SUMMARY

Although low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses (LPAIV) are detected in shorebirds at Delaware Bay annually, little is known about affected species habitat preferences or the movement patterns that might influence virus transmission and spread. During the 5-wk spring migration stopover period during 2007–2008, we conducted a radiotelemetry study of often-infected ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres morinella; n = 60) and rarely infected sanderlings (Calidris alba; n = 20) to identify locations and habitats important to these species (during daytime and nighttime), determine the extent of overlap with other AIV reservoir species or poultry production areas, reveal possible movements of AIV around the Bay, and assess whether long-distance movement of AIV is likely after shorebird departure. Ruddy turnstones and sanderlings both fed on Bay beaches during the daytime. However, sanderlings used remote sandy points and islands during the nighttime while ruddy turnstones primarily used salt marsh harboring waterfowl and gull breeding colonies, suggesting that this environment supports AIV circulation. Shorebird locations were farther from agricultural land and poultry operations than were random locations, suggesting selection away from poultry. Further, there was no areal overlap between shorebird home ranges and poultry production areas. Only 37% (22/60) of ruddy turnstones crossed into Delaware from capture sites in New Jersey, suggesting partial site fidelity and AIV gene pool separation between the states. Ruddy turnstones departed en masse around June 1 when AIV prevalence was low or declining, suggesting that a limited number of birds could disperse AIV onto the breeding grounds. This study provides needed insight into AIV and migratory host ecology, and results can inform both domestic animal AIV prevention and shorebird conservation efforts.

Keywords: ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres morinella), avian influenza virus, sanderling (Calidris alba), Delaware Bay, migration, radiotelemetry, resource selection, stopover ecology

RESUMEN

Ecología en los sitios de descanso durante la migración de primavera de las aves costeras hospederas de virus de influenza aviar en la bahía de Delaware.

Aunque los virus de influenza aviar de baja patogenicidad (LPAIV) se detectan en las aves costeras en la bahía de Delaware cada año, poco se conoce acerca de las preferencias de hábitat de las especies afectadas o de los patrones de movimiento que pueden influir en la transmisión y propagación del virus. Durante el período de descanso de cinco semanas durante la migración de primavera entre los años 2007 al 2008, se realizó un estudio de radiotelemetría en vuelvepiedras comunes (Arenaria interpres morinella; n = 60) que se infectan comúnmente y de correlimos tridáctilos (Calidris alba; n = 20) que son infectados raramente, para identificar los lugares y los hábitats importantes para estas especies (durante el día y la noche), determinar el grado de superposición con otras especies reservorios o con zonas de producción de aves comerciales, para determinar los posibles movimientos de los virus de influenza aviar alrededor de la Bahía, y para evaluar si es probable que los movimientos a largas distancias de los virus de influenza aviar después de la partida de estas aves costeras. Tanto los vuelvepiedras comunes y los correlimos tridáctilos se alimentan en las playas de la bahía durante el día. Sin embargo, los correlimos tridáctilos utilizan puntos de arena remotos durante la noche, mientras que los vuelvepiedras comunes principalmente utilizan colonias de reproducción de gaviotas y aves acuáticas en las marismas salinas, lo que sugiere que este entorno es compatible con la circulación de los virus de influenza aviar. La localización de las aves costeras se ubicaba más lejos de las operaciones agrícolas y avícolas, en comparación con lugares al azar, lo que sugiere la selección lejos de la avicultura. Además, no hubo coincidencia entre áreas de distribución de aves costeras y las zonas de producción avícola. Sólo el 37% (22/60) de los vuelvepiedras comunes cruzó a Delaware desde los lugares de captura en Nueva Jersey, lo que sugiere la fidelidad parcial al sitio y la separación genética entre los estados. Los vuelvepiedras comunes partieron en masa alrededor del primero de junio, cuando la prevalencia del virus de influenza aviar fue baja o en descenso, lo que sugiere que un número limitado de aves podría dispersar los virus de influenza aviar en las áreas de reproducción. Este estudio proporciona información necesaria sobre los virus de influenza aviar y la ecología de los huéspedes migratorios y los resultados pueden proporcionar información para los esfuerzos para la prevención del virus de influenza aviar de los animales domésticos y para la conservación de las aves costeras.

Avian influenza viruses (AIV) are of interest to both veterinary and public health experts, but their transmission from natural reservoir species into domestic animals or humans has been rarely documented. Low pathogenicity AIVs (LPAIV) are maintained in nature by certain groups of wild aquatic birds including waterfowl (particularly ducks, Anatidae) and gulls (Laridae) (43,56). Although some studies have found AIV in shorebirds (order Charadriiformes, strictly families Scolopacidae and Charadriidae), documented infections in shorebirds have been geographically localized and limited to few species (20,23,30,31). Many recent surveillance studies worldwide have failed to find AIV more than occasionally in shorebirds (e.g., 12,14,15,24,32,39,57).

However, AIV infections are regularly detected at Delaware Bay, on the Atlantic coast of North America, during spring migration stopover during May–early June. At this location, AIV infections are detected annually in ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres morinella), and prevalence has exceeded 15% in some years (20). Sympatric shorebird species are much less-often infected (20,34,35,51). It is not fully understood why AIV detections occur so frequently in shorebirds at this location, but very dense concentrations, up to 67 birds/m2 (19), of a species permissive to AIV infection (ruddy turnstones) is certainly a major factor (30). Delaware Bay is a major spring migratory stopover site for several species of shorebirds including red knots (Calidris canutus rufa), ruddy turnstones, sanderlings (Calidris alba), semipalmated sandpipers (Calidris pusilla), dunlins (Calidris alpina), and short-billed dowitchers (Limnodromus griseus) (9,13). Each of these populations have experienced declines since 1998 (42), most likely due to reduced availability of their main diet at this site, the eggs of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) (42); this is the result of overharvest in preceding decades (42). Other nonshorebird species also use the greater Delaware Bay ecosystem and might contribute to AIV maintenance; these include migrating and breeding waterfowl (Anseriformes), gulls (Larinae), terns (Sterninae), and wading birds (e.g., herons, egrets, night-herons (Ardeidae), and ibises (Threskiornithidae)). With the possible exception of herring gulls (Larus argentatus smithsonianus) and laughing gulls (Larus atricilla) (20,27), there has been limited study of AIV infections in these groups at Delaware Bay.

There are many gaps in our knowledge of AIV dynamics in ruddy turnstones and other shorebirds that use Delaware Bay as a spring migratory stopover. Despite the close proximity of major poultry production (the Delmarva Peninsula) to Delaware Bay, general stopover ecology and movement patterns of ruddy turnstones, which could be shedding AIV, at this stopover site are virtually unknown. Investigations into the movement patterns of potential AIV reservoir species, both at global and local scales, have been recommended to better understand the global ecology of AIV (16). The H5 and H7 subtypes are of particular interest because of their ability to mutate into highly pathogenic forms; both have been isolated from ruddy turnstones at Delaware Bay (20), Furthermore, detections of AIV infection in other shorebird species at this site are rare, despite their feeding on horseshoe crab eggs alongside infected ruddy turnstones on Delaware Bay beaches. Subtle differences in habitats used or other aspects of their stopover ecologies might help explain why virus circulation is virtually limited to ruddy turnstones. Finally, it is unknown whether shorebirds such as ruddy turnstones are capable of transporting AIV long distances, possibly even between continents. Ruddy turnstones use Delaware Bay en route to breeding grounds in the low Arctic (40,45).

Given these knowledge gaps and the potential consequences of transmission to nearby poultry, we conducted a radiotelemetry study of ruddy turnstones and sanderlings during the 5-wk stopover period. Sanderlings are rarely infected (35) but share feeding habitat with ruddy turnstones and were studied for comparison. Our objectives were to answer the questions: 1) Which habitats or locations are important for ruddy turnstones and sanderlings during their stopover at Delaware Bay, during both daytime and nighttime? 2) Are habitats or locations used by ruddy turnstones and sanderlings overlapping with, or in close proximity to, areas used by other species important in AIV epidemiology (gulls or waterfowl) or with areas used for poultry production? 3) What movement patterns are exhibited by ruddy turnstones, which could spread AIV locally during the stopover period? 4) Is long-distance movement of AIV likely by shorebirds migrating through Delaware Bay? Specifically, when do birds depart upon their next leg of migration and, in the context of infection dynamics, what proportion might be infected with AIV at the time of departure? The answers to the above questions would not only help describe AIV-shorebird-environment interactions in the context of local and global AIV epidemiology but would also inform conservation efforts for these declining shorebird populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

Delaware Bay is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, between the U.S. states of Delaware and New Jersey (38°47ʹ to 39°20ʹN, 74°50ʹ to 75°30ʹW). Primary shorebird habitats on Delaware Bay include sandy beaches bordered by tidal Spartina spp. (cordgrass) salt marshes and interspersed by small beachfront communities. Additionally, large tracts of tidal salt marsh are on the adjacent Cape May peninsula behind populated barrier islands along the Atlantic Ocean. Within this ecosystem, the Delaware Bay beaches support the greatest concentrations of migrating shorebirds including red knots, ruddy turnstones, sanderlings, and semipalmated sandpipers while tidal mudflats and marshes support higher numbers of certain species (short-billed dowitchers, least sandpipers [Calidris minutilla], semipalmated plovers [Charadrius semipalmatus], and black-bellied plovers [Pluvialis squatarola]) (8). The Atlantic coastal tidal saltwater marshes also support large breeding colonies of laughing gulls and herring gulls, smaller numbers of great black-backed gulls (Larus marinus), and rookeries of mixed herons, egrets, and ibises.

