Highlights

-

•

The protein E7 from high-risk HPV is phosphorylated by the protein kinase CK2 to a greater degree compared to low-risk HPV, which could be a contributing factor to the oncogenic properties of high-risk HPV.

-

•

The presence of valine residues in the CK2 recognition sequence of E7 are prevalent in the most clinically relevant low-risk serotypes of HPV.

-

•

Using site directed mutagenesis, two valine residues were introduced in high-risk E7 to mimic the CK2 recognition domain of low-risk E7. This slight modification was adequate to significantly modify the rate of phosphorylation for high-risk E7 as determined by NMR.

-

•

In two different cell model systems the presence of the two valine residues in the CK2 recognition sequence of high-risk E7 resulted in decreased levels of degradation of the retinoblastoma protein.

-

•

In primary cervical cells the proliferative advantage and extended lifespans of high-risk E7 were mitigated by modifying the CK2 binding domain with the addition of the two valines to mimic E7 from low-risk HPV.

Key Words: Post-translational modification, Oncogenic Virus, pRb degradation, NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance), Intrinsically disordered protein

Abstract

The Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes tumors in part by hijacking the host cell cycle and forcing uncontrolled cellular division. While there are >200 genotypes of HPV, 15 are classified as high-risk and have been shown to transform infected cells and contribute to tumor formation. The remaining low-risk genotypes are not considered oncogenic and result in benign skin lesions. In high-risk HPV, the oncoprotein E7 contributes to the dysregulation of cell cycle regulatory mechanisms. High-risk E7 is phosphorylated in cells at two conserved serine residues by Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) and this phosphorylation event increases binding affinity for cellular proteins such as the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (pRb). While low-risk E7 possesses similar serine residues, it is phosphorylated to a lesser degree in cells and has decreased binding capabilities. When E7 binding affinity is decreased, it is less able to facilitate complex interactions between proteins and therefore has less capability to dysregulate the cell cycle. By comparing E7 protein sequences from both low- and high-risk HPV variants and using site-directed mutagenesis combined with NMR spectroscopy and cell-based assays, we demonstrate that the presence of two key nonpolar valine residues within the CK2 recognition sequence, present in low-risk E7, reduces serine phosphorylation efficiency relative to high-risk E7. This results in significant loss of the ability of E7 to degrade the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein, thus also reducing the ability of E7 to increase cellular proliferation and reduce senescence. This provides additional insight into the differential E7-mediated outcomes when cells are infected with high-risk verses low-risk HPV. Understanding these oncogenic differences may be important to developing targeted treatment options for HPV-induced cancers.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The double stranded DNA Human Papillomavirus (HPV) contains >200 genotypes and is among the most common sexually transmitted infections, with skin-to-skin contact sufficient for virus transmission (Burd, 2003; Fathi and Tsoukas, 2014; Petca et al., 2020). While most of these genotypes are classified as low-risk, resulting in transient, benign skin lesions, at least 15 are classified as high-risk and have been shown to significantly affect regulation of the cell cycle, thus transforming infected cells and contributing to their development into tumor cells (de Villiers et al., 2004; Manini and Montomoli, 2018; McBride, 2017). These high-risk genotypes are ultimately responsible for virtually all instances of cervical cancer, an increasing number of oropharyngeal cancers, as well as several anogenital cancers, some of which remain difficult to detect and diagnose in routine screening (Szymonowicz and Chen, 2020).

The cellular transforming capabilities of high-risk HPV are initiated through two major oncoproteins, E6 and E7. These proteins work synergistically to block apoptosis and initiate cell division by stimulating rapid progression through the cell cycle, ultimately resulting in tumor formation (Ganguly and Parihar, 2009; McLaughlin-Drubin and Munger, 2009; Munger et al., 1989). E7 is best known for its interaction with the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and has also been shown to interact with other members of the family of pocket proteins, such as p130 and p107 (Berezutskaya et al., 1997; Chemes et al., 2010; Gandhi et al., 2021; Roman and Munger, 2013). The retinoblastoma protein normally binds to the S-phase promoting transcription factor E2F, thus inhibiting activity until proper mitogen signaling results in its release. However, E7 binding with pRb displaces E2F initiating the start of S phase independent of cell cycle regulation. Furthermore, E7 can target pRb for degradation thus resulting in continuous E2F activity and the potential for increased cell replication (Heck et al., 1992; Helt and Galloway, 2003; Jones et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2006). While this interaction is not directly responsible for tumor formation, the displacement of E2F and subsequent degradation of pRb is among the first steps in a series of alterations to normal cell cycle progression, which can ultimately lead to cancer (Ci et al., 2020; Wilting and Steenbergen, 2016). Additionally, high-risk E7 has been shown to bind multiple targets causing a myriad of cellular functions, some of which require the formation of ternary complexes with E7 acting as a bridge between cellular proteins (Jansma et al., 2014; Songock et al., 2017). For this to occur, it is crucial that high-risk E7 be able to rapidly bind and maintain interaction with sufficient affinity to not only elicit a cellular response, but to also recruit additional binding partners. While E7 from low-risk genotypes has been shown to interact with a subset of cellular binding partners such as pRb, the individual interactions have been observed to have lower affinity (Heck et al., 1992; Jansma et al., 2014; Gage et al., 1990). This affinity difference would have an additive affect for functions requiring ternary complexes, which in part may help to explain why low-risk HPV genotypes fail to manipulate the cell cycle to the point of tumor formation. The mechanism behind this differential affinity is complex and not entirely clear. From a sequential perspective, E7 from the most prevalent high-risk genotype HPV16 and E7 from the low-risk genotype HPV6b are approximately 70 % conserved, as indicated by Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of the E7 protein sequences for the most prevalent high-risk (HPV16) and low-risk (HPV6b) genotypes, indicating the three conserved regions (CR1, CR2, and CR3) with identical (*) and homologous (:) residues labeled. The LxCxE regions are highlighted in purple, and the Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) recognition sequences are shown within the box. Within the CK2 recognition sequence, the conserved phosphoacceptor serine residues are highlighted in blue, acidic residues are shown in red and hydrophobic residues are depicted in green. The polar asparagine residue at position 29 is highlighted in orange.

Both high-risk and low-risk E7 contain three conserved regions denoted CR1, CR2 and CR3. Structures of E7 for several different genotypes of HPV have been solved and show that both the high-risk and low-risk proteins form a homodimer through the structured CR3 zinc-finger domain, while the other half of the protein containing CR1 and CR2 is intrinsically disordered (Ohlenschlager et al., 2006; Risor et al., 2021; Uversky et al., 2006; Yun et al., 2019). Binding to pRb occurs primarily through the interaction domain known as the LxCxE motif in CR2 (Fig. 1, purple) and this region is highly conserved across all genotypes of HPV, regardless of risk category (Garcia-Alai et al., 2007; Lee et al., 1998; Todorovic et al., 2011). While previous work has shown that low-risk E7 binds pRb to a lesser extent, the details behind this observation remain under speculation since all low-risk forms of E7 contain the LxCxE sequence, suggesting that the differences in binding affinity must be accounted for by residues outside this critical binding site (Heck et al., 1992).

Additionally, E7 is phosphorylated by cellular Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) at two highly conserved serine residues located in the CR2 domain (Fig. 1, blue) and this phosphorylation has been shown to be crucial for inducing optimal cellular transformation (Basukala et al., 2019; Nogueira et al., 2017). The removal of both serine residues in E7 from HPV16 for example, resulted in significantly decreased cellular transforming capability, while blocking the phosphoacceptor domain was shown to decrease interaction with pRb (Basukala et al., 2022; Ramon et al., 2022). Furthermore, the presence of a natural variant of HPV16 was found to have an additional serine substituted at position 29, sufficiently close to the native serine residues to be phosphorylated by CK2 (Fig. 1, orange). This triple phosphorylated variant demonstrated increased transformation capabilities in the infected patient and resulted in aggressive tumor progression (Zine El Abidine et al., 2017). As is the case with many intrinsically disordered proteins, the arrangement of charged amino acid residues combined with post-translational modifications creates a complex system, making it difficult to credit the functional differences between high-and low-risk E7 to any one specific thing (Bah and Forman-Kay, 2016; Bianchi et al., 2022; Newcombe et al., 2022). Thus, the correlation between phosphorylation and the ability of high-risk E7 to aid in transforming cells is unclear, especially since E7 from low-risk genotypes of HPV also possess homologous serine residues which are capable of phosphorylation by CK2. However, these low-risk forms of E7 appear to be phosphorylated to a lesser degree when observed in cells (Munger et al., 1989; Barbosa et al., 1990; Sang and Barbosa, 1992). This suggests that the extent and efficiency of E7 phosphorylation by CK2 may play a role in mediating these oncogenic risk properties.

