Abstract

Prior research suggests social ties with undocumented immigrants among Latinxs may increase political engagement despite constraints undocumented social networks may introduce. We build on prior research and find across six surveys of Latinxs that social ties with undocumented immigrants are reliably associated with collective, identity expressive activities such as protesting, but not activities where immigration may not be immediately relevant, such as voting. Moreover, we assess a series of mechanisms to resolve the puzzle of heightened participation despite constraints. Consistent with prior research at the intersection of anti-immigrant threat and Social Identity Theory, we find Latinxs with strong ethnic identification are more likely to engage in political protest in the presence of social ties with undocumented immigrants, whereas weak identifiers disengage. We rule out alternative mechanisms that could link undocumented social ties with participation including political efficacy, a sense of injustice, linked fate, acculturation, outgroup perceptions of immigration status, partisan identity, conducive opportunity structures, and prosociality. Our contribution suggests the reason social ties with undocumented immigrants are not necessarily a hindrance to political engagement among Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics is because they can draw from identitarian resources to overcome participatory constraints.

Keywords: Latino politics, political participation, immigration, race and ethnic politics, political psychology, social identity theory

Introduction

How do undocumented social ties motivate political engagement among Latinxs? Undocumented immigrants are increasingly relevant in the social life of the Latinx community. The undocumented population has increased from 3.5 to 10 million between 1990 and 2017. In all, 70 percent of the undocumented originate from Latin America. Moreover, the proportion of long-term undocumented immigrants living in the United States over ten years has increased more than 80 percent due to limited options for attaining legal status and higher reentry costs. At the same time, interior immigration enforcement grew significantly since Clinton-era immigration reforms, bringing fear of deportation from the border to the streets of American cities.1

Prior research demonstrates anti-immigrant policies spur political action not only among immigrants, but Latinxs writ large (Barreto et al. 2009; Bowler, Nicholson, and Segura 2006; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura 2001; Zepeda-Millán 2017). This research implicitly assumes Latinxs have ties to the immigrant experience, if not undocumented people. This research also assumes Latinxs are collectively mobilized by political rhetoric and punitive policies targeting undocumented community members. However, little work assesses the consequences of social ties with undocumented immigrants on political behavior directly, and even less identifies mechanisms motivating participation among Latinxs with undocumented social ties.

Drawing on six nationally representative surveys of Latinxs, we demonstrate social ties with undocumented immigrants are consistently associated with collective forms of political participation amenable to facilitating group interests and identity expression, such as protesting. Conversely, undocumented social ties do not motivate individualistic forms of political participation in support of broader agendas, such as voting. We draw on Social Identity Theory to explain why undocumented social ties motivate collective political engagement despite the constraints Latinxs with undocumented social ties may face. We find the mobilizing influence of undocumented social ties is conditional on the strength of Latinx identity. Undocumented social ties compel collective action among high Latinx identifiers who are moved to defend stigmatized subsets of the group but inhibit participation among low identifiers who may wish to dissociate from the group in the face of proximal threats. Moreover, we find relative to low identifiers, high identifiers with undocumented social ties are more likely to support pro-immigrant activism and interpret threats to immigrants as threats to Latinxs writ large.

This paper makes three contributions. First, we explain why Latinxs with undocumented social ties are motivated to engage in political participation despite the marginalization of undocumented immigrants and the spillover effects that follow for their loved ones (Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán 2017). We posit group identity links undocumented social ties to pro-group engagement. Contrary to conventional wisdom, our paper suggests having an undocumented tie does not hinder engagement if it makes group identity salient. Importantly, we demonstrate identity centrality is the superordinate mechanism driving pro-group participation in the presence of undocumented social ties net of other relevant mechanisms such as acculturation, efficacy, linked fate, perceived injustice, a conducive opportunity structure, and the salience of other social identities.

Second, we contribute to the identity-to-politics literature. Prior research demonstrates policy (Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura 2001; Pantoja and Segura 2003), rhetorical (Pérez 2015a, 2015b), and geographic context (Bedolla 2005) can politicize identity. We intervene by explicitly identifying the importance of social context in politicizing identity, with downstream consequences for political engagement.

Third, we add to growing research documenting the political consequences of the expansion of interior immigration enforcement among Latinx communities. An increasingly punitive immigration enforcement context may drive Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics to reduce contact with government and retreat from political life. We theorize and demonstrate that undocumented social ties are a principal manifestation of a threatening immigration context in the everyday lives of Latinxs, and directly assess the capacity for group identity to condition responses to that threat. Thus, we provide a fuller theorization and exploration of what having undocumented social ties means for the Latinx community.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. We review the literature, noting developments in the growth of interior enforcement and the changing nature of the undocumented population. We outline several hypotheses connecting identity, undocumented social ties, and political participation. We then describe our data, before explicating the results. We conclude with a discussion of limitations and identify several areas for future research.

Theory

Undocumented Social Ties in Context

In response to a series of policies and proposals criminalizing undocumented immigrants (e.g., Proposition 187 in California and HR 4437), a large body of research examined the consequences of punitive immigration contexts on political engagement Latinxs. Prior evidence suggests these anti-immigrant policies prompted Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics to naturalize, register, vote, protest, and shift partisan loyalties (Barreto et al. 2009; Bowler, Nicholson, and Segura 2006; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura 2001; Pantoja and Segura 2003; Zepeda-Millán 2017). This research assumes that Latinxs become politically mobilized to protect the undocumented co-ethnics to whom they are connected. However, with some exceptions (Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán 2017), there is limited research directly examining the influence of undocumented social ties on political engagement, much less how social ties motivate political participation.

Confoundingly, prior literature suggests in the current political moment, undocumented social ties may depress political participation. First, the contemporary context is much more repressive. Since the 2006 anti-HR 4437 protests, annual deportations increased fourfold, from 96,000 to 364,000 (Online Appendix Section A, Figure A.1). Mandates increasing collaboration between immigration authorities and local law enforcement targeted Latinxs irrespective of citizenship status (Armenta 2017). The Trump administration precipitated an unprecedented rise in noncriminal immigrant deportations (Capps et al. 2018). As a consequence, more than 90 percent of deportees were Latinx in 2018 despite being only 50 percent of immigrants and 75 percent of undocumented immigrants (Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse 2018).2 It may be this heightened anti-immigrant, anti-Latinx environment diminishes the mobilizing capacity of threat observed in previous periods. Indeed, Zepeda-Millán (2017) indicates increased deportations during the summer of 2006 depressed future political participation, writing, “Anti-movement state-sponsored suppression was carried out through . . . immigration policing by proxy, deportation, and detention, and worksite immigration raids of potential protest participants” (p. 146), which engendered enough fear that “immigrant communities . . . felt pushed ‘back into the shadows” (p. 160).3

Second, anti-immigrant policies reduce Latinx contact with government programs providing socioeconomic resources necessary for political engagement (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman 1995). This dynamic is particularly pronounced among Latinxs with undocumented family members (Alsan and Yang 2018; Flores 2014; Pedraza, Nichols, and LeBrón 2017; Vargas 2015; Yoshikawa 2011). Third, having an undocumented family member may result in anxiety along with declines in mental and emotional health (Dreby 2015; Nichols, LeBrón, and Pedraza 2018; Vargas et al. 2019; Vargas and Pirog 2016). These consequences can independently undermine political engagement (Ojeda 2015). Fourth, a threatening immigration enforcement context via undocumented social ties can undercut trust in government, with deleterious consequences for participation (Rocha, Knoll, and Wrinkle 2015; Sanchez et al. 2015). Finally, undocumented social ties may provide weak levels of political socialization and transmission to documented Latinx peers as undocumented immigrants are less civically incorporated relative to documented immigrants and may retreat from political life due to fear of deportation (Bandura and Walters 1977; Brown and Bean 2016; Gleeson 2010; Jennings, Stoker, and Bowers 2009; Yoshikawa 2011).

However, undocumented social ties may motivate different types of political participation. Some research finds punitive immigration policies increase turnout (Reny, Wilcox-Archuleta, and Nichols 2018; White 2016). These studies, however, do not directly evaluate the effect of having an undocumented social tie. Other research shows undocumented social ties reduce the likelihood of voter registration but increase protest participation (Amuedo-Dorantes and Lopez 2017; Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán 2017).

