Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of cardiovascular risk on the functioning of patients without a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Two hundred patients diagnosed with arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes were enrolled in the study. The median age was 52.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 43.0–60.0). The following risk factors were assessed: blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference, physical activity, smoking, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting plasma glucose concentration. Total cardiovascular risk was determined as the number of uncontrolled risk factors, and with the Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation Score (SCORE). The Functioning in the Chronic Illness Scale (FCIS) was applied to assess the physical and mental functioning of patients.

Results

The median number of measures of cardiovascular risk factors was 4.0 (IQR 3.0–5.0). The median of SCORE for the whole study population was 2.0 (IQR 1.0–3.0). Patients with lower total cardiovascular risk as defined by SCORE and number of uncontrolled risk factors had better functioning as reflected by higher FCIS (R = −0.315, p < 0.0001; R = −0.336, p < 0.0001, respectively). Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified abnormal blood pressure, abnormal waist circumference, tobacco smoking, and lack of regular physical activity to be negative predictors of functioning. Lack of regular physical activity was the only predictor of low FCIS total score (odds ratio 9.26, 95% confidence interval 1.19–71.77, p = 0.03).

Conclusions

The functioning of patients worsens as the total cardiovascular risk increases. Each of the risk factors affects the functioning of subjects without coronary artery disease with different strength, with physical activity being the strongest determinant of patient functioning.

Keywords: cardiovascular risk factors, functioning of patients

Introduction

The occurrence of chronic diseases is a serious social, health, and economic problem in Poland and in other European countries [1, 2]. It has been shown that risk factors such as poor nutrition, obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia increase the incidence of cardiovascular events [1–3]. Undoubtedly, the occurrence of cardiovascular events in the course of a chronic disease affects multiple areas of human functioning, including physical activity, as well as the emotional and spiritual sphere. The limitations in the functioning of patients with chronic disease result in lower self-value perception, deterioration of well-being, and increased anxiety and uncertainty about the future. The degree of interference is largely dependent on the severity of disease symptoms [4, 5]. However, it is unclear whether the mere presence of risk factors in patients who have not yet experienced cardiovascular events affects their functioning.

Therefore, we assessed the impact of cardiovascular risk on the comprehensive functioning of patients without a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) enrolled into the Polish arm of the EUROASPIRE V study.

Methods

The EUROASPIRE V study is a multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional observational trial carried out in 2016–2018 in 16 European countries to determine whether the 2016 Joint European Societies’ guidelines on CVD prevention in people at high cardiovascular risk have been implemented in clinical practice. The Polish arm of the EUROASPIRE V study included 200 adults (aged 18–80 years) diagnosed with arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes within 6 to 24 months before enrolment to the study. Patients with a previous cardiovascular event were excluded from the study. Consecutive patients were identified on the basis of medical records in participating healthcare centers and were invited personally to participate in the study. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the study. The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz (KB 586/2017). The assessment of study participants was carried out by a trained person — a nurse or a doctor during the study visit. Following the EUROASPIRE V protocol, all patients were assessed on eight different measures of risk factors: arterial blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, physical activity, tobacco smoking status, serum total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides (TG) concentration, and fasting plasma glucose.

Blood pressure was measured twice on the right shoulder in a sitting position, with the use of validated semiautomatic sphygmomanometers. The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria were applied for the diagnosis and classification of hypertension [6].

The following anthropometric measurements were taken: height (cm), weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2), and waist circumference (cm).

In order to assess physical activity, the following question was asked: “Which of the following terms best describes your extra-professional activity?”, with four possible answers: 1 — “I do not have any physical activity other than my professional work.”; 2 — “Only light physical activity most of the time.”; 3 — “Intensive physical activity at least 20 minutes 1–2 times a week. ”; and 4 — “20 minutes of vigorous physical activity more than twice a week.” Answers 3 and 4 were considered an adequate level of physical activity.

Patients’ self-declared smoking status was verified with an objective test measuring the concentration of carbon monoxide in the exhaled air, with results of > 10 parts per million (ppm) being considered indicative of active smoking.

