Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The goal of this study was to describe reported influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus (pH1N1)-associated deaths in children with underlying neurologic disorders.

METHODS:

The study compared demographic characteristics, clinical course, and location of death of pH1N1-associated deaths among children with and without underlying neurologic disorders reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

RESULTS:

Of 336 pH1N1-associated pediatric deaths with information on underlying conditions, 227 (68%) children had at least 1 underlying condition that conferred an increased risk of complications of influenza. Neurologic disorders were most frequently reported (146 of 227 [64%]), and, of those disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy and intellectual disability were most common. Children with neurologic disorders were older (P = .02), had a significantly longer duration of illness from onset to death (P < .01), and were more likely to die in the hospital versus at home or in the emergency department (P < .01) compared with children without underlying medical conditions. Many children with neurologic disorders had additional risk factors for influenza-related complications, especially pulmonary disorders (48%). Children without underlying conditions were significantly more likely to have a positive result from a sterile-site bacterial culture than were those with an underlying neurologic disorder (P < .01).

CONCLUSIONS:

Neurologic disorders were reported in nearly two-thirds of pH1N1-associated pediatric deaths with an underlying medical condition. Because of the potential for severe outcomes, children with underlying neurologic disorders should receive influenza vaccine and be treated early and aggressively if they develop influenza-like illness.

Keywords: influenza, influenza vaccination, neurologic disorders

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received reports of 343 influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus (pH1N1)-associated deaths in children during the 2009–2010 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic through the Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System. This number of deaths was >5 times the median number of deaths reported during the previous 5 influenza seasons. In each influenza season since data collection began in 2004, neurologic disorders were most frequently reported among children who died and had underlying medical conditions.1,2 In 2005, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) expanded its vaccination recommendations to include these children due to the increased risk of influenza-associated death noted during the 2003–2004 influenza season.3,4 Neurologic disorders in children comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders, including neuromuscular disorders, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and hydrocephalus. Some of these children have associated medical conditions such as heart, lung, or other organ system disorders and many have impaired motor and intellectual function.5 Few published data exist on the clinical characteristics of children with neurologic disorders who die of influenza-associated illness and the contributing causes of death. Some studies speculate that impaired pulmonary function, including decreased ability to protect the airway through cough and proper laryngeal muscle function, contribute to greater risk for pulmonary infection6–8; however, not all children with neurologic disorders have associated pulmonary conditions.

This study assesses pediatric influenza-associated deaths of children with neurologic disorders that occurred during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. In this report, we describe influenza-associated deaths in children with neurologic disorders, their co-occurring conditions, and the clinical course of influenza illness.

METHODS

Data Source and Influenza Case Definition

Influenza-associated pediatric death was added to the national notifiable disease list in 2004. A pediatric influenza-associated death is defined as a death in a child aged <18 years resulting from a clinically compatible illness that was confirmed to be influenza on the basis of an appropriate laboratory test result with no period of complete recovery between the illness and death. Respiratory specimens were tested for influenza at private commercial and hospital laboratories in addition to local, state, or CDC public health laboratories. Appropriate laboratory test methods include a rapid influenza diagnostic test (RIDT), viral isolation in tissue cell culture, enzyme immunoassay, fluorescent antibody testing, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), or immunohistochemical staining of tissue samples. In some instances, laboratory testing identified influenza A virus infections, but subtyping of the virus was not done. During the 2009–2010 influenza season, national virologic surveillance data indicated that pH1N1 accounted for >99% of all circulating influenza strains.9,10 As a result, those cases with laboratory-confirmed influenza A virus infection of undetermined subtype were classified as “probable” pH1N1.

