Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are malignant tumors arising from the intrahepatic biliary tract. The pathogenesis of these tumors remains unknown. Although there is a marked global variation in prevalence, some recent studies have suggested an increase in mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in several regions of low endemicity. As the study of mortality trends may yield clues to possible etiological factors, we analyzed worldwide time trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies.

Methods

Annual age-standardized rates for individual countries were compiled for deaths from biliary tract malignancies using the WHO database. These data were used to analyze gender and site-specific trends in mortality rates.

Results

An increasing trend for mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was noted in most countries. The average estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) in mortality rates for males was 6.9 ± 1.5, and for females was 5.1 ± 1.0. Increased mortality rates were observed in all geographic regions. Within Europe, increases were higher in Western Europe than in Central or Northern Europe. In contrast, mortality rates for extrahepatic biliary tract malignancies showed a decreasing trend in most countries, with an overall average EAPC of -0.3 ± 0.4 for males, but -1.3 ± 0.4 for females.

Conclusions

There has been a marked global increase in mortality from intrahepatic, but not extra-hepatic, biliary tract malignancies.

Background

Biliary tract tumors have proven challenging to treat and manage due to their poor sensitivity to conventional therapies and our inability to prevent or to detect early tumor formation [1]. Furthermore, their etiology remains poorly understood. Within the biliary tract, tumors can arise from intrahepatic bile ducts (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma), extrahepatic bile ducts, or the gall bladder. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are highly prevalent in certain regions such as Thailand and Southeast Asia [2]. Because parasitic biliary tract infection is also endemic to these regions, liver fluke infection and chronic biliary tract inflammation have been identified as a strong risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma [3,4]. Nevertheless the precise etiology and pathogenesis of these tumors remain obscure [5].

We have recently reported an increase in intrahepatic, but not extrahepatic biliary tract tumors in the U.S [6]. An increase in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has also been reported in some other countries [7-9]. There have been few studies of the epidemiology of these tumors, and the abrupt increases in mortality related to cholangiocarcinoma have not previously been recognized, partly due to the tendency to combine these tumors with hepatocellular carcinoma as primary liver tumors in compiled reports from cancer registries. As the analysis of time trends in cancer mortality may provide clues to potential etiological factors, we analyzed global trends in cancer mortality from biliary tract malignancies over the past 1–3 decades using data from the World Health Organization (WHO) cancer database. Our aims were to assess the geographical variations, gender differences and trends over time in site-specific (intrahepatic versus extrahepatic) mortality from biliary tract cancers.

Methods

Primary data sources

The WHO database was used to determine the deaths from and mortality rates from biliary tract cancers [10]. Data was obtained for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gall bladder. Annual crude rates and age-standardized rates (1970 world population) by gender were obtained for all countries for which data was available for at least 5 consecutive years.

Data analysis

To summarize the results, we have calculated the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) over the interval for which data were available by fitting a linear regression equation to the natural logarithm of the annual age-standardized rates (ASR) using the calendar year as the independent regressor variable. The statistical significance of the regression coefficients (slopes) were then tested in the usual manner and the EAPC was then calculated from the slope of the resulting regression equation using the equation EAPC = 100 (eslope - 1) [11]. The gender and site-specific EAPC was derived separately for each country. To assess geographical differences, data from individual countries were grouped into continental regions. For European countries, data were also grouped into broad geographic regions: Western Europe, Northern Europe and Central Europe.

Results

Is mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma increasing worldwide?

To ascertain the rate of change of mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, we assessed trends in mortality in reported data available in the WHO databank. Data were available for twenty-two countries. Of these, two countries each were from North America and Oceania, three from Asia and the Middle East, and fifteen from Europe. Thus, all major geographic regions other than Africa were represented. The EAPC in mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was noted to be increasing in all except three countries (Table 1). Of note, data were only available for 8 or less years for each of the three countries for which a decrease in mortality was reported.

Table 1.

Trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tract cancers, WHO Databank (EAPC = estimated annual percent change in age-adjusted mortality rates)

| Extrahepatic tumors | Intrahepatic tumors | ||||||

| Region | Country | EAPC | EAPC | ||||

| Years | Male | Female | Years | Male | Female | ||

| Americas | Canada | 1970–1997 | -1.9 | -2.8 | 1979–1997 | 7.9 | 8.8 |

| USA | 1970–1996 | -2.5 | -2.8 | 1979–1997 | 7.3 | 8.5 | |

| Oceania | Australia | 1970–1995 | -1.9 | -1.9 | 1979–1995 | 12.3 | 12.0 |

| New Zealand | 1970–1996 | -2.7 | -3.1 | 1979–1996 | 4.4 | 3.4 | |

| Western Europe | Austria | 1970–1998 | -1.5 | -2.7 | 1980–1998 | 6.0 | 5.2 |

| Belgium | 1970–1994 | -1.5 | -2.5 | ||||

| Former FDR | 1970–1990 | -0.9 | -1.8 | ||||

| France | 1970–1996 | 1.2 | -0.1 | 1983–1996 | 10.0 | 5.2 | |

| Germany | 1990–1997 | -1.2 | -3.2 | 1991–1997 | 13.2 | 2.5 | |

| Greece | 1970–1997 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1979–1997 | 1.8 | 2.4 | |

| Ireland | 1970–1996 | -0.5 | -2.5 | 1979–1996 | 10.9 | 8.5 | |

| Italy | 1970–1995 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1986–1995 | 4.2 | 5.9 | |

| Netherlands | 1970–1995 | -2.3 | -3.9 | 1979–1995 | 3.5 | 0.2 | |

| Portugal | 1984–1998 | 1.7 | -0.1 | 1984–1996 | 10.4 | 10.3 | |

| Spain | 1970–1994 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1982–1995 | 18.3 | 12.7 | |

| UK | 1970–1996 | -3.7 | -3.1 | 1979–1997 | 8.8 | 9.6 | |

| Central Europe | Czech | 1986–1993 | 0.3 | -2.2 | 1986–1993 | -8.5 | -5.6 |

| Former Czech | 1970–1991 | 1.4 | 0.6 | ||||

| Former GDR | 1976–1990 | -0.5 | -1.9 | ||||

| Hungary | 1970–1995 | 1.1 | -0.6 | 1979–1995 | 1.5 | 2.1 | |

| Slovenia | 1985–1996 | -1.3 | -2.5 | 1988–1996 | 22.1 | 10.3 | |

| Northern Europe | Iceland | 1971–1995 | -2.1 | -2.3 | |||

| Norway | 1970–1995 | 0.1 | -0.9 | 1989–1995 | -3.0 | -2.5 | |

| Sweden | 1970–1995 | 0.6 | -0.5 | 1987–1996 | 9.1 | 3.5 | |

| Asia / Middle East | Israel | 1970–1991 | -3.9 | -4.4 | 1987–1996 | -3.1 | 2.9 |

| Japan | 1970–1994 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 1979–1994 | 7.4 | 0.9 | |

| Singapore | 1970–1996 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1979–1998 | 6.1 | 6.0 | |