Field and laboratory methods.

This research was conducted under University of Georgia Animal Care and Use Committee approval. Scientific collection permits were provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC), and the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife (NJDEP).

Field work was conducted during May–early June, 2007–2008. Shorebirds were captured with cannon nets on Delaware Bay beaches by experienced personnel for inclusion into ongoing, long-term population studies. Each bird included in this long-term study was fitted with a numbered metal U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service band, a lime green Darvic color band, and a lime green laser-inscribed plastic leg flag containing a unique 3-digit alphanumeric code (10). Following banding and body measurements, cloacal swab samples were collected, stored, processed, and tested by virus isolation in embryonated chicken eggs as previously described (20). The presence of AIV in allantoic fluid was confirmed by hemagglutination and reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) for the matrix gene (49,52).

Radiotelemetry methods.

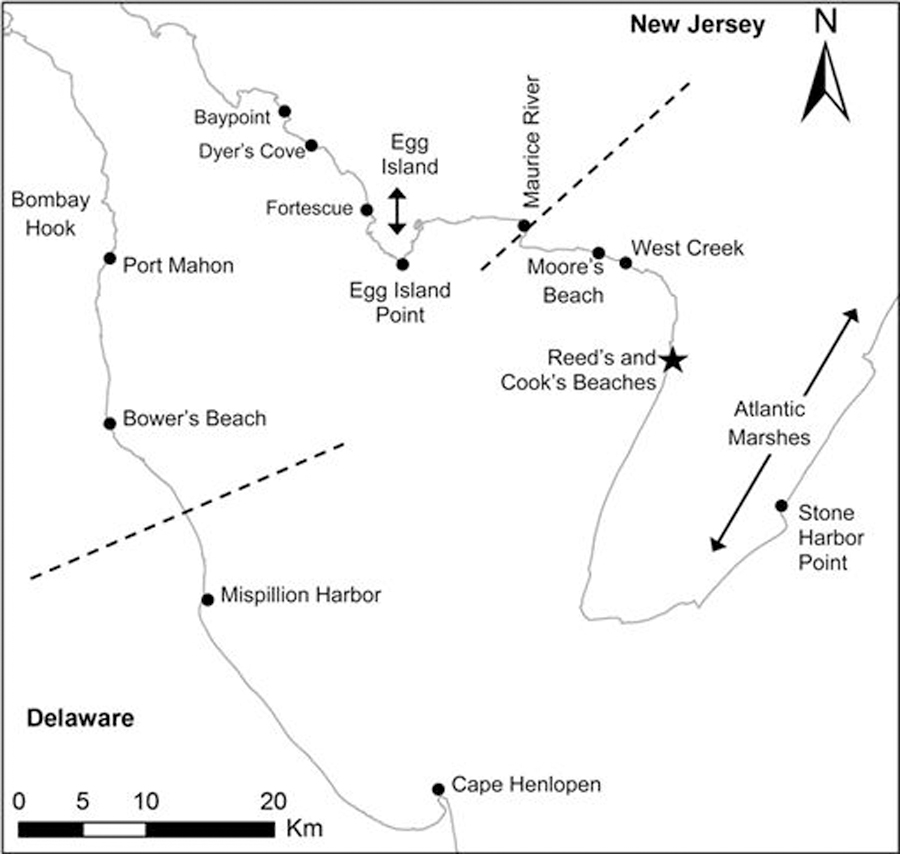

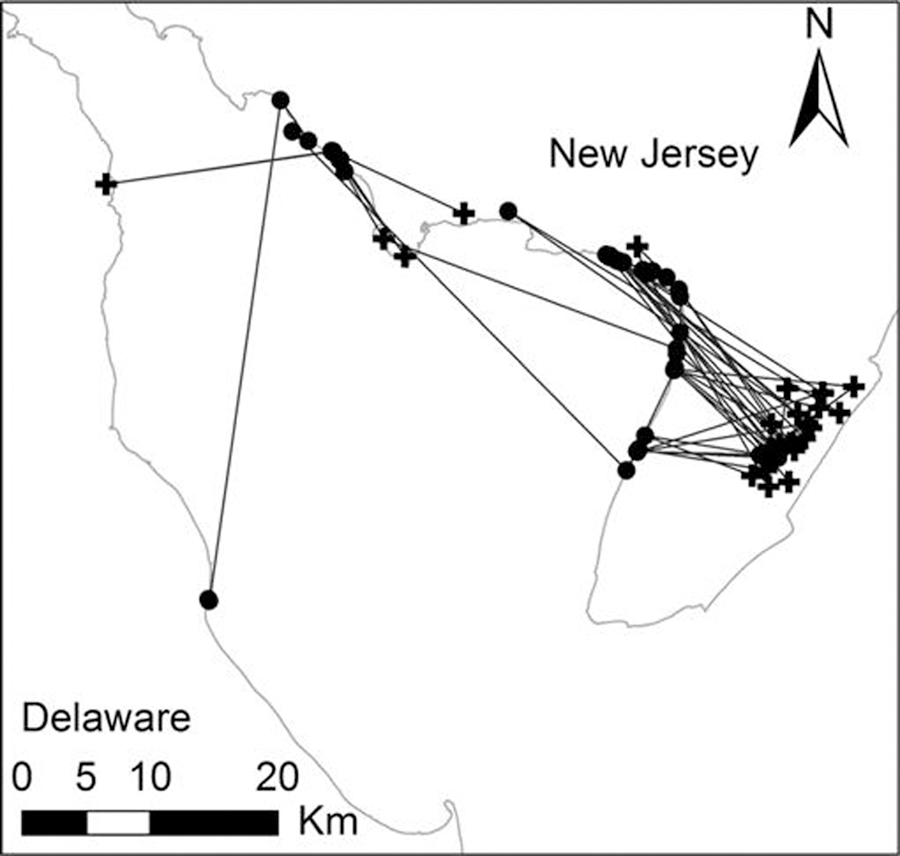

Sixty ruddy turnstones and 20 sanderlings were fitted with back-mounted radiotransmitters (Model BD2, Holohil Systems Ltd., Ontario, Canada) that weighed, on average, 1.6% and 1.9% of body mass for ruddy turnstones and sanderlings, respectively (transmitters weighed 1.6 g and 1.2 g for ruddy turnstones and sanderlings, respectively). Each individual transmitter weighed < 2.3% of the bird’s body weight. We attached radiotags by snipping a 1 × 2-cm patch of feathers close to the skin over the synsacrum and used cyanoacrylate glue gel to secure the package directly to the skin, allowing the antenna to lie freely over the tail. Six groups of 10 ruddy turnstones each and four groups of five sanderlings each were radiotagged at adjacent Reed’s and Cook’s beaches on the New Jersey shore of Delaware Bay (Fig. 1). Ruddy turnstones were radiotagged on May 10, 14, and 21, 2007 and on May 7, 13, and 16, 2008. Sanderlings were tagged on May 10, 13, 17, and 18, 2008. Note that both species were radiotagged at the same capture event on May 13, 2008.

Fig. 1.

Map of Delaware Bay labeled with locations mentioned in the text. State outlines are in gray. Dashed lines indicate the division between upper and lower areas of each state. The location of capture is indicated by a star.

We attempted to locate each radiotagged bird each day and night as weather permitted. We used handheld receivers (Model R4000, ATS Inc., Isanti, MN) and 3-element yagi antennae to search for and triangulate signals on the ground. Aerial telemetry was conducted every 2–3 days and, whenever possible, we paired a daytime flight with a nighttime flight on the same date. A 2-element H-antenna was attached to each wing of a Cessna 172 airplane, and two observers each surveyed a separate set of frequencies. We flew at 120–135 km/hr at 150–200 m altitude along the entire shoreline of the Delaware Bay and also flew transects over large expanses of tidal marsh (e.g., along the New Jersey Atlantic coast). Locations were recorded as the position of the airplane when a given radio signal was loudest. Nine daytime and six nighttime flights were conducted during May 13–June 2, 2007, and 10 daytime and 6 nighttime flights were performed during May 11–June 5, 2008.

Additionally, teams of experienced observers scanned shorebird flocks using spotting scopes for marked individuals around Delaware Bay. Scanners concentrated their efforts on beaches where the largest numbers of birds congregated, enabling a large proportion of marked individuals to be seen (18). Resighting data and morphometric (e.g., mass, culmen length) and demographic (e.g., sex, age) data recorded at the time of capture were obtained from the Shorebird Resighting Database (http://www.bandedbirds.org). A body size index (BSI) was computed using principal components analysis to reduce multicollinearity of three morphology measurements (culmen length, combined head and bill length, and flattened wing chord); BSI is the first principal component of these measurements. The unitless BSI is normally distributed around a population mean of zero, with negative BSI indicating smaller body size and positive BSI indicating larger body size. Because birds are undergoing rapid mass gain during the short stopover period, a mass index (MI), in grams, was calculated to obtain an individual’s mass relative to the expected mass of the population on a given day and year (38). The MI is the unstandardized residual of a regression of mass on day, by individual years, using 5-node knotted spline effect of day in standard least-squares regression to obtain maximum fit for population mass gain (34). A positive MI value indicates that a bird was heavier than expected.

Data analyses.

Geographic information systems (GIS).

Each bird location was plotted in Google Earth (v. 5.2.1, Google Inc., Mountain View, CA) and then transferred into ArcGIS 9.2 (ESRI, Redlands, CA). Base layer and topographic feature shapefiles were obtained from Delaware DataMIL (http://datamil.delaware.org/) and the NJDEP Bureau of Geographic Information Systems (http://www.state.nj.us/dep/gis/). Only one location was retained per individual bird within the same daylight category (daytime or nighttime, as determined by civil sunrise and sunset) on a given calendar date. The Moran I statistic was used to test whether various point attributes (e.g., species, year, daylight category, or individual bird) clustered within the distribution of telemetry locations.