Serum LDL-C and TG concentrations, as well as fasting plasma glucose, were measured in fasting venous blood samples on an Alinity ci analyzer (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Appropriate control of the analyzed risk factors was acknowledged when the following criteria were met:

— Blood pressure: systolic BP < 140 mmHg and diastolic BP < 90 mmHg;

— Body weight: BMI of 20.0–24.9 kg/m2;

— Waist circumference: < 80 cm for women and < 94 cm for men;

— Regular physical activity: intensive exercise for 20 minutes or more at least 1–2 times a week;

— Smoking status: self-reported non-smoker status objectively confirmed by the concentration of carbon monoxide in the exhaled air < 10 ppm;

— LDL-C concentration: < 2.6 mmol/L (< 100 mg/dL);

— TG concentration: < 1.7 mmol/L (< 150 mg/dL);

— Fasting plasma glucose: < 100 mg/dL (< 5.6 mmol/L).

Total cardiovascular risk was determined individually for each study participant, as the number of uncontrolled risk factors, and with Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation Score (SCORE) introduced in guidelines of the ESC [3] — a version calibrated for the Polish population [7]. The SCORE model predicts the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in apparently healthy individuals based on gender, age, total cholesterol concentration, systolic BP, and smoking status [3, 7, 8]. The actual total cardiovascular risk was defined as follows: very high (SCORE ≥ 10%); high (SCORE ≥ 5% and < 10%); moderate (SCORE ≥ 1% and < 5%); and low (SCORE < 1%) [9].

We also applied the Functioning in Chronic Illness Scale (FCIS) to assess the physical and mental functioning of each patient. The FCIS is a unique tool developed for comprehensive evaluation of various aspects of patient functioning with chronic disease. It allows the diagnosis of deficit areas in patients and the implementation of appropriate interventions. This scale, consisting of 24 items, is divided into three subscales. The first part of the questionnaire assessing the impact of the disease on the patient (FCIS 1 subscale) mainly refers to the patient’s physical efficiency, quality of life, and acceptance of the disease. The second (FCIS 2 subscale) and third (FCIS 3 subscale) assess the patient’s beliefs regarding the possible impact on the course of illness and the impact of the disease on the patient’s attitudes, respectively. These subscales refer mainly to self-efficacy and the location of health control [10–12]. The FCIS total score < 79 points indicates low functioning, 79–93 points — medium functioning, and > 93 points — high functioning. Respective cut-off points for consecutive FCIS subscales scores were: < 24, 24–33, > 33 (FCIS 1); < 25, 25–29, > 29 (FCIS 2); and < 28, 28–33, > 33 (FCIS 3) [10].

In line with the EUROASPIRE V protocol, a single study visit was performed, comprising a medical interview including SCORE and FCIS evaluation, anthropometric measurements (height, weight, waist circumference), BP measurements, and measurement of blood and exhaled carbon monoxide.

In the next step the impact of total cardiovascular risk on the functioning of patients according to FCIS was evaluated.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica 13.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., California, USA) and MedCalc 15.8 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR), and minimum and maximum value. The Shapiro-Wilk test demonstrated non-normal distribution of the investigated continuous variables. Therefore, non-parametric tests were used for statistical analysis. Comparisons between two groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney unpaired rank sum test. For comparisons between more groups, the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance was used. To assess the relationship between two quantitative variables, Spearman’s rank correlation was used. The optimum cut-off point for the association of FCIS and high cardiovascular risk was determined using receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curve analysis. To identify factors predicting high FCIS total score univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed. The best model was identified using multiple-model backward stepwise regression. The multivariate model was created by including variables with a p value < 0.1 in univariate analysis and subsequently removing one by one those without significant impact (p > 0.05).