We contend undocumented social ties motivate protest participation, specifically, but not voting. Why? First, and most importantly, protests offer opportunities for collective identity expression. Latinxs with undocumented social ties may be inclined to engage in participatory activities amenable to expressions of a collective Latinx immigrant identity. Protest participation offers a stronger possibility of engagement with other Latinxs experiencing threat from immigration enforcement via undocumented social ties and allows for engagement on the basis of group-specific interests (Klandermans 2014). Given protest activity offers a stronger opportunity for identity expression, it may also help Latinxs leverage their identity to overcome the constraints undocumented social ties impose (Miller et al. 1981; Shingles 1981). We explore and explicitly test identity as a mechanism linking undocumented social ties to protest in the following section. Related to this, protest behavior often targets specific causes (e.g., immigrant rights). Conversely, voters choose candidates with broad electoral platforms. Often, in the context of immigration enforcement, there is no distinction between candidate choices (Jones-Correa and De Graauw 2013). Therefore, social ties with undocumented immigrants may be more likely to generate protest engagement. Finally, protesting may be less institutionally risky. Scholars suggest undocumented ties deter voting because punitive immigration enforcement undercuts government trust and heightens the perceived risk of proximal status exposure when registering and voting (Amuedo-Dorantes and Lopez 2017; Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán 2017). Thus, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Undocumented social ties will be associated with heightened participation in protest activity, but not voting.

Undocumented Social Ties and the Identity-to-Politics Link

Prior research has little to offer in identifying mechanisms linking undocumented social ties to participation despite the constraints undocumented social ties impose. This paper seeks to resolve the lacuna. We theorize the mobilizing effect of undocumented social ties among Latinxs is conditional on group identity. We posit undocumented social ties subject Latinxs to punitive immigration policies that disparately affect Latinxs as a group. Based on this assumption, Social Identity Theory suggests low-identifying Latinxs may distance themselves from their group membership to maintain individual self-esteem (Huddy 2003; Tajfel et al. 1979). However, high-identifying Latinxs will be motivated to protect the group to maintain the positive distinctiveness of the group (Bedolla 2005; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje 2002; Lee 2005; Mossakowski 2003; Pérez 2015a, 2015b; Phinney et al. 2001). Commensurately, high identifiers may leverage their identity to access social support from other group members in addition to a sense of internal efficacy to overcome the negative consequences of a threatening policy environment (Miller et al. 1981; Noh and Kaspar 2003; Utsey et al. 2000; Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013).

We assume high-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties take anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric personally. This is not simply because they have undocumented loved ones, but also because characterizations, behaviors, and policies propagated by the dominant group define Latinxs as illegitimate members of the national polity. For example, whites motivated by anti-Latinx, anti-immigrant attitudes conflate illegality with Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics writ large (Abrajano and Hajnal 2017; Flores and Schachter 2018). These beliefs extend beyond interpersonal interaction and are embedded in state behavior, including the police and social services, often in a discriminatory manner (Armenta 2017; Sáenz and Manges Douglas 2015).4 Not all Latinxs will perceive anti-immigrant rhetoric as anti-Latinx. Indeed, prior research suggests threatening environments may, instead, lead members to distance themselves from the targeted group (Bedolla 2005; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje 2002). However, a strong group identity may provide a means of coping with discrimination, and individuals may, therefore, lean into that identity when they feel threatened on racial or ethnic grounds (Brondolo et al. 2009; Lee 2005; Phinney et al. 2001). Scholars observe this elsewhere in the literature, where Pérez (2015b) finds anti-immigrant rhetoric motivated pro-group behavior among Latinxs regardless of immigration status. Therefore, we contend,

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

High-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties will be more likely to perceive anti-immigrant sentiment as anti-Latinx sentiment than will low identifiers with undocumented social ties.

Moreover, as mentioned before, undocumented ties may motivate particular types of political participation via a strong group identity. We posit a strong group identity promotes participation in activities clearly promoting the status of the group. High identifiers with undocumented social ties will seek to channel energy to forms of participation, such as protesting, that are expressly collective and speak directly to the relevant threat. Likewise, Latinxs with a strong sense of ethnic identity may think of their individual grievances as group-based, which could motivate collective forms of political engagement (Banks, White, and McKenzie 2019; Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013). Conversely, high-identifying Latinxs may not privilege voting as a means to further the status of the group and their undocumented co-ethnics. Unlike protesting, voting is an individualistic referendum on a broad spectrum of issues that may or may not be relevant to the threat posed by punitive immigration policy (Klandermans 2014; Poletta and Jasper 2001; Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013; Van Zomeren, Postmes, and Spears 2008). To be fair, there may be electoral contexts where punitive immigration policy is highly relevant. In these cases, we might expect heightened voter turnout (e.g., Barreto 2010; Fraga 2016; Valenzuela and Michelson 2016). Generally speaking, however, voting is too broad to assess the identity-to-politics link. Instead, we would expect participation compelled by undocumented ties visà-vis a strong group identity to manifest in collective activities, such as protesting. Thus,

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

High-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties will be more likely to engage in pro-immigrant activities other than voting relative to low-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties.

Finally, we adjudicate the importance of identity over other mechanisms in the extant Latinx politics literature. The idea group identity motivates political engagement in response to threat is not new (Pérez 2015a, 2015b). However, there is no assessment of the relevance of identity among Latinxs with undocumented social ties. The work closest to this study evaluates the influence of knowing a deportee on protesting conditional on a sense of injustice among Latinxs (Walker 2020; Walker, Roman, and Barreto 2020).

We contend perceived injustice is an outgrowth of identity among Latinxs. Research from political psychology finds identity centrality underlies other conceptions of group-based grievances, such as perceived injustice or group efficacy, as a mechanism to participation. Van Zomeren, Postmes, and Spears (2008) compared the relative performance of group efficacy, perceived injustice, and identity centrality in a meta-analysis of 182 studies. While perceived injustice and efficacy are consistently associated with collective action, these concepts are subordinate to identity as a participation determinant. Together with recent research demonstrating the importance of identity in shaping Latinx political participation, we hypothesize identity is the primary mechanism motivating participation in the presence of undocumented social ties. Thus,

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Group identity as the mechanism linking undocumented social ties to pro-immigrant political participation will persist net of alternative mechanisms.

Design

Data

We use six surveys to test our hypotheses. They include (1) the 2010 Pew National Latino Survey (Pew ‘10, N = 1,375), (2) the Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (LNHIS ‘15, N = 1,494), (3) the Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey (CMPS ‘16, N = 3,008), (4) the Latino Decisions Midterm Survey (LDMS ‘18, N = 406), (5) the Latino Decisions Election Eve poll (LDEE ‘18, N = 2,643), and (6) the SOMOS-UNIDOSUS National Survey of Latinos (SOMOS ‘20, N = 1,830). Each survey characterizes different Latinx population subsets. Pew ‘10, LNHIS ‘15, CMPS ‘16, and SOMOS ‘20 represent the national Latinx adult population. LDMS ‘18 represents Latinx registered voters in sixty-one competitive congressional districts during the 2018 midterm. LDEE ‘18 represents the national population of Latinx likely voters. Surveys are weighted to U.S. Census population parameters for the relevant Latinx population subset. Surveys are administered in English or Spanish conditional on respondent preferences.5

We first assess the relationship between undocumented social ties and participation before testing our hypotheses regarding Latinx identity (H1). There are two primary outcomes across nearly all surveys: protest and voting. The Pew, CMPS, LDMS, LDEE, and SOMOS surveys ask respondents about retrospective protest participation and are binary indicators.6 The LNHIS asks respondents about prospective protest participation on a 5-point scale.7 All surveys ask about protest participation generally or in an electoral context except for the Pew ‘10 survey, which asks specifically about pro-immigrant protest participation. Voting measures are not in the Pew (due to omission) or LDEE survey (respondents in that sample either voted or reported they were certain voters). The CMPS includes a binary retrospective voter file-validated voting indicator. The LNHIS, LDMS, and SOMOS surveys include prospective voting measures, measured on 5-point, 5-point, and 10-point scales, respectively.8