For surveillance purposes, an influenza season is typically defined as October 1 through September 30 of the following year. To clearly delineate seasonal influenza activity from the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, the 2008–2009 season was defined as October 1, 2008, through April 14, 2009, and the 2009–2010 season was defined as April 15, 2009, through September 30, 2010. State and local health departments notified CDC of cases by using a standardized case report form and transmitted the information via an Internet-based interface hosted on the CDC’s Secure Data Network. Data collected on the form included patient demographic characteristics, date and location of death, influenza laboratory test results, results of bacterial culture from sterile sites, complications during the acute illness, underlying medical conditions, and influenza vaccination history. No additional information, including the original medical records or autopsy reports, was available to the reviewers. Children with medical conditions that place them at increased risk for influenza-related complications recognized by the ACIP are referred to hereafter as children with high-risk conditions.11 These included children receiving long-term aspirin therapy who might be at risk for experiencing Reye syndrome after influenza virus infection or those with chronic pulmonary (including asthma), cardiovascular (except hypertension), renal, hepatic, hematologic, or metabolic (including diabetes mellitus) disorders. In addition, children with immunosuppression or any condition (eg, cognitive dysfunction, spinal cord injuries, seizure disorders, other neuromuscular disorders) that can compromise respiratory function or the handling of respiratory secretions or that can increase the risk for aspiration were included as high risk.

Neurologic Disorders Classification

Neurologic disorders were classified into 3 groups: neurodevelopmental disorders, epilepsy, and neuromuscular disorders. Neurodevelopmental disorders included cerebral palsy, moderate to severe developmental delay, and hydrocephalus with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neuromuscular disorders included muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and mitochondrial disorders. Neurologic disorders and comorbid conditions were classified by a behavior-developmental pediatrician (Dr Peacock) and a clinical geneticist (Dr Moore). The standard case report forms were reviewed and given preliminary classifications by each reviewer; any discrepancies were discussed between the 2 reviewers to reach a final classification. In addition, conditions such as seizures were reviewed and excluded if they were considered more likely to be an influenza complication than a previous underlying condition.

Bacterial Coinfections

The results of bacterial cultures of specimens taken from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and pleural fluid that were collected between illness onset and the day of death were summarized. Bacterial cultures from postmortem lung tissue were included for analysis only if the specimen was collected on the day of death. Bacterial culture results without speciation were not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Data were entered into Microsoft Access 2007 (Redmond, WA) and analyzed by using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). The χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare proportions, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to evaluate the difference between medians. All comparisons were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 343 pediatric deaths associated with laboratory-confirmed pH1N1 infection were reported to the CDC from April 15, 2009, to September 30, 2010, by 45 reporting jurisdictions (44 state and 1 US territorial health departments). Two hundred eighty-six (83%) of these deaths were associated with pH1N1 infection, and an additional 57 (17%) pediatric deaths, classified as probable pH1N1 infections, were reported during the same time period. The majority of respiratory specimens collected from pediatric pH1N1 deaths tested positive for influenza by using RT-PCR (88%), followed by RIDTs (8%). Respiratory specimens collected from 33 (10%) of the 343 pediatric pH1N1 deaths initially tested negative using RIDTs but were later confirmed as influenza by using RT-PCR. Information on underlying conditions was available for 336 (98%) of 343 reported deaths; 109 (32%) of 336 children had no high-risk condition, 227 (68%) of 336 children had ≥1 high-risk condition, and 146 (64%) of these 227 had an underlying neurologic disorder. One-hundred fifty-eight (70%) of the 227 children had >1 high-risk condition.