CK2 itself is an acidophilic serine/threonine kinase that phosphorylates substrates involved in multiple biological processes, including both cell proliferation and apoptosis (Vilk et al., 2008). Previous work has demonstrated that the most crucial element for substrate recognition is an acidic residue at the +3 position from the phosphoacceptor serine, but additional acidic residues at positions −2 to +7 also aid in enzyme recognition and efficient phosphorylation (Meggio et al., 1994). At the same time, basic or bulky hydrophobic residues in positions +1 and +2 have been shown previously to be powerful negative determinants to phosphorylation by CK2 (Meggio et al., 1994). The alignment in Fig. 1 shows that the CK2 recognition sequence of E7 from the low-risk HPV6b contains two valine residues at positions −2 and +4 relative to the substrate serine residues, while E7 from HPV16 shows uninterrupted polar/acidic residues spanning the same region (green and red respectively). In this paper, we highlight the increased presence of hydrophobic residues in E7 from low-risk HPV genotypes, particularly in regions within the disordered domain. We also demonstrate the functional importance of valine residues neighboring the serine phosphoacceptor sites within the CK2 recognition site in reducing phosphorylation efficiency of E7. This loss of phosphorylation efficiency reduces E7’s ability to degrade the retinoblastoma protein and in turn inhibits its ability to increase cellular proliferation. While this specific region surrounding the phosphoacceptor serines has not been directly attributed to the function of E7, here we demonstrate that these key valine residues have the potential to significantly decrease the oncogenic capabilities of high-risk E7 within cells. Together, our data contributes to the understanding of key differences between high- and low-risk genotypes. This understanding could help to broaden the identification of factors that may aid in screening for high-risk HPV genotypes following infection, recognize additional critical sequences for which to screen, and to develop novel therapeutic targets to prevent or slow HPV-induced cancers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Recombinant protein expression of synthetic peptides for NMR studies

The E7 sequences correspond to the human papillomavirus strain HPV16. All of the disordered domains were expressed at His6-GB1 fusions, including E7(1–51), E7(1–51)N29S, E7(1–51)N29V, E7(1–51)+36 V and E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V, as previously described (Jansma et al., 2014). All constructs were expressed for 16–20 h at approximately 20 °C in BL21DE3 cells. All samples were uniformly 15N isotopically labeled by growth in M9 medium supplemented with 1 g/L (15NH4)2SO4. After growth at 37 °C to OD600 ∼0.8, cells were induced by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. The growth medium was supplemented with 150 μM ZnSO4 as previously described (Jansma et al., 2014). The peptides were initially resuspended in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0 for purification.

2.2. Site Directed Mutagenesis

All point mutations for the disordered domain of E7(1–51), N29S, N29V, +36 V and N29V/+36 V, were made using a QuikChange II Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, 200,523). Primers were designed using the Primer Design tool provided by Agilent Technologies.

2.3. Protein purification

E7(1–51) constructs were purified as previously described (Jansma et al., 2014). Purified peptides were lyophilized and resuspended in approximately 100 μL of 1x NEBuffer for protein kinases (NEB, B6022SVIAL).

2.4. Phosphorylation efficiency assay

CK2 was purchased commercially through New England Biolabs (P6010S), 500,000 units/mL. Each batch of CK2 was tested against E7(1–51) and compared with previously quantitated samples to ensure consistent enzyme activity for all E7 constructs. The pH of the resuspended protein samples was confirmed to be at 7.5 for each construct before proceeding with the assay. Each assay had a total of 250 – 300 μL volume and contained the following: PK buffer at 1x concentration (NEBuffer for Protein Kinases, PK, B6022S), E7 construct at approximately 1.5 mM, ATP at a 10:1 mole ratio of ATP:Protein, CK2 at a ratio of 6.9:1 unit CK2/μmol protein, water to dilute to the final volume. The reaction was run at 30 °C and time points were taken every hour. Each time point was immediately diluted with NMR buffer to a protein concentration of 100 μM (25 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 % (v/v) D2O, pH 6.8) and frozen at −20 °C. The phosphorylation reaction does not run at pH 6.8 so dilution in NMR buffer effectively quenches the phosphorylation reaction and time points are able to be stored at −20 °C for extended periods of time. This was tested by running duplicate samples several days apart to verify that the reaction did not proceed in NMR buffer conditions. Duplicate samples were also frozen and thawed multiple times to confirm that samples could be frozen at a specific time point in the reaction and NMR data could be collected at another time once the sample was defrosted.

2.5. NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were conducted at 30 °C on various Bruker spectrometers (Avance 600 MHz and Avance 800 MHz equipped with croyprobes). 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra were processed and analyzed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995) and NMRView (Johnson and Blevins, 1994). Backbone assignments had been conducted previously and referenced for all samples to confirm the identity of the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated serine residues (Jansma et al., 2014).

2.6. Viral plasmid constructs

Both the high-risk HPV16 full length E7 plasmid (Addgene plasmid #52,396; http://n2t.net/addgene:52396; RRID:Addgene_52,396), and the low-risk HPV6b full length E7 plasmid (Addgene plasmid #52,398; http://n2t.net/addgene:52398; RRID:Addgene_52,398), had been subcloned into the MMLV based retrovirus and were gifts from Denise Galloway (Halbert et al., 1991). The additional constructs were made using the high-risk HPV16 E7 plasmid (pLXSN16E7) in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent QuikChange II kit). The first construct obtained was the ultra-competent N29S construct, in which an asparagine (N) at position 29 was changed to a serine (S) by mutating its codon from AAT to AGT. The double mutant (DM) construct required a two-step process. The first mutation also targeted N29 but altered the asparagine to a valine (N29V) by mutating the codon to GTT. The second mutation was an insertion of a valine at position 36 (+35V36). Constructs were transformed into competent cells, plasmids were purified and confirmed by sequencing.

2.7. Cell culture

BJ cells (ATCC, CRL-2522), a human foreskin fibroblast cell line, and HT-1080 cells (ATCC, CCL-121) a human epithelial fibrosarcoma line, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were maintained in media consisting of Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, ATCC) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and antibiotic-antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15,230,062). Cell passaging was limited to passage 12 for analyses. HCxECs, primary human cervical epithelial cells (ATCC, PCS-480–011) were obtained from ATCC and maintained in cervical epithelial cell basal medium (ATCC, PCS-480–032) supplemented with the cervical epithelial growth kit (ATCC, PCS-4,800,942).

2.8. Establishment of stable cell lines expressing HPV E7 variants

The viral constructs, pLXSN (vector alone), pLXSN—HPV6b E7 (low-risk), pLXSN—HPV16 E7 (high-risk), pLXSN—HPV16 E7 N29S (ultra-competent), pLXSN—HPV16 E7 DM (N29V, +36 V) were used to generate the MMLV-retroviral particles (VectorBuilder). BJ, HT-1080 or HCxECs cells were exposed to an appropriate amount of retrovirus (using an MOI of 2.5) and were subsequently selected using G418, either 300 ug/mL for the BJ cells, 400 ug/mL for the HT-1080 cells, or 50 ug/mL for the HCxECs. Selective pressure was maintained on the cells and regular media changes occurred every 2–3 days while cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5 % CO2 incubator.

2.9. Western blot analysis

Both BJ cells and HT-1080 cells stably expressing the control plasmids or the E7 variants were grown in T-75 flasks. Once 90 % confluent, the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science, 11,836,170,001). Protein concentrations of the lysates were determined with the Pierce BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #23,227) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. 14.5 micrograms of total protein were loaded onto a BOLT 4–12 % Bis-Tris Plus gel (Invitrogen, NW04125) followed by electrophoresis and transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, LC2002). Anti-Rb monoclonal antibodies (Abcam: ab181616) were used at 1:500 dilution followed with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma Aldrich, A-6667) at a 1:10,000 dilution. Anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibodies (Invitrogen, MA5–15,738) were used at a 1:2500 dilution followed with HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Millipore, 12–349) at a 1:2000 dilution. Anti-E7 monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6981) were used at a 1:100 dilution with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Millipore, 12–349) at a 1:2000 dilution. For E7 analysis, 20 ug of protein lysate was loaded for each sample onto the BOLT 4–12 % Bis-Tris gel. Signal was detected using ECL reagent (Super Signal West Pico Plus Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1,863,094).