Use areas.

Using only data obtained from aerial tracking to minimize bias relating to detection probability, 75% kernel density home range estimates were calculated using Hawth’s Tools add-in to ArcGIS (http://www.spatialecology.com) for each combination of species, year, and daylight category. A smoothing parameter of 5000 was used. Overlap between use areas was calculated using ArcGIS.

Resource selection.

Using ArcGIS, areal habitat was reclassified from 2007 land-use–land-cover shapefiles into 11 general habitat types: beach, barren-altered land, agriculture, shrubland, forest, wooded wetland, open water, freshwater wetland, urban, residential, and salt marsh. Additionally, because of our interest in shorebird locations in relation to poultry production locations, concentrated animal feeding operations (CFOs) were classified separately from other agriculture and included as a 12th habitat class, although they comprised a tiny proportion (<0.2%) of the landscape within 30 km of Delaware Bay. The vast majority of these CFOs are poultry operations, particularly for broiler production (54). Detailed information regarding the location of other types of poultry holdings (e.g., backyard or free-range flocks) was not available. Distance from each bird location to the nearest other features (stream, road, shoreline, and to each of the 12 habitat types) was measured. Measurements were repeated on 1000 random points generated within the area covered by the flight transects (conservatively estimated to be the ground area within 3.2 km perpendicular to the aircraft’s approximate flight line). Because point-to-feature distances were not normally distributed, relationships between used vs. available status and the distance to habitat and landscape feature variables were characterized by nonparametric univariate analyses using PROC NPAR1WAY in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The 2-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine if the distribution of distances to each feature or habitat type were the same between bird locations and random locations, and the Wilcoxon test was used to compare central tendency, i.e., whether bird locations were located closer or further from each feature or habitat than were random locations. These tests were also used to compare resource selection between species.

Proximity to agriculture and poultry production areas.

In addition to the proximity tests applied to agriculture and CFO habitats (described above), minimum convex polygons (MCP) were calculated from all available shorebird location data and compared to CFO locations.

Movements.

Four quadrants were defined as follows: Lower New Jersey, locations south and southeast of the Maurice River including all locations along and near the Atlantic coast; Upper New Jersey, points north and west of the Maurice River; Lower Delaware, locations south and east of Big Stone Beach; and Upper Delaware, locations north and west of Big Stone Beach (Fig. 1). We examined whether birds moved between quadrants or crossed the Bay and the first dates they were recorded in a new quadrant or in Delaware. The MCP of each individual bird was compared to MCPs produced by 100 “random walks,” with the number of locations obtained for that bird and across the range of distances between successive locations, using Hawth’s Tools. Movement was considered nonrandom if the area of bird MCPs was smaller than the area of ≥ 95% of MCPs produced by random walks.

Departure dates.

Departures were analyzed by product-limit (i.e., Kaplan-Meier [25]) survival analysis, where departure from Delaware Bay represents “failures.” Departure dates were defined as the last date each bird was detected by resighting or radiotelemetry by ground or air. When a bird was last detected at night, it was given an additional half-day increment (e.g., May 28.5). It was presumed that the radiotransmitter became dislodged or nonfunctional when individual radio signals were not detected after May 20; the last dates these birds were detected were right-censored in the analyses. Likewise, birds that were detected on the last day of tracking (June 3, 2007 and June 5, 2008) were right-censored because they were still present at the conclusion of the study. Using log-rank analysis (46), distributions of departure dates were compared between years in ruddy turnstones. Because departure rates were not proportional over time between ruddy turnstones and sanderlings, the assumption of proportional hazards was violated (11) and the distribution of departure dates could not be compared statistically between species. Within each year-species combination, departure dates were further compared by date of capture, sex (male or female; birds of unknown sex were excluded), raw body mass (in 10-g classes), BSI (in classes by the number of standard deviations [SD] above or below zero), MI (in 10-g classes above or below expected mass), and AIV infection status (positive or negative) recorded at the time of capture. The latter comparison included 2008 ruddy turnstone data only because no ruddy turnstones (nor any sanderlings) tagged in 2007 were AIV positive. Proportions of birds remaining at Delaware Bay over time were estimated for each group using the log-normal distribution.

Computations and statistical analyses not performed in ArcGIS were carried out in SAS version 9.2 or JMP version 8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 1355 bird locations were obtained from ground and aerial telemetry, capture data, and resightings of radiotagged birds (n = 1089 ruddy turnstone locations, n = 226 sanderling locations). In 2007 and 2008, respectively, ruddy turnstones were tracked for medians of 17 (range: 5.5–22) and 20 (range: 2.5–29) days. Sanderlings were tracked for a median of 16 (range: 5–26) days in 2008. Individual ruddy turnstones in 2007 and 2008 and sanderlings in 2008 were located on a median of 10, 12, and 10 days (range: 3–23) and 6, 7, and 3 nights (range: 0–15), respectively. The total number of locations per bird ranged from 4–36.

Seven hundred thirty-seven of the 1335 locations were determined by aerial telemetry (n = 563 ruddy turnstone locations and n = 174 sanderling locations). Individual birds were located a median of nine (range: 1–15) times by aerial telemetry or on a median of six (range: 1–9) daytime flights and three (range: 0–6) nighttime flights.

Morphometic and demographic characteristics of radiotagged birds are summarized in Table 1. Among radiotagged ruddy turnstones, BSI was significantly larger in 2007 than in 2008 (t58 = 2.1, P = 0.038; there is no clear explanation for this finding); all other measures were equivalent between years (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of radiotagged ruddy turnstones and sanderlings at Delaware Bay, 2007–2008, by species and year.

| Percent (n/total) |

Mean (range) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Year | n tagged | AIV positive | Recaptured birds | Female | Weight (g) | Body size index (BSI) | Mass index (MI) (g) |

| Ruddy turnstone | 2007 | 30 | 0 (0/30) | 3.3 (1/30) | 33 (10/30) | 106.6 (79–125) | 0.60 (−1.31–3.28) | −4.66 (−48.40–16.34) |

| Ruddy turnstone | 2008 | 30 | 17 (5/29)A | 13 (4/30) | 43 (12/28)B | 99.5 (81–121) | −0.12 (−2.79–2.68) | −1.08 (−17.29–18.33) |

| Sanderling | 2008 | 20 | 0 (0/14)A | 16 (3/19)C | n/aD | 63.7 (52–84) | −0.53 (−2.75–1.49) | 1.44 (−10.38–20.62) |

One ruddy turnstone and six sanderlings were not tested for AIV in 2008.

Excludes two birds of unknown sex.

Morphometric and demographic data were not recorded for one sanderling.

Sex could not be determined.

Avian influenza virology.

At the time of capture, all 30 tagged ruddy turnstones were AIV-negative in 2007 (Table 1). In 2008, five of 29 tagged turnstones were AIV-positive (17%; one bird not tested). Prevalence at the time of capture increased with capture date (logistic regression; χ21 = 6.9, P = 0.009) and was 0% (0/10), 11% (1/9), and 40% (4/10) among birds captured on May 7, 13, and 16, 2008, respectively. All subtypes were of low pathogenicity (H6N8 [n = 1], H10N7 [n = 1], and H12N5 [n = 3]). All 14 sanderlings tested were negative for AIV, including those captured alongside infected ruddy turnstones on May 13, 2008.

Use areas and habitat use.

Figure 2 illustrates the areas used by ruddy turnstones and sanderlings during the daytime and nighttime. Throughout the study, both species primarily used Delaware Bay beaches during the daytime, particularly along the lower New Jersey Bay shore, from Fortescue to Baypoint in New Jersey, and a few discrete locations in Delaware (Port Mahon, Bower’s Beach, and Mispillion Harbor). During 2008, strong westerly winds caused a large focus of horseshoe crab spawning at Moore’s Beach and nearby locations (NJDEP, unpubl. data); hence, this area was used more heavily in 2008 as compared to 2007. Not surprisingly, due to their common diet of horseshoe crab eggs, sanderlings and ruddy turnstones used similar stretches of Delaware Bay beaches in 2008. The daytime use areas, defined by 75% kernel density contours, overlapped by 64% between species. However, daytime locations clustered by species (Moran I = 0.16, Z = 2.37, P = 0.018).

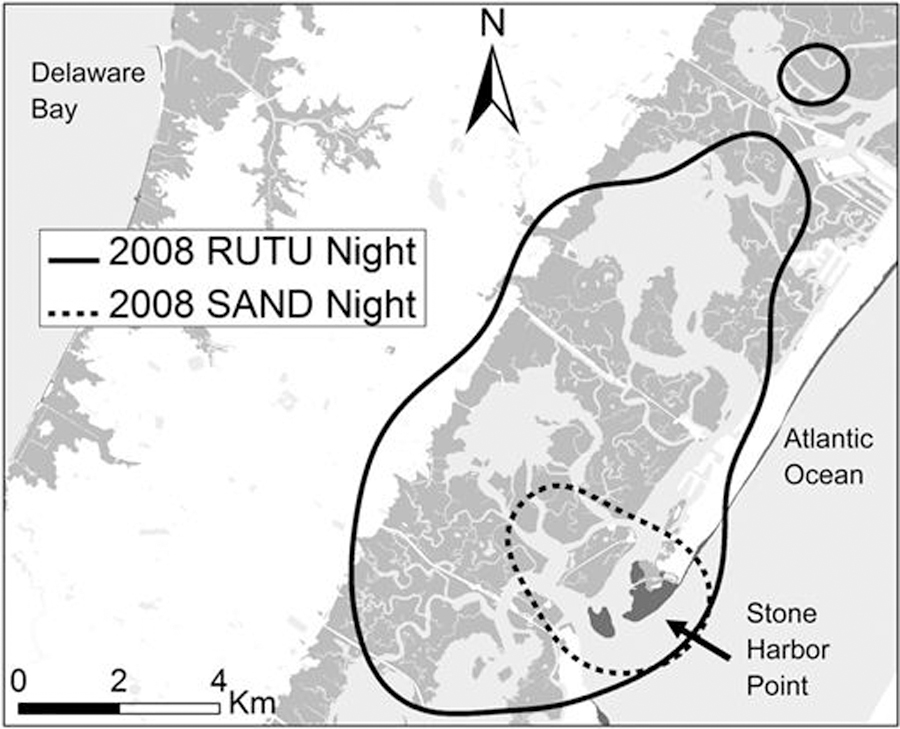

Fig. 2.