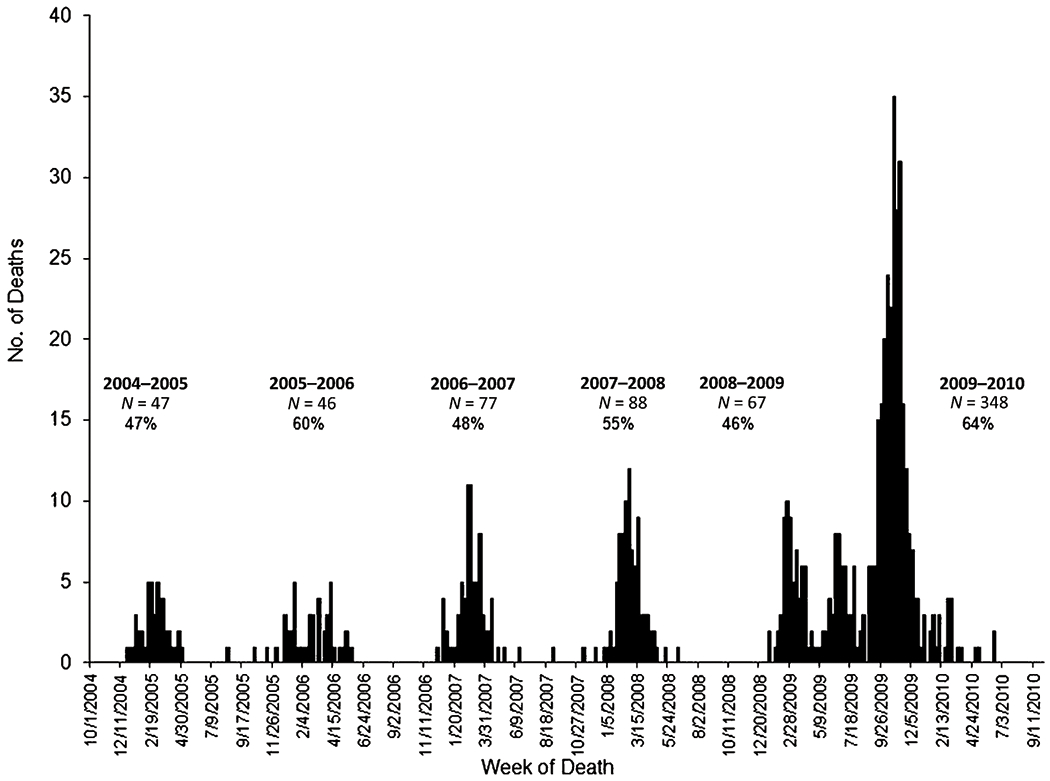

Of the 146 children with neurologic disorders, 28 distinct disorders were reported. Among the 3 major categories, neurodevelopmental disorders were most common (94%) followed by epilepsy (51%) and neuromuscular disorders (6%) (Table 1). Seventy-one (49%) had neurologic diagnoses in >1 category. Among the 137 children with any neurodevelopmental disorder, 41 (30%) had both an intellectual disability and cerebral palsy. Before the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, a median of 67 influenza-associated pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC annually (Fig 1). The percentage of children with underlying neurologic disorders reported during the pandemic was similar to previous influenza seasons.

Table 1.

Neurologic Disorders Among pH1N1-Associated Deaths in Children, United States, 2009–2010a

| Neurologic Disorderb | No. (%) (N = 146) |

|---|---|

| Neuromuscular disorders | 9 (6) |

| Muscular dystrophy | 6 (4) |

| Mitochondrial disorders | 3 (2) |

| Epilepsy | 74 (51) |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders | 137 (94) |

| Intellectual disability | 111 (76) |

| Cerebral palsy | 51 (35) |

| Hydrocephalus with ventriculoperitoneal shunt | 16 (11) |

| Autism | 3 (2) |

Denominator is the total number of children with neurologic disorders (N = 146). Sum of percentages is >100 because 71 children had neurologic diagnosis in >1 category (neuromuscular disorders, epilepsy, and neurodevelopmental disorders).

Diagnoses that were reported in ≤1% in children with neurologic disorders are not included.

FIGURE 1.

Number of influenza-associated pediatric deaths reported to the CDC and percentage of children with neurologic disorders among those with underlying conditions according to influence season, United States, 2004–2010. An influenza season is typically defined as October 1 through September 30 of the following year. To clearly delineate seasonal influenza activity from the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, the 2008–2009 season was defined as October 1, 2008, through April 14, 2009, and the 2009–2010 season as April 15, 2009, through September 30, 2010.