2.10. Cell proliferation assays

Each transgenic cervical cell line was plated onto 4-well chamber slides at an equivalent density and grown for two days to allow the cells to reach a maximal growth rate prior to testing for cell proliferation using the EdU assay. Alexa 488 was coupled with incorporated EdU by Click-iT chemistry using the Click-iT Plus Imaging Kit (ThermoFisher #C10637) according to the manufacturer's protocol with a 2-hour pulse for EdU incorporation. The human cervical epithelial cells stably expressing the E7 variants were counterstained with 33,342 Hoechst at 5 mg/mL for 30 min. Multiple trials were performed with multiple chamber slide wells for each group (minimum number of replicates = 6). A Leica STELLARIS 5 Confocal microscope was used to image the EdU assay cells. Random areas within each well were imaged, with consistent areas from different wells used to minimize bias. 4 × 4 tiled areas at 100X total magnification were used to generate larger, representative areas for quantification. Imaging parameters were set to maximize imaging and contrast for the Hoechst (blue) and the EdU (green) in order to quantify the percentage of cells that were proliferating. ImageJ was used to count the number of EdU-incorporated dividing cells (green fluorescence) and the total number of cells (Hoechst-staining) to determine the percentage of proliferating cells (# of EdU positive cells / total number of Hoechst nuclei). ANOVA and Tukey's analyses were used to determine significance.

2.11. Quantitative PCR analysis

Both BJ cells and HT-1080 cells stably expressing the control plasmids or the E7 variants were grown in T-75 flasks, while the primary cervical stable cell lines were grown in T-25 flasks. Once 90 % confluent, total RNA was extracted using the Quick-RNA Microprep Kit (Zymo Research, R1050). 5 ug of total RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript IV First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, 18,091,050). Individual PCR reactions of 20 uL total volume contained 10 ng of cDNA, 10 µl of SYBR Green Super mix (BioRad, 1,725,271) and primers (IDT, 1 µM final concentration). Two sets of primers were used to specifically distinguish between low-risk E7 expression and high-risk E7 expression (Table 1). GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene for normalization (IDT, PrimeTime qPCR Primers, Hs.PT.39a.22214836). Each sample was run in triplicate. PCR was carried out using the BioRad CFX Connect Real-Time System for 40 cycles of amplification.

Table 1.

Primer and probe sequences for real-time PCR assays.

| Target | Encoded protein | Primersa |

|---|---|---|

| HPV6b E7 | E7 Oncogene from low-risk Human Papillomavirus | f-TGCAACCTCCAGACCCTGTA |

| r-CACTGCACAACCAGTCGAAC | ||

| HPV16 E7 | E7 Oncogene from high-risk Human Papillomavirus | f-GAACCGGACAGAGCCCATTA |

| R-ACGAATGTCTACGTGTGTGC |

Forward primers are designated by f and reverse primers by r

Sequences are listed 5′ to 3′.

3. Results

3.1. Differential hydrophobicity patterns in E7 sequences for high- and low-risk HPV

Detailed analysis of the amino acid sequences of E7 from eight of the most clinically prevalent high-risk genotypes and eight of the most prevalent low-risk genotypes of HPV revealed the presence of hydrophobic residues near the phosphorylation sites in low-risk E7, as shown in Fig. 2A. To quantitate the potential differences in hydrophobicity, grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) scores were assigned to each full-length sequence, giving positive numerical values to hydrophobic amino acids and negative values to hydrophilic residues (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982). Fig. 2B shows that the low-risk E7 sequences overall have a less negative score, suggesting the presence of more hydrophobic residues. These calculations were repeated for alignments of the disordered domains CR1/CR2, and despite the shorter sequence, low-risk E7 continues to show increased levels of hydrophobic residues compared to high-risk (Fig. 2C). It would be predicted that this intrinsically disordered region would contain predominantly charged and polar residues, so the increased hydrophobicity for these low-risk genotypes stands out and may play a role in the previous observation that low-risk E7 tends to have decreased binding affinity to host cellular proteins compared to high-risk (Gage et al., 1990; Dyson, 2016). GRAVY scores were then determined for the CK2 recognition sequences, and the results shown in Fig. 2D reflect the presence of the valine residues observed for low-risk genotypes. This suggests that these valine residues may play a role in the differences in phosphorylation levels between high- and low-risk E7 observed previously in cells (Munger et al., 1989; Barbosa et al., 1990; Sang and Barbosa, 1992).

Fig. 2.

Sequential and hydropathy analysis for E7 from the most clinically relevant high- and low-risk HPV genotypes. (A) Alignment of the CK2 recognition sequences for E7 from high- and low-risk HPV (gray and black respectively). The phosphoacceptor serine residues, acidic residues and nonpolar residues are indicated in blue, red and green respectively. (B) Grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) scores for full-length E7 sequences, comparing E7 from high-risk (gray), to E7 from low-risk (black). (C) GRAVY scores for the aligned disordered domains, approximately residues 1 – 61, encompassing CR1 and CR2 for E7 from high- and low-risk HPV (gray and black respectively). (D) Average hydropathy index for the CK2 recognition domain and site(s) of phosphorylation aligned in C, for E7 from high- and low-risk HPV (gray and black respectively). (E) Designed point mutations within the CR2 domain of E7 from HPV16, highlighting the CK2 recognition sequence with acidic residues in red, serine residues in blue and hydrophobic residues in green. The serine mutation at position 29 is designed to resemble the hypervirulent natural variant of E7, while the substitution and insertion of valine residues resembled E7 from the low-risk genotype HPV6b.

The investigation of the CK2 recognition sequences revealed several patterns, further verifying that the correlation between E7 sequence and risk factor is complex. For example, HPV61, a low-risk genotype, has a third serine residue in the +2 position to the phosphoacceptor serines. This pattern is observed in HPV7 and 40, which are also low-risk genotypes and considerably low prevalence (Chen et al., 2018; de Villiers et al., 1989; Sun et al., 2017). At the same time, genotypes with a third serine reside in the −2 position to the phosphoacceptor serine residues tend to be classified as high-risk, and more closely resemble HPV18 and HPV45, which are highly prevalent and have demonstrated increased virulency, similar to the N29S variant of HPV16 E7 (Zine El Abidine et al., 2017; Guan et al., 2012). Further investigation of HPV61 E7 shows that while the hydropathy score within the CK2 recognition sequence is similar to that of high-risk genotypes, the GRAVY score for the full-length protein was calculated to be +0.021, which was the most hydrophobic sequence out of the entire group. This serves as an additional example of the complexity of this system because it is possible that for this genotype, these additional hydrophobic residues within the CR3 domain are contributing to decreased interactions necessary for cellular transformation (Todorovic et al., 2012). Further investigation is warranted to compare phosphorylation efficiency for E7 genotypes with neutral/nonacidic serine residues in the +2 versus the −2 position from the phosphoacceptor residues and determine if this correlates to cellular activity. Given the complexity of this system, the scope of this work focuses on the presence of hydrophobic valine residues at the -2 and +4 positions in E7 present in prevalent low-risk genotypes, compared to high-risk E7 which tends to have uninterrupted acidic residues in positions +1 to +5/6 (Fig. 2A). Ultimately, this work seeks to provide information regarding one piece of a very complex puzzle.