Results

Of 200 patients enrolled in the study, 133 (66.5%) were women. The median age of the study population was 52.0 years (IQR 43.0–60.0). The median BP for the entire population was 125.0 mmHg (IQR 118.0–135.0 mmHg) and 77.5 mmHg (IQR 70.0–82.0 mmHg) for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively. The median BMI for the entire study group was 26.0 kg/m2 (IQR 23.9–28.7 kg/m2). The median waist circumference for the entire study group was 87.0 cm (IQR 80.0–95.5 cm). Regular physical activity according to the adopted definition was declared by 41% of the study participants. The median carbon monoxide concentration measured in the exhaled air was 1.0 ppm (IQR 0.0–2.0). Active smokers (n = 30) had a significantly higher carbon monoxide concentration compared with non-smokers (4.5, IQR 2.0–8.0 vs. 1.0, IQR 0.0–1.0; p < 0.001). The level of carbon monoxide did not exceed 10 ppm in any of the patients declaring themselves as non-smokers. Median concentrations of LDL-C, TG, and glucose in the venous blood serum were 3.29 mmol/L (IQR 2.68–4.0), 1.21 mmol/L (IQR 0.90–1.55), and 5.4 mmol/L (IQR 5.04–5.90), respectively. The proportions of patients with risk factors identified according to medical records, medical history, or contemporary performed tests are shown in Table 1. The median number of measures of cardiovascular risk factors was 4.0 (IQR 3.0–5.0). The median SCORE for the whole study population was 2.0 (IQR 1.0–3.0). Measures of total cardiovascular risk are also presented in Table 1. Functioning levels assessed with the FCIS are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| The assessed feature | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (IQR) | 52.0 (43.0–60.0) | |

| Gender | Male | 67 | 33.5 |

| Female | 133 | 66.5 | |

| Arterial hypertension | Diagnosed | 127 | 63.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Diagnosed | 38 | 19.0 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Diagnosed | 90 | 45.0 |

| Tobacco smoking (active) | Declared | 30 | 15.0 |

| Systolic blood pressure | ≥ 140 mmHg | 39 | 19.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ≥ 90 mmHg | 21 | 10.5 |

| Systolic/diastolic blood pressure | ≥ 140 mmHg and/or ≥ 90 mmHg | 45 | 22.5 |

| Body mass index | Underweight | 11 | 5.5 |

| Correct weight | 72 | 36.0 | |

| Overweight | 84 | 42.0 | |

| Obesity | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Waist circumference | Normal fat distribution | 74 | 37.0 |

| Moderate central fat accumulation | 57 | 28.5 | |

| [W ≥ 80 cm, M ≥ 94 cm] | |||

| High central fat accumulation | 69 | 34.5 | |

| [W ≥ 88 cm, M ≥ 102 cm] | |||

| Physical activity | No activity | 30 | 15.0 |

| Low activity | 110 | 55.0 | |

| Regular activity | 60 | 30.0 | |

| Serum LDL-C concentration | ≥ 2.6 mmol/L | 154 | 77.0 |

| Serum TG concentration | ≥ 1.7 mmol/L | 37 | 18.5 |

| Fasting plasma glucose | ≥ 5.56 mmol/L | 83 | 41.5 |

| Number of uncontrolled measures of CV risk factors | 0 | 6 | 3.0 |

| 1 | 10 | 5.0 | |

| 2 | 32 | 16.0 | |

| 3 | 35 | 17.5 | |

| 4 | 52 | 26.0 | |

| 5 | 43 | 21.5 | |

| 6 | 15 | 7.5 | |

| 7 | 5 | 2.5 | |

| 8 | 2 | 1.0 | |

| SCORE | Low: < 1% | 35 | 17.5 |

| Moderate: ≥ 1%; < 5% | 131 | 65.5 | |

| High: ≥ 5%; < 10% | 16 | 8.0 | |

| Very high: ≥ 10% | 18 | 9.0 | |

| FCIS total score | High score | 129 | 64.5 |

| Medium score | 51 | 25.5 | |

| Low score | 20 | 10.0 | |

| FCIS 1 score | High score | 126 | 63.0 |

| Medium score | 60 | 30.0 | |

| Low score | 14 | 7.0 | |

| FCIS 2 score | High score | 106 | 53.0 |

| Medium score | 71 | 35.5 | |

| Low score | 23 | 11.5 | |

| FCIS 3 score | High score | 103 | 51.5 |

| Medium score | 70 | 35.0 | |

| Low score | 27 | 13.5 | |

IQR — interquartile range; CV — cardiovascular; LDL-C — low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG — triglycerides; W — women; M — men

Table 2.