The participation outcomes come with some caveats. Some outcomes are specific to immigration whereas others are generalized or specific to electoral contexts. This could be problematic given our theory posits undocumented social ties motivate pro-immigrant behavior. Although protest offers avenues for pro-immigrant behavior, the content of protests is varied. In this case, our protest outcomes may be conceptually flawed in that they are not measuring the types of protest participation consistent with the theory. We offer evidence generalized protest measures mostly capture pro-group, specifically pro-immigrant, politics. Undocumented social ties are positively associated with retrospective pro-immigration protests in the Pew ‘10 study, suggesting at least some of the association between generalized protest measures and undocumented social ties is driven by pro-immigrant behavior (Figure 1). Undocumented social ties are associated with pro-immigrant policy preferences but not immigration-irrelevant liberal policy preferences, suggesting the primacy of social ties and support for immigrants over ideology (Online Appendix, Table K.14). Pro-immigrant attitudes are positively associated with the generalized protest measure in the CMPS ‘16 data, suggesting Latinxs are protesting on the basis of pro-immigrant motivations (Online Appendix, Table T.27, Models 1–2). Moreover, the LDEE ‘18 electoral retrospective protest measure is positively associated with objective measures of pro-immigration protests, suggesting electoral protest measures capture participation in actual immigration protests (Online Appendix Section S). Finally, the results we present and the similarity in effect estimates relative to the distinct outcome types all operate in the same direction, suggesting they capture the same concept despite measurement differences (Figure 1).9

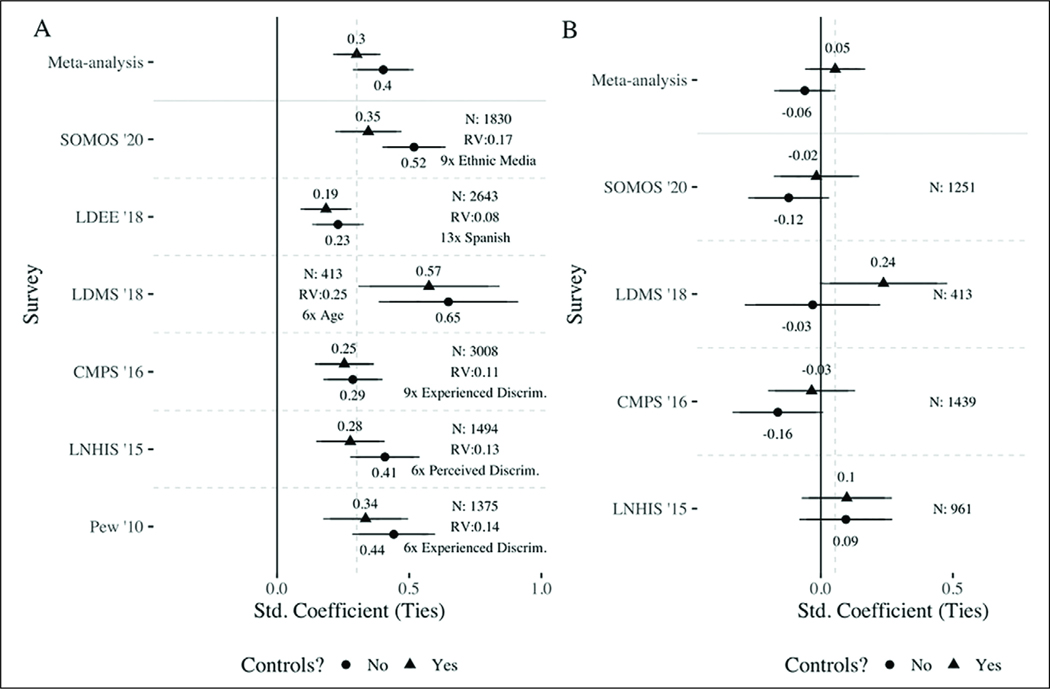

Figure 1.

Panels A/B characterize the association between undocumented social ties and protest/voting: (A) protest outcome and (B) vote outcome.

The x-axis is the standardized undocumented ties coefficient. Meta-analytic estimates are from a pooled random-effects model using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method. The red line is the meta-analytic point estimate. Sample size differences between protest and vote outcomes are because the voting item was only asked of registered voters. All estimates are from linear models. Displayed are 95% confidence intervals from heteroskedasticity-consistent robust errors (HC2). SOMOS = SOMOS-Unidos National Survey of Latinos, LDEE = Latino Decisions Election Eve; LDMS = Latino Decisions Midterm Survey; CMPS = Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey; LNHIS = Latino National Health and Immigration Survey; RV = robustness value.

The primary independent variable is undocumented social ties. Measurement across surveys varies. The Pew survey measure is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the respondent knows a deportee or someone detained for immigration reasons. The LNHIS and CMPS undocumented social ties items are identical. They ask whether the respondent knows someone undocumented among their “family, friends co-workers, and other people they may know.” If the respondent indicates “yes,” they are coded as 1, and 0 otherwise. Therefore, the measure captures both strong (e.g., friends, family) and weaker ties (e.g., co-workers, acquaintances). The LDMS, LDEE, and SOMOS items on undocumented social ties are formatted in a “list all that apply” framework. The LDMS asks respondents to think about “family, friends, co-workers, and people they know” and to check all social ties that apply to their network including family or a “friend/co-worker.” If they choose an option other than “No, do not know anyone undocumented,” social ties are coded as 1 and 0 otherwise. The LDEE asks respondents if they “know anybody who is an undocumented immigrant” and are allowed to indicate in the affirmative for a “family member,” “personal friend,” or “someone I know.” If they indicate yes to any of these categories, social ties are equal to 1 and 0 otherwise. The SOMOS survey asks respondents to think about “people in their family, as well as friends and co-workers” and indicate whether they know someone undocumented that is “in their household,” “in their family,” “a friend,” or “a co-worker.” If they indicate they know someone undocumented, social ties are equal to 1, and 0 otherwise. Although differences in measurement may have theoretical implications that affect the empirical results, we do not find the distinct measures of undocumented social ties produce results significantly different from aggregating all tie types (Figure 1).10

Across all surveys, we adjust for a battery of theoretically motivated control covariates accounting for demographic (e.g., foreign-born, Spanish-speaker), socioeconomic (e.g., income, education), political (e.g., partisanship, ideology), and contextual factors (e.g., % Latino at zip code and county-level, the county-level Secure Communities deportation rate per 1,000 foreign-born residents) in addition to state fixed effects.11 See Online Appendix Section E, Table E.2 for details on control covariate inclusion across surveys.

To test H2–H4, which concern the conditional influence of undocumented social ties given identity, we rely on the CMPS. No other survey includes all measures relevant to the question at hand, particularly the identity moderator. The CMPS includes a 4-point identity centrality item asking respondents to indicate how important being Latinx is to their sense of self.12 We use this item because prior studies demonstrate centrality, as operationalized in the CMPS, motivates pro-group behavior in response to threat (Brondolo et al. 2009; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje 2002; Lee 2005; Pérez 2015a, 2015b; Phinney et al. 2001). Moreover, consistent with our theory, it is associated with several measures of group commitment. Centrality is positively associated with support for liberal immigration policies, immigrant rights activism, and the notion anti-immigrant discrimination is anti-Latinx discrimination (see Online Appendix Section M.5). Alternatively, we might evaluate the influence of undocumented social ties on the outcomes of interest conditional on national origin identity centrality. This may be superfluous as national origin and Latinx centrality might capture the same concept. The Pearson’s ρ correlation coefficient for the two measures is .8 in the CMPS. Moreover, we replace Latinx centrality with national origin centrality and find using national origin centrality produces similar results to the main estimates using Latinx centrality (Online Appendix Section M, Table M.16).13

Because we assess the effect of undocumented social ties conditional on Latinx identity, we demonstrate undocumented social ties and Latinx identity are distinct constructs. Totally, 20 percent of lowest Latinx identifiers (1 on the 4-point scale) know someone undocumented. In total, 44 percent of high Latinx identifiers (4 on the 4-point scale) know someone undocumented. Similarly, 6 percent of Latinxs without undocumented social ties do not identify at all with other Latinxs, and 48 percent of Latinxs without undocumented social ties hold a strong Latinx identity. In all, 3 percent of Latinxs with undocumented social ties are lowest identifiers, and 63 percent of Latinxs with undocumented social ties are highest identifiers. Although there are few Latinxs who indicate they are on the lowest end of the centrality scale, our main findings are not sensitive to an alternative operationalization of Latinx identity, where we make the highest identifiers the reference category (see Online Appendix Section P).