Daytime (solid lines) and nighttime (dashed lines) 75% kernel density contours for (A) ruddy turnstones in 2007, (B) ruddy turnstones in 2008, and (C) sanderlings in 2008 during spring migration stopover at Delaware Bay. State outlines and tidal salt marsh habitat are shaded gray.

For both species, areas used during the nighttime were significantly different than those used during the daytime (ruddy turnstone: Moran I = 0.49, Z = 4.08, P < 0.0001; sanderling: Moran I = 0.76, Z = 9.63, P < 0.0001). During nighttime, ruddy turnstones primarily used areas of expansive salt marsh, particularly along the barrier islands of the Atlantic Ocean in the Cape May Peninsula (hereafter, Atlantic marshes), Egg Island and restored former salt hay farms (2,21) just west of the Maurice River in Upper New Jersey, and Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware. Two birds also roosted on stone breakwaters off Cape Henlopen, Delaware. In 2008, salt marshes surrounding West Creek were heavily used by turnstones while Bombay Hook was used relatively infrequently (Fig. 2). Turnstone nighttime locations clustered by year (Moran I = 0.09, Z = 3.44, P = 0.0006) but daytime locations did not (Moran I = −0.02, Z = −0.29, P = 0.772). Sanderlings used a small number of locations at nighttime including Stone Harbor Point, Egg Island Point, Dyer’s Cove, Mispillion Harbor, and several sandy points and mudflats near West Creek and Moore’s Beach. Although ruddy turnstones also roosted on sandy points such as Stone Harbor Point, they roosted more often in the nearby salt marshes (Fig. 3). Nighttime use areas overlapped by only 20% between species. Nighttime locations clustered strongly by species (Moran I = 1.06, Z = 18.34, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Close-up of nighttime use areas of ruddy turnstones and sanderlings on Cape May Peninsula, New Jersey. Open water is shaded light gray, salt marsh habitat is medium gray, and beaches are dark gray. Other habitats are unshaded.

Table 2 lists the proportion of aerial telemetry locations within each habitat for each species and daylight class as well as the proportion of randomly selected points in each habitat. During daytime for both species, a majority of bird locations were on beaches. Both species also used salt marsh. For both species >25% of locations were in open water, probably because of both location inaccuracy and the species use of tidal habitats, which by definition are often covered by water. Ninety-nine percent of points in open water were within 200 m of either salt marsh or beach habitat. Points located in residential areas invariably were in beachfront communities, likely due to bird use of beaches surrounding and under houses. The distribution of habitats in which daytime aerial telemetry points were located was similar between species and between years among ruddy turnstones. However, nighttime locations revealed markedly different habitat use between species. While >80% of ruddy turnstone nighttime locations were in salt marsh, only 26% of sanderling locations were in salt marsh. Likewise, >70% of sanderling nighttime locations were in beach or open water and <20% of ruddy turnstone locations were in these habitats. The distribution of terrestrial habitats in which aerial telemetry points were located was markedly different than the underlying distribution of random points on the landscape for both species in both daylight classes (Table 2). Excluding telemetry locations in open water, the distribution of locations in habitats differed from the underlying (i.e., random) distribution for all species-year-daylight classes (Kolomogorov-Smirnov 2-sample test, all P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Distribution of habitats in which aerial telemetry points (ruddy turnstones and sanderlings) and GIS-generated random points were located.

|

n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 |

2008 |

|||

| Habitat | Ruddy turnstone | Ruddy turnstone | Sanderling | Random points |

| Day locations | ||||

| Salt Marsh | 42 (25) | 34 (17) | 16 (14) | 477 (48) |

| Agriculture | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 147 (15) |

| Wooded Wetland | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) | 103 (10) |

| Forest | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 67 (6.7) |

| Residential | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 66 (6.6) |

| Urban | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 53 (5.3) |

| Freshwater Wetland | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (3.1) |

| Beach | 78 (46) | 70 (36) | 60 (52) | 18 (1.8) |

| Shrubland | 3 (1.8) | 12 (6.1) | 5 (4.3) | 16 (1.6) |

| Barren-Altered Land | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.1) |

| Recreation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.1) |

| Open Water | 42 (25) | 77 (39) | 33 (28) | 0 (0)A |

| Night locations | ||||

| Salt Marsh | 69 (82) | 92 (81) | 15 (26) | 477 (48) |

| Agriculture | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 147 (15) |

| Wooded Wetland | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 103 (10) |

| Forest | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 67 (6.7) |

| Residential | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 66 (6.6) |

| Urban | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 53 (5.3) |

| Freshwater Wetland | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (3.1) |

| Beach | 1 (1.2) | 3 (2.6) | 10 (17) | 18 (1.8) |

| Shrubland | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 16 (1.6) |

| Barren-Altered Land | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.1) |

| Recreation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.1) |

| Open Water | 10 (12) | 19 (17) | 31 (53) | 0 (0)A |

Random points were excluded from location in open water.

Likewise, the distribution of distances from each aerial telemetry point to the nearest block of habitat (e.g., agriculture, beach, forest) or landscape feature (e.g., road, stream, shoreline) varied from the expected distribution (i.e., the distribution of distances from random points to each habitat or feature) for every habitat-species-daylight class combination (Kolomogorov-Smirnov 2-sample tests, all P < 0.05). During daytime, ruddy turnstone locations were further from agriculture, CFOs, forest, freshwater wetlands, wooded wetlands, and urban areas and nearer to beaches, recreational areas, streams, and shoreline than to random points. During nighttime, they were further from agriculture, barren-altered land, CFOs, forest, freshwater wetlands, wooded wetlands, residential and urban areas, and roads, and nearer to salt marsh and streams than to random points. During daytime, sanderlings were located nearer to beaches, recreational areas, residential areas, streams, and shoreline and further from agriculture, CFOs, forest, freshwater wetlands, urban areas, and wooded wetlands than from random locations. During nighttime, they were closer to beaches, streams, and shoreline and further from agriculture, barren-altered lands, CFOs forest, freshwater wetlands, recreational lands, residential and urban areas, wooded wetlands, and roads than from random points (Wilcoxon tests, all P < 0.05).

Although median distances to habitats and features were similar between ruddy turnstones and sanderlings during daytime, these differed during nighttime for every habitat and feature except for distance to urban and wooded wetland habitats and to streams (Table 3). During the daytime, turnstones were significantly closer to salt marsh and farther from beach and wooded wetland habitats than were sanderlings. During the nighttime, ruddy turnstones were significantly closer to barren-altered land, freshwater wetland, recreational and residential areas, salt marsh, and roads than were sanderlings and significantly further from agriculture, CFOs, beaches, forest, shrubland, and the shoreline than were sanderlings (Table 3).

Table 3.

Between-species comparison of distances from aerial telemetry locations to various habitat classes and features, by daylight class. Asymptotic (2-sample) Kolomogorov-Smirnoff statistics (KSa) test whether the distributions are the same whereas Wilcoxon Z tests compare central tendency. Positive Z values indicate that sanderling locations tended to be further from the habitat or feature than were ruddy turnstone locations. P-values of significant tests are bolded.

| Day |

Night |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon |

Wilcoxon |

|||||||

| Habitat-feature | KSa | P-value | Z | P-value | KSa | P-value | Z | P-value |

| Agriculture | 1.27 | 0.079 | −1.66 | 0.097 | 2.96 | <0.0001 | −3.38 | 0.0007 |

| Barren-Altered Land | 0.84 | 0.481 | −0.39 | 0.698 | 3.46 | <0.0001 | 5.71 | <0.0001 |

| Beach | 1.09 | 0.0003 | −3.95 | <0.0001 | 3.87 | <0.0001 | −6.52 | <0.0001 |

| CFO | 0.95 | 0.329 | −0.39 | 0.699 | 3.83 | <0.0001 | −5.63 | <0.0001 |

| Forest | 0.75 | 0.626 | −1.45 | 0.145 | 1.94 | 0.001 | −3.72 | 0.0002 |

| Freshwater Wetland | 1.04 | 0.233 | 0.11 | 0.913 | 2.90 | <0.0001 | 2.40 | 0.016 |

| Recreation | 1.21 | 0.108 | 1.61 | 0.108 | 3.56 | <0.0001 | 6.02 | <0.0001 |

| Residential | 1.16 | 0.137 | −1.60 | 0.109 | 2.12 | 0.0002 | 3.06 | 0.002 |

| Salt Marsh | 1.27 | 0.080 | 2.12 | 0.034 | 3.13 | <0.0001 | 6.79 | <0.0001 |

| Shrubland | 0.84 | 0.486 | −0.40 | 0.692 | 3.24 | <0.0001 | −7.30 | <0.0001 |

| Urban | 0.98 | 0.290 | 0.97 | 0.332 | 1.21 | 0.105 | −0.02 | 0.402 |

| Wooded Wetland | 1.64 | 0.009 | −2.41 | 0.016 | 0.72 | 0.684 | 0.72 | 0.469 |

| Roads | 0.95 | 0.323 | −0.54 | 0.589 | 1.96 | 0.0009 | 3.37 | 0.0007 |

| Streams | 1.08 | 0.190 | 1.51 | 0.130 | 0.52 | 0.947 | −0.55 | 0.582 |

| Shoreline | 1.02 | 0.246 | −1.23 | 0.218 | 4.31 | <0.0001 | −8.47 | <0.0001 |

Proximity to landscape and habitat features did not differ between ruddy turnstones that were shedding or not shedding AIV at the time of capture (all P > 0.05), except that birds which were shedding AIV were located further from barren-altered lands than were birds that were not shedding AIV (median 2.5 vs. 1.9 km for negative birds; Wilcoxon Z = 2.20, P = 0.028).