3.2. Site-directed mutagenesis of the CK2 recognition sequence

To better understand how the amino acid sequence neighboring the phosphoacceptor sites impact the phosphorylation of E7, several point mutations were made to E7 from HPV16, which is the most clinically prevalent high-risk genotype (Fig. 2E). The first mutation, N29S, resembles the natural variant of HPV16 shown to be phosphorylated at a third serine position within the CK2 recognition sequence with an associated increase in risk for cancer (Zine El Abidine et al., 2017). The additional point-mutations sought to change the CK2 recognition sequence of E7 from HPV16 to resemble that of the prevalent low-risk genotype, HPV6b. The mutation of asparagine to valine at position 29 puts a hydrophobic residue at the −2 position relative to the serines directly in the CK2 active site, while the insertion of a valine residue at position 36 places the hydrophobic residue at the +4 position relative to the serines, representing a central part of the CK2 recognition sequence (Meggio et al., 1994). The double mutant, N29V/+36 V replicates only the CK2 recognition sequence of low-risk HPV6b, as shown in Fig. 1, while maintaining the peripheral sequence of E7 from high-risk HPV16. As such, these point mutations should not directly influence pRb interaction as they do not impact the LxCxE motif, which is the primary binding domain for pRb (Chemes et al., 2010). Additionally, previous NMR analysis with E7(1–51) has shown that N29 experiences minimal chemical shift perturbation in the presence of pRb and the aspartic/glutamic acid residues within the CK2 recognition sequence show no indication of direct pRb interaction (Jansma et al., 2014).

From an NMR perspective, it is also very challenging to observe resonance signals corresponding to a folded protein domain in the presence of a disordered domain, since amino acids within a disordered region will give much stronger signal. It is therefore not possible to observe the CR3 domain in the presence of the CR1/CR2 domain. In a previous work, it was demonstrated that the chemical shift positions for the residues in the E7(1–51) construct do not change in the presence of CR3 (Jansma et al., 2014). As a result, these mutations were made in parallel to both a disordered domain CR1/CR2 construct E7(1–51), for NMR analysis, and to full length E7 for in-cell studies since the presence of CR3 is necessary for function within a cell.

3.3. Phosphorylation efficiency of the disordered domain of E7

NMR spectroscopy is an excellent technique for measuring the phosphorylation of specific amino acid residues within proteins (Nogueira et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020). The presence of a phosphate group significantly alters the atomic environment of the phosphoacceptor serine, thus changing its behavior in a magnetic field. This enables the measurement of phosphorylation on an atomic scale in real time. This is particularly useful for E7 since phosphorylation is occurring at two adjacent serine residues and their corresponding resonance signals within a 1H-15N HSQC are well resolved for both nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated samples (Jansma et al., 2014; Nogueira et al., 2017). It is therefore possible to observe the two individual phosphorylation events simultaneously. If spectra are recorded every hour, phosphorylation may be observed over time by recording the decrease in peak intensity for the resonance signals corresponding to the nonphosphorylated serine residues as well as the increase in peak intensity for the resonance signals of the phosphorylated serine residues (Nogueira et al., 2017).

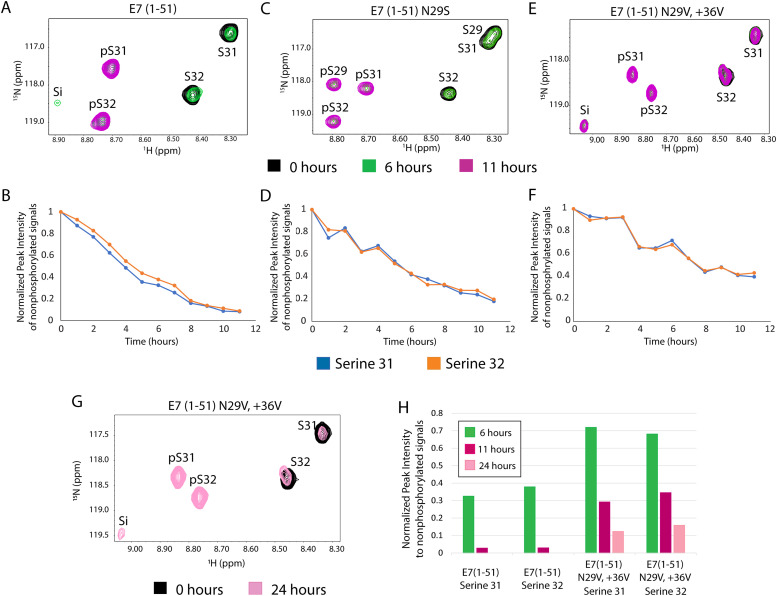

The 1H-15N HSQC spectra for samples of the disordered domain of E7(1–51) from HPV16, taken at 0, 6 and 11 h are shown in Fig. 3A (full spectrum and time course for all serine residues shown in Supplemental Figure 1A). The resonance signals for the serine residues at positions 31 and 32 are indicated for both their nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms. Under these conditions, Fig. 3A shows that the E7 protein from HPV16 is >90 % phosphorylated by hour 11. An intermediate resonance signal corresponding to one of the serine residues, was observed and labeled Si in Fig. 3A and Supplemental Figure 1A. This signal appeared at hour 1 and incrementally disappeared between hours 6 and 11, likely representing a serine residue which has not been phosphorylated yet changes chemical shift position because of phosphorylation of the neighboring serine. This suggests that the serine residues may be phosphorylated one at a time. Leucine at position 28 and aspartic acid at position 30 demonstrate modest changes in chemical shift in response to phosphorylation on a similar time scale as the serine residues, suggesting neighboring amino acids are directly impacted by phosphorylation (Supplemental Figure 1A). While CK2 is known as a serine/threonine kinase (Ghildyal et al., 2022), Supplemental Figure 1A demonstrates that the four threonine residues, labeled T5, T7, T19 and T20 on the 1H-15N HSQC do not experience any changes in their chemical shift positions, suggesting they are not phosphorylated, giving further support to the importance of the acidic recognition sequence for phosphorylation by CK2.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation analysis for E7(1–51), E7(1–51) N29S and E7(1–51) N29V/+36 V. All NMR spectra are displaying resonance frequencies recorded after 0, 6 and 11 h of the phosphorylation assay, shown in black, green, and magenta, respectively. 1H-15N HSQC are shown for E7(1–51) (A), E7(1–51)N29S (C), and E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V (E), highlighting nonphosphorylated serine residues, S29, S31 and S32, phosphorylated serine residues, pS29, pS31 and pS32 as well as the intermediate signal, Si. Measurements of the normalized peak intensities of E7(1–51) (B), E7(1–51)N29S (D) and E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V (F) for nonphosphorylated serines 31 and 32 are shown in blue and orange respectively. (G) 1H-15N HSQC for E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V mutant following phosphorylation over 24 h, with time 0 shown in black and 24 h after the addition of CK2 shown in pink. Resonance signals corresponding to the phosphorylated, nonphosphorylated, and intermediate forms of serines 31, 32 and intermediate Si are labeled. (H) Measure of the normalized peak intensity for nonphosphorylated serines 31 and 32, comparing hours 6, 11 and 24 for both E7(1–51) and E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V, indicated in green, magenta and pink respectively.

The intensity values for each of the resonance signals corresponding to the nonphosphorylated, phosphorylated and intermediate forms of serines 31 and 32 were measured and plotted as a function of reaction time. Fig. 3B shows the decrease in the intensity for the nonphosphorylated resonance signals corresponding to serine 31 and 32, while Supplemental Figure 1B shows the full profile, including the increase in intensity for resonance signals corresponding to phosphorylated serine 31 and 32. The intensity values for the intermediate signal are shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

These results demonstrate that by hour 11, >90 % of the protein is in the fully phosphorylated state and the reaction is complete. This is very similar to previous investigations of the phosphorylation of serines 31 and 32 in the disordered region of E7 and act as a control for the remainder of the analysis (Nogueira et al., 2017). The overall conditions for this assay were maintained for each of the subsequent mutant forms of HPV16 E7(1–51), to ensure that phosphorylation efficiency could be directly compared to the original sample, additionally this experiment was repeated as a control alongside each mutant to ensure the conditions were maintained. The phosphorylation assay was also attempted with the disordered domain of low-risk E7 from HPV6b, but the peptide precipitated out of solution throughout the course of the assay, making the results inconclusive. Given the more hydrophobic nature of low-risk E7, it was very challenging to keep the protein soluble over long periods of time in aqueous buffer under these assay conditions.