The CMPS also includes two additional outcomes that help test our primary hypotheses: an item measuring agreement with the notion “anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx sentiment” on a 5-point Likert-type scale, which allows us to test our H2; and a measure of support for pro-immigrant activism on a 5-point Likert-type scale, which allows us to assess whether high-identifying Latinxs with undocumented ties are more likely to support pro-immigrant political activities relative to weak identifiers (H3). We refer to the outcome assessing whether Latinxs perceive anti-immigrant sentiment as anti-Latinx as the “homogeneity” outcome in the “Results” section. Consistent with our theoretical framework, this outcome measures the extent to which Latinxs are motivated to identify with immigrants and subsequently engage in pro-immigrant political activities. We expect high-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties will be inclined to believe anti-immigrant sentiment is an anti-Latinx issue given the ethno-racialization of immigration enforcement and conflation of Latinxs with undocumented immigrants. Likewise, we expect high-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties to support pro-immigrant activism. In light of the generalized protest measure in the CMPS, the pro-immigrant activism outcome helps demonstrate Latinx protest behavior on the part of high identifiers with undocumented social ties is motivated by pro-immigrant goals.

We draw on several other measures to test the hypothesis identity centrality is the primary mechanism linking undocumented ties with participation. Linked fate is chief among such mechanisms. Linked fate is less appropriate than centrality because it may not imply group commitment. For example, nativist Latinxs could have linked fate with new Latinx immigrants but perceive their connection negatively. Indeed, prior evidence suggests linked fate is not inherently tethered to participation or a politicized group consciousness, particularly for Latinxs (Gay, Hochschild, and White 2016; McClain et al. 2009; Sanchez and Vargas 2016). Identity centrality is a wellestablished measure in the social psychology literature in terms of its implications concerning group threat relative to linked fate (Brondolo et al. 2009; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje 2002; Lee 2005; Pérez 2015a, 2015b; Phinney et al. 2001). Consistent with our reservations, immigrant and Latinx linked fate do not increase participatory behavior among Latinxs with undocumented social ties (Online Appendix Section M, Table M.16).14 In addition to presenting models that the moderating effect of identity centrality persists net of linked fate, we replicate our main results among Latinxs with no linked fate and still find centrality serves to motivate pro-group behavior in the presence of undocumented social ties (Online Appendix Section M.4, Table M.19). Other potential mechanisms addressed include political efficacy, perceived and experienced discrimination, acculturation, perceived immigration status (measured by immigration status and whether one took the survey in Spanish), the presence of conducive opportunity structures, and prosociality.15

Results

Figure 1, Panel A, displays the unconditional effects of undocumented social ties on protest behavior.16 Across six surveys, undocumented social ties are positively and statistically associated with protesting. The standardized coefficient ranges from .2 in the LDEE to .6 in the LDMS, adjusting for a full battery of controls. For a clearer sense of the substantive influence, the unstandardized impact of undocumented social ties on the likelihood of protesting in the CMPS is 7 percentage points (pp). The CMPS protest mean is 10 pp irrespective of undocumented social ties (population weighted). Thus, the social ties effect is 70 percent of the mean protest level in the CMPS. We conduct a meta-analysis on the coefficients and corresponding standard errors with a pooled random-effects model and derive a meta-analytic coefficient of .3.17

Using tools developed by Cinelli and Hazlett (2020), we evaluate model sensitivity to omitted covariates, otherwise known as the “robustness value” (denoted as “RV” on Figure 1, Panel A). This analysis suggests an omitted covariate would need to explain 10–17 percent of the joint variation in social ties and protest across the surveys to nullify the undocumented tie coefficients. Drawing on observed benchmark covariates to assess what kinds of covariates obviate the results, we find the undocumented tie coefficient would be nullified by 6× experienced discrimination, 6× perceived discrimination, 9× experienced discrimination, 6× age, 13× Spanish-speaker, and 9× ethnic media consumption in the Pew, LNHIS, CMPS, LDMS, LDEE, and SOMOS data, respectively. This suggests our coefficients are relatively insulated from omitted variable bias.18

Conversely, the association between undocumented ties and voting is statistically and substantively insignificant (Figure 1, Panel B). Across the four surveys with voting items, the association between undocumented social ties and voting is always statistically null, and the coefficients are not consistently signed in one direction. After adjusting for covariates, the LDMS coefficient is positive and almost statistically significant (p < .10). Given the unadjusted coefficient is close to 0, we do not put much stock in this estimate. The discrepancy could be due to suppression effects, about which we have no theoretical prior, or a statistical artifact after running multiple specifications. Regardless, the meta-analytic standardized coefficient is statistically null. It is important to note the sample size is truncated to the registered voter population when evaluating the association between social ties and voting. We replicate this analysis among the citizen voting age population (CVAP) and derive similar results (Online Appendix Section G.3, Figure G.3). Likewise, we find the association between undocumented social ties and protest behavior holds among both registered voters and the CVAP (Online Appendix Section G.1, Figure G.5). In sum, across several surveys spanning different periods, undocumented ties are consistently associated with protesting, but not voting. These findings are consistent with our H1 suggesting protest activity offers better possibilities for pro-immigrant political engagement than does casting a ballot.