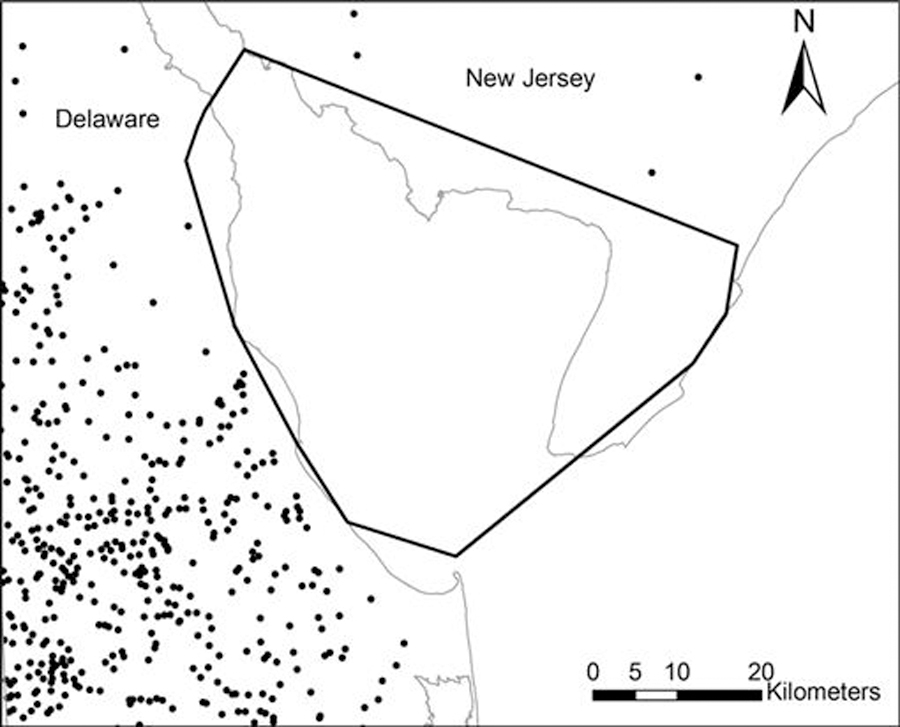

Proximity of ruddy turnstones to areas used for poultry production.

Compared to random locations, ruddy turnstone locations were further from both agriculture in general (median 1.9 vs. 0.6 km; Wilcoxon Z = 20.87, P < 0.0001) and CFOs in specific (median 14.7 vs. 9.6 km; Wilcoxon Z = 10.30, P < 0.0001). Nighttime ruddy turnstone locations were significantly further from both agriculture and CFOs than were daytime locations (median 2.9 vs. 1.8 km, Wilcoxon Z = 11.05, P < 0.0001; median 19.7 vs. 13.2 km, Wilcoxon Z = 9.10, P < 0.0001, respectively). Ruddy turnstones were located closer to CFOs when they were in Delaware compared to New Jersey (median 6.7 vs. 15.7 km; Wilcoxon Z = −11.6, P < 0.0001). The minimum distance between any ruddy turnstone location and the nearest CFO was 3.2 km. No CFOs were located within the MCP created by all bird locations (Fig. 4). The shortest distance between a CFO and the edge of the MCP was 1.7 km.

Fig. 4.

Location of concentrated animal feeding operations (CFOs, black dots) in relation to the area used by shorebirds at Delaware Bay. The heavy black line represents the minimum convex polygon (MCP) created by all radio telemetry locations of sanderlings and ruddy turnstones in 2007 and 2008. Note that no CFOs fell within the MCP. State outlines are shown in gray.

Ruddy turnstone movements.

Ruddy turnstones moved nonrandomly on the landscape (all MCPs smaller than the >95% of those produced by random walks) but apparently moved independently of each other even when captured together. In each year, locations of individual birds were randomly distributed within the distribution of all aerial telemetry locations (2007: Moran I = 0.08, Z = 1.08, P = 0.280; 2008: Moran I = −0.12, Z = −0.97, P = 0.332).

In 2007, 23 (77%) ruddy turnstones moved away from lower New Jersey and 14 (47%) crossed Delaware Bay at least once. In 2008, these numbers were 17 (57%) and 8 (27%), respectively. The proportion of birds moving away from lower New Jersey and crossing Delaware Bay did not differ between years (Fisher exact test; P = 0.170 and P = 0.180, respectively). In 2007, 36% (5/14) of birds that crossed the Bay crossed back into New Jersey. In 2008, 63% (5/8) crossed back; this difference between years is not significant (Fisher exact test, P = 0.443).

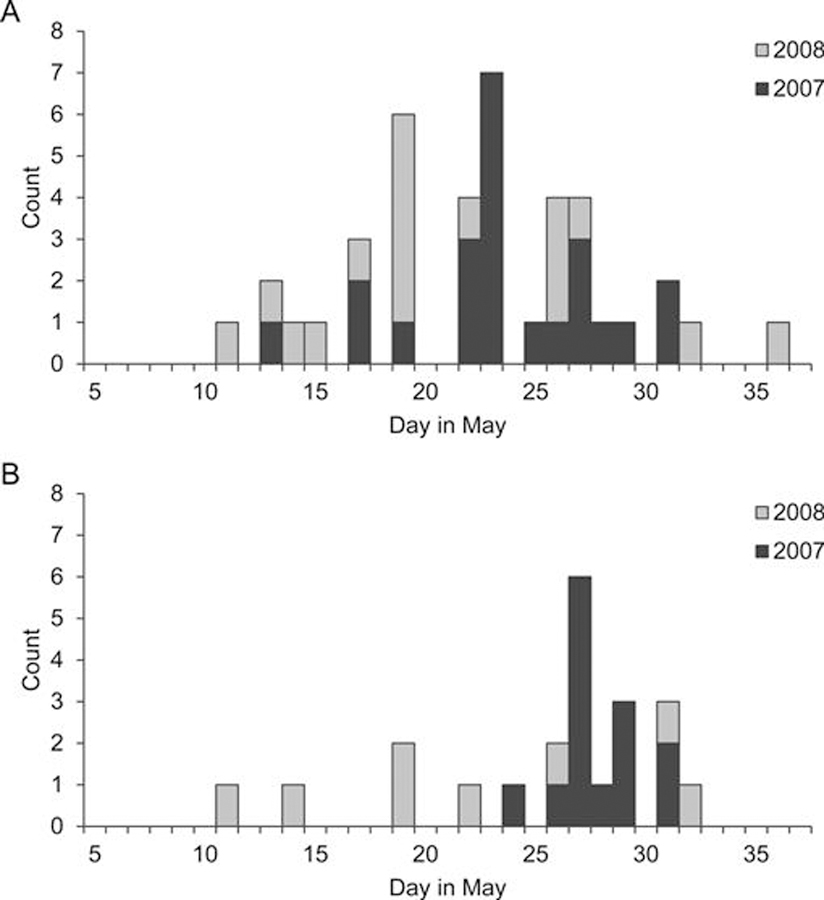

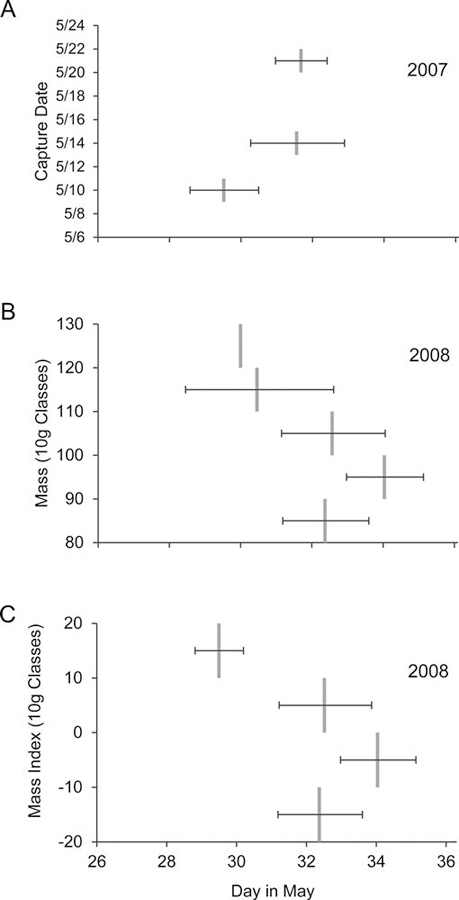

Turnstones that moved away from lower New Jersey were first detected elsewhere a median of 9 (2007) and 7 (2008) days from date of capture (range: 0–20 days). They were first detected in Delaware a median of 13 and 9.5 days after capture in 2007 and 2008, respectively (range: 3–24 days). The median dates a bird was first detected elsewhere were May 23, 2007 (range: May 13–31) and May 19, 2008 (range May 11–June 5), and the median dates on which a bird was first detected in Delaware were May 27, 2007 (range: May 24–31) and May 20, 2008 (range: May 11–June 1; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of dates on which ruddy turnstones were first detected (A) outside of lower New Jersey and (B) in Delaware.

