frew J, Jemec GBE, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: new insights into disease mechanisms and an evolving treatment landscape. Br J Dermatol 2023;190:149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathod U, Prasad PN, Patel BM, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a literature review comparing current therapeutic modalities. Cureus 2023;15:e43695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acharya P, Mathur M. Hidradenitis suppurativa and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi F, Lehmer L, Ekelem C, et al. Dietary and metabolic factors in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol 2020;59:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tugnoli S, Agnoli C, Silvestri A, et al. Anger, emotional fragility, self-esteem, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2020;27:527–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moltrasio C, Tricarico PM, Romagnuolo M, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a perspective on genetic factors involved in the disease. Biomedicines 2022;10:2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jfri AH, O’Brien EA, Litvinov IV, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: comprehensive review of predisposing genetic mutations and changes. J Cutan Med Surg 2019;23:519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jemec GBE. Clinical practice. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med 2012;366:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B. γ-Secretase mutation and consequently immune reaction involved in pathogenesis of acne inversa. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2015;17:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Yan Y, Wang B. γ-Secretase genetics of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic literature review. Dermatology 2021;237:698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pink AE, Simpson MA, Desai N, et al. γ-Secretase mutations in hidradenitis suppurativa: new insights into disease pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Jiang L, Huang Y, et al. A gene dysfunction module reveals the underlying pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. Australas J Dermatol 2020;61:e10–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark AK, Quinonez RL, Saric S, et al. Hormonal therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa: Review. Dermatol Online J 2017;23:13030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarchi K, Yazdanyar N, Yazdanyar S, et al. Pain and inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa correspond to morphological changes identified by high-frequency ultrasound. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vural S, Gündoğdu M, Akay BN, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical characteristics and determinants of treatment efficacy. Dermatol Ther 2019;32:e13003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: Part I: Diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81:76–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horváth B, Janse IC, Blok JL, et al. Hurley staging refined: a proposal by the dutch hidradenitis suppurativa expert group. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97:412–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston L, Dupuis E, Lam L, et al. Understanding Hurley Stage III hidradenitis suppurativa patients’ experiences with pain: a cross-sectional analysis. J Cutan Med Surg 2023;27:487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa IMC, Pompeu CB, Mauad EBS, et al. High-frequency ultrasound as a non-invasive tool in predicting early hidradenitis suppurativa fistulization in comparison with the Hurley system. Skin Res Technol 2021;27:291–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazzaro G, Passoni E, Calzari P, et al. Color Doppler as a tool for correlating vascularization and pain in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Res Technol 2019;25:830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimball AB, Sobell JM, Zouboulis CC, et al. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): a novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo-controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:989–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimball AB, Jemec GBE, Yang M, et al. Assessing the validity, responsiveness and meaningfulness of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR) as the clinical endpoint for hidradenitis suppurativa treatment. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:1434–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Straalen KR, Ingram JR, Augustin M, et al. New treatments and new assessment instruments for Hidradenitis suppurativa. Exp Dermatol 2022;31 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunger RE, Laffitte E, Läuchli S, et al. Swiss practice recommendations for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Dermatology 2017;233:113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daoud M, Suppa M, Benhadou F, et al. Overview and comparison of the clinical scores in hidradenitis suppurativa: a real-life clinical data. Front Med 2023;10:1145152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y, Lee J, Kim HS, et al. Review of scoring systems for hidradenitis suppurativa. Ann Dermatol 2024;36:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.van der Zee HH, Jemec GBE. New insights into the diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical presentations and phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S23–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Zee HH, van Huijstee JC, van Straalen KR, et al. Viewpoint on the evaluation of severity and treatment effects in mild hidradenitis suppurativa: the cumulative IHS4 (IHS4-C). Dermatology 2023;240:514–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzellos T, van Straalen KR, Kyrgidis A, et al. Development and validation of IHS4-55, an IHS4 dichotomous outcome to assess treatment effect for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023;37:395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorlacius L, Garg A, Riis PT, et al. Inter-rater agreement and reliability of outcome measurement instruments and staging systems used in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2019;181:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boer J. Should hidradenitis suppurativa be included in dermatoses showing koebnerization? Is it friction or fiction? Dermatology 2017;233:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hendricks AJ, Hirt PA, Sekhon S, et al. Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa - a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat 2021;32:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodruff CM, Charlie AM, Leslie KS. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a guide for the practicing physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1679–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dessinioti C, Zisimou C, Tzanetakou V, et al. A retrospective institutional study of the association of smoking with the severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci 2017;87:206–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bukvić Mokos Z, Miše J, Balić A, et al. Understanding the relationship between smoking and hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2020;28:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sivanand A, Gulliver WP, Josan CK, et al. Weight loss and dietary interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg 2020;24:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S47–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poondru S, Scott K, Riley JM. Wound care counseling of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: perspectives of dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol 2023;9:e096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Misitzis A, Katoulis A. Assessing psychological interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa as a first step toward patient-centered practice. Cutis 2021;107:123–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fragoso NM, Masson R, Gillenwater TJ, et al. Emerging treatments and the clinical trial landscape for hidradenitis suppurativa-part ii: procedural and wound care therapies. Dermatol Ther 2023;13:1699–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Molinelli E, Brisigotti V, Simonetti O, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical resorcinol 15% versus topical clindamycin 1% in the management of mild-to-moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study. Dermatol Ther 2022;35:e15439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvador-Rodríguez L, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Ultrasound-assisted intralesional corticosteroid infiltrations for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Sci Rep 2020;10:13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.García-Martínez FJ, Vilarrasa Rull E, Salgado-Boquete L, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid injection for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a multicenter retrospective clinical study. J Dermatolog Treat 2021;32:286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fajgenbaum K, Crouse L, Dong L, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone may not be beneficial for treating acute hidradenitis suppurativa lesions: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Surg 2020;46:685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agnese ER, Tariche N, Sharma A, et al. The pathogenesis and treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Cureus 2023;15:e49390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Topical, systemic and biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenic insights by examining therapeutic mechanisms. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2019;10:2040622319830646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zouboulis CC, Bechara FG, Dickinson-Blok JL, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: a practical framework for treatment optimization - systematic review and recommendations from the HS ALLIANCE working group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dessinioti C, Zisimou C, Tzanetakou V, et al. Oral clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa: a prospective study and 1-year follow-up. Clin Exp Dermatol 2016;41:852–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patel K, Liu L, Ahn B, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa for the nondermatology clinician. Proc 2020;33:586–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsai YC, Hung CY, Tsai TF. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecules for moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pharmaceutics 2023;15:1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim ES, Garnock-Jones KP, Keam SJ. Adalimumab: a review in hidradenitis suppurativa. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016;17:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martora F, Megna M, Battista T, et al. Adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the real-life experience. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2023;16:135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martora F, Marasca C, Cacciapuoti S, et al. Secukinumab in hidradenitis suppurativa patients who failed adalimumab: a 52-week real-life study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2024;17:159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ribero S, Ramondetta A, Fabbrocini G, et al. Effectiveness of Secukinumab in the treatment of moderate-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: results from an Italian multicentric retrospective study in a real-life setting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021;35:e441–e442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reguiaï Z, Fougerousse AC, Maccari F, et al. Effectiveness of secukinumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: an open study (20 cases). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:e750–e751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kohorst JJ, Baum CL, Otley CC, et al. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: outcomes of 590 consecutive patients. Dermatol Surg 2016;42:1030–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scuderi N, Monfrecola A, Dessy LA, et al. Medical and surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review. Skin Appendage Disord 2017;3:95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shukla R, Karagaiah P, Patil A, et al. Surgical treatment in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Clin Med Res 2022;11:2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dini V, Oranges T, Rotella L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and wound management. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2015;14:236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chawla S, Toale C, Morris M, et al. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a narrative review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2022;15:35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: Part II: Topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Molinelli E, De Simoni E, Candelora M, et al. Systemic antibiotic therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa: a review on treatment landscape and current issues. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023;12:978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abu Rached N, Gambichler T, Dietrich JW, et al. The role of hormones in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:15250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee A, Fischer G. A case series of 20 women with hidradenitis suppurativa treated with spironolactone. Australas J Dermatol 2015;56:192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khandalavala BN, Do MV. Finasteride in hidradenitis suppurativa: a “male” therapy for a predominantly “female” disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2016;9:44–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verdolini R, Clayton N, Smith A, et al. Metformin for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a little help along the way. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cho M, Woo YR, Cho SH, et al. Metformin: a potential treatment for acne, hidradenitis suppurativa and rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol 2023;103:adv18392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jennings L, Hambly R, Hughes R, et al. Metformin use in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat 2020;31:261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Montero-Vilchez T, Valenzuela-Amigo A, Cuenca-Barrales C, et al. The role of oral contraceptive pills in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cohort study. Life 2021;11:697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Patel N, McKenzie SA, Harview CL, et al. Isotretinoin in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat 2021;32:473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang CM, Kirchhof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatology 2017;233:120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andersen RK, Jemec GBE. Treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Dermatol 2017;35:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Anderson MD, Zauli S, Bettoli V, et al. Cyclosporine treatment of severe Hidradenitis suppurativa--A case series. J Dermatolog Treat 2016;27:247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frew JW. The contradictory inefficacy of methotrexate in hidradenitis suppurativa: a need to revise pathogenesis or acknowledge disease heterogeneity? J Dermatolog Treat 2020;31:422–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Savage KT, Brant EG, Rosales Santillan M, et al. Methotrexate shows benefit in a subset of patients with severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Womens Dermatol 2020;6:159–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alhusayen R, Shear NH. Scientific evidence for the use of current traditional systemic therapies in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S42–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leslie KS, Tripathi SV, Nguyen TV, et al. An open-label study of anakinra for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tzanetakou V, Kanni T, Giatrakou S, et al. Safety and efficacy of anakinra in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun NZ, Ro T, Jolly P, et al. Non-response to interleukin-1 antagonist canakinumab in two patients with refractory pyoderma gangrenosum and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2017;10:36–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Houriet C, Seyed Jafari SM, Thomi R, et al. Canakinumab for severe hidradenitis suppurativa: preliminary experience in 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:1195–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Prens LM, Bouwman K, Aarts P, et al. Adalimumab and infliximab survival in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a daily practice cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2021;185:177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Benassaia E, Bouaziz JD, Jachiet M, et al. Serum infliximab levels and clinical response in hidradenitis suppurativa. JEADV Clinical Practice 2023;2:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther 2022;35:e15691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Rappard DC, Limpens J, Mekkes JR. The off-label treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa with TNF-α inhibitors: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat 2013;24:392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glatt S, Jemec GBE, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of bimekizumab in moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2021;157:1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Casseres RG, Kahn JS, Her MJ, et al. Guselkumab in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81:265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kovacs M, Podda M. Guselkumab in the treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:e140–e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kimball AB, Prens EP, Passeron T, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Ther 2023;13:1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Repetto F, Burzi L, Ribero S, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case series. Acta Derm Venereol 2022;102:adv00780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Blok JL, Li K, Brodmerkel C, et al. Ustekinumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical results and a search for potential biomarkers in serum. Br J Dermatol 2016;174:839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vossen ARJV, van Doorn MBA, van der Zee HH, et al. Apremilast for moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alavi A, Hamzavi I, Brown K, et al. Janus kinase 1 inhibitor INCB054707 for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two phase II studies. Br J Dermatol 2022;186:803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Takahashi K, Yanagi T, Kitamura S, et al. Successful treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with rituximab for a patient with idiopathic carpotarsal osteolysis and chronic active antibody-mediated rejection. J Dermatol 2018;45:e116–e117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Seigel K, Croitoru D, Lena ER, et al. Utility of rituximab in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg 2023;27:176–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Danby FW, Hazen PG, Boer J. New and traditional surgical approaches to hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S62–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shih T, Lee K, Seivright JR, et al. Hyperhidrosis treatments in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther 2022;35:e15210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Matusiak Ł, Szczęch J, Kaaz K, et al. Clinical characteristics of pruritus and pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol 2018;98:191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hua VJ, Kuo KY, Cho HG, et al. Hyperhidrosis affects quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa: a prospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:753–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.