Heterogeneity by Latinx Identity

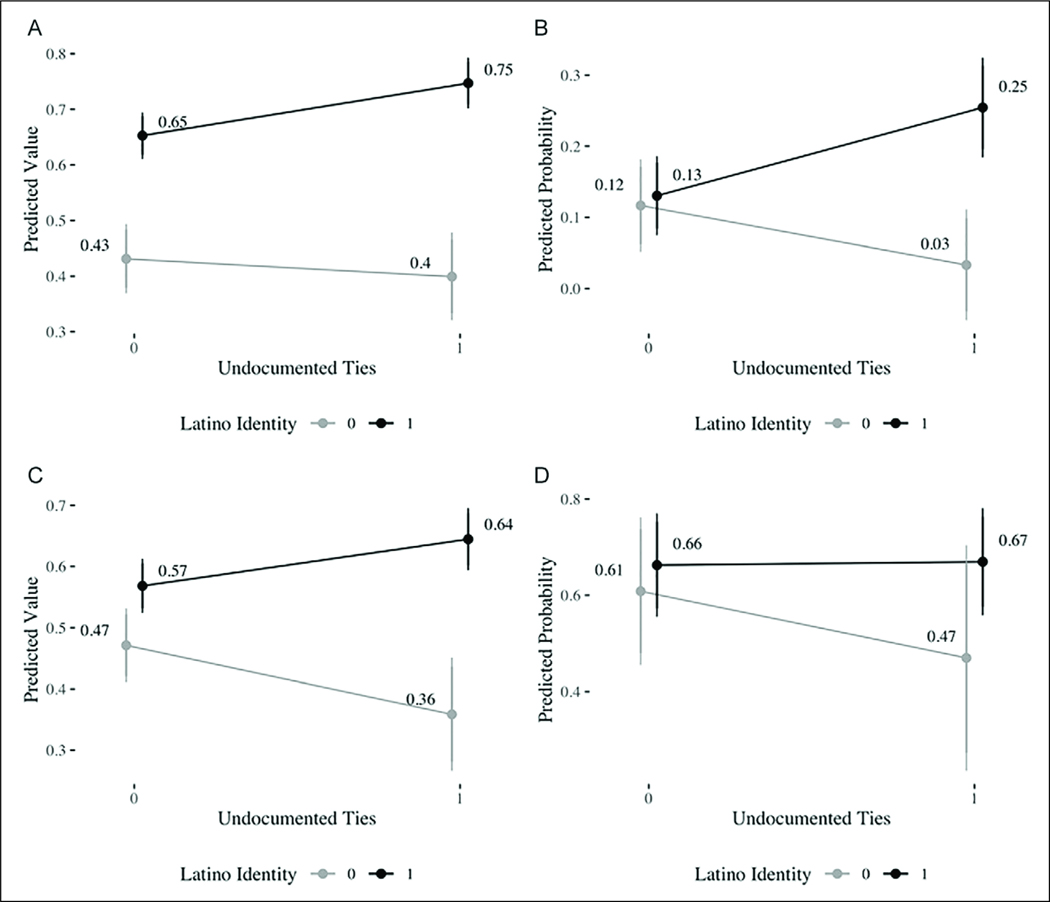

We now assess the moderating role of identity centrality on the relationship between undocumented social ties and participation, drawing primarily on the CMPS. Table 1, Panel A, displays the effect of undocumented social ties on belief in the notion anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx sentiment conditional on Latinx identity for a series of regression models with an increasing set of control covariates. Consistent with H2, Model 6, fully specified and including state fixed effects, demonstrates the effect of undocumented social ties is stronger among those higher levels of Latinx identity. Moreover, Latinx identity compensates for a reduction in the belief anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx sentiment among low identifiers with undocumented social ties. Figure 2, Panel A, displays the predicted value of support for the notion anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx conditional on undocumented social ties and Latinx identity. For high identifiers, undocumented social ties increase belief in anti-immigrant sentiment being anti-Latinx sentiment from .65 to .75 on the rescaled 0–1 point scale, 36 percent of the standard deviation. For low identifiers, undocumented social ties decrease the belief anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx from .43 to .4 on the 0 ×1 point scale, equivalent to 11 percent of the outcome standard deviation.

Table 1.

The Influence of Undocumented Social Ties Conditional on Latino Identity on Political Participation and Pro-group Attitudes.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Homogeneity Social Ties × Latino Identity |

0.19** (0.07) | 0.19** (0.06) | 0.19** (0.06) | 0.19** (0.06) | 0.19** (0.06) | 0.19** (0.06) |

| Social Ties | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.05) | −0.12* (0.05) | −0.12* (0.05) | −0.11* (0.05) |

| Latino Identity | 0.14*** (0.03) | 0.13*** (0.03) | 0.13*** (0.03) | 0.10** (0.03) | 0.10*** (0.03) | 0.10** (0.03) |

| R2 | .09 | .13 | .13 | .16 | .17 | .20 |

| Panel B: Protest Social Ties × Latino Identity |

0.19*** (0.06) | 0.20*** (0.05) | 0.21*** (0.05) | 0.20*** (0.05) | 0.20*** (0.05) | 0.21*** (0.06) |

| Social Ties | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.08* (0.04) | −0.08* (0.04) | −0.08* (0.04) |

| Latino Identity | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.05* (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| R2 | .04 | .05 | .06 | .08 | .09 | .12 |

| Panel C: Pro-immigrant Activism Social Ties × Latino Identity |

0.12* (0.06) | 0.13* (0.06) | 0.14* (0.06) | 0.14** (0.05) | 0.14* (0.05) | 0.13* (0.05) |

| Social Ties | 0.02 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.03 (0.05) |

| Latino Identity | 0.28*** (0.03) | 0.27*** (0.03) | 0.27*** (0.03) | 0.22*** (0.03) | 0.22*** (0.03) | 0.22*** (0.03) |

| R2 | .18 | .21 | .23 | .29 | .31 | .33 |

| N | 3,008 | 3,008 | 3,008 | 3,008 | 3,008 | 3,004 |

| Panel D: Vote Social Ties × Latino Identity |

0.17 (0.16) | 0.14 (0.14) | 0.14 (0.15) | 0.13 (0.14) | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.15 (0.14) |

| Social Ties | −0.24 (0.14) | −0.14 (0.12) | −0.14 (0.12) | −0.13 (0.12) | −0.11 (0.12) | −0.14 (0.12) |

| Latino Identity | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.07) |

| R2 | .01 | .08 | .09 | .09 | .13 | .18 |

| N | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,430 |

| Demographic Controls | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Socioeconomic Controls | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Political Controls | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| County Controls | N | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Zip code Controls | N | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| State fixed effects | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05. Each panel characterizes the heterogeneous effects of undocumented social ties by different social identities for different outcomes (A = support for notion anti-immigrant discrimination is anti-Latino discrimination, B = protest participation, C = support for pro-immigrant activism, D = validated voting participation). Model 1 includes no controls. Models 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 add demographic, socioeconomic, political, contextual, and state indicator controls, respectively. Dropped observations in Model 6 are due to the inclusion of state fixed effects (i.e., where N = 1 for a single state). All estimates are from linear models. All models include population weights. All covariates/outcomes are scaled between 0 and 1. Heteroskedasticity-consistent (HC2) robust standard errors are in parentheses

Figure 2.

Predicted values conditional on undocumented social ties and Latinx identity (Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey). Panel A is the predicted agreement with the notion that anti-immigrant sentiment is anti-Latinx sentiment. Panel B is the predicted protest probability. Panel C is the predicted support for pro-immigrant activism. Panel D is the predicted probability of (validated) voting.

The x-axis denotes undocumented social ties. The y-axis is the predicted value. Color denotes Latinx identity (min–max). Annotations denote predicted values. Predicted values are from fully specified models and assume control covariates set at their means and a respondent from California. All estimates are from linear models. All covariates are scaled from 0 to 1. Presented are 95% confidence intervals.

H3 posits undocumented social ties will be associated with higher participation in pro-immigrant political activities among those who hold a strong Latinx identity. We measure this two ways: participation in protests and support for pro-immigrant activism. Panel B of Table 1 displays the association between undocumented social ties and protest conditional on identity. Consistent with H3, fully specified Model 6 demonstrates the positive influence of undocumented social ties on protest participation is conditional on Latinx identity. Importantly, and consistent with the expectation, low identifiers will disassociate from the group, low-identifying Latinxs disengage from protest activity in the presence of an undocumented tie. However, a high Latinx identity more than compensates for the reduction in protest participation. We simulate the probability of protest conditional on undocumented social ties and Latinx identity (see Figure 2, Panel B). For a high-identifying Latinx, undocumented social ties increase the probability of protest from 13 to 25 pp, a 12 pp difference. In contrast, for a low-identifying Latinx, undocumented ties decrease likelihood of protesting from 12 to 3 pp, a 9 pp difference.

We also evaluate the heterogeneous effects of undocumented social ties on support for pro-immigrant activism to further assess H3. Table 1, Panel C, displays heterogeneous effects of undocumented social ties by Latinx identity across a series of models with an increasing number of covariates. The interaction coefficient is positive, suggesting that the effect of undocumented social ties on support for pro-immigrant activism is stronger among high Latinx identifiers. Figure 2, Panel C, displays predicted values of support for pro-immigrant activism conditional on undocumented social ties and Latinx identity. For high identifiers, undocumented social ties increase support for pro-immigrant activism from .65 to .75 on the rescaled 0–1 point scale, equivalent to 36 percent of the outcome standard deviation. For low identifiers, undocumented social ties decrease support for pro-immigrant activism from .43 to .4 on the 0–1 scale, equivalent to 45 percent of the outcome standard deviation.

Consistent with the unconditional association, identity does not appear to motivate higher rates of voter file validated voting for Latinxs with undocumented social ties. Table 1, Panel A, shows that the effect of social ties on voting does not appear to increase in strength conditional on Latinx identity.19 The predicted probabilities on Figure 2, Panel D, corroborate this conclusion. The difference in the probability of voting in the 2016 election for high-identifying Latinxs with and without undocumented social ties is only 1 pp (65–66 pp). For low identifiers, the difference between those with and without social ties is a relatively large, negative 14 pp decline (64–48 pp). Given the large negative effect of social ties for low identifiers on voting, there may be some heterogeneity not detected as statistically meaningful. This may be because of the reduced sample size in evaluating heterogeneity only among registered voters or because social ties do not appear to mobilize high identifiers to vote.