Of 146 pediatric pH1N1 deaths with a neurologic disorder, about one-half were males, and the median age was 10 years (range: 0–17 years) (Table 2). The median time from onset of symptoms to death was 8 days (range: 0–141 days). Among the 144 children with a reported location of death, 115 (80%) died in the hospital after admission; among these, 94 (82%) had a known date of hospital admission, and their median time from hospital admission to death was 7 days (range: 0–122 days). When compared with pH1N1-associated pediatric deaths among children without high-risk conditions, children with a neurologic disorder were older (P = .02), had a significantly longer duration of illness between onset to death (P < .01), and were more likely to die in the hospital after admission (P < .01) (Table 2). Only 21 (23%) children received the seasonal influenza vaccine, and 2 (3%) children were fully vaccinated for pH1N1. Children with neurologic disorders who died in the hospital after admission had a significantly longer duration of illness between hospital admission and death (P < .01) and were significantly more likely to have complications occur during their illness (P < .01). The most common complications among children with neurologic disorders were radiographically confirmed pneumonia (70%) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; 40%) (Table 3). Children with neurologic disorders were more likely to develop radiographically confirmed pneumonia (P < .01), ARDS (P = .03), and seizures (P = .04) but were less likely to develop shock (P < .01) and sepsis (P < .01) than children without high-risk conditions. Children without high-risk conditions were significantly more likely to have a positive result on bacterial culture from a sterile site (P < .01). The most common pathogens identified were Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. When compared with children with neurologic disorders, children without high-risk conditions were more likely to have a Streptococcus pyogenes (P = .03) or methicillin-resistant S aureus (P < .01) coinfection. No other statistically significant difference between percentages of bacterial coinfections among the 2 groups was identified.

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Children Who Died With Influenza and Had Neurologic Disorders Compared With Children Without a High-Risk Condition, United States, 2009–2010

| Characteristic | Any Neurologic Disorder (N = 146) | No High-Risk Conditions (n = 109) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 75 (51) | 49 (45) | .3 |

| Race | .1 | ||

| White | 102/131 (78) | 66/94 (70) | |

| Black | 22/131 (17) | 16/94 (17) | |

| Asian | 5/131 (4) | 4/94 (4) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1/131(<1) | 1/94 (1) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1/131(<1) | 7/94 (7) | |

| Ethnicity | .7 | ||

| Hispanic | 45/136 (33) | 26/86 (30) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 91/136 (67) | 60/86 (70) | |

| Age groups | .3 | ||

| 0–5 mo | 7/146 (5) | 13/109 (12) | |

| 6–23 mo | 15/146 (10) | 13/109 (12) | |

| 24–59 mo | 16/146 (11) | 10/109 (9) | |

| 5–8 y | 26/146 (18) | 23/109 (21) | |

| 9–12 y | 35/146 (24) | 24/109 (22) | |

| 13–17 y | 47/146 (32) | 26/109 (24) | |

| Age, y | 10 (0–17) | 8 (0–17) | .02 |

| Time from onset to death,b d | 8 (0–141) | 4 (0–125) | <.01 |

| Time from hospital admission to death,c median (range), d | 7 (0–122) | 1 (0–125) | <.01 |

| Location of death | |||

| Emergency department or at home or in transit to hospital | 29/144 (20) | 46/108 (43) | <.01 |

| Hospital, admitted | 115/144 (80) | 62/108 (57) | |

| Influenza vaccination statusd | |||

| Recommended for vaccination by using 2008 and 2009 ACIP criteria | 139/146 (95) | 96/109 (88) | .04 |

| Seasonal influenza vaccine | 21/92 (23) | 7/58 (12) | .1 |

| Monovalent 2009 influenza A (H1N1) vaccine | 2/73 (3) | 0/51 (0) | .5 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range).

Based on Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Illness onset date was known for 141 children with neurologic disorders and 106 children without high-risk conditions.

Of those children who died in the hospital, the hospital admission date was known for 94 children with neurologic disorders and for 53 children without high-risk conditions.

Children aged ≥6 months were considered fully vaccinated when documentation on the case report form indicated that they had received the influenza vaccine in the appropriate number of doses at least 14 days before illness onset.

TABLE 3.

Acute Complications of Children With Neurologic Disorders and Children Without a High-Risk Condition and Influenza-Associated Death, United States, 2009–2010

| Complication | Any Neurologic Disorder (N = 146) | No High-Risk Conditions (n = 109) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical course of illness | |||

| Radiologically confirmed pneumonia | 98/140 (70) | 45/104 (43) | <.01 |

| ARDS | 56/140 (40) | 28/104 (27) | .03 |

| Seizures | 17/140 (12) | 4/104 (4) | .04 |

| Bronchiolitis | 4/140 (3) | 3/104 (3) | .9 |

| Encephalopathy | 10/140 (7) | 8/104 (8) | .9 |

| Shock | 14/140 (10) | 33/104 (32) | <.01 |

| Sepsis | 22/140 (16) | 32/104 (31) | <.01 |

| Viral coinfection | 2/140 (1) | 1/104 (1) | .9 |

| Specimen collected for bacterial culture from a sterile siteb | 75/136 (55) | 53/96 (55) | .7 |