3.4. Phosphorylation analysis of E7(1–51)N29S

Mutation of the asparagine residue at position 29 to a third serine at the -2 position from the native phosphoracceptor serine residues, E7(1–51)N29S, replicated the natural variant of E7 with increased virulency. While it was previously shown that this serine was being phosphorylated, the timescale relative to the two native serines was unknown (Zine El Abidine et al., 2017). The assay was carried out over 12 h and the results for hours 0, 6 and 11 are shown in Fig. 3C, with the full spectrum shown in Supplemental Figure 3A. As seen for E7(1–51), there is no visible resonance signal corresponding to the nonphosphorylated serine residues by hour 11. The neighboring leucine at position 28 as well as the aspartic acid at 30 experience a greater change in chemical shift position because of phosphorylation at reside 29. Additionally, glutamic acid at position 33 shifts position in response to the additional phosphorylation site. The intensities of the peaks corresponding to the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated serine residues were measured and plotted as a function of reaction time showing that all three serine residues are >80 % phosphorylated after 11 h and follow a profile similar to E7(1–51) as shown in Fig. 3D and Supplemental Figure 3B The appearance of phosphorylated serines reflects this timescale (Supplemental Figure 3B). Taken together, this indicates that position 29, which is at the −2 position relative to the serine residues, is directly in the active site of CK2 and thus susceptible to phosphorylation on the same time scale as the native serine residues.

3.5. Phosphorylation analysis of E7(1–51)N29V, E7(1–51)+36 V, and E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V

Phosphorylation efficiency was expected to decrease if valine residues were inserted into the E7 sequence of HPV16 in the same positions found in the corresponding CK2 recognition region of low-risk E7 from HPV6b (Fig. 1). The serine residues themselves were left in their native positions to focus only on recognition and subsequent interaction with CK2. Two single point mutations, outlined in Fig. 2E, replaced the asparagine residue at position 29 with a valine, E7(1–51)N29V, followed by the insertion of a valine residue at position 36, E7(1–51)+36 V. A third double mutant was generated combining both of these mutations to generate a construct that closely resembled HPV6b solely in the CK2 binding region neighboring the phosphoacceptor serine residues, E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V.

The results demonstrate that the valine at position 29, E7(1–51)N29V, modestly decreased phosphorylation efficiency, by approximately 20 % compared to E7(1–51) as shown in Supplemental Figure 4. The resonance signal corresponding to the intermediate peak also remained visible for a longer period of time (Supplemental Figure 2). The single insertion of the valine at position 36 significantly decreased phosphorylation efficiency to the point that approximately 40 % of the nonphosphorylated protein remained after 11 h (Supplemental Figure 4C and D). The signal corresponding to the intermediate peak maintained higher intensity throughout the assay and remained present after 11 h of incubation with CK2 (Supplemental Figure 2). The double mutant, E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V had the most dramatic results with the resonance signals in the 1H-15N HSQC showing significantly higher intensities for the nonphosphorylated serine residues and the intermediate resonance signals at hour 11, to the point that they are clearly visible at this contour level (Fig. 3E). Fig. 3F indicates that almost 50 % of the protein remains in the nonphosphorylated form after 11 h, which shows the most significant decrease in phosphorylation efficiency compared to E7(1–51). Additionally, the peak corresponding to the intermediate was approximately 20 % of the full peak intensity throughout each time point and maintained this intensity after 11 h of incubation with CK2 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Finally, E7 (1–51) and the double mutant E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V were incubated with CK2 for an extended time course of 24 h. The resonance signals for E7(1–51)N29V/+36 V, corresponding to the nonphosphorylated form of both serine residues as well as the intermediate signal, are all clearly visible after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 3G). The signal intensities corresponding to 6, 11 and 24 h are plotted for both E7(1–51) and N29V/+36 V with approximately 10–15 % of the nonphosphorylated serine residues still present at 24 h, while the nonphosphorylated signal for E7(1–51) shows <10 % of its original intensity after 11 h (Fig. 3H). Taken together, these results suggest that the presence of hydrophobic valine residues in the CK2 recognition sequence at the −2 and +4 positions relative to the phosphoracceptor serine residues of E7 account for a substantial reduction in the ability of CK2 to phosphorylate the protein in vitro.

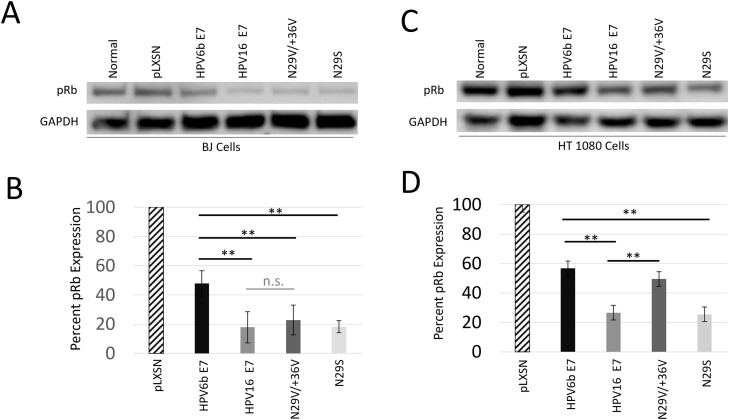

3.6. pRb degradation in cells is mediated by the CK2 binding domain of E7

Our NMR results in vitro indicate that the introduction of non-polar valine residues within the CK2 recognition sequence of E7 leads to a decreased rate of phosphorylation at serines 31 and 32. These studies were extended into a cell model to determine the functional effect of altered rates of phosphorylation by analyzing the degradation of one of E7’s direct targets, the retinoblastoma protein (pRb). Three separate cell lines were analyzed: BJ cells, fibroblasts derived from human foreskin, HT-1080 cells, a human epithelial line derived from a fibrosarcoma, and primary human cervical epithelial cells (HCxECs). Importantly, these three cell models all have a reported normal pRb pathway being primary cells (HCxECs) or cell lines whose transformation was distinct from the pRb pathway, whereas in many transformed cell lines this pathway is often aberrantly regulated (de Magalhaes et al., 2002; Li et al., 1995). Stable, transgenic cells lines were generated from each with full length E7 from low-risk HPV6b or high-risk HPV16, or the plasmid only negative control (pLXSN). High-risk HPV16 E7 was modified within the CK2 recognition sequence (HPV16 E7 N29V/+36 V) to resemble the low-risk version, comparable to the double mutant used in the phosphorylation studies, but with the full-length E7 for our cellular studies. This double mutant is otherwise identical to full length high-risk E7, except for the two amino acid changes whereby asparagine at residue 29 is changed to valine (N29V) and an additional valine is inserted at position 36 (+36 V). The natural variant of high-risk HPV16 E7 whereby an additional serine residue is included in the CK2 site (N29S) was also generated.

We demonstrate that lysates from either BJ cells or HT1080 cells stably expressing E7 have decreased levels of pRb protein (Fig. 4), presumably due to E7 mediated pRb degradation. Even low-risk HPV6b E7 results in a greater than 40 % reduction in pRb protein levels in both BJ and HT-1080 stable cells. Notably the pRb protein levels were lowest in the high-risk HPV16 E7 cells lines, as well as the natural variant HPV16 E7 N29S cell lines with a greater than 74 % reduction in pRb levels when compared to vector control lines. The naturally occurring high-risk variants have about half the pRb levels when compared to the low-risk lines, arguably due to increased E7-mediated pRb degradation related to the increased functional efficiency for transformation of high-risk E7. Interestingly, the double mutant (N29V/+36 V) in which the CK2 binding site resembles the low-risk HPV6b demonstrated higher levels of pRb relative to high-risk HPV16 E7 in HT-1080 stable cell lines, thus less degradation of pRb (Fig. 4). In the HT1080 cells, pRb degradation was reduced in the HPV16 E7 N29V/+36 V double mutant to levels equivalent to low-risk E7 from HPV6b despite being high-risk E7 in all regions except the CK2 recognition site. These results further demonstrate the significance of the valine residues within the CK2 recognition sequence, not only for serine phosphorylation, but for the oncogenic functional activity of E7. Expression of E7 RNA from either low-risk or high-risk variants in the stable lines was verified by quantitative PCR analysis and demonstrated to be relatively equivalent between the different lines (Supplemental Figure 5). In addition, HPV16 E7 protein levels in the HT-1080 stable cells lines using the high-risk variants likewise had similar E7 protein expression levels (Supplemental Figure 6). Taken together, this data suggests that differences in pRb degradation and cellular proliferation does not appear to be caused by differences in E7 expression levels, but rather alterations in activity caused by mutagenesis of key residues within the CK2 recognition sequence.