Finally, consistent with H4, we rule out other theoretically motivated mechanisms that may explain the association between undocumented social ties, protest participation, and pro-group attitudes. We assess the conditionality of undocumented social ties using the following measures: linked fate, political efficacy (internal, external, and group), a sense of injustice (proxied by both perceived and experienced discrimination, in keeping with Walker 2020), acculturation (proxied by generational status in addition to whether the respondent chose to take the survey in Spanish), perceived immigration status (proxied by skin color and whether the respondent believes others misperceive their immigration status), a conducive opportunity structure (whether a political leader, group, or organization attempted to mobilize the respondent to take political action or vote), and prosociality (how many neighbors the respondent talks to frequently). We also adjust for alternative social identities that may be activated in the presence of undocumented social ties such as partisanship and gender identity (Abrajano 2010; Dreby 2012; Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo 2013).

Even after adjusting for alternative mechanisms, the interaction between undocumented social ties and Latinx identity is still positive and statistically significant for the relevant outcomes (see Online Appendix Section K.1, Tables K.10, K.11, and K.12). Moreover, we also rule out whether alternative measures of identity may be driving our results. Table M.19 on Online Appendix Section M.4, demonstrates that replacing Latinx centrality with Latinx linked fate or immigrant linked fate does not produce heterogeneous effects by undocumented social ties. Moreover, conditional on having no linked fate, Latinx centrality still has a moderating influence on undocumented social ties (Online Appendix Section M.4, Table M.20). In tandem, these results confirm our theoretical expectation that centrality is the identity measure best suited to capture Latinx responses to group threat via undocumented social ties.

In summary, these results suggest undocumented social ties motivate pro-group behavior and attitudes conditional on ethnic identity and that identity is the superordinate mechanism driving protest participation. However, strong identity in the presence of undocumented social ties does not motivate behaviors less amenable to promoting ethnic interests, such as voting.20

Robustness Checks

We attempt to alleviate three selection concerns. First, prosocial Latinxs may select into relationships with undocumented immigrants and also be more inclined to participate politically. Second, undocumented social ties may have occurred after protest engagement, given the protest measures are retrospective.21 Third, high identifiers may seek relationships with undocumented people given their politicized status. We alleviate these concerns by decomposing the social ties measure into two categories, familial and friendship ties, and assess the effects of undocumented ties on the outcomes of interest. The logic is Latinxs with undocumented familial ties will have greater difficulty leveraging their identity, prosociality, or political engagement to select into an undocumented social tie given the ascriptive nature of familial relationships. Consistent with the main results, familial and friendship ties with undocumented immigrants operate similarly and are positively associated with protest participation (Online Appendix Section F.2, Figure F.2). Coefficient similarity between familial and friendship ties suggest factors that plausibly produce selection into friendship and pro-immigrant participation do not drive the association between undocumented ties and pro-group politics.22 Moreover, for protest and homogeneity (but not voting and support for pro-immigrant activism), the positive effect of both familial and friendship ties is conditional on a strong sense of Latinx identity (Online Appendix Section F.4, Table F.3).

We also attempt to alleviate reverse causality concerns between protest and identity. Prior research suggests limited cause for concern. In a meta-analysis of sixty-four studies assessing the link between identity and protest, Van Zomeren, Postmes, and Spears (2008, 516) indicate there were, “no significant differences between effect sizes in studies that allowed causal inferences versus those that did not,” suggesting, “the magnitude of these reverse effects is not such that they would entirely invalidate causal inferences drawn from the observations of cross-sectional data.” Moreover, prior work assessing the influence of protest on Latinx identity finds null results (Silber Mohamed 2013). We replicate Silber Mohamed (2013) using Latino National Survey (LNS) data and find exposure to the 2006 immigration protests does not increase Latinx identity.23 Although the replication cannot account for direct participation, we adjust the estimation strategy and interact protest exposure with characteristics associated with protest participation in a separate study and still find null results (Barreto et al. 2009; Online Appendix Section U, Table U.28). In addition, we replicate our CMPS results using an alternative measure of Latinx identity in the LNHIS, perceived discrimination against Latinxs and immigrants, which has prospective protest measures less susceptible to reverse causality (see Online Appendix Section L, Table L.15 and Figure L.7 for details). We derive heterogeneous effects for undocumented social ties similar to our main estimates.

We assess the sensitivity of our results to different scales of the participation outcomes (Online Appendix Section H). We do this to rule out measurement error. All protest participation outcomes are binary with the exception of the LNHIS, which is on a 4-point Likert-type scale from “not at all likely” to “extremely likely.” We generate two new versions of a binary protest indicator in the LNHIS to rule out if undocumented social ties are only motivating political participation among Latinxs on the lower end of the scale. First, we code “extremely likely” equal to 1 and make all other values equal to 0. Second, we code “extremely likely” and “very likely” equal to 1 and make all other values equal to 0. Online Appendix Table H.7 demonstrates recoding the LNHIS outcome does not influence the main results. For voting, the CMPS is a binary retrospective measure whereas the others are Likert-type scales (LNHIS, LDMS, SOMOS). Two outcomes ask how likely the respondent is to vote in the upcoming national election on a 5-point scale (LNHIS, SOMOS). The other asks how likely respondents will vote on a 10-point scale (LDMS). In the main results, the LDMS outcome is recoded as a binary measure equal to 1 if they indicate 10 on the scale. We recode the LDMS measure back to its 0–10 scale and reevaluate the association between social ties and voting. Likewise, we convert the LNHIS and SOMOS surveys to binary indicators equal to 1 if the respondent puts the highest value of the Likert-type scale on their vote intention. Online Appendix Table H.7 displays coefficient estimates of undocumented social ties with respect to the different voting outcome operationalizations. Consistent with the main results, undocumented social ties have no statistically significant association with self-reported voting behavior.

Conclusion

We began this paper with the following question: how do undocumented social ties influence Latinx political behavior? Whereas prior work has analyzed the political consequences of a threatening immigration environment, less research explores the consequences of undocumented ties and underlying mechanisms motivating participation. Building on work at the intersection of social identity theory and anti-immigrant threat (Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje 2002; Pérez 2015a, 2015b), we address this gap and provide evidence Latinx identity is a key mechanism connecting undocumented ties to participatory outcomes net of other theoretically motivated mechanisms.

Drawing on six surveys of Latinxs, we demonstrate undocumented social ties motivate collective forms of political participation amenable to promoting group interests and identity expression but not individualistic forms of political participation. Using a large nationally representative sample of Latinxs with the CMPS, we find that high-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties are more likely to perceive anti-immigrant sentiment as anti-Latinx, support pro-immigrant activism, and engage in protest activity. Moreover, consistent with our contention that voting participation offers limited avenues for pro-group expression relative to protest activity, social ties do not motivate voting conditional on Latinx identity. Conversely, consistent with social identity theory, low-identifying Latinxs with undocumented social ties are less likely to engage in protest activity. These findings are robust to several model specifications and hold net of alternative mechanisms.

This paper makes several contributions. First, we answer the call to assess mechanisms motivating pro-group behavior among Latinxs with undocumented social ties (Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán 2017). We forward Latinx identity as a mechanism to demonstrate how and why undocumented social ties translate into pro-group behavior despite the participatory constraints undocumented social ties may impose. Second, we contribute to the Latinx identity-to-politics literature, elucidating the importance of social context in addition to geographic, rhetorical, and policy context in politicizing Latinx identity. Third, we contribute to a growing literature focused on the policy feedback effects of the expansion of interior immigration enforcement that disparately targets Latinx communities. Whereas much has been written on how immigrants are criminalized, less is known about the specific social mechanisms that subject Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics to punitive immigration restrictions.

Our analysis has limitations. While we subject our analyses to several model specifications, sensitivity analyses, and do our best to rule out alternative mechanisms, our data do not permit us to definitively rule out endogeneity. Although randomizing undocumented social ties would be difficult (and perhaps impossible in a familial context), future research may consider conducting short-term contact experiments to assess the causal effect of undocumented social ties on pro-group behavior among Latinxs. Field experiments may also explicate whether short-term contact with undocumented immigrants is sufficient in motivating costly pro-immigrant behaviors. Likewise, identity salience could be induced experimentally to ascertain the causal effect of undocumented social ties among Latinxs assigned to a high-salience relative to low-salience condition. In addition, future studies on undocumented ties should leverage panel designs to circumvent reverse causality concerns.