Results of the Functioning in Chronic Illness Scale (FCIS)

| FCIS | N | Median | Quartile 1 | Quartile 3 | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCIS total score | 200 | 98.50 | 91.00 | 109.00 | 59.00 | 120.00 |

| FCIS 1 score | 200 | 36.50 | 31.00 | 39.50 | 12.00 | 40.00 |

| FCIS 2 score | 200 | 30.00 | 27.00 | 35.00 | 19.00 | 40.00 |

| FCIS 3 score | 200 | 34.00 | 31.00 | 38.00 | 16.00 | 40.00 |

Mean and median values of the FCIS total score and each subscale reflected a high functioning level (Table 2).

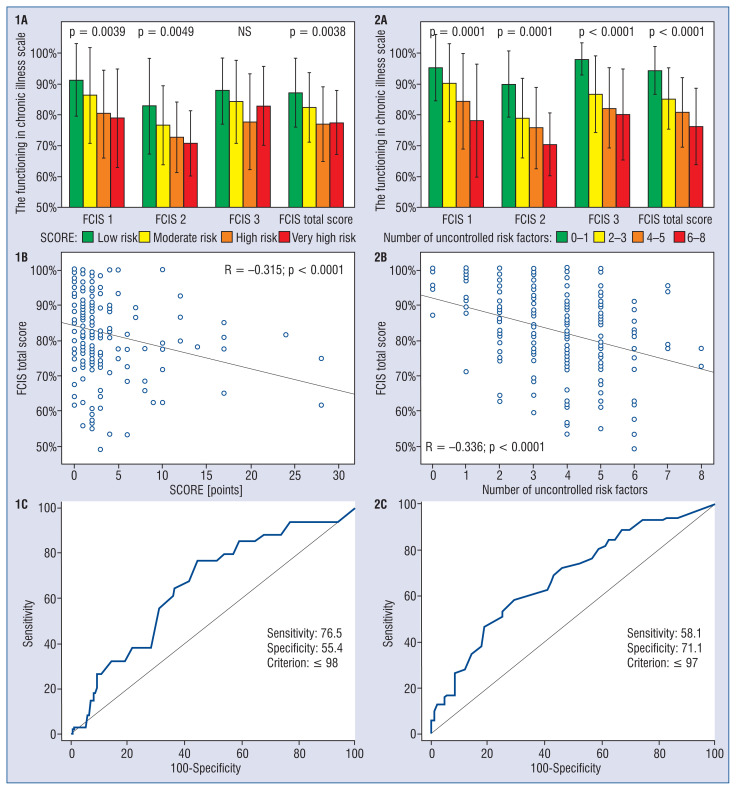

Patients with lower SCORE-defined total cardiovascular risk had better functioning in disease as reflected by higher FCIS total, FCIS 1, and FCIS 2, but not FCIS 3 scores (Fig. 1, 1A). The Spearman correlation between FCIS 1, 2, and 3 scores and SCORE was −0.323, p < 0.0001; −0.273, p = 0.0001; and −0.197, p = 0.005, respectively (Fig. 1, 1B). The ROC analysis (area under curve [AUC] 0.658; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.588–0.724; p = 0.0016) revealed that patients with FCIS total score ≤ 98 are of high or very high cardiovascular risk according to SCORE, with sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity of 55.4% (Fig. 1, 1C).

Figure 1.

Functioning of patients in relation to cardiovascular risk stratified according to the SCORE and the number of uncontrolled risk factors; A. Functioning of patients according to the FCIS (subscales and total score) in a subset of patients with increasing total cardiovascular risk assessed with the SCORE (1A), expressed as the number of uncontrolled risk factors (2A); B. Spearman correlation between FCIS total score and the SCORE (1B), and the number of uncontrolled risk factors (2B); C. Discrimination of FCIS score threshold indicating patients with high or very high cardiovascular risk according to the SCORE (1C) and to the number of uncontrolled risk factors (2C)

In general, these results were confirmed when total cardiovascular risk was calculated as the number of uncontrolled risk factors; however, in this case the effect of total cardiovascular risk was more pronounced and significant for all FCIS subscales (Fig. 1, 2A). Spearman correlation between FCIS 1, 2, and 3 scores and the number of uncontrolled risk factors was −0.339, p < 0.0001; −0.245, p < 0.0005; and −0.289, p < 0.0001, respectively (Fig. 1, 2B). According to the ROC analysis (AUC 0.679; 95% CI 0.610–0.743; p < 0.0001), patients with an FCIS total score ≤ 97 are of high or very high cardiovascular risk as evaluated according to the number of uncontrolled risk factors, with a sensitivity of 58.1% and a specificity of 71.1% (Fig. 1, 2C).