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis from stable cell lines expressing full length HPVE7 variants. BJ cells (A) or HT-1080 cells (C) were untreated (Normal) or then transduced with the control vector (pLXSN), low-risk HPV6b E7, high-risk HPV16 E7, HPV16 E7 N29V/+36 V or HPV16 E7 N29S. Cell lysates were examined for pRb protein expression levels as well as the housekeeping gene GAPDH. (B) The relative pRb band intensities within the BJ cells (B) or the HT-1080 cells (D) are the mean of three measurements from independent experiments and the error bars indicate the standard deviation within the group. The intensities were normalized relative to the pLXSN control. ** indicates a p < 0.01 between the indicated groups, and n.s. indicates not significant.

3.7. Increased proliferation and survival of primary cervical cells overexpressing E7 from high-risk HPV

The pRb protein is an established tumor suppressor that inhibits cell cycle progression. Thus, by modifying pRb levels as we have shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5), we should likewise observe changes in the rate of cell proliferation. Rather than using a transformed cell line, we utilized human primary cervical epithelial cells (HCxECs) infected with the full length E7 variants as described above. Proliferation rates were determined by analyzing EdU incorporation. There was a statistically significant increase in the rate of proliferation for cervical cells infected with either E7 from HPV16 or the HPV16 E7 N29S variant, when compared to E7 HPV6b, the low-risk variant (Fig. 5A). The double mutant (HPV16 E7 N29V/+36 V) had significantly decreased levels of cell proliferation relative to high-risk HPV (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

EdU DNA cell proliferation assay in primary human cervical epithelial cells stably infected with full length HPV E7 variants. (A) Representative micrographs of cervical cells that were untreated (Normal) or then transduced with the control vector (pLXSN), low-risk HPV6b E7, high-risk HPV16 E7, HPV16 E7 N29V/+36 V or HPV16 E7 N29S. Data is representative of at least six biological replicates. (B) Quantification of the cell proliferation percentages are determined by taking the proliferating cells (indicated in green) out of the total population (indicated in blue). Statistical significance was inferred by one way ANOVA (** p < 0.05). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Interestingly, as we maintained the primary human cervical epithelial cells it was noted that the cells infected with E7 from high-risk HPV variants (both HPV16 E7 and HPV16 E7 N29S) grew more rapidly with prolonged growth to higher passage numbers prior to senescence. Cells infected with E7 from the low-risk HPV variant (HPV6b), or the vector control senesced between passage 4–7, as did the uninfected cells (Fig. 6). Likewise, the E7 double mutant from high-risk HPV with two amino acid changes which mimics the CK2 region from low-risk HPV6b, had no proliferative advantage compared to controls having lost the oncogenic advantage of the high-risk variant. Contrastingly, the primary cervical cells infected with the high-risk variants continued to proliferate between 14 and 16 passages, conferring an extended lifespan. These data demonstrate increased proliferation of cells transfected with high risk E7, effects that are mitigated by altering the two residues in the CK2 recognition sequence to the hydrophobic valines observed in low-risk E7 variants. These results correlate with the demonstrated effects on pRb degradation and serine phosphorylation efficiency.

Fig. 6.

Passage survivorship of primary human cervical epithelial cells (HCxECs) stably expressing HPV E7 variants. Uninfected HCxECs (Normal) or infected cells were passaged until they reached senescence.

4. Discussion

Certain genotypes of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) induce cellular transformation, attributing to almost all cervical cancers as well as an increasingly large variety of other cancers (Manini and Montomoli, 2018; McBride, 2017; Szymonowicz and Chen, 2020; Roman and Aragones, 2021). At the same time, many low-risk genotypes are incapable of transforming cells, instead resulting in benign skin lesions (Orlando et al., 2012; Thomsen et al., 2014). Interaction between viral E7 and host cell retinoblastoma protein (pRb), as well as other members of the pocket protein family, has been shown throughout multiple studies to be a crucial part of the oncogenic properties of high-risk viral genotypes of HPV (Gage et al., 1990; Basukala et al., 2022; Halbert et al., 1991). This interaction of E7 with the pRb/E2F system results in direct binding to pRb, releasing E2F and thus facilitating the expression of DNA synthesis machinery and initiation of the cell cycle (Dick and Dyson, 2002). This is advantageous to the virus by activating the DNA replication machinery leading to more viral production and in turn an increased number of infected cells. To further increase and maintain this cell proliferation, E7 not only displaces E2F from pRb, thus inhibiting the tumor suppressor function, but it also causes the degradation of pRb (Szymonowicz and Chen, 2020). Targeting pRb and similar family members for degradation to prevent their further regulation of cell proliferation requires the formation of ternary complexes and multiple protein:protein interactions, similar to E1A from the oncogenic adenovirus (Jansma et al., 2014; Ferreon et al., 2009).

Despite the ability of E7 from low-risk HPV genotypes to bind pRb, the overall affinity is insufficient to induce the level of pRb degradation required to dysregulate the cell cycle to the point of tumorogenesis (Heck et al., 1992; Jansma et al., 2014; Gage et al., 1990; Zhang et al., 2006). It has been previously established that phosphorylation at the conserved serine residues in E7 is critical for optimal interaction with cellular binding partners, and modification of these phosphoacceptor serines has a significant impact on high-risk E7 function (Chemes et al., 2010; Heck et al., 1992; Basukala et al., 2019; Nogueira et al., 2017). Here we have taken this one step further and demonstrated that this increased transformational capability is also associated with the efficiency by which CK2 phosphorylates these serine residues. Specifically, we have maintained the integrity of the phosphoacceptor serines and instead added two hydrophobic valines within the Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) recognition sequence of E7, as observed in low-risk HPV variants. The presence of these valine neighbor amino acids, adjacent to the phosphoacceptors, significantly impacted the ability of CK2 to phosphorylate the protein, and led to less pRb degradation within cells, even comparable to that of E7 from low-risk HPV.

To hijack host cells to the degree of tumorigenesis, high-risk E7 has been shown to dysregulate not only cellular proliferation via pRb, but also innate and adaptive immunity, as well as additional cellular pathways still under investigation (Songock et al., 2017). This ultimately requires E7 to interact directly with a myriad of host-cell proteins, bridging interactions between multiple proteins to directly interfere with these cellular processes (McLaughlin-Drubin and Munger, 2009; Basukala et al., 2022; Hatterschide et al., 2022; Nouel and White, 2022). It is therefore vital that E7 be as versatile as possible to carry out such a wide range of cellular activities. E7 achieves this level of versatility in part through intrinsic disorder. Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) are defined as proteins with at least half of their amino acid residues lacking fixed secondary and tertiary structure (Dyson and Wright, 2005). The CR1/CR2 domains of E7 have demonstrated highly dynamic behavior in the context of a protein binding partner, adopting multiple orientations, to the point that the complex structure was impossible to solve by NMR spectroscopy (Risor et al., 2021). This lack of structure and inherent dynamic nature, leaves their entire primary sequence exposed within the cellular environment, enabling the adoption of a very broad binding profile (Bah and Forman-Kay, 2016; Miskei et al., 2017).

Amino acid composition plays a critical role in the binding of IDPs to structured proteins. Multiple modes of binding for IDPs include folding-upon-binding, which may rely on hydrophobic contacts with the binding partner, or more dynamic interactions, often requiring electrostatic amino acids (Basu and Bahadur, 2020; Meszaros et al., 2007; Wright and Dyson, 1999; Wright and Dyson, 2009). For these more dynamic interactions, the ability to elongate the binding surface area may provide a definitive advantage. Since the functional capabilities of IDPs are often strongly influenced by post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, the introduction of additional negative charges from phosphate groups to what had been neutral serine or threonine residues, significantly increases the electrostatic capability of the disordered protein (Jin and Grater, 2021). In the case of E7 from high-risk HPV16, the theoretical isoelectric point of the entire protein is 4.20, with approximately 20 % of the primary structure composed of aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues, suggesting an already strong overall negative charge. This observation is enhanced in the intrinsically disordered region, containing CR1/CR2, which has an even more acidic isoelectric point of 3.85. In fact, the CK2 recognition sequence immediately adjacent to the phosphoacceptor serine residues is composed of 100 % negatively charged aspartic/glutamic acid residues for high-risk HPV16 E7. Electrostatic mapping of this recognition sequence is shown in Fig. 7 for E7 from both high-risk HPV16 and low-risk HPV6b. Previous studies of IDPs have shown that the addition of negatively charged phosphate groups to an already negatively charged disordered sequence is believed to further enhance their extended conformations due to charge-charge repulsion (Jin and Grater, 2021). Even prior to phosphorylation, E7 from high-risk HPV16 has a more negatively charged surface compared to low-risk HPV6b (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting an already more elongated structure due to charge-charge repulsion and increased polarity in an aqueous environment. If the phosphate groups on the two serine residues are included in the modeled peptide, the electrostatic difference between low-risk and high-risk becomes even more pronounced (Fig. 7C). This would ultimately provide E7 with both additional negative charges for electrostatic interactions with binding partners, as well as a more elongated and accessible binding surface, enabling increased ability for protein interaction within host cells.