| Growth in culture from specimens obtained from a sterile site | 11/75 (15) | 29/53 (55) | <.01 |

| Organisms isolated from sterile sites S aureus | |||

| Methicillin-susceptible S aureus | 1/75 (1) | 3/53 (6) | .3 |

| Methicillin-resistant S aureus | 1/75 (1) | 10/53 (19) | <.01 |

| Susceptibility unknown | 0 | 1/53 (2) | .4 |

| Streptococcus species | |||

| S pneumoniae | 2/75 (3) | 6/53 (11) | .07 |

| S pyogenes | 0 | 4/53 (8) | .03 |

| Otherb | 0 | 2/53 (4) | .2 |

| Gram-negative organisms | 5c/75 (7) | 2d/53 (4) | .7 |

| Other gram-positive organisms | |||

| Peptostreptococcus | 1/75 (1) | 0 | .9 |

| Cases with ≥1 bacterial coinfection | 1/75 (1) | 1/53 (2) | .9 |

Data are presented as n (%).

χ2 or Fisher’s exacttest for categorical variables.

Includes Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus constellatus.

Includes Acinetobacter, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae (not type B), Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Includes Enterobacter cloacae and Neisseria meningitidis.

Additional comorbid high-risk conditions were reported among 110 (75%) of 146 children with a neurologic disorder and pH1N1 infection. The most common comorbid conditions reported were a pulmonary disorder (48%), metabolic disorder6%), cardiac disease or congenital heart defect (16%), and chromosomal abnormality (12%) (Table 4). Nine (13%) of the 70 children had >1 pulmonary disorder.

TABLE 4.

Additional High-Risk Conditionsa Among Children With Neurologic Disorders and Influenza-Associated Death, United States, 2009–2010

| Condition | Total (N = 146) |

|---|---|

| Neurologic disorder onlyb | 36 (25) |

| Additional comorbid conditions | 110 (75) |

| Hemoglobinopathy | 1 (<1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (3) |

| History of febrile seizures | 3 (2) |

| Skin or soft tissue infection | 1 (<1) |

| Cardiac disease or congenital heart defect | 23 (16) |

| Renal disease | 5 (3) |

| Chromosomal abnormality | 18 (12) |

| Mitochondrial disorder | 8 (5) |

| Immunosuppressive condition | 13 (9) |

| Metabolic disorder | 24 (16) |

| Other | 3 (2) |

| Any pulmonary disorder | 70 (48) |

| Asthma or reactive airway disease | 36 (25) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (<1) |

| Pulmonary diseasec | 42 (29) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Medical conditions included inthistable are not mutually exclusive.

Includes neurodevelopmental disorders, seizure disorders, and neuromuscular disorders.

The most commonly reported pulmonary diseases were bronchopulmonary dysplasia and restrictive lung disease.

DISCUSSION

This report describes 146 laboratory-confirmed pH1N1-associated deaths in children with neurologic disorders that occurred during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic and were reported to the CDC and compares these cases with 109 pH1N1-associated deaths in children without high-risk conditions. Severe outcomes among children occurred throughout the pandemic. A median number of 67 seasonal influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported during the previous 5 influenza seasons, but the number of pediatric deaths associated with pH1N1 infection was >5 times that number. Among children with high-risk conditions, neurologic disorders were most frequently reported, and the distribution of neurologic disorders during the pandemic was similar to previous influenza seasons.2,4 Neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy were by far more common than neuromuscular disorders; multiple neurologic disorders were reported in nearly one-half of these children. Children with neurologic disorders were older, had a longer duration of illness, were more likely to develop pneumonia and ARDS, and were more likely to die after being admitted to the hospital than children without high-risk conditions. Pulmonary disorders were common among children with neurologic disorders.