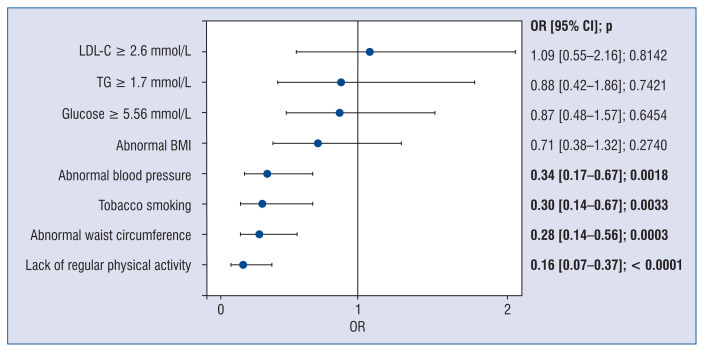

Figure 2.

Impact of single risk factors on the occurrence of high FCIS total score. Univariate regression analysis; OR — odds ratio; CI — confidence interval; LDL-C — low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG — triglycerides; BMI — body mass index

Univariate logistic regression analysis identified abnormal BP (p = 0.002), abnormal waist circumference (p = 0.0003), tobacco smoking (p = 0.003), and lack of regular physical activity to be negative predictors of high FCIS total score (Fig. 2). These findings were confirmed in multivariate regression analysis (Table 3). For low FCIS total score, the univariate logistic regression analysis identified only a single predictor — the lack of regular physical activity (odds ratio 9.26, 95% CI 1.19–71.77, p = 0.03); therefore, the multivariate logistic regression analysis was abandoned.

Table 3.

Predictors of high FCIS total score — multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal blood pressure | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.0485 |

| Abnormal waist circumference | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.76 | 0.0069 |

| Tobacco smoking | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 0.0243 |

| Lack of regular physical activity | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.0003 |

Discussion

Coronary artery disease (CAD) affects multiple aspects of patients’ lives in many ways, including physical activity, emotional and spiritual spheres, and social functioning. Limited functioning of a patient with chronic disease results in decreased self-esteem, deteriorated well-being, increased anxiety, and uncertainty about the future [13–16]. Numerous studies [17–34] indicate the need for the combined use of various tools for the overall assessment of various aspects of the functioning of subjects with chronic disease. The tools previously developed to diagnose overall functioning of patients, e.g., WHO-DAS II scale and CIA questionnaire, are dedicated to very specific clinical situations, such as low back pain [17, 18] or nutrition disorders [19, 20]. The FCIS is a unique validated tool allowing the comprehensive assessment of physical and mental functioning dedicated to patients with chronic diseases. The first FCIS subscale mainly refers to the patient’s physical efficiency, quality of life, and acceptance of the disease. These aspects of patient functioning were previously evaluated in numerous studies in different clinical settings with several different tools [21–29]. The second and third FCIS subscales refer mainly to the self-efficacy and the location of health control. These aspects were assessed separately with other tools [30–34].