Using data from individual birds only when daytime and nighttime flights were paired (n = 113), median distance moved from daytime to nighttime locations was 11.2 km (range: 0.2–58.1 km). Ninety percent of nighttime locations were ≤22.7 km from the corresponding daytime location. Distance moved did not vary between years (Wilcoxon Z = −0.39, P = 0.694) or by date (Kruskal-Wallis χ22 = 7.63, P = 0.471). Rarely did birds cross the Bay; in only five (4%) instances did ruddy turnstones cross the Bay between daytime and nighttime locations; three from upper New Jersey beaches to Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge and two from beaches in Delaware to West Creek and the Atlantic marshes, respectively.

Among the five ruddy turnstones that were shedding AIV at the time of capture, three (60%) moved away from lower New Jersey and two (40%) crossed the Bay. These two birds were first detected in Delaware on May 22 and June 1, 2008, or 6 and 19 days after capture, respectively. Median distance moved between daytime and nighttime locations was 18.0 km (n = 11, range: 3.3–27.7 km); this was not different from birds that were not shedding AIV at the time of capture (Wilcoxon Z = 1.5, P = 0.129). Movement patterns of AIV-shedding birds are displayed in Figure 6. Movement patterns were similar between birds that were shedding AIV and those that were not, including during the first few days following capture (i.e., infection did not appear to alter movement habits).

Fig. 6.

Movements of five ruddy turnstones that were AIV-positive at the time of capture. Daytime locations are circles, nighttime locations are crosses.

Departure dates.

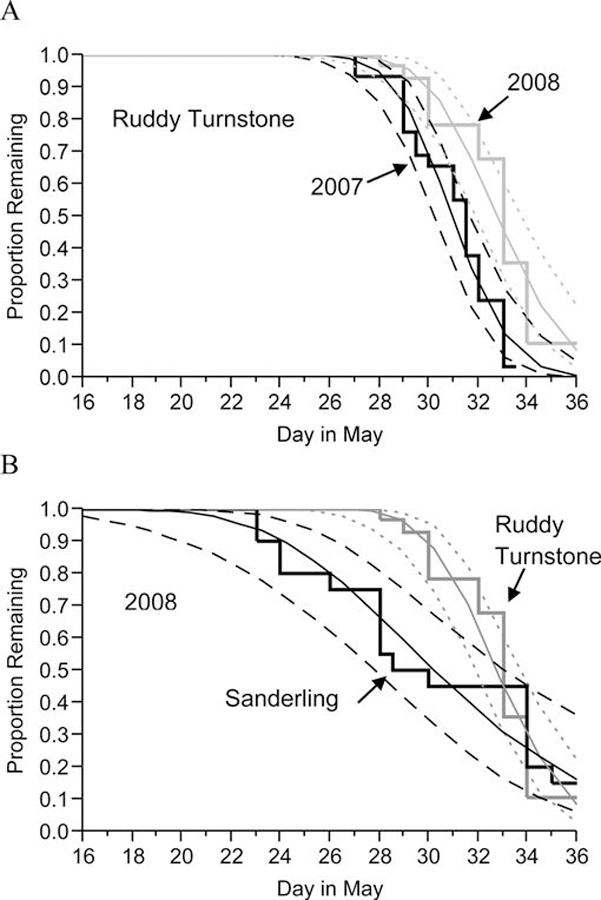

Table 4 lists, for each species-year combination, the median departure date and estimated dates on which 25%, 50%, and 75% of birds had departed. In ruddy turnstones, departure dates were distributed significantly later in 2008 than in 2007 (log-rank χ21 = 13.76, P = 0.0002; Fig. 7A). Estimated mean departure was nearly 2 days later in 2008; however, the span of time over which the middle 50% of ruddy turnstones departed remained approximately the same between years (2.5 days in 2007 and 3.0 days in 2008; Table 4). Departure dates differed with capture date in 2007 but not in 2008 (Table 5); birds from the earliest capture in 2007 (May 10) departed earlier than birds captured later (Fig. 8A). In 2008 but not in 2007, departure dates were different across 10-g mass classes and 10-g MI classes (Table 5); birds that were heaviest at the time of capture, either absolutely or relatively, departed earlier than did lighter birds (Fig. 8B and C). Departure dates in each year did not differ by sex or BSI (Table 5). There was no difference in departure dates between birds that were AIV positive at the time of capture and those that were negative (2008 data only, Table 5).

Table 4.

Timing of departure of radiotagged ruddy turnstones and sanderlings from Delaware Bay, 2007–2008. Days are measured as the number of days after April 30.

| Species | Year | n Tagged | n Right-censored | Observed median departure day | Log-normal fit estimates (95% CI)A |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% Departure day | 50% Departure day | 75% Departure day | |||||

| Ruddy Turnstone | 2007 | 30 | 2 | 31.25 | 29.7 (28.7–30.2) | 30.9 (30.3–31.6) | 32.2 (31.4–33.0) |

| Ruddy Turnstone | 2008 | 30 | 5 | 32.5 | 31.3 (30.4–32.2) | 32.8 (31.9–33.6) | 34.3 (33.5–35.3) |

| Sanderling | 2008 | 20 | 3 | 28.25 | 26.8 (24.6–29.2) | 30.2 (27.9–32.7) | 34.1 (31.1–37.4) |

Kaplan-Meier survival regression.

Fig. 7.

(A) The proportion of radiotagged ruddy turnstones remaining in Delaware Bay by day in May and year. (B) The proportion of ruddy turnstones and sanderlings remaining in Delaware Bay by day in May 2008. Shown are Kaplan-Meier survival curve lines of fit (95% CI) by lognormal regression.

Table 5.

Effects of capture date, sex, weight, body size index, mass index, and AIV infection status on springtime departure date of ruddy turnstones and sanderlings from Delaware Bay, by species and year, using the proportional hazards model. P-values of significant effects are bolded.

| Ruddy Turnstone 2007 |

Ruddy Turnstone 2008 |

Sanderling 2008 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Log-rank χ2 | df | P-value | n | Log-rank χ2 | df | P-value | n | Log-rank χ2 | df | P-value |

| Capture date | 30 | 8.4 | 2 | 0.015 | 30 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.917 | 20 | 3.5 | 3 | 0.316 |

| Sex | 30 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.194 | 28 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.755 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| WeightA | 30 | 5.4 | 5 | 0.375 | 30 | 12.1 | 4 | 0.016 | 19 | 12.5 | 3 | 0.006 |

| BSIB | 30 | 7.8 | 5 | 0.170 | 30 | 6.4 | 5 | 0.269 | 19 | 16.2 | 4 | 0.003 |

| MIA | 30 | 3.6 | 4 | 0.467 | 30 | 13.6 | 3 | 0.004 | 19 | 13.8 | 4 | 0.008 |

| AIV status | n/aC | n/a | n/a | n/a | 29 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.351 | n/aC | n/a | n/a | n/a |

By 10-g class.

By SD class.

No AIV were isolated from radiotagged ruddy turnstones in 2007 or from sanderlings in 2008.

Fig. 8.

Estimated mean departure date (95% CI) of radiotagged ruddy turnstones by (A) capture date in 2007, (B) mass class in 2008, and (C) MI class in 2008.

In sanderlings, heavier birds (both absolutely and relatively) departed earlier than did lighter birds (Table 5). Sanderlings (but not ruddy turnstones) with larger relative body size (BSI) departed earlier than did smaller birds (Table 5).

Figure 7B shows estimated departures of sanderlings and ruddy turnstones in 2008. The median departure date of sanderlings was May 28 compared to June 2 for ruddy turnstones (Table 4). Comparatively, sanderlings departed on a wider range of dates. The middle 50% of sanderlings departed during May 27–June 3 (7 days) while the same proportion of ruddy turnstones departed during May 31–June 3 (3 days).

DISCUSSION

Use areas, habitat use, and proximity to other AIV reservoir species.

Overlap of daytime use areas was substantial between species and between years in ruddy turnstones. Shorebirds using Delaware Bay during spring migration, including ruddy turnstones and sanderlings, rely heavily on horseshoe crab eggs for rapid weight gain (1). It is not surprising, then, that locations used by both species during the daytime historically have supported large numbers of spawning crabs (48) and high crab egg densities (3). Spatial distribution of red knots, a sympatric species, was also linked to the available number of horseshoe crab eggs (26). A period of sustained westerly winds in May 2008 resulted in lower numbers of spawning crabs along the relatively north-south aspect of the beaches along the New Jersey’s lower Delaware Bay (including Reed’s and Cook’s beaches) and higher numbers along the east-west aspect of lower Delaware Bay in New Jersey.