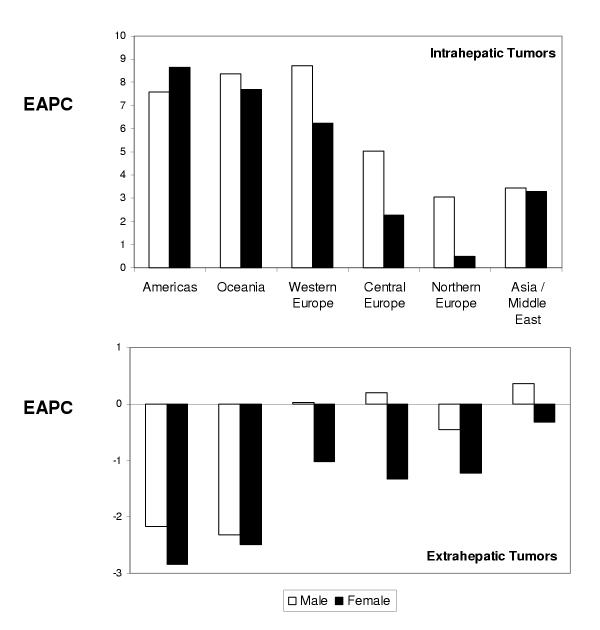

An overall increase in mortality was observed in all regions, with the greatest increases in the Americas, Oceania and Western Europe (Figure 1). The increase in EAPC in these regions was similar to that which we have recently reported in the United States [6]. However, regional differences were noticed in Europe, with lower reported increases in EAPC in Central and Northern Europe. The EAPC was lower for Asia/Middle East, although data from regions of known high incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma such as Thailand and other southeastern nations were not included in this analysis. Thus, there has been a global increase in mortality related to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in regions of low disease prevalence.

Figure 1.

Regional differences in the mean estimated annual percent change in age-adjusted (1970 World Standard population) gender-specific mortality rates from intrahepatic biliary tract tumors (top) and gall-bladder and extra-hepatic biliary tract tumors (bottom).

Are there gender differences in the mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma?

In order to ascertain whether there were gender differences in mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, we analyzed the available gender-specific mortality rates for both females and males in all countries and regions for which data was available. For thirteen of the nineteen countries, in which there was an overall increase in reported mortality rates, the increase in mortality rates for males was greater than for females. In those countries in which rates were decreased, the decrease for males was the same or more than that for females. Overall, the EAPC (mean ± standard error) for males was 6.9 ± 1.5, and for females was 5.1 ± 1.0. The trend towards a greater increase in mortality from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma for males was also noted in the United States [6].

Are there anatomic site-specific differences in mortality from biliary tract malignancies?

Intrahepatic tumors are clinically distinct from extrahepatic tumors. Indeed, the epidemiology and clinical behavior may vary with the anatomic location because of differences in the biological characteristics of the underlying biliary epithelia. We thus assessed trends in mortality from malignancies of the extrahepatic biliary tract and gallbladder. In contrast to the observations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, the EAPC in mortality for extrahepatic biliary tract cancers decreased in most countries for both males and females. The overall EAPC was -0.3 ± 0.4 for males, but -1.3 ± 0.4 for females. An increase in EAPC for males was observed in 11 countries, but only in 6 countries for females. Overall, the reduction in mortality from extrahepatic biliary tract malignancies was greater in females than for males for all countries with decreased mortality rates, with the exception of the United Kingdom. Thus, there has been a worldwide trend towards decreased mortality from extrahepatic tumors, particularly for females.

Discussion

Our analysis indicates a global increase worldwide in mortality related to intrahepatic biliary tract malignancies over the past few decades. An increase is apparent in both industrialized nations as well as developing nations. The increase in mortality rates involves both males and females, although the trends indicate that the increase in mortality is greater in males than in females.

The precise reasons for this increase remain unknown. Apparent increases may arise from a variety of potential causes, such as diagnostic misclassification, improved coding, and enhanced diagnosis due to improved imaging studies or more comprehensive evaluations. Any or all of these may cause apparent increases in cancer mortality rates. Indeed, diagnostic transfer from tumors that may have been previously classified as extrahepatic and are now classified as intrahepatic remains a possibility for some hilar tumors. However, the global trends argue against any of these as they may be expected to demonstrate regional variations. Furthermore, differences in coding or classification would be expected to affect all genders, and thus would be unlikely to result in the observed gender differences. Similarly, the increasing trends in regions of low economic development suggest that better or improved medical imaging and diagnostic technologies are unlikely to have resulted in these global trends. Indeed, the diagnostic approach and classification has not changed over the past several years. Although newer imaging and diagnostic modalities such as magnetic resonance cholangiography or positron-emission tomography scanning may enhance diagnosis of these tumors, their availability is limited to only selected centers in a few countries.