According to our best knowledge, this study is the first to show that the risk factors themselves affect the comprehensive functioning of patients without diagnosed CAD. The increase in total cardiovascular risk determined with the SCORE or expressed by the number of uncontrolled risk factors results in deterioration of functioning of patients as assessed with the FCIS. The scores in the FCIS subscales are generally consistent with each other, with the exception of FCIS 3 reflecting the location of health control, with regard to the SCORE scores. We have also demonstrated that an FCIS total score of 97–98 points is the cut-off for high and very high cardiovascular risk irrespective of whether it is assessed with the SCORE or the number of uncontrolled risk factors. The FCIS questionnaire was previously applied in patients with CAD [35] and in subjects with post-COVID syndrome [36]. The FCIS is currently being used in the ELECTRA-SIRIO2 study — an ongoing large-scale clinical trial scheduled to enroll a total of 4500 acute coronary syndrome patients [37, 38]. The proportion of patients with high FCIS score in our current study (64.5%) is noticeably higher than in our previous studies with CAD patients (31%) [35] and post-COVID patients (30%) [36]. We have shown that lack of regular physical activity (the strongest factor), tobacco smoking, abdominal obesity, and increased BP deteriorate the functioning of patients. Conversely, laboratory cardiovascular risk factors such as increased concentrations of LDL-C, TG, and glucose do not affect the FCIS score in multivariate regression analysis. In line with our study, Spinka et al. [39] found physical activity to be strongly correlated with the functioning and quality of life of CAD patients. Aerobic interval training as well as aerobic continuous training were shown to improve peripheral endothelial function, cardiovascular risk factors, and the quality of life [40]. Moreover, in subjects with normal coronaries, treatment of endothelial dysfunction, reflecting the cardiovascular risk and favorably influencing the quality of life [41]. We have shown increased waist circumference, but not increased BMI, to have a deteriorating impact on patient functioning. On the other hand, Oreopoulos et al. [42] revealed BMI to be inversely associated with the physical functioning and overall health-related quality of life in CAD patients, especially in individuals with severe obesity. Because the assessment of the quality of life is part of the evaluation of functioning in chronic illness, the results of the cited studies [39–42] should be considered generally consistent with our observations.