Children with neurologic disorders might be at increased risk of complications from influenza due to compromised pulmonary function and inability to handle an excess of secretions.4,12,13 Several of the children in this case series also had scoliosis with restrictive lung disease, further increasing their risk of developing influenza-associated pneumonia. The finding that the majority of children with neurologic disorders developed pneumonia or ARDS as an acute complication of influenza is not unexpected, given that these children might have difficulty with muscle function that compromises clearing of pulmonary secretions.12

Ten percent of the respiratory specimens collected from pediatric pH1N1 deaths were initially negative for influenza by using an RIDT but later were confirmed as influenza by using RT-PCR. False-positive results with RIDTs can occur, which could lead to delays in treatment. Although RIDTs can provide results within ≤30 minutes and can be performed in emergency department or physician settings, they have low to moderate sensitivity compared with RT-PCR.14–18 Physicians should use caution when interpreting the negative results of RIDTs when a child presents with clinical influenza-like symptoms, and more accurate tests (eg, RT-PCR) should be considered if a laboratory-confirmed influenza diagnosis is desired. Antiviral treatment should not be withheld from patients with suspected influenza even if they test negative for influenza by using an RIDT.14–19

Children with neurologic disorders had a significantly longer duration of illness from hospital admission to death compared with children without a high-risk condition. It is possible that physicians of children with neurologic disorders were more likely to hospitalize their patients early in their illness, given their underlying medical conditions and a perceived greater risk of influenza-associated complications. Children without high-risk conditions were more likely to have developed sepsis and bacterial coinfection, including methicillin-resistant S aureus. The development of symptoms associated with a bacterial coinfection may have been the immediate cause for seeking medical care in these children. There are several potential mechanisms by which influenza virus infections might increase the risk for subsequent bacterial coinfections. If influenza virus infection destroys the respiratory epithelium so that the basement membrane is exposed, adherence of bacteria is enhanced.20,21 In addition, influenza virus infection may impair the function of immunologic cells, suppressing the respiratory burst response of neutrophils to stimulation.21–24

Annual influenza vaccination remains the best method for preventing influenza and its complications, and in 2010, the ACIP extended influenza vaccination recommendations to include all persons aged ≥6 months.11 Estimated seasonal influenza vaccine coverage rates in children aged 6 months to 17 years were 24% prepandemic.25 During the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, estimated national influenza vaccination coverage among children aged 6 months to 17 years was 44% for seasonal influenza and 40% for monovalent 2009 influenza A (H1N1) vaccination.26 The majority of children in this study (70%) died before November 2009, when the pH1N1 monovalent vaccine became widely available. However, vaccination with recent seasonal influenza vaccines provided little to no benefit to children and adults with respect to an increase in cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies against pH1N1.27 Continued efforts are needed to improve vaccine coverage in all children, especially those at increased risk of influenza-related complications. Physicians should counsel parents regarding the safety and effectiveness of influenza vaccine in children.19 Efforts should be made to coordinate among parents, primary care clinicians, developmental pediatricians, and neurologists to ensure vaccination each year.

These findings are subject to several limitations. First, completeness of case report forms varied, and there was limited information on children who died outside the hospital. Influenza testing is not universal in children who present to health care providers with influenza-like illness, and influenza-associated pediatric deaths may thus be underreported. Although influenza-associated pediatric mortality became nationally notifiable in 2004, only 47 states have implemented state-level reporting requirements as of 2010.28 Regardless, it is important for clinicians to inform their health department about potential influenza-associated pediatric deaths, and state health departments should notify the CDC of all laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths as soon as possible. In addition, treating clinicians might attribute the child’s death to causes other than influenza, such as complications of their underlying medical condition or secondary complications of influenza. Before the 2010–2011 season, limited data were collected regarding antibiotic and antiviral use after illness onset, and data regarding timing and duration of antibiotic and antiviral therapy were not collected. Children who were hospitalized were more likely to receive antibiotic and antiviral therapy compared with those children who died outside the hospital. Influenza-associated deaths among children are rare, and during the 2008–2009 influenza season, 25 jurisdictions reported influenza-associated pediatric deaths to the CDC, but this number increased to 45 during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. These 20 additional jurisdictions contributed 94 influenza-associated pediatric deaths. Underreporting might have been offset by heightened awareness of influenza due to the pandemic, and physicians might have been more likely to report and conduct laboratory testing for influenza in patients presenting with symptoms compatible with influenza during the 2009–2010 season than during previous seasons. This possibility, in addition to the larger number of jurisdictions reporting, might partially explain the large increase in pediatric deaths during 2009–2010.