Chronic biliary tract inflammation represents a major risk factor for the development of cholangiocarcinoma. The association between chronic parasitic infection of the biliary tract and cholangiocarcinoma is obvious in regions of high endemicity, such as in certain Far Eastern nations. In Western nations, primary sclerosing cholangitis is a more common risk factor identified with the development of cholangiocarcinoma [12]. However, clinical observations have not indicated an increase in the incidence of either primary sclerosing cholangitis or biliary tract infections. Thus, if the increase in mortality from cholangiocarcinoma is real, other potential etiological factors need to be considered. Potential factors may include infections, toxins or environmental agents causing biliary tract inflammation, or malignant transformation. Recent reports indicate a possible association between chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [13]. However, this remains to be proven. Studies correlating the geographical variations in incidence of chronic HCV infection and mortality from cholangiocarcinoma should be considered. Although the hepatitis C virus infects biliary tract epithelium, it remains unknown whether chronic viral infection predisposes to malignancy.

The intrahepatic biliary epithelia varies from the extrahepatic biliary tract epithelia in its structure, function and embryological derivation. Thus, the risk factors and pathogenesis of tumors from different sites in the biliary tract are likely to be distinct. Differences in the underlying pathogenesis, as well as in their clinical presentation, may thereby account for the divergent trends observed for intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tract tumors. Although separate data on gall-bladder tumors compared to other extrahepatic tumors was not available, these would also be expected to exhibit different epidemiological and clinical characteristics [14]. For example, an increase in the numbers of cholecystectomies performed for non-malignant gall-bladder disease may account for a decreased mortality from gall-bladder tumors, but not other extrahepatic tumors.

In conclusion, there has been a marked global increase in mortality from intrahepatic, but not extra-hepatic, biliary tract malignancies. Furthermore, similar gender and site-specific changes in time-trends of mortality from biliary tract malignancies are present in most regions. The poor response of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma to conventional therapies, along with the concerning global increase in mortality highlights the need for increased efforts to understand their etiology and pathogenesis, as well as further epidemiological investigation to identify the reasons for these concerning trends.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The expertise provided by the staff of the Unit of Descriptive Epidemiology at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (Lyon, France) in maintaining and providing the WHO cancer mortality databank is greatly appreciated. Support for this study was provided by the Scott Sherwood and Brindley Foundation, and Grant DK02678 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1368–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Uttaravichien T, Bhudhisawasdi V, Chartbanchachai W, Elkins DB, Marieng EO, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma in north east Thailand. A hospital-based study. Trop Geogr Med. 1991;43:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haswell-Elkins MR, Mairiang E, Mairiang P, Chaiyakum J, Chamadol N, Loapaiboon V, et al. Cross-sectional study of Opisthorchis viverrini infection and cholangiocarcinoma in communities within a high-risk area in northeast Thailand. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:505–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell DJ. Liver-fluke infection as an aetiological factor in bile-duct carcinoma of man. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:814–24. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Ohshima H, Srivatanakul P, Vatanasapt V. Cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Arora S, Keegan TJ, Hargreaves S, Beck A, et al. Increase in mortality rates from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in England and Wales 1968–1998. Gut. 2001;48:816–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing AW, Gao YT, Devesa SS, Jin F, Fraumeni JF., Jr Rising incidence of biliary tract cancers in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:368–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980130)75:3<368::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski J, Hansson G, Wallerstedt S. Incidence, etiologic aspects and clinicopathologic features in intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma – a study of 51 cases from a low-endemicity area. Acta Oncol. 1998;37:77–83. doi: 10.1080/028418698423212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Databank Unit of Descriptive Epidemiology, International Agency for Research on Cancer. http://www.dep.iarc.fr

- Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1997. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute. 2000.

- Lazaridis KA, Wiesner RH, Porayko MK, Ludwig J, LaRusso NF. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell M, Maddrey WA, editor. Schiff's Diseases of the Liver. 8. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 649–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, et al. Incidence of primary cholangiocellular carcinoma of the liver in japanese patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Cancer. 2000;88:2471–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2471::AID-CNCR7>3.3.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom BL, Hibberd PL, Soper KA, Stolley PD, Nelson WL. International variations in epidemiology of cancers of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5165–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]