Limitations of the study

The limitation of our study is the relatively low number of enrolled patients. Moreover, the lack of follow-up did not allow for assessment of the influence of the examined risk factors on clinical outcome.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the functioning of patients worsens as the total cardiovascular risk increases. Each of the risk factors affects the functioning of subjects without CAD with different strength, with physical activity being the strongest determinant of patient functioning.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, et al. Primary prevention efforts are poorly developed in people at high cardiovascular risk: A report from the European Society of Cardiology EURObservational Research Programme EUROASPIRE V survey in 16 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28(4):370–379. doi: 10.1177/2047487320908698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SCORE2 working group and ESC Cardiovascular risk collaboration. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(25):2439–2454. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy R. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(11):987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchmanowicz I, Lisiak M, Wleklik M, et al. The relationship between frailty syndrome and quality of life in older patients following acute coronary syndrome. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:805–816. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S204121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lourenço E, Sampaio MR, Nzwalo H, et al. Determinants of quality of life after stroke in Southern Portugal: a cross sectional community-based study. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11):1509. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11111509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zdrojewski T, Jankowski P, Bandosz P, et al. [A new version of cardiovascular risk assessment system and risk charts calibrated for Polish population]. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73(10):958–961. doi: 10.5603/KP.2015.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomasik T, Krzysztoń J, Dubas-Jakóbczyk K, et al. The systematic coronary risk evaluation (SCORE) for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Does evidence exist for its effectiveness? A systematic review. Acta Cardiol. 2017;72(4):370–379. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2017.1335052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano A, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2019;41(1):111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buszko K, Pietrzykowski Ł, Michalski P, et al. Validation of the Functioning in Chronic Illness Scale (FCIS) Med Res J. 2018;3(2):63–69. doi: 10.5603/mrj.2018.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubica A. Self-reported questionnaires for a comprehensive assessment of patients after acute coronary syndrome. Med Res J. 2019;4(2):106–109. doi: 10.5603/mrj.a2019.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubica A, Bączkowska A. Rationale for motivational interventions as pivotal element of multilevel educational and motivational project MEDMOTION. Folia Cardiologica. 2020;15(1):6–10. doi: 10.5603/fc.2020.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkes AL, Patrao TA, Ware R, et al. Predictors of physical and mental health-related quality of life outcomes among myocardial infarction patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, Ahmadi K. Comorbidity influences multiple aspects of well-being of patients with ischemic heart disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2013;7(4):118–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lalonde L, Clarke AE, Joseph L, et al. Health-related quality of life with coronary heart disease prevention and treatment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olano-Lizarraga M, Oroviogoicoechea C, Errasti-Ibarrondo B, et al. The personal experience of living with chronic heart failure: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(17–18):2413–2429. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Røe C, Sveen U, Bautz-Holter E. Retaining the patient perspective in the international classification of functioning, disability and health core set for low back pain. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008;2:337–347. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garin O, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Almansa J, et al. Validation of the „World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2” in patients with chronic diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, et al. The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(10):1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohn K. Clinical Impairment Assessment Questionnaire (CIA) Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders. Springer; Singapore: 2017. pp. 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson P, Tam SW, Ghali JK, et al. Relationship of quality of life scores with baseline characteristics and outcomes in the African-American heart failure trial. J Card Fail. 2009;15(10):835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87(3):235–241. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurpas D, Mroczek B, Knap-Czechowska H, et al. Quality of life and acceptance of illness among patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;187(1):114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankowska-Polańska B, Kaczan A, Lomper K, et al. Symptoms, acceptance of illness and health-related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(3):262–272. doi: 10.1177/1474515117733731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewko J, Polityńska B, Kochanowicz J, et al. Quality of life and its relationship to the degree of illness acceptance in patients with diabetes and peripheral diabetic neuropathy. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52(Suppl 1):144–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benetos A, Gautier S, Labat C, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular events are best predicted by low central/peripheral pulse pressure amplification but not by high blood pressure levels in elderly nursing home subjects: the PARTAGE (Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1503–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedrosa H, De Sa A, Guerreiro M, et al. Functional evaluation distinguishes MCI patients from healthy elderly people — the ADCS/MCI/ADL scale. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(8):703–709. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oris L, Luyckx K, Rassart J, et al. Illness identity in adults with a chronic illness. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(4):429–440. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sengul Y, Kara B, Arda MN. The relationship between health locus of control and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Turk Neurosurg. 2010;20(2):180–185. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.2616-09.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wielenga-Boiten JE, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Ribbers GM. The relationship of health locus of control and health-related quality of life in the chronic phase after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(6):424–431. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramm JM, Strating MMH, Roebroeck ME, et al. The importance of general self-efficacy for the quality of life of adolescents with chronic conditions. Soc Indic Res. 2013;113(1):551–561. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0110-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda U, Shen BJ, Schwarz ER, et al. Self-efficacy mediates the associations of social support and depression with treatment adherence in heart failure patients. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(1):88–96. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moljord IE, Lara-Cabrera ML, Perestelo-Pérez L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure-13 among out-patients waiting for mental health treatment: A validation study in Norway. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(11):1410–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michalski P, Kasprzak M, Kosobucka A, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical determinants of the functioning of patients with coronary artery disease. Med Res J. 2021;6(1):21–27. doi: 10.5603/mrj.a2021.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubica A, Michalski P, Kasprzak M, et al. Functioning of patients with post-COVID syndrome — preliminary data. Med Res J. 2021;6(3):224–229. doi: 10.5603/mrj.a2021.0044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubica A, Adamski P, Bączkowska A, et al. The rationale for Multilevel Educational and Motivational Intervention in Patients after Myocardial Infarction (MEDMOTION) project is to support multicentre randomized clinical trial Evaluating Safety and Efficacy of Two Ticagrelor-based De-escalation Antiplatelet Strategies in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELECTRA – SIRIO 2) Med Res J. 2020;5(4):244–249. doi: 10.5603/mrj.a2020.0043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubica J, Adamski P, Gorog DA, et al. Low-dose ticagrelor with or without acetylsalicylic acid in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Rationale and design of the ELECTRA-SIRIO 2 trial. Cardiol J. 2022;29(1):148–153. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2021.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinka F, Aichinger J, Wallner E, et al. Functional status and life satisfaction of patients with stable angina pectoris in Austria. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e029661. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pattyn N, Vanhees L, Cornelissen VA, et al. The long-term effects of a randomized trial comparing aerobic interval versus continuous training in coronary artery disease patients: 1-year data from the SAINTEX-CAD study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(11):1154–1164. doi: 10.1177/2047487316631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reriani M, Flammer AJ, Duhé J, et al. Coronary endothelial function testing may improve long-term quality of life in subjects with microvascular coronary endothelial dysfunction. Open Heart. 2019;6(1):e000870. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, McAlister FA, et al. Association between obesity and health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34(9):1434–1441. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]