A key finding regarding habitat use of ruddy turnstones is that their primary nighttime roost locations are in expansive salt marsh habitat. These wetland areas are frequented by known AIV reservoir species including waterfowl (e.g., mallards [Anas platyrhynchos]) and gulls (laughing gulls, herring gulls) (47). In particular, the nighttime area used in the Atlantic marshes (Fig. 3) is home to the largest number of breeding laughing gull pairs on the eastern seaboard (6). The AIV subtypes isolated from shorebirds at Delaware Bay (20,29,51) have included subtypes normally associated with duck species (e.g., H3, H4, and H6) as well as those adapted to gulls (H13, H16) (43). Predominant AIV subtypes among ruddy turnstones during 2007–2008 were H4N6, H10N7, and H12N5; however, many other viral subtypes, including H5, H6, H7, H9, H11, H13, and H16 viruses, were detected (34,51). Because AIV infection is waterborne, it is possible that tidal marshes are an important source of AIV to which ruddy turnstones are exposed upon arrival at Delaware Bay. Although ruddy turnstones feed primarily on horseshoe crab eggs while at this stopover (53), they are known to take a variety of food items (17) including gull feces and eggs (4,28). Thus, gulls or their nesting habitat could be a source of AIV for turnstones.

Alternatively, this habitat could provide conditions appropriate for AIV transmission among ruddy turnstones. Because ruddy turnstones, red knots, and sanderlings share common feeding habitat during the daytime (Delaware Bay beaches) (7,8,9), and red knots and sanderlings have a very low AIV prevalence (20,34), perhaps differences in nighttime habitat use allow for variable transmission to and within each species. Sanderlings (and red knots; Sitters, unpubl. data) do not extensively share ruddy turnstone nighttime roost locations, instead preferring remote sandy points and islands. Beach sand might not be an effective medium for AIV transmission because frequent wave action possibly causes percolation of virus through the sand, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation and drying at the surface likely cause rapid inactivation of virus. Because AIV is efficiently transmitted through contaminated water (22), the tidal marshes with their standing water are perhaps a better medium for transmission, particularly at night when viruses are not inactivated by UV light. Although the length of time that AIV survives in water decreases with increasing salinity (5,50), survival of even a few days in saltwater could be sufficient for sustained transmission, especially when birds concentrate in large numbers on just a few identified nighttime roost areas. More study is necessary to discover the exact infection sources and transmission mechanisms of AIV within and among shorebirds, gulls, waterfowl, and other waterbirds at Delaware Bay.

Proximity to poultry production areas.

Transmission of AIV from wild birds to poultry species is a high concern for the agricultural industry, particularly the H5 and H7 subtypes capable of mutating into highly pathogenic forms. Low pathogenic subtypes H5 or H7 were detected in Delaware Bay shorebirds, including ruddy turnstones, in 5 of 6 yr during 2000–2005 (20), highlighting the need for excellent biosecurity in this context.

All ruddy turnstone locations were at least several kilometers from known CFOs, implying that direct contact does not occur between ruddy turnstones and (at least) the majority of commercial poultry premises. However, the locations of some small poultry holders (e.g., free-range or backyard flocks) that do not “look” like CFOs on aerial photography could not be determined. Although shorebirds were not detected in areas of larger commercial poultry production, we did not systematically search these areas by aerial or ground telemetry. Assuming that the ruddy turnstones in our study took the most direct route between locations, or at least flew along the shoreline, no CFOs were under their flight lines. However, small backyard flocks or free-range poultry were seen on the Cape May Peninsula during ground tracking; these were under the flight path of ruddy turnstones from their daytime feeding locations along the lower New Jersey beaches and their nighttime roost locations in the Atlantic marshes. While no transmissions of AIV from infected shorebirds to nearby domestic birds have been documented, small poultry holders should be educated about the risk of AIV transmission and all nearby domestic birds should be kept indoors during the shorebird stopover period. Further, potentially exposed domestic birds should not be transferred or sold at live bird markets until it’s certain they are free of infection.

Movement patterns.

A minority of ruddy turnstones crossed the Bay from New Jersey into Delaware; this finding is consistent with capture-resighting studies (DNREC and NJDEP, unpubl. data). Thus, ruddy turnstones were relatively faithful to a particular side of Delaware Bay; this species is also faithful to wintering sites (37,41). Predicted population AIV prevalence on the median day of bay crossing was 5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2%–11%) in 2007 and 20% (95% CI: 16%–25%) in 2008 (35). Peak prevalence occurs on about May 22–24 (35). Thus, potential exists for local movement of AIV by ruddy turnstones within the Delaware Bay ecosystem. However, cross-bay circulation of all strains present in a given year might be limited. For example, during May–June 2008, only four (22%) of 18 AIV subtypes isolated from ruddy turnstones were detected in both states, four (22%) were detected only in Delaware, and 10 (56%) were detected only in New Jersey (34). Although no increased mortality has been observed in ruddy turnstones naturally infected with LPAIV (36), limited cross-bay circulation could be advantageous to the population if a strain of higher virulence were introduced.

Departure dates and AIV prevalence.

Ruddy turnstones use Delaware Bay en route to breeding grounds in the low Arctic (40,45). Predicted AIV prevalence on ruddy turnstones’ median departure dates in 2007 and 2008 were 2% (95% CI: 0.5%–9%) and 16% (95% CI: 11%–23%), respectively (35). Thus, a small number of ruddy turnstones potentially could transport AIV from Delaware Bay toward the breeding grounds. However, it is possible that birds that became infected late in the stopover season, and thus were shedding virus during the period of peak departure, remained at Delaware Bay longer than did uninfected birds. Indeed, median departure date was about 2 days later in 2008, when AIV prevalence was high, than in 2007 when prevalence was much lower. Migration delays have been observed in AIV-infected mallards (33) and Bewick’s swans (Cygnus columbianus bewickii) (55) when compared to uninfected conspecifics. Alternatively, the observed migration delay could have been due to weather- or weight gain-related factors or a combination of factors. In 2008, birds that were shedding AIV at the time of capture (May 13–16) presumably recovered from infection before departure approximately 17–20 days later. No difference was observed in the departure dates between birds that were initially infected and uninfected, but birds might have become infected after they were radiotagged. Thus, it is unclear from our data if AIV infection influences departure from Delaware Bay or if ruddy turnstones transport virus toward the breeding grounds following departure.

Although some AIV isolates recovered from shorebirds show evidence of intercontinental exchange of entire virus or gene segments (29), most shorebird infections are thought to occur locally as spill-over events (44). Because ruddy turnstones typically disperse onto breeding grounds after departing Delaware Bay (41,45), where their densities are much lower and they primarily use upland habitats, transmission might not be sustained after leaving Delaware Bay. Indeed, AIV is detected rarely in ruddy turnstones outside of Delaware Bay.

Conservation aspects.

This study identified additional sites and habitats that are potentially critical to ruddy turnstones and sanderlings during their stopover at Delaware Bay. For example, it was previously unknown that ruddy turnstones used salt marshes extensively during the nighttime and sanderlings used mudflats and sandy points. The finding that relatively few nighttime congregation sites were used highlights the need for continued protection of these areas. Because these shorebirds were captured in one location and generally stayed in New Jersey, future study should include birds from other sites around Delaware Bay, especially Delaware, to help identify other critical nighttime roosting locations that were not visited by the birds in our study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded through Specific Cooperative Agreement 58-6612-2-0220 between the Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, Department of Agriculture and the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, under contract no. HHSN266200700007C. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Banding data and morphometric measurements are the property of the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, DNREC, and the Nongame and Endangered Species Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, NJDEP; we thank these agencies for granting access to these data. We are grateful to C. Minton, R. Veitch, and others whose knowledge of shorebird ecology helped guide this study. We thank S. Schweitzer (University of Georgia) and NJDEP for lending their radiotelemetry equipment and technical support to this study; we particularly thank W. Pitts (NJDEP). We are grateful to many people who provided field support, particularly E. Casey, L. Coffee, M. Cole, J. Cumbee, D. Downs, W. Hamrick, S. Keeler, G. Martin, S. McGraw, C. McKinnon, J. Murdock, and B. Wilcox. Jim Strong Aviation provided expert aviation service.

Abbreviations:

- AIV

avian influenza virus

- BSI

body size index

- CFOs

concentrated animal feeding operations

- CI

confidence interval

- DNREC

Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control

- GIS

geographic information systems

- LPAIV

low pathogenicity avian influenza virus

- MCP

minimum convex polygon

- MI

mass index

- NJDEP

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- UV

ultraviolet

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson PW, Baker AJ, Bennett KA, Clark NA, Clark JA, Cole KB, Dekinga A, Dey A, Gillings S, Gonzalez PM, Kalasz K, Minton CDT, Newton J, Niles LJ, Piersma T, Robinson RA, and Sitters HP. Rates of mass gain and energy deposition in red knot on their final spring staging site is both time- and condition-dependent. J. Appl. Ecol 44:885–895. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balletto JH, Heimbuch MV, and Mahoney HJ. Delaware Bay salt marsh restoration: mitigation for a power plant cooling water system in New Jersey, USA. Ecol. Eng 25:204–213. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botton ML, Loveland RE, and Jacobsen TR. Site selection by migratory shorebirds in Delaware Bay, and its relationship to beach characteristics and abundance of horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) eggs. Auk 111:605–616. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brearey D, and Hilden O. Nesting and egg predation by turnstones Arenaria interpres in larid colonies. Ornis. Scand 16:283–292. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JD, Goekjian G, Poulson R, Valeika S, and Stallknecht DE. Avian influenza virus in water: infectivity is dependent on pH, salinity and temperature. Vet. Microbiol 136:20–26. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger J Laughing gull (Larus atricilla). In: The Birds of North America Online, Poole A, Ed. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Species Account no. 225. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger J, Carlucci SA, Jeitner CW, and Niles L. Habitat choice, disturbance, and management of foraging shorebirds and gulls at a migratory stopover. J. Coastal Res 23:1159–1166. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger J, Niles L, and Clark KE. Importance of beach, mudflat and marsh habitats to migrant shorebirds on Delaware Bay. Biol. Conserv 79:283–292. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark KE, Niles LJ, and Burger J. Abundance and distribution of migrant shorebirds in Delaware Bay. Condor 95:694–705. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark NA, Gillings S, Baker AJ, Gonzalez PM, and Porter R. The production and use of permanently inscribed leg flags for waders. Wader Study Group Bull 108:38–41. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox DR, and Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Amico VL, Bertellotti M, Baker AJ, and Diaz LA. Exposure of red knots (Calidris canutus rufa) to select avian pathogens; Patagonia, Argentina. J. Wildl. Dis 43:794–797. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunne P, Sibley D, Sutton C, and Wander W. Aerial surveys in Delaware Bay: confirming an enormous spring staging area for shorebirds. Int. Wader Study Group Bull 35:32–33. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusek RJ, Bortner JB, DeLiberto TJ, Hoskins J, Franson JC, Bales BD, Yparraguirre D, Swafford SR, and Ip HS. Surveillance for high pathogenicity avian influenza virus in wild birds in the Pacific flyway of the United States, 2006–2007. Avian Dis 53:222–230. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escudero G, Munster VJ, Bertellotti M, and Edelaar P. Perpetuation of avian influenza in the Americas: examining the role of shorebirds in Patagonia. Auk 125:494–495. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO]. Wild birds and avian influenza: an introduction to applied field research and disease sampling techniques. FAO, Rome, Italy. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill RE What won’t turnstones eat? Brit. Birds 79:402–403. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillings S, Atkinson PW, Baker AJ, Bennett KA, Clark NA, Cole KB, Gonzalez PM, Kalasz KS, Minton CDT, Niles LJ, Porter RC, De Lima Serrano I, Sitters HP, Woods JL, and Shaffer TL. Staging behavior in red knot (Calidris canutus) in Delaware Bay: implications for monitoring mass and population size. Auk 126:54–63. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillings S, Atkinson PW, Bardsley SL, Clark NA, Love SE, Robinson RA, Stillman RA, and Weber RG. Shorebird predation of horseshoe crab eggs in Delaware Bay: species contrasts and availability constraints. J. Anim. Ecol 76:503–514. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson BA, Luttrell MP, Goekjian VH, Niles L, Swayne DE, Senne DA, and Stallknecht DE. Is the occurrence of avian influenza virus in Charadriiformes species and location dependent? J. Wildl. Dis 44:351–361. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinkle RL, and Mitsch WJ. Salt marsh vegetation recovery at salt hay farm wetland restoration sites on Delaware Bay. Ecol. Eng 25:240–251. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinshaw VS, Webster RG, and Turner B. Water-borne transmission of influenza A viruses. Intervirology 11:66–68. 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurt AC, Hansbro PM, Selleck P, Olsen B, Minton C, Hampson AW, and Barr IG. Isolation of avian influenza viruses from two different transhemispheric migratory shorebird species in Australia. Arch. Virol 151:2301–2309. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iverson SA, Takekawa JY, Schwarzbach S, Cardona CJ, Warnock N, Bishop MA, Schirato GA, Paroulek S, Ackerman JT, Ip H, and Boyce WM. Low prevalence of avian influenza virus in shorebirds on the Pacific coast of North America. Waterbirds 31:602–610. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan EL, and Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc 53:457–481. 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karpanty SM, Fraser JD, Berkson J, Niles LJ, Dey A, and Smith EP. Horseshoe crab eggs determine red knot distribution in Delaware Bay. J. Wildl. Manage 70:1704–1710. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawaoka Y, Chambers TM, Sladen WL, and Webster RG. Is the gene pool of influenza viruses in shorebirds and gulls different from that in wild ducks? Virology 163:247–250. 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King B Turnstone feeding on gull excrement. Brit. Birds 75:88. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krauss S, Obert CA, Franks J, Walker D, Jones K, Seiler P, Niles L, Pryor SP, Obenauer JC, Naeve CW, Widjaja L, Webby RJ, and Webster RG. Influenza in migratory birds and evidence of limited intercontinental virus exchange. PLOS Pathog 3:1684–1693. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krauss S, Stallknecht DE, Negovetich NJ, Niles LJ, Webby RJ, and Webster RG. Coincident ruddy turnstone migration and horseshoe crab spawning creates an ecological ‘hot spot’ for influenza viruses. Proc. Roy. Soc. B–Biol. Sci 277:3373–3379. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krauss S, Walker D, Pryor SP, Niles L, Li CH, Hinshaw VS, and Webster RG. Influenza A viruses of migrating wild aquatic birds in North America. Vector-Borne Zoonot. Dis 4:177–189. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langstaff IG, McKenzie JS, Stanislawek WL, Reed CEM, Poland R, and Cork SC. Surveillance for highly pathogenic avian influenza in migratory shorebirds at the terminus of the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. New Zeal. Vet. J 57:160–165. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latorre-Margalef N, Gunnarsson G, Munster VJ, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME, Elmberg J, Olsen B, Wallensten A, Haemig PD, Fransson T, Brudin L, and Waldenström J. Effects of influenza A virus infection on migrating mallard ducks. Proc. Roy. Soc. B–Biol. Sci 276:1029–1036. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maxted AM Avian influenza viruses in shorebird hosts at the Delaware Bay migratory stopover site: infection patterns and dynamics, host ecology, and population effects. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Georgia, Athens, GA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxted AM, Luttrell MP, Goekjian VH, Brown JD, Niles LJ, Dey AD, Kalasz KS, Swayne DE, and Stallknecht DE. Avian influenza virus infection dynamics in shorebird hosts. J. Wildl. Dis 48:322–334. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxted AM, Porter RR, Luttrell MP, Goekjian VH, Dey AD, Kalasz KS, Niles LJ, and Stallknecht DE. Annual survival of ruddy turnstones is not affected by natural infection with low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses. Avian Dis 56:567–573. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metcalfe NB, and Furness RW. Survival, winter population stability and site fidelity in the turnstone Arenaria interpres. Bird Study 32: 207–214. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison RIG, Davidson NC, and Wilson JR. Survival of the fattest body stores on migration and survival in red knots Calidris canutus islandica. J. Avian Biol 38:479–487. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munster VJ, Baas C, Lexmond P, Waldenstrom J, Wallensten A, Fransson T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Beyer WEP, Schutten M, Olsen B, Osterhaus A, and Fouchier RAM. Spatial, temporal, and species variation in prevalence of influenza A viruses in wild migratory birds. PLOS Pathog 3:630–638. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nettleship DN Breeding ecology of turnstones Arenaria interpres at Hazen Camp, Ellesmere Island, N.W.T. Ibis; 115:202–217. 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nettleship DN Ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres). In: The Birds of North America Online, Poole A, Ed. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Species Account no. 537. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niles LJ, Bart J, Sitters HP, Dey AD, Clark KE, Atkinson PW, Baker AJ, Bennett KA, Kalasz KS, Clark NA, Clark J, Gillings S, Gates AS, Gonzalez PM, Hernandez DE, Minton CDT, Morrison RIG, Porter RR, Ken Ross R, and Veitch CR. Effects of horseshoe crab harvest in Delaware Bay on red knots: are harvest restrictions working? Bioscience 59:153–164. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen B, Munster VJ, Wallensten A, Waldenstrom J, Osterhaus A, and Fouchier RAM. Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. Science 312:384–388. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce JM, Ramey AM, Ip HS, and Gill RE. Limited evidence of trans-hemispheric movement of avian influenza viruses among contemporary North American shorebird isolates. Virus Res 148:44–50. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins DE, Smith PA, and Gilchrist HG. The breeding ecology of ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres) in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Polar Rec 43:135–142. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peto R, and Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant procedures. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Met 135:185–207. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibley DA The birds of Cape May, 2nd ed. New Jersey Audubon Society’s Cape May Bird Observatory, Cape May, New Jersey. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith DR, Pooler PS, Swan BL, Michels SF, Hall WR, Himchak PJ, and Millard MJ. Spatial and temporal distribution of horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) spawning in Delaware Bay: implications for monitoring. Estuaries 25:115–125. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spackman E, and Suarez D. Type A influenza virus detection and quantitation by real-time RT-PCR. Method. Mol. Biol 436:19–26. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stallknecht DE, Kearney MT, Shane SM, and Zwank PJ. Effects of pH, temperature, and salinity on persistence of avian influenza viruses in water. Avian Dis 34:412–418. 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stallknecht DE, Luttrell MP, Poulson RL, Goekjian VH, Niles LJ, Dey AD, Krauss S, and Webster RG. Detection of avian influenza viruses from shorebirds: evaluation of surveillance and testing approaches. J. Wildl. Dis 48:382–393. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swayne DE, Senne DA, and Beard CW. Avian influenza. In: A laboratory manual for the isolation and identification of avian pathogens. Swayne DE, ed. American Association of Avian Pathologists, Kennett Square, PA. pp. 150–155. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsipoura N, and Burger J. Shorebird diet during spring migration stopover on Delaware Bay. Condor 101:635–644. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 54.U.S. Department of Agriculture. U.S. summary and state data. In: 2007 census of agriculture. 2009. pp. 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Gils JA, Munster VJ, Radersma R, Liefhebber D, Fouchier RA, and Klaassen M. Hampered foraging and migratory performance in swans infected with low-pathogenic avian influenza A virus. PLOS One 2:e184. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, and Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol. Rev 56:152–179. 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winker K, Spackman E, and Swayne DE. Rarity of influenza A virus in spring shorebirds, southern Alaska. Emerg. Infect. Dis 14:1314–1316. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]