CONCLUSIONS

Forty-three percent of all children with influenza-associated mortality during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic had a neurologic disorder. Neurologic disorders belong to a group of chronic medical conditions that confer a higher risk of influenza complications. Clinicians should be aware of the potential for severe outcomes of influenza in children with neurologic disorders and both ensure that they are vaccinated and treat these children early and aggressively with influenza antiviral agents ifthey present with influenza-like illness.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

The 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic caused illness in all age groups, but children were disproportionately affected. Children with underlying neurologic disorders were at high risk of influenza-related complications, including death.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

This study provides the first detailed description of underlying neurologic disorders among children who died of influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus infection.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- pH1N1

influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus

- RIDT

rapid influenza diagnostic test

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for pediatric deaths associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection—United States, April-August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(34):941–947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox CM, Blanton L, Dhara R, Brammer L, Finelli L. 2009 Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) deaths among children—United States, 2009-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl 1):S69–S74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-8):1–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR, et al. ; Influenza Special Investigations Team. Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003-2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2559–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodge NN. Cerebral palsy: medical aspects. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(5):1189–1207, ix [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir K, McMahon S, Barry L, Ware R, Masters IB, Chang AB. Oropharyngeal aspiration and pneumonia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42(11):1024–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young NL, McCormick AM, Gilbert T, et al. Reasons for hospital admissions among youth and young adults with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brammer L, Blanton L, Epperson S, et al. Surveillance for influenza during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic—United States, April 2009-March 2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl 1):S27–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: influenza activity—United States, 2009-10 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(29):901–908 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keren R, Zaoutis TE, Bridges CB, et al. Neurological and neuromuscular disease as a risk factor for respiratory failure in children hospitalized with influenza infection. JAMA. 2005;294(17):2188–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inal-Ince D, Savci S, Arikan H, et al. Effects of scoliosis on respiratory muscle strength in patients with neuromuscular disorders. Spine J. 2009;9(12):981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Evaluation of rapid influenza diagnostic tests for detection of novel influenza A (H1N1) virus—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58(30):826–829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginocchio CC, Zhang F, Manji R, et al. Evaluation of multiple test methods for the detection of the novel 2009 influenza A (H1N1) during the New York City outbreak. J Clin Virol. 2009;45(3):191–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurt AC, Baas C, Deng YM, Roberts S, Kelso A, Barr IG. Performance of influenza rapid point-of-care tests in the detection of swine lineage A(H1N1) influenza viruses. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2009;3(4):171–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uyeki TM. Influenza diagnosis and treatment in children: a review of studies on clinically useful tests and antiviral treatment for influenza. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(2):164–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uyeki TM, Prasad R, Vukotich C, et al. Low sensitivity of rapid diagnostic test for influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):e89–e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(1):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hers JF, Masurel N, Mulder J. Bacteriology and histopathology of the respiratory tract and lungs in fatal Asian influenza. Lancet. 1958;2(7057):1141–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peltola VT, McCullers JA. Respiratory viruses predisposing to bacterial infections: role of neuraminidase. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(suppl 1):S87–S97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartshorn KL, Liou LS, White MR, Kazhdan MM, Tauber JL, Tauber AI. Neutrophil deactivation by influenza A virus. Role of hemagglutinin binding to specific sialic acid-bearing cellular proteins. J Immunol. 1995;154(8):3952–3960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finelli L, Fiore A, Dhara R, et al. Influenza-associated pediatric mortality in the United States: increase of Staphylococcus aureus coinfection. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickerson CL, Jakab GJ. Pulmonary antibacterial defenses during mild and severe influenza virus infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58(9):2809–2814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage among children and adults—United States, 2008-09 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(39):1091–1095 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Final estimates for 2009-10 seasonal influenza and influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccination coverage—United States, August 2009 through May 2010. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Available at: www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/coverage_0910estimates.htm. Accessed January 5, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, et al. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(20):1945–1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE). The CSTE state reportable conditions assessment (SRCA). Available at: www.cste.org/dnn/ProgramsandActivities/PublicHealthInformatics/StateR-eportableConditionsQueryResults/tabid/261/Default.aspx. Accessed February 8, 2012