Future research should undertake questions of interest this study implicates but cannot explore. Social movement scholars find evidence that pro-group protests can motivate identity. Likewise, participation in pro-immigrant activism may bring otherwise documented Latinxs into contact with undocumented activists, which may have secondary political consequences. Although we provide evidence this reverse causal process may not obviate our results, future work should assess how pro-immigrant protest participation motivates Latinx identity and social networks in the post-Trump era. Another area ripe for further research is the extent to which and how undocumented social ties motivate pro-immigrant participation or attitudes among other nonwhite groups. Of particular interest are Asian Americans, the fastest growing ethno-racial subgroup in the United States due to immigration, and black immigrants,24 who may contend with dual targeting based on both immigration status and antiblackness. The intersections of criminal justice, immigration policy, and race(ism) are avenues that increasingly demand scholarly attention.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Replication code (all relevant replication materials for reproducing tables and figures, for example, R code, data, associated codebooks) is available at: http://www.marcelroman.com/research.html or contact the corresponding author. Supplemental materials for this article are available with the manuscript on the Political Research Quarterly (PRQ) website.

See Online Appendix Section A, Figure A.2, for plots characterizing the descriptive statistics referenced here.

Undocumented social ties cue threat. Online Appendix Section I, Table I.8, shows undocumented social ties are associated with fear of friends or family being deported. The effect of social ties is large, 72 and 73 percent of the sample mean in the Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (LNHIS) and Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey (CMPS), respectively.

In Texas alone, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) wrongfully placed detainers on 3,500 U.S. citizens between 2006 and 2018 (Bier 2018).

See Online Appendix Section C for details on sampling, margin of error, response rates, and weighting for each survey.

See Online Appendix Section V.1 for details and full item text.

We use the Latino Decisions Election Eve (LDEE) survey to validate whether self-reported, retrospective protest approximates real-world behavior. Objective measures of pro-immigrant protest activity (see Fisher et al. 2019) are positively associated with self-reported protest at the individual level, suggesting self-reported participation is demonstrative of behavior (Online Appendix Section S).

See Online Appendix Section V.2 for details on the measurement of voting participation and the full item texts.

We do not believe the retrospective nature of our outcomes poses a reverse causality problem. Below, we leverage ascriptive social ties measures less susceptible to reverse causality and find similar results to the main social ties measure.

See Online Appendix Section V.3 for details on the measurement of undocumented social ties and full item texts. We validate if self-reported undocumented ties approximate actual relationships. A reasonable assumption is that undocumented immigrants live in areas with more Latinx, foreign-born, or noncitizen residents. Figures R.9 and R.10 in Online Appendix Section R demonstrate whether respondents who live in areas with more Latinxs, foreign-born people, and noncitizens are more likely to report undocumented ties. Moreover, see Online Appendix Section F, which assesses the sensitivity of the results to disaggregated social ties measures and alternative coding decisions while discussing the theoretical implications of using various undocumented social ties measures.

The Pew survey does not include controls regarding Secure Communities because the program did not end until November 2014, after the survey was administered.

See Online Appendix Section V.4 for full item wording.

The high correlation between Latinx and national origin centrality raises questions over whether our respondents are politically engaged on behalf of Latinxs writ large, or Latinxs who share their national origin. Given the high correlation between the two constructs, we cannot adjudicate between these possibilities.

Moreover, Latinx linked fate, immigrant linked fate, and Latinx identity centrality are distinct constructs. For instance, the Pearson’s U correlation coefficient between Latinx linked fate and Latinx identity centrality is .29. The correlation coefficient for immigrant linked fate and Latinx centrality is .25. These are modest correlations, suggesting the items do not measure the same underlying construct.

See Online Appendix Section V.5 for details on items characterizing the mechanisms.

Although we discuss coefficients as “effects,” this is only for the sake of accessibility and readability. Our analysis is observational, so we do not mean to imply the coefficients of interest have a causal interpretation.

Cochran’s Q significance test for heterogeneity on the coefficients from fully specified models is p < .04. This appears driven by the LDMS study and its relatively large coefficient. The meta-analytic estimate without the LDMS is .25, yet the Cochran’s Q test is statistically insignificant at p < .02.

We did not choose these benchmark covariates arbitrarily. These covariates nullify the effect of undocumented social ties first after incrementally multiplying their explained joint variance in the outcome and social ties.

Results are similar for voting and protest outcomes if we subset to the citizen voting age population (CVAP) and registered voters (Online Appendix Section G.2, Table G.5).

For information on the estimation strategies we use to derive these estimates, see Online Appendix Section B.

The LNHIS ‘15 uses a prospective protest participation measure. The effect for undocumented social ties using LNHIS data is positive, statistically significant, and nearly identical to the meta-analytic effect (see Figure 1), suggesting the main results are not driven by a reverse causal process.

We also disaggregate undocumented familial and friendship ties and find familial or friendship ties are not independently associated with voting (Online Appendix Section F.3, Figure F.4).

If any protest event would increase Latinx identity, it would be the 2006 immigration protests, which had millions of participants across 102 cities and was able to make immigration the “most important issue” among the American public at the highest level until July 2018, after Trump’s family separation policy implementation (Online Appendix Section U, Figure U.12).

This is not to deny the existence of black Latinxs in our sample, but to prescribe an explicit focus on both black Latinx immigrants and their co-ethnics along with non-Latinx black immigrants.

References

- Abrajano Marisa. 2010. Campaigning to the New American Electorate: Advertising to Latino Voters. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abrajano Marisa, and Hajnal Zoltan L.. 2017. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alsan Marcella, and Yang Crystal. 2018. Fear and the Safety Net: Evidence from Secure Communities. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Amuedo-Dorantes Catalina, and Lopez Mary J.. 2017. “Interior Immigration Enforcement and Political Participation of US Citizens in Mixed-Status Households.” Demography 54 (6): 2223–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta Amada. 2017. Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura Albert, and Walters Richard H.. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Vol. 1. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Banks Antoine J., White Ismail K., and McKenzie Brian D.. 2019. “Black Politics: How Anger Influences the Political Actions Blacks Pursue to Reduce Racial Inequality.” Political Behavior 41 (4): 917–43. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Matt. 2010. Ethnic Cues: The Role of Shared Ethnicity in Latino Political Participation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Matt A., Manzano Sylvia, Ramírez Ricardo, and Rim Kathy. 2009. “Mobilization, Participation, and Solidaridad Latino Participation in the 2006 Immigration Protest Rallies.” Urban Affairs Review 44 (5): 736–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bedolla Lisa Garcia. 2005. Fluid Borders. 1st ed. University of California Press. www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppf2x. [Google Scholar]

- Bier David. 2018. “U.S. Citizens Targeted by ICE: U.S. Citizens Targeted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Texas https://www.cato.org/publications/immigration-research-policy-brief/us-citizens-targeted-ice-us-citizens-targeted. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler Shaun, Nicholson Stephen P., and Segura Gary M.. 2006. “Earthquakes and After- Shocks: Race, Direct Democracy, and Partisan Change.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (1): 146–59. [Google Scholar]