Fig. 7.

Electrostatic map of the peptide with CR2 of E7, including the serine residues and the CK2 recognition sequence with the amino acid sequences shown. (A) Peptide of nonphosphorylated E7 from low-risk HPV6b. (B) Peptide of nonphosphorylated E7 from high-risk HPV16. (C) Peptide of phosphorylated E7 from high-risk HPV16. This image was generated using PyMOL (Schrodinger, 2010).

In order to achieve phosphorylation for the purpose of dysregulating the cell cycle, E7 must first subjugate CK2. Casein Kinase 2 is an extremely abundant kinase present in cells and has been implicated in a wide array of processes ranging from transcription to cell cycle progression and survival (Nunez de Villavicencio-Diaz et al., 2017; Venerando et al., 2014). Previous studies have demonstrated that CK2 levels are elevated in several types of cancer as well as virally infected cells (Borgo et al., 2021; Guerra and Issinger, 1999; Litchfield, 2003). CK2 is not only readily available within many cell types, but also constitutively active, which makes it an attractive target to viruses requiring phosphorylation for optimal function (Ramon et al., 2022; Piirsoo et al., 2019). High-risk E7 from HPV16 has a “classic” CK2 recognition sequence, with the requisite acidic amino acid residues in the −1 to +5 positions relative to the phosphoacceptor serines (Meggio et al., 1994). Additionally, the lack of secondary structure around the serine residues is advantageous for CK2 recognition (Rekha and Srinivasan, 2003). Having two phosphoacceptor serine residues may also provide an additional advantage to E7 in that the presence of a phosphorylated serine residue at the +3 position has been shown to further aid in CK2 recognition (Rekha and Srinivasan, 2003). The presence of the intermediate peak seen throughout this work suggests the possibility that the serines may be differentially phosphorylated and phosphorylation of one may further promote phosphorylation of the other.

The disordered domain of E7 from high-risk HPV16 has been extensively investigated over the years (Roman and Munger, 2013; Jones et al., 2024). The pRb binding domain, known as the LxCxE motif, in residues 22 – 26, is essential for displacement of E2F from pRb (Chemes et al., 2010; Heck et al., 1992; Barbosa et al., 1990). Constructs lacking this domain have significantly diminished functional capabilities in cells (Dick and Dyson, 2002). Likewise, the phosphoacceptor serine residues at positions 31 and 32 near to the LxCxE motif are crucial to the oncogenic properties of E7 (Basukala et al., 2019). In this study, we introduced minimally active hydrophobic valine residues neighboring these two domains in a region shown to have no direct contact with pRb, while maintaining full functionality of both the LxCxE motif and the serine phosphoacceptors. These two amino acid changes were able to alter the functional capabilities of E7 from high-risk HPV16 to the point that pRb degradation, proliferation and senescence in the cells, was comparable to that of E7 from low-risk HPV6b.

5. Conclusion

Despite current research and broad spectrum vaccines, HPV related cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide with approximately 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths reported by the World Health Organization in 2020. Further research is needed to better understand HPV induction of tumor cells, and to determine ways to prevent HPV associated cancer risks in infected populations. Understanding the mechanistic causes of oncogenesis in high-risk HPV infection can ultimately help to guide both screening methods as well as therapeutics to treat existing infections. The work presented in this study provides a compelling argument that phosphorylation efficiency, dictated by a small region not previously known for protein function, has a dramatic effect on the oncogenic properties of high-risk E7.

Funding

This work was funded in part by PLNU Research Associates, the PLNU Research And Special Projects (RASP) program, and PLNU Alumni Association.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Madison Malone: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ava Maeyama: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Naomi Ogden: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Kayla N. Perry: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Andrew Kramer: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Caleb Bates: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Camryn Marble: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ryan Orlando: Formal analysis, Data curation. Amy Rausch: Formal analysis, Data curation. Caleb Smeraldi: Formal analysis, Data curation. Connor Lowey: Formal analysis, Data curation. Bronson Fees: Data curation. H. Jane Dyson: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. Michael Dorrell: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Heidi Kast-Woelbern: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ariane L. Jansma: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this manuscript would like to thank first Dr. Peter E. Wright for the use of the Biomolecular NMR facility at TSRI, as well as mentorship to many of our undergraduate research students. Collaboration with the Wright/Dyson lab at TSRI has been invaluable to this project and to our overall program. Gerard Kroon and Dr. Maria Martinez Yamouth from TSRI have provided help and support in NMR spectroscopy, HPLC, structural biology and overall molecular biology. We would also like to thank additional members of our research teams who contributed to this project: Kenton Bosch, Lacey Cullpepper, Madilyn Dedera, Isabel Garcia, Jacob Grupe, Katharine Johnson, Abbey Mandagie, Elizabeth Mills, Dr. Taylor Steele, Michael Wheelock, and Nicholas Willingham.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2024.199446.

Contributor Information

Heidi Kast-Woelbern, Email: HeidiWoelbern@pointloma.edu.