- Brady Henry E., Verba Sidney, and Schlozman Kay Lehman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” American Political Science Review 89:271–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo Elizabeth, Brady ver Halen Nisha, Pencille Melissa, Beatty Danielle, and Contrada Richard J.. 2009. “Coping with Racism: A Selective Review of the Literature and a Theoretical and Methodological Critique.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32 (1): 64–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Susan K., and Bean Frank D.. 2016. “Migration Status and Political Knowledge among Latino Immigrants.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2 (3): 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Capps Randy, Chishti Muzaffar, Gelatt Julia, Bolter Jessica, and Ruiz Soto Ariel G.. 2018. “Revving up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement and Pushback under Trump.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/ImmigrationEnforcement-FullReport-FINAL-WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli Carlos, and Hazlett Chad. 2020. “Making Sense of Sensitivity: Extending Omitted Variable Bias.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 82 (1): 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby Joanna. 2012. “The Burden of Deportation on Children in Mexican Immigrant Families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (4): 829–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby Joanna. 2015. Everyday Illegal: When Policies Undermine Immigrant Families. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers Naomi, Spears Russell, and Doosje Bertjan. 2002. “Self and Social Identity.” Annual Review of Psychology 53 (1): 161–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Dana R., Andrews Kenneth T., Caren Neal, Chenoweth Erica, Heaney Michael T., Leung Tommy, Perkins L. Nathan, and Pressman Jeremy. 2019. “The Science of Contemporary Street Protest: New Efforts in the United States.” Science Advances 5 (10): eaaw5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores Rene D. 2014. “Living in the Eye of the Storm: How Did Hazleton’s Restrictive Immigration Ordinance Affect Local Interethnic Relations?” American Behavioral Scientist 58 (13): 1743–63. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Rene D., and Schachter Ariela. 2018. “Who Are the ‘Illegals’? The Social Construction of Illegality in the United States.” American Sociological Review 83 (5): 839–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga Bernard L. 2016. “Candidates or Districts? Reevaluating the Role of Race in Voter Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (1): 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gay Claudine, Hochschild Jennifer, and White Ariel. 2016. “Americans’ Belief in Linked Fate: Does the Measure Capture the Concept?” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 1 (1): 117–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson Shannon. 2010. “Labor Rights for All? The Role of Undocumented Immigrant Status for Worker Claims Making.” Law & Social Inquiry 35 (3): 561–602. [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza Tanya, and Hondagneu-Sotelo Pierrette. 2013. “Latino Immigrant Men and the Deportation Crisis: A Gendered Racial Removal Program.” Latino Studies 11 (3): 271–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy Leonie. 2003. “Group Identity and Political Cohesion.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by Sears, Huddy, and Jervis, 511–558. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings M Kent Laura Stoker, and Jake Bowers. 2009. “Politics across Generations: Family Transmission Reexamined.” The Journal of Politics 71 (3): 782–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Correa Michael, and Els De Graauw. 2013. “The Illegality Trap: The Politics of Immigration & the Lens of Illegality.” Daedalus 142 (3): 185–98. [Google Scholar]

- Klandermans PG 2014. “Identity Politics and Politicized Identities: Identity Processes and the Dynamics of Protest.” Political Psychology 35 (1): 1–22. www.jstor.org/stable/43785856. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Richard M. 2005. “Resilience against Discrimination: Ethnic Identity and Other-Group Orientation as Protective Factors for Korean Americans.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52 (1): 36. [Google Scholar]

- McClain Paula D., Johnson Carew Jessica D., Walton Eugene, and Watts Candis S.. 2009. “Group Membership, Group Identity, and Group Consciousness: Measures of Racial Identity in American Politics?” Annual Review of Political Science 12:471–85. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Arthur H., Gurin Patricia, Gurin Gerald, and Malanchuk Oksana. 1981. “Group Consciousness and Political Participation.” American Journal of Political Science 25 (3): 494–511. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski Krysia N. 2003. “Coping with Perceived Discrimination: Does Ethnic Identity Protect Mental Health?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:318–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols Vanessa Cruz, LeBrón Alana M. W., and Pedraza Francisco I.. 2018. “Policing Us Sick: The Health of Latinos in an Era of Heightened Deportations and Racialized Policing.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (2): 293–97. [Google Scholar]

- Noh Samuel, and Kaspar Violet. 2003. “Perceived Discrimination and Depression: Moderating Effects of Coping, Acculturation, and Ethnic Support.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (2): 232–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda Christopher. 2015. “Depression and Political Participation.” Social Science Quarterly 96 (5): 1226–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja Adrian D., Ramirez Ricardo, and Segura Gary M.. 2001. “Citizens by Choice, Voters by Necessity: Patterns in Political Mobilization by Naturalized Latinos.” Political Research Quarterly 54 (4): 729–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja Adrian D., and Segura Gary M.. 2003. “Fear and Loathing in California: Contextual Threat and Political Sophistication among Latino Voters.” Political Behavior 25 (3): 265–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza Franciso I., Vanessa Cruz Nichols, and LeBrón Alana M. W.. 2017. “Cautious Citizenship: The Deterring Effect of Immigration Issue Salience on Health Care Use and Bureaucratic Interactions among Latino US Citizens.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 42 (5): 925–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Efrén O. 2015a. “Ricochet: How Elite Discourse Politicizes Racial and Ethnic Identities.” Political Behavior 37 (1): 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Efrén O. 2015b. “Xenophobic Rhetoric and Its Political Effects on Immigrants and Their Co-Ethnics.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 549–64. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney Jean S., Horenczyk Gabriel, Liebkind Karmela, and Vedder Paul. 2001. “Ethnic Identity, Immigration, and Well-Being: An Interactional Perspective.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (3): 493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Poletta Francesca, and Jasper James M.. 2001. “Collective Identity and Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Reny Tyler, Bryan Wilcox-Archuleta, and Vanessa Cruz Nichols. 2018. “Threat, Mobilization, and Latino Voting in the 2018 Election.” The Forum 16:573–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Rene R., Knoll Benjamin R., and Wrinkle Robert D.. 2015. “Immigration Enforcement and the Redistribution of Political Trust.” The Journal of Politics 77 (4): 901–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz Rogelio, and Karen Manges Douglas. 2015. “A Call for the Racialization of Immigration Studies: On the Transition of Ethnic Immigrants to Racialized Immigrants.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1 (1): 166–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel R., and Vargas Edward D.. 2016. “Taking a Closer Look at Group Identity: The Link between Theory and Measurement of Group Consciousness and Linked Fate.” Political Research Quarterly 69 (1): 160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel R., Vargas Edward D., Walker Hannah L., and Ybarra Vickie D.. 2015. “Stuck between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Relationship between Latino/a’s Personal Connections to Immigrants and Issue Salience and Presidential Approval.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 3 (3): 454–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingles Richard D. 1981. “Black Consciousness and Political Participation: The Missing Link.” The American Political Science Review 75 (1): 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Silber, Heather. 2013. “Can Protests Make Latinos ‘American’? Identity, Immigration Politics, and the 2006 Marches.” American Politics Research 41 (2): 298–327. [Google Scholar]

- Street Alex, Michael Jones-Correa, and Chris Zepeda-Millán. 2017. “Political Effects of Having Undocumented Parents.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (4): 818–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel Henri, Turner JC, Austin WG, and Worchel S. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In Organizational Identity: A Reader, edited by Hatch MJ and Schultz M, 56–65. Oxford Management Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. 2018. “Deportations under ICE’s Secure Communities Program.” https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/509/.

- Utsey Shawn O., Ponterotto Joseph G., Reynolds Amy, and Cancelli Anthony A.. 2000. “Racial Discrimination, Coping, Life Satisfaction, and Self-Esteem among African Americans.” Journal of Counseling & Development 78 (1): 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Ali A., and Michelson Melissa R.. 2016. “Turnout, Status, and Identity: Mobilizing Latinos to Vote with Group Appeals.” American Political Science Review 110 (4): 615–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stekelenburg Van, Jacquelien, and Bert Klandermans. 2013. “The Social Psychology of Protest.” Current Sociology 61 (5): 886–905. doi: 10.1177/0011392113479314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zomeren Van, Martijn Tom Postmes, and Spears Russell. 2008. “Toward an Integrative Social Identity Model of Collective Action: A Quantitative Research Synthesis of Three Socio-psychological Perspectives.” Psychological Bulletin 134 (4): 504–35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Edward D. 2015. “Immigration Enforcement and Mixed-Status Families: The Effects of Risk of Deportation on Medicaid Use.” Children and Youth Services Review 57:83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Edward D., Meli n, Sanchez Gabriel R., and Livaudais Maria. 2019. “Latinos’ Connections to Immigrants: How Knowing a Deportee Impacts Latino Health.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45:2971–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Edward D., and Pirog Maureen A.. 2016. “Mixed-Status Families and WIC Uptake: The Effects of Risk of Deportation on Program Use.” Social Science Quarterly 97 (3): 555–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker Hannah L. 2020. Mobilized by Injustice: Criminal Justice Contact, Political Participation, and Race. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Hannah L., Roman Marcel, and Barreto Matt. 2020. “The Ripple Effect: The Political Consequences of Proximal Contact with Immigration Enforcement.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 5 (3): 537–72. [Google Scholar]

- White Ariel. 2016. “When Threat Mobilizes: Immigration Enforcement and Latino Voter Turnout.” Political Behavior 38 (2): 355–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu. 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda-Millán Chris. 2017. Latino Mass Mobilization: Immigration, Racialization, and Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.