Ariane L. Jansma, Email: ajansma@pointloma.edu.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Bah A., Forman-Kay J.D. Modulation of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Function by Post-translational Modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:6696–6705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.695056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa M.S., Edmonds C., Fisher C., Schiller J.T., Lowy D.R., Vousden K.H. The region of the HPV E7 oncoprotein homologous to adenovirus E1a and Sv40 large T antigen contains separate domains for Rb binding and casein kinase II phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1990;9:153–160. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Bahadur R.P. Do sequence neighbours of intrinsically disordered regions promote structural flexibility in intrinsically disordered proteins? J. Struct. Biol. 2020;209 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.107428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basukala O., Mittal S., Massimi P., Bestagno M., Banks L. The HPV-18 E7 CKII phospho acceptor site is required for maintaining the transformed phenotype of cervical tumour-derived cells. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basukala O., Trejo-Cerro O., Myers M.P., Pim D., Massimi P., Thomas M., et al. HPV-16 E7 interacts with the endocytic machinery via the AP2 Adaptor mu2 Subunit. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.02302-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezutskaya E., Yu B., Morozov A., Raychaudhuri P., Bagchi S. Differential regulation of the pocket domains of the retinoblastoma family proteins by the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1277–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi G., Mangiagalli M., Barbiroli A., Longhi S., Grandori R., Santambrogio C., et al. Distribution of charged residues affects the average size and shape of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biomolecules. 2022:12. doi: 10.3390/biom12040561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgo C., D'Amore C., Sarno S., Salvi M., Ruzzene M. Protein kinase CK2: a potential therapeutic target for diverse human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:183. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00567-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd E.M. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003;16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemes L.B., Sanchez I.E., Smal C., de Prat-Gay G. Targeting mechanism of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by a prototypical viral oncoprotein. Structural modularity, intrinsic disorder and phosphorylation of human papillomavirus E7. FEBS J. 2010;277:973–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Schiffman M., Herrero R., DeSalle R., Anastos K., Segondy M., et al. Classification and evolution of human papillomavirus genome variants: alpha-5 (HPV26, 51, 69, 82), Alpha-6 (HPV30, 53, 56, 66), Alpha-11 (HPV34, 73), Alpha-13 (HPV54) and Alpha-3 (HPV61) Virology. 2018;516:86–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ci X., Zhao Y., Tang W., Tu Q., Jiang P., Xue X., et al. HPV16 E7-impaired keratinocyte differentiation leads to tumorigenesis via cell cycle/pRb/involucrin/spectrin/adducin cascade. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;104:4417–4433. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes J.P., Chainiaux F., Remacle J., Toussaint O. Stress-induced premature senescence in BJ and hTERT-BJ1 human foreskin fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers E.M., Hirsch-Behnam A., von Knebel-Doeberitz C., Neumann C., zur Hausen H. Two newly identified human papillomavirus types (HPV 40 and 57) isolated from mucosal lesions. Virology. 1989;171:248–253. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers E.M., Fauquet C., Broker T.R., Bernard H.U., zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick F.A., Dyson N.J. Three regions of the pRB pocket domain affect its inactivation by human papillomavirus E7 proteins. J. Virol. 2002;76:6224–6234. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6224-6234.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H.J. Making Sense of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1013–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi R., Tsoukas M.M. Genital warts and other HPV infections: established and novel therapies. Clin. Dermatol. 2014;32:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreon J.C., Martinez-Yamout M.A., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Structural basis for subversion of cellular control mechanisms by the adenoviral E1A oncoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13260–13265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906770106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage J.R., Meyers C., Wettstein F.O. The E7 proteins of the nononcogenic human papillomavirus type 6b (HPV-6b) and of the oncogenic HPV-16 differ in retinoblastoma protein binding and other properties. J. Virol. 1990;64:723–730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.723-730.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S., Nor Rashid N., Mohamad Razif M.F., Othman S. Proteasomal degradation of p130 facilitate cell cycle deregulation and impairment of cellular differentiation in high-risk Human Papillomavirus 16 and 18 E7 transfected cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021;48:5121–5133. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly N., Parihar S.P. Human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins as risk factors for tumorigenesis. J. Biosci. 2009;34:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s12038-009-0013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alai M.M., Alonso L.G., de Prat-Gay G. The N-terminal module of HPV16 E7 is an intrinsically disordered domain that confers conformational and recognition plasticity to the oncoprotein. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10405–10412. doi: 10.1021/bi7007917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildyal R., Teng M.N., Tran K.C., Mills J., Casarotto M.G., Bardin P.G., et al. Nuclear transport of respiratory syncytial virus matrix protein is regulated by dual phosphorylation sites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022:23. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan P., Howell-Jones R., Li N., Bruni L., de Sanjose S., Franceschi S., et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131:2349–2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra B., Issinger O.G. Protein kinase CK2 and its role in cellular proliferation, development and pathology. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:391–408. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990201)20:2<391::AID-ELPS391>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert C.L., Demers G.W., Galloway D.A. The E7 gene of human papillomavirus type 16 is sufficient for immortalization of human epithelial cells. J. Virol. 1991;65:473–478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.473-478.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatterschide J., Castagnino P., Kim H.W., Sperry S.M., Montone K.T., Basu D., et al. YAP1 activation by human papillomavirus E7 promotes basal cell identity in squamous epithelia. eLife. 2022:11. doi: 10.7554/eLife.75466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck D.V., Yee C.L., Howley P.M., Munger K. Efficiency of binding the retinoblastoma protein correlates with the transforming capacity of the E7 oncoproteins of the human papillomaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:4442–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helt A.M., Galloway D.A. Mechanisms by which DNA tumor virus oncoproteins target the Rb family of pocket proteins. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:159–169. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Liu Y., Yao H., Zhao Y. NMR-based investigation into protein phosphorylation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;145:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansma A.L., Martinez-Yamout M.A., Liao R., Sun P., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. The high-risk HPV16 E7 oncoprotein mediates interaction between the transcriptional coactivator CBP and the retinoblastoma protein pRb. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:4030–4048. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F., Grater F. How multisite phosphorylation impacts the conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.A., Blevins R.A. NMR View: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.L., Thompson D.A., Munger K. Destabilization of the RB tumor suppressor protein and stabilization of p53 contribute to HPV type 16 E7-induced apoptosis. Virology. 1997;239:97–107. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.N., Miyauchi S., Roy S., Boutros N., Mayadev J.S., Mell L.K., et al. Computational and AI-driven 3D structural analysis of human papillomavirus (HPV) oncoproteins E5, E6, and E7 reveal significant divergence of HPV E5 between low-risk and high-risk genotypes. Virology. 2024;590 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2023.109946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J., Doolittle R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.O., Russo A.A., Pavletich N.P. Structure of the retinoblastoma tumour-suppressor pocket domain bound to a peptide from HPV E7. Nature. 1998;391:859–865. doi: 10.1038/36038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Fan J., Hochhauser D., Banerjee D., Zielinski Z., Almasan A., et al. Lack of functional retinoblastoma protein mediates increased resistance to antimetabolites in human sarcoma cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10436–10440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield D.W. Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem. J. 2003;369:1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Clements A., Zhao K., Marmorstein R. Structure of the human Papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein and its mechanism for inactivation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:578–586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manini I., Montomoli E. Epidemiology and prevention of human papillomavirus. Ann. Ig. 2018;30:28–32. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride A.A. Oncogenic human papillomaviruses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017:372. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin-Drubin M.E., Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology. 2009;384:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F., Marin O., Pinna L.A. Substrate specificity of protein kinase CK2. Cell Mol. Biol. Res. 1994;40:401–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszaros B., Tompa P., Simon I., Dosztanyi Z. Molecular principles of the interactions of disordered proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskei M., Gregus A., Sharma R., Duro N., Zsolyomi F., Fuxreiter M. Fuzziness enables context dependence of protein interactions. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:2682–2695. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger K., Phelps W.C., Bubb V., Howley P.M., Schlegel R. The E6 and E7 genes of the human papillomavirus type 16 together are necessary and sufficient for transformation of primary human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 1989;63:4417–4421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4417-4421.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe E.A., Delaforge E., Hartmann-Petersen R., Skriver K., Kragelund B.B. How phosphorylation impacts intrinsically disordered proteins and their function. Essays Biochem. 2022;66:901–913. doi: 10.1042/EBC20220060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira M.O., Hosek T., Calcada E.O., Castiglia F., Massimi P., Banks L., et al. Monitoring HPV-16 E7 phosphorylation events. Virology. 2017;503:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouel J., White E.A. ZER1 Contributes to the Carcinogenic Activity of High-Risk HPV E7 Proteins. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.02033-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez de Villavicencio-Diaz T., Rabalski A.J., Litchfield D.W. Protein Kinase CK2: intricate Relationships within Regulatory Cellular Networks. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2017:10. doi: 10.3390/ph10010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlenschlager O., Seiboth T., Zengerling H., Briese L., Marchanka A., Ramachandran R., et al. Solution structure of the partially folded high-risk human papilloma virus 45 oncoprotein E7. Oncogene. 2006;25:5953–5959. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando P.A., Gatenby R.A., Giuliano A.R., Brown J.S. Evolutionary ecology of human papillomavirus: trade-offs, coexistence, and origins of high-risk and low-risk types. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205:272–279. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petca A., Borislavschi A., Zvanca M.E., Petca R.C., Sandru F., Dumitrascu M.C. Non-sexual HPV transmission and role of vaccination for a better future (Review) Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:186. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piirsoo A., Piirsoo M., Kala M., Sankovski E., Lototskaja E., Levin V., et al. Activity of CK2alpha protein kinase is required for efficient replication of some HPV types. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon A.C., Basukala O., Massimi P., Thomas M., Perera Y., Banks L., et al. CIGB-300 peptide targets the CK2 phospho-acceptor domain on human papillomavirus E7 and Disrupts the Retinoblastoma (RB) complex in cervical cancer cells. Viruses. 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/v14081681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha N., Srinivasan N. Structural basis of regulation and substrate specificity of protein kinase CK2 deduced from the modeling of protein-protein interactions. BMC Struct. Biol. 2003;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risor M.W., Jansma A.L., Medici N., Thomas B., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Characterization of the high-affinity fuzzy complex between the disordered domain of the E7 Oncoprotein from High-Risk HPV and the TAZ2 domain of CBP. Biochemistry. 2021;60:3887–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman B.R., Aragones A. Epidemiology and incidence of HPV-related cancers of the head and neck. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021;124:920–922. doi: 10.1002/jso.26687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman A., Munger K. The papillomavirus E7 proteins. Virology. 2013;445:138–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang B.C., Barbosa M.S. Single amino acid substitutions in "low-risk" human papillomavirus (HPV) type 6 E7 protein enhance features characteristic of the "high-risk" HPV E7 oncoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:8063–8067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Verion 4.6.0. 2010.